1. Introduction

Pediatric chronic pain is a debilitating condition that affects many children’s daily function, yet whose underlying mediator remains unknown.1 Existing theories suggest that chronic pain may stem from an abnormal failure of inhibitory pain modulation or a symptom of disordered sleep; both characteristics of children with chronic pain, and may be mediated by a deficiency of pain inhibition.2,3,4 The experience of acute pain can be characterized by pain threshold, the initial point at which pain is felt, as well as pain tolerance, the amount of pain considered endurable. An inhibitory deficit could manifest as a lower pain tolerance, lower pain threshold, or both.

There have been mixed findings regarding the pain tolerance of children with chronic pain. One Cold Pressor Task (CPT) study showed that children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis have lower pain tolerance compared to controls.5 Conversely, another CPT study showed no significant difference in pain tolerance between children with chronic pain and healthy controls.6 These mixed findings suggest the need for further investigation of pain tolerance.

In contrast, research on pain threshold in chronic pain patients has been relatively conclusive, finding a lower pain threshold in patients with chronic pain. One study reported that adult patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), or Amplified Musculoskeletal Pain Syndrome (AMPS), had a lower pain threshold for painful experimental stimuli involving heat, cold, and pressure than controls.7 Another, using CPT to evoke an acute pain response, confirmed this finding in adult FMS patients.8

Additionally, poor sleep quality has been associated with chronic pain.9 Poor sleep quality has been shown to improve significantly after intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment (IIPT) consisting of rigorous physical and occupational therapy.10

Acute pain is a crucial outcome domain for evaluating treatments for pediatric chronic pain.11 This study aims to assess acute pain thresholds and tolerance before and after IIPT in a hospital-based pain rehabilitation program. The program includes daily 1:1 physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), individual and group cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), parent therapy sessions, and art and music therapy. While this biopsychosocial model-based program has been shown to be effective in alleviating chronic pain symptoms, improving function, and enhancing sleep quality, its impact on acute pain remains unclear.12-15

We hypothesized that children with more severe chronic pain will be hypersensitive to acute pain, and therefore demonstrate lower acute pain thresholds and tolerances than healthy controls, as measured via the CPT. Additionally, we suspect that these children will experience more disordered sleep. We expect that improvements in chronic pain, evident upon discharge and follow-up, will correspond to higher acute pain thresholds and tolerance, as well as improved reported sleep quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population and Setting:

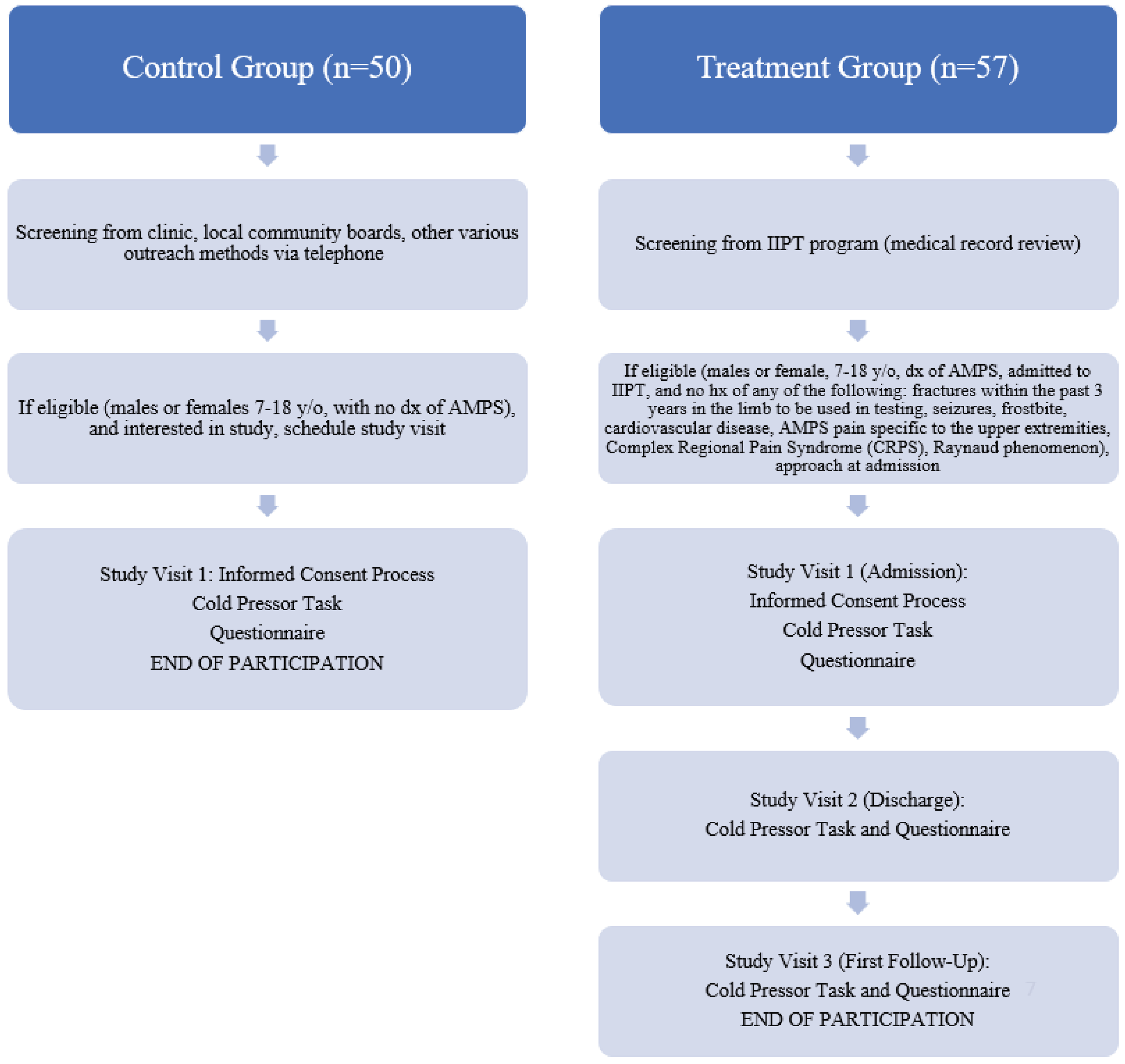

This was convenience sample pre- and post-test study for subjects enrolled in a hospital-based pain rehabilitation program that delivers IIPT and a one-time comparison for control subjects. The study was conducted between September 2015 and February 2023. Active participants included patients 7-18 years old, being admitted to the IIPT program who were diagnosed with amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome (defined as disproportionate pain and disability to any inciting event) by the treating medical provider.16 Exclusion criteria included: 1) those unable to comply with protocol requirements, 2) Subjects who have a history of fractures within the past 3 years in the limb to be used in testing, history of seizures, history of frostbite, history of seizures, history of cardiovascular disease, CMP pain specific to the upper extremities, history of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), or history of Raynaud phenomenon (decreased blood flow in the extremities), 3) parents or subjects unwilling or unable to provide consent for participation. This study received local institutional review board approval. Control participants included males and females 7-18 years old with no diagnosis of amplified pain and able to provide consent/assent.

2.2. Recruitment

Active Subjects: Active subjects were pre-screened based on IIPT program weekly admissions and discharges. Patients deemed potentially eligible were then approached upon admission and explained the purpose and procedures of the study to gauge interest. If interested, the patient and parent/guardian were consented at that time. Active participants received $5 at the first study visit (admission), and then another $5 at the final visit (first follow-up after discharge) via pre-paid gift card.

Control Subjects: Controls subjects were recruited via the general rheumatology and subspecialty pediatric rheumatology pain clinics to match the basic demographics of the active subjects. We approached children in rheumatology clinic with benign diagnoses (e.g., ANA positive, hypermobility syndrome) and no diagnosis of amplified musculoskeletal pain for participation, as well as unaffected siblings in pain clinic. We also advertised the study through local community boards and various outreach methods, including social media and partnerships with community organizations. Potential control participants were identified and reached out to about participating in the study. Those interested would be scheduled for the informed consent and visit in-person. Control participants were compensated $10 via pre-paid gift card for their time and completion of study procedures.

2.3. Questionnaires

Participants completed an online questionnaire via REDCap that included the following measures: Sleep Visual Analog Scale (Sleep VAS) (day/week) which reports quality of the patient’s sleep; Pain Visual Analog Scale (Pain VAS) which assesses the intensity of the subject’s current, usual, least, and most pain; Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) which assesses the impact of adolescents’ physical health on physical and psychosocial functioning with higher scores indicating greater difficulty functioning (no/minimal (0-12), mild (13-20), moderate (21-29), and severe (≥30)); Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) which assesses psychological distress across domains (t-scores of 63 and above should be considered cases); General Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7) which screens for trait anxiety symptoms (0-4 minimal anxiety; 5-9 mild anxiety; 10-14 moderate anxiety; ≥15 severe anxiety); PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Information System) Anxiety Assessment Tool which evaluates pediatric anxiety.17-23

2.4. Cold Pressor Test

This study uses the Cold Pressor Test, which has been validated for use in children as a tool for measuring acute pain threshold and tolerance.

24 Subjects were asked to leave their hand in water measured at 36 (+/-1) degrees Celsius for one minute. The baseline temperature of the finger was recorded. Next, the subject was timed while submerging his/her hand in cold water (held as close as possible to 10 (+/- 1) degrees Celsius) for as long as possible, starting with their left hand, regardless of hand dominance. Subjects reported the point at which pain is first felt and the time from hand immersion to report of pain was recorded as his/her pain threshold. Subjects could remove his/her hand from the water bath at any point. The test was stopped at a maximum of three minutes. Total duration of hand immersion was recorded as his/her pain tolerance. This task was completed according to the guidelines of cold pressor use with children.

24 Active participants were tested with questionnaires and the Cold Pressor Task procedure at entry to and discharge from IIPT program, and then at his/her first follow-up visit post-discharge. Control participants were tested once, at the convenience of the participant and parent/guardian, and the collected values were used as a normal baseline. Please see

Figure 1.

2.5. Data Collection

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were abstracted from the electronic medical record in Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) and merged with data from the clinic’s existing patient registry. Questionnaires were answered and stored in REDCap.

2.6. Data Analysis

Baseline and demographic characteristics were summarized by standard descriptive summaries (e.g. means and standard deviations for continuous variables such as age and percentages for categorical variables such as gender). We compared the demographic and baseline characteristics between controls and those in the treatment group for continuous variables using 2-sample t-tests. For categorical variables, we utilized chi-square tests of independence.

The primary analysis included all subjects meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria and completing Visit 1 (see figure). The primary endpoint was the change in acute pain threshold between Visit 1 and discharge (+/- 1 day) from the IIPT program. Secondary endpoints included the pre-vs post-intervention change in pain tolerance, sleep VAS score, pain VAS score, FDI score, BSI score, GAD-7 score, and PROMIS anxiety score. Additionally, data from controls were used as a comparison for values on all data points of subjects before and after treatment

A multivariate linear mixed-effects model was used to measure the association between demographics information, questionnaire results and both pain threshold and pain tolerance. We utilized the lmer command from the lmerTest package in R. A random subject effect was included in our model with age, gender, visit type (admission as the reference group), sleep VAS – week, sleep VAS – day, FDI score, PROMIS score, GAD score, and total BSI included as fixed effects. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was indicative of statistical significance for all tests. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

2.7. Sample Size and Power

Based on previous CPT studies looking at adult FMS subjects as compared to controls, and aiming to obtain 90% power, a sample size of 46 per group was needed to reach significance for threshold, and 31 for tolerance.

3. Results

A total of 50 control participants and 57 treatment participants were enrolled in this study, with 59.6% of treatment participants completing all study time points. The only reason for incomplete participation was loss to follow-up, in which case their data was included for relevant time points.

Table 1 provides patient demographics and clinical characteristics. For the control group, 25 (50%) were female, 21 (42.0%) were male and 4 (8.0%) did not provide their sex. In the treatment group, 40 (70%) were female, and 17 (30%) were male. The average age was 13 years (SD 3.17) for the control group and 14.6 years (SD 2.57) for the treatment group. There were no statistically significant differences in age or sex between the control and treatment groups.

When comparing control subjects to those in the treatment group at admission, all measured variables except the pain VAS during the CPT were significant (

Table 2). Children with chronic pain at admission demonstrate lower acute pain thresholds (p < 0.001) and tolerances (p <0.05). Additionally, children with more severe chronic pain at admission have higher sleep VAS, indicating worse sleep quality, on both a weekly (p < 0.001) and daily (p < 0.001) basis. At baseline, the treatment group had a significantly lower pain threshold, and significantly higher FDI, PROMIS, and Pain VAS scores compared to the control group (all p < 0.001). This remained true following treatment at both discharge (all p < 0.001) and follow-up (pain threshold, FDI, and Pain VAS p<0.001; PROMIS p=0.021). However, pain tolerance and Sleep VAS week and day scores were no longer statistically significant (all p>0.05) at these time points. GAD-7 remained significant until follow-up (at admission p<0.001, at discharge p=0.016). The difference between controls and subjects on the BSI was only significant at admission (p < 0.001).

Children with chronic pain demonstrated a statistically significant difference on a variety of measures between admission and discharge from the IIPT program (

Table 3). At discharge, FDI (p < 0.001), PROMIS (p = 0.004), GAD (p = 0.025), BSI (p <0.001), and Pain VAS (p = 0.011) scores all significantly decreased. However, pain threshold, pain tolerance, weekly sleep quality, and Pain VAS describing pain related to CPT did not significantly differ. When looking at the difference between admission and first follow-up post-treatment, the improvement in FDI (p < 0.001), PROMIS (p < 0.001), GAD (p < 0.001), BSI (p < 0.001), and Pain VAS (p < 0.001) scores were sustained and there were additional improvements in weekly sleep quality (p = 0.038) and daily sleep quality (p = 0.020).

In the linear mixed effects model, with average pain threshold as the outcome, age was a significant predictor when controlling for the other variables in the model (

Table 4). As age increased, so did the pain threshold (p=0.021). As FDI score increased, the average pain threshold increased (p=0.04). For each unit increase in the Pain VAS score (indicating greater recent level of chronic pain), average pain tolerance significantly decreased (p=0.02), and pain threshold slightly decreased, but this was not statistically significant (p >0.05). There was no significant difference in average pain threshold or pain tolerance between the different measurement times.

4. Discussion

Pain is a subjective experience, and one that ethics dissuade researchers from experimentally inducing. However, cold pressor was evaluated as a reliable and ethically responsible measure of pain in children specifically.25 While previous studies have demonstrated that patients with chronic pain syndromes have lower acute pain thresholds, more investigation is needed to determine the relationship of chronic pain to the experience of acute pain tolerance, as well as how the experience of acute pain (as measured by acute pain threshold and tolerance) might vary as chronic pain is treated and improves.

Our results reveal that, patients with chronic pain showed significantly lower average pain tolerance and threshold compared to controls, indicating greater sensitivity to acute pain stimuli. Within the treatment group, these measures did not significantly change after treatment, despite clinical improvements in several other areas. In addition to lower pain threshold and tolerance, patients with chronic pain exhibit poorer sleep quality, more functional disability, and greater anxiety, psychological distress, and degree of pain experienced, compared to controls. Significant improvements were observed in functional and symptom-related measures (FDI, PROMIS, GAD-7, Total BSI, Pain VAS) from admission to follow-up, re-demonstrating the known benefit of IIPT for the management of pediatric chronic pain.14

While most of these outcomes were already significantly improved by the time of discharge, the improvement in sleep quality was not observed until the time of follow-up, suggesting a delayed treatment effect. Existing literature links chronic pain and poor sleep, and our findings suggest a possible directional component of this relationship such that improvement in chronic pain may lead to an improvement in sleep quality.26-28 Despite these improvements, pain threshold and tolerance remained stable throughout the treatment and follow-up periods. This stability underscores that, contrary to what we hypothesized, acute pain threshold and tolerance are likely not a good proxy for determining treatment effects. However, they may take time to improve after treatment, or they may be more static characteristics of this population, and not readily malleable. It is possible that the stability of acute pain metrics before and after treatment reflects an ongoing difficulty with coping with discomfort that is not resolved by the time of treatment follow-up or a conditioned expectation of what a painful experience may feel like based on their history of sensitivity to pain.

There were several limitations of this study that need to be addressed. We did not collect participant information on race or ethnicity. This limits the generalizability of our findings and prevents this study from potentially measuring disparities in access to or efficacy of care. While not statistically significant, there were also differences in the age and sex of the patients in the control vs the treatment group. Better matching of controls to our clinical sample would enable better generalizability of our results and remove these as possible confounding factors, though this seems unlikely based on the results of the linear mixed effects model. Additionally, there was variability in follow-up scheduling among patients, with the average follow-up appointment occurring approximately 1 to 2 months after discharge from the program. However, this timing was not consistent for all patients—some attended sooner, some later, and some did not attend at all. Because there are uneven sample sizes between admission and discharge groups due to attrition, we are unable to calculate a paired t-test so that individual differences between participants can be eliminated. This limits our ability to control for individual differences and sampling errors. Future research should consider accounting for the timing of follow-up visits and potentially only include patients who complete all study sessions. It may be beneficial to include a second follow-up visit or extend the follow-up period to better assess the durability of treatment benefits. Future studies should consider examining the impact of individual treatment components (e.g., physical therapy vs. psychological therapy) to better understand the contribution of each treatment component to patient outcomes.

The goal of our study was to determine the relationship between the acute and chronic pain experiences and sleep quality in children with chronic pain, and how these factors may or may not change following participation in the IIPT program. In addition to redemonstrating efficacy of the IIPT program, as indicated by improved functional and psychological measures following treatment, we found that sleep quality improves following treatment, however this treatment effect is delayed and only observable at follow-up. This suggests that disturbed sleep is likely a symptom of, rather than a contributor to, chronic pain in children. Our findings indicate that acute pain tolerance and threshold are both significantly lower in the population with chronic pain as compared to controls at baseline, and that this difference persists following treatment, despite functional improvement. We therefore suggest that CPT measures of acute pain threshold and tolerance are likely not appropriate proxy measures to use while evaluating the course and treatment of chronic pain in children, but rather that treatment outcomes are likely better evaluated through functional and psychological measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and D.D.S; Methodology, R.S., S.G. and D.D.S.; Formal Analysis, A.M.; Investigation, M.M.; Resources, S.G. and D.D.S.; Data Curation, M.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.S., M.M. and A.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, R.S., M.M., S.G., A.M. and D.D.S.; Visualization, M.M. and A.M.; Supervision, S.G. and D.D.S.; Project Administration, M.M.; Funding Acquisition, S.G. and D.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Snider Family and Snider Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (IRB 15-012154, September 2nd, 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Rheumatology Research Core staff for helping to complete participant cold presser tasks.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Gmuca is supported by the Snider Family. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Weiss, J.E.; Stinson, J.N. Pediatric Pain Syndromes and Noninflammatory Musculoskeletal Pain. Pediatric clinics of North America 2018, 65, 801–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigatti, S.M.; Hernandez, A.M.; Cronan, T.A.; et al. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2008, 59, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julien, N.; Goffaux, P.; Arsenault, P.; et al. Widespread pain in fibromyalgia is related to a deficit of endogenous pain inhibition. Pain 2005, 114, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, K.B.; Kosek, E.; Petzke, F.; et al. Evidence of dysfunctional pain inhibition in Fibromyalgia reflected in rACC during provoked pain. Pain 2009, 144, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thastum, M.; Zachariae, R.; Scheler, M.; et al. Cold Pressor Pain: Comparing Responses of Juvenile Arthritis Patients and Their Parents. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology 1997, 26, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J.C.; Evans, S.; Seidman, L.C.; et al. Experimental pain responses in children with chronic pain and in healthy children: how do they differ? Pain research & management 2012, 17, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Savoie, E.; Marchand, S.; Morin, M.; et al. Is the deficit in pain inhibition in fibromyalgia influenced by sleep impairments? The open rheumatology journal 2012, 6, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.; Batra, A.; Kötter, I.; et al. Both pain and EEG response to cold pressor stimulation occurs faster in fibromyalgia patients than in control subjects. Psychiatry research 2000, 97, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.M.; Kiska, R. Subjective sleep disturbances in adolescents with chronic pain: relationship to daily functioning and quality of life. The journal of pain 2005, 6, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.N.; Sherry, D.D.; Boyne, K.; et al. Relationship between sleep and pain in adolescents with juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Sleep 2013, 36, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.J.; Walco, G.A.; Turk, D.C.; et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. The journal of pain 2008, 9, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmuca, S.; Sherry, D.D. Fibromyalgia: Treating Pain in the Juvenile Patient. Paediatric. Drugs 2017, 19, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.E.; Pate, J.W.; Richardson, P.A.; et al. Best-Evidence for the Rehabilitation of Chronic Pain Part 1: Pediatric Pain. Journal of clinical medicine 2019, 8, 12–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, D.D.; Brake, L.; Tress, J.L.; et al. The Treatment of Juvenile Fibromyalgia with an Intensive Physical and Psychosocial Program. The Journal of pediatrics 2015, 167, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Atzeni, F.; Boccassini, L.; et al. Physiopathology of pain in rheumatology. Reumatismo 2014, 66, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, D.D.; Sonagra, M.; Gmuca, S. The spectrum of pediatric amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol 2020, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqurashi, Y.D.; Dawidziuk, A.; Alqarni, A.; et al. A visual analog scale for the assessment of mild sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and healthy participants. Annals of thoracic medicine 2021, 16, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.P.; Karoly, P.; Braver, S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain 1986, 27, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Flowers, S.R.; Claar, R.L.; et al. Clinical utility and validity of the Functional Disability Inventory among a multicenter sample of youth with chronic pain. Pain 2011, 152, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. BSI brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. National Computer Systems 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mossman, S.A.; Luft, M.J.; Schroeder, H.K.; et al. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation. Annals of clinical psychiatry: official journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists 2017, 29, 227–234A. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkonis, P.A.; Choi, S.W.; Reise, S.P.; et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment 2011, 18, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Baeyer, C.L.; Piira, T.; Chambers, C.T.; et al. Guidelines for the cold pressor task as an experimental pain stimulus for use with children. The journal of pain 2005, 6, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnie, K.A.; Petter, M.; Boerner, K.E.; et al. Contemporary Use of the Cold Pressor Task in Pediatric Pain Research: A Systematic Review of Methods. The Journal of Pain 2012, 13, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husak, A.J.; Bair, M.J. Chronic Pain and Sleep Disturbances: A Pragmatic Review of Their Relationships, Comorbidities, and Treatments. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2020, 21, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayar, K.; Arikan, M.; Yontem, T. Sleep Quality in Chronic Pain Patients. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2002, 47, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, E.; Sharma, S.; Ferreira-Valente, A.; et al. The Associations Between Sleep Disturbance, Psychological Dysfunction, Pain Intensity, and Pain Interference in Children with Chronic Pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2022, 23, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).