1. Introduction

Recent advances in medicine, including integrating artificial intelligence and large-scale epidemiologic data into clinical practice, has underscored the crucial role of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) in shaping health outcomes. The World Health Organization has emphasized the importance of SDOH since 2008, providing an operational framework in 2024. Factors such as socioeconomic status, education, occupation, and social isolation have been increasingly recognized as central to disease management and prognosis [

1].

Professor Rachel Rowe of the School of Population Health, Australia, published an article on the Social Determinants of Health in the journal

Big Data & Society, in which she stated: “In recent years, the claim that around 80 percent of contemporary health issues are attributable to social factors has become a mantra at digital health technology conferences” [

2].

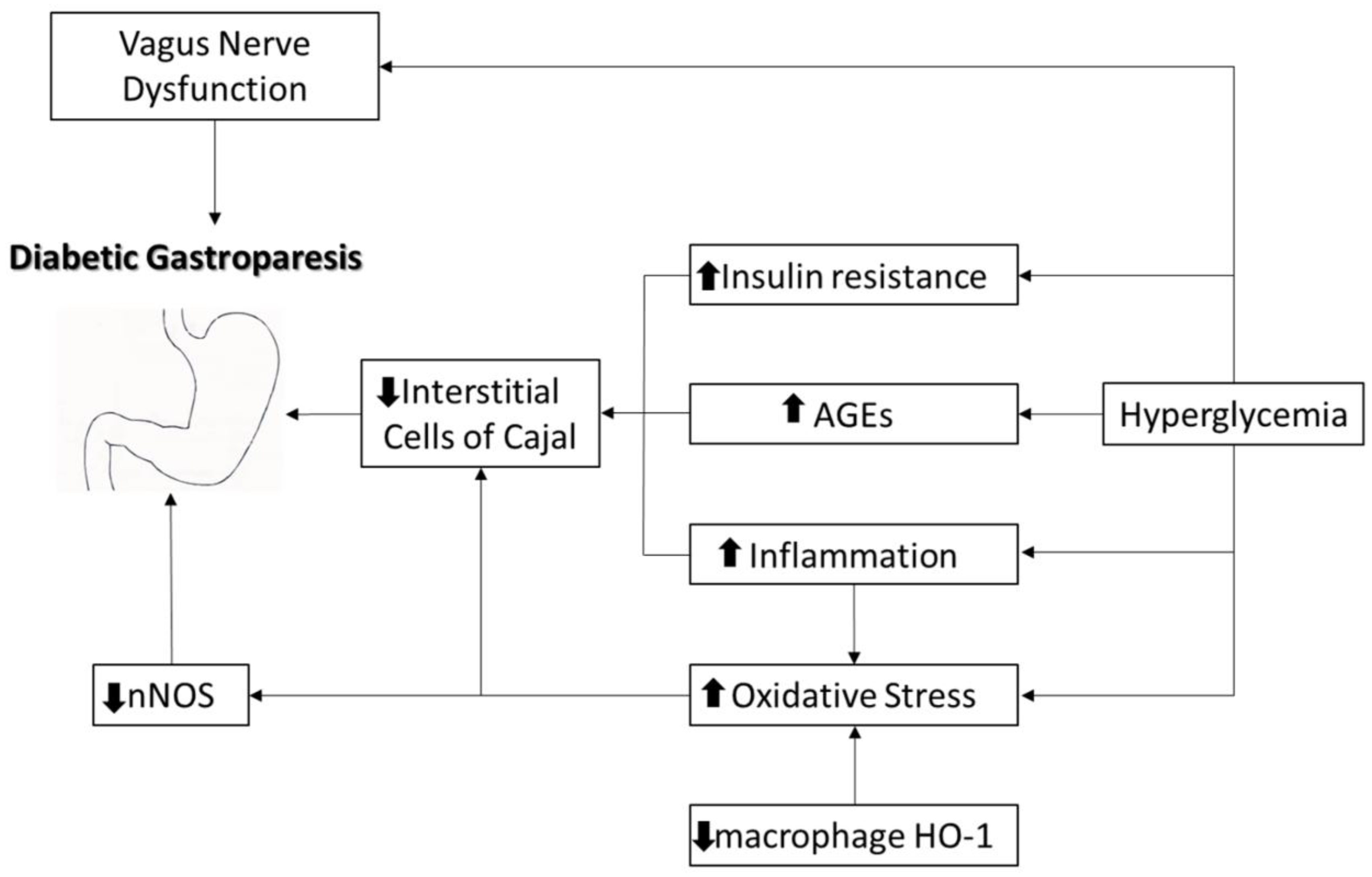

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common condition associated with gastroparesis [

3]. Diabetic gastroparesis is a chronic complication of long-standing and poorly controlled diabetes, often associated with autonomic neuropathy, smooth muscle cell dysfunction, and damage caused by the reduction in interstitial peacemaker Cajal cells [

4,

5,

6], at the level of the myenteric plexus, and through the appearance of fibrosis [

7,

8,

9]. It is characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction and results in significant morbidity [

2,

4,

10]. A recent alternative theory highlighted the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic gastroparesis [

11,

12] through increasing the number of macrophages and amplifying heme oxygenase-1 (HO1), while causing a selective decrease in protective CD 206-positive macrophages [

13] (

Figure 1).

Acute hyperglycemia (glycemia values above 200 mg/dl) contributes to delayed gastric emptying, which is often reversible upon glycemic normalization, influencing the gastric electrical activity [

15] by relaxing and increasing the sensitivity of the proximal stomach and suppressing antral and pyloric contractions. On the other hand, in the presence of chronic hyperglycemia, gastroparesis does not improve, even with glycemic control [

16,

17,

18]. Hypoglycemia tends to accelerate gastric emptying in patients with gastroparesis [

19].

Despite its clinical importance, it remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

This study investigates the intersection between diabetic gastroparesis and SDOH, with a focus on poverty, education, and social isolation, aiming to elucidate their impact on the disease burden, symptomatology, and healthcare utilization.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A retrospective observational study was conducted using medical records from the archives of the medical departments of a Bucharest hospital over a one-year period, between February 2019 and February 2020. From a total of 250 patients diagnosed with gastroparesis, we selected 50 patients with scintigraphy-confirmed diabetic gastroparesis.

2.2. Data Collection

All patients provided informed consent. Data were systematically recorded using a structured form developed using the software EpiInfo (distributed freely by the WHO). The inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and confirmation of gastroparesis via gastric emptying scintigraphy. The exclusion criteria included evidence of mechanical gastric outlet obstruction or concurrent malignancies.

The variables analyzed included demographics (age, sex, residence), clinical results (obesity, glycemic control, comorbidities, alcohol and tobacco use, endoscopy results), and social determinants (income level, employment status, self-reported loneliness).

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and all procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the patient characteristics. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as counts and percentages. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported where applicable. Missing data were minimal (<5%) and were addressed using listwise deletion. Analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel and validated using Epi Info v7.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile

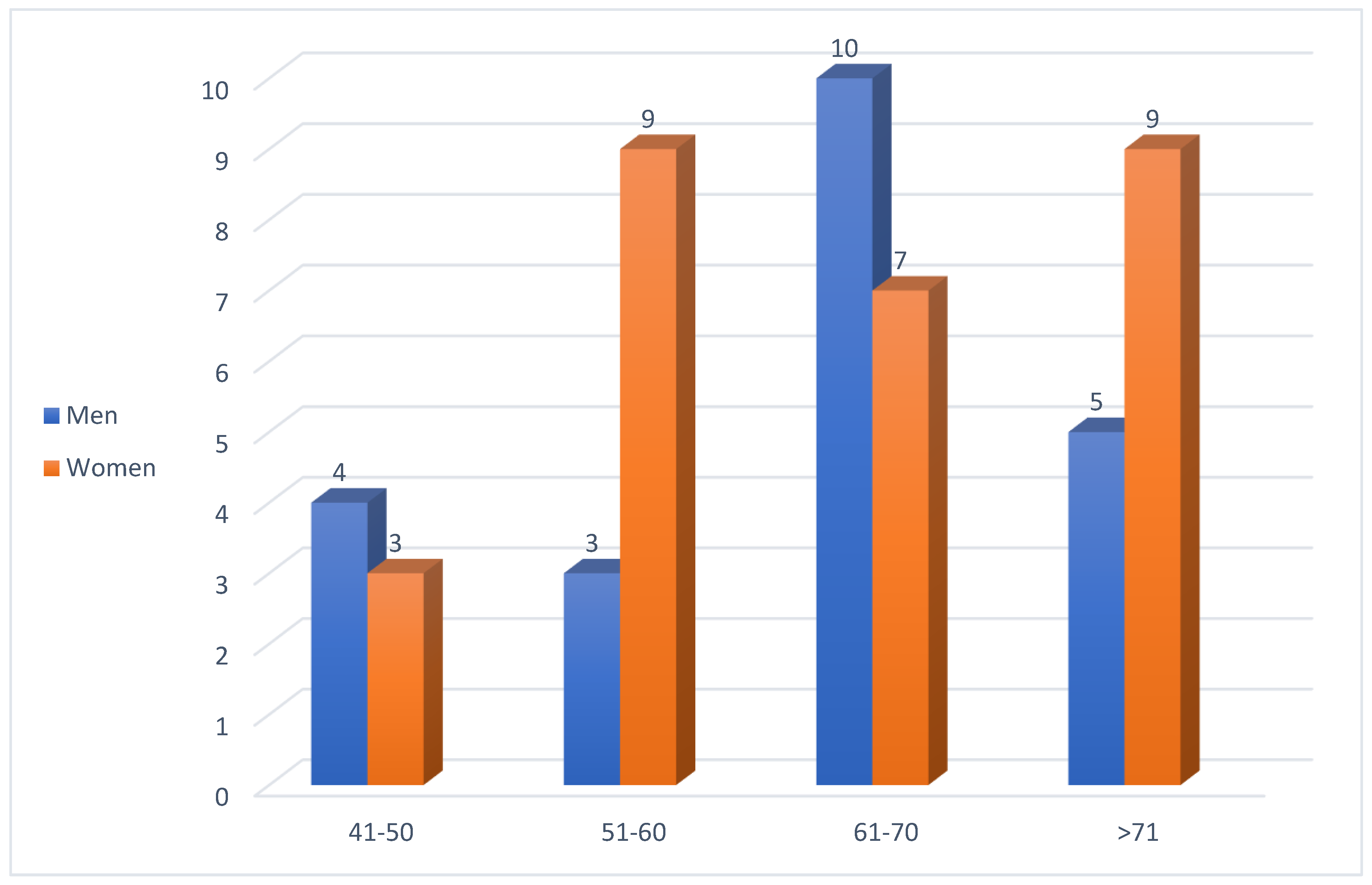

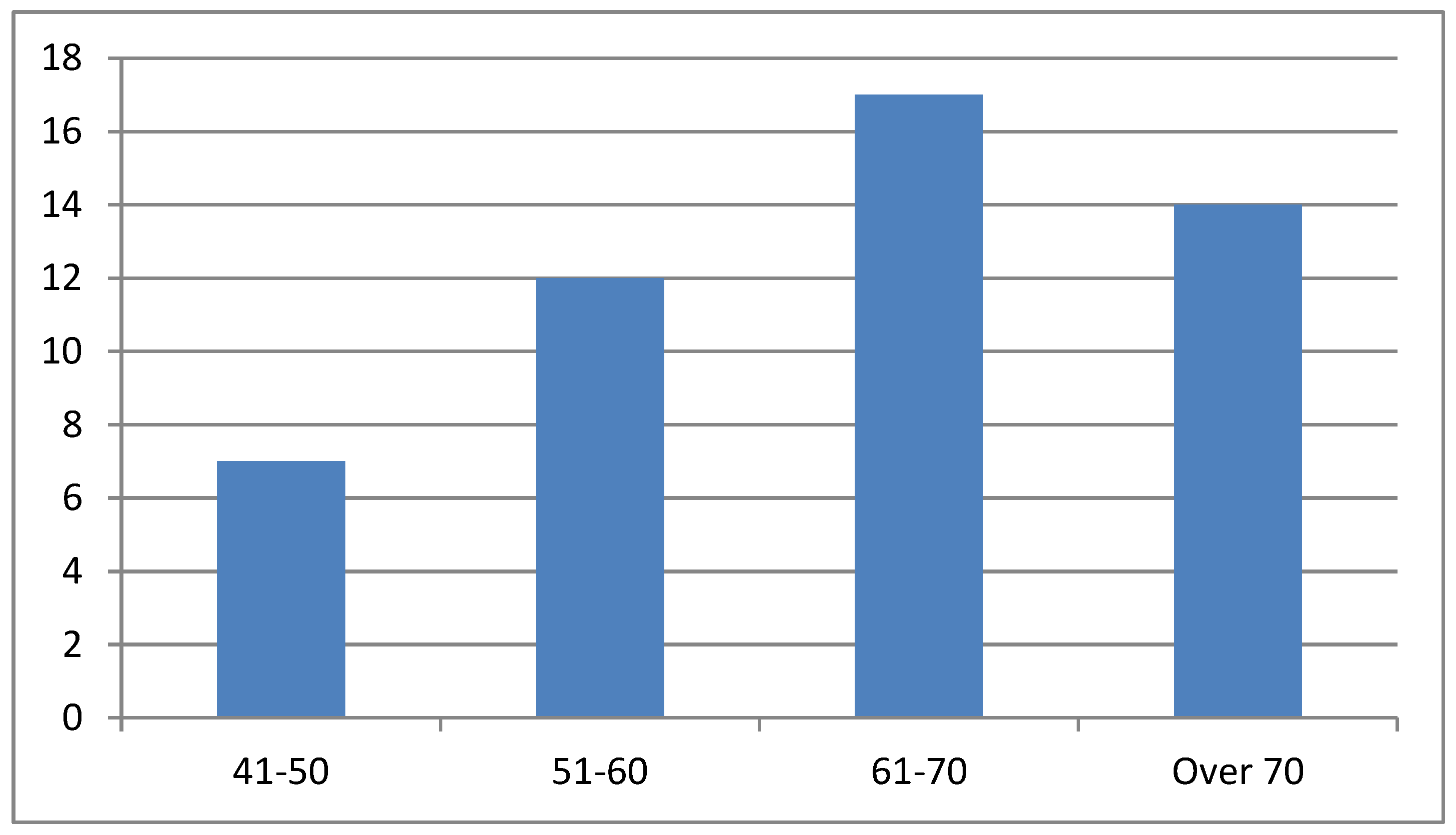

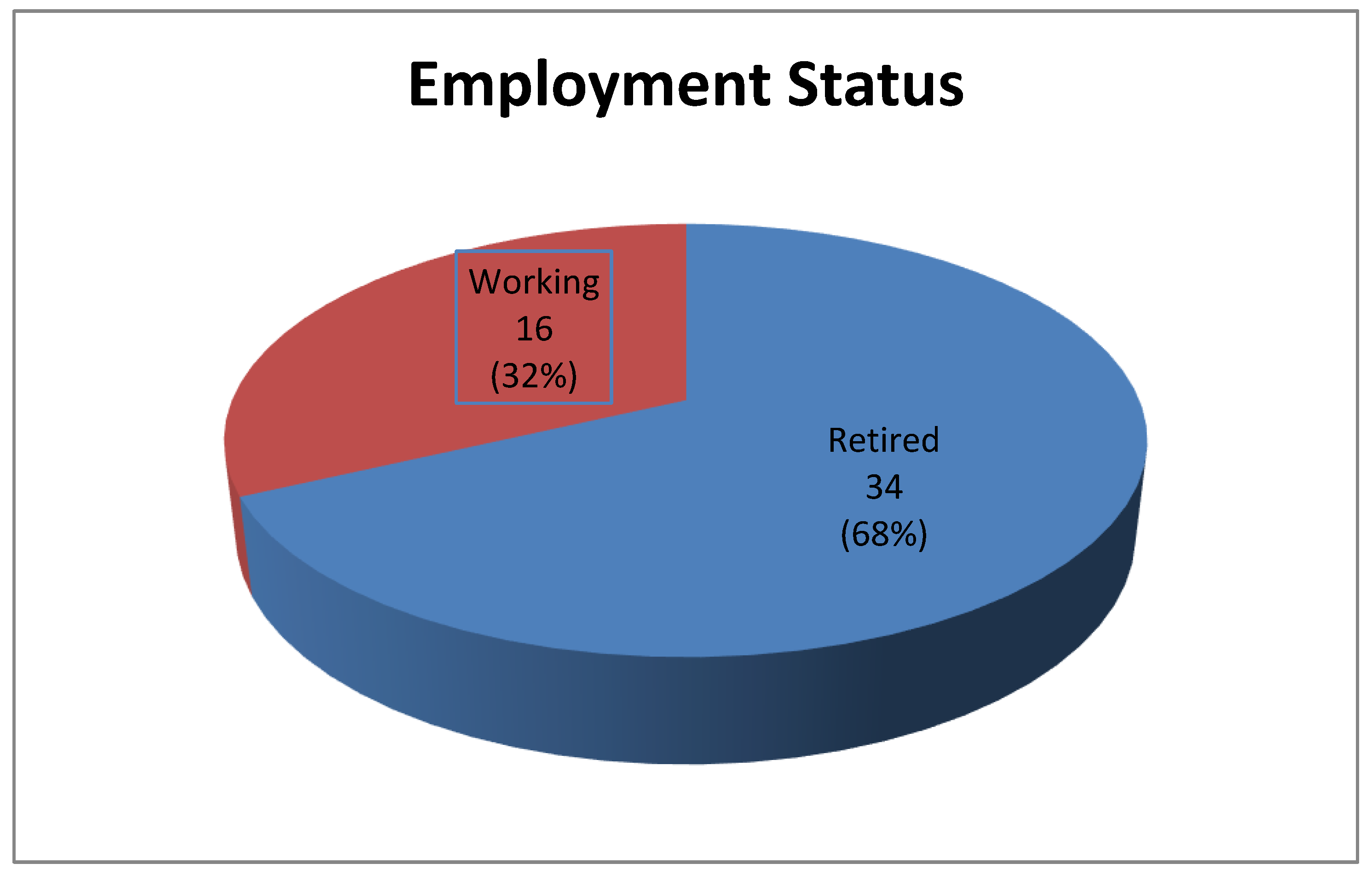

Among the 50 patients with diabetic gastroparesis, the majority were women (56%) (

Figure 2), and the patient ages ranged between 61 and 70 years (

Figure 3). A significant majority (68%) were retired, with 32% still employed (

Figure 4).

3.2. Social and Lifestyle Factors

In total, 50% of patients were classified as obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m²), and obesity was more prevalent among women. Chronic alcohol consumption was twice as common among males (32%) than females (12%), while cigarette use was similar across genders (males 28%, females 25%). Loneliness was frequently reported, particularly in older rural women. A notable proportion of patients reported social isolation, which correlated with suboptimal self-care, poor glycemic control, and frequent hospital admissions (

Table 1).

3.3. Endoscopic Findings

Ninety-two percent of patients underwent upper digestive endoscopy. The most common findings were as follows:

Diffuse non-specific gastric mucosal changes;

Erosive and erythematous lesions;

Hypertrophic mucosal changes.

3.4. Clinical Presentation and Impact of Income on the Symptoms

The most frequently reported symptoms were epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal bloating, and altered intestinal transit. Less common symptoms included bowel irregularities, early satiety, and weight loss. Notably, the symptoms were often mild and non-specific, contributing to delayed diagnosis and management challenges.

Patients with low income (n = 36) had higher rates of all symptoms—epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting—but none reached statistical significance (

Table 2).

3.5. Comparison by Place of Residence

The socioeconomic analysis indicated that 78% of patients had low income, correlating significantly with increased hospitalization rates (p < 0.05). Rural residence was associated with higher rates of obesity (p = 0.03) and poorer glycemic control (mean HbA1c 8.5% vs. 7.3% in urban patients, p = 0.01). Rural patients had a higher mean age (66.2 ± 5.8 vs. 63.5 ± 6.1 years; p = 0.12); however, this was not statistically significant (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Diabetic gastroparesis is a chronic condition characterized by delayed gastric emptying, which is often overshadowed by more prominent complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular disease. However, it significantly impairs the quality of life and complicates glycemic control, creating a vicious cycle.

Diagnosis begins by ruling out mechanical obstruction by performing an upper endoscopy, enteroCT, or magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) [

4] and confirming delayed gastric emptying by scintigraphy, which remains the gold standard for diagnosis, but it is underutilized in routine practice [

20]. Delayed diagnosis is common due to the non-specific nature of the symptoms and a general underappreciation of gastric complications in diabetes care.

The management strategies include optimizing glycemic control [

21], dietary adjustments (reducing the intake of products rich in fats and spices [

22,

23] and increasing the amount of fiber), adequate hydration [

24], and lifestyle changes (avoidance of alcohol, tobacco, and carbonated beverages) that decrease antral contractility and delay gastric emptying [

25,

26].

Other stages of gastroparesis management involve pharmacological therapy such as antiemetics and prokinetic agents and surgical methods in the case of severe forms (gastroparesis with gastric failure) with persistent symptoms [

27].

In our cohort, most patients were older, obese, and low-income women from rural areas. These findings align with the international literature, which associates diabetic gastroparesis with socioeconomic vulnerability, poor diet, and limited access to medical care. The prevalence of gastric mucosal lesions supports the hypothesis that prolonged gastric stasis aggravates mucosal damage, often masked by mild symptoms.

Recent specialist articles revealed that gastroparesis affects approximately 18% of diabetes patients. Its incidence is estimated at approximately 5% in type 1 and 1% in type 2 diabetes [

3]. Although there is an association between gastroparesis and type 1 diabetes, it is frequently observed in type 2 diabetes due to incretin mimetics (glucagon-like peptides administered to patients with type 2 diabetes), which increase the risk of developing gastroparesis [

28]. A higher prevalence has been noted in urban environments [

29], in those who have been diagnosed with diabetes for at least 10 years, and in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes who have comorbidities [

4]. The risk factors for diabetic gastroparesis include microangiopathic complications, obesity, female gender [

30], and associated psychiatric conditions. In Sweden, a study of 217,000 patients carried out over 7 years evaluated several social factors, including education, income, occupation, and loneliness, in terms of their ability to influence the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes; diabetic gastroparesis was more frequently associated with females, especially obese female patients.

In a cross-sectional study from 2024, Harrison et al. found that adverse SDOH including low income, lack of health insurance, and food insecurity were differentially associated with higher prediabetes prevalence among adolescents [

31].

In our study, patients over 60 years of age predominated in the group of patients with diabetic gastroparesis, 56% were female, and females with low incomes and rural residency were far more predisposed to developing complications than males from rural areas. In an urban environment, this discrepancy decreased. Equal proportions of females and males were smokers, although men were more likely to consume alcohol. In Romania, the number of males who smoke and chronically consume alcohol is higher than the number of females who engage in these practices. Although symptoms such as epigastralgia, nausea accompanied by vomiting, and intestinal transit disorders guide the diagnosis of gastroparesis, as diabetes mellitus deeply affects the innervation of the stomach, the intensity of these symptoms does not reflect the actual severity of the gastric damage. Thus, trivial and non-specific symptomatology can hide substantial gastric damage, which may be the reason why type 2 diabetes sometimes cannot be controlled by usual therapeutic means. The aggravation of gastroparesis in the studied patients was manifested by gastric lesions, which indicate uncontrolled diabetes with a long evolution. In specialized studies of patients with type 2 diabetes with upper digestive endoscopy, mucosal lesions with antral localization were the predominant type, which is explained by the fact that patients with diabetes have a higher risk of bile reflux. In 2016, a study conducted in Turkey on a group of 51 patients with type 2 diabetes, of whom 30 had gastroparesis proven by scintigraphy, found that under endoscopic examination, patients with gastroparesis had a higher frequency of erosive-type gastric lesions, a phenomenon explained by prolonged gastric stasis.

Our statistical analysis revealed that rural residence, low income, obesity, and poor glycemic control (HbA1c > 8.0%) were significant independent predictors of frequent hospitalizations. Patients from rural areas had significantly higher HbA1c levels and obesity rates, consistent with limited healthcare access and dietary differences. Although epigastric symptoms were more frequent among low-income patients, these differences did not reach statistical significance. However, their hospitalization rate was significantly higher, highlighting the burden of socioeconomic disparities in diabetes management. Logistic regression confirmed low income and poor glycemic control as strong predictors, aligning with the existing literature.

Thus, the first step in evaluating patients with type 2 diabetes, especially those with long-term evolution and multiple complications, must take into account the possibility of diabetic gastroparesis.

Importantly, addressing social determinants through multidisciplinary care, patient education, and community outreach can enhance outcomes.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small and drawn from a single tertiary center, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents causal inference between social factors and the severity of gastroparesis. Third, while we identified associations between social factors and disease characteristics, no statistical tests were applied due to the descriptive scope of the study. Future multicenter studies with larger samples and statistical modeling are warranted.

6. Perspectives and Future Research

The growing recognition of the importance of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) in chronic disease management calls for a paradigm shift in both clinical care and public health strategy. In the context of diabetic gastroparesis, proactively addressing SDOH may prevent disease progression and reduce the healthcare burden.

From a preventive standpoint, future strategies should incorporate routine screening for SDOH in clinical settings using validated instruments, such as the PRAPARE (Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experience screener) [

32] or EPIC SDOH [

33] tools. This could facilitate early identification of at-risk individuals and inform personalized care plans. Primary care teams, including social workers and patient navigators, should be integrated to support these patients holistically.

Community-level interventions—particularly in rural and low-income areas—may improve outcomes by addressing modifiable risk factors such as nutrition, glycemic control, and social isolation. Educational campaigns, social prescribing models, and mobile health units could be key tools in reaching vulnerable populations.

From a research perspective, the warranted future directions are as follows:

Longitudinal cohort studies are needed to assess the cumulative impact of SDOH on the onset, severity, and healthcare utilization patterns of diabetic gastroparesis over time.

Randomized interventional trials could evaluate the effectiveness of targeted SDOH interventions (e.g., nutritional support, transportation vouchers, social connection programs) in reducing hospital admissions and improving symptom control.

Predictive modeling using artificial intelligence could aid in the early identification of high-risk patients by integrating clinical, biochemical, and social variables.

Cost-effectiveness analyses are essential to justify policy changes and to demonstrate the financial benefits of incorporating social risk screening into diabetes care.

Development and validation of SDOH risk indices tailored to the European diabetic population could enhance clinical decision-making and stratification of care.

Ultimately, bridging the gap between medical care and social support systems will be crucial to achieving equity and improving outcomes in diabetic gastroparesis and other chronic conditions.

Conclusions

Diabetic gastroparesis is underdiagnosed and frequently misattributed to other causes. Gastric complications in diabetes are often overlooked in favor of more prominent issues such as macro- and microangiopathy. Diffuse and erosive mucosal lesions found in upper endoscopy were common in diabetic gastroparesis patients, particularly among those with prolonged gastric stasis. Obesity and female sex, present in nearly half the cohort, contributes to insulin resistance and complicates glycemic control. Low socioeconomic status, rural residence, and social isolation were linked to poor disease management and frequent exacerbations, particularly during seasonal dietary changes. Addressing SDOH is essential in reducing hospitalizations and improving the quality of life for patients with diabetic complications, through screening protocols in low-income diabetes populations, which represents a public health issue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S. and R.M; wrote the manuscript and researched data, I.S., R.M. and A.T.; reviewed the manuscript, A.C., M.C., V.R., G.V., R.G., L.R. and D.N.; supervision G.L., R.M., M.M. and F.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. The guarantor is dr. Ioana Soare.

Funding

The authors declare they have no financial interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health—Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Rowe, R. Social determinants of health in the Big Data mode of population health risk calculation. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, S.; Zheng, T.; Camilleri, M. Epidemiology and Healthcare Utilization in Patients With Gastroparesis: A Systematic Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2239–2251.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh S., Aswath; Lisa A., Foris; Ashwini, K. Ashwath et al. Diabetic Gastroparesis. StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Last Update:March 27, 2023.

- Parkman, H.P.; Hasler, W.L.; Fisher, R.S. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1592–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshatian L, Gibbons SJ, Farrugia G. et al. Macrophages in diabetic gastroparesis--the missing link? Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27:7.

- Harberson, J.; Thomas, R.M.; Harbison, S.P.; Parkman, H.P. Gastric Neuromuscular Pathology in Gastroparesis: Analysis of Full-Thickness Antral Biopsies. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, M.; Bernard, C.E.; Pasricha, P.J.; Lurken, M.S.; Faussone-Pellegrini, M.S.; Smyrk, T.C.; Parkman, H.P.; Abell, T.L.; Snape, W.J.; Hasler, W.L.; et al. Clinical-histological associations in gastroparesis: results from the Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012, 24, 531–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, J.; Thomas, R.M.; Parkman, H.P. Gastric neuromuscular histology in patients with refractory gastroparesis: Relationships to etiology, gastric emptying, and response to gastric electric stimulation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:18.

- Choi, K.M.; Gibbons, S.J.; Nguyen, T.V.; Stoltz, G.J.; Lurken, M.S.; Ordog, T.; Szurszewski, J.H.; Farrugia, G. Heme Oxygenase-1 Protects Interstitial Cells of Cajal From Oxidative Stress and Reverses Diabetic Gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 2055–2064.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangula, P.R.R.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Ravella, K.; Cai, S.; Channon, K.M.; Garfield, R.E.; Pasricha, P.J. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a cofactor for nNOS, restores gastric emptying and nNOS expression in female diabetic rats. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2010, 298, G692–G699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.M.; Kashyap, P.C.; Dutta, N.; Stoltz, G.J.; Ordog, T.; Donohue, T.S.; Bauer, A.J.; Linden, D.R.; Szurszewski, J.H.; Gibbons, S.J.; et al. CD206-Positive M2 Macrophages That Express Heme Oxygenase-1 Protect Against Diabetic Gastroparesis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2399–2409.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caturano, A.; Cavallo, M.; Nilo, D.; Vaudo, G.; Russo, V.; Galiero, R.; Rinaldi, L.; Marfella, R.; Monda, M.; Luca, G.; et al. Diabetic Gastroparesis: Navigating Pathophysiology and Nutritional Interventions. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, C.K.; Samsom, M.; Jones, K.L.; Horowitz, M. Relationships of Upper Gastrointestinal Motor and Sensory Function With Glycemic Control. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revicki DA, Speck RM, Lavoie S, et al. The American neurogastroenterology and motility society gastroparesis cardinal symptom index-daily diary (ANMS GCSI-DD): Psychometric evaluation in patients with idiopathic or diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019 Apr;31(4):e13553[PubMed.

- Abell, T.L.; Kedar, A.; Stocker, A.; Beatty, K.; McElmurray, L.; Hughes, M.; Rashed, H.; Kennedy, W.; Wendelschafer-Crabb, G.; Yang, X.; et al. Gastroparesis syndromes: Response to electrical stimulation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, R.; Khalid, S.; Tafoya, M.A.; McCarthy, D. Nausea and Vomiting in a Diabetic Patient with Delayed Gastric Emptying: Do not Delay Diagnosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.; Stevens, J.E.; Chen, R.; Gentilcore, D.; Burnet, R.; Horowitz, M.; Jones, K.L. Insulin-Induced Hypoglycemia Accelerates Gastric Emptying of Solids and Liquids in Long-Standing Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4489–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkman, H.P.; Hasler, W.L.; Fisher, R.S. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1592–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, R.J.; Horowitz, M.; Maddox, A.F.; Harding, P.E.; Chatterton, B.E.; Dent, J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990, 33, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wytiaz, V.; Homko, C.; Duffy, F.; Schey, R.; Parkman, H.P. Foods Provoking and Alleviating Symptoms in Gastroparesis: Patient Experiences. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homko, C.J.; Duffy, F.; Friedenberg, F.K.; Boden, G.; Parkman, H.P. Effect of dietary fat and food consistency on gastroparesis symptoms in patients with gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 27, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.G.; Christian, P.E.; Coleman, R.E. Gastric emptying of varying meal weight and composition in man. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1981, 26, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujanda, L. The effects of alcohol consumption upon the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol.2000 Dec;95(12):3374-82.

- Miller, G.; Palmer, K.R.; Smith, B.; Ferrington, C.; Merrick, M.V. Smoking delays gastric emptying of solids. Gut 1989, 30, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan AH, Suwadi BH, Kholili U. et al. Diabetic Gastroenteropathy: A Complication of Diabetes Mellitus. Acta Med Indones 2019; 51: 263.

- Moshiree, B.; Potter, M.; Talley, N.J. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Gastroparesis. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. North Am. 2019, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeroff, J.C.; Schreiber, D.S.; Trier, J.S.; Blacklow, N.R. Abnormal Gastric Motor Function in Viral Gastroenteritis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1980, 92, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilleri, M. Clinical practice. Diabetic gastroparesis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:820.

- Harrison, C.; Peyyety, V.; Gonzalez, A.R.; Chivate, R.; Qin, X.; Zupa, M.F.; Ragavan, M.I.; Vajravelu, M.E. Prediabetes Prevalence by Adverse Social Determinants of Health in Adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2416088–e2416088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Clay, O.J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Howell, C.R. Analyzing Multiple Social Determinants of Health Using Different Clustering Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2024, 21, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganatra, S.; Khadke, S.; Kumar, A.; Khan, S.; Javed, Z.; Nasir, K.; Rajagopalan, S.; Wadhera, R.K.; Dani, S.S.; Al-Kindi, S. Standardizing social determinants of health data: a proposal for a comprehensive screening tool to address health equity a systematic review. Heal. Aff. Sch. 2024, 2, qxae151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).