Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

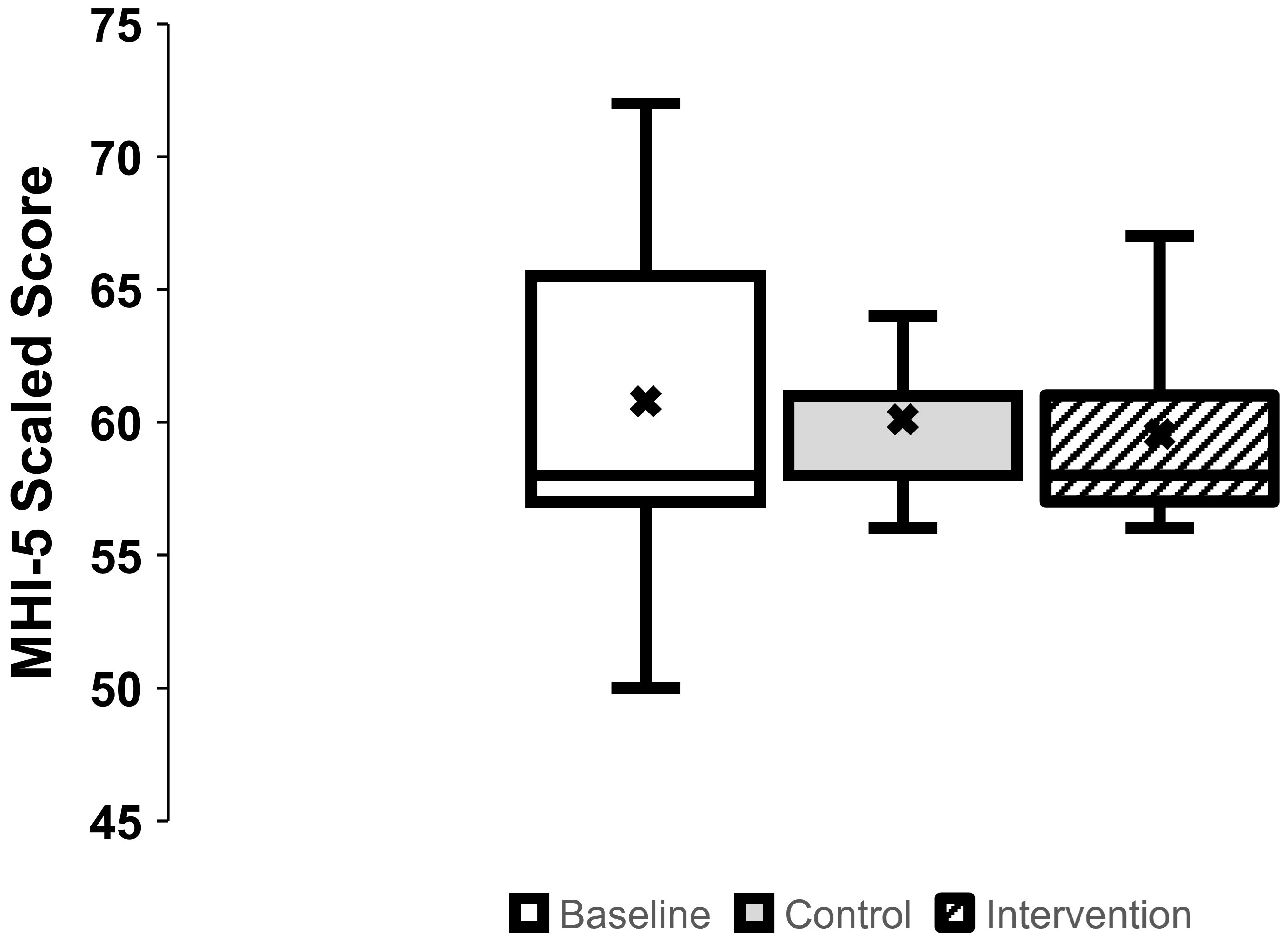

Background/Objectives: Rates of depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and chronic pain are higher in people with spinal cord injury (SCI) compared with able-bodied (AB) individuals. Passive heat therapy (PHT) that raises core body temperature may be an accessible alternative to exercise in SCI. The effects of PHT on mental health, sleep, and pain in persons with SCI are unknown. Methods: We performed a pre-post intervention pilot study in which ten veterans with chronic SCI underwent an 8-week supervised passive heat therapy intervention to raise oral temperature by 1℃. Outcome measures were the 5-item Mental Health Inventory, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and International Spinal Cord Injury Pain Extended Data Sets version 1.0. Results: There were no adverse events related to the intervention and nine out of ten participants completed all their intervention sessions. There was a reduction in pain intensity (p=0.039) upon completing the intervention. However, there were no improvements in self-reported mental health nor sleep outcomes (p=0.339). Conclusions: This pilot study suggests that supervised repeated passive heat therapy may confer benefits for chronic pain in veterans with chronic SCI. Follow-up study with a larger sample size and a more extensive set of chronic pain outcomes is needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design and Procedures

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health (Figure 1)

3.2. Sleepiness

3.3. Pain (Table 2)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sankari, A.; Badr, M.S.; Martin, J.L.; Ayas, N.T.; Berlowitz, D.J. Impact Of Spinal Cord Injury On Sleep: Current Perspectives. Nat Sci Sleep 2019, 11, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.; van Leeuwen, C. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord 2012, 50, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt C, Moman R, Peterson A, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain after spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2021, 46, 328–336. [CrossRef]

- Bresnahan JJ, Scoblionko BR, Zorn D, et al. The demographics of pain after spinal cord injury: a survey of our model system. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2022, 8, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yong, R.J.; Mullins, P.M.; Bhattacharyya, N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain 2022, 163, e328–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Dorstyn, D. Anxiety prevalence following spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis [published correction appears in Spinal Cord. Spinal Cord 2016, 54, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biering-Sørensen, F.; Biering-Sørensen, M. Sleep disturbances in the spinal cord injured: an epidemiological questionnaire investigation, including a normal population. Spinal cord. 2001, 39, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Shafazand S, Anderson KD, Nash MS. Sleep Complaints and Sleep Quality in Spinal Cord Injury: A Web-Based Survey. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(5):719-724. [CrossRef]

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:379- 385.

- . [CrossRef]

- Alnawwar MA, Alraddadi MI, Algethmi RA, et al. The Effect of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality and Sleep Disorder: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e43595. [CrossRef]

- Geneen L, Moore RA, Clarke C, et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 4, CD011279. [CrossRef]

- Maynou L, Hernández-Pizarro HM, Errea Rodríguez M. The Association of Physical (in)Activity with Mental Health. Differences between Elder and Younger Populations: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 4771. [CrossRef]

- Chekroud SR, Gueorguieva R, Zheutlin AB, et al. Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1·2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):739-746. [CrossRef]

- Tamminen N, Reinikainen J, Appelqvist-Schmidlechner K, et al. Associations of physical activity with positive mental health: A population-based study. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2020, 18, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Connell EM, Olthuis JV. Mental health and physical activity in SCI: Is anxiety sensitivity important? Rehabil Psychol. 2023;68(2):174-183. [CrossRef]

- Albu S, Umemura G, Forner-Cordero A. Actigraphy-based evaluation of sleep quality and physical activity in individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2019, 5, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palandi J, Bobinski F, de Oliveira GM, et al. Neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury and physical exercise in animal models: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2020;108, 781–795. [CrossRef]

- Todd K, Van Der Scheer JW, Walsh JJ, et al. The Impact of Sub-maximal Exercise on Neuropathic Pain, Inflammation, and Affect Among Adults With Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2021;2:700780. doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2021.

- Toloui A, Ramawad HA, Gharin P, et al. The Role of Exercise in the Alleviation of Neuropathic Pain Following Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurospine. 2023;20(3), 1073–1087. [CrossRef]

- Williams TL, Smith B, & Papathomas A. The barriers, benefits and facilitators of leisure time physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Health psychology review 2014, 8, 404–425.

- Rocchi M, Routhier F, Latimer-Cheung A, et al. Are adults with spinal cord injury meeting the spinal cord injury-specific physical activity guidelines? A look at a sample from a Canadian province. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 454–459. [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen JA, Kunutsor SK. The multifaceted benefits of passive heat therapies for extending the healthspan: A comprehensive review with a focus on Finnish sauna. Temperature (Austin) 2024, 11, 27–51. [CrossRef]

- Haack M, Simpson N, Sethna N, et al. Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(1):205-216. [CrossRef]

- Vadivelu N, Kai AM, Kodumudi G, et al. Pain and Psychology-A Reciprocal Relationship. Ochsner J. 2017;17(2):173-180.

- Oosterveld FG, Rasker JJ, Floors M, et al. Infrared sauna in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. A pilot study showing good tolerance, short-term improvement of pain and stiffness, and a trend towards long-term beneficial effects. Clin Rheumatol 2009;28:29-34.

- Cho EH, Kim NH, Kim HC, et al. Dry sauna therapy is beneficial for patients with low back pain. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2019, 14, 474–479. [CrossRef]

- Nurmikko T, Hietaharju A. Effect of exposure to sauna heat on neuropathic and rheumatoid pain [published correction appears in Pain 1992 Jun;49(3):419]. Pain 1992, 49, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Putkonen PTS and Eloma, E. Sauna and physiological sleep: Increased slow-wave sleep after heat exposure. Sauna Studies. 1976, 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Mishima Y, Hozumi S, Shimizu T, et al. Passive body heating ameliorates sleep disturbances in patients with vascular dementia without circadian phase-shifting. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005, 13, 369–376. [CrossRef]

- Liao, WC. Effects of passive body heating on body temperature and sleep regulation in the elderly: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39 (8):803–810. [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh S, Khoshnevis S, Smolensky MH, et al. Before-bedtime passive body heating by warm shower or bath to improve sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2019, 46, 124–135. [CrossRef]

- Masuda A, Nakazato M, Kihara T, et al. Repeated Thermal Therapy Diminishes Appetite Loss and Subjective Complaints in Mildly Depressed Patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005; 67, 634–647. [CrossRef]

- Beever, R. The effects of repeated thermal therapy on quality of life in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. J Altern Complement Med 2010, 16, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs GB, Barak OF, Phillips AA, et al. Acute heat stress reduces biomarkers of endothelial activation but not macro-or microvascular dysfunction in cervical spinal cord injury. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2019, 316, H722–H733. [CrossRef]

- Leicht CA, Kouda K, Umemoto Y, et al. Hot water immersion induces an acute cytokine response in cervical spinal cord injury. European journal of applied physiology 2015, 115, 2243–2252. [CrossRef]

- Trbovich M, Wu Y, Koek W, et al. Elucidating mechanisms of attenuated skin vasodilation during passive heat stress in persons with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2024, 47, 765–774. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trbovich M, Wu Y, Koek W, et al. Impact of tetraplegia vs. paraplegia on venoarteriolar, myogenic and maximal cutaneous vasodilation responses of the microvasculature: Implications for cardiovascular disease. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2022, 45, 49–57. [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen CM, van der Woude LH, Post MW. Validity of the mental health subscale of the SF-36 in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2012, 50, 707–710. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman B, Heisel M, Delavan R. Validity of the SF-36 five-item Mental Health Index for major depression in functionally impaired, community-dwelling elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53, 1978–1985. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zürcher C, Tough H, Fekete C, for the SwiSCI Study Group. Mental health in individuals with spinal cord injury: The role of socioeconomic conditions and social relationships. PLOS ONE. 2019, 14, e0206069. [CrossRef]

- Johns, MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545. [CrossRef]

- Widerström-Noga E, Biering-Sørensen F, Bryce TN, et al. The International Spinal Cord Injury Pain Extended Data Set (Version 1.0). Spinal Cord 2016, 54, 1036–1046. [CrossRef]

- Naumann J, Sadaghiani C. Therapeutic benefit of balneotherapy and hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a qualitative systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2014, 16, R141. [CrossRef]

- Bai R, Li C, Xiao Y, et al. Effectiveness of spa therapy for patients with chronic low back pain: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98(37), e17092. [CrossRef]

- Rahman MM, Jo YY, Kim YH, et al. Current insights and therapeutic strategies for targeting TRPV1 in neuropathic pain management. Life Sci 2024, 355, 122954. [CrossRef]

- Hulsebosch CE, Hains BC, Crown ED, Carlton SM. Mechanisms of chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Brain Res Rev 2009, 60, 202–213. [CrossRef]

- Ely BR, Clayton ZS, McCurdy CE, et al. Heat therapy improves glucose tolerance and adipose tissue insulin signaling in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2019, 317, E172–E182. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka K, Kuzumaki N, Hamada Y, et al. Elucidation of the mechanisms of exercise-induced hypoalgesia and pain prolongation due to physical stress and the restriction of movement. Neurobiology of pain (Cambridge, Mass.). 2023;14, 100133. [CrossRef]

- Hanusch KU, & Janssen CW. The impact of whole-body hyperthermia interventions on mood and depression – are we ready for recommendations for clinical application? International Journal of Hyperthermia 2019, 36, 572–580. [CrossRef]

- Janssen CW, Lowry CA, Mehl MR, et al. Whole-Body Hyperthermia for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016, 73, 789–795. [CrossRef]

- Spong J, Graco M, Brown DJ, et a. Subjective sleep disturbances and quality of life in chronic tetraplegia. Spinal cord, 2015;53(8), 636–640. [CrossRef]

- Matta Mello Portugal E, Cevada T, Sobral Monteiro-Junior R, et al. Neuroscience of exercise: from neurobiology mechanisms to mental health. Neuropsychobiology. 2013;68(1):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa T, Hoekstra SP, Kamijo YI, et al. Serum and plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration are elevated by systemic but not local passive heating. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260775. [CrossRef]

- LaVela SL, Etingen B, Miskevics S, et al. Use of PROMIS-29® in US Veterans: Diagnostic Concordance and Domain Comparisons with the General Population. J Gen Intern Med. 2019, 34, 1452–1458. [CrossRef]

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 45 (14) |

|---|---|

| Years since injury, mean (SD) | 9.2 (10.5) |

| Lesion level, n (%) | |

| Cervical, C4-C7 | 4 (40) |

| Thoracic, T5-T12 | 6 (60) |

| AIS Completeness, n (%) | |

| A | 4 (40) |

| B | 1 (10) |

| C | 4 (40) |

| D | 1 (10) |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.0 (3.0) |

| Note: AIS = American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; SD = standard deviation; n = count | |

| Question | Baseline | Control | Intervention | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of days with pain, median (IQR) | 7.0 (0.0, 7.0) | 6.5 (2.0, 7.0) | 4.0 (0.0, 7.0) | 0.156 |

| Worst pain intensity in last week, median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.50, 7.50) | 3.0 (0.0, 5.3) | 3.0 (0.0, 6.0) | 0.076 |

| Pain unpleasantness, median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.5, 6.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 4.3) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.504 |

| Number of days with manageable/tolerable pain, median (IQR) | 5.5 (1.0, 7.0) | 5.0 (0.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 6.0) | 0.494 |

| Pain intensity presently, median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.0, 5.5) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.5) | 1.0 (0.0, 4.5) | 0.039 |

| Length of time pain lasts, n (% of respondents) | 0.008 | |||

| ≤ 1 min | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | |

| > 1 min, but < 1 h | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥ 1 h but <24 h | 2 (20) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | |

| ≥ 24 h | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Constant/continuous | 4 (40) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | |

| Unknown | 1 (10) | 1 (10 | 1 (10) | |

| Unanswered | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | |

| When during the day is the pain most intense, n (% of respondents) | 0.174 | |||

| Morning (06:01-12:00) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | |

| Afternoon (12:01-18:00) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Evening (18:01-24:00) | 2 (20) | 1 (10) | 3 (30) | |

| Night (0:01-06:00) | 1 (10) | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | |

| Unpredictable (pain is not consistently more intense at any one time of day) | 3 (30) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | |

| Unanswered | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).