1. Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are among the leading causes of global morbidity and mortality [

1,

2,

3,

4]. CHD is the leading single cause of death and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost worldwide, disproportionately affecting low- and middle-income countries. It accounts for approximately 7 million deaths and 129 million DALYs annually, posing a significant economic burden [

3]. Registry data indicate an annual all-cause mortality rate of 1.2–2.4% among CHD patients, with 0.6–1.4% due to fatal cardiovascular events [

5].

COPD prevalence estimates vary depending on the diagnostic criteria used. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study reports an age-standardized prevalence of 2% to 5%, affecting around 328 million people worldwide [

6]. In contrast, studies applying the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria suggest a higher prevalence of 9% to 12%, corresponding to 300–400 million individuals [

2]. COPD is currently the third leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for about 2.8 million deaths annually, or 4.8% of all deaths [

1]. Notably, 50% to 80% of these deaths are due to respiratory causes, most commonly occurring during exacerbations [

3].

Infectious agents are responsible for up to 80% of COPD exacerbations, with bacterial infections accounting for nearly half. Recent evidence confirms the role of bronchopulmonary infections in triggering exacerbations and reveals a correlation between exacerbation severity and the type of microbial flora identified [

7]. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenzae are the predominant pathogens, causing around 50% of infectious exacerbations in patients with a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV

1), above 50% of the predicted value [

7].

COPD and CHD share common risk factors, pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical features, and together serve as synergistic predictors of poor prognosis [

8]. As COPD progresses, it may lead to pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and progression of CHD. In affected individuals, left ventricular dysfunction further reduces exercise tolerance and is frequently accompanied by right ventricular impairment. Ultimately, the decline in physical activity caused by both conditions significantly diminishes quality of life [

9].

In the general population, cardiovascular risk rises following acute respiratory infections. A similar pattern is observed in COPD patients, where frequent exacerbations are associated with increased rates of myocardial infarction and other cardiac events. During these episodes, levels of cardiac biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP), troponin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are elevated. These biomarkers are independently linked to increased mortality [

10].

Given the substantial overlap in risk factors, clinical burden, and poor outcomes associated with COPD and CHD, preventive strategies have become essential in managing patients with both conditions. Vaccination is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of comprehensive care. The 2023 GOLD report recommends pneumococcal vaccination for COPD patients to reduce the incidence of pneumococcal pneumonia [

2]. Similarly, the 2021 ESC Guidelines recommend influenza and pneumococcal vaccination for patients with CHF [

11]. These guidelines underscore the shift toward integrating vaccination into routine disease management rather than treating it as an adjunct. Emerging evidence further supports the role of pneumococcal vaccination in reducing exacerbation frequency, hospitalizations, pneumonia incidence, while improving key clinical and functional outcomes in COPD patients [

12,

13]. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of the 13-valent conjugated pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13) on CAP cases, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations and survival in individuals with COPD and CHD.

2. Methods and Materials

This prospective, long-term observational study began in 2012 and enrolled 483 male patients diagnosed with COPD and CHD. Male-only participation was intended to eliminate potential hormonal influences on outcomes. Participants were stratified into three groups based on PCV13 vaccination status and comorbidities: Group 1 included vaccinated patients with COPD only (n = 140); Group 2 included vaccinated patients with both COPD and CHD (n = 167); and Group 3 included unvaccinated patients with COPD (n = 176). The mean age at baseline was 62.64 years (IQR: 58.12-68.76). Follow-up assessments were conducted at years one, five, and ten. By year ten, survival rates were 74 in Group 1, 72 in Group 2, and 34 in Group 3.

The study adhered to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standards, ensuring data integrity, patients’ rights, and confidentiality. Ethical approval was granted by the Local Ethics Committee of the Regional Clinical Hospital (Protocol No. 8, dated 21 October 2012). All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1. Procedures

COPD was diagnosed according to GOLD 2011, [

14]. while CHD was identified based on the 2006 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for stable angina pectoris [

15]. Only patients with stable angina classified as functional classes II to IV were included.

All participants underwent comprehensive clinical and instrumental evaluations. Spirometry was performed using the MIR SPIROLAB I device (MIR, Italy), electrocardiography (ECG) with the 6-channel Sardiovitat-1 (Schiller, Austria) after 10 minutes of rest, and echocardiography (ECHO) using the Vivid-E9 ultrasound system (General Electric, USA). Dyspnea severity was assessed using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale (0-4 points) [

16,

17]. Exercise tolerance was measured using the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) test [

18].

The primary endpoints were incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), COPD exacerbations, and hospitalization rates over a 10-year follow-up. Secondary endpoint included all-cause mortality over 10 years.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R (v4.1.2) and Python (v3.11.5). Descriptive statistics were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis’ test, with multiple comparisons adjusted via the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Pearson’s correlation was applied to normally distributed variables. Incidence of primary outcomes per 1,000 patients were computed as the number of cases in each group divided by the number of participants in each group and multiplied by 1,000 (

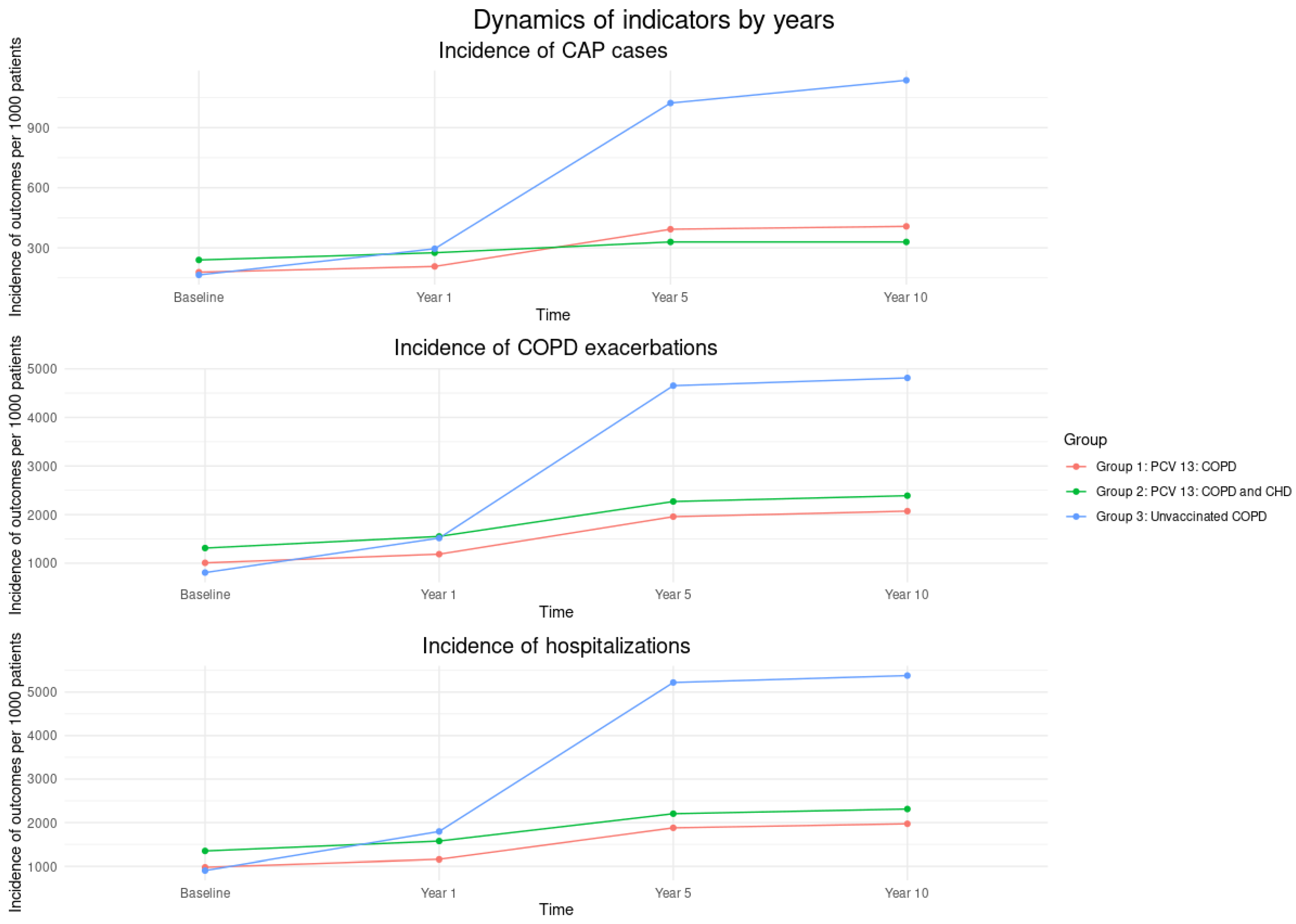

Figure 2).

Generalized linear models with Poisson distribution were assessed the effect of vaccination status on primary outcomes (CAP, exacerbations, hospitalizations), with model fit evaluated using overdispersion and likelihood ratio tests. Survival analysis was performed using

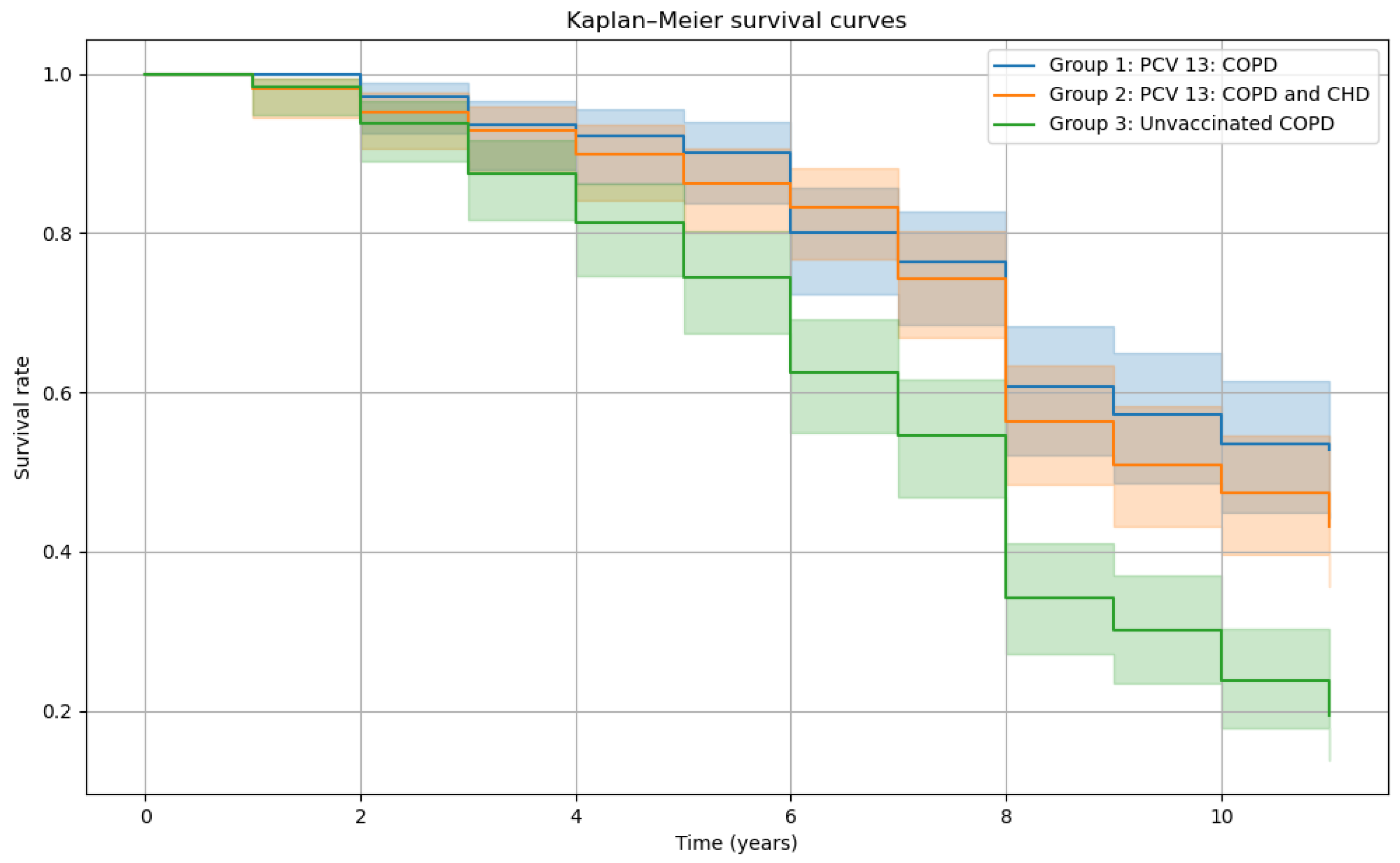

Cox proportional hazards regression, with model quality assessed using the log-likelihood ratio tests and the concordance index. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using the lifelines package.

3. Results

The baseline characteristics of patients are summarized in

Table 1. A total of 483 male patients were enrolled: 307 vaccinated with PCV13 and 176 unvaccinated. Group 2 (vaccinated with both COPD and CHD) had a slightly shorter COPD history (

p=.012), lower oxygen saturation (median 88%,

p=.021) reduced FEV

1 (

p=.032), and a shorter 6-minute walk distance (

p=.014) compared to other groups. No significant differences were observed in age, smoking history, COPD stage, angina class, or rates of pneumonia, exacerbations, hospitalizations, or dyspnea scores.

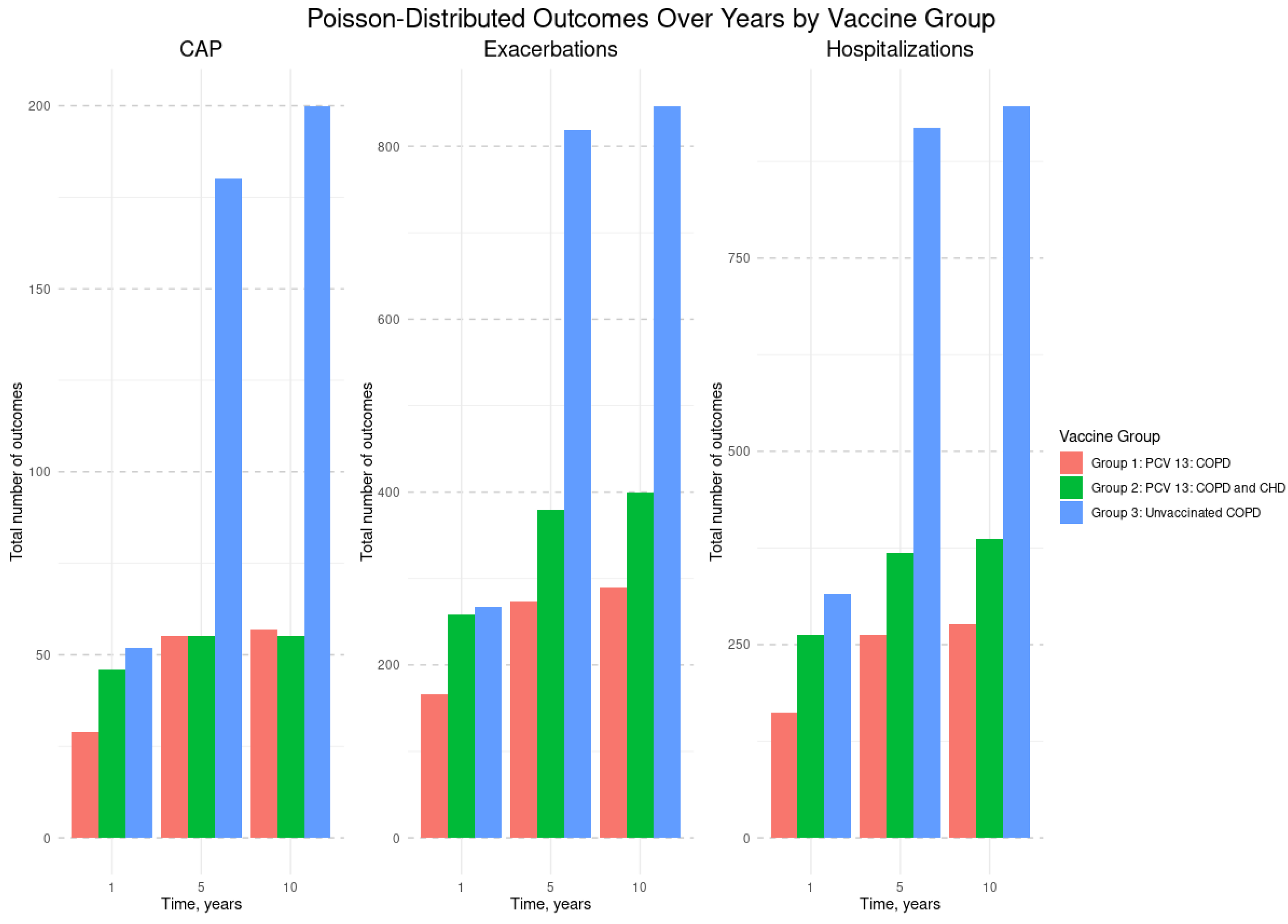

Figure 1 shows that Group 3 (unvaccinated COPD patients) had the highest total number of CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations at years 1, 5, and 10 than Groups 1 and 2 (vaccinated with PCV13).

Figure 2 presents the incidence rates of CAP, COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations per 1,000 patients over time. Across all outcomes, Group 3 (unvaccinated COPD patients) consistently showed the highest incidence at each time point, while Groups 1 and 2 (vaccinated with PCV13) maintained lower and relatively stable rates throughout the follow-up period.

Figure 1.

Total number of CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations by vaccine group and by year. Abbreviations: CAP - Community-Acquired Pneumonia; COPD - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CHD - Coronary Heart Disease; PCV13 - 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Study Groups: Group #1: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with both COPD and CHD; Group #2: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with COPD only; Group #3: Unvaccinated, diagnosed with COPD.

Figure 1.

Total number of CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations by vaccine group and by year. Abbreviations: CAP - Community-Acquired Pneumonia; COPD - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CHD - Coronary Heart Disease; PCV13 - 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Study Groups: Group #1: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with both COPD and CHD; Group #2: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with COPD only; Group #3: Unvaccinated, diagnosed with COPD.

Figure 2.

Incidence of CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations per 1000 patients by vaccine group and by year. Abbreviations: CAP - Community-Acquired Pneumonia; COPD - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CHD - Coronary Heart Disease; PCV13 - 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Study Groups: Group #1: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with both COPD and CHD; Group #2: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with COPD only; Group #3: Unvaccinated, diagnosed with COPD.

Figure 2.

Incidence of CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations per 1000 patients by vaccine group and by year. Abbreviations: CAP - Community-Acquired Pneumonia; COPD - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CHD - Coronary Heart Disease; PCV13 - 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Study Groups: Group #1: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with both COPD and CHD; Group #2: Vaccinated with PCV13, diagnosed with COPD only; Group #3: Unvaccinated, diagnosed with COPD.

Table 2 reports the results of separate generalized linear models for CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations. Vaccination with PCV13 was significantly associated with fewer CAP cases in COPD only patients, but not in those with both COPD and CHD. Over time, CAP, exacerbations, and hospitalizations increased significantly (

p<.0001 for years 5 and 10), but vaccinated groups showed significantly lower rates of all outcomes compared to the unvaccinated group. Interaction effects revealed that both vaccinated groups had significantly fewer cases at years 5 and 10 across all models (

p<.0001). Baseline values for each outcome were significant predictors of future events.

Cox proportional hazards modeling showed that both vaccinated groups had significantly lower mortality risk compared to the unvaccinated group. Group 1 (vaccinated COPD patients) had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.48 (95% CI: 0.35-0.65), and Group 2 (vaccinated patients with COPD and CHD) had an OR of 0.56 (0.43-0.73), all

p-values <.05. Older age was significantly associated with higher mortality risk (OR:1.04, 95% CI: 1.01-1.06,

p<.05). Kaplan-Meier survival curves (

Figure 3) demonstrated consistently higher survival probabilities over 10 years in both vaccinated groups compared to the unvaccinated group, with Group 3 showing the steepest decline in survival.

The leading cause of death in Group 3 (unvaccinated COPD) was CAP (61.2%), followed by progressive respiratory failure (31.6%). In contrast, Group 2 (vaccinated with COPD and CHD) had more diverse causes, with CHF (23.2%) and myocardial infarction (6.5%) contributing significantly. Group 1 (vaccinated with COPD) had the lowest mortality from CAP (5.5%) and the highest proportions of deaths attributed to other cases (81.7%).

4. Discussion

The results of our 10-year observations study showed that PCV13 vaccination was associated with significantly lower rates of CAP, COPD exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality over a 10-year period. At baseline, the patient groups showed no statistically significant differences in key clinical and functional parameters, including disease severity, and all patients received optimized standard therapy. However, vaccinated patients with COPD and CHD had a slightly shorter COPD history, lower, oxygen saturation, and reduced FEV1, and shorter 6-minute walk distance compared to other groups, indicating more severe health status due to the presence of COPD and CHD comorbidity. These baseline characteristics and treatment adjustments allow for a confident assessment of the impact vaccination on clinical outcomes and survival. In the unvaccinated group, mortality increased progressively from the first year, peaking by year 5 and 10. In contrast, vaccinated patients with isolated COPD or combined COPD and CHD showed no such trend.

This long-term prospective observational study demonstrated significant vaccine effects of PCV13 on preventing CAP among patients with COPD and CHD. The key finding is sustained vaccine effects over a 10-year follow-up period. Cardiovascular disease exacerbates COPD symptoms, and observations data link CAP to increased risk of serious cardiac events, including myocardial infarction [

19,

20].

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the most common cause of CAP globally [

21,

22]. Pneumococcal pneumonia and sepsis are independent long-term risk factors for adverse cardiac outcomes [

23]. Myocardial infarction occurs in 5-7% of patients hospitalized with pneumococcal pneumonia, [

24]. with the highest risk in the initial days post-infection. This may be driven by systemic inflammation triggering localized changes in atherosclerotic plaques, increasing the risk of rupture [

20]. Despite these associations, studies on the impact of pneumococcal vaccination on cardiovascular outcomes remain limited, especially in long-term contexts [

25]. Therefore, the 10-year follow-up data in patients with combined pathology offer valuable insights into the role of pneumococcal infection in cardiovascular risk and disease progression.

A key strength of this study is the inclusion of only male patients which helped minimize the influence of hormonal factors on clinical outcomes. This approach is supported by GOLD 2011 data indicating a higher prevalence of COPD among men [

26]. However, the rising incidence of COPD in women and their distinct pathophysiologic response, particularly to tobacco smoke, must be acknowledged as a limitation to generalizability [

26]. By the 10-year of follow-up, the mean age of surviving patients was 71.0 years, highlighting age as a constant, non-modifiable risk factor for both COPD and CHD.

While the study provides valuable long-term observational data on the impact of PCV13 on survival and disease management, its non-randomized design limits the strengths of casual inference. The observed benefits, though promising, should be interpreted with caution. Future randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the vaccine’s effects on survival, functional outcomes, and cardiovascular risk in broader and more diverse populations.

5. Conclusions

PCV13 was associated with reduced risk of CAP, COPD exacerbations, and hospitalizations and improved long-term survival in patients with COPD and CHD. These findings underscore the clinical value of PCV13 and support its prioritization in immunization programs and clinical guidelines for patients with chronic respiratory and cardiovascular comorbidities. The observed benefits highlight the potential of PCV13 as a preventive strategy not only against infectious complications but also in mitigating disease progression and improving long-term outcomes in high-risk populations. Future randomized controlled trials are essential to confirm these findings, particularly regarding the vaccine’s impact on respiratory and cardiovascular outcomes. Further research should also explore the underlying mechanisms linking pneumococcal infection to adverse cardiac events and evaluate the long-term cost-effectiveness of widespread PCV13 immunization in comorbid populations.

Data Availability

Datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to S.V. Kupriyanov for help in statistical processing of the study data.

References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. Feb 21 2023;147(8):e93-e621. [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD: 2024 report. 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/.

- Wang JJ. Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:2939-2944. [CrossRef]

- Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. Aug 29 2023;148(9):e9-e119. [CrossRef]

- Duggan JP, Peters AS, Trachiotis GD, Antevil JL. Epidemiology of Coronary Artery Disease. Surg Clin North Am. Jun 2022;102(3):499-516. [CrossRef]

- Boers E, Barrett M, Su JG, et al. Global Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Through 2050. JAMA Netw Open. Dec 1 2023;6(12):e2346598. [CrossRef]

- Avdeev S, Truschenko, NV, Gaynitdinova, VV, Soe, AK, Nuralieva, GS. Treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Terapevticheskii arkhiv. 2018;90(12):68-75. [CrossRef]

- Svendsen CD, Kuiper KKJ, Ostridge K, et al. Factors associated with coronary heart disease in COPD patients and controls. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0265682. [CrossRef]

- Elkhapery A, Hammami MB, Sulica R, et al. Pulmonary Vasodilator Therapy in Severe Pulmonary Hypertension Due to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (Severe PH-COPD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. Dec 16 2023;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Alter P, Lucke T, Watz H, et al. Cardiovascular predictors of mortality and exacerbations in patients with COPD. Sci Rep. Dec 19 2022;12(1):21882. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. Sep 21 2021;42(36):3599-3726. [CrossRef]

- Ignatova GL, Avdeev SN, Antonov VN. Comparative effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination with PPV23 and PCV13 in COPD patients over a 5-year follow-up cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021 Aug 5;11(1):15948. PMID: 34354113; PMCID: PMC8342495. [CrossRef]

- 13 Ignatova G, Avdeev, Sb, Antonov, VN, Blinova, EV. Ten-year analysis of the efficacy of vaccination against pneumococcal infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulmonologiya. 2023;33(6):750-758. [CrossRef]

- Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Rodriguez-Roisin R. The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (GOLD)--why and what? Clin Respir J. Oct 2012;6(4):208-14. [CrossRef]

- Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: The Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. Jun 2006;27(11):1341-81. [CrossRef]

- Stenton C. The MRC breathlessness scale. Occupational Medicine. 2008;58(3):226-227. [CrossRef]

- Perez T, Burgel PR, Paillasseur JL, et al. Modified Medical Research Council scale vs Baseline Dyspnea Index to evaluate dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1663-72. [CrossRef]

- Matos Casano HA, Anjum F. Six-Minute Walk Test. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Musher DM, Abers MS, Corrales-Medina VF. Acute Infection and Myocardial Infarction. Reply. N Engl J Med. Apr 11 2019;380(15):e21. [CrossRef]

- Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax. Jan 2012;67(1):71-9. [CrossRef]

- Said MA, Johnson HL, Nonyane BA, et al. Estimating the burden of pneumococcal pneumonia among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic techniques. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60273. [CrossRef]

- Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Manresa F, Dorca J, Gudiol F, Carratalà J. Risk stratification and prognosis of acute cardiac events in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect. Jan 2013;66(1):27-33. [CrossRef]

- Musher DM, Rueda AM, Kaka AS, Mapara SM. The association between pneumococcal pneumonia and acute cardiac events. Clin Infect Dis. Jul 15 2007;45(2):158-65. [CrossRef]

- Addario A, Célarier T, Bongue B, Barth N, Gavazzi G, Botelho-Nevers E. Impact of influenza, herpes zoster, and pneumococcal vaccinations on the incidence of cardiovascular events in subjects aged over 65 years: a systematic review. Geroscience. Dec 2023;45(6):3419-3447. [CrossRef]

- Sin DD, Man SF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(1):8-11. [CrossRef]

- Abdool-Gaffar MS, Ambaram A, Ainslie GM, et al. Guideline for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--2011 update. S Afr Med J. Jan 2011;101(1 Pt 2):63-73.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).