Introduction

Cerebral aneurysms present a major clinical challenge because their potential for sudden rupture can lead to subarachnoid hemorrhage and severe neurological complications1,2. As advances in diagnostic imaging, such as time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography, have increased the incidental detection of unruptured aneurysms during unrelated medical evaluations3,4, the need for effective management strategies has grown. These strategies must minimize rupture risk while avoiding unnecessary interventions that carry additional complications1,2. Consequently, a deeper understanding of aneurysm biology, patient-specific risk factors (e.g., hypertension, smoking), and the factors driving aneurysm growth and rupture is essential to guide optimal treatment decisions.

The management of unruptured cerebral aneurysms is particularly complex due to the wide variability in their location, size, morphology, and growth potential—each contributing to a distinct risk profile5. Treatment decisions must carefully balance the risks of prophylactic surgical or endovascular intervention against the natural risk of rupture, while also considering patient-specific factors such as age, comorbidities, overall health status, and life expectancy. This complexity underscores the need for an individualized, multidisciplinary, and patient-centered approach.

Emerging research has identified key patterns in patient demographics, genetic and lifestyle influences on aneurysm development, and outcomes of various treatment strategies6,7. This retrospective cohort study seeks to delineate the clinical characteristics, therapeutic approaches, and postoperative results of individuals experiencing multiple unruptured cerebral aneurysms. This descriptive research aims to enhance future risk classification and management procedures, emphasising the necessity for individualised, patient-centered care in this intricate clinical context.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, we evaluated a cohort of 41 patients with multiple unruptured cerebral aneurysms, documenting demographics, aneurysm characteristics, treatment stages, and outcomes. We assessed patient demographics, risk factors, and symptoms using descriptive statistics to establish prevalence rates and associations. Aneurysm characteristics, including size and location, were analyzed by calculating the median and interquartile range of aneurysm sizes at various cerebral locations, extracting the maximum dimension for each aneurysm from clinical records. Treatment interventions were categorized and their frequency analyzed, with further examination of the durations and intervals between successive surgeries to evaluate treatment stages. Outcomes were quantitatively assessed by tracking post-operative complications, vasospasm incidence, hospital stay lengths, and neurological deficits, utilizing the Modified Rankin Scale (MRS) for follow-up assessments. Additionally, the impact of co-morbidity combinations on treatment outcomes was analyzed by identifying prevalent co-morbid conditions and their correlations with clinical outcomes using heatmaps and statistical correlation techniques. Data extraction and processing involved the use of Python and Pandas library for handling and analyzing clinical data, ensuring robust data manipulation and analysis. Due to the limited sample size and heterogeneity in patient and aneurysm characteris-tics, adjusted multivariable analyses were not feasible; therefore, only descriptive sta-tistics were performed.

Results

Patient Demographics, Risk Factors and Symptoms

Our study encompassed a total of 41 patients with multiple unruptured cerebral aneurysms, a total of 101 aneurysms. The cohort predominantly consisted of female patients, accounting for 82.93% of the total, with males representing 17.07%. The age of patients at the time of their first operation ranged from 32 to 78 years, with a median age of 58 years. As shown in

Table 1a, the analysis of risk factors revealed that hypertension (56.1%) and smoking (53.7%) were the most prevalent. Hyperlipidemia was also significant, present in 24.4% of the patients. As for the symptoms, headaches were the most commonly reported (48.8%), followed by vertigo (17.1%) and visual disturbances (14.6%). Notably, 17.1% of the cases were asymptomatic, discovered incidentally or during diagnostics for other conditions (

Table 1a).

Aneurysm Characteristics

We analyzed aneurysm characteristics in terms of size, numbers and the locations associated with the most commonly reported symptom. The analysis showed that among 41 patients revealed a predominance of medium aneurysms, with 48 classified as medium (5-10 mm), 40 as small (<5 mm), and 13 as large (>10 mm) aneurysm. The most common locations for aneurysms were the Middle Cerebral Artery Bifurcation on the left side (MCAB left) with 15 instances, followed by MCAB right with 12, and the Anterior Communicating Artery (Acom) with 11. Aneurysm distribution in patients showed that 28 patients had 2 aneurysms, 8 had 3, 4 had 4, and 1 had 5 aneurysms (

Table 1b).

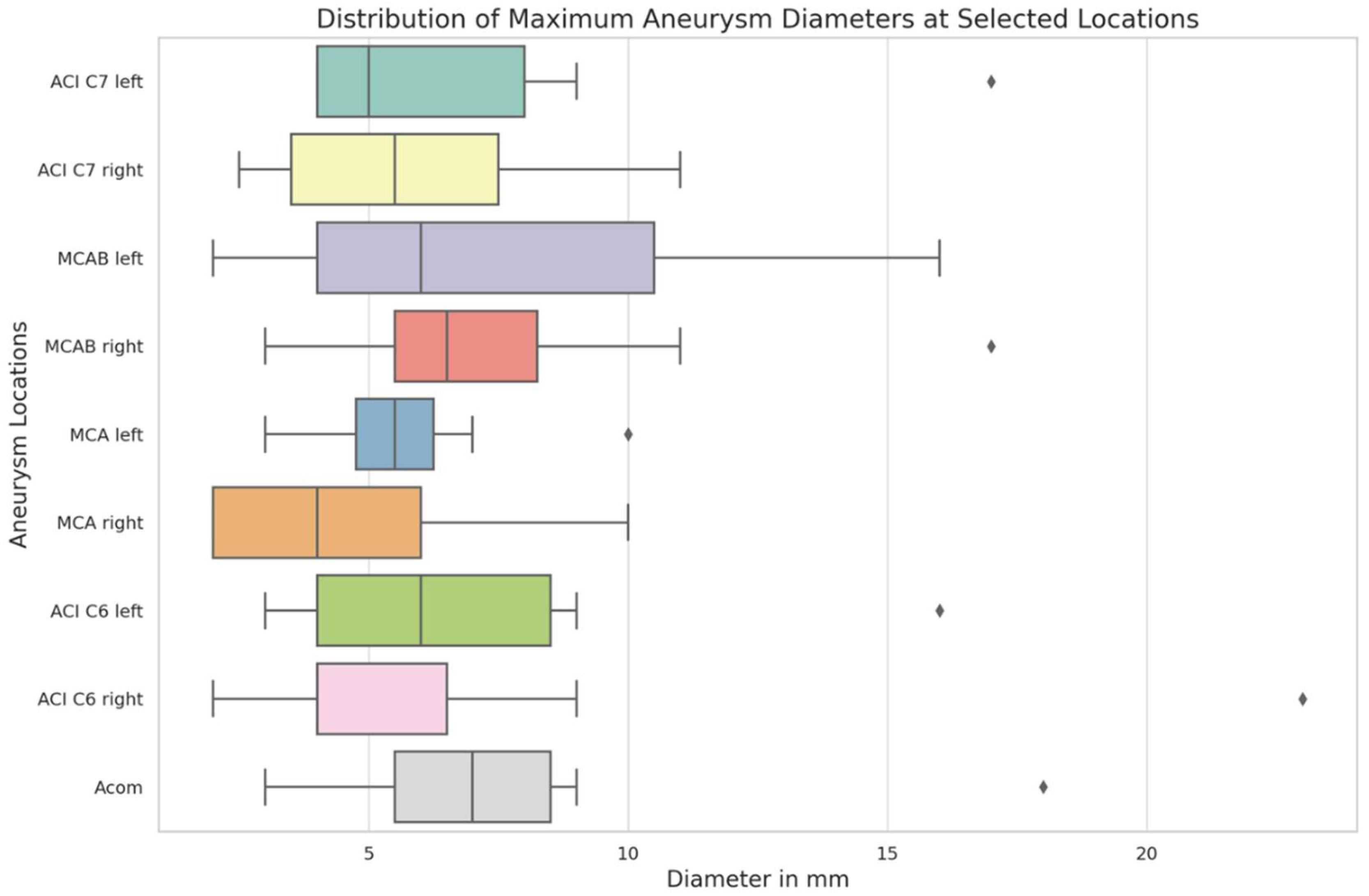

The distribution of maximum aneurysm diameters was analyzed across nine cerebral location (

Figure 1). The median diameters varied across these locations, with the smallest median diameter observed at MCA right (4.0 mm) and the largest at Acom (7.0 mm). The interquartile range showed a considerable spread in sizes, particularly in the MCAB left where the 75th percentile reached 10.5 mm, indicating a broader distribution of aneurysm sizes at this location. The Acom and both ACI C7 locations also exhibited wider variations in size, with the 75th percentile reaching 8.5 mm and 8.0 mm, respectively. Certain cerebral locations revealed notable variability. For instance, in the ACI C6 right, most aneurysm sizes were contained within a narrow range, but a significant outlier was observed, where the aneurysm diameter was substantially larger than typical values seen in this location. These outliers highlight variability in aneurysm size distributions within certain loca-tions, without clear implications for clinical outcomes in this cohort.

We identified multiple distinct combinations of aneurysm locations, with each combination typically unique to individual patients (

Table 1b). Further, our investigation into the association of headaches with these aneurysm locations unveiled a broad array of combinations, though each occurred infrequently, suggesting a diverse presentation among the study group. The most frequent combinations included locations such as ACI C7 right, MCAB left and MCA left among other combinations, which each presented in more than one patient (

Table 1b). Additionally, we quantitatively assessed the frequency of headaches across different aneurysm locations using a heatmap, which demonstrated that headaches are a common symptom across a wide range of aneurysm locations, with MCAB left and MCAB right being the most frequent locations, but overall no single location predominantly or significantly associated with this symptom in our cohort.

Treatment Stages and Interventions

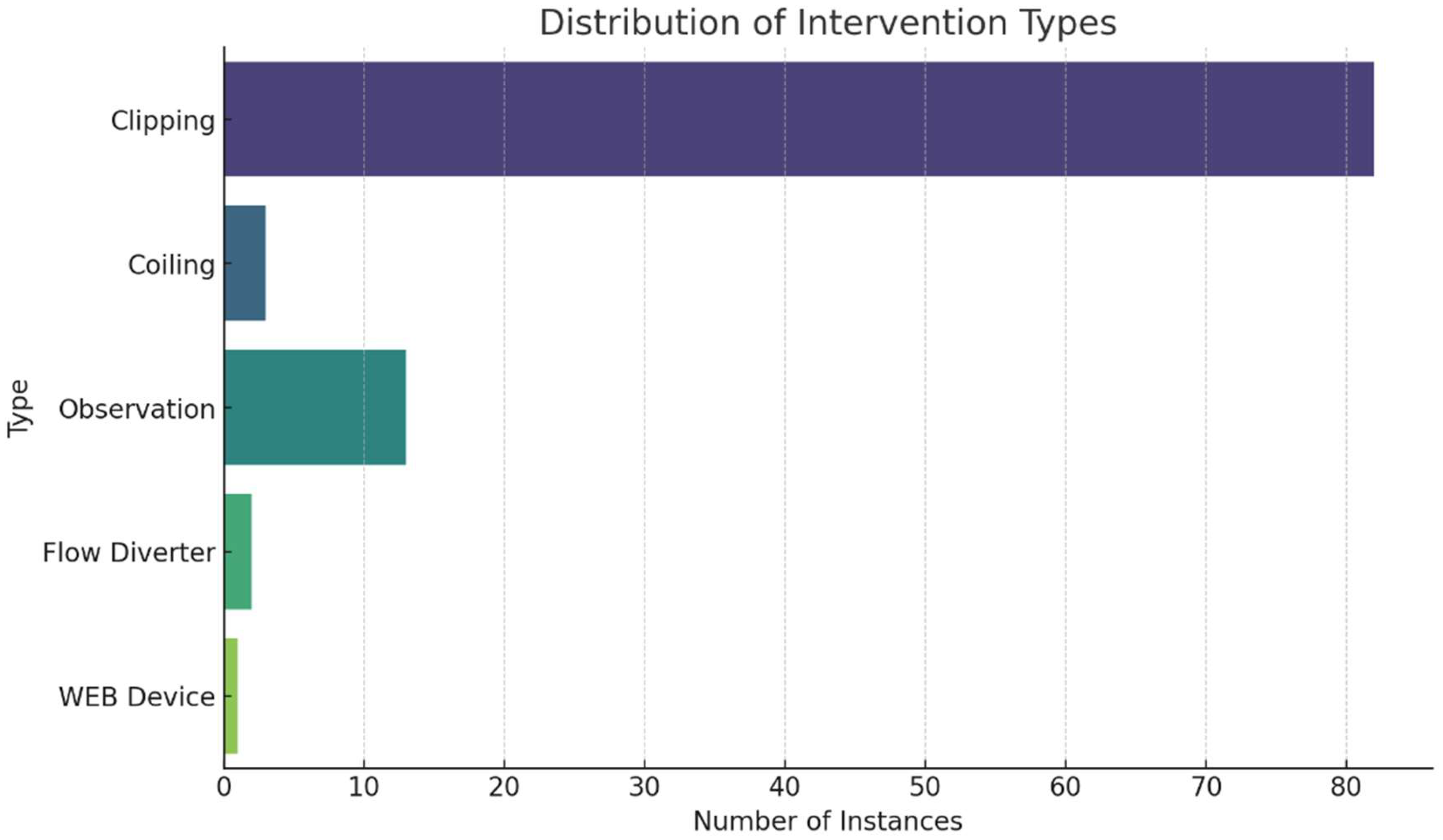

In examining treatment stages, 17 patients underwent a single-stage treatment, while 15 received treatment across two stages. For those needing multiple interventions, the average interval between the first and second operations was approximately 10.7 months, with a range from approximately 1.4 to 57.4 months. Only two patients required a third operation, with the intervals from the second to third operation averaging about 39.2 months, showing significant variability with a standard deviation of approximately 40.4 months. In our examination of treatment interventions, clipping emerged as the most frequently applied method, accounting for 82 anuerysms. Other approaches, such as observation and coiling, were less commonly used, with 13 and 3 instances, respectively. The Flow Diverter and WEB Device were utilized in only 2 and 1 cases, respectively (

Figure 2a). In our analysis of treatment combinations, ‘clipping only’ approach being the most frequent, applied to 24 patients. This was followed by ‘clipping and observation’ used for 9 patients, ‘observation only’ for 4 patients, and ‘coiling only’ for 2 patients. Other combinations such as ‘clipping with WEB Device’ and ‘clipping with coiling’ were each used for one patient (

Figure 2b).

Outcome Metrics

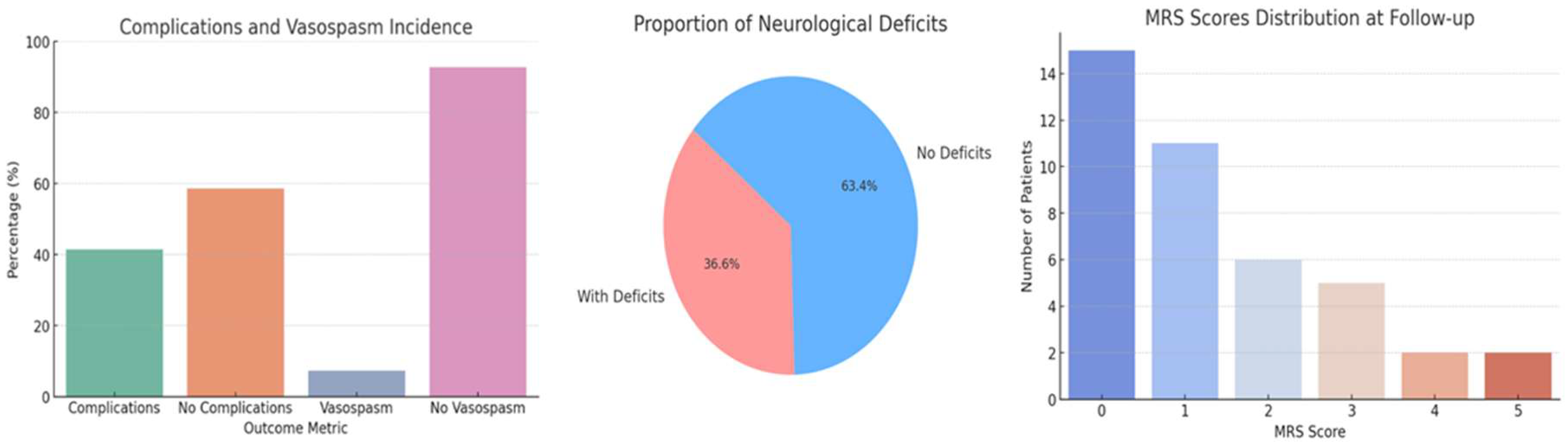

We identified a 41.4% incidence of post-operative complications, which encompassed a range of adverse events including, but not limited to, neurological deficits, infections, and other systemic complications. We also observed a 7.3% incidence of vasospasm (

Figure 3a). The average length of hospital stay following the first operation was 16.8 ± 10.8 days, with a substantial range up to 70 days, and reduced to an average of 10.6 ± 4 days after the second operation (

Table 1c). Neurological deficits were present in 36.6% of patients post-treatment, exhibiting a range of conditions including hemiparesis, aphasia, visual and gait disturbances, seizures, and cognitive impairments. The Modified Rankin Scale (MRS) scores at follow-up varied, with most patients scoring at lower levels, indicating minimal to moderate disability (

Figure 3c).

Impact of Co-Morbidity Combinations on Outcomes

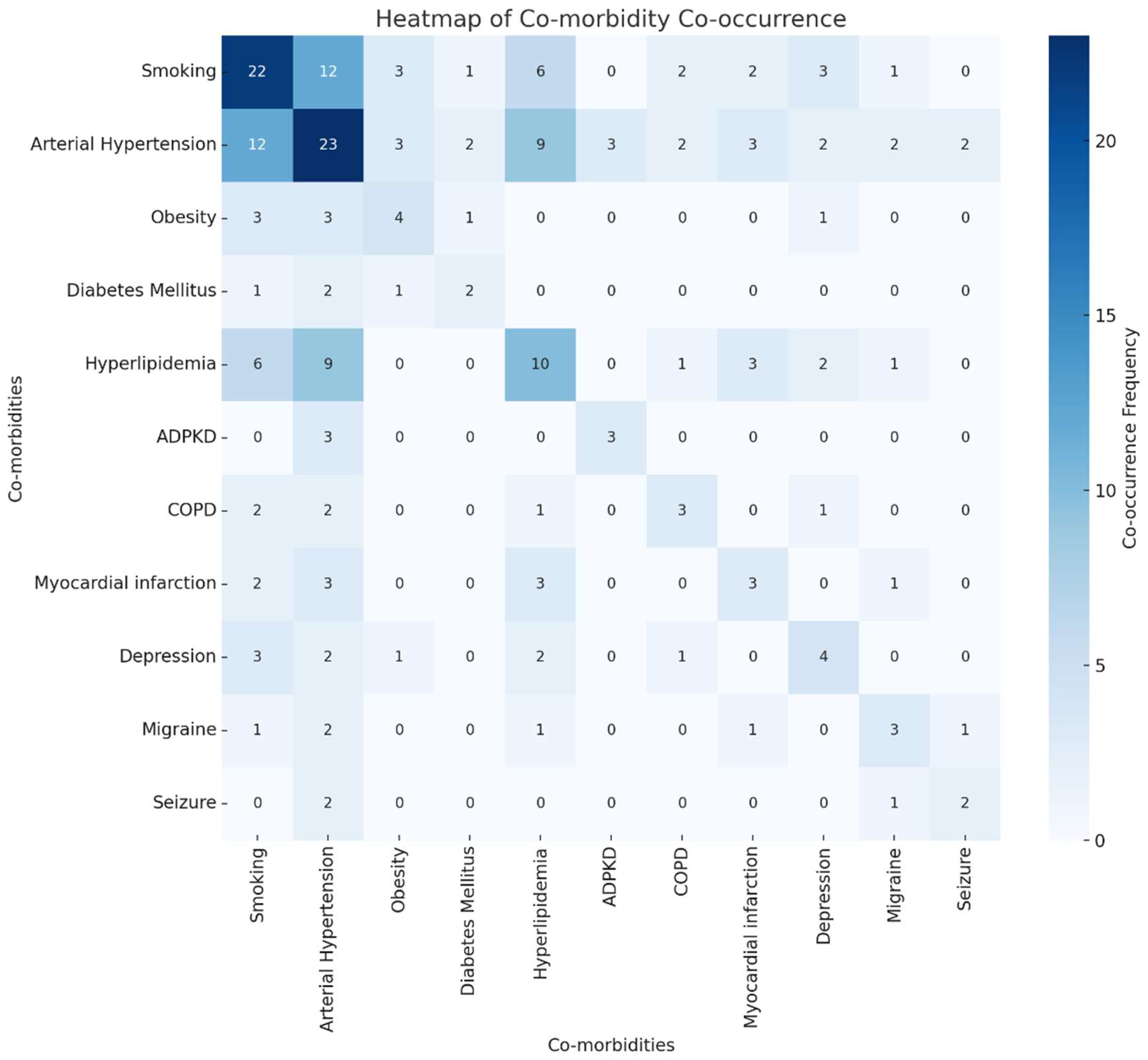

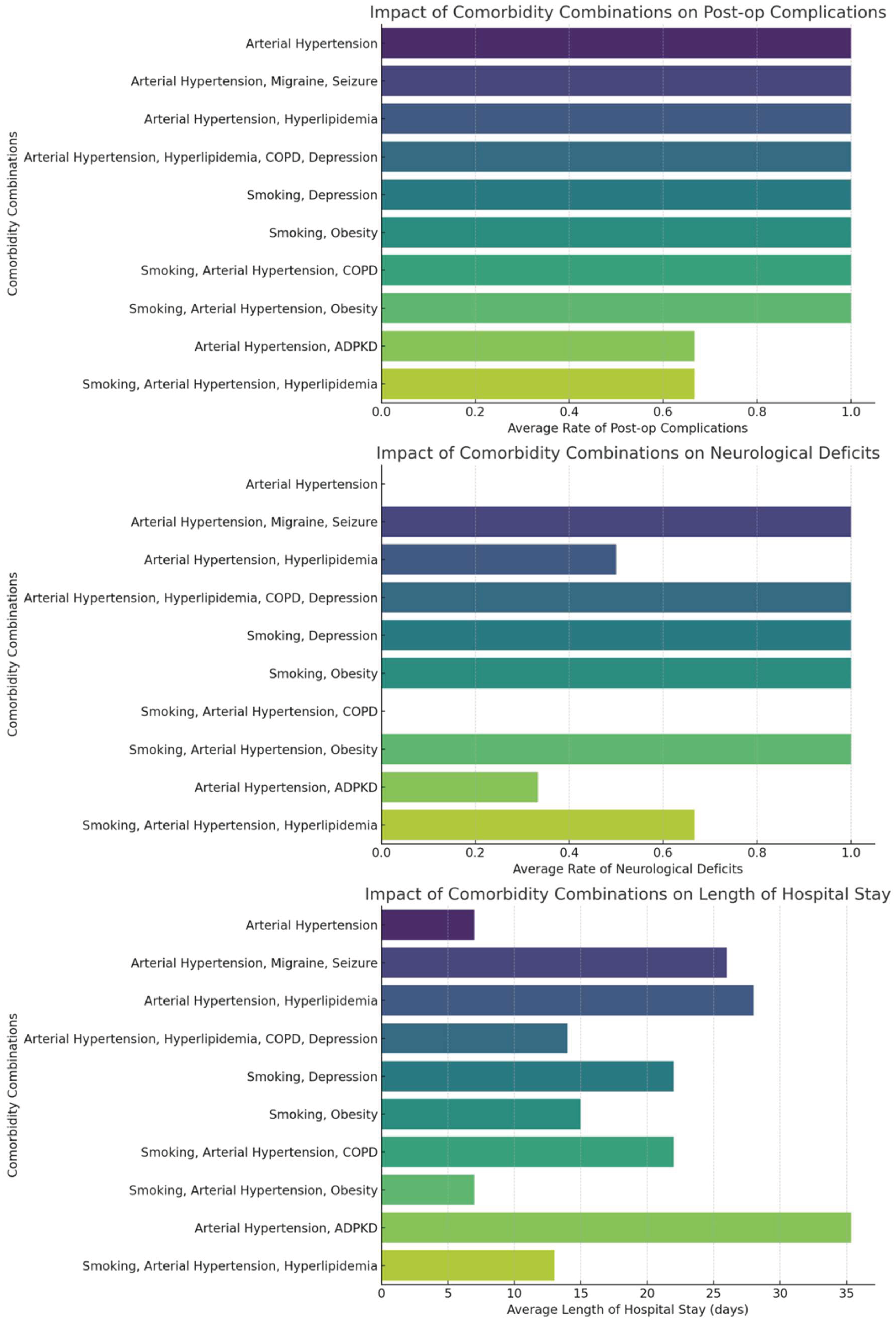

Our analysis of co-morbidity combinations among patients with multiple cerebral aneurysms revealed diverse impacts on treatment outcomes. The most common co-morbidities included arterial hypertension, smoking, and hyperlipidemia. The heatmap (

Figure 4) visualization of co-morbidity co-occurrences indicates frequent combinations of arterial hypertension with hyperlipidemia and smoking. As shown in

Figure 5, specific combinations such as arterial hypertension combined with hyperlipidemia appeared more frequently in patients with post-operative complications, neurological deficits, and longer hospital stays, but no statistical testing was performed to confirm significance. We quantified the average rates of these outcomes for the top ten most frequent co-morbidity combinations, providing a detailed overview of how multiple health conditions interplay in the clinical scenario.

Discussion

Patient Demographics, Risk Factors and Symptoms

The predominance of female patients in our study is consistent with epidemiological data indicating a higher prevalence of cerebral aneurysms among females8-10. The high rates of hypertension and smoking further support their potential roles in the pathogenesis or progression of aneurysms6,11-13. Similarly, the frequent occurrence of hyperlipidemia as a comorbidity points to a possible connection with vascular health and aneurysm stability, warranting further investigation14. Headache was the most common symptom, underscoring the diagnostic challenge posed by its overlap with other neurological conditions15. Additionally, the significant proportion of asymptomatic, incidentally discovered aneurysms emphasizes the critical role of imaging in early detection, which may guide proactive management strategies and improve outcomes. While some of these demographic and risk factor prevalence align with broader epidemiological trends, our study provides specific data from a cohort of patients with multiple unruptured cerebral aneurysms, contributing to the understanding of this specific patient subgroup.

Aneurysm Characteristics

The predominance of small and medium-sized aneurysms in our cohort suggests that current screening and imaging modalities are effective in detecting aneurysms at earlier, potentially less hazardous stages16. The frequent localization at bifurcation points—such as the middle cerebral artery bifurcation (MCAB) and anterior communicating artery (Acom)—reflects the high mechanical stress at these sites due to blood flow dynamics, which likely contributes to aneurysm formation17. This pattern underscores the need for targeted monitoring in high-stress vascular regions.

The variation in aneurysm sizes across different anatomical locations points to location-specific differences in aneurysm development and rupture risk18. A broader size range observed at sites like MCAB and the C7 segment of the internal carotid artery (ACI C7) may reflect more complex hemodynamic stressors that promote variable aneurysm growth19,20. In contrast, the narrower size distribution at the MCA suggests more uniform hemodynamic forces. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating location- and hemodynamics-based risk stratification into clinical assessment protocols21. Notably, the presence of outliers, such as the exceptionally large aneurysm at ACI C6, suggests that while most aneurysms follow predictable growth patterns, some may deviate due to unique vascular architecture, genetic predispositions, or less common environmental factors22.

The diversity in aneurysm location combinations and their relationship with symptoms, particularly headaches, reflects the complexity of cerebral aneurysm presentations. The individualized anatomical distribution, without a predominant headache-associated location, suggests that headaches are a generalized symptom rather than site-specific15,23-28. This challenges assumptions about location-dependent symptomatology and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive diagnostic approach in patients presenting with headaches. Visualization via a heatmap further illustrates the diffuse symptomatic burden of aneurysms, reinforcing the importance of broad differential diagnoses in clinical practice.

Treatment Stages and Outcomes

Treatment strategies for patients with multiple unruptured cerebral aneurysms vary widely, reflecting differences in aneurysm complexity and disease progression. The broad range of intervals between surgeries—particularly between the first and second operations—suggests that subsequent interventions are often guided by evolving clinical presentations and outcomes from earlier procedures29. Longer intervals before a third surgery may indicate either delayed aneurysm recurrence or a deliberate decision to monitor patients conservatively, influenced by factors such as age, overall health, and response to prior treatments.

Clipping remains the predominant intervention, likely reflecting its well-established efficacy and suitability for the aneurysm types encountered in our cohort, as well as surgeon preference or patient-specific anatomical considerations30,31. Newer, less invasive techniques like Flow Diverters and WEB Devices are used less frequently, suggesting a cautious and selective approach, reserved for cases where aneurysm morphology or patient factors favor these options. The use of combined strategies—such as ‘clipping and observation’—illustrates the nuanced, individualized decision-making process in managing unruptured aneurysms, balancing the risks of intervention against conservative management based on patient and aneurysm risk profiles.

The observed rates of postoperative complications (41.4%) and vasospasm (7.3%) in our cohort, while seemingly high for elective procedures, underscore the inherent risks associated with surgical treatment of cerebral aneurysms, particularly in patients with multiple unruptured lesions32,33. The complexity of these cases—often requiring multiple or staged interventions across different arterial territories—can increase the cumulative risk of adverse events. Our broad definition of complications likely contributed to the observed rate. While vasospasm is classically linked to subarachnoid hemorrhage, its presence following unruptured aneurysm surgery may result from intraoperative vessel manipulation, localized inflammation, or subtle subclinical bleeding, and thus remains a relevant marker of surgical morbidity in this context. The variability in hospital stay duration further reflects differences in surgical extent, individual recovery profiles, and complication severity. Neurological deficits post-treatment are not uncommon and highlight the vulnerability of critical brain regions involved in motor, sensory, and cognitive functions34. Reported deficits range from hemiparesis and aphasia to cognitive dysfunction, visual disturbances, and gait abnormalities, depending on aneurysm location and surgical approach35–38. The occurrence of multiple concurrent deficits in some patients illustrates the potential for widespread neurological impact, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary postoperative care, including tailored neurorehabilitation.

The distribution of Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at follow-up, predominantly skewed toward lower disability levels, is encouraging, indicating that many patients maintain good functional independence. However, the presence of patients with higher mRS scores signals serious disability in a subset, necessitating ongoing medical and supportive care39. These findings highlight the critical need for careful risk-benefit assessment in aneurysm management, with emphasis on enhanced preoperative evaluation, intraoperative monitoring, and comprehensive postoperative care to minimize complications and optimize recovery.

While our study presents aggregate outcome data, a detailed statistical comparison of outcomes across different treatment groups (e.g., clipping vs. observation or coiling) was limited by the retrospective design and the varying characteristics of aneurysms and patients within each treatment cohort. Future research, ideally with larger, prospectively collected datasets, would enable a more robust analysis of how specific treatment modalities impact outcomes in patients with multiple unruptured aneurysms.

Impact of Co-Morbidity Combinations on Outcomes

Our analysis showed that the coexistence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia ap-pears associated with a higher frequency of postoperative complications and prolonged recovery in our cohort, although no statistical tests were conducted to establish significance.. This likely reflects an underlying vascular pathology that both predisposes to aneurysm development and complicates surgical outcomes. The frequent co-occurrence of smoking with these conditions further worsens vascular health and surgical risk. Recognizing these patterns is essential for improving preoperative risk stratification and tailoring postoperative care to better address the needs of patients with complex comorbidities.

Managing unruptured cerebral aneurysms poses significant clinical challenges due to the complex balance between rupture risk and surgical morbidity. Existing tools, such as the Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score (UIATS) and PHASES score, guide decisions based on aneurysm features and patient demographics but often lack integration of detailed post-surgical outcome data that critically influence treatment choices40,41. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) offers a robust framework for surgical outcome evaluation across procedures but is not tailored to the specific nuances of neurosurgical interventions for cerebral aneurysms42.

Limitations

While comprehensive, our study has several limitations. Its retrospective design may introduce biases related to data selection and documentation. The relatively modest overall sample size (N=41), especially within subgroups defined by specific co-morbidity combinations, naturally restricts the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the single-center nature of the study may affect the applicability of results to other populations or clinical settings. Future research with larger, multi-center cohorts and prospective designs would be beneficial to validate and expand upon our observations, including comparisons with established risk stratification tools such as PHASES or UIATS, to ensure broader relevance and robustness. Future research with larger, multi-center cohorts and prospective designs is needed to validate and expand upon our observations, ensuring broader relevance and robustness.

Conclusion

This study underscores the complexity of managing multiple unruptured cerebral aneurysms, shaped by diverse aneurysm characteristics and patient-specific risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking. Clipping emerged as the most common treatment modality, with individualized treatment strategies reflected in the variable timing of interventions. Although post-operative complications, including vasospasm and neurological deficits like hemiparesis and aphasia, were observed, most patients maintained functional independence at follow-up. Our descriptive findings contribute valuable data on the clinical profiles, management, and outcomes of this patient subgroup.

Funding

The following research received no external funding.

Credit Authorship Contribution Statement

Oday Atallah and Khadeja Alrefaie: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis. Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Amr Badary: acted as the supervising author, overseeing the study’s conceptualization, methodology, and critical review of the manuscript. All Authors: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. All Authors: Approval of final draft.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The following study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards detailed in the Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. Given its retrospective nature and the use of de-identified patient data, the study was granted an exemption from formal Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Informed Consent Statement

In view of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was not required by the ethics committee. All patients consented to the scientific use of their medical data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the following study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Etminan N, Rinkel GJ. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: development, rupture and preventive management. Nat Rev Neurol. Dec 2016;12(12):699-713. [CrossRef]

- Renowden S, Nelson R. Management of incidental unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Pract Neurol. Oct 2020;20(5):347-355. [CrossRef]

- Lehnen NC, Haase R, Schmeel FC, et al. Automated Detection of Cerebral Aneurysms on TOF-MRA Using a Deep Learning Approach: An External Validation Study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Dec 2022;43(12):1700-1705. [CrossRef]

- Laukka D, Kivelev J, Rahi M, et al. Detection Rates and Trends of Asymptomatic Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms From 2005 to 2019. Neurosurgery. Feb 1 2024;94(2):297-306. [CrossRef]

- Andic C, Aydemir F, Kardes O, Gedikoglu M, Akin S. Single-stage endovascular treatment of multiple intracranial aneurysms with combined endovascular techniques: is it safe to treat all at once? J Neurointerv Surg. Nov 2017;9(11):1069-1074. [CrossRef]

- McDowell MM, Zhao Y, Kellner CP, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of multiple intracranial aneurysms in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. Apr 2018;128(4):961-968. [CrossRef]

- Brinjikji W, Rabinstein AA, Lanzino G, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ. Effect of age on outcomes of treatment of unruptured cerebral aneurysms: a study of the National Inpatient Sample 2001-2008. Stroke. May 2011;42(5):1320-4. [CrossRef]

- Krzyzewski RM, Klis KM, Kucala R, et al. Intracranial aneurysm distribution and characteristics according to gender. Br J Neurosurg. Oct 2018;32(5):541-543. [CrossRef]

- Ostergaard JR, Hog E. Incidence of multiple intracranial aneurysms. Influence of arterial hypertension and gender. J Neurosurg. Jul 1985;63(1):49-55. [CrossRef]

- Freneau M, Baron-Menguy C, Vion AC, Loirand G. Why Are Women Predisposed to Intracranial Aneurysm? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:815668. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad S. Clinical outcome of endovascular coil embolization for cerebral aneurysms in Asian population in relation to risk factors: a 3-year retrospective analysis. BMC Surg. May 14 2020;20(1):104. [CrossRef]

- Karhunen V, Bakker MK, Ruigrok YM, Gill D, Larsson SC. Modifiable Risk Factors for Intracranial Aneurysm and Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Am Heart Assoc. Nov 16 2021;10(22):e022277. [CrossRef]

- Ho AL, Lin N, Frerichs KU, Du R. Smoking and Intracranial Aneurysm Morphology. Neurosurgery. Jul 2015;77(1):59-66; discussion 66. [CrossRef]

- Can A, Castro VM, Dligach D, et al. Lipid-Lowering Agents and High HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) Are Inversely Associated With Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture. Stroke. May 2018;49(5):1148-1154. [CrossRef]

- Kwon OK. Headache and Aneurysm. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. May 2019;29(2):255-260. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Shen B, Ma C, et al. 3D contrast enhancement-MR angiography for imaging of unruptured cerebral aneurysms: a hospital-based prevalence study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114157. [CrossRef]

- Castro MA, Putman CM, Sheridan MJ, Cebral JR. Hemodynamic patterns of anterior communicating artery aneurysms: a possible association with rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Feb 2009;30(2):297-302. [CrossRef]

- San Millan Ruiz D, Yilmaz H, Dehdashti AR, Alimenti A, de Tribolet N, Rufenacht DA. The perianeurysmal environment: influence on saccular aneurysm shape and rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Mar 2006;27(3):504-12.

- Soldozy S, Norat P, Elsarrag M, et al. The biophysical role of hemodynamics in the pathogenesis of cerebral aneurysm formation and rupture. Neurosurg Focus. Jul 1 2019;47(1):E11. [CrossRef]

- Cmiel-Smorzyk K, Kawlewska E, Wolanski W, Hebda A, Ladzinski P, Kaspera W. Morphometry of cerebral arterial bifurcations harbouring aneurysms: a case-control study. BMC Neurol. Feb 10 2022;22(1):49. [CrossRef]

- Ho AL, Mouminah A, Du R. Posterior cerebral artery angle and the rupture of basilar tip aneurysms. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110946. [CrossRef]

- Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, Siddiqui A. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Jul 2014;35(7):1254-62. [CrossRef]

- Toma A, De La Garza Ramos R, Altschul DJ. Risk Factors for Headache Disorder in Patients With Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Cureus. May 2023;15(5):e38385. [CrossRef]

- Valenca MM, Andrade-Valenca LP, Martins C, et al. Cluster headache and intracranial aneurysm. J Headache Pain. Oct 2007;8(5):277-82. [CrossRef]

- Ji W, Liu A, Yang X, Li Y, Jiang C, Wu Z. Incidence and predictors of headache relief after endovascular treatment in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. Feb 2017;23(1):18-27. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Kim SH, et al. Effect of endovascular treatment on headaches in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Headache. Nov-Dec 2003;43(10):1090-6. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Catarino M, Frisen L, Wikholm G, Elfverson J, Quiding L, Svendsen P. Internal carotid artery aneurysms, cranial nerve dysfunction and headache: the role of deformation and pulsation. Neuroradiology. Apr 2003;45(4):236-40. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi PK. Motor Aphasia Attributed to Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysm. Journal of Neurology and Neuroscience. 2017;08(06). [CrossRef]

- Lodi Y, Latorre J, El-Zammar Z, et al. Single Stage versus Multi-staged Stent-assisted Endovascular Repair of Intracranial Aneurysms. J Vasc Interv Neurol. Jul 2011;4(2):24-8.

- Mohammad F, Horiguchi T, Mizutani K, Yoshida K. Clipping versus coiling in unruptured anterior cerebral circulation aneurysms. Surg Neurol Int. 2020;11:50. [CrossRef]

- Asilturk M, Abdallah A. Clinical outcomes of multiple aneurysms microsurgical clipping: Evaluation of 90 patients. Neurol Neurochir Pol. Jan-Feb 2018;52(1):15-24. [CrossRef]

- Peterson CM, Podila SS, Girotra T. Unruptured aneurysmal clipping complicated by delayed and refractory vasospasm: case report. BMC Neurol. Sep 12 2020;20(1):344. [CrossRef]

- Campe C, Neumann J, Sandalcioglu IE, Rashidi A, Luchtmann M. Vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia after uneventful clipping of an unruptured intracranial aneurysm - a case report. BMC Neurol. Sep 16 2019;19(1):226. [CrossRef]

- Ji W, Liu A, Lv X, et al. Risk Score for Neurological Complications After Endovascular Treatment of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Stroke. Apr 2016;47(4):971-8. [CrossRef]

- Bonares MJ, de Oliveira Manoel AL, Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA. Behavioral profile of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. Mar 2014;1(3):220-32. [CrossRef]

- Egeto P, Loch Macdonald R, Ornstein TJ, Schweizer TA. Neuropsychological function after endovascular and neurosurgical treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg. Mar 2018;128(3):768-776. [CrossRef]

- Kim YJ, Lee SH, Jeon JP, Choi HC, Choi HJ. Clinical Factors Contributing to Cognitive Function in the Acute Stage after Treatment of Intracranial Aneurysms: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Med. Aug 28 2022;11(17). [CrossRef]

- Kim BM, Kim DI, Shin YS, et al. Clinical outcome and ischemic complication after treatment of anterior choroidal artery aneurysm: comparison between surgical clipping and endovascular coiling. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Feb 2008;29(2):286-90. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh AS, Priola SM, Katsanos AH, et al. The Management of Intracranial Aneurysms: Current Trends and Future Directions. Neurol Int. Jan 3 2024;16(1):74-94. [CrossRef]

- Etminan N, Brown RD, Jr., Beseoglu K, et al. The unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score: a multidisciplinary consensus. Neurology. Sep 8 2015;85(10):881-9. [CrossRef]

- Greving JP, Wermer MJ, Brown RD, Jr., et al. Development of the PHASES score for prediction of risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a pooled analysis of six prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. Jan 2014;13(1):59-66. [CrossRef]

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. Nov 2013;217(5):833-42 e1-3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).