1. Introduction

Pesticides play a vital role in enhancing agricultural productivity to meet the food demands of a growing global population by protecting crops from pests, weeds, and diseases, they contribute significantly to the sustainability of food supply systems for both humans and animals. However, the intensive and often indiscriminate application of pesticides in modern agriculture has raised serious concerns regarding their environmental and human health impacts [

1,

2]. Among these concerns, soil contamination stands out as a critical issue, given that soil serves as the primary sink of pesticide residues following agricultural application.

Persistent pesticide residues in soil can negatively affect the native microbial communities, which are fundamental to nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and maintaining soil health. Disruption of these microbial communities may interfere with elemental cycles such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon and the bioaccumulation of toxic substances in food chains. Moreover, the horizontal and vertical mobility of certain pesticide compounds in soil profiles, increasing the risk of surface and groundwater contamination [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Given the environmental and health risks associated with the accumulation of pesticide residues in soil, food, and water systems, there is an urgent need to develop effective, safe, and economically viable methods for pesticide remediation. Among these, biodegradation, using soil microorganisms to break down and detoxify organic pollutants, has emerged as one of the most promising strategies [

7,

8]. Microbial degradation is a natural, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly approach that leverages the metabolic capabilities of native or introduced microbes to transform hazardous pesticide residues into non-toxic compounds.

The efficiency of pesticide biodegradation in soil is influenced by a range of factors, including the physicochemical properties of the pesticide (e.g., solubility, concentration, chemical structure), soil characteristics (e.g., texture, pH, temperature, moisture, organic matter content, salinity), and the presence and activity of microbial populations capable of degrading the compounds [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Additionally, soil amendments such as organic (e.g., crop residues) and inorganic (e.g., NPK) fertilizers can significantly enhance microbial activity by providing essential nutrients, thereby stimulating the production of enzymes involved in herbicide degradation [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Understanding the effect of these abiotic factors is essential for developing effective soil management practices and aimed at minimizing the environmental footprint of agrochemical. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the role of soil microorganisms in reducing the half-life of the herbicide atrazine under varying conditions, including the application of organic and inorganic fertilizers, across different soil types and temperature regimes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Soil samples were collected from Al Geraif (Blue Nile bank) area East Khartoum, Sudan where there is no history of pesticide application. Samples were randomly taken with an auger from the top 15cm from different parts in the selected site. Large clods were crushed to a uniform size, mixed thoroughly to make a composite sample and air dried at room temperature. The chemical and physical characteristics of the Al Geraif soil were as follows: pH = 7.8; ECe = 0.69; N = 0.18%; P as P2O5= 0.0034%; K as K2O = 0.03%; Clay = 52.0%; Silt =47.3%; Sand % =0.7%; organic matter = 0.62%. Soils were then divided into five 600g lots and transferred into 1000 ml beaker. Five sets of atrazine concentrations of 0.0, 0.0678, 1.69, 3.39 or 5.08 (mg g-1 soil), each for two fertilizers additives and control set were prepared and mixed thoroughly.

The inorganic NPK were added in the urea, P

2O

5, and KCL at rate 375, 187.5 and 187.5 mg per 600g of atrazine-amended soils respectively. Maize straw was added at a rate of 12 g / 600g of atrazine-amended soils. Soils were then wetted with water to 60 % of field capacity mixed thoroughly and incubated in the dark (at 28

0C) for 150 days. At zero time and then after 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 days, soil samples were taken for determination of atrazine residue. Atrazine residues was determined according to the method described in [

19].

To study the effect of soil type on the half-life of Herbicide atrazine similar experiment (Control without addition fertilizers) was repeated using Shambat Gerif (River Nile Bank), north of Khartoum, Sudan. The chemical and physical characteristics of the Gerif soil were as follows: pH = 7.3; ECe = 0.58; N = 0.11%; P as P2O5= 0.43%; K as K2O = 0.13%; Clay = 31.7%; Silt =53.6%; Sand % =14.7%; total organic carbon = 0.36%; organic matter = 0.31(%).

Determination of atrazine half –life in soil

Residues of atrazine in soil after 150 days incubation were used to calculate the half-life of the herbicides using the following equation suggested by Mulier

et al., (2006):

Where:

T½ = the half - life.

K= the degradation rate constant.

The degradation rate constant can be calculated with the following equation:

Where:

C0 =the initial concentration (ppm)

Ct = concentration at time t (ppm).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistica software. A one-way ANOVA was performed separately for each soil treatment to evaluate the effect of atrazine concentrations (0.678–5.80 mg g⁻¹ soil). When significant differences were found (p < 0.05), Tukey’s HSD test was applied, and means were labeled with different letters to indicate statistically significant differences between concentration levels.

3. Results

3.1. Factors Affecting Atrazine Persistence in Soil: Influence of Temperature, Fertilization, and Soil Type

Atrazine degradation in soil was affected by temperature, fertilization, and soil type. The half-life of atrazine was higher at lower temperatures compared to higher temperatures. For instance, in non-fertilized Algeraif soils incubated at 28 ºC, the half-life ranged from 90 to 39 days, whereas at 40 ºC it decreased significantly, ranging between 36 and 25 days. Fertilization also had a strong influence on atrazine persistence. In Algeraif soils incubated at 28 ºC, the half-life ranged from 90 to 39 days in non-fertilized soils, but it decreased to 19–25 days in soils amended with NPK and to 14–22 days in soils amended with plant residue. Moreover, soil type played a significant role in the persistence of atrazine. The half-life in Algeraif soil ranged from 39 to 90 days, while in Gerif soil it was longer, ranging between 70 and 125 days. These results indicate that higher temperatures, fertilization, and soil characteristics significantly accelerate the degradation of atrazine in soil (

Table 1).

3.2. Effect of Initial Atrazine Concentration on Degradation Rate

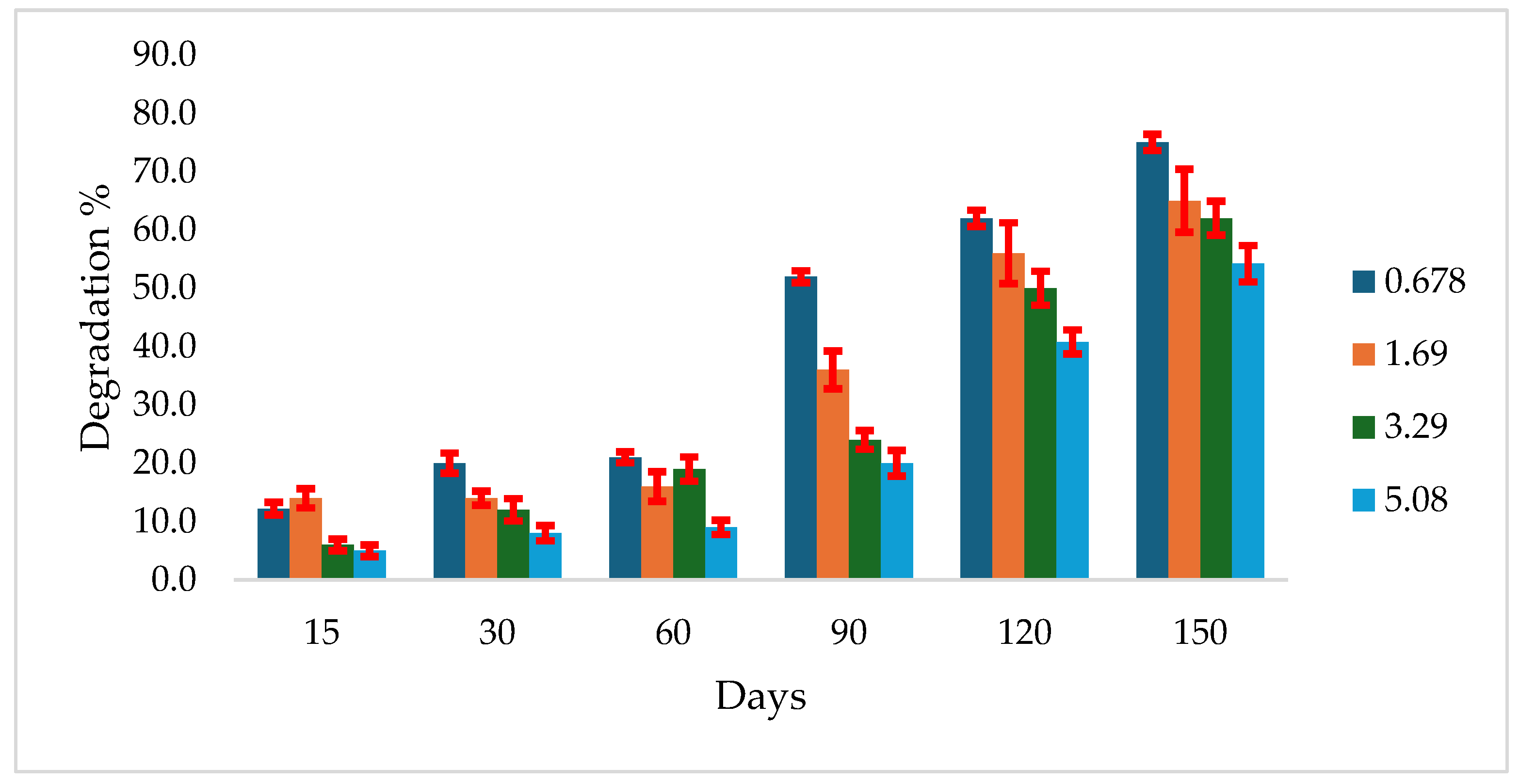

The study revealed that the degradation rates of atrazine were inversely proportional to its initial concentrations. In Gerif soil, degradation of all atrazine concentrations started early during the incubation period. However, only 5% degradation was recorded for the maximum concentration after 15 days, increasing to 54.2% after 150 days. At the same time intervals, degradation for the minimum concentration was 12.2% and 7%, respectively (

Figure 1).

3.3. Atrazine Degradation in Algeraif Soil at 28 ºC

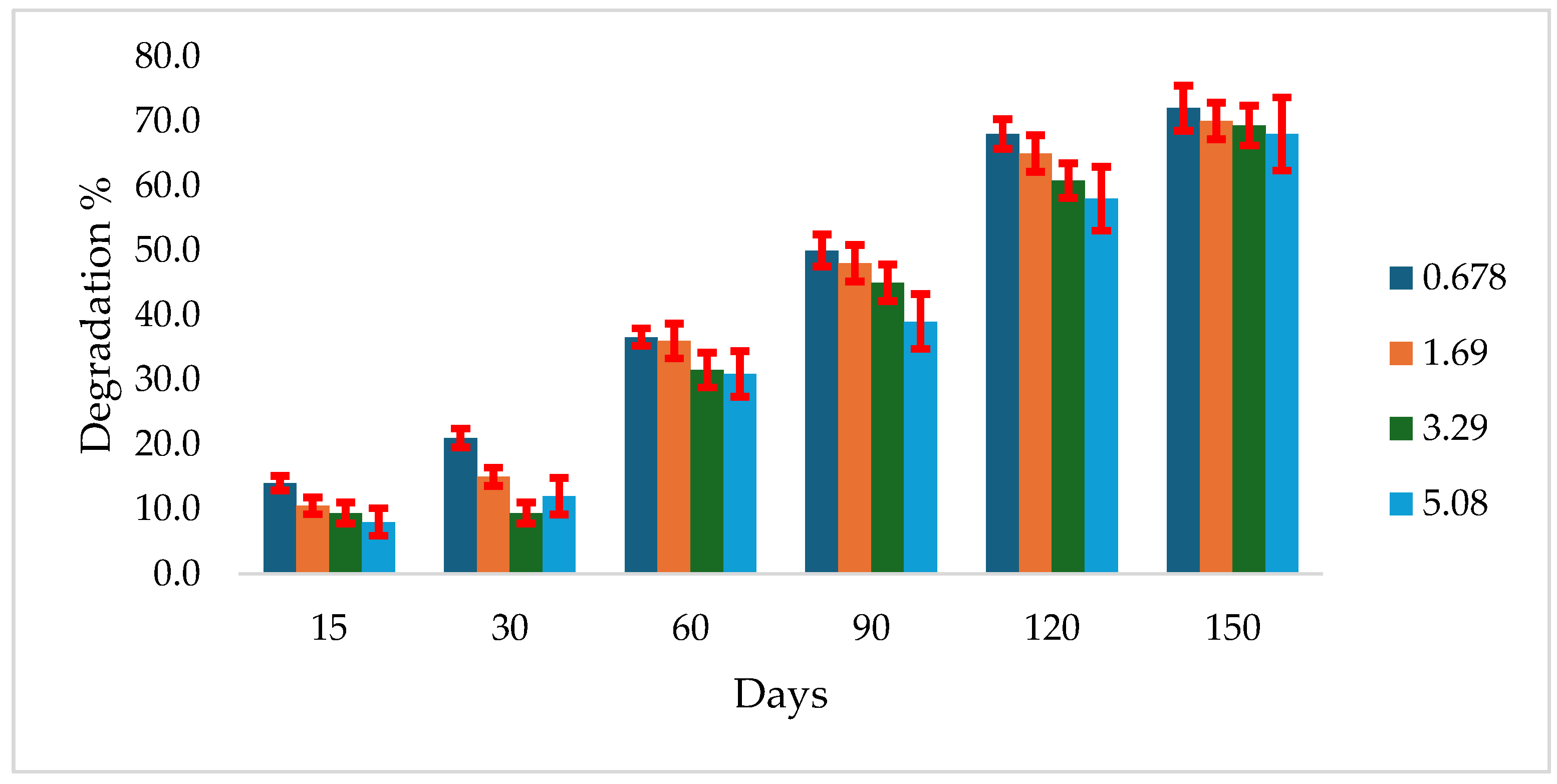

In Algeraif soil incubated at 28 ºC, atrazine degradation was generally low at all tested concentrations. After 15 days of incubation, the degradation percentages were 8%, 9.4%, 10.4%, and 14% for concentrations of 5.08, 3.39, 1.69, and 0.0678 mg g⁻¹ soil, respectively. By 150 days, the degradation had increased to 72.0%, 70.0%, 69.3%, and 68% for the same respective concentrations

(Figure 2).

3.4. Atrazine Degradation in Algeraif Soil at 40 ºC

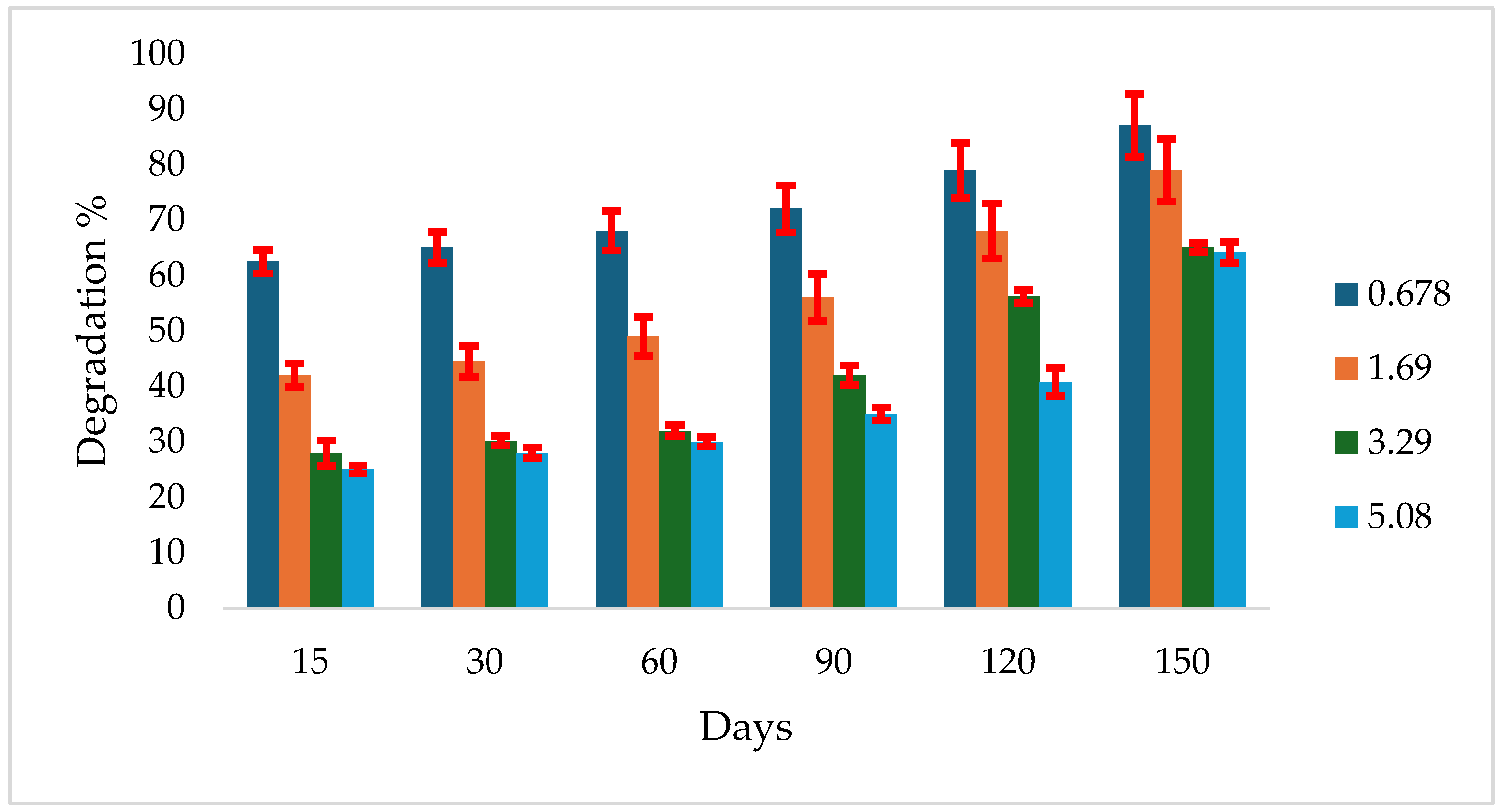

In Algeraif soil incubated at 40 ºC, degradation started earlier for the lower concentrations. After 15 days, 62.5% degradation was recorded at 1.69 mg g⁻¹ soil, while 28% and 42% were degraded at 0.0678 and 3.39 mg g⁻¹ soil, respectively. After 150 days, a degradation range of 55.2% to 87.0% was observed across all concentrations (

Figure 3).

3.5. Effect of NPK and Plant Residue on Atrazine Degradation

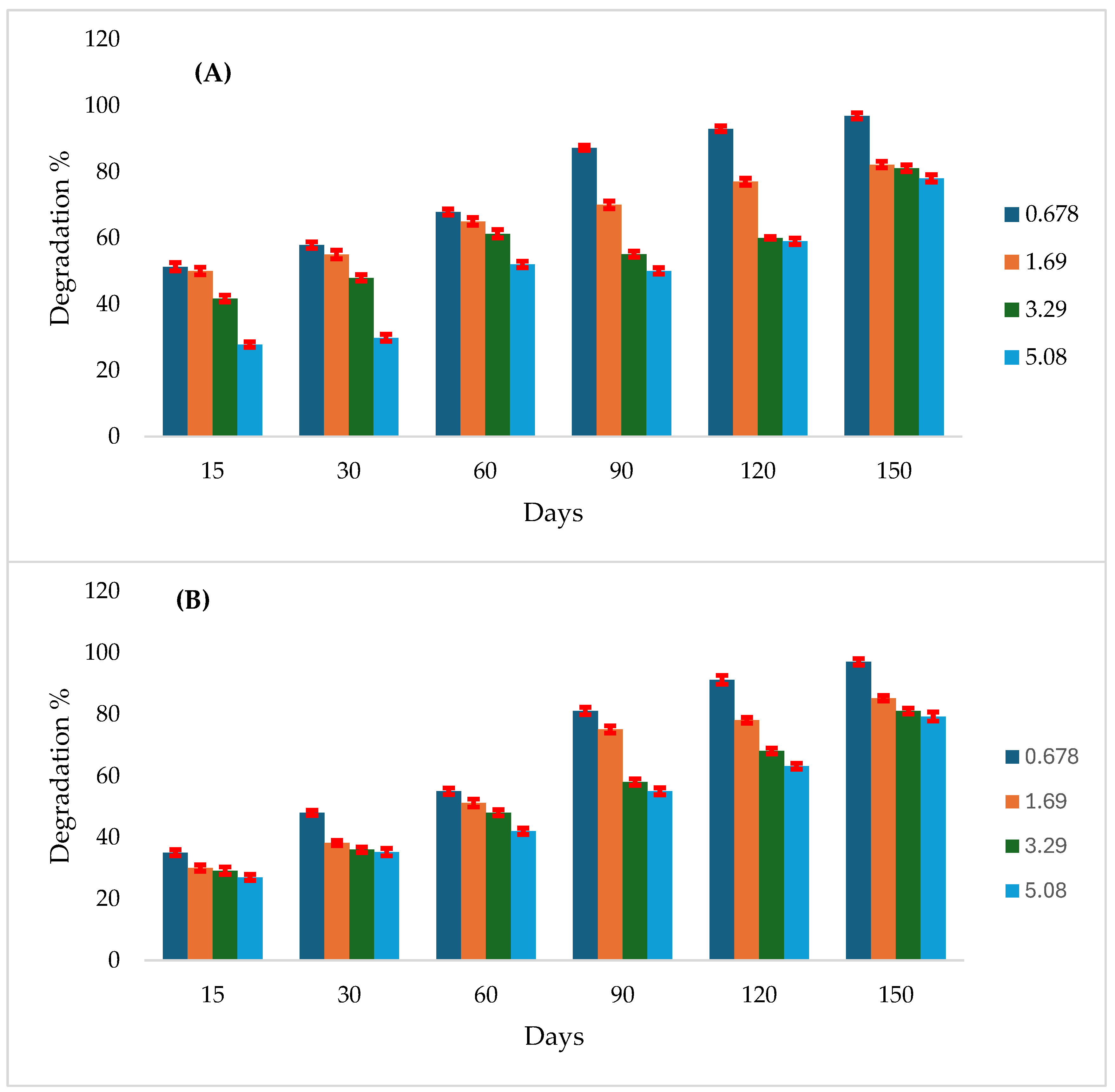

Soil amendments with NPK and plant residue significantly enhanced atrazine degradation compared to the control. At a concentration of 0.0678 mg g⁻¹ soil, 79% degradation was recorded at 120 days with NPK addition, while 91% degradation occurred earlier in plant residue–amended soils. At 1.69 mg g⁻¹ soil, NPK induced 82% degradation at 150 days, while plant residue led to faster degradation. At 3.39 mg g⁻¹ soil, NPK resulted in 60% degradation at 120 days, again occurring earlier with plant residue. At the highest concentration (5.08 mg g⁻¹), both NPK and plant residue fertilizers promoted intensive degradation as early as 30 days. The maximum degradation recorded was 97% at 150 days for both NPK and plant residue amendments (

Figure 4A and B).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the half - life of atrazine was longer at low temperature compared to higher temperature. Temperature is a key climatic factor, and the increased temperature significantly increased both the biological metabolic processes and the rate of chemical reactions. In this context, [

20,

21] stated that a rise of 10°C in temperature decreased apparent half-life of pesticides by a factor of 2-3 times. Elevated temperatures not only accelerate the microbial growth but also enhance both biological and chemical processes involved in pesticide dissipation [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Rapid degradation of pesticides at a higher level of temperatures may also result from increased volatility and photodecomposition of the molecules. These findings align with those of [

26] who observed that the fungicide azoxystrobin degraded slowly and persisted in the soil for up to five months under incubation. He also reported that the biodegradation rate of the fungicide Amistar in soil incubated at 40º C was higher than in soil incubated at 18ºC. Moreover, [

27] indicated that biodegradation of oxyfluorfen in soil incubated at 40ºC after 45 days of incubation ranged from (55.2-78.3%) than in soil incubated at 28ºC (17.5-36.6). [

28,

29] reported that half- life Benomyl–MBC was found to decrease with increased temperature from 23 to 33ºC. Working on oxyfluorfen [

30,

31] reported lower half- life values, at higher temperature.

The data further revealed that the application of organic and inorganic fertilizers enhanced early degradation of atrazine and reduced half-life of this herbicide. Organic fertilizers, especially those derived from plant resides enhanced degradation and improve soil fertility. This could possibly be due to the available carbon in organic material, which is important for the pesticide-degrading microorganisms as sources of nutrients, carbon and energy [

32,

33,

34].

Generally, mineral fertilization of arable land positively affects and increases the biological productivity of various ecosystems as well as the microbial activity in soil [

35,

36,

37,

38]. The study found that the half-life of atrazine was shorter in Algeraif soil compared to Gerif soil. This could be attributed to the higher clay content,organic matter and other nutrient content [

27,

39,

40]. This is because organic materials enhance microbial growth and activities [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Additionally, clayey soils generally exhibit greater adsorption capacity than light (sandy) soils [

45,

46,

47].

Finally, the results indicated that degradation rates of atrazine were inversely proportional to concentrations. [

48,

49,

50] reported similar findings, concluding that the degradation of Thiram fungicide in soil is inversely proportional to its concentration. One of the crucial factors affecting pesticide degradation is the soil’s organic matter content of soil, which increases the biomass of the active microbial population and the degradation as well [

46,

51,

52].

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the pivotal role of some abiotic factors studied in this experiment namely; NPK fertilization, soil type, temperature and residue in reducing the half-life of atrazine and promoting its degradation across different soil types. Results demonstrate that higher temperatures and the application of maize straw or NPK fertilizers significantly accelerated atrazine degradation, underscoring the synergistic influence of biological and environmental factors in mitigating pesticide persistence. Additionally, soil composition played a vital role, with Algeraif soil’s higher clay and organic matter content leading to shorter atrazine half-lives compared to Gerif soil. These findings emphasize the importance of implementing tailored soil management strategies to optimize degradation and reduce environmental contamination. Based on these findings future research is recommended to focus on: (1) Long-term field studies to validate laboratory findings under natural conditions. (2) The impact of diverse microbial communities and their specific roles in pesticide degradation. (3) The interaction of additional organic amendments with soil microorganisms in various climates and soil types. (4) The broader ecological effects of enhanced atrazine degradation, particularly on non-target organisms and nutrient cycling. Such research will contribute to the development of more sustainable agricultural practices and help mitigate the environmental risks associated with pesticide use.

Author Contributions

A.K.A.E.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Emad H. E. Yasin: Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Kornel Czimber: Writing – Review & Editing. A.G.O, M. M. and A.M.Z: Supervision, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. E.A.E.E.: Supervision, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding from the Sudanese Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Soil and Environment Science, University of Khartoum, for lab support; the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for funding; and the Institute of Geomatics and Civil Engineering, University of Sopron, for academic collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOAC |

Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

References

- Abdulrahman, N.M.; Hamasalim, H.J.; Mohammed, H.N.; Arkwazee, H.A. Effects of pesticide residues in animal by-products relating to public health. J. Appl. Vet. Sci. 2023, 8, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, A. Pesticide Pressure on Insect and Human Population: A Review. Arch. Curr. Res. Int. 2024, 24, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Qiao, C.L. Novel approaches for remediation of pesticide pollutants. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 18, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudh, S.; Singh, J.S. Pesticide contamination: environmental problems and remediation strategies. In Emerging and Eco-Friendly Approaches for Waste Management; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.M.; Verma, V.K.; Rawat, B.S.; Kaur, B.; Babu, N.; Sharma, A.; Dewali, S.; Yadav, M.; Kumari, R.; Singh, S.; Mohapatra, A. Current status of pesticide effects on environment, human health and its eco-friendly management as bioremediation: A comprehensive review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 962619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leskovac, A.; Petrović, S. Pesticide use and degradation strategies: Food safety, challenges and perspectives. Foods 2023, 12, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoefs, O.; Perrier, M.; Samson, R. Estimation of contaminant depletion in unsaturated soils using a reduced-order biodegradation model and carbon dioxide measurement. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 64, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Meng, F. Efficiency, mechanism, influencing factors, and integrated technology of biodegradation for aromatic compounds by microalgae: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Pradhan, S.; Saha, M.; Sanyal, N. Impact of pesticides on soil microbiological parameters and possible bioremediation strategies. Indian J. Microbiol. 2008, 48, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, O.G.; Abdelbagi, A.O.; Elsheikh, E.A.E. Effects of fertilizers (activators) in enhancing microbial degradation of endosulfan in soil. Res. J. Environ. Toxicol. 2009, 3, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgholi, H.; Ahangar, A.G. Factors controlling degradation of pesticides in the soil environment: A review. Agric. Sci. Dev. 2014, 3, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bosu, S.; Rajamohan, N.; Al Salti, S.; Rajasimman, M.; Das, P. Biodegradation of chlorpyrifos pollution from contaminated environment-A review on operating variables and mechanism. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.S.; Parihar, K.; Goyal, N.; Mahapatra, D.M. Synergistic insights into pesticide persistence and microbial dynamics for bioremediation. Environ. Res. 2024, 119290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, C.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, A.; Walia, Y.; Kumar, R.; Umar, A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Akhtar, M.S.; Alkhanjaf, A.A.M.; Baskoutas, S. A review on ecology implications and pesticide degradation using nitrogen fixing bacteria under biotic and abiotic stress conditions. Chem. Ecol. 2023, 39, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanissery, R.G.; Sims, G.K. Biostimulation for the enhanced degradation of herbicides in soil. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2011, 2011, 843450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. The application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as microbial biostimulant, sustainable approaches in modern agriculture. Plants 2023, 12, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhlifi, Z.; Iftikhar, J.; Sarraf, M.; Ali, B.; Saleem, M.H.; Ibranshahib, I.; Bispo, M.D.; Meili, L.; Ercisli, S.; Torun Kayabasi, E.; Alemzadeh Ansari, N. Potential role of biochar on capturing soil nutrients, carbon sequestration and managing environmental challenges: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Khan, M.S.; Singh, U.B. Pesticide-tolerant microbial consortia: Potential candidates for remediation/clean-up of pesticide-contaminated agricultural soil. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.B.; Kulshrestha, G. Degradation of fluchloralin in soil under predominating anaerobic conditions. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 1995, 30, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W. Review on the Effects of Temperature on Toxicity of Insecticides. J. Hebei Agric. Sci. 2010. Available online: https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-HBKO201008005.htm.

- Lehmann, R.G.; Miller, J.R.; Fontaine, D.D.; Laskowski, D.A.; Hunter, J.H.; Cordes, R.C. Degradation of a sulfonamide herbicide as a function of soil sorption. Weed Res. 1992, 32, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedich, L.M.; Millican, M.D.; Koch, P.L. Temperature impacts on soil microbial communities and potential implications for the biodegradation of turfgrass pesticides. J. Environ. Qual. 2017, 46, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukhurebor, K.E.; Aigbe, U.O.; Onyancha, R.B.; Adetunji, C.O. Climate change and pesticides: their consequence on microorganisms. Microb. Rejuvenation Pollut. Environ. 2021, 3, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, M.M.; Reehana, N.; Imran, M.M. Microbial Degradation of Pesticides in Agricultural Environments: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms, Factors and Biodiversity. Mol. Sci. Appl. 2024, 4, 65–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.G. Degradation of the fungicide azoxystrobin by soil microorganisms. U. K. Agric. Sci. 2006, 14, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.T.; Elhussein, A.A.; Elsiddig, M.A.; Osman, A.G. Degradation of Oxyfluorfen herbicide by soil microorganisms biodegradation of herbicides. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Chang, H.H.; Jang, Y.S.; Hyung, S.W.; Chung, H.Y. Partial reduction of dinitroaniline herbicide pendimethalin by Bacillus sp. MS202. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2004, 23, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.H.; Gergon, E.B. Strategies for the management of rice pathogenic fungi. In Fungi; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 396–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.H.; Sheu, W.S.; Wang, Y.S. Dissipation of the herbicide oxyfluorfen in subtropical soils and its potential to contaminate groundwater. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2003, 54, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnar, D.J. The Fate and Risk of Oxyfluorfen Under Simulated California Rice Field Conditions; University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Duah-Yentumi, S.; Kuwatsuka, S. Effect of organic matter and chemical fertilizers on the degradation of benthiocarb and MCPA herbicides in the soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1980, 26, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, H.; Solanki, P.; Narayan, M.; Tewari, L.; Rai, J.P.N.; Khatoon, H.C. Role of microbes in organic carbon decomposition and maintenance of soil ecosystem. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2017, 5, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, T.; Kole, S.C. Soil organic matter and microbial role in plant productivity and soil fertility. In Advances in Soil Microbiology: Recent Trends and Future Prospects, Volume 2: Soil-Microbe-Plant Interaction; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabasz, W.; Albinska, D.; Jaskowska, M.; Lipiec, J. Biological effects of mineral nitrogen fertilization on soil microorganisms. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2002, 11, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen, W.; Banks, P. Soil movement and persistence of triazine herbicides. In The Triazine Herbicides: 50 Years Revolutionizing Agriculture; LeBaron, H., McFarland, J., Burnside, O., Eds.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D.; Scow, K.M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms-A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.C.; Grenni, P.; Onet, C.; Onet, A. Fertilization and soil microbial community: a review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, K.K. Sorption and degradation of imidacloprid in soil and water. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2006, 41, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudhoo, A.; Garg, V.K. Sorption, transport and transformation of atrazine in soils, minerals and composts: a review. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.C.; Debnath, A.; Mukherjee, D. Effect of the herbicides oxadiazon and oxyfluorfen on phosphates solubilizing microorganisms and their persistence in rice fields. Chemosphere 2003, 53, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, R.; Chakrabarti, K.; Chakraborty, A.; Chowdhury, A. Pencycuron application to soils: degradation and effect on microbiological parameters. Chemosphere 2005, 60, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Senbayram, M.; Blagodatsky, S.; Myachina, O.; Dittert, K.; Kuzyakov, Y. Decomposition of biogas residues in soil and their effects on microbial growth kinetics and enzyme activities. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 45, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Sánchez, A.; Soares, M.; Rousk, J. Testing the dependence of microbial growth and carbon use efficiency on nitrogen availability, pH, and organic matter quality. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 134, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, D.; Hennion, M.C. Trace Determination of Pesticides and Their Degradation Products in Water; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003; p. 539. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, S.; Rasool, T.; Gani, K.M. A review of interactions of pesticides within various interfaces of intrinsic and organic residue amended soil environment. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 11, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aswad, A.F.; Fouad, M.R.; Aly, M.I. Experimental and modeling study of the fate and behavior of thiobencarb in clay and sandy clay loam soils. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 4405–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkot, C.K.; Gupta, K.G. Accelerated tetramethylthiuram disulfide (TMTD) degradation in soil by incubation with TMT-utilizing bacteria. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1985, 35, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, A.M.; Elhussein, A.A.; Osman, A.G. Biodegradation of fungicide thiram (TMTD) in soil under laboratory conditions. Am. J. Biotechnol. Mol. Sci. 2011, 1, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Jose, S.; Fayaz, T.; Renuka, N.; Ratha, S.K.; Kumari, S.; Bux, F. Microbe-Assisted Bioremediation of Pesticides from Contaminated Habitats. In Bioremediation for Sustainable Environmental Cleanup; 2024; pp. 109. [CrossRef]

- Sandin-España, P.; Loureiro, I.; Escorial, C. Herbicides: Theory and Applications. In Soloneski, S.; Larramendy, M.L., Eds.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2011; p. 610.

- Arora, S.; Arora, S.; Sahni, D.; Sehgal, M.; Srivastava, D.S.; Singh, A. Pesticides use and its effect on soil bacteria and fungal populations, microbial biomass carbon and enzymatic activity. Curr. Sci. 2019, 116, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).