Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Population

Data Collection

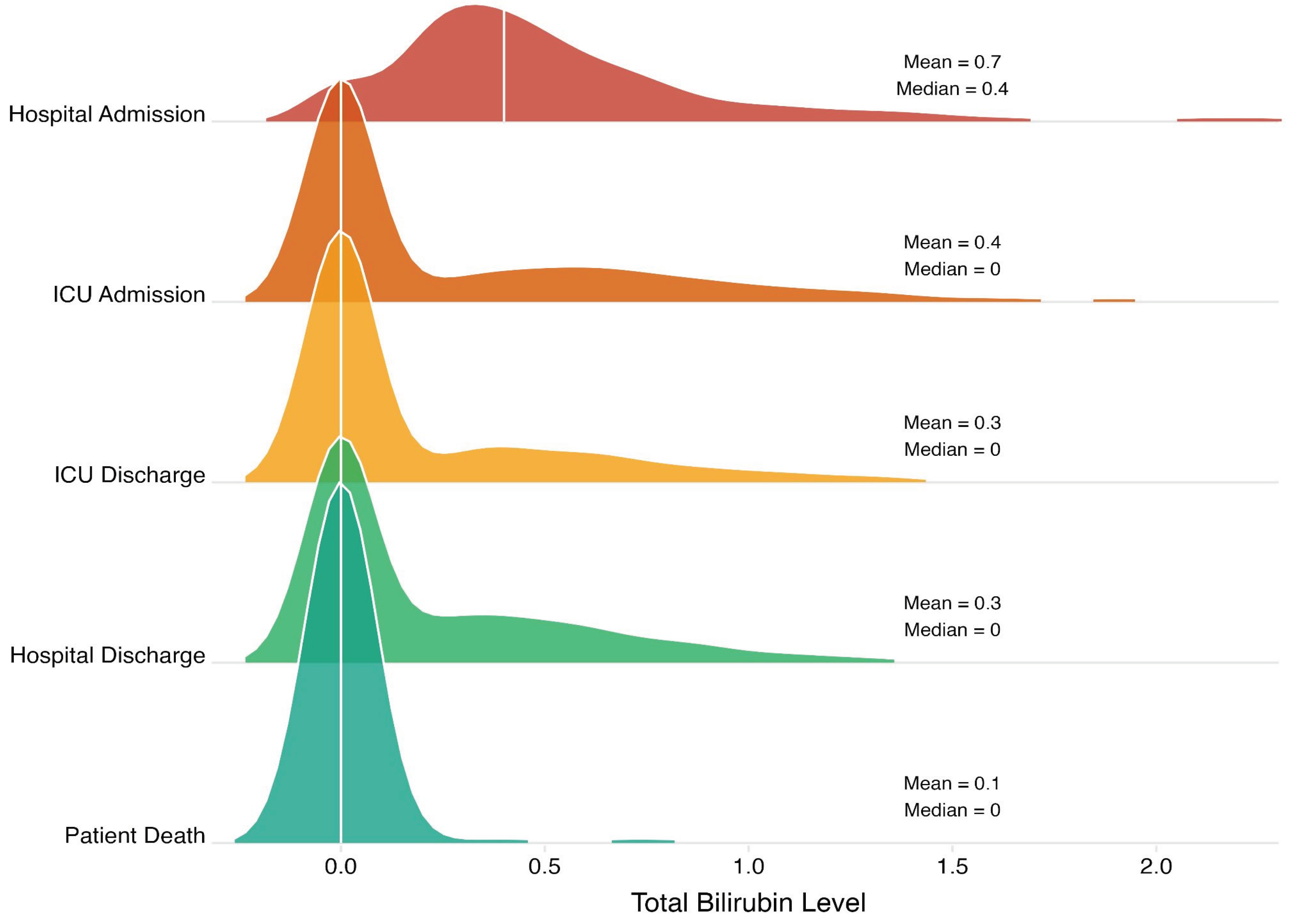

- Hospital admission: first measured bilirubin level after admission to the trauma bay.

- ICU admission: first measured bilirubin level after admission to the ICU.

- ICU discharge: last measured bilirubin level before transfer to a step-down or floor unit.

- Hospital discharge: last measured bilirubin level before discharge.

- Patient death: last measured bilirubin level before death.

Statistical Analyses

Results

Discussion

Key Findings

Implications of Study Findings

Integration with Existing Literature

Strengths and Limitations

Future Perspectives

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kleindienst, A.; Hannon, M.J.; Buchfelder, M.; Verbalis, J.G. Hyponatremia in Neurotrauma: The Role of Vasopressin. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2016, 33, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Jiang, W.; Hasan, M.M.; Agriantonis, G.; Bhatia, N.D.; Shafaee, Z.; Twelker, K.; Whittington, J. Natremia Significantly Influences the Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2025, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.C.; Cai, Y.J.; Wu, J.M.; Wang, X.D.; Song, M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zheng, M.H.; Chen, Y.P.; Lin, Z.; Shi, K.Q. Usefulness of albumin-bilirubin grade for evaluation of long-term prognosis for hepatitis B-related cirrhosis. Journal of viral hepatitis. 2017, 24, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.; Henderson, A.C. Hemolytic Anemia: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. American family physician. 2018, 98, 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.X.; Lv, X.L.; Yan, J. Serum Total Bilirubin Level Is Associated With Hospital Mortality Rate in Adult Critically Ill Patients: A Retrospective Study. Frontiers in medicine. 2021, 8, 697027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chowdhury, J.R.; Chowdhury, N.R. Bilirubin metabolism: Applied physiology. Current Paediatrics. 2006, 16, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C. Heme oxygenase and its products in the nervous system. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2004, 6, 878–887. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, M.; Edelenbos, J. ; Doré; S Bilirubin and Ischemic Stroke: Rendering the Current Paradigm to Better Understand the Protective Effects of Bilirubin. Molecular neurobiology. 2019, 56, 5483–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Kojima, T.; Taki, W. Intracranial heme metabolism and cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003, 34, 2796–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fest, S.; Soldati, R.; Christiansen, N.M.; Zenclussen, M.L.; Kilz, J.; Berger, E.; Starke, S.; Lode, H.N.; Engel, C.; Zenclussen, A.C.; Christiansen, H. Targeting of heme oxygenase-1 as a novel immune regulator of neuroblastoma. International journal of cancer. 2016, 138, 2030–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Seal, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Ghosh Dey, S. Alzheimer’s Disease: A Heme-Aβ Perspective. Accounts of chemical research. 2015, 48, 2556–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitti, M.; Piras, S.; Brondolo, L.; Marinari, U.M.; Pronzato, M.A.; Furfaro, A.L. Heme Oxygenase 1 in the Nervous System: Does It Favor Neuronal Cell Survival or Induce Neurodegeneration? International journal of molecular sciences. 2018, 19, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, K.; Satoh, K.; Ohtaki, H.; Shioda, S.; Miyake, Y.; Shindo, M.; Aruga, T. Elevated plasma levels of bilirubin in patients with neurotrauma reflect its pathophysiological role in free radical scavenging. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2005, 19, 855–860. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, S.; Bang, O.Y.; Saver, J.L.; Starkman, S.; Yun, S.W.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Kim, D.; Ali, L.K.; Shah, S.H.; Ovbiagele, B. Association of serum bilirubin with ischemic stroke outcomes. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases: the official journal of the National Stroke Association. 2008, 17, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco-Ibarra, M.; Estrada-Sánchez, A.M.; Massieu, L.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J. Heme oxygenase-1 induction prevents neuronal damage triggered during mitochondrial inhibition: role of CO and bilirubin. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2009, 41, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.F.; Claus, C.P.; Vreman, H.J.; Wong, R.J.; Noble-Haeusslein, L.J. Heme regulation in traumatic brain injury: relevance to the adult and developing brain. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2005, 25, 1401–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; He, M.; Xu, J. Serum bilirubin level correlates with mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury. Medicine. 2020, 99, e21020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, R.; Yamamoto, Y.; McDonagh, A.F.; Glazer, A.N.; Ames, B.N. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987, 235, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadena, A.J.; Rincon, F. Hypothermia and temperature modulation for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH): pathophysiology and translational applications. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2024, 18, 1289705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, L.; Peng, C.; Bian, C.; Ocak, P.E.; Zhang, J.H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Chen, G.; Luo, Y. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response for Blood-Brain Barrier Protection in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Antioxidants & redox signaling.

- Jia, P.; Peng, Q.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Sonita, H.; Liu, S.; Le, A.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zille, M.; Jiang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Immune-mediated disruption of the blood-brain barrier after intracerebral hemorrhage: Insights and potential therapeutic targets. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 2024, 30, e14853. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Holste, K.G.; Hua, Y.; Keep, R.F.; Xi, G. Brain edema formation and therapy after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurobiology of disease. 2023, 176, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroga, C.S.; Vercelli, A.; Vieira, H.L. Carbon monoxide and the CNS: challenges and achievements. British journal of pharmacology. 2015, 172, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.S.; Figueiredo-Pereira, C.; Vieira, H.L. Carbon monoxide and mitochondria-modulation of cell metabolism, redox response and cell death. Frontiers in physiology. 2015, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamat, P.K.; Ahmad, A.S.; Doré, S. Carbon monoxide attenuates vasospasm and improves neurobehavioral function after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2019, 676, 108117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Keep, R.F.; Hua, Y.; Schallert, T.; Hoff, J.T.; Xi, G. Deferoxamine-induced attenuation of brain edema and neurological deficits in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosurgical focus. 2003, 15, ECP4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | N = 9151 |

|---|---|

| Age | 51.0 (22.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 703 (77%) |

| Female | 212 (23%) |

| Race | |

| Other | 527 (58%) |

| White | 167 (19%) |

| Asian | 133 (15%) |

| Black | 69 (7.7%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 4 (0.4%) |

| American Indian | 1 (0.1%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic Origin | 449 (51%) |

| Hispanic Origin | 433 (49%) |

| Functional Status Before Injury | |

| Independent | 855 (94%) |

| Partially Dependent | 30 (3.3%) |

| Not Applicable | 21 (2.3%) |

| Dependent | 6 (0.7%) |

| Trauma Type | |

| Blunt | 895 (98%) |

| Penetrating | 20 (2.2%) |

| ED Initial GCS | 15.0 (4.1) |

| ISS | 17.0 (10.4) |

| Drug Screen | |

| Not Tested | 383 (42%) |

| No Drugs Detected | 357 (39%) |

| Alcohol Only | 144 (16%) |

| Other Drugs | 27 (3.0%) |

| Alcohol and Other Drugs | 3 (0.3%) |

| ED LOS (hours) | 9.6 (13.6) |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 6.0 (20.6) |

| ICU LOS (days) | 1.3 (7.3) |

| Ventilator Days (days) | 0.0 (6.4) |

| Hospital Disposition | |

| Routine Discharge | 475 (52%) |

| Rehab or Nursing Facility | 184 (20%) |

| Died in Hospital | 126 (14%) |

| Home with services | 49 (5.4%) |

| Left AMA | 29 (3.2%) |

| Transfer to Another Hospital | 23 (2.5%) |

| Other Health Care Facility | 12 (1.3%) |

| Homeless/Shelter | 6 (0.7%) |

| Police Custody/Jail/Prison | 5 (0.5%) |

| Inpatient Psych Care | 4 (0.4%) |

| Total Bilirubin at Time Point, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin Level | Hospital Admission | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Hospital Discharge | Patient Death |

|

Normal (0.0-1.2 mg/dL) |

817 (89.3%) |

833 (91%) |

861 (94.1%) |

888 (97%) |

900 (98.4%) |

|

Hyperbilirubinemia (>1.2 mg/dL) |

98 (10.7%) |

82 (9%) |

54 (5.9%) |

27 (3%) |

15 (1.6%) |

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Hospital Admission | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Hospital Discharge | Patient Death |

| ED LOS | -0.42 (-1.2-0.37) | -0.27 (-1.06-0.53) | -0.16 (-0.63-0.32) | -0.22 (-1.67-1.24) | 0.08 (-1.06-1.21) |

| Hospital LOS | 0.12 (-1.07-1.31) | 0.77 (-0.44-1.97) | 0.12 (-0.6-0.85) | -0.87 (-3.07-1.33) | 0.16 (-1.55-1.88) |

| ICU LOS | -0.07 (-0.49-0.35) | 0.3 (-0.12-0.73) | 0.01 (-0.24-0.26) | -0.48 (-1.26-0.3) | 0.28 (-0.32-0.89) |

| Ventilator Days | 0.06 (-0.31-0.43) | 0.3 (-0.07-0.68) | 0.04 (-0.18-0.27) | -0.33 (-1.02-0.36) | 0.55 (0.01-1.08) * |

| In-Hospital Death | 1.1 (0.96-1.27) | 1.1 (0.95-1.26) | 1.01 (0.88-1.09) | 0.82 (0.51-1.17) | 1.39 (1.12-1.8) ** |

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Outcome | Hospital Admission | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Hospital Discharge | Patient Death |

| ED LOS | -0.51 (-1.25, 0.23) | -0.26 (-1.02, 0.50) | -0.21 (-0.66, 0.23) | -0.30 (-1.68, 1.08) | 0.29 (-0.76, 1.33) |

| Hospital LOS | -0.02 (-1.26, 1.21) | 0.39 (-0.87, 1.66) | 0.13 (-0.61, 0.87) | -1.27 (-3.56, 1.02) | -0.21 (-1.95, 1.53) |

| ICU LOS | -0.11 (-0.51, 0.30) | 0.13 (-0.29, 0.54) | 0.03 (-0.21, 0.27) | -0.61 (-1.36, 0.14) | 0.16 (-0.41, 0.73) |

| Ventilator Days | 0.05 (-0.33, 0.43) | 0.14 (-0.24, 0.53) | 0.05 (-0.17, 0.28) | -0.36 (-1.06, 0.34) | 0.38 (-0.15, 0.91) |

| In-Hospital Death | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03) * | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.02) | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) | -0.01 (-0.04, 0.02) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07) *** |

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hospital Admission | Hospital Discharge | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Patient Death |

| Primary Predictor | |||||

| Total Bilirubin | -0.51 (-1.25, 0.23) | -0.30 (-1.68, 1.08) | -0.26 (-1.02, 0.50) | -0.21 (-0.66, 0.23) | 0.29 (-0.76, 1.33) |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | -0.02 (-0.07, 0.03) | -0.02 (-0.07, 0.03) | -0.02 (-0.07, 0.03) | -0.02 (-0.07, 0.03) | -0.02 (-0.07, 0.03) |

| Gender (Reference = Male) | |||||

| Female | 0.16 (-2.17, 2.49) | 0.08 (-2.25, 2.41) | 0.12 (-2.21, 2.45) | 0.09 (-2.23, 2.42) | 0.11 (-2.22, 2.44) |

| Race (Reference = White) | |||||

| American Indian | -3.80 (-28.44, 20.85) | -3.43 (-28.10, 21.23) | -3.51 (-28.17, 21.15) | -3.48 (-28.14, 21.17) | -3.33 (-27.99, 21.33) |

| Asian | -0.04 (-3.11, 3.04) | -0.04 (-3.12, 3.04) | 0.00 (-3.08, 3.08) | -0.00 (-3.08, 3.07) | -0.04 (-3.11, 3.04) |

| Black | -1.90 (-5.75, 1.94) | -1.95 (-5.80, 1.90) | -1.95 (-5.80, 1.90) | -1.97 (-5.82, 1.88) | -1.98 (-5.83, 1.87) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 78.60 (64.32, 92.88)*** | 78.62 (64.32, 92.91)*** | 78.79 (64.49, 93.08)*** | 78.70 (64.41, 92.98)*** | 78.68 (64.39, 92.97)*** |

| Other | -1.73 (-4.85, 1.40) | -1.74 (-4.87, 1.39) | -1.71 (-4.84, 1.42) | -1.71 (-4.83, 1.42) | -1.75 (-4.88, 1.38) |

| Ethnicity (Reference = Non-Hispanic Origin) | |||||

| Hispanic Origin | 1.54 (-1.21, 4.28) | 1.49 (-1.26, 4.24) | 1.49 (-1.26, 4.24) | 1.49 (-1.26, 4.23) | 1.45 (-1.29, 4.20) |

| Trauma Type (Reference = Blunt) | |||||

| Penetrating | -3.03 (-9.18, 3.12) | -2.89 (-9.04, 3.26) | -2.93 (-9.08, 3.22) | -2.88 (-9.03, 3.27) | -2.84 (-8.99, 3.31) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| AIS Score | -0.79 (-2.42, 0.84) | -0.90 (-2.53, 0.72) | -0.86 (-2.49, 0.77) | -0.89 (-2.51, 0.73) | -0.89 (-2.51, 0.74) |

| Alcohol Level | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) |

| Initial GCS | 0.87 (0.60, 1.13)*** | 0.86 (0.60, 1.12)*** | 0.86 (0.60, 1.12)*** | 0.86 (0.60, 1.12)*** | 0.86 (0.60, 1.13)*** |

| ISS Score | -0.09 (-0.24, 0.06) | -0.09 (-0.24, 0.06) | -0.09 (-0.24, 0.06) | -0.09 (-0.24, 0.06) | -0.09 (-0.24, 0.06) |

| Drug Screen (Reference Group = No Drugs) | |||||

| Alcohol and Other Drugs | -4.38 (-18.53, 9.77) | -4.31 (-18.47, 9.86) | -4.28 (-18.44, 9.88) | -4.32 (-18.48, 9.84) | -4.20 (-18.36, 9.96) |

| Alcohol Only | -0.95 (-3.85, 1.96) | -0.98 (-3.89, 1.94) | -0.93 (-3.84, 1.98) | -1.05 (-3.96, 1.87) | -0.90 (-3.82, 2.02) |

| Not Tested | 0.63 (-1.41, 2.66) | 0.56 (-1.49, 2.62) | 0.68 (-1.36, 2.72) | 0.61 (-1.42, 2.65) | 0.63 (-1.40, 2.67) |

| Other Drugs | 9.76 (4.45, 15.07)*** | 9.69 (4.37, 15.01)*** | 9.78 (4.46, 15.09)*** | 9.70 (4.39, 15.01)*** | 9.77 (4.46, 15.09)*** |

| Functional Status Before Injury (Reference Group = Independent) | |||||

| Not Applicable | -0.87 (-7.30, 5.55) | -0.80 (-7.23, 5.63) | -0.82 (-7.25, 5.61) | -0.80 (-7.23, 5.63) | -0.73 (-7.16, 5.70) |

| Partially Dependent | 1.49 (-3.86, 6.84) | 1.55 (-3.80, 6.91) | 1.51 (-3.84, 6.86) | 1.54 (-3.81, 6.89) | 1.56 (-3.79, 6.91) |

| Dependent | -5.58 (-17.93, 6.77) | -5.45 (-17.81, 6.91) | -5.45 (-17.80, 6.91) | -5.45 (-17.81, 6.90) | -5.45 (-17.80, 6.91) |

| 1Values shown as β coefficient (95% CI). Significance levels: *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. | |||||

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hospital Admission | Hospital Discharge | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Patient Death |

| Primary Predictor | |||||

| Total Bilirubin | -0.02 (-1.26, 1.21) | -1.27 (-3.56, 1.02) | 0.39 (-0.87, 1.66) | 0.13 (-0.61, 0.87) | -0.21 (-1.95, 1.53) |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 0.05 (-0.03, 0.13) | 0.05 (-0.03, 0.13) | 0.05 (-0.03, 0.13) | 0.05 (-0.03, 0.13) | 0.05 (-0.03, 0.13) |

| Gender (Reference = Male) | |||||

| Female | -1.43 (-5.31, 2.45) | -1.48 (-5.35, 2.40) | -1.48 (-5.36, 2.40) | -1.44 (-5.32, 2.44) | -1.45 (-5.33, 2.43) |

| Race (Reference = White) | |||||

| American Indian | -14.45 (-55.55, 26.64) | -14.71 (-55.76, 26.34) | -14.22 (-55.29, 26.86) | -14.37 (-55.44, 26.71) | -14.46 (-55.54, 26.61) |

| Asian | -1.43 (-6.56, 3.70) | -1.40 (-6.53, 3.72) | -1.51 (-6.64, 3.62) | -1.46 (-6.58, 3.67) | -1.44 (-6.57, 3.69) |

| Black | -0.24 (-6.66, 6.17) | -0.19 (-6.59, 6.22) | -0.27 (-6.68, 6.15) | -0.24 (-6.65, 6.17) | -0.24 (-6.65, 6.18) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3.14 (-20.66, 26.95) | 2.94 (-20.85, 26.73) | 2.96 (-20.85, 26.76) | 3.13 (-20.68, 26.93) | 3.14 (-20.67, 26.94) |

| Other | 3.40 (-1.81, 8.61) | 3.33 (-1.88, 8.54) | 3.38 (-1.83, 8.59) | 3.39 (-1.82, 8.60) | 3.42 (-1.79, 8.63) |

| Ethnicity (Reference = Non-Hispanic Origin) | |||||

| Hispanic Origin | -3.27 (-7.84, 1.31) | -3.11 (-7.69, 1.47) | -3.33 (-7.90, 1.25) | -3.29 (-7.86, 1.28) | -3.27 (-7.84, 1.30) |

| Trauma Type (Reference = Blunt) | |||||

| Penetrating | 3.41 (-6.84, 13.66) | 3.31 (-6.93, 13.55) | 3.52 (-6.72, 13.77) | 3.43 (-6.81, 13.67) | 3.40 (-6.84, 13.65) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| AIS Score | 2.99 (0.28, 5.70)* | 2.97 (0.28, 5.67)* | 2.93 (0.22, 5.63)* | 2.98 (0.28, 5.68)* | 2.98 (0.28, 5.68)* |

| Alcohol Level | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.01) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.01) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.01) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.01) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.01) |

| Initial GCS | -1.52 (-1.96, -1.09)*** | -1.52 (-1.96, -1.09)*** | -1.52 (-1.96, -1.09)*** | -1.52 (-1.96, -1.09)*** | -1.53 (-1.96, -1.09)*** |

| ISS Score | 0.06 (-0.19, 0.31) | 0.06 (-0.19, 0.31) | 0.06 (-0.19, 0.31) | 0.06 (-0.19, 0.31) | 0.06 (-0.19, 0.31) |

| Drug Screen (Reference Group = No Drugs) | |||||

| Alcohol and Other Drugs | -4.12 (-27.71, 19.47) | -4.35 (-27.93, 19.22) | -4.08 (-27.66, 19.51) | -4.07 (-27.66, 19.52) | -4.15 (-27.74, 19.44) |

| Alcohol Only | 2.33 (-2.50, 7.17) | 2.21 (-2.63, 7.05) | 2.31 (-2.52, 7.15) | 2.40 (-2.45, 7.24) | 2.30 (-2.54, 7.15) |

| Not Tested | -1.82 (-5.22, 1.57) | -2.10 (-5.52, 1.33) | -1.91 (-5.31, 1.50) | -1.81 (-5.21, 1.58) | -1.82 (-5.22, 1.57) |

| Other Drugs | -1.97 (- -10.82, 6.88) | -2.21 (-11.06, 6.64) | -2.02 (- -10.87, 6.83) | -1.94 (- -10.79, 6.91) | -1.99 (- -10.84, 6.86) |

| Functional Status Before Injury (Reference Group = Independent) | |||||

| Not Applicable | -17.88 (-28.59, -7.16)** | -18.00 (-28.70, -7.29)** | -17.79 (-28.50, -7.08)** | -17.85 (-28.56, -7.14)** | -17.90 (-28.61, -7.19)** |

| Partially Dependent | 0.29 (-8.63, 9.20) | 0.17 (-8.73, 9.08) | 0.40 (-8.52, 9.32) | 0.32 (-8.60, 9.23) | 0.30 (-8.61, 9.22) |

| Dependent | -9.73 (-30.32, 10.86) | -9.93 (-30.50, 10.64) | -9.65 (-30.22, 10.93) | -9.69 (-30.27, 10.90) | -9.68 (-30.27, 10.90) |

| 1Values shown as β coefficient (95% CI). Significance levels: *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. | |||||

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hospital Admission | Hospital Discharge | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Patient Death |

| Primary Predictor | |||||

| Total Bilirubin | -0.11 (-0.51, 0.30) | -0.61 (-1.36, 0.14) | 0.13 (-0.29, 0.54) | 0.03 (-0.21, 0.27) | 0.16 (-0.41, 0.73) |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 0.00 (-0.03, 0.03) | 0.00 (-0.02, 0.03) | 0.00 (-0.03, 0.03) | 0.00 (-0.03, 0.03) | 0.00 (-0.03, 0.03) |

| Gender (Reference = Male) | |||||

| Female | -0.78 (-2.05, 0.50) | -0.81 (-2.08, 0.46) | -0.81 (-2.08, 0.47) | -0.79 (-2.06, 0.48) | -0.78 (-2.05, 0.49) |

| Race (Reference = White) | |||||

| American Indian | -6.50 (-19.98, 6.99) | -6.54 (-20.00, 6.93) | -6.34 (-19.82, 7.15) | -6.39 (-19.88, 7.09) | -6.38 (-19.87, 7.10) |

| Asian | -0.93 (-2.62, 0.75) | -0.92 (-2.61, 0.76) | -0.96 (-2.65, 0.72) | -0.94 (-2.63, 0.74) | -0.93 (-2.61, 0.75) |

| Black | -0.02 (-2.13, 2.08) | -0.01 (-2.11, 2.09) | -0.04 (-2.15, 2.06) | -0.03 (-2.14, 2.07) | -0.04 (-2.15, 2.06) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.32 (-7.49, 8.14) | 0.24 (-7.56, 8.04) | 0.28 (-7.54, 8.09) | 0.33 (-7.48, 8.15) | 0.35 (-7.47, 8.16) |

| Other | -0.48 (-2.19, 1.23) | -0.52 (-2.22, 1.19) | -0.49 (-2.20, 1.22) | -0.48 (-2.19, 1.23) | -0.49 (-2.21, 1.22) |

| Ethnicity (Reference = Non-Hispanic Origin) | |||||

| Hispanic Origin | 0.40 (-1.10, 1.90) | 0.46 (-1.04, 1.96) | 0.36 (-1.14, 1.86) | 0.38 (-1.12, 1.88) | 0.38 (-1.12, 1.88) |

| Trauma Type (Reference = Blunt) | |||||

| Penetrating | 3.72 (0.35, 7.08)* | 3.70 (0.34, 7.06)* | 3.79 (0.42, 7.15)* | 3.75 (0.39, 7.12)* | 3.76 (0.40, 7.13)* |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| AIS Score | 0.95 (0.06, 1.84)* | 0.92 (0.04, 1.81)* | 0.91 (0.02, 1.79)* | 0.93 (0.04, 1.81)* | 0.93 (0.04, 1.82)* |

| Alcohol Level | -0.00 (-0.01, -0.00)* | -0.00 (-0.01, -0.00)* | -0.00 (-0.01, -0.00)* | -0.00 (-0.01, -0.00)* | -0.00 (-0.01, -0.00)* |

| Initial GCS | -0.57 (-0.71, -0.43)*** | -0.57 (-0.71, -0.43)*** | -0.57 (-0.72, -0.43)*** | -0.57 (-0.72, -0.43)*** | -0.57 (-0.71, -0.43)*** |

| ISS Score | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* |

| Drug Screen (Reference Group = No Drugs) | |||||

| Alcohol and Other Drugs | -3.54 (-11.29, 4.20) | -3.63 (-11.36, 4.10) | -3.50 (-11.25, 4.24) | -3.51 (-11.25, 4.24) | -3.49 (-11.23, 4.26) |

| Alcohol Only | 0.99 (-0.59, 2.58) | 0.93 (-0.65, 2.52) | 0.99 (-0.60, 2.57) | 1.01 (-0.59, 2.60) | 1.02 (-0.57, 2.61) |

| Not Tested | -0.30 (-1.41, 0.81) | -0.43 (-1.55, 0.69) | -0.32 (-1.44, 0.79) | -0.30 (-1.41, 0.82) | -0.30 (-1.41, 0.82) |

| Other Drugs | -1.40 (-4.31, 1.50) | -1.52 (-4.42, 1.38) | -1.42 (-4.32, 1.49) | -1.40 (-4.30, 1.51) | -1.39 (-4.29, 1.52) |

| Functional Status Before Injury (Reference Group = Independent) | |||||

| Not Applicable | -5.42 (-8.93, -1.90)** | -5.45 (-8.97, -1.94)** | -5.37 (-8.88, -1.85)** | -5.39 (-8.91, -1.87)** | -5.37 (-8.89, -1.86)** |

| Partially Dependent | -1.28 (-4.21, 1.64) | -1.32 (-4.24, 1.60) | -1.23 (-4.15, 1.70) | -1.26 (-4.18, 1.67) | -1.27 (-4.20, 1.65) |

| Dependent | -2.12 (-8.88, 4.64) | -2.18 (-8.93, 4.57) | -2.06 (-8.81, 4.70) | -2.07 (-8.83, 4.68) | -2.11 (-8.87, 4.65) |

| 1Values shown as β coefficient (95% CI). Significance levels: *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. | |||||

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hospital Admission | Hospital Discharge | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Patient Death |

| Primary Predictor | |||||

| Total Bilirubin | 0.05 (-0.33, 0.43) | -0.36 (-1.06, 0.34) | 0.14 (-0.24, 0.53) | 0.05 (-0.17, 0.28) | 0.38 (-0.15, 0.91) |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.04) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.04) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.04) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.04) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.04) |

| Gender (Reference = Male) | |||||

| Female | -1.01 (-2.19, 0.18) | -1.01 (-2.20, 0.17) | -1.02 (-2.20, 0.17) | -1.00 (-2.19, 0.18) | -0.97 (-2.16, 0.21) |

| Race (Reference = White) | |||||

| American Indian | -8.18 (-20.72, 4.36) | -8.30 (-20.83, 4.22) | -8.15 (-20.68, 4.39) | -8.20 (-20.74, 4.34) | -8.17 (-20.69, 4.35) |

| Asian | -0.89 (-2.46, 0.67) | -0.88 (-2.45, 0.68) | -0.92 (-2.48, 0.65) | -0.90 (-2.47, 0.66) | -0.87 (-2.44, 0.69) |

| Black | -1.51 (-3.47, 0.45) | -1.49 (-3.44, 0.47) | -1.51 (-3.47, 0.45) | -1.50 (-3.46, 0.46) | -1.52 (-3.47, 0.44) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | -1.12 (-8.39, 6.14) | -1.19 (-8.45, 6.07) | -1.20 (-8.46, 6.07) | -1.14 (-8.40, 6.13) | -1.11 (-8.36, 6.15) |

| Other | -0.09 (-1.68, 1.50) | -0.11 (-1.70, 1.48) | -0.09 (-1.68, 1.50) | -0.09 (-1.68, 1.50) | -0.12 (-1.71, 1.47) |

| Ethnicity (Reference = Non-Hispanic Origin) | |||||

| Hispanic Origin | -0.33 (-1.72, 1.07) | -0.27 (-1.67, 1.12) | -0.34 (-1.74, 1.06) | -0.33 (-1.72, 1.07) | -0.32 (-1.71, 1.07) |

| Trauma Type (Reference = Blunt) | |||||

| Penetrating | 0.98 (-2.15, 4.11) | 0.94 (-2.19, 4.06) | 1.00 (-2.12, 4.13) | 0.97 (-2.16, 4.10) | 0.99 (-2.13, 4.11) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| AIS Score | 0.90 (0.07, 1.73)* | 0.91 (0.09, 1.73)* | 0.89 (0.06, 1.72)* | 0.91 (0.09, 1.73)* | 0.92 (0.10, 1.75)* |

| Alcohol Level | -0.00 (-0.01, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.01, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.01, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.01, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.01, 0.00) |

| Initial GCS | -0.67 (-0.80, -0.54)*** | -0.67 (-0.80, -0.53)*** | -0.67 (-0.80, -0.53)*** | -0.67 (-0.80, -0.54)*** | -0.66 (-0.80, -0.53)*** |

| ISS Score | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.09) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.09) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.09) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.09) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.09) |

| Drug Screen (Reference Group = No Drugs) | |||||

| Alcohol and Other Drugs | -1.81 (-9.01, 5.39) | -1.89 (-9.09, 5.30) | -1.81 (-9.01, 5.39) | -1.81 (-9.01, 5.39) | -1.76 (-8.95, 5.43) |

| Alcohol Only | 0.58 (-0.89, 2.06) | 0.55 (-0.93, 2.02) | 0.57 (-0.90, 2.05) | 0.61 (-0.87, 2.08) | 0.64 (-0.84, 2.12) |

| Not Tested | 0.56 (-0.48, 1.59) | 0.48 (-0.57, 1.52) | 0.53 (-0.51, 1.56) | 0.56 (-0.47, 1.60) | 0.56 (-0.47, 1.59) |

| Other Drugs | 0.08 (-2.62, 2.78) | 0.01 (- -2.69, 2.72) | 0.06 (-2.64, 2.76) | 0.09 (-2.61, 2.79) | 0.12 (-2.58, 2.82) |

| Functional Status Before Injury (Reference Group = Independent) | |||||

| Not Applicable | -3.99 (-7.26, -0.72)* | -4.03 (-7.30, -0.77)* | -3.97 (-7.23, -0.70)* | -3.99 (-7.26, -0.72)* | -3.95 (-7.21, -0.68)* |

| Partially Dependent | -2.11 (-4.83, 0.61) | -2.15 (-4.87, 0.57) | -2.08 (-4.80, 0.65) | -2.10 (-4.82, 0.62) | -2.14 (-4.86, 0.57) |

| Dependent | -3.18 (-9.46, 3.11) | -3.25 (-9.53, 3.02) | -3.17 (-9.45, 3.11) | -3.18 (-9.46, 3.10) | -3.26 (-9.53, 3.01) |

| 1Values shown as β coefficient (95% CI). Significance levels: *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. | |||||

| Total Bilirubin Measurement Timing1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hospital Admission | Hospital Discharge | ICU Admission | ICU Discharge | Patient Death |

| Primary Predictor | |||||

| Total Bilirubin | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03)* | -0.01 (-0.04, 0.02) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.02) | 0.00 (-0.01, 0.01) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07)*** |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)*** | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)*** | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)*** | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)*** | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)*** |

| Gender (Reference = Male) | |||||

| Female | -0.05 (-0.10, 0.00) | -0.05 (-0.10, 0.00) | -0.05 (-0.10, 0.00) | -0.05 (-0.10, 0.01) | -0.04 (-0.09, 0.01) |

| Race (Reference = White) | |||||

| American Indian | -0.26 (-0.79, 0.27) | -0.28 (-0.81, 0.26) | -0.27 (-0.80, 0.26) | -0.27 (-0.80, 0.26) | -0.27 (-0.79, 0.26) |

| Asian | -0.01 (-0.08, 0.06) | -0.01 (-0.08, 0.06) | -0.01 (-0.08, 0.06) | -0.01 (-0.08, 0.06) | -0.01 (-0.07, 0.06) |

| Black | -0.09 (-0.17, -0.01)* | -0.09 (-0.17, -0.01)* | -0.09 (-0.17, -0.01)* | -0.09 (-0.17, -0.01)* | -0.09 (-0.17, -0.01)* |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | -0.08 (-0.39, 0.23) | -0.08 (-0.39, 0.23) | -0.08 (-0.39, 0.22) | -0.08 (-0.39, 0.23) | -0.08 (-0.38, 0.23) |

| Other | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.07) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.07) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.07) | 0.01 (-0.06, 0.07) | 0.00 (-0.07, 0.07) |

| Ethnicity (Reference = Non-Hispanic Origin) | |||||

| Hispanic Origin | -0.02 (-0.08, 0.04) | -0.01 (-0.07, 0.04) | -0.02 (-0.08, 0.04) | -0.02 (-0.08, 0.04) | -0.02 (-0.07, 0.04) |

| Trauma Type (Reference = Blunt) | |||||

| Penetrating | 0.11 (-0.02, 0.24) | 0.10 (-0.03, 0.24) | 0.11 (-0.03, 0.24) | 0.11 (-0.03, 0.24) | 0.11 (-0.02, 0.24) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| AIS Score | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.06) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.06) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.06) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.06) | 0.03 (-0.01, 0.06) |

| Alcohol Level | -0.00 (-0.00, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.00, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.00, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.00, 0.00) | -0.00 (-0.00, 0.00) |

| Initial GCS | -0.03 (-0.03, -0.02)*** | -0.03 (-0.03, -0.02)*** | -0.03 (-0.03, -0.02)*** | -0.03 (-0.03, -0.02)*** | -0.03 (-0.03, -0.02)*** |

| ISS Score | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01)*** |

| Drug Screen (Reference Group = No Drugs) | |||||

| Alcohol and Other Drugs | -0.03 (-0.33, 0.28) | -0.03 (-0.34, 0.27) | -0.03 (-0.34, 0.28) | -0.03 (-0.34, 0.28) | -0.02 (-0.32, 0.28) |

| Alcohol Only | -0.04 (-0.11, 0.02) | -0.05 (-0.11, 0.02) | -0.04 (-0.11, 0.02) | -0.04 (-0.11, 0.02) | -0.04 (-0.10, 0.03) |

| Not Tested | 0.00 (-0.04, 0.04) | -0.00 (-0.05, 0.04) | -0.00 (-0.05, 0.04) | 0.00 (-0.04, 0.04) | 0.00 (-0.04, 0.04) |

| Other Drugs | 0.05 (-0.07, 0.16) | 0.05 (-0.07, 0.16) | 0.05 (-0.07, 0.16) | 0.05 (-0.07, 0.16) | 0.05 (-0.06, 0.17) |

| Functional Status Before Injury (Reference Group = Independent) | |||||

| Not Applicable | 0.54 (0.41, 0.68)*** | 0.54 (0.40, 0.68)*** | 0.54 (0.40, 0.68)*** | 0.54 (0.40, 0.68)*** | 0.55 (0.41, 0.68)*** |

| Partially Dependent | -0.06 (-0.17, 0.06) | -0.06 (-0.18, 0.06) | -0.06 (-0.17, 0.06) | -0.06 (-0.17, 0.06) | -0.06 (-0.18, 0.05) |

| Dependent | 0.04 (-0.23, 0.30) | 0.03 (-0.24, 0.30) | 0.03 (-0.23, 0.30) | 0.03 (-0.23, 0.30) | 0.02 (-0.24, 0.29) |

| 1Values shown as OR (95% CI). Significance levels: *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).