Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

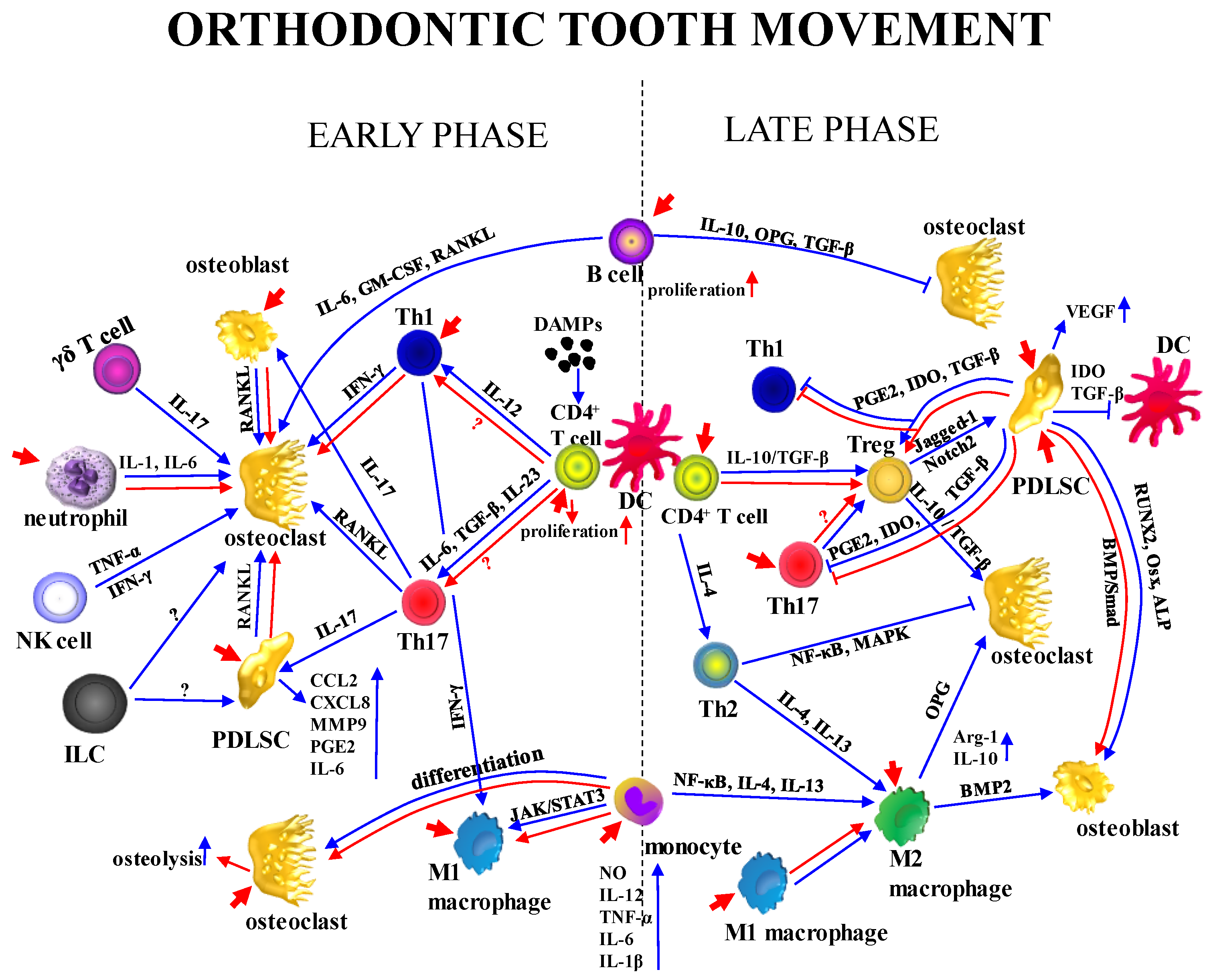

2. Key Cellular Players in OTM

2.1. Osteoblasts

2.2. Osteoclasts

2.3. Periodontal Ligament

2.4. Immune Cells

3. Biological and Molecular Basis of Orthodontic Tooth Movement

4. Photobiomodulation in Dentistry: Principles and Broader Clinical Utility

5. Summary of Recent Systematic Reviews on the Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Orthodontics

6. Molecular Aspects of Low-Level Laser Therapy and the Integration of Mechanical and Photon-Induced Signals during Orthodontic Tooth Movement

7. Cross-talk Between Osteoblasts, Osteoclasts, and Periodontal Stromal Cells During Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Influence of Low-Level Laser Therapy

8. Matrix Remodeling and Vascular Response in Orthodontic Tooth Movement Under the Influence of Low-Level Laser Therapy

9. Apoptosis and Autophagy in Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Mechanosensitive Responses and Cellular Interplay under Low-Level Laser Therapy

10. Immune Dynamics in Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Unresolved Mechanisms of Low-Level Laser Therapy

10.1. Innate Immunity

10.2. Adaptive Immunity

11. Conclusions

12. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krishnan, V.; Davidovitch, Z. Cellular, molecular, and tissue-level reactions to orthodontic force. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2006, 129, 469.e1–469.e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meikle, M.C. The tissue, cellular, and molecular regulation of orthodontic tooth movement: 100 years after Carl Sandstedt. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Maltha, J.C.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. Optimum force magnitude for orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic literature review. Angle Orthod. 2003, 73, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- d’Apuzzo, F.; Cappabianca, S.; Ciavarella, D.; Monsurrò, A.; Silvestrini-Biavati, A.; Perillo, L.; Perillo, L. Biomarkers of periodontal tissue remodeling during orthodontic tooth movement in mice and men: Overview and clinical relevance. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naoum, F.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Al-Jundi, A. Does alveolar corticotomy accelerate orthodontic tooth movement when retracting upper canines? A split-mouth design randomized controlled trial. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.J.; Yoon, H.J.; Lee, P.J.; Moon, W.; Park, Y.G. Effect of piezopuncture on tooth movement and bone remodeling in dogs. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 144, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadra, M.; Lyngstadaas, S.P.; Haanaes, H.R.; Mustafa, K. Effect of laser therapy on attachment, proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblast-like cells cultured on titanium implant material. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3503–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.M.; Aljibrin, F.J.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Saklou, R.; Alhassan, I.A.; Alamer, A.H.; Al Ameer, M.H.; Hatami, M.S.; Dahhas, F.Y. Photobiomodulation in Orthodontics: Mechanisms and Clinical Efficacy for Faster Tooth Movement. Cureus 2024, 16, e59061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, P.; Cao, X.; Frenette, P.S.; Mao, J.J.; Robey, P.G.; Simmons, P.J.; Wang, C.Y. The meaning, the sense and the significance: Translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhao, M.; Mundy, G.R. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 2004, 22, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Kneissel, M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: From human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, T. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by Runx2. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 658, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canalis, E. Growth factor control of bone mass. J. Cell Biochem. 2009, 108, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, S.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simões, M.J.; Cerri, P.S. Biology of bone tissue: Structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 421746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, E.E. Role of matrix vesicles in biomineralization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1790, 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, L.C.; Heufelder, A.E. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin in bone cell biology. J. Mol. Med. 2001, 79, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, S.L.; Bonewald, L.F. Dynamics of the transition from osteoblast to osteocyte. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1192, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, S.L. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 2000, 289, 1504–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, W.J.; Simonet, W.S.; Lacey, D.L. Osteoclast Differentiation and Activation. Nature 2003, 423, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurukai, T.; Udagawa, N.; Matsuzaki, K.; Takahashi, N.; Suda, T. Roles of Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor and Osteoclast Differentiation Factor in Osteoclastogenesis. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2000, 18, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayanagi, H. Osteoimmunology: Shared Mechanisms and Crosstalk between the Immune and Bone Systems. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi, H.; Kim, S.; Koga, T.; Nishina, H.; Isshiki, M.; Yoshida, H.; Saiura, A.; Isobe, M.; Yokochi, T.; Inoue, J.; Wagner, E.F.; Mak, T.W.; Kodama, T.; Taniguchi, T. Induction and Activation of the Transcription Factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) Integrate RANKL Signaling in Terminal Differentiation of Osteoclasts. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, N.K.; Lee, S.Y. Current Understanding of RANK Signaling in Osteoclast Differentiation and Maturation. Mol. Cells 2017, 40, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Teitelbaum, S.L. Osteoclasts: New Insights. Bone Res. 2013, 1, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.T.; Clarke, B.L.; Khosla, S. Bisphosphonates: Mechanism of Action and Role in Clinical Practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lin, C.; Stavre, Z.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Shim, J.H. Osteoblast–Osteoclast Communication and Bone Homeostasis. Cells 2020, 9, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Pei, F.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, Z. Exploring the Mechanical and Biological Interplay in the Periodontal Ligament. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, H. Comparative Proteomics Analysis of Human Stem Cells from Dental Gingival and Periodontal Ligament. Proteomics 2022, 22, e2200027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, M.; Niederau, C.; Florea, A.; Kiessling, F.; Morgenroth, A.; Mottaghy, F.M.; Schneider, R.K.; Wolf, M.; Craveiro, R.B. Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone Remodeling during Long Orthodontic Tooth Movement Analyzed by a Novel User-Independent 3D-Methodology. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danz, J.C.; Degen, M. Selective Modulation of the Bone Remodeling Regulatory System through Orthodontic Tooth Movement—A Review. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1472711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaushu, S.; Klein, Y.; Mandelboim, O.; Barenholz, Y.; Fleissig, O. Immune Changes Induced by Orthodontic Forces: A Critical Review. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Guo, W.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Kim, S.G.; Embree, M.C.; Song, K.S.; Marao, H.F.; Mao, J.J. Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone in Health and Adaptation: Tooth Movement. Front. Oral Biol. 2016, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Y.; David, E.; Pinto, N.; Khoury, Y.; Barenholz, Y.; Chaushu, S. Breaking a Dogma: Orthodontic Tooth Movement Alters Systemic Immunity. Prog. Orthod. 2024, 25, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneman, S.; Von den Hoff, J.W.; Maltha, J.C. Mechanobiology of Tooth Movement. Eur. J. Orthod. 2008, 30, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robling, A.G.; Turner, C.H. Mechanical Signaling for Bone Modeling and Remodeling. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2009, 19, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, L.; Nookaew, I.; Mannen, E.; Silva, M.J.; Almeida, M.; Xiong, J. Stimulation of Piezo1 by Mechanical Signals Promotes Bone Anabolism. Elife 2019, 8, e49631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, W.H. Mechanotransduction and Focal Adhesions. Cell Biol. Int. 2012, 36, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Praneetpong, N.; Ono, W.; Ono, N. Mechanisms of Osteoclastogenesis in Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Orthodontically Induced Tooth Root Resorption. J. Bone Metab. 2023, 30, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubuzima, P.; Nshimiyimana, E.; Mukeshimana, C.; Mazimpaka, P.; Mugabo, E.; Mbyayingabo, D.; Mohamed, A.S.; Habumugisha, J. Exploring Biological Mechanisms in Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Bridging the Gap between Basic Research Experiments and Clinical Applications – A Comprehensive Review. Ann. Anat. 2024, 255, 152286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowska, B.; Kosson, D.; Domaracka, K. Lights and Shadows of NSAIDs in Bone Healing: The Role of Prostaglandins in Bone Metabolism. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018, 12, 1753–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wu, P.; Yu, F.; Luo, G.; Qing, L.; Tang, J. HIF-1α Regulates Bone Homeostasis and Angiogenesis, Participating in the Occurrence of Bone Metabolic Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques-Carvalho, A.; Kim, H.N.; Almeida, M. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Bone Cell Physiology and Pathophysiology. Bone Rep. 2023, 19, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behm, C.; Nemec, M.; Blufstein, A.; Schubert, M.; Rausch-Fan, X.; Andrukhov, O.; Jonke, E. Interleukin-1β Induced Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression in Human Periodontal Ligament-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells under In Vitro Simulated Static Orthodontic Forces. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobeiha, M.; Moghadasian, M.H.; Amin, N.; Jafarnejad, S. RANKL/RANK/OPG Pathway: A Mechanism Involved in Exercise-Induced Bone Remodeling. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6910312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chen, W.; Qian, A.; Li, Y.P. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Components and Mechanisms in Bone Formation, Homeostasis, and Disease. Bone Res. 2024, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Peng, Y.; Liu, N.; Liu, Q. The Relationship between MAPK Signaling Pathways and Osteogenic Differentiation of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells: A Literature Review. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maycas, M.; Esbrit, P.; Gortázar, A.R. Molecular Mechanisms in Bone Mechanotransduction. Histol. Histopathol. 2017, 32, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yang, N.; Sun, M.; Yang, S.; Chen, X. The Role of Calcium Channels in Osteoporosis and Their Therapeutic Potential. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1450328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.E. Non-Smad Signaling Pathways of the TGF-β Family. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a022129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschneck, C.; Thuy, M.; Leikam, A.; Memmert, S.; Deschner, J.; Damanaki, A.; Spanier, G.; Proff, P.; Jantsch, J.; Schröder, A. Role and Regulation of Mechanotransductive HIF-1α Stabilisation in Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Chen, L. Application of Antioxidant Compounds in Bone Defect Repair. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, V.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation: Lasers vs. Light Emitting Diodes? Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Patano, A.; Palumbo, I.; Guglielmo, M.; Trilli, I.; Netti, A.; Ferrara, I.; Viapiano, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Favia, G.; Dongiovanni, L.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Limongelli, L. Photobiomodulation and Growth Factors in Dentistry: A Systematic Review. Photonics 2023, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.J.; Esper, L.A.; Sbrana, M.C.; de Oliveira, P.G.; do Valle, A.L.; de Almeida, A.L. Effect of Low-Level Laser on Bone Defects Treated with Bovine or Autogenous Bone Grafts: In Vivo Study in Rat Calvaria. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 104230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronshaw, M.; Parker, S.; Anagnostaki, E.; Mylona, V.; Lynch, E.; Grootveld, M. Photobiomodulation and Oral Mucositis: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.A.; Hasan, S.; Saeed, S.; Khan, A.; Khan, M. Low-Level Laser Therapy in Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervisbegovic, S.; Lettner, S.; Tur, D.; Laky, M.; Georgopoulos, A.; Moritz, A.; Sculean, A.; Rausch-Fan, X. Adjunctive Low-Level Laser Therapy in Periodontal Treatment—A Randomized Clinical Split-Mouth Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turhani, D.; Scheriau, M.; Kapral, D.; Benesch, T.; Jonke, E.; Bantleon, H.P. Pain Relief by Single Low-Level Laser Irradiation in Orthodontic Patients Undergoing Fixed Appliance Therapy. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2006, 130, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furquim, R.D.; Pascotto, R.C.; Rino Neto, J.; Cardoso, J.R.; Ramos, A.L. Low-Level Laser Therapy Effects on Pain Perception Related to the Use of Orthodontic Elastomeric Separators. Dental Press J. Orthod. 2015, 20, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.M.; Shehata, F.I.; Al Sawa, A.A.; Karam, S.S. Effect of Low Level Laser Therapy on Orthodontic Induced Inflammatory Root Resorption in Rats. Alexandria Dent. J. 2020, 45, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompe, C.; Moncrieff, L.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Bruska, M.; Dominiak, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Skiba, T.H.I.; Shibli, J.A.; Angelova Volponi, A.; Kempisty, B.; Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska, M. Photobiomodulation—Underlying Mechanism and Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid, K.A.; Eid, A.A.; Kaddah, M.A.; Elsharaby, F.A. The Effect of Combined Corticotomy and Low Level Laser Therapy on the Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Split Mouth Randomized Clinical Trial. Laser Ther. 2019, 28, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.C.F.; Maia, T.A.C.; de Barros Silva, P.G.; Abreu, L.G.; Gondim, D.V.; Santos, P.C.F. Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy on the Orthodontic Mini-Implants Stability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; McGrath, C.; Jin, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y. The Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy as an Adjunct to Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi-Mehta, G.; Bhad-Patil, W.A. Efficacy of Low-Intensity Laser Therapy in Reducing Treatment Time and Orthodontic Pain: A Clinical Investigation. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2012, 141, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgadi, R.; Sedky, Y.; Franzen, R. The Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review. Lasers Dent. Sci. 2023, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.H.; Du, Y.Q.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Hou, F.C.; Niu, S.Q.; Zang, Y.J.; Li, B. Effect of low-level laser therapy on orthodontic dental alignment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakdach, W.M.M.; Hadad, R. Effectiveness of low-level laser therapy in accelerating the orthodontic tooth movement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent. Med. Probl. 2020, 57, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, M.; Briguglio, F.; Grassia, V.; Picciolo, G.; Fiorillo, L.; Matarese, G. Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy during Tooth Movement: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Materials 2019, 12, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavagal, C.M.; Matondkar, S.P.; Yavagal, P.C. Efficacy of Laser Photobiomodulation in Accelerating Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Children: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 14 (Suppl 1), S94–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Latini, G.; Del Vecchio, G.; Trilli, I.; Ferrante, L.; Dipalma, G.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D. Low-Level Light Therapy in Orthodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Shao, S.; Shen, H.; Zhu, L.; Ye, P.; Svensson, P.; Wang, K. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Tooth-Related Pain and Somatosensory Function Evoked by Orthodontic Treatment. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.H.; Nogueira, C.Q.; Cotrin, P.; Fialho, T.; Oliveira, R.C.; Oliveira, R.G.; Salmeron, S.; Valarelli, F.P.; Freitas, K.M.S.; Cançado, R.H. Efficacy of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Reducing Pain in the Initial Stages of Orthodontic Treatment. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 3934900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Angbawi, A.; McIntyre, G.; Fleming, P.S.; Bearn, D. Non-Surgical Adjunctive Interventions for Accelerating Tooth Movement in Patients Undergoing Orthodontic Treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 6, CD010887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zeng, X.T.; Guo, Y. Low-Level Laser Therapy for Orthodontic Pain: A Systematic Review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelogiannakis, D.; Al-Shammery, D.; Akram, Z.; Rossouw, P.E.; Javed, F.; Romanos, G.E. Influence of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Orthodontically-Induced Inflammatory Root Resorption: A Systematic Review. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 100, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Peng, J.; Song, W.; Zhao, J.; Chen, L. The Effects and Mechanisms of PBM Therapy in Accelerating Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masha, R.T.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Low-Intensity Laser Irradiation at 660 nm Stimulates Transcription of Genes Involved in the Electron Transport Chain. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2013, 31, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires Oliveira, D.A.; de Oliveira, R.F.; Zangaro, R.A.; Soares, C.P. Evaluation of Low-Level Laser Therapy of Osteoblastic Cells. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2008, 26, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.; Lozano, P.; Ros, G.; Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and Oxidative Stress: An Integral, Updated and Critical Overview of Their Metabolic Interconnections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, P.; Forte, E.; Mastronicola, D.; Giuffrè, A.; Arese, M. Cytochrome c Oxidase and Nitric Oxide in Action: Molecular Mechanisms and Pathophysiological Implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1817, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Huang, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Zou, Z.; Li, L.; Ji, K.; Nie, Z.; Yang, B.; Wei, Z.; Xu, P.; Jia, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, K.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M.; Ye, S.; Liu, Q. The Role of S-Nitrosylation of PFKM in Regulation of Glycolysis in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, L.F.; Hamblin, M.R. Proposed Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2016, 22, 7000417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karu, T.I. Mitochondrial Signaling in Mammalian Cells Activated by Red and Near-IR Radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellini, F.; Sassoli, C.; Nosi, D.; Deledda, C.; Tonelli, P.; Zecchi-Orlandini, S.; Formigli, L.; Giannelli, M. Low Pulse Energy Nd:YAG Laser Irradiation Exerts a Biostimulative Effect on Different Cells of the Oral Microenvironment: An In Vitro Study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2010, 42, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, A.; Chellini, F.; Giannelli, M.; Nosi, D.; Zecchi-Orlandini, S.; Sassoli, C. Red (635 nm), Near-Infrared (808 nm) and Violet-Blue (405 nm) Photobiomodulation Potentiality on Human Osteoblasts and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Morphological and Molecular In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís-López, A.; Kriebs, U.; Marx, A.; Mannebach, S.; Liedtke, W.B.; Caterina, M.J.; Freichel, M.; Tsvilovskyy, V.V. Analysis of TRPV Channel Activation by Stimulation of FCεRI and MRGPR Receptors in Mouse Peritoneal Mast Cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehpour, F.; Khademi, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation Therapy for Dementia: A Systematic Review of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Studies. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 1431–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianferotti, L.; Gomes, A.R.; Fabbri, S.; Tanini, A.; Brandi, M.L. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Bone Metabolism: From Bench to Bedside and Back. Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 2055–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arany, P.R.; Cho, A.; Hunt, T.D.; Sidhu, G.; Shin, K.; Hahm, E.; Huang, G.X.; Weaver, J.; Chen, A.C.; Padwa, B.L.; Hamblin, M.R.; Barcellos-Hoff, M.H.; Kulkarni, A.B.; Mooney, D.J. Photoactivation of Endogenous Latent Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Directs Dental Stem Cell Differentiation for Regeneration. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 238ra69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlach, A.; Bertram, K.; Hudecova, S.; Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A Mutual Interplay. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiry, M.A. Biological Aspects of Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Review of Literature. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.H.; Teixeira, H.; Tsai, A. Mechanistic Insight into Orthodontic Tooth Movement Based on Animal Studies: A Critical Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ding, L.; Ding, Z.; Fu, Y.; Song, Y.; Jing, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ni, Y.; Hu, Q. Tensile Force-Induced PDGF-BB/PDGFRβ Signals in Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts Activate JAK2/STAT3 for Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.P.; Poblano Pérez, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, S.; Liu, Y. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived from Dental Tissues: Immunomodulatory Actions in Periodontal Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Irie, N.; Takada, Y.; Shimoda, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Nishiwaki, T.; Suda, T.; Matsuo, K. Bidirectional EphrinB2-EphB4 Signaling Controls Bone Homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006, 4, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lontos, K.; Adamik, J.; Tsagianni, A.; Galson, D.L.; Chirgwin, J.M.; Suvannasankha, A. The Role of Semaphorin 4D in Bone Remodeling and Cancer Metastasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, H.; Norman, B.P.; Lai, K.; Cheng, W.; Afizan, N.M.; Mohamed Alitheen, N.B.; Osman, M.A. Post-Transcriptional Regulatory Crosstalk between MicroRNAs and Canonical TGF-β/BMP Signalling Cascades on Osteoblast Lineage: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaki, H.; Wada, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; et al. Compression and Tension Variably Alter Osteoprotegerin Expression via miR-3198 in Periodontal Ligament Cells. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Wei, Q.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hong, Z.; He, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, W. Inhibition of miR-93-5p Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation in a Rabbit Model of Trauma-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 2152–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, X.; Jie, Y. Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Human Periodontal Ligament Induce Osteoclast Differentiation by Transporting miR-28 to Osteoclast Precursor Cells and Further Promote Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhan, W.; Deng, M.; Wu, X.; Chen, Z.; Xie, J.; Ye, W.; Zhao, M.; Chu, J. miR-21-5p Enriched Exosomes from Human Embryonic Stem Cells Promote Osteogenesis via YAP1 Modulation. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 13095–13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Dong, C.; Yang, J.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, Q.; Liang, Y.; Bao, L.; Feng, G.; Ji, J.; Feng, X.; Gu, Z. Exosomal microRNA-155-5p from PDLSCs Regulated Th17/Treg Balance by Targeting Sirtuin-1 in Chronic Periodontitis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 20662–20674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Wu, F. Low-Level Laser Therapy Promotes Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation of PDLSCs via BMP/Smad Activation in a Dose-Dependent Manner. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3591–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, P.N.; Saranya, I.; Selvamurugan, N. Crosstalk between Wnt and Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling during Osteogenic Differentiation. World J. Stem Cells 2024, 16, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, L.; Parsamanesh, G.; Shahabi, S.; Jazaeri, M.; Baghaei, K.; Fekrazad, R. The Effect of Laser Photobiomodulation on Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylona, V.; Anagnostaki, E.; Chiniforush, N.; Barikani, H.; Lynch, E.; Grootveld, M. Photobiomodulation Effects on Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 19, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, M.; Brancato, A.M.; Torriani, C.; Bina, V.; Annunziata, S.; Cornella, E.; Trucchi, M.; Jannelli, E.; Mosconi, M.; Gastaldi, G.; Caliogna, L.; Grassi, F.A.; Pasta, G. The Role of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Bone Healing: Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Park, B.; Shin, S.; Kim, I. Low-Level Laser Irradiation Stimulates RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis via the MAPK Pathway in RAW 264.7 Cells. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Le, H.H.T.; Tsai, H.-C.; Tang, C.-H.; Yu, J.-H. The Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Osteoclast Differentiation: Clinical Implications for Tooth Movement and Bone Density. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassaei, S.; Fekrazad, R.; Shahraki, N. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Review Article. J. Dent. (Tehran) 2013, 10, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, D.; Guo, H. Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) Reduces IL-1β and TNF-α and Increases IL-1RA in Gingival and Bone Tissue, Enhancing Wound Healing in MRONJ Models. Bone Rep. 2023, 18, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jacox, L.A.; Little, S.H.; Ko, C.C. Orthodontic Tooth Movement: The Biology and Clinical Implications. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behm, C.; Nemec, M.; Weissinger, F.; Rausch, M.A.; Andrukhov, O.; Jonke, E. MMPs and TIMPs Expression Levels in the Periodontal Ligament during Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavish, L.; Perez, L.; Gertz, S.D. Low-Level Laser Irradiation Modulates Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity and Gene Expression in Porcine Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006, 38, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwack, C.; Kim, S.-S.; Park, S.B.; Park, M.-H. The Expression of MMP-1, -8, and -13 mRNA in the Periodontal Ligament of Rats during Tooth Movement with Cortical Punching. Korean J. Orthod. 2008, 38, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, L.; Khammissa, R.A.; Schechter, I.; Thomadakis, G.; Fourie, J.; Lemmer, J. Biological Events in Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone Associated with Application of Orthodontic Forces. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 876509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, K.; Wang, X.; Guo, Z.; Deng, Q.; Li, J.; Lv, S.; Yu, W. Effects of Low Level Laser on Periodontal Tissue Remodeling in hPDLCs under Tensile Stress. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, A.; Chiba, M.; Hayashi, H.; Igarashi, K. Compressive Force Induces VEGF Production in Periodontal Tissues. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gao, J.; Ding, P.; Gao, Y. The Role of Endothelial Cell–Pericyte Interactions in Vascularization and Diseases. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 67, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, F.A.; Farrar, R.; Farella, M. Investigating Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Challenges and Future Directions. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2020, 50, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, V.; Moretti, A.I.; Assis, L.; Bossini, P.; Crusca, J. de S.; Neto, C.B.; Fangel, R.; de Souza, H.P.; Hamblin, M.R.; Parizotto, N.A. Low Level Laser Therapy Increases Angiogenesis in a Model of Ischemic Skin Flap in Rats Mediated by VEGF, HIF-1α and MMP-2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2013, 125, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Li, L.; Kou, N.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, F. Low Level Laser Therapy Promotes Bone Regeneration by Coupling Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloemen, V.; Schoenmaker, T.; de Vries, T.J.; Everts, V. Direct Cell–Cell Contact between Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts and Osteoclast Precursors Synergistically Increases the Expression of Genes Related to Osteoclastogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 222, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein-Nulend, J.; van Oers, R.F.; Bakker, A.D.; Bacabac, R.G. Nitric Oxide Signaling in Mechanical Adaptation of Bone. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Shi, M.; Gan, P.; Huang, Q.; Wang, A.; Tan, G.; Fang, Y.; Liao, H. Low-Level Laser Therapy Induces Human Umbilical Vascular Endothelial Cell Proliferation, Migration and Tube Formation through Activating the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Microvasc. Res. 2020, 129, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyszyn, A.; Doroszko, A.; Szahidewicz-Krupska, E.; Rola, P.; Gutherc, R.; Jasiczek, J.; Mazur, G.; Derkacz, A. Effect of the Transdermal Low-Level Laser Therapy on Endothelial Function. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, G.; Niso-Santano, M.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Kroemer, G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, S.; Kalajzic, Z.; Utreja, A.; Nihara, J.; Wadhwa, S.; Uribe, F.; Nanda, R. Osteocyte death during orthodontic tooth movement in mice. Angle Orthod. 2014, 84, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, R.; Singh, N. Detection of apoptosis in human periodontal ligament during orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Spec. 2015, 3, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zhao, D.; Xu, C. Interaction between caspase-3 and caspase-5 in the stretch-induced programmed cell death in the human periodontal ligament cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 13571–13581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.W.; Yao, C.C.; Jeng, J.H.; Shieh, H.Y.; Chen, Y.J. Periostin inhibits mechanical stretch-induced apoptosis in osteoblast-like MG-63 cells. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018, 117, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Bao, M.; Yi, J.; Li, Y. Biomechanical and biological responses of periodontium in orthodontic tooth movement: up-date in a new decade. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Kalajzic, Z.; Choi, T.; Maleeh, I.; Ricupero, C.L.; Skelton, M.N.; Daily, M.L.; Chen, J.; Wadhwa, S. The role of inhibition of osteocyte apoptosis in mediating orthodontic tooth movement and periodontal remodeling: A pilot study. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Deng, J.; Li, W.; Han, B. Periodontal ligament cell apoptosis activates Lepr⁺ osteoprogenitors in orthodontics. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wu, W.; Ying, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, H. A regulatory role of Piezo1 in apoptosis of periodontal tissue and periodontal ligament fibroblasts during orthodontic tooth movement. Aust. Endod. J. 2023, 49 (Suppl. 1), 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, J.; Craveiro, R.B.; Azraq, I.; Niederau, C.; Schröder, S.K.; Weiskirchen, R.; Jankowski, J.; Wolf, M. In vitro compression model for orthodontic tooth movement modulates human periodontal ligament fibroblast proliferation, apoptosis and cell cycle. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansani, T.N.; Basso, F.G.; Turirioni, A.P.; Kurachi, C.; Hebling, J.; de Souza Costa, C.A. Effects of low-level laser therapy on the proliferation and apoptosis of gingival fibroblasts treated with zoledronic acid. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.H.; Chen, S.Y.; Hsieh, Y.L.; Teng, Y.H.; Cheng, Y.J. Low-level laser therapy prevents endothelial cells from TNF-α/cycloheximide-induced apoptosis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Oliveira, C.; de Oliveira, H.A.; Teixeira, I.L.A.; Antonio, E.L.; Silva, F.A.; Sunemi, S.; Leal-Junior, E.C.; de Tarso Camillo de Carvalho, P.; Tucci, P.J.F.; Serra, A.J. Low-level laser therapy prevents muscle apoptosis induced by a high-intensity resistance exercise in a dose-dependent manner. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 1867–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; Lin, F.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, X.; Mei, L. Dynamic study into autophagy and apoptosis during orthodontic tooth movement. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jacox, L.A.; Coats, S.; Kwon, J.; Xue, P.; Tang, N.; Rui, Z.; Wang, X.; Kim, Y.I.; Wu, T.J.; Lee, Y.T.; Wong, S.W.; Chien, C.H.; Cheng, C.W.; Gross, R.; Lin, F.C.; Tseng, H.; Martinez, J.; Ko, C.C. Roles of autophagy in orthodontic tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2021, 159, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, B.; Yang, K. Autophagy regulates osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells induced by orthodontic tension. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 2983862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, L.; He, H. Autophagy in orthodontic tooth movement: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, X.; Wei, X.; Ju, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Song, Z.; Luo, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z. Protective effect of photobiomodulation against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage by promoting autophagy through inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in MC3T3-E1 cells. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 7223353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, W.; Zhu, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, X. Photobiomodulation therapy at 650 nm enhances osteogenic differentiation of osteoporotic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through modulating autophagy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 50, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.N.M.D.; Fernandes, E.M.; Pereira, V.A.; Mizobuti, D.S.; Covatti, C.; Rocha, G.L.D.; Minatel, E. LEDT and idebenone treatment modulate autophagy and improve regenerative capacity in the dystrophic muscle through an AMPK-pathway. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.H.; Huang, X.; Rojas Cortez, L.; Sripinun, P.; Lee, J.M.; Hong, J.J.; Graves, D.T. Inflammation and mechanical force-induced bone remodeling. Periodontol. 2000 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Hassan, W.N.; Waddington, R.J. Immunology of tooth movement and root resorption in orthodontics. In Title of Book or Book Series; Publisher: Place, Year; pp. 134–155. [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G. New developments in neutrophil biology and periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2020, 82, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcaccini, A.M.; Amato, P.A.; Leão, F.V.; Gerlach, R.F.; Ferreira, J.T. Myeloperoxidase activity is increased in gingival crevicular fluid and whole saliva after fixed orthodontic appliance activation. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2010, 138, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, M.; Kou, X.; Yang, R.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Liu, F.; He, D.; Gan, Y.; Zhou, Y. Orthodontic force induces systemic inflammatory monocyte responses. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Kou, X.; Yang, R.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Luo, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, F.; Yan, Y.; Gan, Y.; Zhou, Y. M1-like macrophage polarization promotes orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Cai, X.; Ren, F.; Ye, Y.; Wang, F.; Zheng, C.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, M. The macrophage-osteoclast axis in osteoimmunity and osteo-related diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 664871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.D. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 32, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, S.; Sathe, A.A.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Yang, P.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Y. CCR2⁺ macrophages promote orthodontic tooth movement and alveolar bone remodeling. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 835986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, Y.; Fleissig, O.; Polak, D.; Barenholz, Y.; Mandelboim, O.; Chaushu, S. Immunorthodontics: in vivo gene expression of orthodontic tooth movement. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, A.; Kappler, P.; Nazet, U.; Jantsch, J.; Proff, P.; Cieplik, F.; Deschner, J.; Kirschneck, C. Effects of compressive and tensile strain on macrophages during simulated orthodontic tooth movement. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 2814015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Yang, H.; Shi, Q. Macrophages and bone inflammation. J. Orthop. Translat. 2017, 10, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Ren, L.; Wei, W.; Bai, D. Macrophages mediate corticotomy-accelerated orthodontic tooth movement. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandevska-Radunovic, V.; Kvinnsland, I.H.; Kvinnsland, S.; Jonsson, R. Immunocompetent cells in rat periodontal ligament and their recruitment incident to experimental orthodontic tooth movement. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1997, 105, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, S.; Leibowitz, A.; Aizenbud, Y.; Chaushu, S.; Reuven, Y.; Shapira, Y.; Dardick, A.; Redlich, M. γδT cells are essential for orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastille, E.; Konermann, A. Exploring the Role of Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Periodontium: Insights into Immunological Dynamics during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1428059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathapan Santhakumari, P.; Varma Raja, V.; Joseph, J.; Devaraj, A.; John, E.; Oommen Thomas, N. Impact of low-level laser therapy on orthodontic tooth movement and various cytokines in gingival crevicular fluid: a split-mouth randomized study. Cureus 2023, 15, e42809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yang, K. Clinical research: low-level laser therapy in accelerating orthodontic tooth movement. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.R.U.; Suzuki, S.S.; Suzuki, H.; Martinez, E.F.; Garcez, A.S. Photobiomodulation increases intrusion tooth movement and modulates IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1β expression during orthodontically bone remodeling. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, C.L.B.; de Souza Furtado, T.C.; Mendes, W.D.; Matsumoto, M.A.N.; Alves, S.Y.F.; Stuani, M.B.S.; Borsatto, M.C.; Corona, S.A.M. Photobiomodulation impacts the levels of inflammatory mediators during orthodontic tooth movement? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, P.; Kharbanda, O.P.; Monga, N.; Miglani, R.; Kapila, S. Effect of orthodontic forces on cytokine and receptor levels in gingival crevicular fluid: a systematic review. Prog. Orthod. 2014, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; Lima Brigagão, M.R.; Carli, M.L.; de Souza Ferreira, C.; de Oliveira Isac Moraes, G.; Hadad, H.; Costa Hanemann, J.A.; Hamblin, M.R.; Sperandio, F.F. Low-level laser therapy stimulates the oxidative burst in human neutrophils and increases their fungicidal capacity. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasik, M.; Gorska, E.; Modzelewska, M.; Nowicki, K.; Jakubczak, B.; Demkow, U. The influence of low-power helium-neon laser irradiation on function of selected peripheral blood cells. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2007, 58 Pt 2 (Suppl. 5), 729–737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kujawa, J.; Agier, J.; Kozłowska, E. Impact of photobiomodulation therapy on pro-inflammation functionality of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells – a preliminary study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, C.Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Liao, W.T.; Chen, Y.J.; Kuo, C.H.; Kuo, H.F.; Hung, C.H. Effects of low-level laser therapy on M1-related cytokine expression in monocytes via histone modification. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 625048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, W.; Wu, B. Photobiomodulation activates undifferentiated macrophages and promotes M1/M2 macrophage polarization via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.P.S.; Souza, N.H.C.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Silva, D.d.F.T.d.; Rocha, L.A.; Alves, A.N.; et al. Photobiomodulation with 660-nm and 780-nm laser on activated J774 macrophage-like cells: effect on M1 inflammatory markers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2015, 153, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Li, K.; Liang, Z.W.; Dai, C.; Shen, X.F.; Gong, Y.Z.; Wang, S.; Hu, X.Y.; Wang, Z. Low-level laser facilitates alternatively activated macrophage/microglia polarization and promotes functional recovery after crush spinal cord injury in rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Zheng, Q.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Li, K.; Song, J.; Ding, T.; Shen, X.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, L. Low-level laser therapy 810-nm up-regulates macrophage secretion of neurotrophic factors via PKA-CREB and promotes neuronal axon regeneration in vitro. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.Y.; Lin, T.; Chen, S.H.; Liao, Y.W.; Liu, C.M.; Yu, C.C. Er:YAG laser suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines expression and inflammasome in human periodontal ligament fibroblasts with Porphyromonas gingivalis-lipopolysaccharide stimulation. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.H.; Park, J.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, N.G.; Shin, Y.I. Photobiomodulation ameliorates inflammatory parameters in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and experimental animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1122581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Chiang, M.H.; Chen, P.H.; Ho, M.L.; Lee, H.E.; Wang, Y.H. Anti-inflammatory effects of low-level laser therapy on human periodontal ligament cells: in vitro study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, N.; Tomokiyo, A.; Gronthos, S.; et al. Immunomodulatory properties of PDLSC and relevance to periodontal regeneration. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2015, 2, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oner, F.; Kantarci, A. Periodontal Response to Nonsurgical Accelerated Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Periodontol. 2000, Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A.P.; Khoswanto, C.; Kriswandini, I.L. The involvement of damage associated molecular pattern and resolution associated molecular pattern in alveolar bone remodeling during orthodontic tooth movement: narrative review. Teikyo Med. J. 2022, 45, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, R.J.; Bohner, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bosshardt, D.D. Osteoinduction and Osteoimmunology: Emerging Concepts. Periodontology 2000 2024, 94, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Wong, P.; Li, J.; Lv, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhu, G.; He, M.; Luo, Y. Osteoimmunology: the correlation between osteoclasts and the Th17/Treg balance in osteoporosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 3591–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Yang, L.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, B. Matrix metalloproteinases and Th17 cytokines in the gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 22, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Lu L, Yu X. Interleukin-17A Interweaves the Skeletal and Immune Systems. Front Immunol. 2021, 11, 625034. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, A.; Zhou, H.; Liang, X.; Kang, N. The IL-17 level in gingival crevicular fluid as an indicator of orthodontically induced inflammatory root resorption. J. Orofac. Orthop. Epub ahead of print]. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Grassi, F.; Ryan, M.R.; Terauchi, M.; Page, K.; Yang, X.; Weitzmann, M.N.; Pacifici, R. IFN-gamma stimulates osteoclast formation and bone loss in vivo via antigen-driven T cell activation. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, Z.; Quan, H.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Gou, Y.; An, S.; Huang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, W.; Yi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Osteoimmunology in orthodontic tooth movement. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, J.; Shi, Z.; Xu, D.; Luo, S.; Siegal, G.P.; Feng, X.; Wei, S. Interleukin-4 inhibits RANKL-induced NFATc1 expression via STAT6: a novel mechanism mediating its blockade of osteoclastogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011, 112, 3385–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Velde, A.A.; Huijbens, R.J.; Heije, K.; de Vries, J.E.; Figdor, C.G. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) inhibits secretion of IL-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6 by human monocytes. Blood 1990, 76, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behm, C.; Zhao, Z.; Andrukhov, O. Immunomodulatory activities of periodontal ligament stem cells in orthodontic forces-induced inflammatory processes: current views and future perspectives. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 877348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settem, R.P.; Honma, K.; Chinthamani, S.; Kawai, T.; Sharma, A. B-cell RANKL contributes to pathogen-induced alveolar bone loss in an experimental periodontitis mouse model. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 722859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Y.; Han, X.; Yamashita, K.; Kitami, M.; Owaki, T.; Huang, G.T.; Sasaki, K.; Kurihara, H. Effect of adoptive transfer of antigen-specific B cells on periodontal bone resorption. J. Periodontal Res. 2006, 41, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Terauchi, M.; Vikulina, T.; Roser-Page, S.; Weitzmann, M.N. B Cell Production of Both OPG and RANKL Is Significantly Increased in Aged Mice. Open Bone J. 2014, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumida, T.S.; Cheru, N.T.; Hafler, D.A. The Regulation and Differentiation of Regulatory T Cells and Their Dysfunction in Autoimmune Diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Lv, H. Metabolic Disturbance and Th17/Treg Imbalance Are Associated with Progression of Gingivitis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 670178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, L. Osteoimmunology: The Crosstalk between T Cells, B Cells, and Osteoclasts in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, N.; Peng, J.; Yu, L.; Huang, S.; Xu, L.; Su, Y.; Chen, L. Orthodontic Treatment Induces Th17/Treg Cells to Regulate Tooth Movement in Rats with Periodontitis. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Cai, X.; Liu, C. Periodontal Ligament Cells under Mechanical Force Regulate Local Immune Homeostasis by Modulating Th17/Treg Cell Differentiation. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 3747–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Xia, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Song, W.; Yu, J.F.; Liang, L. Regulatory T Cells Promote Osteogenic Differentiation of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells through the Jagged1-Notch2 Signaling Axis. J. Dent. 2025, 158, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansaenroj, J.; Suwittayarak, R.; Egusa, H.; Samaranayake, L.P.; Osathanon, T. Mechanical Force Modulates Inflammation and Immunomodulation in Periodontal Ligament Cells. Med. Rev. 2024, 4, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Kim, M.; Han, J.A.; Choi, B.; Hwang, D.; Do, Y.; Yun, J.H. Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells Suppress T-Cell Proliferation via Down-Regulation of Non-Classical Major Histocompatibility Complex-Like Glycoprotein CD1b on Dendritic Cells. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, I.; Evans, R.; Kolb, B.; Naim, J.O.; Narayan, V.; Buehner, N.; Lanzafame, R.J. In vitro effects of low-level laser irradiation at 660 nm on peripheral blood lymphocytes. Lasers Surg. Med. 2000, 27, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsoy, M.; Ozer, G.H.; Bozkulak, O.; Tabakoglu, H.O.; Aktas, E.; Deniz, G.; Ertan, C. The biological effects of 632.8-nm low energy He-Ne laser on peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2006, 82, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Musawi, M.S.; Jaafar, M.S.; Al-Gailani, B.; Ahmed, N.M.; Suhaimi, F.M.; Suardi, N. Effects of low-level laser irradiation on human blood lymphocytes in vitro. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Shen, Q.; Chang, H.; Li, J.; Xing, D. Promoted CD4+ T cell-derived IFN-γ/IL-10 by photobiomodulation therapy modulates neurogenesis to ameliorate cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 and 3xTg-AD mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakubo, M.; Cunningham, T.J.; Demehri, S.; et al. Fractional laser releases tumor-associated antigens in poorly immunogenic tumor and induces systemic immunity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Brito, A.A.; Gonçalves Santos, T.; Herculano, K.Z.; Estefano-Alves, C.; de Alvarenga Nascimento, C.R.; Rigonato-Oliveira, N.C.; Chavantes, M.C.; Aimbire, F.; da Palma, R.K.; Ligeiro de Oliveira, A.P. Photobiomodulation therapy restores IL-10 secretion in a murine model of chronic asthma: relevance to the population of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells in lung. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 789426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Anjos, L.M.J.; Salvador, P.A.; de Souza, Á.C.; de Souza da Fonseca, A.; de Paoli, F.; Gameiro, J. Modulation of immune response to induced-arthritis by low-level laser therapy. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.H.; Lim, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Shin, C.Y.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Effect of 710-nm visible light irradiation on neuroprotection and immune function after stroke. Neuroimmunomodulation 2012, 19, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, A.; Albuquerque-Souza, E.; Gasparoni, L.M.; de França, B.N.; Pelissari, C.; Trierveiler, M.; Holzhausen, M. Therapeutic potential of periodontal ligament stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.R.R.; Dahlke, M.H. Immunomodulation by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): mechanisms of action of living, apoptotic, and dead MSCs. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).