I. Introduction

In the beginning, there is unity, an ancient Chinese concept of Tai-Chi [

1], or the Supreme Ultimate Unity, which dates back approximately five thousand years, embodies the idea of a primordial wholeness that gives rise to all dualities—Yin and Yang [

2], space and time, matter and energy. This notion of emergence from unity resonates deeply with the foundations of mathematics and physics, where a single scalar identity element, commonly denoted as 1 or e

0, seeds the entire structure of numbers and algebras. The dualism of Yin-Yang has been adopted by G. W. Leibniz [

3], one of the founding fathers of calculus and symbolic logic, who was deeply influenced by this Chinese philosophy. Dualism [

4] plays an important role in many areas, including mathematics [

5,

6], physics [

7,

8], electrical and computer science [

9,

10], bioengineering and gene sequencing [

11,

12], philosophy [

13,

14], western and eastern religions [

15,

16], human sciences and literature [

17,

18].

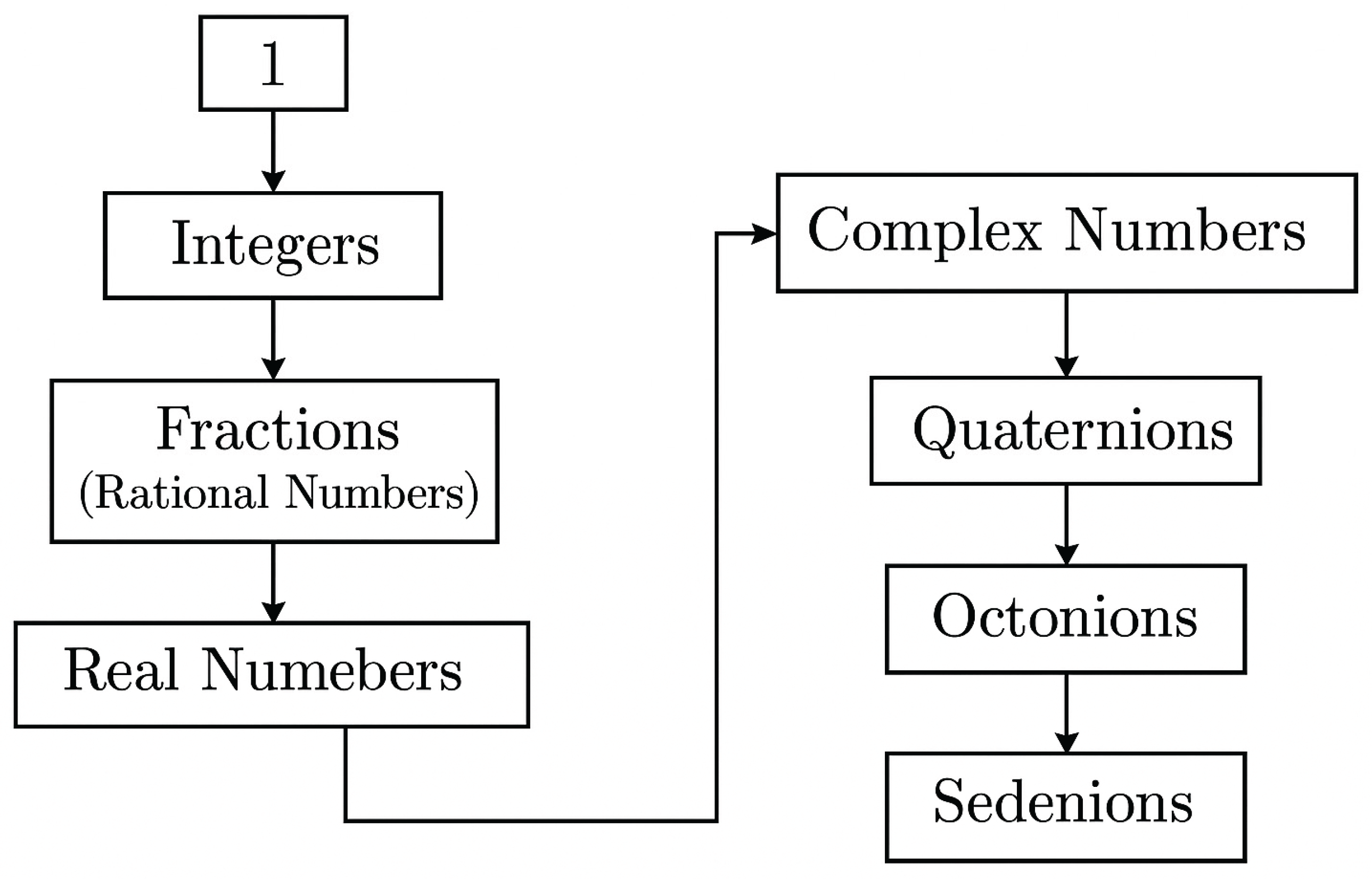

Modern mathematics has formalized this emergence through the Cayley–Dickson construction scheme [

19], a recursive doubling process that expands the real numbers into complex numbers, and hypercomplex numbers, such as quaternions [

20,

21,

22], octonions [

23,

24,

25], and sedenions [

26,

27]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, starting from the unity number 1 as the first natural number, one expands to greater natural numbers, and then all integers, including zero and the negative integers, to the fractional numbers between integers as rational numbers, to irrational numbers, then to real numbers. With paired real numbers, one constructs complex numbers.

The birth of modern hypercomplex number systems was first introduced by Irish mathematician Hamilton [

28], whose pioneering invention of quaternions in mid. The 1850s were later extended by Cayley [

29] to octonions.

Through the Cayley-Dickson scheme, one can construct higher hypercomplex numbers, layer by layer, from complex numbers to quaternions, octonions, and finally sedenions.

Here we show the mathematical structures of hypercomplex number systems. They are extended, via the Cayley-Dickson construction scheme, layer upon layer, from 2D complex algebra to a higher-dimensional hypercomplex algebra.

Table 1.

Cayley-Dickson’s hypercomplex-number construction scheme.

Table 1.

Cayley-Dickson’s hypercomplex-number construction scheme.

| Complex |

C = (R1, R2)

|

(R1, R2)(R3, R4) = (R1R3-R4R2, R4R1+R2R3) |

| Quaternion |

Q = (c1, c2) |

(c1, c2)(c3, c4) = (c1c3-c4*c2, c4c1+c2c3*) |

| Octonion |

O =(q1, q2) |

(q1, q2)(q3, q4) = (q1q3-q4*q2, q4q+q2q3*) |

| Sedenion |

S =(O1, O2) |

(O1, O2)(O3, O4) = (O1O3-O4*O2, O4O+O2O3*) |

We present

Table 2 to summarize the algebraic properties—commutativity, associativity, and division—of the number systems that emerge from the Cayley–Dickson process. At higher layers of the hypercomplex algebra, some well-known multiplication rules, such as commutability, associability, and divisibility, are no longer valid [

26].

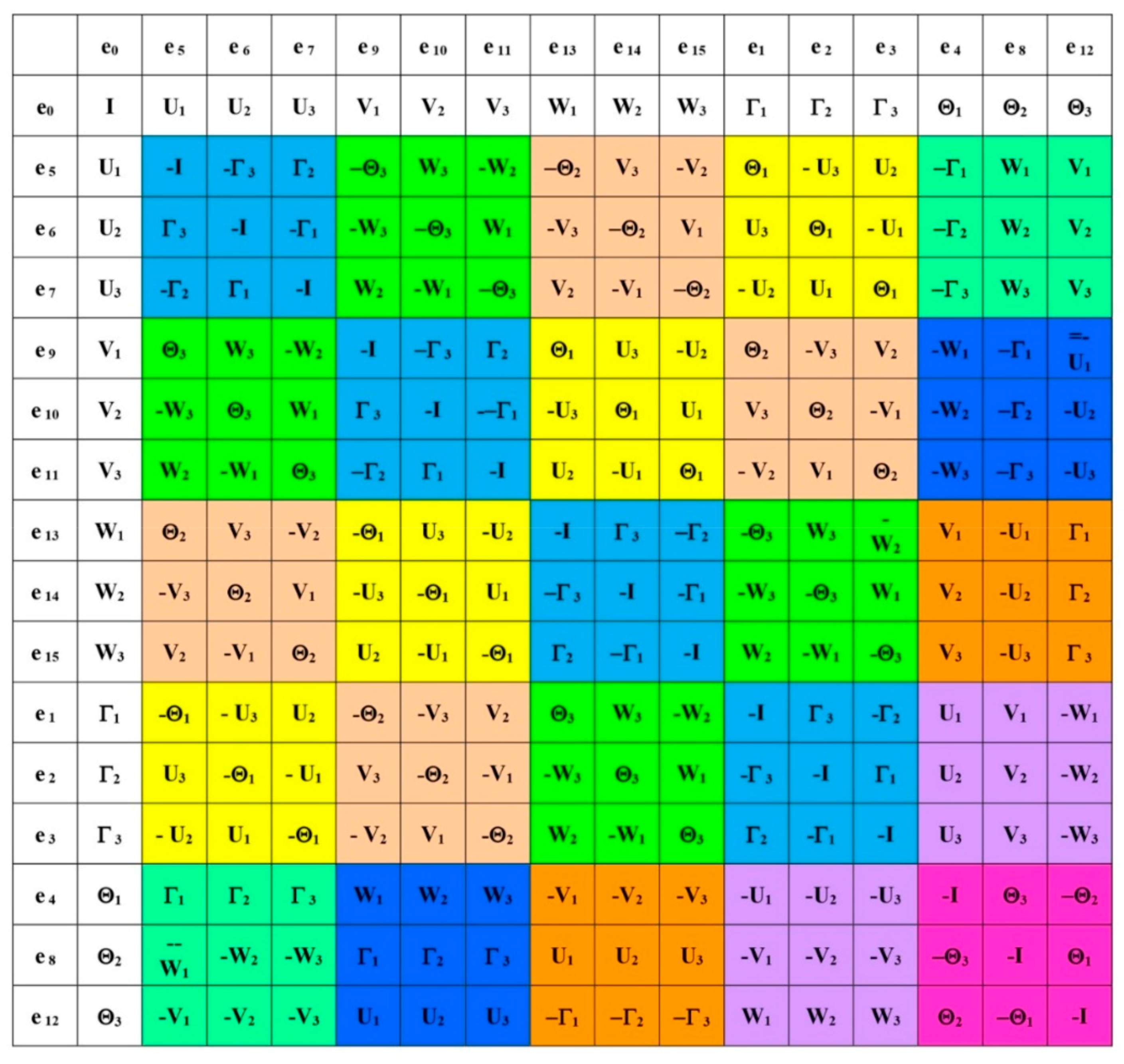

Each extension introduces new mathematical features—non-commutativity, non-associativity, and increasing dimensionality—that mirror the complexity of the physical world. Notably, each stage of this hierarchy also brings new opportunities for encoding physical symmetries, internal degrees of freedom, and quantum characteristics such as spin and charge. The multiplication table of 16D sedenion algebra is shown in

Figure 2, and it contains the multiplication tables for complex numbers [

12], quaternions, and octonions as subalgebras.

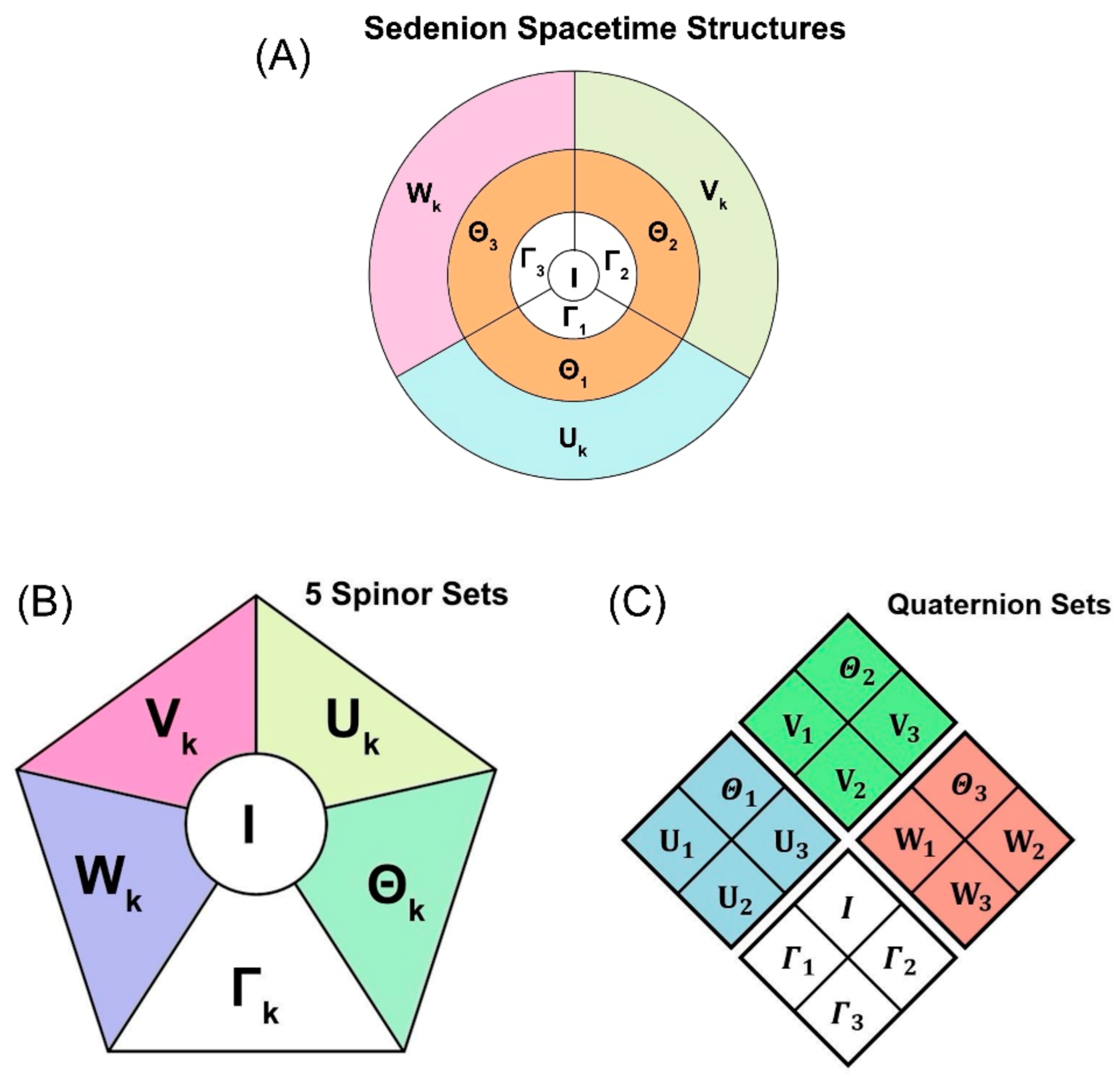

The sedenion algebra contains rich internal symmetry properties. This sedenion algebra contains three sets of octonion algebra with a common quaternion root. One can divide these basis elements into four quartets and five spinor triplets., as illustrated in

Figure 3. These internal symmetries play crucial roles in dictating the physical and mathematical properties of fundamental particle physics. In our previous work [

30], we have shown the sedenion algebra can be linked to SU(5) [

31], which contains SU(3)xSU(2)xU(1) symmetry, the basis of the Standard Model [

32,

33].

This paper embarks on a journey that connects the philosophical depth of Tai-Chi with the algebraic machinery underlying modern physics. We propose that the unity represented by e0 is more than a mathematical convenience—it is the generative essence of both mathematical reality and physical laws. By tracing the layered evolution from unity to the sedenions, we uncover a correspondence between hypercomplex algebra and the hierarchical structure of elementary particles and interactions described in the Standard Model.

Our exploration is not merely technical; it is conceptual. We aim to present an elegant narrative in which each mathematical layer aligns with a physical phenomenon, demonstrating that the path from Tai-Chi to sedenions is not only mathematically natural but also physically inevitable.

II. From Unity to Hypercomplex Algebras

The scalar unity element, denoted as e0, serves as the origin of all algebraic constructions. Starting from this singular element, mathematics builds progressively richer number systems that mirror increasing structural complexity:

1). Real Numbers (ℝ) Begin with e0 as the identity, forming a 1D space.

2). Complex Numbers (ℂ): Introduce one imaginary unit i (where i2 = -1), giving ℂ = ℝ ⊕ ℝ·i.

Complex numbers are employed in classical Newtonian mechanics, electronics, and non-relativistic quantum mechanics for the description of periodic phenomena through Euler’s famous identity relation of exp(i p) = -1.

3). Quaternions (ℍ): Add three imaginary units e1, e2, e3 such that:

- e12 = e22 = e32 = -1

- e1e2 = e3, e2e3 = e1, e3e1 = e2 (with non-commutative multiplication)

Quanternios are employed in the description of Maxwell’s EM field equations, Minkowski space, special relativity, SU(2) spinors, Dirac equation, etc.

4). Octonions (𝕆): Extend with four more units e4 through e7, forming a non-associative algebra. Their multiplication follows a specific Fano plane structure that captures seven triplet relations.

Octonions are employed in the description of SU(3), generalized Dirac equation, etc.

5). Sedenions (𝕊): Add eight more imaginary units (e8 through e15) via Cayley–Dickson construction. Though they lose the division property, they retain 16-dimensional richness with many zero divisors.

Sedenions can be used to describe particle physics beyond the Standard Model.

Each algebra doubles the dimensionality of the previous:

ℝ (1D) → ℂ (2D) → ℍ (4D) → 𝕆 (8D) → 𝕊 (16D).

This structured growth is not arbitrary—it correlates deeply with physical symmetries and particle classifications in quantum field theory.

In particular:

- The quaternionic triplet (e1, e2, e3) aligns naturally with 3D space and angular momentum operators.

- The octonionic basis (e1 to e7) supports internal symmetries such as SU(2) and SU(3), with their multiplication structure encoding fermionic creation-annihilation operators and gluon generators.

- The sedenions open a mathematical avenue to describe the full spectrum of particle generations, color charge extensions, and possibly new exotic interactions beyond the Standard Model.

III. The Yin-Yang Duality and SU(n) Symmetries

The ancient Chinese framework of Yin and Yang describes the world through dynamic duality: light and dark, active and passive, positive and negative. This philosophy mirrors the structure of modern algebra and quantum field theory.

In algebra, dualities manifest through the interplay of elements and their negatives, particles and antiparticles, spinors and conjugates. This binary structure is foundational in defining symmetry groups, particularly unitary symmetries such as SU(n).

The unitary groups SU(2) and SU(3) play pivotal roles in the Standard Model:

- SU(2) governs the weak interaction and is generated by the Pauli matrices, analogous to quaternionic units (e1, e2, e3).

- SU(3) governs the strong interaction (Quantum Chromodynamics [

39]), with its eight Gell-Mann matrices expressible through combinations of octonionic elements and their complexified forms.

Just as Yin and Yang are mutually defining yet complementary, the left-handed and right-handed components of spinors transform differently under SU(2), giving rise to chirality and parity violation in weak interactions. The pairing of octonionic elements—such as e1 + i·e2 and their complex conjugates—serve as natural fermionic operators that generate SU(3) color charges.

Thus, the Taoist duality encapsulated by Yin-Yang is not metaphorical; it reflects a deeper algebraic and physical truth. The harmony of opposites in ancient thought translates into gauge symmetry and group structure in modern physics, with the mathematics of octonions forming a unifying bridge.

IV. Microcausal Lattice Spacetime and Internal Symmetries

In contrast to the smooth, continuous manifold assumed in traditional relativity, the microcausal lattice spacetime (LST) hypothesis [

40] posits a discrete, quantized structure of spacetime at the smallest scales. This discrete lattice does not violate Lorentz invariance in the continuum limit but introduces a physically meaningful cutoff at the Planck scale, naturally resolving ultraviolet divergences [

40].

This LST framework supports a geometrically richer picture of spacetime. The standard four-dimensional spacetime coordinates (t, x, y, z) are associated with the quaternionic units (e0, e1, e2, e3). However, microcausal constraints introduce internal degrees of freedom represented by additional imaginary units: e4, e5, e6, e7 of the octonions. These internal components account for:

- e4: Associated with intrinsic mass and time-asymmetric effects, such as weak decay.

- e5, e6, e7: Represent dynamic internal configurations and interactions that generate color charges and strong interactions.

In this way, LST explains the emergence of octonionic internal structure as a necessity of causality and locality at the fundamental level. It also provides a natural embedding of the SU(2) × U(1) and SU(3) gauge groups into the algebra of octonions. The external spacetime remains quaternionic, while the internal symmetries live in the octonionic extensions.

Consequently, particles that do not couple to internal octonionic coordinates—such as photons and leptons—emerge as singlets under isospin or color. In contrast, quarks and gluons arise from the mixing of external and internal octonionic directions, giving rise to SU(3) octets.

V. Physical Applications of Hypercomplex Algebras

Each layer of the hypercomplex number systems offers a distinct mathematical structure tailored to describe fundamental aspects of physical theory:

— Quaternions (e0, e1, e2, e3):

These form the algebraic backbone of spacetime in special relativity. The quaternionic imaginary units (e1, e2, e3) represent spatial components, while e0 corresponds to temporal evolution. Quaternions elegantly describe Lorentz transformations and rotational symmetries.

— Complexified Quaternions:

By combining quaternions with the complex unit i, we obtain a natural formulation for the electromagnetic field. Electric fields are represented by e1, e2, e3, while magnetic fields are encoded in i·e1, i·e2, i·e3. The complex phase between electric and magnetic fields captures the U(1) gauge symmetry of Maxwell’s equations. This explains why the photon is massless and preserves time-reversal symmetry.

— Octonions (e0 through e7):

The introduction of octonionic units enables the modeling of internal particle degrees of freedom:

- e4 introduces chirality and mass; its imaginary component i·e4 breaks time symmetry and is responsible for weak interactions.

- e5, e6, e7 allow for dynamic internal structures. When paired with e1, e2, e3, these combinations yield color charges and SU(3) gluons.

- Three fermionic operators—(e1 + i·e2), (e5 + i·e6), and (e3 + i·e7)—along with their conjugates, form the basis of creation and annihilation operators.

From these operators, one can construct:

- Eight SU(3) generators (gluons)

- Vector bosons W+, W−, and Z0 as an isospin triplet

- Photon as an isospin singlet

- Higgs boson as a spin and isospin singlet

— Sedenions (e0 through e15):

Extending octonions by another Cayley-Dickson step yields sedenions, with 16 basis elements. Though they lose division algebra properties, they retain sufficient structure to model higher-generation fermions. The additional imaginary units may correspond to internal orbital modes or generation indices. Leptons and quarks of the second and third generations can be constructed from these extended internal degrees of freedom, allowing natural mass hierarchy modeling.

Thus, each algebraic expansion corresponds to a new layer of physical meaning—from spacetime and gauge fields to particle generations and interactions.

VI. Particle Classification via Hypercomplex Operator Assignments

In this section, we concretely apply the hypercomplex operator formalism—built upon quaternions, octonions, and sedenions—to represent a set of elementary particles from the Standard Model. By associating different combinations of hypercomplex basis elements with the algebraic structure of known particles, we demonstrate a unified, non-perturbative method to model mass generation, spin, and internal quantum numbers. This framework replaces the traditional Higgs mechanism [

34], Yang-Mills gauge theory [

35], and the electroweak unification theory [

36,

37] with a deeper algebraic origin.

Fermionic Operators: We begin by defining three canonical fermionic creation operators and their conjugates (annihilation operators):

- ψ1 = (e1 + i·e2), ψ1† = (e1 − i·e2)

- ψ2 = (e5 + i·e6), ψ2† = (e5 − i·e6)

- ψ3 = (e3 + i·e7), ψ3† = (e3 − i·e7).

These three pairs of spinorial operators, when combined appropriately, give rise to the internal color symmetries in the electroweak unification theory [

35,

36,

37].

We introduce in

Table 3 the fermionic spinor operators that serve as the foundation for constructing particle states in our framework.

With the definition of the creation and annihilation operators, one can show the anti-commutation relations

With these fermionic creation and annihilation operators, one can construct in the next table eight Gell-Mann’s SU(3) generators for the eight gluonsWith these fermionic creation and annihilation operators, one can construct eight Gell-Mann’s SU(3) generators for the eight gluons as shown in our previous work on [

35].

We outline in

Table 4 how SU(3) gluons can be derived from bilinear combinations of the previously defined fermionic operators.

We now present in

Table 5 the bosonic particle assignments, based on their algebraic operator structure in the octonion framework.

With these octonionic operator assignments to these bosons, i.e., photon, W

+, W

−, and Z weak bosons as a quartet family, and the Higgs boson, one can derive the mass ratio and Weinberg’s angle within experimental accuracy. These studies will be reported elsewhere [

38]. Such a model for the electroweak interaction relies on octonionic gauge quantum field theory as an alternative to the conventional electroweak theory without an ad hoc Higgs mechanism hypothesis for the mass acquisition of these bosons. More detailed analysis will be published elsewhere.

VII. Summary and Outlook

In this paper, we have explored the profound mathematical and physical connection between the layered construction of hypercomplex algebras and the fundamental structure of matter. Starting from the unity element e0, we traced the Cayley-Dickson construction through real numbers, complex numbers, quaternions, octonions, and sedenions. Each layer not only increases in algebraic richness but also corresponds to a higher complexity in the physical world, providing a natural algebraic scaffolding for modeling particles and interactions.

Our approach replaces the conventional Higgs mechanism and gauge symmetry breaking paradigm of the Standard Model with a deeper algebraic framework rooted in non-associative division algebras and micro-causal lattice spacetime. The fermionic spinor structure derived from octonions generates the known gauge bosons and gluons while maintaining SU(3) × SU(2) × U(1) symmetry naturally.

Notably, the use of quaternionic and octonionic operators allowed us to assign meaningful operator representations for photons, W and Z bosons, gluons, and the Higgs scalar. Moreover, the inclusion of the non-Hermitian i e4 term enables us to account for the subtle mass discrepancies in the electroweak sector with high precision, all without the need for renormalization or ad hoc potential terms.

The primary purpose of this work is to elucidate the intrinsic connections between ancient philosophy and the mathematical idealism and to relate the abstract hypercomplex algebra to the iinternal symmetry that governs the quantum physics of elementary particles. Looking forward, the extension to sedenions provides a promising path to incorporate the full three generations of leptons and quarks. This direction could offer a powerful, elegant alternative to Grand Unified Theories, with testable predictions for particle mass ratios and mixing angles based on algebraic consistency. Furthermore, the role of e0 as a metaphysical unity may eventually contribute to a more holistic view of cosmology and quantum gravity, where physical fields, spacetime geometry, and mathematical logic are seamlessly unified.

Author Contributions

J. Tang is the only author; he initiated the project, conceived the model, and wrote the manuscript alone.

Funding

The author is a retired professor with no funding.

Data Availability Statement

This report contains analytical equation derivations without computer numerical simulations. All reasonable questions about the derivations can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest with anhone.

References

- Zhang, Dainian. Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy. Yale University Press, 2002.

- Cheng, Chung-Ying. Yin-Yang: A New Perspective on Chinese Thought. Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Leibniz, G.W. (1703). Letter to Joachim Bouvet on the Binary System and I Ching.

- Nagel, T. The View from Nowhere. Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Gell-Mann, M. The Quark and the Jaguar. Freeman, 1994.

- Penrose, R. The Road to Reality. Jonathan Cape, 2004.

- Dirac, P. A. M. Principles of Quantum Mechanics. Oxford, 1930.

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A. M. (1936). On Computable Numbers. Proc. London Math. Society, 42, 230–265. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D., Crick, F.H.C. (1953). A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature,, 171(4356): 737–738. [CrossRef]

- Your previous work—[Placeholder].

- Whitehead, A.N., Russell, B. Principia Mathematica. Cambridge University Press, 1910.

- Laozi. Dao De Jing. (Translation: D.C. Lau, Penguin Classics, 1963).

- Boyce, Mary. (1975). The Manichaean Religion: An Historical, Cultural, and Doctrinal Survey. In: A History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. 2.Brill Academic Publishers.

- Needham, Joseph. (1956). Science and Civilization in China, Volume 2: History of Scientific Thought.Cambridge University Press.

- Jung, C. G. Psychological Types. Princeton University Press, 1971.

- Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, 1949.

- Baez, J. C. (2002). The Octonions. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc., 39(2), 145–205. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W. R. (1844). On Quaternions. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 3, 1–16.

- Adler, S. L. Quaternionic Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Fields. Oxford, 1995.

- Conway, J. H., Smith, D. A. On Quaternions and Octonions. A K Peters, 2003.

- Wikipedia, Octonion—Wikipedia.

- Dixon, G.M. Division Algebras: Octonions, Quaternions, Complex Numbers and the Algebraic Design of Physics. Springer, 1994.

- Günaydin, M., Gürsey, F. (1973). Quark Structure and Octonions. J. Math. Phys.*, 14(11), 1651. [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia, Sedenion—Wikipedia.

- Moreno, E. F. (1999). Sedenions and the Algebra of Octonions. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras*, 9(1), 109–120.28.

- Hamilton, W. R. (1853). Lectures on Quaternions. Hodges and Smith.

- Cayley, A. (1845). On Certain Results Relating to Quaternions. Philosophical Magazine, 26, 210–213. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. & Tang, J. (2024) Sedenion Algebra Model as an Extension of the Standard Model and Its Link to SU(5), Symmetry, 16, 626. [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H., Glashow, S. L. (1974). Unity of All Elementary Particle Forces. Phys. Rev. Lett., 32, 438. [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, J.F.; Golowich, E.; Holstein, B.R. (2014) Dynamics of the Standard Model; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Fryberger, D. (1983) A model for the structure of point-like fermions: Qualitative features and physical description. Found. Phys. 13, 1059–1100. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P. W. (1964). Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Physical Review Letters, 13(16), 508–509. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. N., & Mills, R. L. (1954). Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance. Physical Review, 96(1), 191–195. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. (1967). A model of leptons. Physical Review Letters, 19(21), 1264–1266. [CrossRef]

- Glashow, S. L. (1961). Partial symmetries of weak interactions. Nuclear Physics, 22(4), 579–588. [CrossRef]

- Salam, A., & Ward, J. C. (1964). Electromagnetic and weak interactions. Physics Letters, 13(2), 168–171. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., Tang, Q. & Chang, C. (2025) Octonionic Preon Model for the Mass-ratio Prediction of the Weak and Higgs Bosons. Scientific Report (submitted).

- Tang, J. (2025) Emergence of Wave-Particle Duality and Uncertainty Principle: Causal Lattice Spacetime Field Theory without Vacuum Catastrophe. Communications in Math. Phys. (submitted).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

↔ SU(3), providing an elegant algebraic origin for electromagnetism, weak, and strong interactions. We argue that this layered algebraic development not only parallels the hierarchy of physical laws but may also provide the foundation for a unified framework of matter and force — one that transcends traditional field theory and bridges the mathematical and physical worlds. This hypercomplex framework provides a path from classical dynamics, through layer upon layer of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, special relativity, quantum electrodynamics, unified electroweak theory, quantum chromodynamics, and quantum gravity, to grand unification theory and quantum cosmology.

(Alternative)

(Alternative)