1. Introduction

Immunity represents a significant attribute of the human and animal bodies as well as of the plant reign, being responsible for protecting against toxic, viral, microbial, tumoral and fungal agents. The way how the immune system behaves in regard to its structures (self) and foreign structures or antigens (non-self) is described by immunology. In a permanent dynamic, the cells of the immune system are responsible for homeostasis, while the post-vaccination effects are driven by its integrity [

1].

This study aims to emphasise the link between a trained competent immune system and its response among vaccinated children and how vaccination offers an advantage in this regard.

1.1. Innate Immunity

Innate immunity represents the first response against any foreign agent that enters the body [

1]. It is composed by anatomical barriers, the skin and the mucosal membranes as well as specialised cells: polymorphonuclear cells, granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells and lymphoid cells. Antimicrobial peptides, cytokines, serum proteins and cellular receptors are also part of innate immunity [

2].

1.2. Adaptive Immunity

In contrast with innate immunity, the adaptive immunity has high specificity. T and B lymphocytes form the adaptive immunity, present long-lasting immune memory and antigen recognition receptors that develop high specialised functions are found on their surface. Both T and B lymphocytes are derived from bone marrow precursors [

3].

1.3. Vaccination vs Immunization

Immunization derives from Greek meaning "protected". Acquired immunity derives from different antigens exposure or exogenous antibodies. Vaccination represents the inoculation of an antigen that will induce immunity to the host organism lately [

4].

There are 2 types of immunization, active or passive. Active immunisation is represented by generating specific antibodies after antigen exposure, the immune system actively being involved in antibody production to protect the individual from another exposure to the same microorganism. Passive immunisation does not actively involve the immune system as antibodies (polyclonal human derived antibodies - convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin, animal derived antibodies or antigen specific monoclonal antibodies) are administered [

4].

Vaccination is defined by the inoculation of a pathogen antigen to a receptor organism, followed by a response, except the onset of disease [

4].

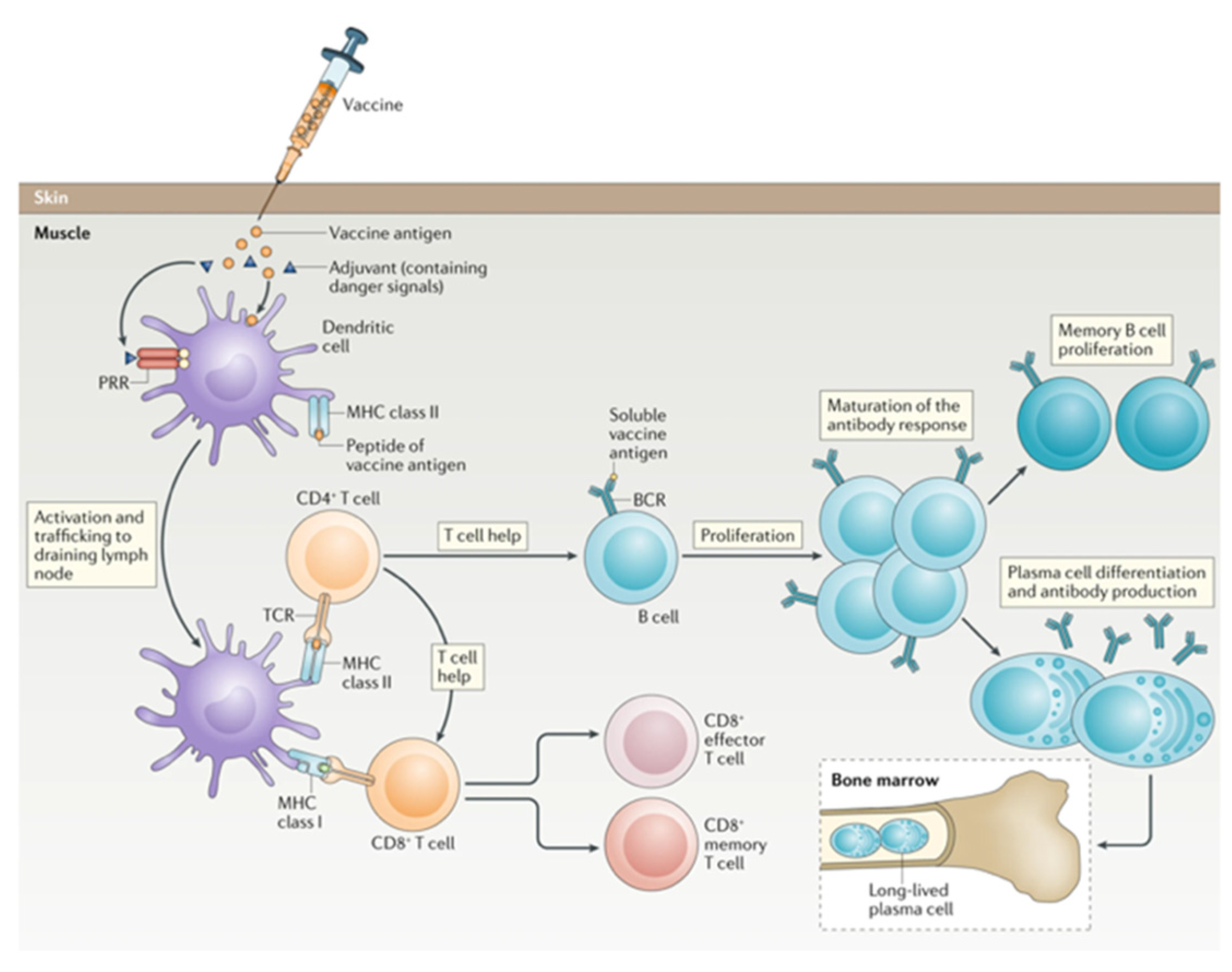

As described in

Figure 1, after administering a vaccine, by inoculating a protein antigen, dendritic cells are responsible for processing it after being activated by pattern recognition models. Antigen presentation by major histocompatibility complex activates T cells (T cell receptors binding). Simultaneously, the soluble antigen signals B cell receptors. Within lymphatic nodule T cells develop B cells differentiation. Dependent B cells lead to antibody response maturation to increase different antibody isotypes. Short life plasmatic cells actively secrete vaccine protein specific antibodies leading to a significant increase of antibodies in the nest 14 days. Memory B-cells mediate immune memory and are viable for a long period of time, being located in the bone marrow. CD8+ T memory cells proliferate when meeting a pathogen agent while CD8+ T effector cells eliminate infected cells [

5].

1.4. Primary Immunodeficiency and Autoimmunity

Primary immunodeficiency conditions include genetic diseases that influence innate and acquired immune response. Patients suffering from these conditions are more susceptible to transmittable and non-transmittable diseases as well as more prone to develop allergies, malignant tumours and autoimmune disorders. Primary immunodeficiencies can be classified as monogenic or polygenic. In monogenic immunodeficiencies mutations occur in genes involved in immune tolerance, increasing predisposition to develop autoimmunity, while polygenic disorders are defined by clinic heterogeneity. Mutations of autoimmune regulator protein (AIRE) within T cells plays a key role in the development of autoimmune disorders. Improper Treg/Th17 ratio facilitates autoimmunity by inducing a pro-inflammatory state, while molecular mimicry induces chronic and recurrent infections [

6].

1.5. Vaccination in Patients with Primary & Secondary Immunodeficiency and Autoimmune Diseases

Vaccination represents a robust shield against pathogens in individuals suffering from these diseases in spite of the fact that vaccine response in these cases is lower. However, vaccination plays an important role in reducing hospitalisations, healthcare costs, infectious diseases and hospital mortality [

7].

Live vaccines in patients with severe primary & secondary immunodeficiency represent an absolute contraindication. Inactivated corpuscular vaccines are the elective choices in this group of patients. Vaccines against polio-virus, measles, mumps, rubeola, convulsive cough, A&B hepatitis, Hemophilus influenzae B, HPV, meningococcal and pneumococcal vaccines protect these patients against severe complications while reducing mortality and morbidity, especially in paediatric patients [

7].

2. Aim of the Study

Strengthening immune response by vaccine administration is crucial in infections. That is why this study aims to highlight the link between a trained mature competent immune system and its capacity to respond in exceptional situations to protect the host against different pathogens. Another aim of this study is to analyse the actual situation of children immunisation in Romania in accordance with the Romanian national immunisation scheme mothers' level of trust in vaccines as primary disease prevention. Our study objectives were: to evaluate vaccination immune response in the case of infection with the targeted pathogen; lactation role (at least 6 months) according to WHO recommendations in new-borns immunity maturation; to compare the immunity between premature and on term new-borns; analyse mothers' vaccine trust and hesitancy; vaccination advantages, the ability to obtain a robust immunity response in individuals during COVID-19 state of alert in Romania.

3. Materials and Methods

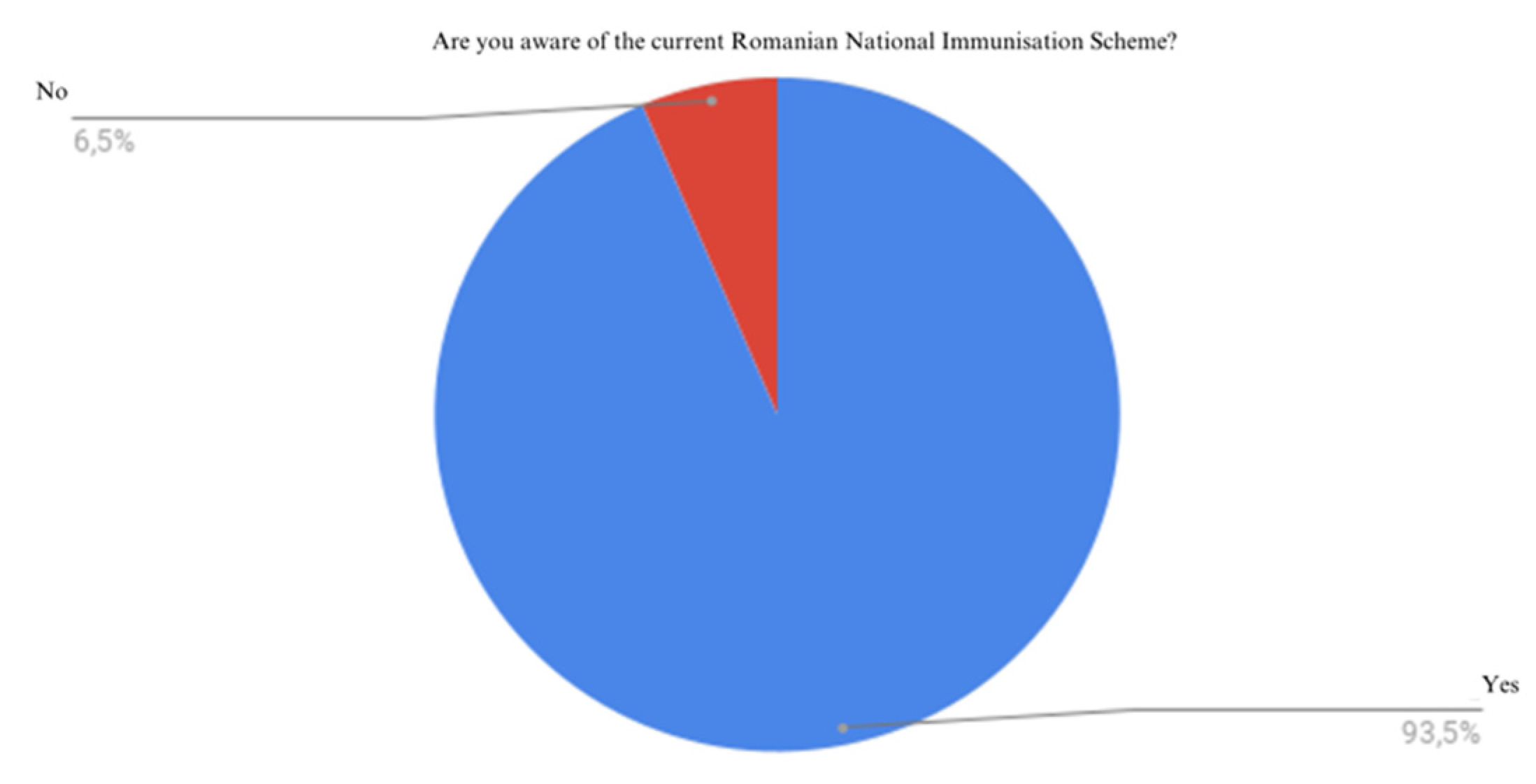

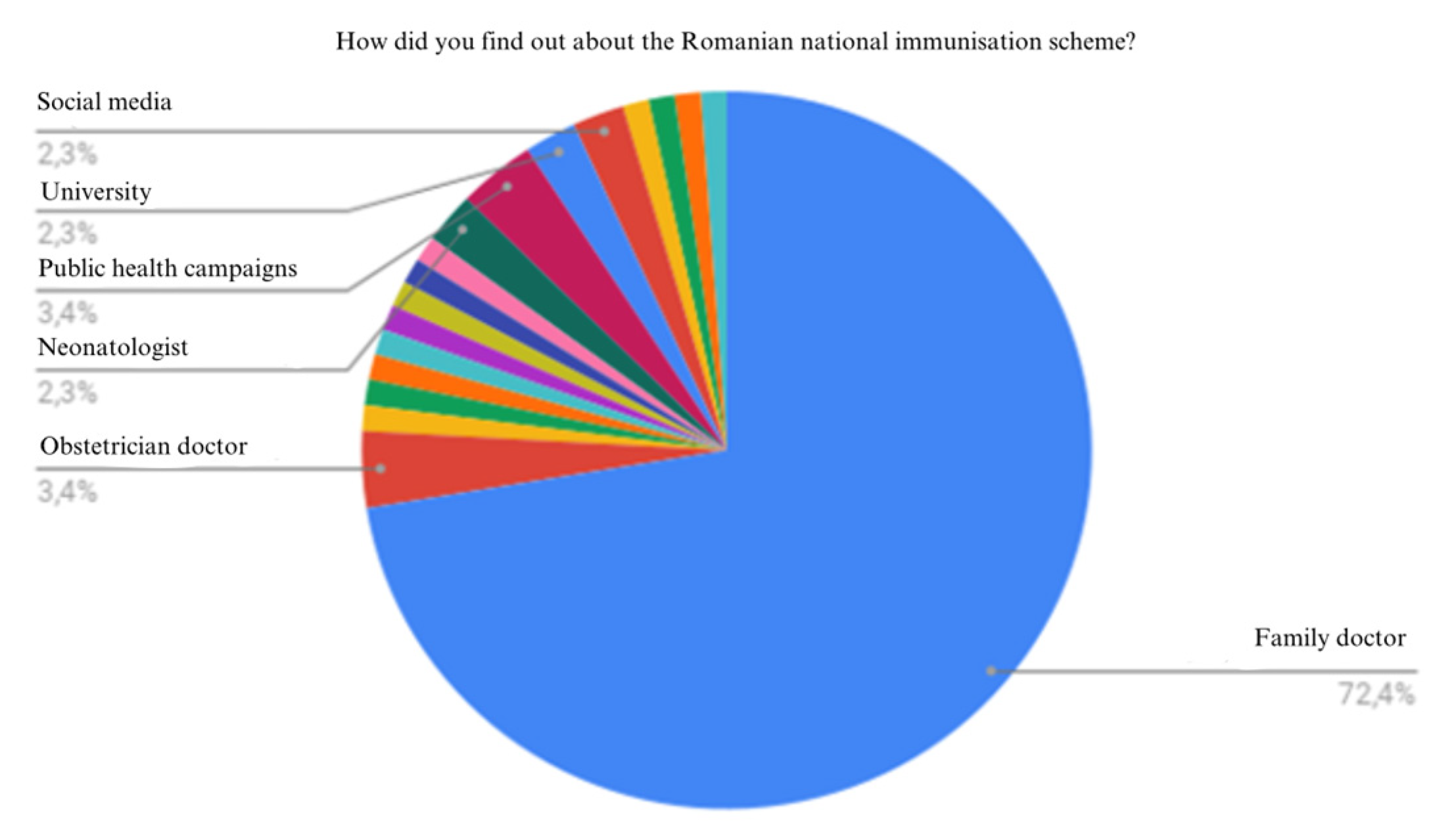

This paper includes a retrospective and prospective study comprehending 23 questions addressed to mothers that had at least 1 birth. The questions were single or multiple choice to facilitate questionnaire completion. There were 93 respondents representing 142 children. The first 2 questions evaluated (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) the level of knowledge regarding the Romanian national immunisation scheme and how they got information on this matter, followed by demographic questions about mothers' age and living area.

The first part of the questionnaire extracted information about pre-natal, intra-natal and post-natal periods, while the second part selected information about their children, representing our area of focus. Our study spotlighted the protective vaccination effect over potential side effects.

Furthermore, mothers were asked regarding vaccination role in their children' health, their decision to vaccinate their children and if they had any recommendations for other mothers about Romanian national vaccination scheme.

4. Results

4.1. Romanian National Immunisation Scheme

The first question of the questionnaire was "Are you aware of the current Romanian National Immunisation Scheme?". As

Figure 2 illustrates, the majority of answers were affirmative.

Figure 3 highlights the key role of family doctors not only in treating conditions and patient surveillance, but also in educating population regarding primary disease prevention which should be provided to children.

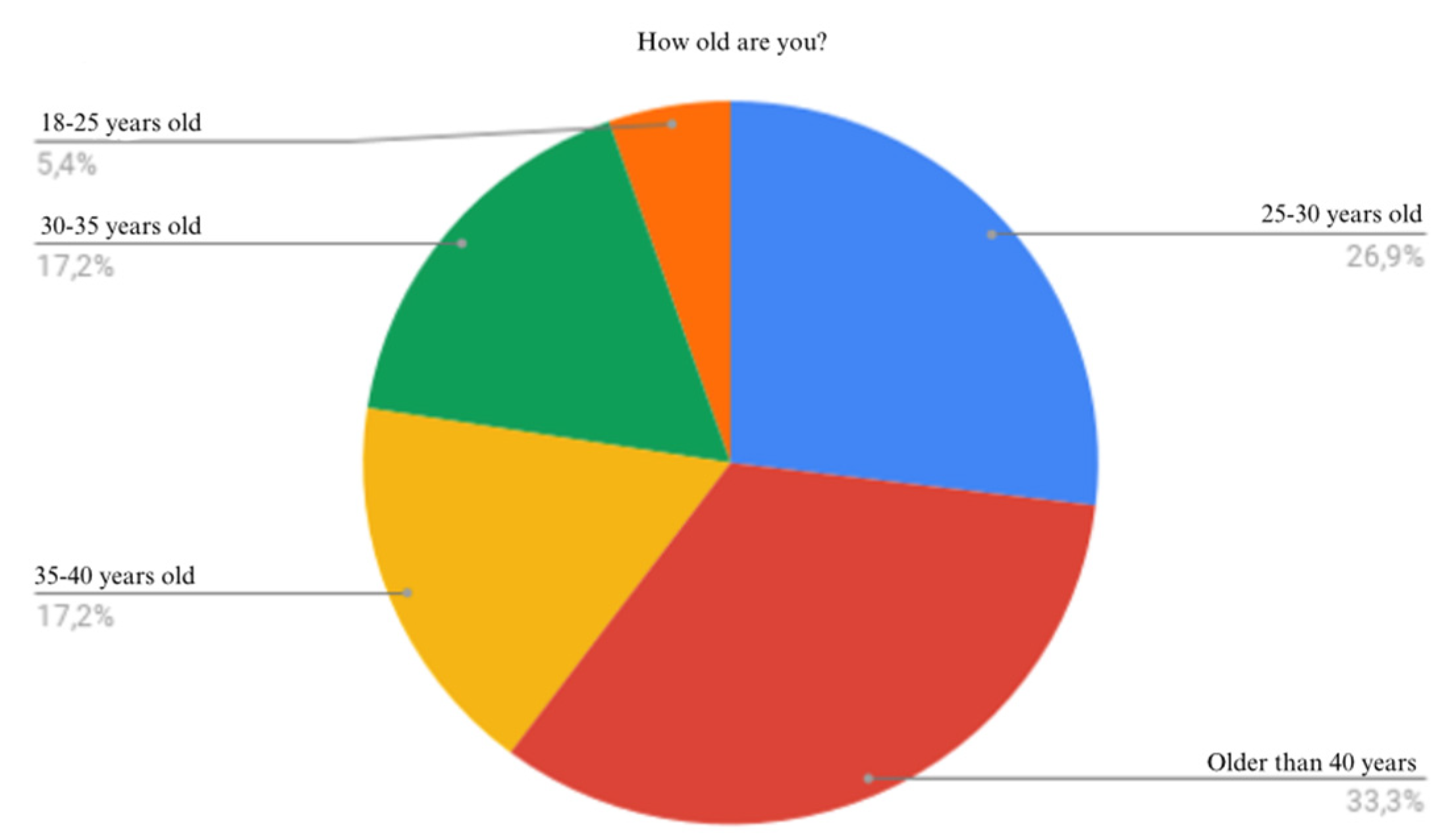

4.2. Demographic Data

Figure 4 shows that third of the mothers were aged older than 40, while the smallest proportion of age was younger than 25.

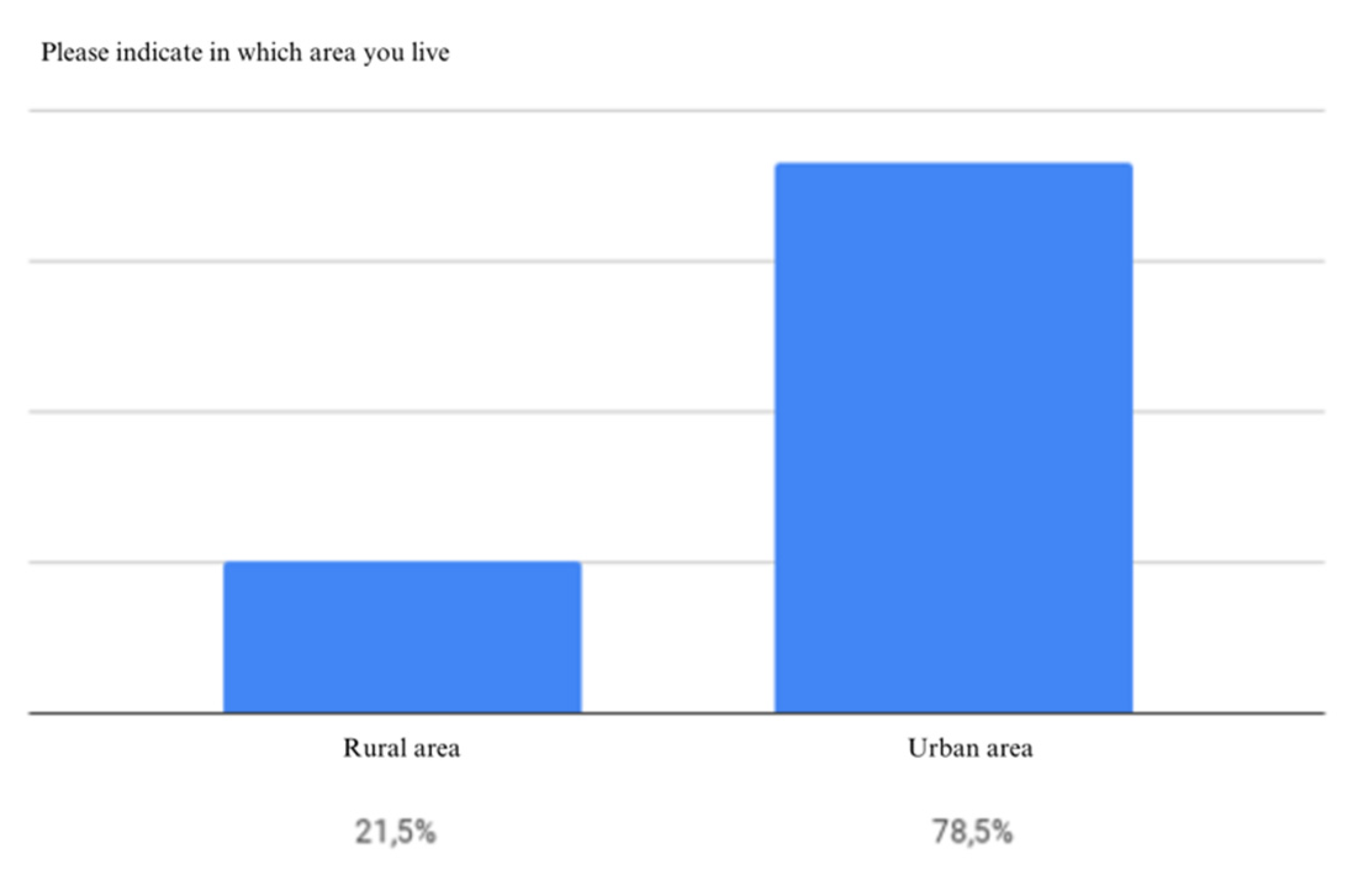

4.2.1. Living Area

As

Figure 5 shows, 73 respondents (78.5%) lived in urban area while 20 subjects (21.5%) lived in rural area.

4.3. Mothers Profile

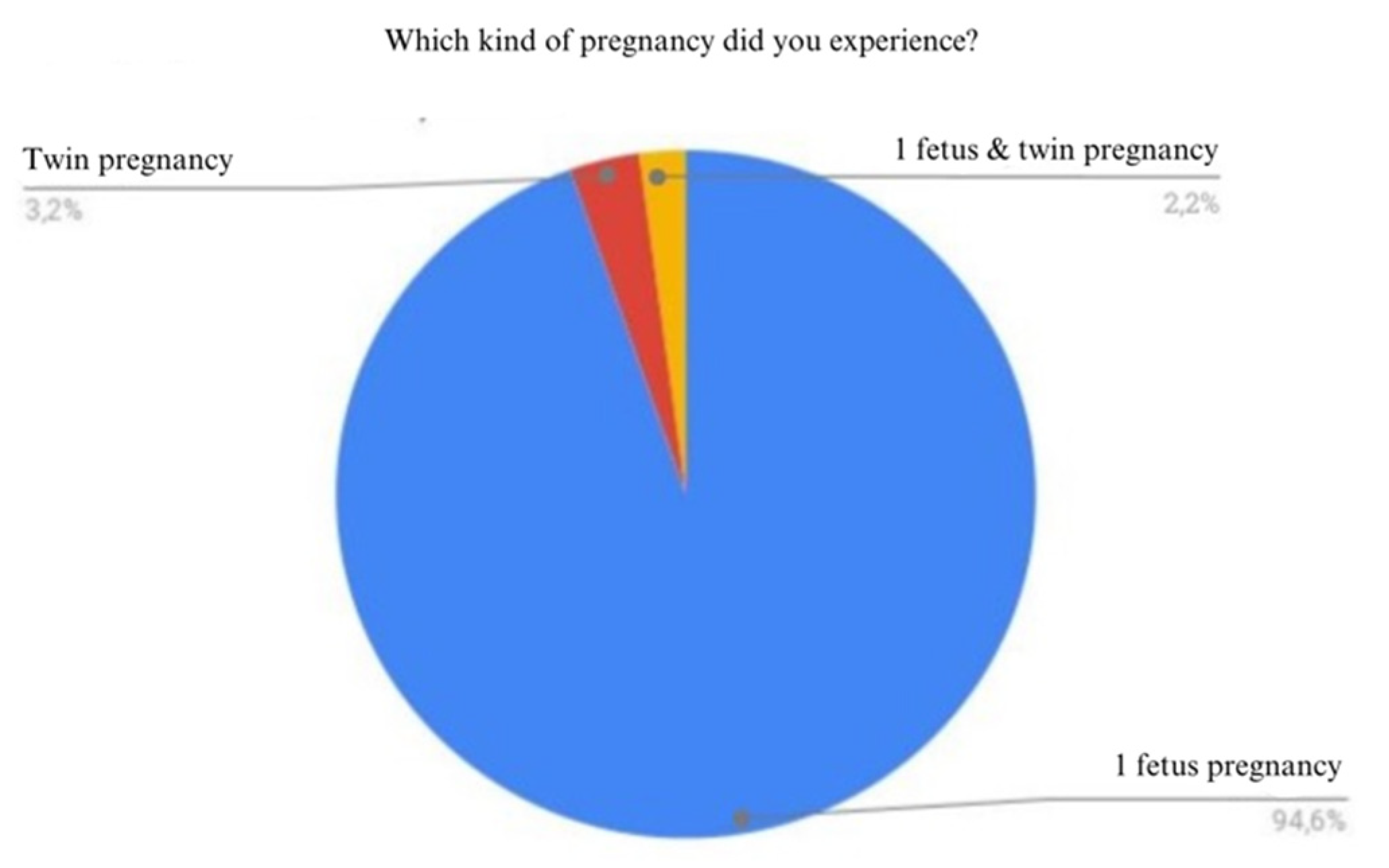

4.3.1. Pregnancy

88 women (94,6%) experienced 1 fetus pregnancy, 2 women (2,2%) had both 1 fetus pregnancy and twin pregnancy and 3 women (3,2%) experienced only twin pregnancies as

Figure 6 indicates.

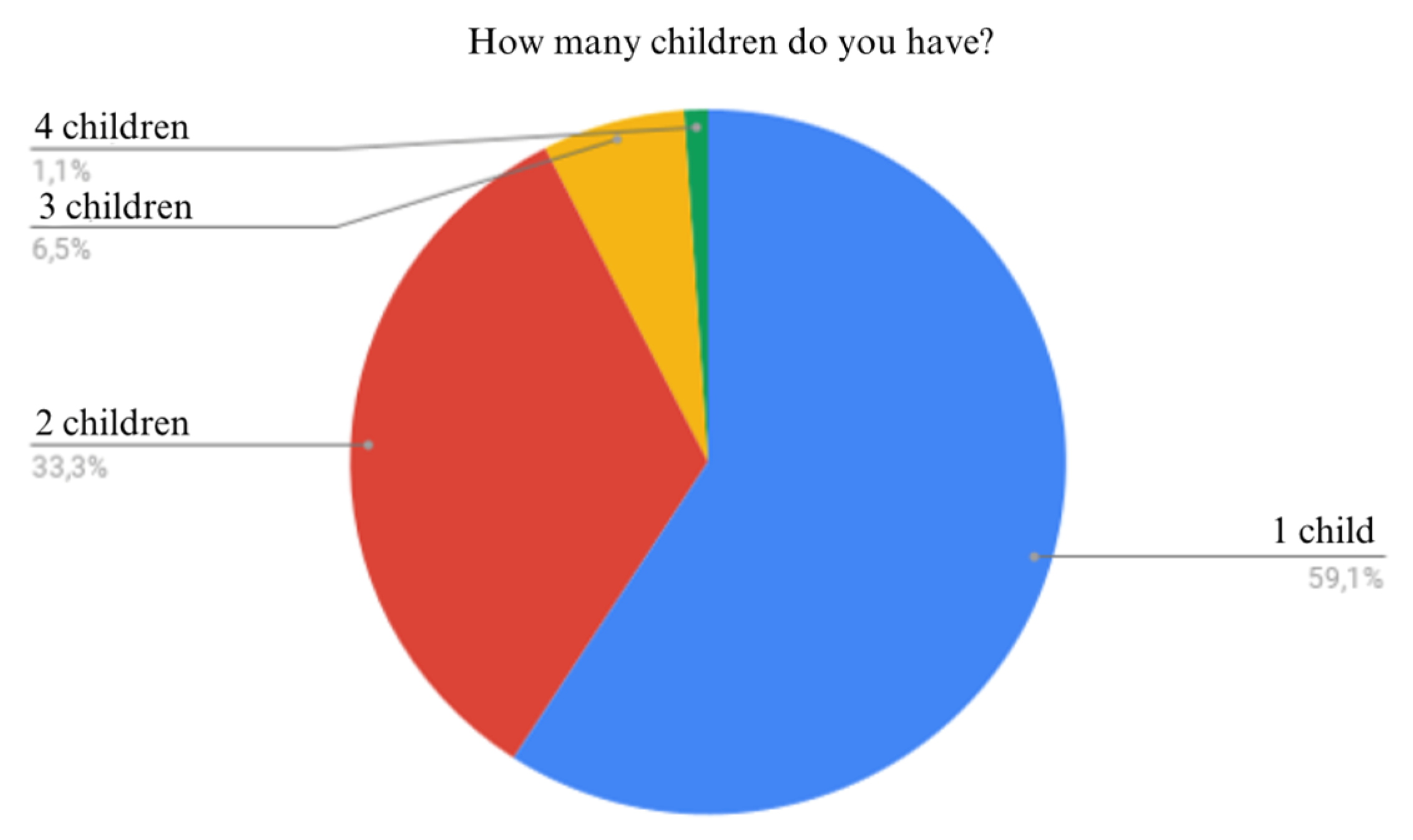

4.3.2. Number of Children

Figure 7 shows that more than 50% of mothers had 1 child, while a third (33.3%) had 2 children. A 6.5 percentage indicates the answer of 3 children, while the rest of 1.1% had more than 4 children

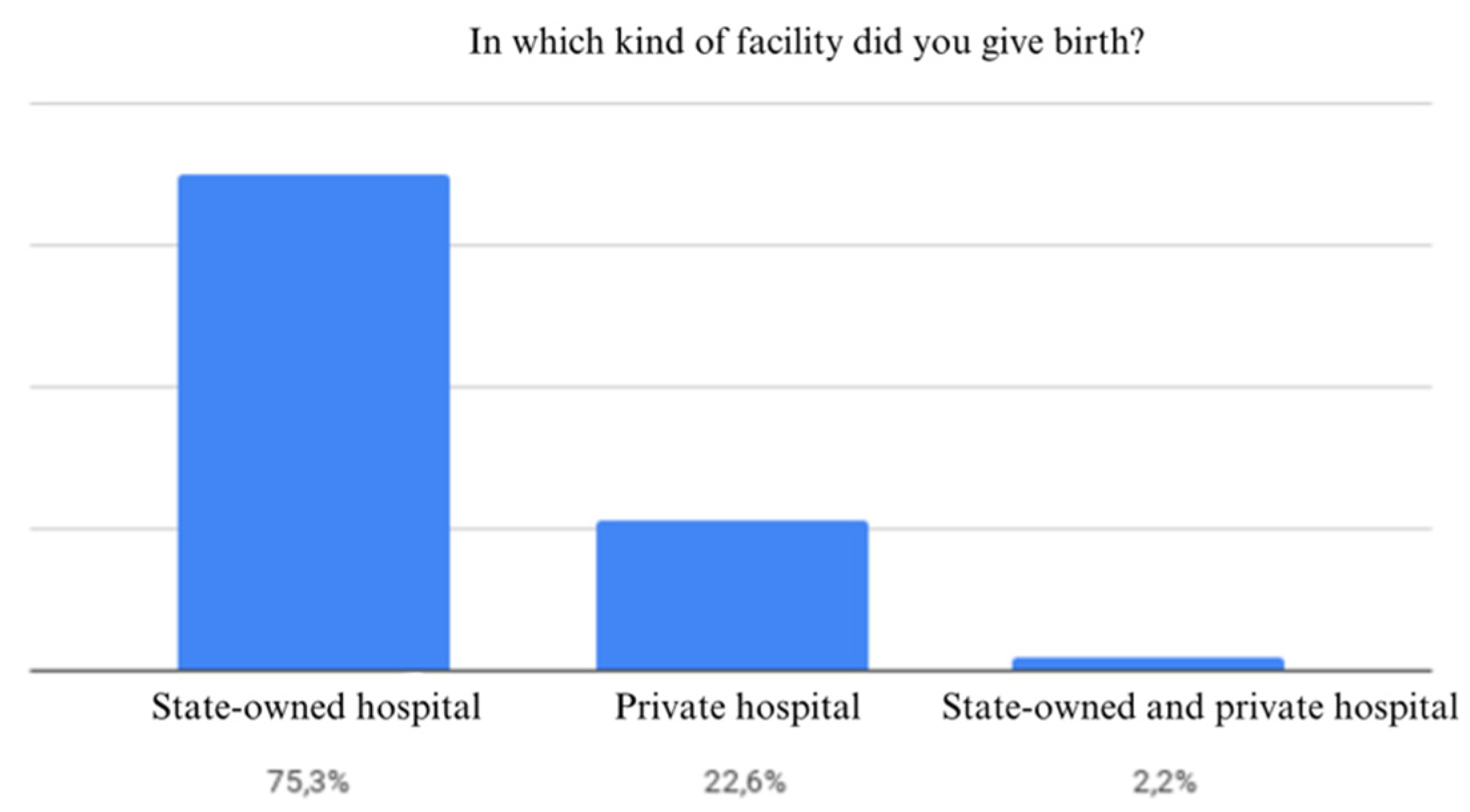

4.3.3. Place of Birth

As

Figure 8 indicates most births occurred in state-owned hospitals, meaning 70 answers (75.3%). 21 (22,6%) answered "private hospital", while 2 births (2,2%) occurred in both private and state-owned hospitals.

4.3.4. Type of Birth

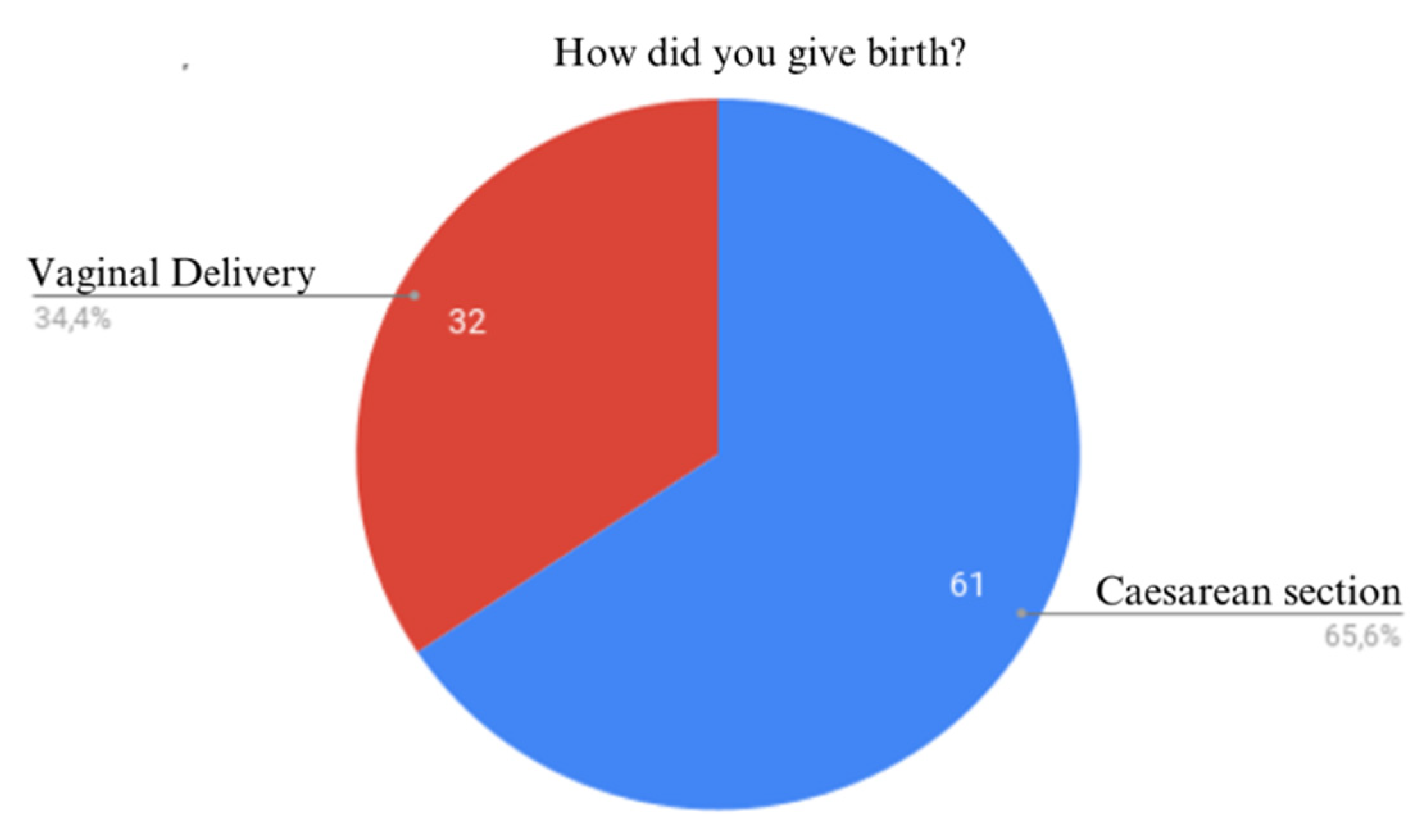

Figure 9 indicates that more than half of the respondents (61 mothers), 65.6% delivered by caesarean section while only 32 mothers (34.4%) delivered vaginally.

4.4. Children Profile

4.4.1. Gestational Age

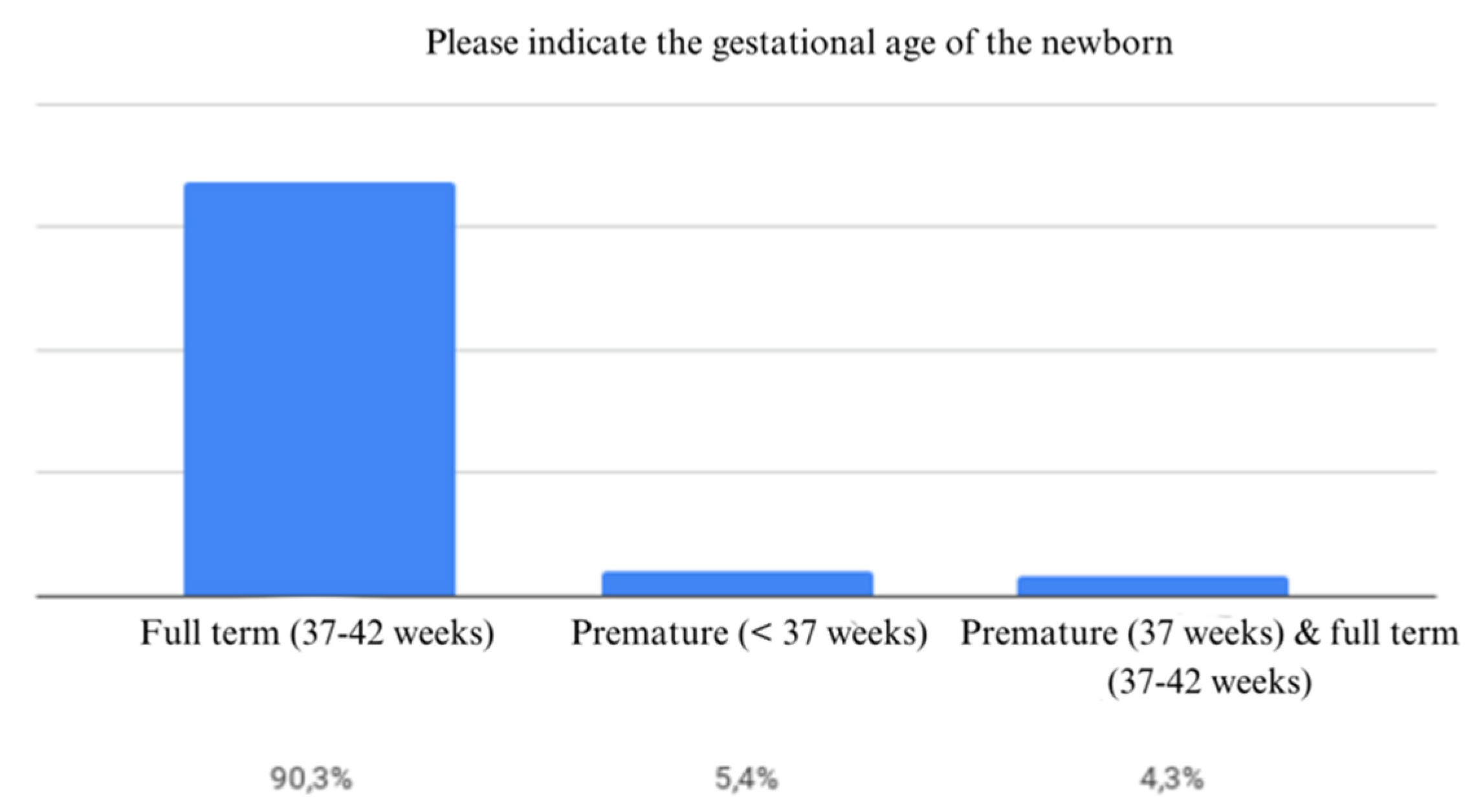

As

Figure 10 illustrates, most pregnancies recorded by our survey were full term (84 mothers, 90.3%) while 5.4% of mothers delivered premature newborns and 4 mothers (4.3%) delivered both premature and full-term newborns.

4.4.2. Nutrition

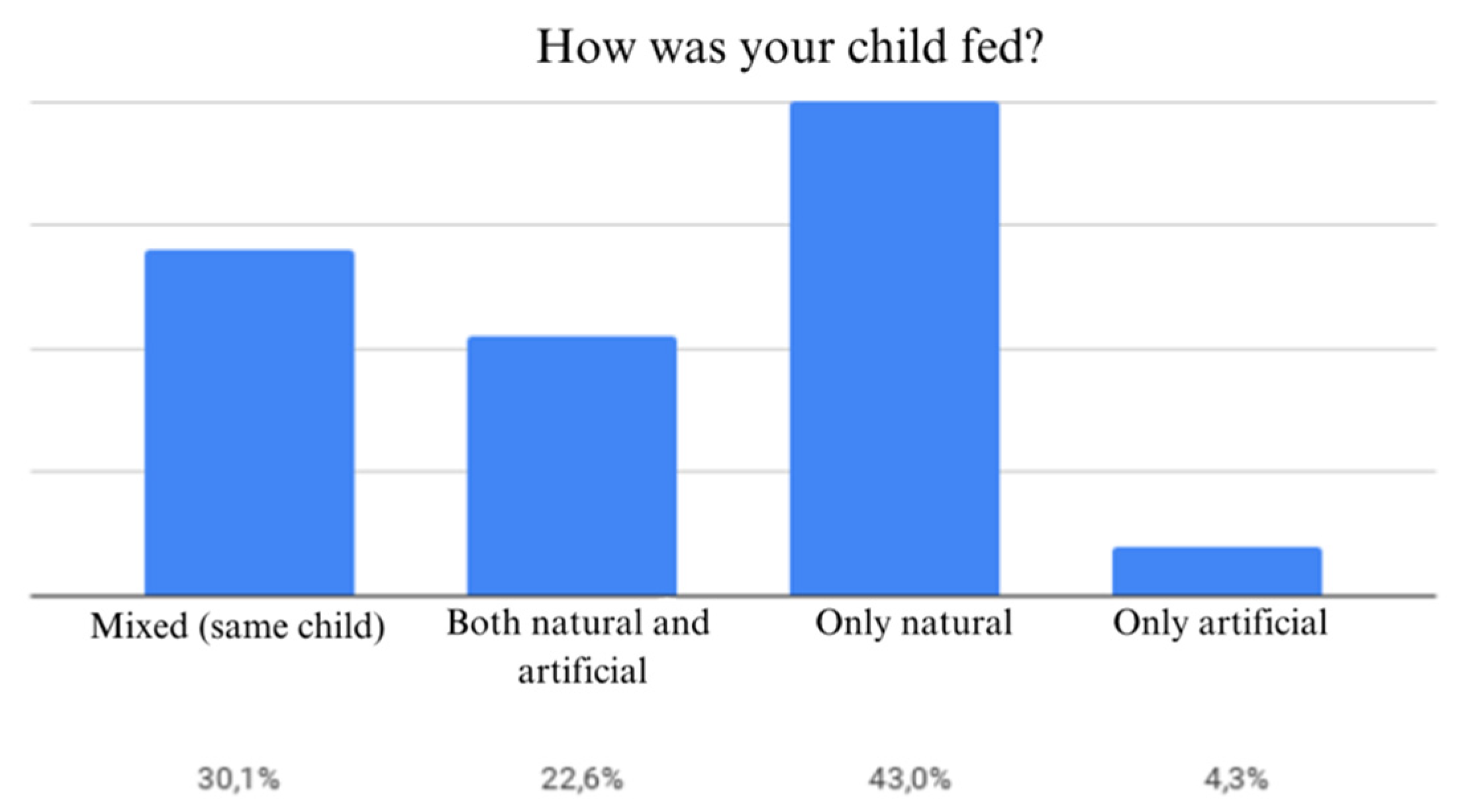

As

Figure 11 indicates about half of the answers (40), a percentage of 43 were affirmative for natural feeding, while on the second place being mixed feeding of the same newborn with 28 answers, a percentage of 30.1%, followed by artificial feeding (4 answers, 4.3%). 22.6% of the answers indicated that both artificial and natural nutrition was given to different children of the same mother.

4.4.3. Lactation Period

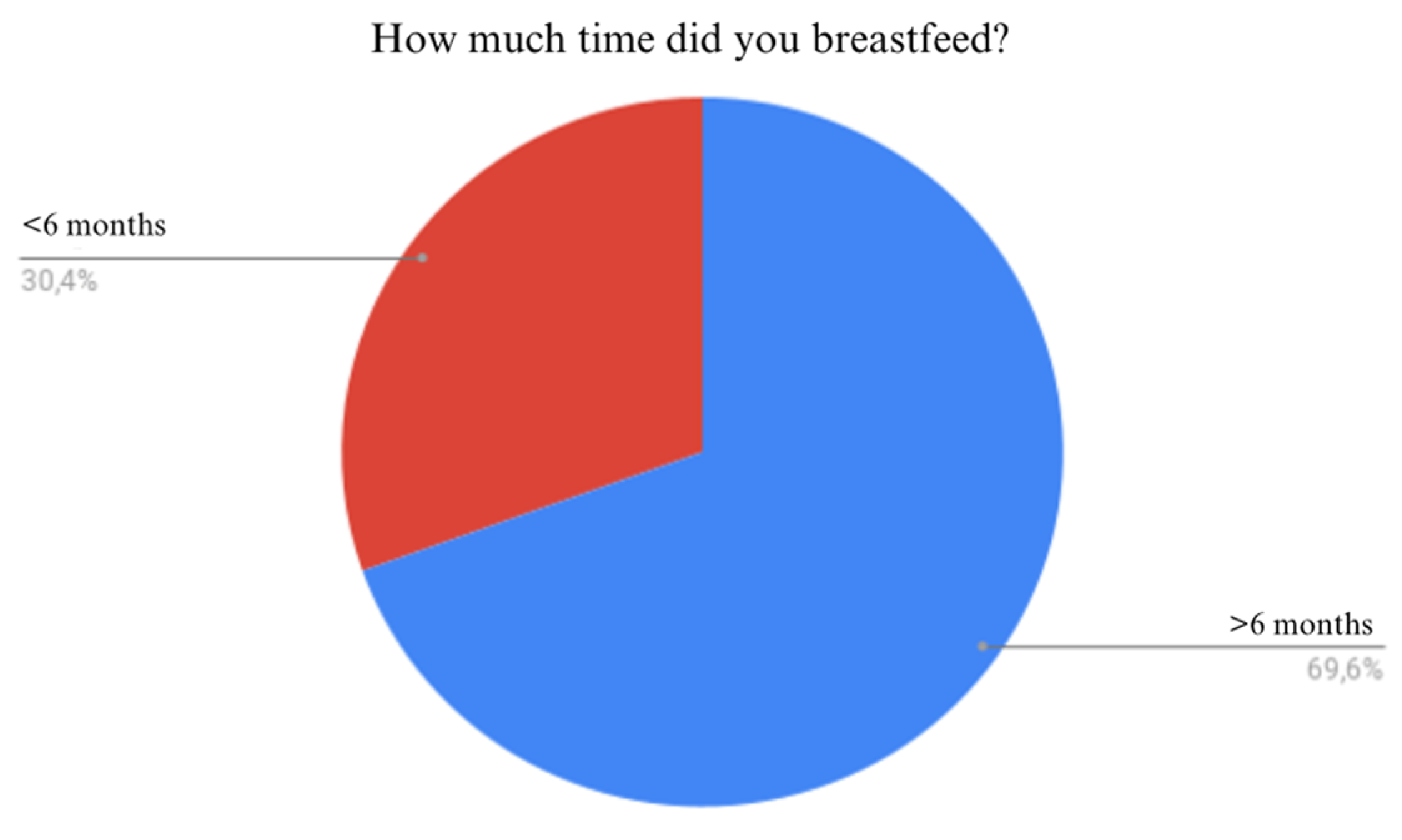

Figure 12 shows that 69.6% of the lactation periods lasted over 6 months, while 30.4% lasted less than 6 months.

4.5. Vaccine Administration

4.5.1. Hepatitis B Vaccination at Birth

90 (96.8%) mothers vaccinated their children against hepatitis B while 2 mothers refused the vaccine (2.2%). 1 mother answered not vaccinating all of her children against hepatitis B (1%).

Figure 13 illustrates the vaccination status against hepatitis B of the children included in our study.

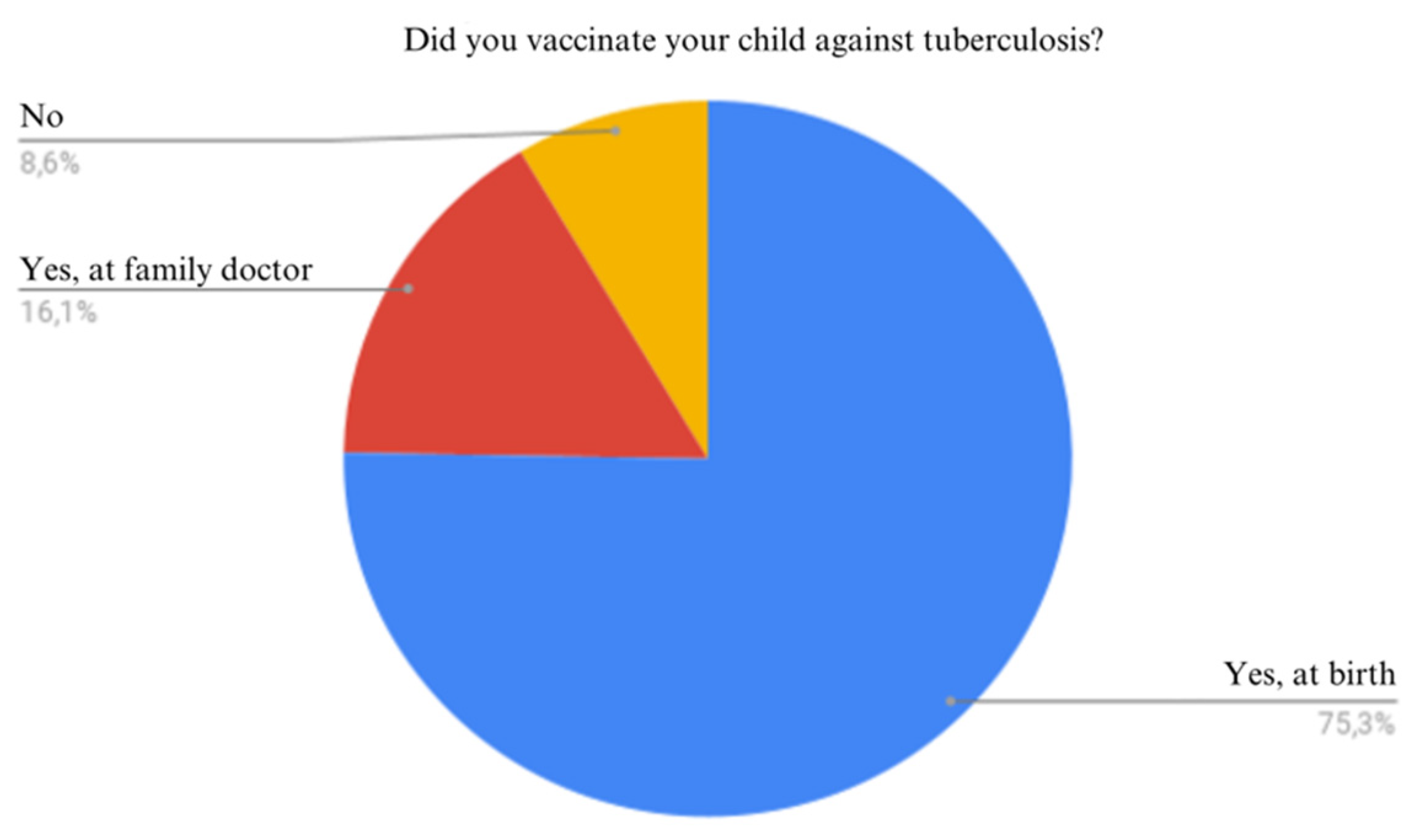

4.5.2. Tuberculosis/BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guerrin) Vaccination

8 answers were negative about new-born vaccination, while 85 answers were affirmative. 75% new-borns received the vaccine on birth, 16.1% were vaccinated at family doctor and 8.6% did not receive the vaccine according to

Figure 14.

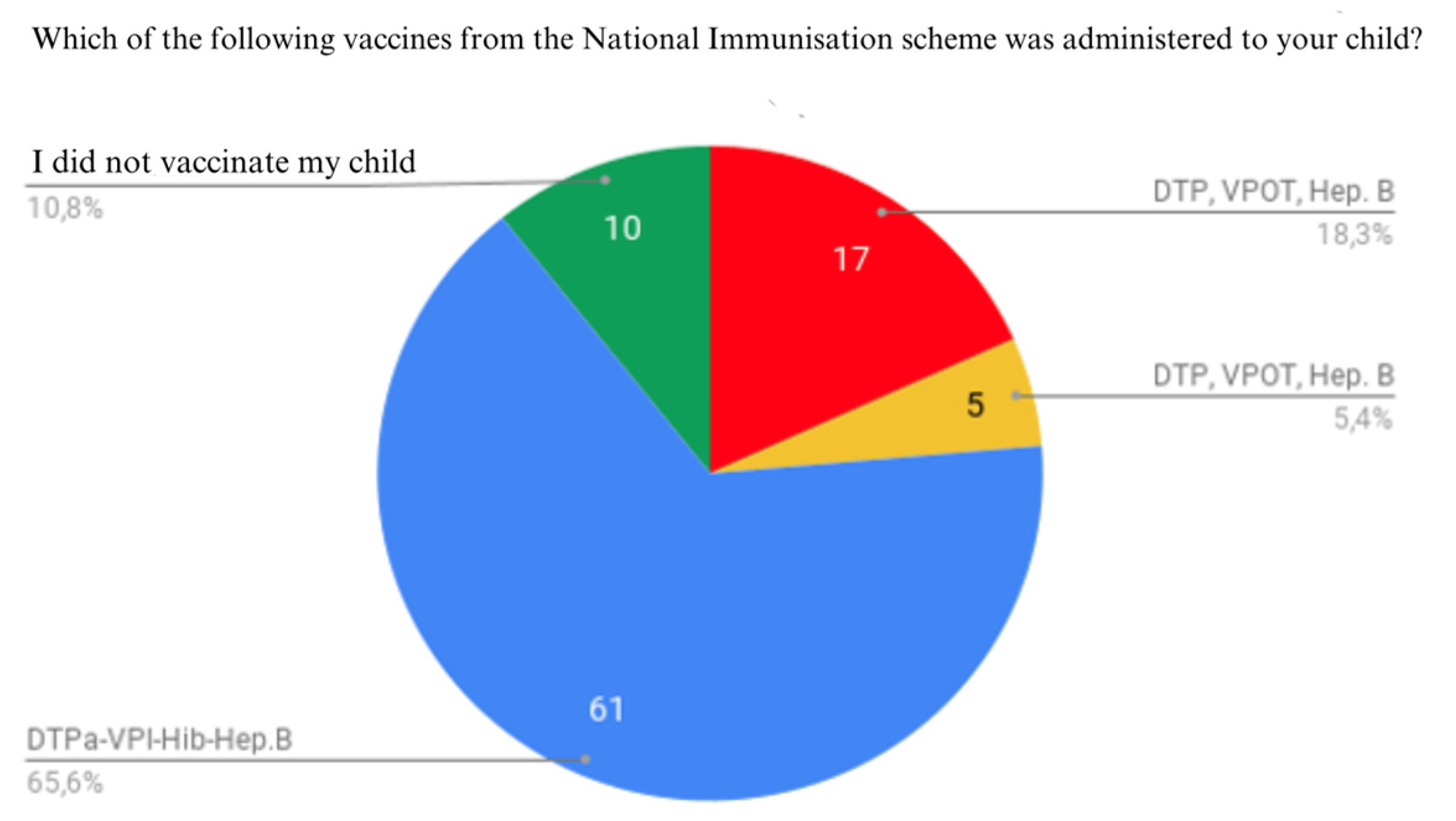

4.5.3. Administration of DTa-VPI-Hib-HepB and DTP-VPOT-HepB Vaccines

Figure 15 shows that out of all 93 questionnaire answers, 83 were affirmative regarding this kind of vaccination (82.2%). However, 10.8% of the respondents, 10 mothers refused to vaccinate their children.

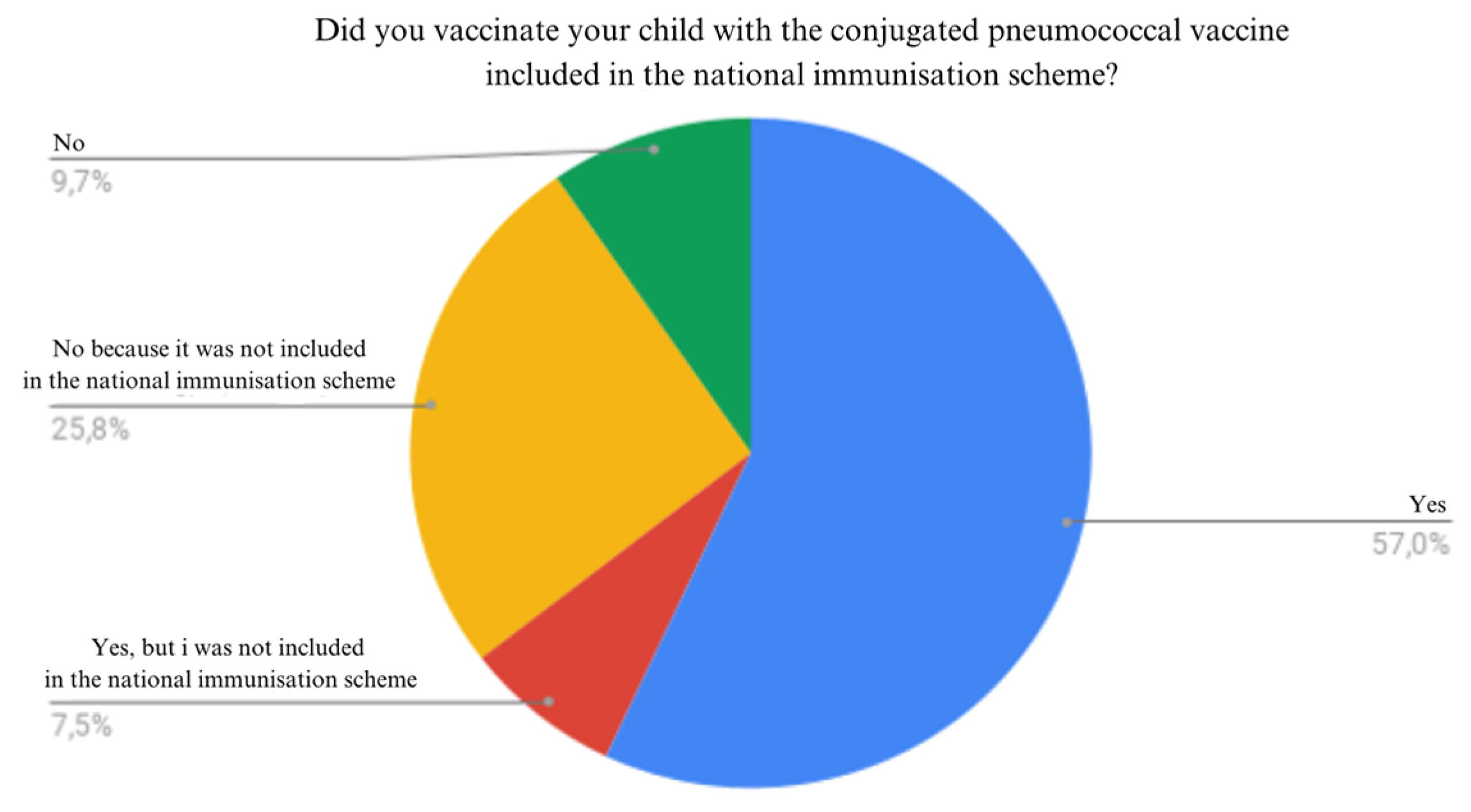

4.5.4. Administration of Pneumococcal Vaccine

Figure 16 shows that more than half of the answers, 57% of children received pneumococcal vaccination, while the smallest percentage is allocated to children that were not vaccinated against pneumococcal infection, 9.7%. However, 25.8% of the respondents indicated that this vaccine was not included in the Romanian national immunisation scheme, this being the reason they did not vaccinate their child. 7.5% of mothers vaccinated their children with pneumococcal vaccine, even if the vaccine was not included at that time in the national immunisation scheme.

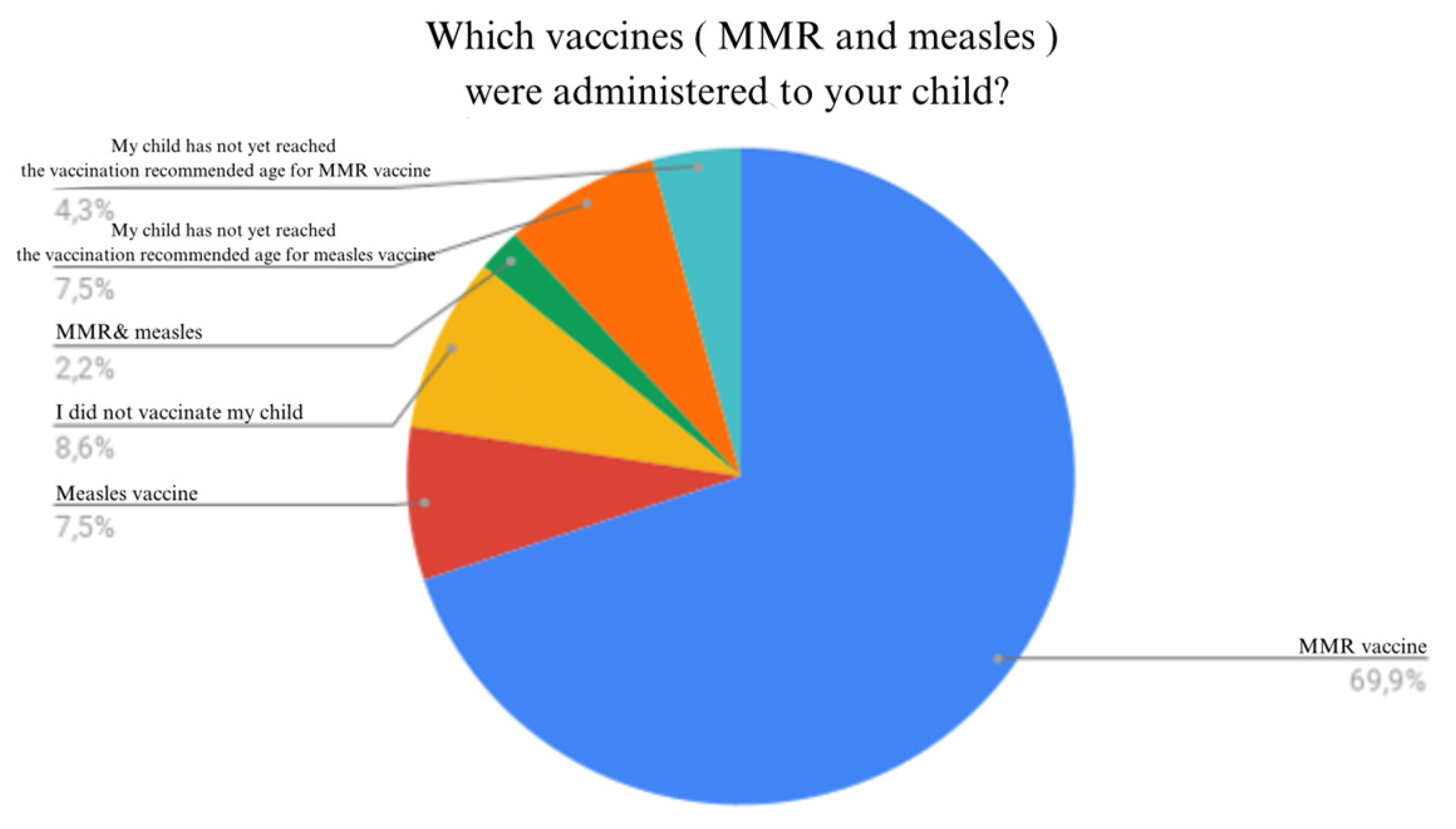

4.5.5. Administration of MMR (Mumps, Measles, Rubella) and Measles Vaccines

According to

Figure 17, a significant percentage, 69.9% (65 answers) was attributed to MMR vaccination. 7.5% of mothers (7 answers) administered only the measles vaccine, while 2.2% (2 answers) administered both MMR and measles vaccines. 8.6% did not vaccinate their children, while 4.3% of mothers did not yet vaccinate their children against MMR, waiting for the proper vaccination age, the same case for another 7.5% who waited for measles vaccination.

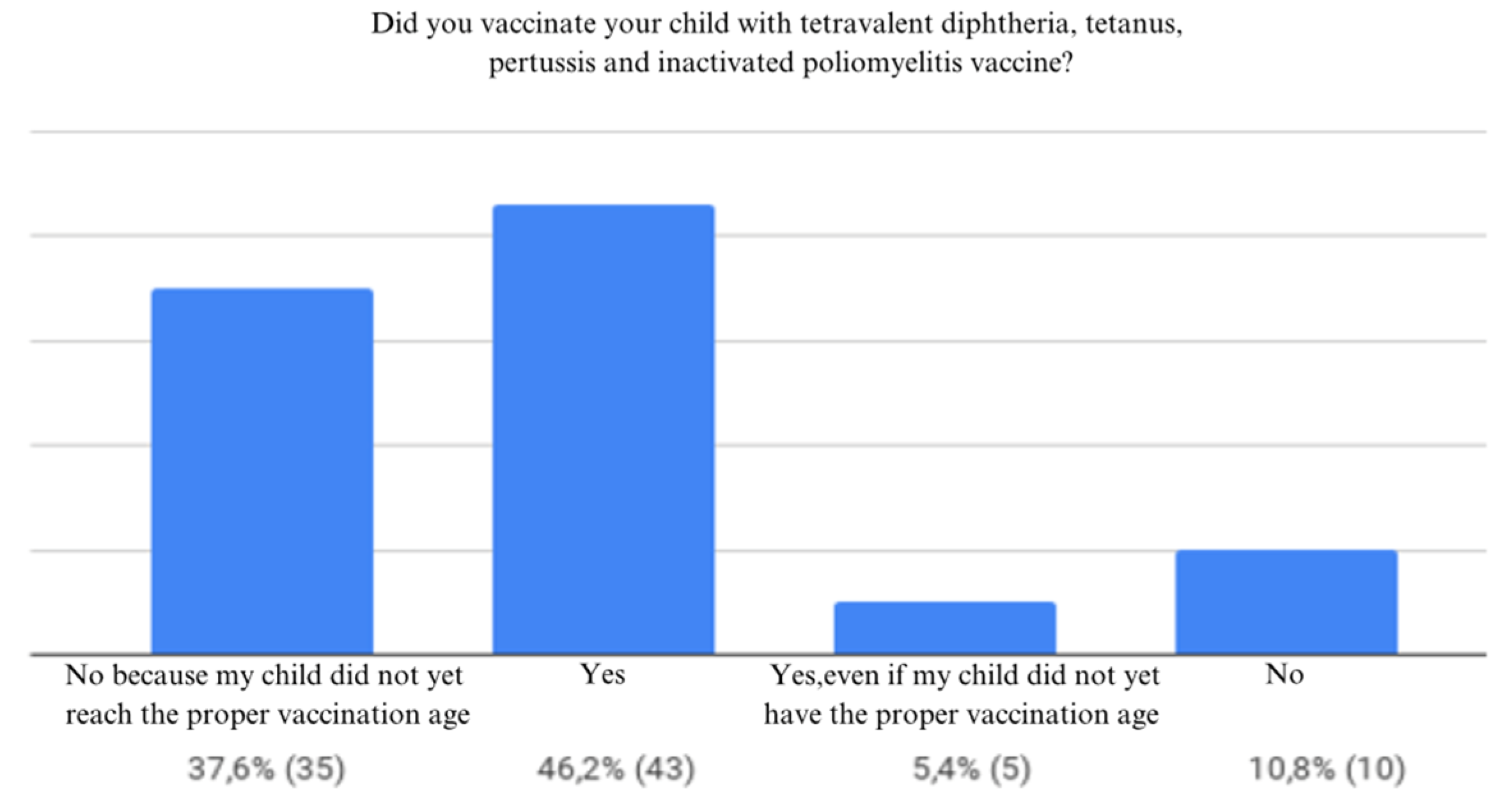

4.5.6. Administration of Tetravalent Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis and Inactivated Poliomyelitis Vaccine

Figure 18 shows that 43 answers (46.2%) confirmed vaccination with the tetravalent vaccine, while 10 mothers (10.8%) refused vaccination. 5.4% of children received the first dose of vaccine without having the proper vaccination age, while 37.6% of children were not yet vaccinated due to their age.

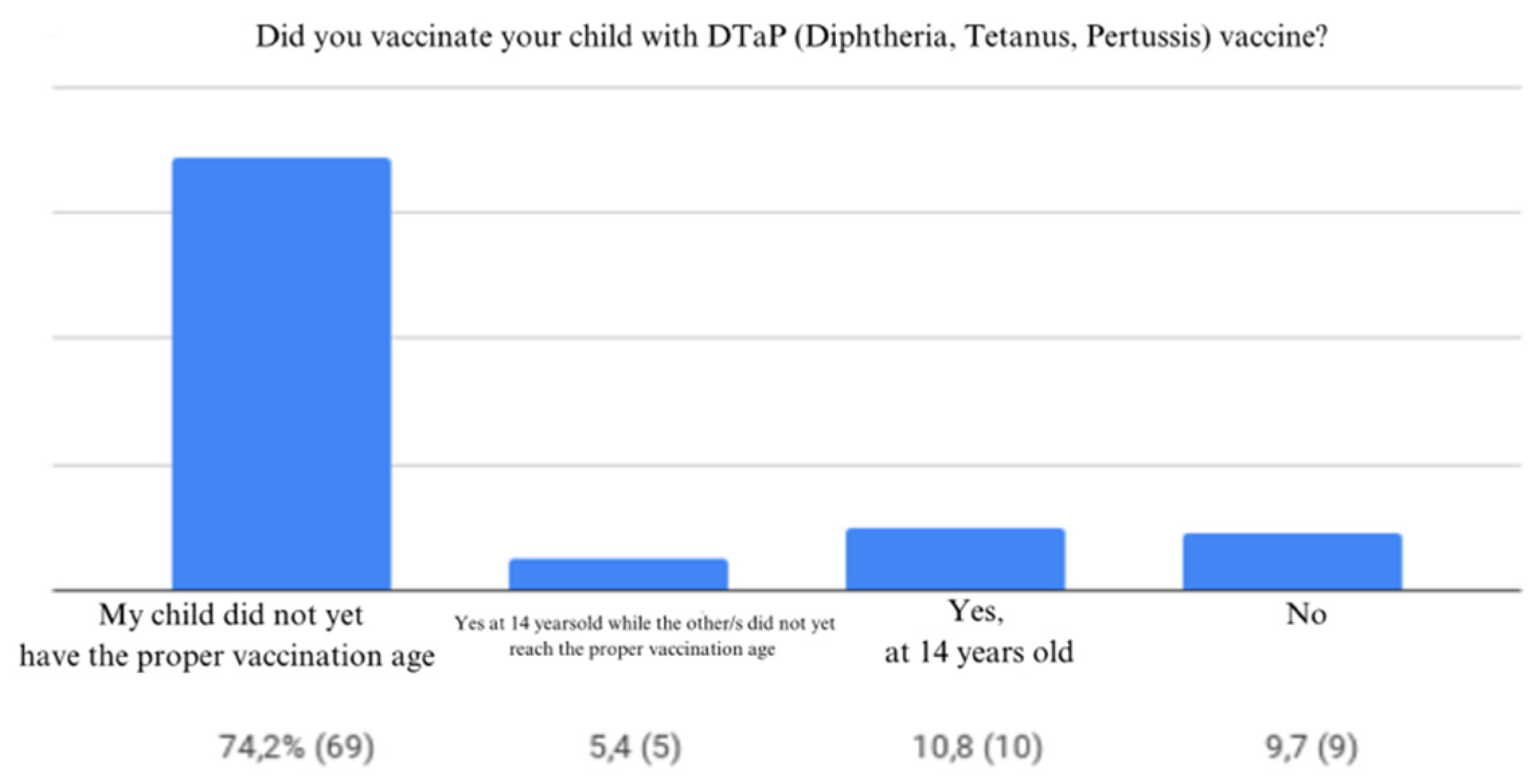

4.5.7. DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) Vaccine Administration

Figure 19 shows that 69 mothers (74.2%) affirmed did not administer the vaccine yet as their child was not old enough. 5 mothers (5.4%) vaccinated their children on proper age but on the same time these mothers have also children younger than 14 years old that are not eligible for DTaP vaccine (according to the national immunisation scheme). 10.8% (10 mothers) vaccinated their children, while 9.7%, 9 mothers were against vaccination.

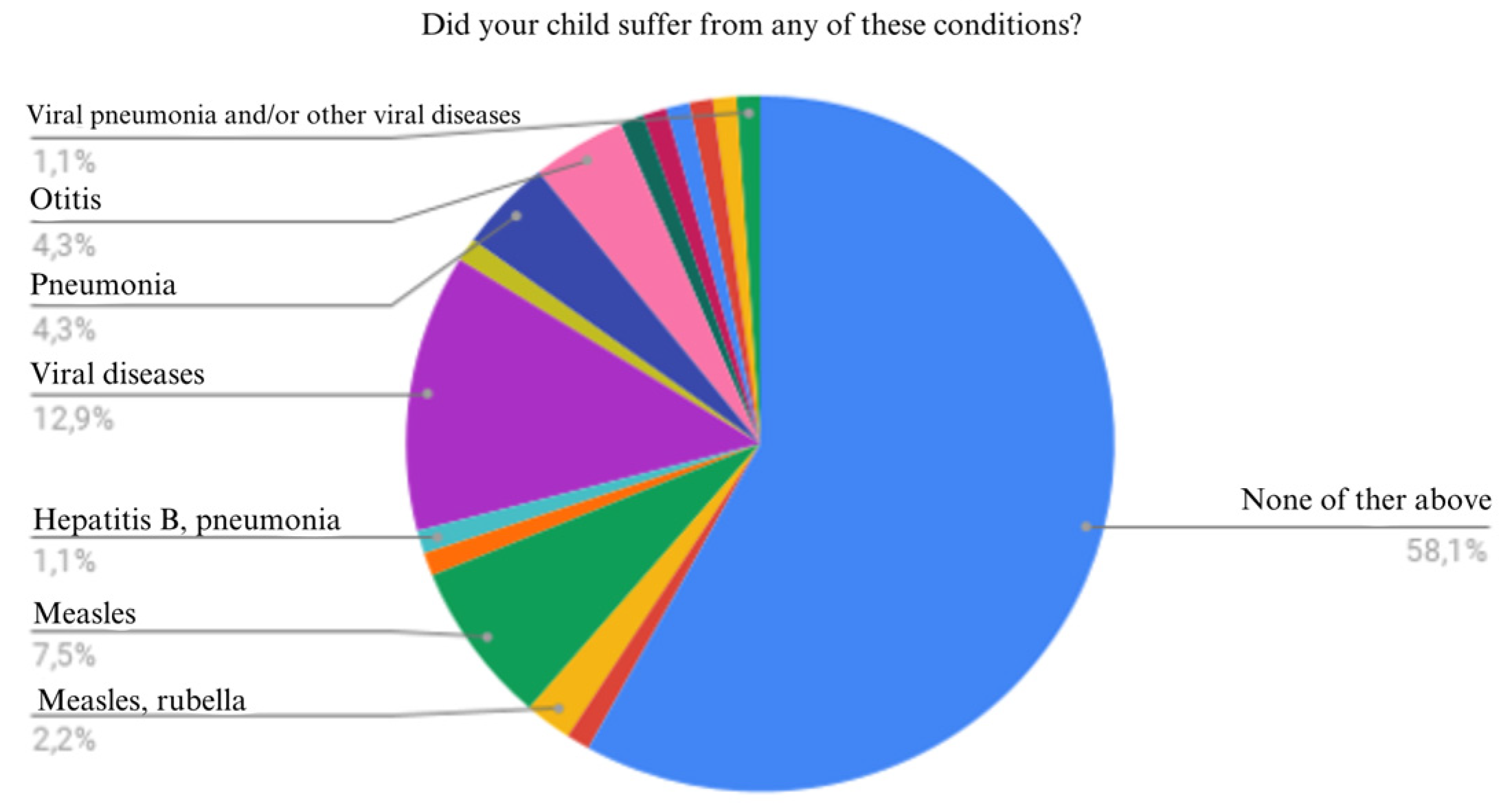

4.6. Children Medical History

4.6.1. History of Medical Conditions

As

Figure 20 shows 58.1% (54 answers) of mothers declared that their child did not suffer from any medical condition, while 12.9% (12 answers) recorded frequent viral diseases, 4.3% pneumonia, 4.3% (4 answers) otitis, 1.1% pneumonia, 1.1% pneumonia and hepatitis B, 7.5% measles and 2.2% rubella.

4.6.2. Symptoms Associated with Medical Conditions

According to

Figure 21 from all 93 recorded answers, 60 indicated (64.5%) that the children did not encounter any specific medical condition or pathology, nor was the case to declare any relevant symptoms. 7 mothers (7.5%) indicated that the symptomatology was mild, 16.1% (15 answers) moderate. Both mild and moderate symptomatology was described by 1 mother (1.1%), 2.2% mothers said that not all their children presented symptoms and 2.2% mothers reported asymptomatic diseases.

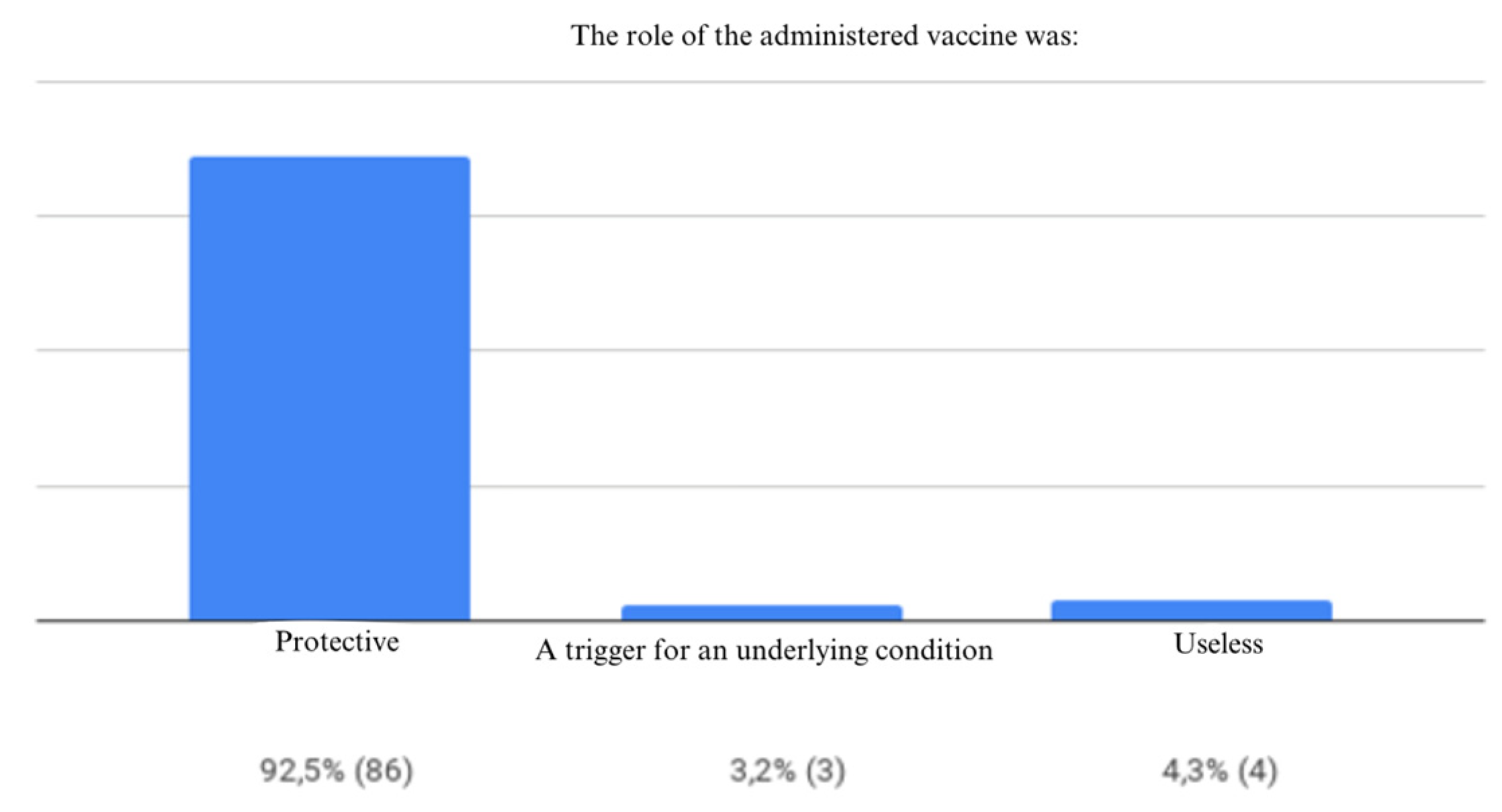

4.7. Vaccination Role

As

Figure 22 describes 86 answers (92.5%) were associated with the protective role of vaccination, 3.2% (3 mothers) said that the vaccine was responsible for a trigger for an underlying condition and 4.3% (4 mothers) said the vaccination role is useless.

4.7.1. Opinions Regarding Children Vaccination

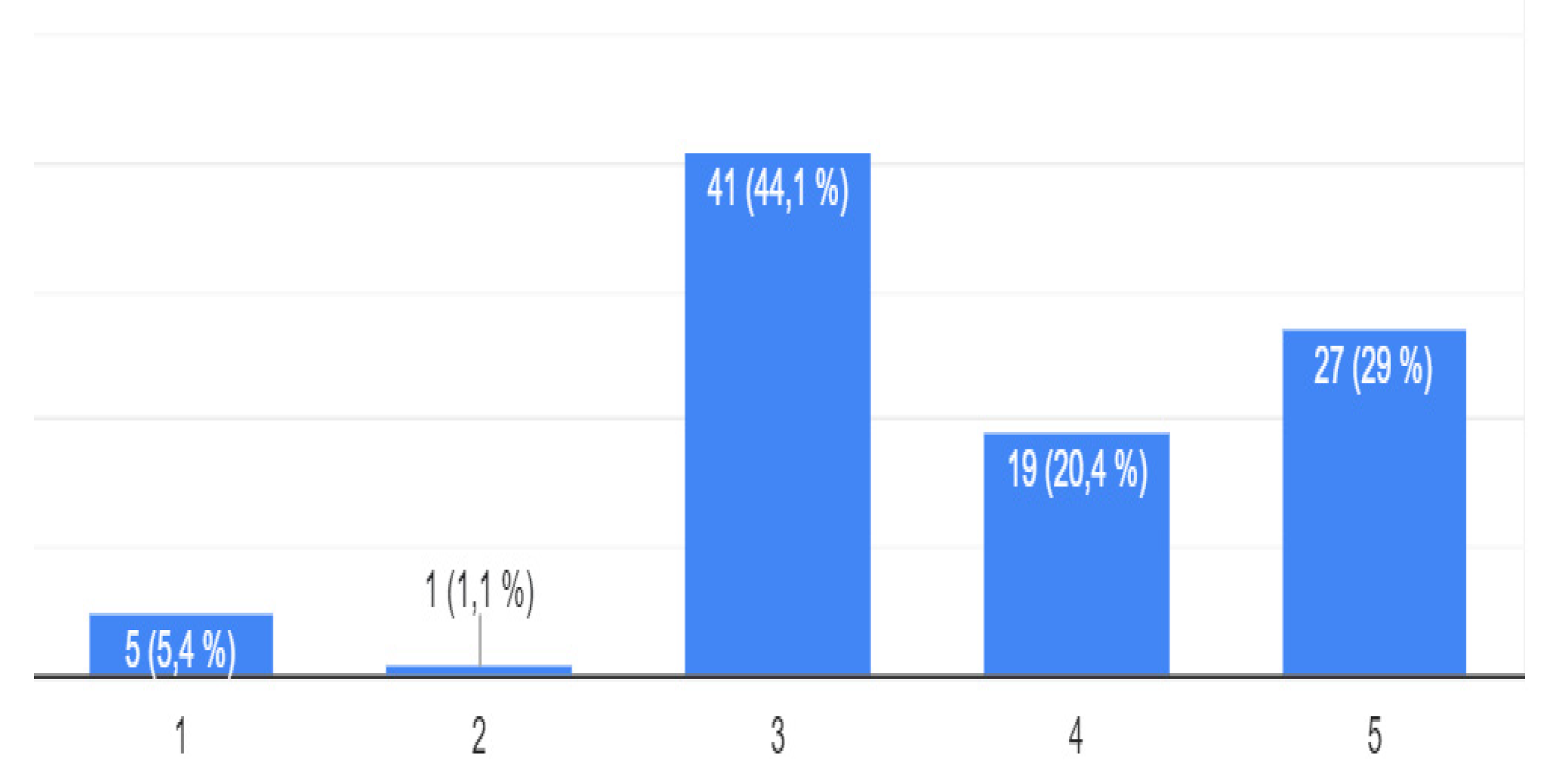

In

Figure 23, 1 is allocated to mothers that do not trust

vaccines, number 2 is associated with the idea that children vaccination was

wrong, 3 that children vaccination was a correct action, 4 means that mothers

trust vaccines and 5 allocated with the answer "I vaccinate my children

with vaccines outside the national immunisation scheme as well".

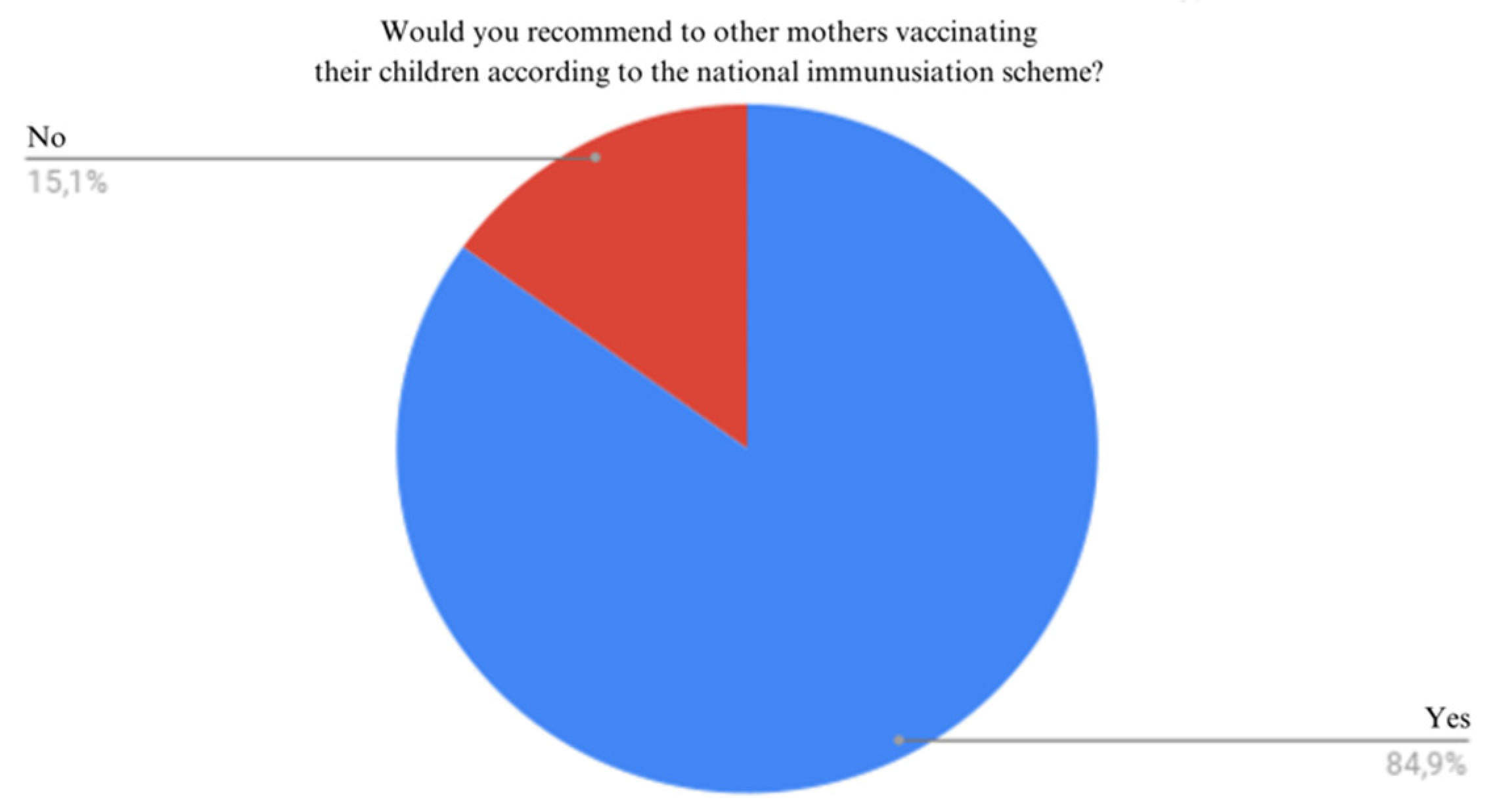

4.7.2. Vaccination Recommendation

79 mothers (84.9%) would recommend vaccination, 14 (15.1%) would not recommend to other mothers vaccination according to

Figure 24.

5. Discussion

By analysing all 93 answers, all mothers respected the national immunisation scheme vaccinations.

Vaccination is the most important tool in primary disease prevention and also one of the most cost-effective instruments in human health [

8].

Vaccine protection involves a complex interaction between innate immunity and cellular immunity. Between individuals there is a significant variation in post-vaccination immune responses both from a quantitative and qualitative standpoint. Variation in individual immunity responses influences efficacy and duration of protection [

9]

6. Conclusions

In spite of the fact that in the third millennium all population should be better informed regarding medical practices, especially if children are involved, there are still citizens that are not aware of the national immunisation scheme in Romania.

Nowadays natural births have been outnumbered by caesarean intervention. Awareness on this matter and risk-benefit assessment of caesarean interventions should be analysed. Family doctors, obstetricians should promote natural birth as a healthier, easy to recover both for the new-born and mother.

From all 142 children included in our study, most of them were born on term. A significant proportion of new-borns were breastfed in the first 6 months.

Our study involved 93 mothers. Unfortunately, some of the interviewed mothers expressed vaccine hesitancy.

Respiratory viral infections are problems that could be avoided if mothers would be open to vaccinate themselves during pregnancy.

Even if there were reported infections with agents for which vaccination has been administered, the symptoms reported in vaccinated children was mild to moderate with 1 declared case of severe symptomatology, proving that vaccines have a beneficial role in immune response during infections. Mothers' trust in vaccines and vaccine recommendations to other mothers was observed, this boosting the spread of vaccination advantages in immune response consolidations, even in premature new-borns.

A growing trend of hesitancy in administering the DTaP (10.8%) vaccine versus the MMR (8.6%) vaccine, suggesting perception changes in children vaccination safety and efficacy.

7. Study Limitations

Pneumococcal vaccine was introduced in Romania in 2013 and administered to children in regard with the available funding. 4 years later in 2017, the conjugated pneumococcal vaccine was officially introduced in the national immunisation scheme and administered together with the hexavalent vaccine at 2, 4 and 11 months. Not all the children received the pneumococcal vaccine due to its limited availability and an accurate comparison of mothers that chose and refused vaccination cannot be made.

Because 74.2% (69) answers were given by mothers with children younger than 14 years old, a precise conclusion on dTpa vaccination cannot be made. However, the other 37.5%, 24 mothers, decided to vaccinate their child.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Simbrac Mihaela Cristina, Borca Ciprian Ioan, Folescu Roxana and Sitaru Georgiana Patricia; Project administration, Miloicov Bacean Oana Codruta; Software, Văcaru Gabriel Cristian; Writing – original draft, Barabas Adina Giorgiana.

References

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016 Aug 19;14(8):e1002533. [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal B, González Á. Innate immune system. In: Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside [Internet] [Internet]. El Rosario University Press; 2013 [cited 2023 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459455/.

- Andrieș L, Barba D, Cernețchi O, et al. Sistemul imun congenital. În: Compendiu Imunologie Clinică. Chișinău; 2014. p. 38.

- Shukla VV, Shah RC. Vaccinations in Primary Care. Indian J Pediatr. 2018 Dec 1;85(12):1118–27.

- Pollard AJ, Bijker EM. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Feb;21(2):83–100.

- Amaya-Uribe L, Rojas M, Azizi G, Anaya JM, Gershwin ME. Primary immunodeficiency and autoimmunity: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2019 May;99:52–72. [CrossRef]

- Vaccination in patients with primary immune deficiency, secondary immune deficiency and autoimmunity with immune regulatory abnormalities.

- General overview. Public Health. https://health.ec.europa.eu/vaccination/overview_ro, 2023, September 15.

- Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination - PMC [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6431125/.

Figure 1.

Immune response after administering a vaccine [

5].

Figure 1.

Immune response after administering a vaccine [

5].

Figure 2.

Mothers' awareness on the Romanian National Immunisation Scheme.

Figure 2.

Mothers' awareness on the Romanian National Immunisation Scheme.

Figure 3.

Answers on the information source of Romanian national immunisation scheme.

Figure 3.

Answers on the information source of Romanian national immunisation scheme.

Figure 4.

Age range of respondents.

Figure 4.

Age range of respondents.

Figure 5.

Living area of respondents.

Figure 5.

Living area of respondents.

Figure 6.

Pregnancy type.

Figure 6.

Pregnancy type.

Figure 7.

Number of children.

Figure 7.

Number of children.

Figure 8.

Place of birth.

Figure 8.

Place of birth.

Figure 10.

Gestational age of the newborns.

Figure 10.

Gestational age of the newborns.

Figure 11.

Newborn nutrition.

Figure 11.

Newborn nutrition.

Figure 12.

Lactation period.

Figure 12.

Lactation period.

Figure 13.

Hepatitis B vaccination at birth.

Figure 13.

Hepatitis B vaccination at birth.

Figure 14.

Tuberculosis vaccination.

Figure 14.

Tuberculosis vaccination.

Figure 15.

Administration of DTa-VPI-Hib-HepB and DTP-VPOT-HepB vaccines.

Figure 15.

Administration of DTa-VPI-Hib-HepB and DTP-VPOT-HepB vaccines.

Figure 16.

Administration of pneumococcal vaccine.

Figure 16.

Administration of pneumococcal vaccine.

Figure 17.

Administration of MMR (mumps, measles, rubella) and measles vaccine.

Figure 17.

Administration of MMR (mumps, measles, rubella) and measles vaccine.

Figure 18.

Administration of tetravalent diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine.

Figure 18.

Administration of tetravalent diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine.

Figure 19.

DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) vaccine administration.

Figure 19.

DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) vaccine administration.

Figure 20.

History of medical conditions.

Figure 20.

History of medical conditions.

Figure 21.

Symptoms associated with medical conditions.

Figure 21.

Symptoms associated with medical conditions.

Figure 22.

Vaccination role.

Figure 22.

Vaccination role.

Figure 23.

Opinions regarding children vaccination.

Figure 23.

Opinions regarding children vaccination.

Figure 24.

Vaccination recommendation.

Figure 24.

Vaccination recommendation.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).