Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

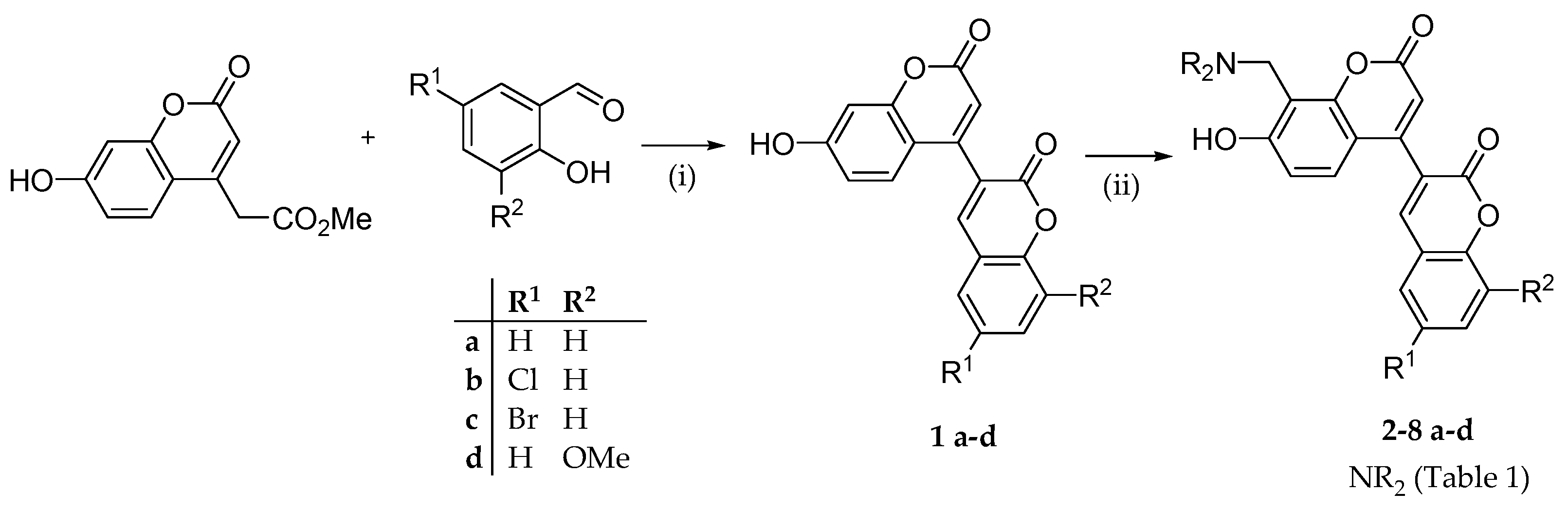

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Structure-Activity Relationships

2.2.1. In-Vitro Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidases and Cholinesterases

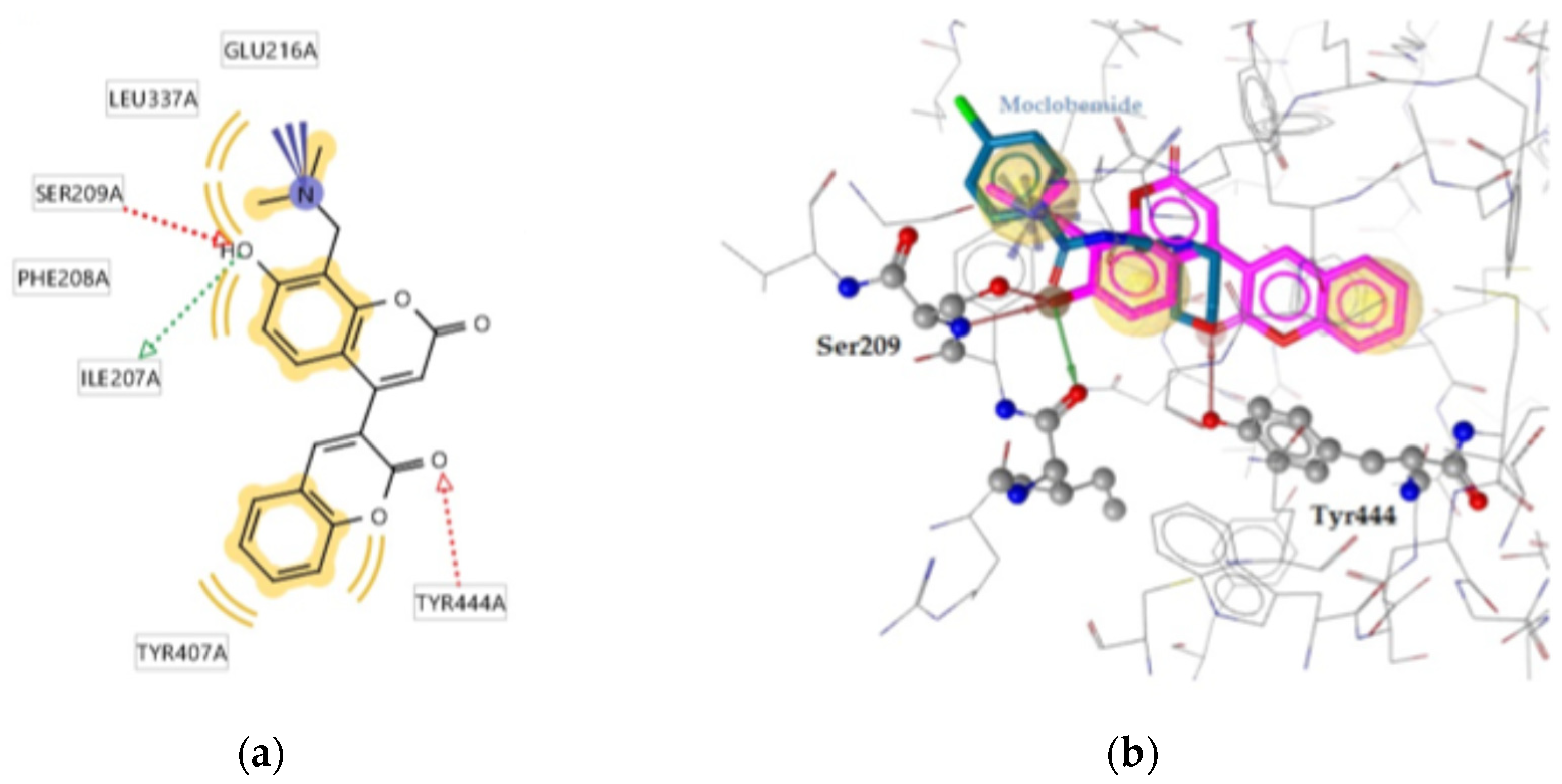

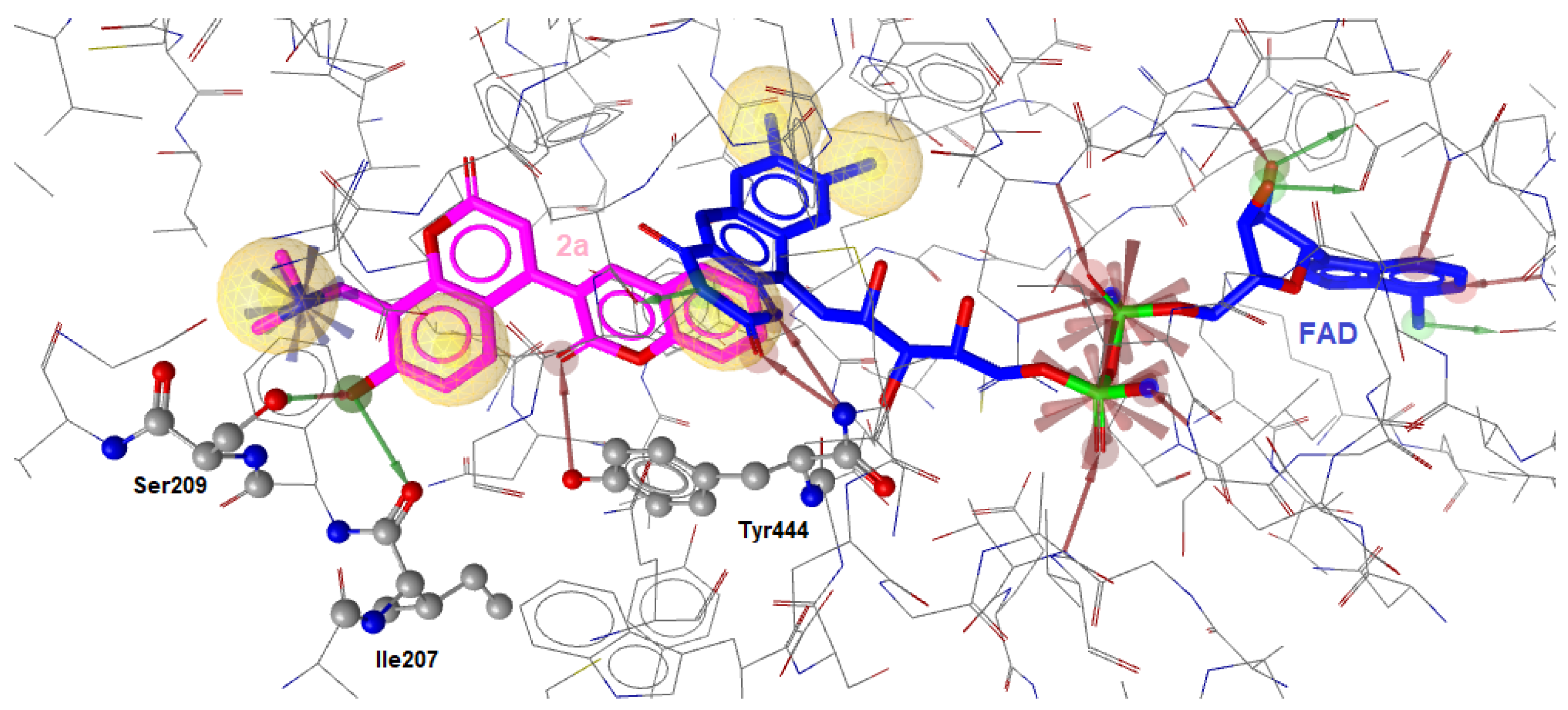

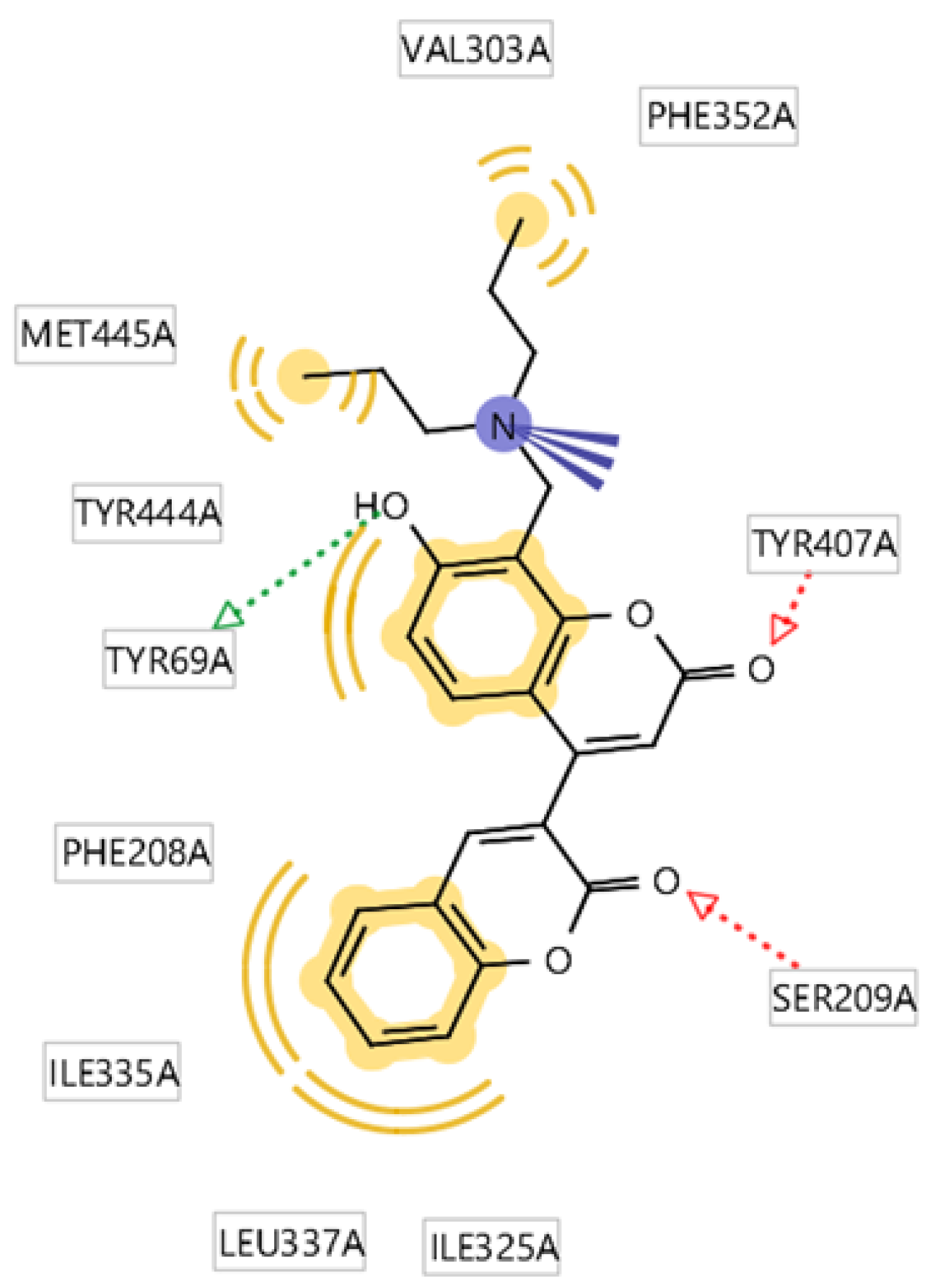

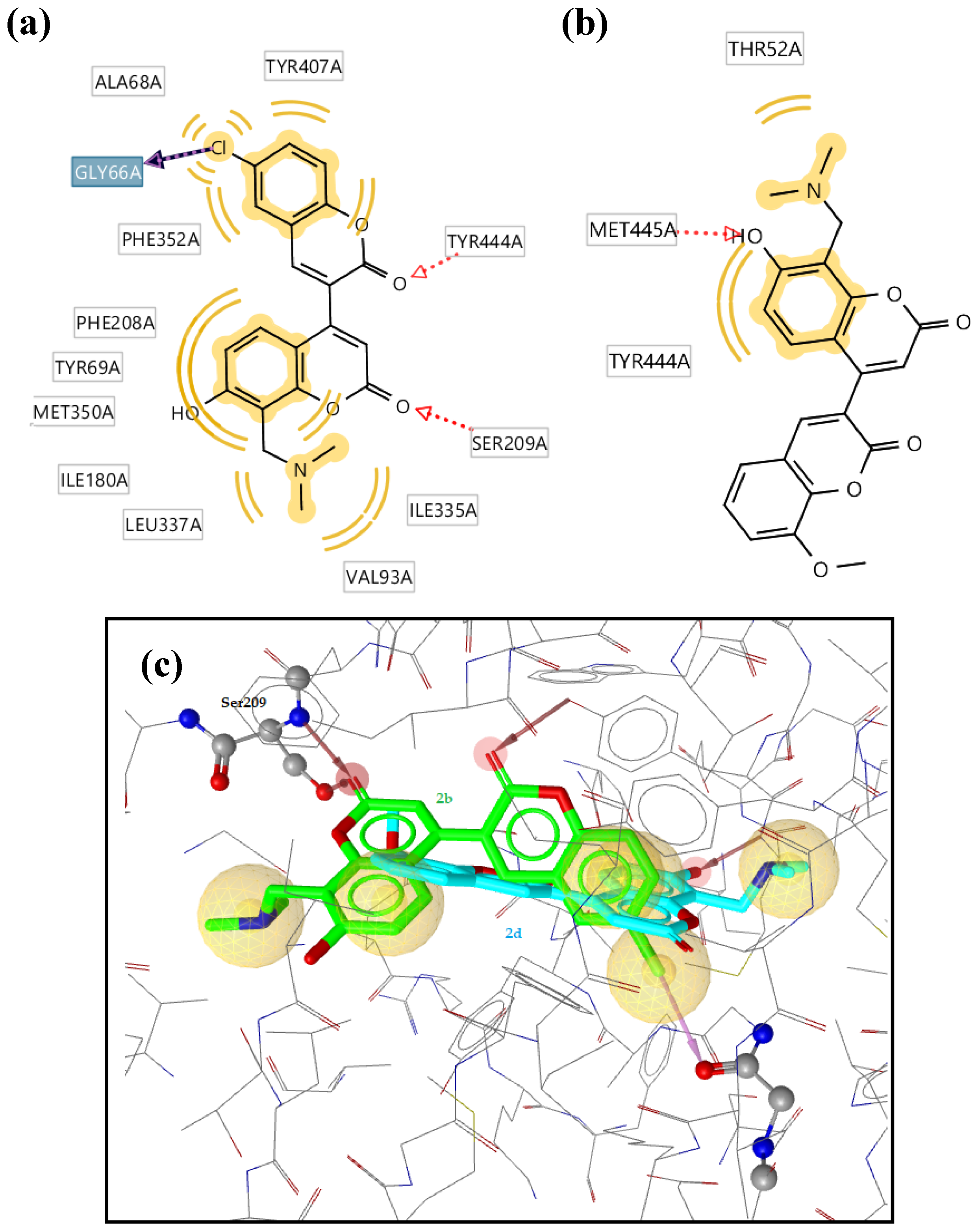

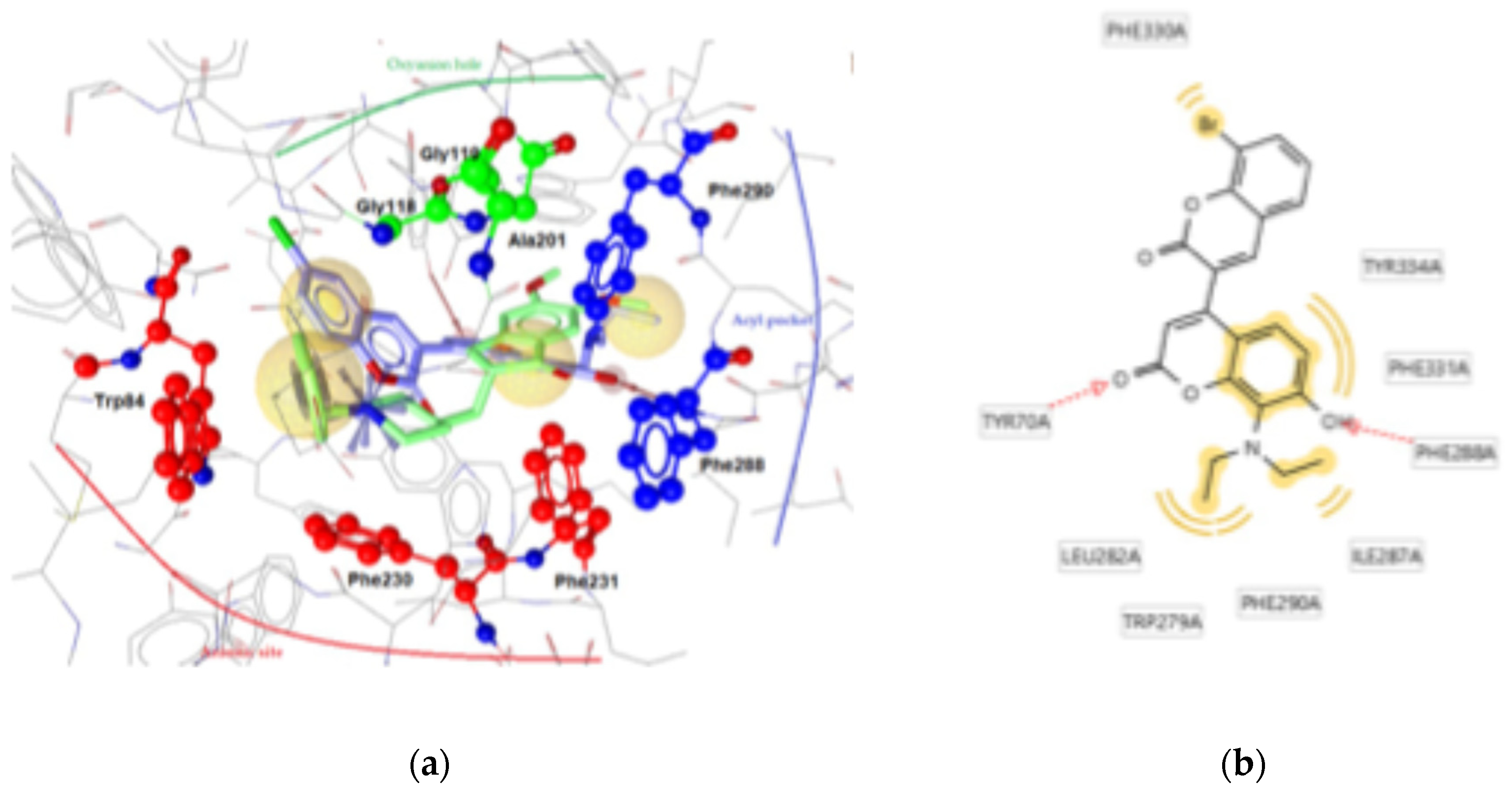

2.2.2. Molecular Docking Calculations

2.3. Physicochemical Properties and Drug-Likeness Assessment

2.3.1. Water Solubility and Lipophilicity Determinations

n = 5, R2 = 0.900, S = 0.110, F = 27.08

Chemoinformatic Assessment of Druglikeness and Bioavailability

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General Methods

3.1.2. Synthesis of 8-((dialkylamino)methyl)-4-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-7-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones(2-8)

3.2. Determination of Kinetic Aqueous Solubility and Lipophilicity

3.3. Enzymes Inhibition Assays

3.3.1. Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidases

3.3.2. Inhibition of Cholinesterases

3.4. Molecular Docking Calculations

3.5. Drug-Likeness and Bioavailability Assessment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.-R.; Huang, J.-B.; Yang, S.-L.; Hong, F.-F. Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, L.C.; Kuehlewein, I.; França, I.V.D.; Da Silva, L.V.; Da Cruz Junior, J.W. Anticholinesterase Agents For Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment: An UpdatedOverview. CMC 2023, 30, 701–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafe, M.R.; Saha, P.; Bello, S.T. Targeting NMDA Receptors with an Antagonist Is a Promising Therapeutic Strategy for Treating Neurological Disorders. Behavioural Brain Research 2024, 472, 115173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-H.; Kim, S.; Nam, Y.; Park, Y.H.; Shin, S.M.; Moon, M. Second-Generation Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Landscape and Future Perspectives. Transl Neurodegener 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multi-Target Drug Design Using Chem-Bioinformatic Approaches; Roy, K., Ed.; Methods in Pharmacology and Toxicology; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4939-8732-0. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.G.; Mandal, P.K.; Maroon, J.C. Oxidative Stress Occurs Prior to Amyloid Aβ Plaque Formation and Tau Phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Glutathione and Metal Ions. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostert, P.L.; Benedetti, M.S.; Tipton, K.F. Interactions of Monoamine Oxidase with Substrates and Inhibitors. Medicinal Research Reviews 1989, 9, 45–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, A.C.; Upadhyay, S.; Paliwal, S.; Saraf, S.K. Privileged Scaffolds as MAO Inhibitors: Retrospect and Prospects. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 145, 445–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sblano, S.; Boccarelli, A.; Mesiti, F.; Purgatorio, R.; De Candia, M.; Catto, M.; Altomare, C.D. A Second Life for MAO Inhibitors? From CNS Diseases to Anticancer Therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 267, 116180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, L.; Catto, M.; Muncipinto, G.; Nicolotti, O.; Carrieri, A.; Rullo, M.; Stefanachi, A.; Leonetti, F.; Altomare, C. A Twenty-Year Journey Exploring Coumarin-Based Derivatives as Bioactive Molecules. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1002547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, L.; Saso, L.; Kostova, I. Antioxidant Activity of Coumarins and Their Metal Complexes. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamati-Konstantina, K.; Dimitra, H.-L. Coumarin Derivatives as Therapeutic Candidates: A Review of Their Updated Patents (2017–Present). Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2024, 34, 1231–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.L.M.; Silva-Reis, R.; Moreira-Pais, A.; Ferreira, T.; Oliveira, P.A.; Ferreira, R.; Cardoso, S.M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Butnariu, M.; Costea, M.A.; et al. Dicoumarol: From Chemistry to Antitumor Benefits. Chin Med 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

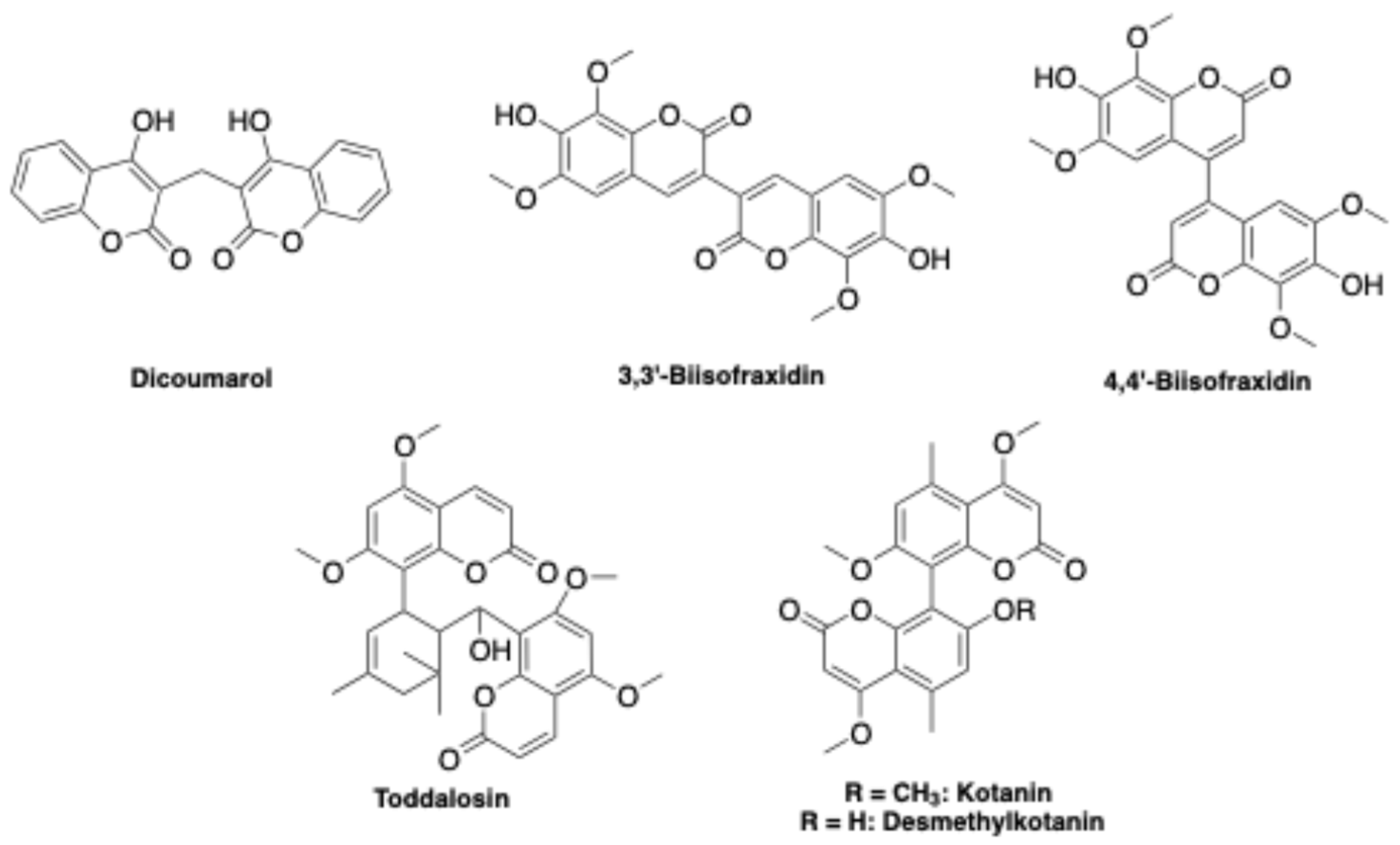

- Ren, Q.-C.; Gao, C.; Xu, Z.; Feng, L.-S.; Liu, M.-L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, F. Bis-Coumarin Derivatives and Their Biological Activities. CTMC 2018, 18, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-T.; Lv, S.-M.; Lu, C.-H.; Gong, J.; An, J.-B. Effect of 3,3′-Biisofraxidin on Apoptosis of Human Gastric Cancer BGC-823 Cells. Trop. J. Pharm Res 2015, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Wang, B.; Ma, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y. Impatiens Balsamina: An Updated Review on the Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 303, 115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Tian, R.; Feng, J.; Yang, N.; Yuan, L. A Systematic Review on Traditional Medicine Toddalia Asiatica (L.) Lam.: Chemistry and Medicinal Potential. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2021, 29, 781–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechi, G.; Klaubert, D.H.; Shank, R.C.; Weinreb, S.M.; Wogan, G.N. Structure and Synthesis of Kotanin and Desmethylkotanin, Metabolites of Aspergillus Glaucus. J. Org. Chem. 1971, 36, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D.; Li, J.; Yang, X.-H.; Zhang, Z.-D.; Luo, X.-X.; Li, M.-K.; Li, X. New Biscoumarin Derivatives: Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Theoretical Study and Antibacterial Activity against Staphylococcus Aureus. Molecules 2014, 19, 19868–19879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougala, B.M.; Samundeeswari, S.; Holiyachi, M.; Naik, N.S.; Shastri, L.A.; Dodamani, S.; Jalalpure, S.; Dixit, S.R.; Joshi, S.D.; Sunagar, V.A. Green, Unexpected Synthesis of Bis-Coumarin Derivatives as Potent Anti-Bacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 143, 1744–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Chang, G.; Lin, D.; Xie, H.; Sun, H.; Li, Z.; Mo, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z. 3,3’-((3,4,5-trifluoropHenyl)Methylene)Bis(4-Hydroxy-2H-Chromen-2-One) Inhibit Lung Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, R.M.; Hammoda, H.M.; El-Gazzar, N.S.; Ibrahim, R.S.; Sallam, S.M. Exploring the Anti-Obesity Bioactive Compounds of Thymelaea Hirsuta and Ziziphus Spina-Christi through Integration of Lipase Inhibition Screening and Molecular Docking Analysis. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 27167–27173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.X.; Huong, T.T.; Khanh, P.N.; Hung, N.P.; Loc, V.T.; Ha, V.T.; Quynh, D.T.; Nghi, D.H.; Hai, P.T.; Scarlett, C.J.; et al. In Vitro and in Silico Study of New Biscoumarin Glycosides from Paramignya Trimera against Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE-2) for Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2024, 72, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.-X.; Mouscadet, J.-F.; Chiang, C.-C.; Tsai, H.-J.; Hsu, L.-Y. HIV-1 Integrase Inhibition of Biscoumarin Analogues. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 54, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, M.S.; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani, M.; Kiani, M.; Ranjbar, P.R.; Zabihi, E.; Pourbagher, R.; Rahimi, R.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Biglar, M.; Larijani, B.; et al. Biscoumarin-1,2,3-Triazole Hybrids as Novel Anti-Diabetic Agents: Design, Synthesis, in Vitro α-Glucosidase Inhibition, Kinetic, and Docking Studies. Bioorganic Chemistry 2019, 92, 103206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, D.; Bustamante, L.; Segura-Aguilar, J.; Goiny, M.; Herrera-Marschitz, M. Effects of the DT-Diaphorase Inhibitor Dicumarol on Striatal Monoamine Levels in L-DOPA and L-Deprenyl Pre-Treated Rats. neurotox res 2003, 5, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudáčová, M.; Hamuľaková, S.; Konkoľová, E.; Jendželovský, R.; Vargová, J.; Ševc, J.; Fedoročko, P.; Soukup, O.; Janočková, J.; Ihnatova, V.; et al. Synthesis of New Biscoumarin Derivatives, In Vitro Cholinesterase Inhibition, Molecular Modelling and Antiproliferative Effect in A549 Human Lung Carcinoma Cells. IJMS 2021, 22, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.-Y.; Cui, H.; Lu, X.-Y.; Zhang, L.-D.; Ding, X.-Y.; Wu, J.-J.; Duan, L.-X.; Zhang, S.-J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, R.-R. (+/−)-Dievodialetins A−G: Seven Pairs of Enantiomeric Coumarin Dimers with Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Activity from the Roots of Evodia Lepta Merr. Phytochemistry 2021, 182, 112597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, L.; Catto, M.; De Palma, A.; Farina, R.; Cellamare, S.; Altomare, C.D. Discovery of Potent Dual Binding Site Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors via Homo- and Heterodimerization of Coumarin-Based Moieties. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasinyuk, M.S.; Bondarenko, S.P.; Khilya, V.P. Chemistry of 3-Hetarylcoumarins 3*. Synthesis and Aminomethylation of 7′-Hydroxy-3,4′- Bicoumarins. Chem Heterocycl Comp 2012, 48, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.; Stepanchikova, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. PASS: Prediction of Activity Spectra for Biologically Active Substances. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geha, R.M.; Chen, K.; Wouters, J.; Ooms, F.; Shih, J.C. Analysis of Conserved Active Site Residues in Monoamine Oxidase A and B and Their Three-Dimensional Molecular Modeling. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 17209–17216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, D. The FAD Binding Sites of Human Monoamine Oxidases A and B. NeuroToxicology 2004, 25, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, J.S. ESOL: Estimating Aqueous Solubility Directly from Molecular Structure. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevskaya, A.A.; Purgatorio, R.; Borisova, T.N.; Varlamov, A.V.; Anikina, L.V.; Obydennik, A.Y.; Nevskaya, E.Y.; Niso, M.; Colabufo, N.A.; Carrieri, A.; et al. Nature-Inspired 1-Phenylpyrrolo [2,1-a]Isoquinoline Scaffold for Novel Antiproliferative Agents Circumventing P-Glycoprotein-Dependent Multidrug Resistance. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.C.; Carr, P.W.; Frechet, J.M.J.; Smigol, V. Liquid Chromatographic Study of Solute Hydrogen Bond Basicity. Anal. Chem. 1994, 66, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.A.; Camargo, L.C.; Souza, G.M.D.; Mortari, M.R.; Homem-de-Mello, M. Computational Modeling of Pharmaceuticals with an Emphasis on Crossing the Blood–Brain Barrier. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamali, C.; Gul, M.; Gul, H.I. Current Pharmaceutical Research on the Significant Pharmacophore Mannich Bases in Drug Design. CTMC 2023, 23, 2590–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qiang, X.; Song, Q.; Li, W.; He, Y.; Ye, C.; Tan, Z.; Deng, Y. Discovery of 4′-OH-Flurbiprofen Mannich Base Derivatives as Potential Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment with Multiple Inhibitory Activities. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 27, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovik, I.P.; Garazd, M.M.; Khilya, V.P. Modified Coumarins. 14. Synthesis of 7-Hydroxy-[4,3?]Dichromenyl-2,2?-Dione Derivatives. Chem Nat Compd 2004, 40, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, L.N.; Purgatorio, R.; Beloglazkin, A.A.; Tafeenko, V.A.; Reza, R.G.; Levickaya, D.D.; Sblano, S.; Boccarelli, A.; De Candia, M.; Catto, M.; et al. Chemical and Biological Evaluation of Novel 1H-Chromeno [3,2-c]Pyridine Derivatives as MAO Inhibitors Endowed with Potential Anticancer Activity. IJMS 2023, 24, 7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titov, A.A.; Purgatorio, R.; Obydennik, A.Y.; Listratova, A.V.; Borisova, T.N.; de Candia, M.; Catto, M.; Altomare, C.D.; Varlamov, A.V.; Voskressensky, L.G. Synthesis of Isomeric 3-Benzazecines Decorated with Endocyclic Allene Moiety and Exocyclic Conjugated Double Bond and Evaluation of Their Anticholinesterase Activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purgatorio, R.; Candia, M.; Catto, M.; Rullo, M.; Pisani, L.; Denora, N.; Carrieri, A.; Nevskaya, A.A.; Voskressensky, L.G.; Altomare, C.D. Evaluation of Water-Soluble Mannich Base Prodrugs of 2,3,4,5-Tetrahydroazepino [4,3-b]Indol-1(6 H)-one as Multitarget-Directed Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Battistuz, T.; Bhat, T.N.; Bluhm, W.F.; Bourne, P.E.; Burkhardt, K.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.L.; Iype, L.; Jain, S.; et al. The Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2002, 58, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolber, G.; Langer, T. LigandScout: 3-D Pharmacophores Derived from Protein-Bound Ligands and Their Use as Virtual Screening Filters. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cmpd | NR2 | R1 | R2 | MAO-A | MAO-B | AChE | BChE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | NMe2 | H | H | 8.30 ± 0.36 | [36 ± 5] | [22 ± 3] | i.a. |

| 2b | Cl | H | 1.49 ± 0.49 | ~ 10 | ~ 10 | i.a. | |

| 2c | Br | H | 2.23 ± 0.22 | ~ 10 | [20 ± 1] | i.a. | |

| 2d | H | OMe | 11.7 ± 1.3 | [28 ± 3] | [39 ± 9] | [25 ± 3] | |

| 3c | NEt2 | Br | H | 3.04 ± 1.37 | [42 ± 3] | 1.56 ± 0.31 | [37 ± 4] |

| 4a | N(nPr)2 | H | H | [29 ± 6] | [33 ± 1] | [37 ± 3] | [22 ± 3] |

| 4b | H | OMe | [29 ± 5] | [43 ± 5] | 3.05 ± 0.97 | [14 ± 10] | |

| 5a | N(Me)nBu | H | H | [32 ± 3] | [23 ± 3] | [28 ± 3] | [27 ± 2] |

| 5b | Cl | H | 1.85 ± 0.11 | ~ 10 | [25 ± 5] | [17 ± 7] | |

| 5c | Br | H | 2.52 ± 0.70 | ~ 10 | 4.25 ± 0.5 | [25 ± 11] | |

| 5d | H | OMe | [39 ± 4] | ~ 10 | 7.80 ± 1.92 | [40 ± 4] | |

| 6a | N(CH2CH2OMe)2 | H | H | [32 ± 5] | [29 ± 6] | [37 ± 9] | [15 ± 4] |

| 6b | Cl | H | [45 ± 3] | [35 ± 9] | [16 ± 4] | i.a. | |

| 6d | H | OMe | [26 ± 4] | [31 ± 1] | [20 ± 2] | i.a. | |

| 7a | N(iBu)2 | H | H | [27 ± 2] | [28 ± 4] | ~ 10 | ~ 10 |

| 7d | H | OMe | [27 ± 3] | [31 ± 2] | ~ 10 | [34 ± 3] | |

| 8a | N(Me)Bn | H | H | [28 ± 4] | ~ 10 | [40 ± 9] | [31 ± 4] |

| 8b | Cl | H | ~ 10 | [38 ± 3] | [16 ± 6] | i.a. | |

| 8d | H | OMe | [31 ± 4] | [42 ± 3] | ~ 10 | ~ 10 | |

| Clorgiline | 0.0025 ± 0.0002 | 2.51 ± 0.45 | |||||

| Donepezil | 0.051 ± 0.003 | 2.71 ± 0.31 | |||||

| Cmpd | Free energy of binding (kcal·mol-1) a |

H-bonding b | Hydrophobic/ aromatic interactions b |

Ionic interactions b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | -11.38 | Ile207, Ser209, Tyr447 | Phe208, Leu337, Tyr407, Tyr444 | Glu216 |

| 2b | -11.25 | Ser209, Tyr444 | Ala68, Tyr407, The352, Phe208, Tyr68, Met350, Ile180, Val93, Ile335 | - |

| 2d | -7.62 | Met445 | Thr52, Tyr44 | - |

| 4a | -10.06 | Tyr69, Ser209, Tyr407 | Phe208, Val303, Ile335, Phe352, Tyr444, Met445 | Tyr407 |

| 5a | -7.82 | Ser209, Ile207 | Leu97, Phe208, Leu337 | - |

| 5b | -10.98 | Ser209, Tyr444 | Tyr68, Ala68, Ile180, Phe208, Met350, Ile335 | - |

| Moclobemide | -8.92 | Ser209, Tyr444 | Leu97, Phe208, Ile325, Ile335, Leu337 | - |

| Cmpd | Free binding energy (kcal·mol-1) a |

H-bonding | Hydrophobic/aromatic interactions b | Ionic interactions b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | -5.12 | - | Phe331, Tyr334 | - |

| 2c | -2.13 | - | - | - |

| 3c | -9.15 | Tyr70, Phe228 | Phe330, Phe331, Tyr334, Leu282, Trp279, Ile287, Phe290 | - |

| 4d | -7.15 | Tyr70 | Trp279, Phe290 | - |

| 5c | -8.02 | - | Trp84, Trp279, Phe290 | - |

| 5d | -8.51 | Trp84 | Trp84, Tyr279, Ile287, Phe290 | - |

| Donepezil | -9.53 | - | Trp84, Ile144 | Phe330, Trp84 |

| Cmpd | Solubility (mol/L) | Lipophilicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calc. a | Exp. b | Log Pcalc c | Log k’w d | |

| 2a | 8.79·10-5 | 1.83·10-4 | 2.96 | 2.11 |

| 2b | 2.26·10-5 | 1.47·10-4 | 3.45 | 2.45 |

| 2c | 1.08·10-5 | 1.41·10-4 | 3.58 | 2.65 |

| 2d | 7.49·10-5 | 1.96·10-4 | 2.94 | 2.32 |

| 3c | 3.69·10-6 | 1.81·10-4 | 4.26 | 2.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).