1. Introduction

Aortic arch pathologies continue to challenge surgeons due to the complexity of surgical management. Although conventional surgical repair, which involves cardiopulmonary bypass and deep circulatory arrest, is considered the gold standard, it is associated with high mortality and morbidity. In patients with significant comorbidities, particularly in redo cases with a history of ascending aorta surgery, hybrid techniques have become preferable [

1,

2] To reconstruct the supra-aortic arteries, branched TEVAR (Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair), chimney techniques, and fenestration techniques have been developed. These techniques also have disadvantages, such as technical difficulty, high cost, and the need for advanced expertise [

1]. Therefore, there is a continuous search for new and improved approaches.

While the chimney technique is commonly used for visceral branches, fenestration techniques are widely applied in TEVAR cases where the landing zone is insufficient and the left subclavian artery needs to be covered. Revascularization of the left subclavian artery has been shown to reduce cerebrovascular accidents, spinal cord ischemia, and left upper extremity ischemia [

3]. The anatomical challenges and neurological risks associated with surgical revascularization for Zone 2 TEVAR and aortic arch pathologies have encouraged the exploration of alternative endovascular solutions. In situ fenestration (ISF) of thoracic endografts is the most common endovascular alternative to open repair techniques such as carotico-subclavian bypass. The development of self-centering, adjustable needle-based puncture devices has improved the safety and success rates of ISF, addressing previous technical and device-related issues reported with in situ laser fenestration [

1,

3,

4].

The aim of this study is to present the outcomes of triple in situ fenestration for aortic arch revascularization using a specially designed puncture needle in selected patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a single-center retrospective analysis of fifteen patients with aortic arch pathologies who underwent in situ triple fenestration TEVAR between June 2023 and March 2024 at the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Ankara University.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Ankara University (approval date: 21.03.2025, protocol number: 2025000227-2, registration number: 2025/227) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

All patients underwent follow-up computed tomography angiography (CTA) and clinical evaluations at 1 week, 30 days, 3 months, and 6 months after discharge. Clinical data were obtained from the hospital’s electronic medical records.

Exclusion criteria : [

1,

3]

Supra-aortic anatomic variants or carotid/vertebral artery stenosis

History of cerebrovascular events within the past 3 months

Allergy to iodinated contrast agents

Lack of available peripheral arterial access

Life expectancy less than 1 year, severe organ failure, or malignant tumors

2.2. Preoperative Planning and Endovascular Procedure

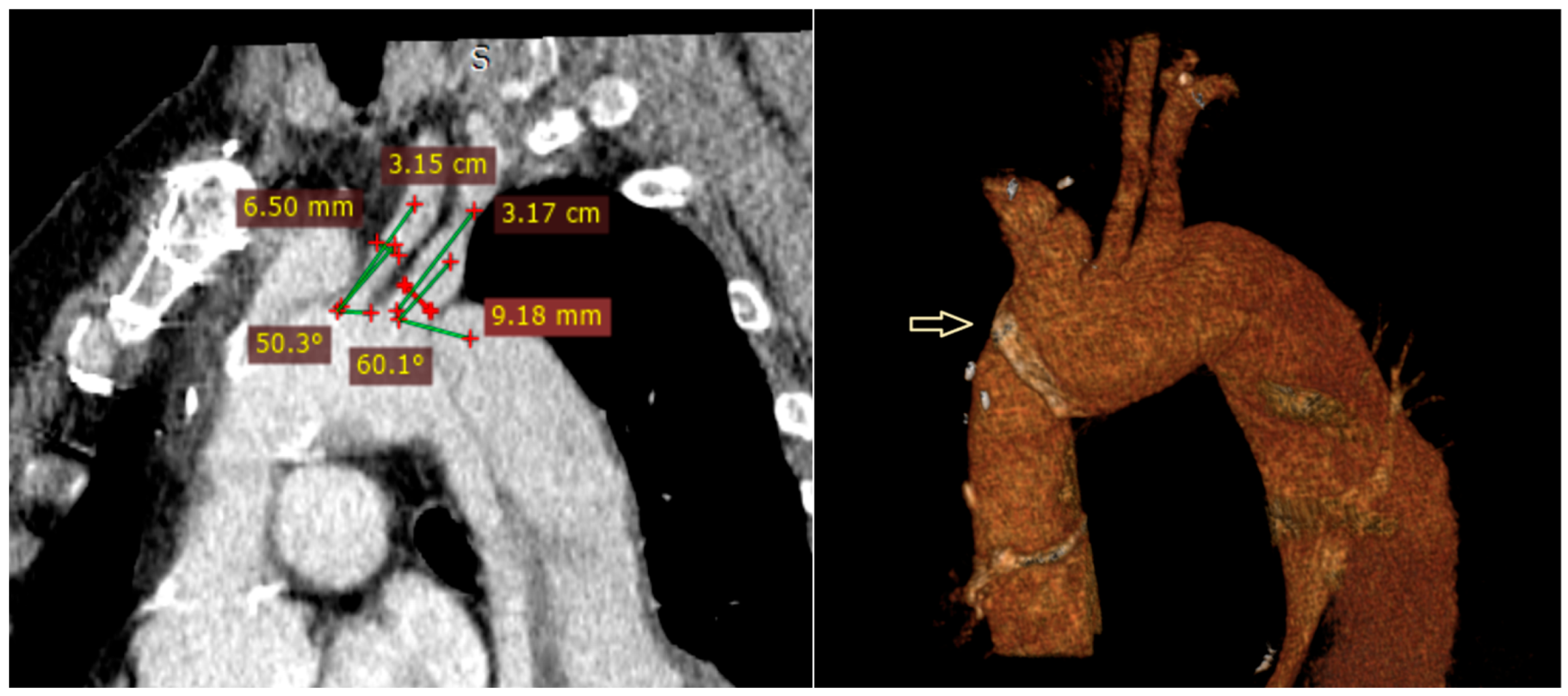

Preoperative planning included requesting CT images with the thinnest possible slices (preferably 0.625 mm) to ensure high-quality imaging. The inner and outer diameters of the peripheral vessels used for access, as well as the distances from the access site to the target vessels, were measured. The aortic neck length, diameter, and the angles with the supra-aortic branches were evaluated using multiplanar projections [

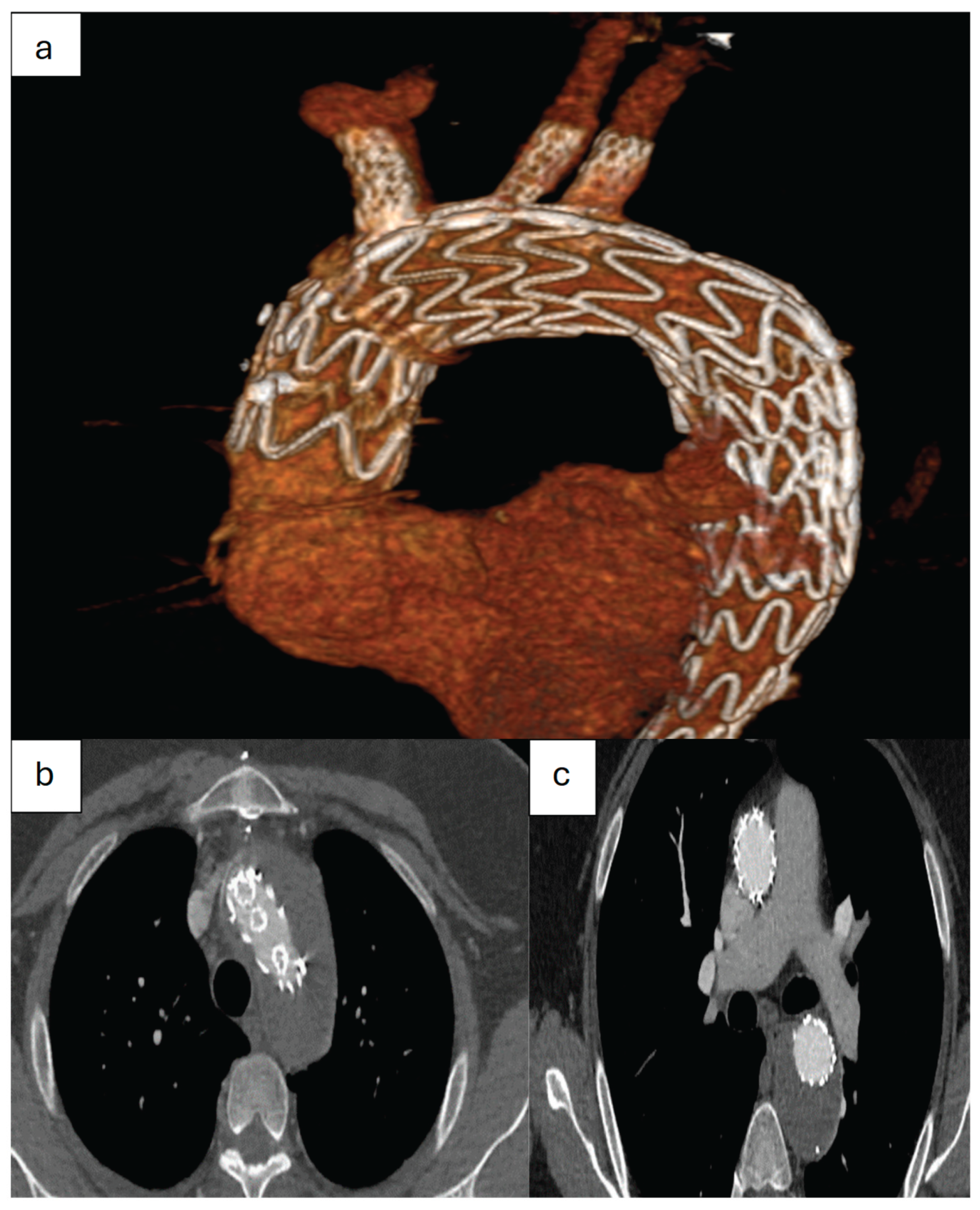

3]. In

Figure 1, the preoperative tomographic measurements and 3D angiography of a patient are presented as an example.

2.2.1. Preparation and Perfusion Strategy

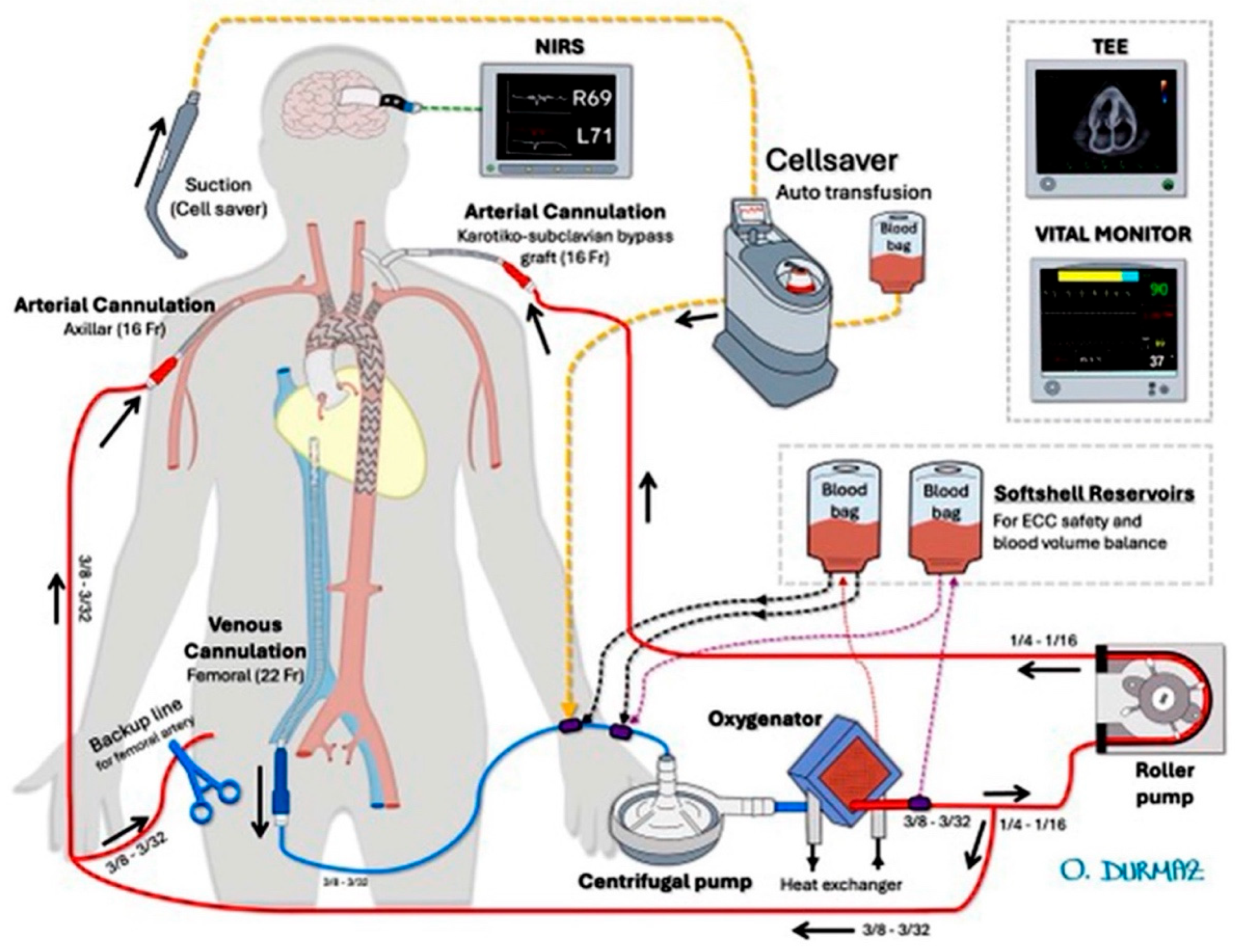

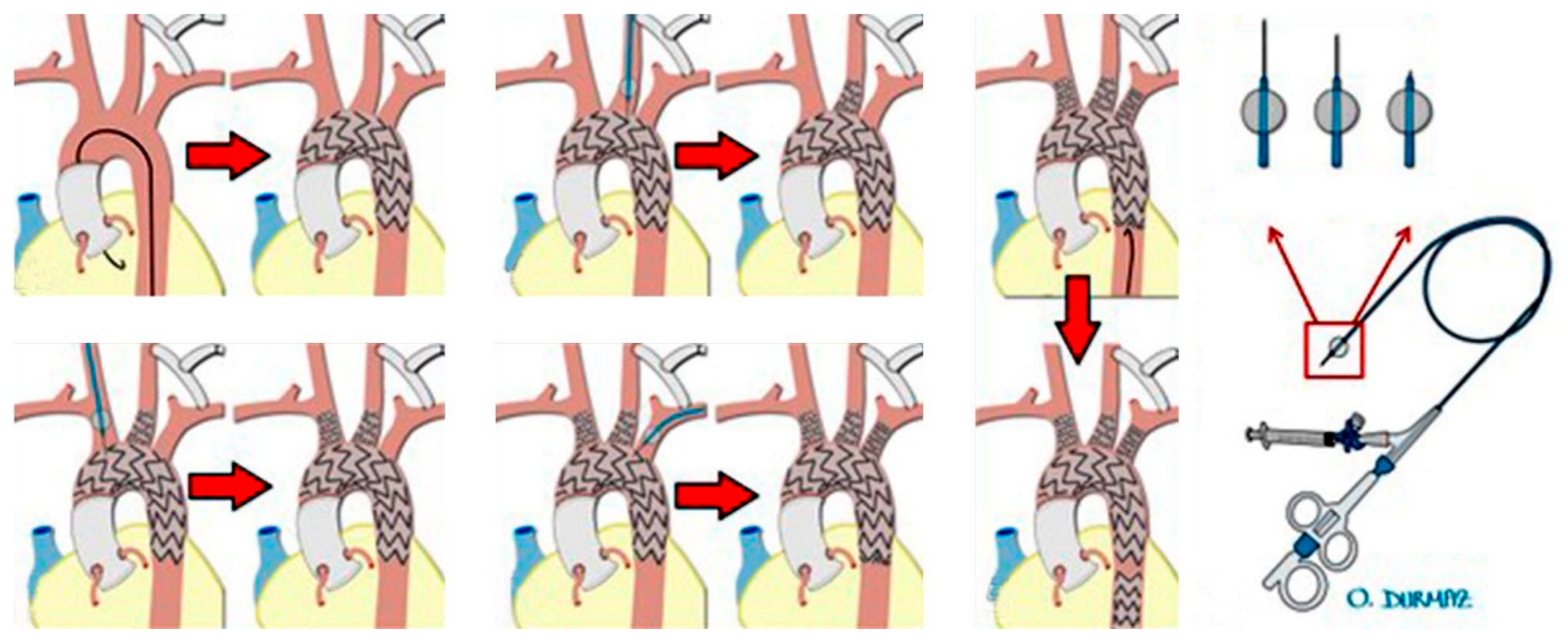

In our previously published articles, we have described the surgical technique in detail [

5,

6] In the mentioned case report, the configuration of cerebral perfusion strategies is illustrated in

Figure 2, while the details of the intraoperative endovascular procedure are depicted in

Figure 3.

All patients had a cerebrospinal fluid catheter placed by a neurosurgeon under general anesthesia, and cerebrospinal fluid pressure was maintained below 15 mmHg throughout the operation. Transesophageal echocardiography (TOE) was used to ensure accurate deployment of the stent graft. Regional cerebral oxygen saturation was monitored using near-infrared spectroscopy (INVOS 5100C, Somanetics, Troy, MI, USA).

For vascular access, bilateral femoral and carotid arteries, the right axillary artery, and the left brachial artery were exposed via cutdown. A left carotid-subclavian bypass was performed, and an 8-mm Dacron graft was interposed for antegrade perfusion. A 16-French arterial cannula was placed into the interposed graft, and another into the right axillary artery. A 20-French venous cannula was placed into the femoral vein, extending to the right atrium. Heparinization was performed to achieve an activated clotting time >350 seconds. Selective cerebral perfusion was maintained at a flow rate of 10 mL/kg/min, with a circuit pressure of 100–150 mmHg and a blood temperature of 34°C.

2.2.2. Endovascular Aortic Arch In Situ Fenestration Technique

The Ankura (Lifetech Scientific, Shenzhen, China) thoracic stent graft was used in all cases because its flexibility and compatibility with the puncture system have been demonstrated in clinical studies [

3,

6] which is also supported by our own clinical experience. After initiating selective cerebral perfusion and, if necessary, rapid pacing, the stent graft was deployed. The left common carotid artery and right carotid artery were punctured using a self-centering balloon catheter and an adjustable 20-gauge needle (FuThrough; Lifetech Scientific, Shenzhen, China) via the Seldinger technique.

For left subclavian artery fenestration, a steerable sheath (Fustar; Lifetech Scientific, Shenzhen, China) was placed in the left brachial artery, and fenestration was performed by direct contact with the outer curvature of the stent. After fenestration, a 0.018 or 0.035 guidewire was advanced into the ascending aorta. Balloon dilation was performed, and chrome-cobalt-ePTFE stent grafts (BeGraft; Bentley, Hechingen, Germany), oversized by 10%, were implanted into each arch branch.

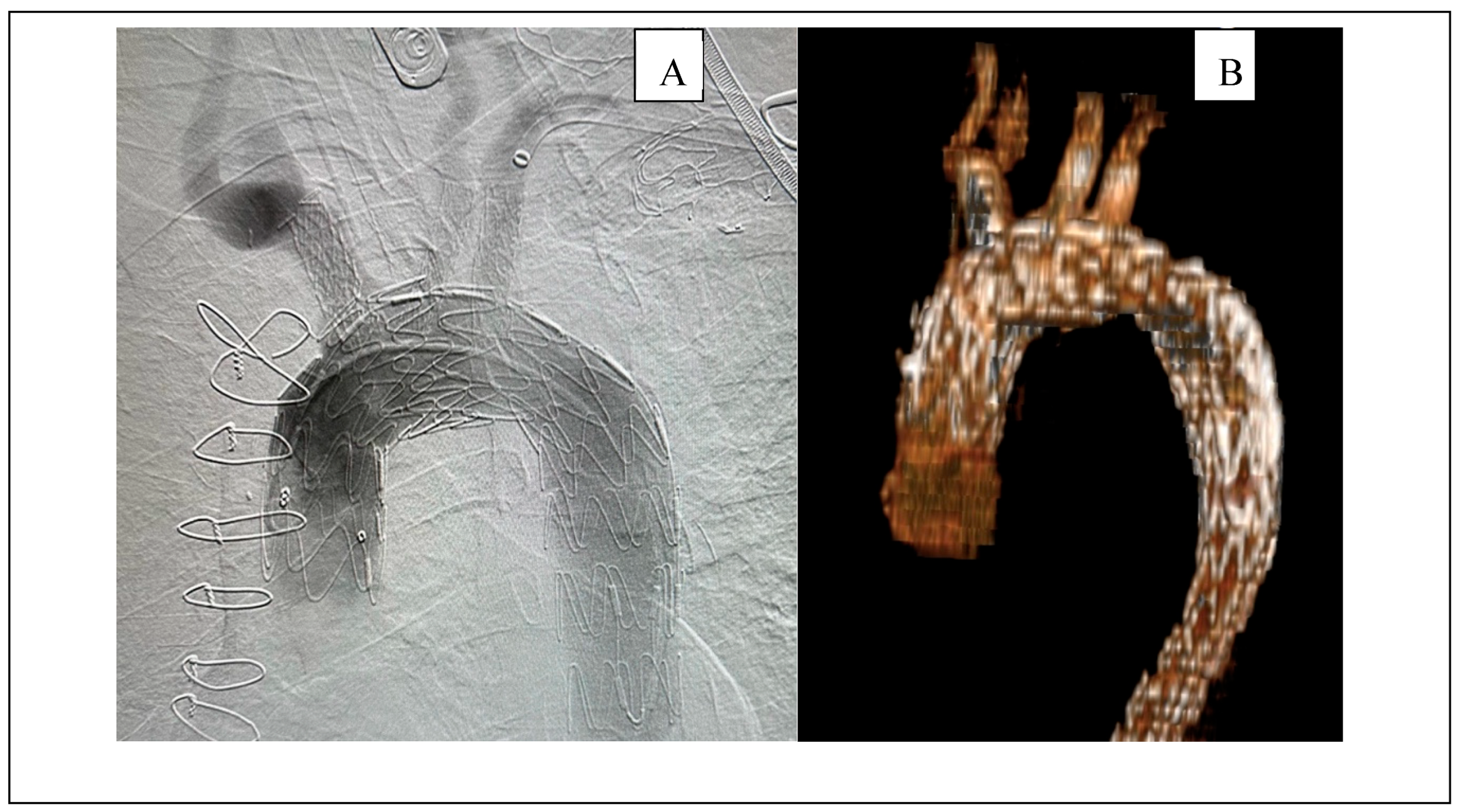

After confirming satisfactory bilateral carotid and vertebral blood flow, selective cerebral extracorporeal circulation was gradually discontinued while ensuring adequate near-infrared spectroscopy levels. Subsequently, control angiography was performed to assess the patency of the arch arteries and to check for any endoleaks. The post-procedural follow-up digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and the 3D reconstruction of angiographic imaging for a patient are demonstrated in

Figure 4.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (minimum–maximum), depending on the distribution. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version XX, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

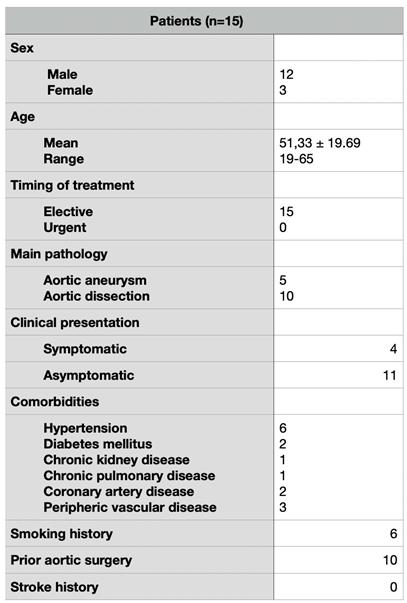

Technical success was achieved in all fifteen patients (100%), and all procedures were completed as planned. Twelve of all patients were male, with a mean age of 51.33 ± 19.69 years. All cases were elective. No emergency cases were included due to the need for detailed preoperative planning.Five patient had an aortic aneurysm, while the others had aortic dissection. Dissection patients were those with a previous history of open surgical interventions, such as tubular graft implantation in the ascending aorta or the Bentall procedure, who underwent endovascular intervention in the aortic arch due to residual dissection (

Table 1).

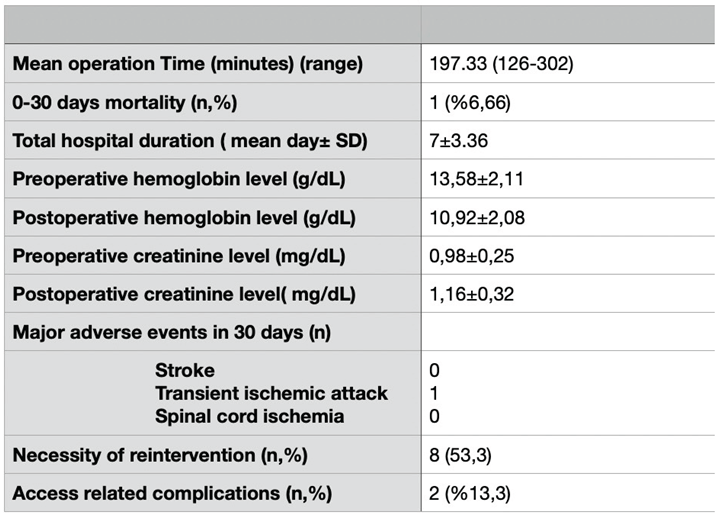

Some outcomes associated with the procedure are presented in

Table 2. During the early postoperative intensive care monitoring period, one patient experienced cardiac arrest and, despite resuscitation efforts, the patient unfortunately passed away. The exact cause of death could not be definitively determined.

The total operation time, which includes the duration from when the patient is placed on the operating table to their transfer to the intensive care unit, was on average 197.33 minutes (ranging from 126 to 302 minutes). The average hospital stay for the patients was 7±3.36 days. In cases that were all elective, preoperative hemoglobin levels were targeted to be high, with an average of 13.58±2.11 grams/ deciliter. There was no significant bleeding during the procedure, and postoperative levels were found to be 10.92±2.08 gr/dL.

Postoperative digital subtraction angiography (DSA) revealed no endoleak at the fenestration site related to the procedure, and no reintervention was required for the aortic arch during follow-up.

Figure 5 demonstrates a 6-month follow-up computed tomography scan highlighting the procedural success. Appropriate contrast enhancement is observed within the stents of the fenestrated arch branches, and the false lumen in the descending aorta is completely thrombosed.

Despite the overall procedural success, in 8 patients with a history of prior aortic intervention involving the ascending aorta, postoperative computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the need for reintervention in the descending aorta. To reinforce the true lumen and optimize aortic remodeling, the STABILISE (stent-assisted balloon-induced intimal disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair) technique was successfully employed in these cases.

One patient experienced a transient ischemic attack, and one had a minor hematoma at the brachial incision site, which resolved with conservative management. No cases of stroke, spinal cord ischemia, or major complications were observed (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Surgical interventions for aortic arch pathologies, such as aneurysms and dissections, are complex due to the involvement of critical vessels supplying the brain and upper extremities. This complexity contributes to the high mortality and morbidity rates associated with aortic arch interventions. Isolated aortic arch pathologies are rare and often occur as part of more extensive disease involving the ascending or descending aorta. Reintervention may be required after open surgery for Type A dissections or following TEVAR due to retrograde dissections [

7]

Recent literature indicates that, in 10% to 50% of TEVAR procedures, the intervention may need to be extended proximally, often necessitating the intentional occlusion of the subclavian artery [

2,

6,

8]. Revascularization of the left subclavian artery during TEVAR remains controversial. In the first United States regulatory trial [

9], it advocated prophylactic revascularization for all patients if the LSA is to be occluded during TEVAR, but this has not been fully adopted in clinical practice. While some surgeons perform routine prophylactic revascularization, others choose to perform revascularization only in selected patients. Additionally, some apply revascularization post-procedurally in clinical practice if symptoms of left arm ischemia or subclavian steal syndrome occur following TEVAR [

10,

11,

12]. Alternative endovascular methods, such as chimney, modified endografts, branched or fenestrated endografts, and ISF, have recently contributed to the literature as alternatives to traditional methods like transposition or left carotid-subclavian bypass for LSA revascularization [

3,

6,

13].

After his in vivo and in vitro studies, Richard G McWilliams published the first clinical case report on the in-situ stent-graft technique for LSA revascularization during TEVAR in 2004, and subsequent studies in this area have continued to increase [

14,

15].Various techniques such as needle, laser, and radiofrequency fenestration have been described, and short-term successful outcomes with low fenestration-related morbidity rates have been published. This topic continues to remain important in the literature [

6,

16].The question of which technique is superior to another remains a gray area. In our clinical practice, we use needle fenestration. Another important factor affecting the success of fenestration is patient selection and stent choice. Patient selection should be made carefully, considering significant studies [

3,

17].in the literature that define anatomical suitability. With this in mind, and as we detailed in the case report [

5] we published as the first in Turkey, we prefer to use the AnkuraTM device (Lifetech Scientific, Shenzhen, China). The stent’s thin double-layer structure made with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) and the significant flexibility provided by its supporting nitinol layer are its most important features, allowing it to adapt optimally to the curvature of the arch [

5,

6].

Surgical management of aortic arch pathologies, particularly those requiring circulatory arrest and cerebral protection, remains highly complex and technically demanding. Although total arch replacement performed under deep hypothermia (<18°C) was introduced in the 1970s to minimize cellular injury, this approach was associated with a significant risk of neurological complications. More recently, optimal cerebral protection strategies—such as the combination of antegrade and retrograde perfusion—have been shown to further reduce perioperative risk [

18]. Despite these advances, open arch surgery continues to pose substantial challenges and requires considerable surgical expertise, prompting increased interest in endovascular alternatives.

The literature on endovascular repair of the aortic arch is rapidly expanding. For example, Sonesson et al.[

19] reported favorable early outcomes with TEVAR in patients with residual dissection following ascending aorta replacement, utilizing bilateral carotid cannulation and centrifugal pump support for cerebral perfusion. In our series, we adopted a similar approach by providing simultaneous perfusion to both the left carotid artery and the left subclavian artery using a roller pump and a dedicated Dacron graft, aiming to minimize cerebrovascular complications through bilateral selective perfusion.

Our initial experience with total endovascular arch repair in a small cohort has been encouraging, demonstrating high technical success, low complication rates, and short hospital stays. However, the lack of long-term follow-up data remains a limitation, and further studies with larger patient populations are warranted to validate these findings.

Study Limitations

The fact that the study is a single-center, retrospective study and the potential generalization of the results are important limiting points. Reflecting early outcomes in a small patient population and the need for long-term follow-ups are other important points. The fact that it was conducted using only one type of stent, the Ankura, could lead to biased results. Additionally, the small cohort and physician references could lead to significant bias in the findings. Future studies should take these limitations into account and focus on a broader perspective, including a larger patient population and long-term outcomes.

5. Conclusions

It has been observed that advancements in endovascular techniques and technological designs can lead to successful outcomes in complex anatomical regions such as the aortic arch. Careful patient selection and detailed procedure planning restrict the use of the procedure in emergency cases. Surgeons should also remember that the relevant center must have significant experience in both open surgical and endovascular procedures. Despite all these challenges, our study is important in demonstrating that the in situ needle fenestration technique can be effective and feasible in cases of total aortic arch. However, it should be emphasized again that it needs to be supported by a larger patients population, multicenter studies, and long-term patient datas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and E.Ö.; methodology, F.A.,E.Ö.; software, O.D.A.F.K.; validation, F.A.,E.Ö.,M.C.S. formal analysis, F.A.,O.B.,S.A.B.; investigation, F.A.; resources, F.A.,A.G.; data curation, F.A.,M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.; writing—review and editing,F.A.; visualization, A.İ.H.,N.D.; supervision, L.Y.,S.E.; project administration, E.Ö.,F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective single-center study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The human research ethics committee details include the date of approval (21 March 2025) and protocol number (2025/227).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the dedicated members of the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, including the perfusionist team (Altan Ada, Emre Özsoylu, and Semih Tezeren), the cardiovascular nursing team (Fulya Atak, Mustafa Kuyucu, and Ahmet Atıcı), and the hybrid technician team (Barbaros Karadogan). We are especially grateful to Ferhat Özsar for his invaluable contributions to these cases and his exceptional support in all other endovascular procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1-Sun, X.; Kan, Y.; Huang, L.; Dong, Z.; Guo, D.; Si, Y.; Fu, W. Evaluation for the safety and effectiveness of the in situ fenestration system in TEVAR for aortic arch pathologies: Protocol for a prospective, multicentre and single-arm study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043599. [CrossRef]

- 2-Shu, C.; Fan, B.; Luo, M.; Li, Q.; Fang, K.; Li, M.; Li, X.; He, H.; Wang, T.; Yang, C.; et al. Endovascular treatment for aortic arch pathologies: Chimney, on-the-table fenestration, and in-situ fenestration techniques. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 1437–1448. [CrossRef]

- 3-Piffaretti, G.; Franchin, M.; Gnesutta, A.; Gatta, T.; Piacentino, F.; Rivolta, N.; Lomazzi, C.; Bissacco, D.; Fontana, F.; Trimarchi, S. Anatomic Feasibility of In-Situ Fenestration for Isolate Left Subclavian Artery Preservation during Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair Using an Adjustable Needle Puncturing System. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 162. [CrossRef]

- 4-Li C, Xu P, Hua Z, et al. Early and midterm outcomes of in situ laser fenestration during thoracic endovascular aortic repair for acute and subacute aortic arch diseases and analysis of its complications. J Vasc Surg 2020.

- 5-Özçınar E.,Yazıcıoğlu L.,Dikmen N.,DurmazO.,GuvenA.,Sarıcaoğlu M.C.,AkçaF.,AdaA. Selective cerebral extracorporeal Circulation-enhanced Total Endovascular Arch Replacement using İnsitu Fenestration TurkishJournalofThoracicandCardiovascularSurgery, 2024.

- 6-E. Ozcinar, N. Dikmen, C. Baran, O. Buyukcakir, et al. Comparative Retrospective Cohort Study of Carotid-Subclavian Bypass versus In Situ Fenestration for Left Subclavian Artery Revascularization during Zone 2 Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair: A Single-Center Experience.J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13(17), 5043. [CrossRef]

- 7-Xiaoye Lia, Wei Lib,Xiangchen Daic,et al. Thoracic Endovascular Repair for Aortic Arch Pathologies with Surgeon Modified Fenestrated Stent Grafts: A Multicentre Retrospective Study.ESVS Journal. Volume 62, Issue 5P758-766November 2021.

- 8-Okamoto, T.; Yokoi, Y.; Sato, N.; Suzuki, S.; Enomoto, T.; Onishi, R.; Nakamura, N.; Okubo, Y.; Nagasawa, A.; Mishima, T.; et al. Outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair using fenestrated stent grafts in patients with thoracic aortic distal arch aneurysms. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 65, ezae062. [CrossRef]

- 9-Michel S. Makaroun,Ellen D. Dillavou, et al. Endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic aneurysms: Results of the phase II multicenter trial of the GORE TAG thoracic endoprosthesis. Journal Of Vascular Surgery Volume 41, Number 1.

- 10-Buth, J. ∙ Harris, P.L. ∙ Hobo, R. Et al.Neurologic complications associated with endovascular repair of thoracic aortic pathology: Incidence and risk factorsa study from the European Collaborators on Stent/Graft Techniques for Aortic Aneurysm Repair (EUROSTAR) registry. J Vasc Surg. 2007; 46:1103-1110.

- 11-Peterson, B.G. ∙ Eskandari, M.K. ∙ Gleason, T.G et al.Utility of left subclavian artery revascularization in association with endoluminal repair of acute and chronic thoracic aortic pathology.J Vasc Surg. 2006; 43:433-439.

- 12-Jon S. Matsumura, Adnan Z. Rizvi. Left subclavian artery revascularization: Society for Vascular Surgery Practice Guidelines.JVS Volume 52, Issue 4, Supplement 65S-70SOctober 2010.

- 13-Redlinger, R.E.; Ahanchi, S.S.; Panneton, J.M. In situ laser fenestration during emergent thoracic endovascular aortic repair is an effective method for left subclavian artery revascularization. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 58, 1171–1177. [CrossRef]

- 14-Sean A Crawford, Ryan M Sanford et al. Clinical outcomes and material properties of in situ fenestration of endovascular stent grafts. Vasc Surg. 2016 Jul;64(1):244-50.

- 15-Wang LX, Zhou XS, Guo DQ, et al. A new adjustable puncture device for in situ fenestration during thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Endovasc Ther.2018;25:474–479. [CrossRef]

- 16-Mingyao Luo, Kun Fang, and Chang Shu. Midterm Results of Retrograde In Situ Needle Fenestration During Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair of Aortic Arch Pathologies. Journal of Endovascular Therapy, September 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- 17-Shu, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, E.; Wang, L.; Guo, D.; Chen, B.; Fu, W. Midterm Outcomes of an Adjustable Puncture Device for In Situ Fenestration During Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- 18-Xiaoying Lou, Edward P Chen. Optimal Cerebral Protection Strategies in Aortic Surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Jan 8;31(2):146–152.

- 19-Björn Sonesson, Tim Resch, Mats Allers, Martin Malina Endovascular total aortic arch replacement by in situ stent graft fenestration technique. J Vasc Surg.2009 Jun;49(6):1589-91.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).