1. Introduction

Coastal zones are among the most densely populated and economically vital regions globally, yet they remain acutely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly sea-level rise (

SLR) (e.g., [

1,

2]). The Spanish Mediterranean coast, especially Catalonia and the Valencian Community, exemplifies this vulnerability. These regions combine high demographic pressure, intensive tourism, critical infrastructure, and environmentally sensitive systems, such as the Ebro Delta and the Albufera Natural Park, often situated at or near current sea level and exposed to wave overtopping [

3,

4,

5].

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (

IPCC) projects that global mean sea levels may rise by 0.26–0.82 m by 2081–2100 relative to 1986–2005 under different Representative Concentration Pathways (

RCP) scenarios [

6]. However, when compounded by regional factors, such as wave climate, storm surges, and wave-induced setup,

SLR in low-lying coastal lacustrine areas or deltaic systems may exceed these bounds.

The Mediterranean is recognized as a coastal hotspot due to its semi-enclosed geometry, limited tidal range, and accelerated relative

SLR, which may exceed global averages by ~25% [

7]. In response, [

8] proposed coastal adaptation pathways tailored to Mediterranean conditions, combining engineering and nature-based solutions to prevent irreversible tipping points.

Low-lying coastal areas, especially deltaic systems, are disproportionately threatened by

SLR not only due to their elevation but also because of ongoing land subsidence. This subsidence, driven by both natural processes (e.g., sediment compaction, tectonics) and anthropogenic activities (e.g., groundwater extraction, infrastructure loading), can amplify relative

SLR by up to two orders of magnitude compared to global averages [

9]. As a result, deltas such as the Ebro are experiencing effective

SLR rates far exceeding eustatic trends, increasing their exposure to permanent inundation, aquifer salinization, and infrastructure degradation [

10]. Moreover, comparative analyses of global deltas show that vulnerability—measured in terms of land loss and population at risk—is strongly correlated with subsidence, storm surge height, and delta area, rather than with

SLR alone [

11].

Recent research by [

12] further emphasizes the growing risk of permanent inundation in Mediterranean urban coastal zones. Their study introduces a high-resolution operational hydrodynamic forecasting system for beaches in Barcelona, demonstrating that the combined effects of storm events and rising mean sea levels can lead to severe impacts, even during short-duration episodes, highlighting the importance of predictive tools and frequent updates to topobathymetric data to maintain flood forecasting accuracy [

13]. These findings reinforce the notion that

SLR not only increases the frequency of extreme events but also contributes to a growing risk of chronic and irreversible coastal flooding.

Studies on the Valencian coast have shown that urbanized beach segments lacking dunes or natural barriers display significantly higher vulnerability, especially when assessed using integrated Coastal Vulnerability Indices (

CVIs) that account for geomorphology, wave exposure, and anthropogenic pressures. [

1] applied a hybrid pseudo-dynamic flood modeling approach along the Catalan coast, combining static inundation with habitat conversion analysis. Their findings underscore the pivotal role of local topography and land use in determining exposure and resilience, with natural systems occasionally acting as effective buffers.

Despite growing media attention, spatially explicit, regionally focused analyses along the Mediterranean coast between l’Estartit (Girona) and Cullera (Valencia) remain scarce. Previous work using digital elevation models (DEM) and static bathymetric flood modeling under SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, +3 m) has simulated potential territorial impacts, but often lacks integrated vulnerability assessment.

In this study, the selected study area extends ~480 km of Mediterranean coastline from l’Estartit to Cullera (Figure 1), covering both Catalonia and Valencia. The region features diverse coastal landforms like deltas, wetlands, urbanized beaches, industrial ports, and natural parks, and is characterized by high socio-economic intensity and ecological sensitivity, making it a representative testbed for Mediterranean coastal vulnerability.

To address this, the study proposes a three-tiered methodology that is transparent, replicable, and suitable for data-scarce scenarios by:

Quantifying coastal inundation areas under +1, +2, and +3 m SLR using static bathub-style flood maps derived from Google Earth’s Firetree;

Evaluating the sensitivity of inundation estimates by testing image resolution and pixel-alignment effects;

Applying a geometric Geomorphological Coastal Flooding Index (GCFI) based on normalized width, length, and flooded area indicators, developed to classify inundated zones by shape, inland penetration, and surface impact.

This integrative approach identifies critical exposure hotspots and provides preliminary estimates of economic loss, particularly through beach area contraction and its implications for tourism revenue, and is designed for general applicability in coastal planning contexts. This approach aligns with the recent study by [

14], which successfully applied a similar protocol to Amazonian barrier beaches, using multi-indicator vulnerability indices for shoreline erosion assessment. This work builds upon that paradigm by explicitly integrating image-based uncertainty analysis and geometric vulnerability metrics, thereby reinforcing the robustness and transparency of coastal

SLR impact assessments.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the datasets, image-processing workflows, and analytical procedures for calculating the permanent flooded area and the GCFI. Section 3 presents results: SLR-based inundation quantification (3.1), followed by resolution sensitivity (3.3), uncertainty estimation (3.3), the GCFI vulnerability indexing (3.4). Section 3.5 offers a comparative review of vulnerability across sites. Finally, Sections 4 - 5 discuss findings and conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inundation Mapping and Image Acquisition

Flood simulation images were obtained from the public web-based tool flood.firetree.net, which is based on the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (NASA's SRTM) elevation data. This tool allows visualization of coastal inundation resulting from SLR scenarios, in 1-meter increments from 0 to 60 meters above mean sea level. For this study, images were captured for SLR scenarios of +1 m, +2 m, and +3 m, with the 0 m scenario used as the baseline reference.

Images were downloaded in bitmap (

BMP) format, ensuring lossless compression, and cropped to a standardized extent of 1349×566 pixels [px] across all study areas to maintain spatial comparability. Three spatial resolutions were analyzed by capturing the same zones at different map zoom levels, corresponding approximately to 5×5 km, 2×2 km, and 0.5×0.5 km fields of view. The spatial resolution (in meters per pixel) was determined for each image using on-screen scale bars provided in the simulator, allowing conversion from pixels to area in square kilometers (see

Table 1).

2.2. Image Processing and Flooded Area Calculation

The method involves automated image differencing and thresholding to isolate newly inundated areas at each SLR increment. The steps were as follows:

Preprocessing: Each BMP image downloaded from the simulator includes a wide map area, often containing zones not relevant to the specific coastal site under study. To address this, each image was cropped to extract only the area of interest. This was done using matrix slicing, which selects a specific portion of the image matrix based on pixel coordinates. This step ensures that all images corresponding to a given site (0 m, +1 m, +2 m, +3 m scenarios) have the same spatial extent and alignment, enabling accurate pixel-by-pixel comparisons. After cropping, all images were converted to grayscale using MATLAB’s rgb2gray function. This transformation simplifies the image to a single intensity channel ranging from 0 (black) to 255 (white), which is sufficient to distinguish flooded (dark blue) zones from land. The resulting grayscale image serves as the basis for binarization and flood detection.

Binary classification: Inundated areas are represented by dark blue tones in the original images. Grayscale pixel thresholds were empirically determined (typically <50 on a 0–255 scale) to binarize each image into flooded (value = 1) and non-flooded (value = 0) zones. This classification was applied to each sea level scenario (0 m, +1 m, +2 m, +3 m).

Differencing: Binary images for each scenario were subtracted pairwise to calculate new inundation extent per meter of SLR (e.g. A = Flood1m - Flood0m, where matrix A highlights all pixels newly inundated at +1 m SLR). This was repeated for +2 m and +3 m scenarios. Only positive values were retained.

Pixel counting and area conversion: For each difference matrix, the number of flooded pixels was computed. This count was then converted to square kilometers using the specific pixel-to-area ratio derived for each resolution (based on known scale distances). For example, if 62 pixels represented 500 m² on-screen, one pixel corresponds to ~64.5 m².

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis and Error Estimation

A dedicated sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of image resolution on flooded area estimates. Each zone was analyzed at three spatial scales (low, medium, and high resolution), and the flooded area was calculated as described above. The results were then compared across resolutions for each sea level increment, enabling: i) Quantification of the variation in estimated flooded area due to image scale; ii) Evaluation of stability and robustness of the pixel-count method under different spatial granularities.

In addition, a tolerance-based error analysis was implemented. Given that the exact pixel classification (flooded vs. non-flooded) may be sensitive to boundary conditions or visual artifacts, a ±5-pixel buffer was applied to the flood boundaries to evaluate the upper and lower bounds of inundated area. This approach mimics the uncertainty introduced by manual cropping, low-resolution raster artifacts, or ambiguous terrain elevations near 0 m.

The absolute and relative differences in flooded areas under these variations were recorded and are presented in the Results section, along with an estimation of uncertainty per site and per inundation scenario (see Table 4).

2.4. Geomorphological Coastal Flooding Index

To translate geometric inundation patterns into a comparative indicator of coastal risk, a Geomorphological

GCFI was developed. This index integrates i) the relative measure of the mean width of the inundated strip, parallel to the shoreline divided by the shoreline length (

l); ii) the relative measure of the mean inland reach or length of inundation, perpendicular to the shoreline divided by the shoreline length (

w); iii) the flooded area (

a) by

SLR divided by the area of the affected municipality. The

GCFI (eq. 1) was calculated as:

These parameters were derived from the image analysis for each site and

SLR scenario. The values of

l and

w are ranged on a 1–4 scale according to defined percentages [<25%; 25-49%; 50-74%; >75%]. Then, the values of

a are ranged on a 1–4 scale according to defined percentages [<5%; 5-10%; 10-20%; >20%], with higher scores indicating greater vulnerability. Final

GCFI values were grouped into four classes according to the scores as follows: 1) Low vulnerability [1.0-1.5], Moderate vulnerability [1.5-2.0], High vulnerability [2.0-3.0], Very high vulnerability [3.0-4.0]. This simplified yet quantitative index enables the integration of spatial descriptors into a synthetic vulnerability score. The use of relative indicators ensures comparability across regions with different absolute sizes, highlighting the influence of geometric configuration rather than only the magnitude of flooding and facilitating spatial comparison among zones, relying solely on planform attributes extracted from freely available elevation-based flood visualizations and highlighting those requiring urgent attention of mitigation planning. This

GCFI approach aligns with existing vulnerability frameworks that use geometric or spatial descriptors to assess coastal exposure (e.g., [

15,

16]). Unlike multi-parameter indices that integrate geomorphological, hydrodynamic, and socioeconomic variables, this formulation focuses exclusively on the physical shape and size of the floodplain, offering a simple yet informative indicator that can be consistently applied across diverse coastal settings.

In this context, the study introduces a novel, pixel-based framework for static flood mapping that enhances traditional “bathtub” methodologies by integrating resolution sensitivity and a GCFI alongside the conventional CVI by combining static flood mapping, uncertainty analysis, and geometric vulnerability indicators into a single, replicable workflow. Unlike standard geographic information systems models, which often depend heavily on detailed DEMs and dynamic modeling tools, our approach leverages publicly available satellite imagery and simple pixel-subtraction routines to deliver high-resolution inundation analysis with minimal computational demand, operable on a standard personal computer. While improved “bathtub” methods require complex data and heavy processing, our pipeline maintains simplicity and scalability, offering a robust first-order exposure assessment even in data- and resource-scarce regions.

2.5. Study Sites

Nine coastal sites along the Spanish Mediterranean coast were selected for analysis based on their topographic vulnerability, morphological characteristics, and socio-environmental relevance (

Figure 1). The selection aimed to represent a variety of geomorphological settings that are particularly sensitive to

SLR, including deltas (and their adjacent areas, where the terrain is very flat and sediment supply is limited), coastal lagoons, and low-lying urbanized zones. These latter areas make up a significant portion of the study region, corresponding to tourist beaches or urban coastal strips with high economic value linked to recreational use and infrastructure. The sites were also chosen due to the availability of clear inundation imagery on the

flood.firetree.net platform, as well as their importance for coastal management and conservation planning. Together, this set of study areas offers a representative sample of Mediterranean coastal typologies, encompassing both natural systems and urban landscapes. This is especially relevant for evaluating the performance of low-cost, image-based flood models and their applicability in early-stage coastal planning under climate change scenarios. The selected sites include (from north to south):

L’Estartit: A coastal area known for its low cliffs, rocky coves with coarse sand, and proximity to flatlands and restored wetlands. It forms part of a diverse natural landscape within the Montgrí, Medes Islands and Baix Ter Natural Park.

Tordera Delta (Catalonia): A small but dynamic deltaic area at the northern fringe of the Barcelona province, featuring a narrow beach backed by low-lying agricultural and urban land.

Llobregat Delta (Catalonia): Located immediately southwest of Barcelona, this delta contains important infrastructure (e.g., the airport), nature reserves, and urban expansion zones, all within a few meters of mean sea level.

South Tarragona Coast (Catalonia): Includes suburban and semi-natural areas with varying degrees of artificial protection (seawalls, dunes), allowing assessment of contrasting response types.

Ebro Delta (Catalonia): One of the most prominent and vulnerable deltas in the western Mediterranean, with large expanses of land at or below current sea level. It is subject to sediment deficit, subsidence, and high exposure to SLR-induced permanent inundation.

Prat de Cabanes-Torreblanca (Valencia): A natural park with shallow wetlands and marshes, acting as a buffer zone for marine ingress but extremely sensitive to even minor sea level increases due to its flat topography.

Castellón de la Plana (Valencia): An urbanized section of the Valencian coast with artificialized beaches, where both the built environment and infrastructure are potentially at risk from permanent flooding.

Sagunto Coastline (Valencia): Combines residential, industrial, and natural areas; features low topography and modified shorelines, increasing exposure to marine transgression.

Albufera de Valencia (Valencia): A coastal lagoon and wetland system of high ecological value, protected under the Ramsar Convention and Natura 2000 network. It is surrounded by rice fields and low-lying rural settlements, with very limited natural protection from the sea.

Each site was analyzed independently at three spatial resolutions, and flooded areas were calculated for +1 m, +2 m, and +3 m SLR scenarios. The resulting vulnerability assessments allow for inter-site comparison, sensitivity analysis, and ranking of risk levels across this diverse coastal transect.

2.6. Data and Code Availability

All source images were obtained from flood.firetree.net, a publicly accessible tool that does not require registration or login. The MATLAB code developed for processing the images, extracting flooded areas, and computing the GCFI is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The analysis can be fully replicated using public tools and the methodological framework provided in this manuscript.

3. Results

This section presents the outcomes derived from the application of the proposed methodology for estimating coastal inundation under progressive SLR scenarios, as well as the assessment of vulnerability levels across the selected coastal zones. The structure of the results follows the logical sequence of the methods, aiming to facilitate interpretation and highlight the robustness and scalability of the approach. Initially, the total flooded areas associated with +1 m, +2 m, and +3 m SLR increments are reported and compared across all case study sites. These estimations are then evaluated through a sensitivity analysis focused on the influence of spatial resolution, examining how image scale affects the calculation of inundated areas. An uncertainty analysis is also included, based on pixel boundary tolerance, to quantify potential variability in the results due to minor image shifts or classification ambiguities.

Subsequent sections present the computation of the GCFI, which incorporates geometric characteristics of inundation to generate a standardized risk indicator. Finally, a comparative ranking of the sites is provided to synthesize vulnerability levels and support further interpretation of spatial patterns and model performance.

3.1. Flooded Area Estimation Under SLR Scenarios

Table 1. m, +2 m, and +3 m. The total flooded areas were extracted from the binarized difference of satellite-derived images, as described in the methodology, and converted to surface area (km²) using calibrated image resolution factors (as detailed in

Table 1). To illustrate the methodology applied in this study, a representative case is presented for the Ebro Delta.

Figure 2 shows the sequence of flood extent visualizations corresponding to

SLR scenarios of 0 m, +1 m, +2 m, and +3 m. (extracted from the Firetree global flood map) and converted to grayscale in order to enable pixel-based processing. The grayscale transformation facilitates the numerical comparison between successive inundation stages. Specifically, image subtraction operations were performed to compute the incremental changes in flood extent between consecutive

SLR scenarios, that is: (b–a), (c–b), and (d–c), corresponding respectively to the increase in inundation from 0 m to +1 m, +1 m to +2 m, and +2 m to +3 m. This process enabled a direct estimation of the area increment and spatial configuration of newly inundated zones for each

SLR threshold.

This approach enabled the identification of spatial patterns of flooding across the diverse geomorphological features of each of the nine study sites. Flood extent (

Table 2), of the total area flooded for each site and scenario demonstrate a clear and consistent increase in inundated surface as

SLRs, with considerable spatial variability across the selected coastal systems.

Among all sites, the Ebro Delta exhibits the most extensive floodplain, with 277.167 km² inundated at +1 m

SLR, increasing to 295.753 km² at +2 m, and reaching 304.544 km² at +3 m. This behavior reflects the high exposure of this deltaic environment, characterized by minimal elevation gradients, ongoing subsidence, and extensive wetland and agricultural areas. The Albufera de Valencia ranks second in total inundated area, with flooding expanding from 156.805 km² at +1 m to 183.952 km² at +2 m and 206.301km

2 at +3m. This sharp increase underscores the vulnerability of lagoonal systems with low-lying margins and artificially maintained water levels. Similar progressive trends were observed in other Spanish locations such as the Doñana wetlands [

17], the Albufera de Valencia [

18] and the Mar Menor [

19].

Intermediate values are observed in the coastline of Valencia (Sagunto, Castellón de la Plana) and urban deltaic systems in Catalonia (Llobregat Delta and L'Estartit), where flood extent is constrained by topographic variation and anthropogenic modifications.

These results are consistent with existing projections in the scientific literature, which demonstrate that low-lying coastal regions, especially deltas, lagoons, and estuarine plains, are highly susceptible to even modest increases in sea level [

20,

21]. Studies using

DEMs and hydrodynamic models have similarly found that +1 to +3 m

SLR can cause extensive permanent inundation in many Mediterranean and subtropical coastlines [

22,

23]. The pixel-based method employed here offers a simplified but effective means of replicating such projections using readily accessible geospatial imagery, albeit with less vertical precision.

The variation in flooded area among sites also reflects local geomorphology and coastal slope. Regions with flatter topography (such as the Ebro Delta or the Albufera), are more prone to extensive horizontal transgression of floodwaters, whereas steeper coastlines display more limited inundation. This confirms prior research highlighting the influence of topographic slope and elevation gradients on

SLR-driven exposure [

24,

25]. These factors must be carefully considered in coastal planning, as they modulate the spatial distribution of risk and the potential for ecosystem or infrastructure loss.

3.2. Sensitivity to Spatial Resolution

The accuracy of flood extent estimation based on image analysis is highly sensitive to the spatial resolution of the input data. This section examines how different map resolutions influence flood extent estimations by comparing the resolutions used in this study: a finer resolution (500 m) and a coarser resolution (2 km). Pixel-to-area conversion factors, derived from the values in

Table 1, were applied to translate the number of inundated pixels into flooded surface area (km²) for each

SLR scenario.

The results of the total flooded area for each scenario (+1 m, +2 m, +3 m

SLR) is summarized in

Table 3. Across all cases, there is a consistent overestimation of the flooded area when using the coarser-resolution map. For example:

Under +1 m SLR, the flooded area was 528.72 km² using the 500 m map, compared to 562.08 km² with the 2 km map, representing a relative overestimation of 6.3%.

Under +2 m SLR, the respective values were 713.31 km² and 736.32 km², corresponding to a difference of 3.2%.

Under +3 m SLR, the overestimation reached 3.1%, with areas of 846.76 km² (500 m) and 873.15 km² (2 km).

This outcome is consistent with prior research. Several authors have documented that coarser-resolution

DEMs tend to overestimate flood extents because they smooth out microtopographic barriers that would otherwise confine floodwaters in finer-scale models [

26,

27]. In such cases, the pixel-scale representation allows partial flooding in a cell to be interpreted as full inundation, thus inflating the computed surface area [

28]. Furthermore, studies have shown that flood extent and water depth can vary linearly with

DEM resolution, emphasizing the importance of choosing an appropriate scale [

29].

The influence of resolution appears to be more significant under low SLR scenarios, where flooding affects narrow or discontinuous coastal strips. In these cases, fine-scale spatial detail is essential to accurately capture the extent and shape of inundated zones. As the SLR scenario increases, the flooded areas expand, and differences between resolutions diminish in relative terms, although they remain relevant in absolute area.

While high-resolution data generally improve flood extent prediction accuracy, they also impose greater computational costs and data storage requirements [

30]. For large-scale assessments, the trade-off between spatial detail and efficiency becomes critical. Coarse-resolution datasets may be acceptable for regional risk screening but are inadequate for site-specific vulnerability mapping or infrastructure planning, where small-scale features significantly influence flood pathways and exposure patterns [

31].

Moreover, vertical accuracy also plays a key role. Global elevation datasets such as

NASAs SRTM, despite their relatively high horizontal resolution (~30 m), have known vertical biases in vegetated or urban areas. These biases can lead to significant underestimation of the population and assets at risk, as demonstrated by [

25], who found that

SRTM-based assessments omitted up to 60% of the exposed population in some U.S. states when compared to high-accuracy Light Detection And Ranging (

LiDAR) based models.

To complement the resolution analysis, a pixel tolerance evaluation was conducted by introducing a buffer of ±5 pixels to simulate spatial uncertainty had minimal impact on the total flooded area—less than 1% deviation across all SLR levels. This result suggests that the method used is robust to minor positional shifts, and confirms that the primary source of sensitivity in this analysis is the spatial resolution rather than the edge tolerance.

In summary, the spatial resolution of flood mapping inputs exerts a measurable and systematic influence on inundation estimates. Coarser data tend to overestimate flooded areas due to generalized representation of terrain and loss of microtopographic control. These biases must be explicitly considered when applying image-based methods to coastal vulnerability studies. For accurate and policy-relevant results, the selection of spatial scale should match the intended use, with high-resolution inputs favored for localized impact assessments and adaptation planning.

3.3. Uncertainty Estimation from Image Tolerance

In addition to spatial resolution, the reliability of flooded area estimations may be affected by image classification thresholds, pixel alignment, and edge detection variability. To evaluate the robustness of the method, a pixel tolerance test was conducted by comparing inundation estimates under two scenarios: a strict classification threshold (0-pixel tolerance) and a relaxed one allowing ±5-pixel margin around flood boundaries. This approach simulates minor shifts in segmentation or classification errors that may arise from image preprocessing or resolution-induced artifacts (see

Table 4).

The results indicate that pixel tolerance had a negligible effect on overall flooded area estimates across all

SLR scenarios. Differences between 0-pixel and 5-pixel tolerance configurations were below 1.2% for all cases, confirming the robustness of the method. These findings are in agreement with prior studies that evaluated the sensitivity of raster-based flood mapping to positional uncertainty and segmentation thresholds. For instance, [

30] showed that horizontal spatial uncertainty in coarse

DEMs had a limited impact on total inundation extent in large-scale coastal regions, although effects could be locally significant. Similarly, [

32] found that uncertainty due to vertical and horizontal positioning is often overshadowed by other factors such as elevation error or hydrodynamic variability.

3.4. Geomorphological Coastal Flooding Index

To synthesize the results of the flooding scenarios into a unified vulnerability metric, the proposed GCFI is computed according to Equation (1), which relates the flooded area, the geometrical complexity of the flood footprint, and the SLR through a normalized ratio.

This formulation is consistent with approaches that prioritize simplicity, transparency, and replicability in spatial vulnerability assessments (e.g.[

16,

33]). By integrating both the extent and configuration of the flooded surface, this index captures both the magnitude of potential impacts and their spatial morphology, which is an important factor for risk perception and for the design of adaptive management policies. All variables were normalized to allow comparison across case studies, regardless of their absolute size. The resulting

GCFI values, computed for each

SLR scenario (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m), are summarized comparatively in

Figure 3.

According to the

GCFI results, the Ebro Delta consistently exhibits the highest vulnerability, reflecting its expansive and elongated inundation pattern under all

SLR scenarios. The Albufera de Valencia also shows very high values. The intermediate to low

GCFI corresponds to a more compact and spatially confined flood geometry, which is in line with previous coastal sensitivity studies highlighting the role of topographic setting, floodplain openness, and inland penetration in shaping flood exposure (e.g., [

34,

35]), indicating either greater perimeter length for a given area or a more fragmented and irregular flood zone, conditions typically associated with higher management complexity and exposure.

3.5. Comparative Ranking of Study Sites

This section presents a comparative summary of the results, focusing on both the GCFI and the flooded area under different SLR scenarios. These indicators are compared for the different study areas, highlighting the importance of the first meter of SLR, which in many cases has the greatest relative impact on the coast. Next, the behavior of the GCFI and the evolution of the flooded area are analyzed separately, emphasizing linear or non-linear flooding patterns with SLR, and regional differences (e.g., Ebro Delta vs. other areas) are discussed. Finally, the implications in terms of beach loss and tourism and the vulnerability of study are addressed.

3.5.1. Link Between SLR and Flooded Area

The results of modeling flood-prone areas under different

SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, +3 m) show different behaviors depending on the area, as illustrated in

Figure 4. In general, across the entire territory studied, the increase in flooded area due to

SLR behaves according to the general geomorphological features of the study sites. In some sites (e.g., L'Estartit, Llobregat Delta), each increase in level (from 0 to +1 m, from +1 to +2 m, etc.) adds a similar portion of flooded area. This linear trend suggests (with an approximately constant slope, indicating that there is no abrupt jump at the regional level) that, each additional meter of

SLR affects a comparable area of coastal land (at least within the 0–+3 m range evaluated) indicating that there is no abrupt jump at the regional level, but rather a progressive and sustained increase in the affected area as the sea rises.

However, when disaggregated by region or specific units, important non-linear patterns emerge (Tordera Delta, Ebro Delta, Cabanes, and Albufera). In some cases, the curve of flooded area vs. SLR is concave (decelerated), where the first meter floods more than the subsequent ones, until reaching a ceiling. Other curves show a slightly convex (accelerated) shape, indicating that additional SLR will flood proportionally more territory than the first meter.

This result shows that many low-lying coastal areas do indeed experience most of their increase in flooded area with the first meter of

SLR. This is the case for extensive deltas and marshes: for example, in the Ebro Delta, approximately 70% of its surface area is below +1 m above current sea level [

36], which means that a

SLR of one meter would put up to ~70% of the delta under water (assuming no protective measures are in place). This is reflected in

Figure 4, where the quantification for the Ebro shows that the first meter of elevation causes the flooding of most of the deltaic surface, while the subsequent

SLR floods additional smaller areas. In other words, the flooded area vs.

SLR curve for the Ebro Delta is concave, saturating quickly. Much of the territory is already affected at +1 m, and from ~+2 m onwards, the delta would be almost completely flooded (≥85–90% of its area). This result is consistent with previous assessments that characterize the Ebro Delta as an environment that is extremely vulnerable to small changes in sea level due to its topography. [

36] estimated that in a scenario of +88 cm by 2100 (AR4 high scenario), up to 61% of the delta could be affected. In fact, detailed calculations indicate that ~50% of the Ebro Delta is below +0.5 m and ~70% below +1 m, which explains the enormous sensitivity to the first meter of

SLR.

Figure 4 clearly shows this concentration of land loss in the first decimeters/meter of elevation. Another notable case is that of the Albufera de Valencia, which includes a shallow coastal lagoon (average depth ~+1 m) surrounded by ~223 km² of very low-lying rice fields, separated from the open sea by a narrow sandy dune cordon. The results show that the first meter of

SLR would be the most damaging for land loss in the Albufera basin. Thus,

Figure 4 suggests a similar concave response, where much of the land loss occurs within the first meter, leaving less additional territory to be lost with subsequent increases (which probably already involve the almost complete flooding of the interior wetland). This highlights the vulnerability of coastal wetlands such as La Albufera, whose current equilibrium depends on a narrow separation from the sea, and even a small rise in sea level can upset this balance and turn large areas of land into permanently flooded expanses.

Similarly, other coastal regions that are smaller in size but low in altitude reflect the same phenomenon. The Cabanes area, for example, has a much smaller flood zone than the Ebro Delta, yet the first

SLR meter causes the greatest percentage impact in loss territory. Although in absolute terms the affected area is smaller, in relative terms the initial +1 m covers the most significant portion of vulnerable land, with subsequent more modest increases in flooded area with higher

SLR. This behavior is consistent with the idea that in flat areas, much of the land is just above the current sea level, so a small rise quickly turns it into intertidal or subtidal areas [

36]. On the other hand, once these large low-lying areas are flooded, the land remaining at slightly higher elevations occupies less surface area (often the higher “shores” or land that begins to rise), so that each additional meter covers fewer new flooded areas.

On the other hand, there are areas where the relationship is not concave but convex, indicating the presence of some topographical or structural threshold that limits the impact of the first meter but gives way to higher rises. The Tordera Delta is a case in point: there, the first meter is not as damaging as the next two. This suggests that at +1 m, many parts of that area are not yet significantly flooded, but once a certain critical level (between 1 and +2 m) is exceeded, water penetrates inland, flooding large areas at once. In cases like this, with +1 m only ~15% of the area is flooded, but with +2 m this increases to ~52% and with +3 m to over 95% (convex response pattern). This stepped behavior would indicate that current natural or artificial defences may be effective against modest increases in mean sea level, but would not prevent severe flooding in higher elevation scenarios. This flooding pattern is indicative of coastal areas that initially resist, but eventually the water overcomes them when the level rises high enough.

Finally, the case studies with more linear behavior (Delta del Llobrega, Tarragona, Castellón, and Sagunto) correspond to areas where the topography has a fairly uniform slope inland, so that each increase in level covers a similar strip of land. In these cases, there is neither a disproportionate effect of the first meter nor a marked threshold thereafter; simply an approximately constant increase in the flooded area for each meter of SLR is observed. This pattern is common on slightly higher coasts or coastal plains of limited width, where the distribution of heights is approximately homogeneous. For example, an open beach with a low backwash and a constant slope could experience a loss of beach/land area that is almost proportional to the rise in sea level (which, in the absence of abrupt barriers inland, show very linear relationships between SLR and flooded area in other sections). This means that for these areas, the impact of the second and third meters is as significant as that of the first in terms of new flooded area, with a regular-sustained progression.

In summary, the impact of the first meter of

SLR varies by region. In relative terms, ultra-low-lying coastal areas (deltas, coastal lagoons) suffer most of the potential flooding already at +1 m (first “worst” or most critical meter). In contrast, in areas with dunes or urban/protective structures, the first meter may cause relatively little additional damage until the threshold is exceeded (first meter “benign” compared to the following ones). On the scale of the entire coastline studied, the behavior is more convex because the Albufera and the Ebro Delta represent by far the largest part of the affected territory, compared to the rest, and show this convex (slowed) behavior, so that overall, the first meter of

SLR represents a significant percentage of the total area lost. In fact, according to [

37], globally, many of the exposed coastal areas and populations are concentrated at very low elevations; for example, in some Caribbean Island countries, more than 70% of the low-lying coastal population lives below +1 m, which means that the first meter of

SLR would put the majority at risk. In this study, this phenomenon is manifested territorially:

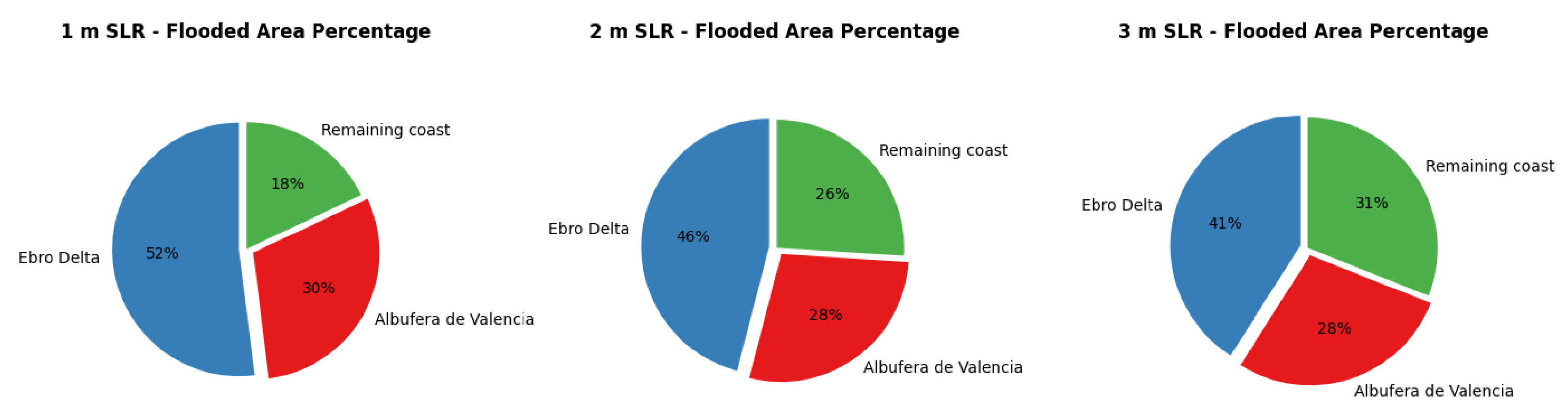

Figure 5 shows the contribution of each sub-region to the total loss of territory under different scenarios, showing that the Ebro Delta contributes the largest part of the flooded area in all scenarios (due to its large size and low elevation), followed in importance by other areas such as the Albufera de Valencia, etc.

In other words, regardless of whether +1 m, +2 m or +3 m is considered, the largest fraction of land lost corresponds to the Ebro Delta (for example, under +1 m it would represent around half of the total flooded area, adding up all the areas, and under +3 m it would still be the largest individual percentage). This emphasizes that wide and low-lying deltas dominate the absolute territorial risk.

Figure 5 highlights this, with the Ebro leading the way in all the scenarios evaluated.

3.5.2. GCFI Calculation

The

GCFI results allow coastal sections with different degrees of vulnerability (very low, low, moderate, high, very high) to be identified. By quantifying the total study area (

Figure 3), most of the coastline assessed is moderately to highly vulnerable. In general, low-lying and sedimentary coastal areas (deltas, marshes, coastal lagoons) have high or very high

GCFI values. For example, the Ebro Delta stands out with a high

GCFI in the global classification of the coast (it is one of the most vulnerable areas of the Catalan coast) due to its flat topography and low altitude. Other flat coastal areas, such as the coastal lagoon of the Albufera de Valencia or the Llobregat delta, also have high

GCFI scores, confirming their high physical susceptibility. This characterization using

GCFI provides a basis for understanding where the potential impact of

SLR would be greatest from a physical standpoint [

38].

4. Discussion

This study presents a robust and accessible methodology for estimating flooded areas and deriving CVIs based on publicly available satellite data and pixel-level analysis. The findings from the selected Mediterranean study sites demonstrate both spatial variability in flood exposure and methodological sensitivity to resolution and image tolerance. These observations invite several interpretative considerations regarding the utility, applicability, and limitations of the proposed approach.

One of the key insights derived from the analysis is the nonlinear response of coastal systems to

SLR. In particular, the results consistently show that the first meter of

SLR produces the most substantial changes in flooded area across all case studies, as illustrated in Figure

4, particularly for the Ebro Delta, Albufera de Valencia, and Cabanes. This behavior reinforces the conclusion that early adaptation efforts should prioritize thresholds below +1 m

SLR, since later increments exhibit more moderate additional impacts. These findings are consistent with previous research emphasizing the disproportionate impact of initial inundation in low-lying areas (e.g., [

2,

39,

40]).

Furthermore, although the analysis was based on a static flood model, without accounting for dynamic processes such as wave run-up, storm surge, or evolving coastal defenses, the methodology yields a robust first-order approximation of potential long-term impacts. Similar "bathtub" models have been widely used in regional-scale assessments with limited hydrodynamic data availability [

41,

42], serving as practical baselines for prioritizing adaptation strategies. The observed non-linear increase in inundated surface, particularly between the +1 m and +2 m

SLR scenarios, underscores the relevance of threshold dynamics in exposure escalation and supports the necessity of location-specific vulnerability analyses.

The sensitivity analysis demonstrates that higher-resolution imagery captures more detailed inundation patterns, enabling improved delineation of coastal features and more precise quantification of flooded areas. Unlike dynamic modeling approaches, which often require high-performance computing and complex calibration, the strength of the proposed method lies in its computational simplicity and operational efficiency. Even when applied at higher resolutions, the methodology remains lightweight: the only added requirement is the acquisition of a greater number of input images. The image processing, which is based on binary comparison and pixel subtraction, can be executed on standard personal computers using widely accessible tools such as MATLAB. As such, the proposed method offers an effective balance between accuracy and practicality, making it suitable for both large-scale assessments and applications in resource-limited contexts.

Although the pixel tolerance parameter had a minor effect on the outcomes, the testing performed confirms the robustness of the classification logic. This suggests that image resolution, rather than classification noise, remains the main contributor to uncertainty. Still, pixel tolerance assessments are a useful complementary procedure in confirming internal consistency and should be considered in analogous studies employing raster-based flood classification techniques.

The shape, orientation, and depth of flooded areas also emerge as decisive elements in characterizing coastal vulnerability. This behavior reinforces the importance of assessing not only the flooded area but also the geometric properties of the inundation zone, which can influence emergency accessibility, exposure gradients, and potential erosional dynamics. The proposed

GCFI offers an enhanced diagnostic lens to interpret not just magnitude but also the spatial footprint of permanent flooding, adding value to conventional

CVI approaches by enabling a more nuanced ranking of vulnerability under different

SLR scenarios (e.g., [

33,

43]).

The case of the Albufera de Valencia illustrates the compounding risks faced by low-lying agricultural wetlands. While a +1 m SLR under static conditions might not fully overtop the coastal barrier, the combination of this scenario with episodic storm surges could trigger catastrophic flooding. This emphasizes the need to account for compound hazards, particularly in rice-producing regions where saline intrusion and infrastructure vulnerability intersect under future climate conditions.

Furthermore, the socioeconomic implications of the spatial patterns observed merit attention. As detailed in

Section 2.5, a significant proportion of the inundated surface corresponds to tourist beaches or urbanized coastal strips with economic value tied to recreational use and infrastructure. Although not directly modeled in this study, the loss of beach width, erosion of foredunes, and saltwater intrusion into wetlands suggest potential economic losses for tourism, fisheries, and conservation initiatives. These insights support integrating the proposed methodology with land use data and economic impact modeling in future research.

Lastly, the limitations of the static bathtub model must be acknowledged. While suitable for preliminary SLR impact assessments, this method does not account for dynamic processes such as wave run-up, storm surge, sediment redistribution, or hydrodynamic feedback. Consequently, the model may overestimate flooding in some areas and underestimate it in others. Nonetheless, the simplicity and replicability of this approach make it a valuable first-order screening tool, especially when combined with participatory planning or scenario development for climate adaptation.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a reproducible and scalable methodology to assess coastal flood exposure under sea-level rise scenarios by leveraging Google-based elevation imagery and pixel-level comparison techniques. The approach relies on publicly accessible satellite data and basic image subtraction techniques, ensuring its replicability and utility across multiple spatial scales. The method allows the quantification of flooded areas under incremental SLR scenarios and provides a foundation for the calculation of a composite CVI enhanced by the introduction of a GCFI to evaluate vulnerability across diverse coastal settings.

Key conclusions include:

The heterogeneity of vulnerability along the Catalonia and Valencia coastlines, identifying deltas and lagoons as priority areas due to their large low-lying surfaces and rapid inundation progression where the first meter of SLR accounts for the majority of territorial loss, reinforcing the need for early adaptation strategies focused below this threshold;

The use of high-resolution imagery demonstrated that detailed flooding patterns and geomorphological features can be effectively captured without the need for intensive computational resources;

Resolution and image tolerance significantly affect inundation estimates, suggesting that methodological consistency is essential for comparative studies and long-term monitoring;

The shape and extent of the inundated areas provide meaningful information beyond surface area alone, particularly in identifying potential bottlenecks for emergency response or critical ecosystem exposure.

The proposed GCFI offers a cost-effective tool for vulnerability screening, particularly in regions lacking high-resolution dynamic models or detailed socioeconomic datasets.

The method is particularly suitable for preliminary coastal risk assessments and can support regional adaptation planning, land use zoning, and awareness-building initiatives. Future work should explore the integration of dynamic flood models, land use data, and economic impact layers to enhance the operational relevance of this approach.

In summary, this study presents an innovative and operationally efficient methodology that integrates static flood mapping, resolution-sensitivity analysis, and the GCFI within a unified, computationally lightweight framework. Despite inherent limitations (most notably, the exclusion of dynamic forcing mechanisms), its methodological simplicity and adaptability render it a valuable tool for coastal vulnerability assessment. The application of the GCFI facilitates the classification of coastal segments based on relative vulnerability, with areas of very high susceptibility typically corresponding to low-lying, geomorphologically flat environments such as deltas and coastal lagoons, whereas urbanized coastal zones generally exhibit lower vulnerability. This pixel-based approach enhances traditional assessment techniques that often rely on high-resolution DEMs and high-performance computing resources, offering a scalable and accurate alternative particularly suited for large-scale screening in data-scarce or resource-constrained contexts. Furthermore, the framework provides a robust basis for comparative analysis with SLR inundation scenarios, enabling verification of spatial risk manifestation and supporting the prioritization of adaptation strategies in the most exposed regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., M.V., A.S.A. and V.G.; methodology, C.M., A.S.A. and D.G.M.; software, M.V., C.A.; C.M.; validation, C.M., V.G., M.V. and D.G.M.; formal analysis, C.M. J.P.S and A.S.A.; investigation, C-M and M.V.; resources, D.G.M. and A.S.A.; data curation, C.M., M.V. and C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M., M.V., and J.P.S.; writing—review and editing, C.M., A.S.A. and J.P.S.; visualization, M.V., V.G.; supervision, A.S.A.; project administration, D.G.M. and A.S.A.; funding acquisition, A.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101037097 (REST-COAST project).

Data Availability Statement

Images are available at flood.firetree.net platform and codes will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of two major funded initiatives. First, the REST-COAST project (“Large-scale RESToration of COASTal ecosystems through rivers-to-sea connectivity”), coordinated by the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya and financed by the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme of the European Union (Grant Agreement No 101037097), which contributed with methodologies based on nature-based solutions, restorational simulations, and observational data for science-informed decision-making. Second, sincere thanks are extended to the BARRACLIM project (“Barraques Climàtiques per adaptar la costa i les seves activitats a condicions futures”), funded by the Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament d’Acció Climàtica, Alimentació i Agenda Rural (Reference No ACC_2023_EXP_SIA002_09_0001569). The authors also thank all REST-COAST and BARRACLIM partners and team members for their collaboration, insightful discussions, and data sharing, which were essential for developing and refining the methodological approach presented here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SLR |

Sea Level Rise |

| DEM |

Digital Elevation Model |

| GCFI |

Geomorphic Coastal Flooding Index |

| CVI |

Coastal Vulnerability Indices |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| RCP |

Representative Concentration Pathways |

| NASA's SRTM |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| BMP |

BitMaP |

| LiDAR |

Light Detection And Ranging |

References

- López-Dóriga, U.; Jiménez, J.A. Impact of Relative Sea-Level Rise on Low-Lying Coastal Areas of Catalonia, NW Mediterranean, Spain. Water (Basel) 2020, 12, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomelí-Quintero, V.-M.; Calderón-Vega, F.; Mösso, C.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; García-Soto, A.-D. Impact Costs Due to Climate Change along the Coasts of Catalonia. J Mar Sci Eng 2023, 11, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mösso, C.; Gracia, V.; Mestres, M.; Sierra, J.P.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Sediment Mobility at Fangar Bay Entrance (NW Spanish Mediterranean): Management Implications Under Present and Future Climates. J Coast Res 2020, 95, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; González-Marco, D.; Nos, R.B. A review of wave climate and prediction along the Spanish Mediterranean coast. 2008. [Online]. Available: www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci. 1217. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, J.P.; Casanovas, I.; Mösso, C.; Mestres, M.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Vulnerability of Catalan (NW Mediterranean) ports to wave overtopping due to different scenarios of sea level rise. Reg Environ Change 2016, 16, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, M.; Glavovic, B.C.; Hinkel, J.; van de Wal, R.; Magnan, A.K.; Abd-Elgawad, A.; Cai, R.; Cifuentes-Jara, M.; DeConto, R.M.; Ghosh, T.; Hay, J.; Isla, F.; Marzeion, B.; Meyssignac, B.; Sebesvari, Z. Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. in IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, H.-O., Pörtner, D. C., Roberts, V., Masson-Delmotte, P., Zhai, M., Tignor, E., Poloczanska, K., Mintenbeck, A., Alegría, M., Nicolai, A., Okem, J., Petzold, B., Rama, and N. M. Weyer, Eds., Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2019.

- Vacchi, M.; Joyse, K.M.; Kopp, R.E.; Marriner, N.; Kaniewski, D.; Rovere, A. Climate pacing of millennial sea-level change variability in the central and western Mediterranean. Nat Commun, 4013; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Gracia, V.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Coastal Adaptation Pathways and Tipping Points for Typical Mediterranean Beaches under Future Scenarios. J Mar Sci Eng 2024, 12, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.A. Review: Advances in delta-subsidence research using satellite methods. Hydrogeol J 2016, 24, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.; Lindsey, E.O.; Chin, S.T.; McCaughey, J.W.; Bekaert, D.; Nguyen, M.; Hua, H.; Manipon, G.; Karim, M.; Horton, B.P.; Li, T.; Hill, E.M. Sea-level rise from land subsidence in major coastal cities. Nat Sustain 2022, 5, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaat, J.E.; Eleveld, M.A. Divergent options to cope with vulnerability in subsiding deltas. Clim Change, 2013; 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Artús, X.; Gracia, V.; Espino, M.; Grifoll, M.; Simarro, G.; Guillén, J.; González, M.; Sanchez-Arcilla, A. Operational hydrodynamic service as a tool for coastal flood assessment. Ocean Science 2025, 21, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñes, M.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Epelde, I.; Mösso, C.; Franco, J.; Sospedra, J.; Abalia, A.; Líria, P.; Grifoll, M.; Ojanguren, A.; Hernáez, M.; González, M.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Morphodynamic predictions based on Machine Learning. Performance and limits for pocket beaches near the Bilbao port. Front Environ Sci, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.L.M.C.; Mösso, C.; Pereira, L.C.C. Assessment of Vulnerability to Erosion in Amazonian Beaches. Geographies 2025, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, E.A.; Theiler, E.R.; Williams, S.J. Coastal vulnerability assessment of Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CAHA) to sea-level rise. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V.M.; White, T.W.; Daniels, R.C. A Coastal Hazards Data Base for the US East Coast. Tennessee, United States, Aug. 1992. [Online]. Available: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1182892/.

- Díaz-Delgado, R.; Aragonés, D.; Afán, I.; Bustamante, J. Long-Term Monitoring of the Flooding Regime and Hydroperiod of Doñana Marshes with Landsat Time Series (1974–2014). Remote Sens (Basel) 2016, 8, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Papa, M.N.; Gargiulo, M.; Palau-Salvador, G.; Vezza, P.; Ruello, G. Continuous Monitoring of the Flooding Dynamics in the Albufera Wetland (Spain) by Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 Datasets. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.M.; Muñoz, R.; Campillo-Tamarit, N.; Molner, J.V. Flash-Flood-Induced Changes in the Hydrochemistry of the Albufera of Valencia Coastal Lagoon. Diversity (Basel) 2025, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Cazenave, A. Sea-Level Rise and Its Impact on Coastal Zones. Science (1979) 2010, 328, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, S.; Barnard, P.L.; Fletcher, C.H.; Frazer, N.; Erikson, L.; Storlazzi, C.D. Doubling of coastal flooding frequency within decades due to sea-level rise. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkel, J.; Lincke, D.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Perrette, M.; Nicholls, R.J.; Tol, R.S.J.; Marzeion, B.; Fettweis, X.; Ionescu, C.; Levermann, A. Coastal flood damage and adaptation costs under 21st century sea-level rise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 3292–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Mentaschi, L.; Voukouvalas, E.; Verlaan, M.; Jevrejeva, S.; Jackson, L.P.; Feyen, L. Global probabilistic projections of extreme sea levels show intensification of coastal flood hazard. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeidis, A.T.; Schuerch, M.; Wolff, C.; Spencer, T.; Merkens, J.L.; Hinkel, J.; Lincke, D.; Brown, S.; Nicholls, R.J. Water-level attenuation in global-scale assessments of exposure to coastal flooding: a sensitivity analysis. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2019, 19, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulp, S.; Strauss, B.H. Global DEM Errors Underpredict Coastal Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise and Flooding. Front Earth Sci (Lausanne), 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell, T.J.; Bates, P.D.; Horritt, M.; Hunter, N.M. Evaluating the effect of scale in flood inundation modelling in urban environments. Hydrol Process 2008, 22, 5107–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.T.S.; Bates, P.; Freer, J.; Neal, J.; Aronica, G. When does spatial resolution become spurious in probabilistic flood inundation predictions? Hydrol Process 2016, 30, 2014–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, H.; Sampson, C.C.; de Almeida, G.A.M.; Bates, P.D. Evaluating scale and roughness effects in urban flood modelling using terrestrial LIDAR data. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2013, 17, 4015–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.F. Evaluation of on-line DEMs for flood inundation modeling. Adv Water Resour 2007, 30, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, O.E.J.; Bates, P.D.; Smith, A.M.; Sampson, C.C.; Johnson, K.A.; Fargione, J.; Morefield, P. Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 034023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wong, D.W.S. Effects of DEM sources on hydrologic applications. Comput Environ Urban Syst 2010, 34, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, C.C.; Smith, A.M.; Bates, P.D.; Neal, J.C.; Alfieri, L.; Freer, J.E. A high-resolution global flood hazard model. Water Resour Res 2015, 51, 7358–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieler, E.R.; Hammar-Klose, E.S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise: Preliminary results for the U. S. Pacific Coast. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Torresan, S.; Critto, A.; Rizzi, J.; Marcomini, A. Assessment of coastal vulnerability to climate change hazards at the regional scale: the case study of the North Adriatic Sea. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2012, 12, 2347–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclaughlin, S.; Cooper, J.A.G. A multi-scale coastal vulnerability index: A tool for coastal managers? Environmental Hazards 2010, 9, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Aguilar, D.; Jiménez, J.A.; Nicholls, R.J. Flood hazard and damage assessment in the Ebro Delta (NW Mediterranean) to relative sea level rise. Natural Hazards 2012, 62, 1301–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.; Hanson, S.; Herweijer, C.; Ranger, N.; Hallegatte, S.; Corfee-Morlot, J.; Chateau, J.; Muir-Wood, R. Ranking Port Cities with High Exposure and Vulnerability to Climate Extremes: Exposure Estimates. OECD, Environment Directorate, OECD Environment Working Papers, Jul. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Losada, J.I.; Méndez, J.F.; Olabarrieta, M.; Liste, M.; Menéndez, M.; Abascal, A.J.; Tomás, A.; Agudelo, R.; Guanche, R.; Santamaría-Medina, R. IMPACTOS EN LA COSTA ESPAÑOLA POR EFECTO DEL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO. Santander, 2002. Accessed: Jul. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/cambio-climatico/temas/impactos-vulnerabilidad-y-adaptacion/fase3_costas_tcm30-178538.pdf#:~:text=El%20%C3%ADndice%20de%20vulnerabilidad%20costera,III.%203.11.

- Nicholls, R.; Wong, P.P.; Burkett, V.; Codignotto, J.O.; Hay, J.; Mclean, R.; Ragoonaden, S.; Woodroffe, C.; Abuodha, P.; Arblaster, J.; Brown, B.; Forbes, D.; Hall, J.; Kovats, S.; Lowe, J.; Mcinnes, K.; Moser, S.; Armstrong, S.; Saito, Y. Coastal systems and low-lying areas. Faculty of Science - Papers 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Ranasinghe, R.; Mentaschi, L.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Athanasiou, P.; Luijendijk, A.; Feyen, L. Sandy coastlines under threat of erosion. Nat Clim Chang 2020, 10, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerch, M.; Spencer, T.; Temmerman, S.; Kirwan, M.L.; Wolff, C.; Lincke, D.; McOwen, C.J.; Pickering, M.D.; Reef, R.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Hinkel, J.; Nicholls, R.J.; Brown, S. Future response of global coastal wetlands to sea-level rise. Nature 2018, 561, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichter, M.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Nicholls, R.J. Exploring Data-Related Uncertainties in Analyses of Land Area and Population in the ‘Low-Elevation Coastal Zone’ (LECZ). J Coast Res 2010, 27, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramieri, E.; Hartley, A.; Barbanti, A.; Santos, F.; Gomes, A.; Hildén, M.; Laihonen, P.; Marinova, N.; Santini, M. Methods for assessing coastal vulnerability to climate change. . Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of key coastal zones analyzed in this study, from L’Estartit (1) in the north to the Albufera Natural Park (9) in the south. Insets show satellite views of each selected area, highlighting the projected shoreline. The main map situates these locations along the Catalonia-Valencian coast in the northwestern Mediterranean.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of key coastal zones analyzed in this study, from L’Estartit (1) in the north to the Albufera Natural Park (9) in the south. Insets show satellite views of each selected area, highlighting the projected shoreline. The main map situates these locations along the Catalonia-Valencian coast in the northwestern Mediterranean.

Figure 2.

Sequence of flood extent images for the Ebro Delta under increasing SLR scenarios: (a) 0 m, (b) +1 m, (c) +2 m, and (d) +3 m. The second row shows the corresponding grayscale versions used for image analysis. The third row displays the differential inundation areas computed by sub-tracting consecutive scenarios: (b–a), (c–b), and (d–c). This process enabled pixel-based quantifi-cation of incremental flooding and supported the estimation of inundated area growth across SLR thresholds.

Figure 2.

Sequence of flood extent images for the Ebro Delta under increasing SLR scenarios: (a) 0 m, (b) +1 m, (c) +2 m, and (d) +3 m. The second row shows the corresponding grayscale versions used for image analysis. The third row displays the differential inundation areas computed by sub-tracting consecutive scenarios: (b–a), (c–b), and (d–c). This process enabled pixel-based quantifi-cation of incremental flooding and supported the estimation of inundated area growth across SLR thresholds.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of the GCFI along the Catalan and Valencian Mediterranean coast. The map displays GCFI values calculated for each of the nine study sites under the considered SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m) categorized into three vulnerability classes: Moderate, High, and Very High. The index integrates the extent and spatial configuration of flood footprints, normalized to enable comparison across sites of varying sizes. This visualization supports a comparative assessment of coastal vulnerability, emphasizing both the magnitude and morphology of potential impacts and their physical susceptibility to SLR impacts.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of the GCFI along the Catalan and Valencian Mediterranean coast. The map displays GCFI values calculated for each of the nine study sites under the considered SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m) categorized into three vulnerability classes: Moderate, High, and Very High. The index integrates the extent and spatial configuration of flood footprints, normalized to enable comparison across sites of varying sizes. This visualization supports a comparative assessment of coastal vulnerability, emphasizing both the magnitude and morphology of potential impacts and their physical susceptibility to SLR impacts.

Figure 4.

Relationship between flooded area and SLR across the nine study sites along the Catalan and Valencian coast. The plot illustrates how the extent of flood-prone areas evolves under three SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m). While some locations (e.g., L’Estartit, Llobregat Delta) exhibit a near-linear increase in flooded area, others (e.g., Tordera Delta, Ebro Delta, Cabanes, Albufera) show non-linear responses, with either concave (decelerating) or convex (accelerating) trends. These patterns reflect the influence of local geomorphological characteristics on flood dynamics.

Figure 4.

Relationship between flooded area and SLR across the nine study sites along the Catalan and Valencian coast. The plot illustrates how the extent of flood-prone areas evolves under three SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m). While some locations (e.g., L’Estartit, Llobregat Delta) exhibit a near-linear increase in flooded area, others (e.g., Tordera Delta, Ebro Delta, Cabanes, Albufera) show non-linear responses, with either concave (decelerating) or convex (accelerating) trends. These patterns reflect the influence of local geomorphological characteristics on flood dynamics.

Figure 5.

Proportional contribution of each sub-region to the total flooded area under different SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m). The pie chart highlights the dominance of ultra-low-lying areas, specifically the Ebro Delta and Albufera de Valencia, in overall territorial loss. These regions account for the largest share of flooded land due to their extensive low-elevation zones, emphasizing the critical impact of the first meter of SLR. The visualization underscores the spatial concentration of vulnerability along the Mediterranean coast.

Figure 5.

Proportional contribution of each sub-region to the total flooded area under different SLR scenarios (+1 m, +2 m, and +3 m). The pie chart highlights the dominance of ultra-low-lying areas, specifically the Ebro Delta and Albufera de Valencia, in overall territorial loss. These regions account for the largest share of flooded land due to their extensive low-elevation zones, emphasizing the critical impact of the first meter of SLR. The visualization underscores the spatial concentration of vulnerability along the Mediterranean coast.

Table 1.

Pixel equivalences for each map scale used in the study and their conversion to square kilometers [km2], calculated from the number of pixels corresponding to a reference distance on the maps and extrapolated using proportional reasoning.

Table 1.

Pixel equivalences for each map scale used in the study and their conversion to square kilometers [km2], calculated from the number of pixels corresponding to a reference distance on the maps and extrapolated using proportional reasoning.

| Measurement map |

Scale [cm map/cm real] |

Scale |

Comparation [km /px] |

Pixels [1km2] |

| 200 m |

1.3 cm = 200 cm |

1: 15384.62 |

200 m = 49.25 px |

60639.06 |

| 500 m |

1.7 cm = 500 cm |

1: 29411.76 |

500 m = 49.25 px |

15376 |

| 1 km |

1.7 cm = 1 km |

1: 58823.53 |

1 km = 49.25 px |

3844 |

| 2 km |

1.7 cm = 2 km |

1: 117647.06 |

2 km = 62px |

961 |

Table 2.

Total flooded surface area (in km²) estimated for each study site under three SLR scenarios: +1 m, +2 m, and +3 m. These values were derived from pixel-based analysis of satellite-derived flood maps and represent the cumulative inundated extent per site under each scenario.

Table 2.

Total flooded surface area (in km²) estimated for each study site under three SLR scenarios: +1 m, +2 m, and +3 m. These values were derived from pixel-based analysis of satellite-derived flood maps and represent the cumulative inundated extent per site under each scenario.

| Site |

SLR |

Flooding (km2) |

| L'Estartit |

+1 m |

12.427 |

| +2 m |

22.786 |

| +3 m |

31.805 |

| Tordera Delta |

+1 m |

0.396 |

| +2 m |

1.378 |

| +3 m |

2.633 |

| Llobregat Delta |

+1 m |

9.722 |

| +2 m |

21.649 |

| +3 m |

33.891 |

| Tarragona |

+1 m |

3.052 |

| +2 m |

5.349 |

| +3 m |

7.874 |

| Ebro Delta |

+1 m |

277.167 |

| +2 m |

295.753 |

| +3 m |

304.544 |

| Prat de Cabanes-Torreblanca |

+1 m |

10.274 |

| +2 m |

12.19 |

| +3 m |

13.727 |

| Castellón de la Plana |

+1 m |

21.473 |

| +2 m |

37.018 |

| +3 m |

50.075 |

| Sagunto |

+1 m |

27.7 |

| +2 m |

45.576 |

| +3 m |

62.136 |

| Albufera de Valencia |

+1 m |

156.805 |

| +2 m |

183.952 |

| +3 m |

206.301 |

Table 3.

Total results for the study area for two types of maps with a tolerance of 0 and 5 pixels. As well as, percentages of flood increase.

Table 3.

Total results for the study area for two types of maps with a tolerance of 0 and 5 pixels. As well as, percentages of flood increase.

| Map |

Tolerance |

Level of inundation [m] |

Pixels [px] |

Affected km2

|

Percentage increase in flooding [%] |

|

| 500 m |

0 |

+1 m |

8129618 |

528.721 |

21.947 |

|

| +2 m |

9913835 |

644.760 |

|

| 15.251 |

|

| +3 m |

11425777 |

743,092 |

|

| 5 |

+1 m |

8127125 |

528,559 |

21,948 |

|

| +2 m |

9910852 |

644,566 |

|

| 15.253 |

|

| +3 m |

11422532 |

742,881 |

|

| 2 km |

0 |

+1 m |

540157 |

562,078 |

20.990 |

|

| +2 m |

653534 |

680.056 |

|

| 14.711 |

|

| +3 m |

749676 |

780.100 |

|

| 5 |

+1 m |

539967 |

561.880 |

20.992 |

|

| +2 m |

653319 |

679.832 |

|

| 14.713 |

|

| +3 m |

749442 |

779.856 |

|

Table 4.

Comparative results for the selected test area using different map scales, showing the affected surface area in km2 for each SLR scenario and the associated percentage error relative to the 200 m scale.

Table 4.

Comparative results for the selected test area using different map scales, showing the affected surface area in km2 for each SLR scenario and the associated percentage error relative to the 200 m scale.

| Scale |

Inundation level [m] |

Affected km2

|

Percentage of error with respect to 200 m map [%] |

| 200 m resolution |

1 |

1.362 |

- |

| 2 |

2.519 |

- |

| 3 |

3.672 |

- |

| 500 m resolution |

1 |

1.354 |

0.59 |

| 2 |

2.487 |

1.27 |

| 3 |

3.624 |

1.31 |

| 1 km resolution |

1 |

1.335 |

1.98 |

| 2 |

2.431 |

3.49 |

| 3 |

3.569 |

2.81 |

| 2 km resolution |

1 |

1.288 |

5.43 |

| 2 |

2.373 |

5.80 |

| 3 |

3.513 |

4.33 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).