1. Introduction

Radiation pervades our environment due to naturally occurring sources that emit from various elements including the space, the Earth's crust, water, food, and construction materials. The natural background radiation, although varying geographically, has been a constant presence throughout the evolution of life, affecting every organism on the planet. The intensity of natural radiation exposure can be attributed to factors such as geographic location, geological formations, and certain human activities. Predominantly, radionuclides found within the Earth's crust, such as those from the radioactive decay series of uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232, contribute to what are known as naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM).

These radionuclides undergo a spontaneous radioactive decay process, breaking down into various constituent elements until they reach stable isotopic forms. This phenomenon is notable in high-level natural radiation areas (HLNRAs) across the globe, which serve as critical zones for research on the biological and health impacts of chronic low-level natural radiation exposure on humans. In these areas, natural radiation levels can be 10 to 100 times higher than typical regions.

Specific regions around the world have notably elevated background radiation levels due to geological and geochemical conditions, which enhance terrestrial radiation [

1,

2]. For instance, the monazite sand deposits in places like Guarapari in Brazil, Yangjiang in China, and the Kerala coastal belt in southern India are significant sources of high background radiation. Furthermore, areas such as Ramsar in Iran are known for the extraordinarily high radiation levels, largely due to radium and radon emanating from local hot springs and geological formations [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Ramsar, in particular, is known for having radiation levels 55 to 200 times the global average, making it one of the most densely populated high-radiation zones in the world [

2,

12,

13,

14].

The International Commission on Radiation Protection (ICRP) established a global annual radiation exposure limit of 1 mSv to safeguard humans and wildlife [

15]. Contrastingly, in Ramsar, where natural radiation levels are exceptionally high, residents can experience annual exposure rates as high as 260 mSv, with an average dose rate of about 10 mGy for its roughly 2,000 inhabitants [

16,

17,

18]. The radon levels in certain Ramsar sites can reach up to 31,000 Bq/m3, significantly higher than less affected areas where levels are below 148 Bq/m

3. The residents of these areas are also being exposed to elevated levels of alpha activity through ingestion of radium and its decay products, as some residents consume vegetables and fruits grown in local hot soil. Consequently, annual radiation exposure levels for some residents far exceed the ICRP's occupational dose limit of 20 mSv/year [

15].

Living in areas with high radiation exposure has posed significant health concerns across generations. If annual radiation levels in the hundreds of mSv range were detrimental, leading to genetic abnormalities or an increased risk of cancer, evidence of such effects would be apparent in the local populations [

16]. However, reports suggest no significant increase in cancer mortality or incidence in Ramsar, with some studies even indicating a decrease in cancer rates among high background radiation area (HBRA) residents. Yet, the challenge remains to gather sufficient long-term epidemiological data from about 2,000 residents to obtain statistically reliable data, due to the small population living in the most affected areas.

This lack of long-term epidemiological data raises numerous public health policy issues, such as whether to relocate inhabitants to areas with lower natural background radiation levels and the financial and emotional costs associated with such relocation. The unique conditions in Ramsar offer invaluable insights into the epidemiological impacts of low-dose radiation exposure, an area still not fully understood. Thus, studying the potential health risks, particularly cancer, in high radiation background areas like Ramsar is crucial, not only for expanding our knowledge on low-dose radiation effects but also for assessing the specific cancer risks associated with such environments. Given that Ramsar has the highest levels of background radiation among residential areas worldwide, the significance of investigating the causal relationship between high background radiation and cancer incidence is unequivocally critical.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

In this study, 32 C57BL/6 mice weighing 18-20 g, aged 4-5 weeks were purchased from the Comparative and Experimental Medicine Center at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The animals were randomly assigned to four groups of 7-9 mice each. They were housed under controlled conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle at a temperature of 21 ± 1°C, with ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental protocols adhered to the guidelines set by on the care of laboratory animals and their use for scientific purposes of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS).

Exposure to Naturally Elevated Levels of Radiation:

The first group (designated as Bkg) was exposed to normal background radiation (0.097 μSv/h) in a standard room for approximately two months. The second, the third, and the fourth groups were exposed to higher levels of gamma radiation in indoor environments that could mimic high background radiation areas of Ramsar. The dose rates were 3.85 μSv/h (~40X Bkg), 6.66 μSv/h (~65X Bkg), and 9.24 μSv/h (~100X Bkg), respectively. The third group (65X Bkg) also experienced elevated radon levels, achieved by housing the mice in a cage with Ramsar radioactive soil to artificially increase Rn-220 levels, resulting in an average radon concentration of 681.84 Bq/m³, compared to 40 Bq/m³ in the laboratory environment. Radon levels were monitored using a PRASSI portable radon gas survey meter. The cages were designed to allow radon accumulation, and gamma radiation was measured with a calibrated RDS 110 survey meter positioned about 1 meter above the ground at each location.

2.2. Cell Culture:

Murine melanoma cells (B16F10 line) were obtained from the Transplant Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. These cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. Cell viability was assessed using trypan blue exclusion.

2.3. Induction of B16-F10 Melanoma in Mice:

After approximately 5 weeks of radiation exposure, each mouse received an injection of 1×10^6 B16-F10 cells suspended in 200 µL of Ringer’s solution into the shaved left flank. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring the size of tumors at regular intervals. Measurements were taken using calipers on days 14, 17, 20, and 24 post-injection, recording the shortest and longest tumor diameters. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula:

volume (cm

3) =

(width

2 × length) [

19,

20,

21]

This method provides a consistent and reliable assessment of tumor volume, correlating well with other evaluation metrics like tumor weight to carcass weight ratios [

19].

2.4. MRI Study Protocol:

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed using various sequences as outlined in

Table 1.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, Version 21 and GraphPad PRISM 9. The primary objective was to assess the impact of varying levels of radiation exposure on tumor growth and survival rates among the different experimental groups. Continuous variables such as tumor volume were summarized using mean and standard deviation, while categorical data such as survival rates were expressed in percentages. Some mice were lost during the study, resulting in missing observations on certain days. Therefore, instead of applying the usual statistical methods, we used mixed model analysis to examine the differences in tumor volumes between groups at specific time points. Additionally, to investigate the trend of tumor volume changes over time, we calculated linear regression coefficients for each group separately.

Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method, with log-rank tests employed to compare survival curves between the different exposure groups. This method allowed for the assessment of the survival probability over the study period, accounting for the varying levels of radiation exposure.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. This threshold was chosen to balance the risk of type I and type II errors, providing a rigorous yet reasonable criterion for statistical significance in the context of experimental oncology. All statistical tests were two-sided, reflecting the a priori hypothesis that increased radiation could either inhibit or accelerate tumor growth, depending on the radiation dose and biological context. This comprehensive statistical approach ensured robust and reliable conclusions could be drawn from the study data.

3. Results:

3.1. Tumor Volume Analysis:

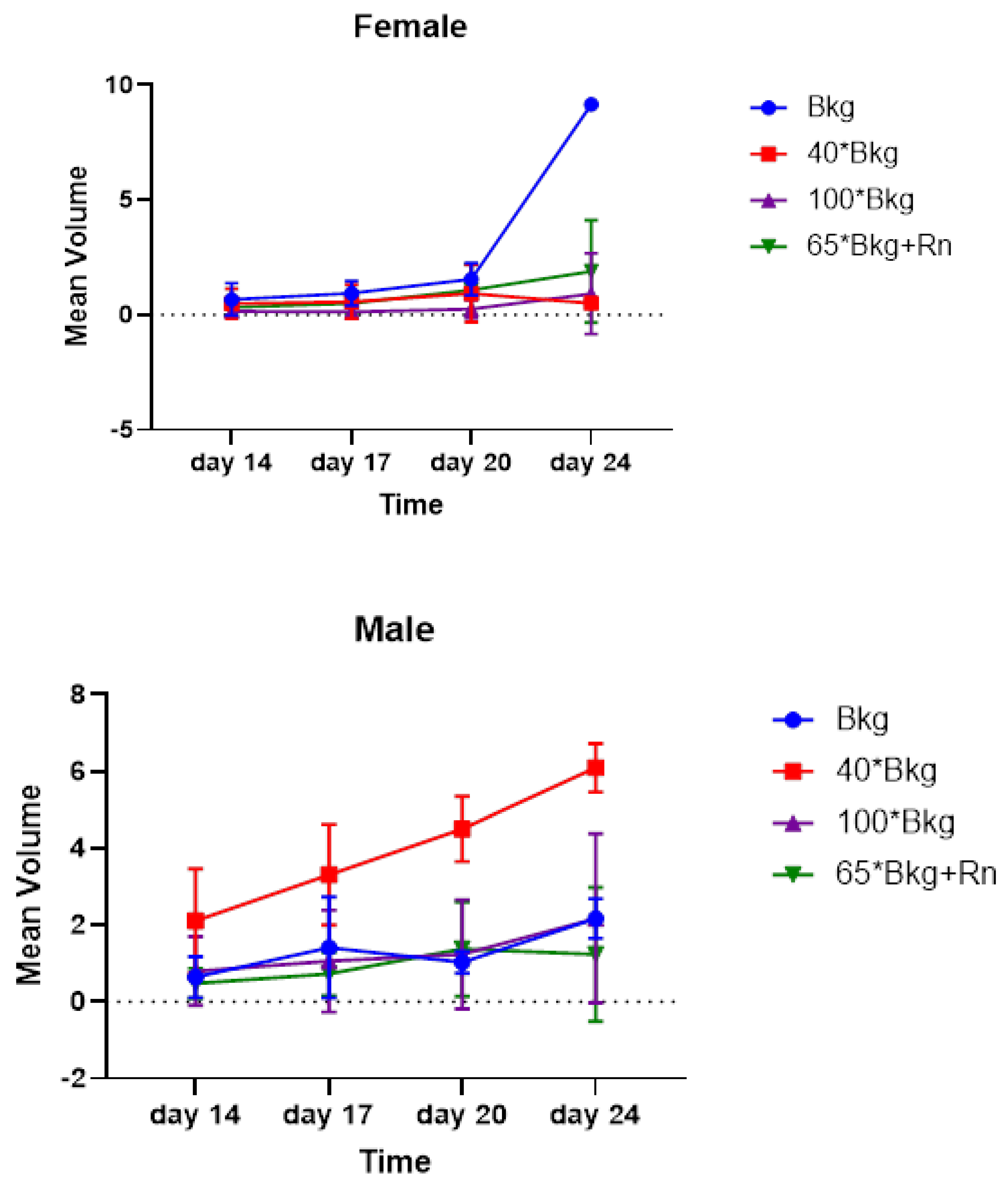

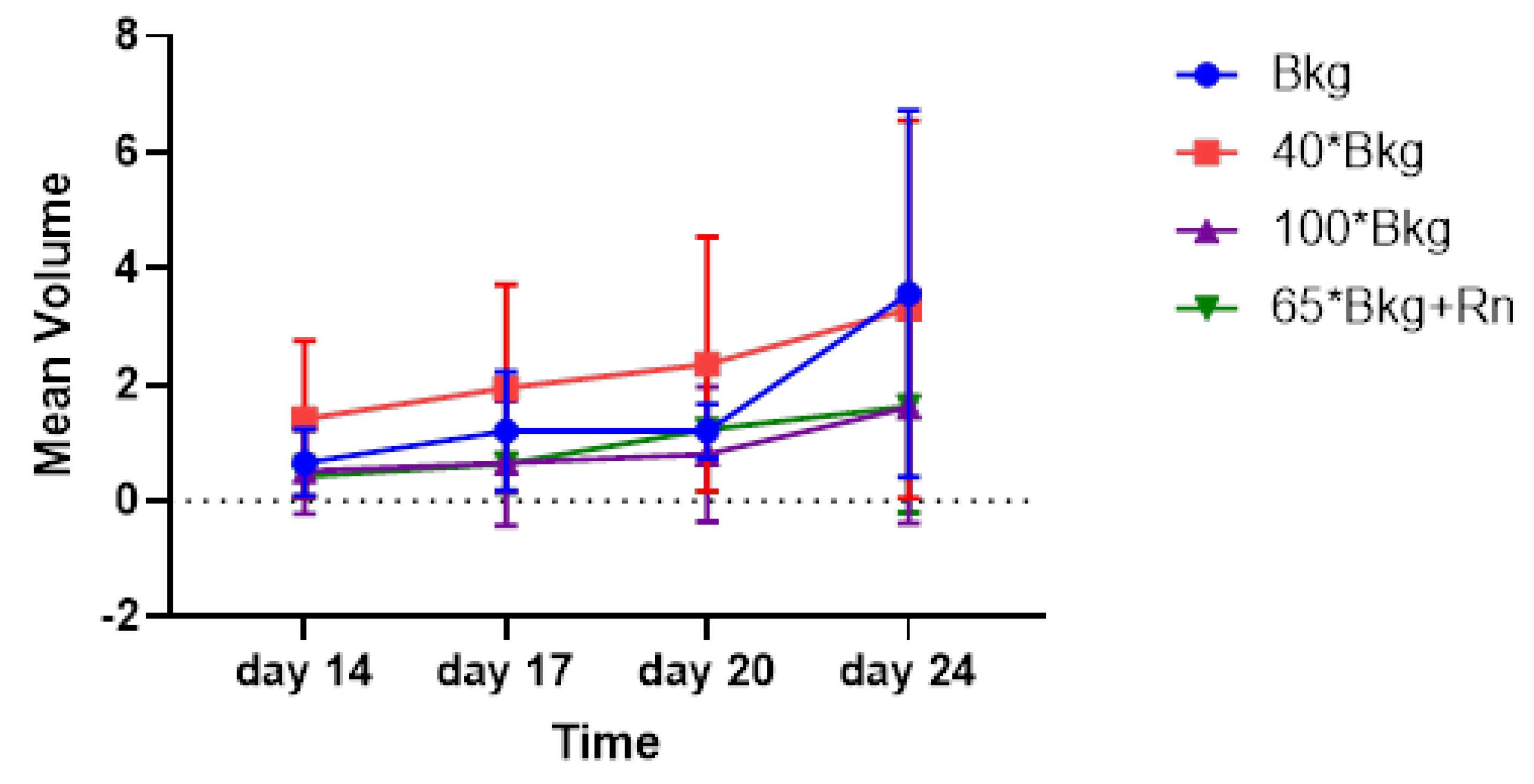

On the 24th day post-injection, the mean tumor sizes in mixed gender groups treated with Bkg (control), 40X Bkg, 65X Bkg with radon gas, and 100X Bkg were 3.57 cm³, 3.30 cm³, 1.63 cm³, and 1.62 cm³ respectively (

Table 2). Analyzing by gender, the mean tumor sizes for male mice were 2.17 cm³, 6.10 cm³, 1.24 cm³, and 2.17 cm³ in the Bkg, 40X Bkg, 65X Bkg with radon gas (Rn), and 100X Bkg groups respectively. In female mice, the corresponding sizes were 9.16 cm³, 0.51 cm³, 1.89 cm³, and 0.92 cm³. A non significant difference in tumor volume was observed between the 100X Bkg and control groups in female mice, indicating potential interactions between radiation exposure levels and tumor growth in these specific setups.

In some instances, tumor disintegration and volume reduction were observed in the 100X Bkg and 65X Bkg with Rn groups, whereas no decrease was noted in the Bkg and 40X Bkg groups, where tumor volume increased in all mice.

3.2. Regression Analysis:

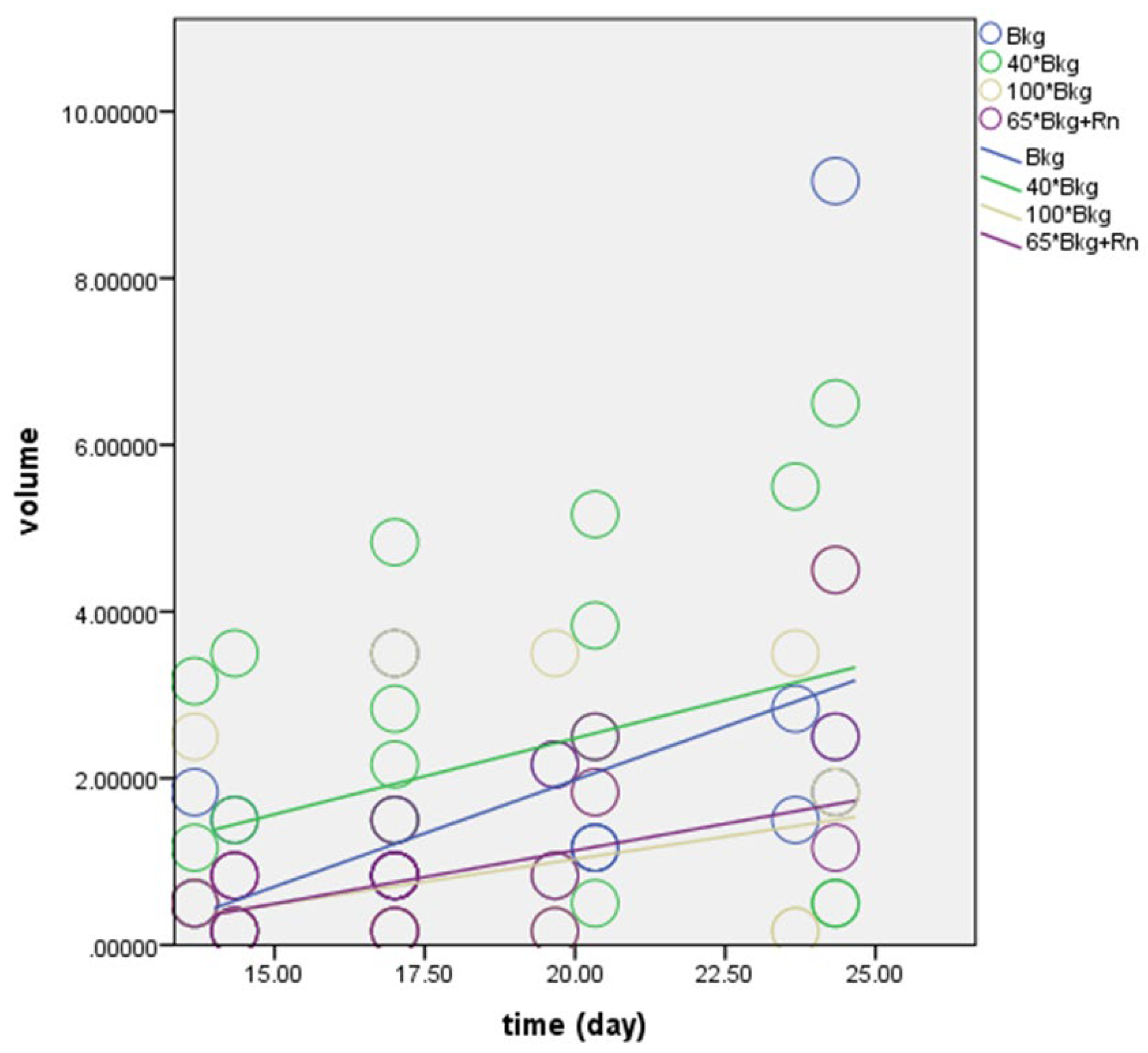

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the slope of the regression lines for the normal Bkg, 40X Bkg, 65X Bkg with Rn, and 100X Bkg groups were recorded as 0.807, 0.591, 0.347, and 0.420, respectively. These values represent the daily rate of tumor volume increase, highlighting the highest growth in the normal Bkg group and the lowest in the 100X Bkg group.

Figure 2 illustrates the incremental tumor growth in male and female mice across different exposure groups, demonstrating variable rates of tumor progression influenced by radiation exposure levels.

Figure 3 illustrates the tumor growth in all mice (male and female mice) across different exposure groups

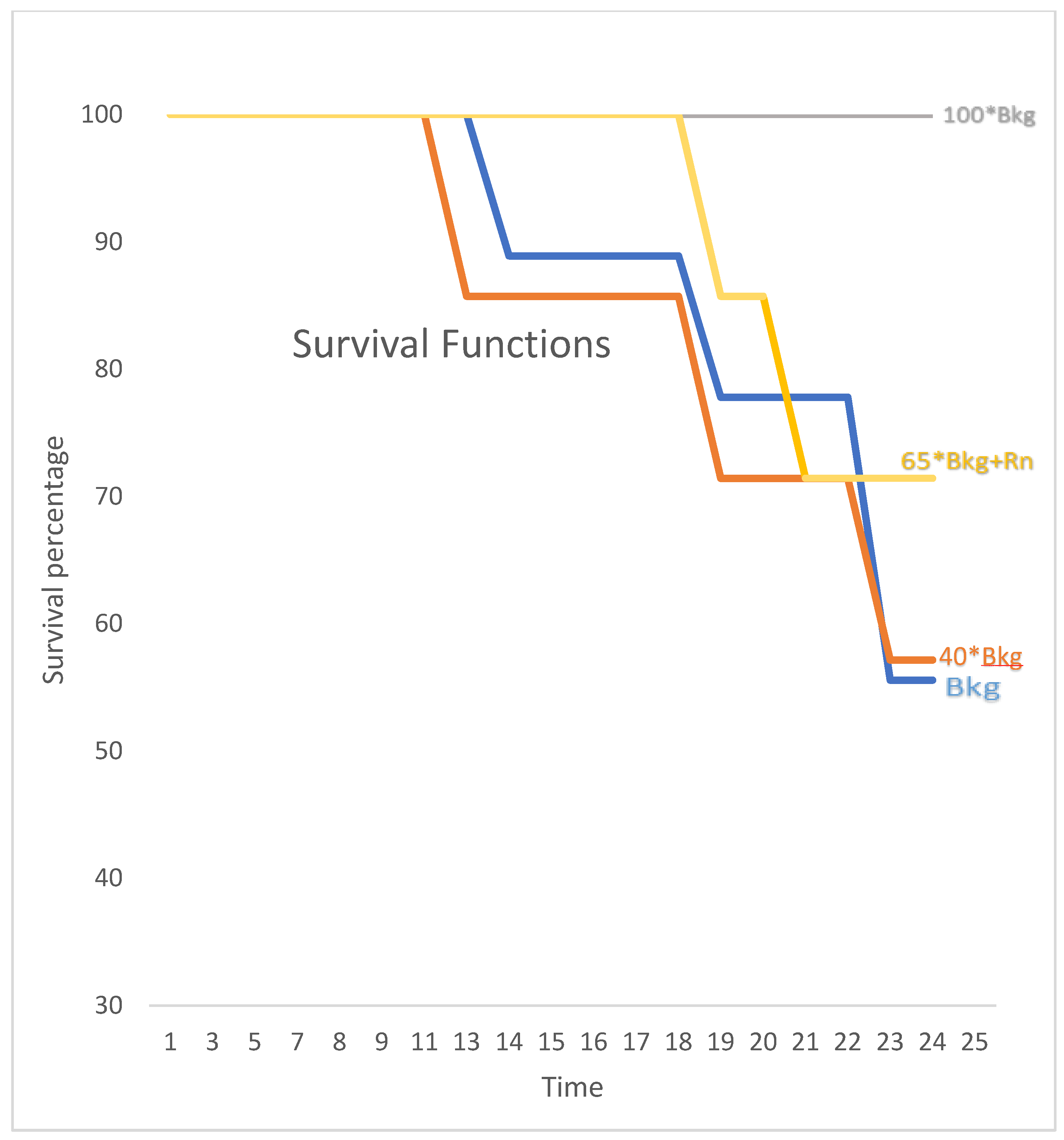

Figure 4 shows the survival rates of mice across different radiation exposure groups, with marked differences between those exposed to the highest and lower radiation levels. The statistical analysis confirms the significance of these differences, underscoring the potential protective or adaptive responses in the highest exposure group.

3.3. Survival Analysis:

The survival rates on the 24th day post-injection for the normal Bkg, 40X Bkg, 65X Bkg with Rn, and 100X Bkg groups were 55.56%, 57.14%, 71.42%, and 100% respectively. The survival difference between the 100X Bkg and both the control (normal Bkg) and 40X Bkg groups was statistically significant (P=0.02 and P=0.03, respectively).

The data demonstrate significant effects of radiation exposure on tumor growth dynamics and survival rates, highlighting potential biological impacts of environmental radiation variations.

4. Discussion

The ALARA principle, advocating that all ionizing radiation exposure should be kept as low as reasonably achievable, is based on the assumption that any level of exposure carries some risk. This principle underpins regulations that lead to spending hundreds of billions of dollars annually worldwide to maintain low radiation levels [

22]. However, our findings suggest a need to reassess the Linear No-Threshold (LNT) paradigm, particularly within the scope of natural background radiation levels.

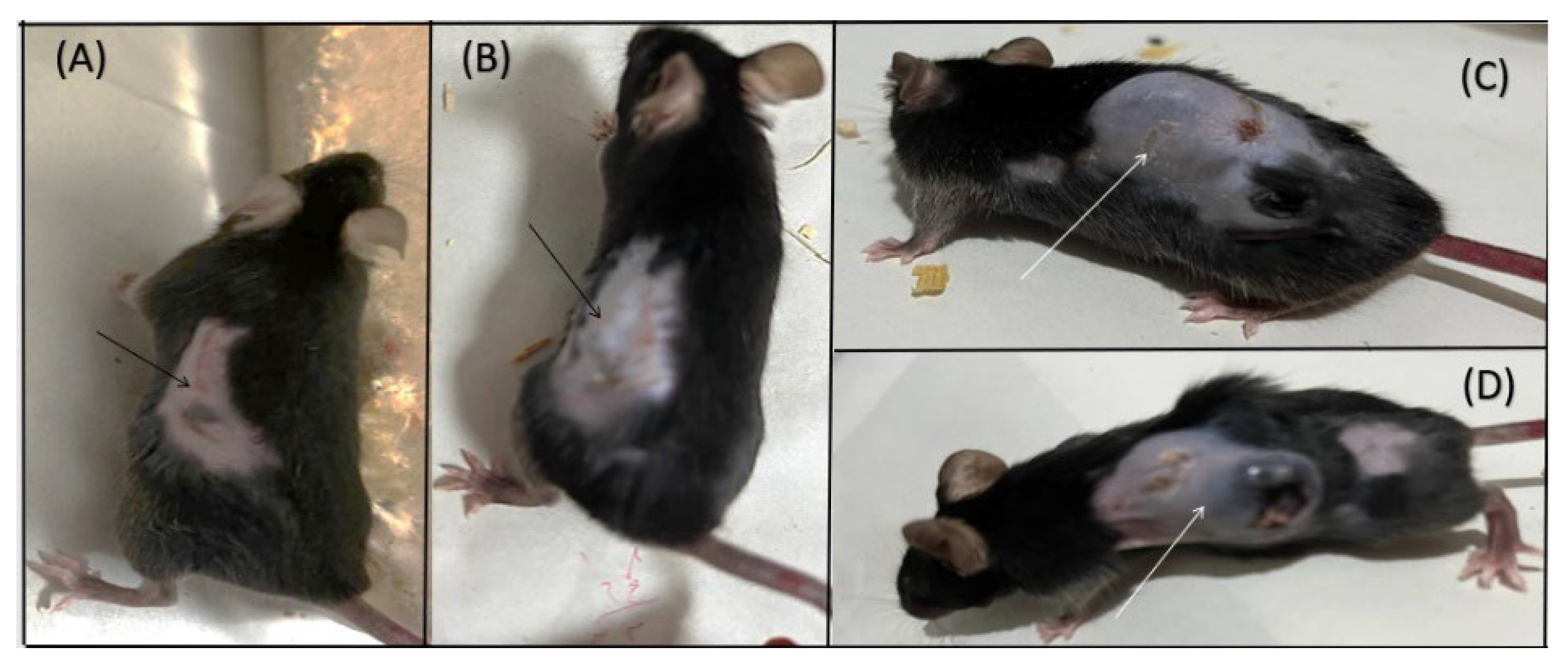

Our results reveal that the highest levels of natural background radiation not only cause no harm compared to the lowest levels but also appear to confer beneficial health effects. This is particularly evident when comparing the control group and the 100X Bkg group in our study. In the 100X Bkg group, which was exposed to substantially higher radiation levels, out of the four female mice in the 100X Bkg group showed tumor reduction and volume decrease while one female mouse in this group showed an increase in tumor volume. Given this consideration, tumor size reduction and tumor disintegration were noted, contrasting sharply with the control group, where normal background radiation was associated with tumor growth.

These findings suggest that the protective effects observed at higher radiation exposures might prompt a reevaluation of current radiation safety standards and the underlying radiobiological models. Could you share more about the specific methodologies used to measure and compare tumor growth across different groups in your study? This would help further clarify the context and significance of your findings.

Figure 5. illustrates melanoma progression in mice, with panels (A) and (B) showing the 100X Bkg group where tumor size reduction and tumor disintegration were observed, indicated by arrows. Panels (C) and (D) display the control (Bkg) group, where tumors have grown, also highlighted by arrows. These images represent tumor conditions at day 20 post intradermal injection of B16-F10 melanoma cells.

Our study found a significant difference in tumor progression between female and male mice, with notable findings in the female subset. It is worth mentioning that tumor volume reduction was also observed in male mice (one male mouse in the 100X Bkg group and one male mouse in the 65X Bkg group), but their numbers were fewer compared to the female mice. Additionally, the rate of tumor volume increase was higher in the control group compared to all other groups, while the 100X Bkg group exhibited the lowest rate of increase in tumor volume. Furthermore, the survival rate in the 100X Bkg group was significantly higher than in the control group; all mice in the 100X Bkg group survived to the end of the study period despite the presence of tumors, whereas about half of the mice in the control group did not survive. These results suggest that higher levels of background radiation may influence both tumor development and survival outcomes, potentially pointing to complex interactions between radiation exposure and biological responses.

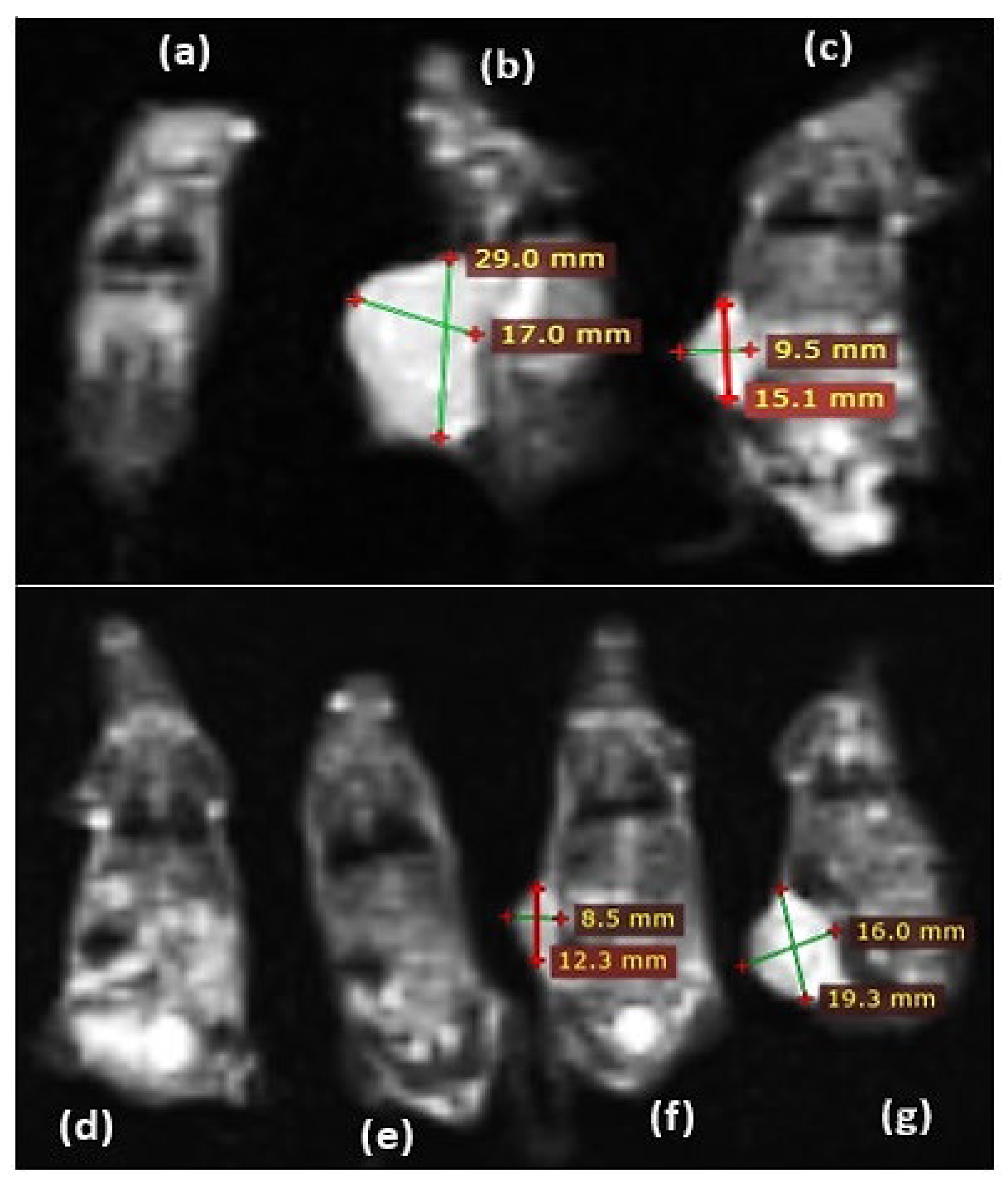

This series of magnetic resonance images showcases various stages of skin cancer in C57BL/6 mice: (a) T2 coronal image of a mouse from the 65X Bkg with radon gas group showing tumor disintegration. (b, c) Images of skin cancer in a mouse from the Bkg (control) group. (d, e) Images from a mouse in the 100X Bkg group. (f, g) Skin cancer in a mouse from the 40X Bkg group (

Figure 6). All images were taken with a field of view of 200 × 200 mm and an acquisition matrix size of 128 × 128, ensuring a spatial resolution with a 3-mm slice thickness.

Lifespan and Cancer Mortality Trends:

This radiation-induced extension of lifespan may largely be attributable to a reduction in cancer mortality observed in high-level radiation (HLR) areas for several types of cancer, including lung, pancreas, colon, brain, and bladder cancers. Similar trends of lower cancer mortality rates in regions with higher background radiation have also been reported in human populations in India [

23] , Iran, and China [

24] . While these studies involve human subjects, our animal-based research aligns with these findings [

25,

26,

27,

28].

However, human studies face significant limitations. The effects of low radiation levels, comparable to natural background levels, on human health and longevity are challenging to determine due to the small population sizes typically studied, which complicates the ability to achieve statistically significant observations [

29,

30,

31] . Furthermore, confounding factors such as income level, lifestyle choices like smoking, and other carcinogenic exposures or socioeconomic conditions can significantly influence life expectancy and health status in human studies.

Given these complexities, our study utilized an animal model to provide a controlled environment for observing the effects of radiation. Our findings indicate that high levels of natural radiation can impede cancer growth, showing that mice in areas with radiation levels higher than normal exhibit increased resistance to cancer compared to those in the control group. This suggests potential adaptive responses to elevated radiation levels, highlighting a complex interplay between radiation exposure and biological outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that challenges conventional paradigms about radiation exposure and cancer progression, suggesting that higher levels of natural background radiation may not uniformly correlate with adverse health outcomes. Remarkably, our results indicate that elevated radiation levels can have a protective effect against the growth of melanoma in C57BL/6 mice, highlighted by reduced tumor sizes and improved survival rates in the highest radiation exposure group compared to controls.

The novelty of this study lies in its direct challenge to the Linear No-Threshold (LNT) model, which posits that any amount of radiation exposure is harmful. Our findings contribute to a growing body of research suggesting that there may be a threshold or hormetic effect where radiation could play a protective role in certain biological contexts. This study is among the first to empirically demonstrate such effects in a controlled animal model, providing a valuable reference point for re-evaluating radiation safety standards and cancer risk assessment models.

Implications for cancer research are significant, as these findings open new avenues for exploring radiation as a potential tool in cancer prevention strategies, particularly in environments with naturally high radiation levels. It prompts a reconsideration of radiation's role from merely a risk factor to a complex environmental factor that can have dual effects depending on exposure levels and biological contexts.

Furthermore, the study underscores the need for more nuanced public health policies regarding radiation exposure. Current standards based on the LNT model may need revision to consider potential beneficial effects of radiation at certain levels, which could lead to more balanced risk-benefit analyses in radiation regulation and management.

Given these considerations, our study not only shifts the discussion regarding radiation and cancer but also sets the stage for future investigations that might ultimately lead to novel approaches in cancer prevention and therapy. The interplay between radiation exposure and cancer development remains a complex and dynamically evolving field, and our work contributes a critical piece to this intricate puzzle.

References

- Nations, U. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. UNSCEAR Report. 1993.

- Radiation UNSCotEoA. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) 2000 Report, Volume I: Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes-Sources: United Nations; 2000.

- Bennett B, editor Exposure to natural radiation worldwide. Proceedings of the fourth international conference on high levels of natural radiation: radiation doses and health effects, Beijing, China; 1996.

- CULLEN TL, editor Review of Brazilian investigations in areas of high natural radioactivity. Part I: Radiometric and dosimetric studies. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Areas of High Natural Radioactivity; 1977.

- Franca, E. Review of Brazilian investigations in areas of high natural radioactivity, 2. pt.

- Paschoa, A.S. More than forty years of studies of natural radioactivity in Brazil. Technology 2000, 7, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Sugahara, T. An introductory overview of the epidemiological study on the population at the high background radiation areas in Yangjiang, China. Journal of Radiation Research 2000, 41, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Zha, Y.; Tao, Z.; He, W.; Chen, D.; Yuan, Y. Epidemiological investigation in high background radiation areas of Yangjiang, China. 1993.

- Sunta C, editor A review of the studies of high background areas of the SW coast of India. Proceedings of the international conference on high levels of natural radiation, Ramsar, IAEA; 1993: Citeseer.

- Sunta, C.; David, M.; Abani, M.; Basu, A.; Nambi, K. Analysis of dosimetry data of high natural radioactivity areas of SW coast of India. Natural radiation environment 1982.

- Sohrabi M, editor Recent radiological studies of high level natural radiation areas of Ramsar. Proceeding of International Conference on High Levels of Natural Radiations; 1993: Citeseer.

- Mortazavi, S.; Mozdarani, H. Is it time to shed some light on the black box of health policies regarding the inhabitants of the high background radiation areas of Ramsar? International Journal of Radiation Research 2012, 10, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi, S.; Mozdarani, H. Non-linear phenomena in biological findings of the residents of high background radiation areas of Ramsar. International Journal of Radiation Research 2013, 11, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi, S.; Niroomand-Rad, A.; Mozdarani, H.; Roshan-Shomal, P.; Razavi-Toosi, S.; Zarghani, H. Short-term exposure to high levels of natural external gamma radiation does not induce survival adaptive response. International Journal of Radiation Research 2012, 10, 165. [Google Scholar]

- ICoR, P. recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann ICRP. 1990, 21, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiassi-Nejad, M.; Mortazavi, S.; Cameron, J.; Niroomand-Rad, A.; Karam, P. Very high background radiation areas of Ramsar, Iran: preliminary biological studies. Health physics 2002, 82, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S.; Ghiassi-Nejad, M.; Karam, P.; Ikushima, T.; Niroomand-Rad, A.; Cameron, J. Cancer incidence in areas with elevated levels of natural radiation. International Journal of Low Radiation 2006, 2, 20–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi S, Ghiassi-Nejad M, Rezaiean M, editors. Cancer risk due to exposure to high levels of natural radon in the inhabitants of Ramsar, Iran. International Congress Series; 2005: Elsevier.

- Daly, J.M.; Reynolds, H.M.; Rowlands, B.J.; Dudrick, S.J.; Copeland 3rd, E. Tumor growth in experimental animals: nutritional manipulation and chemotherapeutic response in the rat. Annals of Surgery 1980, 191, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond H, Schuchter L, Bartlett D, Kelly C, Shou J, Leon P, et al. Anti-neoplastic effects of interleukin-4. Journal of Surgical Research 1992, 52, 406–11.

- Reilly, J.J.; Goodgame, J.T.; Jones, D.C.; Brennan, M.F. DNA synthesis in rat sarcoma and liver: The effect of starvation. Journal of Surgical Research 1977, 22, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, C.L. Radiobiology and radiation hormesis. Springer 2017, 10, 978–3. [Google Scholar]

- Nambi, K.; Soman, S. Environmental radiation and cancer in India. Health Physics 1987, 52, 653–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.R.; Loganovsky, K. Low dose or low dose rate ionizing radiation-induced health effect in the human. Journal of environmental radioactivity 2018, 192, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.L. Test of the linear-no threshold theory of radiation carcinogenesis for inhaled radon decay products. Health Physics 1995, 68, 157–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.L. Lung cancer rate vs. mean radon level in US counties of various characteristics. Health Physics 1997, 72, 114–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, J. Cancer mortality in six lowest versus six highest elevation jurisdictions in the US. Dose-Response 2011, 9, dose-response. 09-051. Hart.

- Hart, J. Cancer mortality for a single race in low versus high elevation counties in the US. Dose-Response 2011, 9, dose-response. 10-014. Hart.

- Cameron, J. Moderate dose rate ionizing radiation increases longevity. The British Journal of Radiology 2005, 78, 11–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrzyński, L.; Fornalski, K.W.; Feinendegen, L.E. Cancer mortality among people living in areas with various levels of natural background radiation. Dose-Response 2015, 13, 1559325815592391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendry, J.H.; Simon, S.L.; Wojcik, A.; Sohrabi, M.; Burkart, W.; Cardis, E.; et al. Human exposure to high natural background radiation: what can it teach us about radiation risks? Journal of Radiological Protection 2009, 29, A29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).