1. Introduction

Mental health is universally acknowledged as a fundamental human right for sustainable development. The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development asserts that mental well-being is not only a component of individual quality of life, but also a driving force behind economic growth and societal advancement [

1]. However, in rural settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, this ideal is far from reality. Adolescents in these regions face a convergence of structural barriers that severely restrict their access to mental health services. The absence of adequate health infrastructure creates significant gaps, while a chronic shortage of trained professionals exacerbates the crisis. Socioeconomic disparities, deeply entrenched and persistent, further amplify their vulnerability. Yet, within these challenging contexts, family and community strengths emerge as powerful counterforces. These protective factors, deeply embedded in the social fabric, provide critical emotional and psychological support, acting as buffers against the risks associated with the lack of specialized care [

2,

3].

Adolescent mental health, particularly within the scope of community nursing, is a profoundly intricate challenge. It arises from a web of interdependent factors that shape emotional well-being, demanding approaches that are both holistic and precise. Community nursing, by its very nature, delves into the nuanced interactions between individuals, their families, and the community at large. This interconnectedness cannot be overstated—social and familial environments wield a decisive influence, either fortifying mental health or compounding its fragility [

4,

5]. At the heart of this dynamic lie protective factors: open communication that fosters connection, emotional support that anchors stability, and parental supervision that offers guidance without constraint. These elements are far more than strategies; they are lifelines. They work not only to counteract the corrosive effects of risk factors but also to cultivate resilience. Adolescents find in them both refuge and strength—a duality that transforms vulnerability into growth. Such factors do more than shield; they fortify, empowering young individuals to navigate adversity with resolve and emerge with a reinforced sense of self [

6,

7].

The realm of community nursing stands at the crossroads of these challenges, its role as multifaceted as the issues it addresses. Adolescent mental health presents a particularly complex frontier, shaped by an intricate interplay of factors spanning the individual, family, and community spheres. Community nursing positions itself not as a reactive force but as a proactive bridge, weaving together these dimensions to cultivate health and well-being. The impact of family and social environments, long acknowledged in scholarly discourse, is fundamental here [

4,

5]. Communication that flows freely, emotional support that steadies turbulent waters, and supervision that empowers rather than constrains—all these elements fortify families, enabling adolescents to weather adversity and build enduring resilience [

6,

7].

Families in rural communities face a constellation of challenges that significantly hinder their ability to support adolescents. Economic disparities often loom large, compounding the geographic isolation that restricts access to critical resources such as educational programs and mental health services [

8]. These limitations are not just logistical, they are deeply structural, creating barriers that entrench inequities and amplify vulnerabilities. Yet, amidst these constraints, there is potential for transformation. Community nursing, with its dual focus on education and intervention, serves as a dynamic bridge. It connects families to health services, providing access and empowerment. By fostering locally driven strategies tailored to the community’s unique needs, nurses enable families to transcend the limitations of their environment, cultivating resilience and strengthening their capacity to nurture adolescent development [

9].

Our study approaches this issue through an innovative lens, employing the Photovoice methodology to explore parents’ perceptions of family strengths as protective factors for adolescent mental health [

10]. At its core, Photovoice is more than a research tool—it is a participatory process that merges the evocative power of photography with the introspection of personal narratives. This method allows participants to reflect on their lived experiences and also to communicate them in ways that are both visual and verbal, fostering deeper engagement and expression [

11]. But the methodology’s value extends far beyond data collection. It provides a platform for empowerment, turning parents from passive observers into active co-creators in the research process. This active participation does more than enhance the understanding of family dynamics in rural settings; it inspires agency, instilling a profound sense of ownership over the strategies crafted to confront mental health challenges. In doing so, it bridges the gap between research and action, ensuring that solutions are not only contextually relevant but also deeply rooted in the communities they aim to serve [

12].

In the rural communities of Loja, a province nestled in the southern region of Ecuador, family cohesion is not merely a support system—it is a cornerstone in the promotion of adolescent mental health. Parents identify a set of protective factors: effective communication that fosters understanding, the expression of affection that nurtures emotional security, supervision that provides guidance without constraint, and unwavering emotional support. These pillars are foundational, anchoring the psychological resilience and well-being of their children [

13] Yet, even amidst these strengths, adversity looms. Families face a triad of challenges: persistent financial limitations, the vast distances separating them from urban centers, and an alarming lack of access to mental health training programs [

10,

14]. Such obstacles are more than logistical; they are deeply systemic, compounding the vulnerabilities faced by these communities. Addressing these issues demands more than conventional solutions. It requires interventions that are tailored, grounded in the lived experiences of the local population, and rooted in the unique resources of the community itself. Only by integrating these contextual perspectives can mental health strategies become truly effective and sustainable.

Although adolescent mental health in rural settings is recognized as a public health problem, few studies have examined how families in low- and middle-income countries contribute to protecting adolescents’ well-being. Mostly the research focused on risk factors and deficiencies in service, without addressing the protective role of family functioning and parental perspectives. Furthermore, there is limited evidence using participatory qualitative approaches, such as Photovoice, which allows parents to express their lived experiences and identify culturally relevant strategies to strengthen adolescent mental health. This gap is particularly evident in rural areas of Ecuador, where geographic isolation, poverty, and limited access to mental health services pose additional challenges. Therefore, addressing this issue is essential for designing family-centered, community-led interventions tailored to these settings.

This study aimed to explore family functioning as a protective factor for adolescent mental health from the perspective of parents in rural communities of southern Ecuador, using Photovoice as a participatory research tool.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

The research design corresponds to Participatory Action Research. Five Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted to explore the meanings, aspirations, values and perceptions of parents about the family functioning as protective factors of mental health of adolescents. This study allowed us to deep in the subjectivity and living contexts of participants in rural areas of Ecuador. We considered the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) to develop this report [

15].

2.2. Theoretical Perspective

This research utilizes Bronfenbrenner’s Social Ecological Theory [

16], which asserts that the dynamic interaction between an individual and their environment shapes their behavior [

17]. Specifically, we focus on the microsystem, where the family serves as the immediate environment that influences adolescents. In rural communities, this framework highlights how parent-adolescent interactions play a critical role in shaping mental health outcomes.

Group reflections with parents revealed that fostering healthy family interactions and providing emotional support were essential in creating adolescents’ mental well-being. To deepen this analysis, we integrate the Calgary Family Assessment Model (CFAM) [

18], particularly its functional category. This component allowed us to explore how family dynamics act as protective factors for adolescents’ mental health. By examining interactions between parents and adolescents, we promoted discussions in which participants identified specific behaviors and practices that could contribute to resilience and mental health stability among the adolescents.

2.3. Study Participants

The study was performed in the Loja province, specifically in three rural communities Guara, Chaquizhca and Bellamaria. These communities are in the southern Andian region of Ecuador. A total of 29 parents of adolescents participated in the five FGDs.

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

Parents of adolescents living in rural communities and willingness to participate in the study.

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

Refusing to sign the information consent.

2.6. Data Collection in Focus Group and Photovoice

Data were collected in June 2022 during the Tropical Disease Research and Service-Learning program (TDR-2022), a collaboration between Ohio University and Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador. This program is characterized by its transdisciplinary approach. The initial contact was made through the natural leaders of the three participating rural communities who agreed on a date and time for the first meeting with the parents of the adolescents. The meeting proceeded with a presentation detailing the project’s objectives, participation guidelines, and ethical considerations of the research, emphasizing the voluntary and free nature of research participation.

2.7. Focus Group Procedure

A moderator and three non-participant observers led the research team, allowing them to enrich the construction of the analyses with the information obtained. We conducted the activity in schools with the permission of neighbors who hosted the meetings at their homes.

2.8. Photovoice Procedure

During the first meeting, parents of adolescents received instruction and training about Photovoice. Through pictures, they illustrated their personal strengths and the protective factors that families must implement to foster mental health in adolescents. The meaning of the photos taken were discussed and selected by participants during the group discussion.

2.9. Interview Guide

The team of researchers designed a guide to implement the focus group in the field, detailing the roles of the moderators and observers. The questions that guided the discussion followed the fundamentals of the ecological systems theory of Bronfenbrenner [

16]. The initial question was, what would be your opinions in relation to the family strengths that offer protection to adolescents? Additionally, we took and analyzed photographs that represent the most relevant protective factors from the participants’ perspective. Discussions in each focus group lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, with an additional 15 minutes on average during the photo shoot process.

Regarding demographic characteristics of parents, the age of participants ranged from 26 to 47 years old, with more than half of them being female. In terms of occupation, most men reported being farmers, while most women were homemakers.

2.10. Data Analysis

The verbatims were recorded and stored in voice files using digital recording equipment and then transcribed with NVIVO software. The research team employed one (01) super code to guide the data analysis based on a theoretical framework and the qualitative content analysis [

19] (

Table 1).

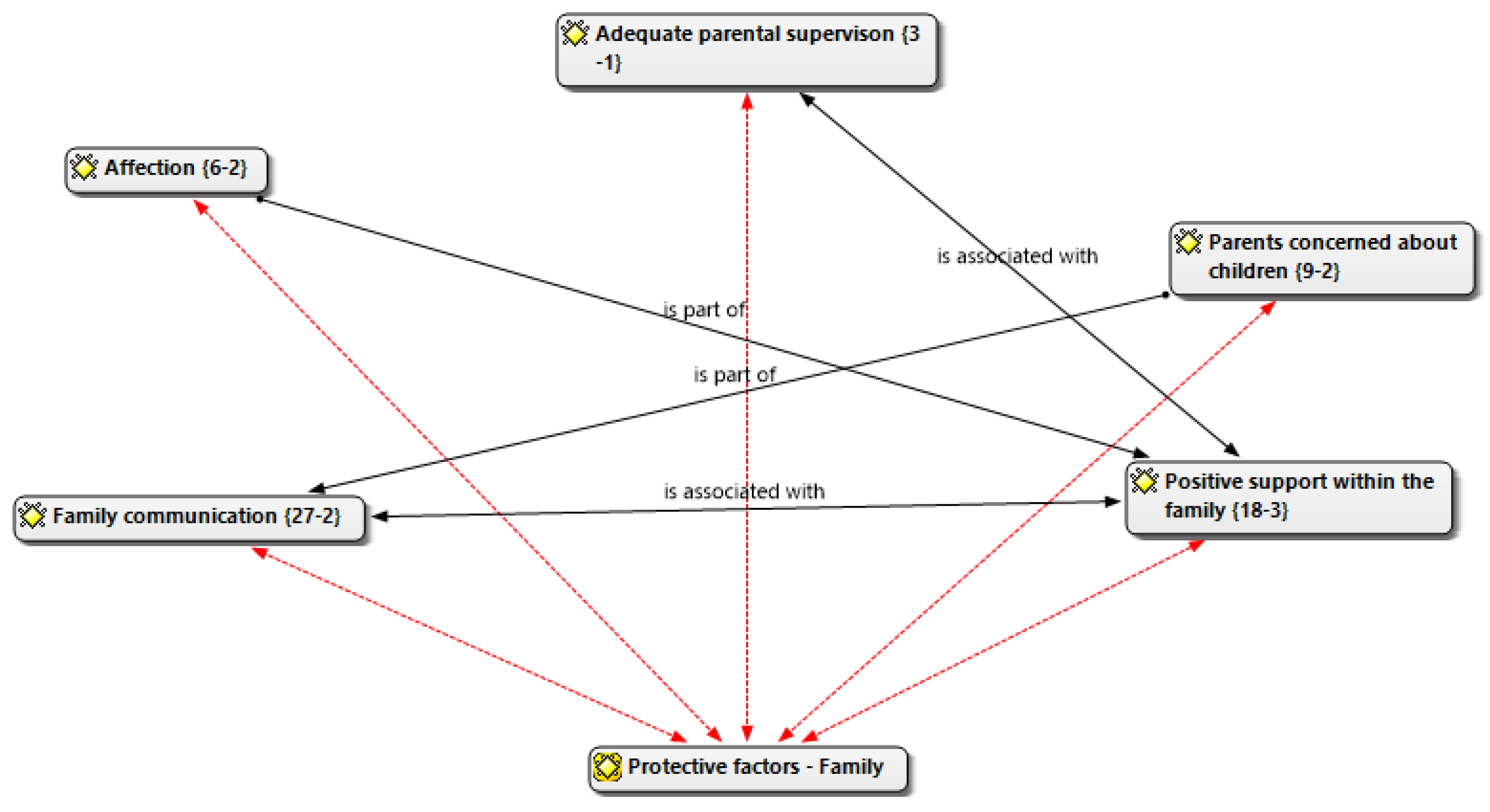

The inductive approach then took center stage in the analysis, from which the five subcategories indicated emerged in a structural network with their associations.

2.11. Rigor and Quality Guarantee

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, several strategies were implemented during data collection and analysis. First, moderators engaged in member checking throughout the focus groups by summarizing and paraphrasing participants’ responses to confirm accuracy and understanding. This approach helped validate interpretations in real time. Second, data triangulation was employed during analysis by comparing information from multiple focus groups and integrating the Photovoice images with the narrative data. This process enhanced the depth and credibility of the findings. Finally, the research team’s interdisciplinary composition strengthened the interpretive process by incorporating diverse professional perspectives and minimizing individual biases. These combined strategies addressed credibility and the overall rigor of the study.

2.12. Ethical and Legal Aspects of the Study

The study protocol followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The present research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador under Protocol No. EO-89-2022.

3. Results

We obtained an absolute count of one (01) deductive category assignment and seven (07) inductive subcategories from 5 documents from focus groups. We presented these results based on the most common themes in participants’ responses (grounded) and the connections to other subcategories (theoretical density).

3.1. Family Strengths as a Protective Factor

This study used focus group discussions and Photovoice to catalyze rural parents’ reflections on family strengths that protect adolescents’ mental health. Participants identified their experiences to understand that the family functions play an important role in promoting mental health. The strategy facilitated the understanding of the protective factors and their application in daily family life. The group of subcategories was represented with a pattern of relationships derived from the responses provided during the discussions in the focus groups. The most frequently mentioned behaviors during the discussion were communication and positive support. This allowed us to know the practice of protection and socialization as a family function (

Figure 1).

3.2. Positive Support Within the Family

In this subcategory, parents express their opinions and understanding of positive support for the physical, emotional, and social development of their children during adolescence. In the first case, some of the expressions in the subcategory ‘affection’ are associated with positive support, and this is part of the emotional function of the family. Love and acceptance dominate the expressions in this subcategory. Although this affective expression is not common in the discourse of other participants and focus groups, the discussion creates an opportunity to educate and expand knowledge about the importance of this function through social interaction.

“I think it would be having a little patience and affection. We must be tolerant and teach them. As one is older it is like giving to the youngest, giving him more affection.” (SP6-FG4).

“To be loved, to be listened to, to be helped or not to get too angry.” (SP2-FG2).

The following expressions indicate that the value of positive support emphasizes the protective function, which involves meeting basic needs through economic support, alongside the socializing function, which is characterized by recommendations and guidelines that promote healthy interpersonal relationships within the family unit and encourage discipline.

“Adolescents will be happier if there is understanding at home and helping them with whatever they need.” (SP5-FG1).

“It is the part that we must give to our children to talk, advise and help.” (SP1-FG4).

“If we support them through thick and thin, with advice or money, they will move forward, which is why it is good to support them. And if they are not supported, then they will go back in their goal of studying. And studying is the main thing, because now without studying they are nothing.” (SP4-FG4).

3.3. Adequate Parental Supervision

The subcategory ‘adequate parental supervision’ showed, from the everyday experience of parents, the consensual search for a way to maintain discipline to achieve family expectations. This subcategory also refers to the role of socialization in the family, which is why it is linked in the structural network to the subcategory ‘positive support’ within the family. The first testimony in the focus group sparked a discussion about the crucial role of the family-school in ensuring adequate supervision.

“They didn’t want anything (teenagers), they didn’t want to do their schoolwork, that’s why they lost the year [did not advance to the next school grade]. So, when I recovered, I went to talk to his teachers to find out what was happening. All my children attended the same school, so the teachers already knew me, but when these two missed the year [failed the grade], I explained my health situation, everything I went through, and they told me that we should try to have more communication. They didn’t know them.” (S6-FG4).

In another focus group, “adequate parental supervision” emphasizes the necessity for adequate care focused on development. “Knowing what adolescents do” fosters an interdependence in family functioning that leads to adolescent independence in adulthood.

“Encourage them to study, know what they are doing, so they don’t get married so quickly.” (SP3-FG5)

Both perspectives indicated in the focus groups promote socialization function, a protective factor to support the adaptation process of adolescents to family life and the social identity of which adolescents are a part.

3.4. Family Communication

The subcategory ‘Family communication’ indicates from the experience of the parents the importance of this practice for healthy coexistence and unity between family members. One of the stories describes the potential that family routines and daily activities have in promoting family communication.

“Family dialogue is positive.” (SP1-FG1).

“Communication, talking to children.” (SP2-FG2).

“You always must talk with them. It is necessary communication between parents and adolescents”. (SP-FG3).

“I always have the idea in my home that at the table we eat, in the morning or at night, I talk to my children about their things.” (SP5-FG4).

“Now I think about the home, the family, it is always the dialogue for the children and the dialogue for the home, because if you go the hard way, you will not achieve anything like that in a short time.” (SP2-FG4).

The subcategory ‘Parents concerned about children’ is part of the category ‘family communication’. According to the participants’ experiences, concerns refer to the difficulties or perceived needs of parents during their interactions with their adolescents, as well as the coping strategies they employ to overcome the challenges of daily life. This subcategory falls under the broader category ‘family communication’. The reason of this association is that parents primarily used dialog as a strategy to foster a closer bond with their children.

“Sometimes families suffer from things that happen to teenagers.” (SP5-FG3).

“When there is trust, the child can tell his father or mother. I think that there one could realize what is happening with them to give them advice.” (SP1-FG5).

“When I see them I always ask them what’s happening? In health problems more than anything or I insist that they tell us the other things that happen to them. Then they say yes, mom, I’m missing something. So, I say don’t worry, we’ll figure it out.” (SP6-FG4).

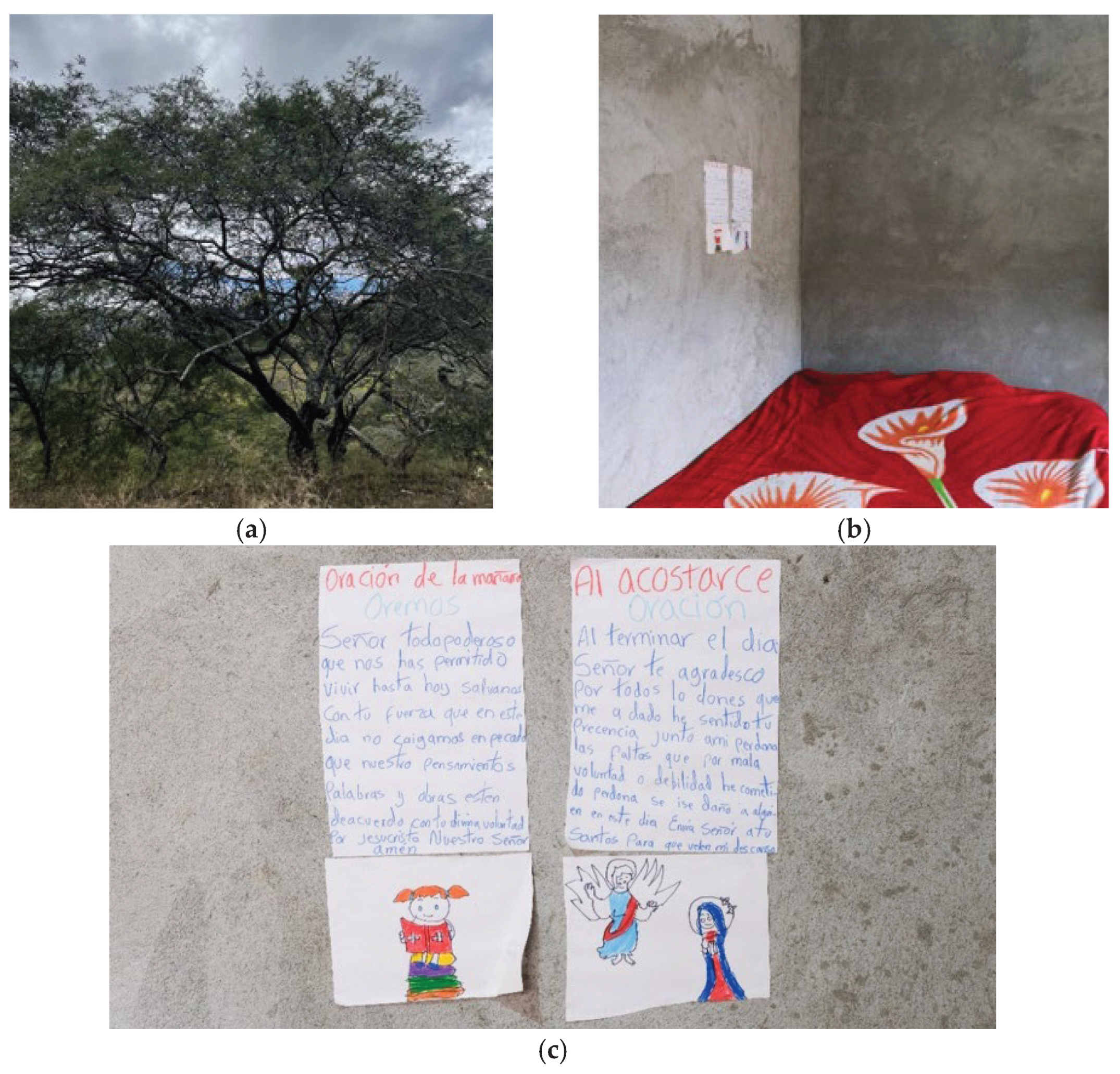

3.5. Photovoice Component

After focus group, participants worked to take photographs and reflect on the meaning of the images. The research team and participants discussed the most significate family factors that provide protection to the mental health of adolescents. From parents’ view the picture (a) ‘A tree’ represented adolescents of the community, also the path of life. At times, decisions may be made based on what is right or wrong. The most important thing is care, support, and familiar cohesion. Pictures (b) & (c) represented ‘Spirituality’ showing a place at home used to pray, each morning and evening children ask for protection, thanks, and forgiveness. This serves as an added source of motivation to persevere through each day.

Our interpretation about both subcategories is that tree and spirituality represented family strengths to promote mental health in adolescents. They are powerful resilient elements for parents of adolescents in rural areas. This step in the research demonstrated that the family’s primary goal during their interactions with the adolescents was emotionality and socialization. From parents a tree represented care, connection, and sharing activities that keep the family integrated. On the other hand, spirituality is founded in religious practices and its influence on the skill to cope with the challenges of dairy life. Bulleted lists look like this:

Figure 2.

(a) A tree; (b) and (c) spirituality. Source: Discussions in Focus Groups and pictures selected by participants.

Figure 2.

(a) A tree; (b) and (c) spirituality. Source: Discussions in Focus Groups and pictures selected by participants.

4. Discussion

This study explored family functioning as a protective factor for adolescent mental health from the perspective of parents in rural communities of southern Ecuador using Photovoice as a participatory research technique. The methodology allowed parents to engage in reflection on issues of family functioning and mental health that are rarely addressed in rural communities. Through photographs and focus groups, parents commented on aspects of family life that they perceived as necessary for supporting adolescents, such as effective communication, cohesion, supervision, and expressions of care. These findings accentuate the value of participatory implementation like Photovoice, which have been shown to promote collaboration, empowerment, and inclusion of life experiences in health research [

20,

21,

22].

The images of the environment and symbolic objects that were captured in the photographs led to a collaborative reflection between the research team and the parents of adolescents. The generation of narratives in the focus groups motivated the parents to think about ways of representing some aspects of family functioning and how this fact positively influences the mental health of their adolescent children. The meanings were related to caring. Previous studies claim that Photovoice provides an innovative platform for collaboration and advocacy [

23], promotes individual empowerment [

24], and emphasizes inclusivity while valuing knowledge derived from lived experiences [

25].

Specifically, we found that most parents effectively expressed the behaviors that are crucial for maintaining healthy family relationships or fulfilling protective, socializing, and nurturing functions to support psychological and emotional well-being during adolescence. In our study, some parents of adolescents reconstructed their own family routines that provided information about the ways in which families organize the interactivity of their lives and the care of adolescents. A quantitative study by Fosco and Lydon-Staley [

26] about the implication of family cohesion and conflict for adolescent mood and well-being indicated that everyday variations in family cohesion and conflict can significantly impact teenage well-being. Other authors have noted elevated mean scores in psychological well-being and emotional intelligence in terms of family functioning in the high-functioning group relative to the moderate functioning and severely dysfunctional groups, underscoring the significance of the family environment in adolescent development [

27].

Theoretically, it is understood that within the family, expressiveness relates to the affective function, encompassing both verbal and non-verbal emotional communication. [

28,

29]. This study revealed that affection was predominantly manifested through expressions of care, concern, protection, or appropriate parental monitoring. Parents indicated, albeit at a smaller degree, the expression of affection through verbal affirmations or embraces, implying that such activities are unusual among the rural households examined. According to the literature, parental warmth or affection represents a unique relational process that is essential for core developmental aspects, including parent-child attachment, socialization, emotion recognition, responsivity, and empathy development [

30]. Enhancing parental emotional warmth, perceived social support, and encouraging prosocial behavior among rural adolescents could effectively foster their sense of hope [

31].

The finding regarding spirituality emerged as a common practice among families in rural communities. During the discussions, parents expressed the importance of spiritual practices and represented it in the photovoice activity with two pictures. They recognized spirituality as a protective factor that supports the mental health of adolescents and helps to keep a good relationship within the family system. Some studies also state that positive parenting practices and effective parent-child communication are associated with higher spirituality [

32]. Moreover, cultural values moderate the impact of parenting styles on child outcomes, supporting spiritual development [

33].

The mental health promotion of adolescents is a challenge for health systems around the world due to the high burden of mental disorders. Therefore, the inclusion of this subject in the Sustainable Development Goals [

34,

35] through the wellness promotion and its definition as a priority for global development. A systematic analysis about the global number of disability-adjusted life-years DALYs was 125.3 millions of people affected [

36]. The low and middle-income countries are more affected because of the shortage of mental health professionals and available services in rural areas [

37]. Furthermore, parents in rural areas display several difficulties in matter of mental health promotion such as nonexistence of structured programs in mental health education that support families and prevent cognitive distortions, i.e., mental health topics could be perceived like a weakness or less important [

10].

Adolescence is a critical developmental period. Therefore, community and family nurses play an important role in the promotion of healthy relationships in families of rural communities. Especially, the gap addressed with the implementation of focus group discussion and photovoice methodology was the lack of health education about this topic. Using Photovoice, the research team leverages the family experiences shared by participants through pictures, discussions and reflections, to elicit reflections with participants notions about protective factors of mental health and family functioning. This approach showed cultural sensitivity and acceptability by the participants. The principal educative message was that good family functioning is related to good mental health. Our research findings indicate that the importance of achieving positive relationships within families is that cohesion and affection significantly contribute to adolescents’ sense of control over their health and reduce the likelihood of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety [

38]. Family cohesion, including daily interactions and family-centered activities, directly correlates with fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms [

39].

This study presents the limitations inherent to qualitative research designs, i.e., convenience sampling, sample size, and findings that respond to the particularity of the subjects under study, and therefore it is not possible to generalize the results. However, in contrasting our results with other research, similarities were observed with other reports obtained in other contexts, even when different methodologies and instruments were used. Despite gathering extensive information about good family functioning, we cannot be certain that this is the predominant behavior in the families analyzed. We can ensure that the implementation of these participatory action research methodologies influences the development of collective knowledge and the processes of family health and mental health education.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the important role of family strengths in protecting adolescent mental health in rural communities of southern Ecuador. Through participatory approaches such as Photovoice, families provided profound insights, emphasizing that effective communication, emotional support, parental supervision, and family cohesion serve as key pillars of resilience. Importantly, these qualities are not abstract concepts but dynamic, lived realities that help families navigate the complex challenges of economic hardship and geographic isolation. Nevertheless, these protective factors have their limitations, underscoring the vulnerability of support networks in resource-constrained settings.

The implementation of Photovoice converted participants from research subjects to collaborators, allowing them to critically reflect on their behaviors while aiding or reinforcing in the co-creation of strategies. This dual impact revealed protective factors and enabled families to regain control over their narratives and mental health outcomes. Moreover, the cultural and spiritual aspects highlighted in this study—especially the influence of faith and common values—demonstrated the significant interaction between belief systems and resilience. These findings necessitate meticulous attention in the formulation of therapies and the implementation of training programs aimed at improving the mental health of adolescents living in rural areas of low- and middle-income countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.-M; E.B.-C; M.J.C.-T.; methodology, V.M.-M.; data curation, M.F.; formal analysis, V.M.-M; M.J.C.-T; M.F; E.B.-C.; resources, M.J.C.-T ; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.-M; E.B.-C; writing—review and editing, M.J.C.-T; M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Infectious and Tropical Disease Institute Ohio University (QAUF1125) and Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (QINV0359).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Protocol No. EO-89-2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available [transcription] because of ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the parents of adolescents and young people from rural communities for their dedication to understanding their children’s development. Our gratitude also extends to Dr. Mario Grijalva, Director of the Infectious and Tropical Disease Institute at the University of Ohio, for his over 20 years of work combating Chagas disease in rural Ecuadorian communities and support the addressing of other health challenges. Additionally, we acknowledge Darwin Guerrero for his invaluable assistance in coordinating the focus group discussions and supporting data collection. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used SCOPUS ai, SCISPACE, and DeepL for the purposes of to improve grammar, style, and coherence for academic readers. These technologies also helped identify relevant authors and references to expedite the literature review. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1553-98. Epub 20181009. PubMed PMID: 30314863. [CrossRef]

- Marchi M, Alkema A, Xia C, Thio CHL, Chen L-Y, Schalkwijk W, et al. The impact of poverty on mental illness: Emerging evidence of a causal relationship. medRxiv. 2023:2023.05.19.23290215. [CrossRef]

- Michael A, O’Neal L, Kersey E, Nielsen A, Coker K, Forthun L. A Community-Based Approach to Supporting the Mental Health of Rural Youth. EDIS. 2022;2022(6). [CrossRef]

- McGarry J. The essence of ‘community’ within community nursing: a district nursing perspective. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2003;11(5):423-30. [CrossRef]

- Morris AS, Jespersen JE, Cosgrove KT, Ratliff EL, Kerr KL. Parent Education: What We Know and Moving Forward for Greatest Impact. Family Relations. 2020;69(3):520-42. [CrossRef]

- Wille N, Bettge S, Ravens-Sieberer U. Risk and protective factors for children’s and adolescents’ mental health: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17 Suppl 1:133-47. PubMed PMID: 19132313. [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk O, Schwarze M, Rumpf H-J, Metzner F, Pawils S. Protective mental health factors in children of parents with alcohol and drug use disorders: A systematic review. PloS one. 2017;12(6):e0179140. [CrossRef]

- Probst J, Eberth JM, Crouch E. Structural Urbanism Contributes To Poorer Health Outcomes For Rural America. Health Affairs. 2019;38(12):1976-84. PubMed PMID: 31794301. [CrossRef]

- Wilson RL, Usher K. Rural nurses: a convenient co-location strategy for the rural mental health care of young people. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2015;24(17-18):2638-48. [CrossRef]

- Baus E, Carrasco-Tenezaca M, Frey M, Medina-Maldonado V. Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20(3):2205. PubMed PMID:. [CrossRef]

- Mooney R, Bhui K. Analysing multimodal data that have been collected using photovoice as a research method. BMJ Open. 2023;13(4):e068289. [CrossRef]

- Stephens M, Keiller E, Conneely M, Heritage P, Steffen M, Bird VJ. A systematic scoping review of Photovoice within mental health research involving adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2023;28(1). [CrossRef]

- Ten Doesschate T, PERALTA AQ, LOJANO HC, Fajardo V, Flores N, Guachún M, et al. Psychological and behavioral problems among left-behind adolescents. The case of Ecuador. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Médicas. 2012;3:16-29.

- Ferdinand AO, Madkins J, McMaughan D, Schulze A. Mental health and mental disorders: A rural challenge. Bolin JN, Bellamy G, Ferdinand AO, eds. 2015;1:55-75.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Harvard University Press; 1979.

- Eriksson M, Ghazinour M, Hammarström A. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: what is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Social Theory & Health. 2018;16(4):414-33. [CrossRef]

- Leahey M, Wright LM. Application of the Calgary Family Assessment and Intervention Models: Reflections on the Reciprocity Between the Personal and the Professional. J Fam Nurs. 2016;22(4):450-9. Epub 20160912. PubMed PMID: 27619397. [CrossRef]

- Mayring P. Qualitative Content Analysis : A Step-by-Step Guide. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2021. Available from: http://digital.casalini.it/9781529766738.

- Reupert A, Hine R, Maybery D. Working with rural families: Issues and responses when a family member has a mental illness. Handbook of rural, remote, and very remote mental health. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021. p. 623-40.

- Han J, Hao Y, Cui N, Wang Z, Lyu P, Yue L. Parenting and parenting resources among Chinese parents with children under three years of age: rural and urban differences. BMC Primary Care. 2023;24(1):38. [CrossRef]

- Modderman C, Downey H. Special issue: Health and well-being services for children and young people (ages 0–24) in rural and remote communities. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2023;31(6):1041-3. [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan N, Douglas P, Keaver L. Meaning of nutrition for cancer survivors: a photovoice study. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. 2024;7(1):112-8. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Gordillo MJ, Bates BR, Vivat B. The (im)possibility of being a breastfeeding working mother: experiences of Ecuadorian healthcare providers. Frontiers in Communication. 2023;8. [CrossRef]

- Rana R, Kozak N, Black A. Photovoice Exploration of Frontline Nurses’ Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can J Nurs Res. 2023;55(1):25-33. Epub 20211222. PubMed PMID: 34935505; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9936175. [CrossRef]

- Fosco GM, Lydon-Staley DM. Implications of family cohesion and conflict for adolescent mood and well-being: Examining within-and between-family processes on a daily timescale. Family process. 2020;59(4):1672-89. [CrossRef]

- Molina Moreno P, Fernández Gea S, Molero Jurado MDM, Pérez-Fuentes MDC, Gázquez Linares JJ. The Role of Family Functionality and Its Relationship with Psychological Well-Being and Emotional Intelligence in High School Students. Education Sciences. 2024;14(6):566. [CrossRef]

- Mileski M, McClay R, Heinemann K, Dray G. Efficacy of the Use of the Calgary Family Intervention Model in Bedside Nursing Education: A Systematic Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:1323-47. Epub 20220616. PubMed PMID: 35734541; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9208629. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Maldonado V. Enfermería familiar, enfoques, teoría y modelos para la atención. In: Francisco Pérez J, editor. Cuidado de Enfermería en el Núcleo Familiar: Reflexiones Teóricas y Aplicación de Casos. 1. 1ra ed. Quito, Ecuador: EdiPUCE; 2024. p. 16-24.

- Prasad AH, Keevers Y, Kaouar S, Kimonis ER. Conception and Development of the Warmth/Affection Coding System (WACS): A Novel Hybrid Behavioral Observational Tool for Assessing Parent-to-Child Warmth. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2023;51(9):1357-69. Epub 20230420. PubMed PMID: 37079146; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10474998. [CrossRef]

- Lu C. The Relationship between Parental Emotional Warmth and Rural Adolescents’ Hope: The Sequential Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Prosocial Behavior. J Genet Psychol. 2023;184(4):260-73. Epub 20221229. PubMed PMID: 36579421. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman CC, Howell KH, Mandell JE, Hasselle AH, Thurston IB. Spirituality and Parenting among Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2021;36(2):183-93. [CrossRef]

- Haslam D, Poniman C, Filus A, Sumargi A, Boediman L. Parenting Style, Child Emotion Regulation and Behavioral Problems: The Moderating Role of Cultural Values in Australia and Indonesia. Marriage & Family Review. 2020;56(4):320-42. [CrossRef]

- Votruba N, Thornicroft G. Sustainable development goals and mental health: learnings from the contribution of the FundaMentalSDG global initiative. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2016;3:e26. Epub 20160909. PubMed PMID: 28596894; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5454784. [CrossRef]

- Iemmi V. Sustainable development for global mental health: a typology and systematic evidence mapping of external actors in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(6):e001826. Epub 20191203. PubMed PMID: 31908860; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6936513. [CrossRef]

- GBD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137-50. Epub 20220110. PubMed PMID: 35026139; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8776563. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Ouyang F, Nergui OE, Bangura JB, Acheampong K, Massey IY, et al. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Policy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Challenges and Lessons for Policy Development and Implementation. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:150. Epub 20200318. PubMed PMID: 32256399; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7094177. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Z, Holtmaat K, Verdonck-De Leeuw IM, Koole SL. Chinese college students’ mental health during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic: the protective role of family functioning. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024;12. [CrossRef]

- Palimaru AI, Dong L, Brown RA, D’Amico EJ, Dickerson DL, Johnson CL, et al. Mental health, family functioning, and sleep in cultural context among American Indian/Alaska Native urban youth: A mixed methods analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114582. Epub 20211118. PubMed PMID: 34826766; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8748395. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).