Key points:

A 10-year post-operative follow up of patients undergoing craniotomy in sitting position was performed.

Surgeries in sitting posture led to some neurological complications, irrespective of patient age.

Patients above 50 years of age were 2.2 times more likely to experience delirium and 3.6 times more likely to be deceased.

Introduction

The sitting position for craniotomies, although often surgically advantageous, can impose serious risks to patient safety [

1]. From a surgical perspective, the sitting position provides superior brain relaxation and reduces intracranial pressure due to enhanced jugular venous drainage [

2,

3]. However, the sitting position requires increasing mean arterial pressure to overcome gravity-mediated reductions in cerebral perfusion [

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, the sitting position increases risk of venous air embolism (VAE) and other serious and life-threatening complications [

1,

2,

6]. Given this unique risk-benefit ratio and the dearth of outcome data, we investigated long-term outcomes of patients undergoing craniotomies in sitting position using a real-world data (RWD) analysis and studied how age modifies these outcomes.

Methods

We performed RWD analysis using global federated health research network tool – TriNetX. TriNetX provides statistics on electronic medical records (diagnoses, procedures, medications, etc.), and no protected health information is provided. All the data in this retrospective cohort study using TriNetX tool is deidentified, represented as aggregated counts, and statistical summaries - hence, IRB approval was not required for this study.

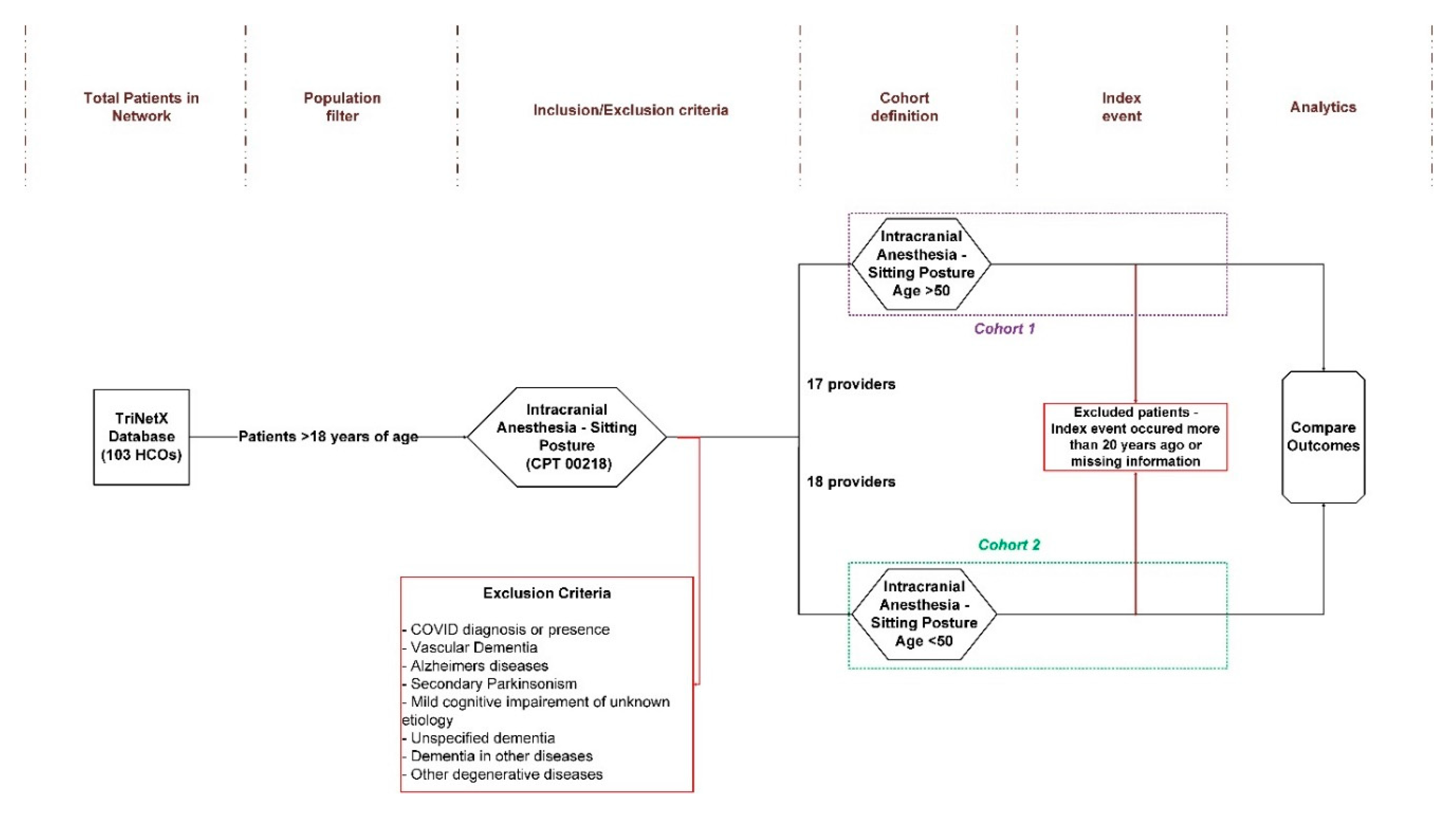

The detailed steps of the study are provided in

Figure 1 (supporting information provided in Supplement A-B). We focused on adult patients (greater than 18 years of age) in Healthcare Organization (HCOs) in the “Research” network that comprises of 103 institutions in 6 countries. We focused our analysis on patients that have undergone craniotomies in the sitting position (CPT 00218 - anesthesia for intracranial procedures; procedures in sitting position) until the query date (January 29

th, 2025). Selected patients were divided into two cohorts:

cohort 1 – patients greater than 50 years of age;

cohort 2 – patients with ages 18-50. Next, for the main outcomes of the study we evaluated pathological issues (detailed International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes provided in parenthesis) ten years after sitting position surgeries such as embolism-related complications (venous air embolism (air embolism - traumatic) - T79.0, air embolism following infusion, transfusion and therapeutic injection - T80.0, paradoxical embolism - I74.9, air embolism – all - T79.0, T79.0XXD, T79.0XXS, T79.0XXA, T80.0, I74.9, pulmonary embolism - I26.9), postprocedural complications (postprocedural hematoma - G97.61, pneumocephalus - G93.89), vascular and circulatory issues (cerebral ischemia - I67.82, hypotension - I95.9), neurological conditions (quadriplegia - G82.50, paraplegia - G82.20, nerve injuries - T14.8, delirium - F05, delirium – all -F05, R40.0, R41.0) [

10], hematomas and hemorrhages (subdural hematoma - G97.61, subdural hemorrhage - S06.5X0A, S06.5X0D, S06.5X0S), and other pathologies (macroglossia - Q38.2) including death [

1,

2,

6]. Patients with any COVID-19 diagnosis (TNX 9088), vascular dementia (ICD-10 F01), dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere (ICD-10 F02), unspecified dementia (ICD-10 F03), Alzheimer’s disease (ICD-10 G30), other degenerative diseases of nervous system (ICD-10 G31), secondary parkinsonism (ICD-10 G21), or mild cognitive impairment of unknown etiology (ICD-10 G31.84) were excluded from the patient cohorts. We followed STROBE recommendations for reporting the data.

Statistical analyses comparing these two cohorts were performed in TriNetX web interface and index event were taken from first day. We compared the aforementioned outcomes for a 10-year period. As mentioned in

Figure 1, patients meeting index criteria more than 20 years ago were excluded from the analysis. Aggregated counts below ten were rounded up for patient privacy in TriNetX and the same was noted in the findings. Risk ratio of a health event was calculated as ratio of incidence (or risk) in

cohort 1 to incidence (or risk) in

cohort 2. Risk ratio outputs were plotted using

forestplot package [

11] in

RStudio environment [

12]. Data was considered significant at

p<0.05.

Results

Detailed TriNetX output is provided in Supplement C. Patient data was analyzed from 1993 to 2024. We started with 135,324,401 patients in the TriNetX network across 103 HCOs in 6 countries. After application of population filter (only adults >18 years of age) and inclusion exclusion criteria, the cohort 1 (>50 years) comprised of 950 patients and cohort 2 (<50 years) comprised of 501 patients. Both patient cohorts belonged to United States only.

Detailed patient demographics for both cohorts are provided in

Table 1. Mean age of

cohort 1 was significantly greater than

cohort 2 by 44.6% (73.6±12.7 years vs. 32.8±8.99 years;

p<0.0001). Proportion of females in comparison to males was similar across cohorts (

cohort 1 - 52%:48% vs.

cohort 2 - 51%:49%;

p=0.6846). Furthermore,

cohort 1 had almost 9% (significantly) higher proportion of white patients as compared to

cohort 2 (60% vs 51%;

p<0.0001). Hispanic or Latino population was significantly greater in younger cohort (

cohort 2) as compared to older one (

cohort 1) (8% vs 3%;

p<0.0001).

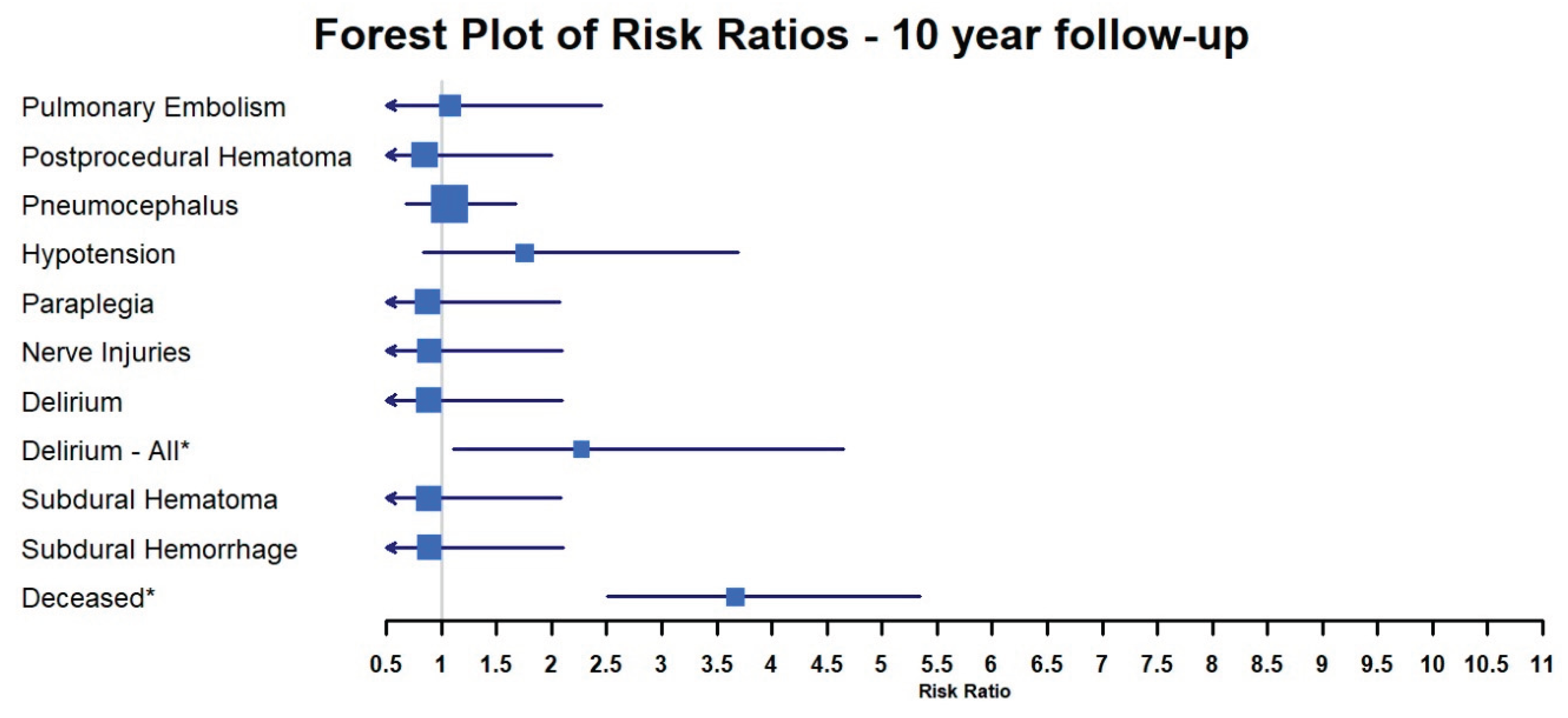

From the analyzed outcomes over a period of 10 years, the risk of pulmonary embolism (RR = 1.076(0.471-2.457);

p=0.863), postprocedural hematoma (RR = 0.853(0.355-2.003);

p=0.699), pneumocephalus (RR = 1.069(0.68-1.68);

p=0.773), hypotension (RR = 1.756(0.834-3.698);

p=0.132), paraplegia (RR = 0.873(0.368-2.071);

p=0.757), nerve injuries (RR = 0.885(0.373-2.099);

p=0.781), subdural hematoma (RR = 0.878(0.37-2.084);

p=0.768), and subdural hemorrhage (RR = 0.887(0.374-2.105);

p=0.785) was similar across both cohorts (

Figure 2,

Table 2). The risk of

any delirium event (or

Delirium-All here) was significantly 2.268 times greater in the older cohort as compared to the younger one (RR = 2.268 (1.106-4.652);

p=0.021); even though the aggregate counts for

cohort 2 were rounded up to

10. As expected, the risk of death was 3.663 times (significantly) greater for

cohort 1 vs.

cohort 2 (RR = 3.663 (2.51-5.346);

p<0.0001) (

Figure 2,

Table 2). Air embolism following infusion, transfusion and therapeutic injection (T80.0), air embolism – all (T79.0, T79.0XXD, T79.0XXS, T79.0XXA, T80.0, I74.9), cerebral ischemia (I67.82), and quadriplegia (G82.50) events were significant different across cohorts (

Table 2); however, aggregate counts for the cohorts were either zero or rounded up to 10. The risk ratio was not computed for venous air embolism (air embolism-traumatic), paradoxical embolism, and macroglossia as there were no reported cases in either cohort.

Discussion

Our retrospective cohort study was a real-world data (RWD) analysis, facilitated by TriNetX global network, on a ten-year follow-up on patients undergoing craniotomies in the sitting position. We provide insight into the post-operative outcomes of these patients, particularly as it pertains to age. Chiefly, the risk of delirium and death was significantly greater for patients over the age of fifty as compared to younger patients (18-50 years of age,

Figure 2,

Table 2). Other pathological risks were either non-significant across cohorts or too small to be quantified/analyzed further.

Estimated blood loss and transfusion requirements are lower for craniotomies in the sitting position [

13]. However, problems such as increased intraoperative hypotension, reduced cerebral perfusion and postoperative neurological deficits complicates these surgical benefits [

8]. Emamimeybodi et al. [

6] report a complication rate of 1.45%, with elevated chances of VAE in high head angle positions. Incidence of paradoxical air embolism in sitting position surgeries historically has been reported in a wide range (~14-76% in some cases) and is typically greater in patients that have a patent foramen ovale [

1,

14,

15]. Rath et al. [

2] reported that in their retrospective analysis of sitting position posterior fossa surgeries, VAE was detected in ~15.2% (from a total of 260 patients studies) and prolonged mechanical ventilation were noted, compared to traditional positions. Interestingly, Ture et al. [

16] report that 30° head elevations led to reduced incidence of VAE in sitting position surgeries (compared to 45° head elevations), and patients with meningioma were more prone to VAE risk than other types of surgical procedures. On the other hand, sitting positions procedures led to better lower cranial nerve functions, lowered blood loss/transfusion, and reduced overall duration of surgery.

The level of surgical details provided for each patient in TriNetX database is limited and hence it is difficult to ascertain the exact type of surgery or mode(s) of anesthesia utilized in this study. Our inclusion criteria, CPT 00218, provides patients that underwent anesthesia for craniotomies in the sitting position. However, it is uncertain whether all or none of the patients underwent surgery of the posterior fossa or any related brain region that is most prone to VAE risk. Similarly, there was no information regarding patent foramen ovale, presence of intracardiac right-to-left shunt, or head elevation angles for the cohorts in this study, to make a comparative analysis with previously published literature [

1,

6,

8,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Contrary to the above findings, we did not find any case of VAE in both young and old patient cohorts that underwent anesthesia for cranial procedure in sitting position.

The two major adverse events that stood out from the outcomes in the study were delirium and death. Delirium can be encoded by multiple ICD-10 codes, and hence, we analyzed delirium (F05) only and delirium-all (F05, R40, or R41) separately as suggested by Harrison et al. [

10]. Risk of delirium was 2.268 times greater for the older patient cohort (>50 years) over the follow up period of ten-years post-surgery. The root cause of post-operative delirium is multifactorial and cannot isolate a singular cause; however, lower cerebral perfusion could be one of the key factors. The lower cerebral perfusion pressure can be caused by overestimation of blood pressure in the brain due to the sitting position - “the waterfall effect” [

17]. This phenomenon can be the simplest way of explaining the overestimation of blood pressure in the brain i.e. the hydrostatic column of blood from the heart to the brain due to the sitting posture may be greater than the pressure measured at the brachial artery. This reduction in cerebral perfusion pressure could potentially lead to cerebral ischemia and cerebral desaturation events [

18,

19,

20]. We did find 11 cases of cerebral ischemia in the older cohort and zero cases in the younger cohort in our analysis (

Table 2). However, the delirium numbers were greater than the cerebral ischemia aggregated counts. Hence, cerebral ischemia may be one of the pathological outcomes, but it is not as critical as delirium for patients undergoing anesthesia for cranial procedures in sitting positions.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that shows that delirium is a key pathological event in the long term follow up of patients undergoing anesthesia for cranial procedures in sitting position. Taken together, the sitting posture, irrespective of the surgery type increases risk of delirium in patients older than 50 years. Further studies are necessary to understand if cerebral hypoperfusion or lower cerebral perfusion is the key mechanism for delirium occurrence in these patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgements

Assistance with article: None declared.

Financial support and sponsorship: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R21NS135307-01, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award Number UL1 TR003163, and the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Presentation: None declared.

Data Availability: The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

References

- Goraksha, S., B. Thakore, and J. Monteiro, Sitting Position in Neurosurgery. J Neuroanaesth Crit Care, 2019. 07(02): p. 077-083. [CrossRef]

- Rath, G.P., et al., Complications related to positioning in posterior fossa craniectomy. J Clin Neurosci, 2007. 14(6): p. 520-5. [CrossRef]

- Rozet, I. and M.S. Vavilala, Risks and benefits of patient positioning during neurosurgical care. Anesthesiol Clin, 2007. 25(3): p. 631-53, x. [CrossRef]

- Armstead, W.M., Cerebral Blood Flow Autoregulation and Dysautoregulation. Anesthesiol Clin, 2016. 34(3): p. 465-77. [CrossRef]

- Cecelja, M. and P. Chowienczyk, Molecular Mechanisms of Arterial Stiffening. Pulse (Basel), 2016. 4(1): p. 43-8. [CrossRef]

- Emamimeybodi, M., et al., Position-dependent hemodynamic changes in neurosurgery patients: A narrative review. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery, 2024. 36: p. 101886. [CrossRef]

- Sivanaser, V. and P. Manninen, Preoperative assessment of adult patients for intracranial surgery. Anesthesiol Res Pract, 2010. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Mavarez-Martinez, A., et al., The Effects of Patient Positioning on the Outcome During Posterior Cranial Fossa and Pineal Region Surgery. Front Surg, 2020. 7: p. 9. [CrossRef]

- Radu, O.M., et al., Influence of Patient Position-Related Differences in Intra- and Postoperative Implications on Major Anesthesia Parameters in Posterior Fossa Surgery. Preprints.org, 2024: p. 202409.1306.v1.

- Harrison, P.J., S. Luciano, and L. Colbourne, Rates of delirium associated with calcium channel blockers compared to diuretics, renin-angiotensin system agents and beta-blockers: An electronic health records network study. J Psychopharmacol, 2020. 34(8): p. 848-855. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M. and T. Lumley, Package ‘forestplot’.

- Team, R.C., R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2022.

- Black, S., et al., Outcome following posterior fossa craniectomy in patients in the sitting or horizontal positions. Anesthesiology, 1988. 69(1): p. 49-56. [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.R., P. Eshtehardi, and B. Meier, Patent foramen ovale and neurosurgery in sitting position: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth, 2009. 102(5): p. 588-96. [CrossRef]

- Klein, J., et al., A Systematic Review of the Semi-Sitting Position in Neurosurgical Patients with Patent Foramen Ovale: How Frequent Is Paradoxical Embolism? World Neurosurg, 2018. 115: p. 196-200. [CrossRef]

- Ture, H., et al., Effect of the degree of head elevation on the incidence and severity of venous air embolism in cranial neurosurgical procedures with patients in the semisitting position. J Neurosurg, 2018. 128(5): p. 1560-1569. [CrossRef]

- Stoelting, R.K. and R.D. Miller, Cerebral physiology and the effects of anesthetics and techniques., in Basics of anesthesia Ed. 5, P.P. Drummond JC, Editor. 2000, Churchill Livingstone: New York, NY. p. xii, 697-xii, 697.

- Fischer, G.W., et al., The use of cerebral oximetry as a monitor of the adequacy of cerebral perfusion in a patient undergoing shoulder surgery in the beach chair position. Pain Pract, 2009. 9(4): p. 304-7. [CrossRef]

- Rains, D.D., G.A. Rooke, and C.J. Wahl, Pathomechanisms and complications related to patient positioning and anesthesia during shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy, 2011. 27(4): p. 532-41. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, D.H., et al., Cerebral Desaturation Events During Shoulder Arthroscopy in the Beach Chair Position. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev, 2019. 3(8): p. e007. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).