1. Introduction

Although open repair is the “gold standard” for treating aortic arch diseases [

1], thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) has been shown to be a safe and effective alternative for patients with aortic arch aneurysms who have a high surgical risk. The procedure, which involves proximal landing zone 2, requires options such as debranching, fenestration, or the chimney technique to ensure perfusion of the left subclavian artery (LSCA). However, debranching requires an extra-anatomical bypass [

2], and aneurysms involving supra-aortic branches are not optimal candidates for fenestration of the endoprosthesis [

3]. Moreover, the chimney technique is associated with a high risk of gutter endoleaks and stent-graft migration [

4]. At our institution, we perform physician-modified inner-branched endovascular repair (PMiBEVAR) in these cases, using an inner branch and bridging stent-graft to ensure perfusion of the LSCA.

Recently, the use of PMiBEVAR for aortic arch aneurysm has been increasingly reported. For example, Zhang et al. [

5] described a case of successful total endovascular repair of an aortic arch aneurysm using a physician-modified endograft with triple inner branches. Although acceptable initial outcomes after PMiBEVAR for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm have been reported [

6], clinical studies regarding PMiBEVAR for aortic arch aneurysms are currently limited. Herein, we evaluate the initial outcomes of six cases in which PMiBEVAR was performed at proximal landing zone 2.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective study analyzed data from six patients who underwent PMiBEVAR for distal aortic arch aneurysms at a single academic medical center between October 2021 and June 2024.

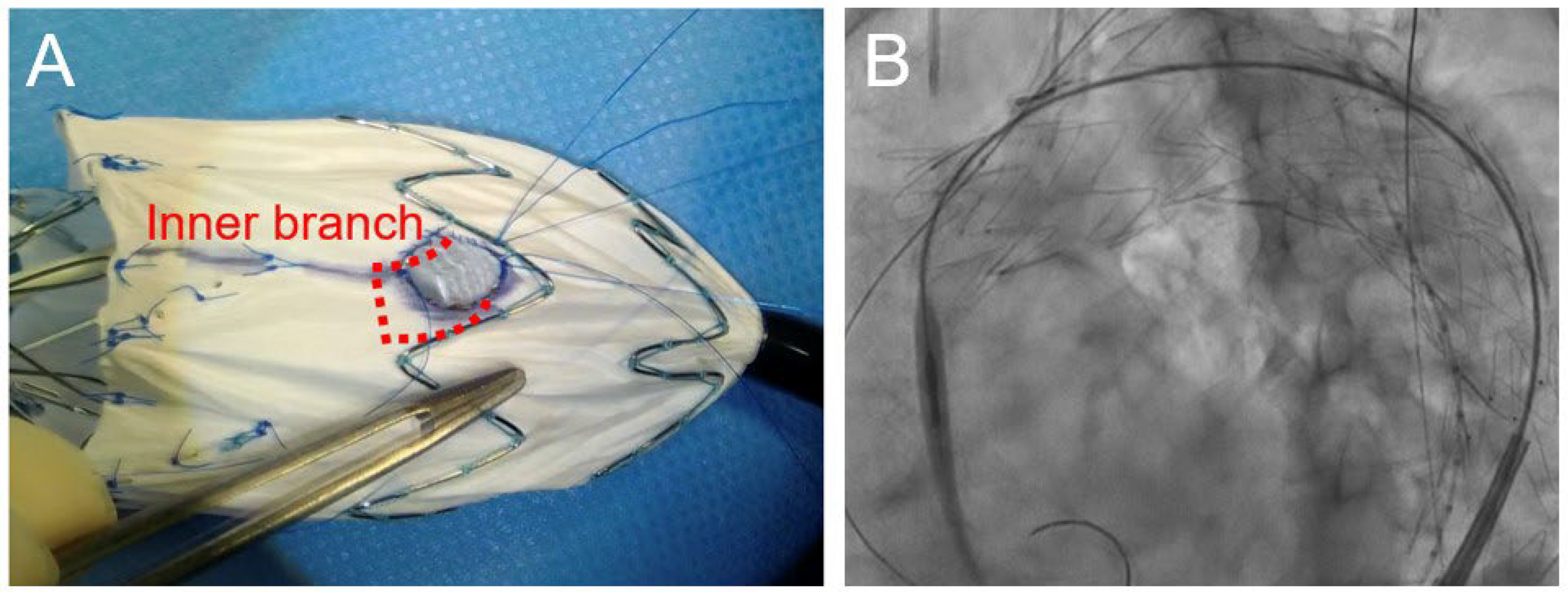

Modification of the stent-grafts was performed by two cardiovascular surgeons. The thoracic stent-graft was partially unloaded using a delivery system and the proximal barb was removed. Based on measurements from preoperative computed tomographic (CT) angiography, electrocautery was used to create a fenestration in a predetermined location on the LSCA to match the curve of the greater curvature of the aortic arch. The inner branch of the LSCA was prepared using a Viabahn® stent-graft (WL Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) cut to 10–15 mm and securely affixed to the fenestration using running 5-0 Ethibond® or Prolene® sutures (Ethicon, Inc., Bridgewater, NJ, USA), using an Azur® coil (Terumo Medical, Tokyo, Japan) or ONE Snare® (Merit Medical, Tokyo, Japan) as a marker. To enable the approximation of the direction of physiologic blood flow, the inner branch was not fixed to the main device. Subsequently, the modified stent-graft was manually resheathed while tightening the graft with vascular tape. The physician-modified stent-graft was then advanced into the aortic arch via the femoral artery. After unsheathing to open the fenestration, the bridging stent-graft was inserted into the inner branch of the LSCA from the left upper limb, while securing the main graft to avoid rotation during delivery. The surgical criteria did not deviate from the global standards [7, 8].

The primary outcomes of this study were 30-day mortality and postoperative complications. We routinely performed postoperative CT to check whether any endoleaks occurred within 1 week. After discharge, we continued follow-up using plain CT at 6–8 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively and annually thereafter. Decisions regarding reintervention were made based on the following factors: aneurysm growth of >5 mm when compared with the preoperative measurement, the presence or absence of type I or type III endoleaks, graft migration, graft occlusion, rupture, and infection. If endovascular reintervention was not suitable due to anatomical problems or reintervention failure, conversion to open surgery was performed. Aortic remodeling was classified as follows: shrinkage (a diameter reduction of ≥5 mm), no change (a diameter reduction or increase of <5 mm), and enlargement (a diameter increase of ≥5 mm).

2.1. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro version 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation when normally distributed and median (interquartile range [25–75%]) when non-normally distributed.

2.2. Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of our university (no. 362-25). The requirement for informed consent was waived as no identifiable patient information was used.

3. Results

The preoperative characteristics of the patients are listed in

Table 1. The median age was 78.5 (76.5–79.0) years, and 4/6 (66.7%) patients were male. The median aneurysm size was 56 (50–61) mm, and all patients had hypertension. Surgical risks tended to be higher.

Regarding the procedural details (

Table 2), the median modification and operative times were 56 (45–60) min and 92 (79–308) min, respectively. The Zenith Alpha™ thoracic stent-graft (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was used in most patients, whereas the Relay®Plus thoracic stent-graft (Terumo Aortic, Sunrise, FL, USA) was used in only one patient. In all patients, the inner branch of the LSCA was prepared using a Viabahn® stent-graft (WL Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), which was securely affixed to the fenestration (

Figure 1A). The bridging stent-grafts used for the LSCA were as follows: LifeStream™ (Becton, Dickinson and Bard Company, Tempe, AZ, USA), Viabahn® VBX (WL Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), and Viabahn® (WL Gore & Associates). In all cases, endovascular treatment was achieved through a percutaneous approach to the access vessel, and the bridging stent-graft was inserted into the inner branch of the LSCA (

Figure 1B). Technical success was achieved in 5/6 (83.3%) cases. Open abdominal surgery was required in one patient due to access vessel bleeding.

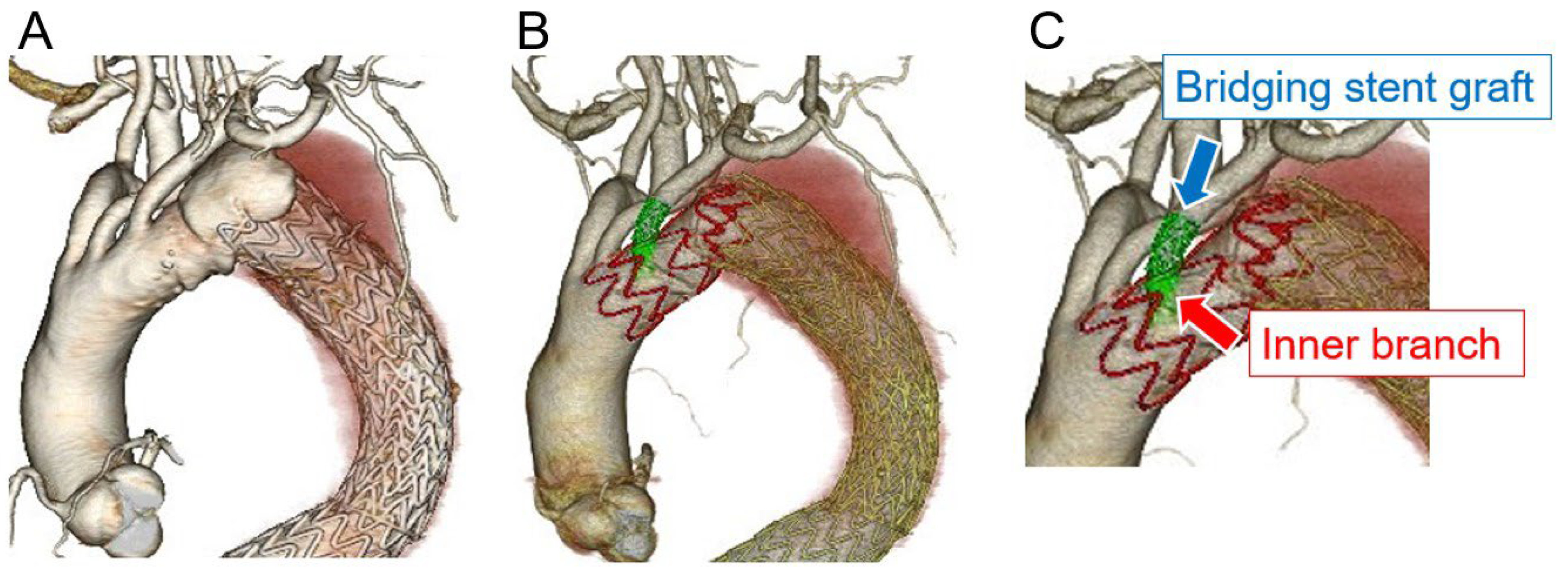

Figure 2 shows the CT images obtained pre- and postoperatively.

Table 3 shows the postoperative outcomes of the patients. In total, one patient developed a delayed type Ia endoleak and another experienced a vascular access-site complication. However, no patients experienced stroke, spinal cord ischemia, or any other complications. The median length of hospital stay was 10 (7–41) days, with no deaths occurring during hospitalization.

Table 4 shows the post-discharge follow-up outcomes. The median follow-up period was 12.5 (7.3–25) months. Notably, the aneurysm diameter remained “unchanged” in four patients, including the patient with a delayed type Ia endoleak. The two other patients experienced aneurysm diameter shrinkage. Of the six patients, one died due to respiratory failure.

4. Discussion

Our study findings show the feasibility of PMiBEVAR for distal aortic arch aneurysm. TEVAR at proximal landing zone 2 requires LSCA revascularization. In this study, we considered PMiBEVAR to be a minimally invasive and acceptable procedure when compared to previous techniques such as debranching, fenestration, or the chimney technique, as all cases were performed using percutaneous approach, with a shorter operative time and no in-hospital deaths. In a previous study on the treatment of aortic arch aneurysm, no significant difference in 3-year mortality was found between the open aortic repair and hybrid TEVAR with debranching techniques [

9]. Conversely, Squiers et al. [

2] compared outcomes between a surgical debranching group and branched endograft group in zone 2 TEVAR and found that the procedural time was significantly longer for the surgical debranching group. Moreover, Tsilimparis et al. [

10] performed a retrospective review of fenestrated endoprosthesis for aortic arch diseases and found that the 30-day mortality after performing fenestrated TEVAR was 20%. Notably, aneurysms involving supra-aortic branches are not optimal candidates for fenestration of the endoprosthesis due to the risk of endoleaks [

3]. However, a previous dual-center study demonstrated acceptable outcomes of physician-modified thoracic stent-grafts with a single fenestration or a proximal scallop, with a 30-day mortality of 6% and aorta-related mortality of 6% [

11]. Furthermore, Huang et al. [

4] reported that type Ia endoleaks occurred in 17.8% of patients after zone 2 TEVAR using the chimney technique.

Custom-made endografts require 6–8 weeks for construction and delivery. Therefore, this technique cannot be used for emergency or urgent surgeries. Off-the-shelf grafts are immediately available and the procedure can be standardized. However, the grafts are not tailored to each patient, and additional procedures such as a bypass or a vascular plug are therefore required [

12]. Previously, Bosse et al. [

13] reported that five standardized off-the-shelf endografts could cover a majority of aortic arch anatomies. In contrast, physician-modified endografts have definite anatomical suitability because they are created specifically for each individual patient. Therefore, treatment of these patients can be completed using PMiBEVAR only. However, few previous studies have reported on PMiBEVAR for aortic arch aneurysm [

14]. Notably, Zhang et al. [

5] reported the successful application of a physician-modified endograft with triple inner branches for extensive aortic arch aneurysm. Postoperatively, they observed no endoleaks, and the aneurysm diameter shrinkage was showed during the 6-month follow-up [

5]. Moreover, an increasing amount of studies are reporting on PMiBEVAR for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms [

15,

16,

17], showing that PMiBEVAR is a feasible approach for treating complex aneurysms [

6].

Physician-modified stent-grafts can be attached at either the inner or outer branch; however, the inner branch is easier to cannulate from the LSCA than the outer branch. In addition, we believe that the landing length between the inner branch and the bridging stent-graft more effectively prevents type III endoleaks when compared with fenestration alone. Type III endoleaks from directional branches are a non-negligible complication after branched endovascular repair [

18]. Another advantage of using the inner branch technique is that the graft is easier to resheath, which is an important factor for physician-modified stent-grafts. However, if type Ia endoleaks occur, reintervention is more difficult due to the presence of the inner branch. Thus, although PMiBEVAR is an effective treatment for aortic arch diseases, the complex structure makes this approach more difficult when complications occur. Therefore, the optimal reintervention methods for PMiBEVAR need to be evaluated [

19,

20,

21].

As we accumulate more cases of PMiBEVAR, including that at zone 0 and zone 1, there is a possibility of improving techniques by introducing a stabilizing spine wire. Adding this wire is a crucial step in providing support and secure alignment of the device and branch openings along the outer curve of the aortic arch [

22]. In fact, modification techniques using a self-orienting spine trigger wire and anatomically specific fenestrations or inner branches have improved outcomes with regard to mortality, procedure time, and postoperative complications [

23].

This study had some limitations. First, this retrospective analysis was conducted in a small population at a single center. Second, zone 0 and 1 PMiBEVAR outcomes were not evaluated. Third, long-term follow-up was not performed.

In conclusion, our study findings have demonstrated that PMiBEVAR for distal aortic arch aneurysm has acceptable short-term outcomes and may be effective in improving initial postoperative outcomes. However, further large-scale and longer-term studies are required to confirm the safety and efficacy of proximal landing zone 2 PMiBEVAR.

Author Contributions

Writing-original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, T.S., Y. Iba., T.N., J.N., S.M., A.A., K.M., Y. Iwashiro, and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sapporo Medical University (no. 362-25 and May 28, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived as no identifiable patient information was used.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage for the English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shi, R.; Wooster, M. Hybrid and Endovascular Management of Aortic Arch Pathology. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 6248. [CrossRef]

- Squiers, J.J.; DiMaio, J.M.; Schaffer, J.M.; Baxter, R.D.; Gable, C.E.; Shinn, K.V.; Harrington, K.; Moore, D.O.; Shutze, W.P.; Brinkman, W.T.; et al. Surgical debranching versus branched endografting in zone 2 thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg 2022, 75, 1829–1836.e3. [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, A.; Caraffa, R.; Cibin, G.; Antonello, M.; Gerosa, G. Total endovascular aortic arch repair: From dream to reality. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58, 372. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ding, H.; Jiang, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, X.; Fan, R.; Luo, J.; Jiang, Z. Outcomes of chimney technique for aortic arch diseases: A single-center experience with 226 cases. Clin Interv Aging 2019, 14, 1829–1840. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Yang, P.; Hu, J. Physician-modified endograft with triple inner branches for extensive aortic arch aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther 2022, 29, 623–626. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Iba, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Nakazawa, J.; Ohkawa, A.; Hosaka, I.; Arihara, A.; Tsushima, S.; Ogura, K.; Yoshikawa, K.; et al. Initial outcomes of physician-modified inner branched endovascular repair in high-surgical-risk patients. J Endovasc Ther 2023, 15266028231169183. [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, G.R. Jr.; Escobar, G.A.; Azizzadeh, A.; Beck, A.W.; Conrad, M.F.; Matsumura, J.S.; Murad, M.H.; Perry, R.J.; Singh, M.J.; Veeraswamy, R.K.; et al. Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2021, 73, 55S–83S. [CrossRef]

- Ogino, H.; Iida, O.; Akutsu, K.; Chiba, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Kaji, S.; Kato, M.; Komori, K.; Matsuda, H.; et al. JCS/JSCVS/JATS/JSVS 2020 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection. Circ J 2023, 87, 1410–1621. [CrossRef]

- Iba, Y.; Minatoya, K.; Matsuda, H.; Sasaki, H.; Tanaka, H.; Oda, T.; Kobayashi, J. How should aortic arch aneurysms be treated in the endovascular aortic repair era? A risk-adjusted comparison between open and hybrid arch repair using propensity score-matching analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014, 46, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Tsilimparis, N.; Debus, E.S.; von Kodolitsch, Y.; Wipper, S.; Rohlffs, F.; Detter, C.; Roeder, B.; Kölbel, T. Branched versus fenestrated endografts for endovascular repair of aortic arch lesions. J Vasc Surg 2016, 64, 592–599. [CrossRef]

- Canaud, L.; Baba, T.; Gandet, T.; Narayama, K.; Ozdemir, B.A.; Shibata, T.; Alric, P.; Morishita, K. Physician-modified thoracic stent-grafts for the treatment of aortic arch lesions. J Endovasc Ther 2017, 24, 542–548. [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, A.; Cibin, G.; Antonello, M.; Battocchio, P.; Piazza, M.; Caraffa, R.; Dall’Antonia, A.; Grego, F.; Gerosa, G. Endovascular exclusion of the entire aortic arch with branched stent-grafts after surgery for acute type A aortic dissection. JTCVS Tech 2020, 3, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bosse, C.; Kölbel, T.; Mougin, J.; Kratzberg, J.; Fabre, D.; Haulon, S. Off-the-shelf multibranched endograft for total endovascular repair of the aortic arch. J Vasc Surg 2020, 72, 805–811. [CrossRef]

- Yordanov, M.D.; Oberhuber, A.; Ibrahim, A. Physician-Modified TEVAR versus Hybrid Repair of the Proximal Descending Thoracic Aorta. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 3455. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Kawaharada, N.; Yasuhara, K.; Naraoka, S. Physician-modified stent graft with inner branches for treating ruptured thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2022, 61, 952–954. [CrossRef]

- D’Oria, M.; Mirza, A.K.; Tenorio, E.R.; Kärkkäinen, J.M.; DeMartino, R.R.; Oderich, G.S. Physician-modified endograft with double inner branches for urgent repair of supraceliac para-anastomotic pseudoaneurysm. J Endovasc Ther 2020, 27, 124–129. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Iba, Y.; Yasuhara, K.; Kuwada, N.; Katada, Y.; Hashiguchi, H.; Uzuka, T.; Hosaka, I.; Nakajima, T.; Kawaharada, N. Multicentre retrospective analysis of physician-modified fenestrated/inner-branched endovascular repair for complex aortic aneurysms. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2024, ezae404. [CrossRef]

- Gennai, S.; Simonte, G.; Mattia, M.; Leone, N.; Isernia, G.; Fino, G.; Farchioni, L.; Lenti, M.; Silingardi, R. Analysis of predisposing factors for type III endoleaks from directional branches after branched endovascular repair for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2023, 77, 677–684. [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, S.; Shibata, T.; Kawaharada, N. Physician-modified inner-branched endovascular repair with re-intervention. Vascular 2024, 17085381241236569. PMID: 38409764. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, D.; Aburamileh, A.; Rimon, U.; Raskin, D.; Khaitovich, B.; Halak, M. Secondary interventions after fenestrated and branched endovascular repair of complex aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2020, 72, 866–872. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, N.; Kölbel, T.; Dias, N.V.; Verhoeven, E.; Wanhainen, A.; Gargiulo, M.; Oikonomou, K.; Verzini, F.; Heidemann, F.; Sonesson, B.; et al. Revascularization of occluded renal artery stent grafts after complex endovascular aortic repair and its impact on renal function. J Vasc Surg 2021, 73, 1566–1572. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.B.; Porras-Colon, J.; Scott, C.K.; Chamseddin, K.; Baig, M.S.; Timaran, C.H. Early results and feasibility of total endovascular aortic arch repair using 3-vessel company-manufactured and physician-modified stent-grafts. J Endovasc Ther 2024, 31, 1197–1207. [CrossRef]

- DiBartolomeo, A.D.; Kazerounim, K.; Fleischman, F.; Han, S.M. The initial results of physician-modified fenestrated-branched endovascular repairs of the aortic arch and lessons learned from the first 21 cases. J Endovasc Ther 2024, 15266028241255539. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 38778636. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).