1. Introduction

1.1. The Delineation of Cultural Heritage Buffer Zones Urgently Requires Mature Theories and Methods

The term “buffer zone” was first formally introduced by UNESCO in 1977 in

The Operational Guidelines for the World Heritage Committee [

1], and has been continuously updated in subsequent editions of it [

2]. Buffer zone is an expanded area extending beyond the core zone (the heritage site with recognized effective protection boundaries), serving as a supplementary preservation measure. Its functions include mitigating external threats, preserving and enhancing the outstanding universal value of heritage sites, etc, playing a crucial role in their preservation, sustainability, and development. Like core zones, buffer zones in historical and cultural preservation areas are used as administrative tools. Their primary purpose is to support core zone preservation efforts, maintaining the authenticity, integrity, and sustainability of heritage regions [

3]. The 2008 International Expert Meeting on World Heritage and Buffer Zones addressed buffer zones as a key agenda item. Document No. 25

World Heritage and Buffer Zones emphasized: “

For the purposes of effective protection of the nominated property, a buffer zone is an area surrounding the nominated property which has complementary legal and/or customary restrictions placed on its use and development to give an added layer of protection to the property [

4]”. After this conference, research on buffer zones has gradually increased.

The academic community currently recognizes the immaturity of buffer zones delineation methods for historical and cultural preservation areas. Scholars such as Wang argue that research on buffer zones for historic districts remains in its infancy, lacking systematic theoretical exploration [

5]. Lu and his colleagues highlight the oversimplified and conservative approaches in cultural heritage protection zone delineation, attributing this to insufficient systematic analysis of delineation criteria. They emphasize that buffer zones planning constitutes a multi-layered complex system requiring comprehensive functional structure research [

6]. Dong notes that preservation control zones for certain heritage sites exhibit poor specificity, typically expanding outward without precise geographic coordinates, while overlapping zones between different heritage sites persist [

7]. Kou et al. further observed that legally approved preservation control zones for protected sites often lack practical applicability and effectiveness, underscoring the urgent need for developing a scientific buffer zones delineation framework [

8].

1.2. The Perspective of Cultural Geography in the Buffer Zones' Delineation Methods Has Its Advantages

The ‘Purple Line’ in China’s territorial spatial planning is closely related to buffer zones [

9]. Compared to designating buffer zones for urban historical preservation areas or protected buildings, delineating buffer zones for rural historical and cultural villages presents greater challenges. This stems from two primary factors: First, urban historical buildings or urban historic districts have distinct and widely recognized cultural significance, and it is easy to delineate buffer zones based on cultural significance; second, urban areas possess more tangible physical elements than rural areas when establishing historical preservation buffer zones. In 1987, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) issued the

Washington Charter to supplement

the Venice Charter (1964),

International Charter for the preservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. The

Washington Charter outlines principles, objectives, and methods for preserving historical towns and urban areas, emphasizing that “

It also seeks to promote the harmony of both private and community life in these areas and to encourage the preservation of those cultural properties, however modest in scale, that constitute the memory of mankind [

10]”. Natural villages are small spatial units where cultural significance and value have not become part of collective historical memory.

Cultural geography excels in exploring the cultural significance of places and landscapes, making it well-suited for interdisciplinary efforts in delineating buffer zones for historic villages. The discipline’s fundamental analytical framework revolves around the “horizontal perspective” and “vertical perspective [

11]” to assess heritage integrity and sustainability. The “horizontal” perspective examines how micro-regions and broader contexts convert into each other—particularly the conversion of landscape values between small communities and large communities. The “vertical perspective” follows the concept of cultural landscape proposed by Carl O. Sauer, the founder of cultural geography, which emphasizes the interconnection between natural elements and human-made components [

12]. While architecture also addresses this “horizontal perspective” and “vertical perspective [

13]”, its spatial scope remains confined to smaller areas compared to the expansive geographical contexts emphasized in cultural geography.

2. Research on the Delineation of Buffer Zones for Historical and Cultural Heritage

Given that the purpose of establishing historical and cultural heritage buffer zones is to protect the integrity, authenticity, and sustainability of heritage sites, the literature review adopts the “horizontal perspective” to categorize relevant research into two types. One is “Inward”—the governance objective of buffer zones aims to preserve core areas. The other one is “Outward”—the governance objective of buffer zones seeks to establish connections between core areas and other parts of cities and villages.

2.1. “Inward”—The Research on Buffer Zones Supporting the Protection of Core Areas

There are many studies on buffer zones supporting core area protection, and the following cases are some supporting approaches.

First, controlling building heights within buffer zones aims to position the core area as the “figure” in a “figure-ground” relationship—a concept borrowed from psychology. “Figure” refers to the prominent architecture, while “ground” denotes the surrounding buildings that set off the figure [

14]. For instance,

Shenyang City, the Imperial Palace, Fuling and Zhaoling Protection Ordinance designates a buffer zone around Shengyang Imperial Palace. The buildings within the buffer zone are restricted to 9-30 meters in height based on their distance from the core area, ensuring the palace complex remains a prominent “figure” rather than being swallowed by modern concrete jungles [

15]. Similarly, Iranian scholars propose height controls for the Zandieh Complex and Hafezieh Tomb to preserve their historic skylines [

16]. Another example involves scholars requiring height restrictions in the urbanizing area between the World Heritage Sites of Süleymaniye Mosque and Zeyrek Mosque, the ruins of the two Mosques on opposite hills in Istanbul’s Historical Peninsula, to maintain visual communication between these heritage sites. These areas where height needs to be controlled are the buffer zones [

17].

Secondly, preserving elements associated with core heritage components aims to safeguard the landscape integrity of the site. Taking Iran’s Anahita Temple as an example, this ancient shrine enshrines Anahita, the Iranian water deity. The temple’s foundation relied on natural spring water within the site and a seasonal river flowing westward from the site. However, the modern development of the city has severed this connection—the spring water has been removed, while the upper reaches of the seasonal river have been developed into an urban water source. Scholars argue that incorporating seasonal river water sources into the temple’s heritage buffer zone would restore this vital relationship [

18].

Thirdly, preserving the original architectural character of buffer zones aims to remain the core area as the “figure” in the “figure-ground” relationship. A prime example is the preservation of gray-brick buildings in the buffer zone around The Historic Centre of Macao. It's located near the historic city center and has Chinese communities that once thrived. Its low-lying structures were built predominantly with gray bricks, which are suffering from saltwater infiltration in their foundations due to global climate change and summer typhoons. This makes the brickwork particularly vulnerable, making preservation of these heritage walls a key priority in buffer zone management [

19].

Fourthly, protecting related archaeological sites within buffer zones aims to highlight the central role of core area heritage. A prime example is Turkey's Sümela Monastery, a vital cultural site perched on the steep cliffs of the Pontic Mountains, specifically in the Altindere Valley. After the 1923 population exchange between Turkey and Greece, this Orthodox monastery suffered damage and fell into disrepair. Since 2000, it has been prioritized for preservation, while surrounding scattered monastic ruins (including the Monasteries of Vazelon, Panagia Keramesta and Kuştul that historically interacted with Sümela Monastery) have become the primary focus of preservation efforts in the buffer zone [

20].

Of course, many heritage buffer zones have adopted a variety of governance approaches. For example, the protection plan for Hailongtun Tusi Fortress in Guizhou Province, China, delineates three types of buffer zones, and the governance contents of each type of buffer zones are different [

21].

2.2. “Outward”—The Research on the Buffer Zones Promoting the Transition Between the Core Areas and Other Areas

There are also many studies on how to use buffer zones to promote the transition between core areas and other areas. The following cases are a few of the ways to promote it.

Firstly, defining functions of buildings in buffer zones helps preserve the continuous transition between ancient and modern architecture in a city. A prime example is the protecting design in Braga, Portugal. Braga is known as “the Rome of Portugal”. The historic building complex in its old city forms the core protection area. These buildings span from 14th-century to 18th-century buildings, creating an uninterrupted occupation sequence. Some modern buildings like Braga’s District Archive are inlaid in the buffer zone of the historic building complex. Established in 1937 in an abandoned monastery, the archive now faces limitations of space and facilities that prompted the University of Minho to renovate it. Faculty members from the school of Architecture and Civil Engineering Departments explored a renovation plan for the Braga’s District Archive [

22]. It highlights the historical bridging role of the archive, which establishes a smooth temporal transition between the core area and other modern parts of the city.

Secondly, listing the preserved objects in buffer zones to enhance the holistic perception of historical heritage among contemporary communities. A prime example is Iran’s Anahita Temple, originally constructed during the Achaemenid period and expanded through the Parthian period and Sasanian period, bearing Roman-Hellenistic architectural styles. The temple has been preserved through the Islamic era and adapted to the city’s built-up structures, where mosques and a bazaar are embedded around. Through interviews with locals, some researchers found that the “perceptual buffer zone” of locals about the temple encompassed later Islamic cultural elements [

17]. This perception-driven approach to buffer zones delineation has been implemented in UNESCO World Heritage preservation programs [

23,

24], creating opportunities for contemporary communities to actively participate in the sustainable management and protection of historical sites.

Thirdly, innovative design approaches are applied to buffer zones to achieve natural transitions between core areas and modern parts of cities. A prime example is Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. To preserve the historic architecture of the Austro-Hungarian era, faculty from the University of Sarajevo’s Architecture Department proposed creating transparent skylights above a centrally enclosed atrium. These skylights incorporate Ottoman-style lattice windows, which are called musebak. They allow visitors to experience a visual effect akin to gazing at the sky through the lattice windows of historic buildings when standing within such atrium spaces [

25].

3. Research Area and Research Methods

3.1. Information About Huitong Village in This Study

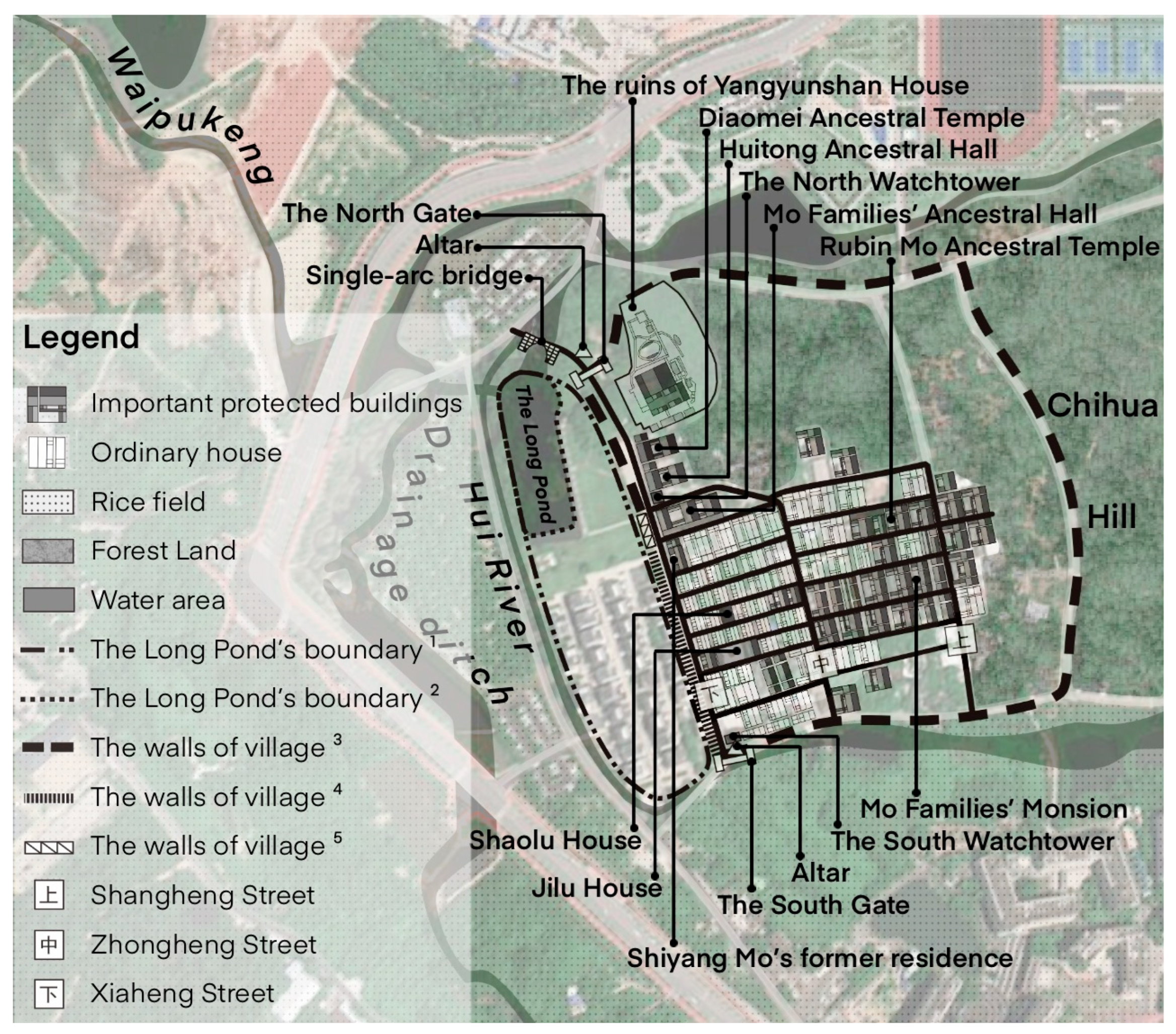

The village under study, Huitong Village, is a natural village administered by Huitong Administrative Village in Tangjiawan Town, Xiangzhou District, Zhuhai City, Guangdong Province. It was first recorded in 1732, the Year of Yongzheng Renzi in the Qing Dynasty, it boasts a history spanning nearly three centuries [

26]. The village’s name was after Mr. Yujing Mo’s styled name, which is Huitong. It was because of his financial contributions to the new village construction when Mo’s expended families moved here with the Bao and Tan families. Huitong Village was recognized as a district-level cultural heritage site in 2006, designated as a Guangdong provincial old village in 2009, certified as a Guangdong provincial traditional village in 2014, then selected to be one of the “Top 10 Beautiful Villages in Guangdong” in 2020 [

27]. All these labels solidify its cultural significance.

Many villages in the Pearl River Delta region share common spatial patterns [

28,

29]. Huitong Village shares four spatial characteristics with numerous villages in this region. First, ancestral halls serve as the core spatial organizing core of residential areas. Second, a pond (or a border river in some villages) is in front of the village, which has the function of flood storage and irrigation. Third, villagers use rammed earth walls for defense. Fourth, villages’ orientations are determined by the Feng Shui Theory. Huitong Village is situated in front of a small hill, which is one of the northern foothills of Fenghuang Mountain. Hence its orientation faces southwest. The Long Pond in front of the village connects to the upstream at Chihua Hill in Fenghuang Mountain range and the downstream Waipukeng (river name), while Hui River forms a semi-circular barrier in front of the village, serving as a natural defense against bandits in the early 20

th century. Through our field survey and the historical records, we have reconstructed Huitong Village’s historical appearances from the 1930s, 1960s, and 1980s.

Figure 1 is with the marks of some changes (e.g., The Long Pond in front of the village, the village walls, and farmland). Fortunately, the “three streets and eight alleys” layout has remained unchanged, and some old buildings are well-preserved.

3.2. Research Methods

The geographical methodology of this study shares common ground with empirical research approaches across multiple disciplines, which typically involve collecting data, investigating relationships, drawing conclusions, and conducting evaluations. What distinguishes it is the geographical focus on spatial relationships, and the “horizontal perspective and vertical perspective” framework previously discussed. Cultural geographers emphasize the cultural values embedded within these spatial relationships.

Step 1: Identifying elements. First, identify the historical buildings and building complexes to be protected in Huitong Village. Second, search for physical elements related to the protected buildings and building complexes within the village and surrounding areas. The specific methods include historical data analysis, contemporary literature review, and semi-structured interviews.

Step 2: Exploring relationships. First, identify “inward” connections that highlight the physical components of protected buildings and architectural complexes. Second, seek “outward” connections that facilitate a smooth transition from the core area to modern parts of cities. The specific operation in this step involves the research team continuously switching observation subjects in the field, particularly from the perspective of imagining historical subjects.

Step 3: Conducting evaluations. This constitutes the most crucial phase in cultural geography. It elevates geographical spatial and regional analyses to a conceptual level by addressing the cultural values underlying human activities (including buffer zones delineation for historical villages). Generally, we evaluate the two correlations of “inward” and “outward” analysis for buffer zones from four dimensions:①Whether the regulations of the historical village buffer zones have enhanced people’s well-being; ② Whether they have promoted social harmony; ③ Whether they have strengthened ecological environmental protection; ④ Whether they have maintained cultural vitality [

30]. Evaluations must consider both villagers’ perspectives and the broader community’s interests. Distinct from conventional buffer zones delineation methods, this approach employs a multi-subject framework, instead of an undifferentiated indicator system between subjects. A notable example is the study on Shedian Ancient Town in Henan Province, which analyzes 29 historical preservation plans and statistically aggregates key elements considered in buffer zones delineation, including natural landscapes, agricultural features, architectural characteristics, building quality, floor levels, age of structures, street patterns, historical elements, city context, cultural industries, and cultural component. Researchers give subjective weight on these elements to establish an universal delineation criteria of buffer zones [

31].

4. Analysis

4.1. Determine the Spatial Base Points for Delineating the Buffer Zone of Huitong Village

The research team conducted field investigations of cultural heritage buildings and historical building sites (

Table 1), which serve as spatial baselines for analysis of integrity, authenticity and sustainability.

4.2. The Adjustment Proposal of the Buffer Zone Boundary Based on View Corridors

View corridor/visual corridor is a spatial passage through which a viewpoint can observe specific scenery. The regulation of view corridor scope also serves as a control mechanism in spatial governance [

32]. A viewpoint refers to the position where an observer gazes at a specific scenery, while the scenery consists of both the observed landscape and its surrounding background [

33].

The first step: identifying elements. Through field research, we found many locations in Huitong Village that could serve as components of view corridors. Since the subject of analysis is a historical village, we also identified two types of viewing subjects: those from history and those from the present.

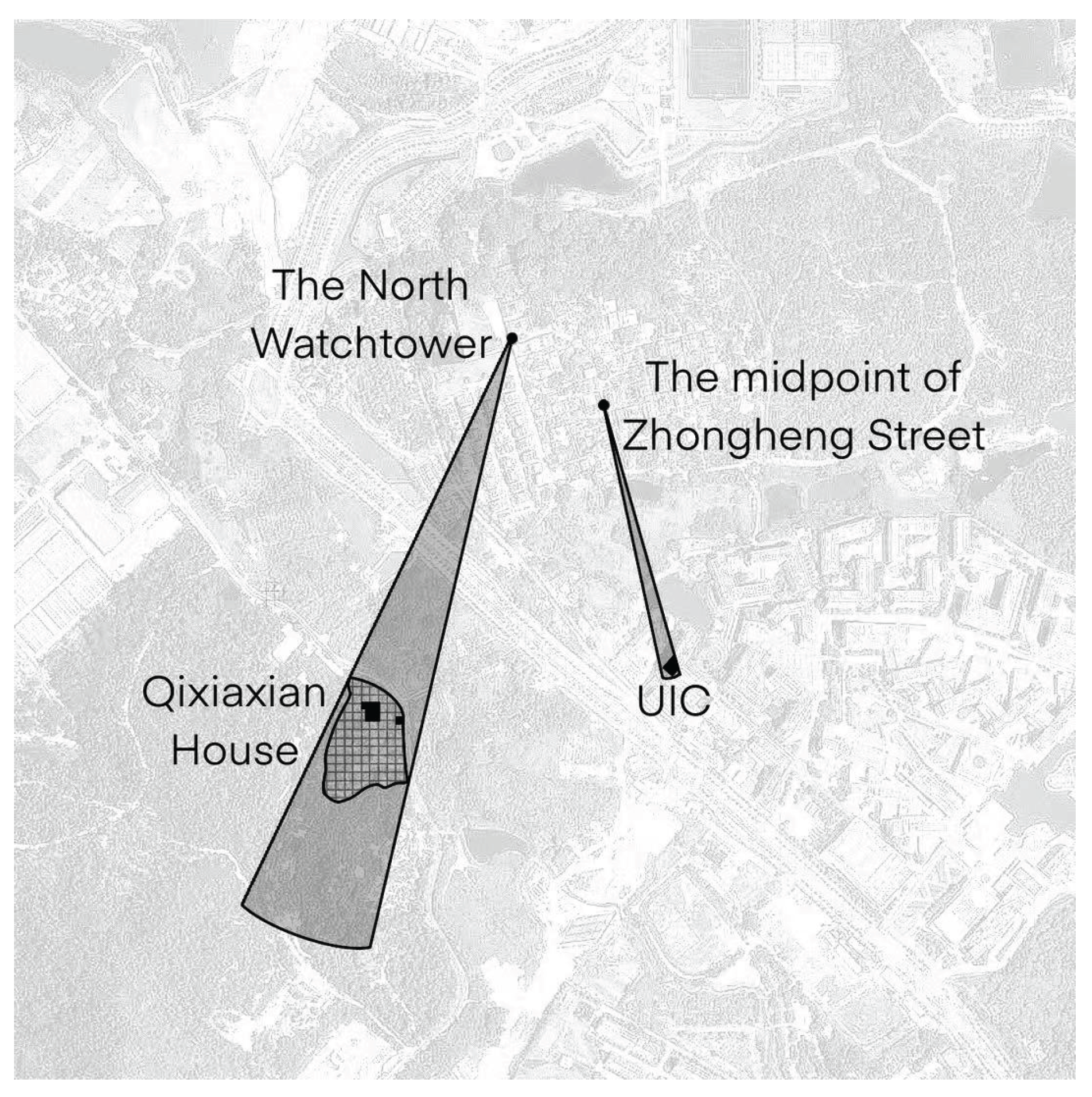

The second step: exploring relationships. Based on cultural significance derived from the subject’s visual perspective, we selected two sceneries. One is Qixiaxian Garden, the other is Beijing Normal University’s Hong Kong Baptist International College (Its acronym is UIC). Both are outside the village. The viewpoint for viewing Qixiaxian Garden is the North Watchtower, while the viewpoint for UIC is the midpoint of Zhongheng Street (

Figure 2).

The third step: conducting evaluations. The meaning of the view corridor we refined can become the connotation that people recognize the historical and cultural value of Huitong Village.

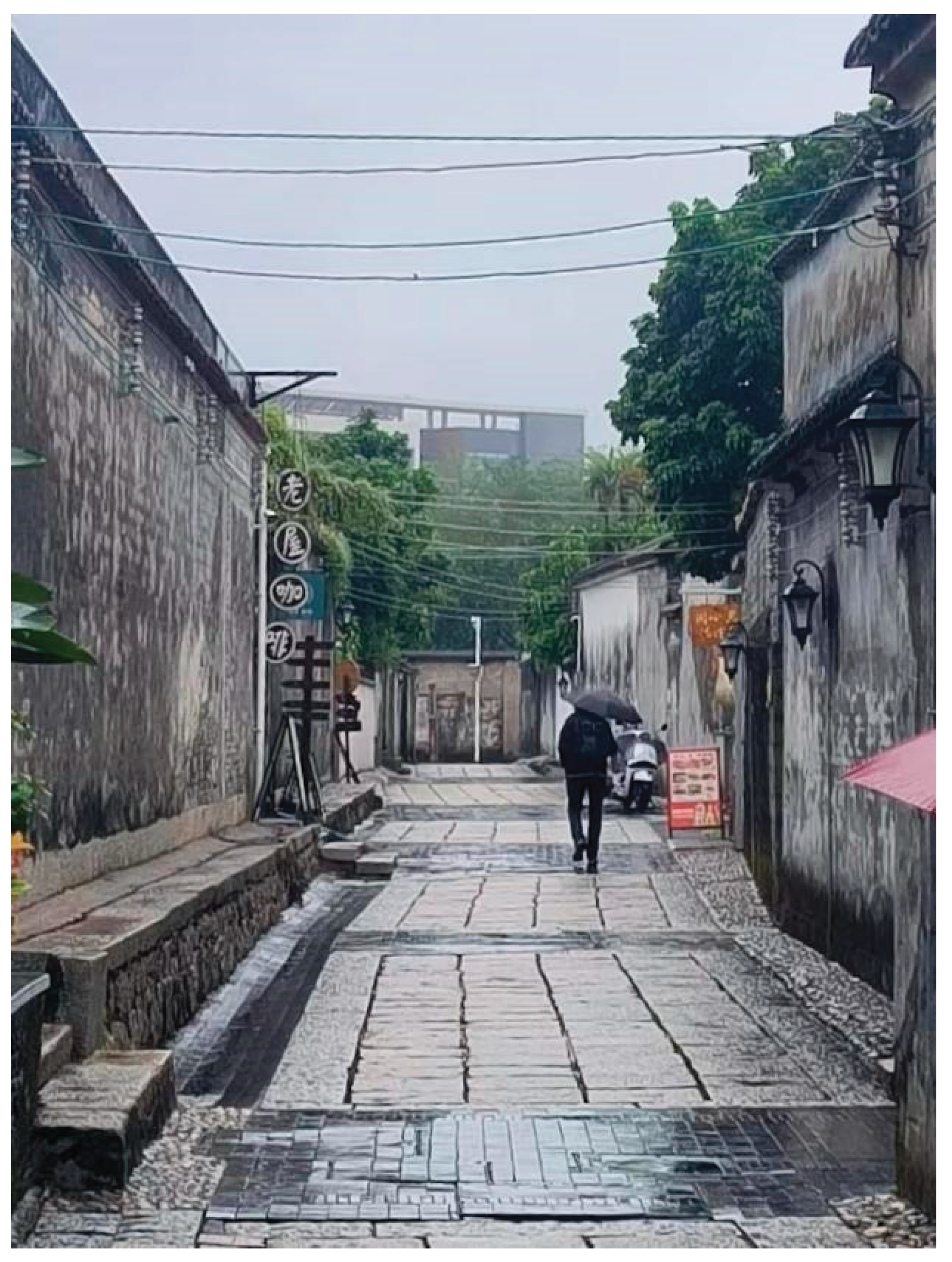

First, we evaluate the meaning of the “inward” view corridor, the view from the North Watchtower to Qixiaxian Garden.(

Figure 3) According to the rubbing text of

Zheng Gongren's Epitaph written by Dayuan Qu, a renowned educator in the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China, the proposal to build two watchtowers in Huitong Village came from Mrs. Yuxia Zheng, the wife of local resident Yingzou Mo [

34]. Gongren is the title for the wife of a third-grade official in ancient China. Yingzou Mo was the grandson of Shiyang Mo. Although he had not been an official in government, his wife still got the title of Gongren after her death. His grandfather was the first comprador at Hong Kong Butterfield & Swire Far East Branch. In 1918, to escape war and banditry, Yingzou Mo planned to relocate his family. uxia Zheng worried about that villagers unable to evacuate and thought they could not be abandoned, leading Yingzou Mo to change his mind and build two watchtowers in the village for defense. Scholars have highly praised this woman’s sense of responsibility towards her community [

35]. The construction of Qixiaxian Garden also bears Yuxia Zheng’s connection. She used this venue as her residence with three self-combed ladies (the women who reject traditional marriage customs). They meditated there together. After passing away in Hong Kong, she was buried at the west side of Qixiaxian Garden [

36]. Today, standing at the North Watchtower (

Figure 3) and gazing at Qixiaxian Garden, one can recall this compassionate and responsible woman. While other accounts about Qixiaxian Garden exist [

37], none have credible historical evidence [

38]. More importantly, these alternative narratives fail to reveal anything beyond Yuxia Zheng's personal charisma.

Secondly, we evaluate the meaning of the “outward” view corridor. Through interviews, we gained insights into how modern residents perceive the UIC buildings from Zhongheng Street. Looking along this street in both directions, what was once village gardens now forms the original view corridor scenery of an orchard-surrounded settlement. Now, looking to the southeast, the UIC buildings have become the scenery (

Figure 4). We initially proposed planting a large tree at the southeast end of Zhongheng Street to block the view of the UIC buildings. However, interviews revealed that residents were pleased with the government’s land acquisition for UIC development, as it significantly boosted both collective village income and individual benefits. Villagers believe the UIC presence makes them feel integrated into urban development rather than isolated as a small village nestled in Fenghuang Mountain. As previously mentioned, buffer zones should support outward-looking objectives. Therefore, we argue that view corridors showing UIC buildings carry greater positive meaning than those obstructing trees. UNESCO’s

Recommendation Concerning the Protection and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas states: “

Promote an integrated and harmonious relationship between preservation and new architectural and urban developments in order to preserve the integrity of the historic landscape [

39]”. Places should embrace all eras and styles, transforming historical elements into timeless concepts that transcend time [

40].

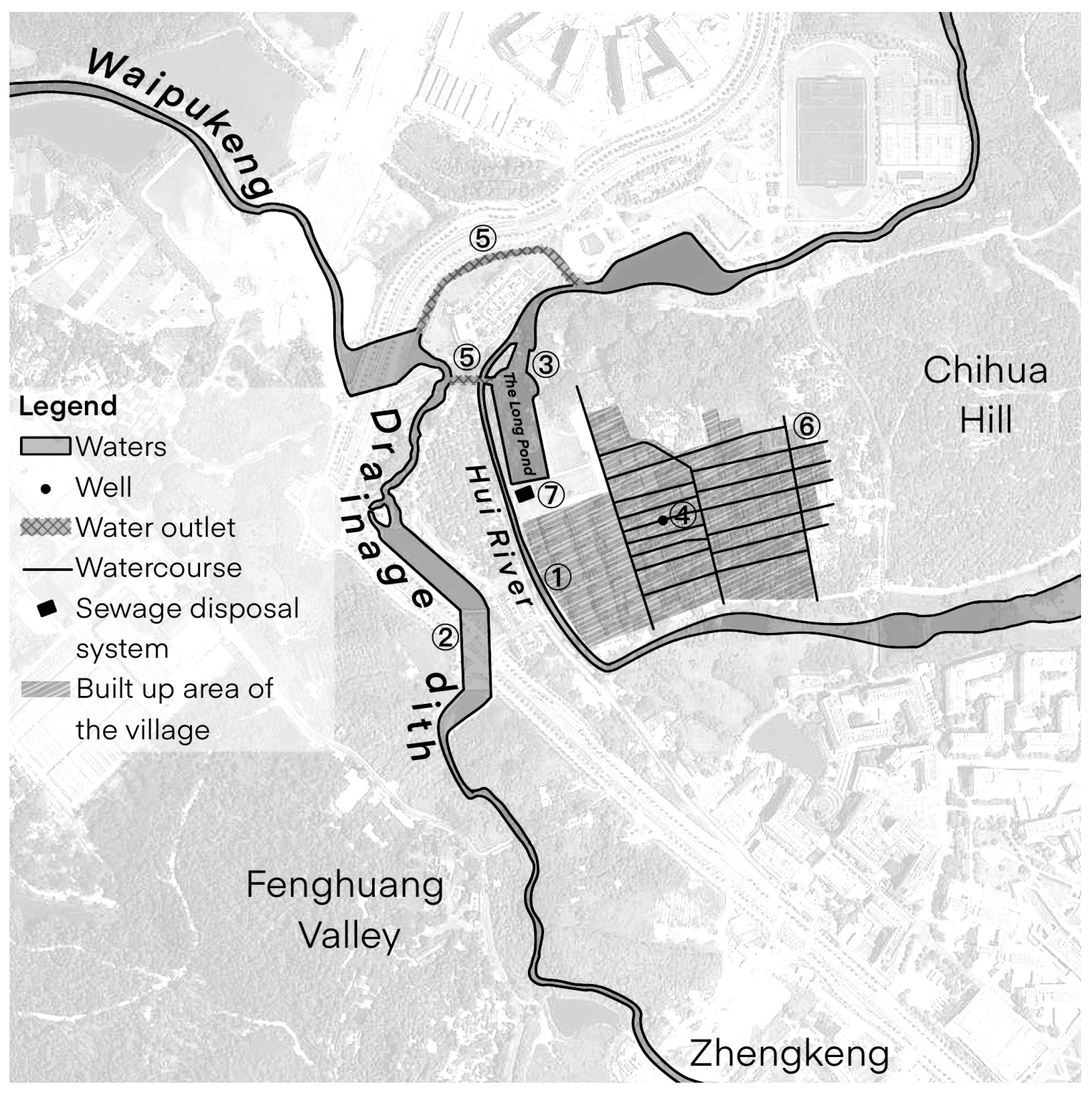

4.3. The Adjustment Proposal of the Buffer Zone Boundary Based on Water System Integrity

As mentioned in the previous introduction to the basic situation of Huitong Village, like many villages in the Pearl River Delta, water systems are an important element in its spatial structure. The key point of this study is to identify the complete boundary of the village’s water system and the unique meaning revealed by these boundaries. Subsequently, suggestions for adjusting the buffer zone boundary are proposed.

The first step: identifying elements. Through field research, the research team identified the main water system elements in Huitong Village (

Table 2). They also determined other related elements such as village walls, sluice gates, and streets, along with the historical and current water system elements.

The second step: exploring relationships. Due to factors like fluctuating water levels, natural water systems frequently fail to meet human needs for production and daily life, sometimes even causing floods. Historically, Huitong Villagers have modified natural water systems by constructing the Long Pond and drainage ditches to satisfy these demands, and modern sewage treatment systems still serve similar purposes. Our analysis explores three primary relationships.

Firstly, the relationship between water systems and farmland irrigation. As shown in

Figure 1, the Long Pond is situated at a higher elevation than the rice fields, allowing water from the pond flowing into the paddies naturally. Although the original fields no longer exist today, their former boundaries should still be incorporated into the buffer zone to preserve the “human-natural wisdom” of the passed villagers.

Secondly, the relationship between water systems and village defense structures. In earlier times, the Long Pond served as a “moat” surrounding the village walls. Hui River, flowing from the mountains, cut deeply through the southeastern side of the village, forming a natural barrier. Additionally, the river outside Huitiong Village’s northern water gap (marked ⑤ in

Figure 5) also functioned as a moat. Villagers interviewed revealed that they used to plant Euryale ferox Salibs (a thorny plant) in the Long Pond and Hui River, which could prevent bandits from crossing the pond and river. Therefore, all water bodies with defensive functions around the village should be designated in the buffer zone.

Thirdly, the relationship between water systems and village roads. The drainage channels in Huitong Village are primarily distributed along the “three streets and eight alleys” layout. Historically located on the surface within these streets and alleys, most village roads have now been converted underground during renovations. The “three streets” generally follow the contour lines of Chihua Hill, while the “eight alleys” run perpendicular to these contour lines. When heavy rainfall comes, the hill slope runoff cascades down, and the “eight alleys” irrigation channels serve as rapid drainage channels, effectively reducing the impact of slope runoff on the village’s foundation.

The third step: conducting evaluations. A folk rhyme preserved in Huitong Village history museum reads: “A pond ahead, two gates enclose an entire township”. This verse reflects villagers’ pride in their spatial layout, which stems from their ancestors’ ingenious integration of water resources to achieve dual benefits: improved irrigation and regional security (flood control and bandit prevention). Therefore, it is essential to designate a buffer zone around water-related elements outside the core area. Comparing with the published buffer zone in

Figure 5, we found that all these interconnected elements are located within the officially designated buffer zone.

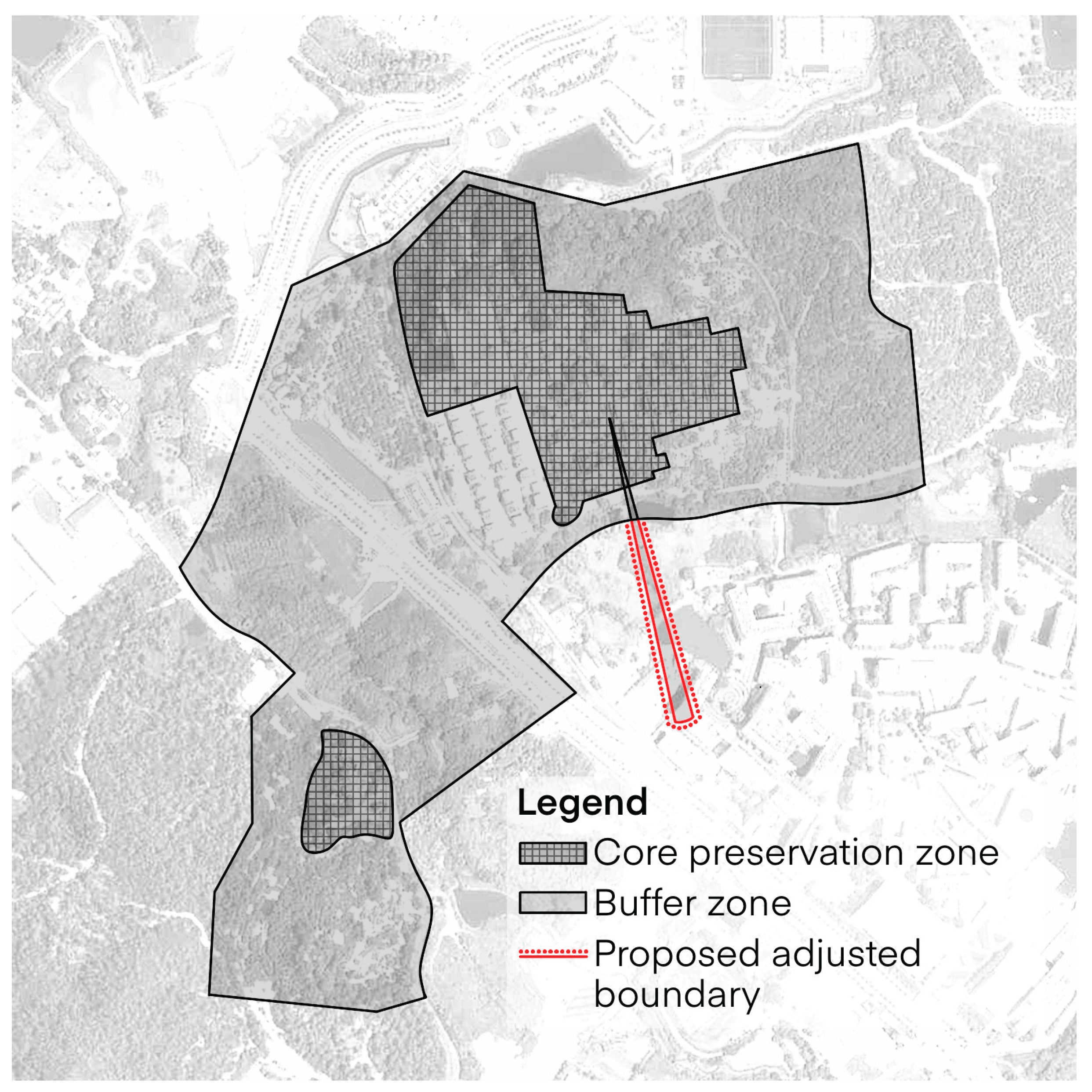

Our research group pictured map of the core preservation zone and the development control zone which is another term for buffer zone (issued by the Bureau of Natural Resources of Zhuhai) at the entrance of Huitong Village and Zhuhai City Planning Museum.

Figure 6 shows a map reconstructed based on our photo evidence. Through our analysis, we confirmed the official buffer zones were appropriate. The expanded buffer zone boundary was determined only by extending outward along the view corridor direction from Zhongheng Street to UIC.

5. Conclusions

Firstly, the view corridor meaning explored in this study enhances the possibility of greater public recognition for the buffer zone in Huitong Village. The core of cultural geography’s “horizontal perspective” analysis is explaining how landscapes within small areas gain acceptance across broader regions, or vice versa. The mechanism provided by this “horizontal perspective” analysis is cultural, rather than economic or social. Current studies on heritage buffer zones consistently assume that if the heritage is designed officially, it is recognized by everyone, without emphasizing the multi-subject recognition mechanism for heritage. In Huitong Village’s case, different subjects particularly outside the village agree to control heights within the view corridor not only because of beauty or official regulations, but also because both view corridors function as emotional triggers. The “inward” corridor evokes visitors’ admiration for Yuxia Zheng’s “compassionate responsibility” ethos, while the “outward” corridor allows them to experience China’s rural integration into urbanization.

Secondly, the cultural meaning of the view corridors explored in this study can serve as a value comparison reference for preservation planning at different scales. Current buffer zones delineation assume that planning must prioritize historical and cultural preservation over other land use values, thereby preventing individuals from breaking buffer zones regulations. Only a few scholars recognize the growing pressures on buffer zones management. For instance, the Liangzhu Heritage Site’s buffer zone is excessively large, maintaining “blank space” for construction, which might lead to desolate scenery in the heritage area [

41]. This exemplifies a failure to utilize buffer zones as governance tools for achieving spatial transitions between core areas and other areas. As some studies suggest, revaluing ancient sites should not merely preserve traditions but also pursue exceptional and sustainable interpretations [

42]. In this case, the view corridor cultural meaning we uncovered can serve as a reference for future potential subjects who want to break height limitations. If the value of breaking height limitations is lower than protecting the view corridor in all four evaluating dimensions introduced before, people will oppose it.

6. Discussions

Although this study takes Huitong Village as an example to emphasize the buffer zones delineation methods for the protection of historical and cultural villages, it does not imply that urban and rural cultural heritage have completely different delineation methods. A prime example is Carioca Landscapes between the Mountain and the Sea, a UNESCO World Cultural Landscape Heritage site approved in 2012 located in Rio de Janeiro. When delineating its buffer zone, the planners considered the boundary of the human-nature system surrounding this heritage site—a boundary that extends far beyond the physical space within the city into coastal waters [

43]. This method of expanding human-nature system boundaries could be effectively applied to buffer zone planning for rural settlements. However, we have yet to identify the unique characteristics of Huitong Village within a broader regional system.

While this study explores the place meaning of the landscape at Huitong Village, it has not sufficiently examined how historical processes shaped people’s evolving perceptions of its landscape. A kind of local meanings manifests as place attachment, which might be reflected by the multi-generational investments in Huitong Village by Mo families. This study does not address when the Mo clan ceased funding their ancestral home village at Cuiwei (it is now administered by Zhuhai Municipal) or when their preference shifted to property investments in Hong Kong, leading their descendants to reduce substantial investments in Huitong Village. Marxist geographers, like David Harvey, have been focusing on capitalist deep structures that could provide better explanatory. Future research should investigate which rural areas can sustainably rely on government and market forces to maintain village preservation funding.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the outcome of the National Undergraduate Training Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship & Student Research Training Program “Exploring the Delineation Method for Historical Village Buffer Zones from a Perspective of Cultural Geography: A Case Study of Huitong Village in Zhuhai” at Beijing Normal University’s Zhuhai Campus. Shangyi Zhou, as the supervising instructor of this project, authored the full text of this paper. Yusheng Zou and Siyuan Zang participated in discussions during the writing process. Research team members Jianghe Dong, Ying Dong, and Wei Yang contributed field investigation data and interview results.

References

- UNESCO. The Operational Guidelines for the World Heritage Committee. Available online: https://whc. unesco. org/archive/opguide77a. pdf. (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc. unesco. org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Yang, Y. Research on Buffer Zone Design of LuoyangSoutheast and Southwest Historical Block. D, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China, 2021. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Heritage and Buffer Zones. Available online: https://whc. unesco. org/en/series/25/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Ma, F. From the Perspective of Holistic Protection of Historical Blocks Research on the Concept and Theory of "Buffer Zone". Architecture & Culture, 2023, 08, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Li, B.; Dou, J. Analysis on the Delimitation Basis of Cultural Relics Protection Division. Intelligent Building & Smart City, 2020, 11, 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. Several Thoughts on the Protection Zoning of Cultural Relics Units. Identification and Appreciation of Cultural Relics, 2021, 12, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, X.; You, T. Construction Control Zones Delineation Based on Visibility Analysis: A Case Study of Three Cultural Relics Protection Units in Baoji City. Proceedings of Annual National Planning Conference 2014; Urban Planning Society of China, Eds. China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, China; 2014; pp. 314–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. Urban Purple Line Management Measures. Available online: https://www. gov. cn/gongbao/content/2004/content_62888. htm (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the preservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas. Available online: https://people. utm. my/lylai/wp-content/uploads/sites/630/2017/06/Washington-charter. 1. pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Hettner, A. Die Geographie, Ihre Geschichte, Ihr Wesen und Ihre Methoden, Wang L. trans.; The Commercial Press, Beijing, China, 2009, p. 135.

- Sauer, C. O. The Morphology of Landscape. In Land and Life: A Selection from the Writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer; Leighly J., Eds. University of California Press, Berkeley, United States, 2024, pp. 315-350.

- Abrar, N. Contextuality and Design Approaches in Architecture: Methods to Design in a Significant Context. International Journal of Education & Social Sciences, 2021, 11, 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- Neuro Launch editorial team. Figure-Ground Psychology: Definition, Principles, and applications. Available online: https://neurolaunch. com/figure-ground-psychology-definition/. (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Li, Q.; Yuichi, F.; Morris, M. Study on the buffer zone of a Cultural Heritage site in an urban area: the case of Shenyang Imperial Palace in China. WIT Transactions on Ecology and The Environment, 2014, 9, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizfahm Daneshmandian, M.; Behzadfar, M.; Jalilisadrabad, S. The Efficiency of Visual Buffer Zone to Preserve Historical Open Spaces in Iran. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2020, 52, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarihan, E. Visibility Model of Tangible Heritage. Visualization of the Urban Heritage Environment with Spatial Analysis Methods. Heritage, 2021, 4, 2163–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, H.; Homa, I. B.; Shokoohi, S.; Shokoohi, S. Perceptual buffer zone: a potential of going beyond the definition of broader preservation areas. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 2020, 3, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Zheng, J. Recognition of Damage Types of Chinese Gray-Brick Ancient Buildings Based on Machine Learning—Taking the Macau World Heritage Buffer Zone as an Example. Atmosphere, 2023, 2, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbey, V. Sümela Manastırı Kültürel Mirası için Tanımlanması Gereken Miras Alanı ve Tampon Bölgesine Yönelik Öneriler. Selçuk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 2021, 45, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Gao, H. Analysis of the Delimitation Principles and Management Strategies for the Buffer Zone of the World Heritage Site Hailongtun. China Cultural Heritage, 2018, 02, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. P.; Mendonça, P.; Ramísio, P. J. Heritage Buildings as a Contribution to the Contemporary City: The Relocation of Braga's District Archive. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 2020, 1, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Noor, S. M.; Rasoolimanesh, S. M. Perception of young local residents toward sustainable preservation programmes: a case study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site. Tourism Management, 2015, 48, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, N. F. N.; Mohamed, E. Public perception: heritage building preservation in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2021, 50, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causevic, A.; Salihbegovic, A.; Rustempasic, N. Integrating New Structures with Historical Constructions: A Transparent Roof Structure above the Centrally Designed Atrium. IOP conference series. Materials Science and Engineering, 2019, 11, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tian, M. The annals of Xiangshan County; Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Shanghai, China, 2015, p. 1331.

- XU, X. Protection and Revitalization of Traditional Ancient Village Based on Landscape Gene Recognition and Expression: Taking Huitong Village in Zhuhai as an Example. Urban Architecture Space, 2023, 11, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Peng, C. Spatial Form of Traditional Village in the Pearl River Delta in Syntactical View: A Case Study of Nancun Village in Panyu, Guangzhou. Architecture & Culture, 2023, 08, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, X. Study on the Public Space Form of Traditional Cantonese Village: The Case of Guangzhou Panyu. South Architecture, 2013, 04, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. Discussion on the "113445" Framework in the Textbook of Human Geography. China University Teaching, 2018, 08, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Kong, D. Urban historic heritage buffer zone delineation: the case of Shedian. Heritage Science, 2022, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visual corridor definition. Available online: https://www. lawinsider. com/dictionary/visual-corridor (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Wang, Y. The Control of Urban Fifth Façade Based on Visual Corridor: A Case Study of Beijing. Proceedings of Annual National Planning Conference 2021; Urban Planning Society of China, Eds. China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, China; 2021; pp. 539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.; Wu, L. Zheng Gongren's Epitaph: Several Aspects of Social Life in Lingnan. Root Exploration, 2020, 2, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. A Study on Rural Women in Guangdong Amid Regional Social Changes During the Ming and Qing Dynasties; Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing, China, 2016, pp. 273-285.

- Feng, J.; Li, J. A Case Study on Guangfu Village: The Figures and Buildings during Modern Rural Constructions in Huitong Village, Xiangshan County. New Architecture, 2021, 06, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Y. Modern Village Planning in Jinding Town, Zhuhai City: Research on the Protection and Development of Huitong Village. Collected Papers on Architectural History, 2002, 02, 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.; Wu, L. Study on Qixiaxian Garden, a Dilapidated Western-Style Mansion in Zhuhai. Root Exploration, 2021, 3, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. Available online: https://unesdoc. unesco. org/ark:/48223/pf0000158388 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Foucault, M. Of other spaces: utopias and heterotopias (1967). In The semiotic challenge; Barthes, R., Eds.; Hill and Wang, New York City, United States, 1988, pp. 420-426.

- Wang, X. The Role of Buffer Zones in World Heritage preservation: A Case Study of the Liangzhu Site. China Cultural Heritage, 2020, 6, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cervera, J. C. De lo faínadé a lo efímero la arquitectura moderna ante el paso del tiempo. In Criterios de intervención en el patrimonio arquitectónico del siglo XX: Conferencia Internacional CAH20thC, Madrid, 14, 15 y 16 de junio de 2011 = Intervention approaches in the 20th Century architectural heritage: International Conference CAH20thC; Domingo, M., Muíña, I., Eds.; Ministerio de Cultura, Madrid, Spain, 2011, pp. 259-264.

- Schlee, B. M. The role of buffer zones in Rio de Janeiro urban landscape protection. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 2017, 7, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).