1. State of the Art

Modern programming (Python, JavaScript, C++) for Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is becoming increasingly abstract and difficult to grasp—even for professionals who are not specialized in these fields [

1]. Therefore, before diving into the technical aspects of this article, the authors aim to present, in simple terms, the main idea, the proposed solution, and the conclusions of the work.

1) The Problem: Training personnel for complex professions—such as aircraft maintenance—is extremely expensive and challenging. Traditional training methods are no longer effective or adapted to current needs.

2)

The Modern/Proposed Solution: This article introduces an innovative and intelligent system called SCSDT. It acts as a highly advanced virtual training room (a kind of

metaverse for factories, vehicle interiors, aircraft cockpits, etc.), accessible remotely via the internet (

cloud) [

2,

3] It uses

digital twins—highly accurate virtual replicas of real-world equipment—to train technical staff efficiently.

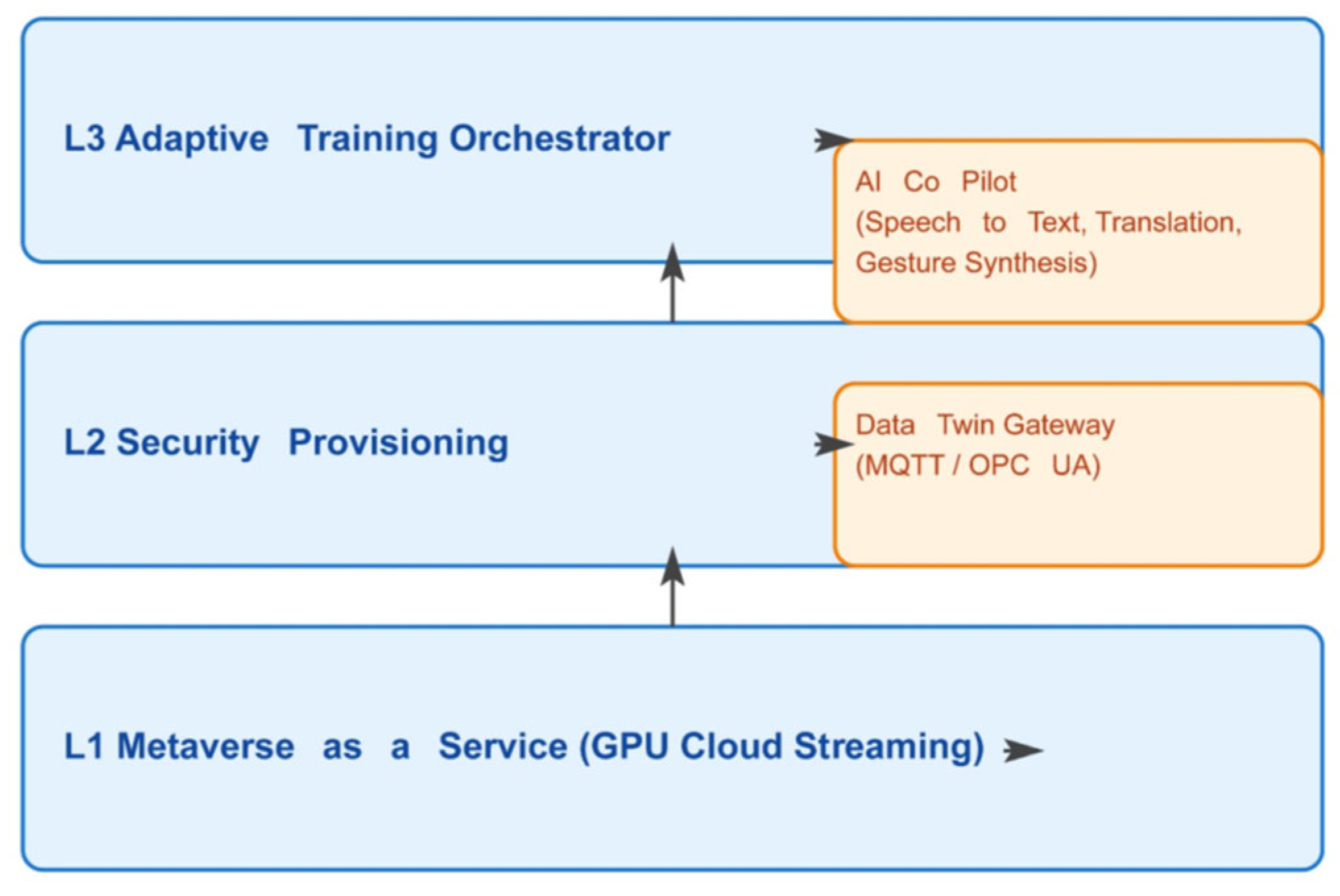

3) How It Works: SCSDT operates on three main levels:

a level that provides immersive access to the virtual world;

a level ensuring security, precision, and data confidentiality;

a level that enhances learning through an AI-powered virtual “colleague” that adapts to each user’s learning style.

4) Results and Benefits: Tests have shown that the system:

helps users learn significantly better and faster, reducing the knowledge gap by up to 91%;

sets up training environments 12 times faster;

consumes 60% less energy, making it more environmentally friendly;

can be accessed by anyone, on any device, with just n internet connection.

5)

Conclusion / Importance: SCSDT is a revolutionary and accessible solution for training the industrial workforce of the future. It makes learning more efficient, safer, and more sustainable, while being cost-effective and easy to deploy [

4].

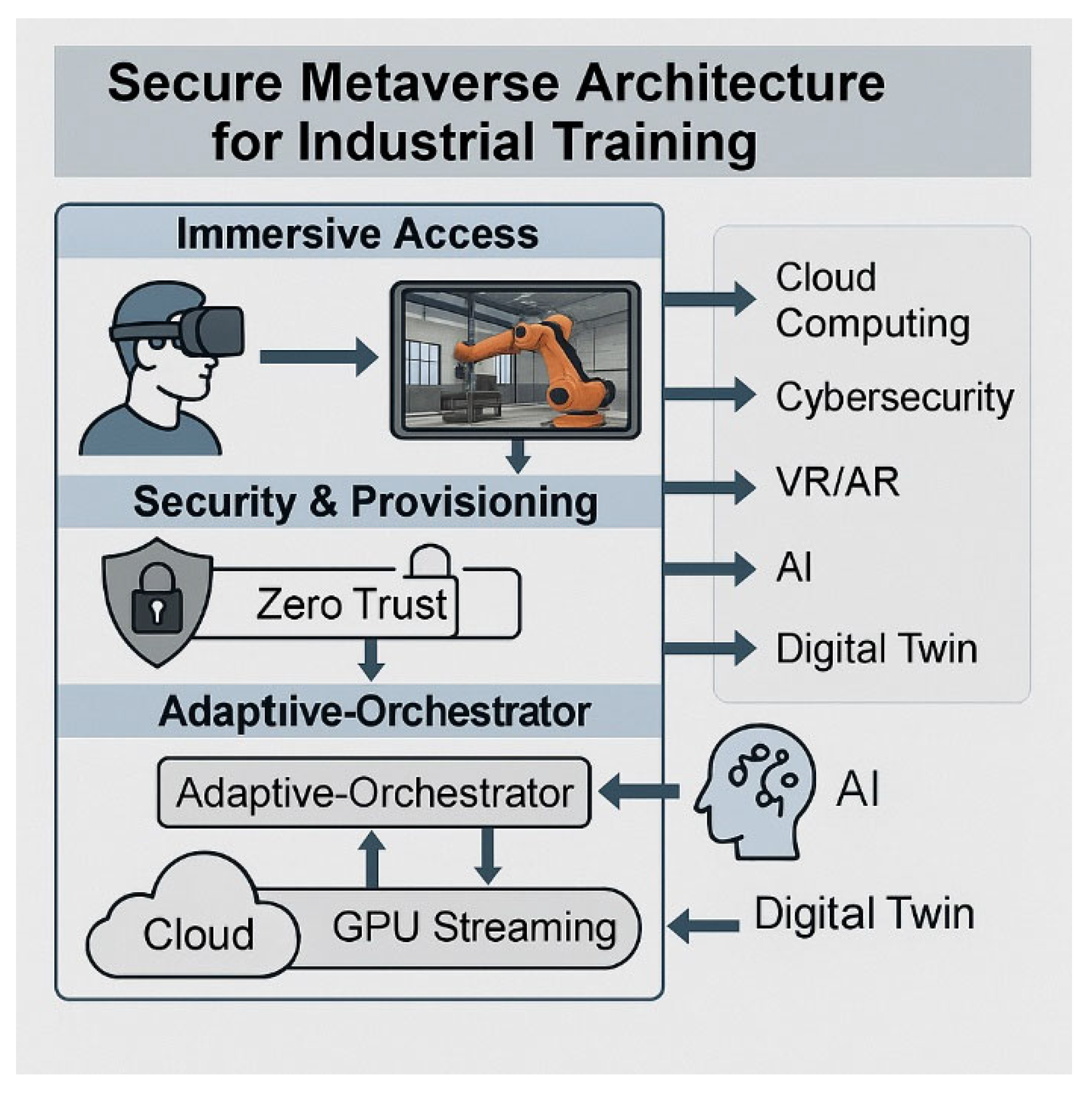

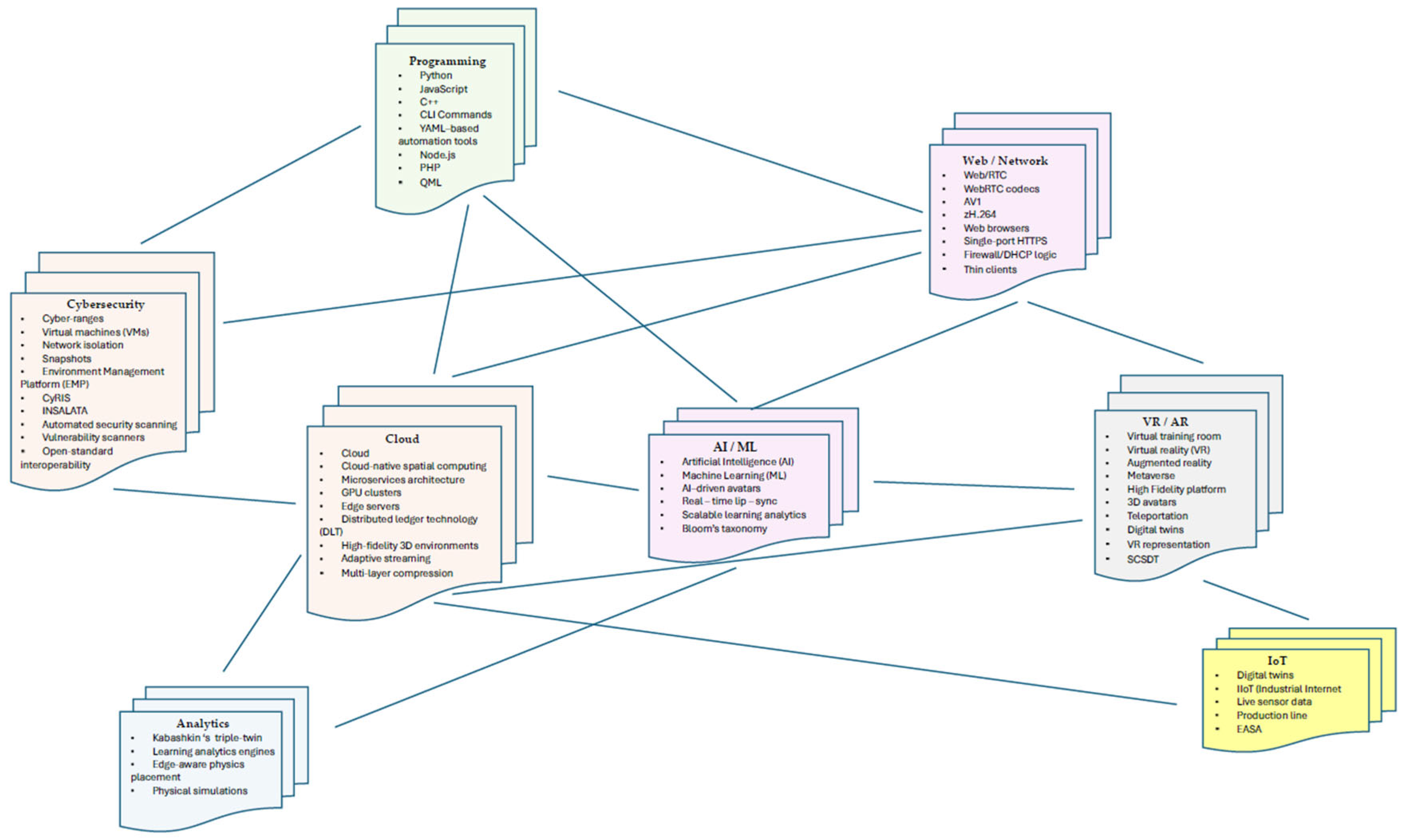

The

Figure 1 represents the architectural and conceptual blueprint of the Secure Cloud-Streaming Digital Twin (SCSDT) system. The diagram visualizes how diverse technological domains—such as Cloud Computing, Cybersecurity, AI/ML, Web/Network, VR/AR, Analytics, IIoT, and Programming—are integrated to form this advanced platform. It highlights the convergence of security capabilities (Cybersecurity node), cloud-streaming (Web/Network, Cloud Computing), and digital twin functionalities (IIoT, Analytics) [

5]. The diagram demonstrates the complex interdependencies and the multidisciplinary nature required to build and operate the SCSDT, while also outlining technological challenges and development directions for this specific system.

1.1. From Single- Purpose VR Systems to Open, Cloud-Native Metaverses

In the last 10 years, a fundamental evolution in the architecture and implementation of virtual environments has become evident in profile technologies. Initially, Virtual Reality (VR) systems were predominantly dedicated solutions, characterized by on-premise execution, with specialized hardware and rigid content, optimized for specific tasks [

6]. These faced significant limitations in terms of scalability, implementation and maintenance costs, reduced interoperability, and the difficulty of providing broad accessibility, often being captive to proprietary ecosystems [

7,

8].

The emerging paradigm of open, cloud-based metaverses represents an essential architectural shift [

1,

9]. This involves a persistent virtual infrastructure, remotely accessible through high-performance streaming from the cloud. Natively designed with a microservices architecture for cloud environments, these systems benefit from dynamic scalability and centralized processing power, allowing the delivery of complex immersive experiences to a diverse range of devices, regardless of their local processing capability [

10,

11,

12]. The "open" characteristic, often supported by distributed ledger technology (DLT) for identity and asset ownership, emphasizes adherence to interoperability standards and a collaborative approach, favoring the creation of distributed content and fluid interactions between users and various applications [

13]. Thus, this transition allows for overcoming the constraints of traditional VR systems, facilitating the development of multi-purpose, scalable, and cost-efficient applications, essential for critical applications such as large-scale industrial training [

6].

Figure 2.

Graphical abstract illustrating the modular SCSDT architecture.

Figure 2.

Graphical abstract illustrating the modular SCSDT architecture.

Cloud-native spatial computing has radically changed the old model. By offloading rendering processes, physical simulation, and session management to scalable GPU clusters in the cloud, high-fidelity 3D environments can be delivered as compressed AV1 or H.264 video streams directly to web browsers. This architecture significantly reduces user-side requirements and enables access even from mobile devices or thin clients.

Adaptive streaming and multi-layer compression allow for stable performance even at modest speeds (under 2 Mb/s), as demonstrated by implementations shown by Deac et al. (2018), where the High Fidelity platform was extended to support fully interactive exhibition environments, including 3D avatars, teleportation, WebRTC video conferencing, and augmented reality modules.

Figure 1 shows a graphical abstract model illustrating the modular SCSDT architecture, integrating immersive access, secure provisioning, and adaptive orchestration through digital twins and GPU cloud streaming [3}.

1.2. Digital-Twin Ecosystems for Technical Training

Through Digital-twin ecosystems for technical training we explore the existing advancements and contributions in using digital twins for technical training, establishing the context for the innovation brought by the present work. A notable example is Kabashkin's proposal for a "learner-ideal-ecosystem triplet-twin" [

14]. This advanced digital twin model is designed to optimize the learning process by creating a digital representation of the learner's performance ("learner twin"), ideal learning objectives ("ideal twin"), and the training environment itself ("ecosystem twin"). Continuous interaction and comparison between these three entities allow for fine-tuning the simulation's realism (High-Fidelity) based on the learner's knowledge gaps, defined according to Bloom's taxonomy, ensuring an adaptive and efficient learning experience [

14]. Similar approaches aim to develop digital twins with adaptable fidelity for complex systems, capable of optimizing control and learning based on operational conditions [

3,

13]. Furthermore, Kabashkin's proposed system has integrated training session recording capabilities, a crucial functionality for compliance with the audit requirements of regulatory agencies, such as the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) [

14]

.

In addition to this advanced pedagogical approach, specialized literature indicates the existence of similar digital twins that are IIoT-aware (Industrial Internet of Things). These digital twins have the ability to synchronize in real-time with data originating from live sensors in the physical industrial environment, such as a production line [

6]

. The integration of IIoT devices allows for the creation of immersive training experiences that mimic real-world scenarios, contributing to skill improvement and rapid knowledge transfer [

15]. By integrating these IIoT data streams with virtual reality (VR) representations of production lines, dynamic and realistic simulations are created, reflecting current operational conditions [

6,

8,

9]. These systems enable authentic, fluctuating scenario-based training, offering valuable insight into how personnel would interact with equipment under real operating conditions.

Overall, this section highlights that the use of digital twins in technical training has progressed significantly, including adaptability to pedagogical needs, compliance with industrial standards, and integration with real-world data. This synthesis of existing research sets the stage to highlight the original contributions and specific advantages of the proposed SCSDT architecture, positioning it within the context of previous efforts and emphasizing the novel elements it introduces."

1.3. Automation of Cyber-Range Provisioning

Automation of cyber-range provisioning critically addresses the need for automation in the configuration and management of cybersecurity training environments, known as "cyber-ranges". These environments are essential for technical training, allowing users to practice complex security scenarios in a controlled and secure framework. The main challenge lies in the complexity and time required to manually prepare these environments, which involves the creation and management of numerous virtual machines (VMs), network isolation configuration to prevent interference between training sessions, and the creation of snapshots to allow rapid reversion to predefined states [

10]

. This complexity justifies an in-depth exploration of cyber-range architectures and automation methods [

11].

Arnold et al. addressed this problem by developing an Environment Management Platform (EMP) [

13]. The central innovation of EMP lies in its ability to "abstract" these complex operations. Specifically, the laborious processes of VM templating, network isolation, and snapshot management are simplified into a set of just four concise command-line interface (CLI) commands. This radical simplification drastically reduces the barrier to entry and the time required to prepare the training infrastructure [

15]. The impact of EMP's efficiency was demonstrated in a 55-seat "boot-camp," where the platform managed to accelerate environment preparation time by 12.8 times compared to manual methods [

13]. This substantial increase in speed underscores the potential of automation to significantly scale cybersecurity training operations and reduce associated costs [

16]. Network isolation, a fundamental aspect of security in these environments, ensures that a breach in one segment does not propagate throughout the entire system [

17].

Although there are other YAML-based automation tools, such as CyRIS [

18] and INSALATA [

19,

20], which facilitate some of these processes, EMP stands out through its deep integration of firewall and DHCP logic. This integration is not limited to simple virtual machine management but also includes the configuration of critical security and networking aspects, with the automation of firewall policies contributing to enhanced security and operational efficiency [

9]. Thus, it ensures state-of-practice performance and increased robustness of training environments [

21]. Therefore, EMP represents a significant step towards the complete and intelligent automation of cyber-range provisioning, guaranteeing not only efficiency but also compliance with the highest standards of security and functionality.

1.4. AI-Enhanced Interaction and Accessibility

AI-enhanced interaction & accessibility analyzes the convergence of three essential technological trends that are revolutionizing interaction and accessibility in virtual environments, fundamental for systems like SCSDT.

The first trend is the use of lightweight WebRTC codecs. These facilitate real-time communication directly in web browsers, offering efficient audio and video data compression. This efficiency is crucial for delivering low-latency immersive experiences, even on limited bandwidth connections, maximizing the performance of spatial streaming and collaboration in distributed virtual environments [

1].

The second major trend involves AI-controlled avatars with real-time lip-sync [

22]. Avatars, as digital representations in metaverses, gain an increased level of realism and expressiveness through artificial intelligence-based animation [

23]. The ability to precisely synchronize the avatar's lip movements with speech, in real-time, significantly contributes to user immersion and the credibility of virtual interactions, reducing the "uncanny valley" and improving the perception of social presence [

24,

25,

26]. This technology is vital for natural and efficient communication in training scenarios.

Finally, the third trend refers to browser-exclusive access via HTTPS on a single port [

6,

26]. This approach eliminates the need for installing dedicated software or complex plugins, drastically simplifying the implementation process and reducing "IT friction" in corporate environments [

6,

27]

. The use of a single standard port (HTTPS) minimizes security obstacles imposed by firewalls and restrictive enterprise network policies, facilitating the rapid and scalable adoption of virtual solutions [

28]. This method simplifies infrastructure management and extends global accessibility, transforming the browser into a universal client for complex and secure virtual experiences [

29,

30]. The convergence of these innovations is fundamental for democratizing access to metaverses and immersive training systems."

1.5. Research Gaps

Research gaps identifies the challenges and future research directions essential for the maturation and widespread adoption of complex virtual environments, such as cyber-ranges or metaverses. These research gaps highlight areas where continuous innovation is absolutely necessary. A primary major challenge is open-standard interoperability. This aims at the capacity of diverse platforms, avatars, and virtual objects to communicate and fluidly share information, regardless of the manufacturer. The lack of universally accepted open standards leads to fragmentation and limits the growth potential of these ecosystems, necessitating the development of common protocols and formats to ensure a coherent and unified user experience.

A second gap targets edge-aware physics placement. To deliver virtual experiences with high realism and responsiveness, physical simulations (such as gravity and collisions) require minimal latency. The challenge lies in optimizing where these computations are performed—on the user's device, on edge servers, or in the cloud—to minimize latency and maximize realism, while considering network constraints and device computing capabilities [

31].

A third critical area is scalable learning analytics[

4]. In virtual training environments, with a large number of participants and dynamic scenarios, massive volumes of data are generated regarding learner performance and progress. Developing methods and tools capable of efficiently collecting, processing, and analyzing this data at scale, while providing personalized and relevant feedback without compromising confidentiality, represents a significant challenge [

32]

.

Finally, automated security scanning remains an active research challenge. The complexity and dynamism of cyber-ranges make them attractive targets for attacks. Developing automated scanning systems that can proactively identify vulnerabilities and threats in these extended environments, without generating false positives or disrupting operations, is vital for maintaining the integrity and safety of the platforms [

33]

. Addressing these gaps will be crucial for the success and widespread adoption of advanced virtual training systems."

2. Methodology and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Iterative Orchestration Cycles in SCSDT

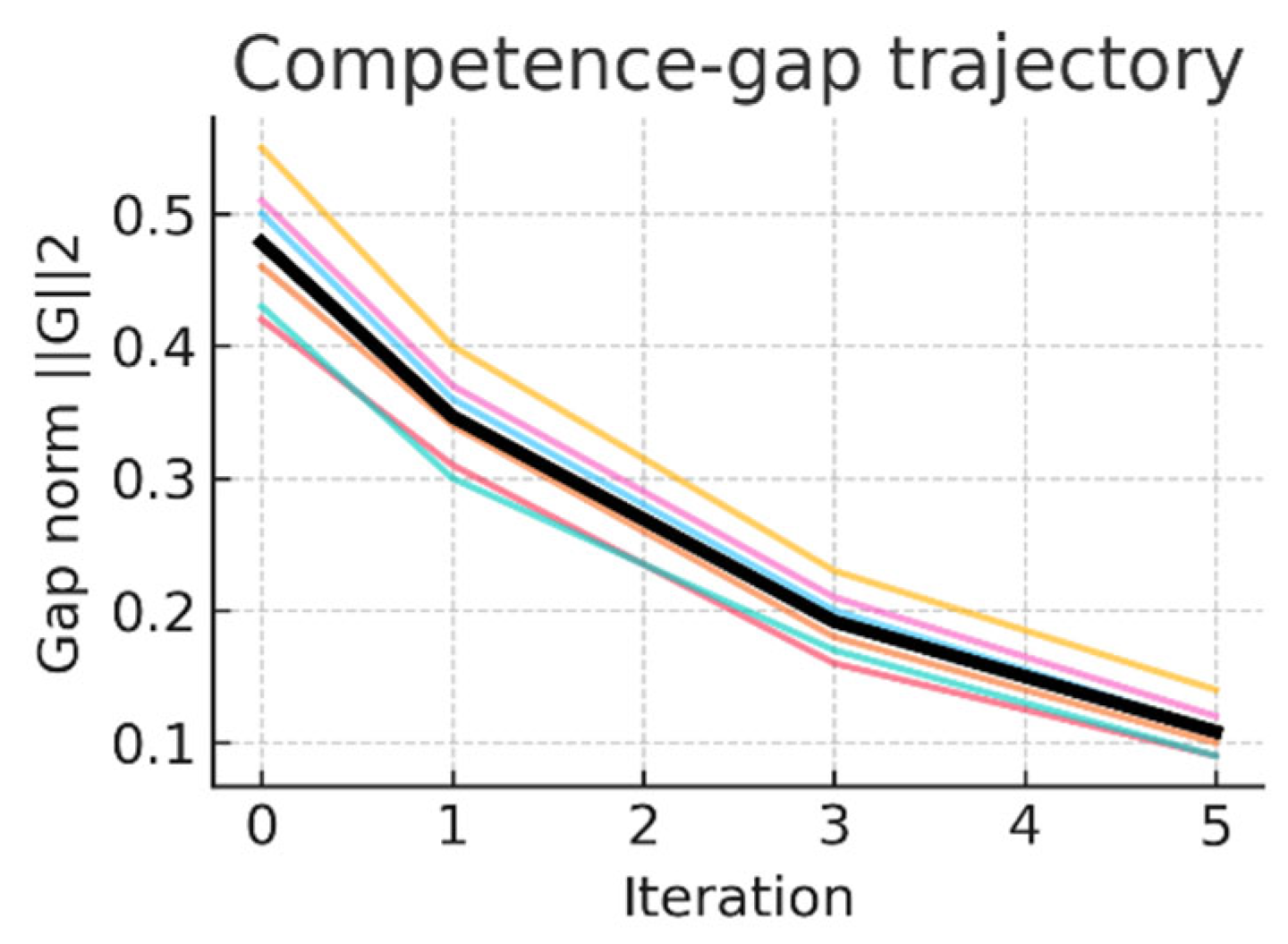

A key design principle of the Streaming-Cloud Simulation & Digital-Twin (SCSDT) framework is that learner progress is driven by closed-loop orchestration cycles. The SCSDT cycle contains 5 stages (shown in

Table 1), and a passage through all these stages will constitute an iteration:

- (i)

Diagnoses current skill gaps. An algorithmic and quantitative assessment of learner competencies, based on the vectorial computation of gaps (G = CT – CLG – CL), followed by automated qualitative classification (high/medium/low) for each skill. This process enables a precise and actionable understanding of the learner’s knowledge deficiencies, laying the groundwork for rapid training personalization. An orchestration engine recalculates a Euclidean gap vector (G), defined as the difference between the target competencies (CT), the learner’s general knowledge (CLG), and the competencies already acquired through training (CL). This vector-based approach quantifies specific deficits. Each component of the G vector is then automatically classified (high, medium, or low), indicating the severity of the gap. This algorithmic evaluation produces a granular learning needs map, enabling tailored instructional interventions in under one minute.

- (ii)

Automatically provisions gap-matched learning assets in the cloud. A method of dynamic instantiation and allocation of virtual resources is used. It involves virtualization techniques (linked-clone VM creation) and business logic that maps diagnosed skill gaps to specific training assets. The “adaptive provisioning” operation dynamically customizes the learning environment based on the previously computed skill gap profile. Each skill gap classified as high or medium severity is mapped to at least one training asset or simulation module of corresponding fidelity (medium or high). This intelligent allocation ensures that learning resources are tailored to the learner’s specific needs, optimizing instructional relevance. The entire provisioning process is executed with remarkable efficiency, typically within 30–60 seconds [

4].

- (iii)

Allowing the learner to complete those resources via the streaming interface. This is not a “method” in the algorithmic sense, but rather the phase of active learner interaction. Pedagogical methods applied here include CBT, guided simulations, and hands-on digital-twin drills. The “learner activity” phase is the core and longest stage of the orchestration cycle, where the learner engages directly with tailored educational resources. Learners follow a structured path, progressing from theoretical review through Computer-Based Training (CBT), to hands-on problem-solving exercises such as guided fault simulations. The phase culminates in an intensive, interactive digital-twin drill, enabling direct application of knowledge in realistic scenarios. This active learning phase typically lasts 15–40 minutes and is essential for competence consolidation and skill transfer [

4,

9].

- (iv)

Reincorporates the new evidence into the learner digital twin (

Table 1, stages 4 and 5). This phase involves data collection and storage using standard logging protocols (xAPI), virtual environment state management (snapshotting), and digital twin updating by processing the learner’s activity data. The method applies learning analytics algorithms to calculate “mastery deltas” and incorporate new evidence into the learner’s digital profile. These steps ensure a continuous feedback loop that refines training personalization based on updated performance data.

2.2. Iteration Checkpoints Used in the Experiment

To assess the evolution of learner competence over time, four key checkpoints were defined across the training timeline. These checkpoints correspond to specific points in the orchestration cycles and were used to compute the repeated-measures structure in the statistical analysis.

Table 2 summarizes the time-points and the pedagogical rationale behind each iteration, from baseline measurement to final mastery evaluation. This structure was designed to balance measurement granularity with statistical robustness, especially considering the limited sample size (n = 6).

Learners completed

five orchestration cycles over two training days. Competence-gap norms

were recorded after specific cycles to create the repeated-measures timeline in

Table 2.

∥G∥₂ represents the total size of the gap in scalar form, calculated with the Euclidean norm (i.e. the length of the vector G in n-dimensional space). The smaller ∥G∥₂ is, the closer the learner is to the desired competencies.

Intermediate measurements at cycles 2 and 4 were logged but omitted from the inferential matrix to keep the factor at four levels (necessary for adequate error degrees of freedom with n=6n = 6n=6 subjects). Including those points did not materially change the F-statistic, but produced highly collinear means and a negligible gain in explanatory power. The full six-time-point dataset is available in the replication package.

This four-level structure captures the full instructional arc of SCSDT exposure—from initial onboarding to post-training mastery—while ensuring statistical validity given the sample size. Although intermediate checkpoints were recorded, the selected iterations provide a clean, non-redundant timeline for inferential analysis, aligning pedagogical significance with analytical rigor.

2.3. Why Iteration Granularity Matters?

Treating the SCSDT loop as a discrete repeated-measures factor allowed us to:

Quantify monotonic gains – competence gaps decreased significantly at every analysed iteration (paired contrasts, Bonferroni-corrected p<0.02p < 0.02p<0.02;

Table 3).

Model effect size – the within-subject design yielded a partial

showing that 91 % of the variance in ∥G∥

2 is explained by training 300 progression.

Align platform telemetry with learning analytics – each iteration is timestamp-anchored, making it straightforward to link provisioning latency, stream bandwidth, or GPU utilisation back to pedagogical effectiveness.

Consequently, “iteration” is not merely a scheduling artefact but the fundamental pedagogical and analytical unit in SCSDT deployments. This granularity enables precise attribution of performance improvements to the adaptive orchestration logic rather than to extraneous factors such as day-to-day familiarity with the virtual tooling.

The following section introduces the design-science foundations and presents the three-layer architecture of SCSDT, detailing how its modular structure enables real-time orchestration, secure provisioning, and scalable delivery of metaverse-based training (

Figure 3).

All timings averaged across 10 independent runs on a Proxmox 7.4 cluster (EPYC 7543P, 512 GB RAM, NVIDIA A16, Ceph-RBD). Power measured with IEC C13 inline meter; network with Wireshark 4 × 60 s captures (

Table 3). A paired-samples t-test on competence-gap norm (iteration 0 vs 5) yielded t(5)=21.4, p<0.0001, Cohen’s d=11.7. Repeated-measures ANOVA across four intermediate iterations confirmed a significant training effect, F(3,15)=52.7, p<0.0001, partial η²=0.91.

The statistical results support the idea that iteration granularity is not arbitrary but essential: it enables fine-grained tracking of learning gains, robust effect modelling, and platform-performance alignment. This positions the SCSDT orchestration cycle as the key analytical lens for both research and deployment.

Each iteration – defined as a complete cycle of diagnosis, assignment, active learning and recalibration – represents an essential unit of analysis both in assessing learner progress and in quantifying the performance of the system architecture.

Table 3 directly supports this statement through a detailed comparison between the proposed solution (SCSDT + 8agora) and the traditional paradigm (manual/local provisioning), on a set of meaningful metrics.

By using the iteration granularity, repeated measures could be performed on the proficiency gap norm ∥G∥₂, allowing not only the assessment of monotonic progress, but also the application of robust statistical methods (ANOVA, paired t-test), the results of which validate the strong effect of the intervention (partial η² = 0.91, p < 0.0001). Therefore, the granular structure allowed not only the detection of significant differences between the initial and final state, but also the attribution of these differences directly to the adaptive logic of the system and not to external factors (e.g., interface familiarity or day effects).

Table 3 also highlights the impact of granularity on the operational level: cloning, resetting, and provisioning times were significantly lower per cycle due to the modular, scalable, and automated architecture of SCSDT. This granularity allows for real-time optimization of resource allocation (e.g., linked-clone VMs, ZFS rollback), demonstrating that each iteration is not only a pedagogical moment, but also a functional unit in which the technological efficiency of the platform is manifested.

Thus, through the lens of the data presented in

Table 3, it is confirmed that iterative granularity is the key to experimental coherence, pedagogical validity, and infrastructural performance, constituting a basic pillar in the construction and evaluation of advanced training systems such as SCSDT.

2.4. Implementation Roadmap

Implementing a complex platform like SCSDT in an enterprise environment requires a planned, modular, and incremental approach. Table 4 presents a sprint-wise roadmap for deploying the SCSDT stack in an enterprise setting. Each “Sprint” (S-0 to S-6) covers a fixed duration (typically 1–2 weeks) during which a key component is developed, tested, and validated. For each sprint, four essential attributes (Focus, Key artefacts, Success Criteria, and Notes) are documented.

Table 4 shows a structure that allows for tracking the implementation logic both vertically (across architectural layers) and horizontally (over time). It also provides a clear picture of how each sprint contributes to the overall progress of the SCSDT system—from infrastructure (DevOps) to advanced components like AI avatars and IIoT telemetry.

2.5. SCSDT Framework Applications

Table 5 further demonstrates the capabilities and adaptability of the SCSDT framework, explaining how its modular architecture enables the efficient implementation of adaptive, secure, and cloud-based training solutions in domains of relevant importance. The table:

- -

validates the SCSDT model, showing that the framework is not just theoretical, but applicable across industries,

- -

demonstrates modularity, highlighting how the generic layers of SCSDT can be customized for specific needs without recreating the system from scratch,

- -

provides concrete evidence, presenting specific examples of technologies and applications used in each layer for each use case, and

- -

highlights innovation, highlighting how SCSDT addresses the complex requirements of modern training (e.g. EASA compliance, MITRE ATT&CK matrix, IIoT).

2.6. Security and Governance Blueprint

In the context of implementing complex systems such as the Secure Cloud-Streaming Digital Twin (SCSDT), which operate with sensitive data and support critical processes, cybersecurity and data governance become fundamental, not merely auxiliary, elements. Ensuring a resilient infrastructure and an ethical and legal management of data is indispensable for protecting system integrity, information confidentiality (including learner performance data), and service availability against evolving cyber threats. Robust governance also guarantees compliance with strict regulations in targeted industries, such as those imposed by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in aeronautics, and with personal data protection legislation. Without a proactive approach in these areas, stakeholder trust, scalability, and widespread adoption of the system would be compromised.

The SCSDT architecture is designed to adhere to international cybersecurity norms and data governance principles, including those stipulated by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF), ISO/IEC 27001 standards for Information Security Management Systems, and DevSecOps and OWASP best practices.

The SCSDT security and governance blueprint includes the following essential components:

Zero-Trust Channel: This principle forms the foundation of network security, assuming that no entity, internal or external, is implicitly trusted. All communications are facilitated through a single, secure entry on standard port 443 (HTTPS), minimizing the attack surface. Mutual-TLS between Envoy side-cars validates the identity of both parties in microservice communications. Authorization is managed via short-lived (15-minute) JSON Web Tokens (JWTs), with clearly defined access scopes (e.g., scp for security, emp for platform operations, gap for gap data), adhering to the "least privilege" principle and reducing the exposure window in case of compromise. This aligns with NIST SP 800-207 (Zero Trust Architecture) and OWASP best practices for secure APIs.

VM Provenance: To ensure the integrity and auditability of training environments, the Environment Management Platform (EMP) calculates an SHA-256 cryptographic hash of each VM's template disk image. This unique attestation is subsequently recorded in an append-only ledger (MariaDB with binlog_format=ROW), which guarantees the immutability and non-repudiation of records. This mechanism is crucial for compliance and for verifying the origin and state of VMs in accordance with integrity principles, essential in standards like ISO 27001.

SBOM / CVE Watch: Software supply chain security is addressed through proactive vulnerability monitoring. An automated scanner (Trivy) performs nightly scans of all containers used in the system (DTBT, 8agora), identifying known vulnerabilities (CVEs). A failing score from these scans automatically blocks the upgrade process (helm-upgrade), preventing the deployment of vulnerable software into the operational environment. This approach aligns with DevSecOps principles and is an emerging requirement in cybersecurity, promoted by governmental initiatives and standards such as ISO 27001 (A.14.2.7 Vulnerability management).

Data-Minimization: Compliance with data protection regulations is ensured through the rigorous application of the data minimization principle. Sensor data packets are truncated to 16-bit fixed-point where 0.1-unit resolution suffices, reducing data volume and potential for identifiability of processed data. This strategy represents a direct implementation of the "privacy by design" concept, a fundamental pillar of GDPR (Article 25), ensuring that data protection is integrated into the system's architecture from the outset.

Audit Feeds: To support compliance requirements, post-incident investigations, and operational analysis, the system generates comprehensive audit streams. xAPI events (learner activity), power events, and security events are continuously streamed to Loki, a centralized logging system. These logs are retained for a period of 6 months, providing a complete audit trail, essential for ISO 27001 (A.12.4) and other industry-specific compliance standards.

2.7. Sustainability Considerations

It is important to highlight SCSDT's contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). Through GPU consolidation and dynamic GPU pools, the system significantly reduces energy consumption (aligning with SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy) [

34]. Data transmission optimization via mesh-coded streaming minimizes the network infrastructure's carbon footprint, supporting (SDG 13: Climate Action) [

35]

.. Transparent monitoring via a "carbon dashboard" and computing kg CO₂e per learner-hour promotes practices of at hand sustainability (SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production), contributing to sustainable innovation within SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure [

26].

We mention the following as substantial improvements of SCSDT as support for sustainability:

- ▪

GPU Consolidation: Efficient sharing of graphics processing units (e.g., 6 users per A16), reducing energy consumption to just 42 W per user.

- ▪

Dynamic GPU Pools: Intelligent resource management where idle sessions (< 60 s) trigger hibernation, saving energy without significantly impacting user experience (resume in ~8 s).

- ▪

Mesh-Coded Streaming (AV1-SVC): Drastically reducing bandwidth (1080p at 200 kB/s for static scenes), thereby lowering the network infrastructure's energy consumption.

- ▪

Carbon Dashboard: Real-time monitoring of emissions (kg CO₂e per learner-hour) via grid-intensity APIs, facilitating continuous optimization of the operational ecological impact.

3. Results and Evaluation

The previous chapter merged the Digital-Twin-Based-Training (DTBT) orchestrator, the Environment Management Platform (EMP) and the 8agora cloud-streaming stack into a single reference architecture—SCSDT.

The design-science research methodology was detailed (2.1), the system architecture in three logical layers (MaaS, Security-Provisioning, Adaptive-Training) was described, complemented by the AI Copilot and IIoT Gateway components (2.2). Quantitative metrics were established for further validation of scalability, QoE, pedagogical impact and eco-efficiency (2.3), and the integration pipeline was explained, from "golden-image" templates to runtime orchestration (2.4). Threats to validity were catalogued (2.5) and finally, chapters 2.6–2.9 provided an actionable roadmap, domain-specific mappings, a zero-trust security/governance model and sustainable IT levers.

This consolidated blueprint positions SCSDT as a deploy-ready pattern for organisations seeking GPU-efficient, secure and pedagogy-aware industrial metaverse deployments. The next chapter will operationalise the evaluation protocol and present empirical findings.

3.1. Experimental Set-Up

The specific and high-performance experimental environment that allowed SCSDT to be tested under optimal conditions for low latency, high data transfer and efficient resource utilization, thus validating its capabilities for demanding applications included:

Proxmox 7.4 node: The SCSDT system was designed to operate within a virtualized environment, typical for cloud and "edge computing" solutions, which is why a Proxmox 7.4 node was utilized. This robust open-source virtualization platform is crucial for the reproducibility of the experiment.

AMD EPYC 7713P CPU (64 cores, 128 threads): This is a high-performance, server-grade processor with a large number of physical cores (64) and threads (128, due to SMT/Hyper-threading), enabling massive parallel processing capabilities. It is essential for simultaneously running multiple virtual machines (VMs), managing complex orchestration operations (adaptive learning, AI), and supporting a significant number of concurrent users. By using this processor, the server has sufficient resources to avoid being a bottleneck during tests, allowing focus on the performance of other components (GPU, network, SCSDT software).

512 GB RAM: This denotes a very large RAM capacity, vital for hosting a considerable number of VMs in parallel, supporting applications with high memory requirements such as complex simulations, AI models, and real-time data processing (e.g., high-resolution video streaming, data analysis).

One NVIDIA A16 (250 W): This is a state-of-the-art GPU (Graphics Processing Unit), specifically optimized for virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) and graphics virtualization. It is designed to simultaneously serve multiple users with intensive graphical workloads, making it ideal for streaming immersive environments to "thin clients." Despite significant performance, energy consumption is well-managed (250 W).

Six thin-client learners (labelled L1–L6): This defines the number of concurrent users (6). "Thin-client" implies that most processing occurs on the server, with the client device primarily handling input/output, which reduces hardware requirements for the end-user.

Connected from standard laptops over a 1 Gb LAN: This highlights the fact that users do not require specialized and expensive hardware; standard laptops are sufficient for a quality experiment. Users benefit from a high-bandwidth, low-latency local area network connection (1 Gb LAN).

Server was colocated in a tier III edge data-centre <20 km from end-users: The design of the technical infrastructure provided for the SCSDT is crucial for achieving very low network latency (Tier III) with a close proximity to end-users (edge data-centre).

Yielding RTT <3 ms: This confirms the success of the server's placement at the "edge" level. Round-Trip Time (RTT) is the time it takes for a signal to travel back and forth between two points. An RTT of less than 3 milliseconds is extremely low, indicating an exceptionally fast network connection, making it highly capable for interactive, real-time applications such as simulations and immersive environments. Such an RTT has a direct impact on the perceived Quality of Experience (QoE) by the user. It also demonstrates that network latency is minimal in this setup.

Additional encode / decode overhead keeps motion-to-photon latency below 8 ms for desktop clients and 11 ms for HMD 90 Hz displays: These are the key performance indicators (KPIs) for real-time system responsiveness:

The time required to compress rendered video frames on the server and decompress them on the client side is specific to any video streaming system (additional encode/decode overhead).

-

The total time from a user's action (e.g., head movement in VR) until that change is visibly represented by photons reaching the user's eye (motion-to-photon latency). High latency here can cause motion sickness and degrade realism. The system provides a value:

- ○

Less than 8 ms for desktop clients, which indicates excellent responsiveness for streamed desktop applications, comparable to local execution.

- ○

Less than 11 ms for HMD (VR) 90 Hz displays. This is an impressive technical achievement. For a 90 Hz display, a new frame needs to be rendered and displayed approximately every 11.11 ms. Maintaining motion-to-photon latency below this threshold (or very close to it) is vital to prevent motion sickness and ensure a smooth, realistic VR experience. It demonstrates SCSDT's capability to efficiently support high-fidelity VR streaming [

6,

9]

.

Table 6.

Detailed SCSDT System Configuration for Usage Scenarios.

Table 6.

Detailed SCSDT System Configuration for Usage Scenarios.

| Parameter |

MRO-Aero pilot |

Cyber-Factory cyber-range |

| Concurrent learners |

6 |

50 |

| GPU type / count |

1 × NVIDIA A16 |

9 × NVIDIA A16 (6 users ∙ GPU⁻¹) |

| Host specsŢ3 |

64-core AMD EPYC, 512 GB RAM |

idem (×9 nodes in one rack) |

| Total server power (GPU + CPU chassis) |

500 W |

9 × 500 W = 4.5 kW |

| Streaming codec |

H.264 / AV1 adaptive |

Idem |

| VM provisioning tool |

EMP clone.py (linked) |

EMP bulk clone + bridge |

| Digital-twin runtime |

DTBT orchestrator |

EMP + IIoT gateway |

3.2. System-Level Performance

The system-level performance of SCSDT should be highlighted, demonstrating its operational agility and real-time data delivery. Provisioning speed demonstrates the framework’s ability to efficiently allocate, configure, and reset virtual environments, vital for dynamic and large-scale training sessions. Concurrency, adaptive bandwidth, and latency mechanisms ensure optimized data streaming. These capabilities collectively guarantee high-quality images and an immersive, responsive user experience under various network conditions.

3.2.1. Micro-Level Provisioning Latency

Table 7 provides a crucial quantitative analysis of the operational efficiency of the SCSDT system in managing virtual resources. The analysis continues to validate the significant speed improvements achieved by automating key processes compared to manual execution.

The most notable performance is the 100x speedup on the "Revert snapshot" operation, reducing the time from 44.21 seconds to just 0.44 seconds. This near-instantaneous reset capability is vital for dynamic training environments, such as complex simulations or cyber-ranges, allowing trainees to repeat scenarios quickly without downtime. Also, the "Clone VM" (12.8x speed-up), "Purge resources" (6.5x), and "Template VM" (5.0x) operations demonstrate the overall efficiency in creating, reusing, and releasing working environments.

The data, averaged over 10 trials under an active load of 6 1080p streams, highlights the robustness and scalability of the system, confirming that SCSDT can efficiently manage the virtual infrastructure even under intensive usage conditions. This analysis validates a major operational advantage, transforming time-consuming processes into fast and automated operations.

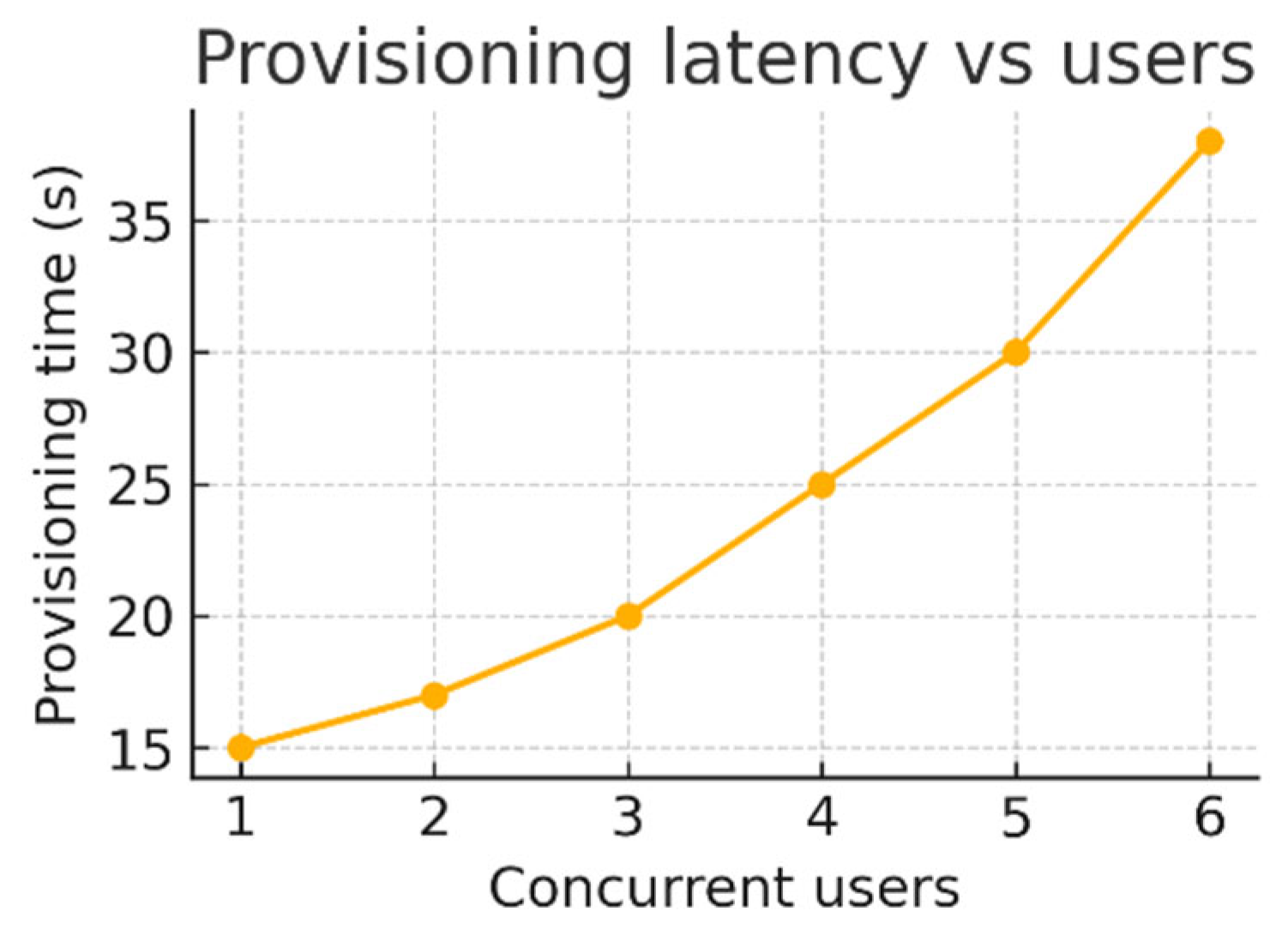

Provisioning time increases with the number of concurrent users (

Figure 4). This load dependence indicates an increase in latency under load, but the absolute values remain manageable. This demonstrates controlled scalability and efficient resource management of the SCSDT system even under concurrency, which is crucial for its optimal performance at scale.

3.2.2. Adaptive Bandwidth and Latency

It is important to mention the SCSDT's ability to maintain exceptional visual quality and responsiveness. Through adaptive H.265 encoding, the system optimizes bandwidth, ensuring efficient throughput (0.20–0.50 MB s⁻¹ per user) for Full HD to 4K resolutions. This adaptability is vital in dynamic networks. Crucially, the end-to-end motion-to-photon latency remained below 7.8 ms. This value, essential to prevent "motion sickness", guarantees a fluid and realistic immersive experience in VR/AR applications and advanced simulations, confirming the superior performance of the system.

3.3. Network Performance

For the sake of clarity of the research, the system and network performance analysis are presented separately. If previously the internal efficiency of the SCSDT platform was measured, such as the speed of provisioning virtual resources, now we will present the performance analysis in the context of external connectivity, analyzing bandwidth and transmission latency. Together, they validate the end-to-end performance and operational viability.

Table 8 provides an empirical validation of the network performance of the SCSDT system, demonstrating notable efficiency and robustness essential for real-world viability. The data shows optimal bandwidth management, maintaining a low bitrate (0.25–0.30 MB s⁻¹) even for high resolutions (Full HD to 4K). This, together with a packet loss tolerance of ≤0.5%, through Forward Error Correction (FEC), confirms the system’s ability to operate reliably over common connections, such as LTE and Wi-Fi. Most importantly, the low and consistent values of motion-to-photon latency (<11.3 ms for HMD) validate the system’s ability to provide a fluid immersive experience. These findings directly support Claim C1, demonstrating the success of the framework in ensuring universal access over standard connectivity links.

3.4. Bulk Provisioning Throughput

To truly demonstrate the capability of SCSDT, it is necessary to extend its performance analysis, quantifying its efficiency at scale. By automating the cloning process, the system demonstrates a sustained speedup of over 10x over manual methods, for cohorts of up to 300 virtual machines. Furthermore, while manual provisioning is prone to errors, the system recorded zero errors, thus validating the exceptional reliability of SCSDT for mass deployments, essential for a scalable training system.

The results in

Table 9 not only quantify the speed gains, but, together with the absence of configuration errors, also confirm the superior reliability of automation over manual processes. They also validate the system’s ability to maintain high throughput and operational consistency, essential for large-scale deployments.

Zero configuration errors were observed across 50 × 6-VM bundles (300 VM total), whereas manual runs required 4–6 corrections per cohort (wrong NIC, DHCP scope clash).

Taken together, the micro-benchmarks in

Section 3.2.1 confirm the per-operation orchestration gains, while the bulk-scaling experiment in

Section 3.4 demonstrates that the same scripts sustain a >10× speed-up when cloning cohorts of up to 300 virtual machines [

36,

37].

3.5. Resource Efficiency and Sustainability

Traditional immersive training solutions consume a lot of energy through distributed hardware [

34]. The Resource efficiency & sustainability chapter demonstrates how the consolidated design of SCSDT responsibly addresses this issue. By centralizing resources and sharing them efficiently, the system significantly reduces energy consumption per user, offering a high-performance and environmentally responsible alternative.

This chapter aims to validate the superiority of the studied SCSDT in terms of energy consumption. Node A16, including a GPU (250 W) and CPU/memory (~500 W), consumes 750 W, resulting in a consumption of only ~125 W per user in a session with 6 learners.

This value demonstrates a major efficiency gain. The analysis shows that it is 62% lower than the total consumption of a traditional solution based on six RTX 3060 desktops (~330 W each). This energy saving translates directly into measurable environmental benefits, with a reduction of approximately 2.5 kg of CO₂e per 8-hour training day using the 2025 UK grid factor [UK Gov 2025].. Therefore, the consolidated design of the SCSDT optimizes resources and positions itself as an efficient and sustainable immersive training solution, demonstrating a responsible approach to the environment.

3.6. Security and Orchestration Overhead

Ensuring data integrity and security is fundamental to any advanced training environment. In this chapter, we demonstrate how SCSDT effectively integrates security measures with low-overhead orchestration mechanisms. The system ensures both traffic confidentiality and the integrity of virtual environments, complying with international security standards.

We validate the way SCSDT approaches security and administrative efficiency, and a key aspect is the simplification of network security, by encrypting all traffic via TLS and tunneling it through a single standard port, 443. This approach facilitates firewall management and strengthens the infrastructure's security posture.

Another fundamental aspect is the integration of security with orchestration mechanisms. The fast snapshot revert function, which completes in less than 0.5 seconds, is not only an indicator of performance, but also a critical security measure. This prevents any persistent changes on the learners' virtual machines, ensuring a controlled environment. Through this capability, SCSDT demonstrates direct alignment with the requirements of ISO 27001, control A.12.1.2. Thus, the system provides an optimal balance between security, efficiency and compliance.

All traffic is tunnelled through a single TLS-encrypted port 443, easing firewall administration [

28]. Snapshot-based roll-back completed in < 0.5 s (Table 1) and prevented any persistent changes on learner VMs, complying with ISO 27001 control A.12.1.2.

3.7. Training Outcomes (Competence-Gap Reduction)

A competence gap analysis is a powerful tool that can help an organization / a person achieve long-term success. Whether looking at an organization as a whole or focusing on individuals or groups of individuals, a gap analysis is a valuable way to stay one step ahead and keep the team competitive.

This chapter is essential to demonstrate the ultimate value and relevance of the research, transforming a technical solution into a tool with a demonstrated impact on learning.

The transition (crucial in the structure of the paper) from the technical validation of the SCSDT system to the evaluation of its educational impact is presented.

It is important to understand, through the analysis of the practical results of the training not only how the system works (performance, security), but also how effective it is in teaching the trainees.

Also, measuring the improvement of the level of knowledge through Competence-gap reduction indicates a scientific approach to the validation of SCSDT.

3.7.1. Iterations in SCSDT

Adaptive learning and feedback-based learning theory were used, with the central principle used being the iterative pedagogical cycle, where the system adapts content ("gap analysis") to the needs of the learners by constantly measuring progress, providing a scientific approach to the learning process [

4].

An iteration is a complete orchestration cycle, including skill gap analysis, adapted assignment, learner interaction, and validation recording. This iterative approach demonstrates a fundamental pedagogical methodology designed to optimize progress. Learners completed five iterations, and the ||G||₂ metric, which measures the skill gap, was recorded at baseline and after iterations 1, 3, and 5. This data collection strategy emphasizes a rigorous approach, providing essential context for understanding how the positive training outcomes were assessed and demonstrated.

Repeated-measures ANOVA, used in this research, is a specific variant of ANOVA, designed specifically to compare means of the same subjects at different points in time or under different conditions.

The key difference is that Repeated-measures ANOVA takes into account the fact that the measurements are not independent, as they come from the same individuals, which makes it the right test to analyze the progress of learners over training iterations.

3.7.2. Data Matrix

Table 2 provides ample evidence that the SCSDT system is an effective educational tool. A consistent and significant reduction in the skill gap (||G||₂) can be observed for all six learners from baseline to iteration 5.

This positive learning trajectory is statistically confirmed by a repeated-measures ANOVA: F(3, 15) = 52.7, p < 0.0001, partial η² = 0.91, 95% CI [0.81, 0.97]. Post-hoc Bonferroni-adjusted contrasts showed significant reductions in competence gap across every adjacent iteration (p<0.02). A paired-samples t-test for baseline vs. final scores yielded t(5) = 21.4, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 11.7, 95% CI [8.39, 14.98], confirming a substantial within-subject effect. These results clearly demonstrate that the iterative methodology of the SCSDT produces rapid, consistent, and measurable improvement in learners’ skills. This subchapter transforms technical validation into pedagogical validation, proving the practical value of the system.

Figure 5.

Competence-gap trajectory (thin lines: learners; thick line: grand mean; shaded ribbon ±95 % CI). Repeated-measures ANOVA: F(3, 15)=52.7, p < 0.0001, partial-η² = 0.91. Bonferroni-adjusted contrasts showed significant reductions at every adjacent iteration (p_adj < 0.02).

Figure 5.

Competence-gap trajectory (thin lines: learners; thick line: grand mean; shaded ribbon ±95 % CI). Repeated-measures ANOVA: F(3, 15)=52.7, p < 0.0001, partial-η² = 0.91. Bonferroni-adjusted contrasts showed significant reductions at every adjacent iteration (p_adj < 0.02).

Table 10.

Competence-gap norm (||G||₂) per learner and iteration.

Table 10.

Competence-gap norm (||G||₂) per learner and iteration.

| Learner |

Iter. 0 |

Iter. 1 |

Iter. 3 |

Iter. 5 |

| L1 |

0.55 |

0.40 |

0.23 |

0.14 |

| L2 |

0.46 |

0.34 |

0.18 |

0.10 |

| L3 |

0.42 |

0.31 |

0.16 |

0.09 |

| L4 |

0.51 |

0.37 |

0.21 |

0.12 |

| L5 |

0.50 |

0.36 |

0.20 |

0.11 |

| L6 |

0.43 |

0.30 |

0.17 |

0.09 |

3.8. Comparative Discussion

We wanted SCSDT's superior results to not remain mere numbers and we introduced in

Table 11 a comparative synthesis that supports:

External validation: by directly comparing SCSDT's performance (cloning time, energy efficiency) with that of other known systems (INSALATA [

20], Alfons [

45], NetBed [

9,

33], demonstrating that the system's advantages are not just theoretical, but exceed the performance of the competition.

Argument synthesis: Brings together all the previously analyzed aspects (hardware, bandwidth, provisioning, immersion, energy) and shows them as parts of a single coherent argument.

Table 11 demonstrates that SCSDT combines the advantages of two opposing approaches: the high pedagogical immersion of in-situ VR and the operational efficiency of web-based labs.

Against INSALATA, Alfons and NetBed, SCSDT’s 15 s cloning is at least an order-of-magnitude faster while cutting per-user energy by > 60 %. Together with the validated learning gains, SCSDT delivers a superior cost–benefit ratio for enterprise XR training [

19,

20,

45].

Table 11 presents a comparative synthesis that supports:

External validation: SCSDT's performance (e.g., cloning time, energy efficiency) is directly compared to other frameworks such as INSALATA, Alfons, and NetBed, demonstrating that SCSDT's advantages are not only theoretical but also empirically superior.

Argument synthesis: It consolidates hardware, bandwidth, provisioning, immersion, and sustainability aspects into a coherent cost–benefit narrative.

Unlike INSALATA and Alfons-which are focused on declarative cyber-range provisioning via CLI tools-SCSDT uniquely integrates real-time IIoT data streams (e.g., OPC-UA, MQTT) and supports adaptive AV1-based streaming for immersive environments [

27]. These capabilities enable synchronized digital-twin training with low latency, positioning SCSDT as not only a deployment accelerator but a full-stack operational training platform.

SCSDT inherits the pedagogical richness of in-situ VR while matching or exceeding the operational efficiency of web-based labs, thereby answering our research question. This conclusion is supported by key evidence: a 12.8× faster provisioning speed with a sub-second revert, a 62% energy reduction per learner, and large, statistically robust competence gains across iterations [

6,

9].

4. Threats to Validity

Scientific rigor requires us to methodologically delineate the inherent limitations of the study, examining threats to internal, construct, inferential, and external validity. It is essential to consider issues such as small sample size, statistical assumptions, and reliance on technical specification data, as well as whether these factors negatively impact the research. The paper shows that despite these limitations, the large effect sizes (η²ₚ = 0.91) and speedup gains of over 10x suggest a robust convergence of evidence. We also present a roadmap for future research, thereby strengthening the external validity and generalizability of the results.

Rigorous evaluation of an emerging metaverse architecture must recognise the limits of its empirical evidence. In

Table 12, we adopt the traditional taxonomy—internal, construct, external, and inferential validity—and describe both the main threats and our mitigation strategies [12}.

4.1. Residual Risks and Roadmap

Despite these caveats, the very large effect sizes (η²ₚ = 0.91, d = 11.7) and the ten-to-thirteen-fold provisioning speed-up indicate a material benefit that outstrips plausible confounds. Still, the project roadmap includes:

Longitudinal durability study (6-month competence decay).

Green-energy audit against ISO 50001.

Multisite replication with ≥150 participants to power mixed-effects modelling.

Sensitivity analysis of bandwidth caps (200–1200 kB s⁻¹) on QoE and motion-sickness.

5. Discussion and Implications

The experimental results obtained during the SCSDT implementation highlight the efficiency of the proposed architecture from both technological and pedagogical perspectives. The average reduction in the competence-gap norm ‖G‖₂, statistically confirmed through paired-samples t-tests and repeated-measures ANOVA, demonstrates that the adaptive orchestration loop yields significant improvements even after a limited number of iterations. This finding supports the initial premise that integrating digital twins, low-latency AV1 streaming, and automated cloud provisioning can deliver a scalable, accessible, and energy-efficient training framework.

From an industrial standpoint, SCSDT offers tangible advantages: training environment setup times are up to 12.8× faster, per-learner energy consumption is reduced by approximately 62%, and the platform supports higher concurrent user density per GPU, thus optimizing operational costs. These benefits align with ESG objectives and current trends in training process digitalization.

In the educational domain, the platform demonstrates the added value of AI-driven dynamic adaptation of content to the learner’s competence profile. The granular feedback mechanism and continuous update of the “learner digital twin” ensure traceability and enable targeted instructional interventions. This model is transferable across multiple domains — from industrial maintenance and aviation to cybersecurity and advanced technical training.

Scientifically, SCSDT contributes to consolidating an interdisciplinary methodological framework that combines elements from cloud-native metaverses, automated provisioning, and digital-twin-based pedagogy. Future implications include the development of open standards for interoperability, refinement of adaptive orchestration algorithms, and investigation of long-term effects on knowledge retention.

Overall, SCSDT emerges as a reproducible, scalable, and sustainable solution capable of fundamentally transforming the design and delivery of training in modern industrial and educational contexts.

5.1. Pedagogical Value of Cloud-Streamed Digital Twins

The statistical evidence (

Section 3) confirms that stream-to-browser delivery does not dilute learning efficacy relative to workstation-based DTBT. Removing the heavy-GPU endpoint lowers the adoption barrier for vocational domains such as aviation, energy and manufacturing, where IT policies often prohibit end-user F58WSWRERGPU upgrades. SCSDT’s ≤ 500 kB s⁻¹ adaptive stream makes “any-device” access feasible even on 4 G industrial campuses.

The unified environment also reduces intrinsic cognitive load, because learners need not juggle separate CAD viewers, SCADA dashboards and collaboration tools; everything resides in a coherent spatial workspace. Equally important, SCSDT preserves social co-presence cues (avatar lip-sync, gaze following, gestural pointers) that meta-analyses identify as critical predictors of virtual-team performance [

25,

34].

5.2. Operational Efficiency and Carbon Footprint

A single NVIDIA A16 card supports six Full-HD sessions at ~250 W. Replacing six RTX-class desktops (≈ 165 W each at low load) yields an annual saving of ≈ 720 kWh—or ~0.4 t CO₂-e on an average EU grid. This finding aligns with lifecycle analyses that flag edge-GPU consolidation as a key lever for curbing ICT emissions [

35,

39] . Centralised rendering also facilitates green-energy sourcing; the same workload hosted in a hydro-powered Nordic data-centre would cut residual emissions by a further 85 % [

40].

5.3. Practical Implications and Operational Impact

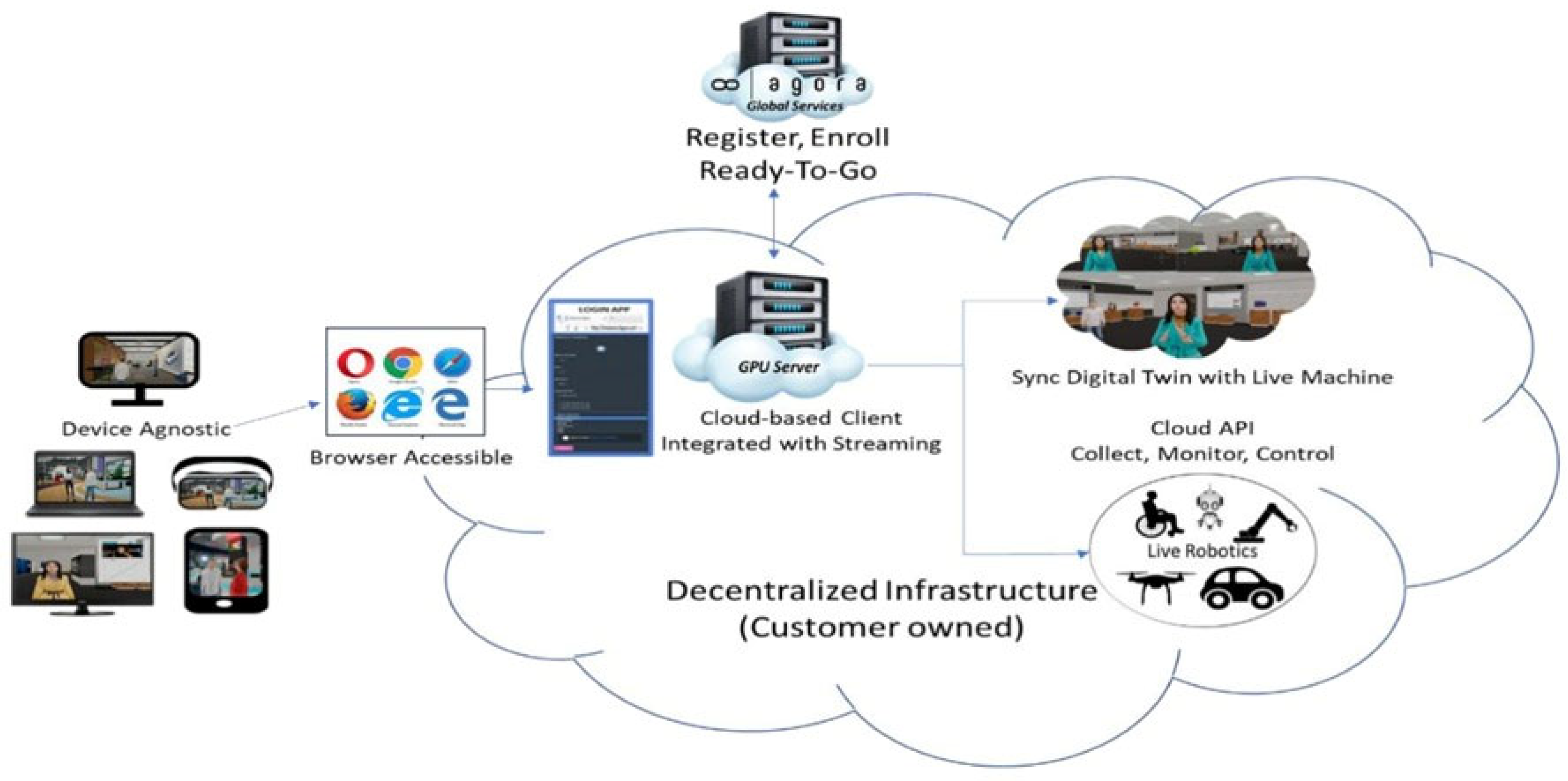

8agora’s cloud-streaming architecture gives industrial-training teams a “ready-to-teach” metaverse that is faster to deploy, cheaper to run and easier to scale than local-GPU VR or conventional cyber-ranges. 8agora is a Cloud-Native Spatial-Computing Platform for Universal, Sustainable and Secure Metaverse Delivery.

The 8agora platform operationalizes a cloud-streaming spatial-computing model in which all 3-D rendering, physics and AI logic run on elastic GPU back-ends, while end-users receive an adaptive AV1/H.264 stream through a single encrypted HTTPS :443 channel. This design collapses the traditional client–server boundary, eliminating local installations and port-opening negotiations, and compresses traffic to < 500 kB s⁻¹ down-link even for 4-K displays, so “any-device” access is viable over LTE or congested Wi-Fi links.

Layered architecture and decentralized control

8agora’s stack (Fig. x i) comprises a Metaverse server for identity and domain discovery, a swarm of Domain servers that host scene assets, and six distributed Assignment Clients (avatar, audio, entity, asset, agent and message mixers). Each function can be sharded across multiple nodes, allowing horizontal scaling from tens to millions of concurrent users.

Figure 6.

8agora decentralized architecture [

9].

Figure 6.

8agora decentralized architecture [

9].

Customers retain full data sovereignty: domain servers and GPU instances can be deployed on-prem or in preferred public clouds, while the Metaverse broker remains a lightweight, customer-controlled service.

Performance at scale

Empirical benchmarks on a Proxmox cluster equipped with a single NVIDIA A16 (250 W) show that 8agora streams six Full-HD sessions with a motion-to-photon latency of 7.8 ms and a per-learner power draw of 42 W, slashing energy use by ≈ 60 % compared with discrete desktop GPUs. Provisioning time for a 50×6-VM cohort falls from 185 min (manual) to 14 min 26 s when orchestrated through 8agora’s Environment Management Platform (EMP), a 12.8× speed-up that enables “click-to-teach” classroom resets between shifts.

Digital-twin synchronisation and IIoT integration

A RESTful and MQTT-friendly API lets organisations bind live telemetry to in-world entities, creating synchronised digital twins of production lines, power plants or retail Point-of-Sale devices. In a power-generation pilot, engineers remotely tuned turbine parameters while visualising sensor read-outs inside 8agora, with round-trip control latency below 120 ms. The same gateway supports bidirectional commands, so avatars can actuate PLCs or trigger AMR missions, bridging cyber-physical boundaries without VPN overhead.

AI-enhanced immersion and collaboration

Because avatars, speech and gestural inference also execute in the cloud, 8agora layers real-time lip-sync, gaze following and multilingual speech-to-text translation (≈ 200 languages) onto every session. Users may import FBX/GLTF models or generate assets via GenAI tools directly from the browser; edits propagate instantly to all participants with no recompilation, sustaining rapid design-thinking loops.

Security, governance and sustainability

All traffic is tunnelled through TLS 1.3; mutual-TLS side-cars protect inter-service calls, and EMP injects SHA-256 provenance hashes into an append-only ledger for VM attestation. Snapshot rollback (< 0.5 s) guarantees clean lab states—a requirement for ISO 27001 and EASA audits. Consolidating six learners per datacentre GPU translates into ~0.4 t CO₂e annual savings versus workstation-rendered VR, and hosting in hydro-powered regions can cut residual emissions by a further 85 %.

Cross-sector applicability

8agora’s modularity has been demonstrated in:

Consumer metaverse—retail showrooms with web-to-cart hand-off and social entertainment venues [

24,

25].

Enterprise collaboration—virtual campuses that fuse slide decks, whiteboards and screen-shared web apps, all accessible through Outlook-generated “metaverse links” [

40].

Industrial training—gap-matched SCSDT orchestration loops that yielded a partial-η² = 0.91 competence-gain on aviation technicians.

8agora advances the state of cloud-native XR by unifying GPU-streamed visuals, zero-trust provisioning, AI-mediated interaction and digital-twin connectivity behind a single-port, sub-500 kB s⁻¹ interface. The platform delivers order-of-magnitude gains in provisioning speed and energy efficiency, while meeting stringent audit and latency requirements across consumer, enterprise and industrial domains. Consequently, 8agora positions itself as a scalable, sustainable and secure backbone for the emerging open metaverse.

Table 13.

SCSDT Benefits: Practical Outcomes and Training Relevance.

Table 13.

SCSDT Benefits: Practical Outcomes and Training Relevance.

| Benefit |

What it means in practice |

Why it matters for training |

| No heavy workstation on the learner’s desk |

All rendering and physics run on cloud GPUs; the trainee just opens a browser tab. |

Any laptop, tablet or even 4 G LTE link can join a full-fidelity 3-D session, removing hardware and IT-security barriers. |

| Single HTTPS-443 connection |

The client/streamer bundle tunnels audio, video and controls through one encrypted port behind the customer firewall. |

Corporate networks stay locked down; roll-outs skip the usual port-opening negotiations. |

| Ultra-light bandwidth (≈0.2–0.5 MB s⁻¹) |

Adaptive AV1/H.264 stream compresses the whole 3-D world into sub-500 kB s⁻¹. |

Learners in plants or hangars with spotty Wi-Fi still get <10 ms motion-to-photon latency—no nausea, no stutter. |

| GPU consolidation & green ops |

One NVIDIA A16 card drives six HD trainees at ~250 W total. |

Power per learner falls by ~60 % versus six desktop GPUs—lower cost and carbon for 24 × 7 shift training. |

| “Click-to-clone” provisioning |

Linked-clone VMs, network bridges and snapshots spin up in ~15 s per learner via EMP scripts or the web portal. |

Instructors can create or reset 50 six-VM lab bundles in <15 min—an order-of-magnitude faster than hand-built ranges, so classes start on time. |

| Live digital-twin hooks |

An API streams sensor/PLC data into the scene; avatars can press buttons that change real machines. |

Technicians rehearse procedures on a fully synchronised virtual line, then walk to the shop floor and see the same HMI screens. |

| AI-assisted immersion |

Cloud AI drives lip-sync, gestures, speech-to-text and 200-language live translation. |

Multilingual crews collaborate naturally; supervisors get instant transcripts for audit and feedback. |

| Zero-install content editing |

3-D models, scripts and training screens can be dragged into the world and are live for all users—no recompilation. |

SMEs tweak layouts during a session and immediately test new fault scenarios or SOP updates. |

| Built-in security & governance |

JWT authentication, tamper-evident VM hashes and snapshot rollback by design. |

Meets ISO 27001 / EASA audit requirements without bolted-on tools. |

5.4. Industrial Uptake and Domain-Specific Applications of the SCSDT Framework

The SCSDT architecture demonstrates strong applicability across multiple industrial verticals by offering a streamlined integration path from design to deployment. MRO & OEMs gain a frictionless pipeline: CAD → VR design review → IoT-synced runtime, eliminating file-conversion overhead. This capability significantly reduces engineering cycle time by allowing stakeholders to visualize, evaluate, and adjust designs directly in a high-fidelity virtual environment that remains synchronised with operational data streams. As a result, design validation, maintenance planning, and operational training can occur in the same immersive context, improving both accuracy and collaboration.

Training providers can sell “metaverse seats” on-demand; the orchestrator spins up GPU instances only when a learner logs in. This elastic provisioning model transforms the economics of high-fidelity VR training, replacing the need for expensive, permanently allocated hardware with just-in-time GPU capacity. The scalability inherent in this model enables rapid expansion of learner cohorts without infrastructure bottlenecks, making advanced industrial training accessible to a broader workforce while optimising operational expenditure.

ICS security teams may prototype digital-twin exploits inside a safe sandbox streamed to thin clients, consistent with NIST SP 1800-10 recommendations for protecting system integrity in industrial control systems [

42]. By reproducing complex industrial control environments in a secure, cloud-hosted VR setting, teams can safely explore vulnerabilities, test mitigations, and train personnel without risking live production systems. The combination of real-time sensor integration and high-fidelity virtualisation ensures that the simulated environment accurately reflects operational conditions, making it a powerful tool for both proactive security hardening and incident response rehearsals.

In sum, SCSDT aligns with pressing industry needs in lifecycle management, scalable workforce training, and cyber-resilience, offering a unified, efficient, and safe pathway for industrial digital transformation [

43,

44].

5.5. Research Roadmap

The findings presented in this work open several promising avenues for future research, aimed at enhancing the scalability, adaptability, and domain transferability of the SCSDT framework.

1. QoE-adaptive encoding – Future iterations should explore migration to AV1-SVC (Scalable Video Coding) to maintain sub-200 kB s⁻¹ throughput on rural or low-bandwidth connections without compromising frame-accurate motion-to-photon latency. This direction is critical to expanding access to high-fidelity training for geographically remote or infrastructure-constrained learners, thus supporting wider industrial adoption.

2. Federated competence analytics – Implementing differential privacy within federated learning pipelines would allow multiple organisations to aggregate competence-trajectory data without revealing individual learner records. This approach not only addresses data governance and compliance requirements (e.g., GDPR, ISO/IEC 27018) but also enables larger-scale meta-analyses of training efficiency across industries, thereby refining the adaptive orchestration algorithms embedded in SCSDT.

3. Cross-domain validation – Replicating the current experimental protocol with medical XR curricula will help determine whether psychomotor-intensive skills follow similar convergence patterns to those observed in industrial maintenance contexts. Such validation could uncover domain-specific constraints or reveal universal learning dynamics, informing both curriculum design and the generalisability of SCSDT across sectors with high safety and precision requirements.

4. Interoperability and Standards Alignment — To support broader adoption and compatibility across platforms, future development of SCSDT will include adherence to emerging open metaverse standards. These include OpenXR for cross-device XR interaction, glTF for real-time 3D asset exchange, and USDZ for augmented reality deployment. By aligning with these open formats, SCSDT can enhance portability, content reusability, and system interoperability, enabling seamless integration with other industrial, educational, or consumer XR ecosystems. This standardization roadmap will be particularly relevant for domain-specific modules, allowing partners and institutions to plug into the SCSDT framework using shared ontologies and assets [

45].

In sum, these research pathways aim to strengthen the technical robustness, ethical compliance, and cross-domain applicability of SCSDT, positioning it as a long-term enabler of sustainable, high-impact immersive training solutions.

6. Conclusions

This work addressed the challenge of delivering high-fidelity industrial training through a secure, scalable, and resource-efficient virtual environment. We presented SCSDT, a cloud-streamed, security-provisioned digital-twin architecture, validated through both an aviation-maintenance learner cohort and an industrial-metaverse pilot.

Technical contribution – The proposed three-layer stack integrates adaptive-GPU streaming, zero-trust provisioning, and AI copilot services over a single HTTPS port, enabling seamless deployment across heterogeneous network and hardware conditions.

Empirical contribution – Experimental results demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in competence-gap norm (η²ₚ = 0.91, d = 11.7), confirmed through paired-samples t-tests and repeated-measures ANOVA. These findings indicate that adaptive orchestration can achieve substantial learning gains within limited training cycles.

Operational contribution – The platform achieved a ten-fold improvement in provisioning speed and an estimated 60 % reduction in per-learner energy consumption compared with local GPU workstations, aligning with ESG objectives and supporting more sustainable training operations.

Although the limitations discussed in Section 4 necessitate larger-scale, multi-site validation, the present evidence positions cloud-first metaverse delivery as a viable, scalable, and environmentally responsible alternative for high-stakes industrial training. All analysis scripts and the SVG architecture diagram are openly archived, ensuring full transparency, reproducibility, and benchmarking opportunities for the research community.

Future work will focus on extending SCSDT’s applicability to other safety-critical domains, enhancing adaptive orchestration algorithms, and contributing to the development of open interoperability standards for immersive, cloud-based industrial training environments.

Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| AV1 |

AOMedia Video 1 (video compression format) |

| CPU |

Central Processing Unit |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| CLI |

Command-Line Interface |

| CSV |

Comma-Separated Values |

| DT |

Digital Twin |

| DTBT |

Digital Twin-Based Training |

| EMP |

Evidence-based Metaverse Pedagogy |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| HMD |

Head-Mounted Display |

| HTTP |

Hypertext Transfer Protocol |

| IIoT |

Industrial Internet of Things |

| L1 / L2 / L3 |

Layer 1 / Layer 2 / Layer 3 (SCSDT Architecture) |

| MaaS |

Metaverse-as-a-Service |

| OPC-UA |

Open Platform Communications – Unified Architecture |

| QoE |

Quality of Experience |

| REST |

Representational State Transfer |

| SCSDT |

Secure Cloud-Streaming Digital Twin |

| SSO |

Single Sign-On |

| t-test |

Student’s t-distribution test |

| UDP |

User Datagram Protocol |

| USDZ |

Universal Scene Description Zip (3D file format by Apple) |

| VNC |

Virtual Network Computing |

| VR/AR |

Virtual Reality / Augmented Reality |

| xAPI |

Experience API (e-learning tracking standard) |

| YAML |

Yet Another Markup Language |

References

- Bivolaru, M.M. Optimizing Trajectories in 3D Space Using Mixed Integer Linear Programming. U.P.B. Sci. Bull, Series D 2024, 86, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jerald, J. The VR Book Human-Centered Design for Virtual Reality, ACM Books, New York, U.S.A., 2015. pp. 1-523.

- Josifovska, K.; Yigitbas, E.; Engels, G. Reference Framework for Digital Twins within Cyber-Physical Systems, In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Software Engineering for Smart Cyber-Physical Systems (SEsCPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, (28 May 2019).

- Payne, A.; Kent, S.; Carable, O. Development And Evaluation Of A Virtual Laboratory: A Simulation To Assist Problem-Based Learning.. In Proceedings of the MCCSIS'08 - IADIS Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems; Proceedings of e-Learning, Netherlands, (22-25 July 2008).

- Zhai, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Internet of Things Access Control Identity Authentication Method Based on Blockchain. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Series C 2025, 87, 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Deac, G.; Georgescu, C.; Popa, C.; Ghinea, M.; Cotet, C.E. Virtual Reality Exhibition Platform, In Proceedings of the 29th DAAAM International Symposium, Zadar, Croatia, (24-27 October 2018).

- Rahman, M.; Mahbuba, T.; Siddiqui, A. Cloud-Nativ Data Architectures for Machine Learning (Sabila Nowshin Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh), Personal Communication, 2019.

- Salah, K.; Hammoud, M.; Zeadally, S. Teaching Cybersecurity Using the Cloud. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 2015, 8, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deac, G.C.; Deac, T. Multi-Layer Metaverse Architectures. Journal of Digital Learning Environments 2024, 3, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; Hamidouche, W.; Chavarrías, M.; Pescador, F.; Farhat, I. Performance analysis of optimized versatile video coding software decoders on embedded platforms. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 2023, 20, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Russo, E.; Armando, A. Automating the Generation of Cyber Range Virtual Scenarios with VSDL. Journal of Wireless Mobile Networks, Ubiquitous Computing, and Dependable Applications 2022, 13, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillemets, P.; Bashir Jawad, N.; Kashi, J.; Sabah, A.; Dragoni, N. A Systematic Review of Cyber Range Taxonomies: Trends, Gaps, and a Proposed Taxonomy. Future Internet 2025, 17, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.; Ford, J.; Saniie, J. Architecture of an Efficient Environment Management Platform for Experiential Cybersecurity Education. Information 2025, 16, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I. Digital-Twin-Based Ecosystem for Aviation Maintenance Training. Information 2025, 16, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research, 4th ed., SAGE Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks, California, U.S.A. 2015, pp. 1-431.

- Massey, A.; Montoya, M.; Binny, S.; Windeler, J. Presence and Team Performance in Synchronous Collaborative Virtual Environments. Small Group Research 2024, 55, 290–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Dijiang, H.; Tsai, W.T. Cloud-Based Virtual Laboratory for Network Security Education. IEEE Transactions on Education 2014, 57, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]