1. Introduction

Since the ground breaking transport measurements were reported on graphene in 2004, [

1] all the novel low-dimensional materials have received tremendous attention from researchers in condensed matter physics and relevant materials science fields. Later, some other structures with tunable spin-orbit bandgaps, such as buckled honeycomb lattices, were discovered. Their magneto-optical properties [

2] were also studied thoroughly, including general collective-excitation modes [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] and massive hyperbolic plasmons [

11]. Furthermore, other novel electron dispersions have been founded in both Kekule-distorted graphene [

12,

13,

14,

15] and semi-Dirac materials. Meanwhile, their optical properties [

16,

17] and topological electronic behaviors [

18] were investigated extensively. Specifically, the optical conductivity of all these materials, [

14,

19,

20,

21] including anisotropic and tilted [

22] Dirac cones, [

23,

24,

25,

26] was fully explored both theoretically and experimentally.

Among these recently discovered two-dimensional lattices, a special attention has been put on unique materials with a flat (or nondispersive) band in their low-energy band structure. [

27,

28] This flat band, which could be located at arbitrary positions between an upper-conduction and a lower-valance band, leads to an infinite degeneracy for energies of these flat-band electrons and brings out new features to electronic properties of this type of materials. [

29] Some typical examples of such flat-band materials include a dice, Lieb [

30,

31,

32] and Kagome lattices [

33,

34,

35], as well as few other important materials. [

36,

37]

The

-

model represents a very special type of two-dimensional structure which also exhibits a flat band in their low-energy spectrum. [

38,

39] The flat band in the

-

model originates from the existence of an additional hub atom at the center of each hexagon of a graphene-like two-dimensional lattice. The hopping coefficients between the hub and rim (regular) atoms in

-

model could be parameterized by a chosen number

within the range

. Consequently, we obtain a physical model, which describes realistically a verity of materials with a flat band, and simultaneously, receives tremendous attention from researchers. Specifically, electronic structures, [

40,

41,

42] transport, [

43,

44,

45,

46] collective optical, [

4] magnetic, [

47] electronic phenomena in

-

rings, [

48,

49] and properties of other two-dimensional lattice materials [

29,

50] have been extensively investigated.

Interestingly, the main characteristics of the electronic dispersions, such as band gaps, group velocities and anisotropy of graphene and other two-dimensional materials, will change significantly by applying an off-resonance electromagnetic dressing field. [

51,

52,

53,

54] In such a case, the modification of energy spectrum depends strongly on the polarization of incident irradiation, in addition to the field frequency and strength. In fact, there has already been a number of crucial publications aiming to study the electronic, collective and transport properties of materials with a Dirac cone deformed by an optical-dressing field. [

55,

56,

57]

As a different and impactful issue, magnetic properties of these emergent two-dimensional materials and the corresponding electron dynamics under magnetic fields have also been explored extensively and received encouraging responses from researchers working in various fields. This includes the calculation and detailed analysis of Landau-level dispersion and electronic states under a magnetic field in graphene, [

58,

59,

60] silicene, [

61,

62] and transition-metal dichalcogenides, [

63,

64] covering their magneto-optical [

65,

66] and magneto-transport [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71] properties as well. Meanwhile, various magnetic-field responses of

-

material were also studied. [

62] In addition, this research effort further extends to magneto-plasmons and other collective behaviors in graphene materials [

72] with a tunable spin-orbit bandgap [

2,

62,

73,

74] and in

-

model [

75,

76] as well.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we present general formalism for Dirac electrons in magnetic fields, including their energy eigenvalues (Landau levels) as well as their wave functions.

Section 3 is devoted to presenting several novel derivations for some known results associated with Landau levels within a gapped graphene, including computing wave functions for the case with a finite gap

. In

Section 4, we consider Landau quantization of electrons and corresponding electronic states within a dice lattice with both zero and a finite bandgap, accompanied by a flat band sitting at the middle between a valence and conduction bands. After that, we derive in

Section 5 the Landau levels and corresponding eigenstates of electrons within a Lieb lattice with an elevated flat band. Finally, the final remarks and conclusions are drawn in

Section 6.

2. General Formalism for Landau Quantization

We begin with a brief review of general mathematical formalism employed in calculating the energy eigenstats of free electrons under a spatially uniform magnetic field B, usually referred to as Landau levels. We shall employ the Landau gauge for the vector potential so that while . Therefore, the magnetic field in this case is given by , which is uniform in space domain.

Formally, the effect of a magnetic field

B can be included by using a so-called Peierls substitution in any considered Hamiltonian,

i.e.,

In the case of graphene, its Hamiltonian operator acquires the following explicit form [

77]

where

is magnetic length, and two operators are defined by

which are known as the creation and annihilation operators, respectively. Using the expression in Equation (

3), one can further verify the well-known commutation relation

, and meanwhile, obtain the results for their actions on the electronic states in the Fock space, given by

Here, the results in Equations (

1)–(

4) are all the relations required to calculate the actual Landau levels and their corresponding wave functions in Dirac-cone materials considered in this study.

3. Magneto-Energy Levels of Gapped Graphene

As a start, we consider the case of gapped graphene described by the following low-energy Hamiltonian

which differs from well-known graphene by a finite gap

included as a

term. Here,

are regular

Pauli matrices.

In the presence of a magnetic field

, the canonical substitution or Peierls substitution in Equation (

1) can be emplyed, which leads to the following new Hamiltonian

where

. Mathematically speaking, the simplest way to find energy eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian in Equation (

6) is simply taking the square on both sides of the eigenvalue equation. As a result, we get a new diagonal Hamiltonian matrix, written as

By using the harmonic-oscillator relation

, as well as the following eigenvalue relation

we immediately find

.

In a similar way, we will look for a solutions in the following general form

then the corresponding eigenvalue equations become

Equation (

10) can be equivalently written as

From Equation (

11), we easily find that its solution in the Fock space exists only for

, or equivalently

. Now, let us assume

and

. By following Equation (

11), we acquire

The presence of a physical solution to Equation (

12) requires that its coefficient determinant must be zero. This leads to the following dispersion relation

which produces

, and it is equivalent to a spectrum equation for Landau levels of a gapped graphene. Additionally, its wave function for

is found to be

If

, on the other hand, the result in Equation (

14) immediately turns into

which is reduced to the case for free-standing (zero-gap) graphene. In particular, for

, the wave function (

14) reduces to

Up to here, we have finished the calculation for a closed-form analytical expression of both electronic states and Landau energy levels of electrons within a gapped graphene under an external perpendicular magnetic field.

4. Dice Lattice with Zero Bandgap

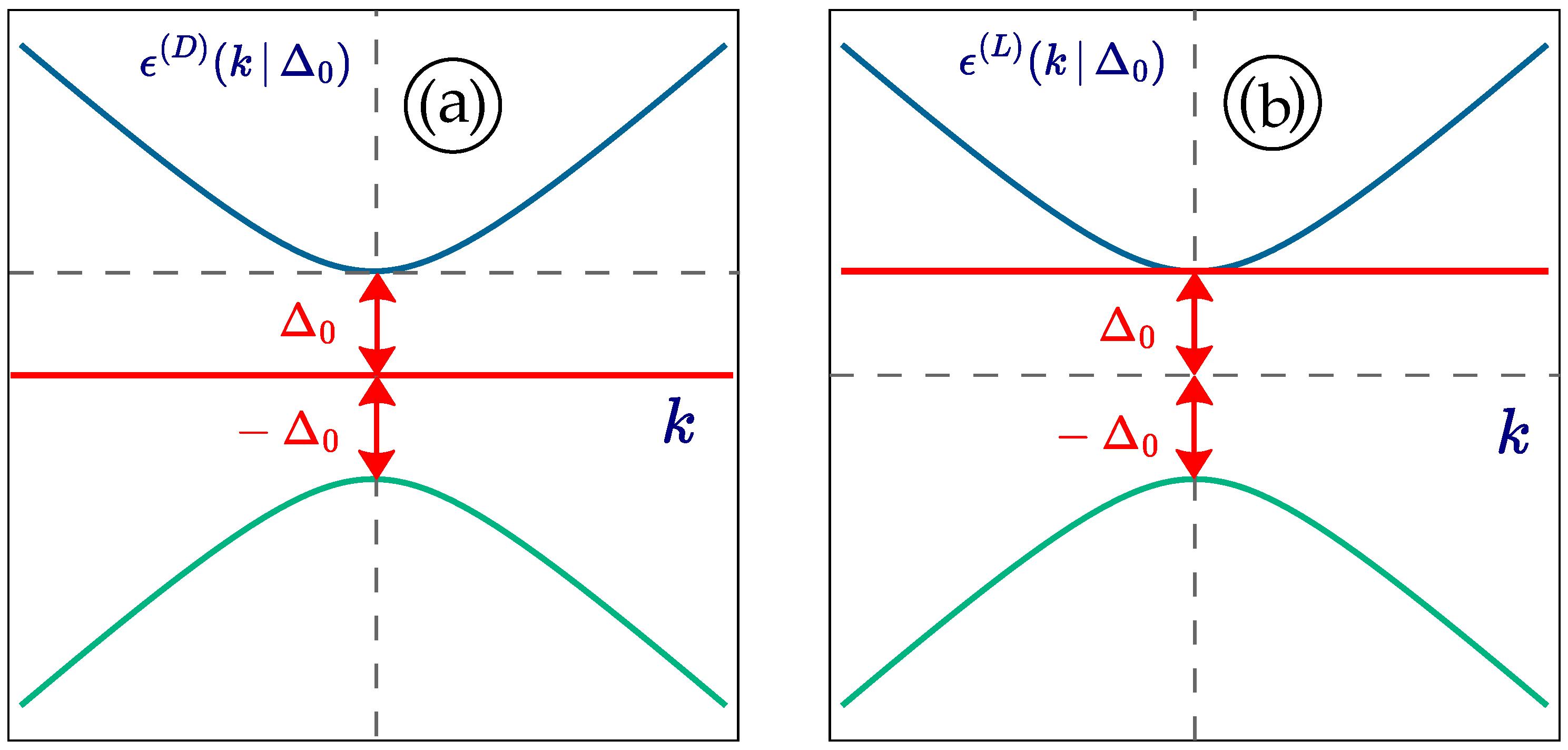

As we mentioned previously in this paper, our present study focuses on investigating pseudospin-1 Dirac materials having a flat band in their low-energy spectrum. The schematics of energy dispersions in both gapped dice and Lieb lattices, as depicted in

Figure 1, contains a flat band, which makes these materials and their electronic properties similar to each other. Interestingly, different position of this flat band inside a bandgap results in a significant difference between the two. In the case of a gapped dice lattice, it sits exactly in the middle between the valence and conduction bands, separated equally from bandedges by a bandgap parameter

, and this makes the whole energy spectrum very symmetric. In another case, i.e., the Lieb lattice, the flat band is located at an elevated position, intersecting the bottom of a conduction band. Such an overlap of the flat band with the bottom of a conduction band has a lot of implications for collective and many-body properties for electrons in these types of materials,

e.g., in the computed polarization function, where all electronic transitions and various energy separations will be taken into account. Here, we focus on the role which the location of the flat-band plays in the presence of a perpendicular and spatially-uniform magnetic field.

The low-energy Hamiltonian for a dice lattice with a zero-gap parameter

(an actual bandgap is

) can be written as

However, in the presence of a magnetic field, the Hamiltonian in Equation (

17) is reansformed into

where

and

represent annihilation and creation operators, respectively, and

. From now on, we will calculate the energy levels (Landau levels) of a dice lattice in cases with a zero bandgap

.

Here, we first write down the wave function in the most general form as

where

are three coefficients to be determined. Inserting the wave function in Equation (

19) into a Schrödinger equation with its Hamiltonian given by Equation (

18), one finds an eigenvalue equation as follows:

where parameter

stands for the eigenvalue to be determined. After analyzing Equation (

20), we know that the conditions of

and

must be satisfied in order to acquire a nonzero (non-trivial) solution of these coupled equations. Specifically, by writing

,

and

, we find from Equation (

20) that

After an analysis of Equation (

21), it becomes clear that this system could support nonzero solution

only if its coefficient determinant is zero. In this way, we find the energy dispersions of a dice lattice, given by

for a flat band, as well as by another nonzero solution

The solved wave functions associated with Equation (

22) are

where

. By choosing

in Equation (

23) as an example, we have

For the flat band

, on the other hand, its wave function is

where

. However, as

, the wave function is modified to

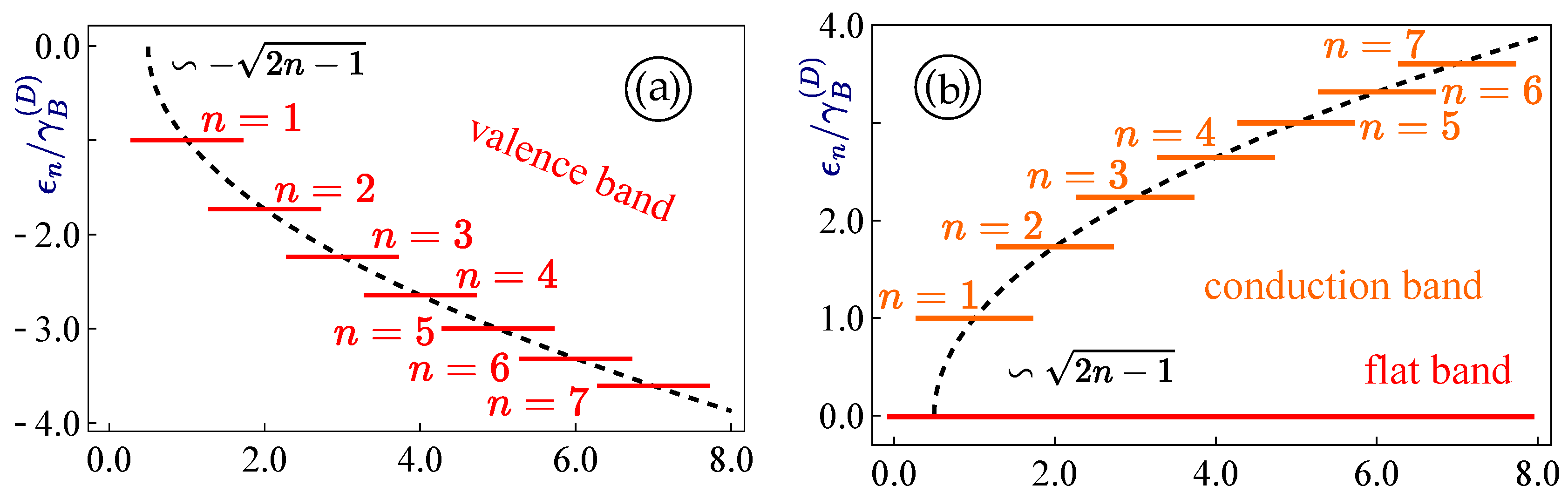

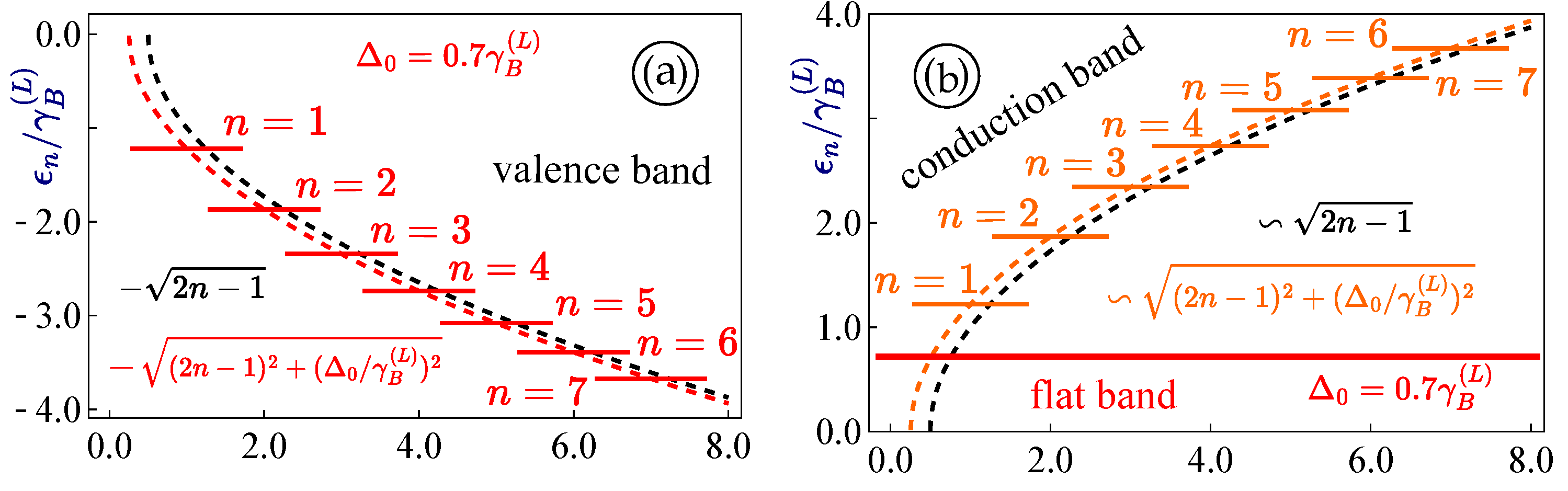

The Landau levels for a zero-bandgap dice lattice, as shown in

Figure 2, is actually a specific limiting case of the energy eigenstates of

-

materials, which was discussed in Ref. [

47]. In the presence of a magnetic field, the eigen-energies of valence and conduction bands reduces to an infinite set of quantized energy levels

, but the flat band

remains dispersionless with an infinite degeneracy. Consequently, we conclude that such configuration of Landau levels displays both similarities and distinctions (a constant energy shift) in comparison with energy dispersion

of graphene.

5. Gapped Dice Lattice

A dice lattice with a finite bandgap

is obtained in terms of a

generalization of the Pauli matrices

in the following way:

where

which are supplemented by an extra bandgap-related matrix,

i.e.,

In the presence of a magnetic field, the Hamiltonian in Equation (

27) is transformed into the form similar to the expression in Equation (

18), and written as

In correspondence with Equation (

21) having

, for current case, we find

Compared with the case of

, the finite value of

here results in a quite different asymmetric dispersion equation,

i.e.,

which cannot be solved in any straightforward way. However, by utilizing an analogy to a trigonometrical expansion formula, as discussed in Refs. [

78] and [

42], it can also be solved by using a perturbation approach as follows:

where the bandgap

is regarded as a small parameter for this expansion. Interestingly, for the flat band with

, one obtains

, and thus

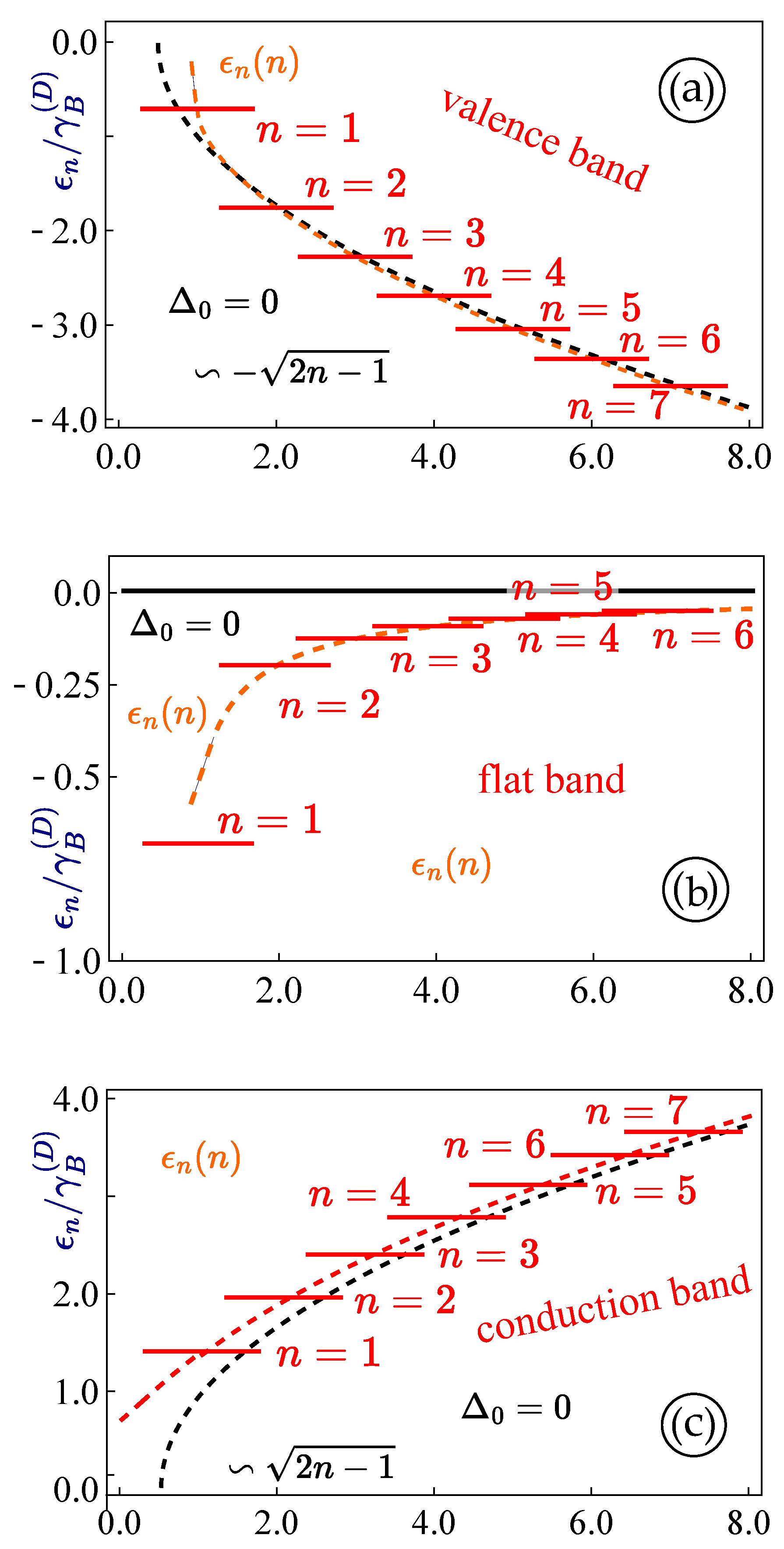

We have obtained numerically a set of discrete Landau levels which are presented in

Figure 3. We first notice that the valence and conduction bands are not exactly symmetric with respect to zero energy and no simple analytical formula or approximate expression exists for describing energy locations of these levels. For the high-energy states with

, the energy eigenstates are well approximated by expressions

, implying that the effect due to bandgap

is decreased. This further supports the validity of a simple but efficient application of the WKB approximation for this case. Here, the flat band is no longer dispersionless and its degeneracy is lifted. On the other hand, we find an infinite set of separated non-dengenerate Landau levels within a negative-energy

region. For large

, the effect of an energy gap becomes negligible and these levels approach the

level.

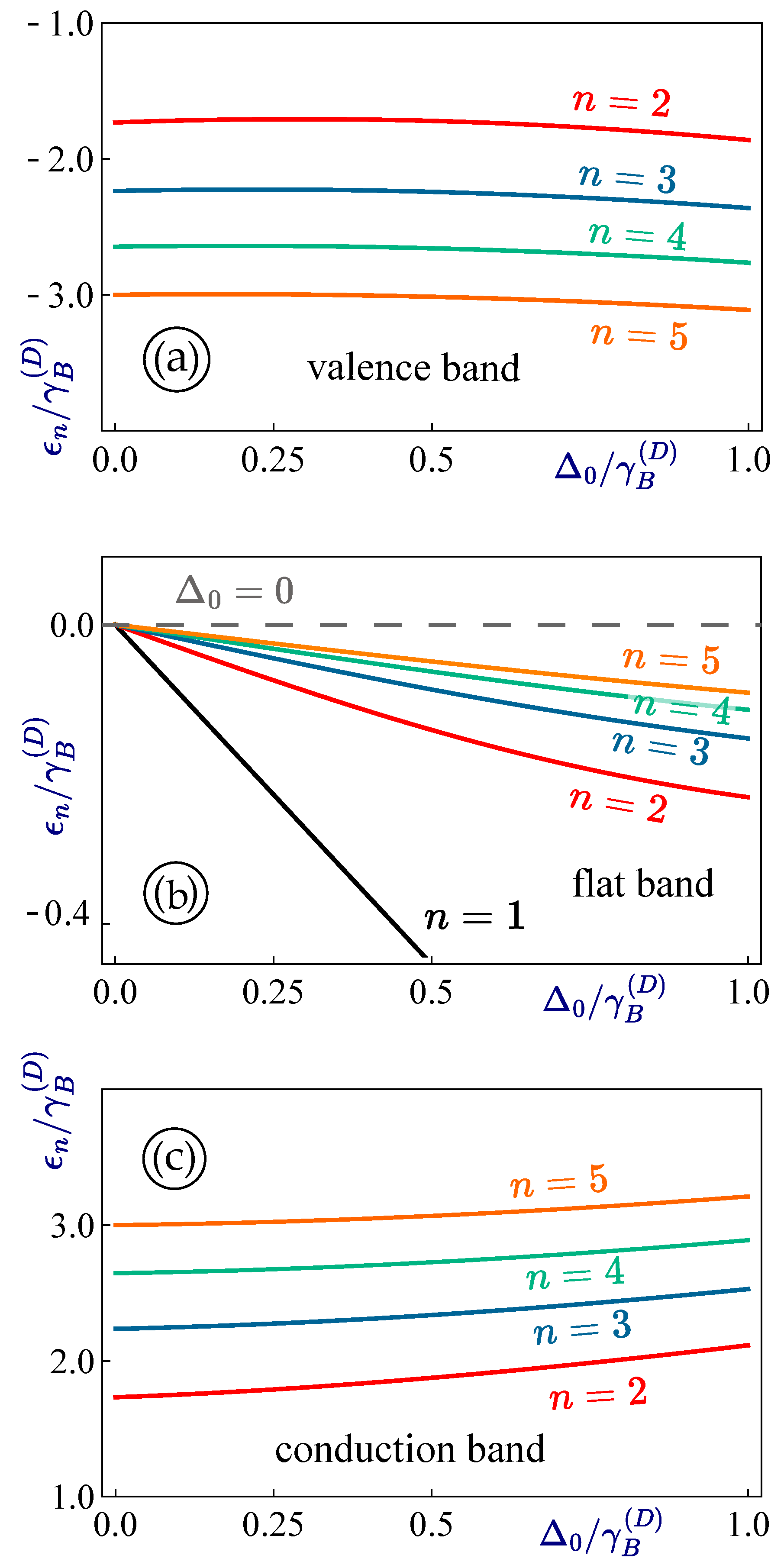

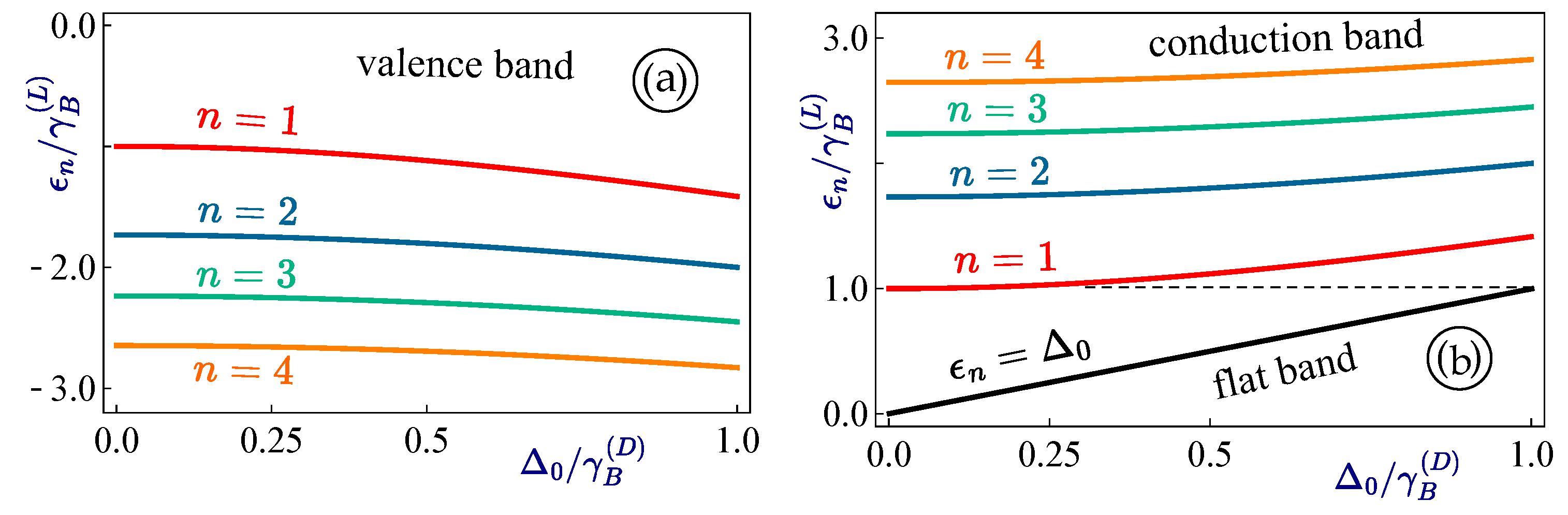

Next, we focus on the dependence of energy levels for a gapped dice lattice on the gap parameter

, and present various numerically computed results in

Figure 4 for a full comparison among Landau levels in the conduction, valence and flat bands all together. As found from

Figure 4, these numerical results once again agree with our previous findings that the high-energy Landau levels with large level index

n (

) will be much less sensitive to the size of bandgap

, which can be easily verified by the fact that large-

n Landau levels would like to group together as

increases for the flat-band case. In particular, the

Landau level in panel (b) demonstrates a negative linear dependence on

, which fully agrees with our perturbation-based solution in Equation (

35).

6. Modeling Lieb Lattice with Elevated Flat Band

we now turn our attention to the major issue of this paper,

i.e.,, modeling the effect of a magnetic field on a Lieb lattice with a non-symmetric elevated flat band, as depicted in

Figure 1(b). In this case, the low-energy Hamiltonian is found to be [

26]

where the following substitution

is required for a Lieb lattice, and

stands for the lattice parameter. Here, before putting the substitution in Equation (

37) into Equation (

36), three energy dispersions can be easily found from the Hamiltonian in Equation (

36) as

and

, which could be combined into a single expression, yielding

where

, and

is the Kronecker symbol.

In the presence of a magnetic field, however, the Hamiltonian in Equation (

36) will change into

Here, it is straightforward to verify that one cannot project this Hamiltonian onto the same Fock-state

representation. However, by searching for the eigen-function in terms of Equation (

39), we obtain one of its eigenvalue equations, given by

Unfortunately, Equation (

40) cannot be satisfied by any

and

states.

On the other hand, we are also able to model the Lieb lattice by an elevated flat band, as illustrated in

Figure 1. For this purpose, let us first write down the Hamiltonian, by using an elevated flat band, as

which results in two energy dispersions, given by

as well as

. Furthermore, in the presence of a magnetic field, we find that the Hamiltonian in Equation (

39) changes into

Correspondingly, previous Equation (

21) for a dice lattice will be changed into

Equation (

43) leads to the eigen-value equation as

which gives rise to the energy levels by

Here, the most interesting thing is the wave function corresponding to the flat band with

. In fact, from Equation (

43), we immediately conclude that

. Thus, this leaves us with

and the corresponding wave function is given by

where

. For

, especially, this wave function is taken as

From Equations (

48) and (

49), we quickly find that they are identical to Equations (

25) and (

26) in the case of zero-gap dice lattice.

Finally, we calculate and plot the Landau levels for our model for a Lieb lattice obtained by relatively simple analytical expressions in Equations (

45) and (

46). Our results are presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. From these two figures, we find that these energy levels, corresponding to the valence and conduction bands, become symmetric now with respect to the zero energy. Similar to the previously considered case for a gapped dice lattice, the effect of an energy bandgap diminishes for higher Landau levels with

. Meanwhile, the flat band remains dispersionless with a simple shift to the gap level

and remains infinitely degenerate. The dependence of these energy levels on the gap

, as shown in

Figure 6, clearly demonstrate such a linear dependence

, as well as a smooth and monotonic dependence of all energy levels, corresponding to the valence and conduction bands, on the gap parameter

.

7. Summary and Remarks

In conclusion, we note that the main thrust of this paper is to present a thorough theoretical and numerical investigation of the quantized energy levels under a uniform external magnetic field (i.e.,, Landau levels) and the corresponding electronic states for several important Dirac cone materials with a flat band in their low-energy spectra.

First, we considered a well-known case for graphene with an energy bandgap and provided new derivations for Landau quantization in this system, given by . Surprisingly, the square Hamiltonian of graphene with a finite bandgap under a magnetic field reduces to a diagonal matrix, which immediately gives rise to the corresponding energy eigenvalues, similarly to the case of an intrinsic graphene with a zero bandgap.

Next, we investigated the electronic states under a magnetic field in a dice lattice with a finite bandgap, which is shown as a limiting case of the general - model. However, the presence of a finite gap turns the eigenvalue equations into a non-trivial cubic equation for computing Landau levels in this system. This cubic equation could be solved either numerically or by using an analogy between this expression and a well-known trigonometric equation, or even a perturbation theory for a small bandgap parameter . The result is in stark contrast with regular energy dispersions (in the absence of a magnetic field), which could be easily found from a simple algebraic equation.

Finally, we investigated the Landau levels for a realistic model of a Lieb lattice with an elevated flat band intersecting the conduction band at its lowest point. This model has both common features and differences from the dice lattice and the - model. The main interest on such physics models is the presence of a flat band within the bandgap region, which greatly affects the electronic, magnetic and collective properties of the material. More importantly, the location of this flat band can be quite unique for the Lieb lattice, which results in substantially reduced symmetry of its low-energy spectrum. We have calculated the Landau levels of this type of energy dispersions and obtained a relatively simple analytical result , which provides a quantitative description for its dynamical feature under a quantizing magnetic field. Meanwhile, we have also calculated the wave function corresponding to the flat band and compared its similarity with other wave functions in a dice lattice.

Generally speaking, magnetic quantization as well as electronic and collective properties under a strong magnetic field, including magneto-transport and magneto-plasmon properties, are crucial for understanding the fundamental physics of any new material, such as quantum-Hall effect. The exact knowledge of the electronic states, discrete energy level or energy bands, is an important step in predicting or understanding their novel electronic and topological properties. Our theoretical model, novel closed-form analytical expressions and numerical results are believed to become a crucial advancement in developing next-level novel electronic nanodevices.

Acknowledgments

A.I. was supported by the funding received from TradB-56-75, PSC-CUNY Award # 68386-00 56. G.G. gratefully acknowledges funding from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) via the NASA-Hunter College Center for Advanced Energy Storage for Space under cooperative agreement 80NSSC24M0177. D.H. would like to acknowledge the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) and the views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official guidance or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense or of the United States Air Force.

References

- Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S. The rise of graphene. Nature materials 2007, 6, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabert, C.J.; Nicol, E.J. Valley-spin polarization in the magneto-optical response of silicene and other similar 2D crystals. Physical Review Letters 2013, 110, 197402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcolm, J.; Nicol, E. Frequency-dependent polarizability, plasmons, and screening in the two-dimensional pseudospin-1 dice lattice. Physical Review B 2016, 93, 165433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D.; Fekete, P.; Anwar, F.; Dahal, D.; Weekes, N. Tailoring plasmon excitations in α-T 3 armchair nanoribbons. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 20577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apalkov, V.; Wang, X.F.; Chakraborty, T. Collective excitations of Dirac electrons in graphene. International Journal of Modern Physics B 2007, 21, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, G.; Balassis, A.; Iurov, A.; Fekete, P. Strongly localized image states of spherical graphitic particles. The Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014, 726303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinea, F.; Le Doussal, P.; Wiese, K.J. Collective excitations in a large-d model for graphene. Physical Review B 2014, 89, 125428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, G.; Iurov, A.; Huang, D.; Pan, W. Tunable surface plasmon instability leading to emission of radiation. Journal of Applied Physics 2015, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, A.; Trushin, M.; Carvalho, A.; Castro Neto, A. Collective excitations in 2D materials. Nature Reviews Physics 2020, 2, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, G.; Iurov, A.; Horing, N. Nonlocal plasma spectrum of graphene interacting with a thick conductor. Physical Review B 2015, 91, 235416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojarro, M.; Carrillo-Bastos, R.; Maytorena, J.A. Hyperbolic plasmons in massive tilted two-dimensional Dirac materials. Physical Review B 2022, 105, L201408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.; Carrillo-Bastos, R.; Naumis, G.G. Valley engineering by strain in Kekulé-distorted graphene. Physical Review B 2019, 99, 035411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.; Carrillo-Bastos, R.; Naumis, G.G. Topical Review: Electronic and optical properties ofKekul e and other short wavelength spatialmodulated textures of graphene. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, S.A.; Naumis, G.G. Electronic and optical conductivity of kekulé-patterned graphene: Intravalley and intervalley transport. Physical Review B 2020, 101, 205413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Application of the WKB theory to investigate electron tunneling in Kek-Y graphene. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbotte, J.; Bryenton, K.; Nicol, E. Optical properties of a semi-Dirac material. Physical Review B 2019, 99, 115406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojarro, M.; Carrillo-Bastos, R.; Maytorena, J.A. Optical properties of massive anisotropic tilted Dirac systems. Physical Review B 2021, 103, 165415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ganguly, S.; Basu, S. Topology and applications of 2D Dirac and semi-Dirac materials. Physical Sciences Reviews 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.Y.; Ba, J.Y.; Duan, H.J.; Deng, M.X.; Wang, Y.M.; Wang, R.Q. Optical conductivity and polarization rotation of type-II semi-Dirac materials. Physical Review B 2023, 107, 155150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauber, T.; San-Jose, P.; Brey, L. Optical conductivity, Drude weight and plasmons in twisted graphene bilayers. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 113050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.; Ghosh, T.K. Dynamical polarization, optical conductivity and plasmon mode of a linear triple component fermionic system. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2022, 34, 255701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojarro, M.; Carrillo-Bastos, R.; Maytorena, J.A. Thermal difference reflectivity of tilted two-dimensional Dirac materials. Physical Review B 2023, 108, L161401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Yan, C.X.; Zhao, Y.H.; Guo, H.; Chang, H.R.; et al. Anisotropic longitudinal optical conductivities of tilted Dirac bands in 1 T′- Mo S 2. Physical Review B 2021, 103, 125425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, A.; Mariani, E.; Portnoi, M.E. Optical absorption in two-dimensional materials with tilted Dirac cones. Physical Review B 2022, 105, 205306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Optical conductivity of gapped α-T 3 materials with a deformed flat band. Physical Review B 2023, 107, 195137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriekhov, D.; Gusynin, V. Optical conductivity of semi-Dirac and pseudospin-1 models: Zitterbewegung approach. Physical Review B 2022, 106, 115143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, N.; Xu, Y.; Li, M.R.; Ma, D.S.; Jovanovic, M.; Yazdani, A.; Parkin, S.S.; Felser, C.; Schoop, L.M.; Ong, N.P.; et al. Catalogue of flat-band stoichiometric materials. Nature 2022, 603, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, I.; Yanagisawa, T.; Kawashima, K. Computational design of flat-band material. Nanoscale research letters 2018, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkelsky, J.G.; Bernevig, B.A.; Coleman, P.; Si, Q.; Paschen, S. Flat bands, strange metals and the Kondo effect. Nature Reviews Materials 2024, 9, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, M.R.; Gardenier, T.S.; Jacobse, P.H.; Van Miert, G.C.; Kempkes, S.N.; Zevenhuizen, S.J.; Smith, C.M.; Vanmaekelbergh, D.; Swart, I. Experimental realization and characterization of an electronic Lieb lattice. Nature physics 2017, 13, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Spracklen, A.; Choudhury, D.; Goldman, N.; Ohberg, P.; Andersson, E.; Thomson, R.R. Observation of a localized flat-band state in a photonic Lieb lattice. Physical review letters 2015, 114, 245504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.X.; Li, S.; Gao, J.H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, F.C. Designing an artificial Lieb lattice on a metal surface. Physical Review B 2016, 94, 241409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, G.W.; Song, I.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Yoo, S.J.; Cho, D.Y.; Rhim, J.W.; Jung, J.; Kim, G.; et al. Atomically Thin Two-Dimensional Kagome Flat Band on the Silicon Surface. ACS nano 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.M.; Franz, M. Topological insulator on the kagome lattice. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2009, 80, 113102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lei, H.; Qi, Y.; Felser, C. Topological quantum materials with kagome lattice. Accounts of Materials Research 2024, 5, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Song, D.; Xia, S.; Xia, S.; Ma, J.; Yan, W.; Hu, Y.; Xu, J.; Leykam, D.; Chen, Z. Photonic flat-band lattices and unconventional light localization. Nanophotonics 2020, 9, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, S.; Goda, M. Three-dimensional flat-band models. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2005, 74, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoux, A.; Morigi, M.; Fuchs, J.N.; Piéchon, F.; Montambaux, G. From dia-to paramagnetic orbital susceptibility of massless fermions. Physical review letters 2014, 112, 026402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, E. Properties of the α-T3 Model. PhD thesis, University of Guelph, 2017.

- Iurov, A.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Peculiar electronic states, symmetries, and berry phases in irradiated α- t 3 materials. Physical Review B 2019, 99, 205135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, L.; Biswas, T. Probing topological signatures in an optically driven α- T 3 lattice. Physical Review B 2023, 107, 085408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.; Ghosh, T.K. Floquet topological phase transition in the α-T 3 lattice. Physical Review B 2019, 99, 205429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Fekete, P.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Klein tunneling of optically tunable Dirac particles with elliptical dispersions. Physical Review Research 2020, 2, 043245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, E.; Nicol, E. Klein tunneling in the α- T 3 model. Physical Review B 2017, 95, 235432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, M.; Tao, Y.; Wang, J. Spin-resolved and charge Josephson diode effects in α-T 3 lattice junctions. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 155405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Dahal, D.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Quantum-statistical theory for laser-tuned transport and optical conductivities of dressed electrons in α- T 3 materials. Physical Review B 2020, 101, 035129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, E.; Nicol, E. Magnetic properties of the α-T 3 model: Magneto-optical conductivity and the Hofstadter butterfly. Physical Review B 2016, 94, 125435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Biswas, T.; Basu, S. Effect of magnetic field on the electronic properties of an α- T 3 ring. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 085423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Basu, S. Spin and charge persistent currents in a Kane Mele α-T3 quantum ring. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leykam, D.; Andreanov, A.; Flach, S. Artificial flat band systems: from lattice models to experiments. Advances in Physics: X 2018, 3, 1473052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, S.; Kibis, O.; Pervishko, A.; Shelykh, I. Transport properties of a two-dimensional electron gas dressed by light. Physical Review B 2015, 91, 155312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibis, O.; Dini, K.; Iorsh, I.; Shelykh, I. All-optical band engineering of gapped Dirac materials. Physical Review B 2017, 95, 125401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D.; Tse, W.K.; Blaise, K.; Ejiogu, C. Floquet engineering of tilted and gapped Dirac bandstructure in 1T′-MoS 2. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 21348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibis, O. Metal-insulator transition in graphene induced by circularly polarized photons. Physical Review B 2010, 81, 165433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Mattis, M.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Floquet Modification of the Bandgaps and Energy Spectrum in Flat-Band Pseudospin-1 Dirac Materials. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristinsson, K.; Kibis, O.V.; Morina, S.; Shelykh, I.A. Control of electronic transport in graphene by electromagnetic dressing. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurov, A.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Exchange and correlation energies in silicene illuminated by circularly polarized light. Journal of Modern Optics 2017, 64, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Lai, Y.; Chiu, Y.H.; Lin, M.F. Landau levels in graphene. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures 2008, 40, 1722–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinea, F.; Castro Neto, A.; Peres, N. Electronic states and Landau levels in graphene stacks. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2006, 73, 245426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, G.; Iurov, A.; Huang, D.; Zhemchuzhna, L. Revealing Hofstadter spectrum for graphene in a periodic potential. Physical Review B 2014, 89, 241407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezawa, M. Quantum Hall effects in silicene. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2012, 81, 064705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabert, C.J.; Nicol, E.J. Magneto-optical conductivity of silicene and other buckled honeycomb lattices. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2013, 88, 085434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuc, A.; Heine, T. The electronic structure calculations of two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides in the presence of external electric and magnetic fields. Chemical Society Reviews 2015, 44, 2603–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.Y.; Zhou, B.T.; He, J.J.; Yuan, N.F.; Zhang, T.; Law, K.T. Magnetic field driven nodal topological superconductivity in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Communications Physics 2018, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, J.D.; Nicol, E.J. Magneto-optics of massless Kane fermions: Role of the flat band and unusual Berry phase. Physical Review B 2015, 92, 035118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabert, C.; Carbotte, J.; Nicol, E. Optical and transport properties in three-dimensional Dirac and Weyl semimetals. Physical Review B 2016, 93, 085426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappoport, T.G.; Uchoa, B.; Castro Neto, A. Magnetism and magnetotransport in disordered graphene. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2009, 80, 245408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakouri, K.; Vasilopoulos, P.; Vargiamidis, V.; Peeters, F. Spin-and valley-dependent magnetotransport in periodically modulated silicene. Physical Review B 2014, 90, 125444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.F. Magnetotransport properties of 8-Pmmn borophene: effects of Hall field and strain. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2018, 30, 275301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.F.; Dutta, P. Valley-polarized magnetoconductivity and particle-hole symmetry breaking in a periodically modulated α-T 3 lattice. Physical Review B 2017, 96, 045418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Dinh, L.; Vu, T.V.; Hoa, L.T.; Hieu, N.N.; Nguyen, C.V.; Nguyen, H.V.; Kubakaddi, S.; Phuc, H.V. Quantum magnetotransport properties of silicene: Influence of the acoustic phonon correction. Physical Review B 2021, 104, 075445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymchenko, M.; Nikitin, A.Y.; Martin-Moreno, L. Faraday rotation due to excitation of magnetoplasmons in graphene microribbons. ACS nano 2013, 7, 9780–9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, T.N.; Gumbs, G.; Shih, P.H.; Huang, D.; Chiu, C.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Lin, M.F. Peculiar optical properties of bilayer silicene under the influence of external electric and magnetic fields. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, M.; Vasilopoulos, P. Electrically tunable magnetoplasmons in a monolayer of silicene or germanene. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2015, 27, 075303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balassis, A.; Dahal, D.; Gumbs, G.; Iurov, A.; Huang, D.; Roslyak, O. Magnetoplasmons for the α-T3 model with filled Landau levels. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2020, 32, 485301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, E.; Carbotte, J.; Nicol, E. Hall quantization and optical conductivity evolution with variable Berry phase in the α-T 3 model. Physical Review B 2015, 92, 245410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luican, A.; Li, G.; Andrei, E.Y. Quantized Landau level spectrum and its density dependence in graphene. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2011, 83, 041405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekes, N.; Iurov, A.; Zhemchuzhna, L.; Gumbs, G.; Huang, D. Generalized WKB theory for electron tunneling in gapped α- T 3 lattices. Physical Review B 2021, 103, 165429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).