1. Introduction

Cell mechanobiology is an emerging interdisciplinary field that investigates how cells perceive and respond to physical cues such as pressure, tension, stretch, and tissue stiffness. Increasing evidence suggests that mechanical alterations play a critical role in cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis [

1,

2]. Notably, alterations in cellular mechanotypes—reflected at the molecular level within the cytoskeleton, nucleoskeleton, and extracellular matrix—have been identified as a shared hallmark across diverse cancer types, representing a new frontier in cancer biology [

3].

Understanding how mechanical forces influence cellular biochemistry and behavior—an area known as mechanocontrol—provides critical insight into cancer biology. In cancer, mechanobiological regulation reveals fundamental aspects of tumor progression that may be overlooked when examined solely through genetic or biochemical lenses. This perspective is particularly valuable in oncology, where the dynamic interplay between mechanical, genetic, and biochemical cues plays a decisive role in cancer development and metastasis [

4]. Investigating this triad not only deepens our understanding of cancer biology but also paves the way for the development of more precise prognostic tools and innovative therapeutic strategies tailored to individual patients, thereby advancing the goals of personalized medicine.

Among the emerging areas of interest in cancer mechanobiology, mechanoreceptors—somatosensory receptors that transduce mechanical stimuli into intracellular biochemical signals via mechanically gated ion channels—were reported to play a significant role in regulating tumor cell behavior. Mechanosensitive (MS) ion channels were identified as key components of the cellular tensegrity architecture, acting as primary mechanoreceptors that converted mechanical cues into biochemical responses [

5,

6]. Through direct physical coupling with cytoskeletal elements, MS channels were shown to detect and respond to subtle changes in mechanical load, positioning them as essential mediators of cellular mechanotransduction [

7].

At the nanoscale, mechanical forces were found to induce conformational changes in structural and regulatory cellular components—including proteins, ion channels, and chromatin—which in turn modulated protein activity, gene expression, and ultimately, cell behavior [

2,

8,

9]. These effects were reported to be particularly pronounced in cancer, where aberrant mechanotransduction contributed to tumor progression, metastasis, and resistance to therapy [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Importantly, the cellular response to mechanical stimuli was described as highly context- and cell-type-specific, influencing key processes such as proliferation, cytoskeletal organization, adhesion dynamics, signaling pathway activation, membrane mechanics, and cell volume regulation [

15,

16,

17].

In recent years, MS ion channels have gained significant attention for their ability to translate mechanical forces from the tumor microenvironment into biochemical signals that influence cancer cell behavior. Among the most well-studied MS channels in this context were Piezo1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), and transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1). These channels were described as being activated by a range of mechanical stresses—such as compression, stretch, and shear—and were shown to mediate calcium influx, thereby initiating downstream signaling cascades that regulated proliferation, migration, invasion, and therapy resistance [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Piezo1 was strongly implicated in tumor growth and metastasis through its regulation of mechanotransduction pathways and cytoskeletal remodeling [

24]. Similarly, TRPV1 and TRPA1, although originally characterized for their roles in pain perception and inflammation, were increasingly recognized for their involvement in cancer cell adaptation to mechanical and oxidative stress [

25,

26,

27]. Collectively, these channels were identified as critical components of the cellular machinery that enables tumor cells to sense and respond to the dynamic mechanical landscape of solid tumors.

Cancer biomechanics has been shown to influence various aspects of solid tumor development and progression, including cell proliferation, invasion, and therapy resistance [

28]. Osteosarcoma, the most common primary malignant bone tumor—has been recognized for exhibiting distinctive features that make it an excellent model for investigating how cancer cells perceive and exploit mechanical cues [

29]. Importantly, OS often arises during adolescence—a developmental period marked by rapid skeletal growth and dynamic remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM). OS originates in bone, the most mechanically active tissue in the body, where resident cells are routinely subjected to uniaxial stretching and compressive forces due to weight-bearing and locomotion [

30].

Despite therapeutic advances, OS has remained a highly aggressive tumor characterized by poor clinical outcomes, rapid disease progression, and resistance to conventional chemotherapies [

29,

31,

32,

33,

34]. One hallmark of OS cells has been their altered nucleoskeletal architecture relative to healthy osteoblasts, particularly in the expression and organization of structural proteins such as lamins and emerin, which are essential for nuclear integrity and mechanotransduction [

35,

36].

To investigate OS cell mechanobiology, our group developed a standardized uniaxial cyclic stretch protocol (24 hours, 1 Hz, 0.5% elongation) that mimics in vitro physiological mechanical forces experienced by bone cells in vivo. This mechanical stretching model has been widely adopted in vitro to study how bone-derived tumors respond and reorient themselves to cyclic mechanical loading [

17,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Using this approach, we demonstrated that a physiologically relevant stretch regimen selectively affected osteosarcoma cells while sparing healthy human osteoblasts (hFOB) [

32,

42]. Specifically, cyclic stretch induced phenotypic and behavioral alterations in two OS cell lines: SAOS-2, a moderately differentiated and less aggressive line, and U-2 OS, a poorly differentiated and highly aggressive line. In contrast, hFOB cells showed negligible responses, indicating that malignant osteoblastic cells exhibit subtype-specific alterations in mechanosensitivity. These findings support the notion that OS cells reprogram normal mechanosensing pathways to support tumor progression.

In our most recent studies, we further demonstrated that mechanical activation of MS ion channels led to a non-canonical activation of Src kinase in osteosarcoma cells [

42]. Src was previously reported to function as a central node in cellular mechanotransduction, acting as a key integrator of cytoskeletal tension and converting mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals that regulated cell behavior [

43]. Supporting this, recent findings in macrophages identified a cytoskeleton-dependent Src–H3 acetylation axis, linking mechanical inputs to epigenetic remodeling, altered morphology, and changes in cell motility [

44]. Previously, we observed that cyclic stretch–induced Src activation in OS cells correlated with increased cell migration, altered adhesion dynamics, and enhanced sensitivity to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis, while having minimal impact on proliferation. These effects underscored the functional significance of mechanosensitive Src signaling in driving malignancy-related behaviors in OS.

Moreover, the subcellular localization of Src was described as being dynamically regulated by mechanical cues [

45]. Mechanical stimulation was shown to induce Src redistribution from the plasma membrane to the cytosol, and under specific conditions, to the nucleus [

46]. Such translocation events were reported to be particularly relevant in pathological contexts—including fibrosis and cancer—where nuclear Src was implicated in transcriptional regulation [

36,

47]. Collectively, these findings supported the existence of a tumor-specific, mechanosensitive Src signaling axis in osteosarcoma, which warrants further investigation. This pathway was not only reported to contribute to the aggressive phenotype of OS cells [

42] but also represents a promising target for mechanobiology-informed therapeutic strategies [

45].

Building on our previous findings—which demonstrated that LE135, a dual agonist of the mechanosensitive ion channels TRPV1 and TRPA1, could chemically replicate the cellular effects of mechanical stimulation in human osteosarcoma cells [

42,

48]—the present study aimed to further explore the potential for chemically controlling MS channel–dependent mechanosignaling in OS.

To investigate the role of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in OS mechanobiology, we conducted a targeted screening of mechanosensitive ion channel agonists and antagonists, assessing their capacity to mimic or inhibit the cellular responses typically induced by mechanical stimulation.

Among the available chemical activators of TRPV1, we selected capsaicin, a bioactive alkaloid derived from chili peppers, based on several key criteria. First, capsaicin was the prototypical and most extensively characterized TRPV1 agonist, widely used in both experimental and clinical settings [

49,

50,

51,

52]. Second, as a naturally occurring nutraceutical, capsaicin is routinely encountered by human cells through dietary intake or topical exposure, increasing its physiological relevance. Third, micromolar concentrations of capsaicin were shown to exert anti-cancer effects in several tumor models—including breast, prostate, and osteosarcoma—highlighting its potential as a therapeutic candidate [

53,

54,

55].

In the present study, we compared the effects of MS channel activation and inhibition on U-2 OS, SAOS-2, and hFOB cells by evaluating morphological and molecular alterations using a multimodal approach. This included confocal and atomic force microscopy (AFM), and functional assays to assess changes in metastatic behaviors, such as cell adhesion, migration, and chemosensitivity to two of standard MAP chemotherapy agents—doxorubicin, and cisplatin.

Crucially, we investigated whether the cytoskeleton-dependent Src–H3 acetylation axis, previously identified by our group and others as a key mediator of cellular mechanosensation, could be activated by chemical stimulation of MS channels and whether this response converges with the signaling triggered by mechanical stimuli, such as cyclic stretch.

Together, these approaches provided a powerful framework for dissecting the roles of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in MS channel–mediated signaling. By establishing parallels between chemical and mechanical activation, this work offered novel insights into how cancer cells exploited mechanotransduction to support tumor progression, metastatic potential, and therapy resistance in mechanically dynamic microenvironments.

3. Discussion

Osteosarcoma, the most common primary malignant bone tumor, posed a formidable clinical challenge due to its profound heterogeneity, complex microenvironment, and resistance to conventional therapies [

59,

60]. Despite decades of combined surgical and chemotherapeutic strategies, survival rates plateaued, and the presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis continued to confer poor prognosis [

61,

62]. While significant progress had been made in delineating molecular subtypes and identifying therapeutic targets through genomic profiling and molecular classification [

63,

64], the biomechanical properties of the osteosarcoma cells remained underexplored.

Growing evidence suggested that mechanical cues—such as matrix stiffness, cellular adhesion forces, and extracellular vesicle-mediated mechanotransduction—played a critical role in tumor progression, invasion, and therapeutic resistance [

59]. Understanding how osteosarcoma cells perceive and respond to mechanical stimuli was expected to uncover novel vulnerabilities, thereby complementing existing molecular and immunological treatment strategies [

62,

65].

Given that alterations in cellular mechanoproperties have been linked to changes in morphology, migration, adhesion dynamics, proliferation, and alignment [

66,

67], we employed uniaxial cyclic stretching to investigate how osteosarcoma cells reprogram normal mechanosensing pathways to support aggressive behavior. When cyclic stretch is applied uniaxially—that is, along a single axis—cells undergo strain aligned with the direction of force. Their adaptive responses are highly cell type-specific: while some cells align with the direction of stretch, others reorient perpendicularly to minimize mechanical stress. A well-documented response to cyclic stretch in many adherent cell types was the reorientation of the actin cytoskeleton and cellular long axis nearly perpendicular to the direction of stretch, a process shown to be Src-dependent [

68].

In our previous study, we observed that SAOS-2 cells failed to reorient within 24 hours of cyclic stretch exposure, maintaining their original alignment [

32]. By contrast, others reported that U-2 OS cells reoriented perpendicularly, reorganizing their cytoskeleton to escape sustained strain [

39]. In line with these findings, the present study demonstrates that U-2 OS cells exhibit a remarkable capacity for reorientation, responding even to mild cyclic stretch (0.5% elongation). Moreover, in line with date reported in literature [

69,

70,

71], present study indicated that this reorientation depended on proper TRPV1 activation and was indirectly reliant on actin filament remodeling and calcium-dependent signaling, as evidenced by the effects of AMG 9810, cytochalasin D, and indomethacin treatments.

TRPV1, also known as the capsaicin receptor, thermal receptor, or pain receptor, is a non-selective cation channel that shares features with many MS channels. It has been distinguished by its role as a true multisensor, capable of responding to a broad spectrum of endogenous stimuli—including mechanical forces, heat, low pH, lipid metabolites, and inflammatory mediators [

72]. Although initially characterized in the context of pain perception and inflammation [

73], TRPV1 had increasingly been implicated in cancer cell adaptation to mechanical and oxidative stress [

25]. Mechanical activation of TRPV1 was shown to trigger downstream signaling cascades that regulate key oncogenic processes such as proliferation, migration, invasion, and therapy resistance [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

In this study, we demonstrated that TRPV1—reported to be comparably expressed across the two OS cell lines in the Human Protein Atlas database of cancer cells (

https://www.proteinatlas.org)—functions as a central node in the mechanotransduction machinery of OS cells, while showing no apparent role in mechanoregulation in healthy hFOB osteoblasts, for which no comparable expression data are available. Specifically, TRPV1 activity played a prominent role in regulating both morphological adaptation and drug responsiveness under mechanical stimulation in OS cells. In the present study, we found that our experimental conditions successfully chemically mimicked the TRPV1-mediated responses typically induced by mechanical stretch. Capsaicin, a well-studied nutraceutical compound [

49,

50,

51,

52], and its selective TRPV1 antagonist AMG9810, extensively used in preclinical models of pain, inflammation and cancer [

25,

74], were both effective in modulating TRPV1 activity in OS cells while sparing healthy hFOB osteoblasts.

By treating cells with nanomolar concentrations of capsaicin (50 nM), we chemically activated TRPV1 while avoiding the off-target effects and cytotoxicity often observed at micromolar levels [

53,

54,

55]. In parallel, AMG9810 at 560 nM, preincubated to outcompete the agonist, effectively antagonized TRPV1 under the same conditions. This study demonstrated that chemical and mechanical activation of TRPV1 elicited similar phenotypic responses in OS cell models. Interestingly, both compounds effectively modulated TRPV1-dependent pathways in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells, while sparing hFOB cells, underscoring their selectivity and highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting TRPV1 in OS without compromising normal bone cell integrity.

This study demonstrated that both chemical and mechanical activation of TRPV1 induced comparable responses in the OS models tested, notably increasing nuclear dimensions and migration rate. Interestingly, our results showed that TRPV1 activation elicited divergent effects on the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio and adhesion dynamics in SAOS-2 and U-2 OS cells—two features previously associated with metastatic potential [

75,

76].

Ultrastructural analysis using AFM microscopy, complemented by fractal dimension analysis—a powerful quantitative method previously employed to distinguish between healthy and cancerous cervical epithelial cells [

57], and to evaluate the effects of actin polymerization inhibitors on cell boundary roughness in human epithelial cells [

58] revealed distinct differences in surface complexity and peripheral architecture between the two OS subtypes. Supporting these findings, immunofluorescence microscopy and detachment assays demonstrated that TRPV1 activation in U-2 OS cells promoted the formation of lamellipodia-like, actin-rich protrusions and enhanced initial adhesion, features associated with increased adhesion plasticity. In contrast, SAOS-2 cells exhibited minimal morphological remodeling, highlighting subtype-specific differences in mechanosensitivity, likely reflecting underlying intrinsic molecular variations [

77].

At the molecular level, our data demonstrated that the Src–histone H3 acetylation (acH3) mechanosignaling axis, previously identified by our group and others as a key mediator of cellular mechanosensation [

44], was tightly regulated by TRPV1 activation—regardless the activation method (mechanical or chemical).

Histone H3 acetylation and Src expression are known to regulate gene expression, cell signaling, and cancer progression [

78], while aberrant acetylation and elevated Src levels are associated with enhanced tumorigenicity [

79,

80]. Notably, we found that TRPV1 functions as a molecular switch, exhibiting subtype-specific modulation: it upregulates the Src–acH3 axis in U-2 OS cells, whereas it downregulates the same pathway in SAOS-2 cells.

Notably, we found that TRPV1 acted as a molecular switch, upregulating the Src–acH3 axis in U-2 OS cells, while downregulating it in SAOS-2 cells. Given that Src interacts with lamin A/C [

45] a key structural protein of the nuclear envelope [

35,

81], and has been previously detected in the nucleus of OS cells [

35,

36], our findings suggest that TRPV1 modulated Src subcellular localization in a subtype-dependent manner. Specifically, TRPV1 activation either promoted nuclear translocation or induced cytoplasmic extrusion of Src, with minimal impact on hFOB cells. This subtype-specific spatial regulation of Src supports the hypothesis that TRPV1 fine-tunes epigenetic and transcriptional responses through localization-dependent control of Src, thereby contributing to the to the mechanobiological heterogeneity across OS subtypes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Chemical Materials

Osteosarcoma cell lines Human SAOS-2 (HTB-85), U-2 OS (HTB-96) and human fetal osteoblast cell line hFOB (CRL-3602) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). The osteosarcoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (4.5 g/L glucose) (DMEM), while 1.19 hFOB were cultured in Ham’s F-12 Nutrient Mixture (F-12) medium (1:1) (Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). They were both supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Euroclone s.p.a., Milano, Italy), Penicillin–Streptomycin Solution 100X (Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and Amphotericin B 100X (Biowest, Riverside, MO, USA) within cell culture flasks at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5 % CO2. Rat type I collagen (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) was used for coating cell plates. The culture medium was changed twice a week, during which non-adherent cells were discarded.

4.2. Mechanical Stretch Application

Cells were cultured on deformable silicone plates (CellScale Biomaterials Testing) and subjected to cyclic uniaxial stretch (0.5% elongation, 4830 µε) along the x-axis using the MechanoCulture FX device at 1 Hz for 24 hours, following a 1-hour stretch/3-hour rest cycle as previously described [

32,

42]. Two plates were prepared per experiment: one stretched and one static control. Stretching was also performed in the presence of specific ion channel blockers. Analyses were conducted immediately post-stimulation either on-plate or on harvested cells; lasting effects were assessed on reseeded cells on glass (

Supplementary Figure S1). Fluorescence and spectrometry measurements on plates were performed using a custom tray for optimal positioning on a TECAN Spark microplate reader [

32].

4.3. Chemical Activation and Inhibition of MS Channels Through Soluble Compounds

To assess whether chemical activation could replicate the effects of stretch stimulation of MS ion channel. Each osteosarcoma cell line was seeded on collagen precoated conventional tissue culture supports and then incubated under conventional culturing conditions with either 50 nM Capsaicin, a selective agonist of TRPV1 channel (Y0000671, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and 50 nM ASP7663, selective activator of the TRPA1 channel (SML1467, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 hours. Cells were seeded at different densities according to the assay: density of 1,5 × 10⁴ cells per well in 24-well plates for confocal and fluorescence microscopy, 400 cells per well in 96-well plates for Adhesion Assay, 1.5 × 10⁴ cells per well in 96-well plates for Wound healing Assay and 220 cells/mm² cells per well in 96-well plates for Cytotoxicity assay. Cotreatment experiments were conducted by repeating all procedures following a 30-minute preincubation with 560 nM AMG9810 (AMG), a selective and competitive TRPV1 antagonist (S6934, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, USA), in both U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cell lines. AMG9810, a potent aryl cinnamide-class inhibitor (IC₅₀ in the low nanomolar range; [

74]), was used at 560 nM—approximately 10 times higher than the capsaicin dose—to ensure sustained and effective blockade of both chemical and mechanical TRPV1 activation.

4.4. Cell Count and Protein Extraction and Quantification

Immediately after treatment, both TRPV1-activated and control cells were trypsinized and counted using two automated, chip-based systems: the TECAN Spark multimode reader (Tecan Group, Switzerland) and the NucleoCounter® NC-200® automated cell counter, employing the Via1-Cassette™ cell sampling and staining cartridge (ChemoMetec A/S, Allerød, Denmark). Following counting, cells were centrifuged and washed with PBS. Histones were isolated from the pellet via acid extraction as described by us [

42]: pellets were incubated overnight in 0.2 N HCl at 4°C, centrifuged, and the supernatant neutralized with 2 M NaOH. Protein concentrations were measured by Bradford assay and DC Protein Assay (BioRad) using BSA standards, with absorbance read at 595 nm on the TECAN Spark.

4.5. Cell Viability Assay and Cytotoxicity Assay

To determine drug efficacy, the effect of mechanical or chemical pre-treatment on doxorubicin- or cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity was assessed using an MTT assay (Merk Life Science, Milano, Italy) as described previously [

42,

56] (

Supplementary Figure S1). Cells were seeded on silicone plates at a density of 220 cells/mm², allowed to adhere, and then stretched cyclically for 24 hours in the presence or absence of 560nM AMG9810. For the assays conducted on conventional supports, cells were seeded at the same density on 96-well plates, allowed to adhere, and then pretreated with 50 nM Capsaicin for 24 hours. They were then treated for 24 h with serum-free medium containing doxorubicin (0–20 μM) or cisplatin (0–60 μM). After treatment, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS with Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 2 h. Formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 100 μL of extraction buffer (5% SDS in N,N-dimethylformamide), followed by another 2 h incubation under the same conditions. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Tecan Infinite®200 PRO reader. Cell viability was calculated as the ratio of absorbance in treated wells to control (untreated) wells. Experiments included three biological replicates with at least three technical replicates per condition.

4.6. Confocal Microscopy

Confocal images were acquired from cells seeded at a density of 110 cells/mm² on rat type I collagen-coated (50 µg/mL) silicone plates or conventional glass coverslips, as previously described [

32]. Following mechanical or chemical stimulation, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, then rinsed with ultrapure water.

Imaging was performed using an Olympus LEXT OLS 4000 confocal microscope equipped with a 405 nm laser and ×20 (NA 0.60) or ×50 (NA 0.95) objectives. Images were captured over areas of 648 × 648 µm or 258 × 258 µm, respectively, at a resolution of 4096 × 4096 pixels (~0.025 µm/pixel). All images were exported as TIFF files for subsequent analysis.

4.7. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

After mechanical or biochemical activation of the TRPV1 channel—with or without the antagonist AMG9810—cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. Following an additional PBS wash, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 minutes, then blocked with 10% donkey serum in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies, diluted in 0.1% BSA in PBS:

SRC: (1:100, #sc-32789, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX, USA)

β-Tubulin: (1:100, #GTX101279, GeneText Irvine, CA, USA)

The next day, glass coverslips and silicone wells were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with Hoechst 33342 (1:600, #33342, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), along with the appropriate secondary antibodies diluted in 0.1% BSA in PBS:

Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:400, #A21206, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA)

Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:400, #A10037, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA)

To visualize peripheral actin structures in U-2 OS cells, samples were also stained with Phalloidin–iFluor 488 (1:1000, #ab176753, Abcam, MA, USA).

After final washes in PBS, samples were mounted using ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Fluorescence imaging was performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope at 20×, 40×, and 100× magnifications.

4.8. Microscopy Image Analyses

Confocal and immunofluorescence images were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, USA) to quantitatively compare morphological differences between control and treated samples (

Supplementary Figure S1). Nuclear size was measured from Hoechst-stained immunofluorescence images, following the protocol described by us [

42]. Images were binarized, and the Fit Ellipse function in ImageJ was used to determine the minimum enclosing ellipse for each nucleus. At least 30 cells per condition were analyzed across three biological replicates.

For nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio analysis, confocal images were used. The total cell area was manually outlined using the freehand selection tool, and the nuclear area was determined via elliptical selection. Measurements were conducted on at least 27 cells per condition across three biological replicates.

4.9. Cell Re Orienteering Along x Stretching Axis

To investigate the effect of uniaxial cyclic stretch on cell reorientation across different cell types, we subjected cells to mechanical strain at 1 Hz for 24 hours. Three cell types were analyzed: SAOS-2, U-2 OS, and hFOB. Cell nuclei were fluorescently stained, and their orientation was quantified using an ellipse-fitting method (

Supplementary Figure S2).

The orientation angle (φ) was defined as the angle between the major axis of each fitted ellipse and the direction of uniaxial stretch (i.e., the x-axis). These angles were then transformed into the orientation parameter cos(2φ), which enabled classification of nuclear alignment. Perpendicular orientation was defined within the range −1 ≤ cos(2φ) ≤ −0.5, and parallel orientation within 0.5 ≤ cos(2φ) ≤ 1

Supplementary Figure S2.

To evaluate the involvement of TRPV1 mechanosensitive ion channels, U-2 OS cells were co-treated with the specific TRPV1 antagonist AMG9810 during stretch stimulation. Additionally, to investigate the cytoskeletal structure involved in nuclear reorientation process, U-2 OS cells were treated with either 1 µM cytochalasin D (to disrupt actin polymerization) or 1 µM indomethacin (to interfere with calcium mobilization and focal adhesion formation).

4.10. Adhesion Assay

Cell adhesion following mechanical or biochemical activation of the TRPV1 channel was assessed as previously described ([

32];

Supplementary Figure S1). Pre-treated cells, with or without co-treatment with 560 nM AMG9810, were trypsinized, counted, and seeded into 96-well plates pre-coated with rat type I collagen at a density of 400 cells/well in DMEM high glucose/Ham’s F-12 (1:1) medium.

After 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C under standard culture conditions, wells were gently washed and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 20% methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 minutes. Excess dye was removed through thorough washing with water.

Adherent cells were imaged using an Olympus CKX53 inverted microscope equipped with an EP50 digital camera. Adhesion was quantified by counting stained cells in 10 randomly selected fields per well at 4× magnification using ImageJ software (NIH, USA). Data represent the mean of three independent experiments, each performed with six technical replicates per condition

4.11. Detachment Assay

The detachment assay was performed as described in [

82]. Briefly, SAOS-2 or U-2 OS cells were seeded and treated as outlined in the adhesion assay. After 24 hours of incubation, initial images were captured. To induce detachment, the plates were incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C with vigorous shaking (240 rpm). The remaining attached cells were then stained with crystal violet as described above, and final images were taken. Detachment was quantified as the percentage of remaining attached cells relative to the initial cell number.

4.12. Western Blotting Analysis

Following mechanical stimulation, treated cells and their counterparts were trypsinized, pelleted, and their protein content were quantified as described above (

Supplementary Figure S1). Total protein extracts (15–30 µg/lane) or histone acid extracts (1–3 µg/lane) were resolved on 4–20 % Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ precast gels (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) as described in [

42]. Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Amersham, UK), blocked at room temperature with either 5 % non-fat milk for 2 hours or EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (BioRad)for 5 minutes, washed and then and incubated with primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) system (Amersham, UK). The following primary antibodies were used:

GAPDH (1:10,000, GTX100118, GeneTex)

Src (1:500, #2108, Cell Signaling Technology)

Histone H3 (1:2000, ab1791, Abcam)

Acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys9/Lys14) (1:500, #9677, CST)

Band intensities were quantified in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and expressed in arbitrary units (AU). Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (version 9.0.0), based on three independent experiments.

4.13. Wound Healing Assay (Scratch Assay)

Chemically or mechanically activated cells (with or without mechanosensitive channel inhibitor) were compared for their migrative capacity as previously described [

42]. Pretreated cells and their counterparts were seeded into collagen-pre-coated 96-well plates at 1 × 10⁴ cells/well (

Supplementary Figure S1). After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C with 5 % CO₂, confluent monolayers were scratched using a 10 µL pipette tip, and wells were rinsed with PBS to remove detached cells, as previously described. Cells were then cultured in serum-free DMEM, with or without 560nM AMG9810 and incubated for another 24 h.

Scratch closure was imaged at 0 h and 24 h using an Olympus CKX53 microscope with an EP50 digital camera. Wound closure percentage (WC%) and relative wound density (RWD) were quantified using ImageJ (NIH, USA) and a Spark multi-mode plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland), respectively. Statistical analysis was performed on three independent experiments with at least four technical replicates per condition.

4.14. Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis

AFM measurements were performed using a custom-built atomic force microscope operating in the repulsive regime of contact mode under ambient conditions and room temperature, as previously described [

32]. Briefly, imaging was carried out using Bruker silicon nitride MSNL-10 cantilevers. Constant-force topographic images were acquired with an applied force of approximately 1 nN, at a typical scan rate of 2–4 seconds per line, and with a spatial resolution of 10 nm per pixel.

Post-acquisition data processing—including contrast enhancement, edge mask extraction, and box-counting analysis—was performed using Gwyddion software (open-source platform for SPM data analysis) and custom scripts developed in Python.

4.15. AFM-Based Quantification of Cell Edge Architecture Complexity

Fractal dimension (FD) analysis offers a robust quantitative approach for assessing surface complexity in biological systems. In this study, we applied the box-counting method for FD analysis, a well-established technique for quantifying the irregularity of self-similar structures such as cell boundaries (see

Supplementary Materials, Formula 1,

Supplementary Figure S6).

Unlike standard Euclidean metrics, which are suited for simple geometric shapes (e.g., lines or smooth curves), FD analysis is particularly effective in capturing the complexity of biologically relevant, irregular architectures. This method has previously been used to differentiate between healthy and cancerous cervical epithelial cells based on atomic force microscopy (AFM) surface scans [

57], and to evaluate boundary roughness following actin polymerization inhibition in human epithelial cells [

58].

In the present work, FD analysis was applied to AFM images of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. Each scan was initially processed by cropping to isolate the individual cell outline, followed by contrast enhancement to improve the accuracy of edge detection (

Supplementary Figure S6A,B). A one-pixel-wide binary edge mask was then generated to represent the cell perimeter (

Supplementary Figure S6C), enabling precise quantification of edge complexity using the box-counting approach.

Notably, high-resolution AFM imaging allowed clear visualization of lamellipodia-like protrusions approximately 100 nm in width (

Figure S6D), underscoring AFM’s capability to resolve sub-diffraction limit features that are typically undetectable with conventional light microscopy.

Fractal dimension values were computed from the extracted edge masks using the box-counting method, as illustrated in

Figure S6 E. This approach enabled quantitative comparison of cell edge complexity across different treatment conditions, providing insights into cytoskeletal dynamics and morphological responses

4.16. Automated Analysis of Nuclear c-Src Fluorescence

Fluorescence images were analyzed using CellProfiler (v4.2.8; Cimini Lab, Broad Institute) through an automated pipeline adapted from ImageJ-based workflows, as described [

83] in

The Open Lab Book [

84]. Six datasets were processed, each comprising three experimental conditions (including two hFOB Ctrl-Cap conditions). For each condition, a minimum of seven paired images (nucleus and c-Src channels) were analyzed. The same pipeline was applied across all datasets, with minor adjustments made to optimize object detection when needed.

Images were preprocessed to correct background noise, followed by segmentation of nuclei and c-Src regions. A peripheral region was also generated around each cell to quantify background fluorescence. Nuclear morphology metrics and fluorescence intensity data were extracted from raw images.

To assess nuclear c-Src levels, Corrected Total Cell Fluorescence (CTCF) was calculated using the formula:

where:

Raw data were exported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365) for CTCF calculation and further visualized and analyzed using GraphPad Prism (v10.4, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.17. Figure Creation

Schematic illustrations were designed using Microsoft PowerPoint, while GIMP, the GNU Image Manipulation Program, was used for image editing and pot-processing. Biological components, including cell membranes, ion channels and the nucleus, were retrieved from Bioicons [

85]. Icons representing cellular features such as edge architecture, height, migration, adhesion, reorientation and “nuclear Src” were made using the open-source software Inkscape (version 1.3.2, Inkscape Project). Other icons used were sourced from external providers: “Gears symbol” (noun-gears-7119093) by Agus Hartanto, “Chili pepper” (noun-chili-pepper-7209702) by Cherry, “Pill” (noun-pill-6867596) by KIS, all from The Noun Project [

86].

4.18. Data Analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences between means were evaluated using a parametric t-test using in GraphPad Prism 9.01 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Significance levels were indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01, * **p < 0.001, and * ** *p < 0.0001.

Author Contributions

Arianna Buglione: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Writing – review & editing. Giulia Alloisio: Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Chiara Ciaccio: Validation, Formal analysis Writing – review & editing. David Becerril Rodriguez: Software, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization Writing – review & editing. Simone Dogali: Software, Resources, Methodology. Luisa Campagnolo: Formal analysis Writing – review & editing. Marco Luce: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Stefano Marini: Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Antonio Cricenti: Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Magda Gioia: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

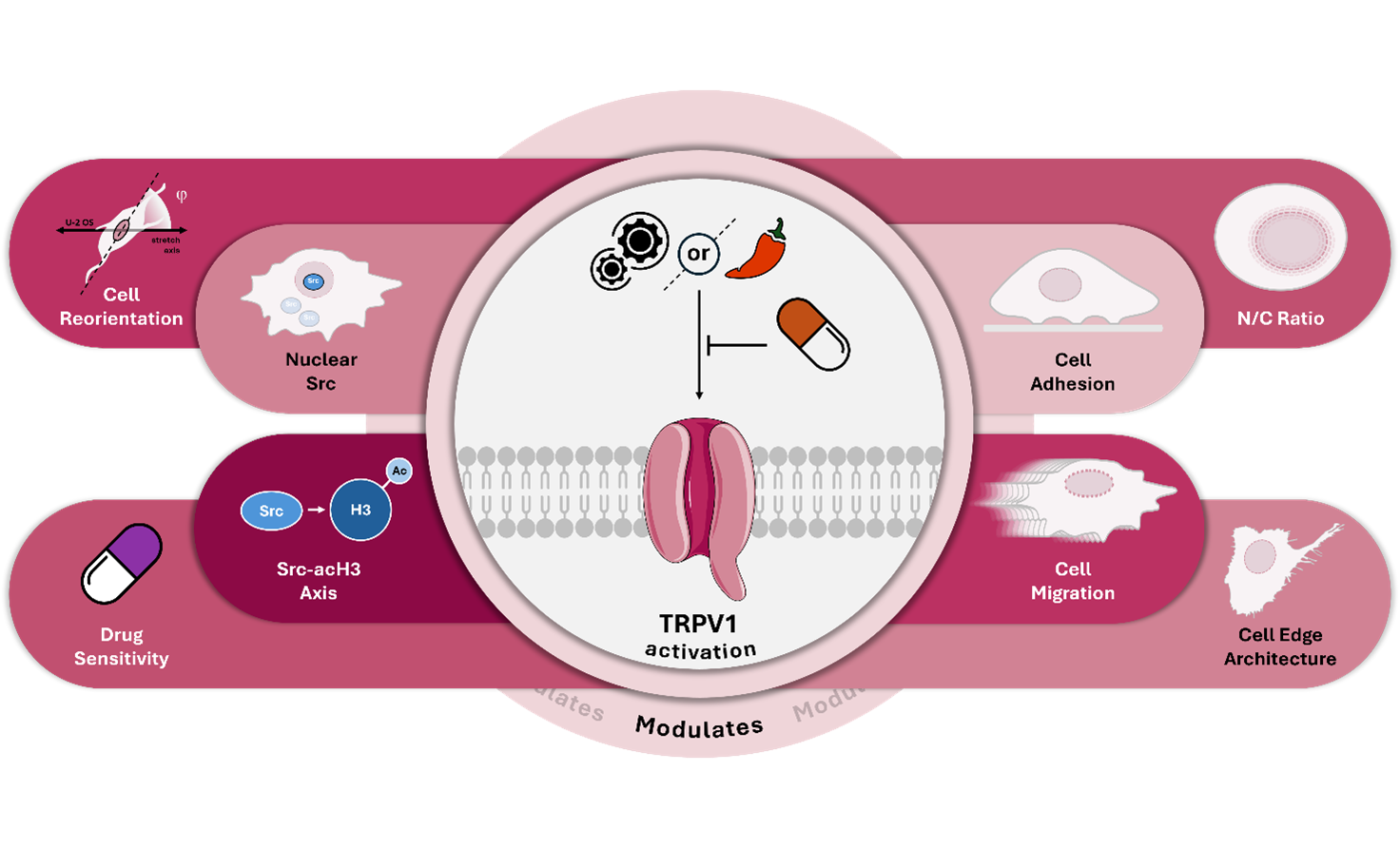

Figure 1.

Inactivation of TRPV1 Ion Channels by AMG9810 Counteracts Mechanical Responses OS Cells. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of Hoechst-stained nuclei in control (s Ctrl), cyclically stretched (1 Hz), and stretched cells co-treated with either the TRPV1 inhibitor AMG9810 (I) or the TRPA1 inhibitor HC030031 (H) Images were acquired at 20X magnification. Scale bar = 25 µm. Nuclear enlargement induced by mechanical stretch is attenuated by AMG9810, as illustrated by column bar plots showing mean ± SD for each condition. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.52. Data represent three biological replicates, with a minimum of 30 cells analyzed per condition. (B) Confocal microscopy images of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells under the same conditions mentioned above. Scale bar = 100 µm. Quantification of nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio is shown as bar graphs. Data represent three biological replicates, each with at least three technical replicates and a minimum of 25 cells per condition. (C) AMG9810 co-treatment blocks the mechanically induced enhancement of migratory capacity in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. (D) Co-treatment with AMG9810 prevents the stretch-induced increase in adhesive capacity of U-2 OS cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. (E) AMG9810 reverses mechanically induced changes in chemosensitivity to doxorubicin and cisplatin in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test. All data are derived from the best of three biological replicates, each with at least four technical replicates per condition. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 1.

Inactivation of TRPV1 Ion Channels by AMG9810 Counteracts Mechanical Responses OS Cells. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of Hoechst-stained nuclei in control (s Ctrl), cyclically stretched (1 Hz), and stretched cells co-treated with either the TRPV1 inhibitor AMG9810 (I) or the TRPA1 inhibitor HC030031 (H) Images were acquired at 20X magnification. Scale bar = 25 µm. Nuclear enlargement induced by mechanical stretch is attenuated by AMG9810, as illustrated by column bar plots showing mean ± SD for each condition. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.52. Data represent three biological replicates, with a minimum of 30 cells analyzed per condition. (B) Confocal microscopy images of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells under the same conditions mentioned above. Scale bar = 100 µm. Quantification of nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio is shown as bar graphs. Data represent three biological replicates, each with at least three technical replicates and a minimum of 25 cells per condition. (C) AMG9810 co-treatment blocks the mechanically induced enhancement of migratory capacity in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. (D) Co-treatment with AMG9810 prevents the stretch-induced increase in adhesive capacity of U-2 OS cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. (E) AMG9810 reverses mechanically induced changes in chemosensitivity to doxorubicin and cisplatin in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test. All data are derived from the best of three biological replicates, each with at least four technical replicates per condition. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

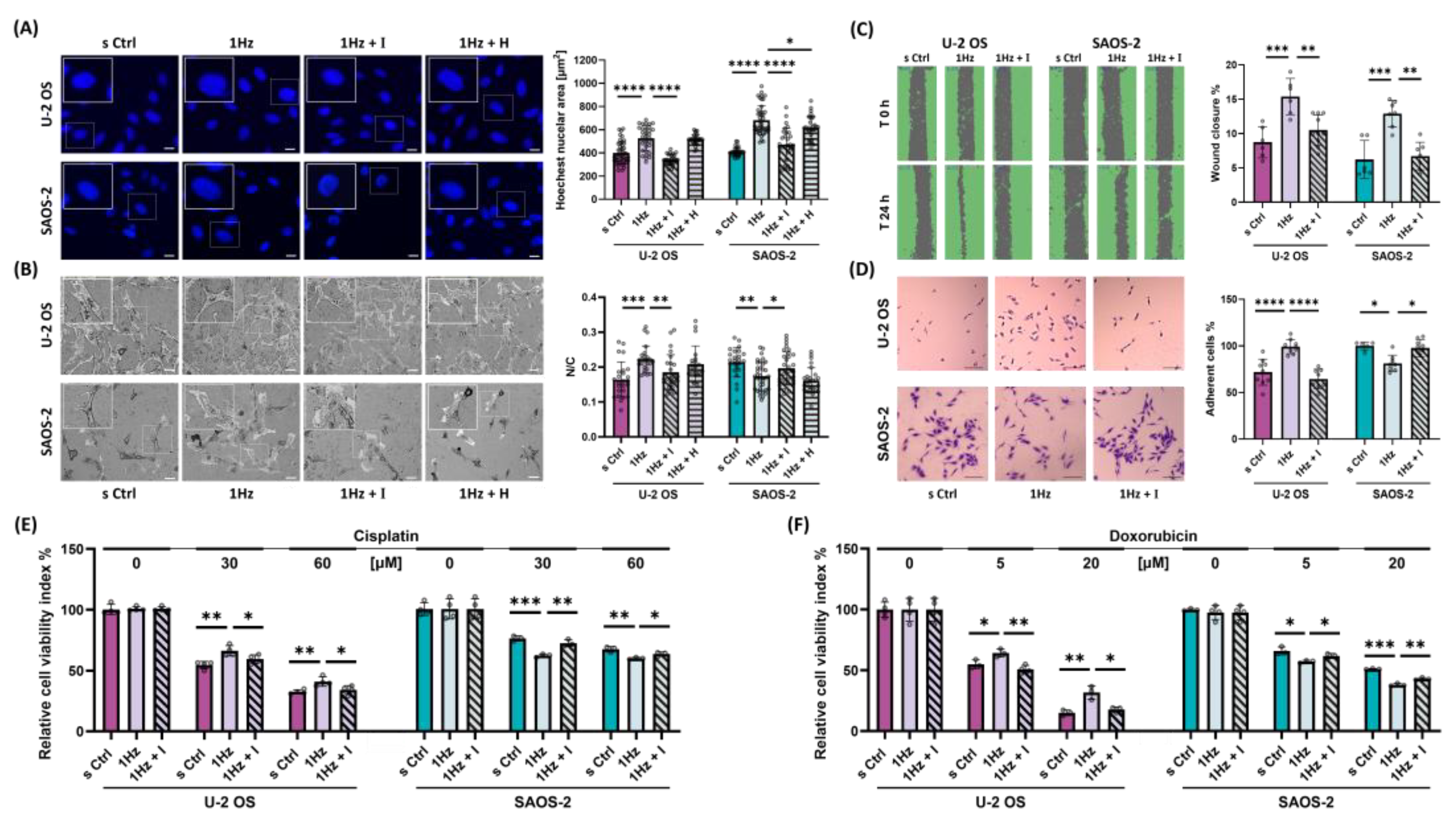

Figure 2.

1 Hz–24 h Mechanical Stretch induces cell Orientation in U-2 OS Cells via TRPV1 activation. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of U-2 OS cells stained with Hoechst (nuclei), β-tubulin (cytoskeleton), and merged channels. Images were acquired at 40X magnification. Scale bar = 25 μm. (B) Nuclear orientation was quantified by fitting an ellipse to the nuclear outline and measuring the angle φ between the ellipse’s major axis and the direction of applied cyclic stretch. Orientation is expressed as ⟨cos 2 φ ⟩, where a value of 1 indicates nuclei aligned parallel to the stretch direction, −1 indicates perpendicular alignment, and 0 indicates random orientation. (C) Violin plots display the distribution of nuclear orientation values in SAOS-2, U-2 OS, and hFOB cells. (D) Violin plots show nuclear orientation in stretched U-2 OS cells treated with 560 nM AMG9810 (TRPV1 inhibitor), 2 nM Cytochalasin D (actin polymerization inhibitor), or 1 µM Indomethacin (COX inhibitor). All analyses were performed on three biological replicates, with at least 45 cells analyzed per condition.

Figure 2.

1 Hz–24 h Mechanical Stretch induces cell Orientation in U-2 OS Cells via TRPV1 activation. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of U-2 OS cells stained with Hoechst (nuclei), β-tubulin (cytoskeleton), and merged channels. Images were acquired at 40X magnification. Scale bar = 25 μm. (B) Nuclear orientation was quantified by fitting an ellipse to the nuclear outline and measuring the angle φ between the ellipse’s major axis and the direction of applied cyclic stretch. Orientation is expressed as ⟨cos 2 φ ⟩, where a value of 1 indicates nuclei aligned parallel to the stretch direction, −1 indicates perpendicular alignment, and 0 indicates random orientation. (C) Violin plots display the distribution of nuclear orientation values in SAOS-2, U-2 OS, and hFOB cells. (D) Violin plots show nuclear orientation in stretched U-2 OS cells treated with 560 nM AMG9810 (TRPV1 inhibitor), 2 nM Cytochalasin D (actin polymerization inhibitor), or 1 µM Indomethacin (COX inhibitor). All analyses were performed on three biological replicates, with at least 45 cells analyzed per condition.

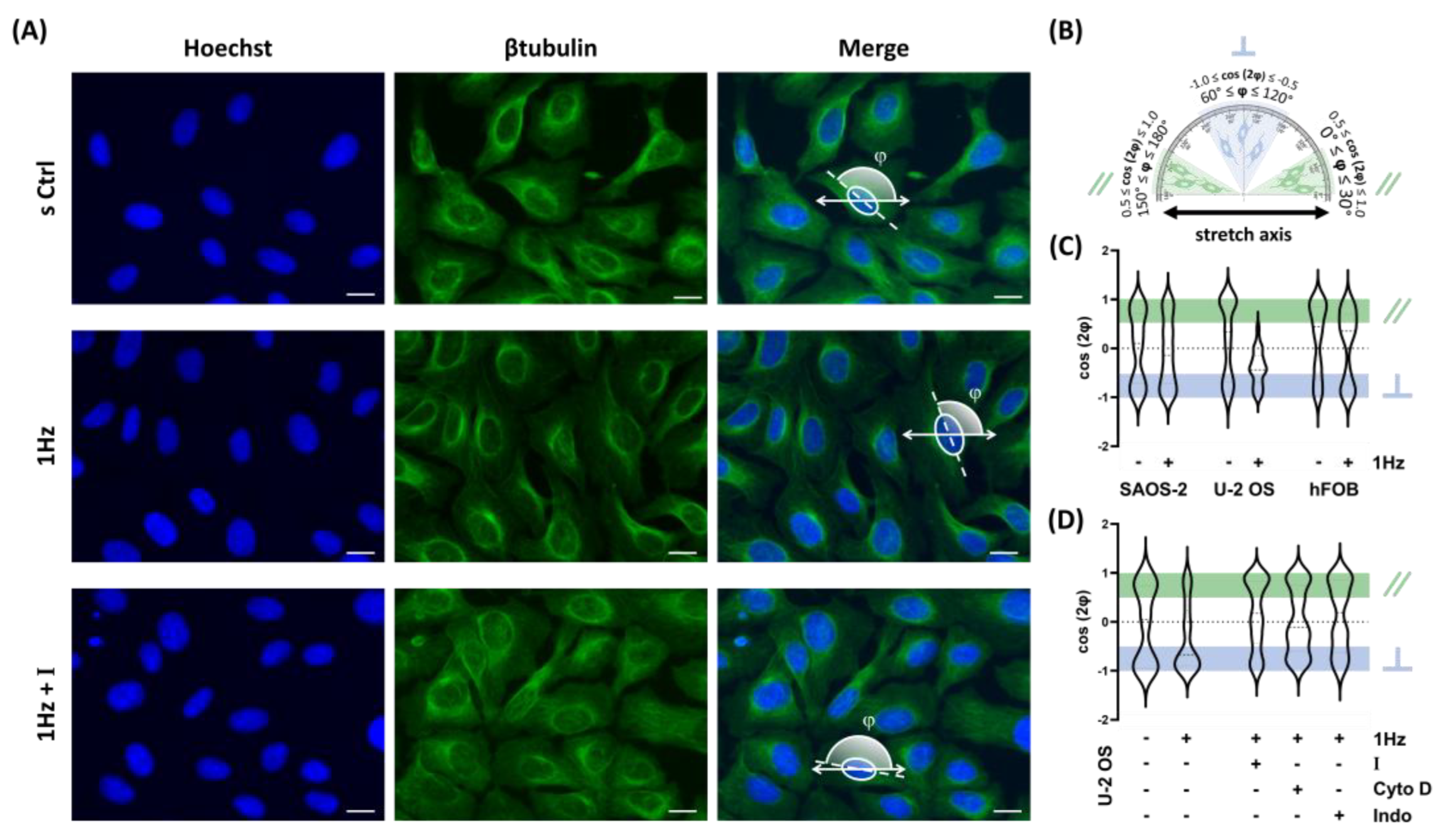

Figure 3.

Capsaicin and Its Antagonist AMG9810 Modulate OS Mechanotransduction by Activating or Blocking TRPV1 Channels. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images showing the effects of soluble channel-specific agonists on nuclear morphology. Cells were treated with 50 nM Capsaicin (CAP; TRPV1 agonist) or 50 nM ASP (ASP; TRPA1 agonist). To assess specificity, CAP treatment was also performed in the presence of 560 nM AMG9810, a TRPV1-specific antagonist (CAP+I). Hoechst-stained nuclear areas were quantified using the binary function in ImageJ v1.52. Magnification: 20X; scale bar: 25 µm. Data represent three biological replicates, with a minimum of 30 cells per condition. (B) Representative confocal microscopy images and corresponding quantification of the nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N/C) ratios in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells treated with 50 nM ASP50 or 50 nM Capsaicin, with or without AMG9810. Magnification: 20x, scale bar: 100 μm. Bar plots display mean ± SD of N/C ratios. The analysis includes three biological replicates with at least 25 cells per condition. (C) Migration assays showing the impact of capsaicin, with or without AMG9810, on the migratory ability of both OS cell lines. (D) The effect of Capsaicin treatment (with or without co-treatment with AMG9810) on the adhesion capability of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Shows the relative cell viability of hFOB, U-2 OS, and SAOS-2 cell lines after treatment with increasing concentrations of capsaicin (50nM). (F and G) Relative cytotoxicity of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells treated with 50nM Capsaicin with or without co-treatment with560nM AMG9810 after a 24 hours incubation with cisplatin (0-60 µM) or doxorubicin (0–20 µM). For each experiment, statistical analyses were performed on the most representative of three biological replicates, each comprising a minimum of four technical replicates per condition. Statistical significance between treated and control samples was determined using Student’s t-test, with significance levels indicated as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 3.

Capsaicin and Its Antagonist AMG9810 Modulate OS Mechanotransduction by Activating or Blocking TRPV1 Channels. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images showing the effects of soluble channel-specific agonists on nuclear morphology. Cells were treated with 50 nM Capsaicin (CAP; TRPV1 agonist) or 50 nM ASP (ASP; TRPA1 agonist). To assess specificity, CAP treatment was also performed in the presence of 560 nM AMG9810, a TRPV1-specific antagonist (CAP+I). Hoechst-stained nuclear areas were quantified using the binary function in ImageJ v1.52. Magnification: 20X; scale bar: 25 µm. Data represent three biological replicates, with a minimum of 30 cells per condition. (B) Representative confocal microscopy images and corresponding quantification of the nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N/C) ratios in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells treated with 50 nM ASP50 or 50 nM Capsaicin, with or without AMG9810. Magnification: 20x, scale bar: 100 μm. Bar plots display mean ± SD of N/C ratios. The analysis includes three biological replicates with at least 25 cells per condition. (C) Migration assays showing the impact of capsaicin, with or without AMG9810, on the migratory ability of both OS cell lines. (D) The effect of Capsaicin treatment (with or without co-treatment with AMG9810) on the adhesion capability of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Shows the relative cell viability of hFOB, U-2 OS, and SAOS-2 cell lines after treatment with increasing concentrations of capsaicin (50nM). (F and G) Relative cytotoxicity of U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells treated with 50nM Capsaicin with or without co-treatment with560nM AMG9810 after a 24 hours incubation with cisplatin (0-60 µM) or doxorubicin (0–20 µM). For each experiment, statistical analyses were performed on the most representative of three biological replicates, each comprising a minimum of four technical replicates per condition. Statistical significance between treated and control samples was determined using Student’s t-test, with significance levels indicated as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 4.

TRPV1 activation modulates OS cell peripheral ultrastructure altering cell adhesive properties. (A) Image represent topographic AFM scans of OS cell acquired on rigid glass substrates. Purple and green highlights indicate the cell regions AFM-analyzed for peripheral roughness and protrusion complexity, respectively. (B) Bar plots show the quantitative comparison of peripheral roughness in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells treated with 50 nM capsaicin on rigid glass substrates. (C) Fractal dimension (FD) analysis of cell edge complexity, based on high-resolution AFM images of OS cells, treated with 50mM with or without co-treatment with 560 nM AMG9810. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of filamentous actin (phalloidin) in U-2 OS cells subjected to mechanical or chemical activation of TRPV1, with or without co-treatment with AMG9810. Images acquired at 100X magnification. Scale bar = 25 µm. (E) Effect of TRPV1 activation—either mechanical or chemical—on cell detachment, assessed with or without co-treatment with AMG9810. All experiments were performed in triplicate, with at least eight biological replicates per condition. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. Significance levels are indicated as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 4.

TRPV1 activation modulates OS cell peripheral ultrastructure altering cell adhesive properties. (A) Image represent topographic AFM scans of OS cell acquired on rigid glass substrates. Purple and green highlights indicate the cell regions AFM-analyzed for peripheral roughness and protrusion complexity, respectively. (B) Bar plots show the quantitative comparison of peripheral roughness in U-2 OS and SAOS-2 cells treated with 50 nM capsaicin on rigid glass substrates. (C) Fractal dimension (FD) analysis of cell edge complexity, based on high-resolution AFM images of OS cells, treated with 50mM with or without co-treatment with 560 nM AMG9810. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of filamentous actin (phalloidin) in U-2 OS cells subjected to mechanical or chemical activation of TRPV1, with or without co-treatment with AMG9810. Images acquired at 100X magnification. Scale bar = 25 µm. (E) Effect of TRPV1 activation—either mechanical or chemical—on cell detachment, assessed with or without co-treatment with AMG9810. All experiments were performed in triplicate, with at least eight biological replicates per condition. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. Significance levels are indicated as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 5.

TRPV1 activation modulates expression and nuclear localization Src in OS cells. (

A, B, C and D) Representative Western blot images and their respective densitometric analyses of cell extract from U-2 OS or SAOS-2. (

A and C) Western blot showing SRC (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) protein levels following mechanical stretch or 50 nM capsaicin treatment, with or without co-treatment with 560 nM AMG9810 respectively.

(B and D) Western blot bands displaying the protein levels of acetylated histone 3 (acH3, 17 kDa) and Histone 3 (H3 17 kDa) in acidic histone extracts from the same conditions as above. (

E and F) Representative immunofluorescence images of nuclei (Hoechst), Src protein, and merged channels in OS cells subjected to mechanical stretch or capsaicin treatment, with or without co-treatment with AMG9810. Quantitative analysis of Src nuclear levels was performed using corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF), and results are reported as bar plots (mean ± SD). (

G and H) Western blot and CTCF analysis of Src in hFOB cells under mechanical stretch or capsaicin treatment. Densitometric analysis of the Western blot bands was performed using ImageJ 1.52 software and quantified in arbitrary units. CellProfiler 4.2.8 was used to identify nuclear SRC fluorescence intensity and area values (

Supplementary Table S1). Data represent three biological replicates, with a minimum of 45 cells analyzed per condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was conducted on at least three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired

t-test, with results shown as mean ± SD; p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 5.

TRPV1 activation modulates expression and nuclear localization Src in OS cells. (

A, B, C and D) Representative Western blot images and their respective densitometric analyses of cell extract from U-2 OS or SAOS-2. (

A and C) Western blot showing SRC (60 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) protein levels following mechanical stretch or 50 nM capsaicin treatment, with or without co-treatment with 560 nM AMG9810 respectively.

(B and D) Western blot bands displaying the protein levels of acetylated histone 3 (acH3, 17 kDa) and Histone 3 (H3 17 kDa) in acidic histone extracts from the same conditions as above. (

E and F) Representative immunofluorescence images of nuclei (Hoechst), Src protein, and merged channels in OS cells subjected to mechanical stretch or capsaicin treatment, with or without co-treatment with AMG9810. Quantitative analysis of Src nuclear levels was performed using corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF), and results are reported as bar plots (mean ± SD). (

G and H) Western blot and CTCF analysis of Src in hFOB cells under mechanical stretch or capsaicin treatment. Densitometric analysis of the Western blot bands was performed using ImageJ 1.52 software and quantified in arbitrary units. CellProfiler 4.2.8 was used to identify nuclear SRC fluorescence intensity and area values (

Supplementary Table S1). Data represent three biological replicates, with a minimum of 45 cells analyzed per condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was conducted on at least three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired

t-test, with results shown as mean ± SD; p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

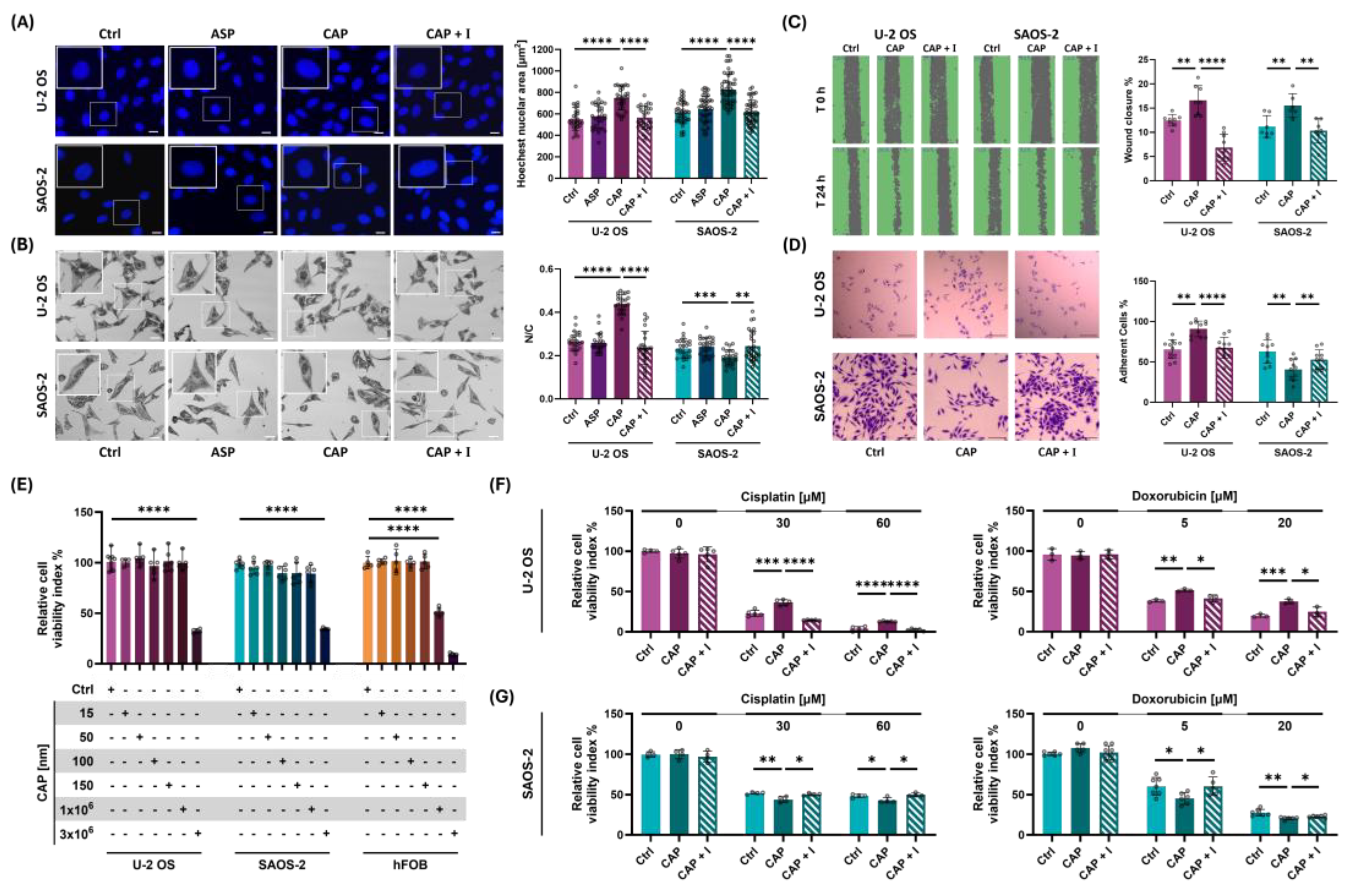

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the proposed mechanism by which TRPV1 regulates the Src–acH3 mechanosignaling axis in osteosarcoma cells. TRPV1 appears to play a central role in modulating histone3 acetylation by influencing the subcellular localization of Src, thereby contributing to the phenotypic divergence observed between osteosarcoma subtypes. In the SAOS-2 cell model (left), TRPV1 activation downregulates the Src–acH3 axis, resulting in reduced nuclear Src levels. In contrast, in the U-2 OS model (right), TRPV1 activation upregulates the axis by promoting nuclear translocation of Src.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the proposed mechanism by which TRPV1 regulates the Src–acH3 mechanosignaling axis in osteosarcoma cells. TRPV1 appears to play a central role in modulating histone3 acetylation by influencing the subcellular localization of Src, thereby contributing to the phenotypic divergence observed between osteosarcoma subtypes. In the SAOS-2 cell model (left), TRPV1 activation downregulates the Src–acH3 axis, resulting in reduced nuclear Src levels. In contrast, in the U-2 OS model (right), TRPV1 activation upregulates the axis by promoting nuclear translocation of Src.