Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Bacteria and Culture Conditions

2.3. Membrane Characterization

2.4. MFC Set-Up and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

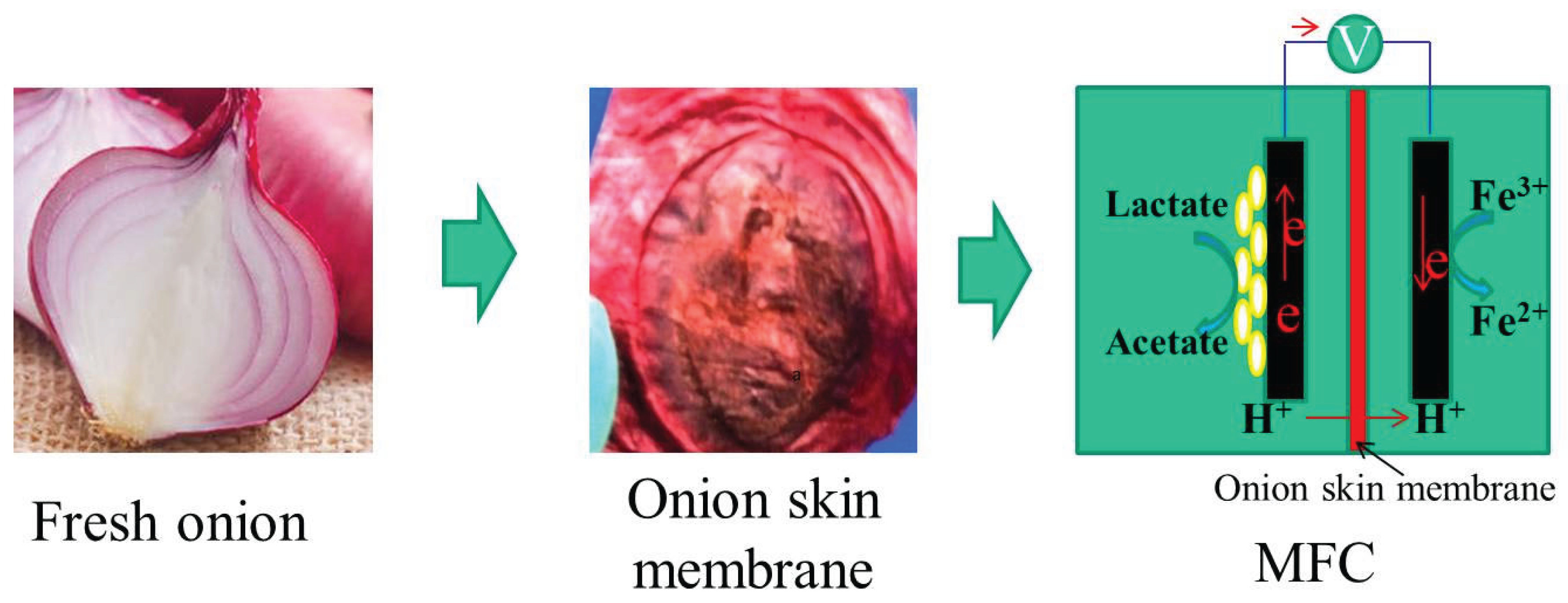

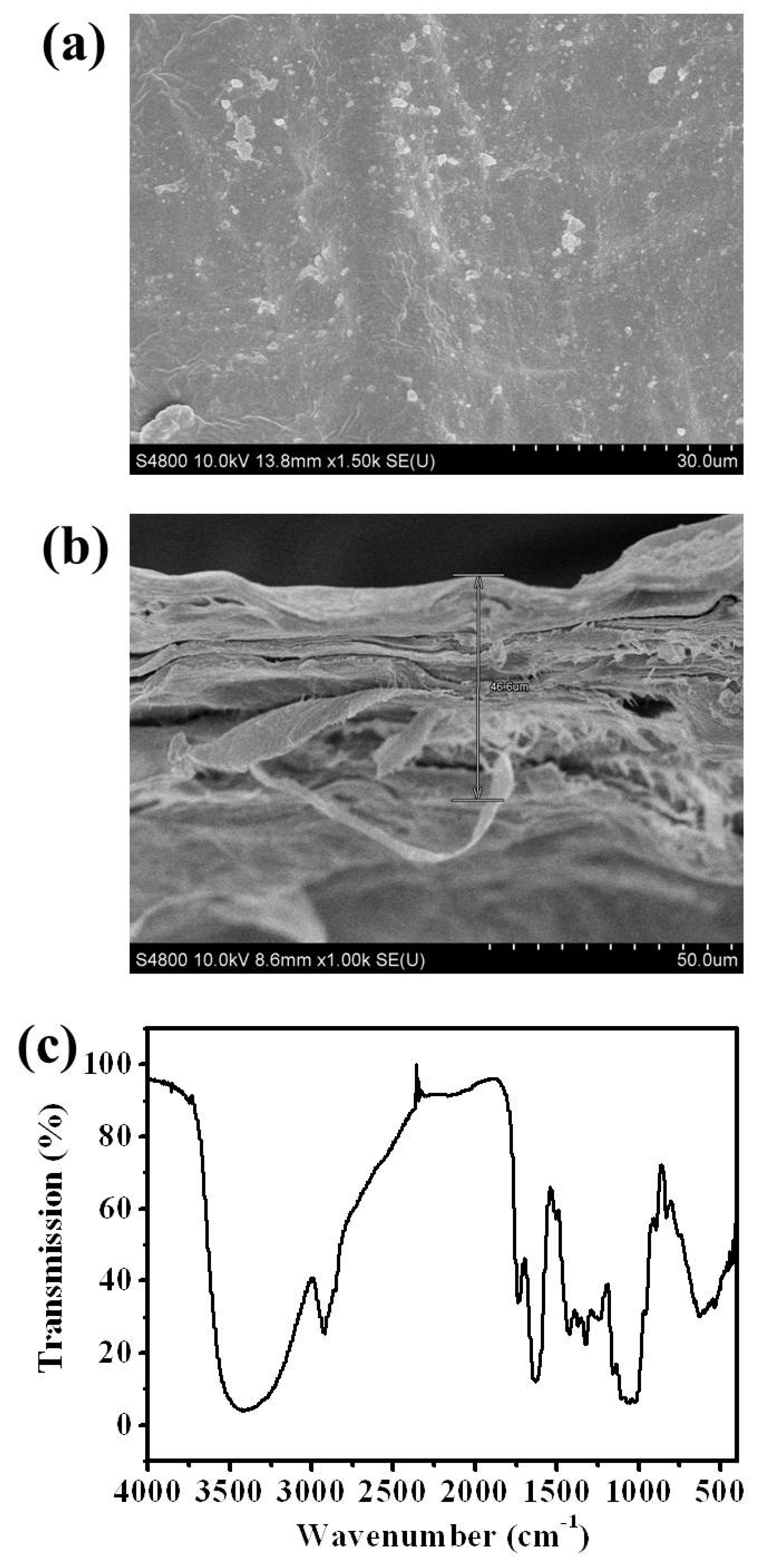

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of Onion Skin Membrane

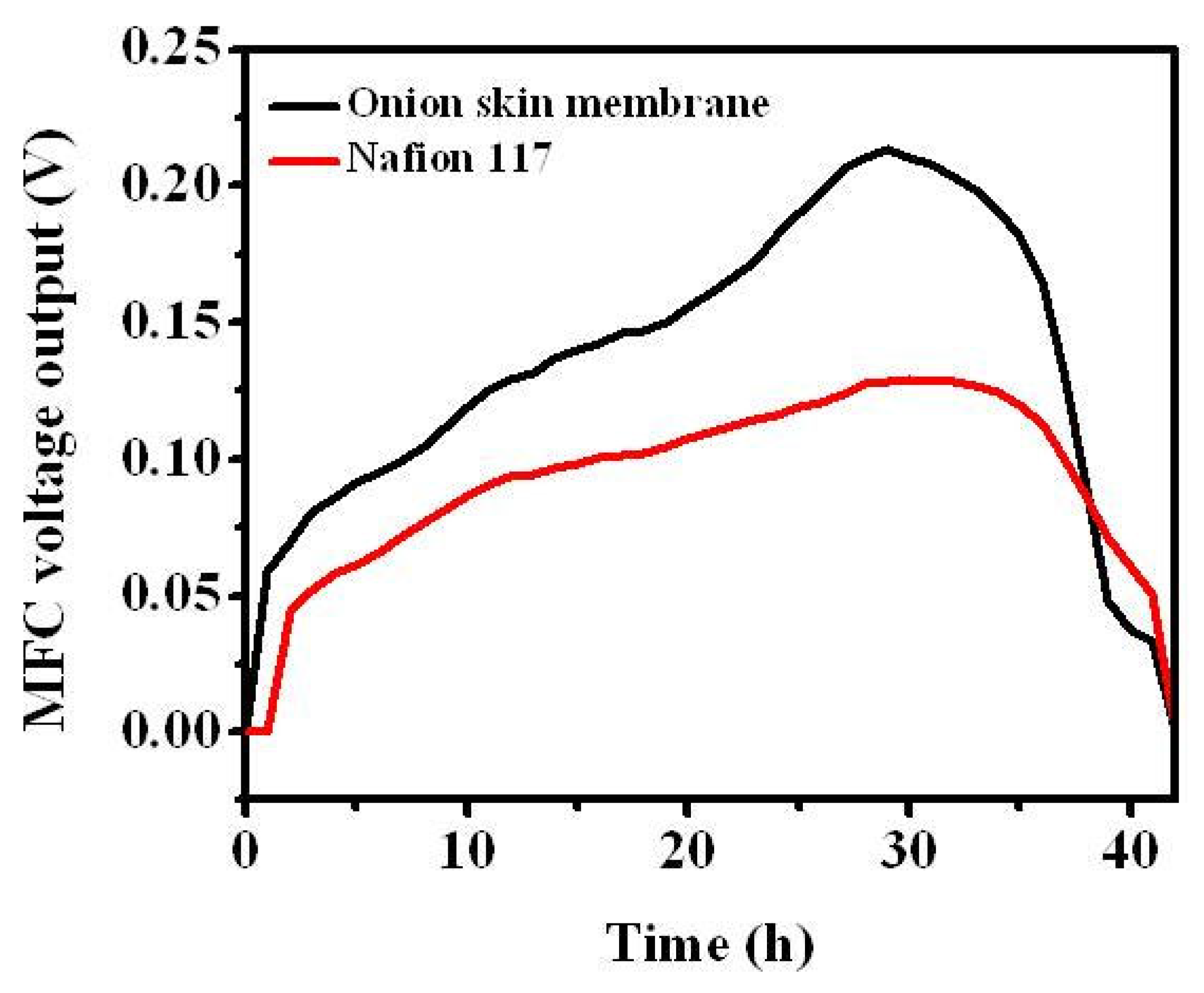

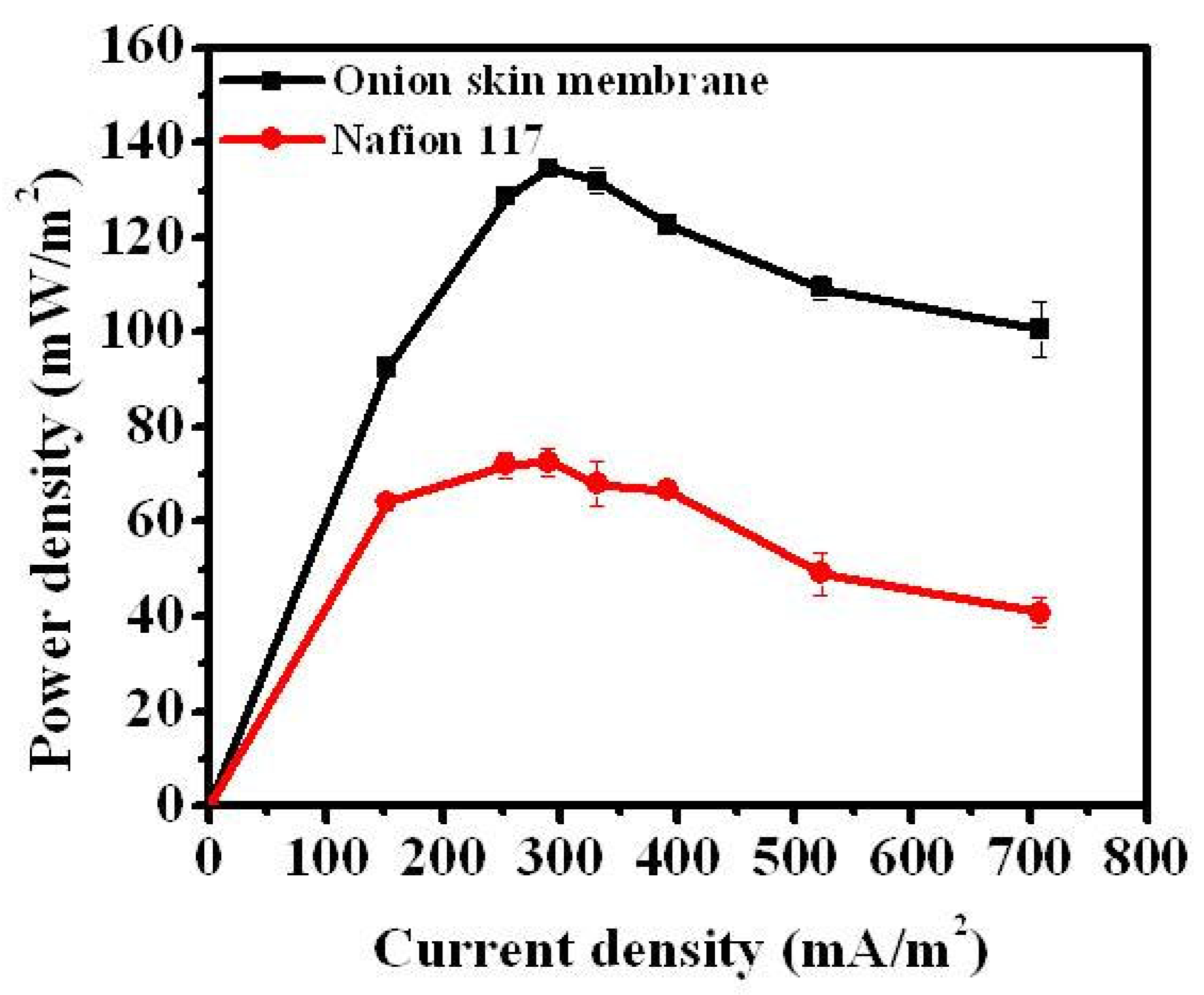

- Figure Legends

3.2. Performance of MFC with Onion Skin Membrane

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgment

References

- Arcella, V., A. Ghielmi and G. Tommasi (2003). "High Performance Perfluoropolymer Films and Membranes." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 984(1): 226-244.

- Ayyaru, S., P. Letchoumanane, S. Dharmalingam and A. R. Stanislaus (2012). "Performance of sulfonated polystyrene–ethylene–butylene–polystyrene membrane in microbial fuel cell for bioelectricity production." Journal of Power Sources 217: 204-208.

- Babbar, N., S. Baldassarre, M. Maesen, B. Prandi, W. Dejonghe, S. Sforza and K. Elst (2016). "Enzymatic production of pectic oligosaccharides from onion skins." Carbohydrate Polymers 146: 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Bautista, D. M., P. Movahed, A. Hinman, H. E. Axelsson, O. Sterner, E. D. Högestätt, D. Julius, S.-E. Jordt and P. M. Zygmunt (2005). "Pungent products from garlic activate the sensory ion channel TRPA1." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102(34): 12248-12252.

- Behera, M., P. S. Jana and M. M. Ghangrekar (2010). "Performance evaluation of low cost microbial fuel cell fabricated using earthen pot with biotic and abiotic cathode." Bioresource Technology 101(4): 1183-1189. [CrossRef]

- Benítez, V., E. Mollá, M. Martín-Cabrejas, Y. Aguilera, F. López-Andréu, K. Cools, L. Terry and R. Esteban (2011). "Characterization of Industrial Onion Wastes (Allium cepa L.): Dietary Fibre and Bioactive Compounds." Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 66(1): 48-57.

- Block, E., A. J. Dane, S. Thomas and R. B. Cody (2010). "Applications of Direct Analysis in Real Time Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS) in Allium Chemistry. 2-Propenesulfenic and 2-Propenesulfinic Acids, Diallyl Trisulfane S-Oxide, and Other Reactive Sulfur Compounds from Crushed Garlic and Other Alliums." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58(8): 4617-4625.

- Cheng, S. and B. E. Logan (2007). "Sustainable and efficient biohydrogen production via electrohydrogenesis." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(47): 18871-18873.

- Choi, I. S., E. J. Cho, J.-H. Moon and H.-J. Bae (2015). "Onion skin waste as a valorization resource for the by-products quercetin and biosugar." Food Chemistry 188: 537-542. [CrossRef]

- Choi, T. H., Y.-B. Won, J.-W. Lee, D. W. Shin, Y. M. Lee, M. Kim and H. B. Park (2012). "Electrochemical performance of microbial fuel cells based on disulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) membranes." Journal of Power Sources 220(0): 269-279. [CrossRef]

- Cusick, R. D., Y. Kim and B. E. Logan (2012). "Energy Capture from Thermolytic Solutions in Microbial Reverse-Electrodialysis Cells." Science 335(6075): 1474-1477. [CrossRef]

- Daud, S. M., B. H. Kim, M. Ghasemi and W. R. W. Daud (2015). "Separators used in microbial electrochemical technologies: Current status and future prospects." Bioresource Technology 195: 170-179. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., H. Hu and H. Liu (2007). "Enhanced Coulombic efficiency and power density of air-cathode microbial fuel cells with an improved cell configuration." Journal of Power Sources 171(2): 348-354. [CrossRef]

- Gawlik-Dziki, U., K. Kaszuba, K. Piwowarczyk, M. Świeca, D. Dziki and J. Czyż (2015). "Onion skin — Raw material for the production of supplement that enhances the health-beneficial properties of wheat bread." Food Research International 73: 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Grzebyk, M. and G. Poźniak (2005). "Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) with interpolymer cation exchange membranes." Separation and Purification Technology 41(3): 321-328. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., H. Zhang, Y. Li, J. Wang, L. Ma, W. Zhang and J. Liu (2015). "Synergistic proton transfer through nanofibrous composite membranes by suitably combining proton carriers from the nanofiber mat and pore-filling matrix." Journal of Materials Chemistry A 3(43): 21832-21841. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z. Z. and A. J. Jaeel (2013). "Sustainable Power Generation in Continuous Flow Microbial Fuel Cell Treating Actual Wastewater: Influence of Biocatalyst Type on Electricity Production." The Scientific World Journal 2013: 7. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X., Z. He, X. Zhang and X. Tian (2016). "Carbon paper electrode modified with TiO2 nanowires enhancement bioelectricity generation in microbial fuel cell." Synthetic Metals 215: 170-175. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. and B. E. Logan (2011). "Series Assembly of Microbial Desalination Cells Containing Stacked Electrodialysis Cells for Partial or Complete Seawater Desalination." Environmental Science & Technology 45(13): 5840-5845. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., S.-H. Shin, I. S. Chang and S.-H. Moon (2014). "Characterization of uncharged and sulfonated porous poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes and their performance in microbial fuel cells." Journal of Membrane Science 463: 205-214. [CrossRef]

- Kubec, R., R. B. Cody, A. J. Dane, R. A. Musah, J. Schraml, A. Vattekkatte and E. Block (2010). "Applications of Direct Analysis in Real Time−Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS) in Allium Chemistry. (Z)-Butanethial S-Oxide and 1-Butenyl Thiosulfinates and Their S-(E)-1-Butenylcysteine S-Oxide Precursor from Allium siculum." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58(2): 1121-1128.

- Kumar, V., A. Nandy, S. Das, M. Salahuddin and P. P. Kundu (2015). "Performance assessment of partially sulfonated PVdF-co-HFP as polymer electrolyte membranes in single chambered microbial fuel cells." Applied Energy 137: 310-321. [CrossRef]

- Lanzotti, V., G. Bonanomi and F. Scala (2013). "What makes Allium species effective against pathogenic microbes?" Phytochemistry Reviews 12(4): 751-772.

- Lanzotti, V., F. Scala and G. Bonanomi (2014). "Compounds from Allium species with cytotoxic and antimicrobial activity." Phytochemistry Reviews 13(4): 769-791. [CrossRef]

- Leong, J. X., W. R. W. Daud, M. Ghasemi, K. B. Liew and M. Ismail (2013). "Ion exchange membranes as separators in microbial fuel cells for bioenergy conversion: A comprehensive review." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 28: 575-587. [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D. R. (2006). "Bug juice: harvesting electricity with microorganisms." Nature Reviews Microbiology 4(7): 497-508. [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D. R. (2006). "Bug juice: harvesting electricity with microorganisms (vol 4, pg 497, 2006)." Nature Reviews Microbiology 4(10): 797-797. [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D. R. and K. P. Nevin (2013). "Electrobiocommodities: powering microbial production of fuels and commodity chemicals from carbon dioxide with electricity." Current Opinion in Biotechnology 24(3): 385-390. [CrossRef]

- Min, B., S. Cheng and B. E. Logan (2005). "Electricity generation using membrane and salt bridge microbial fuel cells." Water Research 39(9): 1675-1686. [CrossRef]

- Quero, F., M. Nogi, K.-Y. Lee, G. V. Poel, A. Bismarck, A. Mantalaris, H. Yano and S. J. Eichhorn (2011). "Cross-Linked Bacterial Cellulose Networks Using Glyoxalization." ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 3(2): 490-499. [CrossRef]

- Rabaey, K., G. Lissens, S. Siciliano and W. Verstraete (2003). "A microbial fuel cell capable of converting glucose to electricity at high rate and efficiency." Biotechnology Letters 25(18): 1531-1535. [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.-W., J. Reddy and X. Luo (2015). "Isolation of cellulose nanocrystals from onion skin and their utilization for the preparation of agar-based bio-nanocomposites films." Cellulose 22(1): 407-420. [CrossRef]

- Roldán, E., C. Sánchez-Moreno, B. de Ancos and M. P. Cano (2008). "Characterisation of onion (Allium cepa L.) by-products as food ingredients with antioxidant and antibrowning properties." Food Chemistry 108(3): 907-916. [CrossRef]

- Saka, C. and Ö. Sahin (2011). "Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions by using cold plasma- and formaldehyde-treated onion skins." Coloration Technology 127(4): 246-255. [CrossRef]

- Salak, F., S. Daneshvar, J. Abedi and K. Furukawa (2013). "Adding value to onion (Allium cepa L.) waste by subcritical water treatment." Fuel Processing Technology 112: 86-92.

- Salvi, D. T. B., H. S. Barud, J. M. A. Caiut, Y. Messaddeq and S. J. L. Ribeiro (2012). "Self-supported bacterial cellulose/boehmite organic–inorganic hybrid films." Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology 63(2): 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Schroder, U., F. Harnisch and L. T. Angenent (2015). "Microbial electrochemistry and technology: terminology and classification." Energy & Environmental Science 8(2): 513-519. [CrossRef]

- Shao, W., S. Wang, H. Liu, J. Wu, R. Zhang, H. Min and M. Huang (2016). "Preparation of bacterial cellulose/graphene nanosheets composite films with enhanced mechanical performances." Carbohydrate Polymers 138: 166-171. [CrossRef]

- Singha, S., T. Jana, J. A. Modestra, A. Naresh Kumar and S. V. Mohan (2016). "Highly efficient sulfonated polybenzimidazole as a proton exchange membrane for microbial fuel cells." Journal of Power Sources 317: 143-152. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-Z., G. Peter Kingori, R.-W. Si, D.-D. Zhai, Z.-H. Liao, D.-Z. Sun, T. Zheng and Y.-C. Yong (2015). "Microbial fuel cell-based biosensors for environmental monitoring: a review." Water Science and Technology 71(6): 801-809. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Y. Hu, Z. Bi and Y. Cao (2009). "Improved performance of air-cathode single-chamber microbial fuel cell for wastewater treatment using microfiltration membranes and multiple sludge inoculation." Journal of Power Sources 187(2): 471-479. [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.-C., X.-N. Sun and Y. Xiong (2015). "A novel hybrid anion exchange membrane for high performance microbial fuel cells." RSC Advances 5(6): 4659-4663. [CrossRef]

- Tao, H. C., X. Y. Wei, L. J. Zhang, T. Lei and N. Xu (2013). "Degradation of p-nitrophenol in a BES-Fenton system based on limonite." Journal of Hazardous Materials 254: 236-241. [CrossRef]

- Tursun, H., R. Liu, J. Li, R. Abro, X. Wang, Y. Gao and Y. Li (2016). "Carbon Material Optimized Biocathode for Improving Microbial Fuel Cell Performance." Frontiers in Microbiology 7(6). [CrossRef]

- Winfield, J., L. D. Chambers, J. Rossiter, J. Greenman and I. Ieropoulos (2014). "Towards disposable microbial fuel cells: Natural rubber glove membranes." International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 39(36): 21803-21810. [CrossRef]

- Winfield, J., I. Ieropoulos, J. Rossiter, J. Greenman and D. Patton (2013). "Biodegradation and proton exchange using natural rubber in microbial fuel cells." Biodegradation 24(6): 733-739. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N. e. a. (2013). "Bio-electro-Fenton system for enhanced estrogens degradation." Bioresource Technology 138: 136-140. [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y.-C., Y.-Y. Yu, X. Zhang and H. Song (2014). "Highly Active Bidirectional Electron Transfer by a Self-Assembled Electroactive Reduced-Graphene-Oxide-Hybridized Biofilm." Angewandte Chemie International Edition 53(17): 4480-4483.

- Yong, Y. C., X. C. Dong, M. B. Chan-Park, H. Song and P. Chen (2012). "Macroporous and Monolithic Anode Based on Polyaniline Hybridized Three-Dimensional Graphene for High-Performance Microbial Fuel Cells." Acs Nano 6(3): 2394-2400. [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y. C., Y. Y. Yu, C. M. Li, J. J. Zhong and H. Song (2011). "Bioelectricity enhancement via overexpression of quorum sensing system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-inoculated microbial fuel cells." Biosensors & Bioelectronics 30(1): 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y. C., Y. Y. Yu, Y. Yang, J. Liu, J. Y. Wang and H. Song (2013). "Enhancement of extracellular electron transfer and bioelectricity output by synthetic porin." Biotechnology and Bioengineering 110(2): 408-416. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Y. He, J. Zhang, L. Ma, Y. Li and J. Wang (2016). "Constructing dual-interfacial proton-conducting pathways in nanofibrous composite membrane for efficient proton transfer." Journal of Membrane Science 505: 108-118. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F., R. C. Slade and J. R. Varcoe (2009). "Techniques for the study and development of microbial fuel cells: an electrochemical perspective." Chemical Society Reviews 38(7): 1926-1939. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T., Y.-S. Xu, X.-Y. Yong, B. Li, D. Yin, Q.-W. Cheng, H.-R. Yuan and Y.-C. Yong (2015). "Endogenously enhanced biosurfactant production promotes electricity generation from microbial fuel cells." Bioresource Technology 197: 416-421. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).