Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives The document comprehensively reviews the clinical applications and future potential of alpha-emitting radionuclides available for targeted alpha-particle therapy (TAT) in cancer treatment. The approval of radium-223 (Ra-223) therapy in 2013 marked a significant advancement in alpha-emitting therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals, which are primarily used in treatment of prostate cancer. The EU SECURE project was introduced as a major initiative to enhance the sustainability and safety of medical alpha-emitting radionuclides production in Europe. Methods: This literature review was conducted by a multidisciplinary team on selected radionuclides, including actinium-225, bismuth-213, astatine-211, lead-212, terbium-149, radium-22323 and thorium-227. These were selected based on their clinical significance, as identified in the EU PRISMAP project and subsequent literature searches. The review process involved searching major databases using specific keywords related to alpha-emitter therapy and was limited to articles in English. For each selected radionuclide, the physical characteristics, the radiochemistry, and the pre-clinical and clinical studies are explored. Results of the review show current and potential clinical applications of new alpha-emitting radionuclides, sharing insights from the SECURE consortium’s experiences and providing recommendations for future clinical trials to establish the therapeutic efficacy of these radionuclides. Conclusion: For each selected radionuclide, conclusion are reported in individual chapters. The results highlight the advantages of alpha particles in targeting cancer cells with minimal radiation to normal tissue, emphasising the need for high specificity and stability in delivery mechanisms, but also suggest that the full clinical potential of alpha particle therapy remains unexplored. Theranostic approach and dosimetric evaluations still represent relevant challenges.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

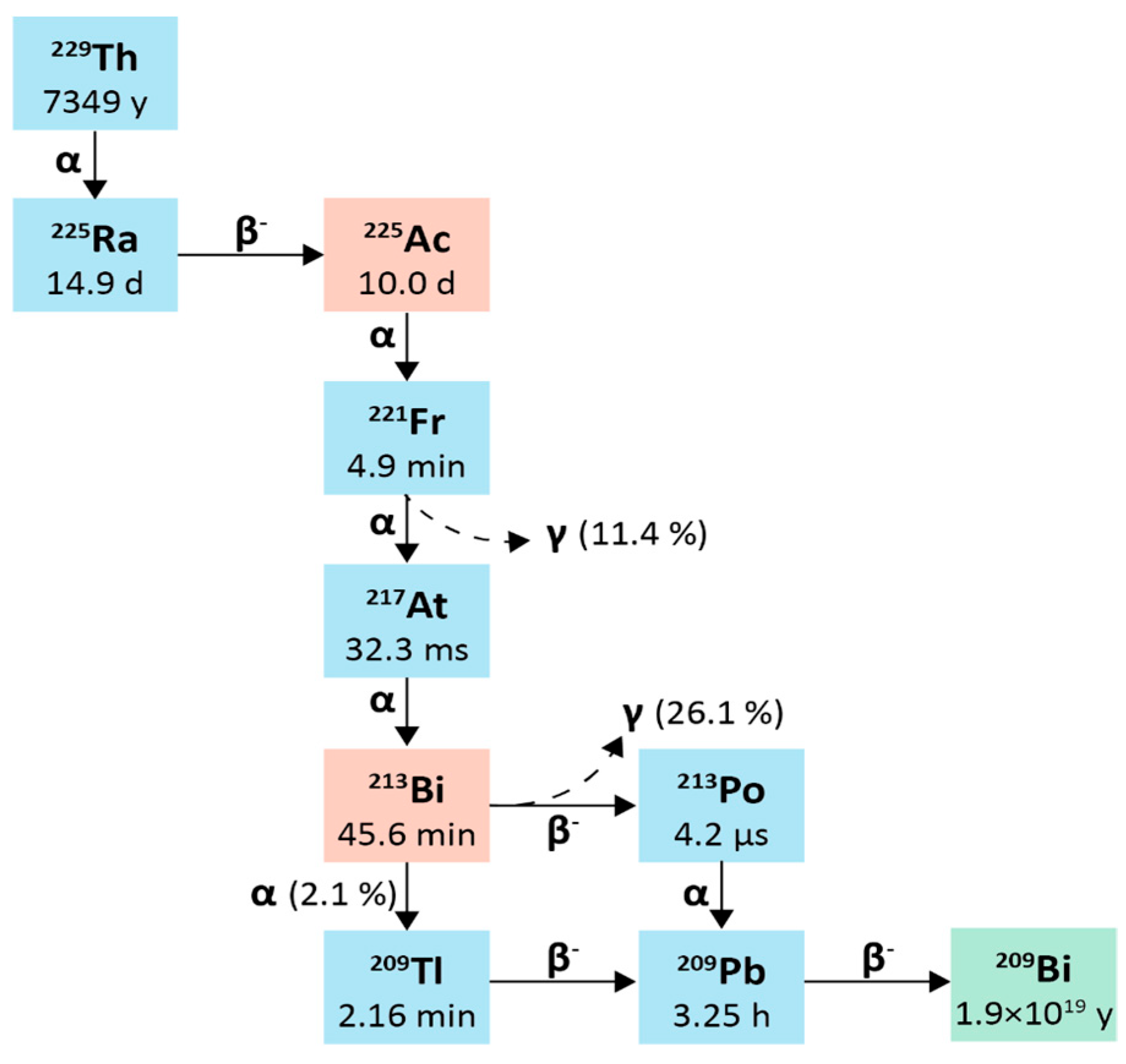

2.1. Actinium-225

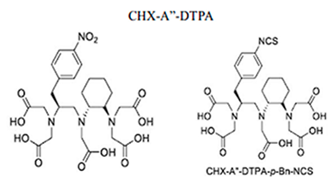

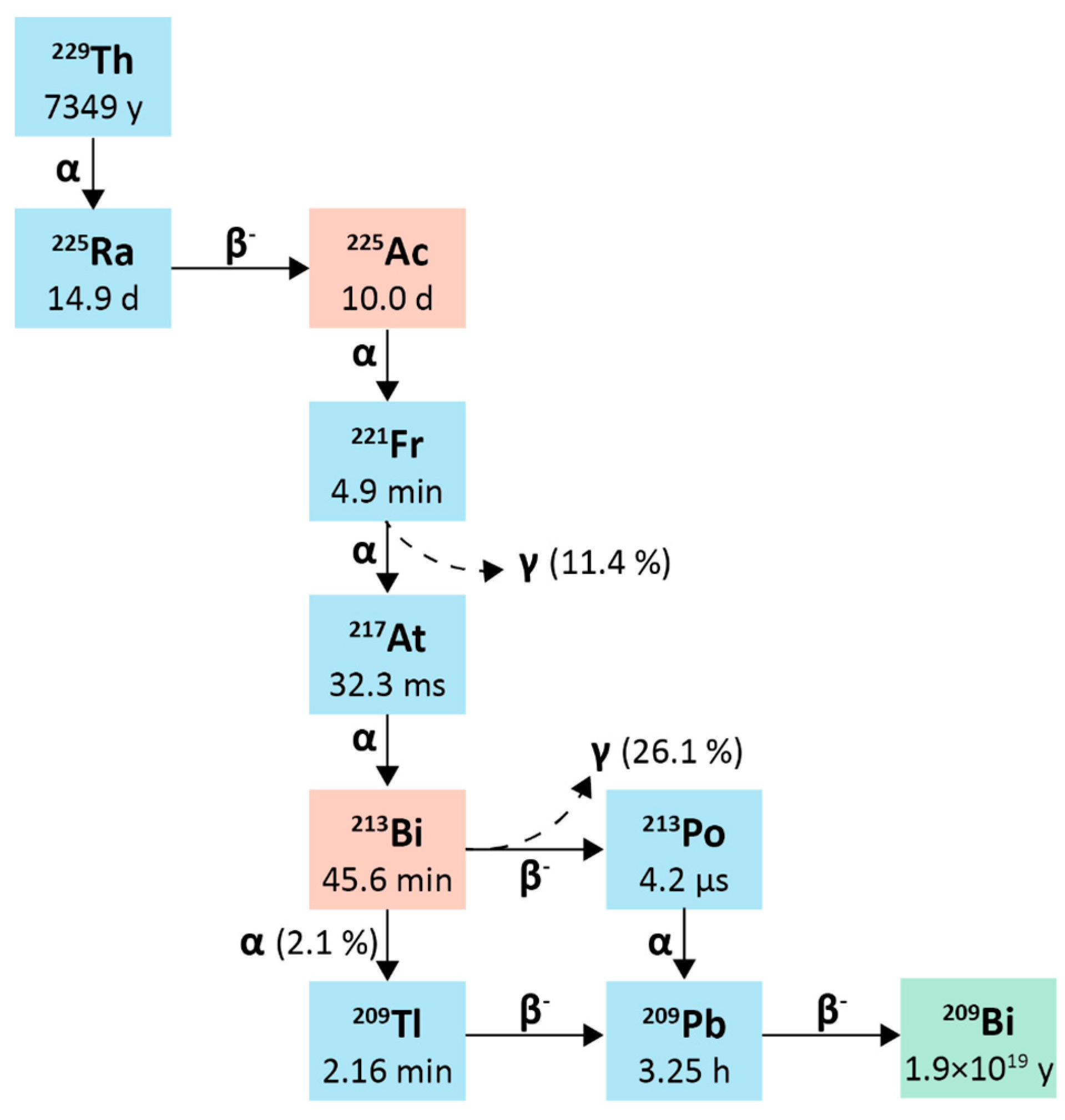

2.1.1. Physical Characteristics

2.1.1.1. Radiochemical Extraction from Thorium-229

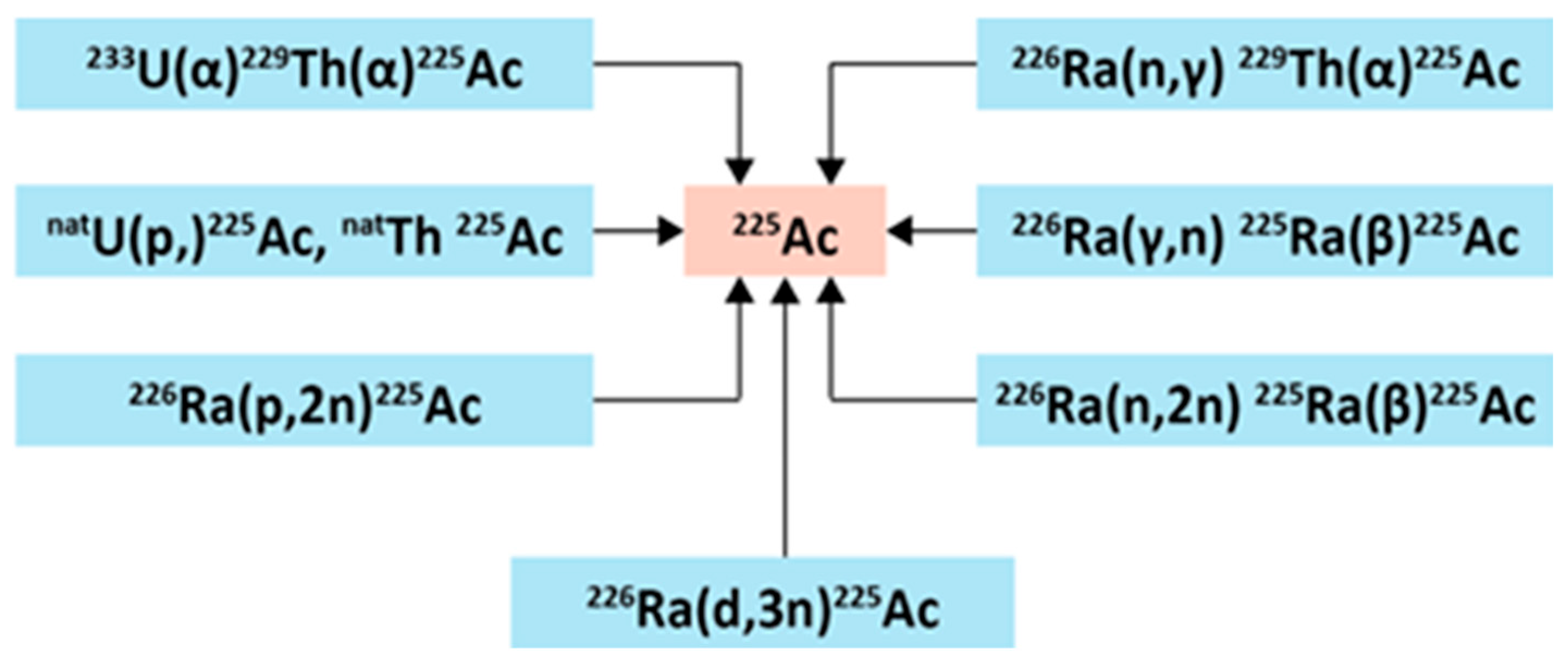

2.1.1.2. Accelerator-Based Routes

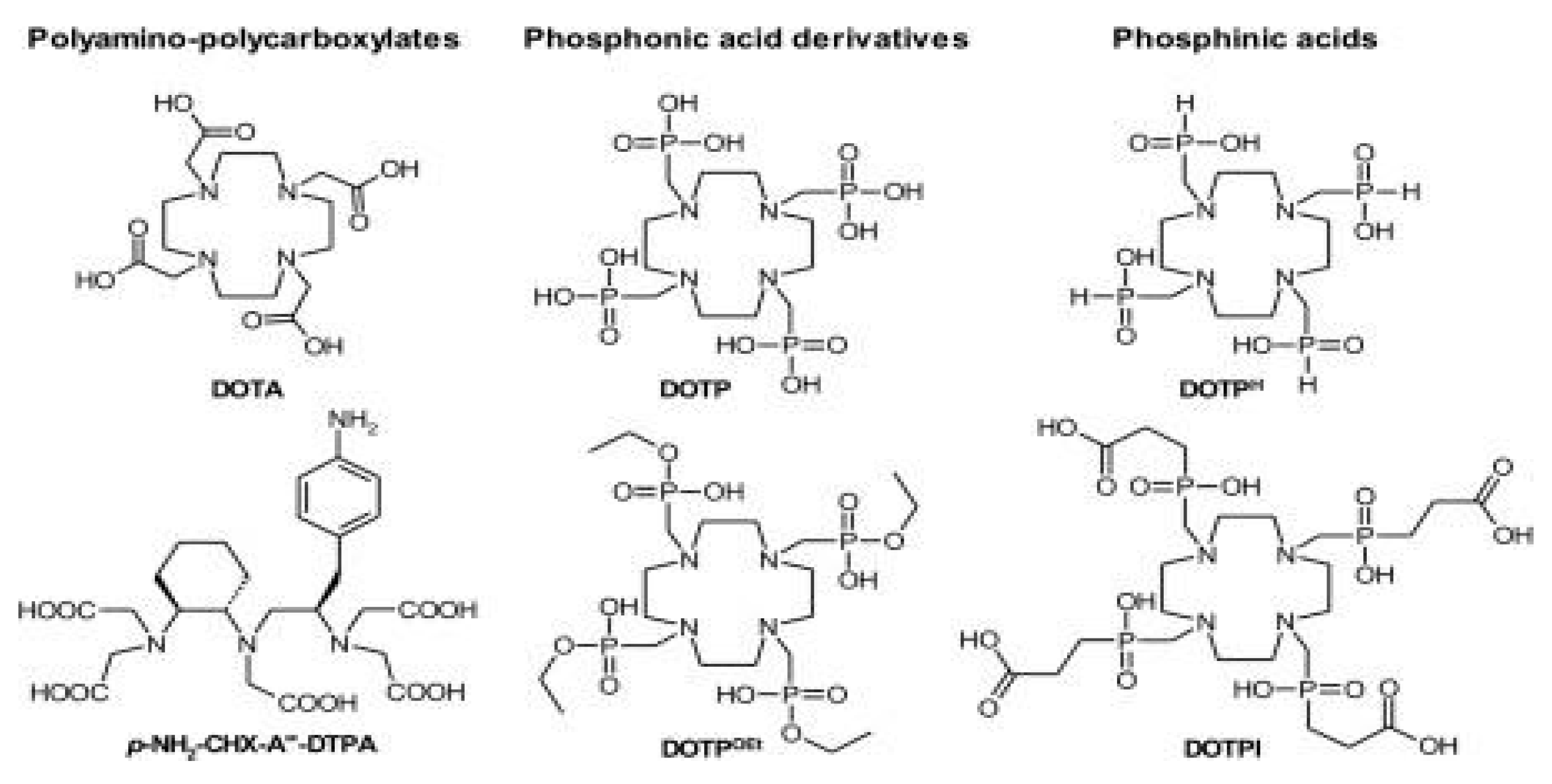

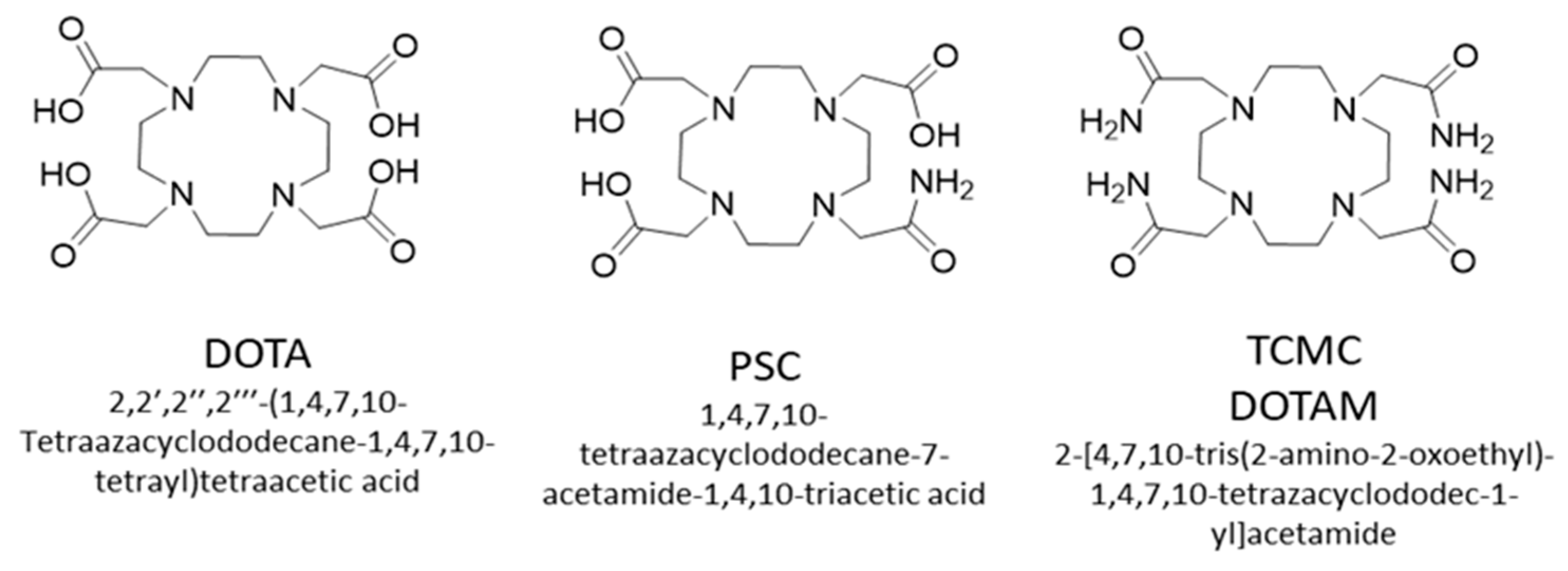

2.1.2. Radiochemistry

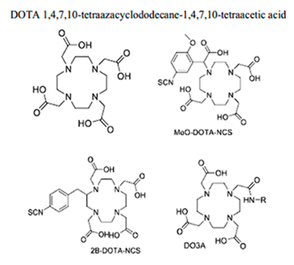

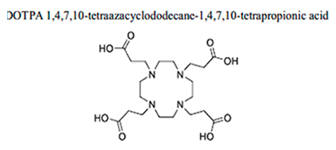

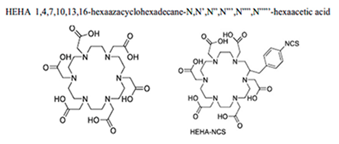

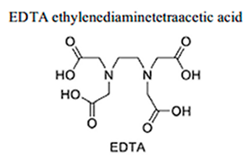

2.1.2.1. Chelating Agents for Actinium-225

2.1.2.2. Actinium-225 Labelled Nanoparticles

2.1.2.3. Assessing the Biodistribution of the Actinium-225 Decay Chain

2.1.3. Preclinical Studies

2.1.4. Clinical Studies

2.1.5. Conclusion

2.2. Bismuth-213

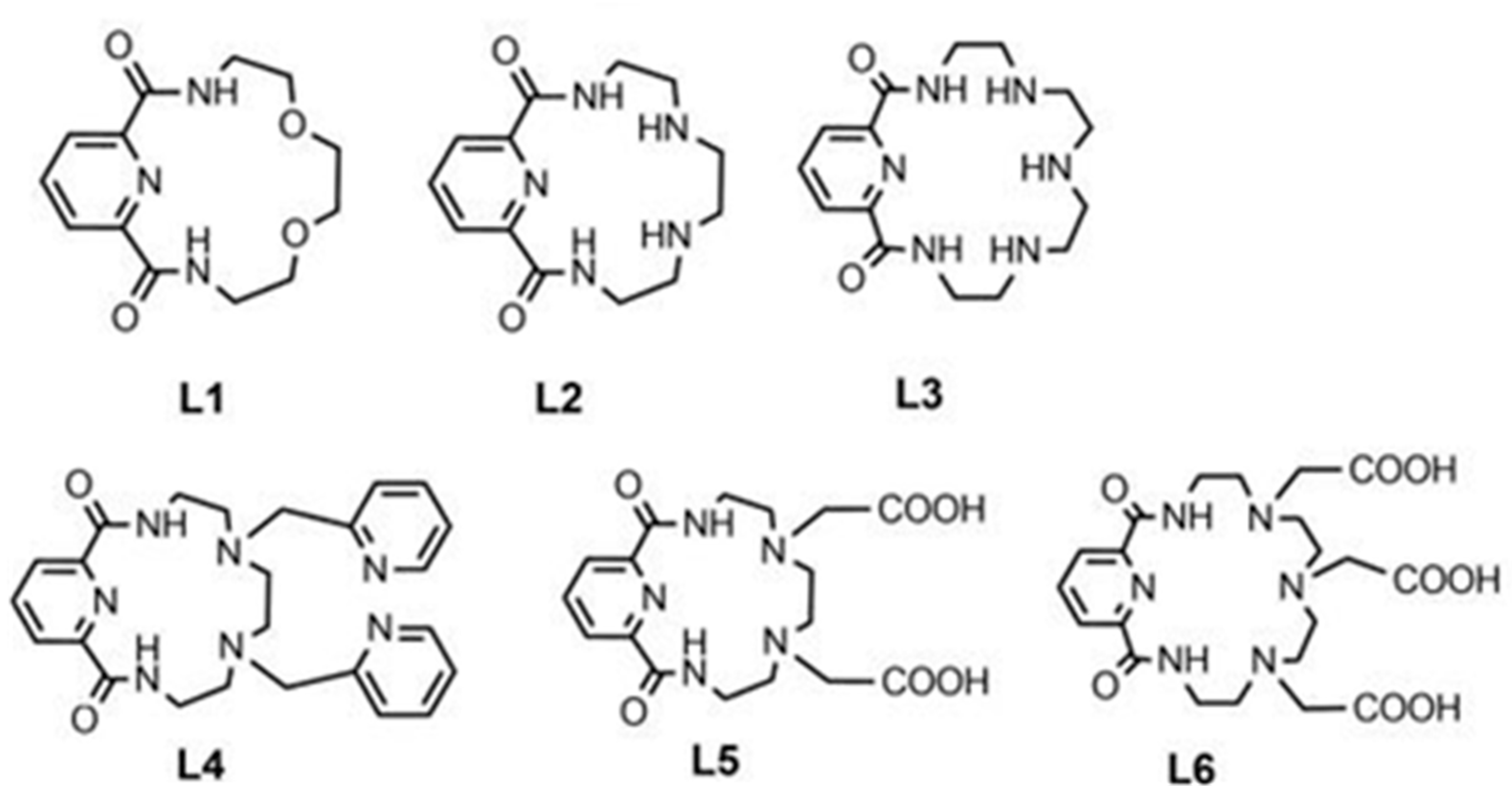

2.2.1. Physical Characteristics

2.2.2. Radiochemistry

2.2.3. Preclinical Studies

2.2.4. Clinical Studies

- Bi-213-radioimmunoconjugates (Bi-213-RICs) were also investigated for therapy of malignant melanoma [69].

- [213Bi]Bi-HuM195 was also successfully attempted for acute myelogenous leukaemia or chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CML), involving: 93% of the treated patients had reductions in circulating blasts, and 78% experienced a decline in bone marrow blasts, with no significant extramedullary toxicity reported [54].

- [213Bi]Bi-PSMA-617 for mCRPC, resulted in imaging response and a decrease in prostate-specific antigen levels, and [213Bi]Bi-DOTATOC in neuroendocrine tumours refractory to beta emitter 177Lu/90Y-DOTATOC, which led to a significant reduction in targeting agent uptake, i.e. probable reduction of lesion size [55].

2.2.4.1. Locoregional Administration

2.2.5. Conclusion

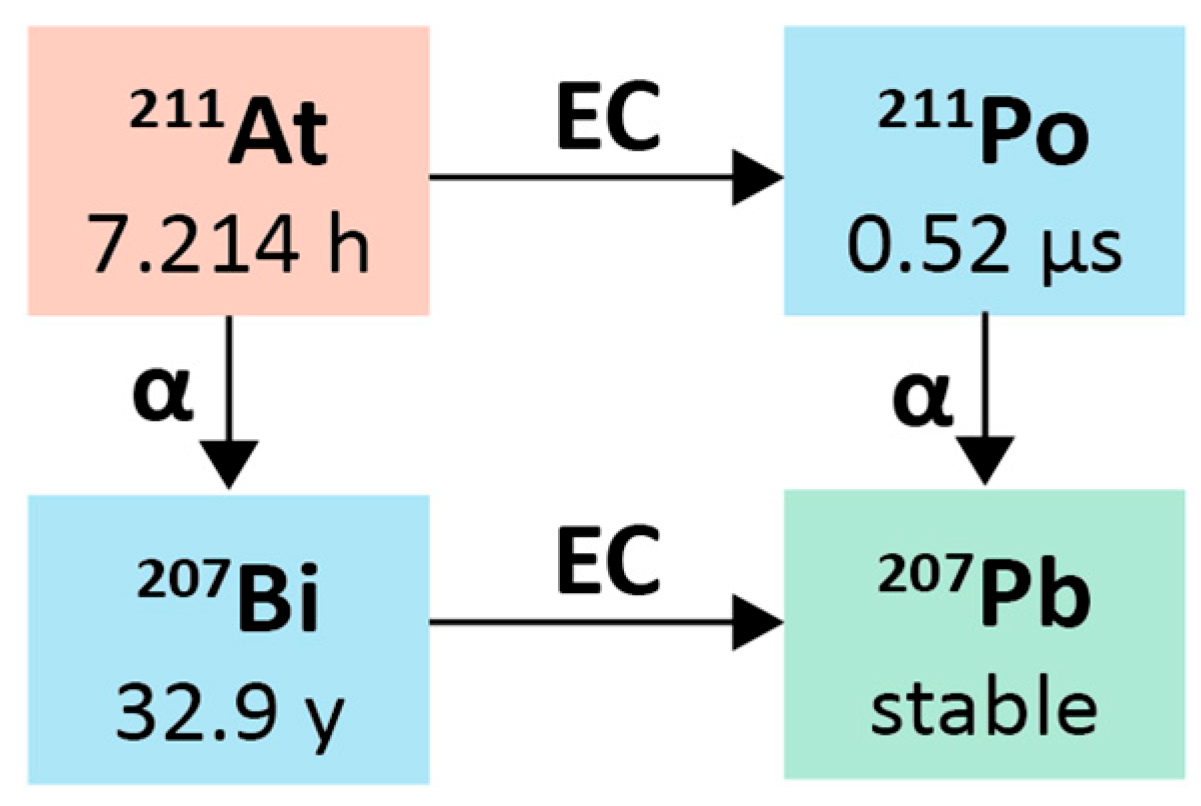

2.3. Astatine-211

2.3.1. Physical Characteristics

2.3.2. Radiochemistry

2.3.3. Preclinical Studies

2.3.4. Clinical Studies

2.3.5. Conclusion

2.4. Lead-212

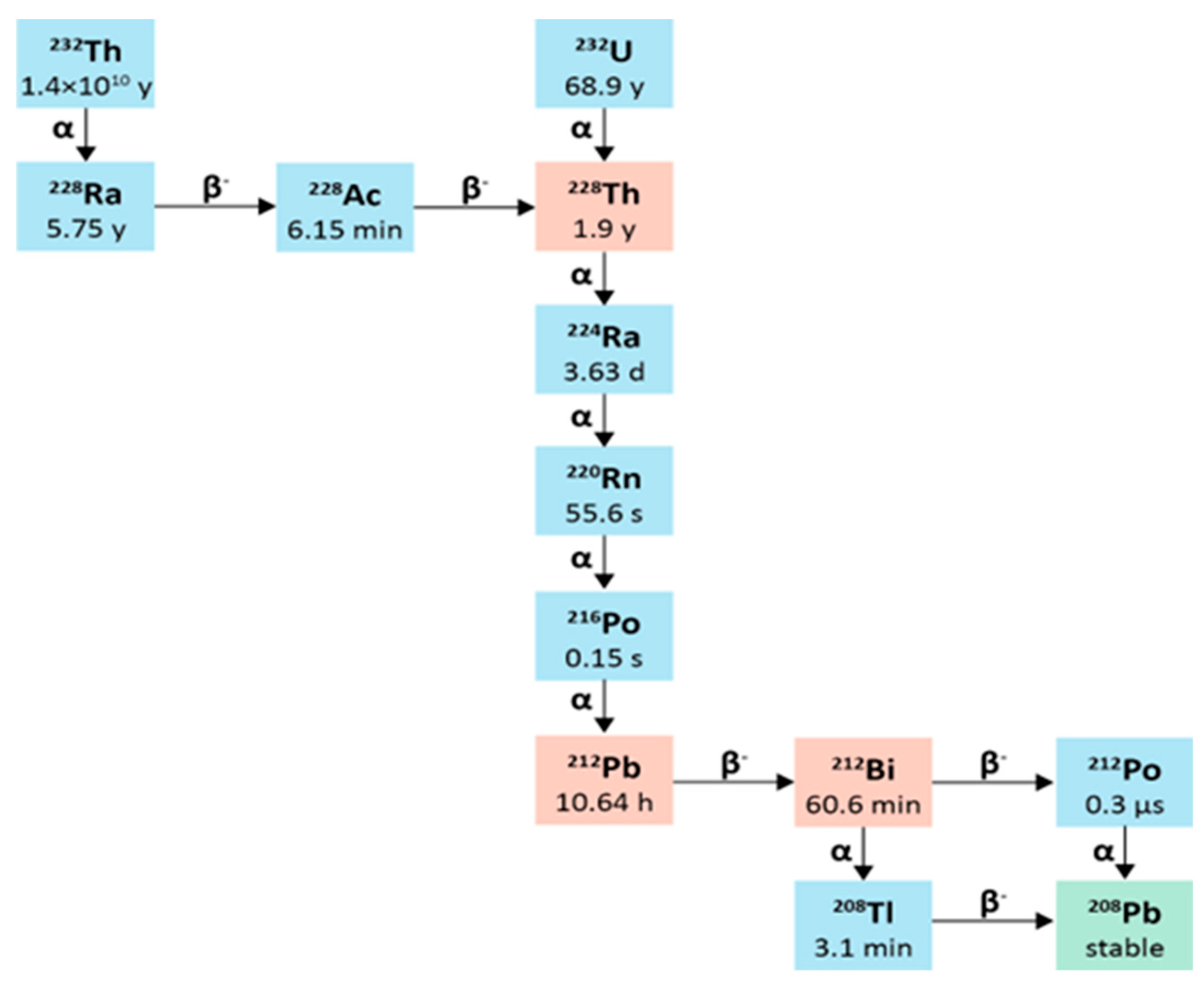

2.4.1. Physical Characteristics

2.4.2. Radiochemistry

2.4.3. Preclinical Studies

2.4.4. Clinical Studies

- [212Pb Pb-VMT-α-NET ([212Pb]Pb-PSC-PEG2-TOC) for somatostatin expressing neuroendocrine tumor (NCT06479811, NCT06427798)

- [212Pb]Pb-VMT01 ([212Pb]Pb- DOTA-PEG2-α-MSH for melanoma tumors expressing the melanocortin sub-type 1 receptor (MC1R) (NCT05655312) [113] .

2.4.5. Conclusion

2.5. Terbium-149

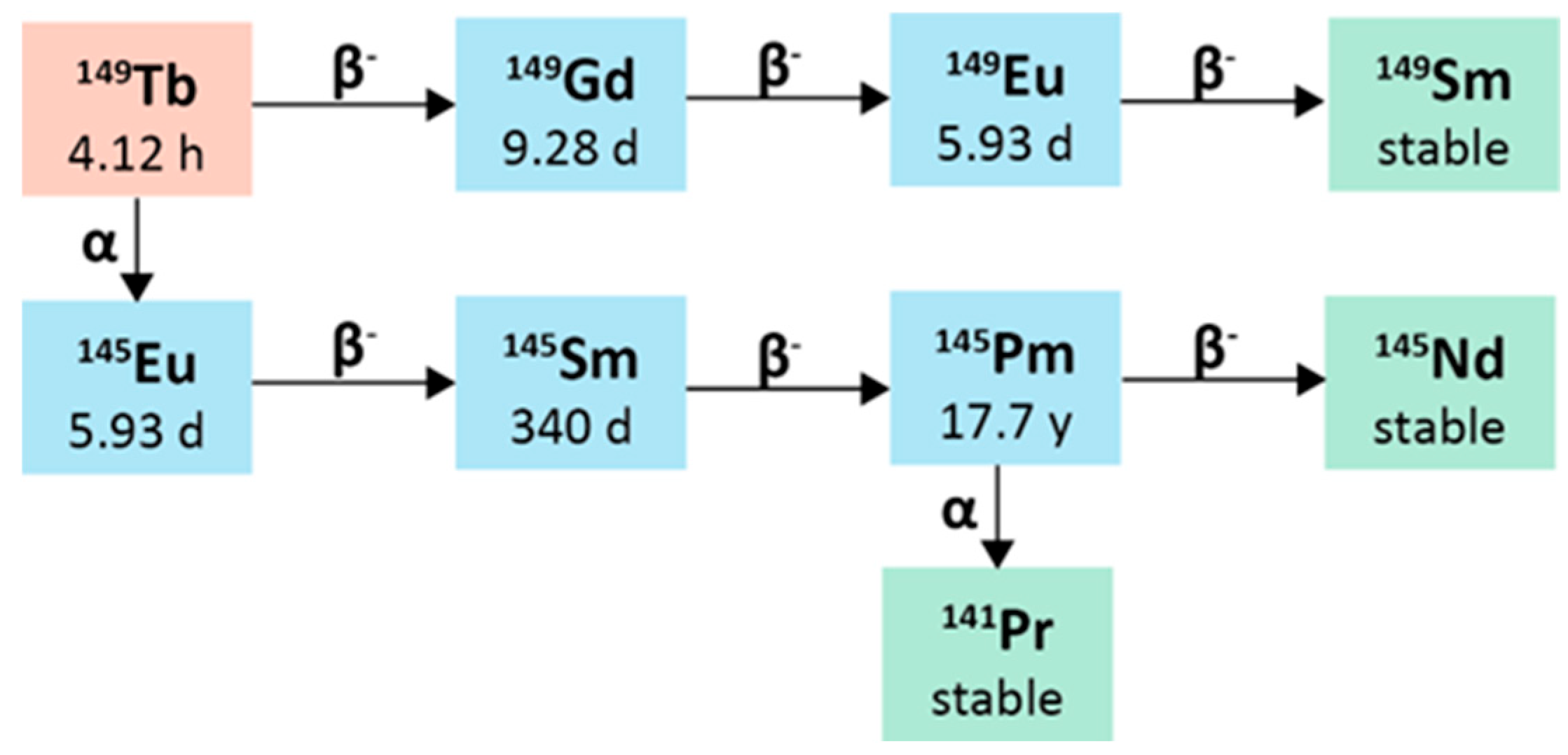

2.5.1. Physical Characteristics

2.5.2. Radiochemistry

2.5.3. Preclinical Studies

2.5.4. Clinical Studies

2.5.5. Conclusion

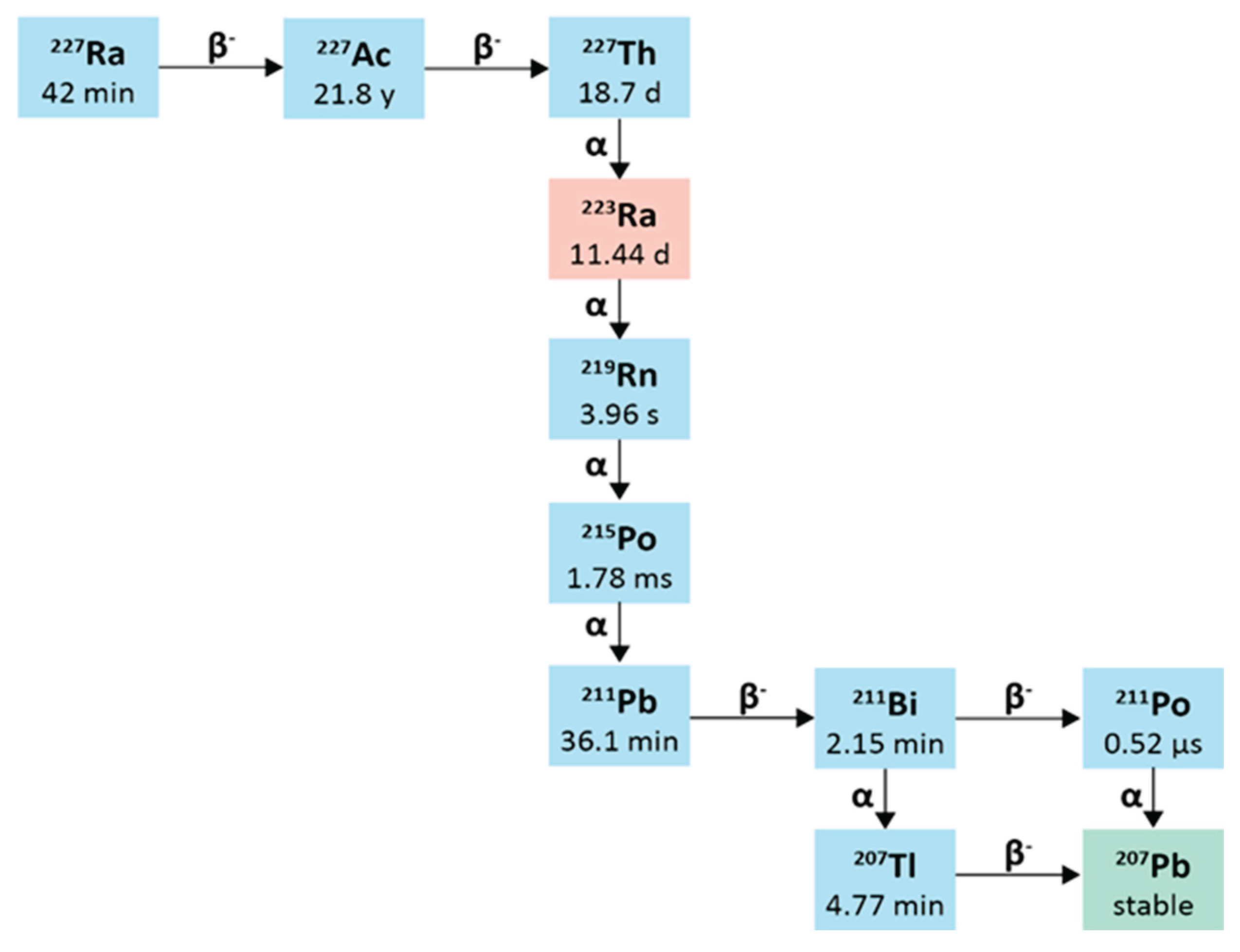

2.6. Radium-223

2.6.1. Physical Characteristics

2.6.2. Radiochemistry

2.6.3. Preclinical Studies

2.6.4. Clinical Studies

2.6.5. Conclusion

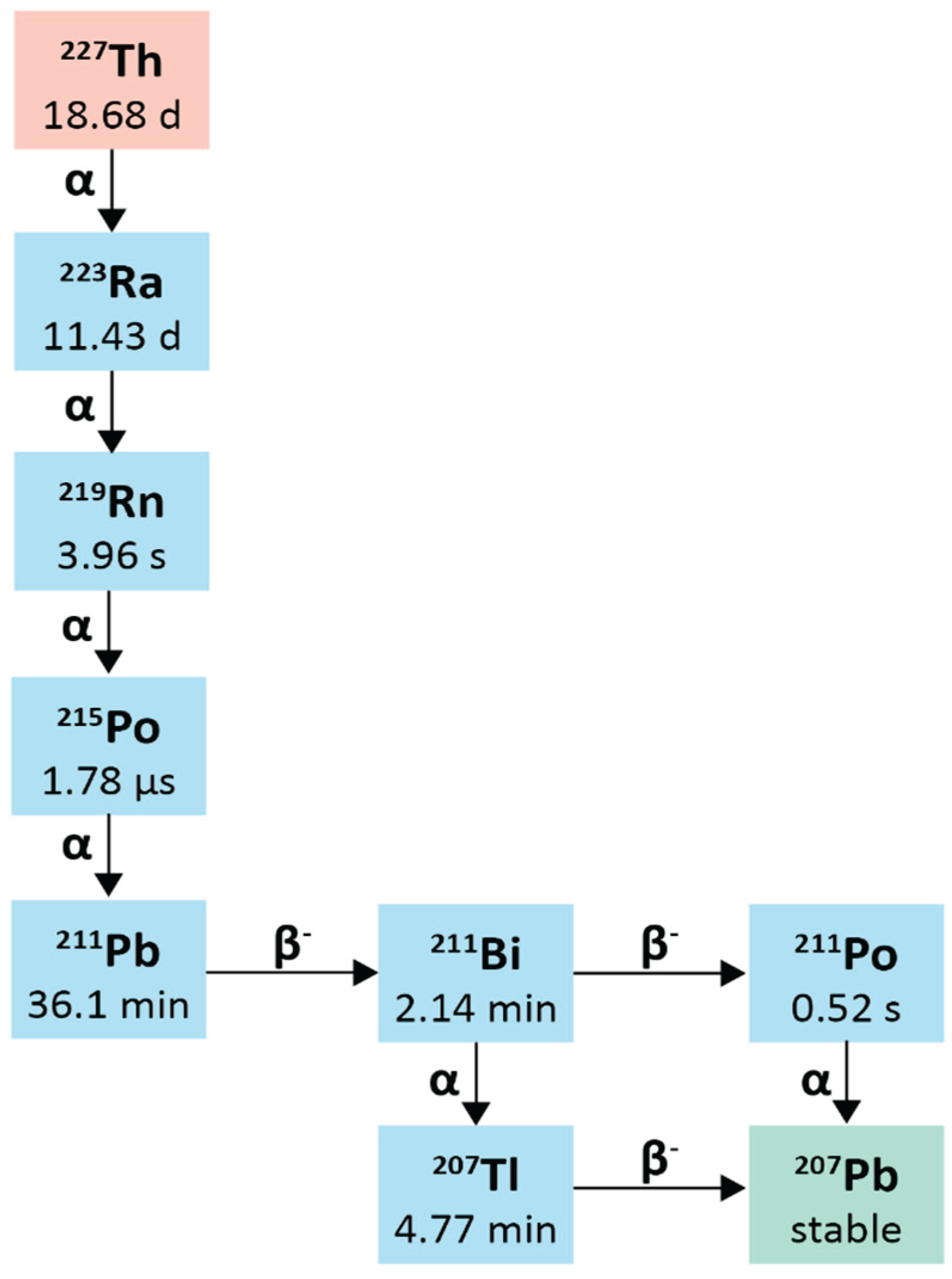

2.7. Thorium-227

2.6.1. Physical Characteristics

2.7.2. Radiochemistry

2.7.3. Preclinical Studies

2.7.4. Clinical Studies

- BAY2287411 (or MSLN-TTC) for solid tumors expressing mesothelin (NCT03507452),

- BAY2701439 (or HER2-TTC) for cancers with HER2 expression as breast cancer or gastric cancer (NCT04147819),

- BAY2315497 (or PSMA-TTC) for mCRPC (NCT03724747). Intermediate results from different studies have already been reported.

- BAY 1862864, which is a [227Th]Th-labelled CD22-targeting antibody, was injected into patients with CD22-positive relapsed/refractory B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (R/R-NHL) (NCT02581878), and the therapy resulted in safe and well-tolerated, with an objective response rate of 25% [150].

2.7.5. Conclusion

3. Discussion and General Recommendations

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eychenne, R.; Chérel, M.; Haddad, F.; Guérard, F.; Gestin, J.-F. Overview of the Most Promising Radionuclides for Targeted Alpha Therapy: The “Hopeful Eight. ” Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher-Lamarre, J.L.; Sanders, V.A.; Rahman, M.; Cutler, C.S.; Francesconi, L.C. Alpha Emitting Nuclides for Targeted Therapy. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 92, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, J.W. The Production of Ac-225. Curr. Radiopharm. 2018, 11, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Kratochwil, C.; Sathekge, M.; Krolicki, L.; Bruchertseifer, F. An Overview of Targeted Alpha Therapy with225 Actinium and213 Bismuth. Curr. Radiopharm. 2018, 11, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommé, S.; Marouli, M.; Suliman, G.; Dikmen, H.; Van Ammel, R.; Jobbágy, V.; Dirican, A.; Stroh, H.; Paepen, J.; Bruchertseifer, F.; et al. Measurement of the 225Ac Half-Life. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012, 70, 2608–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, G.; Pommé, S.; Marouli, M.; Van Ammel, R.; Stroh, H.; Jobbágy, V.; Paepen, J.; Dirican, A.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Apostolidis, C.; et al. Half-Lives of 221Fr, 217At, 213Bi, 213Po and 209Pb from the 225Ac Decay Series. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2013, 77, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.J.B.; Andersson, J.D.; Wuest, F. Targeted Alpha Therapy: Progress in Radionuclide Production, Radiochemistry, and Applications. Pharmaceutics 2020, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahenkorah, S.; Cassells, I.; Deroose, C.M.; Cardinaels, T.; Burgoyne, A.R.; Bormans, G.; Ooms, M.; Cleeren, F. Bismuth-213 for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy: From Atom to Bedside. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheinberg, D.; R. McDevitt, M. Actinium-225 in Targeted Alpha-Particle Therapeutic Applications. Curr. Radiopharm. 2011, 4, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, R. Managing the Uranium-233 Stockpile of the United States. Sci. Glob. Secur. 2013, 21, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.K.H.; Ramogida, C.F.; Schaffer, P.; Radchenko, V. Development of225 Ac Radiopharmaceuticals: TRIUMF Perspectives and Experiences. Curr. Radiopharm. 2018, 11, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, R.A.; Malkemus, D.; Mirzadeh, S. Production of Actinium-225 for Alpha Particle Mediated Radioimmunotherapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2005, 62, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolidis, C.; Molinet, R.; Rasmussen, G.; Morgenstern, A. Production of Ac-225 from Th-229 for Targeted α Therapy. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 6288–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotovskii, A.A.; Nerozin, N.A.; Prokof’ev, I.V.; Shapovalov, V.V.; Yakovshchits, Yu.A.; Bolonkin, A.S.; Dunin, A.V. Isolation of Actinium-225 for Medical Purposes. Radiochemistry 2015, 57, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahenkorah, S.; Cassells, I.; Deroose, C.M.; Cardinaels, T.; Burgoyne, A.R.; Bormans, G.; Ooms, M.; Cleeren, F. Bismuth-213 for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy: From Atom to Bedside. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Bruchertseifer, F. Supply and Clinical Application of Actinium-225 and Bismuth-213. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2020, 50, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Nolen, J.A.; Kroc, T.; Gomes, I.; Horwitz, E. Philip.; Mcalister, D.R. PRODUCTION OF ACTINIUM-225 VIA HIGH ENERGY PROTON INDUCED SPALLATION OF THORIUM-232. In Proceedings of the Applications of High Intensity Proton Accelerators; WORLD SCIENTIFIC: Fermilab, Chicago, June 2010; pp. 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi, M.; Dupis, E.; Engle, J.W.; Nortier, F.M.; Fassbender, M.E.; Simon, S.; Birnbaum, E.R.; Atcher, R.W.; John, K.D.; Rixe, O.; et al. Alpha-Emitters and Targeted Alpha Therapy in Oncology: From Basic Science to Clinical Investigations. Target. Oncol. 2018, 13, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, A.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Apostolidis, C. Bismuth-213 and Actinium-225 – Generator Performance and Evolving Therapeutic Applications of Two Generator-Derived Alpha-Emitting Radioisotopes. Curr. Radiopharm. 2012, 5, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogle, S.; Boll, R.A.; Murphy, K.; Denton, D.; Owens, A.; Haverlock, T.J.; Garland, M.; Mirzadeh, S. Reactor Production of Thorium-229. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2016, 114, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Rathke, H.; Bronzel, M.; Apostolidis, C.; Weichert, W.; Haberkorn, U.; Giesel, F.L.; Morgenstern, A. Targeted α-Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer with225 Ac-PSMA-617: Dosimetry Estimate and Empiric Dose Finding. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1624–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, M.; Krall, L.; Ewing, R.C. Is Nuclear Fission a Sustainable Source of Energy? MRS Bull. 2012, 37, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehr, C.; Bénard, F.; Buckley, K.; Crawford, J.; Gottberg, A.; Hanemaayer, V.; Kunz, P.; Ladouceur, K.; Radchenko, V.; Ramogida, C.; et al. Medical Isotope Production at TRIUMF – from Imaging to Treatment. Phys. Procedia 2017, 90, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, J.R.; Medvedev, D.G.; Engle, J.W.; Copping, R.; Fitzsimmons, J.M.; Radchenko, V.; Cooley, J.C.; Fassbender, M.E.; Denton, D.L.; Murphy, K.E.; et al. Large Scale Accelerator Production of 225Ac: Effective Cross Sections for 78–192 MeV Protons Incident on 232Th Targets. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2016, 118, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, J.W.; Mashnik, S.G.; John, K.D.; Ballard, B.; Birnbaum, E.R.; Bitteker, L.J.; Couture, A.; Fassbender, M.E.; Goff, G.S.; Gritzo, R.; et al. 225Ac and 223Ra Production via 800MeV Proton Irradiation of Natural Thorium Targets. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012, 70, 2590–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, J.W.; Mashnik, S.G.; John, K.D.; Hemez, F.; Ballard, B.; Bach, H.; Birnbaum, E.R.; Bitteker, L.J.; Couture, A.; Dry, D.; et al. Proton-Induced Cross Sections Relevant to Production of 225Ac and 223Ra in Natural Thorium Targets below 200MeV. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012, 70, 2602–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliev, R.A.; Ermolaev, S.V.; Vasiliev, A.N.; Ostapenko, V.S.; Lapshina, E.V.; Zhuikov, B.L.; Zakharov, N.V.; Pozdeev, V.V.; Kokhanyuk, V.M.; Myasoedov, B.F.; et al. Isolation of Medicine-Applicable Actinium-225 from Thorium Targets Irradiated by Medium-Energy Protons. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2014, 32, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastren, T.; Radchenko, V.; Owens, A.; Copping, R.; Boll, R.; Griswold, J.R.; Mirzadeh, S.; Wyant, L.E.; Brugh, M.; Engle, J.W.; et al. Simultaneous Separation of Actinium and Radium Isotopes from a Proton Irradiated Thorium Matrix. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radchenko, V.; Engle, J.W.; Wilson, J.J.; Maassen, J.R.; Nortier, F.M.; Taylor, W.A.; Birnbaum, E.R.; Hudston, L.A.; John, K.D.; Fassbender, M.E. Application of Ion Exchange and Extraction Chromatography to the Separation of Actinium from Proton-Irradiated Thorium Metal for Analytical Purposes. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1380, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramogida, C.F.; Robertson, A.K.H.; Jermilova, U.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Kunz, P.; Lassen, J.; Bratanovic, I.; Brown, V.; Southcott, L.; et al. Evaluation of Polydentate Picolinic Acid Chelating Ligands and an α-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone Derivative for Targeted Alpha Therapy Using ISOL-Produced 225Ac. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2019, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, A.K.H.; McNeil, B.L.; Yang, H.; Gendron, D.; Perron, R.; Radchenko, V.; Zeisler, S.; Causey, P.; Schaffer, P. 232 Th-Spallation-Produced225 Ac with Reduced227 Ac Content. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 12156–12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesteruk, K.P.; Ramseyer, L.; Carzaniga, T.S.; Braccini, S. Measurement of the Beam Energy Distribution of a Medical Cyclotron with a Multi-Leaf Faraday Cup. Instruments 2019, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Nagatsu, K.; Tsuji, A.B.; Zhang, M.-R. Research and Development for Cyclotron Production of 225Ac from 226Ra—The Challenges in a Country Lacking Natural Resources for Medical Applications. Processes 2022, 10, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, C.; Molinet, R.; McGinley, J.; Abbas, K.; Möllenbeck, J.; Morgenstern, A. Cyclotron Production of Ac-225 for Targeted Alpha therapy11Dedicated to Prof. Dr. Franz Baumgärtner on the Occasion of His 75th Birthday. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2005, 62, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, A.; Abbas, K.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Apostolidis, C. Production of Alpha Emitters for Targeted Alpha Therapy. Curr. Radiopharm. 2008, 1, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, O.D.; Sabel’nikov, A.V.; Dmitriev, S.N. Preparation of 225Ac by 226Ra(γ, n) Photonuclear Reaction on an Electron Accelerator, MT-25 Microtron. Radiochemistry 2006, 48, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, G.; Meriarty, H.; Metcalfe, P.; Knittel, T.; Allen, B.J. Production of Ac-225 for Cancer Therapy by Photon-Induced Transmutation of Ra-226. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2007, 65, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruchertseifer, F.; Kellerbauer, A.; Malmbeck, R.; Morgenstern, A. Targeted Alpha Therapy with Bismuth-213 and Actinium-225: Meeting Future Demand. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2019, 62, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, B.; Bilewicz, A. The Hydrolysis of Actinium. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2004, 261, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, H.; Solache-Ríos, M.; Jiménez-Reyes, M.; Ramírez-García, J.J.; Rojas-Hernández, A. Effect of Chloride Ions on the Hydrolysis of Trivalent Lanthanum, Praseodymium and Lutetium in Aqueous Solutions of 2 M Ionic Strength. J. Solut. Chem. 2005, 34, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, M.G.; Stein, B.W.; Batista, E.R.; Berg, J.M.; Birnbaum, E.R.; Engle, J.W.; John, K.D.; Kozimor, S.A.; Lezama Pacheco, J.S.; Redman, L.N. Synthesis and Characterization of the Actinium Aquo Ion. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.A.; Glowienka, K.A.; Boll, R.A.; Deal, K.A.; Brechbiel, M.W.; Stabin, M.; Bochsler, P.N.; Mirzadeh, S.; Kennel, S.J. Comparison of 225actinium Chelates: Tissue Distribution and Radiotoxicity. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1999, 26, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, J.; Atcher, R.; Cutler, C. Development of a Prelabeling Approach for a Targeted Nanochelator. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2015, 305, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, M.L.; Villa, C.H.; Ananta, J.S.; Law, J.J.; Scheinberg, D.A.; Wilson, L.J. Encapsulation of α-Particle–Emitting225 Ac3+ Ions Within Carbon Nanotubes. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, M.F.; Woodward, J.; Boll, R.A.; Wall, J.S.; Rondinone, A.J.; Kennel, S.J.; Mirzadeh, S.; Robertson, J.D. Gold Coated Lanthanide Phosphate Nanoparticles for Targeted Alpha Generator Radiotherapy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; De Kruijff, R.M.; Rol, A.; Thijssen, L.; Mendes, E.; Morgenstern, A.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Stuart, M.C.A.; Wolterbeek, H.T.; Denkova, A.G. Retention Studies of Recoiling Daughter Nuclides of 225Ac in Polymer Vesicles. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2014, 85, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Bandekar, A.; Sempkowski, M.; Banerjee, S.R.; Pomper, M.G.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Sofou, S. Nanoconjugation of PSMA-Targeting Ligands Enhances Perinuclear Localization and Improves Efficacy of Delivered Alpha-Particle Emitters against Tumor Endothelial Analogues. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandekar, A.; Zhu, C.; Jindal, R.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Sofou, S. Anti–Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Liposomes Loaded with225 Ac for Potential Targeted Antivascular α-Particle Therapy of Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kruijff, R.; Wolterbeek, H.; Denkova, A. A Critical Review of Alpha Radionuclide Therapy—How to Deal with Recoiling Daughters? Pharmaceuticals 2015, 8, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Swart, J.; Chan, H.S.; Goorden, M.C.; Morgenstern, A.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Beekman, F.J.; De Jong, M.; Konijnenberg, M.W. Utilizing High-Energy γ-Photons for High-Resolution213 Bi SPECT in Mice. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.K.H.; Ramogida, C.F.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C.; Blinder, S.; Kunz, P.; Sossi, V.; Schaffer, P. Multi-Isotope SPECT Imaging of the225 Ac Decay Chain: Feasibility Studies. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 4406–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordier, D.; Forrer, F.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Good, S.; Müller-Brand, J.; Mäcke, H.; Reubi, J.C.; Merlo, A. Targeted Alpha-Radionuclide Therapy of Functionally Critically Located Gliomas with 213Bi-DOTA-[Thi8,Met(O2)11]-Substance P: A Pilot Trial. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurcic, J.G.; Rosenblat, T.L. Targeted Alpha-Particle Immunotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2014, e126–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; Giesel, F.L.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Mier, W.; Apostolidis, C.; Boll, R.; Murphy, K.; Haberkorn, U.; Morgenstern, A. 213Bi-DOTATOC Receptor-Targeted Alpha-Radionuclide Therapy Induces Remission in Neuroendocrine Tumours Refractory to Beta Radiation: A First-in-Human Experience. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 41, 2106–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J.; Kennel, S.J.; Stuckey, A.; Osborne, D.; Wall, J.; Rondinone, A.J.; Standaert, R.F.; Mirzadeh, S. LaPO4 Nanoparticles Doped with Actinium-225 That Partially Sequester Daughter Radionuclides. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011, 22, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, D.N.; Hantgan, R.; Budzevich, M.M.; Kock, N.D.; Morse, D.L.; Batista, I.; Mintz, A.; Li, K.C.; Wadas, T.J. Preliminary Therapy Evaluation of225 Ac-DOTA-c(RGDyK) Demonstrates That Cerenkov Radiation Derived from225 Ac Daughter Decay Can Be Detected by Optical Imaging for In Vivo Tumor Visualization. Theranostics 2016, 6, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; Roeske, J.C.; McDevitt, M.R.; Palm, S.; Allen, B.J.; Fisher, D.R.; Brill, A.B.; Song, H.; Howell, R.W.; Akabani, G. MIRD Pamphlet No. 22 (Abridged): Radiobiology and Dosimetry of α-Particle Emitters for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; F. Hobbs, R.; Song, H. Modelling and Dosimetry for Alpha-Particle Therapy. Curr. Radiopharm. 2011, 4, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouin, N.; Lindegren, S.; Jensen, H.; Albertsson, P.; Bäck, T. Quantification of Activity by Alpha-Camera Imaging and Small-Scale Dosimetry within Ovarian Carcinoma Micrometastases Treated with Targeted Alpha Therapy. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging Off. Publ. Ital. Assoc. Nucl. Med. AIMN Int. Assoc. Radiopharmacol. IAR Sect. Soc. Of 2012, 56, 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.W.; Gregory, S.J.; Fuller, E.S.; Barrett, H.H.; Bradford Barber, H.; Furenlid, L.R. The iQID Camera: An Ionizing-Radiation Quantum Imaging Detector. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2014, 767, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.W.; Frost, S.H.L.; Frayo, S.L.; Kenoyer, A.L.; Santos, E.; Jones, J.C.; Green, D.J.; Hamlin, D.K.; Wilbur, D.S.; Fisher, D.R.; et al. Quantitative Single-particle Digital Autoradiography with α -particle Emitters for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy Using the iQID Camera. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 4094–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Jaggi, J.; Kappel, B.J.; McDevitt, M.R.; Sgouros, G.; Flombaum, C.D.; Cabassa, C.; Scheinberg, D.A. Efforts to Control the Errant Products of a Targeted In Vivo Generator. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 4888–4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garmestani, K.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wong, K.; Park, C.W.; Pastan, I.; Carrasquillo, J.A.; Brechbiel, M.W. Synthesis and Evaluation of a Macrocyclic Bifunctional Chelating Agent for Use with Bismuth Radionuclides. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2001, 28, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorso, L.; Bigot-Corbel, E.; Abadie, J.; Diab, M.; Gouard, S.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Maurel, C.; Chérel, M.; Davodeau, F. Long-Term Toxicity of 213Bi-Labelled BSA in Mice. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0151330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimeček, J.; Hermann, P.; Seidl, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Wester, H.-J.; Notni, J. Efficient Formation of Inert Bi-213 Chelates by Tetraphosphorus Acid Analogues of DOTA: Towards Improved Alpha-Therapeutics. EJNMMI Res. 2018, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, B.V.; Matazova, E.V.; Mitrofanov, A.A.; Aleshin, G.Yu.; Trigub, A.L.; Zubenko, A.D.; Fedorova, O.A.; Fedorov, Yu.V.; Kalmykov, S.N. Novel Pyridine-Containing Azacrownethers for the Chelation of Therapeutic Bismuth Radioisotopes: Complexation Study, Radiolabeling, Serum Stability and Biodistribution. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2018, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, T.L.; McDevitt, M.R.; Mulford, D.A.; Pandit-Taskar, N.; Divgi, C.R.; Panageas, K.S.; Heaney, M.L.; Chanel, S.; Morgenstern, A.; Sgouros, G.; et al. Sequential Cytarabine and α-Particle Immunotherapy with Bismuth-213–Lintuzumab (HuM195) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5303–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.J.; Raja, C.; Rizvi, S.; Li, Y.; Tsui, W.; Graham, P.; Thompson, J.; Reisfeld, R.; Kearsley, J.; Morgenstern, A.; et al. Intralesional Targeted Alpha Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005, 4, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, C.; Graham, P.; Rizvi, S.; Song, E.; Goldsmith, H.; Thompson, J.; Bosserhoff, A.; Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Kearsley, J.; et al. Interim Analysis of Toxicity and Response in Phase 1 Trial of Systemic Targeted Alpha Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.J.; Singla, A.A.; Rizvi, S.M.A.; Graham, P.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Apostolidis, C.; Morgenstern, A. Analysis of Patient Survival in a Phase I Trial of Systemic Targeted α-Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma. Immunotherapy 2011, 3, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autenrieth, M.E.; Seidl, C.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Horn, T.; Kurtz, F.; Feuerecker, B.; D’Alessandria, C.; Pfob, C.; Nekolla, S.; Apostolidis, C.; et al. Treatment of Carcinoma in Situ of the Urinary Bladder with an Alpha-Emitter Immunoconjugate Targeting the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor: A Pilot Study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Królicki, L.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Kunikowska, J.; Koziara, H.; Królicki, B.; Jakuciński, M.; Pawlak, D.; Apostolidis, C.; Mirzadeh, S.; Rola, R.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Targeted Alpha Therapy with 213Bi-DOTA-Substance P in Recurrent Glioblastoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, S.; Humm, J.L.; Rundqvist, R.; Jacobsson, L. Microdosimetry of Astatine-211 Single-Cell Irradiation: Role of Daughter Polonium-211 Diffusion. Med. Phys. 2004, 31, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, K.A.; Moerlein, S.M.; Link, J.M.; Welch, M.J. Hot Atom Chemistry and Radiopharmaceuticals; Playa del Carmen, Maxico, 2012; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zalutsky, M.R.; Zhao, X.G.; Alston, K.L.; Bigner, D. High-Level Production of Alpha-Particle-Emitting (211)At and Preparation of (211)At-Labeled Antibodies for Clinical Use. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2001, 42, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Poty, S.; Francesconi, L.C.; McDevitt, M.R.; Morris, M.J.; Lewis, J.S. α-Emitters for Radiotherapy: From Basic Radiochemistry to Clinical Studies—Part 1. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhead, D.T.; Munson, R.J.; Thacker, J.; Cox, R. Mutation and Inactivation of Cultured Mammalian Cells Exposed to Beams of Accelerated Heavy Ions IV. Biophysical Interpretation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1980, 37, 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanek, J.; Larsson, B.; Weinreich, R. Auger-Electron Spectra of Radionuclides for Therapy and Diagnostics. Acta Oncol. 1996, 35, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zalutsky, M.R. Production, Purification and Availability of 211At: Near Term Steps towards Global Access. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 100–101, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, B.; Soto, J.R.; Castro, J.J. Halogen-like Properties of the Al13 Cluster Mimicking Astatine. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 11549–11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G. Astatine. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2018, 61, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, D.S. Enigmatic Astatine. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 246–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalutsky, M.; Vaidyanathan, G. Astatine-211-Labeled Radiotherapeutics An Emerging Approach to Targeted Alpha-Particle Radiotherapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2000, 6, 1433–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.W.; Makvandi, M.; Xu, K.; Mach, R.H. Rapid Cu-Catalyzed [211 At]Astatination and [125 I]Iodination of Boronic Esters at Room Temperature. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1752–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizuka, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, H.; Washiya, N.; Tatsuta, M.; Sato, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Ishioka, N.; Shirakami, Y.; Ooe, K.; et al. Metabolic Studies of Astatine- and Radioiodine-Labeled Neopentyl Derivatives. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 1100. [Google Scholar]

- Guérard, F.; Gestin, J.-F.; Brechbiel, M.W. Production of [211 At]-Astatinated Radiopharmaceuticals and Applications in Targeted α-Particle Therapy. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2013, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalutsky, M.R.; Narula, A.S. Astatination of Proteins Using an N-Succinimidyl Tri-n-Butylstannyl Benzoate Intermediate. Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. [A] 1988, 39, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekempeneer, Y.; Bäck, T.; Aneheim, E.; Jensen, H.; Puttemans, J.; Xavier, C.; Keyaerts, M.; Palm, S.; Albertsson, P.; Lahoutte, T.; et al. Labeling of Anti-HER2 Nanobodies with Astatine-211: Optimization and the Effect of Different Coupling Reagents on Their in Vivo Behavior. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3524–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidyanathan, G.; Affleck, D.J.; Bigner, D.D.; Zalutsky, M.R. N-Succinimidyl 3-[211At]Astato-4-Guanidinomethylbenzoate: An Acylation Agent for Labeling Internalizing Antibodies with α-Particle Emitting 211At. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2003, 30, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Vaidyanathan, G.; Koumarianou, E.; Kang, C.M.; Zalutsky, M.R. Astatine-211 Labeled Anti-HER2 5F7 Single Domain Antibody Fragment Conjugates: Radiolabeling and Preliminary Evaluation. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2018, 56, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziawer, Ł.; Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Gaweł, D.; Godlewska, M.; Pruszyński, M.; Jastrzębski, J.; Wąs, B.; Bilewicz, A. Trastuzumab-Modified Gold Nanoparticles Labeled with 211At as a Prospective Tool for Local Treatment of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérard, F.; Maingueneau, C.; Liu, L.; Eychenne, R.; Gestin, J.-F.; Montavon, G.; Galland, N. Advances in the Chemistry of Astatine and Implications for the Development of Radiopharmaceuticals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3264–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.G.; Durbin, P.W.; Parrott, M.W. Accumulation of Astatine211 by Thyroid Gland in Man. Exp. Biol. Med. 1954, 86, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.; Cederkrantz, E.; Bäck, T.; Divgi, C.; Elgqvist, J.; Himmelman, J.; Horvath, G.; Jacobsson, L.; Jensen, H.; Lindegren, S.; et al. Intraperitoneal α-Particle Radioimmunotherapy of Ovarian Cancer Patients: Pharmacokinetics and Dosimetry of211 At-MX35 F(Ab′)2 —A Phase I Study. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalutsky, M.R.; Reardon, D.A.; Akabani, G.; Coleman, R.E.; Friedman, A.H.; Friedman, H.S.; McLendon, R.E.; Wong, T.Z.; Bigner, D.D. Clinical Experience with Alpha-Particle Emitting 211At: Treatment of Recurrent Brain Tumor Patients with 211At-Labeled Chimeric Antitenascin Monoclonal Antibody 81C6. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, A.; Qiu, H.; Santos, E.B.; Hamlin, D.K.; Wilbur, D.S.; Storb, R.; Sandmaier, B.M. Addition of Astatine-211-Labeled Anti-CD45 Antibody to TBI as Conditioning for DLA-Identical Marrow Transplantation: A Novel Strategy to Overcome Graft Rejection in a Canine Presensitization Model: “Radioimmunotherapy to Overcome Transfusion-Induced Sensitization. ” Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2021, 27, 476.e1–476.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukon, N.; Higashi, T.; Hosono, M.; Kinuya, S.; Yamada, T.; Yanagida, S.; Namba, M.; Nakamura, Y. Manual on the Proper Use of Meta-[211At] Astato-Benzylguanidine ([211At] MABG) Injections in Clinical Trials for Targeted Alpha Therapy (1st Edition). Ann. Nucl. Med. 2022, 36, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watabe, T.; Kaneda-Nakashima, K.; Ooe, K.; Liu, Y.; Kurimoto, K.; Murai, T.; Shidahara, Y.; Okuma, K.; Takeuchi, M.; Nishide, M.; et al. Extended Single-Dose Toxicity Study of [211At]NaAt in Mice for the First-in-Human Clinical Trial of Targeted Alpha Therapy for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2021, 35, 702–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvassheim, M.; Revheim, M.-E.R.; Stokke, C. Quantitative SPECT/CT Imaging of Lead-212: A Phantom Study. EJNMMI Phys. 2022, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.S.; Stabin, M.G. Exposure Rate Constants and Lead Shielding Values for over 1,100 Radionuclides. Health Phys. 2012, 102, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, E.; Stenberg, V.Y.; Juzeniene, A.; Hjellum, G.E.; Bruland, Ø.S.; Larsen, R.H. Calibration of Sodium Iodide Detectors and Reentrant Ionization Chambers for 212Pb Activity in Different Geometries by HPGe Activity Determined Samples. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2020, 166, 109362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radchenko, V.; Morgenstern, A.; Jalilian, A.R.; Ramogida, C.F.; Cutler, C.; Duchemin, C.; Hoehr, C.; Haddad, F.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Gausemel, H.; et al. Production and Supply of α-Particle–Emitting Radionuclides for Targeted α-Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, B.L.; Robertson, A.K.H.; Fu, W.; Yang, H.; Hoehr, C.; Ramogida, C.F.; Schaffer, P. Production, Purification, and Radiolabeling of the 203Pb/212Pb Theranostic Pair. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.J.B.; Wilson, J.; Schultz, M.K.; Andersson, J.D.; Wuest, F. High-Yield Cyclotron Production of 203Pb Using a Sealed 205Tl Solid Target. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2023, 116–117, 108314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wilson, J.J.; Orvig, C.; Li, Y.; Wilbur, D.S.; Ramogida, C.F.; Radchenko, V.; Schaffer, P. Harnessing α -Emitting Radionuclides for Therapy: Radiolabeling Method Review. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzadeh, S.; Kumar, K.; Gansow, O.A. The Chemical Fate of212 Bi-DOTA Formed by β- Decay of212 Pb(DOTA)2- ***. ract 1993, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azure, M.T.; Archer, R.D.; Sastry, K.S.; Rao, D.V.; Howell, R.W. Biological Effect of Lead-212 Localized in the Nucleus of Mammalian Cells: Role of Recoil Energy in the Radiotoxicity of Internal Alpha-Particle Emitters. Radiat. Res. 1994, 140, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Baumhover, N.J.; Liu, D.; Cagle, B.S.; Boschetti, F.; Paulin, G.; Lee, D.; Dai, Z.; Obot, E.R.; Marks, B.M.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of a Lead Specific Chelator (PSC) Conjugated to Radiopeptides for 203Pb and 212Pb-Based Theranostics. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, K.E.; Milenic, D.E.; Brechbiel, M.W. Methodology for Labeling Proteins and Peptides with Lead-212 (212Pb). Nucl. Med. Biol. 2013, 40, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, R.; Torgue, J.; Shen, S.; Fisher, D.R.; Banaga, E.; Bunch, P.; Morgan, D.; Fan, J.; Straughn, J.M. Dose Escalation and Dosimetry of First-in-Human α Radioimmunotherapy with212 Pb-TCMC-Trastuzumab. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpassand, E.S.; Tworowska, I.; Esfandiari, R.; Torgue, J.; Hurt, J.; Shafie, A.; Núñez, R. Targeted α -Emitter Therapy with212 Pb-DOTAMTATE for the Treatment of Metastatic SSTR-Expressing Neuroendocrine Tumors: First-in-Humans Dose-Escalation Clinical Trial. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, D.; Lee, D.; Cheng, Y.; Baumhover, N.J.; Marks, B.M.; Sagastume, E.A.; Ballas, Z.K.; Johnson, F.L.; Morris, Z.S.; et al. Targeted Alpha-Particle Radiotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Induces Cooperative Inhibition on Tumor Growth of Malignant Melanoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, B.J.; Goozee, G.; Sarkar, S.; Beyer, G.; Morel, C.; Byrne, A.P. Production of Terbium-152 by Heavy Ion Reactions and Proton Induced Spallation. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2001, 54, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, G.J.; Čomor, J.J.; Daković, M.; Soloviev, D.; Tamburella, C.; Hagebø, E.; Allan, B.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Zaitseva, N.G. Production Routes of the Alpha Emitting149 Tb for Medical Application. Radiochim. Acta 2002, 90, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Zhernosekov, K.; Köster, U.; Johnston, K.; Dorrer, H.; Hohn, A.; Van Der Walt, N.T.; Türler, A.; Schibli, R. A Unique Matched Quadruplet of Terbium Radioisotopes for PET and SPECT and for α- and β− -Radionuclide Therapy: An In Vivo Proof-of-Concept Study with a New Receptor-Targeted Folate Derivative. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 53, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.K. Advancements in Cancer Therapy with Alpha-Emitters: A Review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2001, 51, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerard, F.; Barbet, J.; Chatal, J.F.; Kraeber-Bodere, F.; Cherel, M.; Haddad, F. Which Radionuclide, Carrier Molecule and Clinical Indication for Alpha-Immunotherapy? Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging Off. Publ. Ital. Assoc. Nucl. Med. AIMN Int. Assoc. Radiopharmacol. IAR Sect. Soc. Of 2015, 59, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Brechbiel, M.W. Targeted α-Therapy: Past, Present, Future? Dalton Trans. 2007, 4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokke, C.; Kvassheim, M.; Blakkisrud, J. Radionuclides for Targeted Therapy: Physical Properties. Mol. Basel Switz. 2022, 27, 5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.; Reber, J.; Haller, S.; Dorrer, H.; Köster, U.; Johnston, K.; Zhernosekov, K.; Türler, A.; Schibli, R. Folate Receptor Targeted Alpha-Therapy Using Terbium-149. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, G.F.; Vermeulen, C.; Szelecsényi, F.; Kovács, Z.; Hohn, A.; Van Der Meulen, N.P.; Schibli, R.; Van Der Walt, T.N. Cross Sections of Proton-Induced Reactions on 152Gd, 155Gd and 159Tb with Emphasis on the Production of Selected Tb Radionuclides. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2014, 319, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, N.G.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Maslov, O.D.; Molokanova, L.G.; Starodub, G.Ya.; Shishkin, S.V.; Shishkina, T.V.; Beyer, G.J. Terbium-149 for Nuclear Medicine. The Production of 149Tb via Heavy Ions Induced Nuclear Reactions. Czechoslov. J. Phys. 2003, 53, A455–A458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, M.; Lahiri, S.; Tomar, B.S. Investigation on the Production and Isolation of149,150,151 Tb from12 C Irradiated Natural Praseodymium Target. Radiochim. Acta 2011, 99, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, S.N.; Beyer, G.J.; Zaitseva, N.G.; Maslov, O.D.; Molokanova, L.G.; Starodub, G.Ya.; Shishkin, S.V.; Shishkina, T.V. [No Title Found]. Radiochemistry 2002, 44, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaim, S.M.; Scholten, B.; Neumaier, B. New Developments in the Production of Theranostic Pairs of Radionuclides. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 318, 1493–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, M. New Measurement of Cross Sections of Evaporation Residues from the Nat Pr + 12 C Reaction: A Comparative Study on the Production of 149 Tb. Phys. Rev. C 2011, 84, 044615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, G.-J.; Miederer, M.; Vranješ-Đurić, S.; Čomor, J.J.; Künzi, G.; Hartley, O.; Senekowitsch-Schmidtke, R.; Soloviev, D.; Buchegger, F. ; and the ISOLDE Collaboration Targeted Alpha Therapy in Vivo: Direct Evidence for Single Cancer Cell Kill Using 149Tb-Rituximab. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2004, 31, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guseva, L.I. Radioisotope Generators of Short-Lived α-Emitting Radionuclides Promising for Use in Nuclear Medicine. Radiochemistry 2014, 56, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Vermeulen, C.; Köster, U.; Johnston, K.; Türler, A.; Schibli, R.; Van Der Meulen, N.P. Alpha-PET with Terbium-149: Evidence and Perspectives for Radiotheragnostics. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2017, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagryadskii, V.A.; Latushkin, S.T.; Malamut, T.Yu.; Novikov, V.I.; Ogloblin, A.A.; Unezhev, V.N.; Chuvilin, D.Yu. Measurement of Terbium Isotopes Yield in Irradiation of 151Eu Targets by 3He Nuclei. At. Energy 2017, 123, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva, A.N.; Aliev, R.A.; Unezhev, V.N.; Zagryadskiy, V.A.; Latushkin, S.T.; Aksenov, N.V.; Gustova, N.S.; Voronuk, M.G.; Starodub, G.Ya.; Ogloblin, A.A. Cross Section Measurements of 151Eu(3He,5n) Reaction: New Opportunities for Medical Alpha Emitter 149Tb Production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, M.G.; Radchenko, V.; Wilbur, D.S. Radiochemical Aspects of Alpha Emitting Radionuclides for Medical Application. Radiochim. Acta 2019, 107, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ji, M.; Fisher, D.R.; Wai, C.M. Ionizable Calixarene-Crown Ethers with High Selectivity for Radium over Light Alkaline Earth Metal Ions. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 5449–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou, D.S.; Thiele, N.A.; Gutsche, N.T.; Villmer, A.; Zhang, H.; Woods, J.J.; Baidoo, K.E.; Escorcia, F.E.; Wilson, J.J.; Thorek, D.L.J. Towards the Stable Chelation of Radium for Biomedical Applications with an 18-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 3733–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Gawęda, W.; Żelechowska-Matysiak, K.; Wawrowicz, K.; Bilewicz, A. Nanoparticles in Targeted Alpha Therapy. Nanomater. Basel Switz. 2020, 10, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoff, A.; Czerwińska, M.; Walczak, R.; Karczmarczyk, U.; Tomczyk, K.; Brzóska, K.; Fracasso, G.; Garnuszek, P.; Mikołajczak, R.; Kruszewski, M. Design and Evaluation of 223Ra-Labeled and Anti-PSMA Targeted NaA Nanozeolites for Prostate Cancer Therapy-Part II. Toxicity, Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissig, F.; Hübner, R.; Steinbach, J.; Pietzsch, H.-J.; Mamat, C. Facile Preparation of Radium-Doped, Functionalized Nanoparticles as Carriers for Targeted Alpha Therapy. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissig, F.; Zarschler, K.; Hübner, R.; Pietzsch, H.; Kopka, K.; Mamat, C. Sub-10 Nm Radiolabeled Barium Sulfate Nanoparticles as Carriers for Theranostic Applications and Targeted Alpha Therapy. ChemistryOpen 2020, 9, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, W.; Pruszyński, M.; Cędrowska, E.; Rodak, M.; Majkowska-Pilip, A.; Gaweł, D.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Morgenstern, A.; Bilewicz, A. Trastuzumab Modified Barium Ferrite Magnetic Nanoparticles Labeled with Radium-223: A New Potential Radiobioconjugate for Alpha Radioimmunotherapy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchánková, P.; Kukleva, E.; Nykl, E.; Nykl, P.; Sakmár, M.; Vlk, M.; Kozempel, J. Hydroxyapatite and Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Radiolabelling and In Vitro Stability of Prospective Theranostic Nanocarriers for 223Ra and 99mTc. Nanomater. Basel Switz. 2020, 10, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.S.; Simms, M.E.; Bryantsev, V.S.; Benny, P.D.; Griswold, J.R.; Delmau, L.H.; Thiele, N.A. Elucidating the Coordination Chemistry of the Radium Ion for Targeted Alpha Therapy. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 9938–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.J.; Corey, E.; Guise, T.A.; Gulley, J.L.; Kevin Kelly, W.; Quinn, D.I.; Scholz, A.; Sgouros, G. Radium-223 Mechanism of Action: Implications for Use in Treatment Combinations. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; Seke, M.; et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Parker, C.; Saad, F.; Miller, K.; Tombal, B.; Ng, Q.S.; Boegemann, M.; Matveev, V.; Piulats, J.M.; Zucca, L.E.; et al. Addition of Radium-223 to Abiraterone Acetate and Prednisone or Prednisolone in Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Bone Metastases (ERA 223): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washiyama, K.; Amano, R.; Sasaki, J.; Kinuya, S.; Tonami, N.; Shiokawa, Y.; Mitsugashira, T. 227Th-EDTMP: A Potential Therapeutic Agent for Bone Metastasis. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2004, 31, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, O.; Bates, A.T.; Cunningham, D.; Hindorf, C.; Larsson, E.; Cleton, A.; Pinkert, J.; Huang, F.; Bladt, F.; Hennekes, H.; et al. 227Th-Labeled Anti-CD22 Antibody (BAY 1862864) in Relapsed/Refractory CD22-Positive Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A First-in-Human, Phase I Study. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2021, 36, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzina, M.; Mamis, E.; Saule, L.; Pajuste, E.; Kalnina, M.; Cocolios, T.; Talip, Z.; Stora, T. Deliverable 5.1 - Questionnaire on Industrial and Clinical Key Players and Needs. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Appendix A. SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

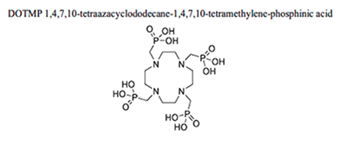

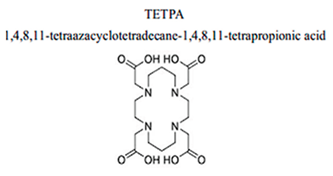

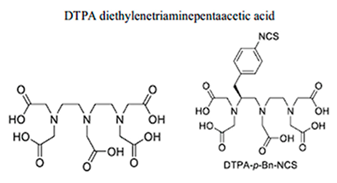

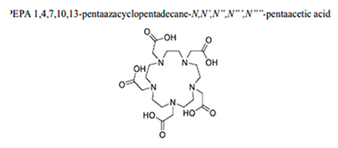

| Chelate (and corresponding tested bifunctional analogues | Donor Set (CN#) | Grade | Radiolabelling Conditions & RCY | Ref. |

|

N4O4 CN = 8 |

Green -orange | 0.02 M ligand, NH4Ac pH 6, 37 °C, 2 h, RCY = 99% |

[1] |

|

N4O4 CN = 8 |

Red | 0.02 M ligand, NH4Ac pH 6, 37 °C, 2 h, RCY = 0% |

[2] |

|

N4O4 CN = 8 |

Red | 0.02 M ligand, NH4Ac pH 6, 37 °C, 2 h, RCY = 78% |

[2] |

|

N4O4 CN = 8 |

Red | 0.02 M ligand, NH4Ac pH 6, 37 °C, 2 h, RCY = 0% |

[2] |

|

N3O5 CN = 8 |

Red | 0.02 M ligand, NH4Ac pH 6, 37 °C, 2 h, RCY = 0% |

[2] |

|

N5O5 CN = 10 |

Red | 0.02 M ligand, NH4OAc pH 5.8, 40 °C, 30 min, RCY = 80% |

[3] |

|

N6O6 CN = 12 |

Orange | 0.01 M ligand, NH4OAc pH 5.8, 40 °C, 30 min, RCY > 95% or > 98% after 2 h |

[3,4] |

|

N3O5 CN = 8 |

Red | 0.01 M ligand, 0.02 NH4OAc pH 5.8, 0.03 40 °C, 0.04 30 min, 0.05 RCY > 95% |

[3,5] |

|

N2O4 CN = 6 |

Red | 0.01 M ligand, 0.02 NH4OAc pH 5, 0.03 40 °C, 30 min, 0.04 RCY = 80-90% |

[5] |

| Preclinical model | Radiopharmaceutical | Activity/no of cycles | Main findings | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac-225 | AR42J cells | [225Ac]Ac -DOTA-CCK-66 | 37 kBq / 1 cycle |

Substantial increase in mean survival of AR42J tumour-bearing mice upon treat- ment with the minigastrin derivative |

[6] |

| Ac-225 | Human ovarian carcinoma HER2-positive(SKOV-3 cell line) | [225Ac]Ac -H4py4pa |

10.1±0.7 kBq / 1 cycle | Stability study, in vitro and biodistribution |

[7] |

| Ac-225 | Human breast cancer cell lines SUM-225 and MDA-MB-231 | [225Ac]Ac -DOTA-trastuzumab | 0.37 kBq / 0.74 Bq / 1.48 Bq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution (comp. with In-111-DTPA-trastuzumab), optical imaging and therapy study. |

[8] |

| Ac-225 | Human HER2- positive cell lines SKOV-3 (ovarian cancer) and MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer) | [225Ac]Ac- DOTA-Nb (nanobod) | 30.2 ± 1.4 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro and biodistribution In vitro, therapy study, dosimetry and toxicity |

[9] |

| Ac-225 | Human HER2- positive cell lines SKOV-3 (ovarian cancer) and MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer) | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-Nb (nanobod) | 81.67 ± 28.87 kBq / 3 cycles | In vitro and biodistribution In vitro, therapy study, dosimetry and toxicity |

[10] |

| Ac-225 | U87mg human glioblastoma tumour cells |

[225Ac]Ac-DOTA-c(RGDyK) | 10 kBq / 20 kBq / 40 kBq/ 1 cycle | Biodistribution, optical imaging and therapy study | [11] |

| Ac-225 | Human glioblastoma cell line U251 |

[225Ac]Ac-Pep-1L | 40 kBq / 1 cycle | Bioluminescent imaging, therapy study (comparison with Cu-64-PepL1) | [12] |

| Ac-225 | NT2.5 mammary tumour cell line |

[225Ac]Ac-DOTA-anti-PD-L1-BC | 15 KBq / 1 cycle | Biodistribution (comparison with In-111-DTPA anti-PD-L1-BC), imaging, dosimetry |

[13] |

| Ac-225 | Human prostatic carcinoma cells LNCaP | [225Ac,Ac-(macropa)]+ | 26 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro and biodistribution | [14] |

| Ac-225 | [225Ac,Ac-(macropa)]+ | 37 KBq / 74 KBq / 148 KBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution, therapy study and dosimetry | [15] | |

| Ac-225 | Human pancreatic cell line BxPC3 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA Human antibody 5B1 | 18.5 kBq / 1 cycle | Biodistribution, luminescence imaging, therapy studies (pre-targeting or conventional) and toxicity | [16];[17] |

| Ac-225 | Mammary carcinoma cell lines MFM-223 and BT-474 | [225Ac]Ac-hu11B6H435A | 11.1 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution and therapeutic study | [18] |

| Ac-225 | Triple-negative breast cancer model SUM149T | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-cixutumumab |

8.32 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, imaging, biodistribution (comp.with In-111-cixutumumab) and efficacy study |

[19] |

| Ac-225 | Malignant melanoma cell line B16F10 | [225Ac,Ac-octapa]-[225Ac,At-(CHXoctapa)]−; [225Ac,Ac(DOTA-CycMSH)] | 12–20 kBq / 1 cycle | Stability study and biodistribution | [20] |

| Ac-225 | Human cutaneous melanoma cells A375 andA375/MC1R and human uveal melanoma cells MEL270 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-MC1RL | 148 kBq (±10%) / 1 cycle | In vitro, pharmacokinetic, biodistribution, therapy study and dosimetry |

[21] |

| Ac-225 | Human cutaneous melanoma cells A375 and A375/MC1R | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-Ahx-MC1RL (225Ac-Ahx); [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-di-d-Glu-MC1RL (225Ac-di-d-Glu) |

94.84 kBq ±7.11% / 56.52 kBq ±8.2 / 1 cycle | Biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, therapy study and toxicity | [22] |

| Ac-225 | Malignant melanoma cell line B16F10 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-Anti-VLA-4 | 14.8 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution, imaging dosimetry and therapeutic efficacy | [23] |

| Ac-225 | Human embryonic kidney epithelial cells HEK-293T and HEK-293T-Hx16 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA- SC16.56 (radioimmunoconjugate- Humanised site- specific antibodiesN149) |

18.9 – 55.5 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution and efficacy study (comparison with Lu-177-DOTA-MMA) | [24] |

| Ac-225 | Colorectal cancer (SW1222), breast cancer (BT-474) or neuroblastoma (IMR32) | [225Ac]Ac-Proteus-DOTA (Humanised A33 and C825 (huA33-C825) | 0, 9.25, 18.5, 37, 74, 148, or 296 kBq / 1 cycle | Biodistribution (comparison with 111In-Pr, imaging) therapy study and toxicity(Pretargeted radioimmunotherapy) | [25] |

| Ac-225 | Human pancreatic cell lines PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 | [225Ac]Ac-FAPI-04 | 34 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution and efficacy study | [26] |

| Ac-225 | Human squamous carcinoma A431 cell line | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-PP-F11N | 45 kBq or 60 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution and therapy study | [27] |

| Ac-225 | Hepatoblastoma cell line HepG2 and squamous carcinoma A431 (GPC3+) | [225Ac]Ac-Macropa-GC33 | 9.25 kBq or 18.5 kBq / 1 cycle | In vitro, biodistribution, therapy study and toxicity | [28] |

| Bi-213 | Multiple myeloma | [213Bi]Bi-anti CD138 | 3.7 MBq (single dose) | Increased median survival to 80 days, compared with 37 days for the untreated control group |

[29];[30] |

| Bi-213 | Bladder carcinoma | [213Bi]Bi-anti-EGFR-mAb | 0.94 MBq (fractioned dose) |

Overall survival of 141.5 days on average, in contrast with 65.4 and 57.6 days for the two control groups | [31] |

| Bi-213 | AR42J tumour- bearing mice; H69 human small-cell lung carcinoma; CA20948 rat pancreatic tumour | [213Bi]Bi-DOTATATE | 2–4 MBq/0.3 nmol/ 200 μL |

Significant tumour burden reduction and improved overall survival | [32];[33] |

| At-211 | syngeneic immunocompetent rat model | [211At]At-BR96 | 2.5 or 5 MBq | Possibility of treating small, solid colon carcinoma tumours with tolerable toxicity | [34];[35] |

| At-211 | U87MG cells Nude mice bearing xenograft tumours |

[211At]At-iRGD- C6-lys-C6-DA7R | 180, 370 and 740 kBq | Inhibition of cell viability, induced cell apoptosis, arrested the cell cycle in the G2/M phase, and increased intracellular ROS levels in a dose-dependent manner; inhibition of tumour growth and prolongation of the survival of mice | [36] |

| At-211 | T98G glioma cell line | [211At]At-Rh[16aneS4]- SP5–11 | 75–1200 kBq/mL | Cytotoxic effect on glioma cells | [37];[32] |

| At-211 | DBTRG-05MG glioma cell line, female BDIX rats with intracranial glioblastomas |

2-[211At]At-Phenylalanine 4- [211At]At-Phenylalanine |

1000 kBq (1 or 2 cycles) | Enhanced survival time of rats with intracranial glioblastomas | [38]; [39] |

| At-211 | Athymic mice bearing subcutaneous D-54 MG human glioma xenografts | [211At]At-ch81C6 | 74 kBq | Calculation of human radiation dose for i.v. and intrathecal administration | [40] |

| At-211 | HNSCC-Bearing female nude mice (balb/c nu/nu) | [211At]At-U36 (Chimeric mAb) |

200 kBq | Specific binding to the glycoprotein and efficient therapeutic response | [41] |

| At-211 | HL-60 and CI-1 cells | [211At]At -rituximab; [211At]At -gemtuzumab; [211At]At gemtuzumab ozogamicin. |

0.03 to 9.29 kBq (to 106 cells) | The affinity and specificity of the respective epitopes are not compromised | [42] |

| At-211 | leukemic SJL/J mice | [211At]At-30F11 (anti-murine CD45; mAb) |

444, 740 and 888 kBq | Improvements in overall survival when combined with bone marrow transplantation in a disseminated model of murine leukaemia with minimal renal toxicity | [43] |

| At-211 | Female BALB/c mice | [211At]At-30F11- ADTM | 74, 370, 740 and 1850 kBq |

more effective at myelosuppression than 213Bi, no significant non hematopoietic toxicity | [44] |

| At-211 | Human ML xenograft model in male hymic BALB/c nude mice | [211At]At -CXCR4 (mAb) | 320 kBq | clearance from blood and the tumour uptake matched the physical half-life of 211At; tumour uptake was relatively low | [45] |

| At-211 | Female and male NOD-Rag1null IL2rɣnull/J (NRG) mice | [211At]At-B10 (conjugated anti-CD123; mAb) |

185, 370, 740 or 1480 kBq |

decreased tumour burden and significantly prolonged dose-dependent survival | [46] |

| At-211 | Female athymic nude mice (s.c. injected Ramos cells) | [211At]At-1F5- B10 | Up to 1776 kBq | highly efficacious in minimal residual disease, no significant renal or hepatic toxicity | [47] |

| At-211 | Normal Kunming (KM) mice, BALB/c nude mice (s.c. injected A549 cells) | [211At]At -SPC-octreotide | 2294 kBq | more lethal effect than control groups (PBS, octreotide and free 211At), a possible treatment option for NSCLC | [48] |

| At-211 | Human melanoma- xenografted nude mice | [211At]At-MTB (methylene blue) |

3,5 MBq | highly effective, no adverse effects of TAT | [49] |

| At-211 | Female and male NOD.Cg Rag1tm1Mom Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NRG) mice | [211At]At-OKT10- B10 | 277 to 1665 kBq | potential to eliminate residual MM cell clones in low-disease-burden settings with minimal toxicity | [50] |

| At-211 | KaLwRij C57/BL6 mice (i.v. injected 5T33 cells) | [211At]At-9E7.4 | 370, 555, 740 or 1110 kBq |

the activity of 740 kBq showed 65% overall survival 150 days after the treatment with no evident sign of toxicity in MDR of multiple myeloma. | [51] |

| At-211 | NB-EBC1x tumour- bearing mouse model (female SCID CB17 mice) | [211At]At-parthanatine (PTT) | 185 kBq | maximum tolerated dose (MTD 36 MBq/kg/fraction x4), complete tumour response was observed in 81.8% with reversible haematological and marrow toxicity | [52] |

| At-211 | Male ICR mice (6 weeks old) | [211At]At-MABG (astatobenzylguanidine) |

185 kBq (biodistribution) 1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4 MBq (body weigth studies) |

the MTD was 3.3 MBq for ICR mice. | [53];[54] |

| At-211 | female BALB/c nude mice s.c. inoculated with NIH: OVCAR-3 cells |

[211At]At-farletuzumab | 700 kBq | the tumour-free fraction (TFF) was shown to be 91% for i.p. administered 211At-farletuzumab | [55] |

| At-211 | nude Balb/c nu/nu mice (i.p. inoculated with OVCAR-3 cells) | [211At]At-MX35 (mAb) |

800 kBq and 3× ∼267 kBq ∼400 kBq and 3× ∼133 kBq ∼50 kBq or 3× ∼17 kBq |

no advantage in the therapeutic efficacy of a fractionated regimen compared with a single administration and lower side effects | [56] |

| At-211 | nude Balb/c nu/nu mice (i.p. inoculated with OVCAR-3 cells) | [211At]At-MX35 (mAb) |

350 - 540 kBq | micrometastatic growth of an ovarian cancer cell line was reduced with no considerable signs of toxicity | [57] |

| At-211 | nude Balb/c nu/nu mice (i.p. inoculated with SKOV-3 cells) | [211At]At-trastuzumab (mAb) |

100 – 800 kBq | statistically significant dose-response relationship for a single i.p. injection, a combination of 500 μg trastuzumab and 400 kBq 211At-trastuzumab had the greatest effect | [58] |

| At-211 | s.c. and PMGC (peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer) xenograft mice | [211At]At-trastuzumab (mAb) |

100 and 1000 kBq | locoregionally administered [211At]At-trastuzumab significantly prolonged the survival time |

[59] |

| At-211 | Female nude BALB/c (nu/nu) mice (s.c. inoculated with SKOV-3 cells) | N-succinimidyl- 3-[211At]At-5- guanidinomethyl benzoate |

700 kBq | fast and high accumulation in a HER2+ tumour mouse model with a low non- target organ uptake | [60] |

| At-211 | female athymic mice (s.c. inoculation of 9BT474 xenografts) | Iso-[211At]At SAGMB-5F7 Iso-[211At]At SAGMB- VHH_2001 |

130 - 175 kBq | significant tumour growth delay and survival prolongation in a murine model of HER2-expressing breast cancer with no apparent normal- tissue toxicities | [61] |

| At-211 | C.B17/Icr-scid mice (s.c. implantation of MDA-361/DYT2 cells) |

[211At]At-SAPS C6.5 (diabody); [211At]At-SAPS T84.66 (diabody; [211At]At-SAPS (anti-MISIIR GM17 diabody) |

740, 1110 or 1665 kBq | single i.v. treatment resulted in dose- dependent delays in tumour growth | [62] |

| At-211 | Athymicmice bearing PSMA+ PC3, PIP and PSMA- PC3 flu flank xenografts |

(2S)-2-(3-(1-carboxy-5-(4-[211At]At astatobenzamido)pentyl)ureido)-pentanedioic acid | 200 kBq, 740 kBq | specific PC cell kill in vitro and in vivo after systemic administration and late nephrotoxicity | [63] |

| At-211 | LNCaP xenograft mice, normal ICR mice | [211At]At-PSMA1; [211At]At-PSMA5; [211At]At-PSMA6 |

110 – 400 kBq | [211At]At-PSMA5 exhibited excellent tumour growth suppression in xenograft models of prostate cancer, with minimal side effects. | [64] |

| At-211 | Male nude BALB/c nu/nu mice (s.c. inoculated with PC3- PSCA tumour cells) | [211At]At-A11 (anti-PSCA mini body) |

260 ± 20 kBq, 800 kBq and 1500 kBq |

growth inhibition on both macro tumours and intratibial micro tumours and multiple fractions resulted in radiotoxicity | [65] |

| At-211 | Male nude BALB/c nu/nu mice (s.c. inoculated with PC-3 cells) | [211At]At-AB-3 | 85 kBq | poor in vivo stability | [66] |

| At-211 | NIS-6 cells | [211At]At-astatide | 50-100 kBq | uptake is shown to be NIS-dependent | [67];[68] |

| At-211 | NMRI-nu/nu nude mice (s.c. inoculated with xenografts of a human papillary thyroid carcinoma cell line, K1) | [211At]At-astatide | 100, 500 and 1000 kBq | high tumouricidal potential in NIS gene–transfected tumours without major side effects | [69] |

| At-211 | Healthy male Balb/C nu/nu mice | [211At]At-AuNP (gold nanoparticles) |

900 kBq | high in vitro and in vivo stability | [70] |

| At-211 | Male nude BALB/c- nu-nu (s.c. inoculated PANC-1 cells) |

[211At]At-FAPI-1; [211At]At- FAPI-5 |

540 – 970 kBq | higher tumour retention of [211At]At- FAPI(s) compared with [131I]I -FAPI(s) | [71] |

| Pb-212 | Model A - Female naïve CD-1Elite mice; Model B – Female Athymic mice bearing AR42J tumour Xenografts |

[212Pb]Pb-PSC-PEG-T | Model A- Single injection of 74 kBq; Model B- Single injection of 3.7 MBq |

Model A - fast clearance from blood circulation, cleared through the kidneys. Model B - prolonged accumulation in tumour and minimal retention in kidneys (0.9%ID in tumour; 1%ID in kidneys) |

[72] |

| Pb-212 | Female athymic-NCR- nude mice with SK-OV-3 tumour xenografts: Model A - tumour volume 15 mm3 Model B – tumour volume 146 mm3 |

[212Pb]Pb-DOTA-AE1 | Model A - Single injection of 740 kBq; Model B – Single injection of 925 kBq |

Model A – the rate of tumour growth was inhibited in the period after the [212Pb]Pb-DOTA-AE1 therapy; Model B - [212Pb]Pb-DOTA-AE1 did not provide effective therapy for large established tumours. |

[73] |

| Pb-212 | Male non-obese, diabetic/Shi-scid/IL- 2rgnull (NSG) mice: Model A - bearing PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumour xenografts. Tumour volume 60–100 mm3. Model B - PSMA(+) micrometastatic model, mice were injected intravenously with 1 x 106 PC3-ML-Luc-PSMA cells |

[212Pb]Pb-L2 |

Model A - Single dose of 3.7 MBq Model B - 0, 0.7, 1.5, or 3.7 MBq |

Model A - A single administration of 1.5 or 3.7 MBq showed significant tumour growth delay only in PSMA(+) Model B - the median survival time for the mice administered [212Pb]Pb-L2 (3.7 MBq) was 58 days, demonstrating moderate but significant improvement. |

[74] |

| Pb-212 | Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu mice bearing C4-2 tumour xenografts. Tumour volume 250-1000 mm3 |

[212Pb]Pb-NG001; [212Pb]Pb-PSMA-617 |

Single dose of 10-56 kBq of [212Pb]Pb-NG001; A single dose of 79 kBq of [212Pb]Pb-PSMA-617 |

The uptake values (%ID/g) for tumour and kidneys at 2-hour post-injection were 17.61±6.76 and 21.07±10.33 for [212Pb]Pb-NG001 and 17.93±2.90 and 52.82±26.62 for [212Pb]Pb-PSMA-617 |

[75] |

| Pb-212 | SCID mice bearing PC3 tumour xenografts |

[212Pb]Pb-RM2 |

Single dose of 1.85 MBq or 3.7 MBq |

Both [212Pb]Pb-RM2 treatment groups (1.85 MBq or 3.7MBq) demonstrated initial tumour control for 4-5 weeks post-treatment. 18 days pi, tumour regression was observed in the 3.7 MBq group (maximum per cent change of -49.3%) 40 days pi, tumour regrowth was observed in the 3.7 MBq group (+91.6% change from predose) |

[76] |

| Tb-149 | SCID mouse model of leukaemia | [149Tb]Tb-rituximab |

5.5MBq labelled antibody conjugate (1.11GBq/mg) 2 days after an intravenous graft of 5106 Daudi cells | Tumour-free survival for >120 days in 89% of treated animals | [77] |

| Tb-149 | Tumour-bearing mice | [149Tb]Tb-cm09 (DOTA-folate conjugate) |

Group A: saline only Group B: 2.2 MBq; Group C: 3.0 MBq; |

A significant tumour growth delay was found in treated animals resulting in an increased average survival time of mice which received 149Tb-cm09 (B: 30.5 d; C: 43 d) compared to untreated controls (A: 21 d). | [78] |

| Ra-223 | Balb/c | [223Ra]RaCl2 |

450 kBq/kg of 223Ra | High activity concentration in bone; High retention in the kidney and spleen among OARs |

[79] |

| Ra-223 |

Balb/c |

[223Ra]RaCl2 |

1250, 2500, 3750 kBq/kg | Minimal to moderate depletion of osteocytes and osteoblasts | [80] |

| Ra-223 | Intratibial LNCaP or LuCaP 58 | [223Ra]RaCl2 | 300 kBq/kg – 2 cycles |

Inhibition of tumour cellular growth | [81] |

| Th-227 | Human lymphoma Raji | [22tTh]Th -Rituximab | 50, 200, 1000 kBq/kg | Complete regression in 60% of mice treated with 200 kBq/kg | [82] |

| Th-227 | HER2-overexpressing subcutaneous SKOV-3 or SKBR-3 | [22tTh]Th-trastuzumab | 1000 kBq/kg - 1 cycle; 250 kBq/kg - 4 cycles |

Survival with a tumour diameter of less than 16 mm was prolonged | [83] |

| Th-227 | subcutaneous xenograft mouse model using HL- 60 cells at a single dose regimen | [22tTh]Th-CD33-TTC | 50, 150, or 300 kBq/kg – 1 cycle a second injection of 150 kBq/kg for some animals | Dose- dependent significant survival benefit | [84] |

| Th-227 | NCI-H716, SNU- 16, and MFM- 223 |

[22tTh]Th-FGFR2-TTC | 500 kBq/kg | significant inhibition of tumour growth at a dose of 500 kBq/kg | [85] |

| NCT Number | Radio | Radiopharmaceutical | Study Title | Study Status | Conditions | Sponsor | Phases |

| NCT06939036 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-SSO110 | Study of [225Ac]Ac-SSO110 in Subjects With ES-SCLC or MCC (SANTANA-225 ) | Ongoing, estimated completion 2026-12 | Small Cell Lung Cancer Extensive Stage|Merkel Cell Carcinoma | Ariceum Therapeutics GmbH | Phase I/II |

| NCT06888323 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-lintuzumab | Testing an Anti-cancer Radio-Active Immunotherapy Called [225Ac]Ac-lintuzumab in Patients With High-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome That Has Not Responded to Other Treatment | Not yet recruting | Refractory Myelodysplastic Syndrome | National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Phase I |

| NCT06881823 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-R2 (AAA802); [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-R2 (AAA602) |

Study to Assess [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-R2 (AAA602) and [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-R2 (AAA802) in Participants With PSMA-positive HRLPC | Not yet recruting | Prostate Cancer | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | Phase I/II |

| NCT06879041 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-AZD2284 | A Phase I Study of [225Ac]Ac-AZD2284 in Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-04 | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | AstraZeneca | Phase I |

| NCT06802523 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-lintuzumab | Testing the Combination of Targeted Radiotherapy With Anti-Cancer Drugs, Venetoclax and ASTX-727, to Improve Outcomes for Adults With Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Not yet recruting | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Phase I |

| NCT06736418 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-ABD147 | Study of [225Ac]Ac-ABD147to Establish Optimal Dose in Patients With SCLC and LCNEC of the Lung That Previously Received Platinum-based Chemotherapy | Ongoing, estimated completion 2027-01 | Small-Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC)|Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Lung | Abdera Therapeutics Inc. | Phase I |

| NCT06726161 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-RYZ811; [225Ac]Ac-RYZ801 | Study of the Theranostic Pair RYZ811 (Diagnostic) and RYZ801 (Therapeutic) to Identify and Treat Subjects With GPC3+ Unresectable HCC | Ongoing, estimated completion 2031-01 | HCC | RayzeBio, Inc. | Phase I |

| NCT06590857 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTATATE (RYZ101) | Trial of [225Ac]Ac-DOTATATE (RYZ101) in Subjects with ER+, HER2-negative Unresectable or Metastatic Breast Cancer Expressing SSTRs. | Ongoing, estimated completion 2033-01 | Metastatic Breast Cancer HER2-negative ER+ | RayzeBio, Inc. | Phase I/II |

| NCT06287944 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA- Daratumumab |

[225Ac]Ac-DOTA -Anti-CD38 Daratumumab Monoclonal Antibody With Fludarabine, Melphalan and Total Marrow and Lymphoid Irradiation as Conditioning Treatment for Donor Stem Cell Transplant in Patients With High-Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndrome | Ongoing, estimated completion 2028-05 | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; Acute Myeloid Leukemia; Myelodysplastic Syndrome | City of Hope Medical Center | Phase I |

| NCT06229366 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-62 | [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-62 Trial in Oligometastatic Hormone Sensitive and Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer | Ongoing, estimated completion 2027-09 | Prostate Cancer | Eli Lilly and Company | Phase I |

| NCT05983198 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-R2 | Phase I/II Study of [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-R2 in PSMA-positive Prostate Cancer, With/Without Prior [177Lu]Lu-PSMA RLT (SatisfACtion) | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-11 | mCRPC treated with prior ARPI in post- 177Lu and pre-177Lu settings | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | Phase I/II |

| NCT05605522 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-FPI-2059 | A Study of [225Ac]Ac-FPI-2059 in Adult Participants With Solid Tumours | Active not recruting, estimated completion 2025-09 | NTSR1-positive solid tumours refractory to standard therapies | Fusion Pharmaceuticals Inc. | Phase I |

| NCT05595460 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTATATE (RYZ101) | Study of RYZ101 in Combination With SoC in Subjects With SSTR+ ES-SCLC | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-03 | SSTR2-positive extensive-stage small- cell lung cancer | RayzeBio, Inc. | Phase I |

| NCT05567770 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-J591 | Actinium-J591 Radionuclide Therapy in PSMA-Detected Metastatic HOrmone-Sensitive Recurrent Prostate CaNcer | WITHDRAWN | Prostate Cancer Metastatic | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Phase I |

| NCT05477576 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTATATE (RYZ101) | Study of RYZ101 Compared With SOC in Pts w Inoperable SSTR+ Well-differentiated GEP-NET That Has Progressed Following 177Lu-SSA Therapy | Ongoing, estimated completion 2028- 07 |

SSTR2-positive gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours with prior 177Lu therapy |

RayzeBio, Inc. | Phase III |

| NCT05363111 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA- daratumuab |

Radioimmunotherapy [111I]I/[225Ac]Ac-DOTA -daratumumab) for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma | Ongoing, estimated completion 2025-06 | Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after at least 2 lines of prior therapy | City of Hope Medical Center | Phase I |

| NCT05219500 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-FPI-2265 (PSMA-I&T) |

Targeted Alpha Therapy With [225Ac]Ac-FPI-2265-Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)-I&T of Castration-resISTant Prostate Cancer (TATCIST) | Active, not recruting, estimated completion 2025-07 |

mCRPC with prior ARPI | Fusion Pharmaceuticals | Phase II |

| NCT05204147 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-DOTA-M5A | Actinium 225 Labeled Anti-CEA Antibody ([225Ac]Ac-DOTA-M5A) for the Treatment of CEA Producing Advanced or Metastatic Cancers | Ongoing, estimated completion 2025-08 | Metastatic solid tumours expressing CEA | City of Hope Medical Center | Phase I |

| NCT04946370 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-J591 | Phase I/II Trial of Pembrolizumab and Androgen-receptor Pathway Inhibitor With or Without [225Ac]Ac-J591for Progressive Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer | Ongoing, estimated completion 2028- 06 |

mCRPC treated with prior ARPI | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Phase I/II |

| NCT04886986 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-J591 with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-I&T | Phase I/II [225Ac]Ac-J591 Plus [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-I&T for Progressive Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer | Suspended, estimated completion 2027-12 | mCRPC treated with prior ARPI | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Phase I/II |

| NCT04644770 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac DOTA-h11B6 (JNJ-69086420) |

A Study of JNJ-69086420, an Actinium-225-Labeled Antibody Targeting Human Kallikrein-2 (hK2) for Advanced Prostate Cancer | Ongoing, estimated completion 2025-12 |

mCRPC with prior ARPI | Janssen Research & Development, LLC | Phase I |

| NCT04597411 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617 | Study of [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617 in Men With PSMA-positive Prostate Cancer | Ongoing, estimated completion 2027-01 |

mCRPC | Endocyte | Phase I |

| NCT04576871 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-J591 | Re-treatment [225Ac]Ac-J591for mCRPC | Active non recruting, estimated completion 2026-12 |

mCRPC treated with prior ARPI | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Phase I |

| NCT04506567 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-J591 | Fractionated and Multiple Dose [225Ac]Ac-J591for Progressive mCRPC | Active non recruting, estimated completion 2027-06 | mCRPC treated with prior ARPI | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Phase I/II |

| NCT03932318 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab | Venetoclax, Azacitidine, and [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab in AML Patients | WITHDRAWN | Acute Myeloid LeukemiaRelapsed Adult AML | Actinium Pharmaceuticals | Phase I/II |

| NCT03867682 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab | Venetoclax and [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab in AML Patients | Unknown status | Relapsed/refractory AML | Actinium Pharmaceuticals | Phase I/II |

| NCT03746431 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-FPI-1434 | A Phase 1/2 Study of [225Ac]AcFPI-1434 Injection | Ongoing, estimated completion 2026- 06 |

IGF-1R-positive solid tumours refractory to standard therapies | Fusion Pharmaceuticals | Phase I/II |

| NCT03705858 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab | [225Ac]Ac -Lintuzumab in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia | WITHDRAWN | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Joseph Jurcic, Columbia University | Phase I |

| NCT03441048 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab in Combination with Cladribine + Cytarabine + Filgastrim + Mitoxantrone (CLAG-M) for Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Completed; 2024-05 | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Medical College of Wisconsin | Phase I |

| NCT03276572 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-J591 | Phase I Trial of [225Ac]Ac-J591 in Patients With mCRPC | Completed with results, 2023- 09 |

mCRPC treated with prior ARPI | Weill Medical College of Cornell University | Phase I |

| NCT02998047 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab | A Phase I Study of [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab in Patients With Refractory Multiple Myeloma | Terminated, 2020-05 | Refractory Multiple Myeloma | Actinium Pharmaceuticals | Phase I |

| NCT00672165 | Ac-225 | [225Ac]Ac-Lintuzumab | Targeted Atomic Nano-Generators (Actinium-225-Labeled Humanised Anti-CD33 Monoclonal Antibody HuM195) in Patients With Advanced Myeloid Malignancies | Completed, 2015-02 | Leukemia, Myelodisplastic syndrome | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | Phase I |

| NCT00014495 | Bi-213 | [213Bi]Bi-Lintuzumab-(Bi213 MOAB M195 ) | Chemotherapy and Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in Treating Patients With Advanced Myeloid Cancer | Completed, 2009-12 | LeukemiaMyelodysplastic SyndromesMyelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative Neoplasms | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | Phase I/II |

| NCT06441994 | At-211 | PSW-1025 ([211At]At-PSMA-5) | Clinical Trial of Targeted Alpha Therapy Using [211At]At-PSMA-5] for Prostate Cancer | Ongoing, estimated completion 2027-03 | Prostate Cancer | Osaka University | Phase I |

| NCT05275946 | At-211 | TAH-1005 ([211At] NaAt) | Targeted Alpha Therapy Using Astatine-211 Against Differentiated Thyroid Cancer | Completed, 2025-03 | Thyroid Cancer | Osaka University | Phase I |

| NCT04579523 | At-211 | [211At]At -OKT10-B10 | [211At]At -OKT10-B10and Fludarabine Alone or in Combination With Cyclophosphamide and Low-Dose TBI Before Donor Stem Cell Transplant for the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed, Recurrent, or Refractory High-Risk Multiple Myeloma | Not yet recruting, estimated completion 2028-12 | Multiple Myeloma|Recurrent Multiple Myeloma|Refractory Multiple Myeloma | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center | Phase I |

| NCT04466475 | At-211 | [211At]At-OKT10-B10 | Radioimmunotherapy [211At]At -OKT10-B10 and Chemotherapy (Melphalan) Before Stem Cell Transplantation for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma | WITHDRAWN | Plasma Cell Myeloma | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center | Phase I |

| NCT04461457 | At-211 | [211At]At-MX35 F(ab’)2 | Targeted Radiation Therapy for Ovarian Cancer: Intraperitoneal Treatment With [211At]At-MX35 F(ab’)2 | Completed, 2012-01 | Ovarian Cancer | Vastra Gotaland Region | Early Phase I |

| NCT04083183 | At-211 | [211At]At-BC8-B10 Monoclonal Antibody | Total Body Irradiation and [211At]At-BC8-B10 Monoclonal Antibody for the Treatment of Nonmalignant Diseases | Ongoing, estimated completion 2028-01 | Non-Malignant Neoplasm | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center | Phase I/II |

| NCT03670966 | At-211 | [211At]At-BC8-B10 | [211At]At-BC8-B10 Followed by Donor Stem Cell Transplant in Treating Patients With Relapsed or Refractory High-Risk Acute Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndrome | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-03 | hematology plan | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center | Phase I/II |

| NCT00003461 | At-211 | [211At]At-monoclonal antibody 81C6 | Radiolabeled Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in Treating Patients With Primary or Metastatic Brain Tumours | Completed, 2005-02 | Brain and Central Nervous System TumoursMetastatic CancerNeuroblastoma | Duke University | Phase I/II |

| NCT06710756 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb-At PSV359 | [212Pb]Pb-At PSV359 Therapy for Patients With Solid Tumours | Ongoing, estimated completion 2032-05 | Pancreatic Ductal AdenocarcinomaGastric CancerEsophageal CancerColorectal CancerOvarian CancerHead and Neck Cancer | Perspective Therapeutics | Phase I/II |

| NCT06479811 | Pb-212 | [203Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET; [212Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET | [212Pb]Pb-VMT-Alpha-NET in Metastatic or Inoperable Somatostatin-Receptor Positive Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumours, Pheochromocytoma/Paragangliomas, Small Cell Lung, Renal Cell, and Head and Neck Cancers | Not yet recruting, estimated completion 2032-01 | Head and Neck TumoursKidney CancersSmall Cell Lung CancersPheochromocytoma/ParagangliomasGastrointestinal Neuroendocrine TumoursSomatostatin Receptor Positive | National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Phase I |

| NCT06427798 | Pb-212 | [203Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET; [212Pb]Pb]VMT-alpha-NET | Somatostatin-Receptors (SSTR)-Agonist [212Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET in Metastatic or Inoperable SSTR+ Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumour and Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Previously Treated With Systemic Targeted Radioligand Therapy | Ongoing, estimated completion 2039-07 | Somatostatin Receptor PositiveGastrointestinal Neuroendocrine TumoursPheochromocytomaParagangliomas | National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Phase I/II |

| NCT06148636 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET; [212Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET | A Safety Study of [212Pb]Pb-VMT-alpha-NET in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumours | Active not recruting, estimated completion 2027-11 | Neuroendocrine Tumours | David Bushnell | Early Phase I |

| NCT05725070 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb -NG001 | Phase 0/1 Study of [212Pb]Pb -NG001 in mCRPC | Completed, 2023-07 | Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | ARTBIO Inc. | Early Phase I |

| NCT05720130 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb-ADVC001 | Phase Ib/IIa Dose Escalation and Expansion Study of [²¹²Pb]Pb-ADVC001 in Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (TheraPb - Phase I/II Study). | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-12 | mCRPC with prior ARPI and no prior exposure to 177Lu |

AdvanCell Pty Limited | Phase I/II |

| NCT05655312 | Pb-212 | [203Pb]Pb-VMT01; [212Pb]Pb-VMT01 | MC1R-targeted Alpha-particle Monotherapy and Combination Therapy Trial With Nivolumab in Adults With Advanced Melanoma | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-12 | Melanoma | Perspective Therapeutics | Phase I/II |

| NCT05636618 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]VMT-α-NET; [212Pb]VMT-α-NET | Targeted Alpha-Particle Therapy for Advanced SSTR2 Positive Neuroendocrine Tumours | Ongoing, estimated completion 2029-12 | Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | Perspective Therapeutics | Phase I/II |

| NCT05557708 | Pb-212 | [203Pb]Pb-Pentixather; [212Pb]Pb-Pentixather | A Safety Study of [212Pb]Pb-Pentixather Radioligand Therapy | Not yet recruting, estimated completion 2030-06 | Carcinoid Tumour LungNeuroendocrine Tumour of the LungCarcinoma, Small-Cell Lung | Yusuf Menda | Early Phase I |

| NCT05283330 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb-DOTAM-GRPR1 | Safety and Tolerability of [212Pb]Pb-DOTAM-GRPR1 in Adult Subjects With Recurrent or Metastatic GRPR-expressing Tumours | Ongoing, estimated completion 2027- 08 |

GRPR1-positive solid tumours refractory to standard therapies |

Orano Med LLC | Phase I |

| NCT05153772 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb-DOTAMTATE | Targeted Alpha-emitter Therapy of PRRT Naïve and Previous PRRT Neuroendocrine Tumour Patients | Active not recruting, estimated completion 2028-10 | Neuroendocrine Tumours | Orano Med LLC | Phase II |

| NCT03466216 | Pb-212 | [212Pb]Pb-DOTAMTATE | Phase 1 Study of AlphaMedix™ in Adult Subjects With SSTR (+) NET | Terminated, 2023-04 | SSTR2-positive neuroendocrine tumours refractory to standard therapies |

Radiomedix and Orano Med | Phase I |