1. Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have a long history of application in fermented foods due to their beneficial influence on nutritional, organoleptic, and shelf-life characteristics. Lactic acid fermentation is one of the most extensively investigated processes because of the significant application potential of lactic acid bacteria biomass in the food, chemical, and pharmaceutical industries. LAB have traditionally been the main probiotics used in food processing as starter cultures, pharmaceuticals, and biological control agents. More recently, the enormous relevance currently attributed to the beneficial intestinal microbiome for human health has led to increased interest in lactic acid bacteria.The nutraceutical industry is actively promoting the use of

Lactobacillus in food as probiotics [

1,

2,

3]. Nutraceuticals are substances that provide medical or health-promoting benefits, including the prevention and treatment of diseases, such as food supplements, herbal products, probiotics, and prebiotics, which are now of great importance to boththe pharmaceutical and food industries [

4,

5].

Native Andean tubers 'Andean treasures' play a crucial role in the nutrition and economy of farmers in the Puna region of Argentina. Since ancient times, they have been used for nutritional and medicinal purposes. Andean tubers grow at high altitudes under challenging conditions of drought, freezing temperatures, and UV exposure, holding potential for exportation and further research in terms of adaptation and use in other regions of the world. They are drought-resistant and adaptable to various agro-climatic conditions [

6]. Many of them are categorized as neglected and underutilized species despite offering high vitamin, micronutrient, starch content, dietary fibres, and antioxidants associated with medicinal properties and health benefits [

7]. Moreover,

S. tuberosum peels exhibit healing properties for wounds and burns [

8,

9].

Andean potatoes possess high antioxidant and antimicrobial potential for effective nutraceutical formulations, owing to the presence of antioxidant polyphenols, including chlorogenic acid, caffeoylquinic acid and its derivatives, flavonoids, flavonones, anthocyanins, and coumarins, among others. Oca potatoes, mashua, ulluco, and other high-mountain tubers constitute natural sources of antioxidants, establishing their value as functional foods. Many of their constituents can neutralize free radicals, which are important in the fight against cancer, cardiovascular, and neurovascular diseases. They also exhibit antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, anticarcinogenic, antihyperglycemic, antiallergic, antithrombotic, and vasodilatory properties [

7,

10,

11]. Additionally, potato peels represent a significant agro-industrial byproduct with notable potential for valorization due to their rich composition of bioactive compounds [

12].

In this study, we address the design of innovative Lactobacillus culture media based on natural products to improve the biotechnological properties of bacteria. Chemical and spectroscopic characterization of the phytochemicals obtained from peels of different varieties of edible tubers from the Argentinian Puna, such as Oxalis tuberosa Mol. (Oxalidaceae), Ullucus tuberosus Caldas (Basellaceae) and Solanum tuberosum L. subsp. andigena (Solanaceae) were individually evaluated.

This research provides insights into the sustainable utilisation of these peels as a natural source of selective promoters of a probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain and of an environmental isolate of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 from ovine origin. These phytoextracts, added in small amounts into culture media, do not stimulate the development of the tested pathogenic bacteria. In addition, the bio-detoxifying power and genetic identification of the novel indigenous strain CO1 as well as its technological capacities were also determined for the first time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Natural Product Source

Tubers were collected in the high mountain plateau of the Puna desert (2500-4000 m) and obtained in the Feria Nacional de la Papa Andina (Alfarcito, Salta, Argentina). Species were identified and classified by Dr María Inés Mercado (Foundation Miguel Lillo) in collaboration with Dr Andrea Clausen and Dr Ariana Digilio of the Banco Activo de Germoplasma EEA-INTA-Balcarce, Argentina.

The selected species were identified by their morphological characteristics as Oxalis tuberosa Mol. var. oca rosa and var. oca blanca, Ullucus tuberosus Caldas, and five varieties of Solanum tuberosum L. subsp. andigena var. miskila azul or negra, var. miskila colorada, var. chila, var. cuarentona and var. castilla blanca.

2.1.1. Natural Product Extraction

Thirty-two dried extracts were prepared from peels of O. tuberosa (var. oca rosa and oca blanca), U. tuberosus, and S. tuberosum L. subsp. andigena (var. miskila azul or negra, miskila colorada, cuarentona, chila, and castilla blanca).

Full ethanol extract obtained by maceration method using 96% ethanol solvent (EE), and aqueous extract obtained by infusion at 50 ˚C during 30 min (AE), and their sub-extracts obtained by partition of AE with ethyl acetate (EAS) and ethanol (ES) were prepared from each sample. Then, the solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator, and the extraction yields were calculated and listed in

Table 1.

2.2. Bacterial Strains

2.2.1. Probiotic and Environmental Bacteria

A food origin-probiotic bacterium,

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATCC 10241 [

13], and a wild isolate of

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 found in the soil and healthy sheep stool from a farm were employed for the bioassays. The culture media employed were PTYg (15 g/ L peptone, 10 g/ L triptone, 10 g/ L yeast extract, and 5 g/ L glucose, pH 6.0 ± 0.1), and PTYg modified by the addition of natural products in concentrations of 25-100 µg/mL (pH 6.0 ± 0.2). Stock cultures were preserved in appropriate PTYg broth containing 20% glycerol (v/v) (−80 °C).

2.2.2. Pathogenic Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria included Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, E. coli O157:H12, and Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium ATCC 14028. While indigenous pathogenic isolates of S. corvalis (SF2) and S. cerro (SF16), provided by Dr María Ángela Jure (Professor at Cátedra de Bacteriología, Facultad de Bioquímica, Química y Farmacia, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina), were also employed. All bacteria were biofilm-forming strains.

2.3. Genotypic Characterization of Novel Isolate

The wild isolate's entire genomic DNA was extracted using a PrestoTM Mini gDNA Bacteria Kit Quick Protocol from Geneaid in accordance with the instructions. Two primers were used to amplify the 16s rDNA, one of them was 27F (5'-GTGCTGCAGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and the other was 1492R (5'-CACGGATCCTACGGGTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') [

14]. The thermocycler from My Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was utilized to conduct the polymerase chain reaction. For the PCR mixture, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl 2.5 µL 10x reaction buffer, 100 µmol/L dNTPs, 0.5 µmol/L of each primer, 4 mL bacterial DNA, and 1.5 U Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). An initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, hybridization at 52 °C for 2 min, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min with a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min was performed. Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis (80 v) on a 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel stained with SYBR Gel DNA Safe Stain (Invitrogen) in 1x TAE buffer (40 mmol/L

Tris-acetate, 1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8).

MACROGEN Inc. (Korea) sequenced the PCR products after purifying them with the PCR Purification AccuPrep Kit (Bioneer, USA). 16S rRNA gene sequences were edited using Chromas Pro software (version 1.5, Technelysium Pty. Ltd., 2003-2009) and analyzed with DNAMAN software (version 2.6, Lynnon-Biosoft).

To determine sequence homologies, they were compared the obtained sequences with those from the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database using BLAST software (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and determined which is the closest relative.

To determine sequence homologies, these were compared to the obtained sequences with those from the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database using BLAST software (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and determined which is the closest relative.

The 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of the isolated strains were deposited in the GenBank.

2.4. Bacterial Growth

In a microtiter polystyrene plate with 96 wells, the diluted overnight culture (105 CFU/mL) was added to each one of the wells.

Extracts of plant species (EE, AE, EAS, ES) were assayed (n= 6) at 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL, dissolved in DMSO-H2O 50:50. Control cultures contained the diluted culture (180 µL) and 20 µL of the solution of DMSO-H2O.

The bacterial cells were exposed to a maximum of 0.25% DMSO and were cultured in liquid medium at 37 °C. Bacterial growth was measured as absorbance at 600 nm using a microplate reader (Power Wave XS2, Biotek, VT, USA).

2.5. Biofilm Biomass Quantification

Crystal violet-based assay was used to quantify the development of biofilm on a polystyrene microplate, which was based on a protocol published [

15] with some adaptations for the performed micro-method.

The removal of crystal violet binding to biofilm from each well was done using 200 µL of 96% ethanol for 15 min at 37 °C with shaking for a total of 15 min.

A microtiter plate reader (Power Wave XS2, Biotek, Vermont, USA) was used to determine the absorbance (560 nm) of ethanol solutions

The results of this bioassay, expressed as a percentage, were calculated using the following formula:

Biofilm formation (%) = As / A0 x 100, where A0 is the absorbance of the control, and As is the absorbance of each sample.

2.5.1. Specific Biofilm Index Determination

The specific biofilm index [

16], which expresses the amount of biofilm that each bacterium forms, was determined as the relationship between the formed biofilm (measured at 560 nm, in our case) and the bacterial growth (measured at 600 nm) after 24 h of incubation, according to the following formula:

Specific biofilm index = A560 nm/A600 nm, where A is the absorbance measurement.

2.6. Surfactant Activity

The oil dispersion test is a rapid and sensitive method for detecting surface active substances. Thus, it is a useful tool for discovering the LAB surfactant activities. After 24 h of incubation, the bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation (3500 rpm, 15 min at 4 °C, 2193 ×

g), and the supernatants were filtered through a 0.22 µm pore size filter to obtain cell-free supernatants. For the assay, 20 µL of mineral oil was placed in a crystallizer of 250 mm in diameter, containing deionized water (100 mL), over millimeter paper according to the protocol developed by Cartagena et al. (2021) [

17]. Then, 10 µL of each cell-free supernatant was placed in the center of the oil film. If a surfactant is present, the oil is displaced, and a clearing zone is formed. The diameter of this clearing zone on the surface of the oil correlates with the biosurfactant content and its activity [

17,

18,

19]. The clear halos (mm) visualized under visible light were measured fivefold compared to the control. Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as a reference standard. The PTYg and modified PTYg media (both without bacteria) showed no activity.

2.7. Chemical and Spectrochemical Analysis

Qualitative reactions with ferric chloride solution (1%) and aluminium chloride solution (5%) were preliminary implemented to characterize phenolic and flavonoid compounds [

20] in the phytoextracts selected from a bio-guided study. These reactions are often used in organic chemistry to identify the phenolic functional group. UV spectroscopy analysis was also carried out. This technique allows the detection of conjugated double bonds, aromatic compounds and

α,

β-unsaturated carbonyls, according to the absorption maxima [

21]. UV spectra were obtained using a Shimadzu UV-Vis 160 A spectrometer (Shimadzu, USA). Extracts were dissolved in EtOH (spectroscopic grade, Sigma-Aldrich, Argentina) and placed in quartz cuvettes for UV measurements.

2.8. Lactobacilli Fermentation into Modified Media

LAB were statically grown in 10 mL of PTYg supplemented with a solution of phenol at 100 μg/mL (pH 6.0 ± 0.2) for 7 days at 37 ± 1 °C in borosilicate glass tubes (10 mL) in duplicate. In the same way, o-phenyl phenol (OPP) was incorporated to the L. paracasei CO1 culture medium (PTYg) modified by adding EAS of O. tuberosa var. oca rosa (25 µg/mL, pH 6.0 ± 0.1), which was selected for its bioactivity and also evaluated. The inoculum was adjusted to 106 CFU/mL. Control experiments (without the addition of phenolic compounds or O. tuberosa EAS) were also performed.

2.9. Specific Enzyme Inhibition

The enzymatic activity of phenol oxidases in the

L. paracasei CO1 culture was investigated with the oxidase test (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and corroborated by the addition of phenol solutions in concentrations ranged from 5–50 μg/mL, and combinations with dithiothreitol and ascorbic acid (as reducing agents) that were individually incorporated into the cultures in order to determine the enzyme inhibition [

17,

22].

2.10. Electron Microscopy

To determine the cell morphology of

L. paracasei, the Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed. Phenol was chosen as a representative mutagenic substance [

23] for the treatment. The samples (T and C) were fixed in Karnovsky's solution (formaldehyde 2.66%, glutaraldehyde 1.66%, and phosphate buffer 0.1 M, pH 7.4) and incubated overnight at 4 °C for morphological and ultrastructural studies. The fixed samples were washed and dehydrated by routine technique. ZEISS Crossbeam 340 (Carl ZEISS NTS, Oberkochen, Germany) field emission scanning electron microscope was used to examine the samples previously coated with gold.

2.11. TLC and GC-MS Analysis

From cultures modified with a solution of O. tuberosa EAS (25 µg/mL) after seven days of incubation, the added mutagenic compounds (PhOH and OPP, separately) were extracted and analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC), using SiO₂ plates (GF254, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), CHCl₃:CH₃COOC₂H5 (92.5:7.5%), as mobile phase, and UV radiation to detect chromophores (such as phenols). Finally, an analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was performed.

A Thermo Scientific TSQ 9000 triple quadrupole GC-MS/MS system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a DB-5 capillary column (5% phenyl-methylpolysiloxane, film thickness, 0.25 μm, inner diameter, 0.25 mm) was employed. The initial temperature of the column was 60 °C for 3 min. A temperature program was applied, ranging from 60 °C to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, followed by a final hold at 300 °C for 5 min. Carrier gas was helium (flow 1 mL/min). The main volatile constituents were determined by comparing their mass spectra with those of the WILEY/NIST mass spectral database (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and with authentic standards.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of a Novel Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei Strain

Based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the isolated strain, the comparative analysis using different databases (BLAST, NCBI, and RDP) allowed the identification of a species with a high identity score. This sequence was deposited in GenBank, making it publicly available for further research.

The isolated strain Lacticaseibacillus paracasei was lyophilized and incorporated into the LIVAPRA strain collection with the CO1-LVP105 code (Access number GenBank: PV763827.1).

3.1.1. Origin

1 agtcgaacga gttctcgttg atgatcggtg cttgcaccga gattcaacat ggaacgagtg

61 gcggacgggt gagtaacacg tgggtaacct gcccttaagt gggggataac atttggaaac

121 agatgctaat accgcataga tccaagaacc gcagggttct tggctgaaag atggcgtaag

181 ctatcgcttt tggatggacc cgcggcgtat tagctagttg gtgaggtaat ggctcaccaa

241 ggcgatgata cgtagcccaa ctgagaggtt gatcggccac attgggactg agacacggcc

301 caaactccta cgggaggcag cagtagggaa tcttccacaa tggacgcaag tctgatggag

361 caacgccgcg tgagtgaaga aggctttcgg gtcgtaaaac tctgttgttg gagaagaatg

421 gtcggcagag taactgttgt cggcgtgacg gtatccaacc agaaagccac ggctaactac

481 gtgccagcag ccgcggtaat acgtaggtgg caagcgttat ccggatttat tgggcgtaaa

541 gcgagcgcag gcggtttttt aagtctgatg tgaaagccct cggcttaacc gaggaagcgc

601 atcggaaact gggaaacttg agtgcagaag aggacagtgg aactccatgt gtagcggtga

661 aatgcgtaga tatatggaag aacaccagtg gcgaaggcgg ctgtctggtc tgtaactgac

721 gctgaggctc gaaagcatgg gtagcgaaca ggattagata ccctggtagt ccatgccgta

781 aacgatgaat gctaggtgtt ggagggtttc cgcccttcag tgccgcagct aacgcattaa

841 gcattccgcc tggggagtac gaccgcaagg ttgaaactca aaggaattga cgggggcccg

901 cacaagcggt ggagcatgtg gtttaattcg aagcaacgcg aagaacctta ccaggtcttg

961 acatcttttg atcacctgag agatcaggtt tccccttcgg gggcaaaatg acaggtggtg

1021 catggttgtc gtcagctcgt gtcgtgagat gttgggttaa gtcccgcaac gagcgcaacc

1081 cttatgacta gttgccagca tttagttggg cactctagta agactgccgg tgacaaaccg

1141 gaggaaggtg gggatgacgt caaatcatca tgccccttat gacctgggct acacacgtgc

1201 tacaatggat ggtacaacga gttgcgagac cgcgaggtca agctaatctc ttaaagccat

1261 tctcagttcg gactgtaggc tgcaactcgc ctacacgaag tcggaatcgc tagtaatcgc

1321 ggatcagcac gccgcggtga atacgttccc gggccttgta cacaccgccc gtcacaccat

1381 gagagtttgt aacacccgaa gccggtggcgt

3.2. Effects of Tuber Peel Extracts Added into Culture Media on the Non-Pathogenic Bacteria Development

3.2.1. Food Origin-Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum ATCC 10241

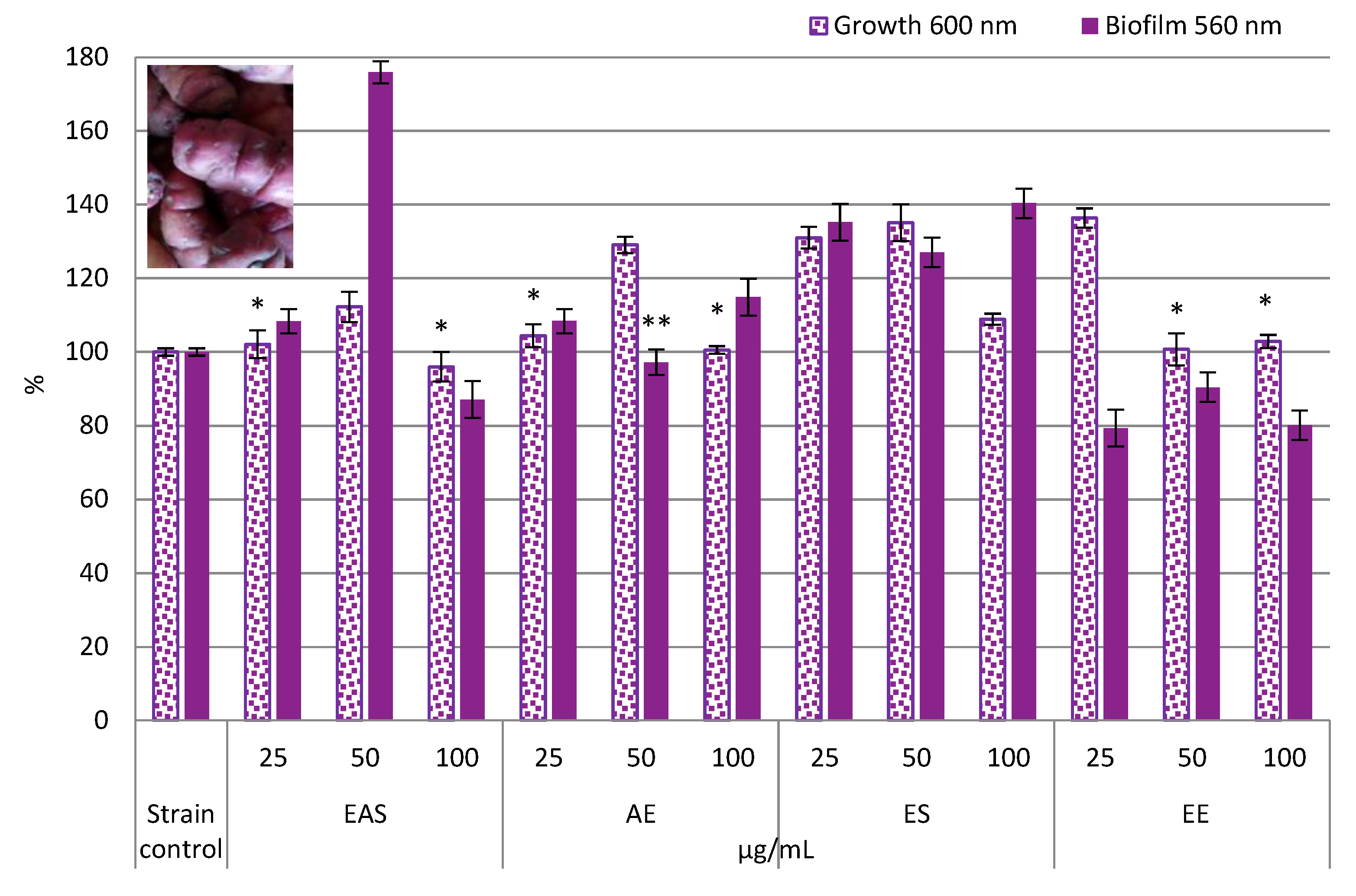

In our study, all natural products derived from Andean tuber peels were unable to inhibit planktonic growth and biofilms of the food-derived probiotic Lp. plantarum ATCC 10241, when they were added to the culture medium. Conversely, the oca rosa EAS (50 µg/mL) addition stimulated biofilm formation by 75.94% after 24 h of incubation (

Figure 1A); while S. tuberosum subsp. andigena var. chila extracts, ES (100 µg/mL) and EE (50 µg/mL), did it in a 69.31% and 50.22%, respectively. In the case of ES from the variety blanca, the biofilm increment was 61.22% at the highest concentration of 100 µg/mL. Likewise, the best growth promoting effects were determined with AE (100 µg/mL) and ES (25 µg/mL) of oca blanca with increases of 59.94% and 54.16%, respectively (

Figure S1B-H, supplementary material).

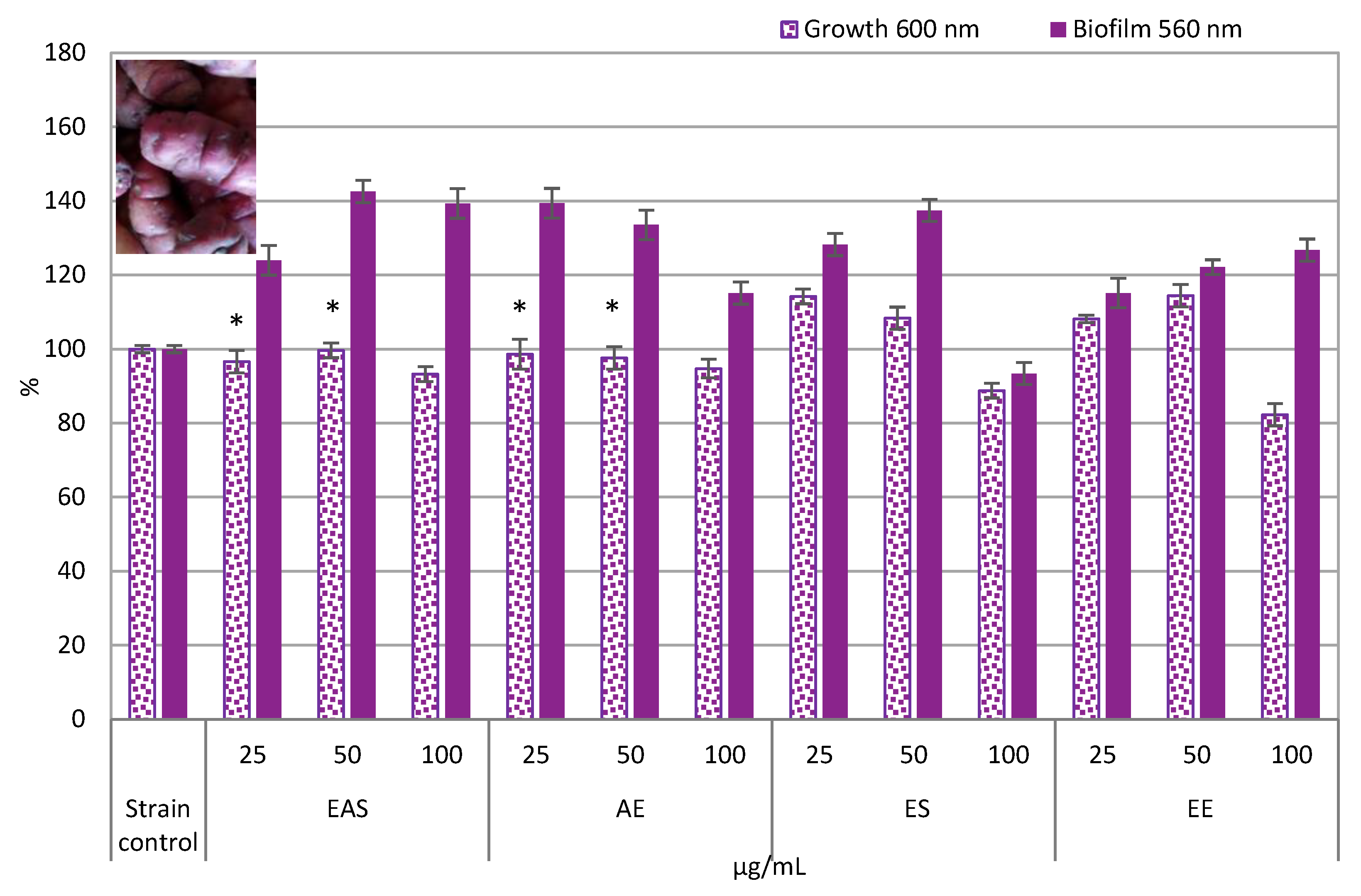

3.2.2. Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei CO1

In line with the results obtained in our study of the Lp. plantarum ATCC 10241 strain, many extracts demonstrated potential as L. paracasei CO1 growth and biofilm promoters (p < 0.05). The highest levels of biofilm stimulation were determined when the oca rosa natural products, EAS at 50 µg/mL (43%) and AE at 25 µg/mL (39%) were added into the culture media (

Figure 2A). The aqueous extract of U. tuberosus (50 µg/mL) also increased biofilm biomass reaching 36.19%. At the maximum concentration of 100 µg/mL, EE and AE of miskila colorada stimulated 62.27% and 51.52%, respectively. Finally, increases of 40.52% and 38.59% with EE of cuarentona and ES of chila were observed at 100 µg/mL (

Figure S2B-H, supplementary material).

Regarding the growth promotion of this strain, AE, EE, EAS (50 µg/mL), and ES (25 µg/mL) from the

oca blanca peels strongly increased bacterial growth (60.86%, 54.72%, 54.39%, and 54.97%, respectively); while the

miskila negra EAS (25 µg/mL) produced a growth augmentation of 46.10% (

Figure S2B-H).

It is important to note that the Andean tubers` extracts did not exert inhibitory effects on the LAB bacteria. Only

oca rosa and

chila phytochemicals at the highest concentration (100 µg/mL) weakly reduced the

L. paracasei CO1 growth (up to 17%) with respect to the unmodified control culture (

p < 0.05). In comparison, significant reductions in biofilm formation (≥ 50%) were only produced by

chila ES (66.72%) and

miskila colorada AE (50%) in concentrations of 25 µg/mL, as shown in

Figure S2B-H (supplementary material). However, these latter phytoextracts at 100 µg/mL increased biofilm biomass by 38.59%, and 51.52% (respectively) due to a likely dose-dependent stress effect, as previously reported for other natural products [

22].

Figure 2.

A. Effects of O. tuberosa var. oca rosa on the Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 cultures. EAS: Ethyl acetate sub-extract. AE: Aqueous extract. ES: Ethanol sub-extract. EE: Ethanol extract. All experiments (n= 6) showed significant differences with respect to control (p < 0.05), except for bars with asterisks.

Figure 2.

A. Effects of O. tuberosa var. oca rosa on the Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 cultures. EAS: Ethyl acetate sub-extract. AE: Aqueous extract. ES: Ethanol sub-extract. EE: Ethanol extract. All experiments (n= 6) showed significant differences with respect to control (p < 0.05), except for bars with asterisks.

Overall, phytochemicals concentrated in EAS, AE, and EE were the most potent at certain concentrations. According to

Table 1, they represent a good source of flavonoids, ferulic acid, and coumarins, as is well known [

10,

24]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the main metabolites of Andean tuber peels that promote the development of beneficial bacteria.

Andean tubers or their bioactive constituents, such as phenolic compounds [

25,

26], may act as prebiotics or nutraceuticals, that is, “a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit” [

27]. Thus, the combination of LAB with Andean tuber peel extracts may also serve as “symbiotic” that is a mixture of probiotics and prebiotics (dietary supplements), which selectively stimulating the growth and/or activating the metabolism of one or a limited number of health-promoting bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract, and thus improving host welfare [

28].

On the other hand, in many cases, the biofilm's stimulating effects did not result in a significant increase in growth, but rather in a probable adaptive behaviour to chemical stress, mediated by a cell-cell communication mechanism (

Quorum sensing), as published by Verni et al. [

22].

Capable of colonizing almost every environment, the microorganisms have evolved a wide range of biological responses to environmental stressors, and biofilms constitute a protective physical barrier that confers tolerance to antimicrobial agents (disinfectants and antibiotics) by reducing the diffusion of those toxic compounds. Moreover, they effectively reduce the grazing by protozoa. Biofilms are multicellular complex microbial communities held together by a self-produced extracellular matrix. They form highly diverse and complex structures that can attach to interfaces, grow, and aggregate in layers. Particularly, biofilm-growing probiotic bacteria can improve thermotolerance and freeze-drying resistance, and one of their important features is their capacity to replace pathogenic biofilms by annulling competitors [

29].

3.3. Impact on Gram-Negative Bacteria

Phytoextracts selected for their bioactivity did not display stimulant effects on Gram-negative bacteria (

Table S2). Some of these natural products significantly decreased biofilm formation (p < 0.05). As a result,

Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 biofilm biomass was reduced by 41.64% for the

U. tuberosus EAS (3EAS) at 25 µg/mL, and 42.64% by EE of

S. tuberosum subsp.

andigena var.

cuarentona (7EE); while EAS of the

miskila colorada variety diminished the biofilm of

E. coli O157:H12 by 70.58% at 100 µg/mL. Coherently, these extracts decreased

E. coli O157:H12 specific biofilms (SB) from 2.48 (control) to 0.73 (5EAS), and for the ATCC strain, from 0.87 (control) to 0.53 and 0.51 by 3EAS and 7EE, respectively (

Table S2, supplementary material).

For

Salmonella strains, significant effects were observed on the pathogenic strain

S. cerro (SF-16) with reductions of 79.86% and 42.24% by 3EAS and the

miskila colorada AE (5AE), respectively, at the highest concentration tested. Similarly, SB decreased from 3.44 to 0.78 and 1.99 by modifying cultures with 3EAS and 5AE. In addition, 3EAS, 7EE, and EE of

miskila colorada (5EE) at 100 µg/mL partially inhibited the biofilm biomass of the

S. corvalis strain (approximately 40%). For the

S. enterica ATCC 14028 biofilm, the reduction was only 22.75% by 5EE at 50 µg/mL, as shown in

Table S2.

Selective activity is a crucial matter since a balanced intestinal microbiome is necessary for the host's health. Maintaining a proper amount of beneficial bacteria, such as lactobacilli, in the gut is essential not only for the host's health status through the production of bioactive molecules and the detoxification of harmful compounds, but also for protection against incoming dangerous microorganisms. Beneficial bacteria can compete with enteric pathogens for nutrients, stimulate the development of both humoral and cellular immune systems, and strongly adhere to the intestinal mucosa, thereby preventing pathogen adhesion [

30]. The selective antibacterial/antipathogenic effects of diverse plant-derived compounds have also been reported in previous studies [

22,

31].

3.4. Chemical and Spectrochemical Data

Phenolic compounds absorb strongly in the ultraviolet region, and their spectra can be used for detection.

O. tuberosa and

U. tuberosus extracts exhibited typical UV absorptions of flavonoid compounds at 300–390 nm (band I) and band II at 250–280 nm (

Table 1). These bands are ascribable to the π→ π* transitions within the aromatic three-ring system of the ligand molecule. Specifically, band I is due to the absorption of the cinnamoyl system (ring B); while band II to that of the benzoyl moiety (ring A) [

32]. In all extracts, phenolic compounds, such as ferulic acid (287–312 nm) and coumarin (290–300 nm) absorption peaks were also recorded [

33].

These results were consistent with the preliminary chemical test data, as shown in

Table 1, and what was recently published by Vescovo and co-authors (2025), who claim that potato peels represent a rich source of bioactive compounds, including phenolics among other constituents, as a byproduct of significant agro-industrial value [

12].

Table 1.

Phytochemicals from Andean tuber peels' extracts, yields, and comparative UV spectroscopy data of the selected bioactive extracts.

Table 1.

Phytochemicals from Andean tuber peels' extracts, yields, and comparative UV spectroscopy data of the selected bioactive extracts.

Andean plant tubers

(Names) |

Peel extracts

(Codes) |

Extract yields (%) |

Phenolic compounds

(FeCl3 and AlCl3 reagents) |

UV spectroscopy |

Assignments |

| λ (nm) |

Abs |

Oxalis tuberosa var.

oca rosa

|

1AE |

1.19 |

Positive |

348.5 |

1.003 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 325.5 |

1.120 |

Ferulic acid and coumarins |

| 303.5 |

1.225 |

1EAS

|

0.50 |

Positive |

323.0 |

0.774 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 282.4 |

1.243 |

Flavonoids (benzoyl group)

Ferulic acid and coumarins |

Ullucus tuberosus

|

3AE

|

7.29 |

Positive |

348.5 |

0.631 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 267.5 |

1.147 |

Flavonoids (benzoyl group) |

3EAS

|

0.11 |

Positive |

351.2 |

0.704 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 277.2 |

1.191 |

Flavonoids (benzoyl group) Ferulic acid and coumarins |

Solanum tuberosum subsp. andigena

var. miskila colorada

|

5AE |

2.00 |

Positive

|

343.0 |

0.791 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 300.5 |

0.461 |

Ferulic acid and coumarins |

5EAS |

0.16 |

Positive |

341.5 |

0.617 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 321.5 |

0.964 |

Ferulic acid and coumarins |

| 300.5 |

0.447 |

5EE

|

2.47 |

Positive |

322.0 |

1.110 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 305.5 |

0.965 |

Ferulic acid and coumarins |

| 294.5 |

0.956 |

Flavonoids (benzoyl group) |

Solanum tuberosum subsp. andigena var.

cuarentona

|

7EE

|

3.15 |

Positive

|

322.0 |

1.843 |

Flavonoids (cinnamoyl group) |

| 305.5 |

1.619 |

Ferulic acid and coumarins |

3.5. Mutagenic Compounds Biodegradation

Phenol was chosen as a representative mutagenic disinfectant [

23] for its treatment; as well as

o-phenylphenol (OPP), which is usually applied in disinfections, veterinary hygiene, food and animals, being very toxic to aquatic life with lasting effects, and causing serious eye damage and skin and respiratory irritations [

34].

Phenol was completely degraded to even 100 μg/mL by L. paracasei CO1 and Lp. plantarum ATCC 10241, after seven days of static incubation at 37 °C (pH 5.0 ± 0.2). Using two chromatographic methods (TLC and GC-MS), no traces of phenol were detected in the obtained chromatographic profiles, indicating the ability of these LAB strains to remove the mutagenic substance.

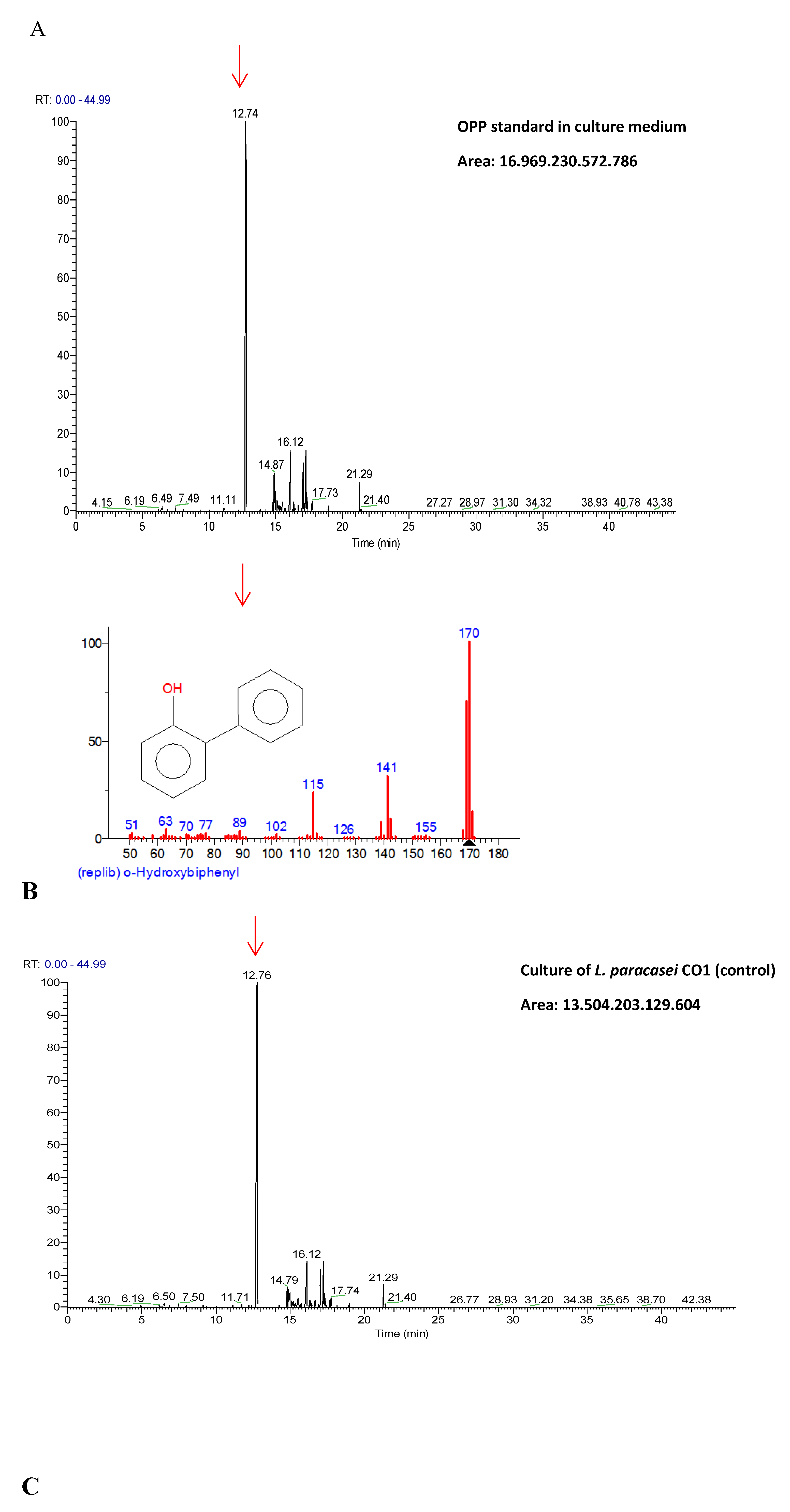

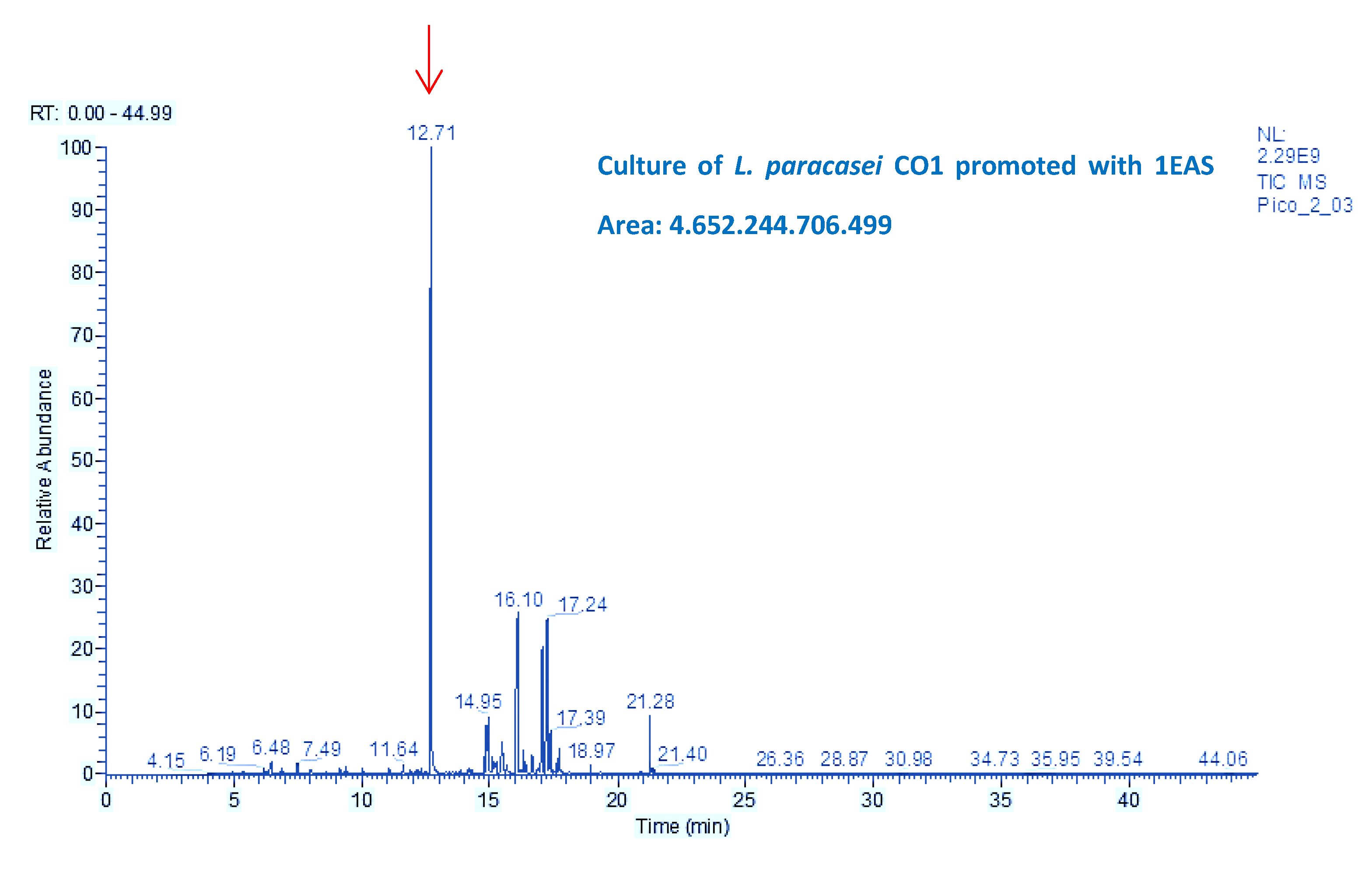

In contrast, 20% of OPP previously added to the culture medium in 100 μg/mL solution was degraded by the wild-type strain CO1; while this same culture previously stimulated with 1EAS at 25 µg/mL removed it up to 73%; this was inferred from the GC-MS profiles, as shown in

Figure 3A-C.

This differential behavior is likely due to structural features and lipophilicity, being OPP more stressful and stimulating to surface activity than phenol (

Table 2). Biosurfactants facilitate the solubilization and metabolism of lipophilic substances. This process is more difficult for OPP (

n-octanol-water partition coefficient = 3.06) than for phenol (

n-octanol-water partition coefficient = 1.47).

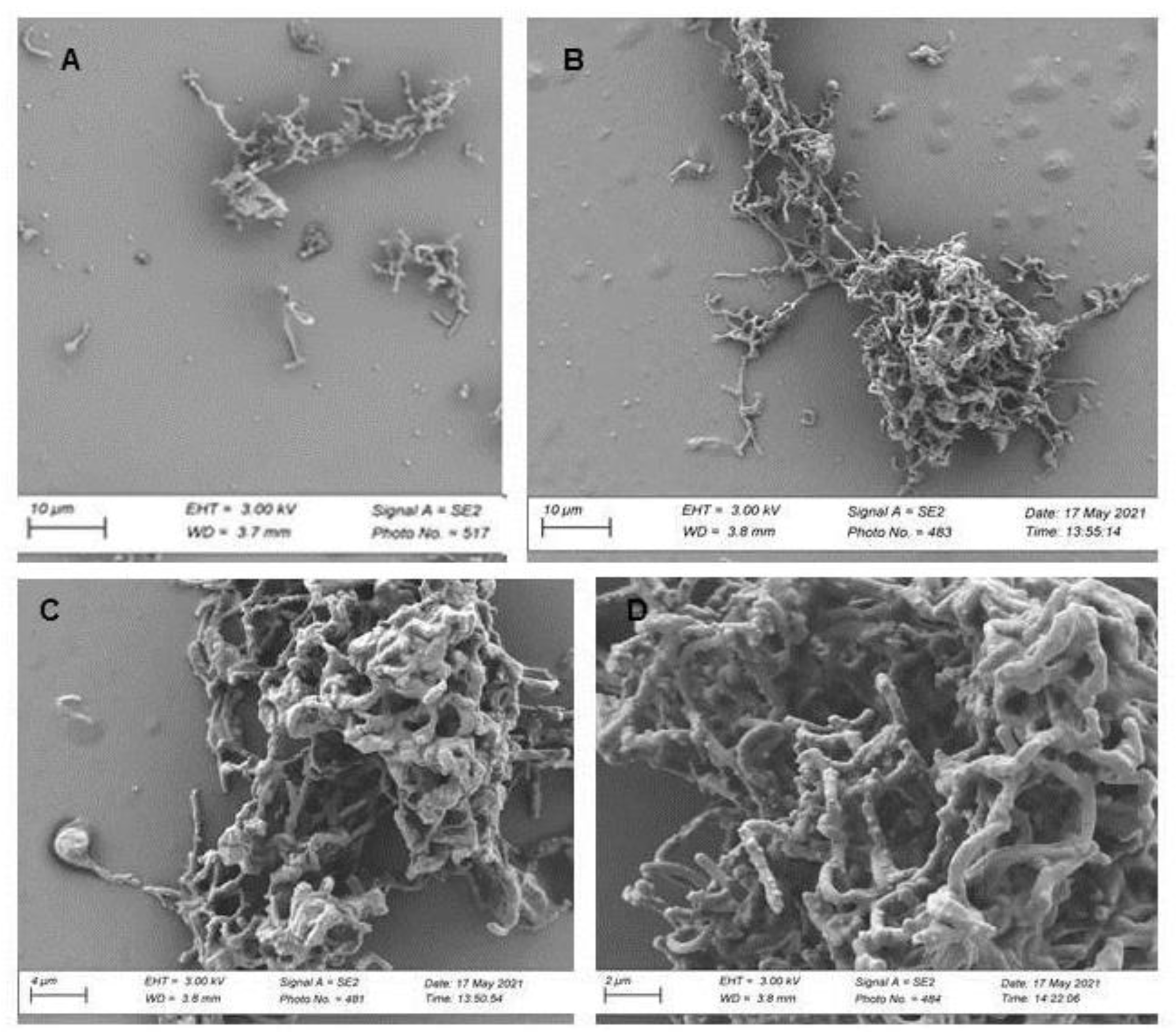

It is noteworthy that the SEM analysis showed a strong increase in biofilm biomass in presence of phenol (25 µg/mL), with a higher number of adhering cells, which are arranged in the form of solid aggregates with slimy material in their vicinity (

Figure 4B-D), unlike what was observed in the control cells (

Figure 4A). Microphotographs also revealed that treated cells present a rough surface with a considerable number of variable-sized protrusions (

Figure 4D), as an adaptive response to chemical stress. These results are in agreement with previous studies [

22,

35].

Figure 3.

A-C. GC-MS profiles. A: Solution of 100 µg/mL OPP standard. B: Culture from L. paracasei CO1 treated with 100 µg/mL of OPP. C: Culture from L. paracasei CO1 promoted with 1EAS and treated with 100 µg/mL.

Figure 3.

A-C. GC-MS profiles. A: Solution of 100 µg/mL OPP standard. B: Culture from L. paracasei CO1 treated with 100 µg/mL of OPP. C: Culture from L. paracasei CO1 promoted with 1EAS and treated with 100 µg/mL.

Figure 4.

A-D. Scanning electron microphotographs of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 cultures grown in the presence (treated) and absence (control) of phenol at 25 µg/mL. A: Control (2500x). B–D: Treated (1000x, 2500x and 5000x, respectively).

Figure 4.

A-D. Scanning electron microphotographs of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 cultures grown in the presence (treated) and absence (control) of phenol at 25 µg/mL. A: Control (2500x). B–D: Treated (1000x, 2500x and 5000x, respectively).

3.6. Air-liquid Surface Activity

Phenolic compounds added to the cultures enhanced the oil-spreading activity of the supernatant, particularly when OPP or PhOH at 100 μg/mL were individually added to the

L. paracasei CO1 cultures, which had been previously incubated with the

oca rosa EAS at 25 μg/mL. Halos were, approximately, four and twice times larger than that of the control supernatant (80 ± 5 mm), and higher than tween 80 (50 ± 3 mm). Probiotic

Lp. plantarum ATCC 10241 strains also increased their surfactant activity in the presence of PhOH (24%), as shown in

Table 2.

It is important to note that these substances and their solvent system, previously added to the culture media, did not exert any surface activity by themselves. Therefore, the substantial increase in supernatant surface activity would be due to an increase in surface-active substances resulting from induction of their biosynthesis in the LAB cultures, as reported in our previous studies [

22]. The biosurfactants' increase optimizes the biodegradation process, as explained in section

3.5.

Table 2.

LAB Surfactant activity.

Table 2.

LAB Surfactant activity.

| Supernatants |

Oil spreading halos (mm) |

Surfactant activity* |

|

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 |

80 ± 5 |

100% |

|

L. paracasei CO1 + OPP |

160 ± 0 |

200% |

|

L. paracasei CO1-EAS + OPP |

320 ± 0 |

400% |

|

L. paracasei CO1 + PhOH |

88 ± 1 |

110% |

|

L. paracasei CO1- EAS + PhOH |

169 ± 2 |

212% |

|

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATCC 10241 |

105 ± 2 |

100% |

|

Lp. plantarum ATCC 10241 + PhOH |

130 ± 1 |

124% |

| Tween 80 |

50 ± 3 |

62.5% |

3.7. Phenol Oxidase Activity

Phenol and OPP biodegradation was carried out by phenol oxidases determined according to Lee et al. (2007) in the

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1 cultures by adding specific enzymatic inhibitors that increased the susceptibility of this bacterium to phenol, and by the oxidase test. The occurrence of (poly)phenol oxidases in LAB was previously reported by Matthews et al. (2004) [

36].

These results showed congruence with our previous studies of the

Flourensia fiebrigii phytochemicals that demonstrated stimulant effects on

L. paracasei subsp.

paracasei CE75 strain with detoxifying potential, as well as enzymes and biosurfactants involved in the process [

17,

22].

4. Conclusions

The study provides valuable and comprehensive information on the Andean tubers' peels as natural sources of phytochemicals mainly phenolic compounds, and their selective stimulating effects on probiotic and environmental bacteria without promoting the development of pathogenic bacteria.

A novel indigenous strain was also identified as Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CO1, with a promising detoxifying activity of a mutagenic substance, phenol, in high concentrations of 100 µg/mL just like Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATCC 10241 did. In addition, small amounts of EAS from O. tuberosa var. oca rosa added to L. paracasei CO1 culture medium increased the bacterial surfactant activity and its OPP detoxification capacity, mediated by phenol oxidases.

Given the nutraceutical and biotechnological potential of Andean tuber peels, it is essential to promote global strategies for their sustainable applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

C.H.O: Performed the experiments, analysed the data. M.I.M.: Performed the experiments, analysed the data, wrote the paper. F.E.A.M.: Performed the experiments, analyzed the data. M.E.A.: Performed the experiments, analysed the data, wrote the paper. E.C.: Conceived and designed the experiments, analysed the data, wrote the paper and supervised.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the SCAIT-UNT (PIUNT 26D-715, 26D-708, PICT2021-A00439) and the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, CONICET.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the UNT, and CONICET that made this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Erginkaya, Z.; Konuray-Altun, G. Potential biotherapeutic properties of lactic acid bacteria in foods. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101544. [CrossRef]

- Abedin, M.M.; Chourasia, R.; Phukon, L.C.; Sarkar, P.; Ray, R.C.; Singh, S.P.; Rai, A.K. Lactic acid bacteria in the functional food industry: Biotechnological properties and potential applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 5, 1–9.

- Nuñez, I.M.; Verni, M.C.; Argañaraz Martinez, F.E.; Babot, J.D.; Terán, V.; Danilovich, M.E.; Cartagena, E.; Alberto, M.R.; Arena, M.E. Novel lactic acid bacteria strains from regional peppers with health-promoting potential. Fermentation 2024, 10, 209. [CrossRef]

- Dable-Tupas, G.; Otero, M.C.B.; Bernolo, L., Eds.; Functional foods and nutraceuticals: bioactive components, formulations, and innovations. Springer Nature, Berlin, 2020.

- Reque, P.M.; Brandelli, A.. Encapsulation of probiotics and nutraceuticals: Applications in functional food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chantre-López, A.R.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.A.; Salazar-Sánchez, M. del R.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Nery-Flores, S.D., et al. Andean tubers: traditional medicine and other applications. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 342–352. [CrossRef]

- Leidi, E.O.; Altamirano, A.M.;, Mercado, G.; Rodriguez, J.P.; Ramos, A.; Alandia, G.; Sørensen, M.; Jacobsen, S.E.,. Andean roots and tubers crops as sources of functional foods. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 51, 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Camire, M.E.; Kubow, S.; Donnelly, D.J. Potatoes and human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 823–840. [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Cruz, G.P.; Silva-Correa, C.R.; Calderón-Peña, A.A.; Villarreal-La Torre, V.E.; Aspajo-Villalaz, C.L.; CruzadoRazco, J.L.; Rosario-Chávarri, J.; Rodríguez-Soto, J.; Pretel-Sevillano, O.; Sagástegui-Guarniz, W.; González Siccha, A. Wound healing activity of an ointment from Solanum tuberosum L. “Tumbay yellow potato” on Mus musculus Balb/c. Pharmacogn J. 2020, 12, 1268–1275. [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.; Noratto, G.; Chirinos, R.; Arbizu, C.; Roca, W.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L., Antioxidant capacity and secondary metabolites in four species of Andean tuber crops: native potato (Solanum sp.), mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pavon), oca (Oxalis tuberosa Molina) and ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus Caldas). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1481–1488. [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Ghislain, M.; Bertin, P.; Oufir, M.; Herrera, M.R.; Hoffmann, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Larondelle, Y.; Evers, D. Andean potato cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.) as a source of antioxidant and mineral micronutrients. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 366–378. [CrossRef]

- Vescovo, D.; Manetti, C.; Ruggieri, R.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Aiello, F.; Martuscelli, M.; Restuccia, D. The Valorization of potato peels as a functional ingredient in the food industry: A comprehensive review. Foods 2025, 14, 1333. [CrossRef]

- Mis-Solval, K.E.; Jiang, N.; Yuan, M.; Joo, K.H.; Cavender, G.A. The Effect of the ultra-high-pressure homogenization of protein encapsulants on the survivability of probiotic cultures after spray drying. Foods 2019, 8, 689. [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds; Wiley: New York, 1991; pp. 115–175.

- O'Toole, G.A.; Kolter, R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 28, 449–461. [CrossRef]

- Amaya, S; Pereira, J.A.; Borkosky, S.A.; Valdez, J.C.; Bardón, A.; Arena, M.E. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by sesquiterpene lactones. Phytomedicine 2012, 19,1173–1177. [CrossRef]

- Cartagena, E.; Orphèe, C.H.; Verni, M.C.; Arena, M.E.; González, S.N.; Argañaraz, M.I.; Bardón, A. Patent: Medio de Cultivo Promotor y Bacterias No Patógenas Detoxificantes de Compuestos Mutagénicos/Carcinogénicos. Instituto Nacional de la Propiedad Industrial-INPI Nº 20190102418, Argentina, 2021.

- Walter, V.; Syldatk, C.; Hausmann, R. Screening Concepts for the Isolation of Biosurfactant Producing Microorganisms. In Biosurfactants. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Sen, R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2010; pp. 1–13.

- Sambanthamoorthy, K.; Feng, X.; Patel, R.; Patel, S.; Paranavitana, C. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm potential of biosurfactants isolated from lactobacilli against multi-drug-resistant pathogens. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Application of UV-vis spectroscopy in the detection and analysis of substances. Transactions on Materials, Biotechnology and Life Sciences 2024, 3, 131-136. [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.C.; Orphèe, C.H.; González, S.N.; Bardón, A.; Arena, M.E.; Cartagena, E. Flourensia fiebrigii SF Blake in combination with Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei CE75. A novel antipathogenic and detoxifying strategy. LWT 2022, 156, 113023. [CrossRef]

- ECHA European Chemicals Agency Documents, 2021. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/de108693-1d4f-abfe-818e-9cea812ab4c2.

- Lachman, J.; Hamouz, K. Red and purple coloured potatoes as a significant antioxidant source in human nutrition – a review. Plant Soil Environ. 2005, 51, 477–482. [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.; Betalleluz-Pallardel, I.; Chirinos, R.; Aguilar-Galvez, A.; Noratto, G.; Pedreschi, R. Prebiotic effects of yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius Poepp. & Endl.), a source of fructooligosaccharides and phenolic compounds with antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1592–1599. [CrossRef]

- Verediano, T.A.; Viana, M.L.; Vaz-Tostes, M.D.G.; Costa, N. The potential prebiotic effects of yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius) in colorectal cancer. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 17, 167–175. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; Verbeke, K.; Reid, G.. Expert consensus document: The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Palai, S.; Derecho, C.M.P.; Kesh, S.S.; Egbuna, C.; Onyeike, P.C. Prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and its importance in the management of diseases. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals: Bioactive Components, Formulations and Innovations 2020. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 173–196.

- Berlanga, M.; Guerrero, R. Living together in biofilms: the microbial cell factory and its biotechnological implications. Microb. Cell Fact. 2016, 15, 165–176. [CrossRef]

- Frassinetti, S.M.G.; Moccia, E.; Longo, V.; Di Gioia, D. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of Cannabis sativa L. seeds extract against Staphylococcus aureus and growth effects on probiotic Lactobacillus spp. LWT 2020, 124, 109149. [CrossRef]

- Cartagena, E.; Arena, M.E.; Verni, M.C.; Bardón, A.. Natural terpenoids as a valuable resource of selective health-beneficial biofilm promoters, in Rowland, S. (Ed.), Biofilms: Advances in Research and Applications. 2021. Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp. 159–186.

- Santonoceta, G.D.G.; Sgarlata, C.. pH-Responsive Cobalt(II)-coordinated assembly containing quercetin for antimicrobial applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 5581. [CrossRef]

- Holser, R. Principal component analysis of phenolic acid spectra. ISRN spectroscopy 2012. [CrossRef]

- ECHA, 2023. https://echa.europa.eu/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.001.812.

- Parlindungan, E.; Dekiwadia, C.; Tran, K.T.; Jones, O.A.; May, B.K. Morphological and ultrastructural changes in Lactobacillus plantarum B21 as an indicator of nutrient stress. LWT 2018, 92, 556–563. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A.; Grimaldi, A.; Walker, M.; Bartowsky, E.; Grbin, P.; Jiranek, V. Lactic acid bacteria as a potential source of enzymes for use in vinification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5715–5731. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).