Introduction

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) has emerged as a pivotal intervention for the treatment of various thoracic aortic pathologies, including thoracic aortic aneurysms, type B aortic dissections, and traumatic aortic injuries. This minimally invasive procedure has been offering significant advantages over traditional open surgical approaches, including reduced recovery times, and lower perioperative morbidity and mortality for over the past two decades. With the evolution of endovascular techniques and consistently high procedural success rates, TEVAR has become the preferred first-line treatment for thoracic aortic pathologies in anatomically eligible patients [

1,

2,

3].

However, despite its numerous benefits, TEVAR is not without complications. Serious issues such as spinal cord ischemia (SCI) and the need for early or late reintervention remain significant concerns. Additionally, vascular injuries, including access site complications, guidewire-related injuries, retrograde dissection, and surrounding tissue complications such as aortoesophageal and aortobronchial fistulae, as well as malperfusion and renal failure, require careful consideration. Adverse events like endoleaks and endograft collapse can also lead to stroke, arm ischemia, or SCI, further emphasizing the potential impact of these complications on patient survival and quality of life [

3,

4].

SCI, a potentially devastating complication of TEVAR, arises due to compromised blood flow to the spinal cord. The incidence rates of SCI range from 2% to 10%, and are influenced by factors such as the extent of aortic coverage, the patient’s pre-existing vascular anatomy, and the presence of collateral circulation. Timely recognition and intervention can significantly alter patient outcomes. Meanwhile, reintervention rates following TEVAR also warrant attention, as they reflect the durability and effectiveness of the repair. These rates can be mainly influenced by the type of aortic pathology and the complexity of the procedure. Early reintervention—whether due to endoleak, graft migration, or device-related complications—continues to pose significant challenges despite procedural success [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

While multicenter registries provide valuable insight into long-term outcomes, single-center studies offer a more controlled environment to evaluate specific risk factors, institutional protocols, and patient-specific outcomes. In this study, we aimed to analyze early outcomes of TEVAR, with a particular focus on the incidence of spinal cord ischemia and reintervention rates, in a consecutive cohort of patients treated at a single high-volume tertiary care center.

Methods

The methodology employed in this study on the early outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair focuses on a comprehensive retrospective analysis of patient data collected from a single surgical center. This approach enables a rigorous analysis of the incidence of spinal cord ischemia (SCI) and reintervention rates associated with TEVAR procedures. The cohort included patients who underwent TEVAR for various thoracic aortic pathologies, such as aneurysm and dissections, between February 2012 and August 2023. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients aged 18 years and older, while those with previous spinal cord injuries or significant comorbidities that could influence outcomes were excluded to ensure a more homogeneous study population.

Data collection involved a thorough review of electronic medical records, focusing on demographic information, preoperative characteristics, procedural details, and postoperative outcomes. Key variables included aortic pathology type, repair extent, and the use of adjunctive techniques like cerebrospinal fluid drainage, which is linked to reduced SCI rates. Additionally, the study employed standardized definitions for SCI and reinterventions, allowing for consistent reporting and analysis. The primary endpoints were the incidence of SCI observed within 30 days after surgery and the reintervention rates recorded during the first year following TEVAR. Statistical analyses were performed using appropriate software to assess the relationships between various risk factors and outcomes, employing both univariate and multivariate models to control for confounding variables.

This methodology not only provides a comprehensive understanding of the early complications linked to TEVAR but also contributes to the expanding literature focused on optimizing patient selection and procedural techniques. The findings will serve as a foundation for future prospective studies and clinical trials aimed at refining TEVAR strategies and minimizing complications such as SCI and the need for reintervention.

Follow-up and Definitions: The first CTA scan after surgery was performed during the 1-month follow-up. Patients were then scheduled for follow-ups at 6 months and subsequently on an annual basis. The patients' medical histories in the hospital system were reviewed, and their medications were documented. The hospital admission and surgery dates of the cases were examined to determine whether they were elective or emergency based on CTA results. Coronary artery disease was defined for patients who were under cardiology follow-up due to previous angina or myocardial infarction and receiving medical treatment; COPD was defined as progressive lung disease for patients who were receiving inhaler treatment or home oxygen therapy. Patients diagnosed with diabetes who were under diet control, and those receiving insulin or oral antidiabetic treatment were included in the diabetes category; patients with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 45 mL/min or lower were included in the renal insufficiency category.

To mitigate procedure-related complications, specific preventive measures were implemented in selected cases. For instance, in patients scheduled for elective surgery requiring aortic coverage exceeding 20 cm, cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheters were placed to prevent spinal cord ischemia, provided there were no contraindications and following consultation with neurosurgery. Additionally, patients with proximal lesions necessitating subclavian artery coverage underwent carotid-subclavian bypass either prior to or during the follow-up period of TEVAR, and these cases were meticulously documented.

Table 1.

Demographics and preoperative characteristics of TEVAR patients (n=146).

Table 1.

Demographics and preoperative characteristics of TEVAR patients (n=146).

| Sex, male |

116(79,45%) |

|

| Age,years |

63.23 ±12.50 |

min:29 /max:85 |

| Hypertension |

124(84.9%) |

|

| COPD |

41(28,1%) |

|

| Renal insufficiency |

33(22.6%) |

|

| Diabetes |

23(15.8%) |

|

| Coronary artery disease |

71(48,6%) |

|

| History of smoking |

61(41.8%) |

|

| History of Cerebrovascular disease |

6 (4.1%) |

|

| Preoperative aspirin |

85(58.2%) |

|

| Preoperative statin |

46(31.5%) |

|

| Elective |

121(82.8%) |

|

| Urgent |

25(17.1%) |

|

The total operation time was recorded in minutes, from the moment the patient entered the operating room and anesthesia was initiated, until the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, based on data obtained from anesthesia records. The region starting from the left carotid artery up to the mid descending aorta, including the left subclavian artery, is referred to as the proximal zone, the distal zone included the mid descending aorta. Postoperative stroke, SCI, and arm ischemia were recorded as significant complications, and 30-day mortality and reinterventions within 1 year were noted during the follow-up period.

The primary outcomes were SCI and reintervention. We hypothesized that reinterventions might be less frequent in elective cases and short segment lesions, while the risk of SCI might be increased in patients with long segments closed in the distal region.

Statistical Analysis. Categorical data are presented as n (%), and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation. The Kaplan-Meier curve with log-rank test was used for early mortality during the follow-up period. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the variables that influenced the development of any SCI and reintervention. The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.2.0).

Results

The data for 146 patients who underwent TEVAR between February 2012 and August 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Among the 146 patients analyzed, 116 (79.45%) were male, with an average age of 63.23 ± 12.50. The patients' demographic characteristics, comorbidities, preoperative medications, and the urgency of the procedure are presented in

Table 1.

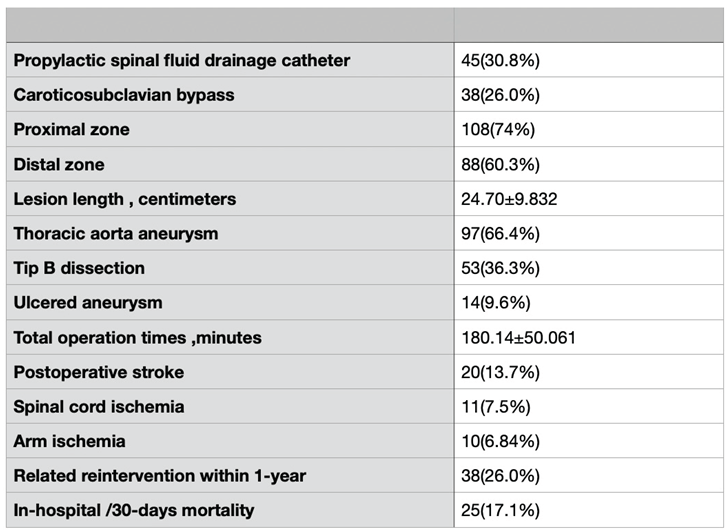

Hypertension, which is one of the most significant causes of aneurysm development, was present in 124 (84.9%) patients. Based on CTA results, 3D analysis showed that in 108 patients (74%), the intervention area was proximally located. Carotid-subclavian bypass was performed in 38 patients (28% of the total) to prevent arm ischemia, as the left subclavian artery was closed in some cases (

Table 2).

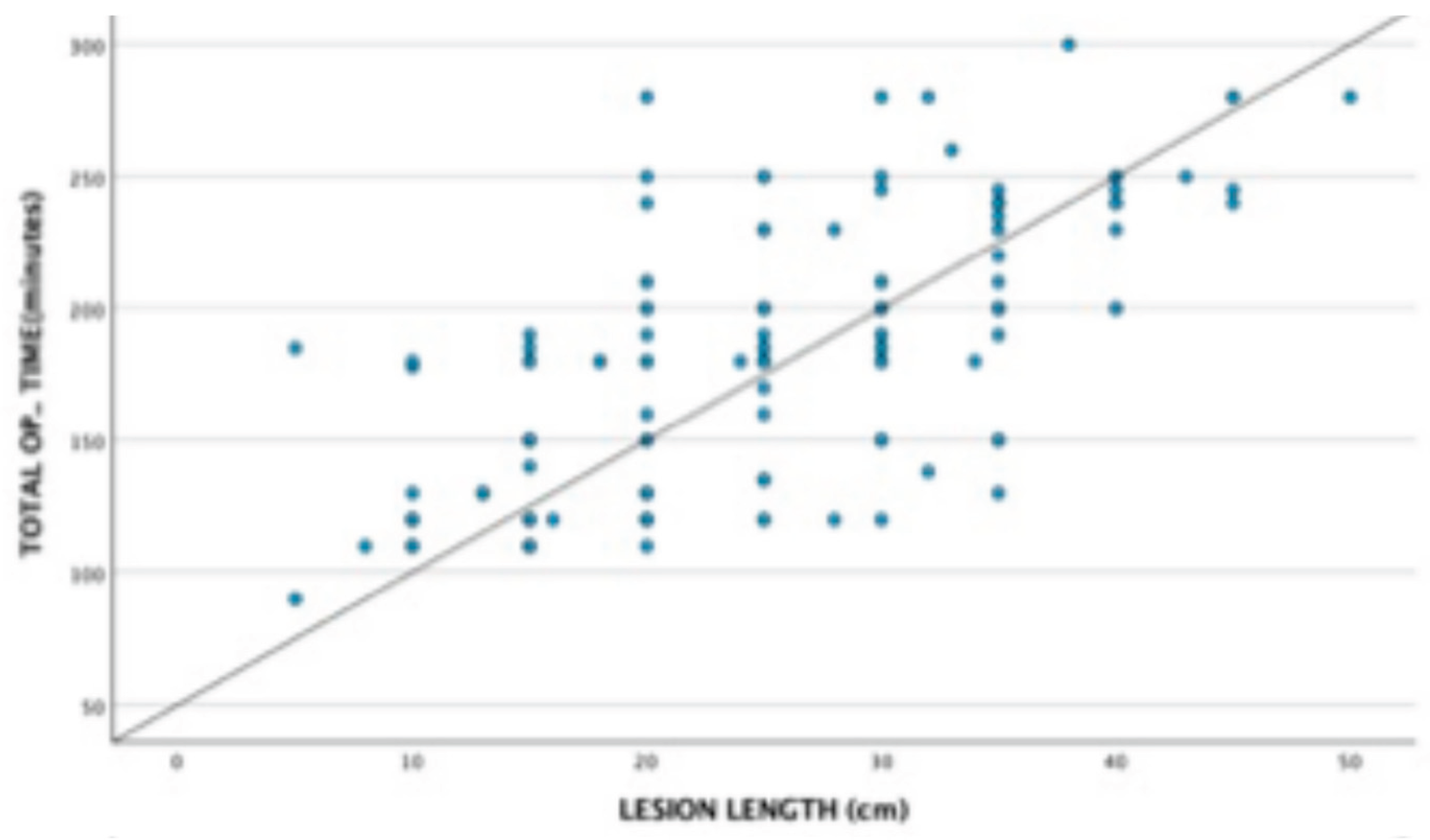

The average lesion length was 24.7 ± 9.832 centimeters, and the mean total operation time was 180.4 ± 50.061 minutes. A linear correlation was observed between lesion length and operative time, possibly due to the need for additional procedures, repeat angiographies, and balloon angioplasty, as shown in

Figure 2.

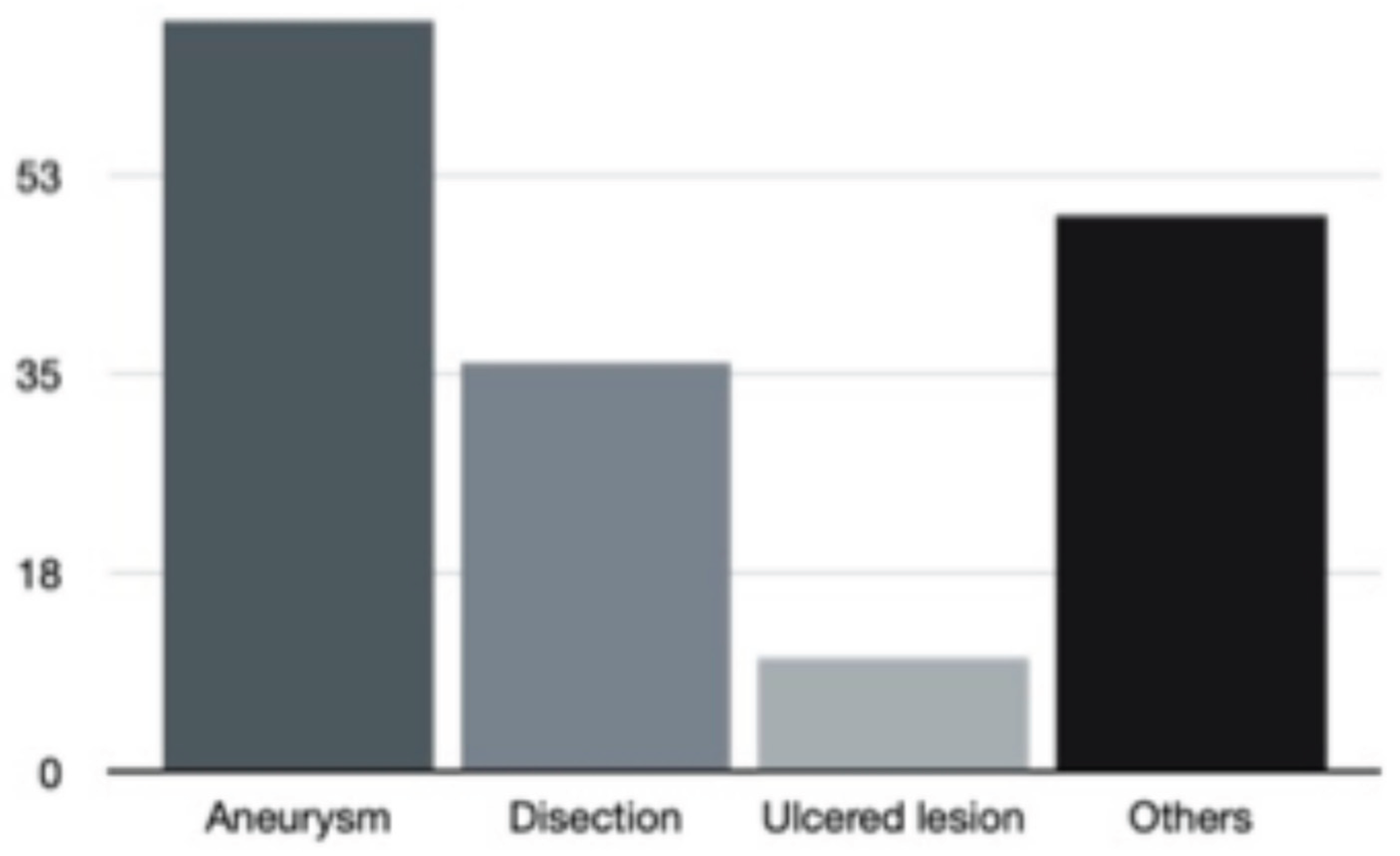

When examining the pathologies requiring TEVAR, we observed that thoracic aortic aneurysms were the most common, with 97 patients (66.4%). Other pathologies, including transection, rupture, pseudoaneurysm, extended type A dissection, and coarctation, accounted for 48.6% (71 patients) (

Table 2/

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of thoracic aortic pathologies among the study population.

Figure 1.

Distribution of thoracic aortic pathologies among the study population.

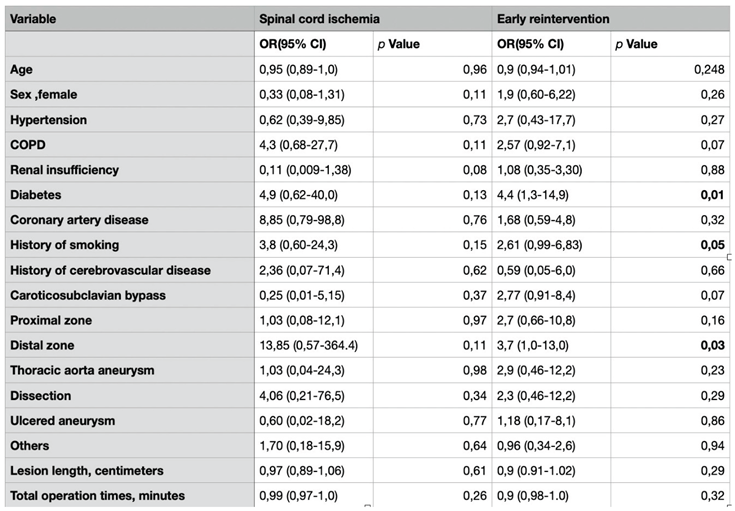

Among the complications, postoperative stroke was observed in 20 patients (13.7%), and arm ischemia, likely due to occlusion of the subclavian artery, was observed in 10 patients (6.84%). Spinal cord ischemia occurred in 11 patients (7.5%), while TEVAR-related reintervention was required in 38 patients (26%). According to

Table 3, which evaluates the relationship between our primary endpoints, SCI and reinterventions, and other variables in terms of Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals, no significant relationship was found between SCI and other variables (p-value >0.05); however, a statistically significant relationship was observed between reinterventions and smoking, diabetes, and lesions located in the distal zone (p-value <0.05). When we look at the 30-day mortality associated with primary or secondary causes related to TEVAR, we see that it has a percentage of 17.1% (

Table 2).

Figure 2.

Correlation between lesion length and operative time in patients undergoing TEVAR.

Figure 2.

Correlation between lesion length and operative time in patients undergoing TEVAR.

Discussion

The management of thoracic vascular diseases has undergone significant advancements over the past few decades. While traditional approaches relied on extensive and invasive surgical procedures, technological progress and an improved understanding of vascular pathologies have shifted the paradigm. Since it was first reported by Dake et al. in 1994, the indications and applications of TEVAR (Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair) have steadily increased with advancing technology and published experiences. Endovascular repair is widely used in complicated cases such as rupture and dissection, based on several studies comparing it with open surgical repair, highlighting its lower perioperative mortality and morbidity rates [

9,

10]. In this study, we aimed to highlight our early outcomes, including early reintervention, hospital mortality, and spinal cord ischemia, based on our single-center clinical experience with TEVAR.

Isaac et al. reported a 30-day mortality rate of 4.2% in a study of 2141 patients who underwent endovascular repair for thoracic aortic aneurysm in 2022. In addition to this study involving stable aneurysms, Philip et al. reported a perioperative mortality rate of 6.1% for intact aneurysms, compared to a rate of 28% for ruptured cases [

11,

12]. Considering that our study included not only patients with intact aneurysms but also complicated cases such as ruptured aneurysms and dissection patients, it would not be incorrect to state that our 30-day mortality rate of 17.1% (25 patients) is consistent with the literature data.

According to the data from non-comparative, single-center, retrospective studies in the literature, there is no definitive information on preventing SCI. However, looking at the incidence rates, we see that SCI occurs in less than 10% of cases after TEVAR and has been reported to occur in 2-15% of cases after open repair [

5,

13,

14]. Reflecting the results of a prospective, single-center 5-year study, the W.L. Gore TAG (W.L. Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ) pivotal trial reported a 2.9% incidence of SCI among 139 patients who had a repair of a descending thoracic aneurysm [

14,

15]. In our study, which included 146 patients, encompassing not only aneurysm cases but also other TEVAR procedures requiring endovascular intervention, we observed an SCI incidence of 7.5%.

To prevent spinal cord ischemia, certain protective measures can be taken by considering the risk factors. Among these, cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheters (CFDC) are the most important and are recommended to prevent paraplegia, which is a significant complication of thoracic aortic repair [

7,

16]. In our clinical practice, if the area of the aorta to be covered by the stent is large (>200 mm) and there are no contraindications related to the patient, we prefer to consult with the neurosurgery department regarding the placement of CFDC. Although lesion length is not an established criterion, considering the possibility of occluding the Adamkiewicz artery in the T11-L3 region, ESVS has recommended that spinal cord protection (including CSF drainage) should be considered in patients with a prior AAA repair or in patients who require extensive aortic repairs.

Keeping in mind that cerebrospinal fluid drainage can also have procedure-related complications (0-7%), such as headache, subdural hematoma, or suspected meningitis, we believe that inserting CFDC in patients at high risk for spinal cord ischemia could further improve the outcomes of TEVAR. We know that the risk factors for SCI after TEVAR are multifactorial. However, previous publications have included factors such as the length of aortic coverage, prior abdominal aortic surgery, hypotension, iliac artery injury, and coverage of the left subclavian artery [

6]. In our study, we did not find a significant relationship (p>0.05) between SCI and some variables, as seen in

Table 3, when we conducted a logistic regression analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis predictors of spinal cord ischemia and early reintervention.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis predictors of spinal cord ischemia and early reintervention.

Another outcome, early reinterventions in the TEVAR group, such as the need for follow-up CTA and additional grafts, can be considered a disadvantage of endovascular treatments due to the associated costs. Some authorities argue that TEVAR does not alter the natural history of the disease, suggesting that it is not superior to open surgery. It is also important to note that longer follow-up periods are needed to clear these concerns [

17]. When we look at the results of reinterventions, which are considered to be negative outcomes of endovascular interventions, in our clinic, we see that it is 26%. According to the literature, the reintervention rates for cases where TEVAR is applied for thoracic aneurysm range between 15% and 17%. However, Parsa et al. [

10,

18] reported reintervention rates of 23% in dissection cases, while Böckler et al. [

19] reported rates of 32% [

10]. Considering that complicated cases might increase reintervention rates, the reintervention rates in our series appear to be consistent with the literature data.

Our results show that diabetes mellitus (p-value 0.01), smoking history (p-value 0.05), and distal zone location of the lesion (p-value 0.03) are potential risk factors for reintervention (

Table 3). Surprisingly, a published meta-analysis also suggested that diabetes mellitus may be negatively associated with the presence of thoracic aortic dissection and aneurysm. Besides, there is data suggesting that it may even be protective against aortic dissection [

20,

21,

22]. It is necessary to mention that multi-center studies with long follow-up periods are needed to clarify this complex situation related to diabetes.

Limitations

One of the major limitations of our study is its retrospective nature and reliance on follow-up results available within the hospital system. Another point is that it presents single-center results from a small patient population of 146 patients. The patient population consisted of a heterogeneous group, including dissection, aneurysm, rupture, coarctation, etc. It should be noted that subgroup analyses are necessary to present the results more objectively. Our results are based on an average of one-year follow-ups, and the inability to present long-term survival analyses is one of the significant limitations. Despite these limitations, our findings offer valuable insights into early TEVAR outcomes in real-world clinical settings.

Conclusion

Endovascular techniques, particularly thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), have emerged as a preferred approach for aortic repair due to their lower complication rates and reduced perioperative mortality compared to conventional open surgical methods. Despite its advantages, the potential need for conversion to open surgery remains a critical concern, often stemming from the procedural complexities involved. Early intervention with TEVAR offers significant benefits for certain patient groups, and improved clinical outcomes are expected as operator expertise continues to advance. Future multicenter trials are warranted to validate these findings. Additionally, randomized clinical trials involving larger patient cohorts are needed to derive more conclusive evidence and advance clinical practice. Ultimately, healthcare institutions must critically evaluate their procedural expertise and align their practices with achievable standards to maximize the benefits of TEVAR and minimize associated risks.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: MCS, FA. Analysis and interpretation: FA, MCS. Data collection: FA, AFK, SAB, OB. Writing the article: MCS, FA. Critical revision of the article: EÖ, AİH, CB, LY, SE. Final approval of the article: SE, EÖ. Statistical analysis: FA, MCS. Obtained funding: none. Overall responsibility: MCS, SE, EÖ.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective single-center study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The human research ethics committee details include the date of approval (14 March 2025) and protocol number (2024/720).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen SW, Lee KB, et al. Complications and management of the thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Aorta (Stamford). 2020;8(3):49–58. [CrossRef]

- Badran A, Elghazouli Y, Shirke MM, et al. Elective thoracic aortic aneurysm surgery: A tertiary center experience. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39102. [CrossRef]

- Sattah AP, Secrist MH, Sarin S. Complications and perioperative management of patients undergoing thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33(7):394–406. [CrossRef]

- Grabenwöger M, Alfonso F, Bachet J. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for the treatment of aortic diseases: A position statement from the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2012;33(13):1558–1563. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura J, Oshima H, et al. The efficacy and risk of cerebrospinal fluid drainage for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: A retrospective observational comparison between drainage and non-drainage. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24:609–614. [CrossRef]

- Feezor RJ, Martin T, et al. Extent of aortic coverage and incidence of spinal cord ischemia after thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2008.

- Riambau V, Capoccia L, et al. Spinal cord protection and related complications in endovascular management of B dissection: LSA revascularization and CSF drainage. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3(3):336–338. [CrossRef]

- Geisbüsch P, Hoffmann S, et al. Reinterventions during midterm follow-up after endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(6):1528–1535.

- Cheng L. Reintervention after thoracic endovascular aortic repair of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J Clin Med. 2023;12(4):1418.

- Faure EM, Canaud L, Agostini C, et al. Reintervention after thoracic endovascular aortic repair of complicated aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:327–333. [CrossRef]

- Goodney PP, et al. Survival after open versus endovascular thoracic aortic aneurysm repair in an observational study of the Medicare population. Circulation. 2011;124(24):2761–2769. [CrossRef]

- Naazie IN, et al. Risk calculator predicts 30-day mortality after thoracic endovascular aortic repair for intact descending thoracic aortic aneurysms in the Vascular Quality Initiative. Clin Res Thorac Aneurysm. 2022;75(3):833–841.e1.

- Scali ST, et al. National incidence, mortality outcomes, and predictors of spinal cord ischemia after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(1):152–160.

- Bavaria JE, Appoo JJ, Makaroun MS, et al. Endovascular stent grafting versus open surgical repair of descending thoracic aortic aneurysms in low-risk patients: A multicenter comparative trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:369–377. [CrossRef]

- Farber MA, et al. Five-year outcomes with conformable GORE TAG endoprosthesis used in traumatic aortic transections. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(5):1536–1542. [CrossRef]

- Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage reduces paraplegia after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(4):631–639.

- Son SA, Jung H, et al. Long-term outcomes of intervention between open repair and endovascular aortic repair for descending aortic pathologies: A propensity-matched analysis. BMC Surg. 2020;20:266. [CrossRef]

- Parsa CJ, Schroder JN, Daneshmand MA, et al. Midterm results for endovascular repair of complicated acute and chronic type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:97–102.

- Böckler D, Schumacher H, Ganten M. Complications after endovascular repair of acute symptomatic and chronic expanding Stanford type B aortic dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:361–368. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhao Z, et al. Reintervention after endovascular repair for aortic dissection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(5):1279–1288.e3.

- Takagi H, Umemoto T, ALICE (All-Literature Investigation of Cardiovascular Evidence) Group. Negative association of diabetes with thoracic aortic dissection and aneurysm. Angiology. 2016;67(3):229–236. [CrossRef]

- Theivacumar NS, Stephenson MA, Mistry H, et al. Diabetics are less likely to develop thoracic aortic dissection: A 10-year single-center analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:427–432. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).