Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Subauroral Plasma Flows

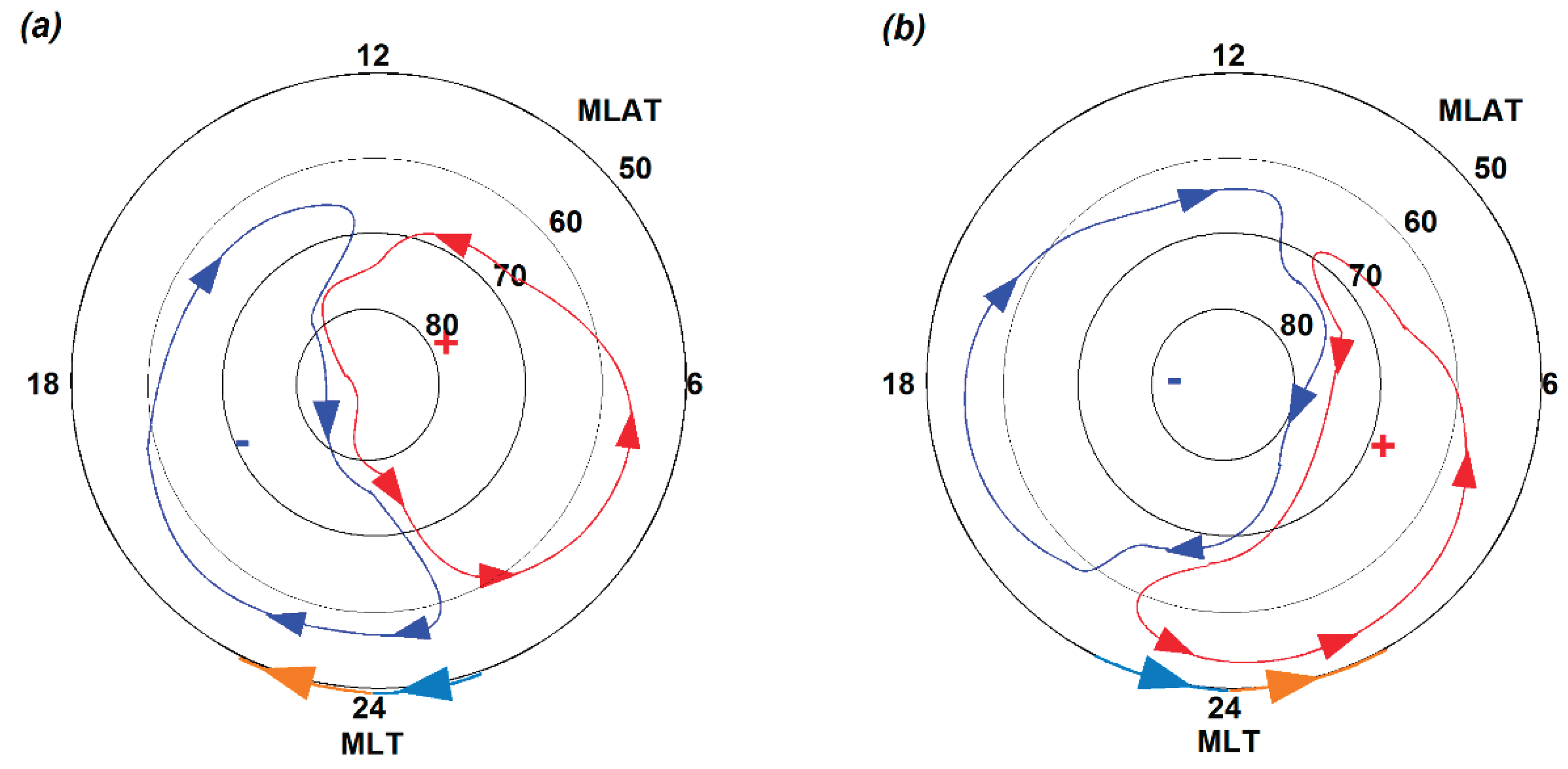

1.2. Plasma Convection in the Coupled M-I System

1.3. Pulsed Convection Flows

1.4. EDawn-Dusk Driving the Ionosphere Plasma at Subauroral and Mid Latitudes

1.5. Motivation and Aim of this Study

2. Materials and Methods

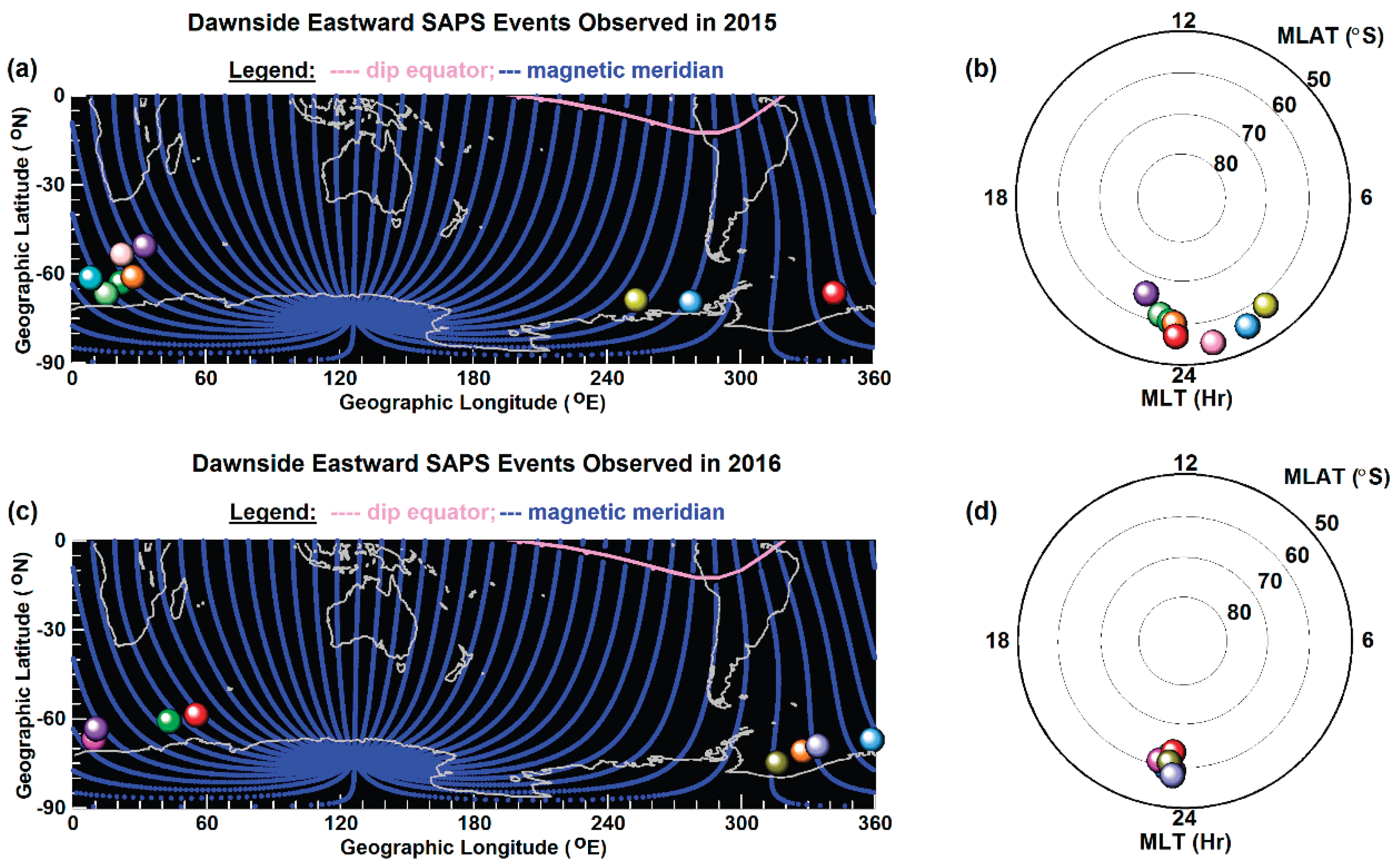

3. Results

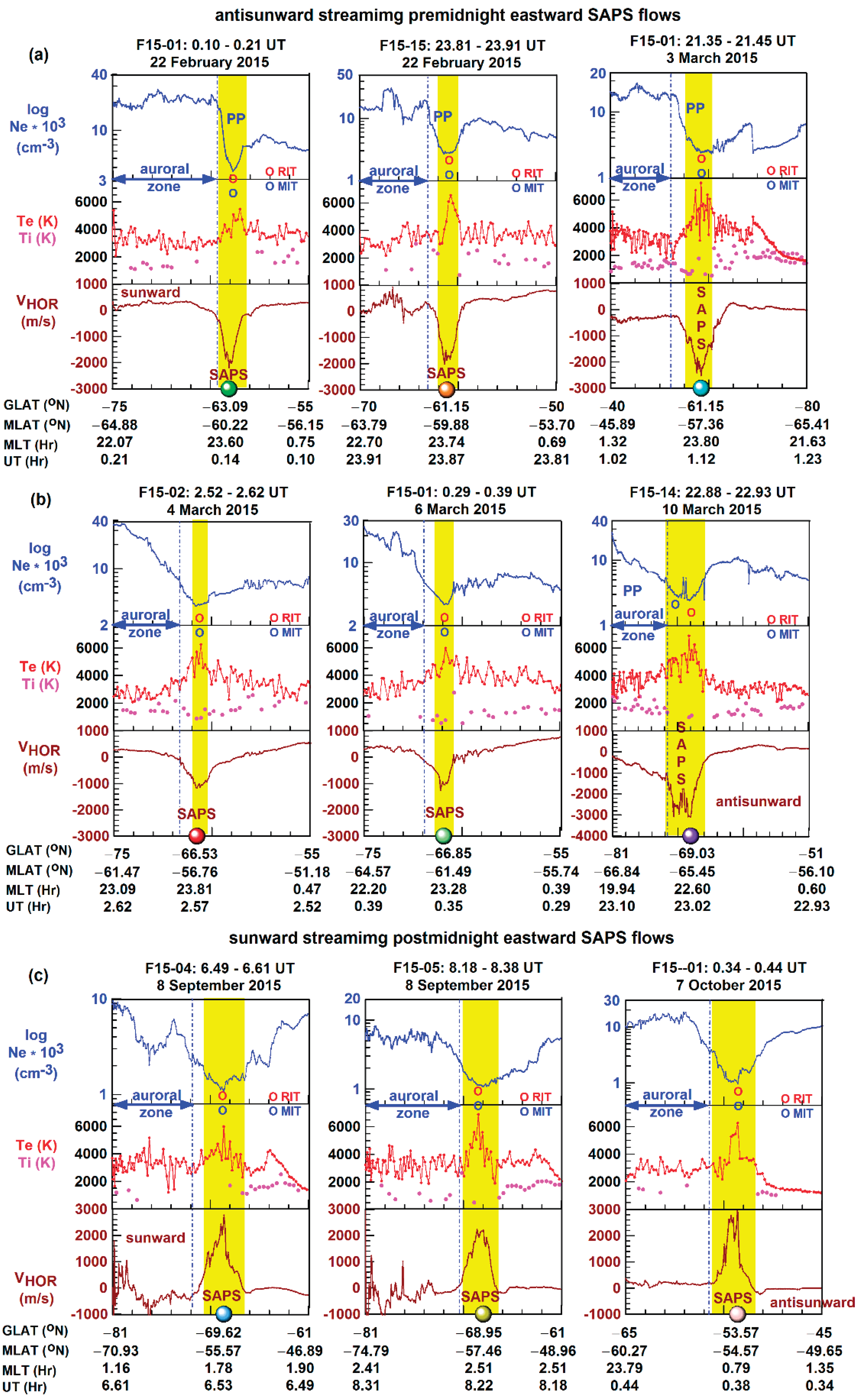

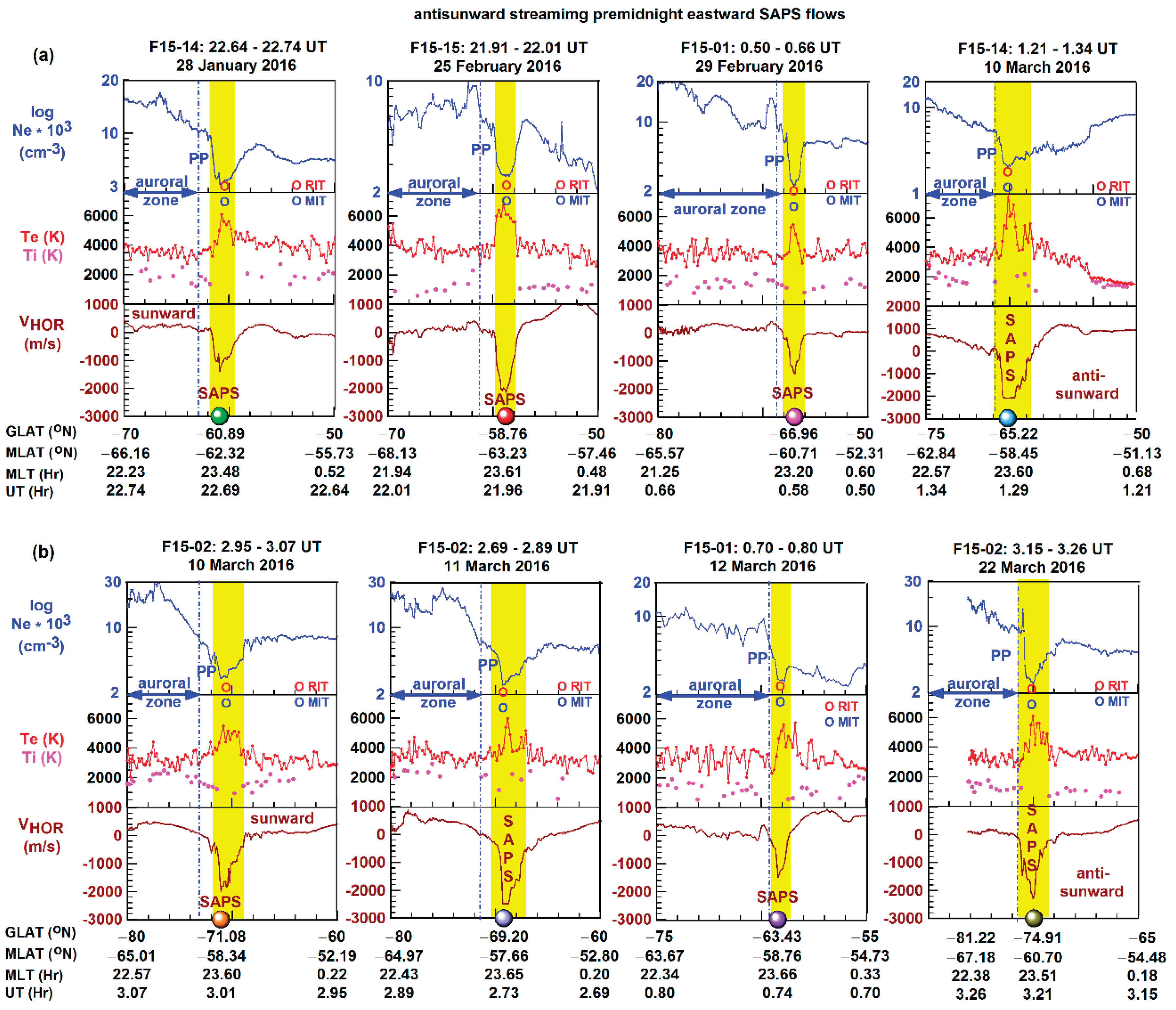

3.1. Dawn-Cell-Related Eastward SAPS Observed by DMSP F15 Near Magnetic Midnight

3.2. Underlying Interplanetary and Geophysical Conditions

3.3. Sunward Streaming Eastward SAPS Flow: 7 October 2015 Event

3.4. Antisunward Streaming Eastward SAPS flow: 3 March 2015 Event

3.5. Correlated DMSP F15- TH-E 8 September 2015 Event

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B field | Magnetic field |

| CG | Current Generator |

| DMSP | Defense Meteorological Satellite Program |

| E field | Electric field |

| EC | Convection Electric field |

| EDawn-Dusk | Dawn-to-Dusk E field |

| EDusk-Dawn | Dusk-to-Dawn E field |

| EPIC | Energetic Particle & Ion Composition |

| EPS | Energetic Particle Sensor |

| EFI | Electric Field Instrument |

| ESA | Electrostatic Analyzer |

| FACs | Field-Aligned Currents |

| GLAT | Geographic Latitude |

| GLON | Geographic Longitude |

| GMOM | Ground-calculated Moments |

| GOES | Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites |

| GSE | Geocentric Solar Ecliptic |

| GSM | Geocentric Solar Magnetospheric |

| H-M | Heppner-Maynard |

| L | L shell |

| M-I | Magnetosphere-Ionosphere |

| MIT | Main Ionospheric Trough |

| MLAT | Magnetic Latitude |

| MLT | Magnetic Local Time |

| Ne | electron density |

| Pe | electron pressure |

| Pi | ion pressure |

| PJ | Polarization Jet |

| PP | Plasmapause |

| RIT | Ring-current-related Ionospheric Trough |

| R1 | Region 1 |

| R2 | Region 2 |

| SAID | Sub-Auroral Ion Drifts |

| SAPS | Sub-Auroral Polarization Streams |

| SC Pot | Spacecraft Potential |

| SCW | Substorm Current Wedge |

| SCW2L | Substorm Current Wedge 2-Loop |

| SSUSI | Special Sensor Ultraviolet Spectrographic Imager |

| SuperDARN | Super Dual Auroral Radar Network |

| Te | electron temperature |

| THEMIS | Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms |

| TB | Trapping Boundary |

| Ti | ion temperature |

| Ve | electron drift |

| VG | Voltage Generator |

| VGFT | Fast-Time Voltage Generator |

| VGM | Magntospheric Voltage Generator |

| VHOR | cross-track horizontal drift velocity |

| VVER | cross-track vertical drift velocity |

| WTS | Westward Traveling Surge |

References

- Foster, J.; Burke, W. A new categorization for sub-auroral electric fields. Eos. Transactions of the American Geophysical Union 2002, 83, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, R.W.; Heelis, R.A.; Hanson, W.B. Rapid subauroral drifts observed by Atmosphere Explorer C. Geophysical Research Letter 1979, 6, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, Yu. L.; Ponomarev, V. N.; Zosimova, A.G. Plasma convection in the polar ionosphere. Annales de Geophysique 1974, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Smiddy, M.; Kelley, M.C.; Burke, W.; Rich, F.; Sagalyn, R.; Shuman, B.; Hays, R.; Lai, S. Intense poleward-directed electric fields near the ionospheric projection of the plasmapause. Geophysical Research Letters 1977, 4, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, N.; Aggson, T.; Heppner, J. Magnetospheric observation of large subauroral electric fields. Geophysical Research Letters 1980, 7, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.; Marklund, G.T.; Blomberg, L.G.; Mälkki, A. Subauroral electric fields observed by the Freja satellite: A statistical study. Journal of Geophysical Research 1998, 103(A3), 4327–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.C.; Vo, H.B. Average characteristics and activity dependence of the subauroral polarization stream. Journal of Geophysical Research 2002, 107, SIA 16-1–SIA 16-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.C.; Heelis, R.A.; Hanson, W.B. The ionospheric signatures of rapid subauroral ion drifts. Journal of Geophysical Research 1991, 96, 5,785–5,792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.C.; Hanson, W.B.; Heelis, R.A.; Craven, J.D.; Baker, D.N.; Frank, L.A. A proposed production model of rapid subauroral ion drifts and their relationship to substorm evolution. Journal of Geophysical Research 1993, 98, 6,069–6,078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Lovell, B.C. Investigating the Coupled Magnetosphere-Ionosphere-Thermosphere (M-I-T) System’s Responses to the 20 November 2003 Superstorm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2021, 126, e2021JA029215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Lovell, B.C. Multi-point satellites observed dawnside Subauroral Polarization Streams (SAPS) developed on a short timescale under weak-storm and non-storm substorm conditions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2025, 130, e2025JA033755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwood, D.; Wolf, R. An assessment of the role of precipitation in magnetospheric convection. Journal of Geophysical Research 1978, 83, 5,227–5,232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.V. The evolving paradigm of the subauroral geospace. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 2023, 10, 1118758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.V. SAPS onset timing during substorms and the westward traveling surge. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 6,687–6,693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.; Nishimura, Y.; Foster, J. SAPS/SAID revisited: A causal relation to the substorm current wedge. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2017, 122, 8,516–8,535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.V. Interaction of substorm injections with the subauroral geospace: 1. Multispacecraft observations of SAID. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2013, 118, 5,782–5,796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, V.A.; Nikolaev, A.V.; Tsyganenko, N.A.; Angelopoulos, V.; Runov, A.V.; Singer, H.J.; Yang, J. Testing a two-loop pattern of the substorm current wedge (SCW2L). Journal of Geophysical Research 2014, 119, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, S.; Gjerloev, J.W.; Anderson, B.J.; Kataoka, R.; Troshichev, O.; Watari, S. Dawnside wedge current system formed during intense geomagnetic storms. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2018, 123, 9093–9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, S.; Sorathia, K.; Merkin, V.G.; Frey, H.U.; Gjerloev, J.W. External and internal causes of the stormtime intensification of the dawnside westward auroral electrojet. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2023, 128, e2023JA031457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasofu, S.I. The dynamical morphology of the aurora polaris. Journal of Geophysical Research 1963, 68, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasofu, S.-I. The development of the auroral substorm. Planetary and Space Science 1964, 12, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungey, J.W. Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones. Physical Review Letters 1961, 6, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.S. The driving force for magnetospheric convection. Reviews of Geophysics 1978, 16, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brice, N.M. Bulk motion of the magnetosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research 1967, 72, 5193–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A. Formation of plasmapause, or magnetospheric plasma knee, by the combined action of magnetospheric convection and plasma escape from the tail. Journal of Geophysical Research 1966, 71, 5669–5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamide, Y.; Richmond, A. D.; Matsushita, S. Estimation of ionospheric electric fields, ionospheric currents, and field-aligned currents from ground magnetic records. Journal of Geophysical Research 1981, 86, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Christensen, E.; Kamide, Y; Richmond, A.D.; Matsushita, S. Interplanetary magnetic field control of high-latitude electric fields and currents determined from Greenland magnetometer data. Journal of Geophysical Research 1985, 90, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.C. Storm time plasma transport at middle and high latitudes. Journal of Geophysical Research 1993, 98(A2), 1675–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svalgaard, L. Sector structure of the interplanetary magnetic field and daily variation of the geomagnetic field at high latitudes. Det Danske Meteorologiskeinstitutt, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mansurov, S.M. New evidence of a relationship between magnetic fields in space and on earth. Geomagnetism Aeronomy 1970, 9, 622–623. [Google Scholar]

- Haaland, S.E.; Paschmann, G.; Förster, M.; Quinn, J.M.; Torbert, R.B.; McIlwain, C.E.; Vaith, H.; Puhl-Quinn, P.A.; Kletzing, C. A. High-latitude plasma convection from Cluster EDI measurements: method and IMF-dependence. Annales Geophysicae 2007, 25, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.P.; Haaland, S.; Forsyth, C.; Keesee, A.M.; Kissinger, J.; Li, K.; Runov, A.; Soucek, J.; Walsh, B.M.; Wing, S.; Taylor, M. G.G.T. Dawn–dusk asymmetries in the coupled solar wind–magnetosphere–ionosphere system: a review. Annales Geophysicae 2014, 32, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, R.A. Baker, K.B. Dudeney, J.R.; Pinnock, M.; Jones, T.B.; Thomas, E.C., Villain, J.-P.; Cerisier, J.-C.; Senior, C.; Hanuise, C.; Hunsucker, R.D.; Sofko, G.; Koehler, J.; Nielsen, E.; Pellinen, R.; Walker, A.D.M.; Sato, N.; Yamagishi, H. DARN/SuperDARN. Space Science Reviews 1995, 71, 761–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisham, G.; Lester, M.; Milan, S.E.; Freeman, M.P.; Bristow, W.A.; Grocott, A.; McWilliams, K.A.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Yeoman, T.K.; Dyson, P.L.; Greenwald, R.A.; Kikuchi, T.; Pinnock, M.; Rash, J.P.S; Sato, N.; Sofko, G.J.; Villain, J.-P.; Walker, A.D.M. A decade of the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN): Scientific achievements, new techniques and future directions. Surveys in Geophysics 2007, 28, 33–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocott, A. Time-dependence of dawn-dusk asymmetries in the terrestrial ionospheric convection pattern. In Dawn-dusk asymmetries in planetary plasma environments; Haaland, S. E., Runov, A., Forsyth, C., Eds.; American Geophysical Union Monograph: Hoboken, NJ, 2017; Volume 228, pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.C.; Foster, J.C.; Rich, F.J.; Swider, W. Storm time electric field penetration observed at mid-latitude. Journal of Geophysical Research 1991, 96(A4), 5707–5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandholt, P.E.; Farrugia, C.J. Plasma flow channels at the dawn/dusk polar cap boundaries: momentum transfer on old open field lines and the roles of IMF By and conductivity gradients. Annales Geophysicae 2009, 27, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelis, R.A.; Lowell, J.K.; Spiro, R.W. A model of the high-latitude ionospheric convection pattern. Journal of Geophysical Research 1982, 87(A8), 6339–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.C.; Holt, J.M.; Musgrove, R.; Evans, D. Ionospheric convection associated with discrete levels of particle precipitation. Geophysical Research Letters 1986, 13, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, J.P.; Maynard, N.C. Empirical high-latitude electric-field models. Journal of Geophysical Research 1987, 92(A5), 4467–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-S.; Foster, J.C.; Holt, J.M. Westward plasma drift in the midlatitude ionospheric F region in the midnight-dawn sector. Journal of Geophysical Research 2001, 106, 30,349–30,362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, Y.; Fok, M.; Sazykin, S.; Thomsen, M.F.; Hairston, M.R.; Evans, D.S.; Rich, F.J.; Ejiri, M. Ring current and the magnetosphere-ionosphere coupling during the superstorm of 20 November 2003. Journal of Geophysical Research 2005, 110(A9), A09S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, R.; Nishitani, N.; Ebihara, Y.; Hosokawa, K.; Ogawa, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Miyoshi, Y. Dynamic variations of a convection flow reversal in the subauroral postmidnight sector as seen by the SuperDARN Hokkaido HF radar. Geophysical Research Letters 2007, 34, L21105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarevich, R.A.; Kellerman, A.C.; Bogdanova, Y.V.; Koustov, A.V. Time evolution of the subauroral electric fields: A case study during a sequence of two substorms. Journal of Geophysical Research 2009, 114(A4), A04312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, M.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Baker, J.B.; Ribeiro, A.J. Statistical study of nightside quiet time midlatitude ionospheric convection. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2018, 123, 2228–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, M.; Baker, J.B.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Kunduri, B. Morphology of nightside subauroral ionospheric convection: Monthly, seasonal, KP, and IMF dependencies. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2019, 124, 4608–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunduri, B. S.; Baker, J.B.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Nishitani, N.; Oksavik, K.; Erickson, P.J.; Coster, A.J.; Shepherd, S.G.; Bristow, W. A.; Miller, E.S. A new empirical model of the subauroral polarization stream. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2018, 123, 7342–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyatsky, W.; Tan, A.; Khazanov, G.V. A simple analytical model for subauroral polarization stream (SAPS). Geophysical Research Letters 2006, 33, L19101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. C.; Carpenter, D.L.; Tsuruda, K.; Mukai, T.; Rich, F.J. Multisatellite observations of rapid subauroral ion drifts (SAID). Journal of Geophysical Research 2001, 106(A12), 29585–29600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Lovell, B.C. Amplified Westward SAPS Flows near Magnetic Midnight in the Vicinity of the Harang Region. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, H.E.J.; Pulkkinen, T.I. Midnight velocity shear zone and the concept of Harang discontinuity. Journal of Geophysical Research 1995, 100, 9,53–9,547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Lin, D.; Wu, Q. Low-latitude zonal ion drifts and their relationship with subauroral polarization streams and auroral return flows during intense magnetic storms. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2021, 126, e2021JA030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Wang, W.; Merkin, V.G.; Huang, C.; Oppenheim, M.; Sorathia, K.; Pham, K.; Michael, A.; Bao, S.; Wu, Q. Origin of Dawnside Subauroral Polarization Streams During Major Geomagnetic Storms. AGU Advances 2022, 3, e2022AV000708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aa, E.; Zhang, S.-R.; Wang, W.; Erickson, P.J.; Coster, A.J. Multiple longitude sector storm-enhanced density (SED) and long-lasting subauroral polarization stream (SAPS) during the 26–28 February 2023 geomagnetic storm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2023, 128, e2023JA031815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Wang, H.A. Statistical Study of Ion Upflow during Periods of Dawnside Auroral Polarization Streams and Subauroral Polarization Streams. Remote Sensing 15, 1320. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Wang, W.; Fok, M.-C.; Pham, K.; Yue, J.; Wu, H. Subauroral red arcs generated by inner magnetospheric heat flux and by subauroral polarization streams. Geophysical Research Letters 2024, 51, e2024GL109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K. Impact of interplanetary magnetic field By on subauroral polarization streams at dawn and dusk. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 20242024, 129, e2024JA033063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, F.J.; Hairston, M. Large-scale convection patterns observed by DMSP. Journal of Geophysical Research 1994, 99, 3,827–3,844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruohoniemi, J. M.; Greenwald, R.A. Observations of IMF and seasonal effects in high-latitude convection. Geophysical Research Letters 1995, 22, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocott, A.; Walach, M.-T.; Milan, S. E. SuperDARN Observations of the Two Component Model of Ionospheric Convection. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2023, 128, e2022JA031101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, E.D.P.; Matsuo, T.; Richmond, A.D. SuperDARN assimilative mapping. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2013, 118, 7954–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.G.; Shepherd, S.G. Statistical patterns of ionospheric convection derived from mid-latitude, high-latitude, and polar SuperDARN HF radar observations. Journal of Geophysical Research 2018, 123, 3,196–3,216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, L.J.; Morrison, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kil, H.; Wolven, B.; Ogorzalek, B.S.; Humm, D.C.; Meng, C.-I. Validation of remote sensing products produced by the Special Sensor Ultraviolet Scanning Imager (SSUSI): a far UV-imaging spectrograph on DMSP F-16. Proceedings Optical Spectroscopic Techniques, Remote Sensing, and Instrumentation for Atmospheric and Space Research IV 2002, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, R.N. The SMS/GOES space environment monitor subsystem. NOAA technical memorandum ERL SEL Space Environment Laboratory, Boulder Colorado. 1975, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, A. The Geotail Mission. Geophysical Research Letters 1994, 21, 2871–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.J.; McEntire, R.W.; Schlemm II, C.; Lui, A.T.Y.; Gloeckler, G.; Christon, S.P.; Gliem, F. Geotail energetic particles and ion composition instrument. Journal of Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity 1994, 46, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibeck, D.G.; Angelopoulos, V. THEMIS science objectives and mission phases. Space Science Reviews 2008, 141, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.T.; Gjerloev, J.W. Evaluation of SuperMAG auroral electrojet indices as indicators of substorms and auroral power. Journal of Geophysical Research 2011, 116(A12), A12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, C.; Rae, I.J.; Coxon, J.C.; Freeman, M.P.; Jackman, C.M.; Gjerloev, J.; Fazakerley, A.N. A new technique for determining substorm onsets and phases from indices of the Electrojet (SOPHIE). Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2015, 120, 10,592–10,606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, S.; Gjerloev, J.W. Is the substorm current wedge an ensemble of wedgelets? Revisit to midlatitude positive bays. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2020, 125, e2020JA027902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, N.B.; Pathan, B.M.; Schuch, N.J.; Barreto, M.; Dutra, L.G. Geomagnetic phenomena in the South Atlantic anomaly region in Brazil. Advances in Space Research 2005, 36, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A. Mechanisms of the electron density depletion in the SAR arc region. Annales Geophysicae 1996, 14, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpachev, A.T.; Deminov, M.G.; Afonin, V.V. Model of the mid-latitude ionospheric trough on the base of Cosmos-900 and Intercosmos-19 satellites data. Advances in Space Research 1996, 18, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpachev, A.T. Dynamics of main and ring ionospheric troughs at the recovery phase of storms/substorms. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2021, 126, e2020JA028079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpachev, A.T. Statistical analysis of ring ionospheric trough characteristics. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2021, 126, e2021JA029613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpachev, Advanced Classification of Ionospheric Troughs in the Morning and Evening Conditions. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4072. [CrossRef]

- Muldrew, D.B. F layer ionization troughs deduced from Alouette data. Journal of Geophysical Research 1965, 70, 2,635–2,650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl-Quinn, P.A.; Matsui, H.; Mishin, E.; Mouikis, C.; Kistler, L.; Khotyaintsev, Y.; Décréau, P.M.E.; Lucek, E. Cluster and DMSP observations of SAID electric fields. Journal of Geophysical Research 2007, 112(A5), A05219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilig, B.; Stolle, C.; Kervalishvili, G.; Rauberg, J.; Miyoshi, Y.; Tsuchiya, F.; et al. Relation of the plasmapause to the midlatitude ionospheric trough, the sub-auroral temperature enhancement and the distribution of small-scale field aligned currents as observed in the magnetosphere by THEMIS, RBSP, and Arase, and in the topside ionosphere by Swarm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2022, 127, e2021JA029646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggi, R.K.; Wolf, R.A. Self-consistent calculation of the motion of a sheet of ions in the magnetosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research 1973, 78, 2852–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasyliunas, V.M. Mathematical Models of Magnetospheric Convection and its Coupling to the Ionosphere. In: McCormac, B.M. (eds) Particles and Fields in the Magnetosphere. Astrophysics and Space Science Library 1970, 17, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasyliunas, V.M. The Interrelationship of Magnetospheric Processes. In Earth’s Magnetospheric Processes. Astrophysics and Space Science Library; McCormac, B.M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, 1972; Volume 32, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, C.; Blanc, M. On the control of magnetospheric convection by the spatial distribution of ionospheric conductivities. Journal of Geophysical Research 1984, 89(A1), 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.C.; Makela, J.J.; Chau, J.L.; Nicolls, M.J. Penetration of the solar wind electric field into the magnetosphere/ionosphere system. Geophysical Research Letters 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.S.; Foster, J. C.; Kelley, M.C. Long-duration penetration of the interplanetary electric field to the low-latitude ionosphere during the main phase of magnetic storms. Journal of Geophysical Research 2005, 110(A11), A11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, N.; Sazykin, S.; Spiro, R.W.; Anderson, D.; Anghel, A.; Wolf, R.A.; Toffoletto, F.; Fuller-Rowell, T.J.; Codrescu, M.V.; Richmond, A.D.; Millward, G.H. Modeling storm-time electrodynamics of the low latitude ionosphere-thermosphere system: can long lasting disturbance electric fields be accounted for? Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2007, 69, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, M.-T.; Grocott, A. Modeling the time-variability of the ionospheric electric potential (TiVIE). Space Weather 2025, 23, e2024SW004139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.A. Relationship of the plasma sheet, ring current, trapping boundary, and plasmapause near the magnetic equator and local midnight. Journal of Geophysical Research 1971, 76, 2,265–2,275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, Yu.I.; Feldstein, Ya.I. Mapping of the precipitation region to the plasma sheet. Journal of geomagnetism and geoelectricity 1996, 48, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M. Midlatitude convection electric fields and their relation to ring current development. Geophysical Research Letters 1978, 5, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M. Magnetospheric convection effects at mid-latitudes 1. Saint-Santin observations. Journal of Geophysical Research 1983, 88, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schield, M. A.; Freeman, J.W.; Dessler, A.J. A source for field-aligned currents at auroral latitudes. Journal of Geophysical Research 1969, 74, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DMSP F15 observed eastward SAPS Event | DMSP F15 observables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event Number |

Event Date |

UT (Hr:Mn) | MLAT (oS) | MLT (Hr:Mn) | Ne 103 (cm−3) |

VHOR (m/s) | Te (K) |

| 1 | 22 February 2015 | 00:08 | 60.22 | 23:36 | 3.5 | −2200 | 5500 |

| 2 | 22 February 2015 | 23:52 | 59.88 | 23:45 | 2.8 | −2000 | 6600 |

| 3 | 3 March 2015 | 01:07 | 57.36 | 23:48 | 2.5 | −2600 | 7400 |

| 4 | 4 March 2015 | 02:34 | 56.76 | 23:48 | 3.5 | −1200 | 6400 |

| 5 | 6 March 2015 | 00:21 | 61.49 | 23:17 | 3.2 | −1300 | 6000 |

| 6 | 10 March 2015 | 23:12 | 65.45 | 22:36 | 2.5 | −3100 | 7000 |

| 7 | 8 September 2015 | 06:32 | 55.57 | 01:47 | 1.1 | +2800 | 6000 |

| 8 | 8 September 2015 | 08:13 | 57.46 | 02:30 | 1.1 | +2200 | 7000 |

| 9 | 7 October 2015 | 00:23 | 54.57 | 00:47 | 1.0 | +3200 | 6400 |

| 10 | 28 January 2016 | 22:41 | 62.32 | 23:29 | 3.5 | −1400 | 6100 |

| 11 | 25 February 2016 | 21:57 | 63.23 | 23:37 | 2.8 | −2000 | 6700 |

| 12 | 29 February 2016 | 00:35 | 60.71 | 23:12 | 2.5 | −1400 | 5500 |

| 13 | 10 March 2016 | 01:17 | 58.48 | 23:36 | 2.1 | −2000 | 7500 |

| 14 | 10 March 2016 | 03:06 | 58.34 | 23:36 | 3.0 | −2000 | 5500 |

| 15 | 11 March 2016 | 02:44 | 57.66 | 23:39 | 2.5 | −2500 | 6000 |

| 16 | 12 March 2016 | 00:45 | 58.76 | 23:40 | 2.8 | −1500 | 5800 |

| 17 | 22 March 2016 | 03:13 | 60.70 | 23:30 | 2.5 | −2200 | 6400 |

| SAPS Event |

UT (Hr:Mn) |

IMF (nT) | SYM-H (nT) |

Kp | AE (nT) |

Substorm onset | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BY | BZ | UT (Hr:Mn) | MLT (Hr) | |||||

| 22 February 2015 | 00:08 | −5.26 | −4.41 | −18 | 2+ | 230 | 23:10# | 1.28 |

| 22 February 2015 | 23:52 | −6.48 | −4.43 | −8 | 4− | 171 | 23:34♦ | 1.29 |

| 3 March 2015 | 01:07 | 0.37 | −3.00 | −18 | 3 | 282 | 00:06*# | 1.76 |

| 4 March 2015 | 02:34 | 1.34 | 2.72 | −7 | 2 | 43 | 00:54* | 0.21 |

| 6 March 2015 | 00:21 | 3.86 | 2.86 | −1.20 | 1+ | 79 | - | - |

| 10 March 2015 | 23:12 | 3.58 | 3.51 | 5 | 3 | 33 | - | - |

| 8 September 2015 | 06:32 | −6.20 | 13.47 | −34 | 3− | 29 | - | - |

| 8 September 2015 | 08:13 | 0.80 | 15.32 | −27 | 3− | 36 | 07:02* | 9.39 |

| 7 October 2015 | 20:57 | 4.48 | −5.8 | −105 | 7+ | 634 | 20:07# | 7.71 |

| 28 January 2016 | 22:41 | 3.67 | 0.97 | −13 | 1− | 26 | - | - |

| 25 February 2016 | 21:57 | 8.20 | 4.42 | 5 | 2 | 42 | - | - |

| 10 March 2016 | 01:17 | −1.55 | −2.42 | −23 | 2 | 39 | 00:12* | 1.31 |

| 10 March 2016 | 03:06 | - | - | −22 | 3− | 75 | - | - |

| 11 March 2016 | 02:44 | −4.54 | 1.97 | −14 | 1+ | 208 | 00:29* | 2.48 |

| 12 March 2016 | 00:45 | −4.34 | −3.44 | −17 | 3 | 243 | 00:13♦ | 1.81 |

| 22 March 2016 | 03:13 | 0.45 | −3.65 | −16 | 2+ | 107 | 02:47# | 0.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).