Introduction

Trypanosoma cruzi is the etiological agent of Chagas disease, a neglected condition [

1]. The acute infection is followed by a potent immune response that controls the parasite's growth [

2]. However, the host can not clear the parasite, and a chronic infection is established [

2]. A wide range of immune responses can be detected during the acute phase of the disease, helping to keep parasite growth in check [

2]. Yet, most of the lymphocyte response is polyclonal and may occur through bystander activation [

3]. However, it has been proposed that T cell receptors are cross-reactive to a large extent [

4]. Several molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain TCR cross-reactivity in various models [

5]. In addition, peripheral T cells might express two distinct TCRs in mice and humans, denoted as double TCR-expressors [

6]. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that T cell cross-reactivity may be one of the reasons to justify the polyclonal T cell activation during

T. cruzi infection. Cross-reactivity may have important immunological implications. For instance, T cells are positively selected in the thymus by self-peptides and MHC. They may yet interact with and produce immune responses to non-self peptides in the peripheral lymphoid organs [

5,

7]. Importantly, infections can trigger and expand clones that cross-react with self-antigens, thereby causing autoimmune diseases [

8,

9].

On the other hand, cross-reactivity may help to develop vaccines to prevent or ameliorate autoimmune diseases. For instance, it has been reported that non-self heat shock protein-derived peptides may activate cross-reactive regulatory T cells, thereby preventing autoimmune diseases [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, prior contact with pathogens or non-pathogenic microflora can modify the immune response to an unrelated microorganism, as previously documented [

9,

13]. For example, we have previously described how aged or thymectomized mice are completely resistant to infection with

T. cruzi, whereas young mice are susceptible [

14,

15]. Resistance, in that case, correlated with the increase of naturally occurring memory T cells in these animals at the moment of infection, suggesting that environmental antigen-reactive T cells may help control the parasite load by responding to

T. cruzi antigens through cross-reactivity [

2]. Interestingly, a high degree of cross-reactivity between different CD8 T cell clones and

T. cruzi antigen-derived peptides has recently been demonstrated [

16]. Together, these findings might help explain important aspects of Chagas disease pathogenicity. Yet, there is no clear information on the cross-reactivity of CD4+ T cells with class II MHC during

T. cruzi infection, in part due to the lack of reagents such as stable MHC class II-peptide tetramers.

In this study, we have described the phenotypes and functional changes of the DO11.10 transgenic CD4+ T cell, which bears the TCR recognized by the clonotypic monoclonal antibody KJ1-26, during acute

T. cruzi infection. Originally, the DO11.10 transgenic TCR is specific for an Ovalbumin-derived peptide (323-339) in the context of IA

d class II MHC [

17]. Therefore, the activation of DO11.10 transgenic CD4+ T cells to a multitude of unrelated antigens, such as

T. cruzi, is somewhat surprising. We demonstrate that DO11.10 transgenic CD4 T cells are largely activated to an effector memory phenotype during the acute

T. cruzi infection in BALB/c mice. The percentage of transgenic T cells expressing IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10 also increases in the acute phase. Previous oral immunization with OVA altered the cytokine profile of DO11.10 CD4 T cells, increasing the percentage of IL-10-expressing cells. Additionally, some DO11.10 CD4 T cells begin to express Foxp3. These results suggest that cross-reactivity between CD4 T cells and class II MHC peptides may be similar to the CD8 T cell compartment and peptides related to class I MHC. These findings might have profound implications for the quality of the immune response during the infection.

Results

Frequencies of transgenic DO11.10 CD4 T cells during acute T. cruzi infection. To test whether signs of cross-reactivity could also be observed in CD4 T cells, we infected DO11.10 transgenic mice with

T. cruzi.

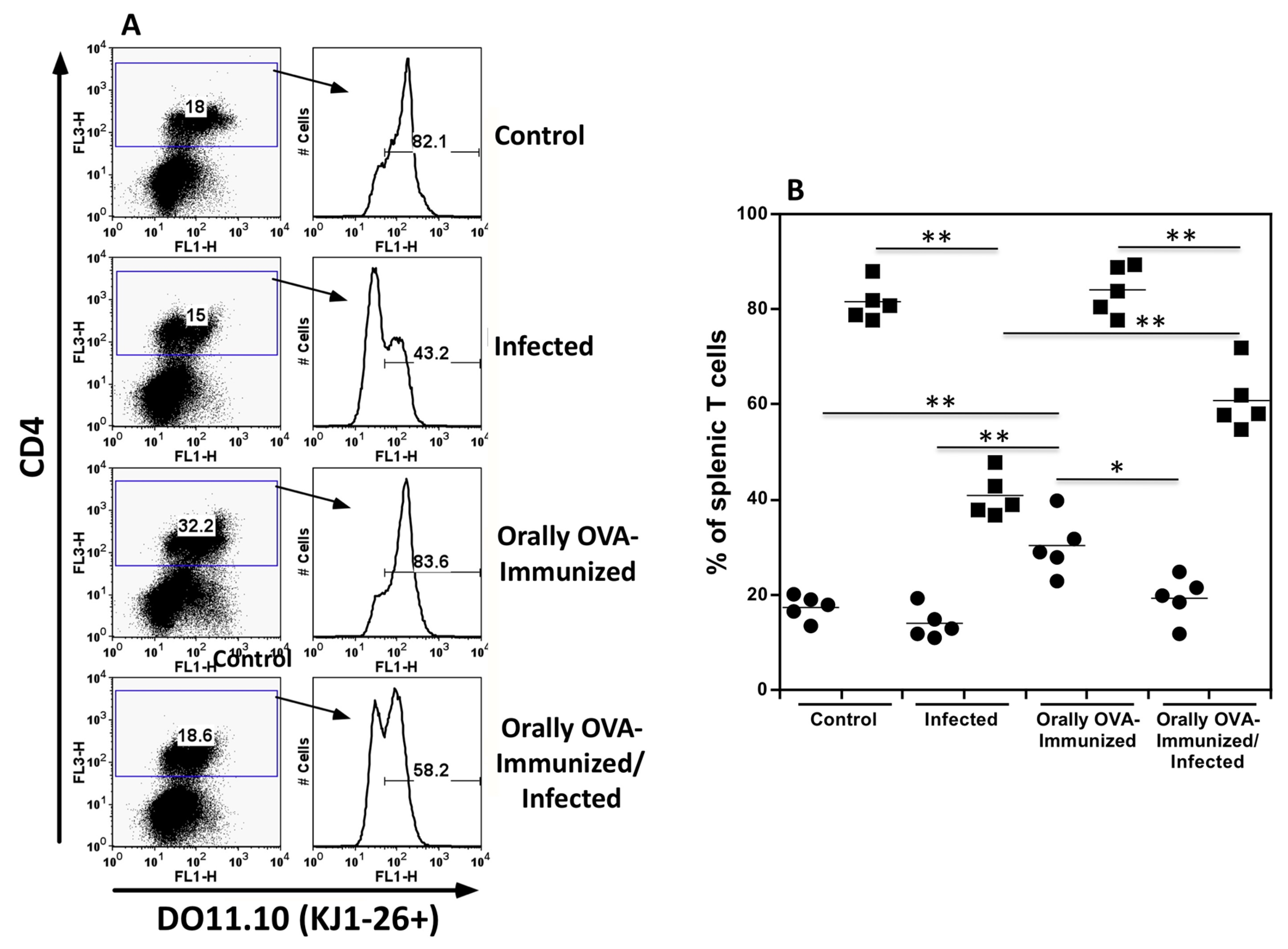

Figure 1A shows representative dot plots of splenic CD4

+KJ1-26

+ T cells from different experimental groups.

Figure 1B shows the frequencies of total splenic CD4+ T cells (closed circles) and CD4

+KJ1-26

+ transgenic T cells (closed squares) from individual mice in various experimental groups. Transgenic DO11.10 CD4

+ T cells comprise the majority of splenic CD4 T cells in control mice. The same situation was observed for mice previously immunized with OVA. However,

T. cruzi-infected mice showed smaller frequencies of transgenic T cells in the CD4

+ T cell population within 25 days after infection. OVA immunization significantly prevents the diminution of DO11.10 transgenic T cells in the overall CD4

+ T cell population, indicating that antigen-experienced transgenic T cells may be better preserved during acute infection. Please note that the fluorescence intensity of KJ1-26 staining was slightly lower in infected mice, indicating some degree of activation. Low expression of the transgenic DO11.10 TCR has been reported following antigen-specific activation [

21,

22]. In addition, lower expression of alpha-beta TCR and CD3 molecules is observed in polyclonal T cells from normal mice during acute infection, indicating T cell activation (data not shown). Therefore, these results suggest that DO11.10 transgenic CD4

+ T cells may interact with

T. cruzi antigens and become activated during acute infection. It is also interesting that a large proportion of transgenic T cells become negative for the KJ1-26 clonotype, indicating that an endogenous alpha chain has been rearranged and that a second TCR is expressed on these cells. This situation has been described before for DO11.10 transgenic mice [

22,

23]. In fact, a large proportion of CD4

+ KJ1-26

- T cells lack the expression of the CD62L molecule, indicating they are effector memory T cells (

supplementary Figure 1)

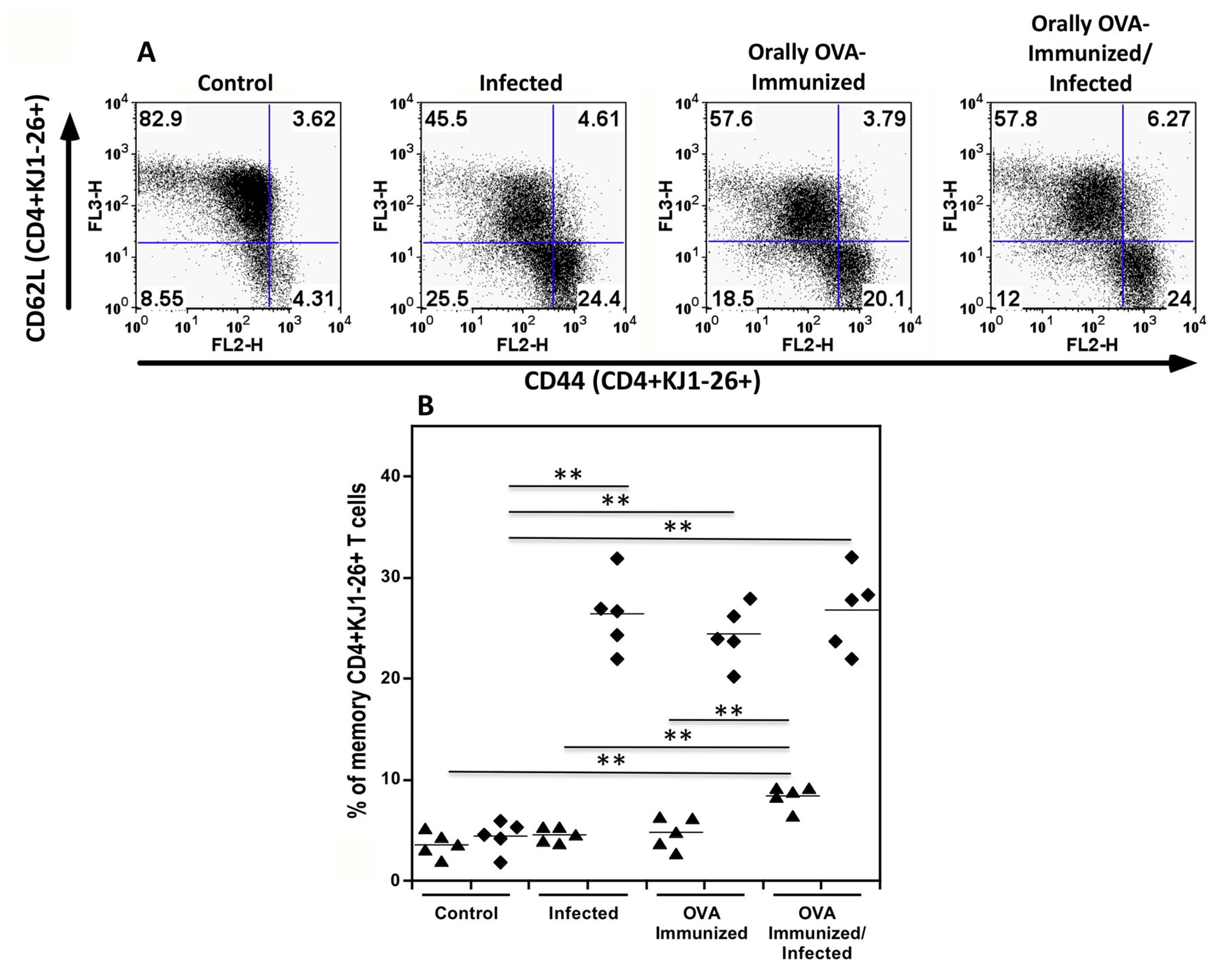

DO11.10 transgenic CD4+ T cells are activated to effector memory lymphocytes during the acute T. cruzi infection. To better explore the hypotheses above, flow cytometric analysis of sorted splenic KJ1-26

+CD4

+ T cells from infected DO11.10 mice revealed a significant increase in the percentage of memory T cells when compared with control mice.

Figure 2A and 2B show that DO11.10

+CD4

+ T cells from normal mice are predominantly in the resting stage, exhibiting low percentages of markers associated with memory T cells. On the other hand, OVA immunization or infection of DO11.10 transgenic mice increased the rate of effector memory transgenic T cells, expressing high levels of CD44 and low levels of CD62L (closed diamonds). Previous immunization with OVA also increases the percentage of central memory transgenic CD4

+ T cells (closed triangles) after infection, compared to the other groups.

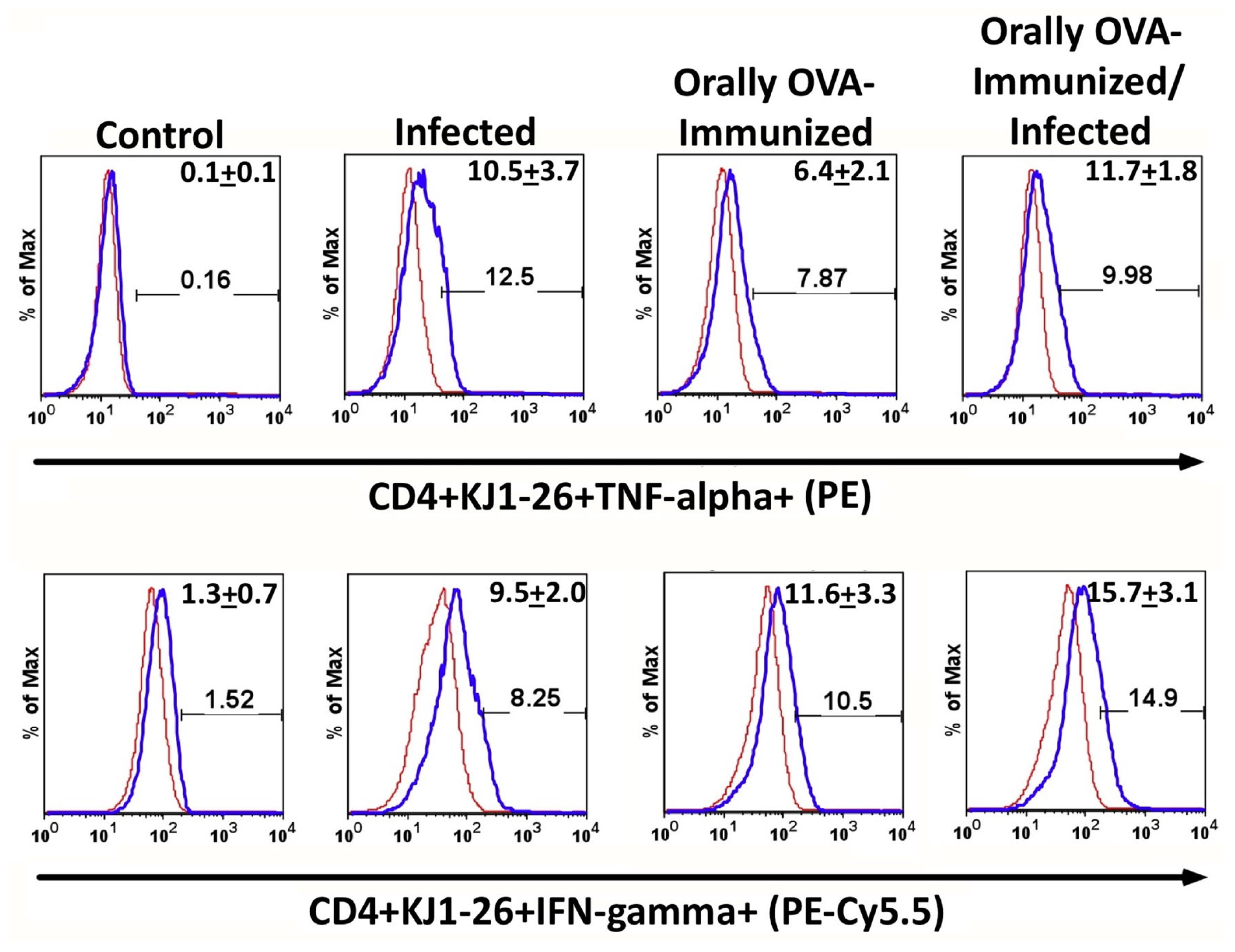

T. cruzi infection increases the frequencies of splenic TNF-α+ and IFN-γ+ DO11.10 transgenic T cells. To further characterize these activated cells, intracellular cytokine staining was performed. Infection with

T. cruzi increased the frequencies of CD4

+KJ1-26

+ cells that spontaneously expressed TNF-α after 24 hours of culture in complete medium, as shown in

Figure 3 (upper histogram set). Previous OVA immunization also augments spontaneous TNF-α production compared with non-immunized controls. However, the infection did not increase the frequency of transgenic splenic T cells expressing TNF-α in OVA-immunized animals compared with the OVA-immunized group.

The frequencies of transgenic splenic T cells, which spontaneously produce IFN-γ, increase upon infection compared to uninfected mice and are similar to those of mice previously immunized with OVA. In addition, infection in OVA-immunized mice does not further augment the percentages of transgenic T cells that produce IFN-γ. These results suggest that prior OVA immunization has set a limit on the production of TNF-α and IFN-γ induced by T. cruzi infection.

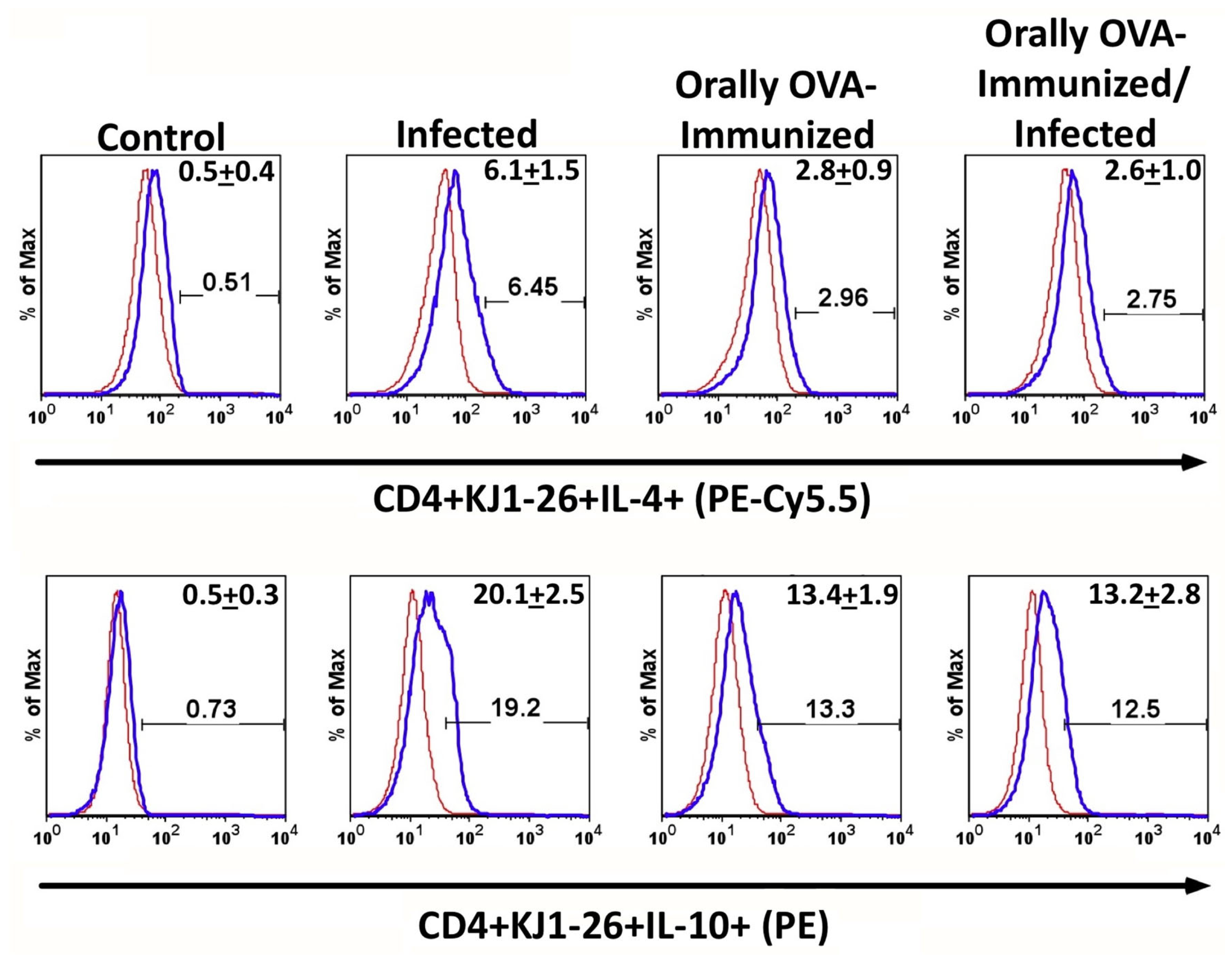

DO11.10 transgenic CD4+ T cells spontaneously produce IL-4 and IL-10 upon T. cruzi infection. To assess whether

T. cruzi infection could induce the production of regulatory cytokines, we evaluated IL-4 and IL-10 in naïve mice and in mice orally exposed to OVA before infection.

Figure 4 shows that transgenic CD4

+ T splenocytes from infected mice displayed higher frequencies of IL-4- and IL-10-expressing cells than unstimulated controls. Additionally, previous OVA immunization significantly increased the frequency of IL-4

+ cells compared to non-immunized animals. However, the infection did not augment the relative number of IL-4

+ cells in OVA-immunized mice. We have also studied the frequencies of IL-10 expression on transgenic CD4

+ T lymphocytes. The lower histograms in

Figure 4 show that infection increased the frequency of splenic IL-10 transgenic producers compared with control, OVA-immunized, or OVA-immunized-infected DO11.10 mice. Interestingly, pre-immunization with OVA significantly increased the frequencies of IL-10-producing transgenic T cells compared to non-immunized mice. However, these frequencies were still lower than those in infected non-immunized mice. These results suggest that prior oral exposure to OVA modulates the immune response of DO11.10 T cells, shifting them toward a more regulatory phenotype.

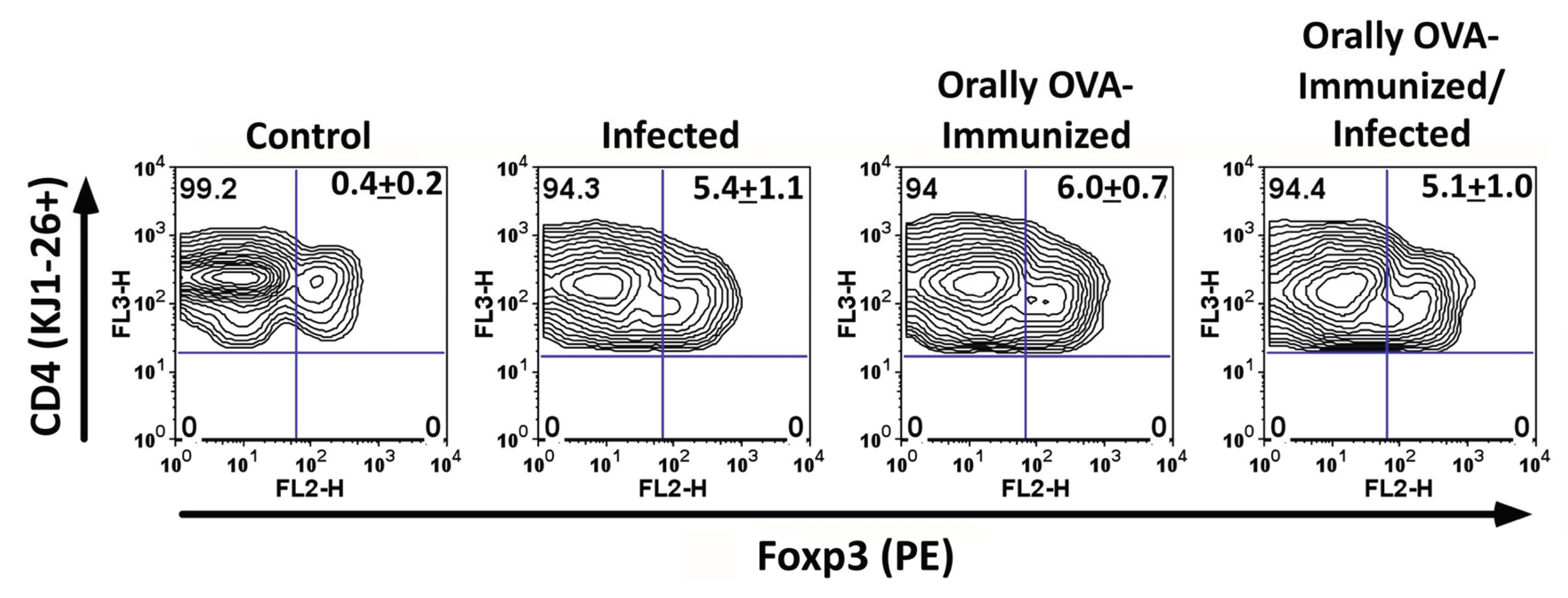

Induction of Foxp3 expression in DO11.10 CD4 T cells during infection. We also examined Foxp3 expression in DO11.10 CD4 T cells during acute

T. cruzi infection. A considerable proportion of KJ1-26+ CD4 T cells upregulated Foxp3 in infected mice (

Figure 5). Previous exposure to OVA also induced equivalent frequencies of transgenic T cells expressing Foxp-3, even in the presence of the infection. These results indicate that

T. cruzi infection can cause the differentiation of a subset of DO11.10 CD4 T cells into regulatory T cells, potentially contributing to immune regulation during infection.

Discussion

Cross-reactivity is a well-known characteristic of CD8 T cells during

T. cruzi infection [

16]. However, whether CD4 T cells also exhibit cross-reactivity in this context remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrate that DO11.10 CD4 T cells specific for OVA 323–339 in the context of IAd can be activated during acute

T. cruzi infection. These cells not only acquired an effector memory phenotype but also produced pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α. Moreover, a subset of these cells expressed IL-10 and Foxp3, suggesting the induction of a regulatory component.

The finding that DO11.10 CD4 T cells were activated in the absence of OVA strongly supports the hypothesis that cross-reactivity extends to CD4 T cells. These results are consistent with previous work demonstrating extensive TCR cross-reactivity in CD8 T cells [

4,

16]. Cross-reactivity may provide the immune system with flexibility to respond to a broad range of antigens. Still, it can also lead to potentially harmful outcomes, such as autoimmune reactions or the diversion of the immune response to less important antigens [

5,

7,

8].

It is also intriguing that upon

T. cruzi infection, the CD4

+DO11.10

+ transgenic T cells were reduced among total CD4

+ T lymphocytes. Although this result might appear paradoxical, it may suggest that transgenic T cells may be losing the TCR clonotype identified by the KJ1-26 mAb. In this case, this observation is indicative of transgenic T cell activation, because T cells may internalize their TCR upon cognate activation, as pointed out in the results section. In fact, a large number of CD4+ KJ1-26- T cells are activated and present an effector memory phenotype. In addition, one may hypothesize that mature transgenic T cells begin to reexpress RAG and thereby rearrange the endogenous alpha-chain, becoming double TCR-expressors. Although the TCR-revision has been described for some peripheral T cell populations in mice [

24,

25,

26], it has not been shown during

T. cruzi infection. It has been shown that one-third of peripheral T cells in humans are double TCR-expressors [

27], and numerous studies in mice show similar findings [

6]. Yet, curiously, very little information is available on the role or importance of double TCR-expressors in infections or autoimmune diseases. Regardless of the precise mechanism responsible for the downmodulation of the transgenic TCR, it was clear that a considerable proportion of CD4 T cells expressing the KJ1-26 clonotype become effector memory cells during the acute infection. This observation shows that

T. cruzi antigens also activate transgenic CD4 T cells, leading them to spontaneously produce cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10.

Interestingly, prior oral exposure to OVA modified the cytokine profile of DO11.10 CD4 T cells during infection, increasing the proportion of IL-10-producing cells. Oral antigen administration is known to promote regulatory T cell responses, and our findings suggest that prior antigen exposure can shape the outcome of cross-reactive responses during infection [

10,

11,

12]. This observation underscores the importance of environmental antigens in shaping immune responses to pathogens.

The induction of Foxp3 expression in DO11.10 CD4 T cells during infection further supports the idea that

T. cruzi can promote the differentiation of regulatory T cells. Regulatory T cells have been implicated in modulating the balance between protective immunity and immune-mediated pathology in Chagas disease [

2]. Thus, functional cross-reactivity in CD4 T cells may not only contribute to parasite persistence by diverting responses away from critical epitopes but also play a role in controlling immunopathology by favoring the appearance of Treg cells.

In summary, our results demonstrate that cross-reactivity in CD4+ T cells occurs during T. cruzi infection, a phenomenon similar to that observed in CD8+ T cells. This study expands our understanding of T cell responses in Chagas disease and suggests that both effector and regulatory outcomes of cross-reactivity may significantly influence the course of infection.