1. Introduction

The central goal of cell biology is to understand the principles that govern the construction and operation of a living cell. Despite decades of progress, we still face fundamental, unanswered questions regarding, for instance, the control of organelle size, the coordination of metabolic tasks, and the link between an organelle's physical properties and its function. These questions have remained remarkably resistant to analysis, largely because of the great complexity of cellular systems and our limited ability to experimentally manipulate them in a precise and systematic way.

Here, I argue that a new path forward is provided by the combination of the algal pyrenoid (

Figure 1), a uniquely powerful model system, with generative artificial intelligence (AI), a revolutionary new technology. This path represents the principles of an emerging paradigm: Generative Science. This approach shifts the scientific method from a traditional cycle of observation and analysis ("read to understand") to one of design, generation, and learning ("build to understand"). By using our knowledge to create novel biological entities that have never existed, we can test the limits of our understanding and uncover new rules. I propose to reframe the study of the pyrenoid, viewing it not merely as a photosynthetic curiosity, but as a

Rosetta Stone for this new science. In this perspective, I will outline how an AI-driven inverse design pipeline, applied to the pyrenoid, can be used to directly address five of cell biology's greatest unsolved problems.

2. Scaling of Organelle Size

The first challenge addresses one of cell biology’s oldest and most fundamental questions: what determines the size of a cell and its internal organelles? [

1]. For over a century, scientists have observed that organelles, such as the nucleus, maintain a remarkably consistent size relative to the cell. However, understanding the physical and molecular mechanisms that establish these "scaling laws" remains a classic, unsolved problem.

The algal pyrenoid, a massive and simple membraneless organelle, offers a uniquely suitable system to investigate this long-standing mystery. Its assembly is governed by the simple physics of liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). The size of such a liquid droplet is, in principle, determined by factors like the concentration of its component proteins and the surface tension at its interface [

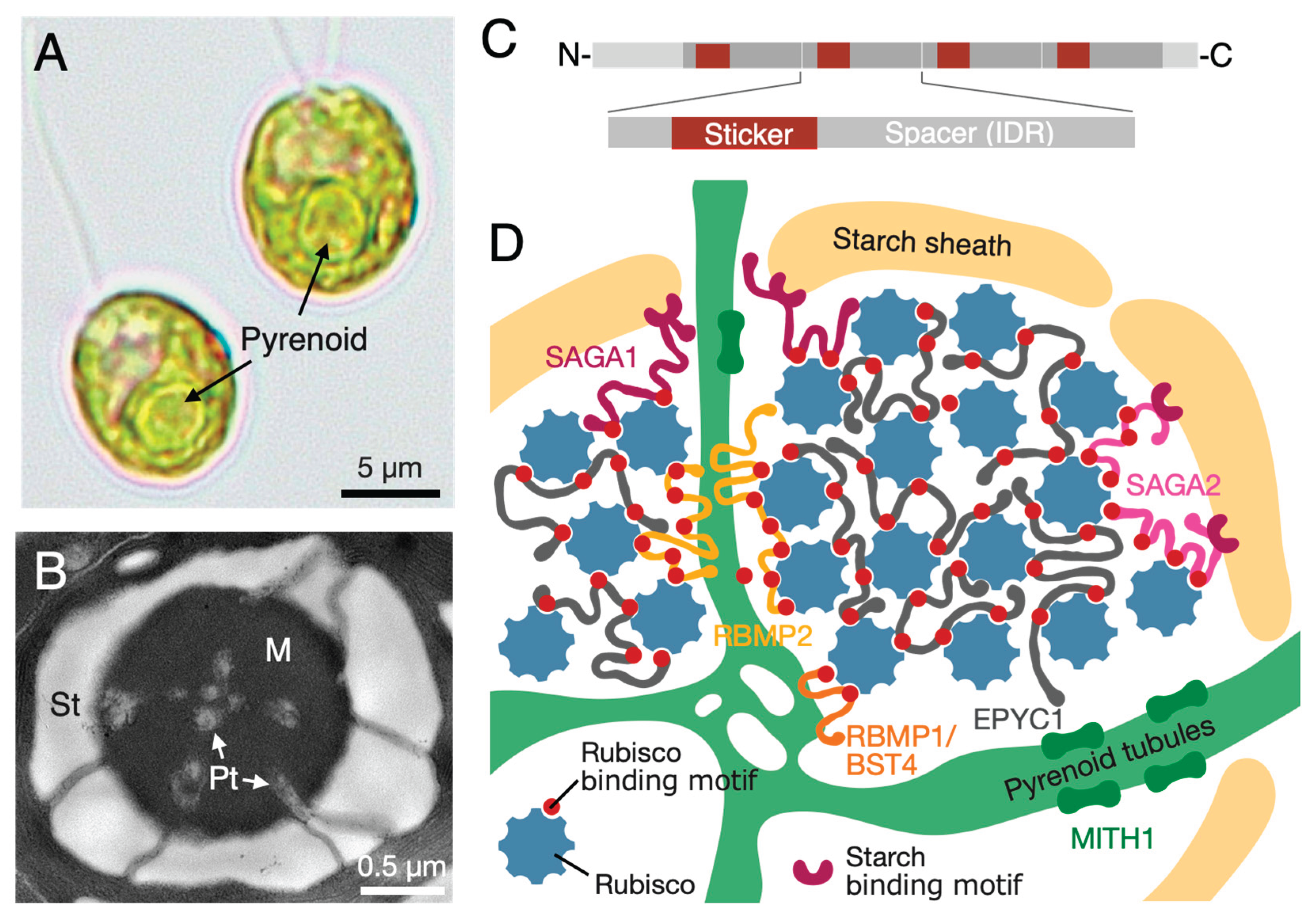

2]. Much of our detailed mechanistic insight of the pyrenoid comes from extensive studies in the model green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (

Figure 1A and B). The key components of the pyrenoid, the linker protein EPYC1 and the CO

2-fixing enzyme Rubisco (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) (

Figure 1C and D), are known to phase separate at specific, measurable concentrations, providing a direct, quantifiable link between the amount of protein and the resulting organelle [

3,

4,

5].

This direct link between molecular components and macroscopic structure is precisely what makes the system well-suited for a synthetic, AI-driven approach. The historical challenge has been the inability to systematically vary these physical parameters in vivo. An AI inverse design pipeline, which uses generative models capable of de novo protein creation [

6], overcomes this barrier. We can task an AI to generate a library of linker proteins with systematically varied biophysical properties, such as the saturation concentration for phase separation, by altering the number of "sticker" motifs or the charge distribution of the "spacers" (

Figure 1C), key determinants of a condensate’s physical properties [

7]. By expressing this library in a synthetic chassis (e.g., a pyrenoid-defected Chlamydomonas mutant lacking the endogenous linker protein EPYC1) and quantitatively measuring the resulting pyrenoid size and internal architecture using advanced 3D imaging techniques like cryo-electron tomography, we can directly test physical models of organelle scaling and experimentally derive the scaling laws for a membraneless organelle.

3. Organelle Communication and Metabolic Channeling

A second challenge is to understand how cells orchestrate complex metabolic pathways across different organelles and cellular compartments. To maximize efficiency, cells are thought to channel metabolites between sequential enzymes, but the mechanisms governing this process, especially at the dynamic interface of membraneless organelles, are poorly understood [

8]. Furthermore, how these LLPS-based hubs coordinate their activity with the rest of the cell’s membrane-bound machinery remains a key question in cellular logistics [

9].

The CO

2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) of the algal pyrenoid provides a powerful example of how nature solves these logistical challenges at multiple scales. Its architecture is a prime example of hierarchical metabolic organization. At the finest scale, the pyrenoid matrix is physically penetrated by extensions of the thylakoid membrane, creating a direct interface between a membraneless condensate and a membrane-bound lumen [

10]. At the periphery, this efficiency is further enhanced by a "salvage loop", where the carbonic anhydrases LCIB/LCIC complex recaptures leaked CO

2 (

Figure 2) [

11,

12]. Finally, at the whole-cell scale, the system coordinates with distant mitochondria in a clear example of on-demand resource allocation: upon CCM induction by CO

2-limiting conditions, they dynamically migrate to the cell periphery to fuel energy-intensive HCO

3– transporters on the plasma membrane, such as the ABC transporter HLA3 [

13,

14].

These natural examples of multi-scale metabolic organization inspire a new, synthetic approach to systematically probe the underlying principles [

15]. We can use AI pipeline to design linker proteins that not only self-assemble with Rubisco but also contain domains programmed to interact with the thylakoid membrane, allowing us to test how modulating the pyrenoid-thylakoid interface affects overall CCM efficiency. Furthermore, we can use the pyrenoid surface as a programmable scaffold. An AI could design specific "docking sites" on the linker protein surface, alongside a corresponding set of metabolic enzymes engineered to bind these sites [

16]. By building synthetic pathways tethered to the condensate, we can systematically measure how enzyme proximity and spatial organization affect metabolic flux, thus uncovering the fundamental design principles of metabolic channeling. Ultimately, a whole-cell simulation integrating these local design principles could begin to predict the large-scale logistical responses, such as mitochondrial repositioning, that emerge from these molecular-level interactions.

4. Biophysical Basis of Condensate Function

The last decade has seen an explosion of research into LLPS, revealing that cells are filled with biomolecular condensates. A key frontier in this field is to move beyond identifying these bodies to understanding how their physical, material properties (e.g., viscosity, density, surface tension) directly govern their biological function [

17,

18]. This "form-to-function" relationship is central to the entire field, yet its quantitative understanding remains a major challenge.

The pyrenoid provides an ideal experimental system to quantitatively address this "form-to-function" relationship. It is a natural, enzyme-filled bioreactor whose primary function, CO

2-fixation by Rubisco, is readily measurable. Crucially, it is known to exist in a dynamic, liquid-like state, which is thought to be essential for balancing enzyme concentration with substrate diffusion [

19]. Most importantly, its assembly is driven by a linker protein whose "sticker-spacer" grammar is unusually simple and predictable, creating a direct link between sequence, physical properties, and a measurable biochemical output [

7]. This grammar has profound functional consequences; it was recently shown that linker proteins from distantly related algae, while both capable of forming a pyrenoid, create condensates with dramatically different internal dynamics and material properties [

20].

This direct and predictable link from sequence to function is precisely what makes the system well-suited for an AI-driven approach. This is key to separating the variables that are normally intertwined in natural systems. We can task the AI to generate a "viscosity library"—a series of linker proteins where the Rubisco-binding "stickers" are held constant, but the flexible "spacer" regions are systematically varied in length, charge, and hydrophobicity. After expressing these variants in vivo, we could directly measure the material state of each synthetic pyrenoid using biophysical techniques like Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) and microrheology, while simultaneously measuring the enzymatic turnover rate of the Rubisco inside. Crucially, executing this analysis requires precise consideration of the stoichiometry of the components [

17]. As the relative concentrations of the linker and Rubisco are key determinants of a condensate's material state, we must ensure that expression levels are comparable across the library, or precisely measured, to disentangle the effects of designed sequence variations from simple concentration effects. This would allow us to plot a direct curve relating a condensate’s physical viscosity to its catalytic enhancement, systematically investigating the trade-off between enzyme concentration and substrate diffusion within this reaction-diffusion system, and providing ground truth for the physical theory of phase-separated biochemistry.

5. Mechanism of De Novo Organelle Biogenesis

How are complex cellular structures built de novo at the right time, in the right place, and in the right number? While some organelles grow and divide, many must be re-formed in each cell generation. The principles that govern how thousands of components self-assemble into a single, functional organelle with precise positional and numerical control are a fundamental mystery in cell biology [

21].

The pyrenoid’s remarkable cycle of disassembly and reassembly during cell division provides clues to all three aspects of this problem. First, for the "how", its rapid assembly is driven by the simple "sticker-spacer" grammar, a minimal set of rules for spontaneous formation [

4,

22]. The robustness and modularity of this process were recently strikingly demonstrated: a functional pyrenoid was successfully formed de novo in a pyrenoid-less Chlamydomonas mutant using a linker protein from Chlorella, a species separated by ~800 million years of evolution [

20]. Second, it provides a clear example of the "where" and "how many". In Chlamydomonas, a single pyrenoid is reliably formed at the base of the chloroplast, implying the existence of a unique spatial landmark or nucleation site that both dictates the location and prevents the formation of condensates in the wrong place or in excess numbers.

This unique system, with its simple assembly rules and precise spatiotemporal control, is perfectly suited for investigation using an AI-driven design pipeline. To probe the minimal requirements of assembly, we can first task the AI to design the simplest possible linker that can still trigger de novo condensation in a synthetic chassis. Beyond this, the pipeline can be used to directly test the "spatial landmark" hypothesis for positioning and number control. An AI could be tasked to design linker variants with new domains that tether them to ectopic locations within the cell. Expressing these retargeted linkers in Chlamydomonas would allow us to test if we can synthetically move the site of pyrenoid biogenesis. Success in this would not only identify the rules that govern cellular landmarks but also provide a generalizable method for controlling the position of synthetic organelles, a major goal in synthetic biology.

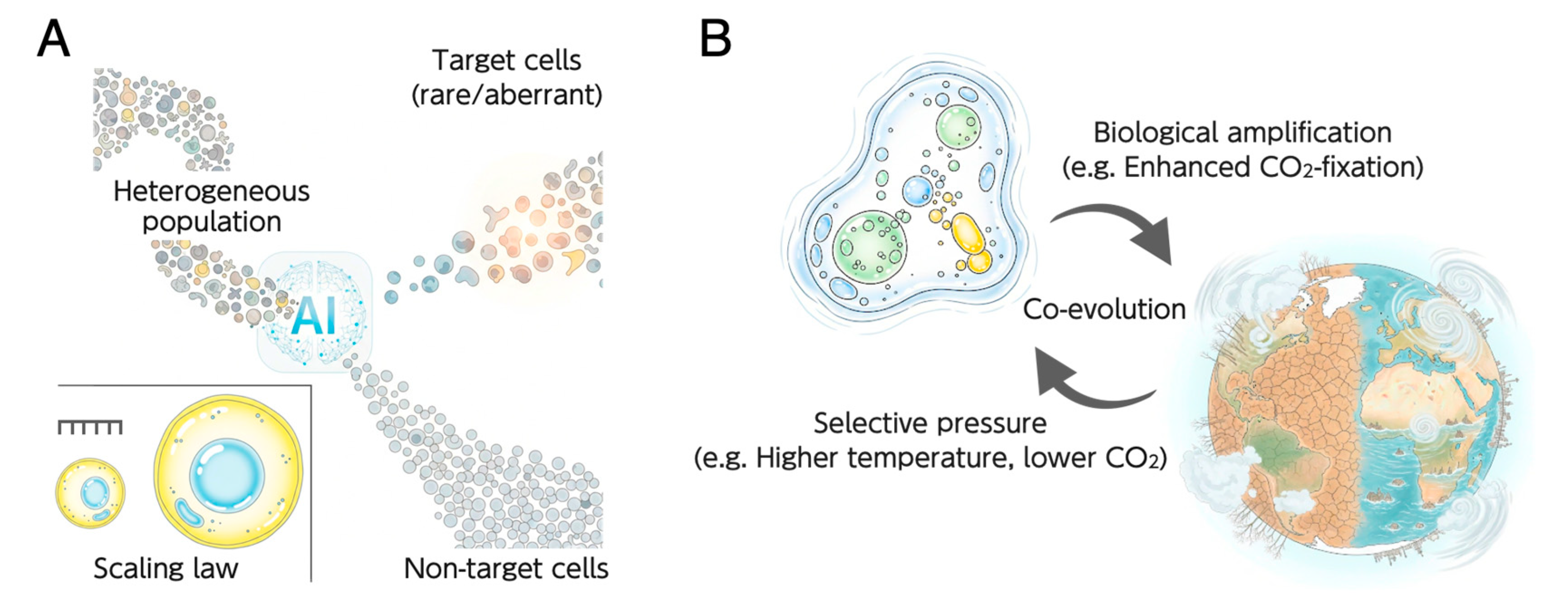

A complementary, top-down approach to dissect these control mechanisms is now available through technologies like intelligent Image-Activated Cell Sorting (iIACS) [

23]. Unlike traditional methods, iIACS uses deep learning to sort cells at an unprecedented rate based on complex morphological features like the intracellular location of proteins. This strategy has been powerfully demonstrated in Chlamydomonas to isolate mutants with aberrant localization of the LCIB protein. The same principle can be directly applied to this challenge. By screening millions of mutagenized cells, the iIACS could rapidly isolate rare mutants with defects in pyrenoid number or position (

Figure 3A). Subsequent genomic analysis of these mutants would then reveal the genes governing the precise spatiotemporal control of organelle biogenesis. This synergy of AI-driven design (bottom-up) and AI-driven sorting (top-down) represents a powerful, two-pronged strategy to solve this fundamental mystery.

6. Modeling the Co-Evolution of Life and Planet

Finally, a truly grand challenge lies in connecting microscopic changes in cellular architecture to macroscopic changes in the planetary environment over geological time. Understanding this deep co-evolutionary dynamic requires integrating cell biology, evolutionary theory, and Earth system science, a frontier often highlighted as a key future direction for the life sciences. How can we build a predictive model of this multi-scale interplay?

The evolutionary history of the pyrenoid provides a rich, concrete dataset to begin constructing such a model. Its entire evolutionary history exemplifies this principle, with its diversification being directly linked to drops in atmospheric CO

2 [

24]. These evolutionary adaptations also involved the co-option of existing structures for new functions. For instance, in green algae, the starch sheath, likely an ancestral storage structure, was repurposed to play a critical role in the CCM; it became essential for the proper localization of the peripheral protein complex LCIB/LCIC and began to function as a crucial CO

2 diffusion barrier [

25]. Conversely, the notable absence of pyrenoids in most land plants, which developed alternative solutions like C

4 photosynthesis in the gaseous terrestrial environment, speaks directly to the equally important principle of historical contingency [

26,

27,

28]. Furthermore, the success of organisms with CCMs had a profound feedback effect on the planet, boosting primary production and contributing to further changes in global carbon cycles [

29]. The pyrenoid is thus not just a passive responder to the environment, but an active shaper of it (

Figure 3B).

This deep evolutionary dataset, which captures both environmental pressures and the organism’s feedback effects, provides an invaluable, climate-informed foundation for any predictive design effort. This climate-informed Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) pipeline thus provides the starting point for a full, in silico eco-evolutionary experiment. An AI can be used to design multiple virtual phytoplankton species, each with a pyrenoid optimized for a different future climate scenario. We can then place these virtual species into a simulated ocean environment and run multi-generational simulations. The AI’s task would expand to predict not just protein fitness, but population dynamics, competitive exclusion, and the feedback effects on the local environment's chemistry. This would be a first step towards a true digital twin of microbial evolution, allowing us to test how specific, AI-designed molecular innovations might manifest at an ecological and ultimately planetary scale. Ultimately, such predictive power is a prerequisite for any future geoengineering strategy, and could one day inform the foundational principles of terraforming.

7. Conclusion

In this review, I have reframed the algal pyrenoid as a Rosetta Stone for understanding some of the most fundamental problems in cell biology (

Figure 4). I have argued that the key to unlocking this potential lies in a new synthesis: uniting this uniquely designable biological module with the inventive power of generative AI to quantitatively investigate a remarkable range of challenges, from the physical laws of organelle architecture to the deep co-evolution of life and the planet.

The pyrenoid is a striking example of convergent evolution, having emerged independently multiple times across diverse photosynthetic lineages. This natural diversity provides the foundation for the unifying grand project. The first step is to create a comprehensive Pyrenoid Linker Atlas by mining the hundreds of available algal genomes. This unique dataset would then be used to fine-tune a dedicated Protein Language Model [

30], creating an expert AI that has learned the deep grammar of pyrenoid assembly. Realizing this vision, however, presents significant challenges. Accurately predicting the emergent biophysical properties (e.g., viscosity, saturation concentration) of the intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) that constitute the "spacers" remains a major hurdle due to their conformational heterogeneity. Furthermore, translating in silico designs into functional condensates within the complex cellular milieu requires extensive experimental validation and iterative DBTL cycles. Despite these hurdles, such an AI could ultimately move beyond mimicking nature to true de novo invention, generating novel linkers with tailored physical properties or even new functions, such as environmentally-responsive metabolic switches. This "build to understand" approach is at the core of Generative Science. It represents a direct path to transform cell biology from an observational science into a predictive and constructive one, creating a new paradigm where we can not only read the book of life, but begin to write its next chapters.

Author Contributions

T.Y.: Conceptualization; Investigation; Visualization; Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Writing – Review & Editing; Project Administration; Funding Acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant numbers JP24K01851 and JP25H01332 to T.Y.), JST GteX Program (JPMJGX23B0 to T.Y.), the Asahi Glass Foundation (to T.Y.).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Koujiro Matsuo, Sizuka Miichi, Yumeka Masuda, and Ami Matsuda for their insightful discussions. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used Google's Gemini model for the purposes of improving phrasing, checking grammar, and generating conceptual diagrams. The author have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CCM |

CO2-Concentrating Mechanism |

| DBTL |

Design-Build-Test-Learn |

| FRAP |

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching |

| IDRs |

Intrinsically Disordered Regions |

| iIACS |

Intelligent Image-Activated Cell Sorting |

| LLPS |

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation |

| Rubisco |

Ribulose-1,5-Bisphosphate Carboxylase/Oxygenase |

References

- Marshall WF. Scaling of Subcellular Structures. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2020, 36, 219–236.

- Weber CA, Zwicker D, Jülicher F, Lee CF. Physics of active emulsions. Rep Prog Phys. 2019, 82, 064601. [CrossRef]

- Mackinder LC, Meyer MT, Mettler-Altmann T, Chen VK, Mitchell MC, Caspari O, Freeman Rosenzweig ES, Pallesen L, Reeves G, Itakura A, Roth R, Sommer F, Geimer S, Mühlhaus T, Schroda M, Goodenough U, Stitt M, Griffiths H, Jonikas MC. A repeat protein links Rubisco to form the eukaryotic carbon-concentrating organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, 5958–63. [CrossRef]

- Ang WSL, How JA, How JB, Mueller-Cajar O. The stickers and spacers of Rubiscondensation: assembling the centrepiece of biophysical CO2-concentrating mechanisms. J Exp Bot. 2023, 74, 612–626.

- Wunder T, Cheng SLH, Lai SK, Li HY, Mueller-Cajar O. The phase separation underlying the pyrenoid-based microalgal Rubisco supercharger. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 5076.

- Watson JL, Juergens D, Bennett NR, Trippe BL, Yim J, Eisenach HE, Ahern W, Borst AJ, Ragotte RJ, Milles LF, Wicky BIM, Hanikel N, Pellock SJ, Courbet A, Sheffler W, Wang J, Venkatesh P, Sappington I, Torres SV, Lauko A, De Bortoli V, Mathieu E, Ovchinnikov S, Barzilay R, Jaakkola TS, DiMaio F, Baek M, Baker D. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100.

- Payne-Dwyer A, Kumar G, Barrett J, Gherman LK, Hodgkinson M, Plevin M, Mackinder L, Leake MC, Schaefer C. Predicting Rubisco-Linker Condensation from Titration in the Dilute Phase. Phys Rev Lett. 2024, 132, 218401.

- Agapakis CM, Boyle PM, Silver PA. Natural strategies for the spatial optimization of metabolism in synthetic biology. Nat Chem Biol. 2012, 8, 527–35. [CrossRef]

- Hyman AA, Weber CA, Jülicher F. Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:39-58.

- Engel BD, Schaffer M, Kuhn Cuellar L, Villa E, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W. Native architecture of the Chlamydomonas chloroplast revealed by in situ cryo-electron tomography. Elife 2015, 4, e04889. [CrossRef]

- Yamano T, Tsujikawa T, Hatano K, Ozawa S, Takahashi Y, Fukuzawa H. Light and low-CO2-dependent LCIB-LCIC complex localization in the chloroplast supports the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 1453–68.

- Yamano T, Toyokawa C, Shimamura D, Matsuoka T, Fukuzawa H. CO2-dependent migration and relocation of LCIB, a pyrenoid-peripheral protein in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 1081–1094. [CrossRef]

- Findinier J, Joubert LM, Fakhimi N, Schmid MF, Malkovskiy AV, Chiu W, Burlacot A, Grossman AR. Dramatic changes in mitochondrial subcellular location and morphology accompany activation of the CO2 concentrating mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024, 121, e2407548121.

- Yamano T, Sato E, Iguchi H, Fukuda Y, Fukuzawa H. Characterization of cooperative bicarbonate uptake into chloroplast stroma in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015, 112, 7315–20.

- Hilditch AT, Romanyuk A, Cross SJ, Obexer R, McManus JJ, Woolfson DN. Assembling membraneless organelles from de novo designed proteins. Nat Chem. 2024, 16, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Dueber JE, Wu GC, Malmirchegini GR, Moon TS, Petzold CJ, Ullal AV, Prather KL, Keasling JD. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 753–9.

- Banani SF, Rice AM, Peeples WB, Lin Y, Jain S, Parker R, Rosen MK. Compositional Control of Phase-Separated Cellular Bodies. Cell 2016, 166, 651–663.

- Shin Y, Brangwynne CP. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 2017, 357, eaaf4382.

- Freeman Rosenzweig ES, Xu B, Kuhn Cuellar L, Martinez-Sanchez A, Schaffer M, Strauss M, Cartwright HN, Ronceray P, Plitzko JM, Förster F, Wingreen NS, Engel BD, Mackinder LCM, Jonikas MC. The Eukaryotic CO2-Concentrating Organelle Is Liquid-like and Exhibits Dynamic Reorganization. Cell 2017, 171, 148–162.

- Barrett J, Naduthodi MIS, Mao Y, Dégut C, Musiał S, Salter A, Leake MC, Plevin MJ, McCormick AJ, Blaza JN, Mackinder LCM. A promiscuous mechanism to phase separate eukaryotic carbon fixation in the green lineage. Nat Plants 2024, 10, 1801–1813.

- Rafelski SM, Marshall WF. Building the cell: design principles of cellular architecture. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 593–602.

- He S, Chou HT, Matthies D, Wunder T, Meyer MT, Atkinson N, Martinez-Sanchez A, Jeffrey PD, Port SA, Patena W, He G, Chen VK, Hughson FM, McCormick AJ, Mueller-Cajar O, Engel BD, Yu Z, Jonikas MC. The structural basis of Rubisco phase separation in the pyrenoid. Nat Plants 2020, 6, 1480–1490. [CrossRef]

- Nitta N, Sugimura T, Isozaki A, Mikami H, Hiraki K, Sakuma S, Iino T, Arai F, Endo T, Fujiwaki Y, Fukuzawa H, Hase M, Hayakawa T, Hiramatsu K, Hoshino Y, Inaba M, Ito T, Karakawa H, Kasai Y, Koizumi K, Lee S, Lei C, Li M, Maeno T, Matsusaka S, Murakami D, Nakagawa A, Oguchi Y, Oikawa M, Ota T, Shiba K, Shintaku H, Shirasaki Y, Suga K, Suzuki Y, Suzuki N, Tanaka Y, Tezuka H, Toyokawa C, Yalikun Y, Yamada M, Yamagishi M, Yamano T, Yasumoto A, Yatomi Y, Yazawa M, Di Carlo D, Hosokawa Y, Uemura S, Ozeki Y, Goda K. Intelligent Image-Activated Cell Sorting. Cell 2018, 175, 266–276. [CrossRef]

- Falkowski PG, Katz ME, Milligan AJ, Fennel K, Cramer BS, Aubry MP, Berner RA, Novacek MJ, Zapol WM. The rise of oxygen over the past 205 million years and the evolution of large placental mammals. Science 2005, 309, 2202–4.

- Toyokawa C, Yamano T, Fukuzawa H. Pyrenoid starch sheath is required for LCIB localization and the CO₂-concentrating mechanism in green algae. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1883–1893. [CrossRef]

- Knoll AH. Paleobiological perspectives on early eukaryotic evolution. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014 Jan 1;6(1):a016121.

- Raven JA, Beardall J, Giordano M. Energy costs of carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms in aquatic organisms. Photosynth Res. 2014, 121, 111–24.

- Villarreal JC, Renner SS. Hornwort pyrenoids, carbon-concentrating structures, evolved and were lost at least five times during the last 100 million years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109, 18873–8. [CrossRef]

- Giordano M, Beardall J, Raven JA. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 99–131.

- Madani A, Krause B, Greene ER, Subramanian S, Mohr BP, Holton JM, Olmos JL Jr, Xiong C, Sun ZZ, Socher R, Fraser JS, Naik N. Large language models generate functional protein sequences across diverse families. Nat Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1099–1106. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Pyrenoid structure in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. (A) Bright-field image of Chlamydomonas cells. The large, globular structure within the chloroplast is the pyrenoid. (B) Transmission electron micrograph of the pyrenoid. Three key ultrastructures are visible: the dense inner matrix (M), the outer polysaccharide shell known as the starch sheath (St), and pyrenoid tubules (Pt) where thylakoid membranes penetrate the matrix. (C) Schematic of the linker protein EPYC1, illustrating the "sticker-spacer" grammar. Multiple "sticker" domains (Rubisco-binding motifs) are separated by "spacer" regions, which are intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). This multivalency drives phase separation. (D) Molecular model of the pyrenoid's hierarchical organization. The liquid-like matrix is formed by the phase separation of Rubisco (blue complexes) and the multivalent linker EPYC1 (gray scaffold). This core is connected to the outer starch sheath by the proteins SAGA1 and SAGA2. Thylakoid membranes penetrate deep into the matrix as pyrenoid tubules, a process requiring the protein MITH1. Other proteins like RBMP1/BST4 and RBMP2 are also key for structural organization. This figure was created with reference to multiple sources, including He et al., 2020 and others cited in the text.

Figure 1.

Pyrenoid structure in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. (A) Bright-field image of Chlamydomonas cells. The large, globular structure within the chloroplast is the pyrenoid. (B) Transmission electron micrograph of the pyrenoid. Three key ultrastructures are visible: the dense inner matrix (M), the outer polysaccharide shell known as the starch sheath (St), and pyrenoid tubules (Pt) where thylakoid membranes penetrate the matrix. (C) Schematic of the linker protein EPYC1, illustrating the "sticker-spacer" grammar. Multiple "sticker" domains (Rubisco-binding motifs) are separated by "spacer" regions, which are intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). This multivalency drives phase separation. (D) Molecular model of the pyrenoid's hierarchical organization. The liquid-like matrix is formed by the phase separation of Rubisco (blue complexes) and the multivalent linker EPYC1 (gray scaffold). This core is connected to the outer starch sheath by the proteins SAGA1 and SAGA2. Thylakoid membranes penetrate deep into the matrix as pyrenoid tubules, a process requiring the protein MITH1. Other proteins like RBMP1/BST4 and RBMP2 are also key for structural organization. This figure was created with reference to multiple sources, including He et al., 2020 and others cited in the text.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the cellular reorganization in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in response to CO2 availability. Under high-CO2 conditions (left), the CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) is suppressed. Mitochondria and the carbonic anhydrase complex LCIB/LCIC are dispersed in the cytoplasm and chloroplast stroma, respectively, and the pyrenoid is small with no surrounding starch sheath. Upon a shift to CO2-limiting conditions (right), the CCM is induced, triggering a coordinated reorganization. The pyrenoid matrix expands, and a prominent starch sheath is formed around it. The LCIB/LCIC complex is relocalized to the pyrenoid periphery to recapture leaked CO2, while mitochondria migrate towards the plasma membrane to energize transport processes.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the cellular reorganization in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in response to CO2 availability. Under high-CO2 conditions (left), the CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) is suppressed. Mitochondria and the carbonic anhydrase complex LCIB/LCIC are dispersed in the cytoplasm and chloroplast stroma, respectively, and the pyrenoid is small with no surrounding starch sheath. Upon a shift to CO2-limiting conditions (right), the CCM is induced, triggering a coordinated reorganization. The pyrenoid matrix expands, and a prominent starch sheath is formed around it. The LCIB/LCIC complex is relocalized to the pyrenoid periphery to recapture leaked CO2, while mitochondria migrate towards the plasma membrane to energize transport processes.

Figure 3.

Integrative approaches to understanding cellular architecture and its evolution. (A) AI-driven dissection of de novo organelle biogenesis. This panel illustrates a top-down strategy utilizing Artificial Intelligence (AI), such as intelligent Image-Activated Cell Sorting (iIACS), to analyze heterogeneous cell populations. This high-throughput method enables the isolation of rare or aberrant target cells (e.g., mutants with defects in organelle number or position). Analyzing these cells facilitates the identification of the mechanisms governing the precise spatiotemporal control of organelle biogenesis. (Inset) Illustration of the scaling law, a classic unsolved problem in cell biology concerning the mechanisms that ensure organelles maintain a consistent size relative to the cell. (B) The co-evolution of cellular architecture and the environment. This schematic depicts the dynamic feedback loop between cellular adaptation and planetary changes. Shifts in the global environment create selective pressures (e.g., higher temperature, lower atmospheric CO2). These pressures drive the evolution of specialized cellular architectures, such as CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCMs). The resulting biological amplification (e.g., enhanced CO2 fixation) increases primary production, which, in turn, feeds back to actively shape the planetary environment by influencing global carbon cycles.

Figure 3.

Integrative approaches to understanding cellular architecture and its evolution. (A) AI-driven dissection of de novo organelle biogenesis. This panel illustrates a top-down strategy utilizing Artificial Intelligence (AI), such as intelligent Image-Activated Cell Sorting (iIACS), to analyze heterogeneous cell populations. This high-throughput method enables the isolation of rare or aberrant target cells (e.g., mutants with defects in organelle number or position). Analyzing these cells facilitates the identification of the mechanisms governing the precise spatiotemporal control of organelle biogenesis. (Inset) Illustration of the scaling law, a classic unsolved problem in cell biology concerning the mechanisms that ensure organelles maintain a consistent size relative to the cell. (B) The co-evolution of cellular architecture and the environment. This schematic depicts the dynamic feedback loop between cellular adaptation and planetary changes. Shifts in the global environment create selective pressures (e.g., higher temperature, lower atmospheric CO2). These pressures drive the evolution of specialized cellular architectures, such as CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCMs). The resulting biological amplification (e.g., enhanced CO2 fixation) increases primary production, which, in turn, feeds back to actively shape the planetary environment by influencing global carbon cycles.

Figure 4.

A conceptual diagram illustrating the central thesis of this perspective. At its core lies the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, representing the "build to understand" paradigm of Generative Science. This iterative, AI-driven cycle uses a programmable biological module, such as the pyrenoid (represented by the central logo), as a unified platform to systematically investigate five fundamental, unsolved problems in cell biology.

Figure 4.

A conceptual diagram illustrating the central thesis of this perspective. At its core lies the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, representing the "build to understand" paradigm of Generative Science. This iterative, AI-driven cycle uses a programmable biological module, such as the pyrenoid (represented by the central logo), as a unified platform to systematically investigate five fundamental, unsolved problems in cell biology.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).