Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Irradiation time ti < 100 ms;

- Average dose rate > 100 Gy/s;

- In-peak dose rate p > 106 Gy/s;

- Pulse repetition frequency PRF > 100 Hz;

- Dose per pulse > 1 Gy.

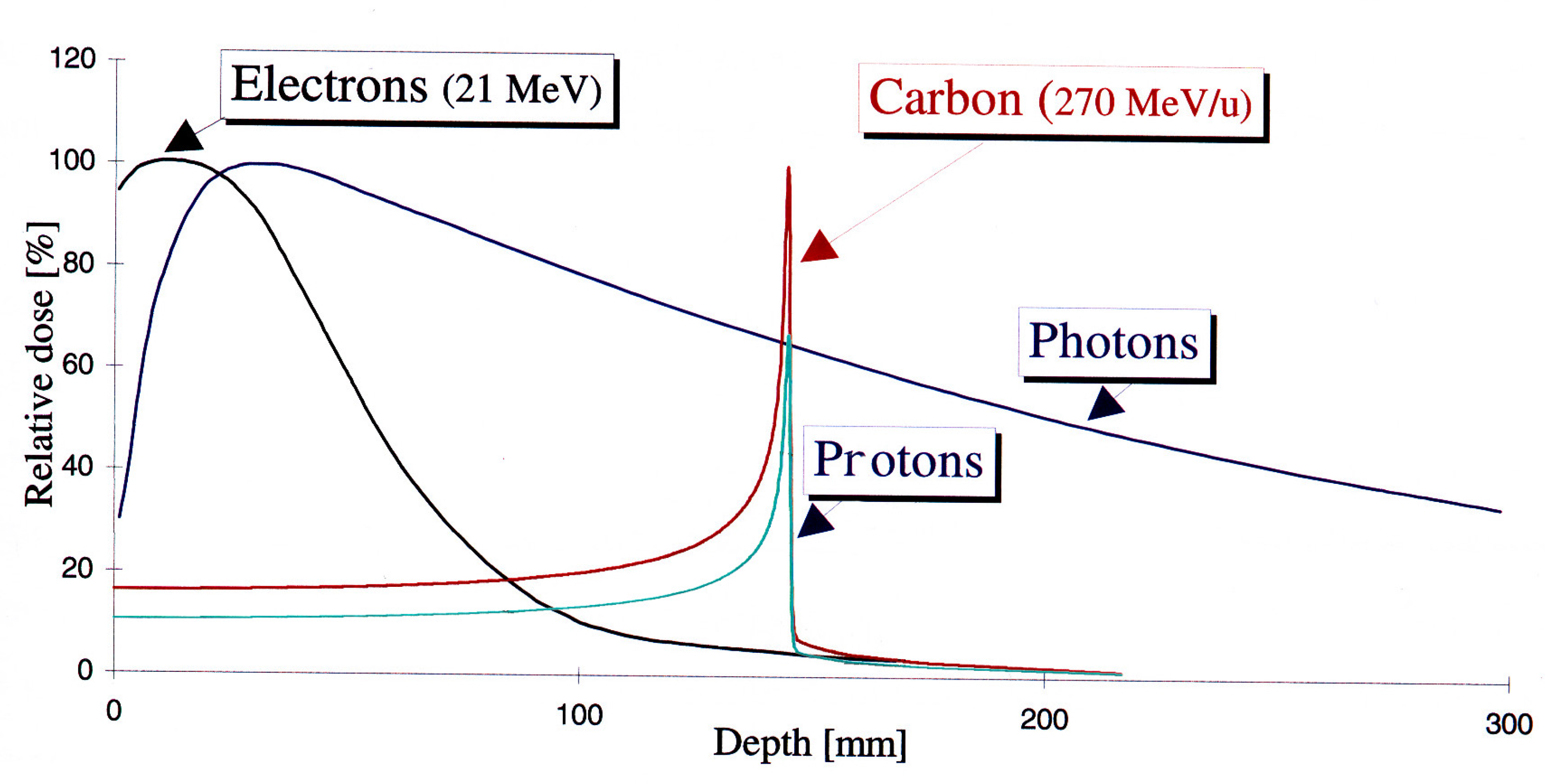

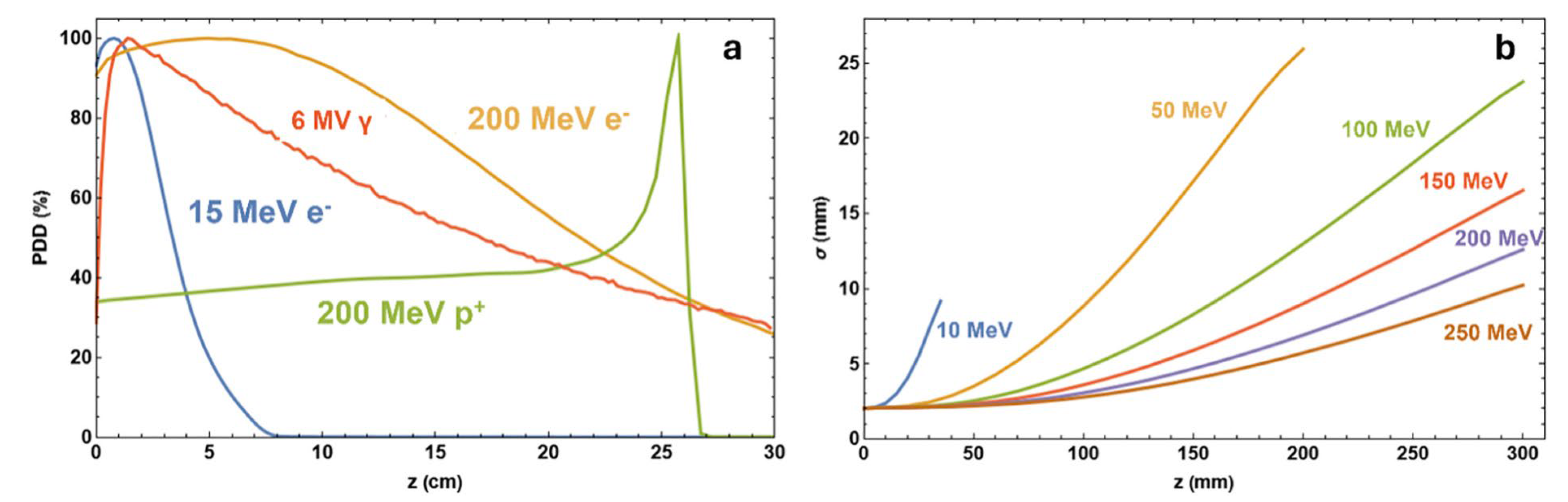

2. VHEE Beam Energy Evolution to Treatment

3. Current VHEE Facilities

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

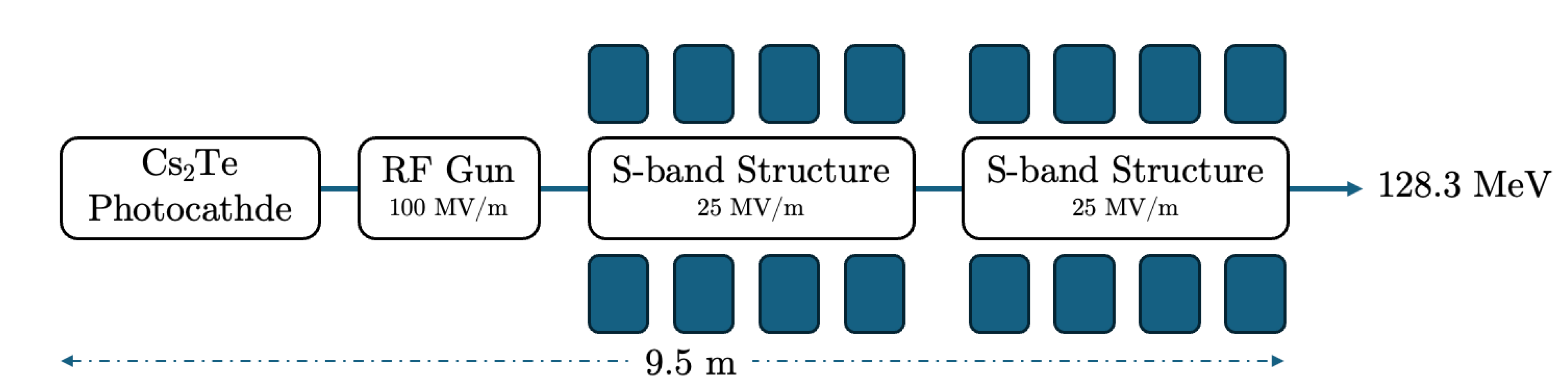

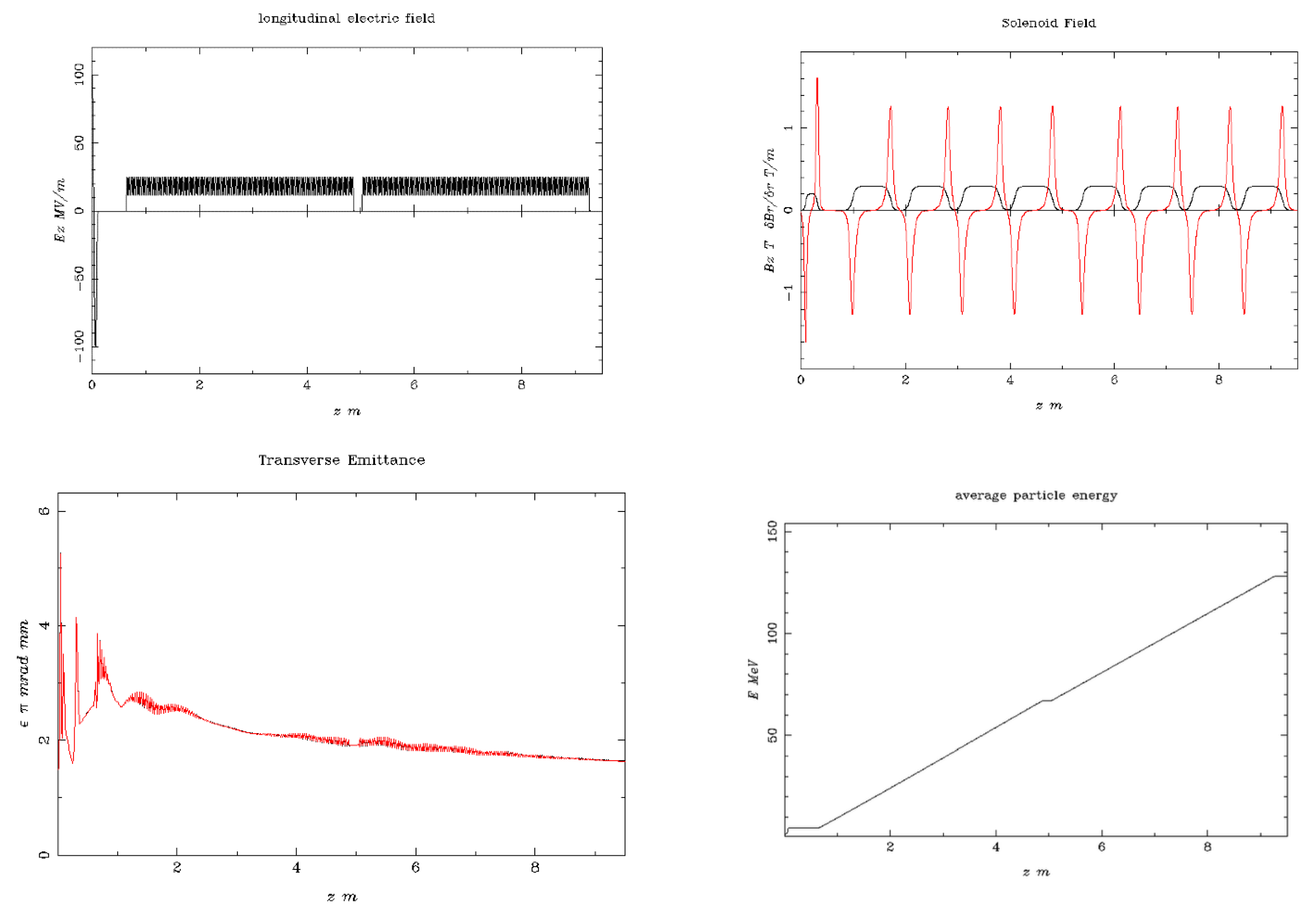

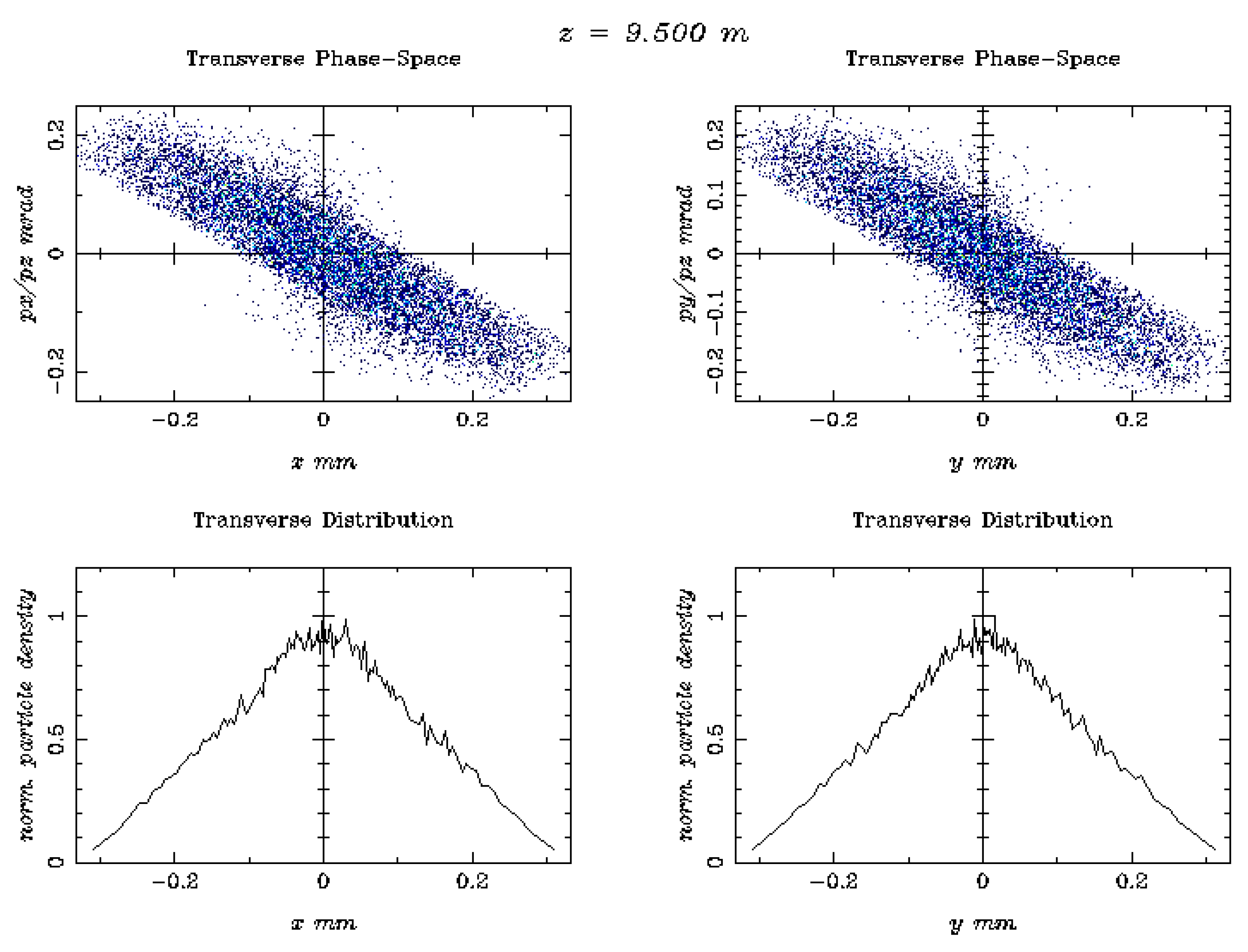

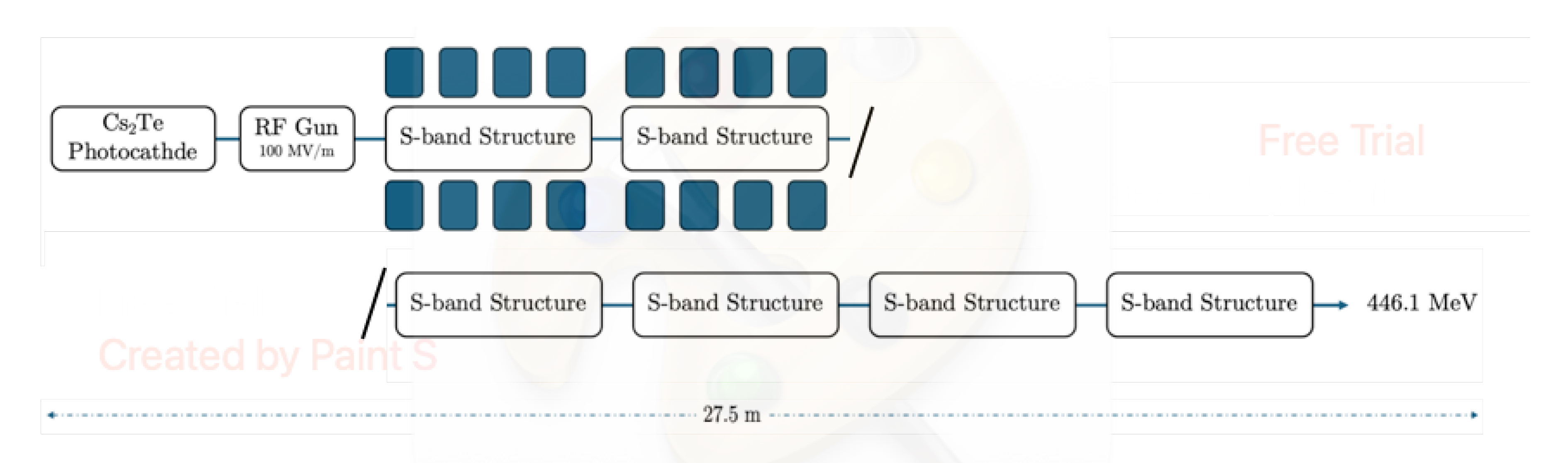

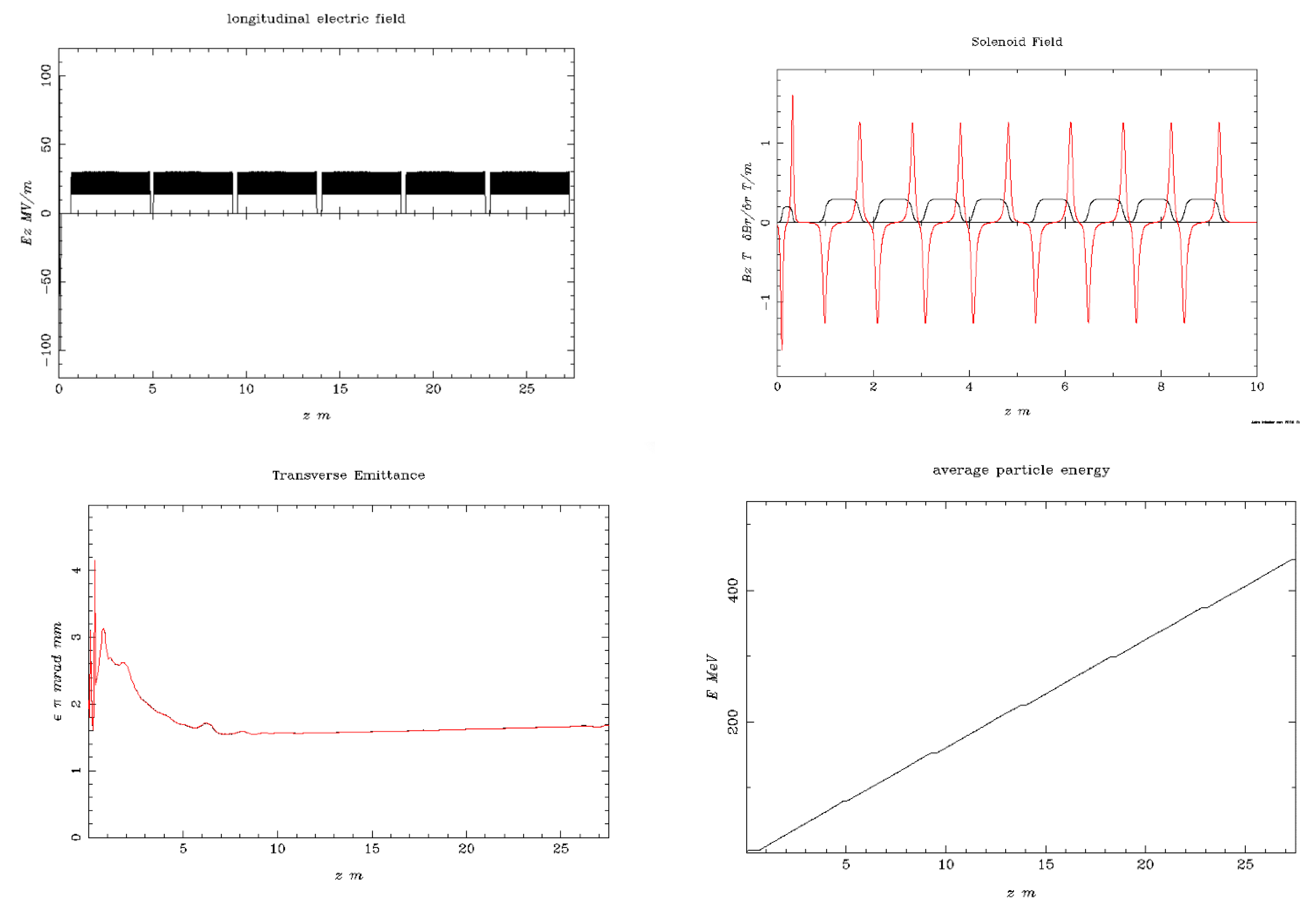

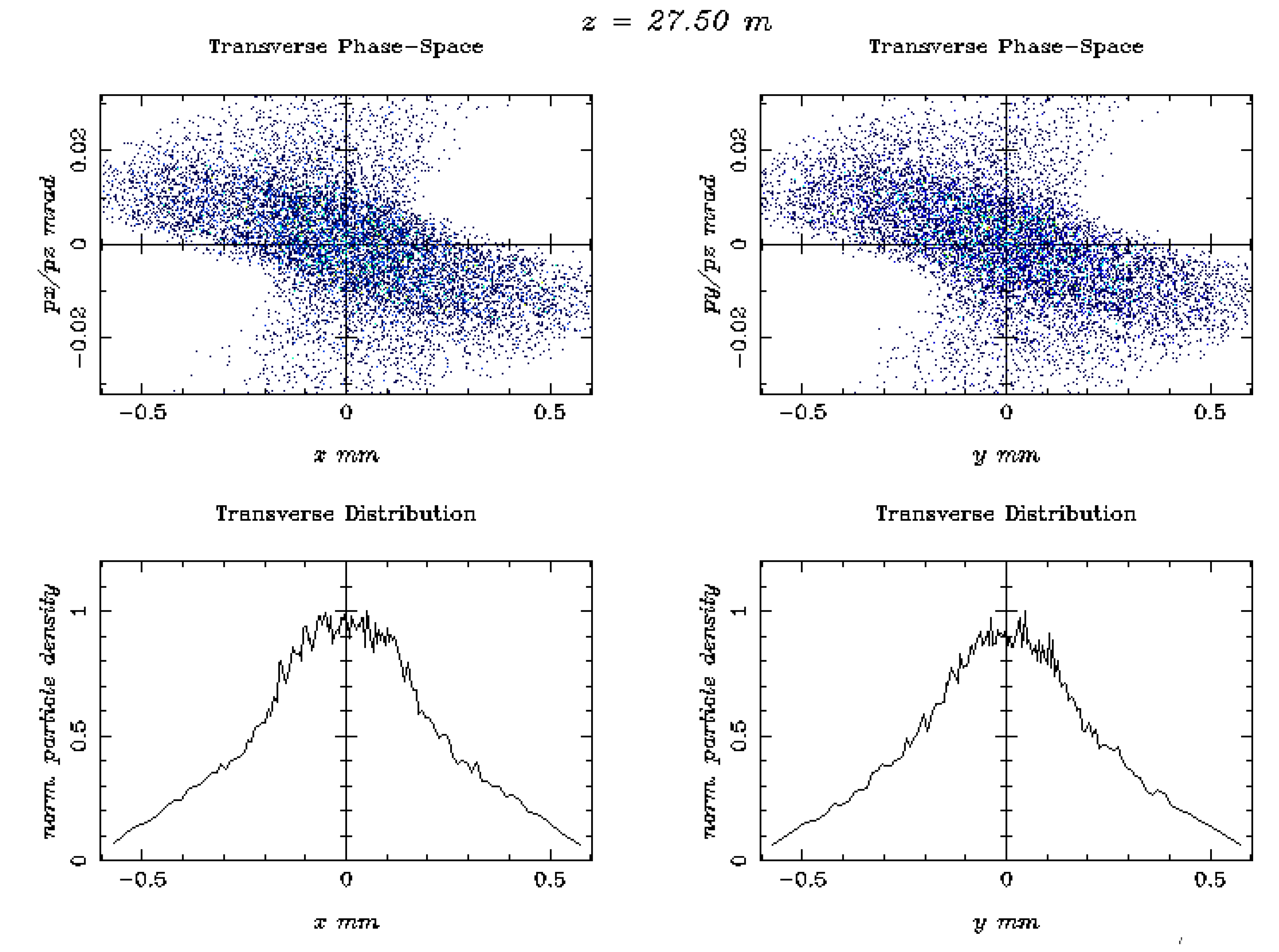

4. FLASH Electron Beam Injector Simulation Studies

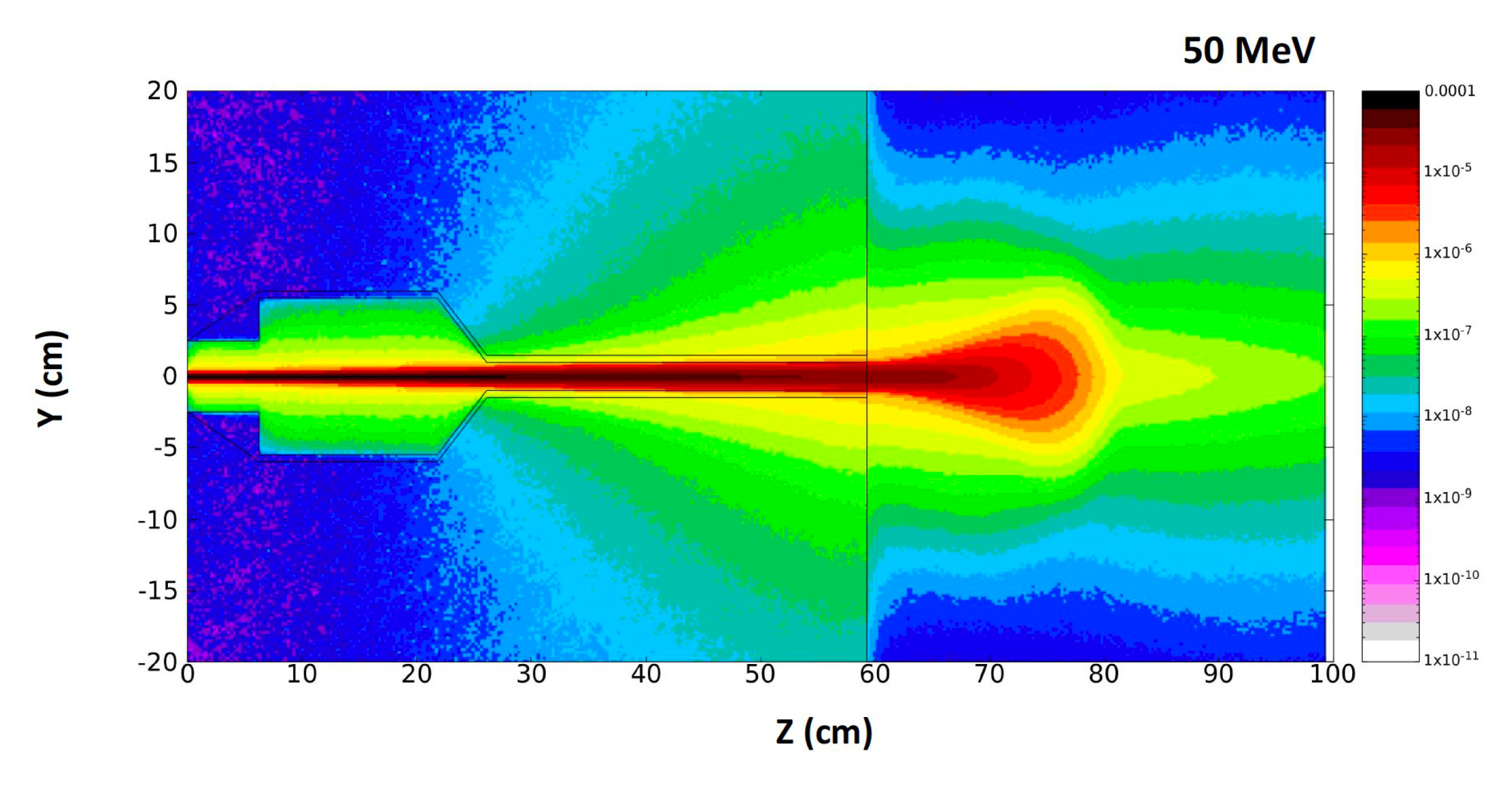

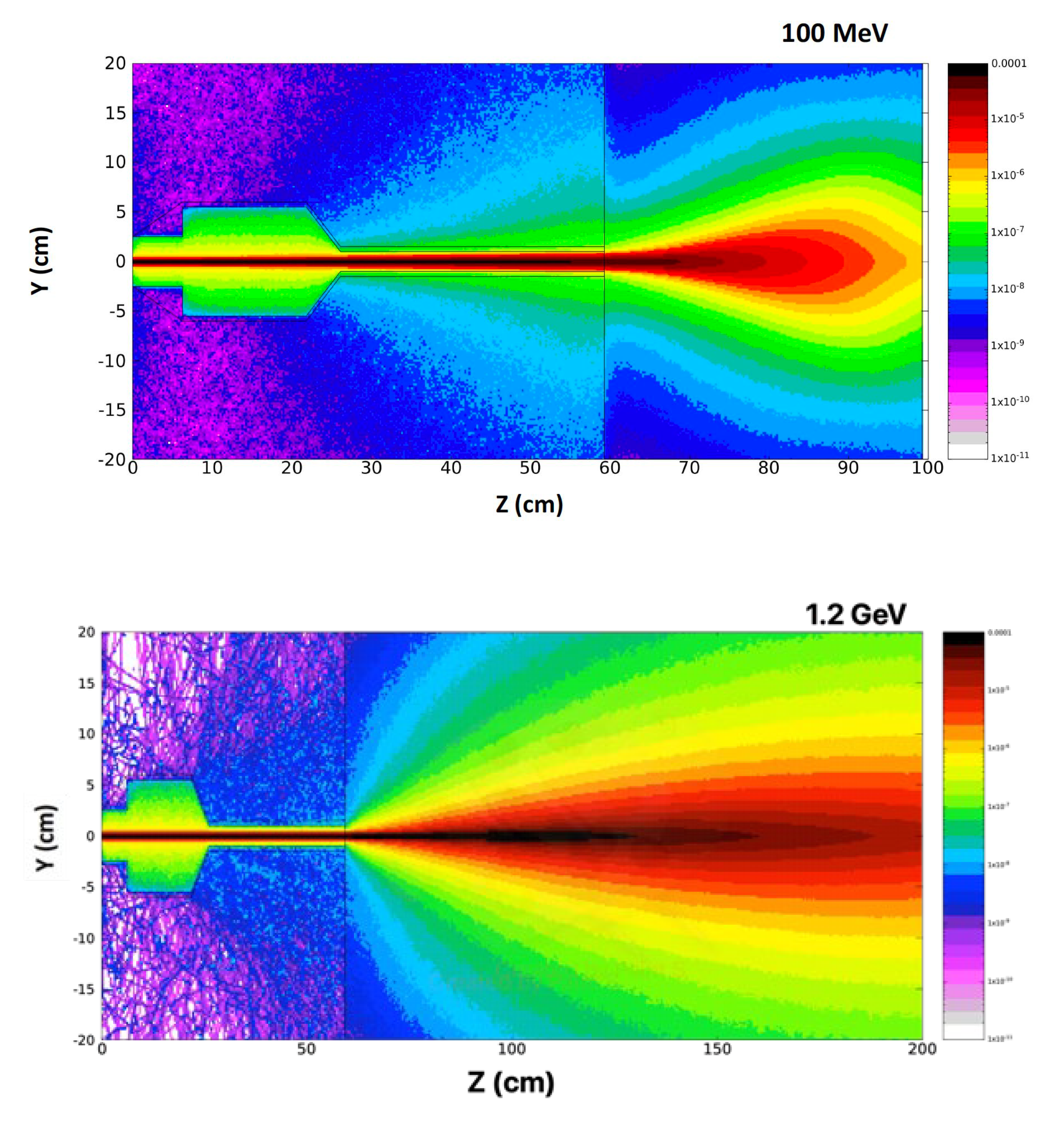

5. Beam Dose Distribution Simulation Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; Gondhowiardjo, S.S.; Rosa, A.A.; Lievens, Y.; El-Haj, N.; Rubio, J.A.P.; Ben Prajogi, G.; Helgadottir, H.; Zubizarreta, E.; Meghzifene, A.; et al. “Global Radiotherapy: Current Status and Future Directions—White Paper”. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 827–842. [CrossRef]

- Gazis, N.; Bignami, A.; Trachanas, E.; Moniaki, M.; Gazis, E.; Bandekas and D.; Vordos, N., “Simulation Dosimetry Studies for FLASH Radio Therapy with Ultra-High-Dose Rate (UHDR) Beam”, Quantum Beam Sci. 2024, 8, 13. [CrossRef]

- Gianfaldoni, S.; Gianfaldoni, R.; Wollina, U.; Lotti, J.; Tchernev, G. and Lotti, T.; “An Overview on Radiotherapy: From Its History to Its Current Applications in Dermatology”. Open Access Mac. Journal of Medical Sciences, 2017, 5(4), p.521. [CrossRef]

- Birindelli; G., “Entropic model for dose calculation in external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy”, 2011, PhD thesis, U. de Bordeaux. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03214566.

- Tsujii H. “Overview of Carbon-ion Radiotherapy”, IOP Conf. Series: Journal of Physics: Conf. Series 777 (2017) 012032. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Liu, K.; Hou, Y.; Cheng, J.; and Zhang, J.; (2017). The evolution of proton beam therapy: Current and future status (Review). Molecular and Clinical Oncology, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Panaino C.M.V.; Piccinini S.; Andreassi M.G.; Bandini G.; Borghini A.; Borgia M.; Di Naro A.; Labate L.U.; Maggiulli E.; Portaluri M.G.A.; and Gizzi L.A.; “Very High-Energy Electron therapy toward clinical implementation”, Cancers 2025, 17, 18. [CrossRef]

- Gagnebin, S.; Twerenbold, D.; Pedroni, E.; Meer, D.; Zenklusen, S.; and Bula, C.; “Experimental determination of the absorbed dose to water in a scanned proton beam using a water calorimeter and an ionization chamber”. NIM B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, 268(5) 2010, pp.524–528. [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, J.; Sozzi, W.J.; Jorge, P.G.; Gaide, O.; Bailat, C.; Duclos, F.; Patin, D.; Ozsahin, M.; Bochud, F.; Germond, J.F.; et al., “Clinical translation of FLASH radio-therapy: Why and how?” Radiother. Oncol., vol. 139, pp. 11–17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pratx, G.; Kapp, D.S.; “A computational model of radiolytic oxygen depletion during FLASH irradiation and its effect on the oxygen enhancement ratio,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 64, p. 185005., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Favaudon, V.; Caplier, L.; Monceau, V.; Pouzoulet, F.; Sayarath, M.; Fouillade, C.; Poupon, M.F.; Brito, I.; Hupe, P.; Bourhis, J.; et al, “Ultrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the differential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice,” Sci. Transl. Med., vol. 12, no. 6, p. 1671, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Naceur A.; Bienvenue C.; Romano P.; Chilian C.; and Carrier J.-F.; “Extending deterministic transport capabilities for very-high and ultra-high energy electron beams”, Scient. Rep. 14: 2796 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gamba D.; Corsini R.; Curt S.: Doebert S.; Frabolini W.; Mcmonagle G.; Skowronski P.K.; Tecket F.; Zeeshan S.; Adli E.; Lindstrom C.A.; Ross A.; Wroe L.M.; “The CLEAR user facility at CERN”, NIM A 909 (2018) 480-483. [CrossRef]

- Marchand D.; “A new platform for research and applications with electrons: the PRAE project”, EPJ web of Conferences 138, 01012 (2017), ISHEPP XXIII International Baldin Seminar on High Energy. [CrossRef]

- Delorme R.; Marchand D.; and Vallerand C.; “The PRAE Multidisciplinary Project”, Nucl. Phys News, 29, 2019 (1), 32-35. [CrossRef]

- Han Y.; Faus-Golfe A.; Vallerand C.; Bai B.; Duchesne P.; Prezado Y.; Delorme R.; Poortmans P.; Favaudon V.; Fouillade C.; Pouzoulet F.; Dosanjh M.; “Optics design and beam dynamics simulation for a a VHEE radiobiology beamline at PRAE accelerator”, 10th Int. Part. Acc. Conf. IPAC2019. [CrossRef]

- Angal-Kalinin D.a; Boogert S.; and Jones J.K.; “Potential of the CLARA test facility for VHEE rationteraly research”, Front. Phys. 12 (2024):1496850. [CrossRef]

- Ferrario M.; Alesini D.; Anania M.; Bacci A.; Bellaveglia M.; Bogdanov O.; Boni R.; Castellano M.; Chiadroni E.; Cianchi A.; et al., “SPARC_LAB present and future”, NIM B: 309 (2013) 183-188. [CrossRef]

- Small K.L.; Angal-Kalinin D.; Jones J.K.; and Jones R.J.; “VHEE facilities I Europe with the potential for FLASH dose irradiation; Conspectus and dose rate parameterisation”, NIM B 565 (2025) 165752. [CrossRef]

- Masilela T.A.M.; Delorme R.; and Prezado Y.; “Dosimetry and radioprotection evaluations of very-high energy electron beams”, Scient. Rep. 11: 20184 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Yuan, J.; Chen, L.; and Sheng, Z.; “Laser-driven very high energy electron/photon beam radiation therapy in conjunction with a robotic system”, Appl. Sci. 5, 1–20, (2015). [CrossRef]

- DesRosiers, C.; Moskvin, V.; Cao, M.; Joshi, C. J.; and Langer, M.; “Laser-plasma generated very high energy electrons in radiation therapy of the prostate”, Proc. SPIE 6881, 49–62, (2008). [CrossRef]

- Kokurewicz, K.; Welsh G.H.; Wiggins S.M.; Boyd M.; Sorensen A.; et al., “Laser-plasma generated very high energy electrons (VHEEs) in radiotherapy”, Proc. SPIE 10239, (2017) 61–69. [CrossRef]

- Poppinga, D.; Kranzer R.; Farabolini W.; Gilardi A.; Corsini R.; Wyrwoll V.; Looe H.K.; Delfs B.; Gabrisch L.; and Poppe L.; “VHEE beam dosimetry at CERN linear electron accelerator for research under ultra-high dose rate conditions”, Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 7, 015012 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kokurewicz, K.; Brunetti, E.; Welsh, G.H.; Wiggins, S.M.; Boyd, M.; Sorensen, A.; Chalmers, A.J.; Schettino, G.; Subiel, A.; DesRosiers, C.; et al. “Focused very high-energy electron beams as a novel radiotherapy modality for producing high-dose volumetric elements”,. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10837. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.; Eley, J.G.; Onyeuku, N.E.; Rice, S.R.; Wright, C.C.; McGovern, N.E.; Sank, M.; Zhu, M.; Vujaskovic, Z.; Simone, C.B.; et al. “Proton Therapy Delivery and Its Clinical Application in Select Solid Tumor Malignancies”, J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 144, e58372. [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, L.; Franciosini, G.; Palumbo, L.; Aggar, L.; Dutreix, M.; Faillace, L.; Favaudon, V.; Felici, G.; Galante, F.; Mostacci, A.; et al. «Characterization of Ultra-High-Dose Rate Electron Beams with Electron FLASH Linac”, Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 631. [CrossRef]

- Montay-Gruel, P.; Petersson, K.; Jaccard, M.; Boivin, G.; Germond, J.-F.; Petit, B.; Doenlen, R.; Favaudon, V.; Bochud, F.; Bailat, C.; et al., “Irradiation in a flash: Unique sparing of memory in mice after whole brain irradiation with dose rates above 100 Gy/s”, Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 124, 365–369. [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, C.; Moskvin, V.; Bielajew, A.F.; Papiez, L.; “150–250 MeV electron beams in radiation therapy”, Phys. Med. Biol. 2000, 45, 1781–1805. [CrossRef]

- Rongo M.G.; Cavallone M.; Patriarca A.; Leite A.M.; Loap P.; Favaudon V.; Crehange G.; and De Marzi L., “Back to the Future: Very High-Energy Electrons (VHEEs) and their potential applications in Radiation Therapy”, Cancers 2021, 13, 4942. [CrossRef]

- Hogstrom, K.R.; Almond, P.R.; “Review of electron beam therapy physics”, Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, R455–R489. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.; Fix, M.K.; Henzen, D.; Frei, D.; Frauchiger, D.; Loessl, K.; Stampanoni, M.F.M.; Manser, P.; “Electron beam collimation with a photon MLC for standard electron treatments”, Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 63, 025017. [CrossRef]

- Krempien, R.; Roeder, F.; “Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) in pancreatic cancer”. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 12, 8. [CrossRef]

- Vozenin, M.-C.; De Fornel, P.; Petersson, K.; Favaudon, V.; Jaccard, M.; Germond, J.-F.; Petit, B.; Burki, M.; Ferrand, G.; Patin, D.; et al. “The Advantage of FLASH Radiotherapy Confirmed in Mini-pig and Cat-cancer Patients”, Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 25,35–42. [CrossRef]

- Vozenin, M.-C.; Hendry, J.; Limoli, C. “Biological Benefits of Ultra-high Dose Rate FLASH Radiotherapy: Sleeping Beauty Awoken”, Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.D.; Hammond, E.M.; Higgins, G.S.; Petersson, K.; “Ultra-High Dose Rate (FLASH) Radiotherapy: Silver Bullet or Fool’s Gold?”, Front. Oncol. 2020, 17, 1563. [CrossRef]

- Gazis N.; Bignami A.; Trachanas E.; Alexopoulos T.; Telali I.; Apostolopoulos T.; Pramatari K.; Karagiannaki K.; Kotsopoulos D; and Gazis E.; “The Innovative FEL design by the CompactLight collaboration”. J. Phys: Conf. Series 2375 (2022) 012006. [CrossRef]

- Gazis N.; Tanke E.; Apostolopoulos T.; “Pramatari K.; Rochow R.; and Gazis E.; Light source in Europe-Case Study: The CompactLight collaboration”. Instruments 3(3) 2019, 43. [CrossRef]

- https://www.eupraxia-pp.org/.

- Giribono A., Alesini D., Bacci A., Bellaveglia M., Cardelli F., Chiadroni E., Del Dotto A., Faillace L., Ferrario M., A Gallo M., et al., “Electron beam analysis and sensitivity studies for the EuPRAXIA@SPARC LAB RF injector”, JoPhys. Conf. Series 2687 (2024) 032022. [CrossRef]

- Bayart, E.; Flacco, A.; Delmas, O.; Pommarel, L.; Levy, D.; Cavallone, M.; Megnin-Chanet, F.; Deutsch, E.; and Malka, V.; “Fast dose fractionation using ultra-short laser accelerated proton pulses can increase cancer cell mortality, which relies on functional PARP1 protein”. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10132. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H.; Li J.; Deng X.; Qiu R.; Wu Z.; and Zhang H.; “Modeling of cellular responses after FLASH irradiation: a quantitative analysis based on the radiolytic oxygen depletion hypothesis”. 2021. arXiv:2105.13138 [physics.med-ph]. [CrossRef]

- Bazalova-Carter, M.; Qu B.; Palma B.; Hardemark B.; Hynning E.; Jensen C.; and Maxim P.;, “Treatment planning for radiotherapy with very high-energy electron beams and comparison of VHEE and VMAT plans”, Med. Phys. 42 (2015) 2615–2625. [CrossRef]

- Lagzda Aangal-Kalinin D.; Jones J.; Aitkenhead A.; Kirkby K.J.; MacKay R.; Van Herk M.; Farabolini W.; Zeeshan S.; Jones R.M.;, “Influence of heterogeneous media on Very High Energy Electron (VHEE) penetration and a Monte Carlo-based comparison with existing radiotherapy modalities”. Nuclear Inst. and Methods in Physics Research, B. 482 (2020) 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Grunwald K.; Desch K.; Elsner D.; Proft D. and Thome L.; “Dose simulation of Ultra-High Energy Electron beam for novel FLASH radiaiton therapy applications”, JoPhys. Conference Series, IPAC 2023, 4993-4995. [CrossRef]

- DesRosiers, C.M.; “An evaluation of very high energy electron beams (up to 250 MeV) in radiation therapy”. PhD dissertation, Purdue University (2004). https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI3166611/.

- Maxim P.G.; Tantawi S.G.; Loo B.W.; “PHASER: A platform for clinical translation of FLASH cancer radiotherapy”. Radiother. Oncol. 139 (2019) 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Korysko P.; Dosanjh M.; Dyks L.A.; Bateman J.J.; Robertson C.; Corsini R.; Farabolini W.; Gilardi A.; Sjobak K.N.; and Ricker V.; “Updates, status and experiments of CLEAR, the CERN Linear Electron Accelerator for Research”. Proc. 13th Int. Particle Accelerator Conf. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Burkart F.; Assmann R.W.; Dinter H.; Jaster-Merz S.; Kuropka W.; Mayer F.; Stacey B.; and Vinatier T.; “The ARES linac at DESY”. Proc. 31st Int. Linear Accel. Conf. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Vinatier T.; Assmann R.W.; Burkart F.; Dinter H.; Jaster-Merz S.; Kellermeier M.; Kuropka W.; Mayer F.; and Stacey B.; “Characterization of relativistic electron bunch duration and travelling wave structure phase velocity based on momentum spectra”. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams (2023). [CrossRef]

- Clarke J.A.; Angal-Kalinin D.; Bliss N.; Buckley R.; Buckley S.; Cash R.; Corlett P.; Cowie L.; Cox G.; Diakun G.P.; et al., “CLARA Conceptual Design Report”. Science and Technology Facilities Council, 2013. https://www.astec.stfc.ac.uk/Pages/CLARA_CDRv2.pdf.

- Angal-Kalinin D.; Bainbridge A,; Brynes A.D.; Buckley R.; Buckley S.; Burt G.C.; Cash R.; Castaneda H.M.; and Christie D.; “Design, specifications, and first beam measurements of the compact linear accelerator for research and applications front end”. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 23 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Angal-Kalinin D.; Bainbridge A.; Jones J.K.; Pacey T.H.; Saveliev Y.M.; and Snedden E.W.; “The design of the Full Energy Beam Exploitation (FEBE) beamline on CLARA”, Proc. 31st Int. Linear Accel. Conf. (2022). [CrossRef]

- E.W. Snedden, et al., Specification and design for full energy beam exploitation of the compact linear accelerator for research applications, Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 27 (2024).

- Palumbo L.; Bosco F.; Carillo M.; Chiadroni E.; De Arcangelis D.; De Gregorio A.; Ficcadeni I.; Francescone D.; Franciosini G.; Guliano L.; et al, SAFEST: A compact C-band linear accelerator for VHEE-FLASH radiotherapy, Proc. 14th Int. Particle Accelerator Conf. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Guiliano L.; Carillo M.; Chiadroni E.; De Arcangelis D.; De Gregorio A.; Ficcadeni I.; Francescone D.; Franciosini G.; Magi M.; Migliorati M.; et al., SAFEST project, a compact C-band RF linac for VHEE FLASH radiotherapy, Proc. 15th Int. Particle Accelerator Conf. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Floettmann, K. ASTRA, A Space Charge Tracking Algorithm, Version 3.2; DESY: Hamburg, Germany, 2017.

- Gazis N.; Tanke E.; Trachanas E.; Apostolopoulos T.; Karagiannaki A.; Pramatari K.; Telali I.; Tzanetou K.; Gazis E.; “Photocathode study of the CompactLight Collaboration for a novel XFEL development”, Int. J. Mod Phys. Conf. Series, 50 (2020) 2060007. [CrossRef]

- Schuler, E.; Acharya, M.; Montay-Gruel, P.: Loo Jr., B.; Vozenin, M-C. and Maxim, G. P.; “Ultra-high dose rate electron beams and the FLASH effect: From preclinical evidence to a new radiotherapy paradigm”, Med. Phys. 4993) 2022: 2082-2095. [CrossRef]

- Wu YF, No HJ, Breitkreutz DY, et al. “Technological basis for clinical trials in FLASH radiation therapy: a review”, Appl Rad Oncol. 2021;10(2):6-14. (ISSN: 2334-5446). https://cdn.agilitycms.com/applied-radiation-oncology/PDFs/issues/ARO_06-21_all.pdf.

- Bazalova-Carter M, Qu B, Palma B, et al. «Treatment planning for radiotherapy with very high-energy electron beams and comparison of VHEE and VMAT plans”. Med Phys. 2015;42(5):2615-2625. [CrossRef]

- Schüler E,, Eriksson K., Hynning E, et al.Very high-energy electron (VHEE) beams in radiation therapy; treatment plan comparison between VHEE, VMAT, and PPBS. Med Phys. 2017;44(6):2544-2555. [CrossRef]

- Palma B., Bazalova-Carter M, Hårdemark B, Hynning E., Qu B., Loo B.W. and Maxim P.G.; “Assessment of the quality of very high- energy electron radiotherapy planning”. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119(1):154-158. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The simulated electron beam energies 128.3 and 446.1 MeV are not extracted, as they were exactly foreseen 120 and 450 MeV, due to the S-band cavities length. |

| Beam Characteristics | Conventional RT | FLASH RT |

|---|---|---|

| Dose Per Pulse | ~0.4 mGy | ~1 Gy |

| Dose Rate | ~102 Gy/s | ~105 Gy/s |

| Mean Dose Rate | ~0.1 Gy/s | ~100 Gy/s |

| Total Treatment Time | ~days/minutes | <500 ms |

| Beam Parameter | CLARA | CLEAR | ARES | SAFEST |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Range (MeV) | 50-250 | 60-220 | 59-155 | 80-100 |

| Bunch Charge (nC) | 0.005-0.25 | 0.01-1.5 | 0.00001-0.2 | 200 |

| Relative Energy | 0.01% (low | <0.2% | 0.039% | 0.2% |

| Spread | charge) | |||

| 0.1% (high | ||||

| Charge) | ||||

| Pulse Repetition | 1-100 | 0.8-10 | 1-50 | 100 |

| Frequency (Hz) | ||||

| Micro-bunches per | 1 | 1-150 | 1 | n/a |

| Train | ||||

| Beam Exit Window | 250 μm Be | 100 μm (Al) | 50 μm (Ti) | n/a |

| Parameters | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Photocathode material | - | Cs2Te |

| RMS laser spot size (XY) | mm | 0.90 |

| Laser pulse duration | ps | 10.00 |

| Laser rise/fall time | ps | 7.00 |

| Laser wavelength | nm | 262.0 (UVC) |

| Laser photon energy | eV | 4.73 |

| Initial kinetic energy | eV | 1.61 |

| Beam charge | nC | 1.00 |

| Electric field at cathode | MV/m | 99.00 |

| Energy distribution | Isotropic | |

| Longitudinal distribution | Uniform Ellipsoid | |

| Transverse distribution Radial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).