Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

Experimental Design

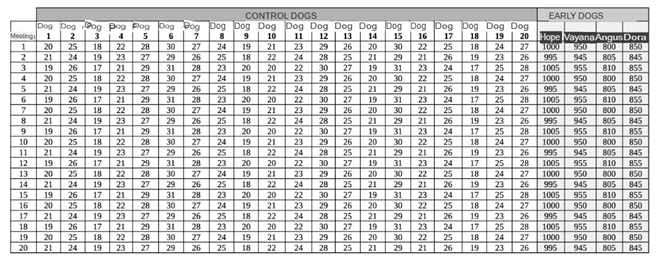

Interventions

- Imprinting phase: From day 25 onwards, the puppies began to search for food in open spaces, gradually expanding the area and complexity of their searches. The aim was to reinforce olfactory discrimination in environments with multiple distractions (noises, smells from other people and objects).

- Olfactory Association: During weaning, the puppies were exposed to six different microtrace odors of explosives, and their response was continuously evaluated.

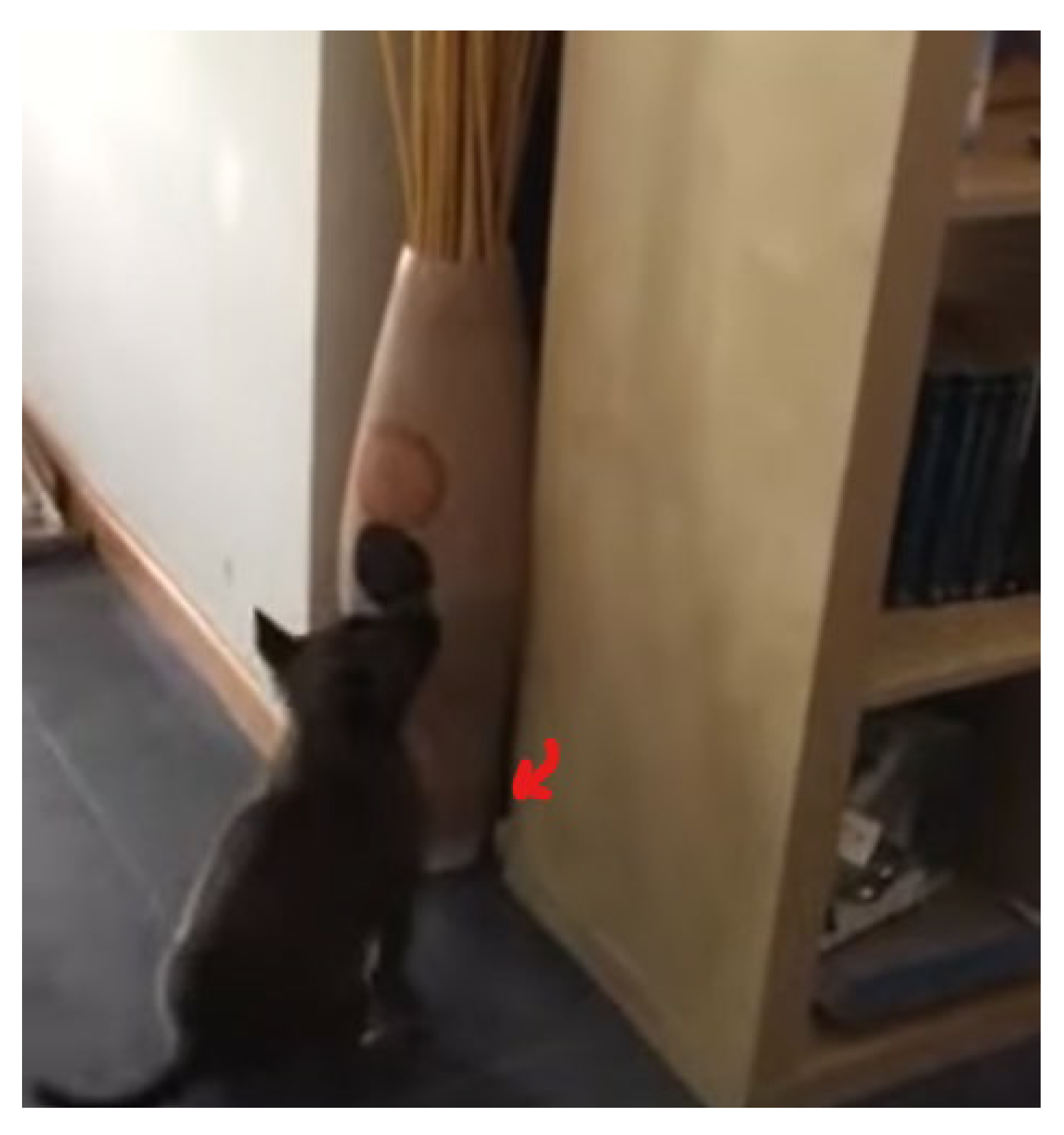

- Search Tests: Starting at 2 months of age, the “point-to-point” exercise was implemented, where the puppies had to identify the container holding the target explosive, avoiding distractors. The sessions were progressively made more complex as the puppies demonstrated a higher level of skill.

Procedure

| PUPPY AGE | OBSERVED CAPABILITIES | COMPARISON WITH STANDARD PUPPIES |

|---|---|---|

| 4 months | Locate substances associated in various search situations: - in free search - in point-to -point - in surprise exercises |

The substance detection skills at 4 months significantly exceed the standard neurological capabilities of a puppy of that age, which would typically be in the early stages of cognitive and exploratory development. |

| 5 months | Search in three modes equivalent to an adult dog (10-18 months): - greater tracking security - greater effectiveness in identifying substances (less time) - lower level of false positives or negative failures. |

This level of detection skill at 5 months is remarkably advanced compared to the typical neurological capabilities of a standard puppy of that age, which would still be in the early stages of learning and development. |

| 16 months | Passed the AESA certification for explosive detection dogs, a very demanding test at the European level. | The ability to pass such a rigorous certification at 16 months demonstrates an extremely advanced level of detection skill, far surpassing the standard neurological capabilities of a puppy of that age, which would still be in a phase of cognitive development and learning. |

- Operant conditioning learning:

- Modeling-based learning:

- Learning by trial and error:

- Social learning:

- Environmental variables:

- Emotional variables:

- Primary reinforcements:

- Secondary reinforcements:

- Intermittent reinforcements:

Results Evaluation

- Tightness factor: ability to smell target samples inside a container whose interior is not easily accessible and with a low level of leakage for volatile substances.

- Work endurance: time that puppies maintained their detection capabilities without fatigue. It is the time the dog maintains its detection capabilities in optimal conditions without fatigue, boredom, or frustration altering the results in the work session. Generally, in canine units, it is considered that a dog is not able to maintain its performance at 100% in sessions lasting beyond 30 minutes.

- Detection rate: proportion of correct identifications of explosives. It allows us to evaluate the dog’s level of concentration when detecting its target in relation to the effectiveness of its search.

- Reaction distance: maximum distance at which puppies could detect the explosive. It is the greatest possible distance at which the dog reacts to the smell of the target sample. It depends on the search target, environmental conditions, air stability, and the dog’s physiological state at the time of the exercise. Anecdotal reports from trainers say that the detection distance can reach up to 5 meters, suggesting the presence of traces in the air as well as on the ground.

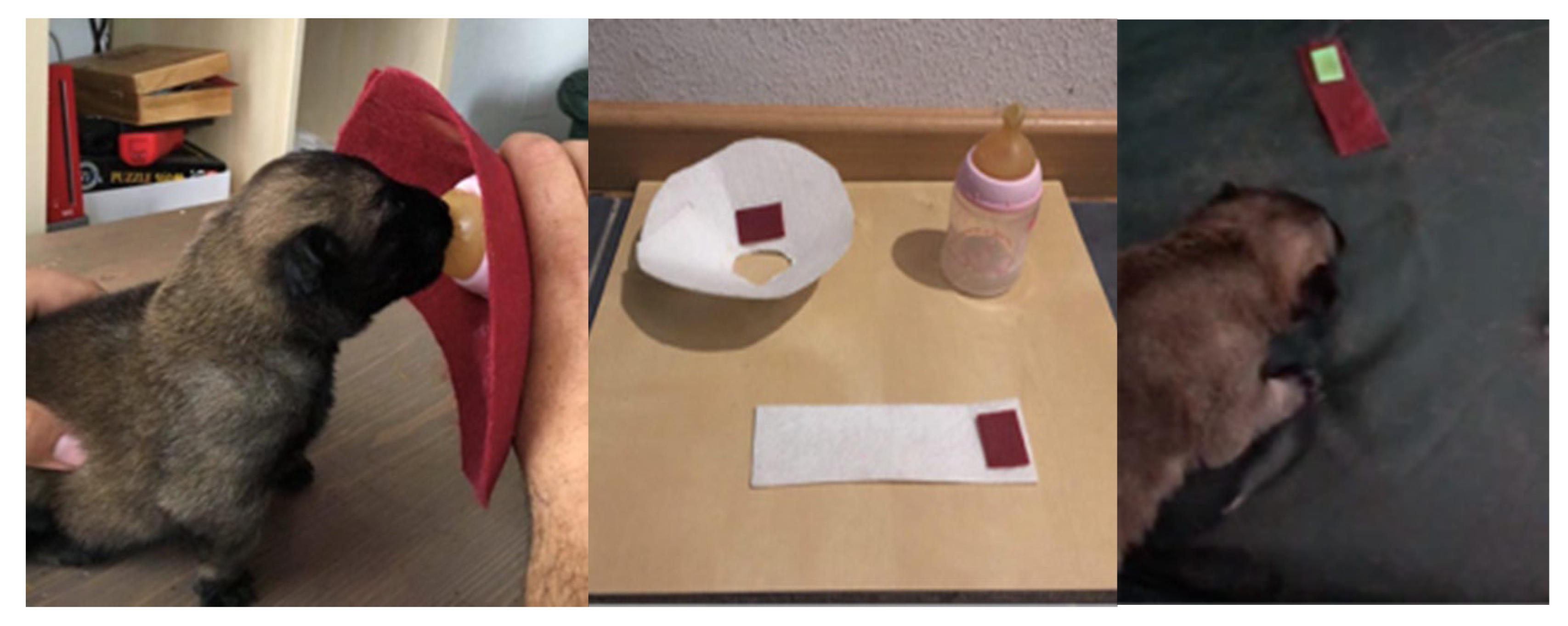

Results

Sealing Factor

|

Dog |

Type |

Evidence Realized | Positive Detected | Detection Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Dog 1 | Control | 100 | 25 | 25 |

| Control Dog 2 | Control | 100 | 22 | 22 |

| Control Dog 3 | Control | 100 | 20 | 20 |

| Control Dog 4 | Control | 100 | 28 | 28 |

| Control Dog 5 | Control | 100 | 24 | 24 |

| Control Dog 6 | Control | 100 | 26 | 26 |

| Control Dog 7 | Control | 100 | 23 | 23 |

| Control Dog 8 | Control | 100 | 21 | 21 |

| Control Dog 9 | Control | 100 | 19 | 19 |

| Control Dog 10 | Control | 100 | 27 | 27 |

| Control Dog 11 | Control | 100 | 20 | 20 |

| Control Dog 12 | Control | 100 | 25 | 25 |

| Control Dog 13 | Control | 100 | 24 | 24 |

| Control Dog 14 | Control | 100 | 22 | 22 |

| Control Dog 15 | Control | 100 | 21 | 21 |

| Control Dog 16 | Control | 100 | 23 | 23 |

| Control Dog 17 | Control | 100 | 26 | 26 |

| Control Dog 18 | Control | 100 | 20 | 20 |

| Control Dog 19 | Control | 100 | 22 | 22 |

| Control Dog 20 | Control | 100 | 27 | 27 |

| Hope | Learning precocious | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Dora | Learning precocious | 100 | 88 | 88 |

| Vayana | Learning precocious | 100 | 87 | 87 |

| Angus | Learning precocious | 100 | 85 | 85 |

| Statistic | Control Group (0) | Treatment Group (1) | Difference | 95% CI for the Difference | t Value | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Significance Level (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Observations | 20 | 4 | - | - | - | 22 | - |

| Mean | 0.647 | 0.875 | -0.228 | -0.3207 a -0.1353 | -5.1008 | 22 | 0.0000 |

| Standard Error (Std. Err.) | 0.0195 | 0.0104 | 0.0447 | - | - | - | - |

| Standard Deviation (Std. Dev.) | 0.0874 | 0.0208 | - | - | - | - | - |

- Mean: Average of the “Positive Detection Rate” in each group.

- Standard Error (Std. Err.): Measure of the precision of the estimated mean.

- Standard Deviation (Std. Dev.): Measure of the dispersion of the “Positive Detection Rate” values in each group.

- Difference: The difference between the control group mean and the treated group mean is -0.228, indicating that the treated group has a significantly higher detection rate.

- 95% CI for the Difference: 95% confidence interval for the difference between group means, which does not include 0, suggesting the difference is significant.

- t-value: t-statistic, indicating the significance of the observed difference between means. A t-value of -5.1008 suggests a highly significant difference.

- Degrees of Freedom (df): Number of degrees of freedom associated with the t-test.

- Significance Level (p-value): A p-value of 0.0000 indicates that the difference is statistically significant.

Reaction Distance

|

| Estadístico | Grupo Control (0) | Grupo Tratado (1) | Diferencia | IC 95% para la Diferencia | Valor t | Grados de Libertad (df) | Nivel de Significancia (p-valor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Número de Observaciones | 20 | 4 | - | - | - | 22 | - |

| Media | 23.895 | 901 | -877.105 | -914.8548 a -839.3552 | -48.1858 | 22 | 0.0000 |

| Error Estándar (Std. Err.) | 0.8569 | 44.7388 | 18.2026 | - | - | - | - |

| Desviación Estándar (Std. Dev.) | 3.8322 | 89.4777 | - | - | - | - | - |

- Mean: Average of the “Reaction Distance” in each group.

- Standard Error (Std. Err.): Measure of the precision of the estimated mean.

- Standard Deviation (Std. Dev.): Measure of the dispersion of the “Reaction Distance” values in each group.

- Difference: The difference between the mean of the control group and the treated group, which is extremely large (-877.105), indicating that the treated group has a significantly greater reaction distance.

- 95% CI for the Difference: 95% confidence interval for the difference between the group means.

- t Value: t statistic, indicating the significance of the observed difference between the means. A t value of -48.1858 suggests an extremely significant difference.

- Degrees of Freedom (df): Number of degrees of freedom associated with the t-test.

- Significance Level (p-value): A p-value of 0.0000 indicates that the difference is highly significant.

- Value t: -48.1858

- p-value: 0.0000 (highly significant)

Work Resistance

- Value t: -5.1008

- p- value: 0.0000 (highly significant)

Positive Detection Rate

- Valor t: -5.1008

- p-valor: 0.0000 (highly significant)

Discussion

Conclusions

Statement on Bioethics and Animal Welfare

Conflict of Interest

References

- Ackerman, P. Intelligence, personality, and interests: Evidence for overlapping traits. Psychological Bulletin 1997, 121, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.R.; Wiekamp, M.D. The canine vomeronasal organ. Journal of Anatomy 1984, 138, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, C.; Bekoff, M. (1999). Species of mind: The philosophy and biology of cognitive ethology. MIT Press.

- Barnett, S.A. (1963). A study in behaviour. Methuen and Co.

- Bateson, P. How do sensitive periods arise and what are they for? Animal Behaviour 1979, 27, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, C.L. Periods of early development and the effects of stimulation and social experiences in the canine. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research 2009, 4, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, F.A.; Jaynes, J. Studies on the development of olfactory preferences in dogs. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 1956, 49, 623–628. [Google Scholar]

- Bertenthal, B.I.; Campos, J.J. New directions in the study of early experience. Child Development 1987, 58, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellví Guimerá, J.L. Effectiveness in dog detection in the military: Proposal for an evaluation standard. Sanidad Militar 2019, 75, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Diezt, L.; et al. The importance of early life experiences for the development of behavioural disorders in domestic dogs. Behaviour 2018, 155, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A. (1997). Confort y bienestar de los carnívoros domésticos. Obtenido de. Available online: http://www.aamfe.org.ar/confort.html.

- Fugazza, C.; Miklósi, Á. Deferred imitation and declarative memory in domestic dogs. Animal Cognition 2014, 17, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furton, K.G.; Caraballo, N.I.; Cerreta, M.M.; Holness, H.K. Advances in the use of odour as forensic evidence through canine chemical and instrumental analysis. Forensic Science International 2015, 251, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, H. (1994). Probability of detection for search dogs or how long is your shadow? Response Magazine, Winter 1994.

- Gazit, I.; Terkel, J. Explosives detection by sniffer dogs following strenuous physical activity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2003, 81, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretchmer, A.E.; Fox, M.W. Effects of odor stimulation and deprivation on olfactory discrimination learning in puppies. Behavioral Biology 1975, 13, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, N.J.; Smith, D.W.; Wynne, C.D.L. Training and generalization of substance detection by dogs: Learning forgetting and application to real-world detection. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2016, 23, 835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, E.S.E. (1968). Adaptation of domestic animals. Lea & Febiger.

- Hepper, P.G.; Wells, D.L. Perinatal olfactory learning in the domestic dog. Chemical Senses 2006, 31, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsch, O. Inheritance of innate, acquired, and pathological behavior. Therios 1991, 90, 266–268. [Google Scholar]

- Irene, et al. The vomeronasal organ of wild canids: The fox (Vulpes vulpes) as a model. Journal of Anatomy 2020, 237, 890–906.

- Johnson, A.; Josephson, R.; Hawke, M. Clinical and histological evidence for the presence of the vomeronasal (Jacobson’s) organ in adult humans. The Journal of Otolaryngology 1985, 14, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kalikow, T.J. Konrad Lorenz’s ethological theory: Explanation and ideology 1938–1943. Journal of the History of Biology 1983, 16, 39–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfer, W.G. The Rorschach and old age. Journal of Personality Assessment 1974, 38, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.Z. (1950). Cuando el hombre encontró al perro. Tusquets.

- Monroy, E. (2001). Initiation to work and puppy training. Obtained from: http://www.aapoa.com.ar/articulo/inicacho.

- Navarrete, A. (2004). The imprinting period in domestic canids (Canis familiaris): Literature review. Austral University of Chile.

- Oliveira, M.L.; Norris, D.; Ramírez, J.F.M.; Peres, P.; Galetti, M.; Duarte, J.M. Dogs can detect scat samples more efficiently than humans: An experiment in a continuous Atlantic forest remnant. Zoología 2012, 29, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pageat, P. (2000). Dog Behavior Pathology. Pulso Ediciones.

- Parker, H.; et al. Genetic structure of the purebred domestic dog. Science 2004, 304, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.J.; Mellor, D. Early olfactory stimulation of detection dogs and its impact on search performance. International Journal of Comparative Psychology 2011, 24, 443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez del Hierro, F.; Véa Baró, J. (1997). Ethology: Biological Bases of Animal and Human Behavior. Pirámide Editions.

- Polgár, Z.; Miklósi, Á.; Gácsi, M. Strategies used by pet dogs for solving olfaction-based problems at various distances. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0131610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; et al. Social learning in dogs: The effect of a human demonstrator on the performance of dogs in a detour task. Animal Behaviour 2001, 62, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; et al. Interaction between individual experience and social learning in dogs. Animal Behaviour 2003, 65, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarría-Echegaray, P.; et al. The vomeronasal organ: Anatomic study of prevalence and its role. Revista Otorrinolaringología y Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello 2014, 74, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, B. (2007). Konrad Lorenz and the mythology of science. In A. Dave (Ed.), What are animals to us? Approaches from science religion folklore literature and art (pp. 269–276). University of Tennessee Press.

- Settles, G.S.; Kester, D.A. (1998). The external aerodynamics of canine olfaction. In F. G. Barth, J.A.C. Humphrey, & T. W. Secomb (Eds.), Sensors and sensing in biology and engineering (pp. 323–335). Springer.

- Sire, M. (1968). La vida social de los animales. Martínez Roca.

- Slabbert, J.M.; Rasa, O.A. Observational learning of an acquired maternal behaviour pattern by working dog pups: An alternative training method? Applied Animal Behaviour Science 1993, 53, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabbert, J.M.; Odendaal, J.S.J. Early prediction of adult police dog efficiency: A longitudinal study. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 1999, 64, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Shields, W.; Washburn, D. The comparative psychology of uncertainty monitoring and metacognition. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2003, 26, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kloot, W. (1968). Behavior. Holt Rinehart and Winston.

- Vaz Ferreira, R. (1984). Ethology: The biological study of animal behavior. Organization of American States.

- Véa Baró, J.J.; Colell Mimó, M. (1997). Ethology. University of Barcelona Editions.

- Vicedo, M. The father of ethology and the foster mother of ducks: Konrad Lorenz as an expert on motherhood. Isis 2009, 100, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, H.F.; Russell, M.J. Olfactory communication and the mother-young relationship in dogs (Canis familiaris) and other mammals. Journal of Comparative Psychology 1983, 97, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).