1. Introduction

Wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most widely cultivated cereal crops globally and serves as a staple food for a large portion of the world's population, providing approximately 20% of the daily caloric and protein intake [

1]. To sustain the productivity required for global food security, conventional agricultural systems have long relied on synthetic nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) fertilizers. While these inputs are effective in increasing yields, their prolonged and excessive use is associated with significant environmental challenges, including soil acidification, nutrient leaching, loss of biodiversity, and elevated greenhouse gas emissions [

2,

3,

4].

In the context of climate change and resource scarcity, the transition to sustainable fertilization practices has become a key priority in global and European agricultural policy. Organic fertilizers derived from agri-food industrial wastes are gaining attention as viable alternatives that can recycle nutrients, reduce wastes, and improve soil health [

5,

6,

7]. These materials contribute to increase organic matter and nutrients which in turn enhance soil physical structure, microbial activity, and nutrient cycling processes, ultimately benefiting crop performance and sustainability [

7,

8]. In addition to the agricultural sector, the industrial sector produces also wastes that could be recycled creating new products, valorising the waste chain. Sulphur released during the refining process of crude oil, can be recovered to be used for agricultural purpose, considering that various studies emphasized that sulfur deficiency are leading to reduced nitrogen utilization from fertilizers and production of crop proteins with significantly lower levels of sulfur-containing amino acids, particularly methionine, which greatly influences the nutritional value of crops. The use of waste-derived fertilizers perfectly aligns with the principles of the circular economy, which promotes resource efficiency, waste minimization, and carbon footprint reduction across all sectors, including agriculture [

9]. In this regard, the European Green Deal and the Circular Economy Action Plan strongly encourage the agricultural reuse of organic wastes, which can also help address the issue of declining soil organic matter in Mediterranean agroecosystems [

10,

11].

Despite their potential, the agronomic performance of waste-derived fertilizers can vary significantly depending on factors such as feedstock composition, treatment process, soil type, and climatic conditions. As a result, field-based studies are essential to validate their efficacy under different agro-environmental contexts [

8]. Furthermore, while several studies assessed either yield or soil health separately, fewer have integrated both agronomic, soil quality, yield and wheat quality across multiple years and more geographical locations [

4,

5].

The Mediterranean region, characterized by its climate variability, limited water resources, and declining soil fertility, provides a relevant setting for evaluating the sustainability of fertilization practices. Greece and Southern Italy (Apulia), in particular are important wheat-producing regions where alternative fertilization strategies could contribute to climate-resilient and environmentally sound cereal production systems [

12]. The present study aimed to evaluate the impact of conventional mineral nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium (NPK, 15-15-15) or organic horse manure (HM) fertilizers and fertilizers derived from industrial and agri-food wastes specifically orange waste residue of agro-food industry and sulphur as residue of oil industry on wheat yield, grain quality, and soil health. Conducted over two consecutive years in contrasting Mediterranean environments—Apulia (Southern Italy) and Central Macedonia (Northern Greece)—this study seeks to: (1) compare the agronomic effectiveness of different fertilizer treatments; (2) assess their effects on soil chemical and biological properties; and (3) analyze yield and quality of wheat comparing the consistence of treatment responses across sites. By integrating multiple indicators of performance, this research provides practical insights to guide sustainable nutrient management and policy development in Mediterranean cropping systems [

6,

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Experimental Design

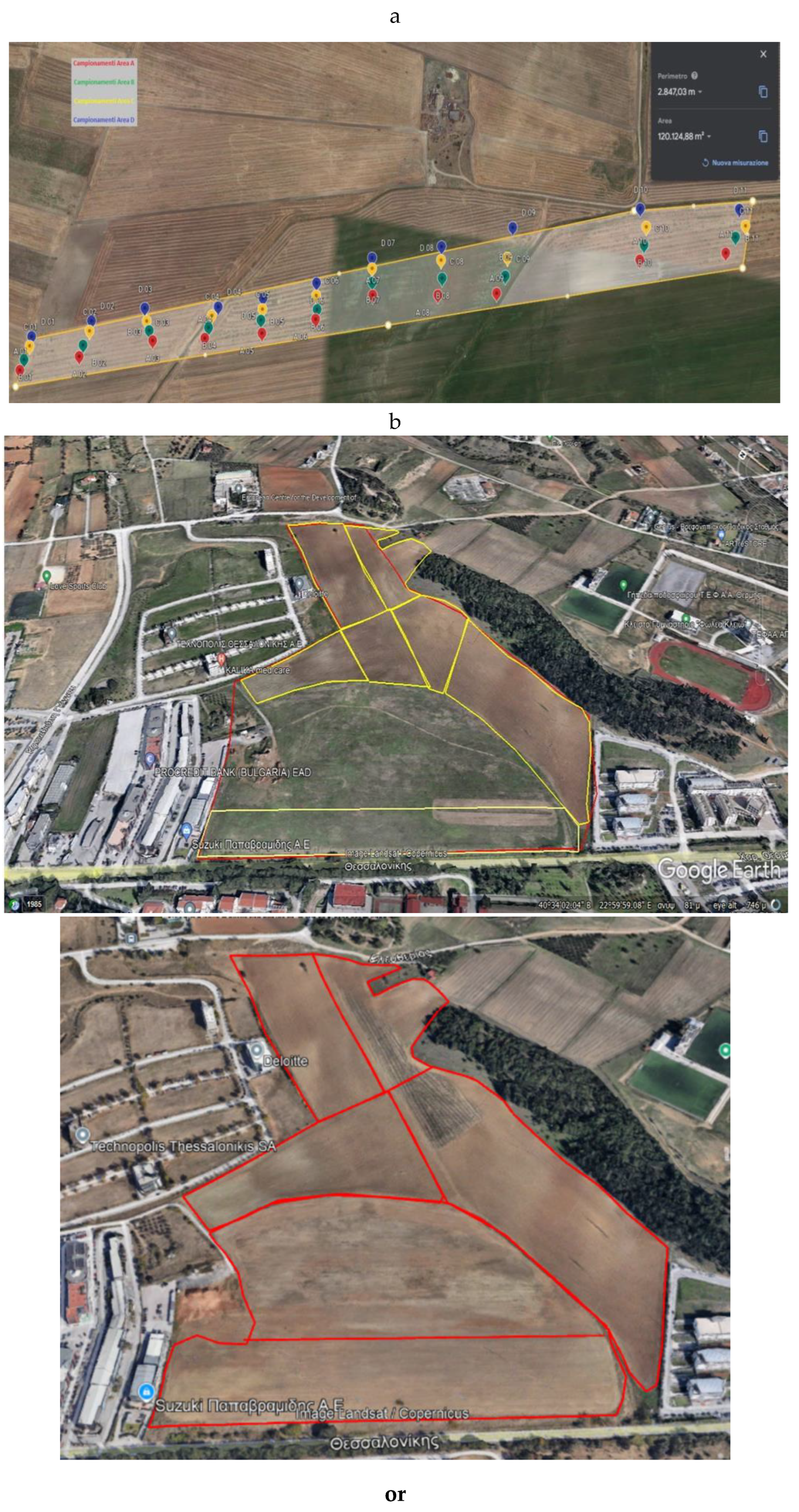

Field experiments were conducted over two consecutive cropping seasons (2021–2023) in two Mediterranean locations (

Figure 1): Southern Italy (Apulia) in 17 hectares and Central Macedonia Northern Greece (Thessaloniki) 12 hectares. Both sites are representative of typical durum wheat (

Triticum durum Desf.) cultivation areas but differ in soil types, climatic conditions, and agricultural history.

In each location, a randomized complete block design (RCBD) was implemented with three replicates per treatment. The experimental treatments included: Control (CTR) – No fertilizer; synthetic NPK (15-15-15); organic fertilizer (horse manure, HM); and Sulphur bentonite plus orange wastes (RecOrgFert). Fertilizers were applied pre-sowing at rates standardized based on equivalent nitrogen content (150 kg N ha⁻¹), and at a vegetative stage, following local agronomic guidelines. Regarding the site of Apulia, the total area of 17 hectares, has been divided into four plots of about 4 hectares each, Red, control; Green, NPK; Yellow, RecOrgFert; Blue, Horse manure. The four areas are approximately 1,335 meters in length and about 90 meters in width, maintaining homogeneity, especially considering the altitude variation, which ranges from 203 meters at the highest point to 147 meters at the lowest. Regarding Thessaloniki, the 12 hectares have been divided in 4 plots of hectares each, maintaining the homogeneity among the plots (

Figure 1 a, b).

2.2. Soil Analysis

Soil samples were collected from the top 0–35 cm layer of each plot at three time points: pre-treatment and post-harvest. Five samples per plot were composited and analyzed for the following parameters: Electric conductibility (EC) was determined in distilled water by using 1:5 residue/water suspension, mechanically shaken at 15 rpm for 1 h to dissolve soluble salts and then detected by Hanna instrument conductivity meter; pH was measured in distilled water (soil/pad:solution ratio 1:2.5) with a glass electrode. Organic carbon was assessed with dichromate oxidation method [

13]. Total nitrogen (TN) was measured with Kjeldahl method [

14]. C/N was determined as a carbon:nitrogen ratio. Water soluble phenols were extracted as reported by Kaminsky and Muller [

15,

16]. All analyses were performed following standardized protocols as outlined in ISO 10390:2005 and ISO 14240-2:1997. Soil classification followed the FAO World Reference Base (WRB) system.

2.3. Yield Measurements

At crop maturity, wheat plants were manually harvested from a 4 m² area in each plot to avoid edge effects. The following yield components were recorded: plant height (cm), Seed/ear; Yield (q/ha), calculated on the basis of the total mass of grain harvested and corrected to 13% moisture content, following standard normalisation procedures [

17]; Dry Seed (g/plant), determined by drying grain samples at a controlled temperature until they reach a constant weight and measured in grams (g) [

17]; Protein content (%): Using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), a widely adopted non-destructive method for evaluating grain quality[

18]. Gluten content and index: Measured by standard wet chemistry (ICC method No. 137/1), which provides robust indicators of baking quality [

19]. The β-carotene content was determined by extraction with a solvent mixture (acetone:ethanol:hexane, 1:1:2, v/v/v), followed by spectrophotometric quantification at 450 nm, according to Saini et al. [

20]. Results were expressed in mg/100g of dry weight. Grain moisture content was adjusted to 13% for standardization. Yield parameters were statistically analyzed across treatments and locations.

2.4. Grain Quality Analysis

Grain quality was assessed using a subsample of dried and cleaned kernels from each plot. The total phenol content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent [

21], following the procedure described by Velioglu et al. [

22]. Total flavonoid content was measured using a colorimetric method based on aluminium chloride, according to the protocol developed by Djeridane et al. [

23]. To assess antioxidant activity, two complementary methods were employed. The ABTS

+ radical cation decolorization assay was conducted following the method of Re et al.[

24], while the DPPH method, which relies on the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, was performed according to Barreca et al. [

25]. Analytical precision was verified using certified reference materials. All tests were conducted in triplicate.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for all data sets. Three-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD (honestly significant difference) test was used to assess the effects of fertilisers on the various measured parameters. Comparisons were conducted to assess the effects of fertilisers on each individual parameter. To explore the relationships between change in soil properties induced by the different fertilizer and plant and grain parameters, the datasets were analysed using Pearson correlation matrix. Statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (version R2024b, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Effects were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Experiments in Central Macedonia Greece

3.1.1. Soil Properties

Over the two-year period, all fertilization treatments induced significant changes in soil chemical parameters compared to the control (CTR), with distinct trends across 2023 and 2024. In 2023 (

Table 1), the application of NPK significantly increased organic carbon (OC) (4.00%) and organic matter (OM) (6.90%) compared to the control (2.32% OC and 4.00% OM), indicating rapid nutrient mineralization and incorporation. Horse manure (HM) and RecOrgFert also enhanced these parameters, though to a lesser extent. By 2024 (

Table 1), OC and OM were highest under NPK and RecOrgFert, with RecOrgFert showing notable improvement from the previous year (OC: 3.2%, OM: 5.5%). Interestingly, CEC increased across all treatments, particularly under HM (28.92 meq/100g). Soil pH decreased slightly across treatments in 2024 compared to 2023, especially under RecOrgFert (from 7.9 to 7.6). Electrical conductivity (EC) significantly increased in 2024 compared to 2023, suggesting higher soluble salt content.

3.1.2. Plant Growth and Yield

NPK and RecOrgFert treatments consistently enhanced plant height and seed set across both years. In 2023 (

Table 2), plants under NPK and HM were the tallest (~202–203 cm), while RecOrgFert recorded the highest seed/ear value (42 seeds). In 2024, plant height declined overall, likely due to climatic variability, yet NPK (190.2 cm), HM (186.8 cm) and RecOrgFert (173.0 cm) remained superior to the control. Seed/ear values increased in 2024 (

Table 2), especially under NPK and RecOrgFert (53 and 50 seeds, respectively). Yield values were highest under NPK in both years (19.76 q/ha in 2023; 17.51 q/ha in 2024), followed by RecOrgFert. While HM led to high dry seed mass in 2023 (2.2 g/plant), this advantage diminished in 2024. RecOrgFert maintained good yield stability. Protein and gluten content improved under RecOrgFert, reaching 16.6% and 23.4% in 2024, suggesting enhanced nutritional quality. Notably, β-carotene content tripled from ~0.62 to over 2.29 mg/100g across all treatments between years, pointing to environmental or varietal influence.

3.1.3. Grain Biochemical Quality

RecOrgFert and HM performed best in enhancing phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity. In 2023 (

Table 3), RecOrgFert led in total phenols (23.02 mg GAE/g) and ABTS

+ activity (25.91%). RecOrgFert ranked highest in DPPH activity (36.45%). In 2024 (

Table 3), phenolic profiles shifted: HM showed the highest TP (20.92 mg GAE/g), while RecOrgFert had the highest TF (22.74 mg QE/100g). DPPH activity was highest under HM (29.87%), whereas RecOrgFert and HM maintained elevated ABTS

+ values (>27%).

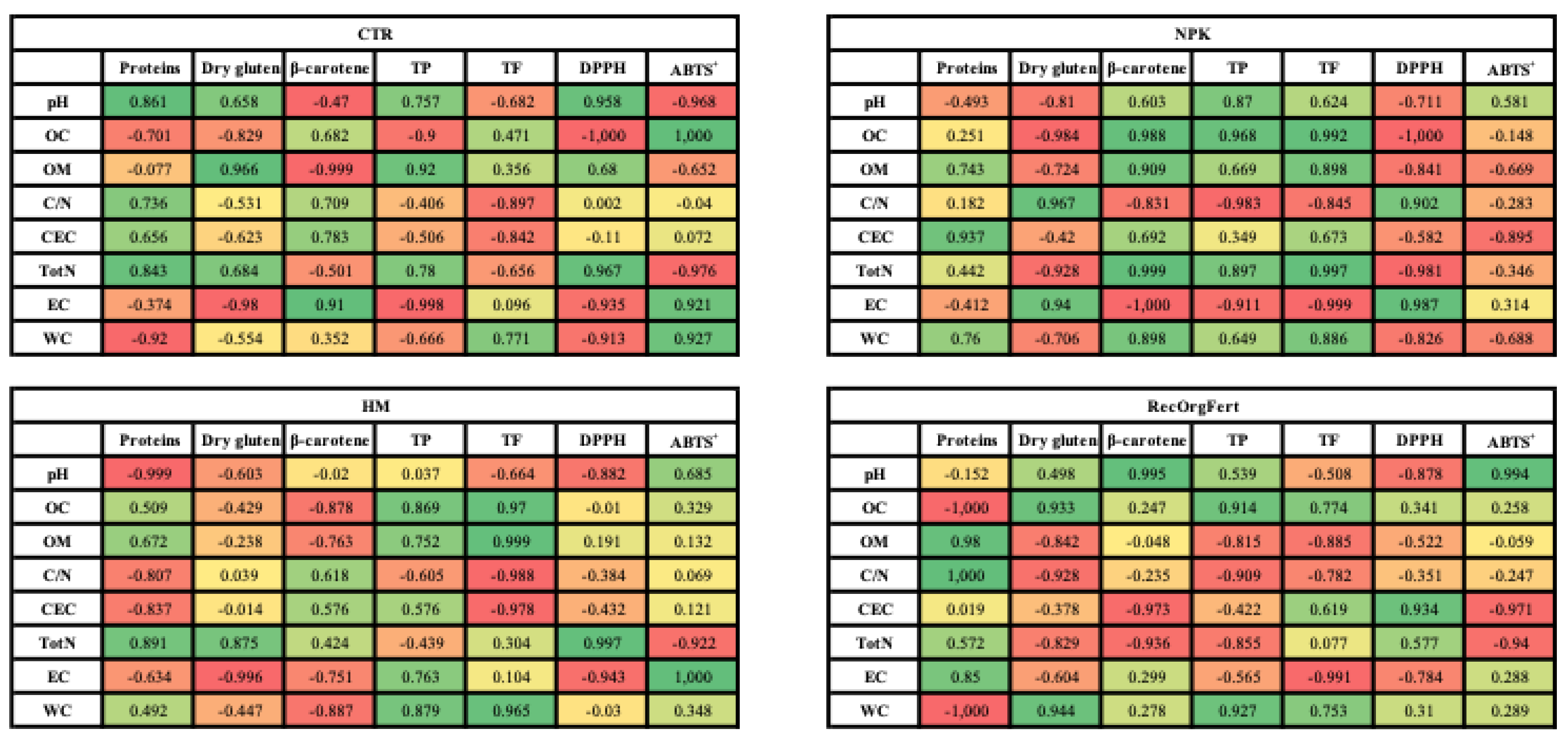

3.1.4. Soil and Grain Parameters: The Correlation

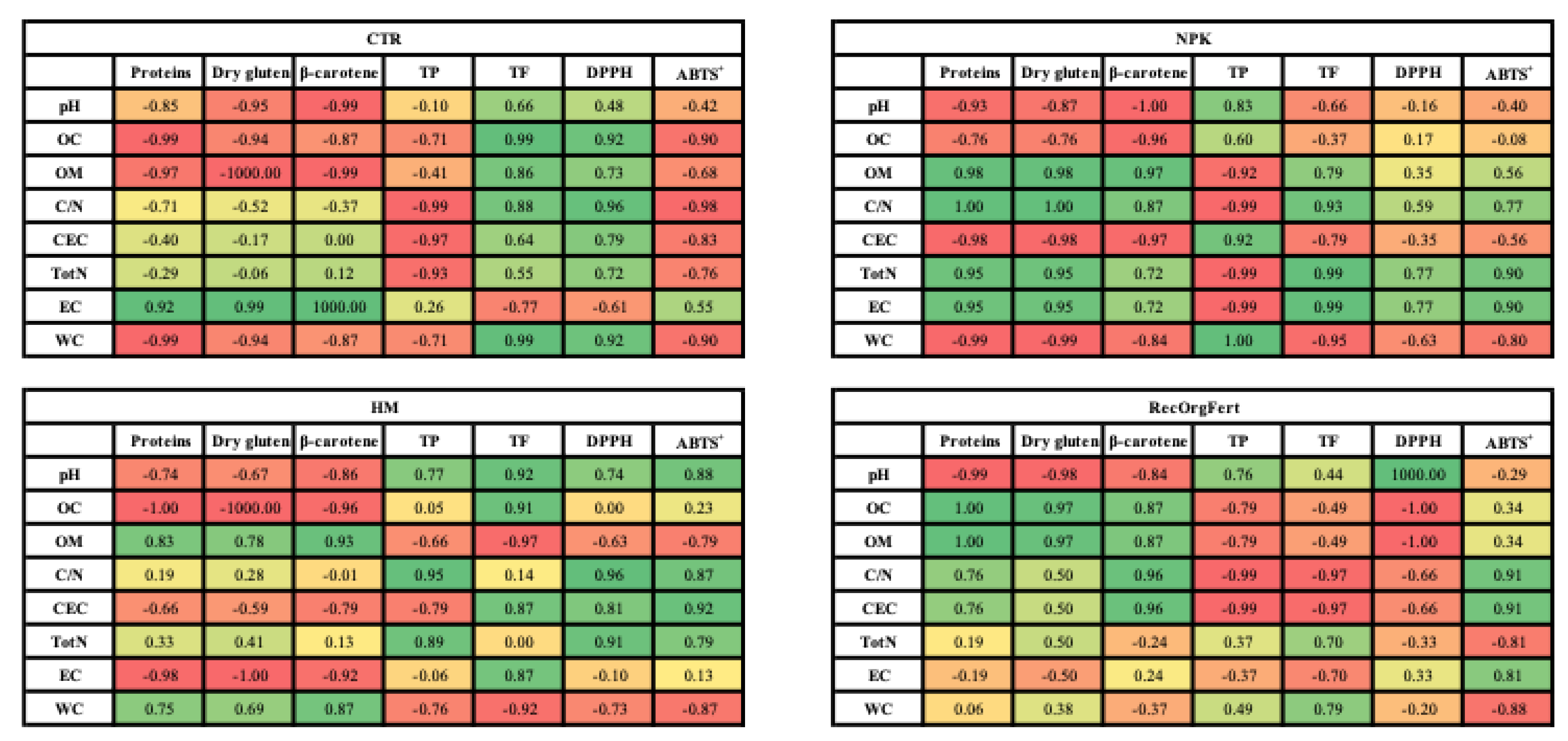

In Pearson's correlation analysis (

Figure 2), RecOrgFert showed more balanced pH-nutrient correlations than other treatments, while CTR, NPK and HM showed significant negative correlations between pH and protein content (-0.845, -0.929, -0.737 respectively); RecOrgFert maintained a moderately negative correlation (-0.690). The β-carotene/protein correlation (0.240) in RecOrgFert was positive and moderate, unlike the negative values recorded in other treatments (CTR: -0.988, NPK: -0.099, HM: -0.857). RecOrgFert showed more favourable correlations between dry matter and nutritional components and also showed positive correlations between various nutritional parameters (TP-TF: 0.756, β-carotene-ABTS

+: 0.912).

In the Pearson correlation for Greece in 2024 (

Figure 3), RecOrgFert showed higher pH-nutrient correlations than other treatments. While CTR and HM showed strong negative correlations between pH and protein content (-0.655 and -0.969, respectively), RecOrgFert maintained a moderately positive correlation (0.094). A particularly significant aspect emerged from the correlations between β-carotene and other nutritional parameters. RecOrgFert showed consistent positive correlations: β-carotene/TP (0.747), β-carotene/TF (-0.957). The CTR showed negative correlations (β-carotene/proteins: -0.702), while the NPK produced moderate but less consistent values. The ABTS

+ correlations in RecOrgFert revealed significant positive associations with several nutritional parameters (ABTS

+/TP: 0.795, ABTS

+/dry matter: 0.972). In contrast, CTR and NPK showed weaker or negative ABTS

+ correlations. RecOrgFert demonstrated more stable and positive inter-nutritional correlations. HM, despite some positive correlations, showed greater variability (significant negative correlations in some key parameters).

The comparison between the 2023 and 2024 data sets for Greece (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) provided solid validation of RecOrgFert's consistent performance. While in 2023 RecOrgFert showed a moderately negative pH-protein correlation (-0.690), in 2024 it showed a significant improvement, reaching a positive correlation (0.094). Antioxidant correlations showed a consolidating trend: ABTS

+ correlations, already favourable in 2023, strengthened further in 2024 (ABTS

+/dry matter: 0.972). In contrast, conventional treatments maintained suboptimal performance in both years.

Particularly noteworthy is the improvement achieved by RecOrgFert in the β-carotene/TP correlations, which go from negative in 2023 (0.240) to strongly positive in 2024 (0.747).

3.2. Experiments in Italy (Apulia)

3.2.1. Soil Properties

In Apulia, soil responded markedly to organic and synthetic amendments. In 2023 (

Table 4), the control had the highest OC (1.24%), followed by similarly low values in NPK, HM, and RecOrgFert (~0.94% to 0.97%), suggesting initial limitations in mineralization.

In 2024 (

Table 4), RecOrgFert and NPK significantly enhanced OC and OM (1.64% and 1.87% OC; 2.93% and 3.22% OM). HM remained lower. CEC values decreased under HM (16.5 meq/100g), while remaining high in control and NPK plots. EC was markedly higher under RecOrgFert in 2024 (0.91 dS/m).

3.2.2. Plant Growth and Yield

NPK and RecOrgFert consistently enhanced growth and productivity. In 2023 (

Table 5), plant height peaked under NPK (105 cm) and RecOrgFert (101 cm), compared to 78 cm in the control. Yield followed similar trends, with NPK (32 q/ha) and RecOrgFert (29 q/ha) far outperforming the control (22 q/ha).

In 2024 (

Table 5), plant height and seed/ear values declined in the control but remained high under NPK and RecOrgFert. Yield was highest in NPK (33.3 q/ha), followed by RecOrgFert (30 q/ha) and HM (26.3 q/ha).

Protein and gluten values improved significantly in 2024. Protein content under RecOrgFert reached 15.20%, with dry gluten around 11.80%. These results indicate superior nitrogen assimilation and grain quality under RecOrgFert. The β-carotene content in RecOrgFert in grain increased drastically from ~0.61 mg/100g in 2023 to over ~2.30 mg/100g in 2024 across all treatments.

3.2.3. Grain Biochemical Quality

In 2023 (

Table 6), RecOrgFert led in TP (22.54 mg GAE/g), DPPH (37.09%), and ABTS

+ (26.29%).

In 2024 (

Table 6), HM ranked highest for DPPH (35.21%) and RecOrgFert retained high TP and antioxidant values. TF increased notably in NPK and RecOrgFert (20.80 and 23.17 mg QE/100g).

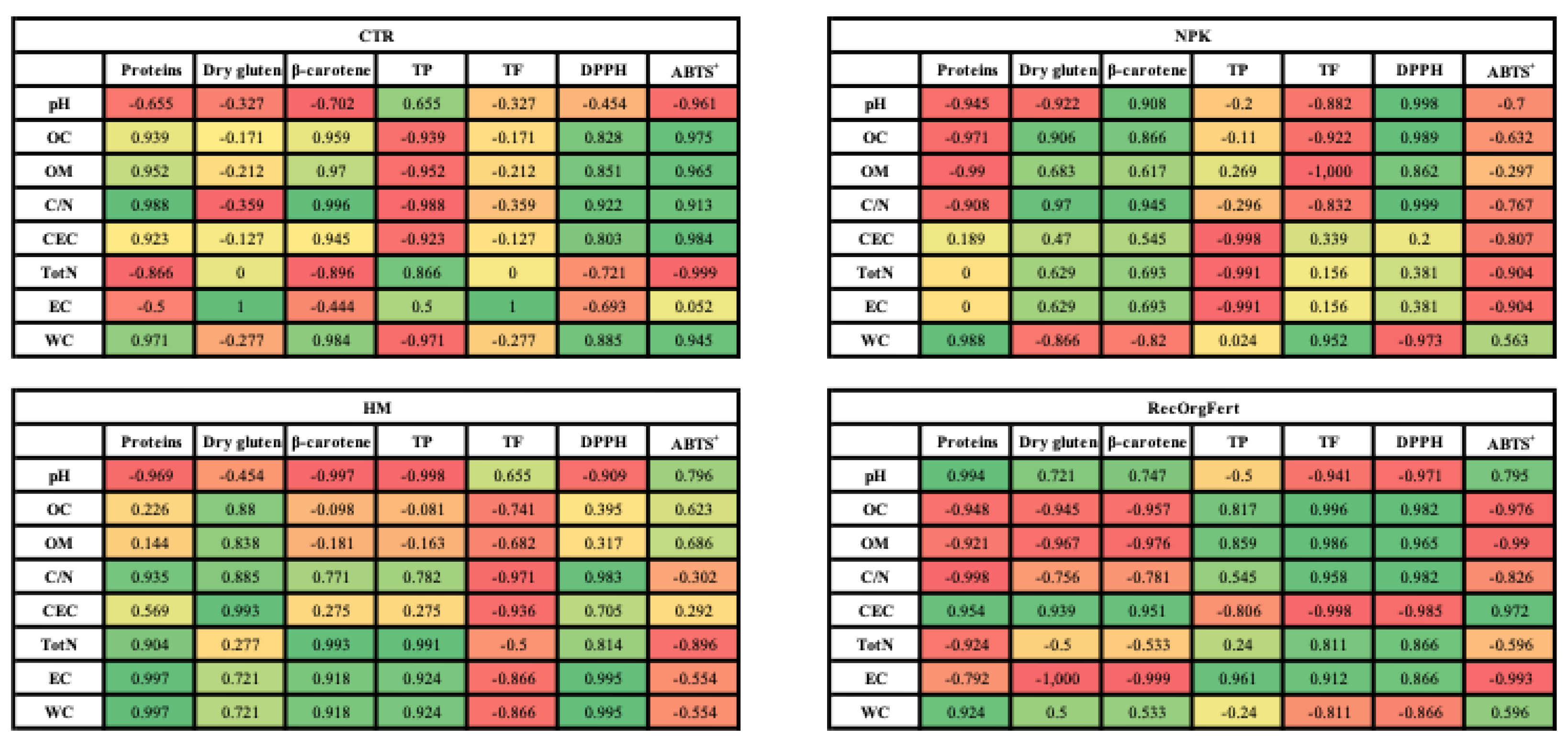

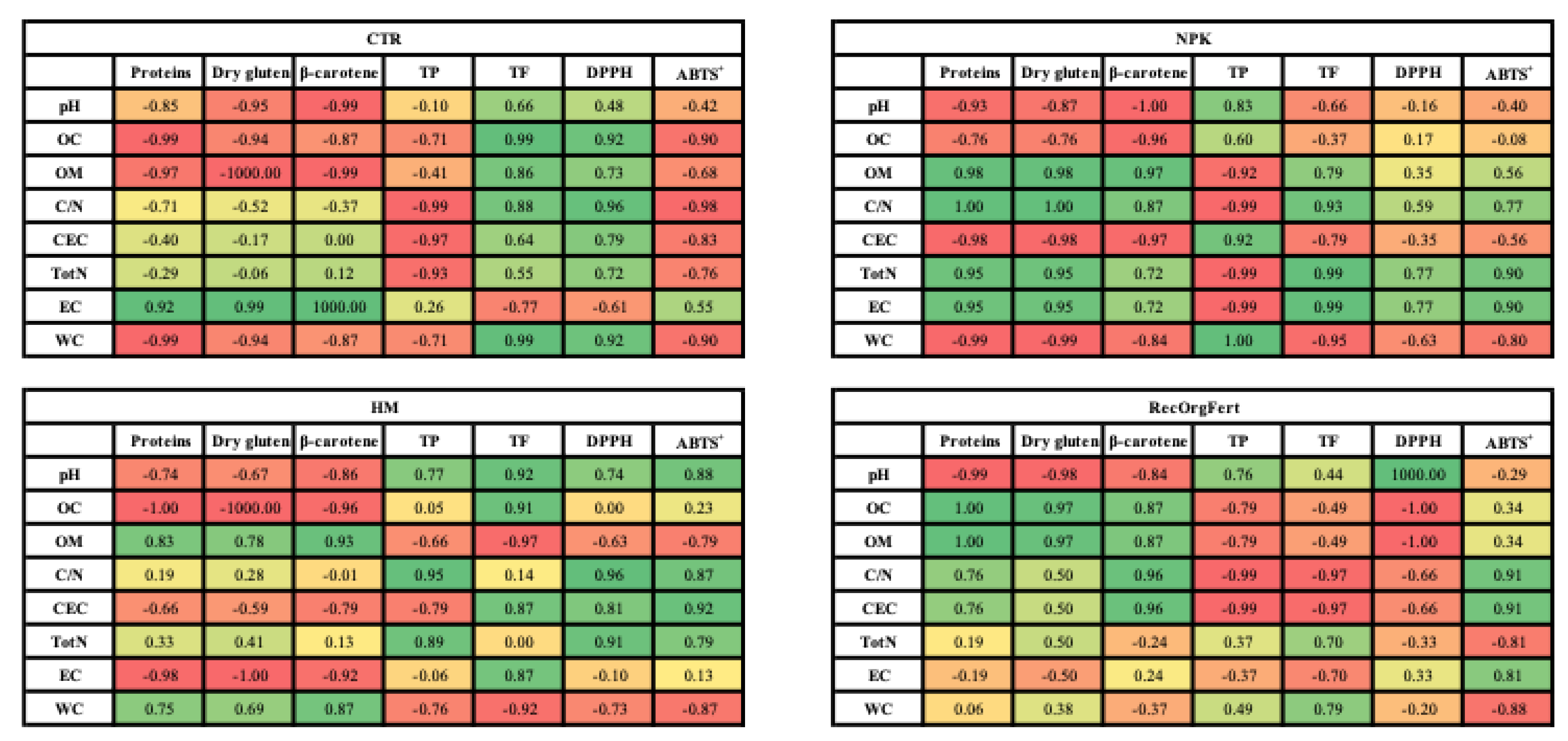

3.2.4. Soil and Grain Parameters: The Correlation

The Pearson correlation analysis in

Figure 4 revealed that RecOrgFert shows higher pH-nutrient correlations, maintaining moderately negative correlations with proteins (-0.392) and dry matter (-0.988) —values significantly more balanced than CTR (-0.533 proteins) and HM (-0.393 proteins). Notably, RecOrgFert had a positive pH-ABTS

+ correlation (0.087), unique among all treatments. RecOrgFert showed exceptionally favorable β-carotene correlations: β-carotene/TP (0.165), β-carotene/TF (-0.878), and β-carotene/ABTS

+ (-0.913), reflecting a more balanced pattern compared to other treatments. CTR displayed negative β-carotene/protein correlations (-0.997), and NPK indicated less consistent correlations. ABTS

+ correlations in RecOrgFert revealed particularly advantageous associations: ABTS

+/TP (0.087), ABTS

+/dry matter (0.425), and ABTS

+/β-carotene (-0.913). CTR and NPK showed predominantly negative or weak ABTS

+ correlations. RecOrgFert demonstrated more stable and functional inter-nutrient correlations; furthermore, TP-TF (0.794) and TP-dry matter (0.571). HM, despite some positive correlations, showed greater instability with strongly negative correlations for key parameters.

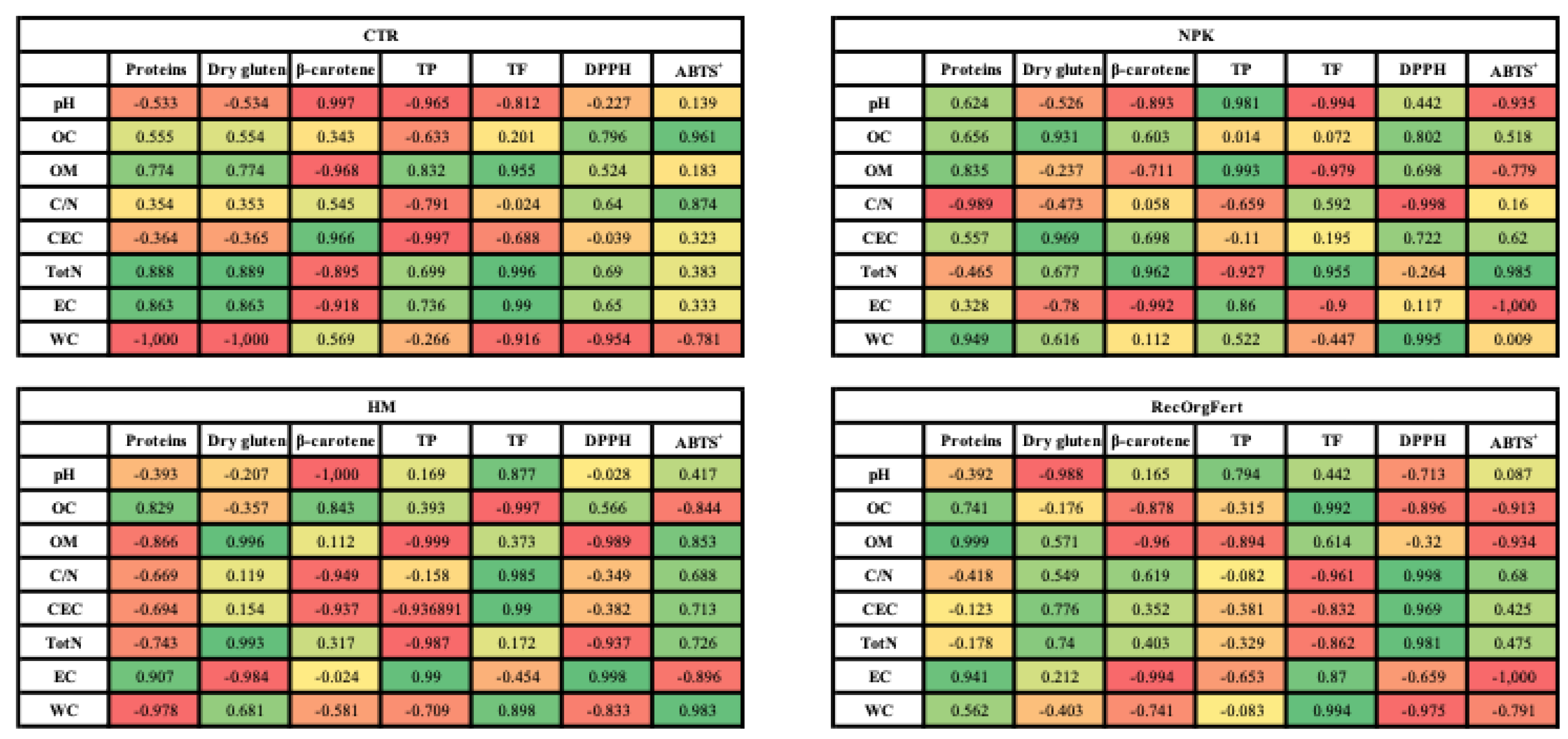

The comparison between the Italian data sets from 2023 and 2024 (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) showed that RecOrgFert achieved a progressive improvement in pH-nutrient correlations: pH-proteins from -0.392 (2023) to -0.152 (2024) and pH-ABTS

+ from 0.087 to 0.094. The most significant evolution concerns the ABTS

+ correlations: ABTS

+/TP went from 0.087 (2023) to 0.878 (2024), while ABTS

+/dry matter remained high (0.358 in 2024). The TP-dry matter correlations showed a significant improvement from 0.571 (2023) to 0.933 (2024). The β-carotenoid correlations consolidated, maintaining positive values, unlike other treatments.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion – Greece

The results from Greece demonstrated that RecOrgFert, a sustainable fertilizer composed of sulphur-bentonite and orange processing waste, can significantly enhance soil health and wheat quality in Mediterranean systems. Unlike synthetic NPK, which contributes to soil degradation, greenhouse gas emissions, and water pollution [

2,

3], RecOrgFert improved cation exchange capacity, soil organic matter, and soil moisture retention. Notably, RecOrgFert consistently promoted higher protein and gluten levels in wheat grain, likely due to its sulphur content. Sulphur is a limiting nutrient in many Mediterranean soils and is essential for the biosynthesis of sulphur-containing amino acids such as methionine and cysteine—key components of storage proteins like gluten [

26]. Moreover, sulphur plays a role in nitrogen assimilation, enhancing protein accumulation efficiency in cereals [

27]. The inclusion of citrus-derived organic material also contributed to RecOrgFert’s effectiveness. These residues are rich in polyphenols, flavonoids, and soluble carbon, which stimulate microbial activity and serve as precursors for antioxidant biosynthesis in plants [

28]. This explains the consistently high levels of phenolics, β-carotene, and antioxidant activity (DPPH, ABTS⁺) observed in RecOrgFert-treated grains.

The Pearson correlation analysis conducted in the two-year period 2023–2024 provided convincing evidence of the superior effectiveness of RecOrgFert in promoting a rhizosphere environment optimised to produce functional foods. The 2023 data showed a balanced rhizosphere, with synergistic interactions between nutritional availability and root absorption, resulting in a simultaneous improvement in yield and quality. The 2024 results confirmed these observations, showing synchronisation in nutrient absorption and positive correlations between the main bioactive components. The two-year comparison also revealed a progressively improving effect over time, suggesting stable changes in soil structure and microbial community. The consistency of the results under different seasonal and environmental conditions consolidates RecOrgFert as a reliable, sustainable fertiliser strategy suitable to produce foods with high nutritional value. These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that organic and organo-mineral fertilisation enhance soil microbial diversity and activity, promoting nutrient cycling and improving plant health and nutritional quality [

29,

30]. Improved soil structure and microbial stability are key factors contributing to the sustained release and uptake of bioactive compounds in crops [

31]. Moreover, the positive impact of biofertilisers on antioxidant capacity and phytonutrient accumulation aligns with the trends reported in recent meta-analyses on sustainable fertilisation practices [

32]. In summary, the dual contribution of sulphur and bioactive-rich organic matter in RecOrgFert led to improvements in both soil biochemistry and grain nutritional quality. These effects align with findings from similar studies on waste-derived fertilizers [

6,

7,

8], confirming RecOrgFert as a promising tool for advancing agroecological transition strategies in arid zones.

4.2. Discussion – Italy (Apulia)

In Southern Italy, RecOrgFert showed similarly beneficial outcomes. Compared to control and conventional treatments, it improved wheat yield and grain quality while enhancing key soil fertility indicators. These results are significant given the climatic vulnerability of Apulian soils, often subject to organic matter depletion and low microbial activity [

5,

33]. The sulphur content in RecOrgFert supported nitrogen assimilation and protein synthesis, reflected in the elevated grain protein and gluten content [

26]. Additionally, the citrus waste components—rich in labile carbon and secondary metabolites—stimulated soil microbial activity and contributed to higher β-carotene and phenolic content in grains [

8,

34]. Beyond yield performance, RecOrgFert provided year-to-year consistency in plant traits, indicating resilience to seasonal variability. It also contributed to higher antioxidant activity and phenolic accumulation, key indicators of grain nutritional value and shelf stability [

35,

36]. Pearson's correlation analysis conducted on Italian data from 2023–2024 confirmed the superior effectiveness of RecOrgFert in optimising the soil environment to produce functional foods with high nutritional value. The 2023 results highlighted the treatment's ability to maintain positive correlations between pH and antioxidant activity, as well as to optimise β-carotene profiles, suggesting a dual effect: enhancement of quantitative nutrient absorption and qualitative coordination between bioactive compounds. The 2024 validation reinforced this evidence, showing a refinement of nutritional correlations and a maturation of the system towards even more efficient carotenoid patterns. The two-year comparison highlighted a progressive optimisation effect over time, unlike conventional treatments, which showed instability. The increasingly robust correlations between pH and ABTS

+, together with improved inter-nutrient coordination, suggest stable structural changes in the soil-plant system. In line with what was observed in Greece, the Italian validation consolidates RecOrgFert as a reliable, progressively optimising strategy that is particularly suitable for advanced and sustainable nutritional systems in the Mediterranean context. These results align with recent research demonstrating that organic amendments and integrated fertilisation improve soil physicochemical properties and microbial community structure, which in turn enhances nutrient bioavailability and the accumulation of antioxidants and carotenoids in crops [

29]. Moreover, these findings reinforce the role of tailored fertilisation strategies such as RecOrgFert in Mediterranean agroecosystems aimed at producing foods with superior nutritional and functional qualities. These findings reinforce the role of tailored fertilisation strategies such as RecOrgFert in Mediterranean agroecosystems aimed at producing foods with superior nutritional and functional qualities.

5. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that RecOrgFert, a fertilizer derived from sulphur-bentonite and orange-processing residues, is a highly effective and sustainable solution for Mediterranean wheat systems. Across two growing seasons and two agro-ecological contexts (Greece Central Macedonia and Italy - Apulia), RecOrgFert demonstrated the ability to enhance soil fertility, increase plant productivity, and improve grain nutritional and functional quality. Unlike synthetic fertilizers such as NPK, which pose risks to environmental and soil health, RecOrgFert promoted organic matter accumulation, improved soil chemical balance (pH, EC, CEC), and supported beneficial microbial activity. These improvements translated into agronomic outcomes, including higher yields, improved nitrogen use efficiency, and significant enhancement of protein, gluten, antioxidant, and β-carotene content in wheat grain. The success of RecOrgFert is linked to its unique composition. Sulphur enhances nitrogen assimilation and protein biosynthesis, while citrus-derived residues act as a carbon source and stimulate both soil microbial communities and plant metabolic pathways related to health-promoting compounds. These effects support both plant productivity and human nutrition. Importantly, RecOrgFert’s alignment with the European Green Deal and Farm to Fork Strategy is more than theoretical. Its demonstrated capacity to recycle industrial and agri-food waste into a high-value input reinforces circularity principles while reducing dependency on external inputs. This places RecOrgFert not just as a technical alternative, but as a model for systemic innovation in Mediterranean agriculture. As climate change and soil degradation intensify, the need for regenerative inputs like RecOrgFert becomes increasingly urgent. In conclusion, RecOrgFert is not just a viable alternative to mineral fertilizers—it is a strategic resource for advancing sustainable, circular, and climate-smart agriculture in the Mediterranean and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AM Adele Muscolo), AM (Angela Maffia) and EV.; methodology, SB.; software, LS, MtO.; validation, AM (Adele Muscolo), AM (Angela Maffia) formal analysis, CM, SB, FM, KZ; investigation, FM, SB, KZ and CM; resources, AM (Adele Muscolo); data curation, KZ, LS and MtO; writing—original draft preparation, AM (Adele Muscolo), MtO; writing—review and editing, AM (Adele Musclo) and AM (Angela Maffia); visualization, MtO, LS.; supervision, AM (Adele Muscolo).; project administration, AM. (Adele Muscolo); funding acquisition, AM (Adele Muscolo). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was financially supported by the project LIFE20 ENV/IT/000229—LIFE RecOrgFert PLUS, and funded by the LIFE Programme of the European Commission.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CTR |

Control, soil without fertilizer |

| NPK |

Nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium |

| HM |

Horse manure |

| WC |

Water content |

| EC |

Electrical conductivity |

| OC |

Organic carbon |

| TotN |

Total nitrogen |

| C/N |

Carbon-nitrogen ratio |

| OM |

Organic matter |

| CEC |

Cation exchange capacity |

| TP |

Total phenols |

| TF |

Total flavonoids |

| DPPH |

2,2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile |

| ABTS+

|

2,2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato |

References

- FAO FAOSTAT Statistical Database Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, A.-N.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Antioxidant Phytochemicals for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Molecules 2015, 20, 21138–21156. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, B.; Baoyin, B.; Cui, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Cui, J. Effects of Long-Term Application of Nitrogen Fertilizer on Soil Acidification and Biological Properties in China: A Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1683. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Jabeen, N.; Farruhbek, R.; Chachar, Z.; Laghari, A.A.; Chachar, S.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmed, S.; Yang, Z. Enhancing Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Agriculture by Integrating Agronomic Practices and Genetic Advances. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1543714. [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Montemurro, F. Long-Term Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Fertility. In Sustainable Agriculture Volume 2; Lichtfouse, E., Hamelin, M., Navarrete, M., Debaeke, P., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2011; pp. 761–786 ISBN 978-94-007-0394-0.

- Badagliacca, G.; Testa, G.; La Malfa, S.G.; Cafaro, V.; Lo Presti, E.; Monti, M. Organic Fertilizers and Bio-Waste for Sustainable Soil Management to Support Crops and Control Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Mediterranean Agroecosystems: A Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 427. [CrossRef]

- Mulatu, G.; Bayata, A. Vermicompost as Organic Amendment: Effects on Some Soil Physical, Biological Properties and Crops Performance on Acidic Soil: A Review. FEM 2024, 10, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Boyd, E.; Holmes, G.; Hewavitharana, S.; Pasulka, A.; Ivors, K. The Rhizosphere Microbiome Plays a Role in the Resistance to Soil-Borne Pathogens and Nutrient Uptake of Strawberry Cultivars under Field Conditions. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 3188. [CrossRef]

- European Commission Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A New Circular Economy Action Plan – For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe.; 2020;

- Montemurro, F.; Maiorana, M.; Convertini, G.; Ferri, D. Compost Organic Amendments in Fodder Crops: Effects on Yield, Nitrogen Utilization and Soil Characteristics. Compost Science & Utilization 2006, 14, 114–123. [CrossRef]

- Pelman, A.; Vries, J.W.D.; Tepper, S.; Eshel, G.; Carmel, Y.; Shepon, A. A Life-Cycle Approach Highlights the Nutritional and Environmental Superiority of Agroecology over Conventional Farming: A Case Study of a Mediterranean Farm. PLOS Sustainability and Transformation 2024, 3, e0000066. [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, M.; Schillaci, C.; Denora, M.; Zenobi, S.; Deligios, P.A.; Santilocchi, R.; Perniola, M.; Ledda, L.; Orsini, R. Fertilization and Soil Management Machine Learning Based Sustainable Agronomic Prescriptions for Durum Wheat in Italy. Precision Agric 2024, 25, 2853–2880. [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An Examination of the Degtjareff Method for Determining Soil Organic Matter, and a Proposed Modification of the Chromic Acid Titration Method. Soil Science 1934, 37, 29.

- Kjeldahl, J. New Method for the Determination of Nitrogen. Scientific American 1883, 16.

- Kaminsky, R.; Muller, W.H. The Extraction of Soil Phytotoxins Using a Neutral EDTA Solution. Soil Science 1977, 124, 205.

- Kaminsky, R.; Müller, W.H. A Recommendation against the Use of Alkaline Soil Extractions in the Study of Allelopathy. Plant Soil 1978, 49, 641–645. [CrossRef]

- AACC Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, 2000;

- Dowell, F.E.; Maghirang, E.B.; Xie, F.; Lookhart, G.L.; Pierce, R.O.; Seabourn, B.W.; Bean, S.R.; Wilson, J.D.; Chung, O.K. Predicting Wheat Quality Characteristics and Functionality Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Cereal Chemistry 2006, 83, 529–536. [CrossRef]

- Weegels, P.L.; Hamer, R.J.; Schofield, J.D. Functional Properties of Wheat Glutenin. Journal of Cereal Science 1996, 23, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Lokesh, V.; Shang, X.; Shin, J.; Keum, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-H. Carotenoids: Dietary Sources, Extraction, Encapsulation, Bioavailability, and Health Benefits—A Review of Recent Advancements. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 795. [CrossRef]

- Box, J.D. Investigation of the Folin-Ciocalteau Phenol Reagent for the Determination of Polyphenolic Substances in Natural Waters. Water Research 1983, 17, 511–525. [CrossRef]

- Velioglu, Y.S.; Mazza, G.; Gao, L.; Oomah, B.D. Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolics in Selected Fruits, Vegetables, and Grain Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 4113–4117. [CrossRef]

- Djeridane, A.; Yousfi, M.; Nadjemi, B.; Boutassouna, D.; Stocker, P.; Vidal, N. Antioxidant Activity of Some Algerian Medicinal Plants Extracts Containing Phenolic Compounds. Food Chemistry 2006, 97, 654–660. [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Caristi, C.; Leuzzi, U.; Gattuso, G. Flavonoid Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Juices from Chinotto (Citrus × Myrtifolia Raf.) Fruits at Different Ripening Stages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3031–3036. [CrossRef]

- Castellari, M.P.; Poffenbarger, H.J.; Van Sanford, D.A. Sulfur Fertilization Effects on Protein Concentration and Yield of Wheat: A Meta-Analysis. Field Crops Research 2023, 302, 109061. [CrossRef]

- Narayan, O.P.; Kumar, P.; Yadav, B.; Dua, M.; Johri, A.K. Sulfur Nutrition and Its Role in Plant Growth and Development. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2023, 18, 2030082. [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Paredes, C.; Pérez-Espinosa, A.; Moreno-Caselles, J.; Pérez-Murcia, M.D. Agrochemical Characterisation of the Solid By-Products and Residues from the Winery and Distillery Industry. Waste Management 2008, 28, 372–380. [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Organic Amendments Enhance Soil Microbial Diversity, Microbial Functionality and Crop Yields: A Meta-Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 829, 154627. [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.C.; Grenni, P.; Onet, C.; Onet, A. Fertilization and Soil Microbial Community: A Review. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1198. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, P.; Hao, X.; Li, L.-J. Long-Term Mineral Combined with Organic Fertilizer Supports Crop Production by Increasing Microbial Community Complexity. Applied Soil Ecology 2023, 188, 104930. [CrossRef]

- Pei, B.; Liu, T.; Xue, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Liu, E.; Xing, J.; Wang, F.; Ren, X.; et al. Effects of Biofertilizer on Yield and Quality of Crops and Properties of Soil Under Field Conditions in China: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1066. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, C. Organic Fertilizer Has a Greater Effect on Soil Microbial Community Structure and Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization than Planting Pattern in Rainfed Farmland of the Loess Plateau. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Basharat, Z.; Basharat, B.; Noor, M.; Batool, Z. Citrus Waste in Agriculture: Fertilizers and Soil Amendments. In Valorization of Citrus Food Waste; Chauhan, A., Islam, F., Imran, A., Singh Aswal, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 335–349 ISBN 978-3-031-77999-2.

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Feng, D.; Duan, N.; Rong, L.; Wu, Z.; Shen, Y. Effect of Different Doses of Nitrogen Fertilization on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Brown Rice. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R.; Szczepanek, M.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Dziedziński, M.; Błaszczyk, K. Profile of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Organically and Conventionally Grown Black-Grain Barley Genotypes Treated with Biostimulant. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0288428. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) experimental Field Apulia south Italy, (b) experimental Field Thessaloniki Greece.

Figure 1.

(a) experimental Field Apulia south Italy, (b) experimental Field Thessaloniki Greece.

Figure 2.

Greece 2023: Pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato.This is a figure. Schemes follow another format. If there are multiple panels, they should be listed as: (a) Description of what is contained in the first panel; (b) Description of what is contained in the second panel. Figures should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited.

Figure 2.

Greece 2023: Pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato.This is a figure. Schemes follow another format. If there are multiple panels, they should be listed as: (a) Description of what is contained in the first panel; (b) Description of what is contained in the second panel. Figures should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited.

Figure 3.

Greece 2024: Pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato.

Figure 3.

Greece 2024: Pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato.

Figure 4.

Italy (Apulia) 2023: Pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato.

Figure 4.

Italy (Apulia) 2023: Pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato.

Figure 5.

Italy (Apulia) 2024: pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato

Figure 5.

Italy (Apulia) 2024: pearson correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between soil and grain parameters. The correlation coefficients range from -1 (strong negative correlation, in red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, in green), with the colour scale visible on the right. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon; OM = organic matter; C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity; TotN = total nitrogen; EC = electrical conductivity; WC = Soil Moisture; Proteins; Dry gluten; β-carotene; TP = total phenols; TF = total flavonoids; DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile; ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato

Table 1.

Greece 2023 and 2024: chemical and biochemical properties of soil. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon (%); OM = organic matter (%); C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity (meq/100g); Tot N = total nitrogen (%); EC = electrical conductivity (dS/m); WC = Soil Moisture (%). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1.

Greece 2023 and 2024: chemical and biochemical properties of soil. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon (%); OM = organic matter (%); C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity (meq/100g); Tot N = total nitrogen (%); EC = electrical conductivity (dS/m); WC = Soil Moisture (%). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

| 2023 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| pH |

8.0ᵃ ±0.1 |

7.9ᵇ ±0.1 |

7.9ᵇ ±0.1 |

7.9ᵇ ±0.1 |

| OC |

2.32ᶜ ±0.15 |

4.00ᵃ ±0.20 |

3.44ᵇ ±0.18 |

2.34ᶜ ±0.15 |

| OM |

4.00ᶜ ±0.25 |

6.90ᵃ ±0.30 |

5.93ᵇ ±0.28 |

4.03ᶜ ±0.25 |

| C/N |

19.33ᵇ ±1.2 |

25.00ᵃ ±1.5 |

22.93ᵃ ±1.4 |

18.00ᵇ ±1.0 |

| CEC |

12.73ᵇ ±1.0 |

10.72ᵇ ±1.1 |

13.60ᵃ ±1.2 |

10.71ᵇ ±1.0 |

| Tot N |

0.12ᵇ ±0.01 |

0.16ᵃ ±0.01 |

0.15ᵃ ±0.01 |

0.13ᵇ ±0.01 |

| EC |

0.37ᵇ ±0.03 |

0.40ᵇ ±0.02 |

0.40ᵇ ±0.02 |

0.43ᵃ ±0.02 |

| WC |

13.10ᵃᵇ ±1.5 |

11.10ᵇ ±1.3 |

12.00ᵃᵇ ±1.4 |

16.40ᵃ ±1.8 |

| 2024 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| pH |

8.0ᵃ ±0.1 |

7.9ᵇ ±0.1 |

7.7ᶜ ±0.1 |

7.6ᶜ ±0.1 |

| OC |

2.5ᶜ ±0.16 |

4.10ᵃ ±0.20 |

3.0ᵇ ±0.16 |

3.2ᵇ ±0.18 |

| OM |

4.4ᶜ ±0.28 |

7.1ᵃ ±0.35 |

5.2ᵇ ±0.28 |

5.5ᵇ ±0.30 |

| C/N |

14.2ᶜ ±1.2 |

29.3ᵃ ±1.6 |

23.4ᵇ ±1.3 |

29.0ᵃ ±1.5 |

| CEC |

22.8ᶜ ±2.0 |

23.4ᵇᶜ ±2.1 |

28.9ᵃ ±2.3 |

24.1ᵃᵇ ±2.2 |

| Tot N |

0.18ᵃ ±0.02 |

0.14ᵇ ±0.01 |

0.13ᵇ ±0.01 |

0.11ᶜ ±0.01 |

| EC |

0.82ᵃ ±0.05 |

0.50ᵇ ±0.03 |

0.57ᵇ ±0.03 |

0.44ᵇ ±0.02 |

| WC |

13.9ᵇ ±1.5 |

12.0ᵇ ±1.4 |

14.2ᵃᵇ ±1.5 |

14.9ᵃ ±1.6 |

Table 2.

Greece 2023 and 2024: plant grow parameters. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. Plant height (cm); Seed/ear; Yield (q/ha); Dry Seed (g/plant); Proteins (%); Dry gluten (% s.s.); β-carotene (mg/100g). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

Table 2.

Greece 2023 and 2024: plant grow parameters. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. Plant height (cm); Seed/ear; Yield (q/ha); Dry Seed (g/plant); Proteins (%); Dry gluten (% s.s.); β-carotene (mg/100g). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

| 2023 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| Plant height |

176.0ᵇ ±4.5 |

202.0ᵃ ±5.0 |

203.0ᵃ ±4.8 |

181.0ᵃᵇ ±4.3 |

| Seed/ear |

35ᵇ ±3 |

41ᵃ ±3 |

37ᵇ ±3 |

42ᵃ ±2 |

| Yield |

17.70ᵃᵇ ±1.8 |

19.76ᵃ ±1.5 |

17.47ᵃᵇ ±1.7 |

15.69ᵇ ±1.6 |

| Dry Seed |

0.7ᵇ ±0.1 |

1.0ᵃᵇ ±0.1 |

2.2ᵃ ±0.2 |

1.1ᵃᵇ ±0.1 |

| Proteins |

12.0ᵇ ±0.8 |

12.3ᵃᵇ ±0.9 |

10.5ᶜ ±0.8 |

15.1ᵃ ±1.0 |

| Dry gluten |

14.1ᵇ ±1.0 |

21.6ᵃ ±1.2 |

18.9ᵃ ±1.1 |

20.0ᵃ ±1.1 |

| β-carotene |

0.50ᵇ ±0.05 |

0.61ᵃᵇ ±0.06 |

0.66ᵃ ±0.07 |

0.62ᵃᵇ ±0.06 |

| 2024 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| Plant height |

161.0ᶜ ±4.0 |

190.2ᵃ ±4.5 |

186.8ᵃ ±4.2 |

173.0ᵇ ±4.1 |

| Seed/ear |

36ᵇ ±3 |

53ᵃ ±4 |

36ᵇ ±3 |

50ᵃ ±3 |

| Yield |

16.49ᵃᵇ ±0.6 |

17.51ᵃ ±0.7 |

13.87ᵇ ±1.3 |

15.22ᵃ ±0.5 |

| Dry Seed |

0.5ᵃᵇ ±0.1 |

0.4ᵇ ±0.1 |

1.1ᵃ ±0.1 |

0.6ᵃᵇ ±0.1 |

| Proteins |

12.8ᵇ ±0.9 |

14.7ᵃᵇ ±1.1 |

14.9ᵃ ±1.0 |

16.6ᵃ ±1.2 |

| Dry gluten |

18.0ᵇ ±1.2 |

20.0ᵃ ±1.1 |

17.8ᵇ ±1.0 |

23.4ᵃ ±1.3 |

| β-carotene |

2.20ᵇ ±0.20 |

2.32ᵃᵇ ±0.21 |

2.35ᵃ ±0.22 |

2.29ᵃᵇ ±0.20 |

Table 3.

Greece 2023 and 2024: analysis of wheat grown. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. TP = total phenols (mg GAE g⁻¹); TF = total flavonoids (mg QE g⁻¹); DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile (% inhibition); ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato ((% inhibition). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard error. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

Table 3.

Greece 2023 and 2024: analysis of wheat grown. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. TP = total phenols (mg GAE g⁻¹); TF = total flavonoids (mg QE g⁻¹); DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile (% inhibition); ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato ((% inhibition). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard error. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

| 2023 |

| |

CTRL |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| TP |

19.87ᶜ ± 0.85 |

21.76ᵇ ± 0.92 |

22.31ᵃᵇ ± 0.97 |

23.02ᵃ ± 1.04 |

| TF |

10.02c ± 0.47 |

18.89ᵃ ± 0.76 |

16.94ᵇ ± 0.73 |

17.62ᵃ ± 0.81 |

| DPPH |

32.85ᵇ ± 1.22 |

35.01ᵃᵇ ± 1.35 |

35.89ᵃ ± 1.33 |

36.45ᵃ ± 1.41 |

| ABTS⁺ |

23.67ᶜ ± 1.03 |

24.02ᶜ ± 1.18 |

24.88ᵇ ± 1.15 |

25.91ᵃ ± 1.26 |

| 2024 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| TP |

12.03ᵇ ± 0.56 |

11.37ᵇ ± 0.61 |

20.92ᵃ ± 1.02 |

19.65ᵃ ± 0.94 |

| TF |

11.12ᶜ ± 0.49 |

19.91ᵃ ± 0.92 |

17.41ᵇ ± 0.87 |

22.74ᵃ ± 1.03 |

| DPPH |

15.88ᶜ ± 0.88 |

23.45ᵇ ± 1.21 |

29.87ᵃ ± 1.38 |

26.12ᵃᵇ ± 1.30 |

| ABTS⁺ |

25.33ᵇ ± 1.11 |

26.12ᵃᵇ ± 1.25 |

28.15ᵃ ± 1.33 |

27.03ᵃ ± 1.19 |

Table 4.

Italy (Apulia) 2023 and 2024: chemical and biochemical properties of soil. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon (%); OM = organic matter (%); C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity (meq/100g); Tot N = total nitrogen (%); EC = electrical conductivity (dS/m); WC = Soil Moisture (%). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

Table 4.

Italy (Apulia) 2023 and 2024: chemical and biochemical properties of soil. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. pH; OC = organic carbon (%); OM = organic matter (%); C/N = carbon-nitrogen ratio; CEC = cation exchange capacity (meq/100g); Tot N = total nitrogen (%); EC = electrical conductivity (dS/m); WC = Soil Moisture (%). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

| 2023 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| pH |

7.60ᵇ ± 0.12 |

7.80ᵃ ± 0.09 |

7.70ᵃᵇ ± 0.08 |

7.80ᵃ ± 0.11 |

| OC |

1.24a ± 0.18 |

0.95b ± 0.22 |

0.94b ± 0.19 |

0.97b ± 0.26 |

| OM |

2.14a ± 0.31 |

1.64b ± 0.28 |

1.62b ± 0.24 |

1.67b ± 0.35 |

| C/N |

0.12a ± 0.015 |

0.12a ± 0.018 |

0.13a ± 0.020 |

0.09b ± 0.012 |

| CEC |

29.50ᵃ ± 3.20 |

27.90ᵇ ± 2.90 |

26.20ᵇ ± 3.40 |

19.30c ± 2.60 |

| Tot N |

0.15a ± 0.025 |

0.11b ± 0.032 |

0.12b ± 0.035 |

0.09c ± 0.028 |

| CE |

0.36a ± 0.08 |

0.34a ± 0.12 |

0.34a ± 0.11 |

0.33a ± 0.09 |

| WC |

12.93b ± 2.10 |

11.21b ± 1.95 |

12.29b ± 2.25 |

15.98ᵃ ± 2.80 |

| 2024 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| pH |

7.80ᵃ ± 0.14 |

7.80ᵃ ± 0.10 |

7.80ᵃ ± 0.11 |

7.80ᵃ ± 0.13 |

| OC |

1.34ᶜ ± 0.31 |

1.87ᵃ ± 0.42 |

0.95ᵈ ± 0.24 |

1.64a ± 0.38 |

| OM |

2.31b ± 0.12 |

3.22ᵃ ± 0.58 |

1.64ᵈ ± 0.12 |

2.93a ± 0.41 |

| C/N |

0.14ᵇ ± 0.022 |

0.10ᶜ ± 0.016 |

0.20ᵃ ± 0.028 |

0.12ᵇ ± 0.019 |

| CEC |

29.50ᵃ ± 2.10 |

27.10a ± 1.60 |

16.50c ± 1.40 |

26.1a ± 1.80 |

| Tot N |

0.19ᵃ ± 0.045 |

0.18ᵃ ± 0.038 |

0.19ᵃ ± 0.042 |

0.20ᵃ ± 0.048 |

| CE |

0.71ᵇ ± 0.15 |

0.69ᵇ ± 0.13 |

0.70ᵇ ± 0.14 |

0.91ᵃ ± 0.18 |

| WC |

14.01a ± 1.40 |

12.12a ± 1.15 |

13.89a ± 2.50 |

13.97a ± 2.65 |

Table 5.

Italy (Apulia) 2023 and 2024: plant parameters. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. Plant height (cm); Seed/ear; Yield (q/ha); Dry Seed (g/plant); Proteins (%); Dry gluten (% s.s.); β-carotene (mg/100g). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

Table 5.

Italy (Apulia) 2023 and 2024: plant parameters. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. Plant height (cm); Seed/ear; Yield (q/ha); Dry Seed (g/plant); Proteins (%); Dry gluten (% s.s.); β-carotene (mg/100g). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

| 2023 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| Plant height |

78.0ᶜ ± 4.50 |

105.00ᵃ ± 8.30 |

84.0ᵇ ± 4.20 |

101.0ᵃ ± 7 |

| seed/ear |

36.0b ± 4.20 |

43.0a ± 5.80 |

37.0b ± 4.90 |

43.0a ± 6.10 |

| Yield |

22.00ᵈ ± 3.10 |

32.00ᵃ ± 4.50 |

24.00ᶜ ± 3.60 |

29.00ᵇ ± 3.80 |

| Dry See |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.045 |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.038 |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.041 |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.042 |

| Proteins |

10.50a ± 1.80 |

11.30a ± 2.20 |

10.80a ± 2.10 |

10.60a ± 1.95 |

| Dry Gluten |

7.00a ± 1.20 |

7.40a ± 1.45 |

6.80a ± 1.25 |

6.90a ± 1.30 |

| β-carotene |

0.52a ± 0.085 |

0.63a ± 0.12 |

0.65a ± 0.11 |

0.64a ± 0.095 |

| 2024 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| Plant height |

60.3c ± 7.80 |

89.6ᵃ ± 7.40 |

72.5b ± 5.30 |

87.7a ± 6.80 |

| seed/ear |

38.0b ± 5.20 |

53.0ᵃ ± 7.30 |

35.0b ± 4.60 |

51.0ᵃ ± 6.90 |

| Yield |

20.0b ± 1.90 |

33.3ᵃ ± 4.70 |

26.3a ± 2.70 |

30.0a ± 2.20 |

| Dry Seed |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.052 |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.046 |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.044 |

0.80ᵃ ± 0.049 |

| Proteins |

14.50ᵃ ± 2.60 |

14.80ᵃ ± 2.85 |

14.80ᵃ ± 2.75 |

15.20ᵃ ± 3.10 |

| Dry Gluten |

12.10ᵃ ± 2.20 |

12.00ᵃ ± 2.35 |

11.70ᵃ ± 2.00 |

11.80ᵃ ± 2.10 |

| β-carotene |

2.23ᵃ ± 0.28 |

2.31ᵃ ± 0.32 |

2.30ᵃ ± 0.29 |

2.34ᵃ ± 0.35 |

Table 6.

Italy (Apulia) 2023 and 2024: analysis of wheat grown. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. TP = total phenols (mg GAE g⁻¹); TF = total flavonoids (mg QE g⁻¹); DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile (% inhibition); ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato ((% inhibition). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard error. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

Table 6.

Italy (Apulia) 2023 and 2024: analysis of wheat grown. CTR (control) = soil without fertilizer; NPK = nitrogen – phosphorus – potassium; HM = horse manure; RecOrgFert = bentonite sulphur + orange pomace. TP = total phenols (mg GAE g⁻¹); TF = total flavonoids (mg QE g⁻¹); DPPH = 2.2-difenil-1-picrilidrazile (% inhibition); ABTS+ = 2.2'-azino-bis-3-etilbenzotiazolin-6-solfonato ((% inhibition). Data are the means of three replicates ± standard error. Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (Turkey’s test. p ≤ 0.05).

| 2023 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| TP |

20.50ᶜ ± 0.88 |

22.41ᵃᵇ ± 0.95 |

22.25ᵇ ± 0.93 |

22.54ᵃ ± 1.02 |

| TF |

9.48ᶜ ± 0.41 |

19.76ᵃ ± 0.82 |

17.55ᵇ ± 0.73 |

18.31ᵃ ± 0.77 |

| DPPH |

33.99ᵇ ± 1.25 |

34.95ᵇ ± 1.29 |

36.54ᵃ ± 1.31 |

37.09ᵃ ± 1.34 |

| ABTS⁺ |

24.13ᵇ ± 1.08 |

23.88ᵇ ± 1.15 |

25.08ᵃᵇ ± 1.17 |

26.29ᵃ ± 1.21 |

| 2024 |

| |

CTR |

NPK |

HM |

RecOrgFert |

| TP |

11.47ᶜ ± 0.52 |

11.09ᶜ ± 0.58 |

21.19ᵃ ± 1.01 |

20.53a ± 0.96 |

| TF |

10.55ᶜ ± 0.46 |

20.80ᵃ ± 0.94 |

16.87ᵇ ± 0.88 |

23.17ᵃ ± 1.01 |

| DPPH |

14.95ᶜ ± 0.85 |

22.93ᵇ ± 1.17 |

35.21ᵃ ± 1.39 |

35.25a ± 1.26 |

| ABTS⁺ |

24.82ᵇ ± 1.10 |

25.80ᵇ ± 1.13 |

27.44ᵃ ± 1.24 |

28.55a ± 1.19 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).