Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

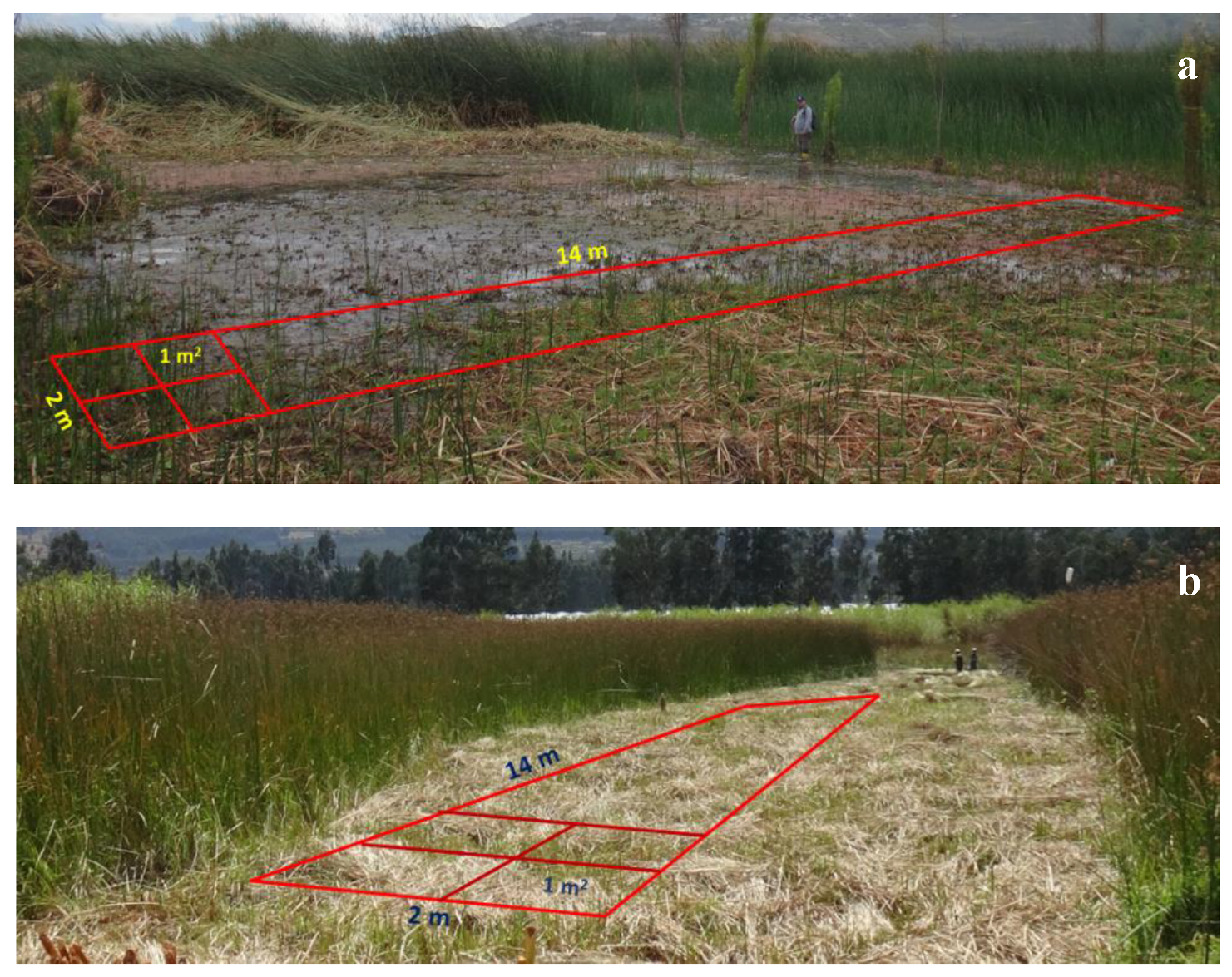

2. Materials and Methods

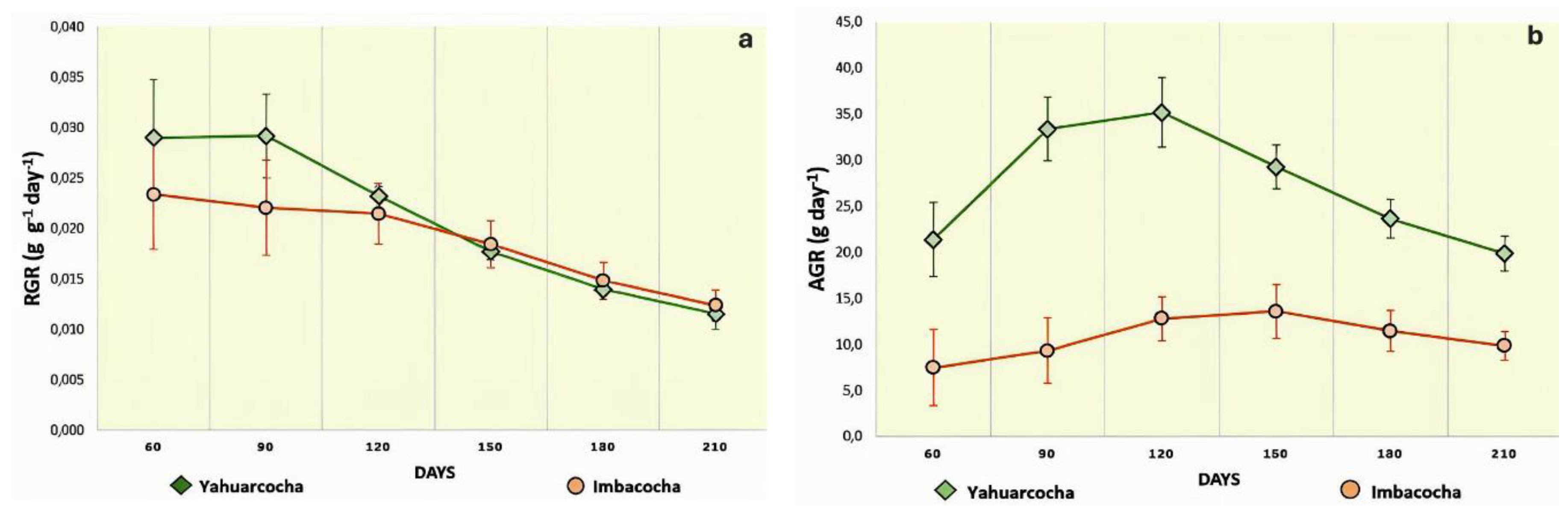

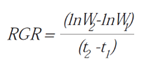

- Relative Growth Rate (RGR): increase in plant material per unit of existing plant material per unit of time [45].

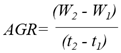

- Absolute Growth Rate (AGR): increase in dry mass of plant material per unit of time [23].

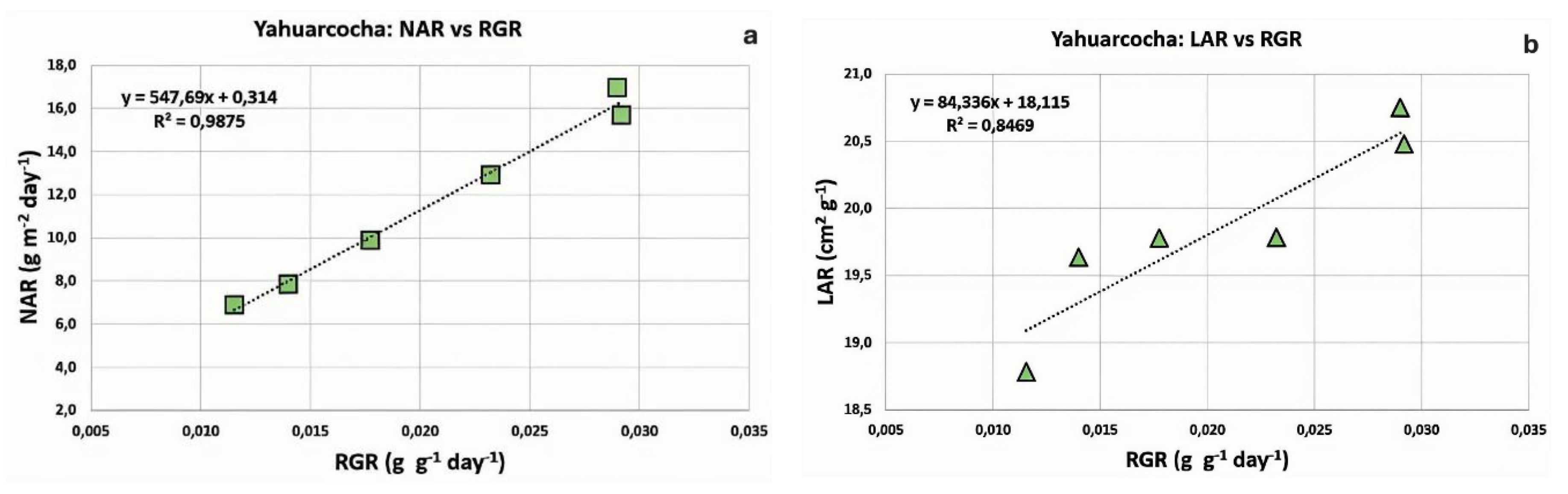

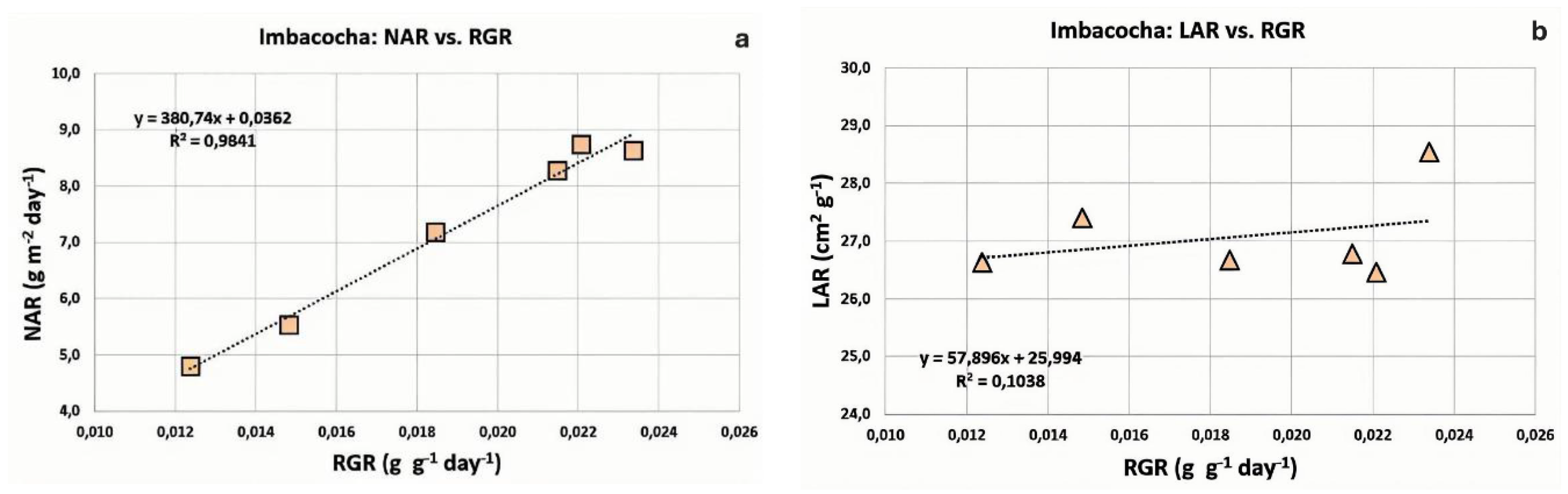

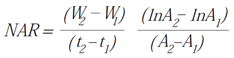

- Net Assimilation Rate (NAR): estimates the plant’s photosynthetic capacity; represents the rate of increase in plant mass per unit of leaf area [46].

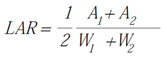

- Leaf Area Ratio (LAR): ratio of leaf area to total plant mass [44].

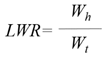

- Leaf Weight Ratio (LWR): ratio of leaf biomass to total plant biomass [44].

- Specific Leaf Area (SLA): ratio between leaf area and dry mass of each leaf [44].

- Leaf Area Index (LAI): instantaneous measure relating assimilatory surface area per unit of ground surface area [23].

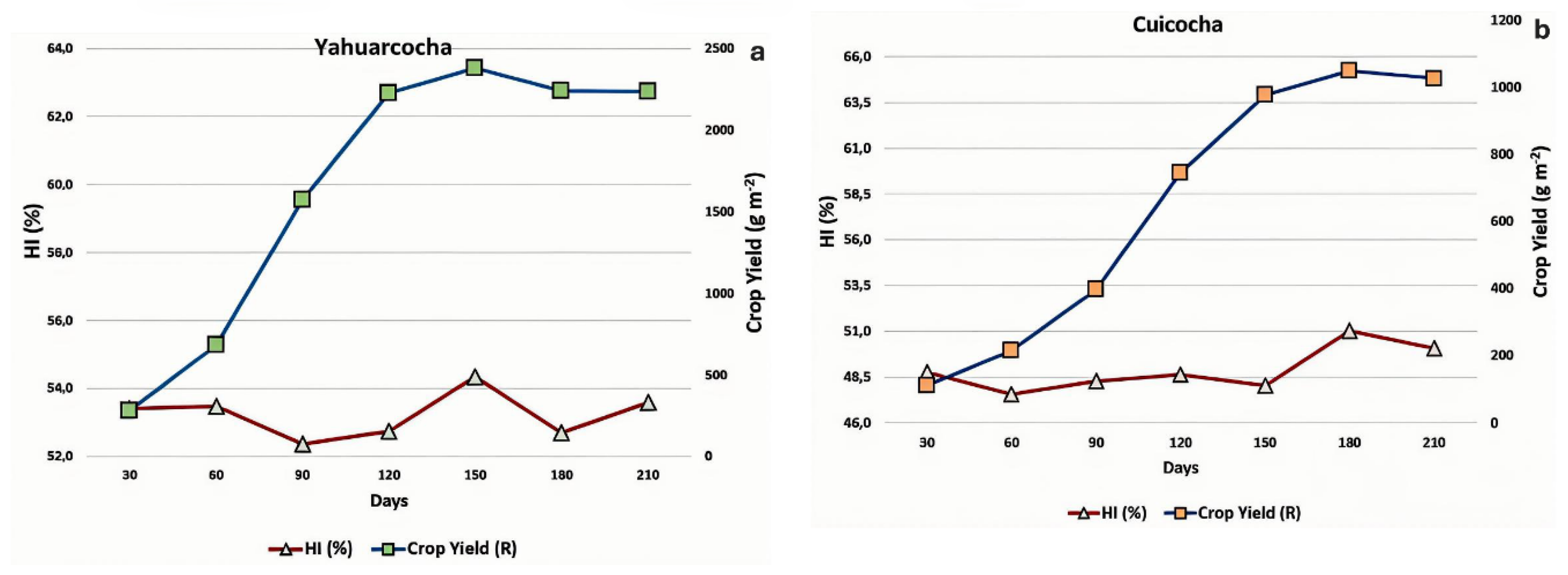

- Harvest Index (HI): ratio between the yield of the harvestable organ and the plant biomass [23].

- Crop Yield (R): product of biomass and the harvest index (HI) [23].

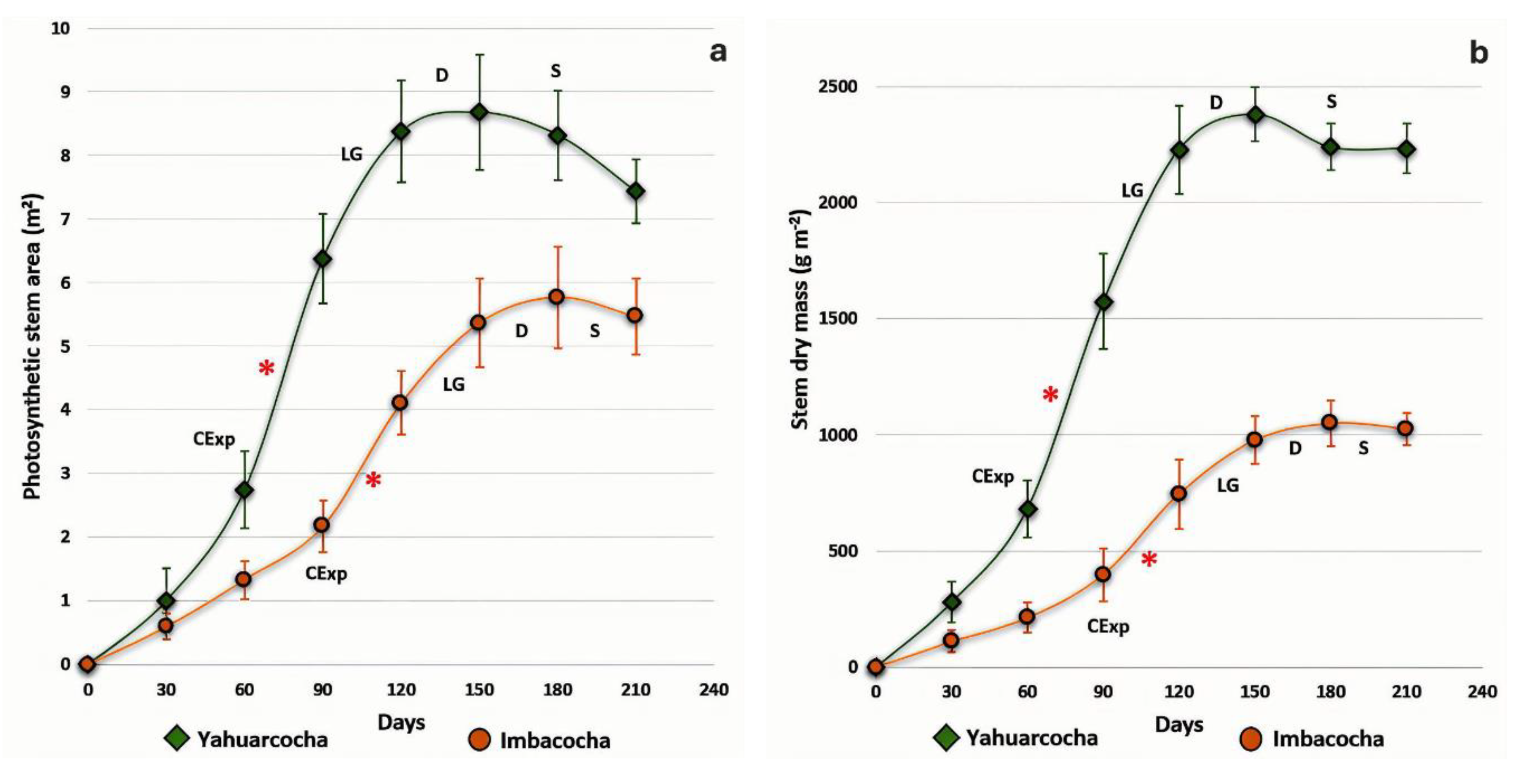

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simbaña, A. La totora y el desarrollo sustentable del Imbakucha, Lago San Pablo, se fortalece [Totora and the Sustainable Development of Imbakucha, Lake San Pablo, is Strengthened] [in Spanish]. AXIOMA 2015, 1, 6. https://axioma.pucesi.edu.ec/index.php/axioma/article/view/17.

- Paredes, R.; Hopkins, A.L. Dynamism in Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Persistence and Change in the Use of Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus) for Subsistence in Huanchaco, Peru. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2018, 9(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Alvarado, R.; Flores, J.; Zurita, F. Suitability of Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus (C.A. Mey.) Soják) for its use in constructed wetlands in areas polluted with heavy metals. Sustainability 2019, 11(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Cordero, J.F.; Němec, M.; Castro, P.H.; Hájková, K.; Castro, A.O.; Hýsek, Š. Macromolecular composition of Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus C.A. Mey, Soják) stem and its correlation with stem mechanical properties. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rito, M.; Borrelli, N.; Natal, M.; Fernández Honaine, M. Schoenoplectus californicus (Cyperaceae) amorphous silica contribution to the silicon cycle in Pampean shallow lakes: an analysis of spatio-temporal variation and silicon–lignin relations. Aust. J. Bot. 2024, 72, BT23084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, D.A.; Long, P.R.; Gutierrez Tito, E.R.; Moreno Terrazas, E.G.; Gosler, A.G. Trends in the area of suitable breeding habitat for the Endangered Lake Titicaca Grebe Rollandia microptera, 2001–2020. Bird Conserv. Int. 2023, 33, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaj, V.; Conde, D.; Rodríguez-Gallego, L.; Kandus, P. Postharvest growth dynamic of Schoenoplectus californicus along fluvio-estuarine and flooding gradients. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 26, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, J.A.; Paqualini, J.P.; Rodrigues, L.R. Root growth and nutrient removal of Typha domingensis and Schoenoplectus californicus over the period of plant establishment in a constructed floating wetland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8927–8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiser, C. The Totora (Scirpus californicus) in Ecuador and Peru. Econ. Bot. 1978, 32, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terneus Jácome, E. Vegetación acuática y estado trófico de las lagunas andinas de San Pablo y Yahuarcocha, provincia de Imbabura, Ecuador [Aquatic Vegetation and Trophic Status of the Andean Lagoons of San Pablo and Yahuarcocha, Imbabura Province, Ecuador] [in Spanish]. Rev. Ecuat. Med. Cienc. Biol. 2017, 35, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Cordero, J.F.; García-Navarro, J. Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus (C.A. Mey.) Soják) and its potential as a construction material. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, M.W.; Willis, J.M.; Sloey, T.M. Field assessment of environmental factors constraining the development and expansion of Schoenoplectus californicus marsh at a California tidal freshwater restoration site. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 24, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Yang, S.; Gong, H.; Xu, R.; Yao, X.; Ge, G. Interactive Effects of Flooding Duration and Sediment Texture on the Growth and Adaptation of Three Plant Species in the Poyang Lake Wetland. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12(7), 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo Cordero, J.F.; García Navarro, J. Review on the traditional uses and potential of Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus) as construction material. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245(2), 022068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, A.; Cadena, M.; Ontaneda, D. Diversidad fitoplanctónica y estado trófico actual de un lago de alta montaña en la provincia de Imbabura, Ecuador. ACI Av. Cienc. Ing. 2025, 17(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, W.A.; Achá, D. Allometric determinations in the early development of Schoenoplectus californicus to monitor nutrient uptake in constructed wetlands. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2025, 25(1), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macía, M.J.; Balslev, H. Use and management of Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus, Cyperaceae) in Ecuador. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54(1), 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banack, S.A.; Rondón, X.J.; Diaz-Huamanchumo, W. COVER ARTICLE: Indigenous Cultivation and Conservation of Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus, Cyperaceae) in Peru. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo Acuña, L.A.; Córdoba Sánchez, M.P. Bioindication and phytostabilization of potentially toxic elements by Schoenoplectus californicus in a Ramsar urban wetland, Colombia. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2025, ahead of print, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Murray-Gulde, C.L.; Huddleston, G.M.; Garber, K.V.; et al. Contributions of Schoenoplectus californicus in a constructed wetland system receiving copper-contaminated wastewater. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2005, 163, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H. Plant growth analysis: towards a synthesis of the classical and the functional approach. Physiol. Plant. 1989, 75(2), 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, F.P.; Pearce, R.B.; Mitchell, R.L. Physiology of Crop Plants, 2nd ed.; Scientific Publishers: Jodhpur, India, 2017; 327 pp.

- Hunt, R.; Causton, D.R.; Shipley, B.; Askew, A.P. A modern tool for classical plant growth analysis. Ann. Bot. 2002, 90(4), 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessmer, O.L.; et al. Functional approach to high throughput plant growth analysis. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7 (Suppl. 6), S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, A.; Tognetti, J. Técnicas de análisis de crecimiento de plantas: su aplicación a cultivos intensivos. RIA. Rev. Investig. Agropecu. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86449712008. 2016, 42(3), 258–282. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, M.E.; Plaza de los Reyes, C.; Pozo, G.; Villamar, C.A.; Vidal, G. Growth and nutrient uptake by Schoenoplectus californicus in a constructed wetland fed with swine slurry. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 12(3), 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hýsková, P.; Gaff, M.; Hidalgo-Cordero, J.F.; Hýsek, Š. Composite materials from totora (Schoenoplectus californicus C.A. Mey, Soják): Is it worth it? Compos. Struct. 2020, 232, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnaire, F.; Valladares, F., Eds. Functional Plant Ecology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Villar, R.; Ruiz-Robleto, J.; Quero, J.; Poorter, H.; Valladares, F.; Marañón, T. Tasas de crecimiento en especies leñosas: aspectos funcionales e implicaciones ecológicas [Growth Rates in Woody Species: Functional Aspects and Ecological Implications] [in Spanish]. In Ecología del bosque mediterráneo en un mundo cambiante, 2nd ed.; Valladares, F., Ed.; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 193–230.

- Evans, G.C. The Quantitative Analysis of Plant Growth; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1972; xxvi + 734 pp.

- Lambers, H.; Poorter, H. Inherent variation in growth rate between higher plants: A search for physiological causes and ecological consequences. In Advances in Ecological Research; Begon, M., Fitter, A.H., Eds.; Academic Press: London, U.K., 1992; Volume 23, pp. 187–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Garnier, E. Plant growth analysis: an evaluation of experimental design and computational methods. J. Exp. Bot. 1996, 47(9), 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P.; Hunt, R. Relative Growth-Rate: Its Range and Adaptive Significance in a Local Flora. J. Ecol. 1975, 63(2), 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Remkes, C. Leaf area ratio and net assimilation rate of 24 wild species differing in relative growth rate. Oecologia 1990, 83(4), 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntier, J.G.; Gomez, I.A. Análisis del crecimiento vegetativo del amancay (Alstroemeria aurantiaca D. Don) en dos poblaciones naturales [Vegetative Growth Analysis of Amancay (Alstroemeria aurantiaca D. Don) in Two Natural Populations] [in Spanish]. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1988, 61, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter, H.; Niklas, K.J.; Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Poot, P.; Mommer, L. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 2012, 193(1), 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, W.A.; Poorter, H. Avoiding Bias in Calculations of Relative Growth Rate. Ann. Bot. 2002, 90(1), 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorter, H.; De Jong, R. A comparison of specific leaf area, chemical composition and leaf construction costs of field plants from 15 habitats differing in productivity. New Phytol. 1999, 143(1), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Castellanos, M.; Segura Abril, M.; Ñústez López, C.E. Análisis de crecimiento y relación fuente-demanda de cuatro variedades de papa (Solanum tuberosum L.) en el municipio de Zipaquirá (Cundinamarca, Colombia). Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2010, 63(1), 5253–5266. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, B. Net Assimilation Rate, Specific Leaf Area and Leaf Mass Ratio: Which Is Most Closely Correlated with Relative Growth Rate? A Meta-Analysis. Funct. Ecol. 2006, 20(4), 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabón, G.; Rodés, R.; Pérez, L.; Vásquez, L.; Ortega, E. Relaciones morfológicas en Schoenoplectus californicus (Cyperaceae) en lagos alto-andinos de Ecuador [Morphological Relationships in Schoenoplectus californicus (Cyperaceae) in High-Andean Lakes of Ecuador] [in Spanish]. Rev. Jardín Botánico Nac. 2019, 40, 109–119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26937052.

- Hidalgo-Cordero, J.F.; Němec, M.; Castro, P.H.; Hájková, K.; Castro, A.O.; Hýsek, Š. Composición macromolecular del tallo de Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus C.A. Mey, Soják) y su correlación con las propiedades mecánicas del tallo. Rev. Fibras Nat. 2023, 20(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R. Basic Growth Analysis. Plant Growth Analysis for Beginners; Unwin Hyman: London, U.K., 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, B. Trade-offs between net assimilation rate and specific leaf area in determining relative growth rate: relationship with daily irradiance. Funct. Ecol. 2002, 16(5), 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.; Osborne, C.P.; Woodward, F.I.; Hulme, S.P.; Turnbull, L.A.; Taylor, S.H. Partitioning the components of relative growth rate: how important is plant size variation? Am. Nat. 2010, 176(6), E152–E161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Schmid, B.; Wang, F.; Paine, C.E.T. Net assimilation rate determines the growth rates of 14 species of subtropical forest trees. PLoS ONE 2016, 11(3), e0150644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yuan, G.; Cao, T.; Ni, L.; Li, W.; Zhu, G. Relationships between relative growth rate and its components across 11 submersed macrophytes. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2012, 27(4), 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medek, D.E.; Ball, M.C.; Schortemeyer, M. Relative contributions of leaf area ratio and net assimilation rate to change in growth rate depend on growth temperature: comparative analysis of subantarctic and alpine grasses. New Phytol. 2007, 175(3), 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.J.; Westoby, M. Cross-species relationships between seedling relative growth rate, nitrogen productivity and root vs leaf function in 28 Australian woody species. Funct. Ecol. 2000, 14(1), 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, D.; Sepúlveda, M.; Vidal, G. Phragmites australis and Schoenoplectus californicus in constructed wetlands: Development and nutrient uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 16(3), 763–777. http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-95162016000300015.

- Rigotti, J.A.; Paqualini, J.P.; Rodrigues, L.R. Root Growth and Nutrient Removal of Typha domingensis and Schoenoplectus californicus over the Period of Plant Establishment in a Constructed Floating Wetland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8927–8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejmankova, E. The role of macrophytes in wetland ecosystems. J. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 34, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotikarn, P.; Pramneechote, P.; Sinutok, S. Photosynthetic Responses of Freshwater Macrophytes to the Daily Light Cycle in Songkhla Lagoon. Plants 2022, 11, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, K.; Makaju, S.; Ibrahim, R.; Missaoui, A. Current Progress in Nitrogen Fixing Plants and Microbiome Research. Plants 2020, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vymazal, J. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2010, 2, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaj, V. Extracción de “juncos” de Schoenoplectus californicus en el Área Protegida Humedales de Santa Lucía (Uruguay): contexto ecológico, socio–espacial y perspectivas de manejo sustentable [Harvesting of Schoenoplectus californicus Reeds in the Santa Lucía Wetlands Protected Area (Uruguay): Ecological, Socio-Spatial Context and Sustainable Management Perspectives] [in Spanish]. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay, 2011. Available online: https://www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12008/3910/1/uy24-15287.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Feng, S. Effect of Plant Harvesting on the Performance of Constructed Wetlands during Summer. Water 2016, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, T.C.L.; Rodrigues, G.G.; Souza, G.P.C. de; Würdig, N.L. Effects of cutting disturbance in Schoenoplectus californicus (C.A. Mey.) Soják on the benthic macroinvertebrates. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2011, 33, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhofstad, M.J.J.M.; Poelen, M.D.M.; van Kempen, M.M.L.; Bakker, E.S.; Smolders, A.J.P. Finding the harvesting frequency to maximize nutrient removal in a constructed wetland dominated by submerged aquatic plants. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 106, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhao, Q.; Qiu, P.; Chang, J.; Peng, L.; Wang, S.; Hong, Y.; Liu, G.-J. Plant trait–environment trends and their conservation implications for riparian wetlands in the Yellow River. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, A.; Apaseev, V.; Maksimov, E.; Alekseev, N.; Pushkarenko, N.; Maksimov, N. Towards a mathematical model of plant growth. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: 2021; Volume 935, 012031. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, G.; Singh, A.; et al. Macrophytes for Utilization in Constructed Wetland as Efficient Species for Phytoremediation of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater. Wetlands 2024, 44, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, K.; Hossain, T.; Haque Mou, T.; Ali, A.; Islam, M. Effect of Nitrogen On Growth and Yield of Chili (Capsicum annuum L.) in Roof Top Garden. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelna-Tarín, S.; Romero-Félix, C.S.; Bojórquez-Ramos, C.; Lugo-García, G.A.; Sánchez-Soto, B.H. Bioestimulantes y solución Steiner en crecimiento y producción de Capsicum annuum L. [Biostimulants and Steiner solution in growth and production of Capsicum annuum L.] [in Spanish]. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2024, 15, e3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Bravo, F.; Monge-Palma, J.I. Comportamiento morfofisiológico y productivo de chile dulce hidropónico en invernadero con diferentes estrategias de manejo del fertirriego [Morphophysiological and productive performance of hydroponic sweet pepper in greenhouse with different fertigation management strategies] [in Spanish]. Agron. Costarric. 2023, 47, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzidis, A.; Kadoglidou, K.; Mylonas, I.; Ghoghoberidze, S.; Ninou, E.; Katsantonis, D. Investigating the Impact of Tillering on Yield and Yield-Related Traits in European Rice Cultivars. Agriculture 2025, 15, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, D.G.; Martínez Racines, C.P.; Motta, F.O., Eds. Producción ecoeficiente del arroz en América Latina [Eco-Efficient Rice Production in Latin America] [in Spanish]; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT): Cali, Colombia, 2010; CIAT Publicación No. 365, 487p.

- Ntanos, D.A.; Koutroubas, S.D. Dry matter and N accumulation and translocation for Indica and Japonica rice under Mediterranean conditions. Field Crops Res. 2002, 74, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Okuda, T.; Abdullah, M.; Awang, M.; Furukawa, A. The leaf development process and its significance for reducing self-shading of a tropical pioneer tree species. Oecologia 2000, 125, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi, H.; Nakabayashi, M.; Yamada, T. Newly found leaf arrangement to reduce self-shading within a crown in Japanese monoaxial tree species. J. Plant Res. 2024, 137, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratolongo, P.; Kandus, P.; Brinson, M.M. Net aboveground primary production and biomass dynamics of Schoenoplectus californicus (Cyperaceae) marshes growing under different hydrological conditions. Darwiniana 2008, 46(2), 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Cordero, J.F.; Aza-Medina, L.C. Analysis of the thermal performance of elements made with totora using different production processes. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 65, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Hefting, M.M.; Soons, M.B.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Rees, M.; Hector, A.; Turnbull, L.A.; Zhou, X.; Guo, Z.; Chu, C.; Du, G.; Hautier, Y. Fast and furious: Early differences in growth rate drive short term plant dominance and exclusion under eutrophication. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10(18), 10116–10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, P.D. Effects of plant growth rate and leaf lifetime on the amount and type of anti-herbivore defense. Oecologia 1988, 74, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, K.; Fenner, M. Ecology of seedling regeneration. In Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities, 2nd ed.; Fenner, M., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 331–359. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T.; Franck, T.; Bisbis, B.; Kevers, C.; Jouve, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Dommes, J. Concepts in plant stress physiology. Application to plant tissue cultures. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 37(3), 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Cortez, J.S.; Shipley, B.; Arnason, J.T. Do plant species with high relative growth rates have poorer chemical defences? Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13(6), 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; He, A.; Wang, W.; Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Nie, L. Comparisons of regeneration rate and yields performance between inbred and hybrid rice cultivars in a direct seeding rice-ratoon rice system in central China. Field Crops Res. 2018, 223, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloey, T.M.; Hester, M.W. Impact of nitrogen and importance of silicon on mechanical stem strength in Schoenoplectus acutus and S. californicus: Applications for restoration. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 26, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, C.L.; Keddy, P.A. Competitive performance and species distribution in shoreline plant communities: A comparative approach. Ecology 1995, 76(1), 280–291. https://drpaulkeddy.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/gaudet-and-keddy-1995-ecology-competitive-performance-and-species-distribution-in-shoreline-plant-communities.pdf.

- Grime, J.P. Plant Strategies, Vegetation Processes, and Ecosystem Properties, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Robleto, J.; Villar, R. Relative growth rate and biomass allocation in ten woody species with different leaf longevity using phylogenetic independent contrasts (PICs). Plant Biol. 2005, 7(5), 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorter, H.; van der Werf, A. Is inherent variation in RGR determined by LAR at low irradiance and by NAR at high irradiance? A review of herbaceous species. In Inherent Variation in Plant Growth. Physiological Mechanisms and Ecological Consequences; Lambers, H., Poorter, H., van Vuuren, M.M.I., Eds.; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Westoby, M.; Falster, D.S.; Moles, A.T.; Vesk, P.A.; Wright, I.J. Plant ecological strategies: Some leading dimensions of variation between species. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovsholt, L.J.; Matheson, F.; Riis, T.; Hawes, I. Trait-specific groups of aquatic macrophytes respond differently to eutrophication of unshaded lowland streams. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osone, Y.; Ishida, A.; Tateno, M. The correlation between relative growth rate and specific leaf area requires associations of specific leaf area with root nitrogen absorption rate. New Phytol. 2008, 179(2), 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Checa, R.; Pérez-Jordán, H.; García-Gómez, H.; Prieto-Benítez, S.; Gónzalez-Fernández, I.; Alonso, R. Foliar nitrogen uptake in broadleaf evergreen Mediterranean forests: Fertilisation experiment with labelled nitrogen. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambers, H.; Chapin, F.S.; Pons, T.L. Plant Physiological Ecology, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wen, H.; Suprun, A.; Zhu, H. Ethylene Signaling in Regulating Plant Growth, Development, and Stress Responses. Plants 2025, 14(3), 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.J.; Voesenek, L.A. Aclimatación a la inundación del suelo: detección y transducción de señales. In Root Physiology: From Gene to Function; Lambers, H., Colmer, T.D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhao, J.; Fu, Q. Quantitative Relationship of Plant Height and Leaf Area Index of Spring Maize under Different Water and Nitrogen Treatments Based on Effective Accumulated Temperature. Agronomy 2024, 14(5), 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, M.J.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Weightman, R.; Snape, J.W. Identifying physiological traits associated with improved drought resistance in winter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2007, 103(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.M.; Evans, L.T. Photosynthesis, carbon partitioning, and yield. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1981, 32, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, J.; Orellana, F.; Searles, P.; et al. Supplemental irrigation during the critical period for yield ensures higher radiation capture and use efficiency, water use efficiency, and grain yield in chia. Preprint 2023, Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Golubkov, M.; Golubkov, S. The role of total phosphorus in eutrophication of freshwater and brackish-water parts of the Neva River estuary (Baltic Sea). Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 209, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, D.L. The role of phosphorus in the eutrophication of receiving waters: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 1998, 27(2), 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.F.; Stafford Smith, D.M.; Lambin, E.F.; et al. Global Desertification: Building a Science for Dryland Development. Science 2007, 316, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Zavaleta, E.S.; Eviner, V.T.; et al. Consecuencias del cambio de la biodiversidad. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Growth Index | Symbol | Average Value over a Time Interval (t₂ - t₁) | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Growth Rate | RGR |  |

g g-1 day-1 |

| Absolute Growth Rate | AGR |  |

g day-1 |

| Net Assimilation Rate | NAR |  |

g m-2 day-1 |

| Leaf Area Ratio | LAR |  |

cm2 g-1 |

| Leaf Weight Ratio | LWR |  |

g g-1 |

| Specific Leaf Area | SLA |  |

cm2 g-1 |

| Leaf Area Index | LAI |  |

Dimensionless |

| Harvest Index | HI | % | |

| Crop Yield | R | g m-2 |

| Schoenoplectus californicus in Lakes Yahuarcocha and Imbacocha | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | Photosynthetic Area PA (m²) |

Stem Dry Mass (g m⁻²) |

Total Plant Dry Mass (g m⁻²) | |||

| Yah 1 | Imb 1 | Yah 1 | Imb 1 | Yah 1 | Imb 1 | |

| 30 | 1.01 ± 0.51 | 0.60 ± 0.15 | 280 ± 88 | 110 ± 47 | 508 ± 19 | 223 ± 18 |

| 60 | 2.75 ± 0.59 | 1.33 ± 0.28 | 682 ± 121 | 214 ± 63 | 1,283 ± 55 | 448 ± 29 |

| 90 | 6.37 ± 0.70 | 2.18 ± 0.42 | 1,575 ± 206 | 397 ± 115 | 3,005 ± 23 | 837 ± 59 |

| 120 | 8.38 ± 0.83 | 4.11 ± 0.45 | 2,228 ± 188 | 745 ± 148 | 4,222 ± 54 | 1,537 ± 62 |

| 150 | 8.68 ± 0.85 | 5.37 ± 0.66 | 2,380 ± 116 | 977 ± 103 | 4,390 ± 253 | 2,038 ± 123 |

| 180 | 8.32 ± 0.70 | 5.77 ± 0.77 | 2,240 ± 100 | 1,050 ± 99 | 4,253 ± 81 | 2,068 ± 177 |

| 210 | 7.44 ± 0.52 | 5.47 ± 0.62 | 2,234 ± 108 | 1,026 ± 69 | 4,168 ± 86 | 2,061 ± 165 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).