Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

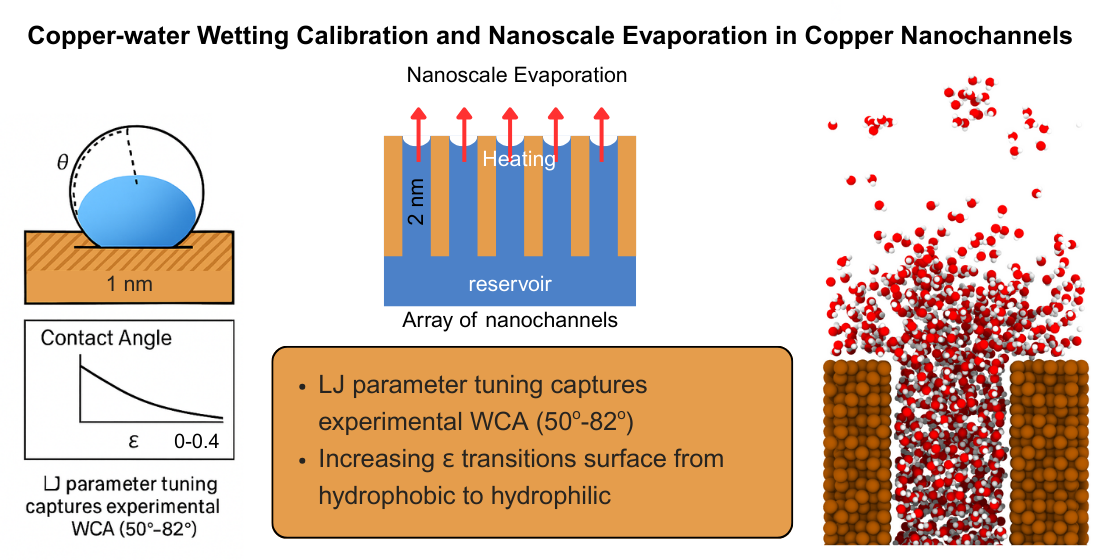

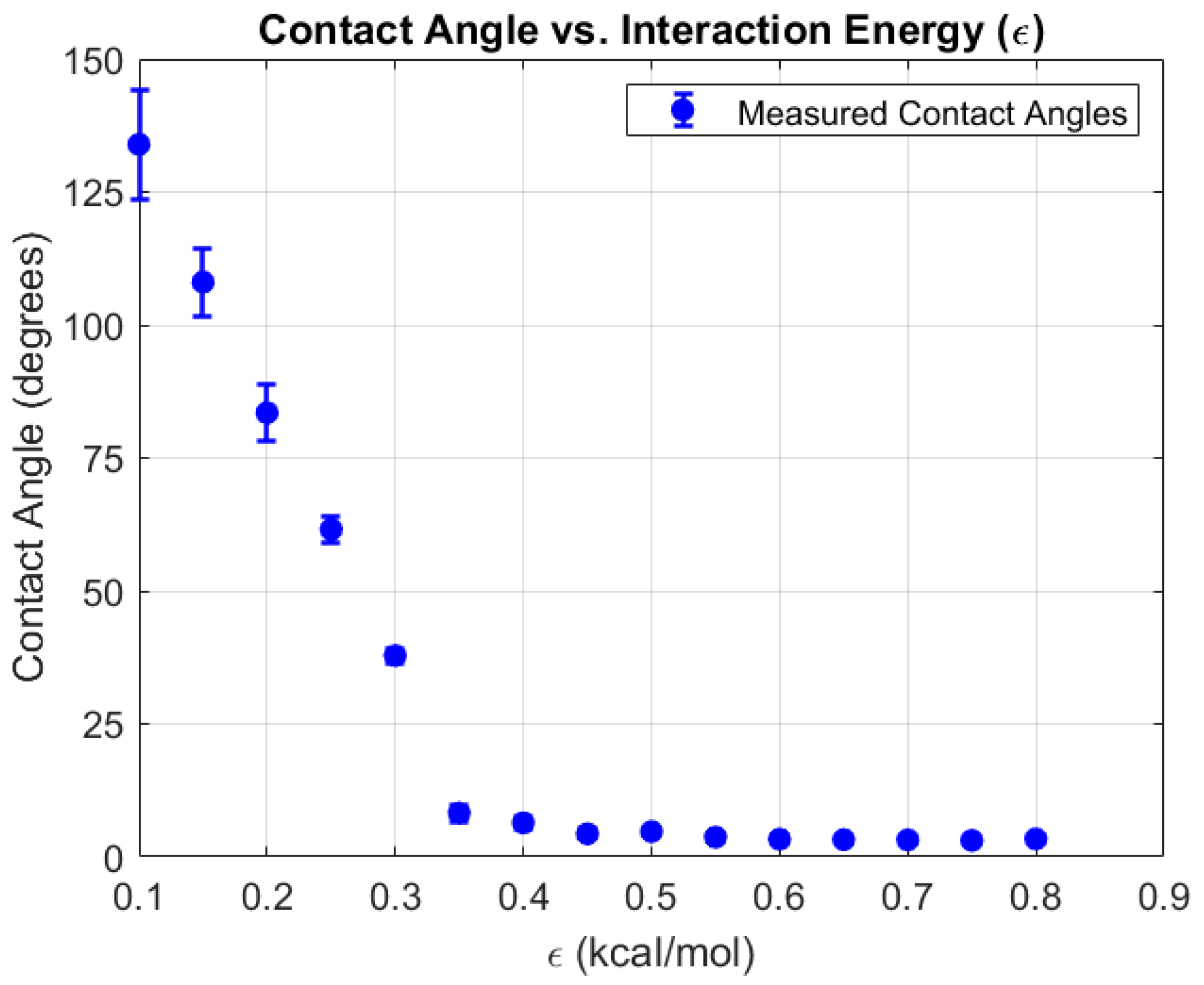

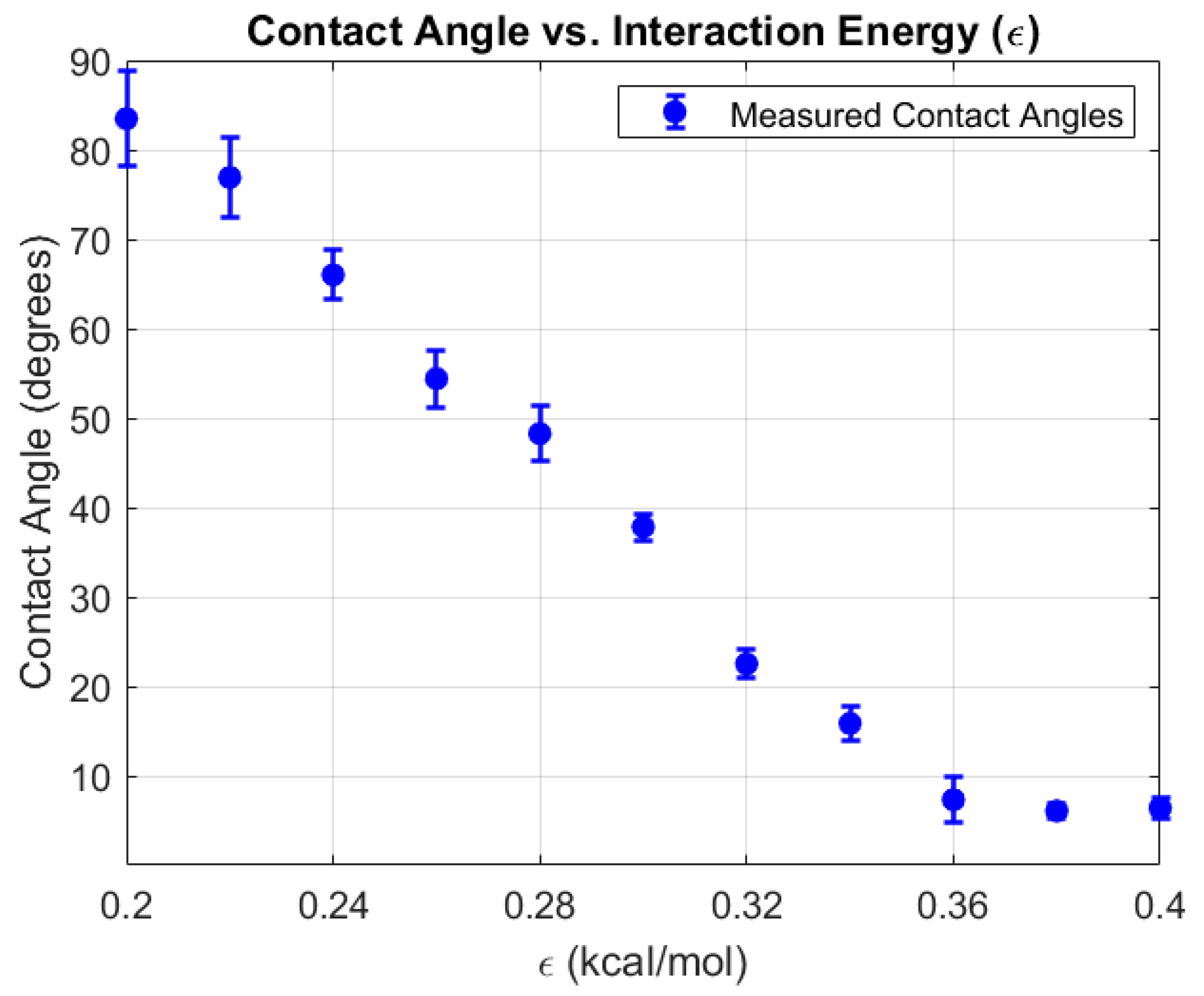

2. Copper-Water Interaction Force Field Estimation

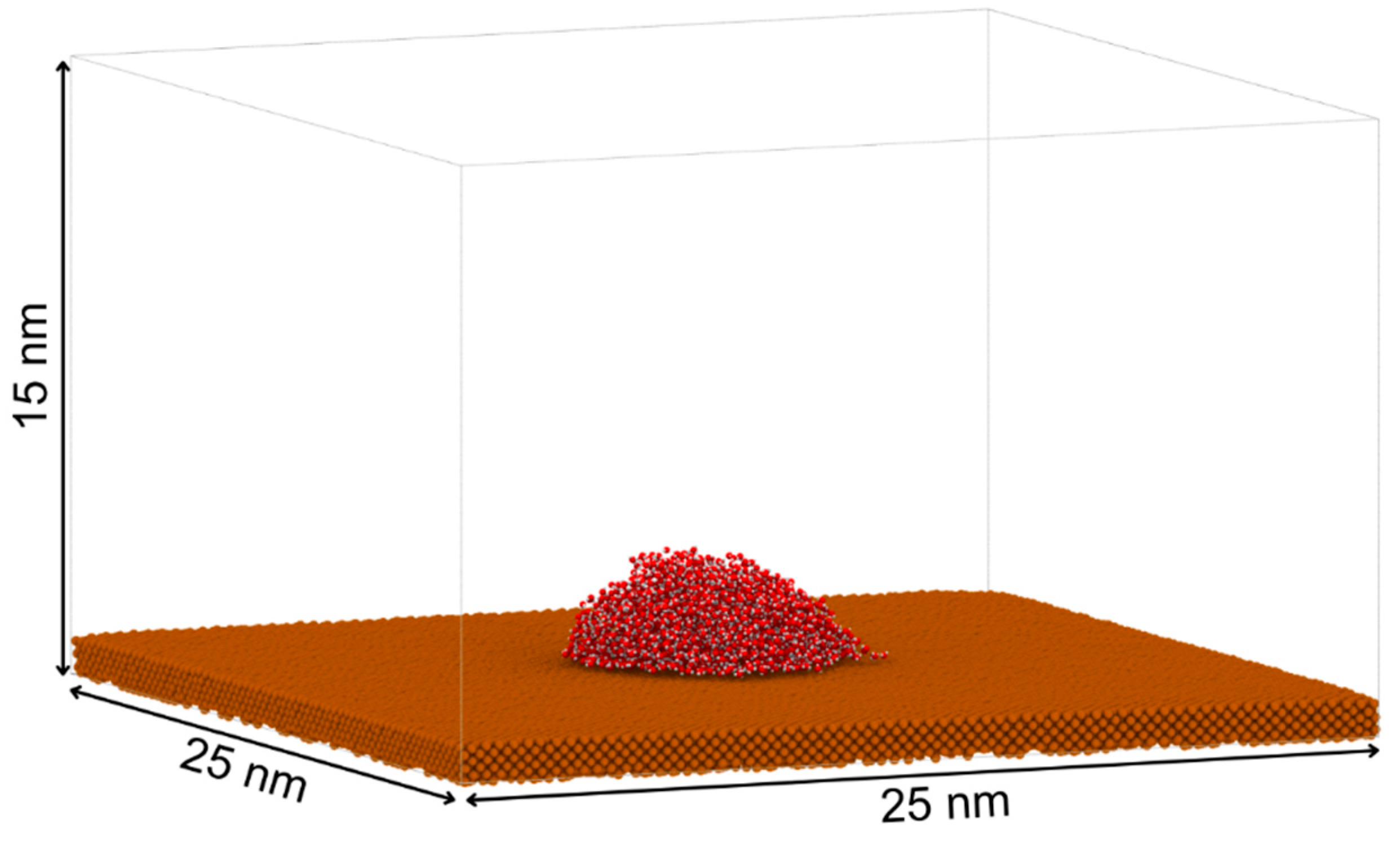

Model Construction

Force Fields and Interactions

Simulation Protocol

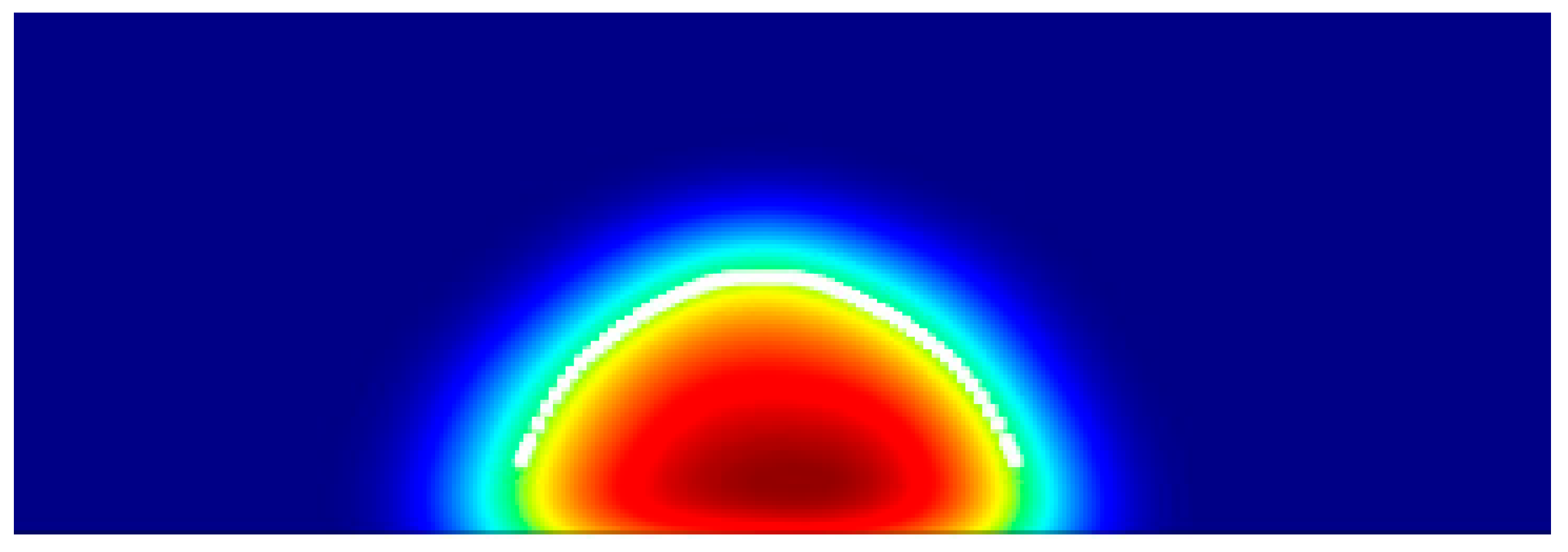

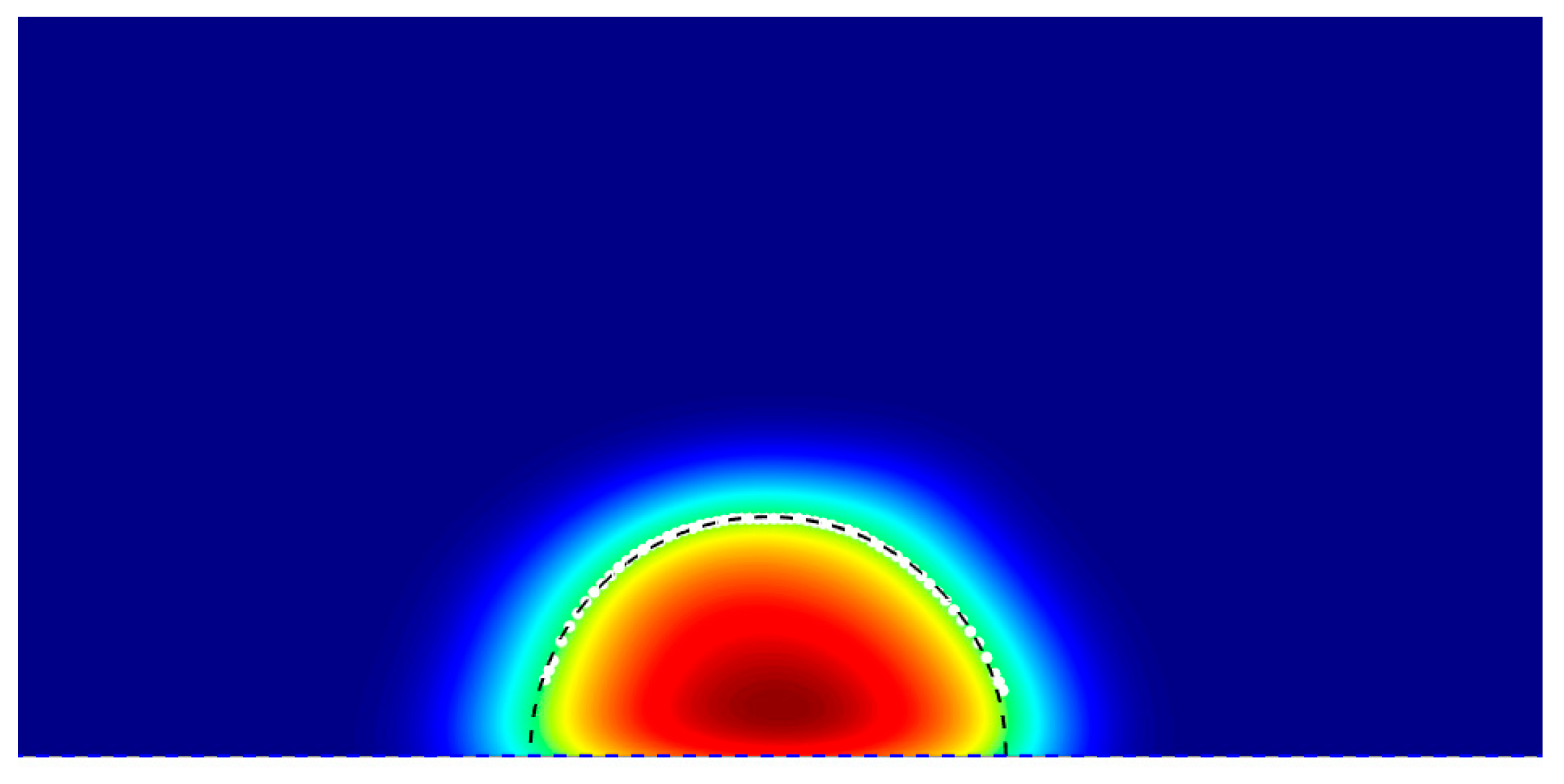

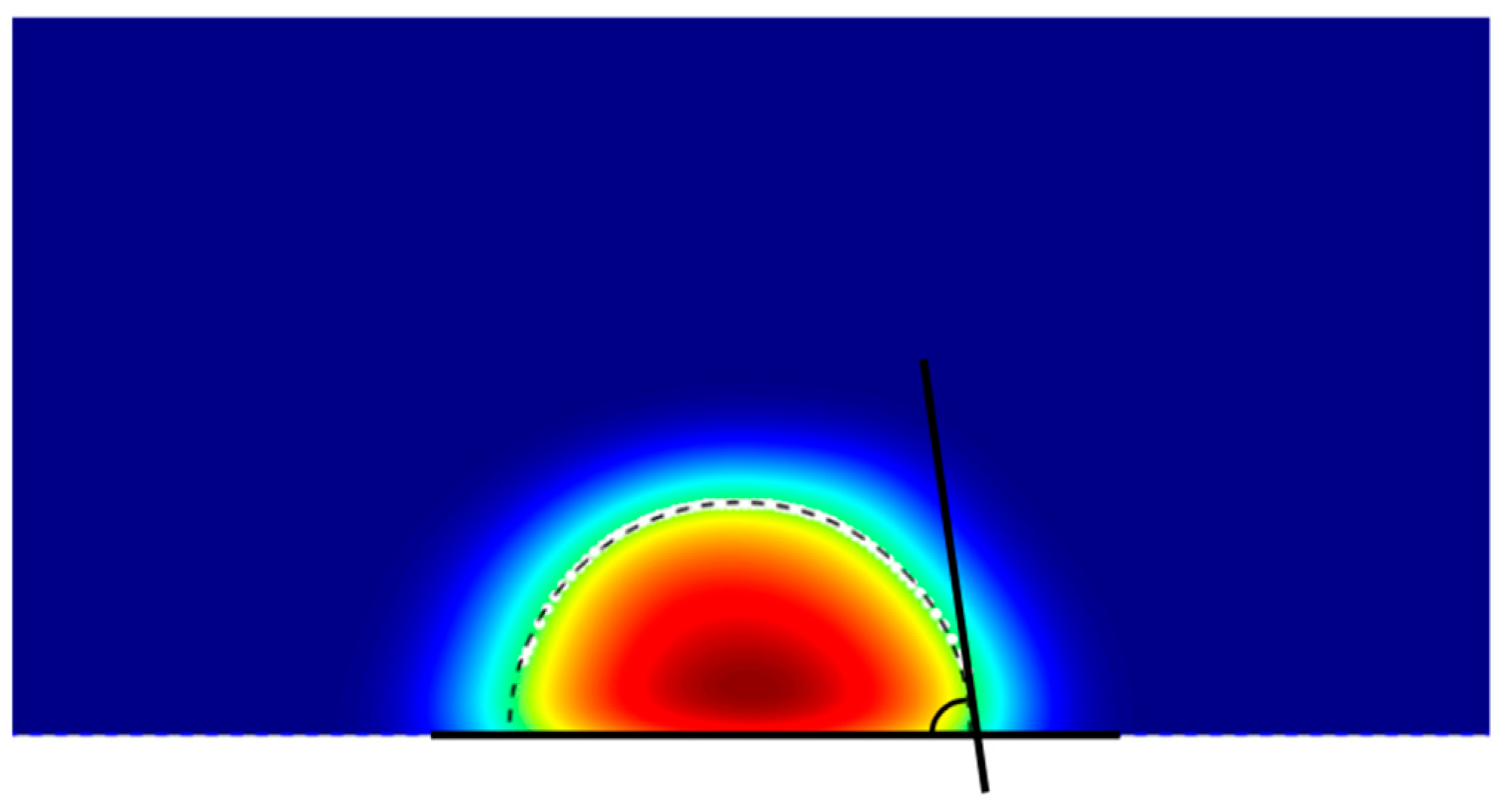

Contact Angle Estimation Protocol

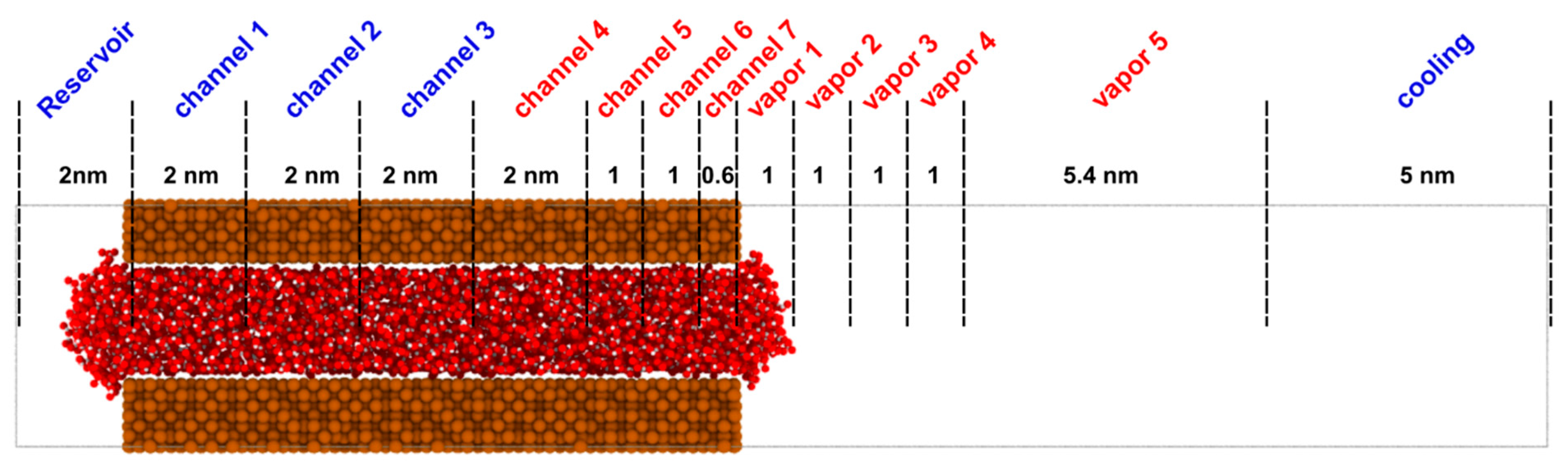

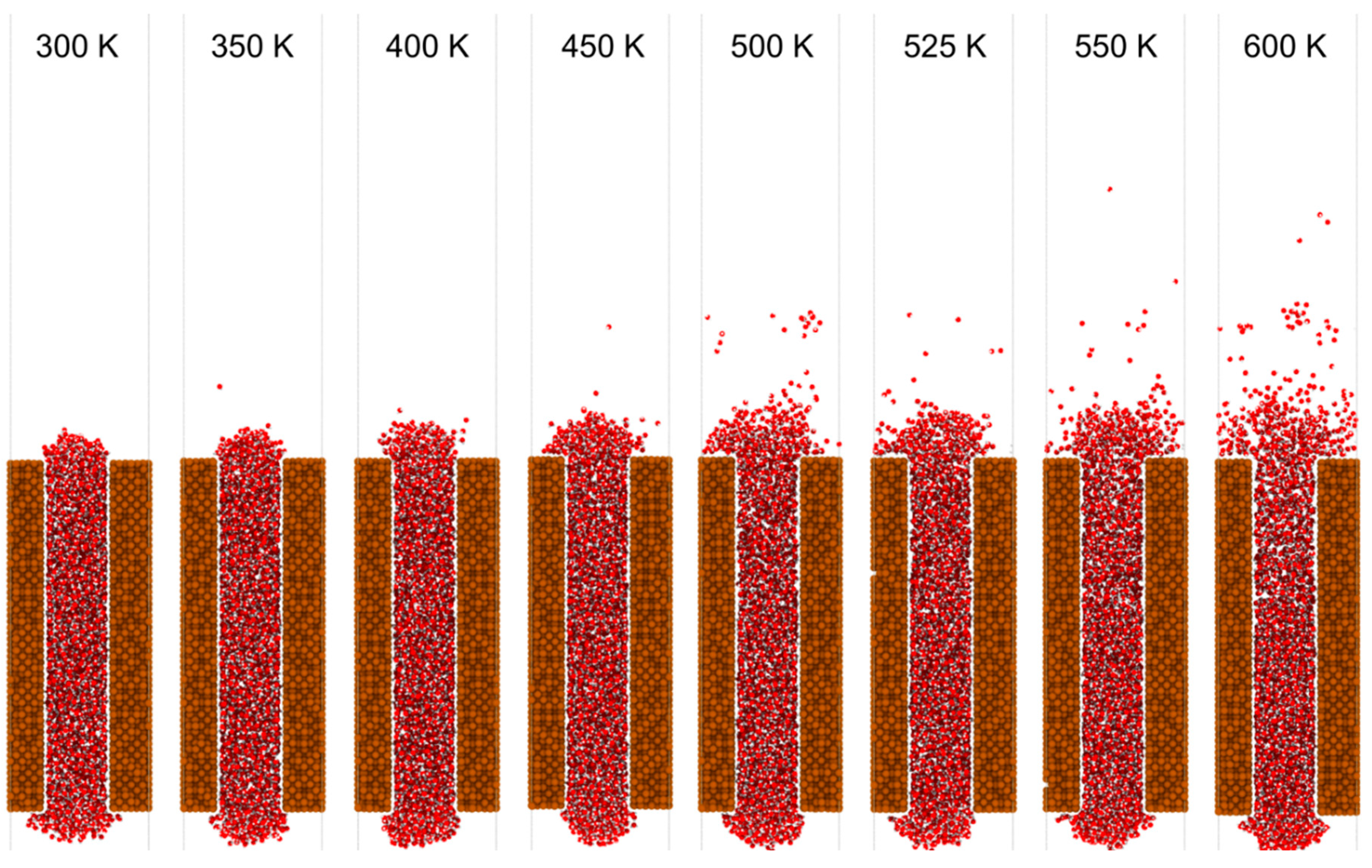

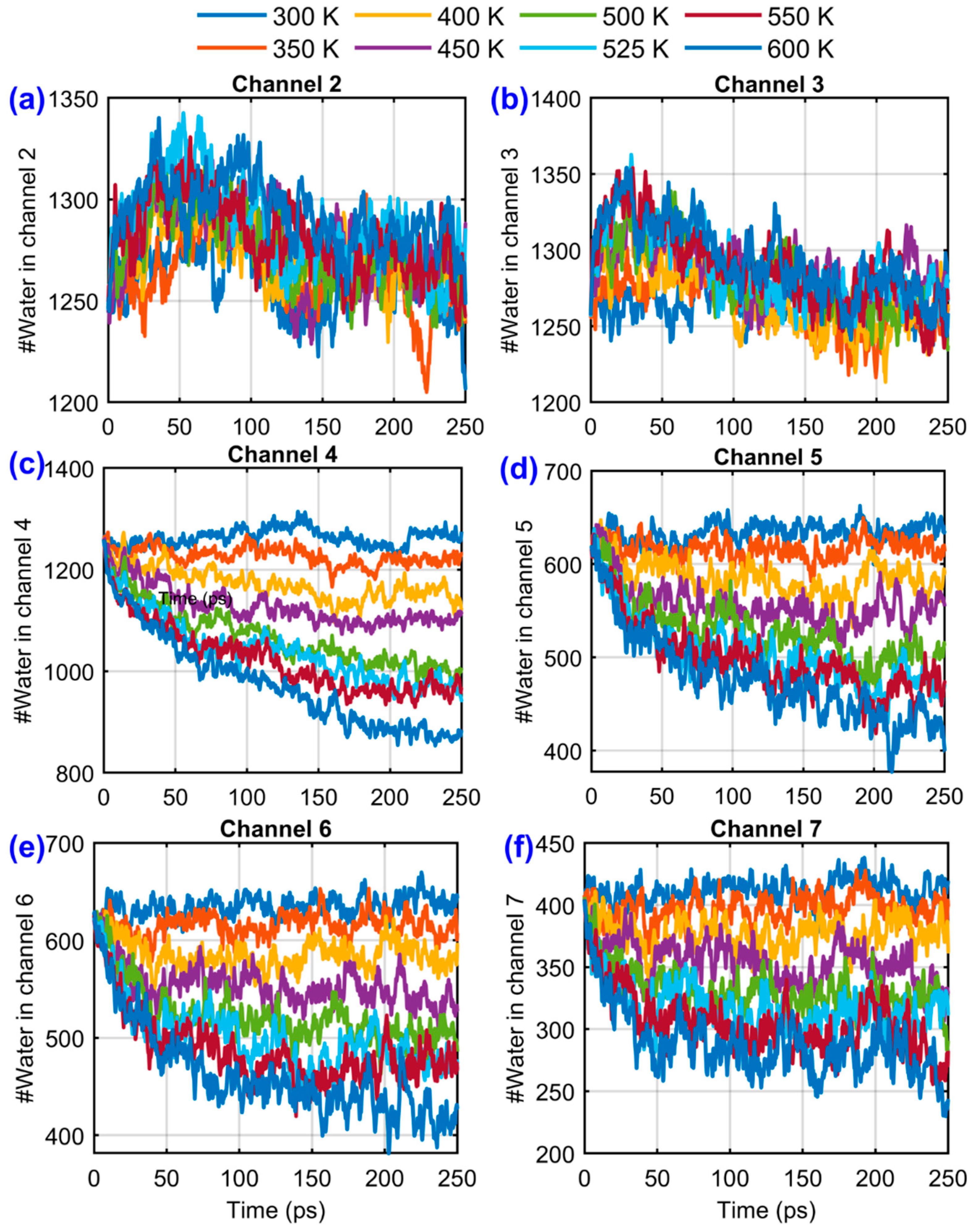

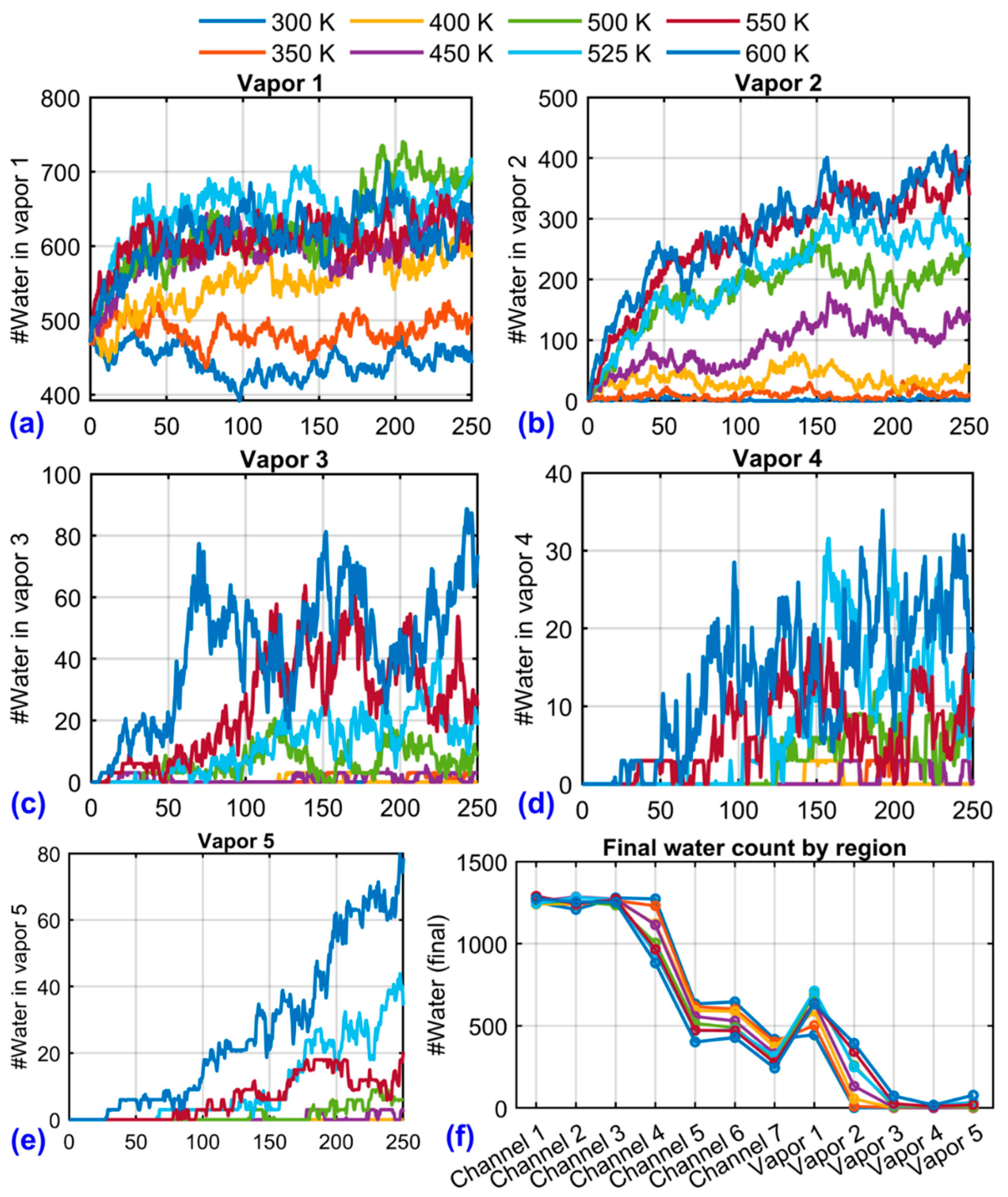

3. Nanochannel Evaporation Studies

3.1. Materials and Methods for Nanochannel Evaporation

3.2. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Data Availability:

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stewart, C.L.; Goldblum, B.L.; Abbott, R.G.; Appleby, L.; Borghetti, B.J.; Hollingshead, V.; Whetzel, J.H. Machine Learning for Reactor Power Monitoring with Limited Labeled Data. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2025, 1073, 170285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E. Machine Learning-Driven Uncertainty Quantification and Parameter Analysis in Fire Risk Assessment for Nuclear Power Plants. 2025.

- Ramezani, I.; Moshkbar-Bakhshayesh, K.; Vosoughi, N.; Ghofrani, M.B. Applications of Soft Computing in Nuclear Power Plants: A Review. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2022, 149, 104253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafleur, B. Development and Assessment of Machine Learning Techniques for Non-Intrusive Probabilistic Surrogate Modeling of High-Fidelity Nuclear Reactor Simulations. PhD Thesis, 2023.

- Huang, H.; Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Sui, D.; Xie, F.; Ding, H. Research on a Rapid Prediction Method for Multi-Physics Coupled Fields in Small Lead-Cooled Fast Reactors Based on Machine Learning. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2025, 438, 114065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Prasianakis, N.; Churakov, S.V.; Pfingsten, W. Performance Analysis of Data-Driven and Physics-Informed Machine Learning Methods for Thermal-Hydraulic Processes in Full-Scale Emplacement Experiment. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 245, 122836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal, J.L.; Vega, C. A General Purpose Model for the Condensed Phases of Water: TIP4P/2005. The Journal of chemical physics 2005, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirel, P. Atomsk: A Tool for Manipulating and Converting Atomic Data Files. Computer Physics Communications 2015, 197, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumanis, M.E.; Yu, L.S. Lattice Parameters, Densities, Expansion Coefficients and Perfection of Structure of Cu and of Cu–In α Phase. Foundations of Crystallography 1969, 25, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K. Lattice Dynamics of Copper. Phys. Rev. 1966, 143, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jona, F.; Marcus, P.M. Structural Properties of Copper. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 094113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.L.; Faulkner, J.S.; Joy, H.W. Calculation of the Band Structure for Copper as a Function of Lattice Spacing. Phys. Rev. 1968, 167, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, W.P. Precision Measurements of the Lattice Constants of Twelve Common Metals. Phys. Rev. 1925, 25, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YD, S.; Maroo, S.C. Origin of Surface-Driven Passive Liquid Flows. Langmuir 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; In’t Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D. LAMMPS-a Flexible Simulation Tool for Particle-Based Materials Modeling at the Atomic, Meso, and Continuum Scales. Computer physics communications 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal, J.L.; Vega, C. A General Purpose Model for the Condensed Phases of Water: TIP4P/2005. The Journal of chemical physics 2005, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammonds, K.D.; Ryckaert, J.-P. On the Convergence of the SHAKE Algorithm. Computer physics communications 1991, 62, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.C. Rattle: A “Velocity” Version of the Shake Algorithm for Molecular Dynamics Calculations. Journal of computational Physics 1983, 52, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-J.; Ko, W.-S.; Kim, H.-K.; Kim, E.-H. The Modified Embedded-Atom Method Interatomic Potentials and Recent Progress in Atomistic Simulations. Calphad 2010, 34, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-J.; Baskes, M.I. Second Nearest-Neighbor Modified Embedded-Atom-Method Potential. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, 8564–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskes, M.I. Determination of Modified Embedded Atom Method Parameters for Nickel. Materials Chemistry and Physics 1997, 50, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskes, M.I. Modified Embedded-Atom Potentials for Cubic Materials and Impurities. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 2727–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Dhir, V.K. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Contact Angle of Liquids on Solid Surfaces. The Journal of chemical physics 2009, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węglarczyk, S. Kernel Density Estimation and Its Application. In Proceedings of the ITM web of conferences; EDP Sciences, 2018; Vol. 23; p. 00037. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-C. A Tutorial on Kernel Density Estimation and Recent Advances. Biostatistics & Epidemiology 2017, 1, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Matlab Software for Spatial Panels. International Regional Science Review 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C. Molecular Dynamics Study Of Phase Change And Interfacial Behavior In Nanoconfined Argon. 2025.

- Eyupoglu, C. Implementation of Bernsen’s Locally Adaptive Binarization Method for Gray Scale Images. The Online Journal of Science and Technology 2017, 7, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chernov, N.; Lesort, C. Least Squares Fitting of Circles. J Math Imaging Vis 2005, 23, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, P.J.; Doksum, K.A. Mathematical Statistics: Basic Ideas and Selected Topics, Volumes I-II Package; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning; Springer Texts in Statistics; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-7137-0. [Google Scholar]

| Eps (kcal/mol) | Contact Angle (°) | Std. Dev. (°) | Experimental WCA (°) |

| 0.2 | 83.48 | 5.28 | 82.3 |

| 0.22 | 76.91 | 4.51 | |

| 0.24 | 66.01 | 2.72 | |

| 0.26 | 54.42 | 3.2 | 50.2 |

| 0.28 | 48.27 | 3.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).