1. Introduction

A significant proportion of captive pinnipeds, including California sea lions (Zalophus californianus), suffer from ocular conditions such as corneal disease, premature cataracts, and lens luxations [

1,

2]. These conditions often necessitate surgical intervention, which requires precise eye positioning and complete immobility, as even minor movements can compromise surgical outcomes. Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) are therefore critical in marine mammal ophthalmic surgery to facilitate central eye position, optimize surgical conditions, reduce intraocular pressure, and improve ventilation control [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Rocuronium, a non-depolarising NMBA, is commonly used in veterinary anesthesia due to its rapid onset, intermediate duration, and favorable cardiovascular profile [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, the risk of residual neuromuscular blockade (NMB) poses a significant concern, especially in pinnipeds whose unique respiratory physiology—including voluntary apnea and a pronounced diving reflex—requires a smooth, quick and complete recovery from anesthesia [

12,

13]. Sugammadex, a modified γ-cyclodextrin, provides rapid and predictable reversal of rocuronium-induced blockade without the need for anticholinergics in small and large animals [

14,

15,

16]. Its ability to prevent residual paralysis makes it particularly valuable in high-risk species [

17,

18,

19].

Monitoring neuromuscular function is essential for the safe and effective use of NMBAs and their reversal agents. Acceleromyography (AMG) offers an objective (quantitative), real-time method of neuromuscular monitoring by measuring the acceleration of muscle contractions in response to peripheral nerve stimulation. This technique provides greater precision and objectivity compared to traditional subjective visual or tactile methods. In veterinary medicine, AMG has been successfully used in dogs, cats and horses to guide NMBA dosing and assess recovery [

17,

18,

20]. Despite its utility, the use of AMG has not previously been reported in pinniped species. One of the stimulation sites is the ulnar nerve which arises from the brachial plexus in pinnipeds, formed by the sixth cervical to the first thoracic spinal nerves [

21]. It runs along the medial aspect of the forelimb, passing posterior to the olecranon process, and provides motor and sensory innervation to the musculature and soft tissues [

22,

23]. Due to the paddle-like structure of pinniped fore flippers, the ulnar nerve remains deep, but can be accessed near the ulnar nerve groove, just medial to the olecranon making it suitable for nerve stimulation and neuromuscular monitoring [

21].

This case report presents the first documented use of sugammadex for reversing rocuronium in a California sea lion, along with the novel application of acceleromyography for intraoperative neuromuscular monitoring. The aim is to demonstrate how these tools can enhance anaesthetic safety and improve perioperative outcomes in marine mammal surgical care.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Medical History

A 19-year-old male California sea lion (Zalophus californianus), weighing 187 kg, with bilateral hyper mature cataracts was scheduled for ophthalmic surgery. One week prior to surgery, topical ophthalmic treatment was initiated to optimize ocular conditions for the procedure. The regimen included tri-antibiotic drops containing gramicidin, neomycin sulfate, and polymyxin B sulfate (Oftalmowell®, Teofarma S.R.L.), administered as one drop three times daily (TID) in both eyes (OU); ciprofloxacin 3 mg/mL (Oftacilox®, NTC S.R.L.), one drop TID OU; prednisolone 10 mg/mL (Pred Forte®, AbbVie Spain, S.L.U.), one drop TID OU; and nepafenac 3 mg/mL (Nevanac®, Novartis Europharm Limited), one drop twice daily (BID) OU.

Systemic preoperative treatment, initiated 72 hours before the procedure, consisted of oral gabapentin (Gabapentina, Kern Pharma, Spain) at 800 mg BID, prednisone (Prednisona Cinfa, Laboratorios Cinfa, Spain) at 75 mg once daily, and famotidine (Famotidina Cinfa, Laboratorios Cinfa, Spain) at 80 mg BID. Blood work performed under anesthesia revealed values within normal limits.

2.2. Anesthesia Protocol

The animal was premedicated with midazolam (Midazolam Normon, Normon, Spain) (0.2 mg/kg IM), butorphanol (Butomidor, Richter Pharma, Austria) (0.2 mg/kg IM), medetomidine (Domtor, Ecuphar, Spain) (0.01 mg/kg IM), and ketamine (Ketamidor, VetViva Richter, Austria) (1 mg/kg IM). No additional induction agents were necessary for endotracheal intubation using a 18 Fr endotracheal tube (Surgivet, USA). Anaesthesia was maintained using isoflurane (Isoflutek, Laboratorios Karizoo, Spain) in oxygen delivered via a circle system MDS Matrx VML Anesthesia Machine (MDS Inc., USA). Hypothermia prevention was ensured using two thermal blankets (Cecotec, Spain), one placed on top and one underneath the animal.

Monitoring consisted of side stream capnography, pulse oximetry (SpO2 probe placed on the tongue), electrocardiography (heart rate and arrhythmia analysis), and non-invasive blood pressure measurement, using a multi parameter monitor (Mindray PM 9000 Vet, USA). Internal body temperature was measured rectally (BioTex Temp Loop, BOSCOGEN, USA). Inspired and expired concentrations of oxygen and isoflurane were measured using a multi gas analyzer (Vamos, Dräger, Germany). All data were manually recorded every 5 minutes. Cefazolin (22 mg/kg, Cefazolina Normon, Spain) was administered intravenously (IV) 20 minutes before the start of surgery. Additionally, a saline infusion (Fisiovet, Braun, Spain) was administered IV throughout the procedure at a rate of 5 mL/kg/h.

2.3. Nerve Stimulation, Neuromuscular Blocking and Monitoring

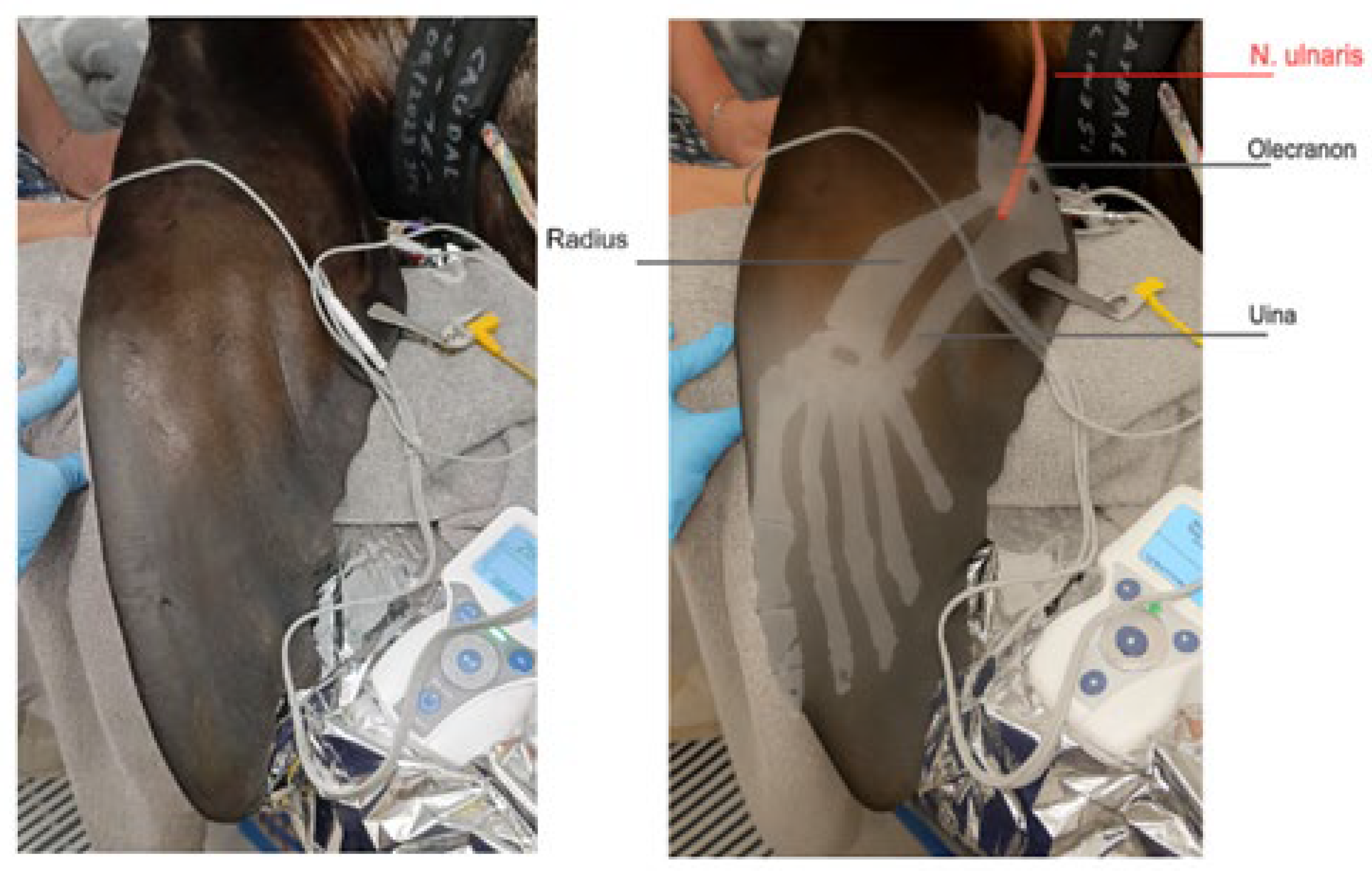

For neuromuscular blockade monitoring, the ulnar nerve was selected for stimulation using a train-of-four (TOF) stimulation pattern (Stimpod, Xavant, Australia). The sea lion was positioned in lateral recumbency with the fore flipper extended and supported to allow free movement of the limb. A transcutaneous electrical nerve mapping probe (Stimpod, Xavant, Australia) was used to locate the optimal stimulation site. The probe was applied firmly to the skin at the medial aspect of the fore flipper, near the olecranon process, and moved slowly along the inner surface of the fore flipper. The position where the current of 20 mA with stimulation of 5Hz induced maximal movement of the flipper was identified. Once the optimal position for the stimulation of the ulnar nerve was located, the stimulating electrode using a stainless steel luer-lock needle was placed through the skin at this precise site. The zero electrode was placed two centimeters proximal to the stimulation electrode on the dorsolateral surface of the antebrachial region. (

Figure 1).

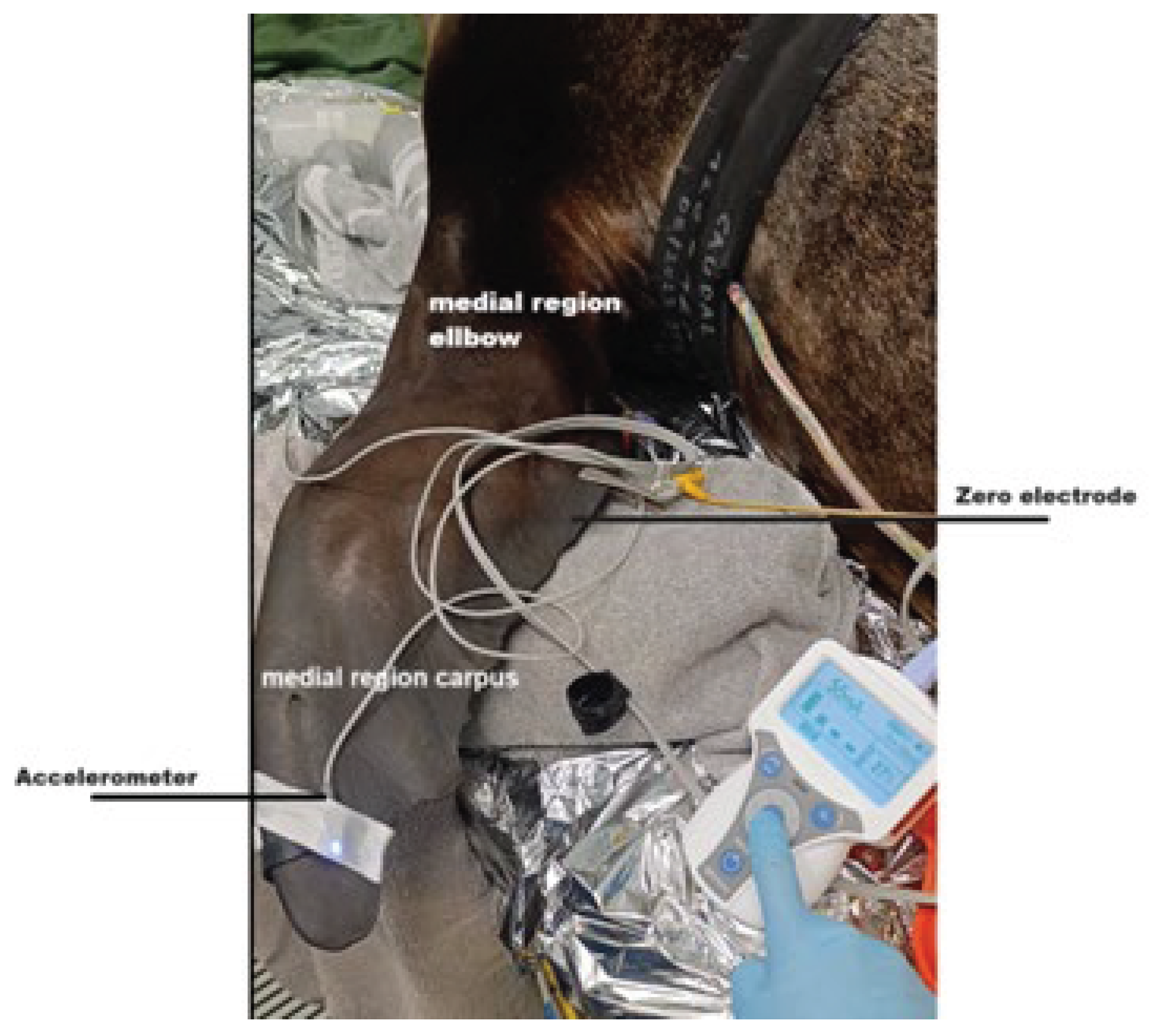

For AMG, the transducer was positioned on the dorsal side of the fore flipper, caudally, at the site of maximal movement (

Figure 2). The AMG transducer was secured with a tape, and a TOF stimulation pattern was employed, with supramaximal stimulation set at 50 mA and a frequency of 2 Hz, delivering 2-second duration pulses every 15 seconds. This allowed for continuous monitoring of NMB and ensured accurate assessment of muscle response during anaesthesia.

The monitoring was continued for a period of 10 minutes to allow stabilization of the recordings before the administration of the NMBA.

Deep NMB was achieved using rocuronium (Rocuronium Kabi, Fresenius Kabi, Germany) at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg IV for surgery of the first eye. Complete blockade (TOF count 0/4) was reached within 4 minutes. The first twitch returned 47 minutes after administration, followed by the second twitch at 51 minutes. Because the surgeon did not report any changes in eye position, a second dose of rocuronium (0.1 mg/kg IV) was administered only 83 minutes after the initial dose for the surgery on the second eye, when the TOF ratio was 31% and TOF count 4/4. Two minutes after the second dose, the TOF ratio was 35% with a TOF count of 4/4. After another 28 s, the TOF count decreased to 1/4 and remained at that level until deep NMB was achieved. Complete NMB, with no visible twitches, was achieved at 4 minutes and 48 seconds after re-dosing. The first twitch returned 37 minutes after the second dose, the second at 46 minutes. After 48 min a TOF ratio of 9% was visible. Sugammadex (Sugammadex, Fresenius Kabi, Germany) was administered at a dose of 1 mg/kg IV, 53 minutes after the second rocuronium dose, still at a TOF ratio of 9%. TOF ratio increased to 1.15 within 1 minute and 30 seconds after sugammadex administration and reached 0.9 at 54 seconds. No signs of recurarisation were observed for the following 3 minutes after which NMB monitoring was stopped.

2.4. Recovery and Postoperative Management

Recovery was smooth, with extubation performed 20 minutes after cessation of isoflurane. The animal was closely monitored during recovery, with administration of reversal drugs: atipamezole (Antisedan, Ecuphar, Belgium) (0.075 mg/kg IM), flumazenil (Flumazenil, B. Braun, Germany) (0.015 mg/kg IM), and naloxone (Naloxona, Kern Pharma, Spain) (0.01 mg/kg IM). Other postoperative medications included dexamethasone (Dexadreson, MSD Animal Health, Netherlands) (0.16 mg/kg IM), cefovecin (Convenia, Zoetis, USA) (4 mg/kg SQ), enrofloxacin (Baytril, Elanco, USA) (5 mg/kg SQ), and others as outlined.

Follow-up at five days postoperatively indicated satisfactory healing with no complications.

3. Discussion

This case provides the first documented evidence that AMG and sugammadex can be successfully applied in a California sea lion undergoing ophthalmic surgery to manage and reverse NMB. AMG was not only technically feasible in this pinniped but also clinically beneficial for optimizing both the depth and timing of NMB use and reversal.

Despite anatomical challenges—such as the modified forelimb structure and the deep location of the ulnar nerve—a transcutaneous nerve mapping probe enabled accurate identification of the stimulation site [

21,

22]. Once positioned, the AMG transducer reliably recorded TOF responses throughout anaesthesia, demonstrating that neuromuscular monitoring techniques commonly used in terrestrial species can be successfully adapted to marine mammals.

Moreover, the use of AMG allowed individualized titration of rocuronium, confirming deep NMB (TOF 0/4) within 4 minutes after a 0.3 mg/kg IV dose, which is a longer onset time but lower dose to achieve deep block than described for other land mammals, where the onset is 98 ± 52 seconds with 0.4 mg/kg IV in dogs, 46 ± 11 seconds with 0.6 mg/kg IV in cats, and 2.3 ± 2 minutes with 0.3 mg/kg IV in horses [

24,

25,

26]. It also revealed a recovery pattern that differed from domestic species. The return of the first twitch occurred 47 minutes after the initial 0.3 mg/kg IV dose and 48 minutes after a supplemental 0.1 mg/kg dose, despite a relatively low cumulative dose. In contrast, 0.3 mg/kg rocuronium typically results in a block duration of 20–35 minutes in dogs and horses, and 10–15 minutes in cats [

24,

25,

26]. Interestingly, a transient increase in TOF ratio from 31% to 35% was observed two minutes after the second rocuronium dose, despite the expected progression of neuromuscular block. This was followed by a gradual decrease in TOF count over the next several minutes, with complete NMB achieved only after 4 minutes and 48 seconds. The sea lion’s prolonged and delayed response to rocuronium suggests that pinnipeds may metabolize the drug more slowly due to species-specific hepatic clearance, reduced protein binding, or slower elimination [

27]. These findings underscore the importance of objective quantitative neuromuscular monitoring to ensure both optimal surgical conditions (onset and depth of block) and safe recovery from NMB.

Furthermore, AMG proved instrumental not only for ensuring adequate blockade during surgery but also for guiding the recovery phase. It verified complete NMB intraoperatively and enabled real-time monitoring of twitch return and TOF ratio during recovery, allowing precise dosing of the reversal agent. This individualized feedback was critical in a species lacking validated monitoring standards and highlights again AMG’s safety and utility in pinnipeds. By detecting a TOF ratio of only 9% at 53 minutes after the second dose, AMG enabled timely and precise reversal. Without such monitoring, residual blockade could have gone undetected, increasing the risk of hypoventilation, apnea, or respiratory compromise—especially in diving species with voluntary apnea and a strong diving reflex [

28,

29,

30,

31].

Importantly, AMG also guided the decision to administer a reduced dose of sugammadex (1 mg/kg), rather than the standard 2–4 mg/kg recommended in dogs and humans for moderate to deep block. This individualized titration, based on neuromuscular function rather than fixed dosing, not only ensured safety and efficacy but also minimized drug use. Considering the high cost of sugammadex, this approach may be particularly relevant in veterinary settings where financial constraints often limit access to advanced pharmaceuticals. Thus, AMG contributed not only to clinical safety but also to cost-effective anesthetic management.

The use of sugammadex for reversing rocuronium-induced blockade has been well documented in veterinary species. Reported doses range from 0.5 mg/kg in horses to 4–5.5 mg/kg in dogs and ponies, with reversal typically occurring within 2–4 minutes [

32,

33,

34]. Our case demonstrates that even a relatively low dose (1 mg/kg) can provide complete and predictable reversal in pinnipeds. This supports the feasibility and potential cost-effectiveness of a low-dose regimen in pinnipeds. Furthermore, rapid recovery minimized the risks associated with extubation. Traditional reversal agents like neostigmine are less reliable and require anticholinergic co-administration, which may cause cardiovascular and secretory side effects [

36]. Sugammadex directly encapsulates rocuronium and has demonstrated superior efficacy and safety in dogs, horses, and ponies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

37,

38]. Our findings suggest that these benefits may extend to pinnipeds as well.

Despite the positive outcome, this case highlights important limitations. There are no species-specific reference values for TOF ratios that indicate adequate spontaneous ventilation in marine mammals, nor standardized guidelines for electrode placement in pinnipeds. This lack of standardization for use of NMB monitoring complicates interpretation and raises ethical concerns, as clinicians must rely on extrapolated data from land mammals.

Although sugammadex was effective at 1 mg/kg in this case, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies are needed to define optimal dosing in pinnipeds. This is especially important in animals with hepatic or renal impairment, given interspecies metabolic variability and the liver-based clearance of rocuronium [

39]. Furthermore, due to the high cost of sugammadex, evidence-based, cost-efficient protocols are essential. While no signs of recurarization were observed, the monitoring period was short, which represents a limitation. However, no clinical signs of recurarization were noted during the observation period.

Future research should aim to establish AMG reference values and electrode positioning guidelines in marine mammals, and to characterize species-specific pharmacokinetics of rocuronium and sugammadex. Finally, developing ethical and clinical standards for NMB monitoring in pinnipeds will be essential to ensure safe and effective anaesthesia.

4. Conclusions

This case demonstrates the successful and safe use of AMG and sugammadex in a California sea lion undergoing lensectomy, marking their first documented application in a pinniped species. AMG enabled real-time, objective neuromuscular monitoring, which facilitated precise titration of rocuronium and guided the optimal dosing of the reversal agent. Sugammadex provided a rapid, complete, and complication-free recovery from neuromuscular blockade without any signs of recurarisation. These findings support the feasibility and potential benefits of incorporating these techniques into marine mammal anaesthetic protocols, while also highlighting the urgent need for species-specific reference data and standardised guidelines to optimize their application in this unique group of patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and M.M.; methodology, M.N. and M.M.; investigation, M.N. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.M., S.J., C.S., R.C. and E.H.B.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, M.M.; resources, S.J., C.S., R.C. and E.H.B.

Figure 1 was created by the authors based on an original nerve illustration. The bony anatomy was adapted from Zhao et al. (2022) [

40], and the final composition was refined using AI-assisted image generation tools (OpenAI via ChatGPT) to improve visual clarity. All elements were reviewed by the authors for anatomical accuracy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the owner of the sea lion (Mundomar Benidorm).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this case report.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mundomar in Benidorm and Oceanographic in Valencia for their support and collaboration in the care and management of the sea lion involved in this case report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Acceleromyography |

AMG |

| Bis in die, twice a day |

BID |

| Intramuscular |

IM |

| Intravenous |

IV |

| Neuromuscular Block |

NMB |

| Neuromuscular Blocking Agent |

NMBA |

| Oculus uterque, both eyes |

OU |

| Subcutaneous |

SQ |

| Train-of-Four |

TOF |

References

- Colitz, C. M. H., Adams, R., & Stein, S. (2010). Ocular disease in California sea lions: A review of the literature. Journal of Veterinary Ophthalmology, 13(3), 161-167. [CrossRef]

- Gage, L. (2011). Clinical findings and management of ocular diseases in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). Veterinary Ophthalmology, 14(4), 227-230. [CrossRef]

- Muench, L., Johnson, R., & McGill, W. (2014). The role of neuromuscular blocking agents in marine mammal anesthesia. Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 41(6), 677-688. [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, G., Miller, D., & Boettcher, C. (2017). Use of neuromuscular blocking agents in marine mammal surgery: A review. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 48(3), 648-654. [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M., Kempf, J., & Heilman, L. (2008). Anesthesia and analgesia for marine mammals. Aquatic Mammals, 34(4), 394-405. [CrossRef]

- Koch, L. A., Hohahka, S., & McDowell, A. (2015). Neuromuscular blocking agents in veterinary anesthesiology. Journal of Veterinary Anesthesia, 9(4), 220-225. [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, C., Brimacombe, J., & Mulder, G. (2016). Rocuronium in veterinary anesthesia: Current clinical applications. Veterinary Journal, 56(2), 155-160. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A., Lee, J., & Carver, M. (2011). The pharmacology of neuromuscular blocking agents. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 38(2), 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Schattauer, F.K. (1999). Anwendung des Muskelrelaxans Rocuroniumbromid (Esmeron®) beim Hund: Eine klinische Studie. Tierärztliche Praxis, 27(K), 389-395. F. K. Schattauer Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Stuttgart - New York.

- Auer, U., Uray, C., & Mosing, M. (2007). Observations on the muscle relaxant rocuronium bromide in the horse—a dose–response study. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 34, 75-81. [CrossRef]

- American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists (2007). The effect of low… Veterinary Ophthalmology, 10(5), 295–298. Blackwell Publishing Inc.

- Kaczmarek, J. (2018). Anesthesia in marine mammals: A review of physiological considerations. Aquatic Mammals, 44(4), 432-440. [CrossRef]

- Hohahka, S. (2000). The use of neuromuscular blocking agents in pinniped anesthesia. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 9(2), 102-108. [CrossRef]

- West E, Auer U, Mosing M. Reversal of vecuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade with sugammadex in dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2010;37(Suppl 1):A16. [CrossRef]

- Mosing M, Auer U, Bardell D, Jones RS, Hunter JM. Reversal of profound rocuronium block monitored in three muscle groups with sugammadex in ponies. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Oct;105(4):480-6. Epub 2010 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones RS, Auer U, Mosing M. Reversal of neuromuscular block in companion animals. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2015 Sep;42(5):455-71. Epub 2015 Jun 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugdale A, Beaumont G, Bradbrook C, Gurney M. Veterinary Anaesthesia: Principles to Practice. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2020. ISBN 978-1-119-24677-0, 146-148.

- Auer U, Mosing M. Rocuronium: neuromuscular and cardiovascular effects in anaesthetised cats. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2006;33(1):35–42. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Flores M. Neuromuscular block: Monitoring, reversal, and residual blockade in small animals. Vet Ophthalmol. 2025 Jan;28(1):88-93. Epub 2023 May 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marly, C., Gent, T., & Mosing, M. (2013). Practical application of acceleromyography to monitor neuromuscular block in a horse. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 40(5), 554–556. [CrossRef]

- Gorman, C., Anderson, R., & Higgins, D. (1998). Anatomy of the ulnar nerve in marine mammals. Journal of Anatomy, 192(4), 563-576. [CrossRef]

- Pallas, A., Moser, W., & McKenzie, A. (1997). Anatomical considerations of the ulnar nerve in pinnipeds. Journal of Anatomy, 179(3), 389-394. [CrossRef]

- Ebbesson, S. O. (1995). Neural anatomy and physiology of marine mammals. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 364(2), 198-212. [CrossRef]

- Auer, D., & Mosing, M. (2006). Clinical use of rocuronium in veterinary anesthesia. Journal of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 33(3), 340-345. [CrossRef]

- Dugdale AH, Clarke KW, Taylor PM, Castro GA. The effects of intravenous rocuronium and its reversal with neostigmine or edrophonium in the anaesthetised dog. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2002;29(1):29–35. [CrossRef]

- Auer U, Moens Y. Clinical evaluation of the neuromuscular and cardiovascular effects of rocuronium in anaesthetised horses. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2011;38(6):574–582. [CrossRef]

- Castellini, M., & Andrews, R. D. (1985). Metabolism and thermoregulation in pinnipeds. Physiological Zoology, 58(2), 157-166. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M., & Green, C. (2017). Physiological adaptations in marine mammals and their impact on anesthesia. Journal of Veterinary Anaesthesia, 46(1), 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Steffey, M., & Amsbaugh, S. (2018). Marine mammal anesthesia: An overview. Journal of Marine Animal Physiology, 47(2), 96-105. [CrossRef]

- Gales, N., & Burton, H. (1987). Respiratory physiology of marine mammals. Marine Mammal Science, 3(4), 301-318. [CrossRef]

- Fahlman, A., Cottrell, E., & Williams, K. (2018). Diving reflex and cardiovascular function in marine mammals. Aquatic Mammals, 44(2), 213-221. [CrossRef]

- Mosing, M., James, R., & Wilson, C. (2012). Sugammadex for neuromuscular blockade reversal in horses and ponies. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 39(5), 522-530. [CrossRef]

- Mosing, M., Green, S., & Jansen, P. (2010). The use of sugammadex for reversal of neuromuscular blockade in domestic animals. Equine Veterinary Journal, 42(3), 227-232. [CrossRef]

- Sugita, M., Sato, H., & Fukuda, K. (2023). Sugammadex reversal in dogs: Dosing and efficacy. Veterinary Surgery, 52(4), 528-536. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A. (2020). Pharmacological reversals in veterinary anesthesia: A comparison of sugammadex and neostigmine. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 43(5), 622-630. [CrossRef]

- Hristovska, I., McGill, L., & Thomas, M. (2018). Sugammadex: A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical applications. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 45(2), 137-149. [CrossRef]

- Plaud, C., & Cook, G. (2020). Sugammadex and its role in reversing neuromuscular blockade. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, 23(1), 95-104. [CrossRef]

- Säre, M. (2012). This research further supports the finding that sugammadex does not produce cardiovascular side effects in canine subjects. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia Journal. https://www.vaajournal.org/article/S1467-2987(16)30212-4/fulltext.

- Auer, D., & Mosing, M. (2006). Clinical use of rocuronium in veterinary anesthesia. Journal of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 33(3), 340-345. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Fang, H. Development and Performance Analysis of Pneumatic Soft-Bodied Bionic Flipper. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24(2), 2101566. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).