1. Introduction

Palliative radiotherapy (PRT) plays a pivotal role in the management of advanced cancer patients, offering effective relief from symptoms such as pain, bleeding, or neurological deficits caused by tumor progression [

1,

2,

3]. These patients frequently present with a high symptom burden, arising not only from the underlying malignancy but also from the adverse effects of systemic therapies [

4,

5]. Beyond the physical domain, psychological distress is also highly prevalent, often resulting from a complex interplay of poorly controlled symptoms, existential concerns, and the emotional impact of an incurable illness [

6,

7,

8]. Clinical decision-making regarding the administration of PRT is inherently complex, particularly in terms of appropriateness, timing, and dose-fractionation regimens. In this context, a comprehensive, patient-centered approach becomes essential. Integrating radiation oncology with palliative care services within a dedicated clinical setting promotes a more holistic assessment and facilitates shared decision-making [

9,

10]. Our institution has implemented this model through the Radiotherapy and Palliative Care (RaP) outpatient clinic, a multidisciplinary service in which radiation oncologists and palliative care specialists collaborate in the evaluation and management of patients referred for PRT. Preliminary experience from this clinic has demonstrated improvements in care quality, including more appropriate patient selection for radiotherapy and timely access to supportive and palliative care services [

11].

To further enhance individualized care, it is crucial to consider symptoms not as isolated entities but as interrelated phenomena that may reflect underlying syndromic patterns. The concept of symptom clusters (SC) - defined as groups of two or more concurrent and interrelated symptoms with potential shared pathophysiology - has gained prominence as a framework for understanding the multidimensional symptom burden in advanced cancer [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

SCs identification may shed light on the shared mechanisms behind symptom co-occurrence and may support more effective and targeted symptom management strategies. Among the most widely used tools for symptom assessment in oncology is the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), a validated instrument that evaluates eight symptoms (pain, tiredness, drowsiness, nausea, loss of appetite, dyspnea, depression, anxiety) and malaise (i.e., reduced well-being) using a numerical rating scale (NRS)[

19].

This secondary analysis of the RaP study by Rossi et al.[

11] aims to retrospectively identify SCs through ESAS in patients referred for PRT.

2. Materials and Methods

This study represents a secondary, post hoc retrospective cohort analysis of the RaP clinic database. In particular all patients evaluated in the RaP clinic between February 2017 to April 2020 were included.

All patients before entering the joint visit with the radiotherapist and the palliative care physician completed the Italian Validated version of ESAS [

20], in the presence of a specialist nurse.

For all patients demographic (i.e., gender and age at first RaP visit) and clinical data (i.e., ECOG PS according to radiotherapist and palliativist) were recorded. Primary tumor site, metastasis site and the presence of locally advanced cancer were recorded too. Moreover ESAS items NRS scores were recorded for all patients.

Statistical Analysis

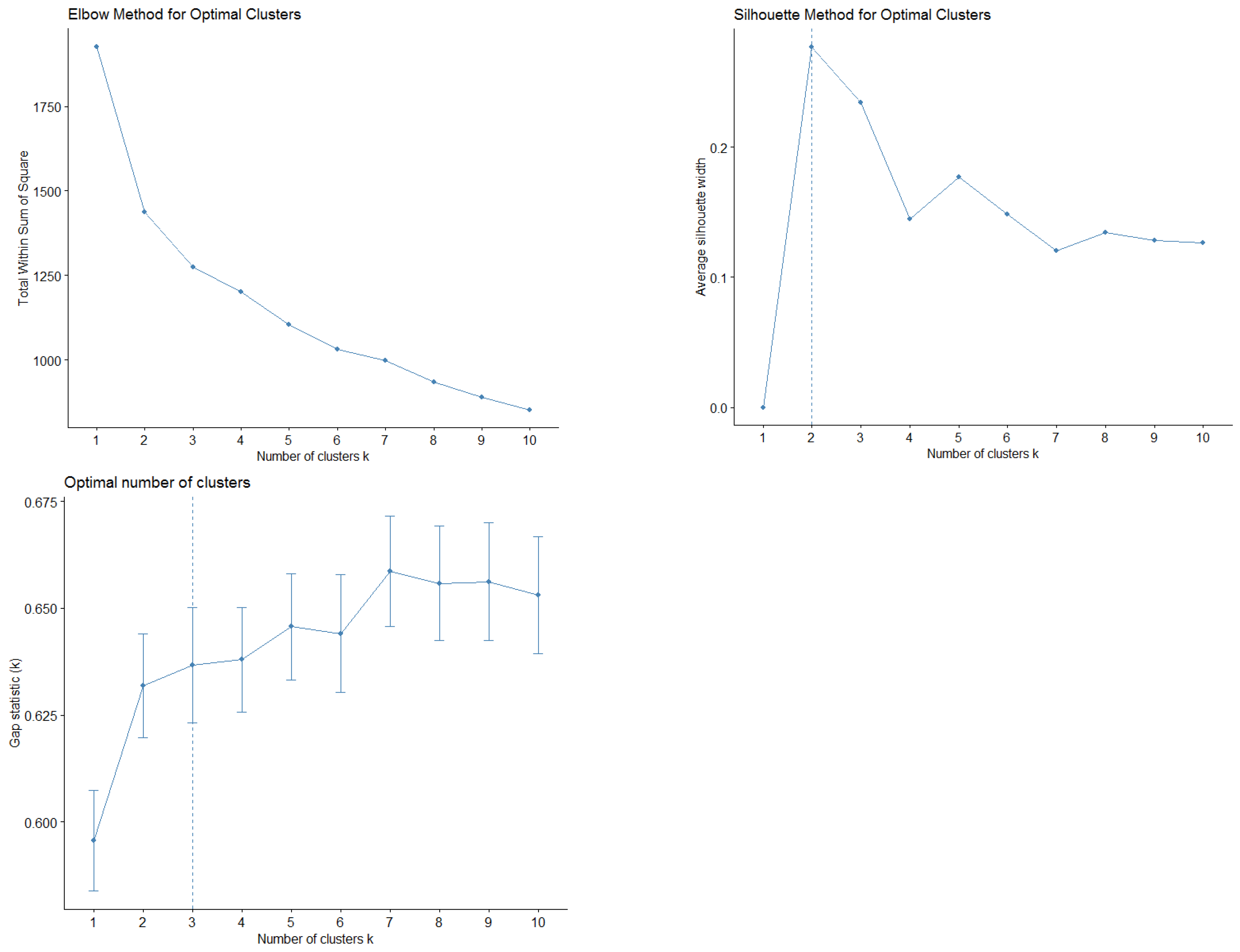

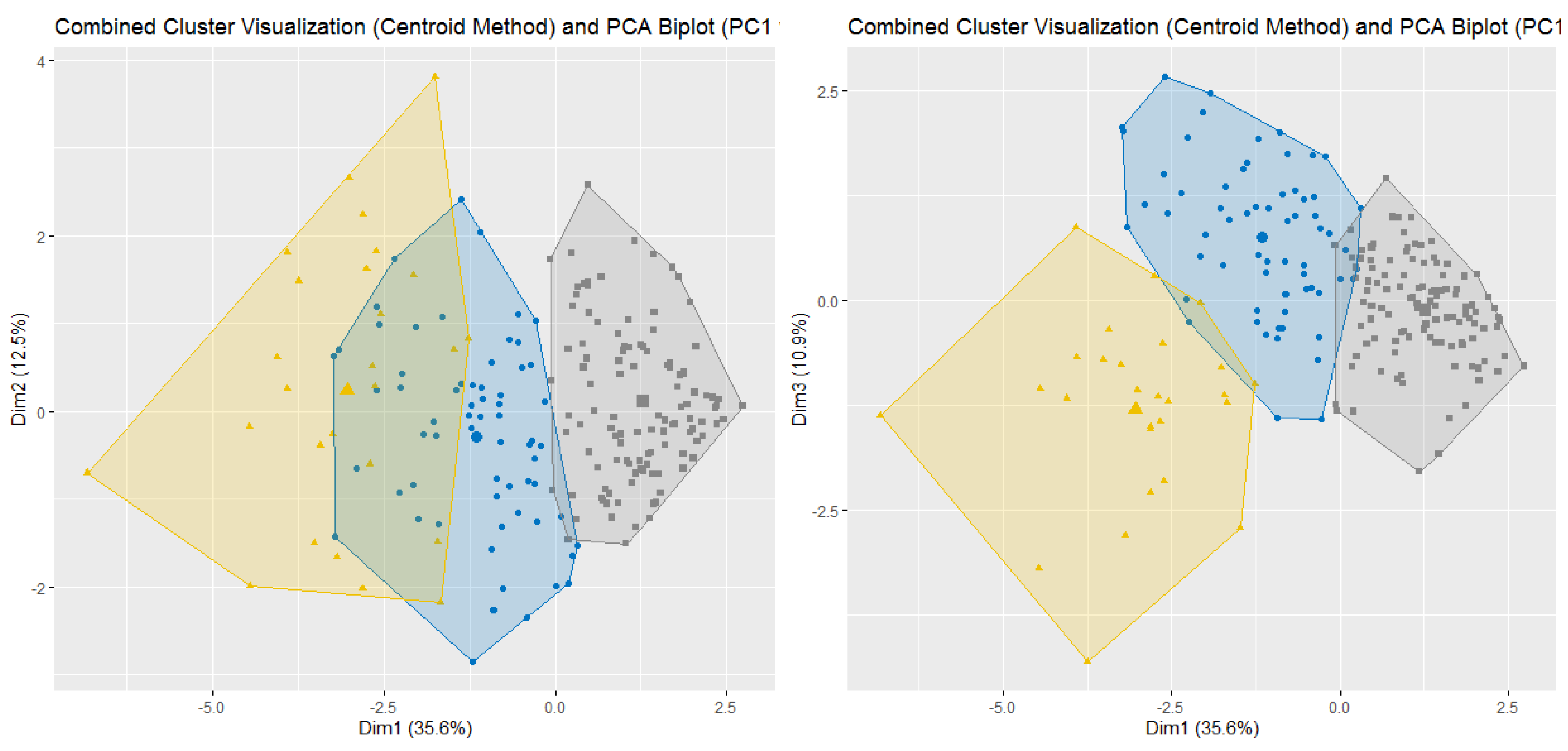

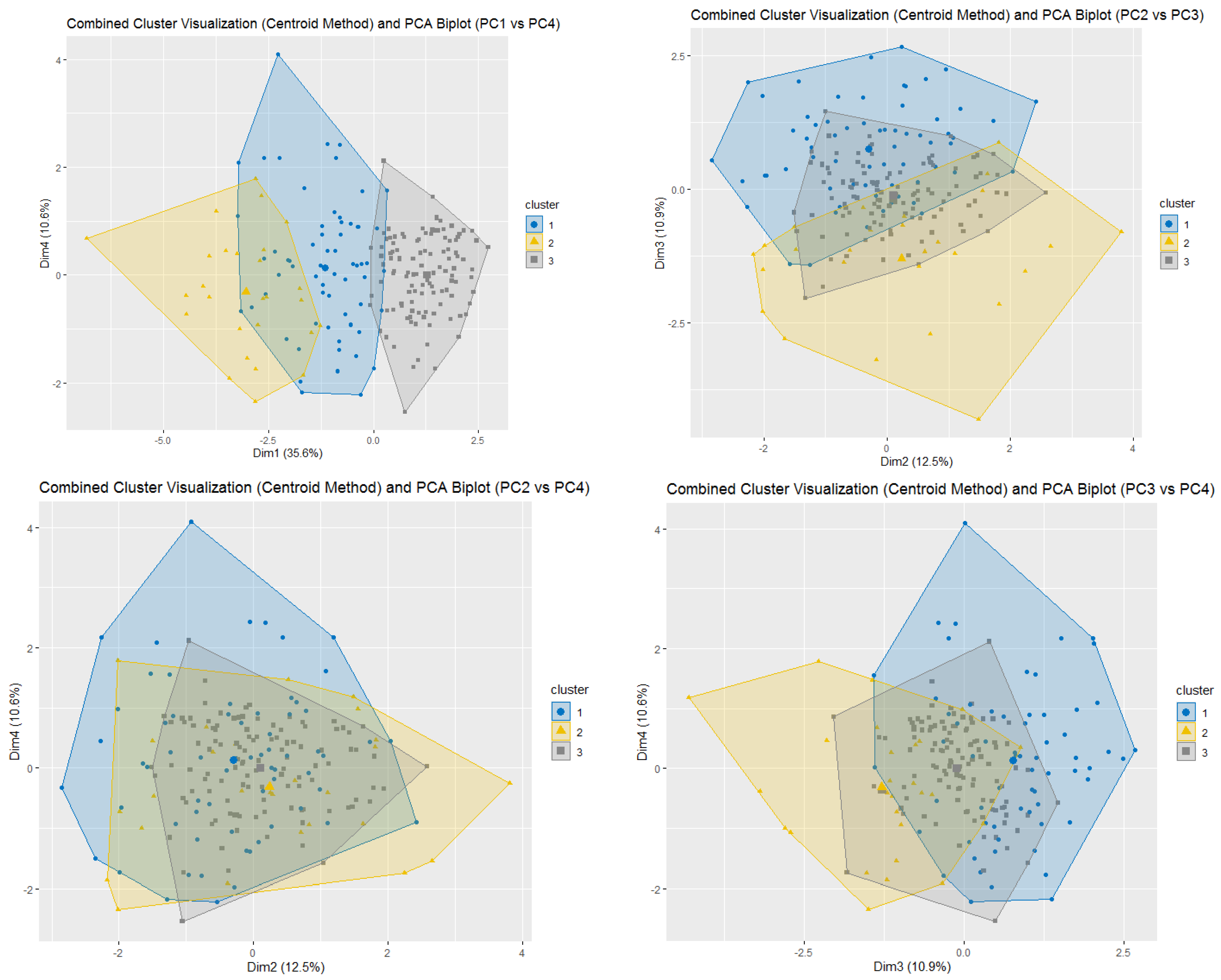

Demographic and baseline clinical data was summarized by means of absolute frequencies and relative percentages. To describe each ESAS item, mean, standard deviation and the proportion of patients presenting a score greater or equal to four were reported. Furthermore, SCs were identified using both Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and unsupervised k-means clustering (KMC). In practice, to explore potential patterns of association (i.e., linear combinations) between ESAS items, a PCA with varimax rotation was performed. Indeed, the PCA transforms several observed variables into a reduced number of variables called principal components. Pragmatically, prior to the analysis, all variables were standardized to ensure comparability and minimize scale-related bias. Essentially, the varimax rotation was used to maximize the variance of a column of the factor pattern matrix. Significant principal components were selected with an eigenvalue higher than 0.8, and each component explained at least 10% of the variance. The highest factor loading score was used for assigning the ESAS items to an independent factor. The set of items assigned to the same independent factor collectively compose a cluster. Robust relationships and correlations among symptoms were displayed with the bi-plot representation. Subsequently, unsupervised k-means clustering was applied to the scaled data to identify natural groupings of the patients based on their ESAS symptoms. The optimal number of clusters was determined using a combination of statistical methods, namely the Elbow method (within-cluster sum of squares), the Silhouette method and the Gap Statistic. The final number of clusters was selected based on the maximum gap statistic and interpretability, resulting in a three-cluster solution. To further interpret cluster structures, between-cluster variance and R2 statistics were computed for each variable. R2 for each variable was calculated as the ratio of between-cluster sum of squares to total sum of squares. Additionally, a separation metric was derived to compare each variable’s fit within its assigned cluster versus the best alternative cluster.

To investigate the association between SCs and the likelihood of receiving PRT logistic regression models were developed. The binary outcome variable was defined as receipt of RT (1 = yes; 0 = no). Predictor variables included membership in SCs as derived from principal component analysis (PCA1–PCA4) and k-means cluster analysis (CL1–CL3). Specifically, each patient was classified as a SC belonging if at least half of the symptoms of a cluster were reported as clinically relevant (ESAS item score ≥ 4).

Univariate logistic regressions were performed separately for each SC to assess their individual association with RT. Finally, multivariable models including interaction terms were tested to explore potential combined effects among SCs. Model selection was guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) using backward stepwise selection. Coherently, final model coefficients were exponentiated and reported as odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Moreover, to assess associations between SCs and clinical characteristics (e.g., ECOG status, primary tumor site, metastatic locations), chi-square tests of independence were conducted.

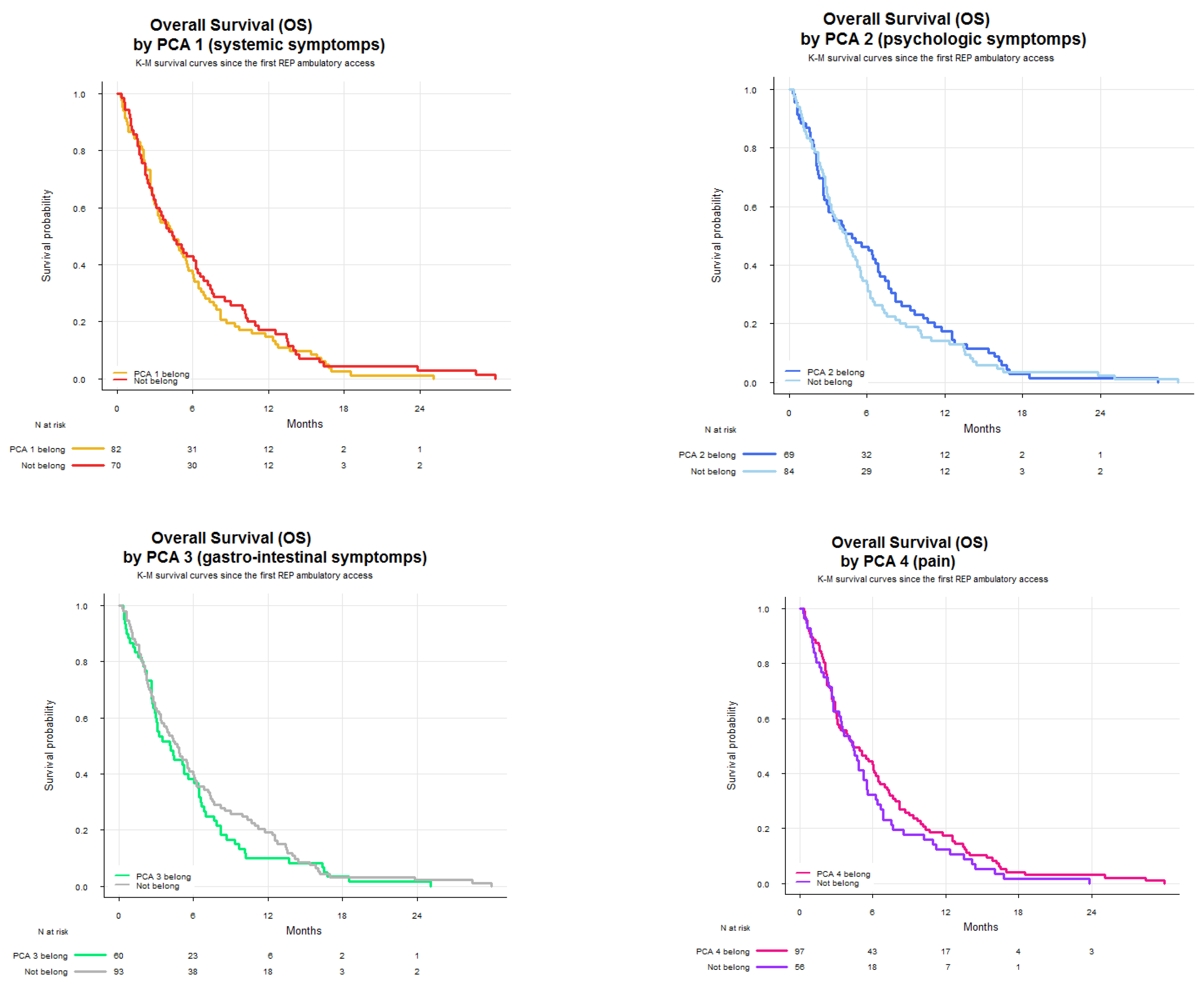

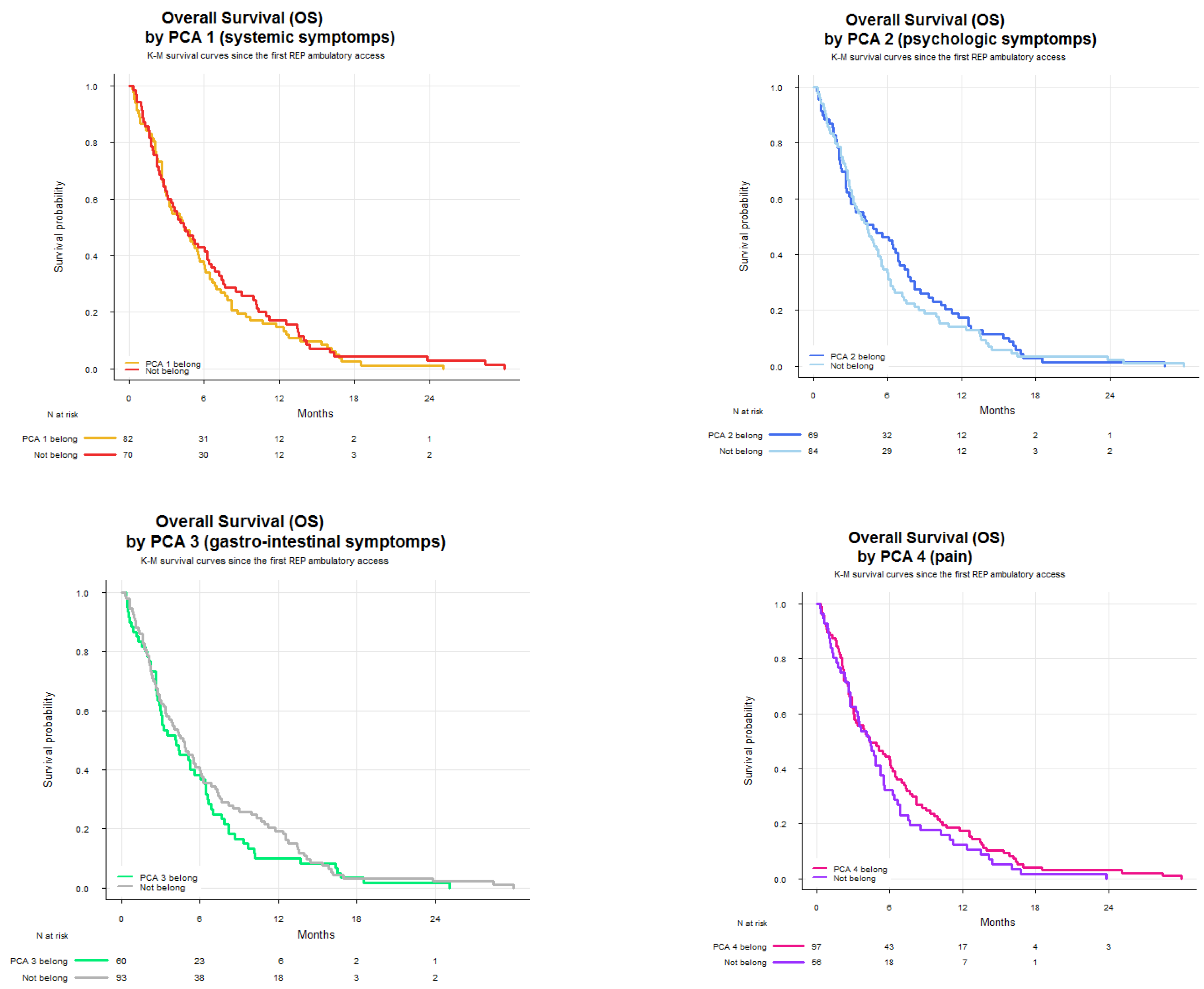

Finally, Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to compare overall survival (OS) across PCA and KMC groups. OS was defined as the time from the first RaP consultation to death or last follow-up, and expressed in months. Survival curves were drawn separately for each symptom cluster and grouped by patients belonging to each cluster.

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.4.2). The ‘psych’, ‘factoextra’ and ‘cluster’ libraries were used for performing the PCA and K-means cluster analysis. Finally, ‘ggplot2’ package was used for drawing the figures and graphs.

4. Discussion

PRT represents a cornerstone in the symptomatic management of patients with advanced-stage cancer. Nevertheless, estimating the net clinical benefit of PRT - balancing symptom relief against potential treatment-related toxicity - remains challenging in the absence of a structured pre-treatment symptom assessment. In this context, a thorough evaluation of the patient’s physical condition, psychological status, and prognosis is essential for making personalized treatment decisions. Over the last decade, several studies have highlighted the utility of a multidisciplinary and multidimensional approach, particularly emphasizing the collaboration between radiation oncologists and palliative care specialists in defining treatment indications and timing [

21,

22,

23,

24]. In Italy, the RaP outpatient clinic represents one of the few structured initiatives incorporating this collaborative model into routine clinical care [

11].

Within this setting, we analyzed SCs with the aim of improving symptom monitoring and exploring their potential role in guiding therapeutic decisions. The PCA identified four clusters. SCPCA1, comprising tiredness, drowsiness, dyspnea, and malaise, is consistent with a systemic cluster. SCPCA2, including depression and anxiety, represents a psychological cluster. SCPCA3, composed of nausea and loss of appetite, reflects a gastrointestinal cluster. Finally, SCPCA4, defined solely by pain, suggests a distinct somatic experience not strongly correlated with other symptoms. The k-means cluster analysis identified three clinically relevant SCs: SCKMC1 (pain, tiredness, drowsiness and malaise), representing a physical burden cluster; SCKMC2 (nausea, loss of appetite and dyspnea), indicating a visceral discomfort cluster; and SCKMC3 (depression and anxiety), mirroring a psychological cluster. These findings reinforce the concept that patients with advanced cancer frequently present with interrelated symptoms rather than isolated complaints.

A consistent and clinically meaningful association emerged between ECOG PS and SCs characterized by physical symptoms. Specifically, both SCPCA1 and SCKMC1, characterized by fatigue-related and somatic symptoms, were significantly associated with worse ECOG PS. These results suggest that systemic symptom burden, especially symptoms such as tiredness, drowsiness, and malaise, is closely linked to impaired functional status in this patient population. Conversely, no significant association was observed between ECOG PS and psychological symptom clusters (SCPCA2 and SCKMC3). This indicates that, in our cohort, psychological distress did not substantially influence patients’ performance status. While psychological symptoms may compromise quality of life or emotional well-being, they appear to play a limited role in determining physical functioning, at least as assessed by ECOG. This is consistent with previous findings by Nieder et al.[

25], who reported that nausea, fatigue, dry mouth, and appetite loss were significantly more prevalent in patients with poor PS. Although temporary symptom worsening post-PRT may occur in patients with poor PS, selected individuals—particularly those with dyspnea or pain—may still benefit from palliative RT. Similar results were also reported in older studies [

26,

27].

Although not statistically significant, we observed a consistent trend—across both PCA and KMC models—suggesting a stronger association between breast cancer as the primary tumor and psychological symptom clusters (SCPCA2 and SCKMC3). While this observation warrants cautious interpretation, it may hold clinical relevance. Hormonal dysregulation, common in breast cancer due to both disease and endocrine therapy, may increase susceptibility to psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and fatigue [

28,

29]. Further research is needed to clarify this potential relationship.

We also identified meaningful symptom patterns according to metastatic sites. Liver metastases were significantly associated with the visceral discomfort cluster (SCKMC2), comprising nausea, loss of appetite, and dyspnea, with a borderline association observed for the gastrointestinal cluster (SCPCA3). These results align with existing literature indicating that hepatic involvement often contributes to cancer cachexia, metabolic dysfunction, anorexia, and fatigue, even before overt liver failure develops [

30,

31,

32]. Conversely, a trend between bone metastases and the pain-specific cluster (SCPCA4), though not statistically significant, remains clinically intuitive, reflecting the well-established pathophysiology of skeletal metastases—osteolysis, nerve compression, and inflammatory mediator release [

33]. These findings underscore how SCs may reflect underlying tumor biology and metastatic burden. Larger prospective studies are warranted to validate these associations.

Our findings also highlighted a potential role for SCs in influencing treatment decisions. In multivariable analysis, patients belonging to psychological clusters (i.e., SCPCA2 and SCKMC3) had a significantly lower likelihood of receiving PRT. These consistent findings across two clustering methods suggest that psychological distress may act as a negative predictor of treatment referral in patients perceived as more vulnerable, or patient hesitancy or refusal related to emotional burden, low motivation, or treatment fatigue. Conversely, SCKMC1, (physical burden cluster) characterized by tiredness, drowsiness, pain, and malaise was positively associated with the likelihood of receiving PRT. This association is likely reflective of the clinical intent to address substantial symptom burden through localized treatment, particularly when pain is present and PRT is expected to provide rapid palliation. Interestingly, SCPCA1, which shares a similar symptom composition but emerged from PCA, was not significantly associated with treatment, possibly due to differences in clustering methodology or relative symptom weighting. Taken together, these results suggest that SCs may not only reflect the patient’s current symptom burden, but also influence clinical decision-making, potentially acting as adjunctive tools to traditional prognostic factors.

When comparing our results with previous studies exploring SCs in patients referred for PRT using ESAS scores, a number of consistent patterns emerge despite methodological differences. Several authors, including Chen et al.[

34], Ganesh et al.[

35] and McKenzie et al.[

36], have applied various statistical techniques (PCA, EFA, HCA), consistently identifying symptom pairs such as anxiety and depression, nausea and loss of appetite, and tiredness and drowsiness as strongly interrelated. These recurring associations align closely with our findings, suggesting that some symptom constellations may reflect stable and reproducible clinical phenomena rather than statistical artifacts.

Interestingly, while certain symptoms—such as nausea and loss of appetite or anxiety and depression—cluster together consistently across studies, others like pain, dyspnea, and malaise demonstrate greater variability depending on the population studied or the analytical method employed. Consequently, it is essential to note that the derivation of SC from principal component analysis should be guided by clinical reasoning, taking into account the pathophysiological and experiential interrelationships among symptoms. For symptom cluster analysis to be clinically meaningful, it must not only reflect consistent statistical associations but also provide practical utility in shaping care pathways and improving patient outcomes.

Our exploratory survival analysis showed that patients within SCKMC2 (i.e., visceral discomfort cluster) had a median OS of 3.2 months, compared to 4.6 months in those not belonging to this SC. Although, given the observational nature of the study and the relatively small sample size of the SCKMC2 belonging group, the statistical significance was not tested, the observed trend is clinically noteworthy. SCKMC2 includes loss of appetite and dyspnea—the only two clinical symptoms explicitly represented within the PaP prognostic score, a validated tool for estimating short-term survival in advanced cancer patients [

37,

38]. The ProPaRT study further confirmed the prognostic value of these symptoms in patients selected for PRT [

39]. The alignment between SCKMC2 and this high-risk symptom profile lends biological plausibility to the observed survival trend, suggesting that symptom clustering could serve as a proxy for latent prognostic trajectories. Given the limited sample size and statistical power, this hypothesis warrants investigation in larger, prospective datasets.

This study has some limitations. Its cross-sectional design prevents assessment of symptom evolution over time or changes in SCs following PRT. Additionally, being a single-center study, the findings may not be generalizable to broader populations or different healthcare systems. While PCA and KMC are robust exploratory methods, cluster interpretation partially depends on clinical reasoning, and the absence of validation in an independent cohort limits the reproducibility of our cluster solution. Finally, although exploratory survival analysis was performed, the limited sample size and number of events precluded a statistically rigorous survival analysis, reducing the power to draw definitive prognostic conclusions.

Nevertheless, this study has several strengths. The dual use of PCA and k-means clustering strengthens the internal consistency and robustness of the identified SCs. The selection of a well-characterized patient population enhances the reliability of our findings. Importantly, our SCs demonstrate biological plausibility and mirror previously reported symptom patterns, reinforcing their clinical relevance.

In conclusion, we identified clinically meaningful SCs in patients referred for PRT using both PCA and k-means clustering, revealing consistent psychological, gastrointestinal, and physical burden patterns. SCs dominated by physical symptoms were associated with poorer ECOG PS and a higher likelihood of receiving PRT, while psychological clusters were linked to lower treatment rates. A SC characterized by dyspnea and appetite loss was also associated with shorter OS, underscoring its potential prognostic value. These findings suggest that SC analysis may enhance clinical assessment and support more personalized, timely, and appropriate care in PRT settings. Prospective validation is warranted.