1. Introduction

Prematurity is one of the most well-established risk factors for the development of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and its associated hemodynamic complications. Numerous studies have demonstrated an inverse correlation between gestational age and the incidence of PDA. Additional contributing factors include low birth weight, the need for mechanical ventilation, systemic inflammation, low Apgar scores, and perinatal asphyxia. PDA has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several severe neonatal complications, including intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and retinopathy of prematurity [

1,

2]. Furthermore, increased mortality has been reported among neonates diagnosed with PDA.

Identifying individuals at increased risk of developing patent ductus arteriosus is of particular importance, especially among patients receiving care in neonatal intensive care units. While traditional risk factors remain relevant, contemporary diagnostic approaches should extend beyond the identification of neonates with clinically evident PDA. Efforts should focus on proactively recognizing preterm infants with a heightened predisposition to this condition, including those with underlying genetic susceptibility.

Among neonates, an increased incidence of patent ductus arteriosus has been observed in twins, who have long served as a model for investigating genetic determinants of disease. This association is particularly pronounced in monozygotic twins, suggesting a significant heritable component [

3,

4]. Moreover, studies in animal models have identified genetic factors that confer susceptibility to PDA, further supporting the role of inherited predisposition in its pathogenesis [

5,

6].

Among the most extensively described mechanisms regulating flow through the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is the postnatal increase in oxygen tension, which induces constriction of vascular smooth muscle and, consequently, cessation of flow [

7]. Antagonistic to the vasoconstrictive effect of oxygen is the action of prostaglandins. Prostaglandin E (PGE) plays a central role in maintaining ductal patency in utero. Its biological activity is mediated predominantly through the EP4 receptor, which is primarily expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. Activation of this receptor stimulates nitric oxide synthase, resulting in smooth muscle relaxation. The postnatal decline in PGE₂ concentrations, in conjunction with elevated partial oxygen pressure, contributes to ductal closure [

8,

9]. The synthesis of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid is catalyzed principally by cyclooxygenase-1, with the peroxidase site serving as the second catalytic domain [

10].

The genes analyzed in this study are located on distinct chromosomes and participate in the arachidonic acid–prostaglandin metabolic pathway. The PTGS1 gene, situated on chromosome 9q32–q33.3, encodes cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H₂. PTGES2, located on chromosome 9q34.11, encodes prostaglandin E synthase 2, which mediates the subsequent conversion of prostaglandin H₂ to prostaglandin E₂. The PTGER4 gene, mapped to chromosome 5p13.1, encodes one of the prostaglandin E₂ receptors (EP4), which is responsible for transducing its biological effects at the cellular level.

Several genes encoding phospholipase A₂ isoforms also contribute to this metabolic pathway. PLA2G4A, located on chromosome 1q31.1, and PLA2G4C, situated on chromosome 19q13.3, encode cytosolic phospholipase A₂ enzymes. PLA2G6, mapped to chromosome 22q13.1, and PLA2G7, located on chromosome 6p21.2, represent additional isoforms with distinct regulatory functions. Phospholipase A₂ enzymes play a pivotal role in the hydrolysis of ester bonds within membrane phospholipids, facilitating the release of arachidonic acid and other polyunsaturated fatty acids, which serve as key precursors for eicosanoid biosynthesis, including prostaglandins.

The pharmacological management of patent ductus arteriosus includes the use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors, such as ibuprofen and indomethacin, as well as the peroxidase inhibitor paracetamol, alongside the option of surgical ligation [

11]. None of these agents is devoid of systemic effects, particularly in the context of the physiologic immaturity of preterm neonates. Clinical evidence indicates notable interindividual variability in response to pharmacologic treatment. This heterogeneity may be partially explained by genetic polymorphisms within genes encoding enzymatic catalytic domains and prostaglandin receptors.

It is anticipated that elucidating the genetic basis of this variability and its clinical implications will enable more precise selection of pharmacological interventions and optimize therapeutic outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Definitions

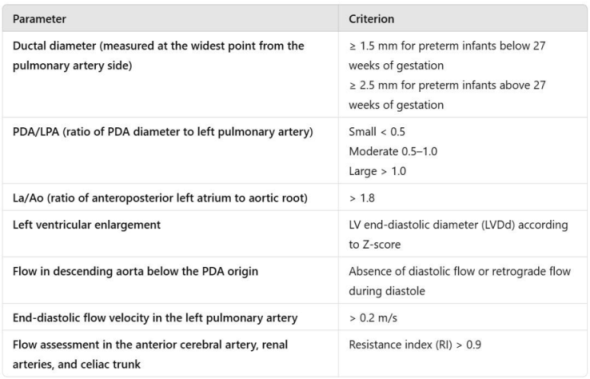

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is defined in the literature as a persistent vascular connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery with sustained blood flow beyond the fifth day of postnatal life. Hemodynamic significance was assessed according to the criteria established in current neonatal care guidelines (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Table 1 outlines the echocardiographic parameters employed in the definition of hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (HsPDA).

Table 1.

Table 1 outlines the echocardiographic parameters employed in the definition of hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (HsPDA).

2.2. Diagnosis of PDA

Diagnostic assessment was conducted using echocardiography, which remains the gold standard for the detection and monitoring of the ductus arteriosus. Examinations were performed by appropriately trained medical personnel. The determination of hemodynamic significance was based on the most recent guidelines of the Polish Neonatal Society. Echocardiographic evaluations were carried out using a Samsung V8 ultrasound system equipped with a PA4-12B transducer.

2.3. Study Design and Data Collection

The study included 99 preterm infants born between 27 and 32 weeks of gestation, who were hospitalized in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of the Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinical Hospital (GPSK) in Poznań during 2022 and 2023.

Neonates with congenital heart defects requiring surgical intervention, as well as those who died before the fifth day of life, were excluded from the study. Medical data were collected retrospectively from clinical records documented during hospitalization. Blood samples for genetic analysis were obtained during routine blood collection performed for standard diagnostic testing.

2.4. Ethics

Medical data were obtained from available patient records. To minimize the need for additional procedures, blood samples for genetic testing were collected concurrently with routine blood sampling. Efforts were made to reduce the volume of blood required for genotyping to a minimum (0.5 mL). In each case, the parents were informed in advance about the planned testing, its purpose, and provided written informed consent.

To ensure confidentiality, the number of personnel involved in data processing was restricted to the minimum necessary, and all data were encrypted. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (Resolution No. 96/22).

2.5. Genetic Testing Methodology

Blood for genetic polymorphism studies was collected in tubes containing EDTA (ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid). The tubes were stored at -20 o C until DNA isolation. DNA isolation from nucleated blood cells was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

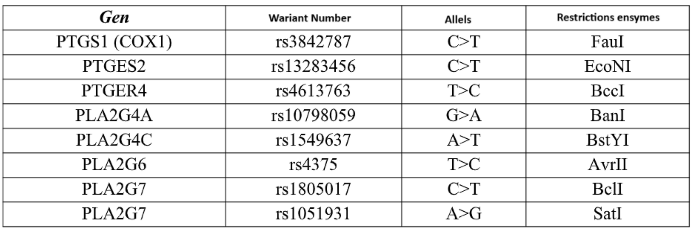

The polymorphic variants presented in the table were marked using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). (

Table 2)

The separation of RFLP reaction products was carried out in a 2.5% agarose gel in 1xTBE buffer at 120V for about 2 hours in the presence of a 50 bp standard. Based on the results of electrophoretic separation after visualization in UV light, individual genotypes were determined.

Table 2.

The study included analysis of the following genetic polymorphisms.

Table 2.

The study included analysis of the following genetic polymorphisms.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests, with or without Yates' continuity correction as appropriate, were used to compare dichotomous variables. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to estimate the strength of associations. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Software (version 2024) and Statistica (version 10, 2011; StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results

The study group comprised 99 preterm infants born between 27 and 31 weeks of gestation, including 45 females (45.45%) and 54 males (54.55%). Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) was diagnosed in 36 neonates, of whom 21 met the criteria for hemodynamically significant PDA (HsPDA). Pharmacological treatment was administered in 22 cases (22.22%), using either paracetamol or ibuprofen.

A statistically significant association was observed between the need for mechanical ventilation and the diagnosis of PDA, with affected infants requiring ventilatory support more frequently.

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) was diagnosed in 17 neonates (17.17%), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) in 39 neonates (39.39%), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in 52 neonates (52.53%), and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) in 46 neonates (46.46%). In the analyzed cohort, a statistically significant association was found between the occurrence of PDA and the presence of NEC, ROP, and BPD.

The characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 3. The distribution of individual single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) is presented in

Table 4.

Table 3.

The table displays the distribution of clinical variables in relation to the presence of PDA and HsPDA.

Table 3.

The table displays the distribution of clinical variables in relation to the presence of PDA and HsPDA.

| Characteristic |

|

| |

PDA |

P |

HsPDA |

P |

PDA vs HsPDA |

P |

|

| Sex |

Female |

12 |

p=0,089 |

Female |

7 |

p=1,0 |

Female |

12 vs 7 |

p= 1.0 |

|

| Male |

24 |

Male |

14 |

Male |

24 vs 14 |

|

| Gestational Age (week) |

<28 |

18 |

p=0.111 |

<28 |

13 |

p=0,176 |

<28 |

18 vs 13 |

p = 0,552 |

|

| >28 |

18 |

>28 |

8 |

>28 |

18 vs 8 |

|

| Birth weight (grams) |

<1000gram |

17 |

p=0,070 |

<1000gram |

13 |

p=0,080 |

<1000gram |

17 vs 13 |

p = 0,426 |

|

| >1000gram |

19 |

>1000gram |

8 |

>1000gram |

19 vs 8 |

|

| Prenatal steroid therapy |

Yes |

30 |

p=0,524 |

Yes |

18 |

p=1,0 |

Yes |

30 vs 18 |

p = 1,000 |

|

| No |

6 |

No |

3 |

No |

6 vs 3 |

|

| Invasive ventilation |

Yes |

23 |

p=0,0069 |

Yes |

14 |

p=0,9532 |

Yes |

23 vs 14 |

p = 0,552 |

|

| No |

13 |

No |

7 |

No |

13 vs 7 |

|

| Pharmacological ligation |

Yes |

21 |

p<0,0001 |

Yes |

21 |

p<0,0001 |

Yes |

21 vs 21 |

p = 0,0017 |

|

| No |

15 |

No |

0 |

No |

15 vs 0 |

|

| Ibuprofen |

Yes |

7 |

Yes |

7 |

Yes |

7 vs 7 |

|

| No |

0 |

No |

0 |

No |

0 vs 0 |

|

| Paracetamol |

Yes |

19 |

Yes |

18 |

Yes |

19 vs 18 |

|

| No |

3 |

No |

3 |

No |

3 vs 3 |

|

| Complications |

|

| NEC |

Yes |

11 |

p=0,012 |

Yes |

5 |

p = 0,501 |

Yes |

11 vs 5 |

p = 0,895 |

|

| No |

25 |

No |

15 |

No |

25 vs 15 |

|

| IVH |

Yes |

19 |

p=0,0629 |

Yes |

14 |

p = 0,1017 |

Yes |

19 vs 14 |

p = 0,4554 |

|

| No |

17 |

No |

7 |

No |

17 vs 7 |

|

| BPD |

Yes |

26 |

p = 0,0075 |

Yes |

15 |

p = 0,556 |

Yes |

26 vs 15 |

p = 1,0000 |

|

| No |

10 |

No |

6 |

No |

10 vs 6 |

|

| ROP |

Yes |

22 |

p = 0,048 |

Yes |

13 |

p = 1,000 |

Yes |

22 vs 13 |

p = 1,000 |

|

| No |

14 |

No |

8 |

No |

14 vs 8 |

|

Table 4.

Frequency of the studied single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the entire cohort (N = 99).

Table 4.

Frequency of the studied single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the entire cohort (N = 99).

| Gene |

rs number |

Genotypes, N (%) |

Alleles |

HWE (p-value) |

| PTGS1 (COX1) |

rs1236913 |

CC 86 (86.87%)

CT 13 (13.13%)

TT 0 (0.00%)

|

C 185 (93.43%)

T 13 (6.56%) |

1.000 |

| PTGES2 |

rs13283456 |

CC 91 (91.92%)

CT 7 (7.07%)

TT 1 (1.01%)

|

C 189 (95.45%)

T 9 (4.55%) |

0.173 |

| PTGER4 |

rs4613763 |

TT 68 (68.69%)

TC 29 (29.29%)

CC 2 (2.02%)

|

T 165 ( 83.33%)

C 33 (16.67%) |

1.000 |

| PLA2G4A |

rs10798059 |

GG 35 (35.35%)

AG 52 (52.53%)

AA 12 (12.12%)

|

G 122 (61.62%)

A 76 (38.38%) |

0.394 |

| PLA2G4C |

rs1549637 |

TT 77 (77.78%)

TA 19 (19.19%)

AA 3 (3.03%)

|

T 173 (87.37%)

A 25 (12.63%) |

0.177 |

| PLA2G6 |

rs4375 |

TT 29 (29.29%)

CT 60 (60.61%)

CC 10 (10.10%)

|

T 118 (59.60%)

C 80 (40.40%) |

0.013 |

| PLA2G7 |

rs1805017 |

CC 52 (52.53%)

CT 40 (40.40%)

TT 7 (7.07%)

|

C 144 (72.73%)

T 54 (27.27%) |

1.000 |

| PLA2G7 |

rs1051931 |

GG 61 (61.62%)

AG 33 (33.33%)

AA 5 (5.05%) |

G 155 (78.28%)

A 43 (21.72%) |

0.773 |

Analysis of the studied polymorphisms in relation to their potential role in promoting delayed closure of the ductus arteriosus (PDA) revealed an increased frequency of PDA among carriers of the rs1051931 polymorphism.

No statistically significant associations were observed for the remaining polymorphisms of the studied genes. Detailed results are presented in

Table 4.

A tendency toward delayed ductal closure was observed in neonates carrying the rs1051931 polymorphism, although the association did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.099).

For the remaining polymorphisms, no significant effect on the timing of ductus arteriosus closure was identified.

Assessment of the impact of individual polymorphisms on the occurrence of hemodynamically significant PDA (HsPDA) did not reveal any statistically significant associations. Comprehensive results are provided in

Table 5.

Table 5.

The influence of individual SNPs on the occurrence of PDA.

Table 5.

The influence of individual SNPs on the occurrence of PDA.

| model |

genotypes |

NO N (%)

|

YES N (%) |

OR (95%CI) |

p-value |

AIC |

| rs1236913 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

CC |

54 (85.7) |

32 (88.9) |

1.00 |

0.649 |

133.6 |

| |

CT |

9 (14.3) |

4 (11.1) |

0.75 (0.21-2.63) |

|

|

| rs13283456 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

CC |

57 (90.5) |

34 (94.4) |

1.00 |

1.000 |

134.7 |

| |

CT |

5 (7.9) |

2 (5.6) |

0.67 (0.12-3.65) |

|

|

| |

TT |

1 (1.6) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

| Dominant |

CC |

57 (90.5) |

34 (94.4) |

1.00 |

0.474 |

133.3 |

| |

CT-TT |

6 (9.5) |

2 (5.6) |

0.56 (0.11-2.93) |

|

|

| Recessive |

CC-CT |

62 (98.4) |

36 (100.0) |

1.00 |

1.000 |

132.9 |

| |

TT |

1 (1.6) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

| Overdominant |

CC-TT |

58 (92.1) |

34 (94.4) |

1.00 |

0.651 |

133.6 |

| |

CT |

5 (7.9) |

2 (5.6) |

0.68 (0.13-3.71) |

|

|

| rs4613763 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

TT |

46(73.0) |

22 (61.1) |

1.00 |

0.470 |

134.3 |

| |

TC |

16 (25.4) |

13 (36.1) |

1.70 (0.70-4.14) |

|

|

| |

CC |

1 (1.6) |

1 (2.8) |

2.09 (0.12-35.01) |

|

|

| Dominant |

TT |

46 (73.0) |

22 (61.1) |

1.00 |

0.222 |

132.3 |

| |

TC-CC |

17 (27.0) |

14 (38.9) |

1.72 (0.72-4.11) |

|

|

| Recessive |

TT-TC |

62 (98.4) |

35 (97.2) |

1.00 |

0.691 |

133.6 |

| |

CC |

1 (1.6) |

1 (2.8) |

1.77 (0.11-29.21) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

TT-CC |

47 (74.6) |

23 (63.9) |

1.00 |

0.263 |

132.5 |

| |

TC |

16 (25.4) |

13 (36.1) |

1.66 (0.68-4.03) |

|

|

| rs10798059 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

GG |

23 (36.5) |

12 (33.3) |

1.00 |

0.899 |

135.6 |

| |

GA |

32 (50.8) |

20 (55.6) |

1.20 (0.49-2.93) |

|

|

| |

AA |

8 (12.7) |

4 (11.1) |

0.96 (0.24-3.84) |

|

|

| Dominant |

GG |

23 (36.5) |

12 (33.3) |

1.00 |

0.750 |

133.7 |

| |

GA-AA |

40 (63.5) |

24 (66.7) |

1.15 (0.49-2.72) |

|

|

| Recessive |

GG-GA |

55 (87.3) |

32 (88.9) |

1.00 |

0.815 |

133.7 |

| |

AA |

8 (12.7) |

4 (11.1) |

0.86 (0.24-3.08) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

GG-AA |

31 (49.2) |

16 (44.4) |

1.00 |

0.648 |

133.6 |

| |

GA |

32 (50.8) |

20 (55.6) |

1.21 (0.53-2.76) |

|

|

| rs1549637 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

TT |

51 (81.0) |

26 (72.2) |

1.00 |

0.444 |

134.2 |

| |

TA |

11 (17.5) |

8 (22.2) |

1.43 (0.51-3.98) |

|

|

| |

AA |

1 (1.6) |

2 (5.6) |

3.92 (0.34-45.30) |

|

|

| Dominant |

TT |

51 (81.0) |

26 (72.2) |

1.00 |

0.320 |

132.8 |

| |

TA-AA |

12 (19.0) |

10 (27.8) |

1.63 (0.62-4.28) |

|

|

| Recessive |

TT-TA |

62 (98.4) |

34 (94.4) |

1.00 |

0.282 |

132.6 |

| |

AA |

1 (1.6) |

2 (5.6) |

3.65 (0.32-41.70) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

TT-AA |

52 (82.5) |

28 (77.8) |

1.00 |

0.566 |

133.5 |

| |

TA |

11 (17.5) |

8 (22.2) |

1.35 (0.49-3.75) |

|

|

| rs4375 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

TT |

19 (30.2) |

10 (27.8) |

1.00 |

0.950 |

135.7 |

| |

TC |

38 (60.3) |

22 (61.1) |

1.10 (0.43-2.78) |

|

|

| |

CC |

6 (9.5) |

4 (11.1) |

1.27 (0.29-5.56) |

|

|

| Dominant |

TT |

19 (30.2) |

10 (27.8) |

1.00 |

0.802 |

133.7 |

| |

TC-CC |

44 (69.8) |

26 (72.2) |

1.12 (0.45-2.78) |

|

|

| Recessive |

TT-TC |

57 (90.5) |

32 (88.9) |

1.00 |

0.802 |

133.7 |

| |

CC |

6 (9.5) |

4 (11.1) |

1.19 (0.31-4.52) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

TT-CC |

25 (39.7) |

14 (38.9) |

1.00 |

0.938 |

133.8 |

| |

TC |

38 (60.3) |

22 (61.1) |

1.03 (0.45-2.39)

|

|

|

| rs1805017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

CC |

32 (50.8) |

20 (55.6) |

1.00 |

0.401 |

134.0 |

| |

CT |

25 (39.7) |

15 (41.7) |

0.96 (0.41-2.25) |

|

|

| |

TT |

6 (9.5) |

1 (2.8) |

0.27 (0.03-2.38) |

|

|

| Dominant |

CC |

32 (50.8) |

20 (55.6) |

1.00 |

0.648 |

133.6 |

| |

CT-TT |

31 (49.2) |

16 (44.4) |

0.83 (0.36-1.88) |

|

|

| Recessive |

CC-CT |

57 (90.5) |

35 (97.2) |

1.00 |

0.178 |

132.0 |

| |

TT |

6 (9.5) |

1 (2.8) |

0.27 (0.03-2.35) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

CC-TT |

38 (60.3) |

21 (58.3) |

1.00 |

0.847 |

133.7 |

| |

CT |

25 (39.7) |

15 (41.7) |

1.09 (0.47-2.50)

|

|

|

| rs1051931 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codominant |

GG |

44 (69.8) |

17 (47.2) |

1.00 |

0.028 |

128.7 |

| |

GA |

18 (28.6) |

15 (41.7) |

2.16 (0.89-5.22) |

|

|

| |

AA |

1 (1.6) |

4 (11.1) |

10.35 (1.08-99.38) |

|

|

| Dominant |

GG |

44 (69.8) |

17 (47.2) |

1.00 |

0.027 |

128.9 |

| |

GA-AA |

19 (30.2) |

19 (52.8) |

2.59 (1.11-6.04) |

|

|

| Recessive |

GG-GA |

62 (98.4) |

32 (88.9) |

1.00 |

0.040 |

129.6 |

| |

AA |

1 (1.6) |

4 (11.1) |

7.75 (0.83-72.25) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

GG-AA |

45 (71.4) |

21 (58.3) |

1.00 |

0.186 |

132.0 |

| |

GA |

18 28.6) |

15 (41.7) |

1.79 (0.76-4.22) |

|

|

Table 6.

Association between individual SNPs and HsPDA incidence.

Table 6.

Association between individual SNPs and HsPDA incidence.

| |

genotypes |

NO

N (%) |

YES

N (%) |

OR (95%CI) |

p-value |

AIC |

rs1236913

Codominant |

CC |

13 (86.7) |

19 (90.5) |

1.00 |

0.722 |

52.8 |

| |

CT |

2 (13.3) |

2 (9.5) |

0.68 (0.09-5.49) |

|

|

rs13283456

Codominant |

CC |

13 (86.7) |

21 (100.0) |

1.00 |

0.167 |

49.2 |

| |

CT |

2 (13.3) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

rs4613763

Codominant |

TT |

9 (60.0) |

13 (61.9) |

1.00 |

0.697 |

53.1 |

| |

TC |

5 (33.3) |

8 (38.1) |

1.11 (0.27-4.51) |

|

|

| |

CC |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

| Dominant |

TT |

9 (60.0) |

13 (61.9) |

1.00 |

0.908 |

52.9 |

| |

TC-CC |

6 (40.0) |

8 (38.1) |

0.92 (0.24-3.59) |

|

|

| Recessive |

TT-TC |

14 (93.3) |

21 (100.0) |

1.00 |

0.417 |

51.1 |

| |

CC |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

| Overdominant |

TT-CC |

10 (66.7) |

13 (61.9) |

1.00 |

0.769 |

52.8 |

| |

TC |

5 (33.3) |

8 (38.1) |

1.23 (0.31-4.93) |

|

|

rs10798059

Codominant |

GG |

5 (33.3) |

7 (33.3) |

1.00 |

0.190 |

50.0 |

| |

GA |

10 (66.7) |

10 (47.6) |

0.71 (0.17-3.03) |

|

|

| |

AA |

0 (0.0) |

4 (19.0) |

— |

|

|

| Dominant |

GG |

5 (33.3) |

7 (33.3) |

1.00 |

1.000 |

52.9 |

| |

GA-AA |

10 (66.7) |

14 (66.7) |

1.00 (0.25-4.08) |

|

|

| Recessive |

GG-GA |

15 (100.0) |

17 (81.0) |

1.00 |

0.125 |

48.2 |

| |

AA |

0 (0.0) |

4 (19.0) |

— |

|

|

| Overdominant |

GG-AA |

5 (33.3) |

11 (52.4) |

1.00 |

0.254 |

51.6 |

| |

GA |

10 (66.7) |

10 (47.6) |

0.45 (0.12-1.79) |

|

|

rs1549637

Codominant |

TT |

12 (80.0) |

14 (66.7) |

1.00 |

0.711 |

52.5 |

| |

TA |

3 (20.0) |

5 (23.8) |

1.43 (0.28-7.26) |

|

|

| |

AA |

0 (0.0) |

2 (9.5) |

— |

|

|

| Dominant |

TT |

12 (80.0) |

14 (66.7) |

1.00 |

0.373 |

52.1 |

| |

TA-AA |

3 (20.0) |

7 (33.3) |

2.00 (0.42-9.49) |

|

|

| Recessive |

TT-TA |

15 (100.0) |

19 (90.5) |

1.00 |

0.500 |

50.7 |

| |

AA |

0 (0.0) |

2 (9.5) |

— |

|

|

| Overdominant |

TT-AA |

12 (80.0) |

16 (76.2) |

1.00 |

0.786 |

52.8 |

| |

TA |

3 (20.0) |

5 (23.8) |

1.25 (0.25-6.29) |

|

|

rs4375

Codominant |

TT |

6 (40.0) |

4 (19.0) |

1.00 |

0.350 |

52.8 |

| |

TC |

8 (53.3) |

14 (66.7) |

2.62 (0.57-12.18) |

|

|

| |

CC |

1 (6.7) |

3 (14.3) |

4.50 (0.34-60.15) |

|

|

| Dominant |

TT |

6 (40.0) |

4 (19.0) |

1.00 |

0.168 |

51.0 |

| |

TC-CC |

9 (60.0) |

17 (81.0) |

2.83 (0.63-12.71) |

|

|

| Recessive |

TT-TC |

14 (93.3) |

18 (85.7) |

1.00 |

0.461 |

52.4 |

| |

CC |

1 (6.7) |

3 (14.3) |

2.33 (0.22-24.92) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

TT-CC |

7 (46.7) |

7 (33.3) |

1.00 |

0.419 |

52.2 |

| |

TC |

8 (53.3) |

14 (66.7) |

1.75 (0.45-6.82) |

|

|

rs1805017

Codominant |

CC |

9 (60.0) |

11 (52.4) |

1.00 - |

0.491 |

52.6 |

| |

CT |

5 (33.3) |

10 (47.6) |

1.64 (0.41-6.56) |

|

|

| |

TT |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

| Dominant |

CC |

9 (60.0) |

11 (52.4) |

1.00 |

0.650 |

52.7 |

| |

CT-TT |

6 (40.0) |

10 (47.6) |

1.36 (0.36-5.22) |

|

|

| Recessive |

CC-CT |

14 (93.3) |

21 (100.0) |

1.00 |

0.417 |

51.1 |

| |

TT |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

— |

|

|

| Overdominant |

CC-TT |

10 (66.7) |

11 (52.4) |

1.00 |

0.389 |

52.2 |

| |

CT |

5 (33.3) |

10 (47.6) |

1.82 (0.46-7.18) |

|

|

rs1051931

Codominant |

GG |

7 (46.7) |

10 (47.6) |

1.00 |

0.321 |

52.6 |

| |

GA |

5 (33.3) |

10 (47.6) |

1.40 (0.33-5.93) |

|

|

| |

AA |

3 (20.0) |

1 (4.8) |

0.23 (0.02-2.73) |

|

|

| Dominant |

GG |

7 (46.7) |

10 (47.6) |

1.00 |

0.955 |

52.9 |

| |

GA-AA |

8 (53.3) |

11 (52.4) |

0.96 (0.26-3.63) |

|

|

| Recessive |

GG-GA |

12 (80.0) |

20 (95.2) |

1.00 |

0.151 |

50.8 |

| |

AA |

3 (20.0) |

1 (4.8) |

0.20 (0.02-2.15) |

|

|

| Overdominant |

GG-AA |

10 (66.7) |

11 (52.4) |

1.00 |

0.389 |

52.2 |

| |

GA |

5 (33.3) |

10 (47.6) |

1.82 (0.46-7.18) |

|

|

4. Discussion

Ongoing research into genetic determinants may enhance our understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and prognostic implications of patent ductus arteriosus, especially in preterm neonates who are inherently more susceptible to hemodynamic instability.

Our study focused on the analysis of polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes and receptors involved in the prostaglandin metabolism pathway, specifically phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase-1, prostaglandin synthetase 2, and the EP4 receptor. Genetic material was obtained from neonates born at our institution or in affiliated regional hospitals, resulting in a study cohort characterized by ethnic homogeneity. This methodological feature raises the possibility that the distribution of certain polymorphisms may differ in other European populations or globally, which may, in turn, influence the broader applicability and external validity of our findings.

Among the analyzed genes, the rs1051931 polymorphism was found to be associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of PDA development; in neonates carrying this variant, the odds ratio (OR) for PDA occurrence was elevated by 2.49-fold. This polymorphism is located within the gene encoding phospholipase A2, an enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of membrane phospholipids into arachidonic acid, a key substrate in the prostaglandin synthesis pathway.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to demonstrate an association between the rs1051931 polymorphism and the incidence of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in neonates. Existing literature includes numerous studies investigating the relationship between variants of this gene and their involvement in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. These studies primarily focus on the gene’s role in modulating the proinflammatory response and regulating phospholipid metabolism [

12,

13,

14].

Evidence from animal models, particularly in mice, indicates that impaired function of enzymes involved in the prostaglandin metabolism pathway—such as cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1,

Ptgs1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)—is associated with a significantly increased mortality rate [

15,

16]. Given the high degree of conservation in biochemical pathways across mammalian species, it is plausible that similar mechanisms may be relevant in human neonates, warranting further investigation. A comparable pattern has been observed with dysfunction of the EP4 receptor, which has been linked to an increased incidence of PDA and higher neonatal mortality [

17].

The development of hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (HsPDA) is of critical relevance in clinical practice, as disturbances in systemic perfusion associated with this condition are directly linked to an increased risk of severe complications, including intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, and mortality. Although echocardiographic assessment remains the current gold standard for the evaluation and monitoring of ductal patency, its implementation requires access to advanced imaging equipment and highly trained personnel. Moreover, it often necessitates additional procedures in a patient population composed largely of extremely preterm and clinically fragile neonates.

In the present study, none of the investigated polymorphisms demonstrated a statistically significant association with the development of HsPDA. However, in the case of the rs4375 polymorphism, a trend toward significance was observed under the codominant, dominant, and log-additive genetic models. These preliminary findings highlight the need for further research to elucidate the potential role of this variant in the pathophysiology of HsPDA.

Our study was conducted in a population of preterm infants, including those born at extremely low gestational ages. When evaluating outcomes in this group, it is essential to consider that extremely premature neonates possess a reduced amount of smooth muscle tissue within their vasculature, which may contribute to delayed closure of the ductus arteriosus. The initial phase of ductal closure involves vasoconstriction, which is dependent on the withdrawal of prostaglandin activity.

Although certain genetic predispositions were identified, well-established clinical risk factors—such as prematurity, low birth weight, and the need for mechanical ventilation—remain the most prominent contributors to the development of PDA and HsPDA. At present, the most effective strategy for preventing PDA and its associated complications appears to be the prevention of preterm birth. In cases where premature delivery cannot be avoided, perinatal management in specialized tertiary care centers remains essential to optimize neonatal outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The field of research concerning genetic predispositions to specific disease entities remains in its early stages. Observations of increased disease incidence in twins and in animal models strongly suggest that certain conditions have a substantial genetic component. Our study indicates that specific polymorphisms may contribute to the development of complications such as patent ductus arteriosus, including its hemodynamically significant form. Expanding this line of research through the recruitment of larger patient cohorts—particularly those representing diverse geographic and ethnic backgrounds—may facilitate the development of a robust genomic database. Such a resource could ultimately support the identification of neonates at elevated risk and enable earlier implementation of targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Author Contributions

M.M. conceived and designed the study. M.M. Z.B.M. collected the data. G.K. performed the statistical analysis. M.M. interpreted the results. M.M. drafted the manuscript. D. Sz. A.S.M critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant numbers 2021/05/x/nz5/01430 from National Science Center.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to data privacy regulations, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly accessible; however, they may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest. There are no financial disclosures to report for any authors.

References

- Gournay, V. The ductus arteriosus: physiology, regulation, and functional and congenital anomalies. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases 2011, 104, 578–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundscheid T, van den Broek M, van der Lee R, de Boode WP. Understanding the pathobiology in patent ductus arteriosus in prematurity - beyond prostaglandins and oxygen. Pediatric Research 2019, 86, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani A, Meraji SM, Houshyar R, et al. Finding genetic contributions to sporadic disease: a recessive locus at 12q24 commonly contributes to patent ductus arteriosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99, 15054–15059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari V, Zhou G, Bizzarro MJ, et al. Genetic contribution to patent ductus arteriosus in the premature newborn. Pediatrics. 2009, 123, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Strengers JL, Mentink M, Poelmann RE, Patterson DF: Histologic studies on normal and persistent ductus arteriosus in the dog. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985, 6, 394–404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokenkamp R, Gittenberger-De Groot AC, Van Munsteren CJ, Grauss RW, Ottenkamp J, Deruiter MC: Persistent ductus arteriosus in the Brown Norway inbred rat strain. Pediatr Res 2006, 60, 407–412. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann MA, Rudolph AM: Control of the ductus arteriosus. Physiol Rev 1975, 55, 62–78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clyman RI: Mechanisms regulating the ductus arteriosus. Biol Neonate 2006, 89, 330–335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggins KG, Latour A, Ngyuen MS, Audoly L, Coffman TM, Koller BH: Metabolism of PGE 2 by prostaglandin dehydrogenase is essential for remodeling the ductus arteriosus. Nat Med 2002, 8, 91–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheinlaender C, Weber SC, Sarioglu N, Strauss E, Obladen M, Koehne P: Changing expression of cyclooxygenases and prostaglandin receptor EP4 during development of the human ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res 2006, 60, 270–275. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-David Y, Hallak M, Rotschild A, Sorokin Y, Auslender R, Abramovici H: Indomethacin and fetal ductus arteriosus: complete closure after cessation of prolonged therapeutic course. Fetal Diagn Ther 1996, 11, 341–344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyun Li, Liping Qi, Naqiang Lv, Qian Gao, Yanmei Cheng, Yingjie Wei, Jue Ye, Xiaowei Yan, Aimin Dang Association between lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 gene polymorphism and coronary artery disease in the Chinese Han population.

- Gu X, Lin W, Xu Y, Che D, Tan Y, Lu Z, Pi L, Fu L, Zhou H, Jiang Z, Gu X. The rs1051931 G>A Polymorphism in the PLA2G7 Gene Confers Resistance to Immunoglobulin Therapy in Kawasaki Disease in a Southern Chinese Population. Front Pediatr. 2020, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maiolino G, Lenzini L, Pedon L, Cesari M, Seccia TM, Frigo AC, Rossitto G, Caroccia B, Rossi GP. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2015, 16, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftin CD, Trivedi DB, Tiano HF, et al. Failure of ductus arteriosus closure and remodeling in neonatal mice deficient in cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese J, Paria BC, Brown N, Zhao X, Morrow JD, Dey SK. Coordinated regulation of fetal and maternal prostaglandins directs successful birth and postnatal adaptation in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97, 9759–9764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen M, Camenisch T, Snouwaert JN, et al. The prostaglandin receptor EP4 triggers remodelling of the cardiovascular system at birth. Nature 1997, 390, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).