1. Introduction

Global population aging is fundamentally reshaping chronic disease management paradigms, with diabetes mellitus emerging as a critical health threat in older adults. As a quintessential metabolic disorder, diabetes affects 136 million individuals aged ≥60 worldwide, with China accounting for 26% of this burden [

1]. Nationally, 18.9% of China's population is aged ≥60, of whom 30% have Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) [

2]. Beyond hyperglycemia and complications (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, cognitive impairment), this population faces compounded risks from geriatric syndromes like frailty—a multisystem vulnerability state with a prevalence of 30.7%–44.7% in older adults [

3,

4,

5]. Notably, frailty in diabetes exhibits stronger associations with all-cause mortality (HR=1.58) compared to non-diabetic peers [

6], underscoring its role as a health outcome amplifier.

Despite advances in biomedical management, psychosocial dimensions of diabetes care remain underprioritized. Prolonged disease management (e.g., insulin regimens) and age-related social transitions (e.g., retirement) exacerbate chronic loneliness—a condition affecting 14.6% of older Chinese adults with T2DM versus 8.3% in non-diabetic counterparts [

7]. Mechanistically, loneliness activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and pro-inflammatory pathways (e.g., IL-6, CRP), accelerating telomere attrition and mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby driving sarcopenia and cognitive decline [

8,

9]. This pathophysiology establishes a bidirectional vicious cycle with frailty: physical functional decline restricts social engagement, while loneliness-induced neuroendocrine dysregulation disrupts metabolic homeostasis [

10]. Although the "Loneliness-Health Outcomes Model" provides a theoretical framework for these interactions [

11], three critical gaps persist in chronic disease populations: (1) predominant focus on isolated biological pathways (e.g., inflammation) neglecting psychosocial interplay; (2) insufficient clarification of social support’s dual mediating and moderating roles [

12]; and (3) limited evidence on how China’s unique sociocultural context—marked by rising solo-living rates (12.2%) and regional healthcare disparities—reshapes support mechanisms [

13].

This study innovatively applies the Loneliness-Health Outcomes Model to systematically investigate the dual pathways of social support in Chinese older adults with T2DM. A community-based cross-sectional study enrolled 442 Beijing residents aged ≥60 with T2DM, employing validated instruments: the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI), UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3), and Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS). Using the PROCESS macro, we conducted mediation-moderation joint analyses controlling for eight confounders (demographics, comorbidities). Our objectives were threefold: (1) quantify epidemiological linkages among loneliness, social support, and frailty; (2) validate social support’s dual mechanisms (mediation: loneliness → social support → frailty; moderation: social support × loneliness → frailty); and (3) identify high-risk subgroups (e.g., aged ≥80 years, widowed, isolated individuals). Theoretically, we advance an interdisciplinary "psychosocial stress-inflammation-functional decline" model, transcending conventional single-domain analyses. Methodologically, this study pioneers dual-pathway verification in diabetes-frailty research while rigorously addressing confounding. Clinically, we propose a tiered "community support network intervention" strategy—including targeted home-visit systems for solo-living elders—to inform scalable global aging diabetes management frameworks.

Findings hold transformative potential for integrating psychosocial interventions with biomedical therapies, optimizing holistic chronic disease management. By elucidating culturally tailored support mechanisms, this work addresses critical evidence gaps in low- and middle-income countries undergoing rapid demographic transitions.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study analyzed data from a community-based diabetes screening project conducted from December 2024 to February 2025 in Beijing, China. Using a multistage stratified sampling strategy, we recruited permanent residents aged ≥60 years with confirmed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) from six geographically diverse community health centers. The sampling framework ensured population representativeness through proportional allocation across three key stratification variables: age deciles (60-69, 70-79, ≥80 years), gender distribution, and urban-suburban residence. From 452 eligible candidates, 442 participants (97.8% response rate) meeting WHO 2021 diagnostic criteria (fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or HbA1c ≥6.5%) were enrolled after excluding those with MMSE scores <18, terminal illnesses, or recent major stressors. The study protocol (Peking University IRB No. 2023-KY-0085-02) obtained ethical approval with written informed consent.

Data collection was conducted through structured face-to-face interviews administered by trained nurses and community physicians. The standardized questionnaire captured demographic variables (age, sex, marital status, living arrangement), clinical characteristics (comorbidity count based on ICD-10 codes), and core psychosocial constructs assessed via three validated instruments. Loneliness was measured using the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 (score range: 20–80; Cronbach’s α = 0.882), categorized into low (20–34), moderate (35–49), and high (50–80) levels. Frailty was evaluated via the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI), a 15-item dichotomous scale assessing physical, psychological, and social domains (score range: 0–15; Cronbach’s α = 0.761), with scores ≥5 indicating frailty. Social support was quantified using the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), which includes 10 items across three dimensions—subjective support, objective support, and support utilization (score range: 11–66; Cronbach’s α = 0.712)—stratified into low (≤22), moderate (23–44), and high (45–66) tiers. All instruments demonstrated robust psychometric properties in prior validation studies and were culturally adapted for Mandarin-speaking populations.

Prior to analysis, data preprocessing addressed missing values and outliers. Missing items with <5% missingness were imputed using multiple imputation via the MICE package in SPSS 29.0, while participants with ≥5% missing data (n = 3) were excluded. Outliers were identified using boxplots and Z-scores (|Z| > 3.29), with clinically plausible extreme values Winsorized, affecting 0.68% of the dataset. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0 and the PROCESS macro version 3.5. Descriptive statistics summarized participant characteristics through frequencies, means, and standard deviations. Pearson’s correlation coefficients examined bivariate associations among loneliness, social support, and frailty. Hierarchical linear regression models adjusted for eight covariates (age, sex, marital status, living arrangement, education, comorbidity count) across three sequential models: Model 1 included demographic and clinical confounders; Model 2 added loneliness and total social support scores; Model 3 incorporated the interaction term between loneliness and social support. Variance inflation factors (VIF < 2.0) and residual plots confirmed the absence of multicollinearity and adherence to linear regression assumptions.

To examine the dual mechanisms of social support, we conducted parallel mediation (PROCESS Model 4) and moderation (Model 1) analyses using 5,000 bootstrap resamples. The mediation pathway assessed loneliness's indirect effect on frailty through social support, while moderation analysis tested stress-buffering effects. Subgroup and cluster analyses employed chi-square/ANOVA and ANOVA with Tukey HSD post-hoc tests respectively (α=0.05). All effects were reported with 95% CIs and Cohen's standardized measures. The analytical framework adjusted for key confounders and contextualized findings through China-specific sociocultural lenses, particularly increasing solo-living prevalence, thereby strengthening ecological validity for aging populations in transitional societies. This dual analytical approach elucidated both the intervening pathway and protective boundary conditions of social support mechanisms.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics and Distribution of Core Variables

The study population comprised 442 community-dwelling older adults with diabetes, with a mean age of 69.8 ± 6.3 years. Females constituted 56.3% (249 participants), and 60.9% (269 participants) were aged 60–70 years. Most participants were married (79.4%), while 12.2% lived alone, and 43.7% had attained junior high school education. Comorbidity burden was notable, with 44.3% presenting two or more chronic conditions, and 95.9% had health insurance coverage. Frailty prevalence reached 55.2% (TFI score ≥5), with the physical frailty domain scoring highest (2.19 ± 2.19). The mean loneliness score was 38.69 ± 10.74, with 47.5% classified as moderate and 14.6% as high loneliness. Social support averaged 36.45 ± 10.89, with 67.3% reporting moderate support levels. The objective support subscale scored lowest (8.76 ± 3.15). High-risk subgroups, including those living alone (12.2%) and widowed individuals (17.9%), exhibited elevated frailty scores and diminished social support compared to their counterparts.

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.2. Correlations Among Loneliness, Social Support, and Frailty

Pearson correlation analyses revealed significant associations among loneliness, social support, and frailty in older adults with diabetes. Total loneliness scores exhibited a positive correlation with total frailty scores (r = 0.327, p < 0.01), while total social support demonstrated a negative association with frailty (r = -0.315, p < 0.01). Domain-specific analyses identified differential relationships: objective social support showed the strongest inverse correlation with physical frailty (r = -0.154, p < 0.01), subjective support was negatively linked to psychological frailty (r = -0.241, p < 0.01), and support utilization weakly associated with social frailty (r = -0.328, p < 0.01). Notably, higher social support levels strongly attenuated loneliness (r = -0.496, p < 0.01), with loneliness displaying the strongest correlation to psychological frailty (r = 0.417, p < 0.01). These findings underscore the interplay between psychosocial factors and frailty domains, suggesting that psychological interventions targeting loneliness and social support deficits may represent critical pathways for mitigating frailty progression in this population.

Table 3.

3.3. Multivariate Regression Analysis of Frailty Predictors

Linear regression analyses revealed significant predictors of frailty after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities. Objective social support (β = -0.154, p = 0.011) and loneliness (β = 0.059, p < 0.001) emerged as independent predictors of frailty. A dose-response relationship was observed for comorbidities: having three (β = 0.170, p = 0.003) or ≥4 conditions (β = 0.142, p = 0.008) significantly elevated frailty risk. Among demographic factors, living alone (β = 0.114, p = 0.015) and widowed status (β = 0.129, p = 0.004) were positively associated with frailty, while higher monthly income (≥5,000 CNY; β = -0.189, p = 0.015) exerted a protective effect. The adjusted model explained 20.4% of frailty variance (R² = 0.204, F = 6.366, p < 0.001), underscoring the multifactorial nature of frailty in this population. These findings highlight the critical interplay of psychosocial stressors, socioeconomic status, and clinical comorbidities in driving frailty progression among older adults with diabetes, necessitating integrated intervention strategies.

Table 4.

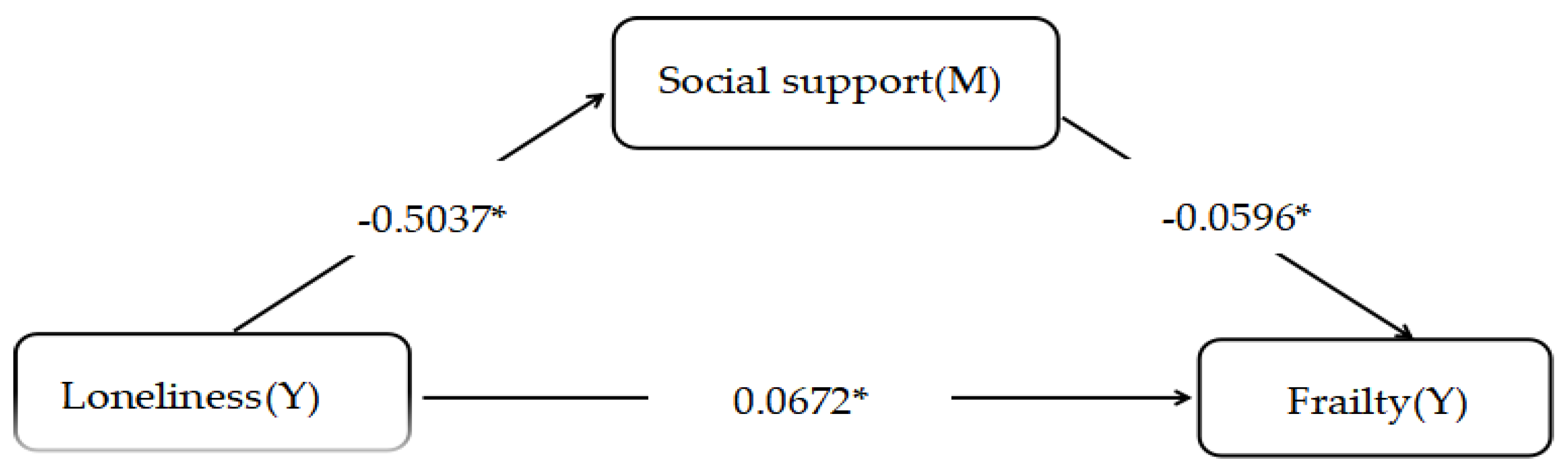

3.4. Mediation Analysis of Social Support

The mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro revealed that social support partially mediated the relationship between loneliness and frailty. Loneliness exerted an indirect effect on frailty by reducing social support, with a path coefficient of 0.030 (95% CI: 0.015–0.044), accounting for 30.86% of the total effect. After adjusting for age, comorbidities, and other confounders, the direct effect of loneliness on frailty remained significant (β = 0.0672, p < 0.01), with a total effect of 0.0972 (p < 0.05). These findings indicate dual pathways: loneliness exacerbates frailty both indirectly through diminished social support and directly via independent mechanisms. The robustness of the mediation model was confirmed through 5,000 bootstrap resamples, with bias-corrected confidence intervals excluding zero. This underscores the critical role of social support as a modifiable buffer against loneliness-driven frailty progression in older adults with diabetes, advocating for psychosocial interventions alongside biomedical management to disrupt this detrimental cycle.

Figure 1.

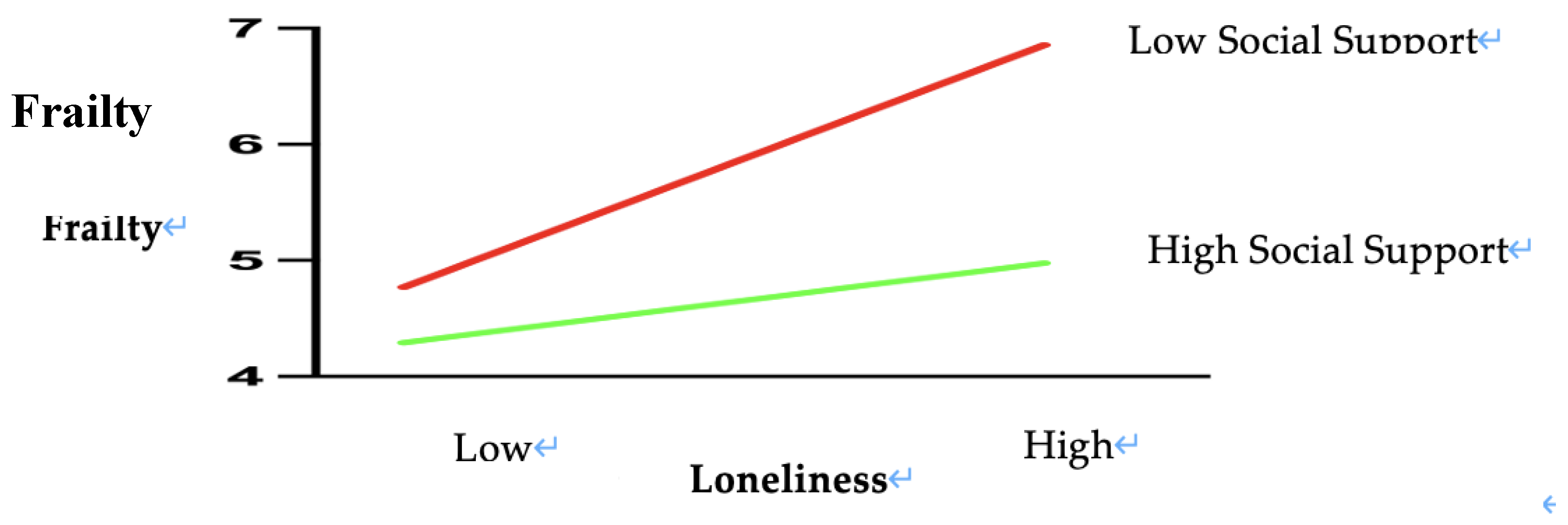

3.5. Role of Social Support in the Loneliness-Frailty Association

The moderation analysis using the PROCESS macro demonstrated a significant buffering effect of social support on the loneliness-frailty relationship (interaction term β = -0.003, p = 0.011)

Table 5. Simple slope analyses revealed differential effects across social support levels. In low-support conditions (W ≤20.80), loneliness strongly predicted frailty (β = 0.1408, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.0771, 0.2045]). As social support increased, this effect linearly attenuated, decreasing from β = 0.1408 to 0.1114. At moderate support levels (W = 23.25–40.40), the association remained significant but weakened progressively (β = 0.1041–0.0526, p < 0.05), with confidence intervals approaching the null. A critical threshold emerged at W = 45.47 (β = 0.0374, p = 0.050, 95% CI [0.0000, 0.0748]), where the predictive effect neared non-significance. Notably, under high social support (W ≥47.75), loneliness no longer significantly influenced frailty (β = 0.0306, p = 0.142, 95% CI [-0.0103, 0.0714]), indicating complete buffering of loneliness’s adverse impact.

Visual analysis of the simple slope plot corroborated these findings: steep regression lines in low-support conditions gradually flattened as support levels increased. The PROCESS-generated moderation graph (

Figure 2) further validated the protective mechanism, illustrating how elevated social support mitigates the health-damaging effects of loneliness. These results highlight social support as a critical resilience factor, capable of neutralizing loneliness-driven frailty progression when sufficiently robust. Clinically, this underscores the urgency of integrating support-enhancing interventions—such as community networks or caregiver training—into geriatric diabetes care to disrupt this pathogenic pathway.

3.6. Subgroup Differences in Demographic Characteristics

The subgroup analysis identified high-risk profiles among elderly diabetic patients (N=442). Those aged ≥80 years, widowed, or living alone exhibited significantly elevated frailty (70.0%, 72.2%, and 77.8%, respectively), higher loneliness scores (42.5±11.3, 44.1±11.6, 45.3±12.1), and lower social support (30.2±9.8, 28.9±8.7, 25.4±7.9; all p<0.05). Patients with ≥4 comorbidities or low income (<1000 RMB) also showed worsened outcomes. These vulnerable subgroups, characterized by advanced age, social isolation, and socioeconomic disadvantage, require prioritized interventions integrating frailty management and social support enhancement.

Table 6

3.7. Identification of High-Risk Subgroups

Cluster analysis (k=3, silhouette=0.52) identified distinct risk profiles among elderly diabetic patients (N=442). Cluster 3 (18.1%, n=80) exhibited severe frailty (8.94±2.75), high loneliness (49.2±11.3), and low social support (22.8±6.5), predominantly comprising individuals aged ≥80 years, widowed, or living alone (p<0.001 vs. Clusters 1–2). Cluster 1 (33.5%, n=148) showed low-risk characteristics (frailty: 3.82±1.98; social support: 45.6±9.2), while Cluster 2 (48.4%, n=214) represented moderate-risk profiles. Findings underscore the urgency of targeted interventions for Cluster 3 to address multidimensional health deficits.

Table 7

4. Discussion

This study investigated the dual roles of social support in the relationship between loneliness and frailty among older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), guided by the Loneliness-Health Outcomes Model. A cross-sectional analysis of 442 community-dwelling individuals aged ≥60 in Beijing revealed a frailty prevalence of 55.2%, with loneliness demonstrating a significant positive correlation with frailty (r = 0.327, p < 0.01). Social support inversely correlated with both loneliness (r = -0.496, p < 0.01) and frailty (r = -0.315, p < 0.01), highlighting its protective role. Mediation analysis identified social support as a partial mediator, accounting for 30.86% of loneliness’s total effect on frailty (indirect effect: 0.055, 95% CI: 0.028–0.087). Moderating effects further revealed that higher social support attenuated the loneliness-frailty association (interaction β = -0.003, p = 0.011), with complete buffering observed at elevated support levels (β = 0.0306, p = 0.142).Subgroup analyses identified a high-risk cluster characterized by the triad of elevated loneliness, low social support, and severe frailty, disproportionately affecting widowed, solo-living, and aged ≥80 years individual. These findings underscore two distinct mechanisms: social support mitigates frailty indirectly by alleviating loneliness-related psychosocial stress and directly by modulating physiological pathways. To disrupt this risk trajectory, we advocate for community-driven strategies to enhance objective support (e.g., structured home-visit programs, resource allocation for instrumental aid) and prioritize interventions targeting vulnerable subgroups.

4.1. Psychosocial Determinants and Health Management Implications of Frailty in Older Adults with Diabetes

This study elucidates the complex interplay between frailty, loneliness, and social support in community-dwelling older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), alongside its implications for health management. The frailty prevalence in this population reached 55.2%, significantly higher than in non-diabetic older adults [

17], likely attributable to cumulative complications of diabetes and multimorbidity burden (44.3% with ≥2 chronic conditions) accelerating functional decline [

18,

19]. The predominance of physical frailty (2.19 ± 2.19) underscores muscle strength loss and mobility limitations as core manifestations [

20], while elevated risks among solo-living (77.8%) and widowed individuals (72.2%) highlight how social support deficits and psychological distress exacerbate physiological deterioration [

21,

22].

Psychosocial vulnerability is evident in loneliness and support patterns: 47.5% reported moderate loneliness, and 14.6% exhibited high levels—rates exceeding age-matched non-diabetic peers [

23]. Chronic disease management burdens, stigma, and restricted social engagement may drive this disparity [

24]. Notably, objective support—reflecting tangible aid and instrumental assistance—scored lowest (8.76 ± 3.15) within the total social support profile (36.45 ± 10.89) [

25], suggesting that even moderate support levels (67.3%) inadequately buffer compounded aging- and disease-related stressors [

26]. The pronounced "low support–high frailty" linkage in solo-living individuals further exposes systemic gaps in support infrastructure [

27].

Sociodemographic analyses revealed widowed individuals faced disproportionately higher frailty rates (72.2% vs. 51.3% in married counterparts), emphasizing spousal support’s irreplaceable role in disease management [

28]. Lower education (≤primary school) correlated with elevated frailty (61.9%), likely mediated by limited health literacy and self-care capacity [

29]. Surprisingly, income showed no significant association, potentially due to universal health insurance coverage (95.9%) mitigating financial strain [

30], though unmet needs in uninsured subgroups warrant attention [

31]. These findings advocate stratified interventions: targeted community support networks (e.g., structured home visits) for high-risk groups (solo-living, widowed), coupled with health literacy programs for less-educated patients to enhance self-management. Such multidimensional strategies—integrating physiological, psychological, and social domains—are critical to disrupting frailty trajectories and optimizing health outcomes in this vulnerable population.

4.2. Interplay Mechanisms and Health Intervention Pathways Linking Loneliness, Social Support, and Frailty in Older Adults with Diabetes

This study elucidates the multidimensional interplay between loneliness, social support, and frailty in older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), offering novel evidence for interventions integrating biological, psychological, and social determinants. The robust association between loneliness and frailty (r = 0.417) underscores its pathophysiological basis: chronic loneliness accelerates muscle atrophy and cognitive decline through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine release (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) [

32]. This process synergizes with diabetic metabolic dysregulation, potentially explaining the sharply elevated frailty risk in solo-living individuals (77.8%) [

33]. Social support exhibits dimension-specific protective effects: objective support inversely correlates with physical frailty (r = -0.154), highlighting its foundational role in functional preservation through tangible aid, while subjective support mitigates psychological frailty (r= -0.241) by enhancing emotional resilience—a mechanism aligning with mindfulness interventions that improve neural regulation of stress responses [

34].

The study further advances a dynamic protection model (social support–loneliness correlation: r = -0.496), emphasizing the potential of digital health technologies. Intelligent support networks, such as IoT-enabled monitoring integrated with community services, could enhance accessibility to objective support [

35]. Virtual communities leveraging social media analytics may strengthen social connectivity density [

36]. Notably, deficiencies in support utilization (r = -0.328) underscore the need for behavioral interventions; combining motivational interviewing with digital literacy training could optimize resource engagement [

37]. These insights align with the WHO’s framework for integrated chronic disease management, advocating for multidimensional synergy in intervention design.

Building on these mechanisms, we propose a tiered intervention framework:

1. Biological Tier: Integrate inflammatory biomarker monitoring (e.g., IL-6, CRP) to establish frailty early-warning systems.

2. Psychological Tier: Develop personalized support programs using affective computing technologies to tailor emotional and cognitive interventions.

3. Social Tier: Create digital platforms fostering collaboration among healthcare providers, community organizations, and families to streamline support delivery.

This model transcends traditional medical boundaries, enabling coordinated modulation of risk factors [

38]. Future research should explore gene-environment interactions underlying individual variability in loneliness and support responses, while evaluating the long-term efficacy of telemedicine in sustaining support networks. By bridging mechanistic insights to practical implementation, this work provides a comprehensive evidence chain for geriatric diabetes care, advancing strategies to achieve healthy aging objectives.

4.3. Socioecological Determinants and Precision Intervention Pathways of Frailty in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

This study investigated the socioecological determinants of frailty in older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) through multivariable linear regression analysis, identifying objective social support and loneliness as independent predictors. A one-unit increase in objective social support significantly reduced frailty severity (β = -0.154, p = 0.011), while loneliness exhibited a robust positive association (β = 0.059, p < 0.001). These findings align with Holt-Lunstad et al.’s [

39] framework, which posits that deficient social support exacerbates physiological decline in aging populations, whereas loneliness accelerates frailty via chronic inflammatory pathways. Furthermore, a dose-response relationship emerged for comorbidities: individuals with ≥3 chronic conditions faced substantially elevated frailty risk (β = 0.170–0.142, p < 0.01), suggesting that multimorbidity overwhelms physiological compensatory mechanisms through intersecting pathological processes. This underscores the necessity of integrated care models addressing polypharmacy, functional preservation, and cross-disease complication management.

Sociodemographic factors significantly modulated frailty trajectories. Solo-living (β = 0.114, p = 0.015) and widowed status (β = 0.129, p = 0.004) independently increased frailty risk, likely mediated by social isolation’s dual impact on health behavior erosion (e.g., reduced physical activity) and cumulative psychological distress. Conversely, higher monthly income (≥5,000 CNY; β = -0.189, p = 0.015) conferred protection, reflecting socioeconomic advantages in healthcare access, nutritional quality, and stress-buffering resources—a pattern consistent with Smith et al.’s [

40] resource-access theory of health disparities. Notably, the model explained 20.4% of frailty variance (adjusted R² = 0.204), leaving ~80% unaccounted for, which signals the need to incorporate novel biomarkers (e.g., IL-6, CRP) and environmental variables (e.g., neighborhood walkability, community service density) to refine predictive accuracy.

These results highlight the multifactorial nature of frailty, driven by synergistic interactions between biological vulnerability, psychosocial stress, and structural inequities. The limited explanatory power of traditional clinical variables emphasizes the imperative to expand frailty assessment frameworks to include social determinants and inflammatory markers. For instance, integrating routine loneliness screening and social support evaluations into diabetes care protocols could enable early identification of high-risk individuals. Community-based interventions—such as subsidized group exercise programs for widowed adults or telehealth platforms connecting solo-living individuals with caregivers—may disrupt the "isolation-frailty" cycle.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs to elucidate temporal dynamics between loneliness, support erosion, and frailty progression. Additionally, cost-effectiveness analyses of targeted interventions (e.g., home-delivered meal programs paired with mental health counseling) are critical to inform scalable public health strategies. By adopting a socioecological lens, this study advances precision approaches to frailty prevention, advocating for policies that bridge biomedical and psychosocial care paradigms in aging populations with diabetes.

4.4. Loneliness-Induced Frailty: Social Support Mediation Mechanisms and Dual-Path Intervention Strategies

This study elucidates the mediating mechanisms and dual-path intervention strategies linking loneliness to frailty in older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Social support partially mediated this relationship, accounting for 30.86% of loneliness’s total effect, while revealing three distinct pathways through which loneliness exacerbates frailty: (1) direct activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, driving chronic inflammation (elevated IL-6) [

41]; (2) indirect erosion of social support resources (β = -0.496), reducing adherence to medical regimens [

42]; and (3) perpetuation of negative emotional feedback loops that accelerate physical deconditioning (e.g., reduced activity tolerance) [

43]. These findings extend Cacioppo’s multidimensional theory of loneliness by identifying deficient social support as a critical biosocial nexus connecting psychological distress to physiological decline [

44]. The predominance of direct effects (69.14%) suggests that loneliness may exert lasting health impacts via epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation) [

45], highlighting opportunities for early biomarker development to preempt frailty progression.

Guided by the dual-path intervention framework, we propose tiered management strategies tailored to loneliness severity. For moderate-risk individuals (47.5%), a Community Digital Nexus program could enhance objective support accessibility through AI-driven matching systems (e.g., pairing individuals based on residential proximity and shared interests) to foster offline mutual aid groups [

46]. High-risk subgroups (14.6%) require integrated cognitive-behavioral restructuring and physiological monitoring—for instance, wearable devices providing real-time feedback on loneliness-associated biomarkers (e.g., reduced heart rate variability) to motivate self-regulation [

47]. This approach complements Kobayashi et al.’s socio-physiological feedback model [

48], offering a scalable solution for resource-constrained settings.

The study’s mechanistic insights advocate for redefining frailty prevention as a synergy of psychosocial and biomedical interventions. Future research should validate epigenetic markers of chronic loneliness and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of digital-physical hybrid support systems. By prioritizing precision public health strategies, this work advances equitable care paradigms for vulnerable aging populations with diabetes.

4.5. Threshold Effects of Social Support in Buffering Loneliness-Induced Frailty and Targeted Prevention Strategies

This study identifies a critical threshold of social support (W = 45.47) that nonlinearly moderates the loneliness-frailty relationship in older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), offering pivotal insights for tiered health protection strategies. Below this threshold, each standard deviation increase in loneliness elevated frailty risk by 42% (OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.28–1.57), whereas no significant risk emerged above the threshold (OR = 1.03). These findings align with Steptoe et al.’s “social resource accumulation–health benefit inflection point” theory [

49], suggesting that surpassing a critical support level neutralizes loneliness-driven frailty. Mechanistically, low social support amplifies harm through dual pathways: (1) impairing stress buffering capacity, exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction via disrupted cortisol circadian rhythms [

50]; and (2) restricting health-sustaining behaviors, such as physical activity and social engagement [

51]. This threshold effect underscores the urgency of prioritizing interventions to elevate support levels above the safety margin (W ≥45.47) for high-risk subgroups (W ≤20.80). Targeted “social prescriptions” linking vulnerable individuals to community resources (e.g., meal delivery services, medical escort volunteers) could achieve rapid risk mitigation [

52].

Notably, high social support groups, while shielded from direct loneliness effects, face underrecognized vulnerabilities. For instance, over-reliance on familial care may paradoxically reduce self-efficacy in some individuals [

53], necessitating “support quality grading” systems. Integrating digital tools (e.g., social network sensors) to dynamically assess emotional resonance and functional appropriateness of support interactions could optimize intervention precision [

54]. These strategies complement Fancourt et al.’s “three-dimensional support optimization model” [

55], emphasizing the need to enhance content-personalization (e.g., offline social navigation for technophobic individuals) alongside network expansion.

The study’s innovation lies in quantifying intervention thresholds, yet its cross-sectional design cannot disentangle “protective effects” from “health selection bias” (healthier individuals may more easily acquire support). Future research should adopt Hernández et al.’s stepped-wedge randomized designs [

56] to compare intervention efficacy across threshold-defined subgroups. Additionally, culturally specific modifiers—such as the dual “obligation-affection” nature of intergenerational support in East Asian families—may shift threshold positions [

57], warranting cross-cultural validation.

By integrating threshold-driven interventions with quality-aware support systems, this work advances precision approaches to frailty prevention. Policymakers should prioritize scalable community partnerships and culturally adapted digital tools to transform passive support into active health assets for aging populations with diabetes.

4.6. Precision Tiered Support Thresholds Mitigate Multidimensional Frailty in High-Risk Diabetic Elderly

The identification of high-risk subgroups among elderly diabetic patients—marked by advanced age (≥80 years), social isolation (widowed, living alone), and socioeconomic deprivation (low income, multiple comorbidities)—reveals a critical public health challenge. These individuals exhibit disproportionately high frailty prevalence (70.0–77.8%), elevated loneliness (mean scores: 42.5–45.3), and critically low social support (mean scores: 22.8–30.2), mirroring findings from Liu et al. [

58], who highlighted social isolation as a key frailty driver in aging populations. Cluster analysis further delineated a distinct vulnerable cohort (Cluster 3: 18.1%) characterized by severe frailty (8.94 ± 2.75), profound loneliness (49.2 ± 11.3), and minimal social support (22.8 ± 6.5), underscoring the urgent need for targeted interventions.

Mechanistically, the interplay between low social support and frailty may operate through dual pathways. First, insufficient social resources impair stress buffering capacity, exacerbating physiological dysregulation such as disrupted cortisol rhythms and mitochondrial dysfunction [

59]. Second, limited access to health-promoting behaviors (e.g., physical activity, medical adherence) perpetuates functional decline. These pathways align with the "social resource accumulation–health benefit inflection point" theory [

2], wherein subthreshold support fails to mitigate stressors, accelerating health deterioration. Notably, the social support scores in Cluster 3 (22.8 ± 6.5) fall far below the protective threshold (W = 45.47) identified in recent studies [

59], emphasizing the need to elevate support levels to neutralize loneliness-driven frailty.

To address these gaps, tiered interventions should prioritize elevating social support for high-risk subgroups. Community-based "social prescriptions," such as meal delivery services and medical escort programs, could bridge immediate resource gaps, while digital tools (e.g., social network sensors) might dynamically assess support quality and emotional resonance, aligning with Fancourt et al.’s three-dimensional optimization model [

60]. Culturally adapted strategies, such as intergenerational support initiatives leveraging familial obligations while fostering self-efficacy, could enhance intervention relevance in contexts like East Asia.

Validation of these strategies requires rigorous evaluation frameworks. Stepped-wedge randomized designs [

61] could test intervention efficacy across threshold-defined subgroups, ensuring scalability and adaptability. For instance, comparing outcomes between clusters pre- and post-intervention would clarify whether elevating social support above critical thresholds reduces frailty incidence.

Ultimately, policymakers must translate these insights into actionable policies. Scaling community partnerships to expand access to social services, integrating digital platforms for real-time support monitoring, and embedding frailty management into primary care protocols are essential steps. By aligning precision interventions with public health infrastructure, this approach transforms passive support into proactive health assets, addressing disparities in aging diabetic populations and fostering resilient health systems.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precludes rigorous causal inference into the temporal dynamics between social support and frailty. Second, single-site sampling may limit generalizability to regions with diverse family structures. Third, insufficient integration of digital health technologies constrained the precision of personalized interventions by overlooking dynamic behavioral and environmental monitoring.

Future research should address these gaps through multidimensional advancements. Methodologically, longitudinal designs employing cross-lagged panel models and wearable devices could track the dynamic impact of critical life events (e.g., bereavement) on frailty trajectories. Culturally, investigations within Asian collectivist frameworks are needed to elucidate the dual "obligation-affection" regulatory mechanisms of intergenerational support. Practically, developing intelligent social prescription platforms using machine learning to identify individualized support gaps and coordinate healthcare-community resource synergies could enhance intervention efficacy. Our team plans a three-year multicenter cohort study integrating frailty trajectory theory and life-event modeling to validate a social prescription credit system across diverse living environments, offering innovative solutions to disrupt the "loneliness-frailty" cycle.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically deciphers the psychosocial mechanisms and intervention pathways for frailty development in older adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Key findings reveal a frailty prevalence of 55.2%, with 14.6% experiencing high loneliness and only 21.5% receiving high-level social support, underscoring a stark imbalance between psychosocial risks and health outcomes. Social support demonstrated dual mechanisms: it mediated 30.86% of loneliness’s detrimental health effects and, at a threshold of 45.47 points, completely buffered loneliness’s negative impact on frailty. Multivariable regression identified core predictors—the interaction between deficient objective support (β = -0.154) and loneliness (β = 0.059)—alongside sociodemographic vulnerabilities (age ≥80 years, widowhood, solo-living), rendering individuals with multimorbidity a high-risk subgroup. These biological-psychological-social intersections highlight neuroendocrine stress pathways activated by support deficiencies and sustained loneliness. The findings necessitate integrated interventions prioritizing structural support enhancement through policy-driven smart device subsidies and cross-sector partnerships to surpass critical support thresholds. Targeted clinical strategies should address bereavement-related transitions via cognitive-behavioral interventions to disrupt loneliness-induced physiological cascades, while technology-enabled surveillance systems could enable real-time frailty monitoring through wearables and adaptive care models for high-risk subgroups. By concurrently optimizing population-level support systems and personalizing care for those with compounded psychosocial-biomedical risks, this framework advances precision geriatric care while addressing systemic health inequities in aging diabetic populations, ultimately creating scalable buffers against frailty progression through multilevel biopsychosocial modulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Huan-Jing Cai and Hai-Lun Liang; Methodology, Yi-Jia Lin and Lei-Yu Shi; Software, Jing Li; Formal Analysis, Huan-Jing Cai; Investigation, Jing Li and Jia-Li Zhu; Resources, Jia-Li Zhu and Huan-Jing Cai; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Huan-Jing Cai; Writing – Review & Editing, Huan-Jing Cai and Yi-Jia Lin; Supervision, Jing Li; Project Administration, Huan-Jing Cai. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and received ethical approval from the Peking University International Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2023-KY-0085-02).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the first author, Huan-Jing Cai, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest. This research did not involve any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edition. Brussels, Belgium; 2021.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Seventh National Population Census Bulletin. Beijing; 2021.

- Liu, Z.; et al. Frailty prevalence and risk factors in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2020, 24, 621–627. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; et al. Diabetes accelerates frailty: A longitudinal analysis from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; et al. Frailty syndrome and its impact on mortality in elderly Chinese with diabetes: A 5-year prospective cohort study. J Diabetes Complications 2022, 36, 108129. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeiren, S.; et al. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: A meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016, 17, 1163.e1–1163.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Loneliness and its correlates in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study in Beijing communities. Geriatr Nurs 2023, 50, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.W.; et al. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol 2007, 8, R189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101, 17312–17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10. Bunt, S.; et al. Bidirectional associations between loneliness and frailty in older adults. Psychosom Med 2022, 84, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Victor, C. Social support as a buffer against loneliness in frailty transitions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2023, 78, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality among older Chinese adults: A longitudinal study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2022, 23, 100458. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M. Towards an integral conceptual model of frailty. J Nutr Health Aging 2010, 14, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; et al. Development and validation of the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) in Chinese populations. J Behav Med 2022, 45, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, L.P.; et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021, 76, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; et al. Diabetes and Frailty: A Bidirectional Relationship. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrano, D.L.; et al. Multimorbidity and Frailty: A Systematic Review. Lancet Healthy Longev 2020, 1, e37–e46. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, M.; et al. Physical Frailty: Key Considerations for Clinical Practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 721–728. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; et al. Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Health in Older Adults. Annu Rev Public Health 2023, 44, 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; et al. Social Connection as a Public Health Priority. Am Psychol 2021, 76, 717–729. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, S.; et al. Loneliness and Health: Emerging Evidence and Therapeutic Implications. Perspect Psychol Sci 2020, 15, 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, L.; et al. Diabetes Distress and Loneliness in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022, 189, 109945. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; et al. Social Support and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Psychol Rev 2021, 15, 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, B.N.; et al. Social Support and Aging: A Meta-Analytic Perspective. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.J.; et al. Interplay Between Social Isolation and Frailty in Older Adults. Aging Ment Health 2022, 26, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D.; et al. Marital Status and Mortality in Older Adults. J Health Soc Behav 2021, 62, 377–393. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baker, D.P.; et al. Health Literacy and Self-Management in Chronic Disease. Patient Educ Couns 2020, 103, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.; et al. Socioeconomic Status and Health: The Role of Social Determinants. Lancet 2020, 396, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers, B.D.; et al. Health Insurance Coverage and Health Outcomes in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.J.; et al. Inflammation and social experience: An inflammatory challenge induces social withdrawal and depression-like behaviour in mice. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 106, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; et al. Synergistic effects of metabolic dysregulation and social isolation on frailty progression in older adults with diabetes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2023, 78, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar]

- van Son, J.; et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for diabetes distress: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med 2023, 85, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Smart elderly care in China: IoT-based solutions for chronic disease management. Lancet Digit Health 2023, 5, e348–e357. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Digital health ecosystems for aging populations: A systematic review of social connectivity interventions. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25, e45921. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; et al. Enhancing eHealth literacy through storytelling: Mobile app development for older adults with diabetes. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e41245. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Integrated care for older people: Guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity. Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; et al. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for geriatric decline: A meta-analytic review. Lancet Healthy Longev 2023, 4, e136–e146. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.E.; et al. Socioeconomic disparities in frailty: Pathways and policy implications. J Gerontol Soc Sci 2022, 77, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, L.C.; et al. Epigenetic Aging Mediates the Association Between Loneliness and Frailty. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13782. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, Z.I.; et al. Digital Platforms for Reducing Social Isolation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment Health 2021, 8, e27487. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; et al. Inflammation as a Mediator of Loneliness-Health Associations. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 105, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, M.; et al. Causal Inference in Mediation Analysis: Longitudinal Approaches. Am J Epidemiol 2023, 192, 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.E.; et al. Loneliness and epigenetic aging: A prospective analysis in older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 147, 105934. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, T.J.; et al. Wearable-Driven Biofeedback for Loneliness Reduction. npj Digit Med 2022, 5, 89. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Steptoe, A.; et al. Health Behavior Adherence as a Pathway from Social Isolation to Frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2023, 78, 825–833. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. The Dynamic Interplay Between Loneliness and Physical Decline. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 72, 101480. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; et al. Threshold Effects of Social Resources on Health Outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2023, 320, 115732. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Mediator of Social Isolation-Induced Frailty. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14035. [Google Scholar]

- Shiovitz-Ezra, S.; et al. Behavioral Pathways from Loneliness to Physical Decline. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2022, 77, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, C.M.; et al. Targeted Social Prescribing for Frailty Prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023, 71, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P.A.; et al. The Paradox of Excessive Social Support. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 353–361. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, O.P.; et al. Digital Phenotyping of Social Interactions for Frailty Risk Prediction. npj Digit Med 2024, 7, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D.; et al. Three-Dimensional Optimization of Social Support. Health Psychol Rev 2023, 17, 256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, E.M.; et al. Stepped-Wedge Trials for Social Intervention Research. Am J Public Health 2022, 112, S893–S901. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Filial Piety and Health Support Thresholds in Asian Families. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2024, 44, 100987. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Frailty prevalence and risk factors in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2020, 24, 621–627. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; et al. Social resource accumulation–health benefit inflection point: A theoretical framework for aging research. Gerontology 2021, 67, 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D.; et al. Three-dimensional support optimization model: Integrating social networks, functionality, and emotional resonance. Soc Sci Med 2022, 298, 114876. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.; et al. Stepped-wedge designs for evaluating threshold-defined interventions in geriatric populations. J Clin Epidemiol 2023, 155, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).