Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

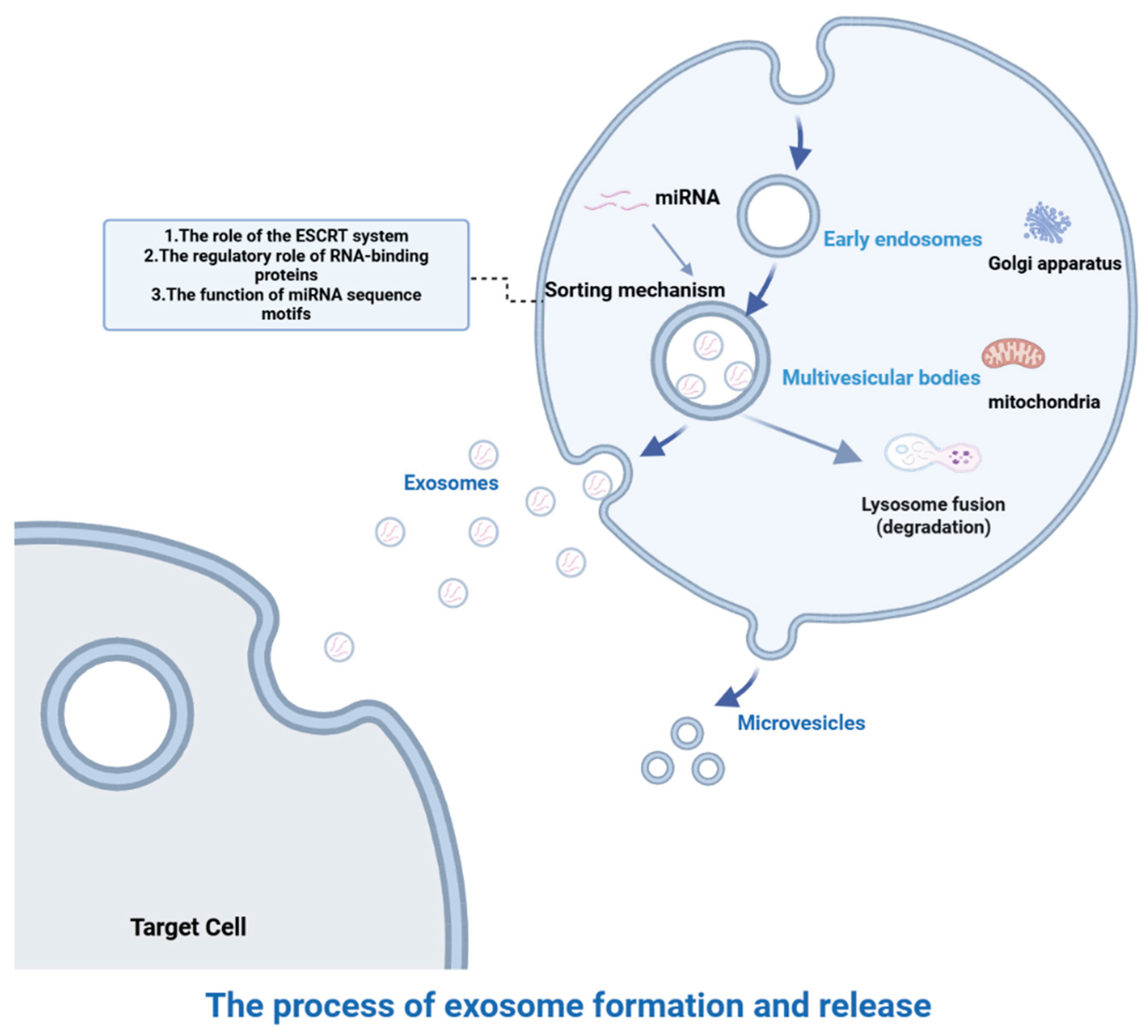

2. Biogenesis and miRNA Sorting of Exosomes

3. Cancer and Cancer Stem Cells

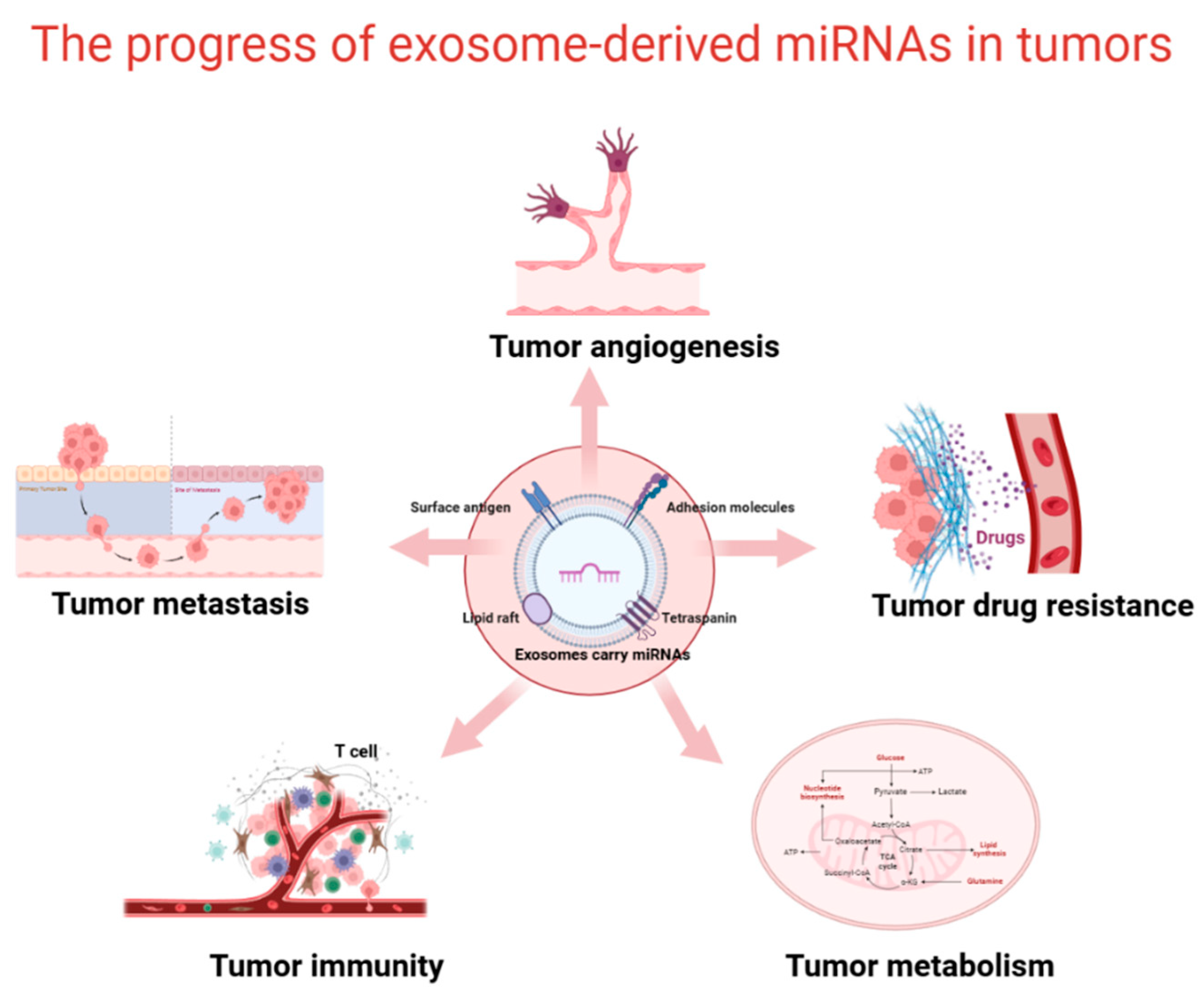

4. Role of Exosomal miRNAs in Cancer

4.1. Promotion of Tumor Growth and Metastasis

4.2. Promotion of Tumor Angiogenesis

4.3. Promotion of Tumor Chemoresistance

4.4. Promotion of Tumor Immunosuppression

4.5. Promotion of Tumor Metabolism

4.6. Regulation of Autophagy

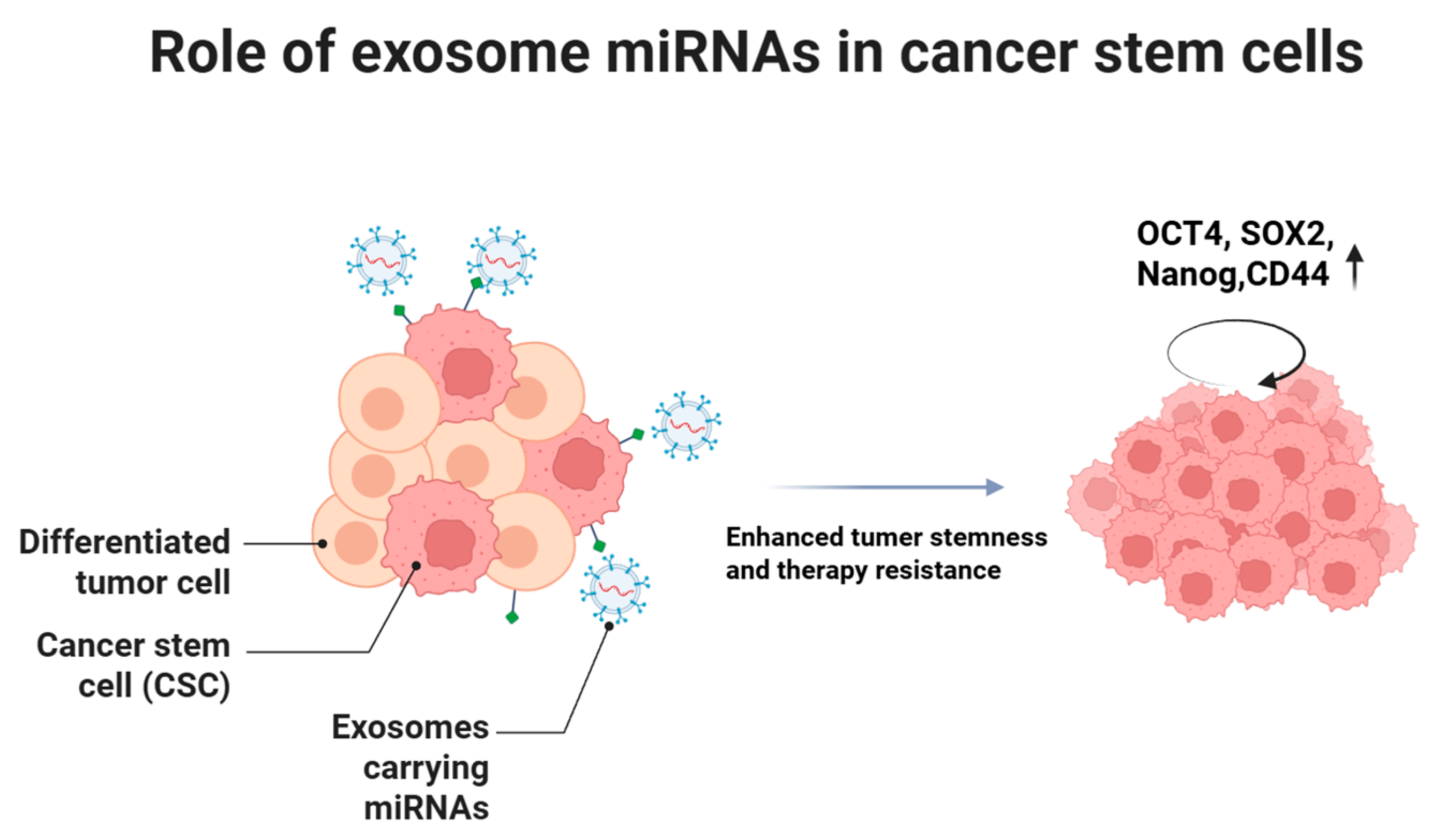

5. Roles of Exosomal miRNAs in Cancer Stem Cells

5.1. Maintenance of CSC Stemness Characteristics and Self-Renewal

5.2. Mediation of CSC Therapy Resistance

6. Translational Applications of Exosomal miRNAs in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy

6.1. Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers

6.2. Potential Therapeutic Targets

6.2.1. Targeted Delivery of Exosomal miRNAs to Tumor Cells

6.2.2. Targeted Delivery of Exosomal miRNAs to Cancer Stem Cells

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Song, X.; Xu, D.; Tiek, D.; Goenka, A.; Wu, B.; Sastry, N.; Hu, B.; Cheng, S.Y. Stem cell programs in cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8721–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, G.R.; Sethi, I.; Sadida, H.Q.; Rah, B.; Mir, R.; Algehainy, N.; Albalawi, I.A.; Masoodi, T.; Subbaraj, G.K.; Jamal, F.; et al. Cancer cell plasticity: from cellular, molecular, and genetic mechanisms to tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2024, 43, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, N.; Akiyoshi, K.; Shiku, H. Exosome-mediated regulation of tumor immunology. Cancer Sci 2018, 109, 2998–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhou, T.; Chen, J.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Luo, S.; Chen, D.; Cai, C.; Li, W. The role of Exosomal miRNAs in cancer. J Transl Med 2022, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.X. Roles of miRNAs in regulating ovarian cancer stemness. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2024, 1879, 189191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Varshney, A.; Bajaj, R.; Pokharkar, V. Exosomes as New Generation Vehicles for Drug Delivery: Biomedical Applications and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; El Andaloussi, S.; Wood, M.J. Exosomes and microvesicles: extracellular vesicles for genetic information transfer and gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, R125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.H. ESCRTs are everywhere. Embo j 2015, 34, 2398–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adell, M.A.; Vogel, G.F.; Pakdel, M.; Müller, M.; Lindner, H.; Hess, M.W.; Teis, D. Coordinated binding of Vps4 to ESCRT-III drives membrane neck constriction during MVB vesicle formation. J Cell Biol 2014, 205, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Buchkovich, N.J.; Henne, W.M.; Banjade, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Emr, S.D. ESCRT-III activation by parallel action of ESCRT-I/II and ESCRT-0/Bro1 during MVB biogenesis. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, C.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Chen, D.; Li, W. Exosomes in HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2021, 16, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krylova, S.V.; Feng, D. The Machinery of Exosomes: Biogenesis, Release, and Uptake. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, N.; Iguchi, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takeshita, F.; Matsuki, Y.; Ochiya, T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 17442–17452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, N.; Iguchi, H.; Hagiwara, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takeshita, F.; Ochiya, T. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)-dependent exosomal transfer of angiogenic microRNAs regulate cancer cell metastasis. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 10849–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Zou, W.; Chen, X.; Roizman, B.; Zhou, G.G. hnRNPA2B1 Associated with Recruitment of RNA into Exosomes Plays a Key Role in Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Release from Infected Cells. J Virol 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zeng, Z.; Song, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Ke, X.; Hu, X. YBX-1 mediated sorting of miR-133 into hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced EPC-derived exosomes to increase fibroblast angiogenesis and MEndoT. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurtleff, M.J.; Temoche-Diaz, M.M.; Karfilis, K.V.; Ri, S.; Schekman, R. Y-box protein 1 is required to sort microRNAs into exosomes in cells and in a cell-free reaction. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, A.J.; Hoshino, D.; Hong, N.H.; Cha, D.J.; Franklin, J.L.; Coffey, R.J.; Patton, J.G.; Weaver, A.M. KRAS-MEK Signaling Controls Ago2 Sorting into Exosomes. Cell Rep 2016, 15, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Villar-Prados, A.; Oliphint, P.A.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; De Hoff, P.; Morey, R.; Liu, J.; Roszik, J.; Clise-Dwyer, K.; et al. Mechanisms of nuclear content loading to exosomes. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaax8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, A.Z.; Ramasamy, T.S. Cancer stem cells as key drivers of tumour progression. J Biomed Sci 2018, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot, T.; Sirard, C.; Vormoor, J.; Murdoch, B.; Hoang, T.; Caceres-Cortes, J.; Minden, M.; Paterson, B.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Dick, J.E. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994, 367, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Cancer stem cells and their niche in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, K.E.; Wu, F.; Keysar, S.B.; Morton, J.J.; Miller, B.; Chimed, T.S.; Le, P.N.; Nieto, C.; Chowdhury, F.N.; Tyagi, A.; et al. Cancer Cell CD44 Mediates Macrophage/Monocyte-Driven Regulation of Head and Neck Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 4185–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eini, L.; Naseri, M.; Karimi-Busheri, F.; Bozorgmehr, M.; Ghods, R.; Madjd, Z. Preventive cancer stem cell-based vaccination modulates tumor development in syngeneic colon adenocarcinoma murine model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 4101–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Huang, Z.W.; Li, L.X.; Fu, J.J.; Xiao, B. Identification of CD200+ colorectal cancer stem cells and their gene expression profile. Oncol Rep 2016, 36, 2252–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Heidt, D.G.; Dalerba, P.; Burant, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Adsay, V.; Wicha, M.; Clarke, M.F.; Simeone, D.M. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcher, L.; Kistenmacher, A.K.; Suo, H.; Kitte, R.; Dluczek, S.; Strauß, A.; Blaudszun, A.R.; Yevsa, T.; Fricke, S.; Kossatz-Boehlert, U. Cancer Stem Cells-Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Mare, J.A.; Sterrenberg, J.N.; Sukhthankar, M.G.; Chiwakata, M.T.; Beukes, D.R.; Blatch, G.L.; Edkins, A.L. Assessment of potential anti-cancer stem cell activity of marine algal compounds using an in vitro mammosphere assay. Cancer Cell Int 2013, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.J.; Ma, S. Hallmarks of cancer stemness. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X.; Luo, M. Regulation and signaling pathways in cancer stem cells: implications for targeted therapy for cancer. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Shi, K.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, G.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, W. Effect of exosomal miRNA on cancer biology and clinical applications. Mol Cancer 2018, 17, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xing, T.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, J. Exosome-mediated miR-200b promotes colorectal cancer proliferation upon TGF-β1 exposure. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 106, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogure, T.; Lin, W.L.; Yan, I.K.; Braconi, C.; Patel, T. Intercellular nanovesicle-mediated microRNA transfer: a mechanism of environmental modulation of hepatocellular cancer cell growth. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; Zhu, A.; Gong, L. Exosomes of glioma cells deliver miR-148a to promote proliferation and metastasis of glioblastoma via targeting CADM1. Bull Cancer 2018, 105, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Ren, Z.J.; Tang, J.H.; Yu, Q. Exosomal MicroRNA MiR-1246 Promotes Cell Proliferation, Invasion and Drug Resistance by Targeting CCNG2 in Breast Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 44, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, M.; Cui, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zen, K.; Li, L. Shikonin Inhibits the Proliferation of Human Breast Cancer Cells by Reducing Tumor-Derived Exosomes. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabletz, T.; Kalluri, R.; Nieto, M.A.; Weinberg, R.A. EMT in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, K.; Li, C.; et al. Exosomes Derived from Hypoxic Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells Deliver miR-21 to Normoxic Cells to Elicit a Prometastatic Phenotype. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 1770–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, G.; Zhao, D.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Peng, Q.; Wang, H.; Fang, R.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; et al. CD103-positive CSC exosome promotes EMT of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: role of remote MiR-19b-3p. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sai, B.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, G.; Tang, J.; Xiang, J. Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs promote metastasis of lung cancer cells via STAT3-induced EMT. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lin, F.; Sun, W.; Zhu, W.; Fang, D.; Luo, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, L. Exosome-transmitted miRNA-335-5p promotes colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis by facilitating EMT via targeting RASA1. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020, 77, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.H.; Zhang, Z.J.; Shang, L.R.; Luo, Y.W.; Lin, Y.F.; Yuan, Y.; Zhuang, S.M. Hepatoma cell-secreted exosomal microRNA-103 increases vascular permeability and promotes metastasis by targeting junction proteins. Hepatology 2018, 68, 1459–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; You, B.; Shi, S.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yue, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Metastasis-associated miR-23a from nasopharyngeal carcinoma-derived exosomes mediates angiogenesis by repressing a novel target gene TSGA10. Oncogene 2018, 37, 2873–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, H.; Umezu, T.; Ohyashiki, K.; Hirano, T.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Exosomes derived from hypoxic leukemia cells enhance tube formation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 34343–34351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Seubert, B.; Stahl, E.; Dietz, H.; Reuning, U.; Moreno-Leon, L.; Ilie, M.; Hofman, P.; Nagase, H.; Mari, B.; et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 induces a pro-tumourigenic increase of miR-210 in lung adenocarcinoma cells and their exosomes. Oncogene 2015, 34, 3640–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, F.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.; Xu, W.; Lu, L.; et al. STAT3-regulated exosomal miR-21 promotes angiogenesis and is involved in neoplastic processes of transformed human bronchial epithelial cells. Cancer Lett 2016, 370, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.L.; Hung, J.Y.; Chang, W.A.; Lin, Y.S.; Pan, Y.C.; Tsai, P.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Kuo, P.L. Hypoxic lung cancer-secreted exosomal miR-23a increased angiogenesis and vascular permeability by targeting prolyl hydroxylase and tight junction protein ZO-1. Oncogene 2017, 36, 4929–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi-Dehghi, S.; Babashah, S.; Sadeghizadeh, M. microRNA-141-3p-containing small extracellular vesicles derived from epithelial ovarian cancer cells promote endothelial cell angiogenesis through activating the JAK/STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways. J Cell Commun Signal 2020, 14, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, K.; Babashah, S.; Sadeghizadeh, M.; Mowla, S.J.; Mossahebi-Mohammadi, M.; Ataei, F.; Dana, N.; Javan, M. MicroRNA-100 shuttled by mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes suppresses in vitro angiogenesis through modulating the mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling axis in breast cancer cells. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2017, 40, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, Q.H.; Wang, F.; Tan, J.J.; Deng, Y.Q.; Peng, X.H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, X.; Li, X.P. Exosomal miR-9 inhibits angiogenesis by targeting MDK and regulating PDK/AKT pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018, 37, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Ali, D.J.; Tian, T.; Xu, H.; Si, K.; Sun, B.; Chen, B.; Xiao, Z. Engineered exosomes for targeted co-delivery of miR-21 inhibitor and chemotherapeutics to reverse drug resistance in colon cancer. J Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Lai, X.; Yu, S.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Yao, L.; Zhang, J. Exosomal miR-221/222 enhances tamoxifen resistance in recipient ER-positive breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014, 147, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, T.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Deng, T.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; Bai, M.; Fan, Q.; et al. Exosomal miR-208b related with oxaliplatin resistance promotes Treg expansion in colorectal cancer. Mol Ther 2021, 29, 2723–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, R.; Van Roosbroeck, K. miR-155 in cancer drug resistance and as target for miRNA-based therapeutics. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2018, 37, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, A.A.; Gondaliya, P.; Mali, M.; Pawar, A.; Bhat, P.; Khairnar, A.; Arya, N.; Kalia, K. MiR-155 Inhibitor-Laden Exosomes Reverse Resistance to Cisplatin in a 3D Tumor Spheroid and Xenograft Model of Oral Cancer. Mol Pharm 2021, 18, 3010–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Yan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Shi, J.; Lu, E.; Chen, W.; et al. Exosomal miR-196a derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts confers cisplatin resistance in head and neck cancer through targeting CDKN1B and ING5. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Demirkhanyan, L.; Gondi, C.S. The Multifaceted Role of miR-21 in Pancreatic Cancers. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisan, E.D.; Rencuzogullari, O.; Cieza-Borrella, C.; Miralles Arenas, F.; Dwek, M.; Lange, S.; Uysal-Onganer, P. MiR-21 Is Required for the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Su, F.; Yao, H.; Song, E. Up-regulation of miR-21 mediates resistance to trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 19127–19137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nail, H.M.; Chiu, C.C.; Leung, C.H.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Wang, H.D. Exosomal miRNA-mediated intercellular communications and immunomodulatory effects in tumor microenvironments. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Li, F.; Jin, S.; Ho, P.C.; Liu, P.S.; Xie, X. Functional polarization of tumor-associated macrophages dictated by metabolic reprogramming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2023, 42, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, X.; Wu, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. Epithelial ovarian cancer-secreted exosomal miR-222-3p induces polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 43076–43087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, G.; Zhang, K.; Cao, J.; Huang, C.; Jiang, T.; Liu, B.; Su, L.; Qiu, Z. Hypoxic Tumor-Derived Exosomal miR-301a Mediates M2 Macrophage Polarization via PTEN/PI3Kγ to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res 2018, 78, 4586–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwe, P.M.; Amiel, E. The role of nitric oxide in metabolic regulation of Dendritic cell immune function. Cancer Lett 2018, 412, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Paone, A.; Calore, F.; Galli, R.; Gaudio, E.; Santhanam, R.; Lovat, F.; Fadda, P.; Mao, C.; Nuovo, G.J.; et al. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, E2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Zhou, L.; Shen, T.; Cao, L. IFN-γ induces the upregulation of RFXAP via inhibition of miR-212-3p in pancreatic cancer cells: A novel mechanism for IFN-γ response. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, 3760–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Yu, S.C.; Ping, Y.F.; Yang, J.; Xu, S.L.; Ye, X.Z.; Xu, C.; et al. Metastatic consequences of immune escape from NK cell cytotoxicity by human breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 5746–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.B.; Li, Z.L.; Luo, D.H.; Huang, B.J.; Chen, Y.S.; Zhang, X.S.; Cui, J.; Zeng, Y.X.; Li, J. Tumor-derived exosomes promote tumor progression and T-cell dysfunction through the regulation of enriched exosomal microRNAs in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5439–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, I.S.; Coomes, S.M.; Pelly, V.S.; Czieso, S.; Papayannopoulos, V.; Tolmachova, T.; Seabra, M.C.; Wilson, M.S. MicroRNA-Containing T-Regulatory-Cell-Derived Exosomes Suppress Pathogenic T Helper 1 Cells. Immunity 2014, 41, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.B.; Zhang, H.; Cai, T.T.; Liu, Y.N.; Ni, J.J.; He, J.; Peng, J.Y.; Chen, Q.Y.; Mo, H.Y.; Jun, C.; et al. Exosomal miR-24-3p impedes T-cell function by targeting FGF11 and serves as a potential prognostic biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Pathol 2016, 240, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.F.; Zhang, H.W.; Hu, S.; Lu, M.H.; Liang, S.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, E.D.; et al. A novel miR-155/miR-143 cascade controls glycolysis by regulating hexokinase 2 in breast cancer cells. Embo j 2012, 31, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Gao, J.; Huang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Wei, Z. Downregulating microRNA-144 mediates a metabolic shift in lung cancer cells by regulating GLUT1 expression. Oncol Lett 2016, 11, 3772–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; Wang, D.; Xu, H.; Mei, F.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, B. miR-21 promotes non-small cell lung cancer cells growth by regulating fatty acid metabolism. Cancer Cell Int 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.Y.; Yeh, K.Y.; Liu, B.F.; Chang, T.M.; Chang, C.H.; Liao, Y.F.; Liu, Y.W.; Her, G.M. MicroRNA-21 Plays Multiple Oncometabolic Roles in Colitis-Associated Carcinoma and Colorectal Cancer via the PI3K/AKT, STAT3, and PDCD4/TNF-α Signaling Pathways in Zebrafish. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Pan, P.; Shang, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, C. Down-Regulating the Expression of miRNA-21 Inhibits the Glucose Metabolism of A549/DDP Cells and Promotes Cell Death Through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/HIF-1α Pathway. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 653596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewski, J.; Nowicki, M.O.; Bronisz, A.; Nuovo, G.; Palatini, J.; De Lay, M.; Van Brocklyn, J.; Ostrowski, M.C.; Chiocca, E.A.; Lawler, S.E. MicroRNA-451 regulates LKB1/AMPK signaling and allows adaptation to metabolic stress in glioma cells. Mol Cell 2010, 37, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, D.; Tu, Y.; Yu, Y. MicroRNA-mediated autophagy and drug resistance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Discov Oncol 2024, 15, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Huo, X.; Bi, X.; Cao, D.; Yang, J.; Shen, K.; Peng, P. Exosome transmit the ability of migration and invasion in heterogeneous ovarian cancer cells by regulating autophagy via targeting hsa-miR-328. Gynecol Oncol 2025, 194, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z. miR-224-5p Carried by Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Regulates Autophagy in Breast Cancer Cells via HOXA5. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 679185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yuwen, D.; Chen, J.; Zheng, B.; Gao, J.; Fan, M.; Xue, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Shu, Y.; et al. Exosomal Transfer Of Cisplatin-Induced miR-425-3p Confers Cisplatin Resistance In NSCLC Through Activating Autophagy. Int J Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 8121–8132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Mao, J.H.; Wang, B.Y.; Wang, L.X.; Wen, H.Y.; Xu, L.J.; Fu, J.X.; Yang, H. Exosomal miR-1910-3p promotes proliferation, metastasis, and autophagy of breast cancer cells by targeting MTMR3 and activating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Cancer Lett 2020, 489, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, K.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yan, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; He, S.; et al. Osteoblast-derived exosomal miR-140-3p targets ACER2 and increases the progression of prostate cancer via the AKT/mTOR pathway-mediated inhibition of autophagy. Faseb j 2024, 38, e70206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clara, J.A.; Monge, C.; Yang, Y.; Takebe, N. Targeting signalling pathways and the immune microenvironment of cancer stem cells - a clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020, 17, 204–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Ma, L.; Zhu, J. miR-483-5p promotes growth, invasion and self-renewal of gastric cancer stem cells by Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Med Rep 2016, 14, 3421–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Zou, C.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, L.; Lei, Y.; Tang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; et al. HIF-1ɑ-regulated miR-1275 maintains stem cell-like phenotypes and promotes the progression of LUAD by simultaneously activating Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2553–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Shi, Z.; Cao, L.; Liu, J.; Pan, T.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, J. Chemotherapy-elicited exosomal miR-378a-3p and miR-378d promote breast cancer stemness and chemoresistance via the activation of EZH2/STAT3 signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021, 40, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, M.; Fu, L.; Jin, Y. Exosomal release of microRNA-454 by breast cancer cells sustains biological properties of cancer stem cells via the PRRT2/Wnt axis in ovarian cancer. Life Sci 2020, 257, 118024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xin, X.; Li, X.; Geng, J.; Sun, Y. Exosomes secreted by M2 macrophages promote cancer stemness of hepatocellular carcinoma via the miR-27a-3p/TXNIP pathways. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 101, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Dong, C.; Ruan, X.; Yan, W.; Cao, M.; Pizzo, D.; Wu, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Ren, X.; et al. Chemotherapy-Induced Extracellular Vesicle miRNAs Promote Breast Cancer Stemness by Targeting ONECUT2. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 3608–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Banerjee, A.; Cui, T.; Han, C.; Cai, S.; Liu, L.; Wu, D.; Cui, R.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Inhibition of miR-328-3p Impairs Cancer Stem Cell Function and Prevents Metastasis in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 2314–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashouri, L.; Yousefi, H.; Aref, A.R.; Ahadi, A.M.; Molaei, F.; Alahari, S.K. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.; Zhang, J.; Yarden, Y.; Fu, L. The key roles of cancer stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Teng, Y. Harnessing cancer stem cell-derived exosomes to improve cancer therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2023, 42, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Ge, X.; Shi, Z.; Yu, C.; Lu, C.; Wei, Y.; Zeng, A.; Wang, X.; Yan, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from hypoxic glioma stem-like cells confer temozolomide resistance on glioblastoma by delivering miR-30b-3p. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1763–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Shen, L.; Li, M.; Sun, J.; Hao, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Ge, S.; Zhang, D.; Guo, H.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Derived miR-146a-5p Generates a Niche That Promotes Bladder Cancer Stemness and Chemoresistance. Cancer Res 2023, 83, 1611–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhao, N.; Cui, J.; Wu, H.; Xiong, J.; Peng, T. Exosomes derived from cancer stem cells of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells enhance drug resistance by delivering miR-210. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2020, 43, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukohyama, J.; Isobe, T.; Hu, Q.; Hayashi, T.; Watanabe, T.; Maeda, M.; Yanagi, H.; Qian, X.; Yamashita, K.; Minami, H.; et al. miR-221 Targets QKI to Enhance the Tumorigenic Capacity of Human Colorectal Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 5151–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Lima, N.D.S.; Sarian, L.O.; Matheu, A.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Derchain, S.F.M. Exosome-mediated breast cancer chemoresistance via miR-155 transfer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T.H.; Huang, W.C.; Tung, S.L.; Lin, S.C.; Chen, P.M.; Cho, C.Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Yen, T.C.; Lo, G.H.; Chuang, S.E.; et al. MicroRNA-485-5p targets keratin 17 to regulate oral cancer stemness and chemoresistance via the integrin/FAK/Src/ERK/β-catenin pathway. J Biomed Sci 2022, 29, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preethi, K.A.; Selvakumar, S.C.; Ross, K.; Jayaraman, S.; Tusubira, D.; Sekar, D. Liquid biopsy: Exosomal microRNAs as novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in cancer. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Yu, L.; Lin, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, D.; Pan, X.; Huang, Y. Combination of Serum miRNAs with Serum Exosomal miRNAs in Early Diagnosis for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Manag Res 2020, 12, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Dong, Y.; Wang, K.J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shen, H.F. Plasma exosomal miR-125a-5p and miR-141-5p as non-invasive biomarkers for prostate cancer. Neoplasma 2020, 67, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Liao, C.; Wang, X.; He, K. Plasma-Derived Exosomal microRNA-130a Serves as a Noninvasive Biomarker for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Oncol 2021, 2021, 5547911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, P.; Leng, K.; Xu, Y.; Mei, L.; Han, P.; Zhang, B.; Yao, K.; Li, C.; et al. Colorectal cancer-derived exosomal miR-106b-3p promotes metastasis by down-regulating DLC-1 expression. Clin Sci (Lond) 2020, 134, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.M.; Cha, E.J.; Yun, S.J.; Kim, W.J. Role of Exosomal miRNA in Bladder Cancer: A Promising Liquid Biopsy Biomarker. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, G.; Song, X.; Yang, F.; Wu, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y. Exosomes derived from miR-122-modified adipose tissue-derived MSCs increase chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol 2015, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Baghaei, K.; Amani, D.; Piccin, A.; Hashemi, S.M.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Zali, M.R. Exosome-mediated delivery of functionally active miRNA-375-3p mimic regulate epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) of colon cancer cells. Life Sci 2021, 269, 119035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, B.; Ye, J.; Cao, S.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sang, J.; Yao, Y.; Guan, W.; et al. Exosomal miRNA-139 in cancer-associated fibroblasts inhibits gastric cancer progression by repressing MMP11 expression. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Z.; Geng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Z. Exosomal miRNA-34 from cancer-associated fibroblasts inhibits growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 8549–8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Mo, C.; Guo, S.; Zhuang, J.; Huang, B.; Mao, X. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived microRNA-205-containing exosomes impede the progression of prostate cancer through suppression of RHPN2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019, 38, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, F.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, W. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-486-5p inhibit glycolysis and cell stemness in colorectal cancer by targeting NEK2. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, R.; Xiong, J.; Yao, Y.L.; Wu, J.H.; Li, G.X. Macrophage-secreted Exosomes Delivering miRNA-21 Inhibitor can Regulate BGC-823 Cell Proliferation. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015, 16, 4203–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fang, M.; Qian, D. Targeting exosomes enveloped EBV-miR-BART1-5p-antagomiRs for NPC therapy through both anti-vasculogenic mimicry and anti-angiogenesis. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 12608–12621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, K.; Yan, I.K.; Lewis-Tuffin, L.; Patel, T. Targeting Liver Cancer Stem Cells Using Engineered Biological Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Cancer. Hepatol Commun 2020, 4, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossa, A.; Fonsato, V.; Grange, C.; Tritta, S.; Tapparo, M.; Calvetti, R.; Cedrino, M.; Fallo, S.; Gontero, P.; Camussi, G.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from human liver stem cells inhibit renal cancer stem cell-derived tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer 2020, 147, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Yang, H.; Duan, D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, J. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal miR-145-5p reduced non-small cell lung cancer cell progression by targeting SOX9. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.M.; Hossain, A.; Gumin, J.; Momin, E.N.; Shimizu, Y.; Ledbetter, D.; Shahar, T.; Yamashita, S.; Parker Kerrigan, B.; Fueyo, J.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells as natural biofactories for exosomes carrying miR-124a in the treatment of gliomas. Neuro Oncol 2018, 20, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, Z.; Oskuee, R.K.; Forouzandeh-Moghadam, M.; Jaafari, M.R. Delivery of LNA-antimiR-142-3p by Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes to Breast Cancer Stem Cells Reduces Tumorigenicity. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2020, 16, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exosomal miRNA | Source | Function | Mechanism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-200b | Colorectal cancer | Promotes tumor growth | Specifically binds to the 3′-UTR of tumor suppressor p27, reducing its expression | [34] | |

| miR-584 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Promotes tumor growth | Targets TAK1 and related signaling pathways, leading to downregulation of TAK1 expression | [35] | |

| miR-148a | Glioblastoma | Promotes tumor growth | Targets CADM1 to relieve its inhibitory effect on the STAT3 pathway | [36] | |

| miR-1246 | Breast cancer | Promotes tumor growth | Specifically downregulates cyclin G2 (CCNG2), disrupting the cell cycle regulatory network | [37] | |

| miR-128 | Breast cancer | Promotes tumor metastasis | Regulates the balance of Bcl-2 family proteins (e.g., pro-apoptotic factor Bax), inhibiting initiation of apoptosis | [38] | |

| miR-21 | Oral squamous cell carcinoma | Promotes tumor metastasis | Regulates EMT core transcription factor Snail; upregulates vimentin and downregulates E-cadherin expression | [40] | |

| miR-19b-3p | Renal cell carcinoma | Promotes tumor metastasis | Reduces PTEN expression, inducing EMT | [41] | |

| miR-193a-3p, miR-210-3p, miR-5100 | Mesenchymal stem cells | Promotes tumor metastasis | Activates STAT3 signaling and induces EMT, promoting lung cancer metastasis | [42] | |

| miR-335-5p | Colorectal cancer | Promotes tumor metastasis | Targets RASA1 to promote EMT | [43] | |

| miR-103 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Targets multiple endothelial junction proteins (VE-cadherin, p120-catenin, ZO-1), enhancing vascular permeability | [45] | |

| miR-23a | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation; targets and inhibits TSGA10 | [46] | |

| miR-210 | Leukemia | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Targets and inhibits Ephrin-A3, activating VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling | [47] | |

| miR-21 | Lung cancer | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Activates STAT3 signaling and upregulates VEGF expression | [49] | |

| miR-23a | Lung cancer | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Inhibits PHD and tight junction protein ZO-1, increasing vascular permeability | [50] | |

| miR-141-3p | Ovarian cancer | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Activates JAK-STAT3 signaling in endothelial cells | [51] | |

| miR-9 | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Promotes tumor angiogenesis | Regulates PDK/Akt signaling to inhibit NPC cell migration | [53] | |

| miR-21 | Colorectal cancer | Promotes chemoresistance | Downregulates PTEN and hMSH2, inducing resistance to 5-fluorouracil | [54] | |

| miR-221/222 | Breast cancer | Promotes chemoresistance | Inhibits p27 and ERα expression, enhancing tamoxifen resistance | [55] | |

| miR-208b | Colorectal cancer | Promotes chemoresistance | Targets PDCD4 to promote Treg activation, increasing oxaliplatin resistance | [56] | |

| miR-196a | Head and neck cancer | Promotes chemoresistance | Targets CDKN1B and ING5, promoting proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and enhancing cisplatin resistance | [59] | |

| miR-222-3p | Ovarian cancer | Promotes immune suppression | Targets SOCS3 and activates STAT3 signaling, inducing M2 macrophage polarization | [65] | |

| miR-301a-3p | Pancreatic cancer | Promotes immune suppression | Inhibits PTEN and activates PI3Kγ signaling, driving M2 macrophage polarization | [66] | |

| miR-21,miR-29 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Promotes immune suppression | Activates TLR-mediated NF-κB signaling, inducing a pro-tumor inflammatory microenvironment | [68] | |

| miR-212-3p | Pancreatic cancer | Promotes immune suppression | Inhibits RFXAP expression, reducing MHC II levels and inducing immune tolerance | [69] | |

| miR-20a | Breast cancer | Promotes immune suppression | Downregulates NKG2D ligands (MICA and MICB), reducing NK cell recognition and killing ability | [70] | |

| miR-24-3p | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Promotes immune suppression | Targets PTEN, activates PI3K/Akt pathway, and upregulates PD-L1, inhibiting T-cell function | [73] | |

| miR-144 | Lung cancer | Promotes tumor metabolism | Upregulates GLUT1, increasing glucose uptake and lactate production | [75] | |

| miR-21 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Promotes tumor metabolism | Increases intracellular lipid content and upregulates key lipid metabolism enzymes (FASN, ACC1, FABP5) | [76] | |

| miR-328-3p | Ovarian cancer | Promotes autophagy | Targets Raf1 and inhibits mTOR pathway activation | [81] | |

| miR-425 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Promotes autophagy | Targets AKT1 to activate autophagy | [83] | |

| miR-1910-3p | Breast cancer | Promotes autophagy | Targets MTMR3 and activates NF-κB signaling | [84] | |

| miR-378a-3p | Breast cancer | Maintains CSC stemness | Activates Wnt/Notch pathway | [89] | |

| miR-454 | Breast cancer | Maintains CSC stemness | Activates PRRT2/Wnt axis | [90] | |

| miR-328-3p | Ovarian CSCs | Maintains CSC stemness | Targets and inhibits DNA damage-binding protein 2 | [93] | |

| miR-30b-3p | Glioma CSCs | Mediates CSC therapy resistance | Targets RHOB, reducing apoptosis and enhancing TMZ resistance | [97] | |

| miR-210 | Pancreatic CSCs | Mediates CSC therapy resistance | Upregulates MDR1, YB-1, BCRP, and activates mTOR signaling | [99] | |

| miR-155 | Breast CSCs | Mediates CSC therapy resistance | Regulates C/EBP-β and suppresses TGF-β, C/EBP-β, FOXO3a, inducing EMT and chemoresistance | [101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).