1. Introduction

It is generally held that in natural systems the majority of microorganisms are often challenged by stressors of different type and intensity that may suppress their ability to grow or even their basic survival. Correspondingly, microbes have evolved a wide array of protective mechanisms that ensure survival and perpetuation of life in the face of endless variation of environmental threats. However, no matter how sophisticated, intricate and effective these mechanisms are, their capacity to withstand the load of stress always operates within certain limits. Even microbes are neither impervious to shifts in external conditions nor invincible by intense and simultaneous stresses [

1]. So, if the stress is overwhelming the accumulation of cellular damage gets beyond repair, the innate homeostasis is irremediably lost, microbial cells inevitably die, the population drastically declines. Hence, efficient reconstitution of the population density, in the aftermath of catastrophic events, is of prime importance for the maintenance of life in strongly fluctuating environments with episodes of very harsh conditions. And, bearing in mind their commonness and great importance for bio-ecological processes on our planet, it would be, thus, important not only to understand the mechanisms by which microorganisms protect themselves from unfavorable conditions [

2,

3], but also to appropriately recognize their frailness and consider the processes that contribute to the resuscitation of microbial populations in the wake of irresolvable stresses and massive death.

It is precisely within this theoretical context that our recent post-stress regrowth under starvation (RUS) studies have been intellectually motivated, conceptually shaped and experimentally conducted [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Using the yeast-like fungus

Ustilago maydis (

Mycosarcoma maydis) as a model, we have probed a number of primary questions regarding the underlying biology of RUS. As a result, we found that after massive killing,

U. maydis was able to efficiently restore population density as long as there were surviving cells. This recovery was based on numerous multiplications of the survivors, fueled by the intracellular compounds released from the dead or dying cells. Namely, the stress-induced damage of the exposed cells causes leakage of the intracellular biomolecules in quantities sufficient to drive regrowth of the crashed populations nearly to the original cell densities [

4].

Thus, RUS can be conceptualized as comprising two main operations: one destructive, involving viability decay and cellular self-decomposition, and the other constructive, centered on regrowth through nutrient recycling [

5]. Although these two operations jointly serve the same purpose, they are carried out by cells which belong to different physiological categories and perform contrasting tasks, so that the main questions related to these two aspects of RUS are informed by generally different theoretical and analytic concerns. Thus, when pondering the destructive side of RUS, it seems primary to consider the correlation between the type and intensity of stressors and the resulting form of cell death as well as how all this relates to the nutrient quality of the substrates released from the perished cells. On the other hand, recognizing that successful repopulation hinges predominantly on the effective recycling of the released organic material [

4,

6], it becomes crucial for understanding of the constructive aspect of RUS to thoroughly assess the cellular capabilities required for this vital process. In addition, the conceptualization of the future RUS-research should also be guided by eco-evolutionary considerations.

As will be clearer below, though the trajectory of the current study touches on various dimensions of RUS, much of the present work was focused on the issues related to the “destructive” side of RUS. In this regard, there are several key points provided by previous research that are worth mentioning. First, the growth-supporting quality of the dead biomass (sometimes termed necromass) is affected by the mode of killing [

8,

9], and by intensity of the stress suffered [

4], along with the specific type of cell death involved [

10]. As regards the stress-intensity, our experiments indicated that the nutrients freed from the treated cells become more toxic not only with the increased doses of the stressor but also with the extended post-treatment incubation periods [

4]. In addition, an intriguing observation was that the toxicity of the treated cell suspensions could not be fully transferred to the derived cell-free supernatants [

4]. These observations indicated that successful recovery after extensive damage would require not only cellular processes that facilitate the efficient uptake and re-utilization of released materials, but also mechanisms that help mitigate the stress-induced toxicity.

When it comes to the mode of cell death, a rather common observation is that at lower stress intensities the cell dies by programed cell death (PCD), while higher-intensity treatments lead to death by necrosis (see for instance: [

11,

12,

13]). But what is especially noteworthy for this study are the findings that corelate the ways of dying and the nutritive quality of the biomolecules released from the dead cells. Namely, it was demonstrated in the unicellular green alga

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii that the unidentified compounds liberated by programed cell death (PCD) were beneficial for conspecific cell growth, while the material released by non-PCD means, i. e. by cell subjection to sonic waves, was actually detrimental to cells of the same strain [

10]. Interestingly, it was found in a further study that the beneficial effects of the

C. reinhardtii PCD-substrates were species specific, with these substrates even showing growth-suppressive effects on other

Chlamydomonas species (Durand

et al., 2014). Similar results have also been reported in the case of the green microalga

Ankistrodesmus densus [

14]. Again, the identity of the responsible molecules was not examined, but it should not escape attention that extracellular micro-vesicles were suggested as the PCD-materials delivery vehicles that might provide the conspecific PCD-benefits.

The above insights were very helpful both for clarifying the issues and for suggesting new hypotheses to test, thus assisting the present study to be better directed. However, the original impetus came from the finding that the pantothenate-auxotrophic strain UCM350 could, in contrast to what was observed upon exposure to peroxide, successfully repopulate upon suicidal death induced by self-generated hypoxia (SGH), indicating that the peroxide-treatment does and SGH-killing does not significantly impact the coenzyme A (CoA)-resources. The SGH-induced death was discovered recently [

15]; it occurs in water under limited supply of oxygen, due to the

U. maydis’ self-defeating behavior of failing to halt its oxygen-consuming activity, thereby generating a hypoxic environment and accumulation of reactive oxygen species, ultimately suffering a catastrophic loss of viability. Following the implications of the above findings, the first question we asked was the question of whether the nutrients released from cells dying by suicidal death were generally more favorable to growth than the derivatives liberated from cells experiencing other types of death. Relatedly, it was also important to examine whether the cells dying upon SGH are actually undergoing a form of PCD. As the answer to both questions turned out to be affirmative, it was of considerable interest to know whether the products of PCD could overcome the growth-inhibitory effects of a non-PCD necromass. Importantly, the answer was again positive. Lastly, considerations are also given to the question of whether the positive effect of SGH-products might be species specific.

Finally, we want to close this section by a few words about the RUS acronym, clarifying the need for a revised definition. Namely, the RUS was originally used to denote “regrowth (or repopulation) under starvation”. In phrasing it that way, we intended to emphasize the fact that the repopulation occurs in an effectively closed system, i. e. that the regrowth is realized without any external supplementation of nutrients. However, the system internally generates a nutrient supply so that, in the strictest sense, the repopulation is not carried out under starvation. Therefore, here we propose to keep the accepted acronym of RUS while redefining its meaning as to signify “repopulation upon shattering”. This formulation more truly defines the essence of the phenomenon. Namely, the reconceptualization of the acronym expands its meaning well enough to capture the relationship between the devastation of a cellular population and the capacity of the surviving subpopulation to repopulate, connecting the two primary categories for a correct understanding of the whole process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Growth Conditions

Detailed protocols for routine maintenance, cultivation materials and standard conditions used for growing the

U. maydis cells have been published previously [

4,

15]. Unless otherwise indicated, all experiments were performed with overnight cultures grown in YEPS (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% sucrose) using

U. maydis UCM350 (

pan1-1 nar1-6 a1 b1) and UIMG10 (

nar1-6 a1 b1) strains, where

pan, nar, a1 and

b1 indicate auxotrophic requirement for pantothenate, inability to utilize nitrate, and mating type loci, respectively; UIMG10 is identical to UCM350 but with the

pan1-1 allele converted back to the wild-type status, so that it was used as a nominal wild-type control. The

Pan1 (UMAG_10139) gene is located on chromosome 5, contains an ORF of 1299 bp currently annotated as encoding a putative pantoate-beta-alanine ligase, an enzyme involved in pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis. Whole genome sequencing of UCM350 (Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd.) and DNA sequence analysis revealed that the

pan1-1 allele differed from the wild-type allele by a single base pair (T to C) transition at nucleotide position 440, which converts the wild-type serine 147 (TCG) into a leucine (TTG) codon.

Sporisorium reilianum f. sp.

zeae, SRZ2_5-1,

a2b2 and

Sporisorium scitamineum I1,

mat-2 strains (both kindly provided by Prof. Jan Schirawski, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Germany) were propagated at 24 °C (and maintained at 4 °C) on YEPS agar.

2.2. Stress Treatments

Cells were grown in YEPS to early stationary phase (approx. 2 x 108 cells per mL), harvested by centrifugation, washed 3 times in distilled water, resuspended in water at a concentration of 4x107 cells per milliliter and then subjected to various stresses. Oxidative stress was imposed by adding H2O2 in the presence of 10 mM Fe3+-sodium EDTA, effectively catalyzing the Fenton reaction and generation of hydroxyl radicals. Following 10 minute-incubation at 30˚C (with periodic mixing) the treated samples were washed 3 times in water.

For UV treatment, the washed cells (eight milliliters of the suspension placed into a 90mm x 15 mm plastic Petri dish) were exposed to increasing doses of UV light, using a Osram HNS30W G13 UVC - Puritec Germicidal lamp that was about 36 cm above the surface of the liquid, and the radiation intensity was 18.4mJ/cm2, as measured with a UV meter (UV Disc, UV-Technik International Ltd). The dishes were placed on the shaking platform of a seesaw-shaker (MaxQ2000, Thermo Scientific Inc.) and the suspensions were shaken vigorously, at the seesaw frequency of 100 per min.

For Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) treatment, the indicated concentrations were used, and the cell suspensions were incubated for 30-minute at 30°C in a rotary shaker. After incubation, the treated cells were washed three times in water.

The self-imposed hypoxia was induced as described previously [

15]. Briefly, overnight cultures were harvested, washed, and suspended in water, all as described above, except that the suspensions were brought to a cell density of 4x10

8cells/mL. 1mL aliquots of this suspension were dispensed into 1.5 mL-microcentrifuge tubes, leaving in each micro tube 5 mm headspace with limited supply of oxygen. The tubes were sealed by parafilm and incubated simultaneously at 30°C for 24h. After that, the aliquots were pooled together and mixed well to make a homogenous sample, before the cell suspension was split into subsamples for further analysis.

After each of these stress treatments, an aliquot was removed from the mixtures to determine the surviving fractions and the remaining (major) part of the treated suspensions was incubated at 30˚C with agitation typically for 3 days before plating to measure regrowth. In all cases, viability was measured via the spot dilution assay. All experiments were performed in duplicate and reproduced at least three times. If not otherwise specified along the text, results shown in the figures are representative of these determinations.

2.3. Determination of Apoptosis/Necrosis in SGH and Peroxide Treated Cell Suspensions

To assess cell viability and distinguish between viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells in SGH and peroxide treated cell suspensions, Annexin V/PI dual staining was performed using FITC AnnexinV/Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with modifications to accommodate fungal cell wall structure. The cells washed twice with water and brought to a cell density of 4x108 per mL were distributed in 1 mL aliquots into 1.5 mL tubes. The tubes were sealed by parafilm, placed into a 96-well 1.5 mL microtube rack with lid which was then mounted vertically on an oscillating shaker in a 30 °C room. At various time points, individual (single-use) aliquots were successively sampled, the cells were converted into protoplasts and analyzed for PCD and necrosis. After protoplast formation, they were washed with PBS (1.37 M NaCl, 27 mM KCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4, 18 mM KH2PO4) to remove residual enzymes and then resuspended in 1 X Anexin binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl₂, pH 7.4) at a concentration of approximately 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL. To this, 5 µL of Annexin V-FITC conjugate and 2 µL of PI (100 µg/mL final concentration) were added. Cells were incubated for 30 min, at room temperature in the dark, then placed on a glass slide with a glass coverslip and observed under a Leica Confocal Microscope SP8 equipped with LAS AF software (Leica Microsystems). The acquisition of images was performed in sequential mode. Images were obtained from two independent experiments and 300 cells per sample were counted. The results were analyzed by Tukey t-test, using SPSS statistical analysis. The p values more than 0.05 were considered not significant.

2.4. DNA Analysis

Molecular karyotype analysis was performed by contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) gel electrophoresis in 0.5 TBE (45 mmol/L Tris base, 45 mmol/L boric acid, and 1 mmol/L EDTA pH 8) using a 2015 Pulsafor unit (LKB Instruments, Broma, Sweden), for 15 hrs with a switch time of 60 sec followed by 11 hrs with a switch time of 90 sec. Protoplasts from 109 cells were prepared using lysing enzymes (Sigma-Aldrich), embedded in agarose plugs, then digested with Proteinase K at 30˚ for 24 h in a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 1% sodium N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate.

3. Results

3.1. New Insights into the Cellular Mediation of the Stressogenic Impact and the Factors that Might Contribute to the Variance of the Outcomes.

As noted above, this work was spurred by a simple finding. Namely, in the course of our RUS studies we observed that after massive (>5 logs) decline of viability induced by SGH, the auxotrophic strain UCM350 (

pan1-1 nar1-6) could upon reaeration restore the population to nearly the initial cell viability value. That would imply that upon this type of (suicidal) death the dying cells provide a sufficient sum of nutrients (including pantothenate and reduced nitrogen) for the remaining viable cells to successfully renew the population (

Figure 1A). However, it was otherwise in the case when peroxide was used as a stressogenic agent. As depicted in

Figure 1, panel B, the progressive increase in the doses of H

2O

2 was followed by the increased inability of the surviving fractions of cells to revive the population. Namely, while the 0.2% and 0.3% H

2O

2-threated UCM350 cells were still able to recover and proliferate, yielding a significant (by >100 fold) increase in cell density, the regrowth was less to none, the greater the percentage of peroxide was used, i.e., in the range 0.4-0.6%. This defect could be rescued by supplementation of the suspending medium with pantothenate (pan) (a metabolically active component of coenzyme A) at a final concentration of 10 µM (Figure1B).). Indeed, the addition of pantothenate could elicit an almost complete return of viable cell density, even from the catastrophic 5 log reduction incurred by 0.5% and 0.6% H

2O

2. Moreover, while the 0.3% H

2O

2-threated cells (left to recover and multiply without added pantothenate) formed colonies of highly variable size and altered morphology, in the pan-supplemented suspensions all treated cultures regrew back giving rise to colonies that were fairly uniform, indicative of accurate repair and efficient recovery (Figure1 Da). These observations obviously implied that the RUS phenotype exhibited by UCM350 was conferred by the

pan1-1 allele

, i. e., by the mutation in the gene encoding the pantoate-beta-alanine ligase, an enzyme involved in pantothenate (and concomitantly in CoA) biosynthesis. Therefore, it was quite understandable that the phenotype could also be suppressed by supplementation with pantethine (

Figure 1B), a downstream metabolic intermediate in the production of CoA.

In the light of these observations, two questions immediately presented themselves: 1), whether the stark differences observed between SGH and peroxide treatment were manifested exclusively in the case of peroxide, possibly owing to the fact that H

2O

2 is generally very reactive agent capable of damaging a wide assortment of cellular components [

16]; and 2), whether recovery under the paucity of pantothenate leads in UCM350 to genomic instability, a question obviously raised by the above observation that the recovery in unsupplemented medium produced colonies with gross phenotypic alternations. To address the first question, we examined the population recovery after exposure to two genotoxic agents, ultraviolet light (UV) and Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). As shown in

Figure 1C, this examination revealed that the repopulation following UV and MMS-induced killing was, like in the case of peroxide, increasingly dependent on supplementation with pantothenate, the greater the dose of these agents was used, thereby ruling out the idea that the differences observed above were peculiar to a drastic assault by hydrogen peroxide.

To answer the second question, we analyzed the DNA karyotype of individual colonies arising from the UCM350 cells that after 0.3% H2O2-treatment recovered viability in conditions of either with or without external pan-supplementation (Fg.1 Da). As noted above, colonies arising from the pan-supplemented suspension showed no apparent morphological alternations. Consistently, when four independent isolates were taken at random from this cohort, prepared and analyzed on CHEF gels (Fig1.Db), the composition of chromosomal DNAs appeared no different from that of the untreated control. By contrast, there were evident chromosome rearrangements in three out of four independent isolates arising from survivors cultivated in the absence of supplementary pan, suggesting that under this condition the chromosome repair during recovery was inaccurate.

In sum, the results consolidate two conclusions. First, the stressogenic factors used impact the quality of the released substrates in a different way, whereby peroxide, UV, and MMS treatments do, but SGH does not lead to significant degradation of the CoA-resources. Second, it could be concluded that CoA plays an important role in precise repair and efficient recovery following peroxide damage. In addition, the observations provoke an intriguing question of whether the overall nutrient quality of the released substrates, and not only of the CoA resources, is preserved during the decomposition of the cells that died upon SGH? In other words, and reflecting the broader context of RUS studies, are the substrates released from the cells undergoing suicidal, SGH-induced death, generally more beneficial for the surviving cells than the nutrients liberated upon peroxide treatment, and, if they are, whether the reason for that lies in the nature of cell death. Thus, the analyses that follow represent attempts to address these issues.

3.2. Suicidal, SGH-Induced Death Facilitates Production of Derivatives More Favorable to Growth

If we wish to address whether the overall nutrient quality is preserved at a higher level upon SGH-induced death, we may simply compare the growth in SGH-supernatants with the proliferation in supernatants of cultures killed by peroxide. But from the standpoint of environmental realism, it would be more appropriate to assess the growth-effects not only of the supernatants but also of the respective cell suspensions, i.e., of total necromasses. Certainly, the latter conditions would more closely reflect the settings

U. maydis cells may encounter in nature. And this reasoning would also be supported by previous findings that suspensions of peroxide-treated (PT) cells were, for unknown reason, more detrimental to cell growth than the corresponding supernatants [

4]. Relevant in this context is also the observation that in the range of 0.1% to 1.1% PT cell suspensions (PT-CSs) and matching supernatants (PT-SNs),

U. maydis inocula showed progressively increasing growth, achieving the fastest proliferation in 0.5% PT-CS/-SN, after which the growth kinetics starts to progressively decline [

4].

With all this in mind, we decided to compare the growth-effects of both the SGH- and PT-CSs and of the respective SNs. Because our goal was essentially to determine whether SGH-necromass holds a more beneficial substrate capacity, we chose to observe its growth-effects in comparison to the growth-supporting capacity of the 0.5% PT-cells, which, as indicated above, are supposed to produce the best ratio of growth-stimulating to growth-inhibitory substances. Then, in keeping with the aim of observing potential difference in inhibitory effects between SGH-CS and SGH-SN, the samples with 0.6%-CS and -SN were also included as a reference and control. Given that peroxide treatments affect the CoA resources, we nullified this variable by using U. maydis UIMG10 (Pan+) strain and supplementing the samples with pantothenate (10 µM). In order for the nutrient capacity of these substrates to be equal, and since the PT-substrates were prepared at a density of 4x107 cells/mL, the initial (4x108 cells/mL) SGH samples were diluted 10X. The supernatants were derived by centrifuging and filtering out cells through millipore 0.45 μm filters, following 5h of post-treatment incubation at 30°C. Thus, the prepared SGH- and PT-samples were inoculated with fresh UIMG10 cells (at 1x103/mL), incubated at 30°C under continuous agitation and the growth was examined at 8h intervals over the course of 48h.

As can be seen in

Figure 2A, both the SGH-CS and SGH-SN inocula reproduced markedly faster, outpacing even the growth of the next fastest growing, i.e., that of the 0.5% peroxide-SN-inoculum by more than an order of magnitude, during the first 24h time period, consequently reaching their carrying capacity first (at about 32h). This would indicate that the overall nutrient quality, and not only of the CoA resources, is preserved at a higher level in the case of SGH-induced death. Interestingly, very little (if any) difference could be observed between the curves obtained from the SGH-CS and SGH-SN cultures, with SGH-CS inocula growing just as well and sometimes even slightly better than the corresponding SGH-SN cultures. Conversely, and as expected, the shapes of the growth curves of the CS- and SN-cultures prepared using 0.5% PT cells, exhibited clear divergence, which was extended further with increased (0.6%) concentration of peroxide used. Evidently, lag phases observed in the PT CS cultures take longer than lag phases in the corresponding SN-cultures.

Based on these results and in view of the finding that PCD-derivatives were in

C. reinhardtii beneficial for conspecific cell growth (Durand et al., 2011), it was pertinent to determine whether the suicidal, SGH-induced death actually occurs through PCD. It should be noted that in a previous study [

15], it was observed that the SGH-induced death was associated with a marked rise in reactive oxygen species and eventual “laddering-like” DNA degradation, two of the processes that are usually, but not always, correlated with PCD (see [

17], and references therein). For this reason, we wanted to look at this issue in a more critical way, i.e., by probing the phosphatidylserine externalization (using annexin-V staining), which is considered to be one of the strongest markers of PCD. Given that the SGH-conditions are gradually developed with the ongoing incubation, individual (single-use) aliquots were, at various time points, sampled and analyzed for PCD and necrosis using the annexin-V assay in combination with propidium iodide (PI), a DNA staining dye that is commonly used to detect damaged and dead cells in a treated cell population.

As shown in

Figure 2Ba, after 7h into SGH-incubation a substantial number of annexin V-positive cells were observed (13.2%), indicating that, under SGH-conditions,

U. maydis cells are indeed induced to undergo apoptosis. Since at the same time point the culture had only 0.17% of PI-positive cells, the vast majority of the annexin-positive cells could be regarded as being in the early (annexin

pos/PI

neg) apoptotic stage. However, from 7h onward, the number of PI-positive cells increased exponentially, reaching the maximum (practically 100%) at 20h, while the portion of annexin-positive cells remained substantially similar. These data suggest that as in the numerous experimental systems described so far (

U. maydis included, [

18]), the SGH-apoptotic cells progress through distinct phases, from early apoptotic via late apoptotic to necrotic stage. Accordingly, at the 20h time point, the annexin V-positive cells also had to be PI-positive, a prediction that was supported by close microscopic inspection (see

Figure 2Bb, the upper panel). Unlike the situation with SGH, most cells in the 0.5%-PT suspension were necrotic (>99% PI positive).

In sum, the experiments have shown that under SGH-conditions

U. maydis cells do execute PCD form of dying, that the substrates of cells that have undergone PCD are more favorable for growth than the nutrients from a non-PCD necromass, and that our results parallel those reported for

C. reinhardtii [

10]. A further point to note is that growth curves from SGH-CS and SGH-SN cultures coincide rather well, suggesting that the presence of total SGH-necromass does not impose additional stresses to the expanding population.

3.3. Products of PCD can Overcome the Growth-Suppressive Effects of Non-PCD Necromass

At varying levels of intensity, microorganisms are exposed to multiple, even simultaneous stressors that can devastate their populations, generating necromasses of different kind and various growth-promoting quality. Therefore, it was of considerable importance to learn if the PCD-material can overcome the growth-inhibitory effects of a non-PCD necromass. As far as we know, there are no reports on this issue at the moment.

Thus, we started to explore this subject by comparing the growth kinetics of

U. maydis UIMG10 cells challenged by increasing densities of PT cells, suspended either in water, rich medium, or in the 10X diluted SGH (PCD) filtrates. In this initial experiment, we applied five densities of 0.7% PT cells (2x10

7, 4x10

7, 6x10

7, 8x10

7 and 1x10

8 PT cells/mL). In order to be able to normalize YEPS and the 10X diluted PCD filtrate to the same carrying capacity, we performed preliminary testing finding out that we needed to use 100x diluted YEPS. All samples were inoculated with 1x10

3 of untreated cells, incubated at 30°C under vigorous shaking and the growth dynamics was monitored via the spot dilution assay. The results are collectively shown in

Figure 3A.

As expected, a clear growth-inhibitory effect of the necromass was seen in a concentration dependent manner. In the highest densities of PT cells suspended in water, even dying off of the inoculated cells occurred. Remarkably, after 24h and 48h, all the samples supplemented by PCD substrates exhibited an impressive improvement of survival and expansion. To put it rather pointedly, in PCD supernatants inocula could survive and proliferate even at a starting ratio of live to dead cells of 1: 105. Although expressed with much slower kinetics and to a noticeably lower level, 100x diluted YEPS still showed a great capacity to overcome the growth-suppressive effects of PT cells. In essence, this would mean that the overall improvement we observed may significantly be driven by purely (elemental) nutritional effects.

Since the analyses above have shown that the growth curves for SGH-CS and SGH-SN were essentially identical, we wished to know whether they promote mutually similar growth under exposure to PT cells. Also, we wanted to determine how do these SGH cultures compare to unfiltered and filtered 0.5% PT samples. Therefore, we next tested the growth-stimulatory potential of all these substrates in the presence of 0.7% PT cells (4x10

7) and examples of two comparisons are given in Figure3B. On the whole, the results accord very well with those presented in

Figure 2A. Again, it appeared to make no difference whether SGH samples were filtered or unfiltered. Compared to the 0.5% PT samples, they exhibited a significantly greater capacity of facilitating cells to deal with PT necromass. In parallel, 0.5% PT filtrate supported the growth of cells much better than did the medium made of unfiltered 0.5% PT-CS. Notably, the 0.5% PT-CS inoculum was lagging even behind the expansion of that grown in the necromass alone, which once again showed that 0.5% PT-CS imposes an additional challenge to cell proliferation.

Thus, in conclusion, we can state that the compounds from cells that die by PCD have a marked ability to enhance cell proliferation in the presence of a non-PCD necromass. Viewed from the perspective of a real ecological situation, the observation would imply that the repopulation dynamics of a shattered population would decisively depend on the proportion of cells that have died by PCD.

3.4. Further Characterization of PCD Products

This further characterization was prompted by a previous finding and an interesting suggestion. Namely, previous work in

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

19] and

C. reinhardtii [

10] showed that heat treatment had no impact on the growth-beneficial capacities of cellular materials produced by PCD. And the suggestion hinted above is actually the idea that extracellular micro-vesicles could be responsible for the (conspecific) delivery of the beneficial PCD substances [

14]. The subject certainly merits further investigation, but a comprehensive exploration of the issue would obviously require extensive experimental development that could not be undertaken at the moment. Nonetheless, we wanted, at least tangentially, to touch upon the issue. Namely, the possibility that certain supramolecular structures are formed during PCD to aid in the distribution of the nutrients can be approached in a basic, preliminary, but still informative way by utilizing molecular weight cut-off fractions.

Therefore, we prepared regular SGH-SN (0.45 μm filtrate), then fractionated it by ultrafiltration through a membrane filter (Amicon Ultracel 100-K, Merck Millipore, Tullagreen, Ireland) with a molecular weight cut-off of less than 100 kDa. The material that passed through the filter (<100K filtrate) and the material retained by the filter (>100K retentate) were brought to initial volume with sterile distilled water. The initial SGH-SN and both 100K fractions were analyzed for heat stability in regard to their beneficial growth effects. As can be seen in

Figure 4A, heated (for 20 min at 100°C) SGH-SN and the <100K filtrate produced growth curves that were quite similar to those observed for the non-treated equivalents, indicating that their growth-promoting properties were not affected by heat. Also, it was evident that the majority of the activity passed through the 100K filter, revealing that the provision/distribution of the nutrients was not crucially dependent on some kind of supramolecular structures. As for the retentate, its nutritional capacity was about 7% that of the total content. Interestingly, unlike the case with the filtrates, recycling of the material retained by the 100K filter was affected by the heat treatment, as evidenced by an increase in lag phase, relative to that in the unheated sample (

Figure 4A).

To further out this investigation, we conducted a preliminary testing to assess the stimulation of growth in the presence of PT cells using both unheated and heated SGH-SNs. The results showed that the heated sample exhibited a modest reduction in activity, and this was observed only at the highest concentration tested (1x10

8 PT cells/mL) (not shown). Thus, it was immediately apparent that heating does not cause any dramatic effect on the capacity of the SGH substrates to support the growth in the presence of PT cells. Therefore, to determine if the observed change was significant, we repeated the experiment applying an even higher concentration of PT cells (1.2x10

8 PT cells/mL). Additionally, a concentration of 8x10

7 PT cells/mL was used to determine any potential stronger effects of the treatment on the 100K fractions. The growth was followed over 3 days, and the results are given in

Figure 4B.

The first thing to note is that a significant impact of the heating could indeed be observed, but only under the conditions of very high densities of PT cells (

Figure 4Ba). This effect was more pronounced in the case of heated <100K filtrates (

Figure 4Bb). Already in the presence of 8x10

7 PT cells/mL, the growth in the heated <100K filtrate was, for the first 24h, lagging far behind (>100X) the proliferation that the respective control made in the same period. The growth was picking up but continued to substantially lag behind even after 48h of incubation. The inoculum seeded into the 1.2x10

8 sample failed to adapt and grow even after 72h of incubation. Within the same experimental setup, we did not detect any effect of heat on the growth-stimulating properties of the 100K retentate (

Figure 4Bc). Again, the growth-stimulatory capacity of the retentate was clearly lower than that of the <100K filtrate or SGH-SN.

These results enable two fairly firm conclusions to be drawn. First, the material retained by the 100-K filter is not a major contributor to the nutrient capacity of SGH substrates. Second, heat did not appear to have a profound impact on the capacity to induce enhanced cell proliferation, either in the presence or absence of a non-PCD necromass. Nonetheless, it may not be disregarded that the capacity of heated <100K filtrates to promote growth at the highest densities of PT cells is significantly more attenuated than that of heated SGH-SN. This would suggest that there are some heat-protective qualities to the 100K retentate.

3.5. Beneficial Effects of U. maydis SGH-Materials Extend to Other Closely Related Species

As we mentioned in the Introduction, it was reported previously that PCD materials in

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii benefited others of the same species but inhibited the growth of two other species of the same genera [

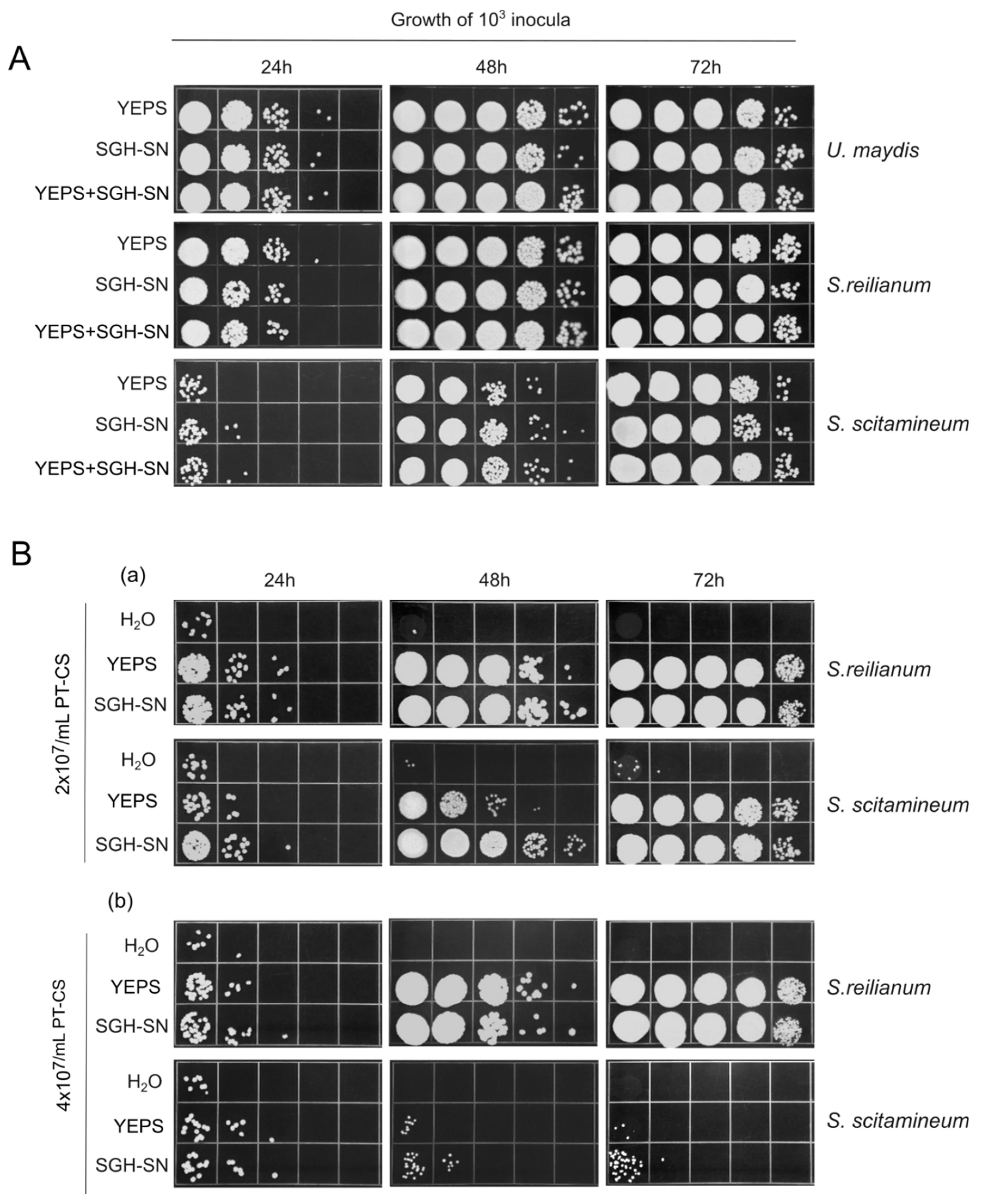

20]. We tested whether the same was true for SGH-materials by assessing the growth of two closely related species from the family Ustilaginaceae,

Sporisorium reilianum and

Sporisorium scitamineum. We did this by comparing the growth of these species in 100x diluted YEPS, in SGH-SN, and in a 1:1 mixture of these two media. Parallel

U. maydis cultures served as a reference. The daily growth measurements taken over a 3-day period at 24°C are given in

Figure 5A. Overall,

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum responded in exactly the way

U. maydis did. The beneficial effect of SGH-material was evident, and each species displayed a growth profile in this medium similar to that observed in 100x diluted YEPS. In other words, no negative effects on population growth were noted in the two species, which, along with

U. maydis, belong to the same family.

With this realization, we next examined whether SGH-material could counteract the growth-inhibitory effects of PT cells. However, before proceeding, we first needed to assess the sensitivity of

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum to the inhibitory effects of the 0.7% PT necromas. Therefore, we tested the ability of

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum to survive and reproduce at PT cell densities ranging from 1x10

7 to 4x10

7 over a 3-day period. For comparison, we utilized equivalent inocula of

U. maydis as a reference. The results, shown in

Figure S1 (Supporting information) clearly demonstrate that

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum survive very much worse than

U. maydis when challenged with increasing densities of PT cells. This indicates that

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum are much more susceptible to the detrimental effects of 0.7% PT cell necromass.

Instructed by the above findings, we applied two densities of PK cells (2x10

7 and 4x10

7 cells/mL), supplemented with either 100x diluted YEPS or SGH-SN, inoculated the samples with

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum cells (at 10

3 cells/mL) and incubated the cultures at 24°C, for 3 days. As

Figure 5B makes clear, although both species displayed about the same (high) sensitivity to the necromass, they differ considerably in their response to the stimulatory effect of SGH-materials. When compared to YEPS, SGH-SN has more beneficial effect on the growth of

S. scitamineum. Specifically, proliferation of

S. scitamineum was observed only at the lower density of PT cells tested. It is also of interest to note that

S. scitamineum was less responsive to 100x diluted YEPS.

In summary, we found that the beneficial effects of U. maydis SGH materials extend to at least two other closely related species, although the degree of benefit varies. It is also important to note that U. maydis displayed a remarkably greater ability to withstand the adverse effect of PT cell necromass.

4. Discussion

A lot is known about the various physiological mechanisms and eco-evolutionary strategies that enable microorganisms to cope with different types of environmental stress [

2,

3]. Indeed, truly phenomenal achievements have been made even in understanding the molecular and mechanistic aspects of these adaptations. In contrast, much less is known about microbial susceptibilities, frailness, and death. And there is even less we can say about how devastated populations restore viability in the wake of a highly killing stress. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that comprehending post-stress recovery and its underlying mechanisms is a necessary component of any comprehensive understanding of how microbes persist in very harsh and fluctuating environments.

Using

U. maydis as a model, our recent post-stress “repopulation upon shattering” (RUS) studies have demonstrated that this single-celled, haploid, eukaryotic yeast-like microbe reconstitutes devastated populations with remarkable efficiency, by feeding on the intracellular compounds leaked from the dead and dying cells [

4,

6]. Accordingly, RUS could be conceptualized as having two principal operations, the cellular self-degradation activity and the recycling one. These two aspects of RUS are quite distinct, each presenting its own conceptual problems, promoting a distinctive set of questions and each requiring specific analytical approaches and methodological tools [

5]. Therefore, advancing our understanding of these two major dimensions of RUS requires a diverse array of evidence.

While these two major operations are certainly distinct, they are also profoundly interconnected. This connection is primarily established by the end products of cellular decomposition—microbial molecules that serve as the starting material for the recycling and regrowth of the surviving cells. Thus, to the extent that the process of cellular dismantling is active (autolytic), the surviving cells reap the nutritional benefits from the perished cells with a reduced metabolic cost of producing hydrolytic enzymes that would otherwise be required of them to accomplish the task. However, previous studies and the current work indicate that the overall quality of nutrients released from dying cells depends on the type and intensity of stress as well as the type of cell death involved. Indeed, it is of no little interest that the most preferable nutrients are produced and donated to the surviving cells by programed self-disintegration so that PCD can be seen as an efficient means for facilitating the export of fitness to the surviving subpopulation (for the fitness transfer point see [

21]. More recently, PCD has been further explored as a mechanism that enables dying cells to sense their impending death [

22]. As such, this form of death not only supplies beneficial nutrients but also minimizes resource waste and avoids the release of necrotic toxins into the surrounding environment.

These lines of reasoning can be applied to the phenomenon of SGH-induced death. Under SGH conditions, the stressed cells somehow sense their impending death and consequently initiate PCD to release beneficial compounds. This process helps avoid necrotic events and the production of harmful growth-inhibitory molecules. Indeed, compared to the growth effects of cells that underwent necrosis, both SGH-CS and SGH-SN demonstrated a superior performance (see Fig 2A). In addition, the inocula grown in SGH-CS proliferated as rapidly and extensively as those in SGH-SN, indicating that the total PCD-derived necromass does not impose additional toxicity on the proliferating cells. But what is particularly remarkable is the degree to which products of PCD can stimulate growth even in the presence of necromass resulting from non-PCD processes (Fig 3A). This novel observation is especially significant when considering the potential ecological implications of PCD as an adaptive strategy for free-living microorganisms in response to fluctuating and harsh environmental conditions.

There are several compelling reasons to consider this finding significant. First, microorganisms in their natural habitats are regularly exposed to various stresses, which can differ in type and intensity. In addition, these stresses can occur simultaneously or cyclically, compounding the challenges faced by already stressed cells and contributing to the variability of the outcomes. Second, numerous experiments have demonstrated that the intensity and type of stress determine the manner of cell death (see for instance: [

11,

12,

13]). Thus, when cells experience stresses of the same type but at lower intensities, they tend to undergo PCD, while higher intensity stresses lead to death through necrotic processes. Third, the intensity of the stress not only influences the type of cell death but also affects the toxicity of the compounds released during the process [

4]. Given these considerations and the realistic assumption that stresses are not evenly distributed throughout the habitat, one can expect that populations will not be uniformly affected. They may experience different forms of death, resulting in necromasses of varying types and growth-promoting qualities. Therefore, the finding that PCD substrates can effectively counteract the growth-suppressive effects of non-PCD necromass suggests that the recovery of population density after catastrophic events and significant damages would largely depend on the proportion of cells that have died through PCD. Moreover, the effectiveness of growth in the presence of non-PCD necromass is directly related to the density of the initial inoculum [

4,

8,

9]. Thus, in the context of a massive loss of viability, the role of beneficial PCD nutrients would be vital for ensuring a critical initial recovery. Namely, our results would suggest that with a beneficial nutritional (PCD) source, surviving cells can achieve essential early growth even when faced with a substantial amount of non-PCD necromass. And, as the population revitalizes, it becomes increasingly capable of managing and exploiting more challenging nutrients. Therefore, from an ecological perspective, PCD can be viewed as a crucial adaptation that enhances fitness, especially during the initial stages of population rebound. This view is broadly consistent with recent findings that a strain of halotolerant microalga exhibiting increased PCD in response to hyperosmotic stress also demonstrated faster regrowth, eventually achieving a higher population size [

23].

Furthermore, it is obvious that a clearer understanding of this process may be achieved when precise nature of at least the major PCD growth-promoting compounds is known. So far, apparently little or no effort has been made to explore the molecular bases of these beneficial agents. In this context, it is also worth considering the intriguing suggestion that micro-vesicles could serve as a delivery system for transferring the beneficial effects [

14]. The results of our preliminary investigation indicated that the fraction of SGH-SN with a molecular weight of less than 100 kDa is the primary carrier of nutritional potential, suggesting that the availability of beneficial nutrients is not in

U. maydis critically dependent on any supramolecular structures. Conversely, although we and others [

10,

19] have found that the growth promoting properties are not dramatically affected by boiling, we were still able to observe a notable impact of thermal treatment on the capacity of heated <100K filtrates to promote growth at high densities of PT cells. This suggests that there may be some heat-protective qualities associated with the 100 kDa retentate. Whether this is relevant will require further investigation.

Drawing on previous research, we aimed to determine whether the SGH-released materials from

U. maydis promote conspecific growth testing two related species which belong to the same family

Ustilaginaceae,

S. reilianum and

S. scitamineum. The answer was negative. We observed that the organic substances released by PCD in

U. maydis do facilitate the growth of these closely related species. In addition, we found that the beneficial effects of SGH materials in overcoming the presence of non-PCD necromass also extend to these species, although the extent of this benefit varies. This contrasts with results obtained in

C. reinhardtii [

20] and

A. densus [

14] where conspecific effects of PCD-released materials were confirmed. However, at this moment any extensive discussion on these differences does seem rather unwise and premature. The most that we can say is that, unlike the aforementioned algae, all three

Ustilaginaceae species we tested are parasitic terrestrial fungi. Certainly, a clearer picture may be obtained only when the correlation between phylogeny and the beneficial action of the PCD-released materials from

U. maydis is assessed across a broader taxonomic scale. Furthermore, on a mechanistic level, it is not even clear if specific signals may exist, let alone their molecular nature. Thus, much more critical experimentation is needed before any definitive conclusions can be drawn.

However, another important observation emerged from these comparisons. When comparing the growth of these three species in the presence of increasing concentrations of PT cells,

U. maydis demonstrated a significantly greater ability to withstand the negative effects of non-PCD necromass. In a previous comparative study [

6], although both

U. maydis and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae were able to reconstitute their populations following strong oxidative stress,

U. maydis exhibited superior rates and extents of regrowth. This relative superiority can be attributed not only to its robust capability to recycle damaged and released compounds but also to its rapid self-disintegration and the release of intracellular molecules. Now we find that

U. maydis appears to be highly resilient in the face of the suppressive effects of non-PCD necromass. Viewed in terms of ecological fitness, these traits could be seen as conferring an important competitive advantage to this remarkable fungus.