1. Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a highly aggressive subtype lacking estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2 receptors), accounting for approximately 15–20% of all breast cancer cases [

1]. It is characterized by a high rates of recurrence and distant metastasis and by the most challenging breast cancer subtype to treat due to the lack of effective targeted therapies [

2]. Consequently, TNBC patients face a poorer prognosis compared to those with hormone receptor-positive or HER2-amplified tumors [

1,

2]. The absence of approved targeted therapies for TNBC underscores the urgent need for novel treatment strategies [

3,

4]. Currently, chemotherapy remains the standard treatment option for TNBC, but its effectiveness is limited, especially in advanced stages. As a result, there is increasing interest in identifying new therapeutic agents and molecular pathways, often through strategies like drug repurposing, that could provide alternative treatment options for TNBC patients [

2,

9,

30].

The histamine system has gained attention in cancer biology, with early studies noting its relevance in clinical oncology [

31]. Histamine is a biogenic amine that signals through four well-characterized G-protein–coupled receptors (HRH1–HRH4) [

10,

32]. The role of histamine receptor H1 (HRH1) in breast cancer is complex and not fully elucidated. Some studies suggest that elevated HRH1 expression is linked to poor clinical outcome and angiogenesis [

5,

6,

7], while other reports and databases suggest its significance across different subtypes is still being explored [

33]. Many H1-antihistamines, such as ebastine and terfenadine, have known off-target effects that are independent of their primary histamine-blocking function [

9,

11,

12]. For example, terfenadine, an H1 antagonist, has been shown to induce apoptosis in basal breast cancer cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway [

8]. These findings suggest that the anti-tumor activities of H1-antihistamines may involve non–histamine-mediated mechanisms. Although these findings nominate HRH1 as a potential target in TNBC, its precise role remains a point of interest for further investigation [

33].

In this context, azelastine, a second-generation HRH1 antagonist widely used as an anti-allergy drug, has also been reported to exert anti-proliferative actions in various cancer cells [

13,

34]. H1-antihistamines like azelastine are classified as cationic amphiphilic drugs (CADs) due to their specific chemical structure, which include ionizable hydrophobic aromatic rings and hydrophilic side chains containing amine functional groups [

11,

12,

33]. This structure enables them to easily penetrate cell membranes. Beyond its anti-allergic effects, recent studies have shown that azelastine’s anticancer effects are often mediated through its action as a CAD. Notably, previous reports have shown that azelastine strongly inhibited colorectal cancer cell proliferation and mitochondrial fission both in vitro and in vivo by directly targeting ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1), thereby interfering with downstream oncogenic signaling (IQGAP1–ERK–Drp1 pathway) [

25] and it induces anticancer effects through ARF1 activation in colon cancer cells [

25,

35]. These findings reveal that azelastine can target ARF1, a small GTPase involved in vesicular trafficking, rather than HRH1 blockade to suppress tumorigenesis.

ARF1 plays a central role in intracellular trafficking, Golgi structure maintenance, and mitogenic signaling, and it has recently emerged as a key regulator of tumor progression, with its therapeutic potential being actively explored [

20,

24,

28]. The CAD-associated pathway regulating ARF1 activation has been implicated in cancer cell growth, migration, and survival [

27]. High ARF1 expression is observed in aggressive breast cancer subtypes, and ARF1 promotes metastatic behavior. For example, Schlienger et al. showed that ARF1 is highly expressed in advanced breast tumors, and that ARF1 overexpression drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, proliferation, and chemoresistance [

21]. Its role in regulating cancer cell migration and invasion is a subject of significant research [

22]. Conversely, ARF1 knockdown in breast cancer models impairs primary tumor growth and markedly reduces lung metastases, highlighting its role in cellular trafficking and cancer progression [

23,

29]. In fact, ARF1 is the most frequently amplified ARF family member in breast cancer, and its depletion suppresses metastatic dissemination in mice and zebrafish models [

26]. The modulation of ARF1 and its downstream signaling, such as the PI3K-AKT pathway, establishes it as a pro-metastatic signaling hub in breast and other cancers [

19,

36,

37].

Here, we investigated whether azelastine exerts anticancer effects in TNBC and examined whether these effects are mediated through HRH1 antagonism or its activity as a CAD. This study is the first to suggest the possibility that the HRH1 antagonist azelastine may exert anticancer effects as a CAD in TNBC, providing important mechanistic evidence.

3. Discussion

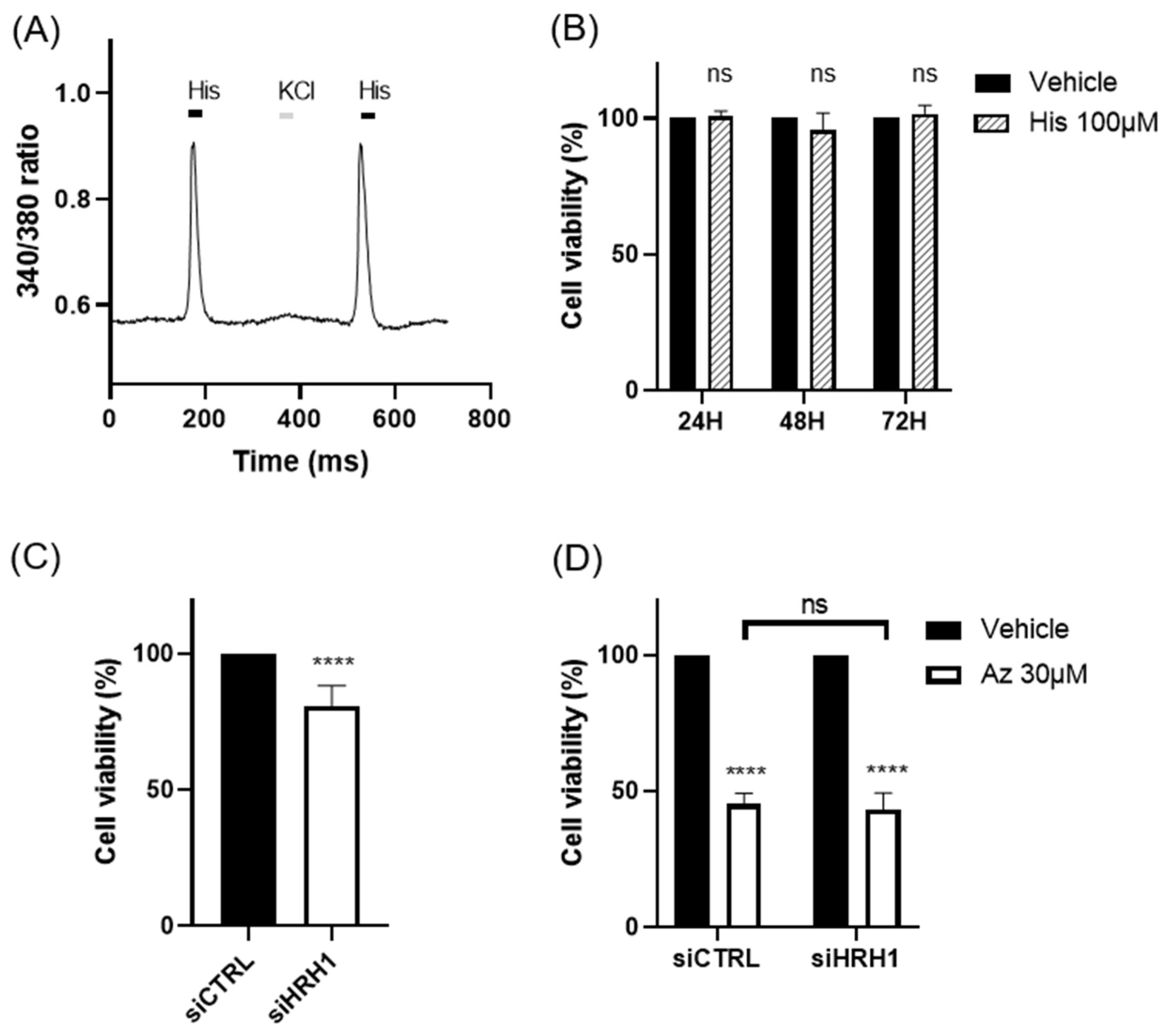

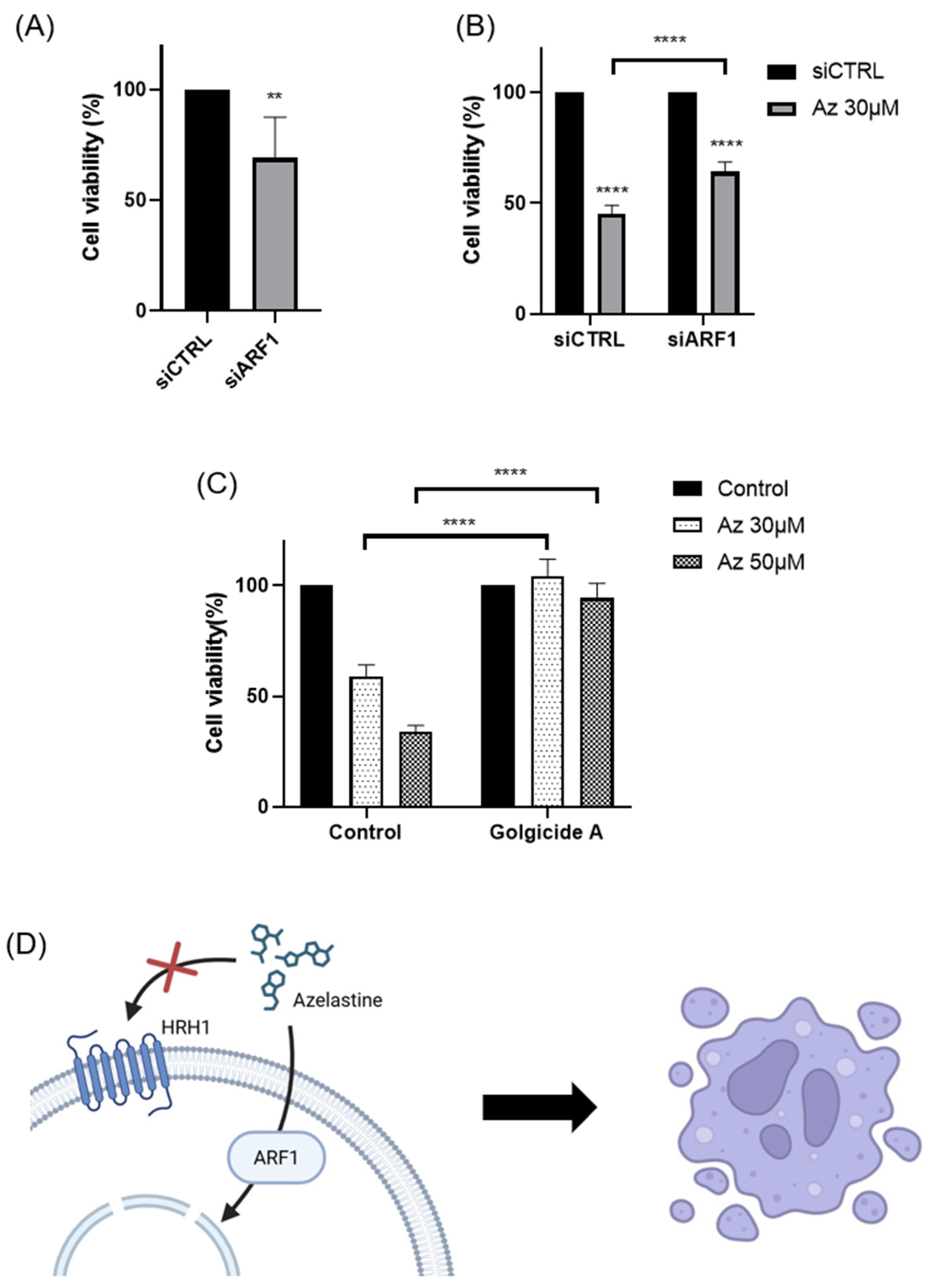

Our findings demonstrate that azelastine, a clinically approved antihistamine, and its metabolite N-desmethyl azelastine potently inhibit the viability of the TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231 through an ARF1-dependent mechanism. Treatment with azelastine resulted in a significant, dose- and time-dependent reduction in cell viability. Notably, these cytotoxic effects were unaffected by HRH1 knockdown and were not reproduced by histamine stimulation, indicating that azelastine acts independently of canonical HRH1 signaling. Mechanistically, co-treatment with GCA, a selective ARF1 inhibitor, completely rescued cell viability, and ARF1 knockdown via RNA interference significantly attenuated azelastine-induced cytotoxicity, increasing cell viability from ~45% in control siRNA-transfected cells to nearly 64% in ARF1-silenced cells. These results demonstrate that ARF1 activity is essential for azelastine’s cytotoxic effect. In our additional studies, azelastine also reduced viability in the BT-549 cell line, another TNBC subtype, by 34.37 ± 4.8 % of cell viability after 72 hours at 30 μM (unpublished data), comparable to the effect observed in MDA-MB-231. Although further validation in BT-549 was not performed, these findings suggest potential efficacy across different TNBC subtypes. Collectively, these findings support the conclusion that azelastine induces cytotoxicity through a non-canonical mechanism involving ARF1 rather than histamine receptor blockade, and may represent a promising therapeutic candidate for TNBC, a disease subtype notorious for its aggressive nature and lack of effective molecularly targeted therapies [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The role of HRH1 in breast cancer is complex, with our findings contributing a new perspective to a varied body of literature. While some previous studies reported that elevated HRH1 expression correlates with poor prognosis in certain breast cancer contexts [

5,

6,

7] and that its pharmacological inhibition can induce apoptosis [

8], our results show that HRH1 is downregulated in the broader breast cancer patient cohort and that its expression has no clear correlation with survival in TNBC. Moreover, our functional assays confirmed that neither HRH1 knockdown nor histamine stimulation affected azelastine’s cytotoxicity. These findings, together with the complete reversal of azelastine’s effect by ARF1 inhibition, strongly suggest that HRH1 is not the primary mediator of azelastine’s anticancer mechanism in this TNBC model. This interpretation aligns with an emerging paradigm where H1-antihistamines exert “off-target” antitumor effects through mechanisms unrelated to histamine receptor signaling [

9,

10]. For example, the antihistamine ebastine was recently shown to inhibit focal adhesion kinase in TNBC, suppressing metastasis [

11,

12]. Such receptor-independent mechanisms may reflect interactions with intracellular signaling proteins, highlighting the broader therapeutic potential of this drug class [

13]. Our findings further support this concept, demonstrating that azelastine’s efficacy in TNBC does not rely on HRH1.

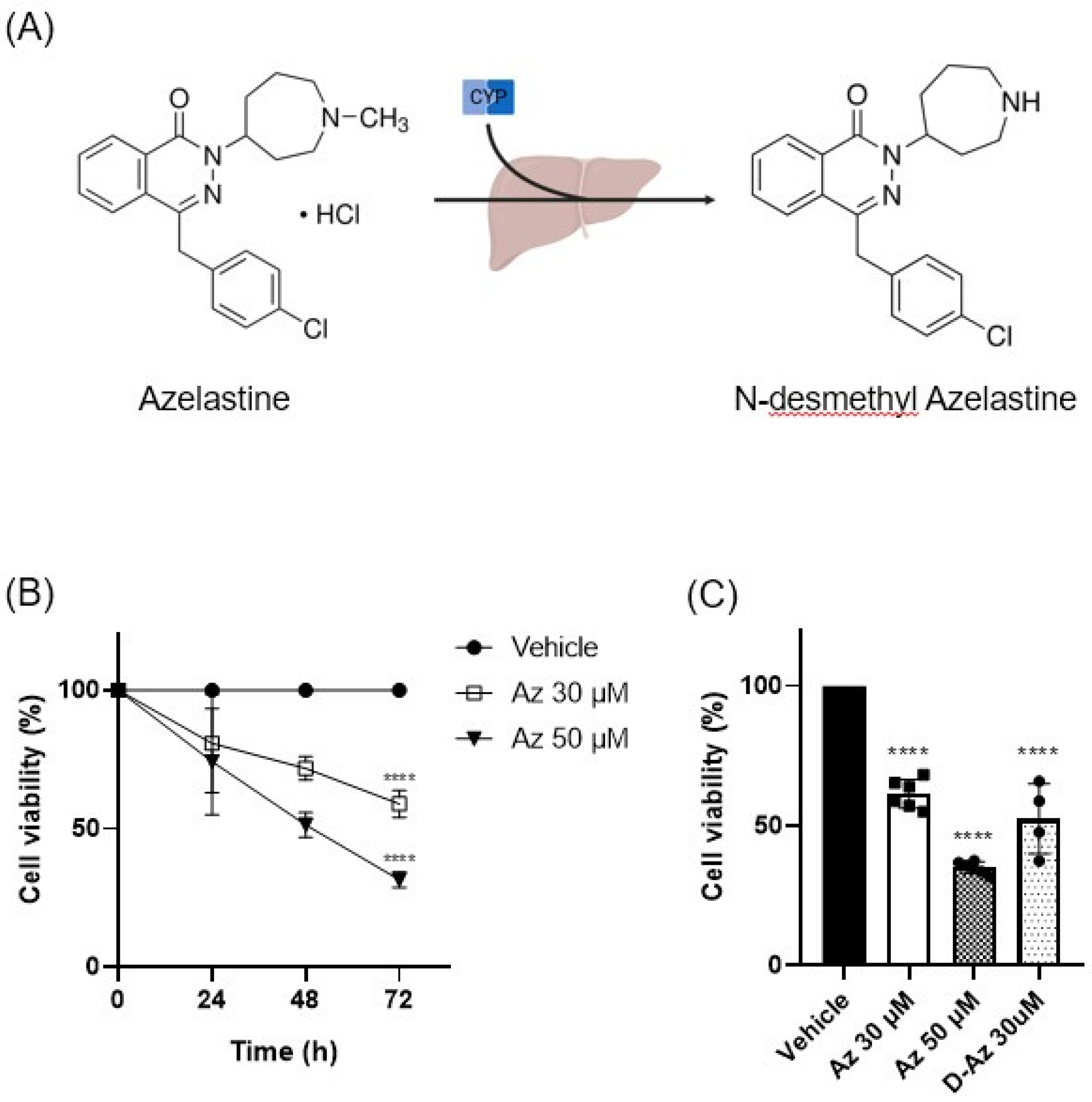

Azelastine is primarily metabolized in the liver by the CYP450 enzyme system to form its major metabolite, N-desmethyl azelastine. While both compounds function as HRH1 antagonists, N-desmethyl azelastine is known to have a lower binding affinity for the receptor (Ki of 9–14 nM) compared to the parent drug, azelastine (Ki of 1.2–1.9 nM) [

14,

15]. To determine if the observed anticancer effects were primarily driven by azelastine or its metabolite, we assessed the cytotoxic potential of both compounds. Our study demonstrates that despite azelastine’s higher binding affinity for HRH1, both compounds exhibit similar cytotoxic effects on TNBC cells (

Figure 1C). This observation, which is not directly correlated with HRH1 binding affinity, supports our hypothesis that the anticancer effects are mediated through a mechanism independent of HRH1 antagonism.

Beyond its role as an HRH1 antagonist, both azelastine and N-desmethyl azelastine are likely to have similar cell membrane permeability as CADs, defined by two key features: a hydrophobic ring structure and a hydrophilic cationic amine group [

16]. When azelastine is metabolized to N-desmethyl azelastine, only a methyl group is removed from the amine [

14,

15]. The N-demethylation of azelastine to form desmethyl azelastine does not alter the fundamental key structural features that allow both compounds to function as CADs. These properties allow CADs to accumulate in lysosomes and potentially induce phospholipidosis, a common off-target effect [

17,

18]. N-desmethyl azelastine retains both the cationic amine and the hydrophobic aromatic rings, suggesting that it also fulfills the structural requirements to function as a CAD. Therefore, we hypothesize that the observed anticancer effects of both azelastine and N-desmethyl azelastine are mediated through their shared properties as CADs, rather than exclusively through HRH1 antagonism. Our data suggest that both compounds, due to their structural similarities as CADs, likely contribute to the overall therapeutic response.

Regarding azelastine’s action as a CAD, our data identifies ARF1 as the critical mediator of azelastine’s cytotoxicity. Importantly, RNAi-mediated ARF1 knockdown partially rescued cell viability despite continued azelastine exposure, reinforcing the view that ARF1 is essential for mediating azelastine’s anti-TNBC effects. This observation is consistent with ARF1’s known pro-tumorigenic roles in various cancers. While the functions of ARF family members can be context-dependent [

19], ARF1 is frequently implicated in processes that drive malignancy, including cell migration, invasion, and chemo-resistance [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Aligning with this predominant view, our analysis of patient datasets did not show a favorable correlation; on the contrary, we found that high ARF1 expression was significantly associated with worse overall and disease-free survival in TNBC patients. This clinical finding provides a strong rationale for our experimental results, where pharmacological inhibition of ARF1 completely abrogated azelastine’s cytotoxic effects. Thus, our study confirms that ARF1 is not only a marker of poor prognosis but also a key functional dependency for TNBC cell survival, making it a compelling therapeutic target [

24].

Mechanistically, our results in TNBC are consistent with recent reports in other cancer types. A pivotal study demonstrated that azelastine can directly bind ARF1, disrupting its activity and downstream oncogenic signaling, such as the ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways [

22,

25,

26]. The parallel between our TNBC results and prior studies in other cancers supports the notion that ARF1 is a conserved and druggable vulnerability across cancer types. Future studies should investigate the relevance of azelastine’s binding site in TNBC and further characterize its downstream signaling effects.

A unique aspect of our study is the identification of the CAD–ARF1 signaling axis as a potential therapeutic target. Previous work has implicated CADs in the activation of ARF1 and regulation of tumor cell survival [

27]. Our data suggest that azelastine’s cytotoxicity in TNBC cells may be mediated through this CAD–ARF1 axis, offering a new direction for therapeutic intervention and underscoring the therapeutic potential of targeting ARF1 [

28,

29]. Further studies are warranted to explore how azelastine interacts with CAD-associated effectors and whether this interaction can be optimized.

Given its established safety profile as an FDA-approved antihistamine, azelastine represents a strong candidate for drug repurposing, a strategy with significant logistical and economic advantages [

30]. Our findings suggest that TNBC tumors with high ARF1 expression may be especially responsive to this approach. This strategy fits within a broader trend of repositioning histamine receptor antagonists for cancer therapy. These findings, together with our own, support the idea that antihistamines may harbor unexplored anticancer potential via structural features that enable engagement with oncogenic signaling proteins [

9]. From a drug development standpoint, our results underscore the promise of repurposing azelastine as an ARF1-targeting therapy for TNBC. This approach may be rapidly translated into clinical settings. Since azelastine has already passed safety evaluation in humans, early-phase trials in TNBC could be expedited. Moreover, the correlation between ARF1 expression and drug responsiveness suggests that patient stratification based on ARF1 status could enhance therapeutic precision. Future work should explore the utility of azelastine in preclinical TNBC models, including in vivo efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and potential synergy with existing chemotherapies or ARF1-pathway inhibitors.

In conclusion, our study provides compelling evidence that azelastine inhibits TNBC cell viability through an ARF1-dependent mechanism, independent of HRH1 signaling. This effect appears to be mediated via the CAD–ARF1 axis, underscoring a novel therapeutic pathway in aggressive breast cancers (

Figure 5C). By repurposing azelastine to target ARF1, we propose a promising strategy to expand treatment options for TNBC patients. These findings also advance our understanding of histamine receptor antagonists in oncology and highlight ARF1 as a clinically relevant therapeutic target. Further research is needed to validate this approach in vivo and to elucidate the broader applicability of ARF1-targeted interventions across cancer types.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

The TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231 was purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Korea). The cells were cultured under standard conditions at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. According to the supplier’s recommendations, the cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

4.2. Drug Treatment and Reagents

Azelastine hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in DMSO to prepare 100 mM stock solutions, which were diluted to final concentrations of 30 µM and 50 µM in culture medium. Histamine dihydrochloride (100 µM; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and golgicide A (10 µM, ARF1 inhibitor; Sellekchem, USA) were used in designated experiments. Final DMSO concentration was kept below 0.1% in all treatment groups, including vehicle controls.

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at 2 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated for 18 hours to allow stable attachment. After drug treatment for 24, 48, and 72 hours, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (iMark Microplate Reader; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Results were expressed as percentages relative to vehicle-treated controls.

4.4. Calcium Imaging

Calcium responses in the MDA-MB-231 cell line were measured using the fluorescent calcium indicator Fura-2 AM (Invitrogen, USA) dye. Cells were loaded with 5 µM Fura-2 AM in HBSS containing 0.1% Pluronic F-127 for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing, fluorescence was recorded using an inverted fluorescence microscope (BX-70, Olympus, Japan) following stimulation with 100 µM histamine. Fluorescence intensity changes were analyzed using MetaFluor® Software (Version 8.0, Molecular Devices, France).

4.5. RNA Interference

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting human HRH1 (siHRH1) and human ARF1 (siARF1) were purchased as AccuTarget™ Predesigned siRNA from Bioneer (Seoul, Korea). A non-targeting control (siCTRL) was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). The sequences for siHRH1 and siARF1 were 5’-GUAGUUUGGAAAGUUCUUA-3’ and 5’-CUGCAUUCCAUAGCCAUGU-3’, respectively. Cells were transfected with 50 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for siRNA-mediated gene silencing. At 48 hours post-transfection, cells were treated with azelastine (30 µM or 50 µM), and viability was assessed 72 hours later.

4.6. Bioinformatic Analysis of Patient Datasets

HRH1 and ARF1 mRNA expression levels were analyzed in normal breast tissue, tumor tissue, and metastatic tissue using TNMplot (

https://tnmplot.com/analysis/), which utilizes a variety of databases including the TCGA and GTEx datasets. We performed a differential gene expression analysis between tumor, metastatic, and normal tissues. In addition, we used the TCGA breast cancer dataset within the TIMER 2.0 platform (

http://timer.cistrome.org/) to analyze the expression levels of these markers in normal breast tissue, overall breast cancer patients, and different breast cancer subtypes. Survival analysis for TNBC patients was conducted using the Kaplan–Meier plotter method, and the METABRIC-TNBC dataset was used. Patients were stratified into high- and low-expression groups based on median expression values, and overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analyzed using the CTGS (Cancer Target Gene Screening) program (

http://ctgs.biohackers.net/) with a log-rank test.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in at least three independent biological replicates unless otherwise noted. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons were conducted using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, or unpaired Student’s t-test where appropriate. Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.8. Ethics Statement

This study utilized publicly available, de-identified patient data obtained from TCGA, TIMER2.0, and TNMplot databases. As all data were previously collected and anonymized, ethical approval and informed consent were not required under institutional and international guidelines. All experimental procedures using cell lines complied with institutional biosafety and research policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K.J. and S.J.J.; methodology, H.K.J.; validation, S.U.P.; formal analysis, H.J.J. and J.Y.L.; investigation, G.U.J. and E.K.P.; resources, H.K.J. and S.J.J.; data curation, D.C.C and H.J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.U.P.; writing—review and editing, S.J.J.; visualization, S.U.P.; supervision, H.K.J., H.J.J and S.J.J.; project administration, S.J.J.; funding acquisition, S.J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.