Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

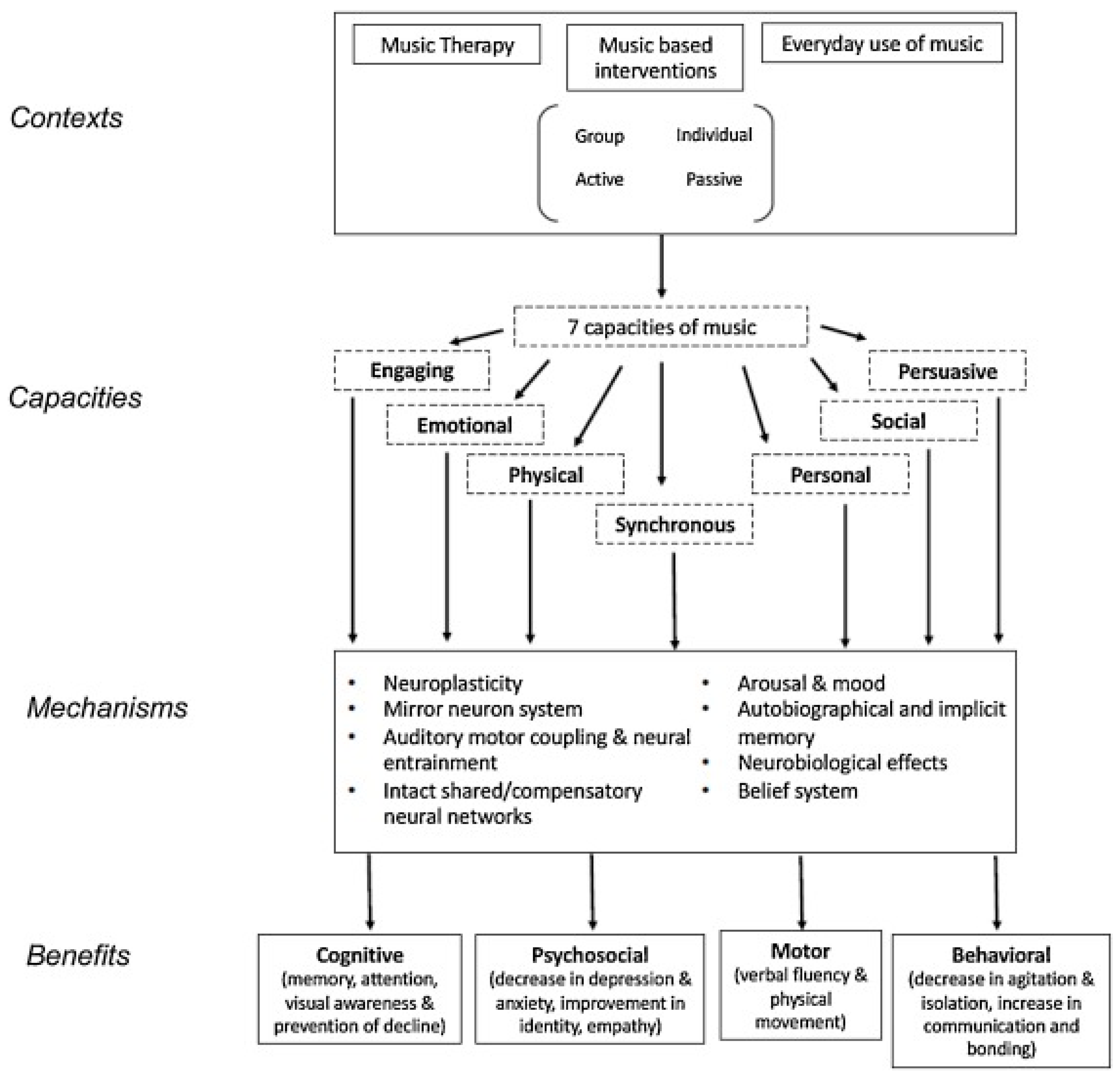

- Music Therapy in Theory and Clinical Practice

- Research in Music Therapy for Neurological Conditions

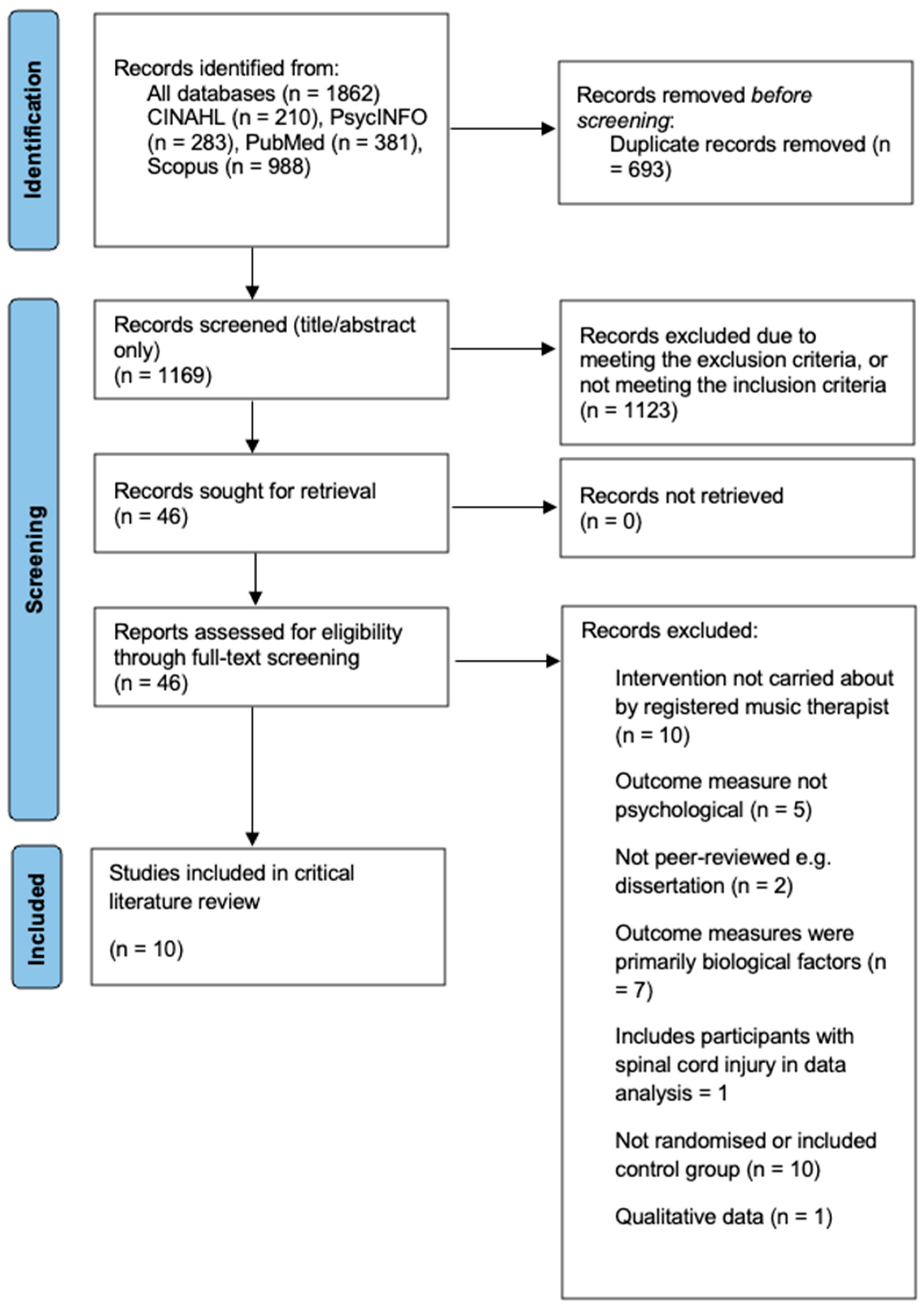

Method

- Search Strategy

- Search terms

- SWiM Approach

Results

- Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Study design | Sample size | Age (mean years) | Sex (female) | Neurological condition | Location and research setting | Outcome measures | Music Therapy intervention | Comparator | |

| Chou et al. (2024) [81] | RCT pilot study | 82 | 58 | 28% | Stroke | Taiwan, inpatient setting | BDI-II, MMSE, MRS, BI Timepoints: Before and after intervention |

Neurologic Music Therapy – Therapeutic Singing, Melodic Intonation Therapy, Rhythmic Speech Cueing, Therapeutic Instrument Music Playing, Music Cognitive Training (from neurologic music therapy) (in addition to treatment as usual) Frequency: Four hours over four weeks (extra to neurorehabilitation as normal) |

Conventional therapy (treatment as usual) |

| Haire et al. (2021 [52] | RCT | 30 | 55.9 | 47% | Stroke | Toronto, Canada, community setting | TMT-B, FDST, GSES, MAAC-R, SAM Timepoints: Two baseline assessments one-week apart. One post-intervention assessment. |

Therapeutic Instrumental Music Performance (TIMP) Frequency: Three times a week for three weeks |

The comparator groups consisted of TIMP plus cued motor imagery and TIMP plus motor imagery without external cues |

| Poćwierz-Marciniak & Bidzan (2017) [54] | RCT | 61 | 64 | 78.7% | Stroke | Gdynia, Poland, inpatient neurological rehabilitation hospital | SF-36, SA-SIP30, Cantril Ladder Timepoints: Before and after intervention |

Cognitive Music Therapy, Guided Imagery and Music, 1:1 Frequency: Twice a week for five weeks |

Standard care (physiotherapy, ergotherapy, psychological diagnosis, maintenance psychotherapy) |

| Raglio et al. (2017) [11] | RCT pilot | 38 | 72.7 | 58% | Stroke | Pavia, Italy, inpatient neurological rehabilitation hospital | HADS, MQOL-It Timepoints: Before and after intervention |

Relational Active Music Therapy (RAMT) Frequency: Three sessions per week, 20 sessions total |

Standard care (physiotherapy, occupational therapy) |

| Segura et al. (2024) [32] | RCT | 58 | 63.2 | 24% | Stroke | Barcelona, Spain, ex-inpatient neuro-rehabilitation | BRIEF, SART, Figural Memory subtest from the WMS-R, AVLT, Verbal Fluency test in Spanish, BDI-II, self- and informant-version of AES, POMS, SIS, TSRQ, IMI, Strategies Used to Promote Health Timepoints: Before and after intervention, with 3-month follow-up |

Enriched Music-supported Therapy Frequency: Once a week music therapy, plus three weekly individual self-training session, for 10 weeks |

Graded Repetitive Arm Supplementary Program (GRASP) only |

| Impellizzeri et al. (2020) [79] | RCT pilot study | 30 | 51 | 37% | Multiple Sclerosis | Messina, Italy, clinic centre setting | BRB-N, MSQOL-54, BDI, EAQ, MMF Timepoints: Before and after intervention |

Neurologic Music Therapy – Associative mood and memory training, Music in psychosocial training and counselling (half of the treatment-as-usual time replaced with music therapy intervention) Frequency: Three times per week for 8 weeks |

Treatment-as-usual (same number of sessions as the music therapy group) |

| Impellizzeri et al. (2024) [49] | Pilot Quasi-RCT | 40 | 62.45 | 30% | Parkinson’s disease | Messina, Italy, clinic centre setting | MoCA, HRSD, FAB, Stroop test, Visual search test Timepoints: Before and after intervention |

Computer-Assisted Rehabilitation Environment (CAREN), Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation, Therapeutic Instrumental Music Performance Frequency: Three sessions per week for eight weeks |

Standard treatment with CAREN selected scenarios three times per week |

| Lee et al. (2024) [51] | RCT | 27 | 73.3 | 52% | Parkinson’s disease | Arizona, USA, Tremble Clefs therapeutic singing group | HY, GDS, VRQOL, VASM Timepoints: Before and after intervention (VASM only) |

Therapeutic Group Singing (TGS), Straw Phonation Combined with Therapeutic Singing (SP+TGS) Frequency: Single session |

Speaking-only control group |

| Siponkoski et al. (2020) [50] | Cross-over RCT | 40 | 41.3 | 41% | Traumatic Brain Injury | Helsinki, Finland, brain injury clinic setting | FAB, Number-Letter Task, Auditory N-back Task, Simon Task, SART, Similarities, Block Design, and Digit Span subtests of the WAIS-IV, Words Lists I and II subtests of the WMS-III Timepoints: Before and after intervention, follow-up (3 and 6 months) |

Rhythmical Training, Structured Cognitive-motor Training, Assisted music playing Frequency: Twice per week, for 20 sessions |

Standard care (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, neuropsychological rehabilitation, speech therapy) |

| Van Bruggen-Rufi et al. (2017) [53] | RCT | 63 | 54.4 | 68.3% | Huntington’s disease | Netherlands, set in four specialised Huntington’s disease care facilities | BOSH – social-cognitive functioning subscale and the mental rigidity and aggression subscale, PBA Timepoints: Before intervention, halfway (8th session), end of intervention (16th session), follow-up (12 weeks after intervention) |

Followed protocol “music therapy for Huntington’s patients on improving and stimulating communication and self-expression" Frequency: One session per week, for 16 weeks |

Recreational therapy (with treatment guide offered in same circumstances as music therapy group e.g. reading the newspaper, cooking, arts and crafts, handwork, puzzles/games) |

- Quality Appraisal and Risk of Bias

- Randomisation

- Deviations from Intended Interventions

- Missing Outcome Data

- Measurement of the Outcome

- Selection of the Reported Results

- Data Synthesis and Key Findings

- Within-group Findings

- Between-group Findings

- Certainty of Evidence using GRADE

- Risk of Bias

- Inconsistency

- Indirectness

- Imprecision

- Publication Bias

- Overall Certainty of Evidence and Importance of Outcome

Discussion

Conclusion

Appendix A

| Search terms inputted into the four databases. |

| Search terms for PubMed and Scopus: [“music* therap*”] AND [neurorehab* OR neuro-rehab* OR “neuro* rehab*” OR neurologic* OR “neurologic* condition*” OR “neurologic* disorder*” OR Parkinson* OR “brain injur*” OR TBI OR “traumatic brain injur*” OR ABI OR “acquired brain injur*” OR “brain tumour*” OR “brain tumor*” OR “multiple sclerosis” OR MS OR stroke* OR encephal* OR epileps* OR “motor neurone disease*” OR MND OR Huntington* OR HD OR “disorder* of conscious*” OR DOC OR “minimal* conscious*” OR vegetative OR “unresponsive wakeful* syndrome*”] |

| Search terms for PsycInfo and CINAHL: |

| [music* therap*] AND [neurorehab* OR neuro-rehab* OR neuro* rehab* OR neurologic* OR neurologic* condition* OR neurologic* disorder* OR Parkinson* OR brain injur* OR TBI OR traumatic brain injur* OR ABI OR acquired brain injur* OR brain tumour* OR brain tumor* OR multiple sclerosis OR MS OR stroke* OR encephal* OR epileps* OR motor neurone disease* OR MND OR Huntington* OR HD OR disorder* of conscious* OR DOC OR minimal* conscious* OR vegetative OR unresponsive wakeful* syndrome*] |

|

Note. Search fields were limited to title and abstract for all databases, with the addition of keywords in PsycINFO and Scopus. Search terms were identified from previous literature and neurorehabilitation service provisions, alongside support from a specialist librarian at the University of Leicester |

Appendix B

| Neurological condition | Psychological outcome | Reported effect direction | Effect size (Cohen’s d) | p-value | Mean difference [95% CI] | |

| Chou et al. (2024) [81] | Stroke | Cognitive function | ↑ → |

Not reported. Calculated as 0.40 (within-group intervention), 0.00 (between-group) |

<0.001 (within-group) 0.355 (between group) |

1.04 [0.51-1.57] 0.02 [-2.88-2.83] |

| Mood (depression) | → → |

Not reported. Calculated as 0.16 (within-group intervention), 0.02 (between-groups) |

0.129 (within-group) 0.740 (between-group) |

-0.84 [-1.93-0.25] -0.05 [-2.80-2.90] |

||

| Haire et al. (2021) [52] | Stroke | Cognitive function | → | Not reported. Trail-making test: Calculated as 0.12 (within-group MT only) 0.27 (within-group MT+cMI) 0.27 (within-group MT+MI) Digit span test: Calculated as 0.09 (within-group MT only) 0.00 (within-group MT+cMI) 0.10 (within-group MT+MI) |

Trail-making test: 1.00 (MT only) 0.125 (MT+cMI) <0.05 (MT+MI) Digit span test: 0.459 (MT only) 0.865 (MT+cMI) 0.669 (MT+MI) |

Not reported |

| Affect | → | Not reported. Calculated as 0.34 (within-group MT only) 0.40 (within-group MT+cMI) 0.47 (within-group MT+MI) |

0.105 (MT only) <0.05 (MT+cMI) 0.261 (MT+MI) |

Not reported | ||

| Mood | → | Not reported. Calculated as 0.28 (within-group MT only) 0.90 (within-group MT+cMI) 0.05 (within-group MT+MI) |

0.147 (MT only) <0.05 (MT+cMI) 0.492 (MT+MI) |

Not reported | ||

| Self-efficacy | → |

Not reported. Calculated as 0.21 (within-group MT only) 0.35 (within-group MT+cMI) 0.02 (within-group MT+MI) |

0.202 (MT only) 0.098 (MT+cMI) 1.00 (MT+MI) |

Not reported | ||

| Poćwierz-Marciniak & Bidzan (2017) [54] | Stroke | Quality of life | ↑* |

Not reported. Not calculated due to multiple measures used for outcome. | <0.05 (between-groups) for some scales | Not reported |

| Raglio et al. (2017) [11] | Stroke | Quality of life | ↑ |

Not reported. Calculated as 0.18 (between-group) | 0.19 (between-group) | Not reported |

| Mood (depression) | ↑ | Not reported. Calculated as 0.04 (between-group) | <0.05 (between-group) | Not reported | ||

| Mood (anxiety) | → |

Not reported. Calculated as 0.24 (between-group) |

0.25 (between-group) | Not reported | ||

| Segura et al. (2024) | Stroke | Cognitive functions | →* |

Not reported. Not calculated due to volume of measures for outcome. | >0.05 on subscales (between-group) at post-intervention or follow-up. | Refer to original paper, not reported here due to volume of measures used. |

| Emotion | ↑* | Not reported. Not calculated as 0.69 (between-group) post-intervention, 0.10 (between-group) at follow-up. | <0.05 subscale (between-group) at post-intervention. Not significant at follow-up. | Refer to original paper, not reported here due to volume of measures used. | ||

| Mood | ↑* | Not reported. Not calculated due to volume of measures for outcome. | <0.05 on one subscale (between-group) at post-intervention. Not significant at follow-up. | Refer to original paper, not reported here due to volume of measures used. | ||

| Impellizzeri et al. (2020) [79] | Multiple sclerosis | Cognitive function | ↑* ↑* |

Not reported. Not enough information provided (no standard deviation) | Overall battery outcome not reported. 4/9 subscales <0.05 within-group experimental) otherwise non-significant. | No overall outcome results provided. |

| Mood (depression) | ↑ ↑ |

Not reported. Not enough information provided (no standard deviation) | <0.05 (within-group experimental) 0.278 (within-group control) |

5.60 [3.7-7.72] -0.66 [-1.93-0.60] |

||

| Emotion | ↑* ↑* |

Not reported. Not enough information provided (no standard deviation) No overall outcome results provided. |

<0.05 for all subscales (within-group experimental) |

No overall outcome results provided. |

||

| Quality of life | ↑ ↑ |

Not reported. Not enough information provided (no standard deviation). | <0.05 for all subscales (within-group experimental) |

No overall outcome results provided. |

||

| Impellizzeri et al. (2024) [49] | Parkinson’s disease | Cognitive function | ↑ ↑* |

Not reported. Reported the median, skewed data effect sizes to be discussed with statistician if time allowed. | <0.05 (within-group experimental) <0.05 within some sub-scales (between- group) |

Not reported for change scores. |

| Lee et al. (2024) [51] | Parkinson’s disease | Mood | ↑* |

Not reported. Not calculated due to multiple subtests for outcome. | <0.05 sad, anxious, angry (within-group) 0.127 happy (within-group) |

Not reported |

| Siponkoski et al. (2020) [50] | Traumatic brain injury | Cognitive function | ↑* |

Not reported. Executive function - η2p=0.093 (medium-large) Set-shifting – η2p=0.112 (medium-large) Note these are not directly comparable to Cohen’s d. |

<0.05 (between-group) for executive functions, >0.05 (between-group) set-shifting, >0.05 (between-group) for reasoning and verbal memory | |

| Van Bruggen-Rufi et al. (2017) [53] | Huntington’s disease | Social-cognitive function | ↓ | Not reported. Not calculated due to limited data available. | <0.05 (between-groups) | 2.88 [0.108-5.65] |

| Behaviour | → |

Not reported. Not calculated due to limited data available. | 0.125 (between groups) on BOSH 0.630 (between groups on PBA-S |

4.60 [-1.32-10.52] -1.39 [-7.16-4.38] |

||

| ↑ = music therapy significantly improved the outcome, over the control group; → = no significant effect of music therapy was found for the outcome, over the control group; ↓ = the control group significantly improved the outcome, over music therapy; *= the direction of effect is not based on one standardised measure, but a number of subtests where a proportion showed significant results. MI=motor imagery, cMI=metronome-cued motor imagery, CI=confidence interval. | ||||||

Appendix C

| Studies (outcome(s) measured in study) | Neurological condition | Cognitive function (CF) | Mood (M) | Emotion (E) | Behaviour (B) | Quality of life (QoL) |

| Chou et al. (2024) (CF, M) [81], Poćwierz-Marciniak & Bidzan (2017) (QoL) [54], Raglio et al. (2017) (M, QoL) [11], Segura et al. (2024) (CF, E, M) [32] | Stroke | →* | → | ↑* | - | ↑* |

| Impellizzeri et al. (2024) (CF) [49] | Parkinson’s disease | ↑* | - | - | - | - |

| Siponkoski et al. (2020) (CF) [50] | Traumatic brain injury | ↑* | - | - | - | - |

| van Bruggen-Rufi et al. (2017) (CF, B) [53] | Huntington’s disease | ↓ | - | - | → | - |

| Note. Includes 7/10 studies, excluded Haire et al. (2021) [52] due to the lack of comparator group not containing music therapy, and Impellizzeri et al. (2020 [79] and Lee et al. (2024) [51] due to only reliably reporting within-group. ↑ = music therapy significantly improved the outcome, over the control group; → = no significant effect of music therapy was found for the outcome, over the control group; ↓ = the control group significantly improved the outcome, over music therapy; *= the direction of effect is not based on one standardised measure, but a number of subtests where a proportion showed significant results. | ||||||

Appendix D

| Randomisation process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of outcome | Selection of the reported result | Overall risk of bias | |

| Chou et al. (2024) [81] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns (assessor blinded to participant allocation, self-report measures used) | Low risk | High risk |

| Haire et al. (2021) [52] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns (assessor blinded to participant allocation, self-report measures used) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Impellizzeri et al. (2020) [79] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns (assessor blinded to participant allocation, used self-report measures) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Impellizzeri et al. (2024) [49] | Low risk (randomised, differences in Stroop test at baseline, likely due to chance) | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns (assessor blinded to participant allocation, uses one self-report measure) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Lee et al. (2024) [51] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk | Low risk |

Some concerns (assessors not blinded to allocation and familiar with participants, potential for bias) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Poćwierz-Marciniak & Bidzan (2017) [54] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk |

Low risk |

Some concerns (assessor not blinded to allocation as they delivered the intervention, used self-report measures) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Raglio et al. (2017) [11] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk |

Low risk |

Some concerns (assessors blinded to participant allocation, used self-report measures) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Segura et al. (2024) | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk (intention-to-treat analysis carried out) | Low risk | Some concerns (assessors blinded to participant allocation, used self-report measures) |

Low risk | Some concerns |

| Siponkoski et al. (2020) [50] | Low risk (randomised, only group difference was deviation on cause of injury, but not considered clinically important and attributed to chance) | Low risk (intention-to-treat analysis carried out) | Low risk | Low risk (assessors blinded to participant allocation) | Low risk | Low risk |

| Van Bruggen-Rufi et al. (2017) [53] | Low risk (randomised, no group differences at baseline) | Low risk (intention-to-treat analysis considered) | Low risk (unclear which groups the participants were allocated to that withdrew due to lack of motivation) | Some concerns (some assessors blinded to participant allocation, not the nursing staff assessing behaviour, observer-reported assessment requiring judgement) | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Note. Low risk = the study is low risk of bias for all domains. Some concerns = the study raises some concerns in at least one domain, but not at high risk for any domain. High risk = the study is at high risk of bias in at least one domain, or the study has some concerns for multiple domains. | ||||||

References

- Devlin, K., Alshaikh, J. T., & Pantelyat, A. (2019). Music therapy and music-based interventions for movement disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 19(11), 83-95. [CrossRef]

- De Witte, M., Pinho, A. D. S., Stams, G. J., Moonen, X., Bos, A. E., & Van Hooren, S. (2022). Music therapy for stress reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev, 16(1), 134-159. [CrossRef]

- Hurkmans, J., de Bruijn, M., Boonstra, A. M., Jonkers, R., Bastiaanse, R., Arendzen, H., & Reinders-Messelink, H. A. (2012). Music in the treatment of neurological language and speech disorders: A systematic review. Aphasiology, 26(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S. (2009). A neuroscientific perspective on music therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci, 1169(1), 374-384. [CrossRef]

- Leins, A. K., & Spintge, R. (2008). Music therapy in medical and neurological rehabilitation settings. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, & M. Thaut (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology (pp. 526-535). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Robb, S. L., Hanson-Abromeit, D., May, L., Hernandez-Ruiz, E., Allison, M., Beloat, A., Daughtery, S., Kurtz, R., Ott, A., Oyedele, O. O., Polasik, S., Rager, A., Rifkin, J., & Wolf, E. (2018). Reporting quality of music intervention research in healthcare: A systematic review. Complement Ther Med,38, 24-41. [CrossRef]

- Grau-Sánchez, J., Jamey, K., Paraskevopoulos, E., Dalla Bella, S., Gold, C., Schlaug, G., Belleville, S., Rodríguez-Fornells, A., Hackney, M. E., & Särkämö, T. (2022). Putting music to trial: Consensus on key methodological challenges investigating music-based rehabilitation. Ann NY Acad Sci, 1518(1), 12-24. [CrossRef]

- Howlett, J. R., Nelson, L. D., & Stein, M. B. (2022). Mental health consequences of traumatic brain injury. Biol Psychiatry, 91(5), 413-420. [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, T. (2018). Evaluating music therapy in adult mental health services: Tuning into service user perspectives. Nord J Music Ther, 27(1), 28-43. [CrossRef]

- Moore, K. S. (2013). A systematic review on the neural effects of music on emotion regulation: Implications for music therapy practice. J Music Ther 50(3), 198-242. [CrossRef]

- Raglio, A., Zaliani, A., Baiardi, P., Bossi, D., Sguazzin, C., Capodaglio, E., Imbriani, C., Gontero, G., & Imbriani, M. (2017). Active music therapy approach for stroke patients in the post-acute rehabilitation. Neurol Sci, 38(5), 893-897. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N., Iyemere, K., Underwood, B. R., & Odell-Miller, H. (2023). Investigating the impact of music therapy on two in-patient psychiatric wards for people living with dementia: retrospective observational study. BJPsych Open, 9(2), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L., Horton, L., Kunzmann, K., Sahakian, B. J., Newcombe, V. F., Stamatakis, E. A., von Steinbuechel, N., Cunitz, K., Covic, A., Maas, A., Van Praag, D., & Menon, D. (2021). Understanding the relationship between cognitive performance and function in daily life after traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 92(4), 407-417. [CrossRef]

- Brancatisano, O., Baird, A., & Thompson, W. F. (2020). Why is music therapeutic for neurological disorders? The Therapeutic Music Capacities Model. Neurosci Bobehav Riv, 112(1), 600-615. [CrossRef]

- Leins, A. K., & Spintge, R. (2008). Music therapy in medical and neurological rehabilitation settings. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, & M. Thaut (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology (pp. 526-535). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Machado Sotomayor, M.J., Arufe-Giráldez, V., Ruíz-Rico, G., & Navarro-Patón, R. (2021). Music therapy and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review from 2015–2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(21), 11618 -11633. [CrossRef]

- Magee, W. L. (2019). Why include music therapy in a neuro-rehabilitation team? ACNR 19(2), 10-12. [CrossRef]

- Mercier, L. J., Langelier, D. M., Buchanan, J., Robinson, S., & Plamondon, S. (2024). Development and integration of a music therapy program in the neurologic inpatient setting: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil, 47(7), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Murtaugh, B., Morrissey, A. M., Fager, S., Knight, H. E., Rushing, J., & Weaver, J. (2024). Music, occupational, physical, and speech therapy interventions for patients in disorders of consciousness: An umbrella review. NeuroRehabilitation, 54(1), 109-127. [CrossRef]

- Thaut, M. H. (2014). Assessment and the transformational design model (TDM). In M. Thaut & V. Hoemberg (Eds.), Handbook of neurologic music therapy (pp. 60-68). Oxford University Press.

- Breuer, E., Lee, L., De Silva, M., & Lund, C. (2015). Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci, 11(63), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- de l'Etoile, S. K. (2014). Processes of music therapy: Clinical and scientific rationales and models. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, & M. H. Thaut (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music psychology (2nd edition) (pp. 805-818). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M., McKenzie, J. E., Sowden, A., Katikireddi, S. V., Brennan, S. E., Ellis, S., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Ryan, R., Shepperd, S., Thomas, J., Welch, V., & Thomson, H. (2020). Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ, 368(6890), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version. Lancaster University. [CrossRef]

- Altenmüller, E., & Schlaug, G. (2013). Neurologic music therapy: The beneficial effects of music making on neurorehabilitation. Acoust Sci Technol, 34(1), 5-12. [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.L., Li, W.T.V., Laher, I. and Wong, R.Y., 2020. Effects of music therapy on patients with dementia—A systematic review. Geriatrics, 5(4), 62-75. [CrossRef]

- Lanb, L. C. L. S. H., Lanc, S. J., & Hsiehe, Y. P. (2024). Effectiveness of the Music Therapy in Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 54(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Morales, C., Calero, R., Moreno-Morales, P. and Pintado, C., 2020. Music therapy in the treatment of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med, 7(160), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2019). Dementia quality standard [NICE Guideline Quality Standard No. 184]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs184.

- NHS England (2014). NHS Standard Contract for Specialised Rehabilitation for Patients with Highly Complex Needs (All Ages). https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/d02-rehab-pat-high-needs-0414.pdf.

- Thompson, N., & Odell-Miller, H. (2024). An audit of music therapy in acute National Health Service (NHS) settings for people with dementia in the UK and adaptations made due to COVID-19. Approaches Music Ther, 16(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Segura, E., Grau-Sánchez, J., Cerda-Company, X., Porto, M. F., De la Cruz-Puebla, M., Sanchez-Pinsach, D., Cerquides, J., Duarte, E., Palumbo, A., Turry, A., Raghavan, P., Särkämö, T, Münte, T. F., Arcos, J. L., & Rodríguez-Fornells, A. (2024). Enriched music-supported therapy for individuals with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurol 271(10), 6606-6617. [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, L., Bieleninik, Ł., Brondino, N., Chen, X. J., & Gold, C. (2018). The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health, 22(9), 1103-1112. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C., Fernández-Company, J. F., Pita, M. F., & Garcia-Rodriguez, M. (2022). Music therapy for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: an overview. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 27(3), 895-910. [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M., De Angelis, S., Mastrogiacomo, S., Princi, A. A., Ciancarelli, I., Frizziero, A., Iosa, M., Paolucci, S., & Morone, G. (2021). Music-based techniques and related devices in neurorehabilitation: a scoping review. Expert Rev Med. Devices, 18(8), 733-749. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R., Florez-Perdomo, W. A., Shrivatava, A., Chouksey, P., Raj, S., Moscote-Salazar, L. R., Rahman, M. M., Sutar, R., & Agrawal, A. (2021). Role of music therapy in traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg, 146, 197-204. [CrossRef]

- Odell-Miller, H. (2016). The role, function and identity of music therapists in the 21st century, including new research and thinking from a UK perspective. BJMT, 30(1), 5-12. [CrossRef]

- Carr, C. E., Tsiris, G., & Swijghuisen Reigersberg, M. (2017). Understanding the present, re-visioning the future: An initial mapping of music therapists in the United Kingdom. BJMT, 31(2), 68-85. [CrossRef]

- Wood, J., Sandford, S., & Bailey, E. (2016). ‘The whole is greater’. Developing music therapy services in the National Health Service: A case study revisited. BJMT, 30(1), 36-46. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2023). Stroke rehabilitation in adults [NICE Guideline No. 236]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng236/chapter/Recommendations.

- Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials—the gold standard for effectiveness research. BJOG, 125(13), 1716. [CrossRef]

- García-Navarro E.B., Buzón-Pérez A., Cabillas-Romero M. Effect of Music Therapy as a Non-Pharmacological Measure Applied to Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A Systematic Review. Nurs Rep, 2022;12(4):775–790. [CrossRef]

- Bleibel, M., El Cheikh, A., Sadier, N.S. et al. The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alz Res Therapy 15, 65 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Falzon, L., Davidson, K. W., & Bruns, D. (2010). Evidence searching for evidence-based psychology practice. Prof Psychol Res Pr, 41(6), 550-557. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.) (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, E. C., Chen, Y. J., Wu, W. C., Chou, C. X., & Yu, M. Y. (2022). Psychometric comparisons of three depression measures for patients with stroke. AJOT, 76(4), 1-7.

- Nishikawa-Pacher, A. (2022). Research questions with PICO: a universal mnemonic. Publications, 10(3), 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club, 123(3), 12-13. [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, F., Maggio, M. G., De Pasquale, P., Bonanno, M., Bonanno, L., De Luca, R., Paladina, G., Alibrandi, A., Milardi, D., Thaut, M., Hurt, C., Quartarone, A., & Calabrò, R. S. (2024). Coupling neurologic music therapy with immersive virtual reality to improve executive functions in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A Quasi-Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Park Relat Disord, 11, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Siponkoski, S. T., Martínez-Molina, N., Kuusela, L., Laitinen, S., Holma, M., Ahlfors, M.,Jordan-Kilkki, P., Ala-Kauhaluoma, K., Melkas, S., Pekkola, J., Rodriguez-Fornells, A., Laine, M., Ylinen, A., Rantanen, P., Koskinen, S., Lipsanen, J., & Särkämö, T. (2020). Music therapy enhances executive functions and prefrontal structural neuroplasticity after traumatic brain injury: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Neurotrauma, 37(4), 618-634.

- Lee, S. J., Dvorak, A. L., & Manternach, J. N. (2024). Therapeutic Singing and Semi-Occluded Vocal Tract Exercises for Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Single Session Intervention. J Music Ther, 61(2), 132-167. [CrossRef]

- Haire, C. M., Vuong, V., Tremblay, L., Patterson, K. K., Chen, J. L., & Thaut, M. H. (2021). Effects of therapeutic instrumental music performance and motor imagery on chronic post-stroke cognition and affect: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation, 48(2), 195-208. [CrossRef]

- van Bruggen-Rufi, M. C., Vink, A. C., Wolterbeek, R., Achterberg, W. P., & Roos, R. A. (2017). The effect of music therapy in patients with Huntington’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Huntington's Dis, 6(1), 63-72. [CrossRef]

- Poćwierz-Marciniak, I., & Bidzan, M. (2017). The influence of music therapy on quality of life after a stroke. Health Psychol Rep, 5(2), 173-185. [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R., & Bradshaw, T. (2014). Music therapy for service users with dementia: A critical review of the literature. J Psychiatr Men. Health Nurs, 21(10), 879-888. [CrossRef]

- Hoffecker, L. (2020). Grey Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews in the Health Sciences. Ser Lib 79(3–4), 252–260. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J., Sadeghieh, T., & Adeli, K. (2014). Peer review in scientific publications: benefits, critiques, & a survival guide. J Int Fed Clin Chem Lab Med, 25(3), 227-243.

- Barrington, A. (2015). Perspectives on the development of the music therapy profession in the UK. Approaches, 7(1), 118-122. [CrossRef]

- British Association for Music Therapy. (2020). Guidelines on professional titles for music therapists. British Association for Music Therapy. https://www.bamt.org/music-therapy/what-is-a-music-therapist/guide-to-professional-practice.

- Chandler, G., & Maclean, E. (2024). “There has probably never been a more important time to be a music therapist”: Exploring how three music therapy practitioners working in adult mental health settings in the UK experienced the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Approaches. [CrossRef]

- Helbach, J., Pieper, D., Mathes, T., Rombey, T., Zeeb, H., Allers, K., & Hoffmann, F. (2022). Restrictions and their reporting in systematic reviews of effectiveness: an observational study. BMC Med Res Methodol, 22(230), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H., Tsutani, K., Yamada, M., Park, H., Okuizumi, H., Tsuruoka, K., Honda, T., Okada, S., Park, S., Kitayuguchi, J., Abe, T., Handa, S., Oshio, T., & Mutoh, Y. (2014). Effectiveness of music therapy: a summary of systematic reviews based on randomized controlled trials of music interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence, 8, 727-754. [CrossRef]

- Pieper, D., & Puljak, L. (2021). Language restrictions in systematic reviews should not be imposed in the search strategy but in the eligibility criteria if necessary. J Clin Epidemiol 132, 146-147. [CrossRef]

- Bond, C., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M., Chan, C., Eddy, S., Hopewell, S., Mellor, K., Thabane, L., & Eldridge, S. (2023). Pilot and feasibility studies: extending the conceptual framework. PFS, 9(1), 24-33.

- Arain, M., Campbell, M. J., Cooper, C. L., & Lancaster, G. A. (2010). What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol,, 10(67), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Benarous, H., Benarous, X., Vonthron, F., & Cohen, D. (2021). Music therapy for children with autistic spectrum disorder and/or other neurodevelopmental disorders: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry, 12(643234), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C. S., Wilson, J. R., Nori, S., Kotter, M., Druschel, C., Curt, A., & Fehlings, M. G. (2017). Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 3(1), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Vist, G. E., Kunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ, 336(7650), 924-926. [CrossRef]

- Matthew J. Page, Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, Roger Chou, Julie Glanville, Jeremy M. Grimshaw, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, Manoj M. Lalu, Tianjing Li, Elizabeth W. Loder, Evan Mayo-Wilson, Steve McDonald, Luke A. McGuinness, Lesley A. Stewart, James Thomas, Andrea C. Tricco, Vivian A. Welch, Penny Whiting, David Moher. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., & Sterne, J. A. (2019). Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (pp. 205-228). The Cochrane Collaboration. [CrossRef]

- Nejadghaderi, S. A., Balibegloo, M., & Rezaei, N. (2024). The Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool 2 (RoB 2) versus the original RoB: A perspective on the pros and cons. Health Sci Rep, 7(6), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Sterne J. A. C., Savović J., Page M. J., Elbers R. G., Blencowe N. S., Boutron I., Cates C. J., Cheng H-Y., Corbett M. S., Eldridge S. M., Hernán M. A., Hopewell S., Hróbjartsson A., Junqueira D. R., Jüni P., Kirkham J. J., Lasserson T., Li T., McAleenan A., ... Higgins J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366(l4898), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H. J., & Thomas, S. (2013). The effect direction plot: visual display of non-standardised effects across multiple outcome domains. Res Synth Methods, 4(1), 95-101. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychol Bull, 112(1), 1155-1159. [CrossRef]

- Bauchner, H., Golub, R. M., & Fontanarosa, P. B. (2019). Reporting and interpretation of randomized clinical trials. JAMA, 322(8), 732-735. [CrossRef]

- Bhide, A., Shah, P. S., & Acharya, G. (2018). A simplified guide to randomized controlled trials. AOGS, 97(4), 380-387. [CrossRef]

- Murad, M. H., Mustafa, R. A., Schünemann, H. J., Sultan, S., & Santesso, N. (2017). Rating the certainty in evidence in the absence of a single estimate of effect. BMJ EBM, 22(3), 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H. J., Higgins, J. P., Vist, G. E., Glasziou, P., Akl, E. A., Skoetz, N., Guyatt, G. H. (2019). Completing ‘summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (pp. 375-402). The Cochrane Collaboration. [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, F., Maggio, M. G., De Pasquale, P., Bonanno, M., Bonanno, L., De Luca, R., Paladina, G., Alibrandi, A., Milardi, D., Thaut, M., Hurt, C., Quartarone, A., & Calabrò, R. S. (2024). Coupling neurologic music therapy with immersive virtual reality to improve executive functions in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A Quasi-Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Park Relat Disord, 11, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Estellat, C., Torgerson, D. J., & Ravaud, P. (2009). How to perform a critical analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 23(2), 291-303. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C. H., Chen, P. C., Huang, Y. C., Yang, T. H., Wang, L. Y., Chen, I. H., Lee, H. J., & Lee, Y. Y. (2024). Neurological music therapy for poststroke depression, activity of daily living and cognitive function: A pilot randomized controlled study. Nord. J Music Ther,33(3), 226-237. [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, J. R., Linting, M., Rippe, R. C., & Van Der Voort, A. (2020). Rebutting existing misconceptions about multiple imputation as a method for handling missing data. J Pers Assess102(3), 297-308. [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw., 45(3), 1-67. [CrossRef]

- Austin, P. C., White, I. R., Lee, D. S., & van Buuren, S. (2021). Missing data in clinical research: a tutorial on multiple imputation. Can J Cardiol, 37(9),1322-1331. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E., Arce, C., Torrado, J., Garrido, J., De Francisco, C., & Arce, I. (2010). Factor structure and invariance of the POMS mood state questionnaire in Spanish. Span J Psychol, 13(1), 444-452. [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I., Dutton, S., Ravaud, P., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA, 303(20), 2058-2064. [CrossRef]

- Carter, E. C., Schönbrodt, F. D., Gervais, W. M., & Hilgard, J. (2019). Correcting for bias in psychology: A comparison of meta-analytic methods. Adv Meth Pract Psychol Sci, 2(2), 115-144. [CrossRef]

- van Bruggen-Rufi, M., Vink, A., Achterberg, W., & Roos, R. (2016). Music therapy in Huntington’s disease: a protocol for a multi-center randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol, 4(38), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, H. C., Mintz, J., Noda, A., Tinklenberg, J., & Yesavage, J. A. (2006). Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 63(5), 484-489. [CrossRef]

- Beato, M. (2022). Recommendations for the design of randomized controlled trials in strength and conditioning. Common design and data interpretation. Front Sports Act Living, 4(981836), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M. A., Muzzatti, B., Bidoli, E., Flaiban, C., Bomben, F., Piccinin, M., Gipponi, K. M., Mariutti, G., Busato, S., & Mella, S. (2020). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) accuracy in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer, 28(8), 3921 -3926. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, E. C., Chen, Y. J., Wu, W. C., Chou, C. X., & Yu, M. Y. (2022). Psychometric comparisons of three depression measures for patients with stroke. AJOT 76(4), 1-7.

- Costantini, M., Musso, M., Viterbori, P., Bonci, F., Del Mastro, L., Garrone, O., M Venturini M., & Morasso, G. (1999) Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer 7, 121–127 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Annell, S., Sjöberg, A., & Sverke, M. (2014). Use and interpretation of test scores from limited cognitive test batteries: how g+ Gc can equal g. Scand J Psychol, 55(5), 399-408. [CrossRef]

- Essers, B., Veerbeek, J. M., Luft, A. R., & Verheyden, G. (2024). The feasibility of the adapted H-GRASP program for perceived and actual daily-life upper limb activity in the chronic phase post-stroke. Disabil Rehabil, 46(24), 5815-5828. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, L. A., Eng, J. J., & Chan, M. (2017). H-GRASP: the feasibility of an upper limb home exercise program monitored by phone for individuals post stroke. Disabil Rehabil, 39(9), 874-882. [CrossRef]

- Russell, E. W., Russell, S. L., & Hill, B. D. (2005). The fundamental psychometric status of neuropsychological batteries. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 20(6), 785-794. [CrossRef]

- Casaletto, K. B., & Heaton, R. K. (2017). Neuropsychological assessment: Past and future. JNS, 23(9-10), 778-790. [CrossRef]

- Thaut, M., & Hoemberg, V. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of neurologic music therapy. Oxford University Press.

- von Hippel, P. T. (2015). The heterogeneity statistic I 2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Research Methodol, 15(35), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Königs, M., Beurskens, E. A., Snoep, L., Scherder, E. J., & Oosterlaan, J. (2018). Effects of timing and intensity of neurorehabilitation on functional outcome after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 99(6), 1149-1159. [CrossRef]

- Kern, P., & Tague, D. B. (2017). Music therapy practice status and trends worldwide: An international survey study. J Music Ther, 54(3), 255-286. [CrossRef]

- Dobran, S. A., & Gherman, A. (2024). Neurorehabilitation across continents: the WFNR -EFNR regional meeting in conjunction with the 19th congress of the society for the study of neuroprotection and neuroplasticity and the 19th international summer school of neurology in Baku, Azerbaijan. J Med Life, 17(9), 825-829. [CrossRef]

- Nasios, G., Messinis, L., Dardiotis, E., & Sgantzos, M. (2023). Neurorehabilitation: Looking Back and Moving Forward. Healthcare, 11(10), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Fernainy, P., Cohen, A. A., Murray, E., Losina, E., Lamontagne, F., & Sourial, N. (2024). Rethinking the pros and cons of randomized controlled trials and observational studies in the era of big data and advanced methods: a panel discussion. BMC Proc, 18(2), 1-7. [CrossRef]

| Outcome variable | Definition for included studies |

| Cognitive function | Executive functions, memory, visuospatial abilities, attention, communication [49. 50] |

| Mood | Depression, anxiety, anger, vigour, fatigue (11, 32, 51] |

| Emotion | Self-perceived emotional well-being, emotional awareness of self and others, sharing of emotions [32,49] |

| Self-efficacy | Sense of competence in managing new and challenging situations [52] |

| Behaviour | Communication and expressive skills, mental rigidity, aggression [53] |

| Affect | Valence, arousal, dominance [52] |

| Quality of life | An individual’s perception of their physical and mental state, and social position [54] |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| a) Peer-reviewed original empirical RCTs | a) Studies with dementia or spinal cord injury |

| b) Adults with neurological conditions | b) Studies with neurodevelopmental conditions |

| c) MT delivered by a board-certified music therapist or a therapist skilled in delivering specific evidence-based NMT | c) Study designs such as review, protocol, or feasibility studies |

| d) Published between 1st January 2015-31st January 2025, | d) Studies with qualitative or mixed methods data |

| e) Published in the English language | e) Studies containing non-psychological outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).