Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

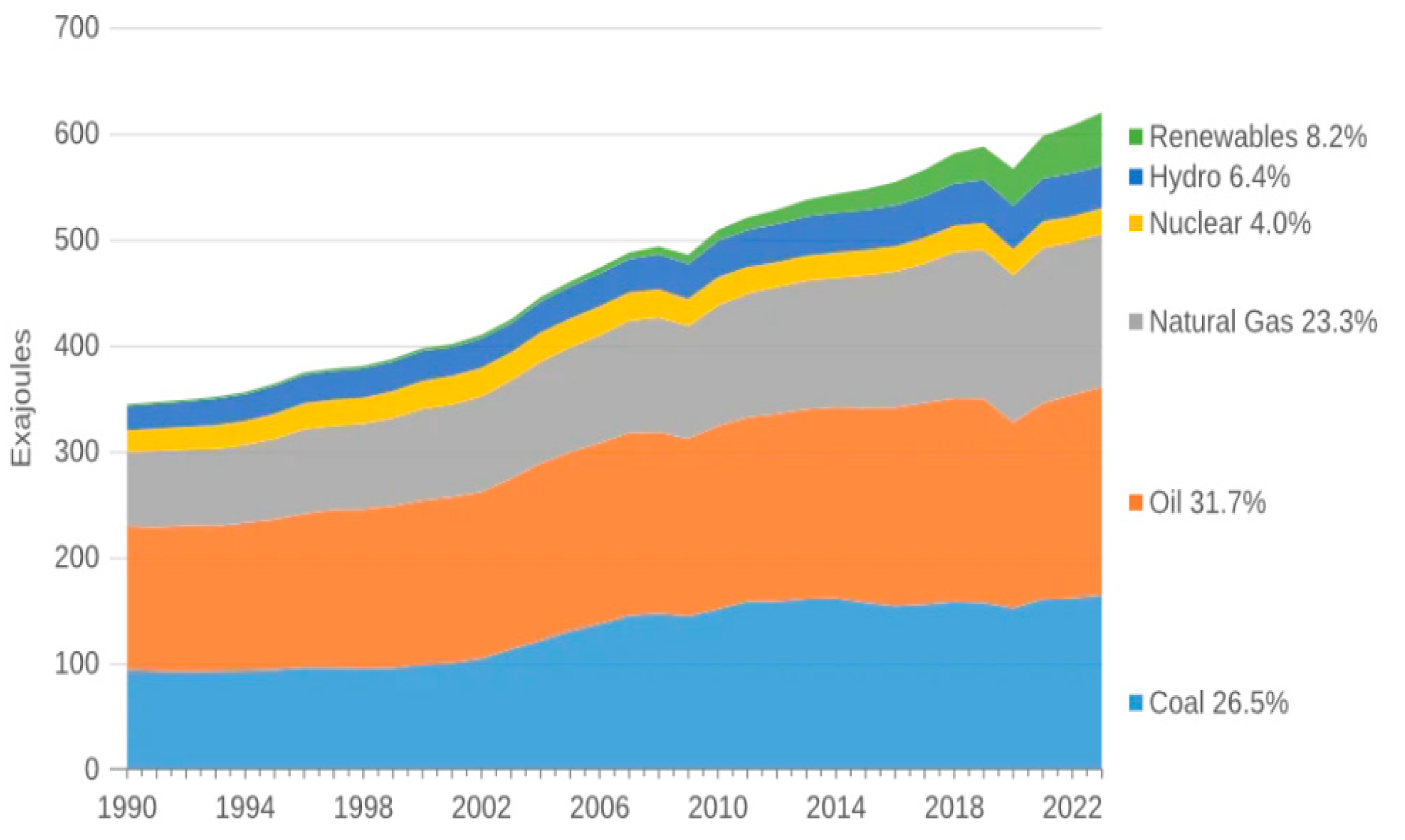

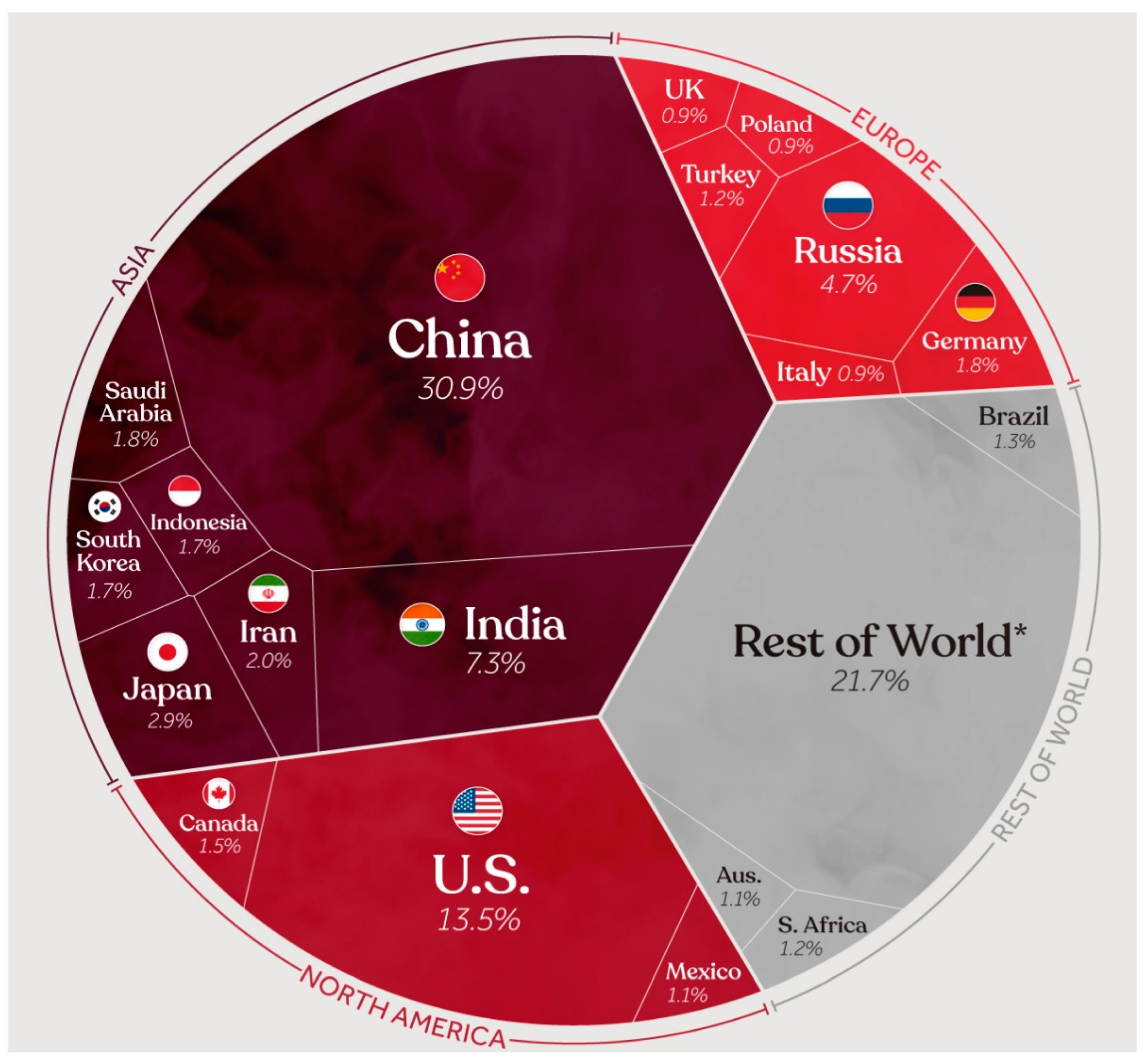

1. Introduction

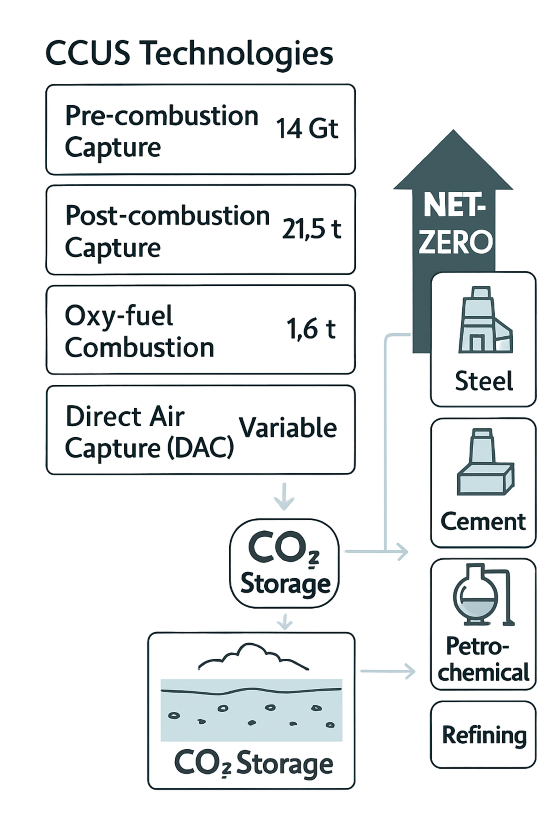

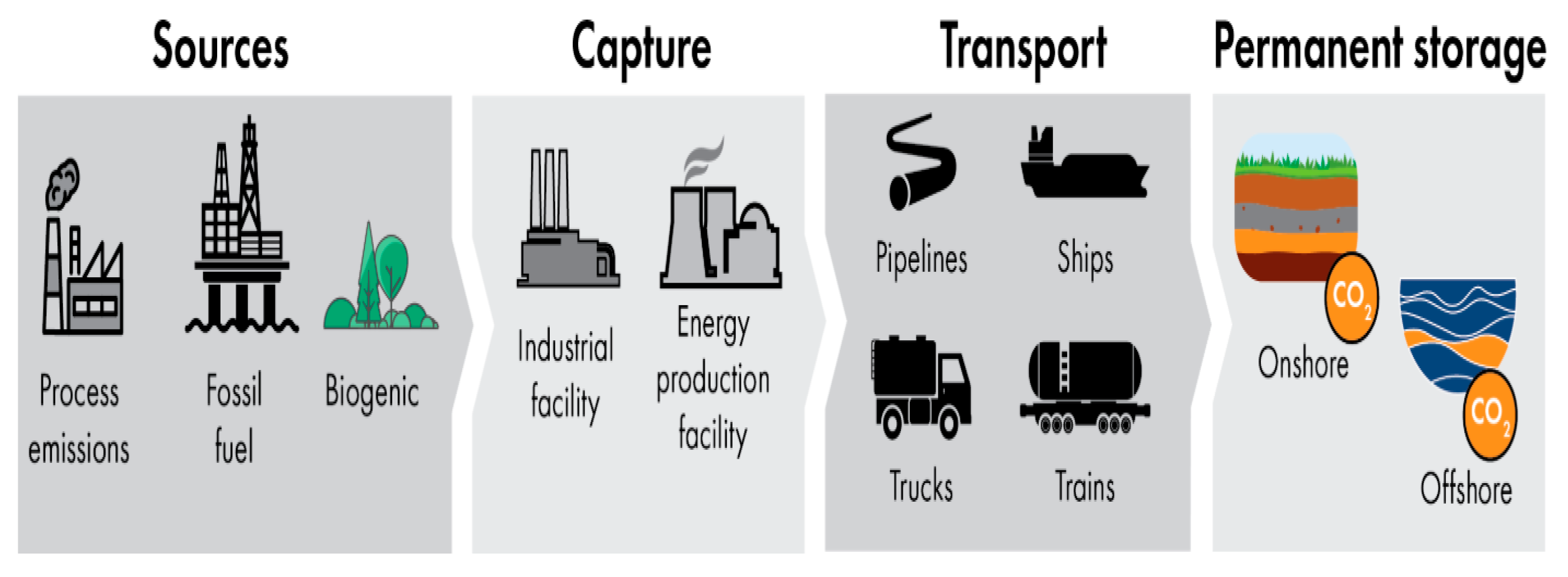

2. Carbon Capture Technologies

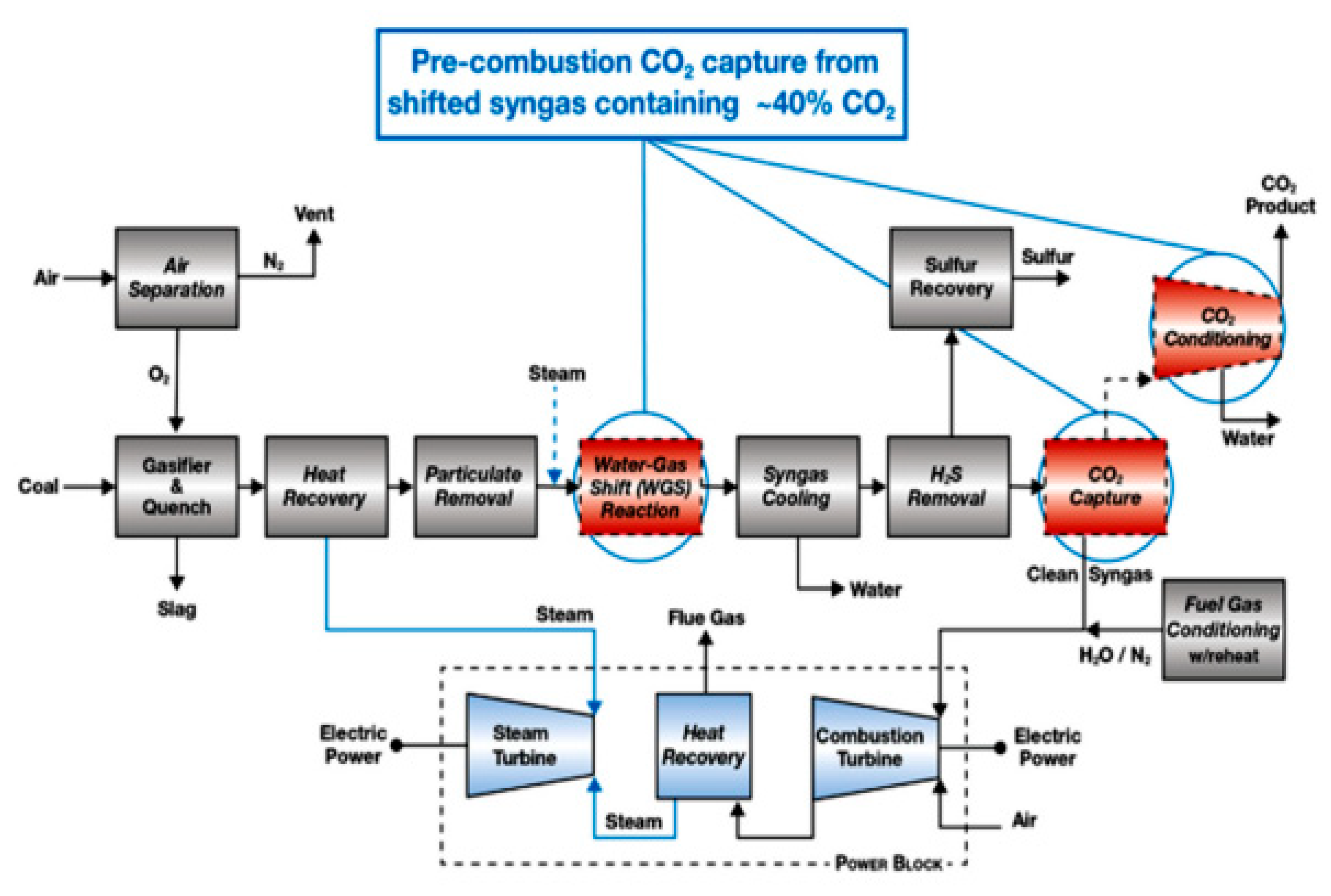

2.1. Pre-Combustion Capture

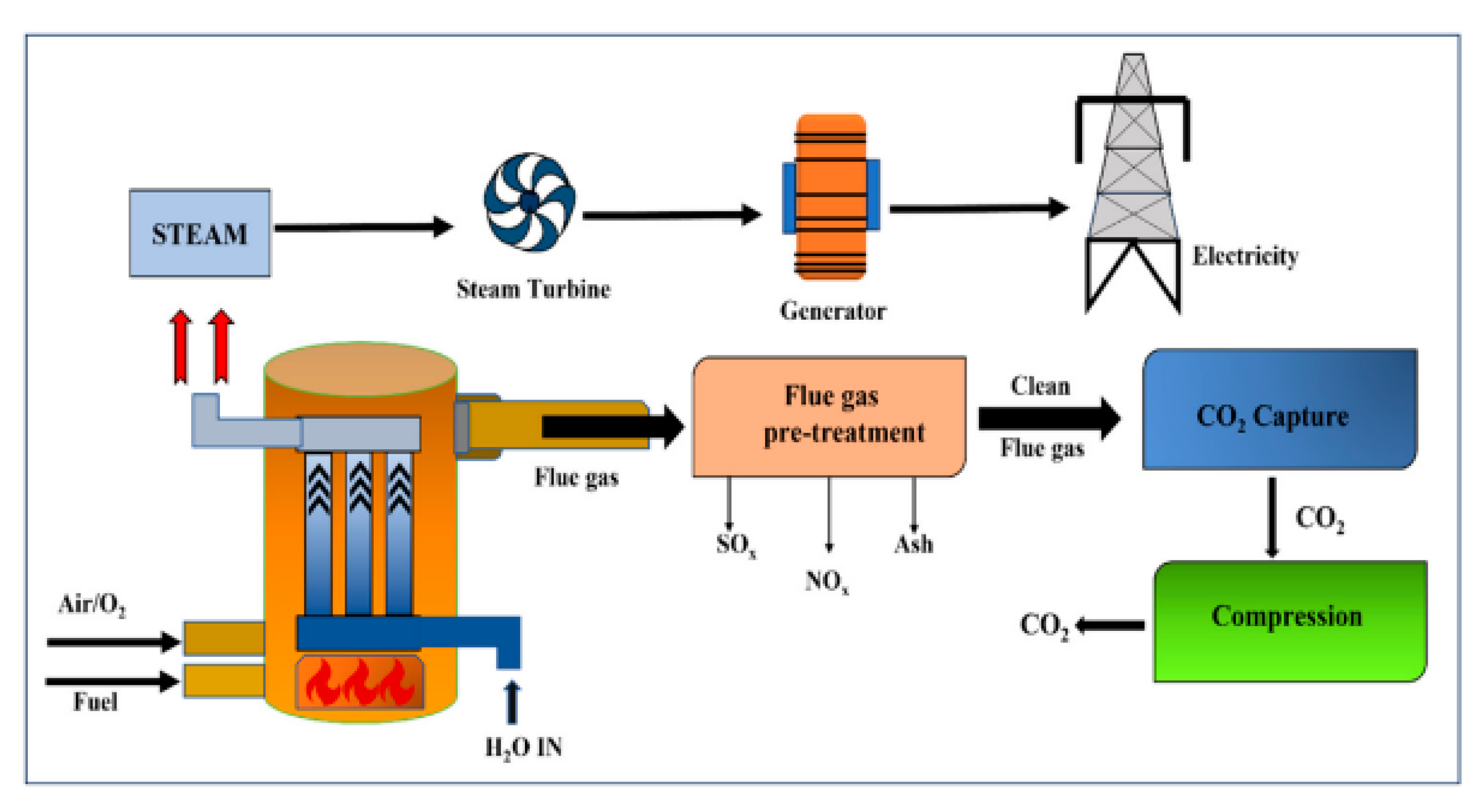

2.2. Post-Combustion Capture

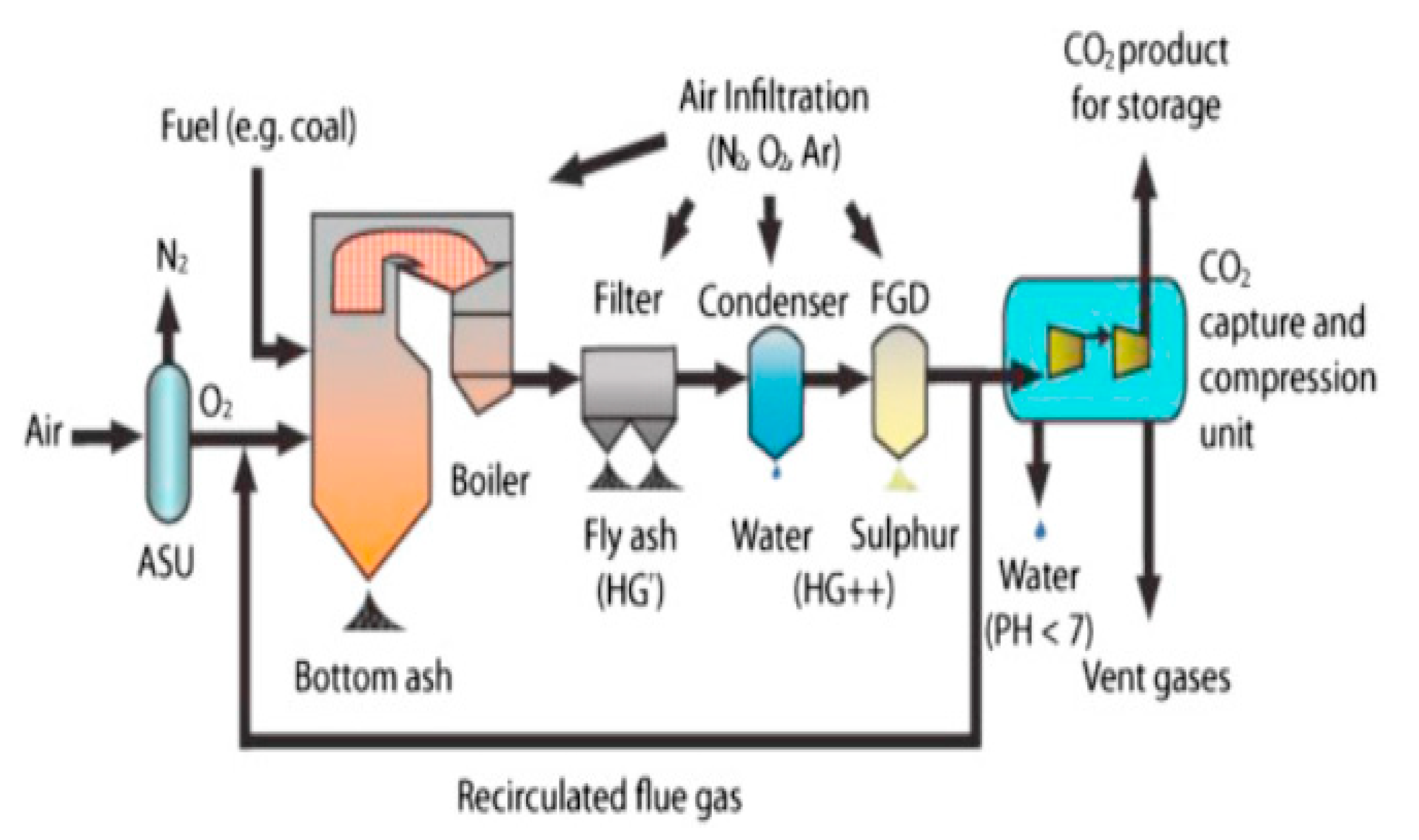

2.3. Oxy-Fuel Combustion

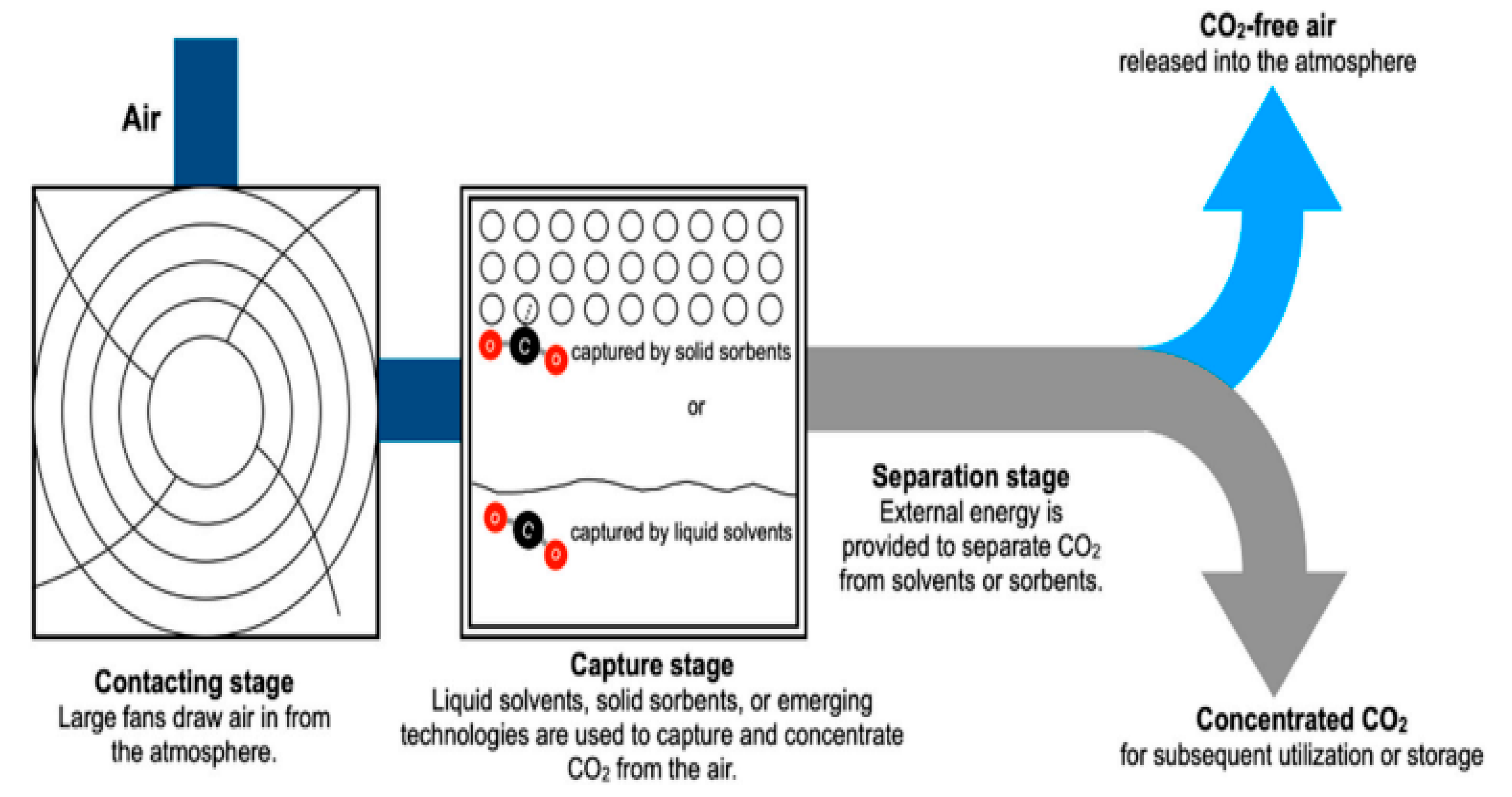

2.4. Direct Air Capture (DAC)

2.5. Case Studies and Real-World Application of CCS Technologies

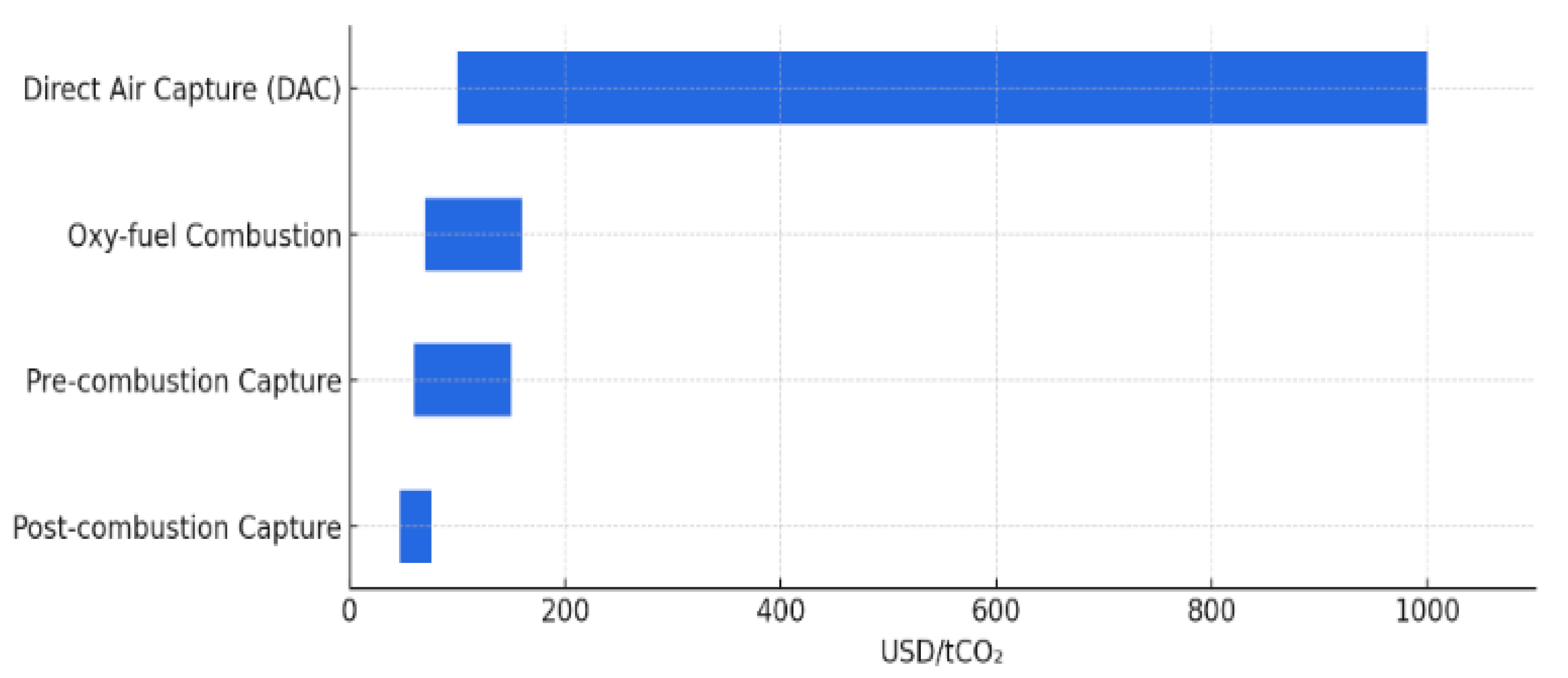

2.6. Cost Estimates for Carbon Capture and Storage Systems

3. The Role of Carbon Capture Technologies in Mitigating Emissions

- Retrofitting existing industrial facilities or power plants to continue operation while capturing their CO₂ emissions.

- Substantially lowering emissions from energy-intensive sectors that are difficult to decarbonize, including cement, steel, and chemicals.

- Supporting the low-carbon hydrogen economy, which can facilitate decarbonization across industry, heavy transport, and shipping.

- Removing CO₂ from the atmosphere to offset unavoidable or hard-to-abate emissions, for instance, through Bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) or Direct Air Capture (DAC).

3.1. CCS Role in Decarbonizing the Industrial Sector

3.1.1. Decarbonizing the Iron and Steel Industry

3.1.2. Decarbonizing from the Cement Industry

3.1.3. Decarbonizing the Petrochemical and Oil Refining Industries

4. Integration of CCUS with Renewable Energy Systems

4.1. Solar and Wind Energy-Powered CCUS

4.2. Geothermal Energy and CO₂ Utilization

4.3. Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)

4.4. CCUS in Low-Carbon Hydrogen Production

4.5. Scalability and Commercialization

5. Challenges of CCS Technologies

5.1. High Costs and Energy Demand of CCUS Technologies

5.2. Infrastructure Challenges

5.3. Need for Improved Materials and Energy Efficiency

6. Policies and Incentives for Widespread Adoption of CCS

6.1. Public Funding

6.2. Strategic Signalling

6.3. Cross-Border Collaboration

7. Conclusion and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Energy Institute. Energy Institute Releases 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Romm, J. Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Elegbeleye, I.F. Studies of Interaction of Dye Molecules with TiO₂ Brookite Clusters for Application in Dye Sensitized Solar Cells; Doctoral Dissertation, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa, 2019.

- Elegbeleye, I.; Oguntona, O.; Elegbeleye, F. Green Hydrogen: Pathway to Net Zero Green House Gas Emission and Global Climate Change Mitigation. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 29. [CrossRef]

- Olaleru, S.A.; Kirui, J.; Elegbeleye, F.; Aniyikaiye, T. Green Technology Solution to Global Climate Change Mitigation. Energy, Environment, and Storage Journal 2021, 1, 26–41. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, T.; Chaturvedi, S. Climate Refugees and Security: Conceptualizations, Categories, and Contestations. In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society; Dryzek, J.S., Norgaard, R.B., Schlosberg, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012.

- Doney, S.C.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Duffy, J.E.; Barry, J.P.; Chan, F.; English, C.A.; Galindo, H.M.; Grebmeier, J.M.; Hollowed, A.B.; Knowlton, N.; Polovina, J. Climate Change Impacts on Marine Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012, 4, 11–37.

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; Cox, P.M. Health and Climate Change: Policy Responses to Protect Public Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914.

- Hashim, J.H.; Hashim, Z. Climate Change, Extreme Weather Events, and Human Health Implications in the Asia Pacific Region. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2016, 28, 8S–14S.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Climate Change Indicators: Atmospheric Concentrations of Greenhouse Gases, 2016. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-atmospheric-concentrations-greenhouse-gases (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- MIT Climate Portal. Carbon Capture. Available online: https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/carbon-capture (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Marsh, N. The Significance of CCS in Achieving Net Zero Emissions. SINTEF Energy Research, 2024. Available online: https://blog.sintef.com/sintefenergy/the-significance-of-ccs-in-achieving-net-zero-emissions/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Campbell, M. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 801–807.

- Singh, A.; Stéphenne, K. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 1678–1685.

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Petra Nova–W.A. Parish Project, Office of Fossil Energy, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Available online: http://energy.gov/fe/petra-nova-wa-parish-project (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Petra Nova W.A. Parish Fact Sheet: Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage Project. Carbon Capture and Sequestration Technologies Program at MIT, 2016. Available online: https://sequestration.mit.edu/tools/projects/wa_parish.html (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Membrane Technology & Research (MTR). Polaris™ Membrane: CO₂ Removal from Syngas. Available online: http://www.mtrinc.com/co2_removal_from_syngas.html (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Chemical Processing. Air Products and NTNU Enter Licensing Agreement for Carbon Capture Technology, 2017. Available online: https://www.chemicalprocessing.com/environmental-protection/air-products-ntnu-carbon-capture (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Noothout, P.; Wiersma, F.; Hurtado, O.; Roelofsen, P.; Macdonald, D. CO₂ Pipeline Infrastructure, IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme (IEAGHG), 2014. Available online: http://ieaghg.org/docs/General_Docs/Reports/2013-18.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Brownsort, P. Ship Transport of CO₂ for Enhanced Oil Recovery—Literature Survey; Scottish Carbon Capture & Storage (SCCS), January 2015. Available online: https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/publications/ship-transport-of-co-for-enhanced-oil-recovery-literature-survey (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Gou, Y.; Hou, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Were, P. Acta Geotechnica 2014, 9, 49–58.

- CCSI. Projects Database: CO₂ Utilisation, Global CCS Institute. Available online: https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/projects/ co2-utilisation-projects (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- GCCSI. Saga City Waste Incineration Plant, Global CCS Institute, 2016. Available online: http://www.globalccsinstitute.com/sites/www.globalccsinstitute.com/files/content/page/122975/files/Saga%20City%20Waste%20Incineration%20Plant_0.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Sackler Forum. Dealing with Carbon Dioxide at Scale; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, p. 5.

- Chen, Z. A Review of Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture Technology. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Social Sciences and Economic Development (ICSSED 2022), 22–24 April 2022; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 524–528.

- Pardemann, R.; Meyer, B. Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture. In Handbook of Clean Energy Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–28.

- Olabi, A.G.; Obaideen, K.; Elsaid, K.; et al. Assessment of the Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture Contribution into Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Using Novel Indicators. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111710. [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, T. A Comparative Review of Next-Generation Carbon Capture Technologies for Coal-Fired Power Plant. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 2658–2670.

- Krishnan, A.; Nighojkar, A.; Kandasubramanian, B. Emerging Towards Zero Carbon Footprint via Carbon Dioxide Capturing and Sequestration. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 9, 100137. [CrossRef]

- Allangawi, A.; Alzaimoor, E.F.; Shanaah, H.H.; Mohammed, H.A.; Saqer, H.; El-Fattah, A.A.; Kamel, A.H. Carbon Capture Materials in Post-Combustion: Adsorption and Absorption-Based Processes. C 2023, 9, 17.

- Liu, J.; Baeyens, J.; Deng, Y.; Tan, T.; Zhang, H. The Chemical CO₂ Capture by Carbonation–Decarbonation Cycles. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110054. [CrossRef]

- Ghiat, I.; Al-Ansari, T. A Review of Carbon Capture and Utilisation as a CO₂ Abatement Opportunity within the EWF Nexus. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021. [Details needed for volume/pages if available].

- Gautam, A.; Mondal, M.K. Review of Recent Trends and Various Techniques for CO₂ Capture: Special Emphasis on Biphasic Amine Solvents. Fuel 2023, 334, 126616. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Okolie, J.A.; Abdelrasoul, A.; Niu, C.; Dalai, A.K. Review of Post-Combustion Carbon Dioxide Capture Technologies Using Activated Carbon. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 83, 46–63.

- Dixit, F.; Zimmermann, K.; Alamoudi, M.; Abkar, L.; Barbeau, B.; Mohseni, M.; Kandasubramanian, B.; Smith, K. Application of MXenes for Air Purification, Gas Separation and Storage: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 164, 112527. [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.; Deng, Y.; Dewil, R.; Baeyens, J.; Fan, X. Post-Combustion Carbon Capture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110490.

- Krishnan, A.; Nighojkar, A.; Kandasubramanian, B. Emerging Towards Zero Carbon Footprint via Carbon Dioxide Capturing and Sequestration. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 9, 100137.

- Farooqui, A.E.; Badr, H.M.; Habib, M.A.; Ben-Mansour, R. Numerical Investigation of Combustion Characteristics in an Oxygen Transport Reactor. Int. J. Energy Res. 2014, 38, 638–651.

- Zheng, C.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Luo, C.; Zhao, Y. Fundamental and Technical Challenges for a Compatible Design Scheme of Oxyfuel Combustion Technology. Engineering 2015, 1, 139–149.

- Shaula, A.L.; Pivak, Y.V.; Waerenborgh, J.C.; Gaczyñski, P.; Yaremchenko, A.A.; Kharton, V.V. Ionic Conductivity of Brownmillerite-Type Calcium Ferrite under Oxidizing Conditions. Solid State Ionics 2006, 177, 2923–2930.

- Chung, S.J.; Park, J.H.; Li, D.; Ida, J.I.; Kumakiri, I.; Lin, J.Y. Dual-phase metal−carbonate membrane for high-temperature carbon dioxide separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 7999–8006.

- Ben-Mansour, R.; Habib, M.A.; Badr, H.M.; Azharuddin; Nemitallah, M. Characteristics of oxy-fuel combustion in an oxygen transport reactor. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 4599–4606. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.M.; Long, H.A., III. Integration of carbon capture in IGCC systems. In Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) Technologies; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 445–463.

- Li, X.; Peng, Z.; Ajmal, T.; Aitouche, A.; Mobasheri, R.; Pei, Y.; Gao, B.; Wellers, M. A feasibility study of implementation of oxy-fuel combustion on a practical diesel engine at the economical oxygen-fuel ratios by computer simulation. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020, 12, 1687814020980182.

- Senior, C.L.; Morris, W.; Lewandowski, T.A. Emissions and risks associated with oxyfuel combustion: State of the science and critical data gaps. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2013, 63, 832–843. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Bi, X. Energy and Economic Assessment of Oxy-Fuel Combustion CO₂ Capture in Coal-Fired Power Plants. Energies 2024, 17, 4626.

- Climeworks. Supercharging Carbon Removal: A Focus on Direct Air Capture Technology (Industry Snapshot). July 2023. Available online https://climeworks.com/uploads/documents/climeworks-industry-snapshot-3.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2019; IEA: Paris, France, 2019. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2019 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Shyam, A.; Ahmed, K.R.A.; Kumar, J.P.N.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. Path of carbon dioxide capture technologies: An overview. Next Sustain. 2025, 6, 100118.

- Li, G.; Yao, J. Direct air capture (DAC) for achieving net-zero CO₂ emissions: advances, applications, and challenges. Eng 2024, 5, 1298–1336.

- Simari, C. Nanomaterials for Direct Air Capture of CO₂: Current State of the Art, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2025, 30, 3048.

- Realmonte, G.; Drouet, L.; Gambhir, A.; Glynn, J.; Hawkes, A.; Köberle, A.C.; Tavoni, M. An inter-model assessment of the role of direct air capture in deep mitigation pathways. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3277.

- Keith, D.W.; Holmes, G.; Angelo, D.S.; Heidel, K. A process for capturing CO₂ from the atmosphere. Joule 2018, 2, 1573–1594.

- Fuss, S.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; de Oliveira Garcia, W.; Hartmann, J.; Khanna, T.; Luderer, G. Negative emissions—Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063002.

- Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; Brown, S.; Fennell, P.S.; Fuss, S.; Galindo, A.; Hackett, L.A.; Hallett, J.P. Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176.

- Raganati, F.; Ammendola, P. CO₂ post-combustion capture: a critical review of current technologies and future directions. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 13858–13905. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Bi, X. Energy and Economic Assessment of Oxy-Fuel Combustion CO₂ Capture in Coal-Fired Power Plants. Energies 2024, 17, 4626.

- Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Murdock, C.R.; Didas, S.A.; Jones, C.W. Direct capture of CO₂ from ambient air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876.

- Climeworks. Mammoth: Our Newest Facility. Available online: https://climeworks.com/plant-mammoth (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Climeworks. Orca: The first large-scale plant. Available online: https://climeworks.com/plant-orca (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Kitamura, H.; Iwasa, K.; Fujita, K.; Muraoka, D. CO₂ Capture Project Integrated with Mikawa Biomass Power Plant. In Proceedings of the 16th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-16), October 2022; pp. 23–24. Available online: https://www.toshiba.com/taes/cms_files/Carbon_Capture_Mikawa_CaseStudy.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Ziemkiewicz, P.; Stauffer, P.H.; Sullivan-Graham, J.; Chu, S.P.; Bourcier, W.L.; Buscheck, T.A.; Carr, T.; Donovan, J.; Jiao, Z.; Lin, L.; Song, L. Opportunities for increasing CO₂ storage in deep, saline formations by active reservoir management and treatment of extracted formation water: Case study at the GreenGen IGCC facility, Tianjin, PR China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 54, 538–556.

- Spero, C.; Yamada, T. Callide Oxyfuel Project Final Results; Fortitude Valley, Queensland, 2018.

- Schmelz, W.J.; Hochman, G.; Miller, K.G. Total cost of carbon capture and storage implemented at a regional scale: Northeastern and midwestern United States. Interface Focus 2020, 10, 20190065. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture Research. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/fecm/pre-combustion-carbon-capture-research (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Current Cost of CO₂ Capture for Carbon Removal Technologies by Sector (Chart). Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/current-cost-of-co2-capture-for-carbon-removal-technologies-by-sector (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Bi, X. Energy and economic assessment of oxy-fuel combustion CO₂ capture in coal-fired power plants. Energies 2024, 17, 4626. [CrossRef]

- IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme (IEAGHG). 2021 Annual Review; IEAGHG: Cheltenham, UK, 2021.

- Peters, G.; Sognnæs, I. The Role of Carbon Capture and Storage in the Mitigation of Climate Change; CICERO Report, 2019.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Global CCS Institute. Global Status of CCS. Special Report: Introduction to Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage; Global CCS Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2016.

- ClimateSeed. What Is Carbon Capture? Available online: https://climateseed.com/blog/what-is-carbon-capture (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- World Economic Forum. What Is Carbon Capture and Storage—And How Can It Help Tackle the Climate Crisis? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/10/carbon-capture-storage-climate-crisis/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- International Energy Agency; United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Technology Roadmap: Carbon Capture and Storage in Industrial Applications. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/roadmap-carbon-capture-and-storage-in-industrial-applications (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Carpenter, A. CO₂ Abatement in the Iron and Steel Industry; Report CCC/193; IEA Clean Coal Centre: London, UK, 2012.

- Birat, J.P. Steel Sectoral Report: Contribution to the UNIDO Roadmap on CCS (Fifth Draft); Prepared for the UNIDO Global Technology Roadmap for CCS in Industry – Sectoral Experts Meeting: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24 September 2010.

- Kuramochi, T.; Ramírez, A.; Turkenburg, W.; Faaij, A. Techno-economic assessment and comparison of CO₂ capture technologies for industrial processes: Preliminary results for the iron and steel sector. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1981–1988. [CrossRef]

- Posco; Primetals Technologies. The Finex Process: Economic and Environmentally Safe Ironmaking. Available online: https://www.primetals.com/fileadmin/user_upload/content/01_portfolio/1_ironmaking/finex/THE_FINEX_R__PROCESS.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Van der Stel, J.; Meijer, K.; Teerhuis, C.; Zeijlstra, C.; Keilman, G.; Ouwehand, M. Update to the Developments of HIsarna: An ULCOS Alternative Ironmaking Process. In Proceedings of the IEAGHG/IETS Iron and Steel Industry CCUS and Process Integration Workshop, IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme, 2013.

- GlobalCement.com. Cement 101—An Introduction to the World’s Most Important Building Material. Available online: https://www.globalcement.com (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Dean, C.C.; Blamey, J.; Florin, N.H.; Al-Jeboori, M.J.; Fennell, P.S. The calcium looping cycle for CO₂ capture from power generation, cement manufacture and hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 836–855.

- Hills, T.; Leeson, D.; Florin, N.; Fennell, P. Carbon capture in the cement industry: Technologies, progress, and retrofitting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 368–377. [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, S.; Ruys, J. CO₂ Abatement: Exploring Options for Oil and Natural Gas Companies. McKinsey & Company, 2010.

- Andersson, V.; Franck, P.Ÿ.; Berntsson, T. Techno-economic analysis of excess heat driven post-combustion CCS at an oil refinery. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 45, 130–138. [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A.I.; Espatolero, S.; Romeo, L.M. Oxy-combustion power plant integration in an oil refinery to reduce CO₂ emissions. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 45, 118–129.

- Shah, M.T.; Utikar, R.P.; Pareek, V.K.; Evans, G.M.; Joshi, J.B. Computational fluid dynamic modelling of FCC riser: A review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 111, 403–448. [CrossRef]

- London School of Economics and Political Science. What Is Carbon Capture, Usage and Storage (CCUS) and What Role Can It Play in Tackling Climate Change? Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-carbon-capture-and-storage-and-what-role-can-it-play-in-tackling-climate-change/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- World Economic Forum. What’s Needed for Carbon Capture and Storage (CCUS) to Take Off. March 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/03/carbon-capture-storage-essentials-uptake/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

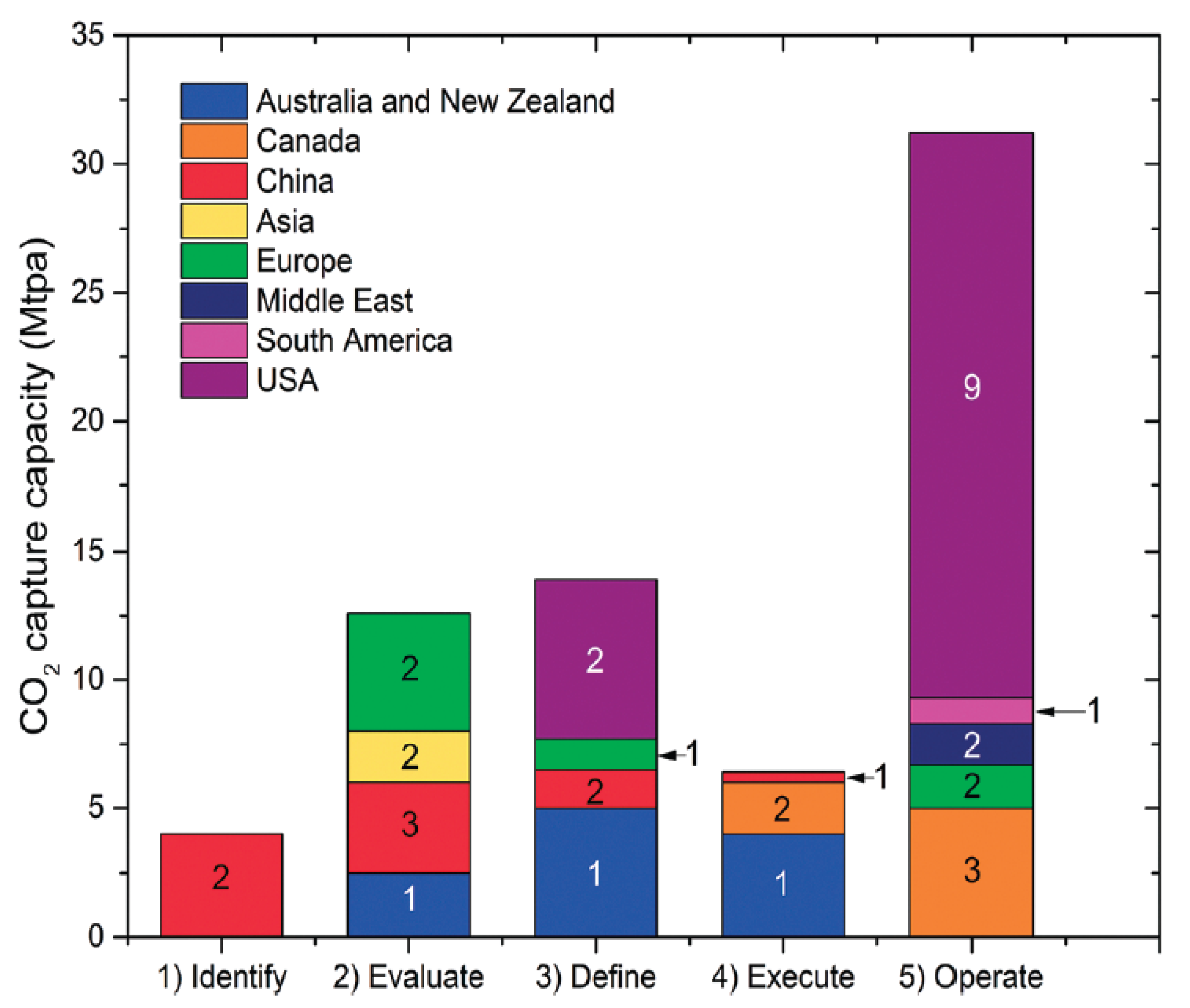

- Energy Central. Global Status of CCS 2024: Carbon Capture and Storage on the Rise. 21 October 2024. Available online: https://www.energycentral.com/energy-biz/post/global-status-ccs-2024-carbon-capture-and-storage-rise-uDYDYQajjV5JkTT (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Shi, S.; Hu, Y.H. 2024, A Landmark Year for Climate Change and Global Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage: Annual Progress Review. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025.

- ScienceDaily. Major Boost in Carbon Capture and Storage Essential to Reach 2 °C Climate Target. Available online https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/09/240925123600.htm (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Abanades, J.C.; Rubin, E.S.; Mazzotti, M.; Herzog, H.J. On the climate change mitigation potential of CO₂ conversion to fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2491–2499.

- Al-Mamoori, A.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Rezaei, F. Carbon capture and utilization update. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 834–849.

- Artz, J.; Müller, T.E.; Thenert, K.; Kleinekorte, J.; Meys, R.; Sternberg, A.; Bardow, A.; Leitner, W. Sustainable conversion of carbon dioxide: An integrated review of catalysis and life cycle assessment. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 434–504.

- Mac Dowell, N.; Fennell, P.S.; Shah, N.; Maitland, G.C. The role of CO₂ capture and utilization in mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 243–249.

- Randolph, J.B.; Saar, M.O. Combining geothermal energy capture with geologic carbon dioxide sequestration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Loschetter, A.; Kervévan, C.; Stead, R.; Le Guénan, T.; Dezayes, C.; Clarke, N. Integrating geothermal energy and carbon capture and storage technologies: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 210, 115179.

- Cong, L.; Lu, S.; Jiang, P.; Zheng, T.; Yu, Z.; Lü, X. Research progress on CO₂ as geothermal working fluid: A review. Energies 2024, 17, 5415.

- IEA Bioenergy. Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach to Estimate the Net Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Bioenergy. 2013. Available online: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Using-a-LCA-approach-to-estimate-the-net-GHG-emissions-of-bioenergy.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- International Energy Agency. ETP Clean Energy Technology Guide. 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/articles/etp-clean-energy-technology-guide (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- International Energy Agency. CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions; IEA: Paris, France, 2020.

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Hydrogen. 2019. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-hydrogen (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Global CCS Institute. Large-Scale CCS Projects. Available online: https://co2re.co/FacilityData (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Global CCS Institute. Strategic Analysis of the Global Status of Carbon Capture and Storage: Report 1—Status of Carbon Capture and Storage Projects Globally; Global CCS Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2009.

- Solartron ISA. Challenges of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). Available online: https://www.solartronisa.com/industries/clean-energy/carbon-capture/challenges-of-ccs (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Castro-Pardo, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Yadav, R.M.; de Carvalho Teixeira, A.P.; Mata, M.A.C.; Prasankumar, T.; Kabbani, M.A.; Kibria, M.G.; Xu, T.; Roy, S.; Ajayan, P.M. A comprehensive overview of carbon dioxide capture: From materials, methods to industrial status. Mater. Today 2022, 60, 227–270. [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, A.; Hingar, D.; Ostwal, S.; Thakkar, I.; Jadeja, S.; Shah, M. The current scope and stand of carbon capture storage and utilization—A comprehensive review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100368.

- Gür, T.M. Carbon dioxide emissions, capture, storage and utilization: Review of materials, processes and technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100965. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Energy System: Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage (accessed on 7 August).

| Carbon Capture Technology | Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Combustion Capture | Broad applicability without major restrictions | Offers versatile deployment; capable of capturing CO₂ at low concentrations; can be integrated with renewable energy systems | Involves substantial capital expenditure and operational costs; technological challenges persist | Moderate Technically achievable but constrained by infrastructure and financial barriers |

| Post-Combustion Capture | Primarily used in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) power plants | Established and mature technology; delivers high capture efficiency with straightforward separation processes | Applicability is limited to specific settings | High Most practical for retrofitting existing facilities with relatively lower initial costs |

| Oxy-Fuel Combustion | Suitable for pulverized coal power plants, natural gas combined cycle plants, and other fossil fuel power generation | Proven technology with broad applicability; suitable for retrofitting existing plants | Suffering from decreased thermal efficiency during operation | Moderate Technically reliable but challenged by energy penalties and efficiency reductions |

| Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Applicable to pulverized coal and IGCC power plants | Provides high purity and concentration of captured CO₂; relatively simple operational steps; can be used for retrofitting or repowering | Requires significant investment due to additional equipment and high energy consumption | Low to Moderate Holds promise for future application but currently limited by cost and energy intensity |

| Technology Type | Example Case Study | Scale / Features | Start-up Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Climeworks Mammoth (Iceland) | ≈36,000 t CO₂/year using geothermal energy and modular solid sorbent units | 2024 | [59] |

| Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Climeworks Orca (Iceland) | ≈4,000 t CO₂/year; first large-scale DAC plant with underground mineralization | 2021 | [60] |

| Post-Combustion Capture | Mikawa post combustion capture plant (Japan) | Power generation 180Kt CO₂/year | ~2020 | [61] |

| Pre-Combustion | GreenGen IGCC Project, Tianjin, China | Designed to capture up to 1 Mt CO₂/year in full-scale implementation | ~2014 | [62] |

| Oxy-Fuel Combustion | Callide Oxy-Fuel Project (Australia) | Demo project captured ~27,300 t CO₂/year with ~80% CO₂ concentration flue gas | ~2020 | [63] |

| Technology | Estimated Cost (USD/ton CO₂) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Air Capture (DAC) | $100–$1000/t CO₂ (may exceed $1,000/t in pilots) | [52] |

| Post-combustion Capture | $47–$76 /t CO₂ | [64] |

| Pre-combustion Capture | $60–$150 /t CO₂ | [65,66] |

| Oxy-fuel Combustion | $70–$160 /t CO₂ | [67,68] |

| Facility | Country | Sector | CO₂ Application | Commissioning Year | CO₂ Capture Capacity (kt/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stockholm Exergi AB | Sweden | Combined heat and power | Not specified | 2019 | Pilot scale |

| Arkalon CO₂ Compression Facility | USA | Ethanol production | Storage (Enhanced Oil Recovery, EOR) | 2009 | 290 |

| OCAP | Netherlands | Ethanol production | Utilization | 2011 | Less than 400 |

| Bonanza Bioenergy CCUS EOR | USA | Ethanol production | Storage (EOR) | 2012 | 100 |

| Husky Energy CO₂ Injection | Canada | Ethanol production | Storage (EOR) | 2012 | 90 |

| Calgren Renewable Fuels CO₂ Plant | USA | Ethanol production | Utilization | 2015 | 150 |

| Lantmännen Agroetanol | Sweden | Ethanol production | Utilization | 2015 | 200 |

| Alco BioFuel Bio-refinery CO₂ Plant | Belgium | Ethanol production | Utilization | 2016 | 100 |

| Cargill Wheat Processing CO₂ Plant | UK | Ethanol production | Utilization | 2012 | 600 |

| Illinois Industrial CCS | USA | Ethanol production | Dedicated geological storage | 2017 | 1000 |

| Drax BECCS Plant | UK | Power generation | Not specified | 2020 | Pilot scale |

| Mikawa Post Combustion Capture | Japan | Power generation | Not specified | 2020 | 180 |

| Saga City Waste Incineration Plant | Japan | Waste-to-energy | Utilization | 2016 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).