Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

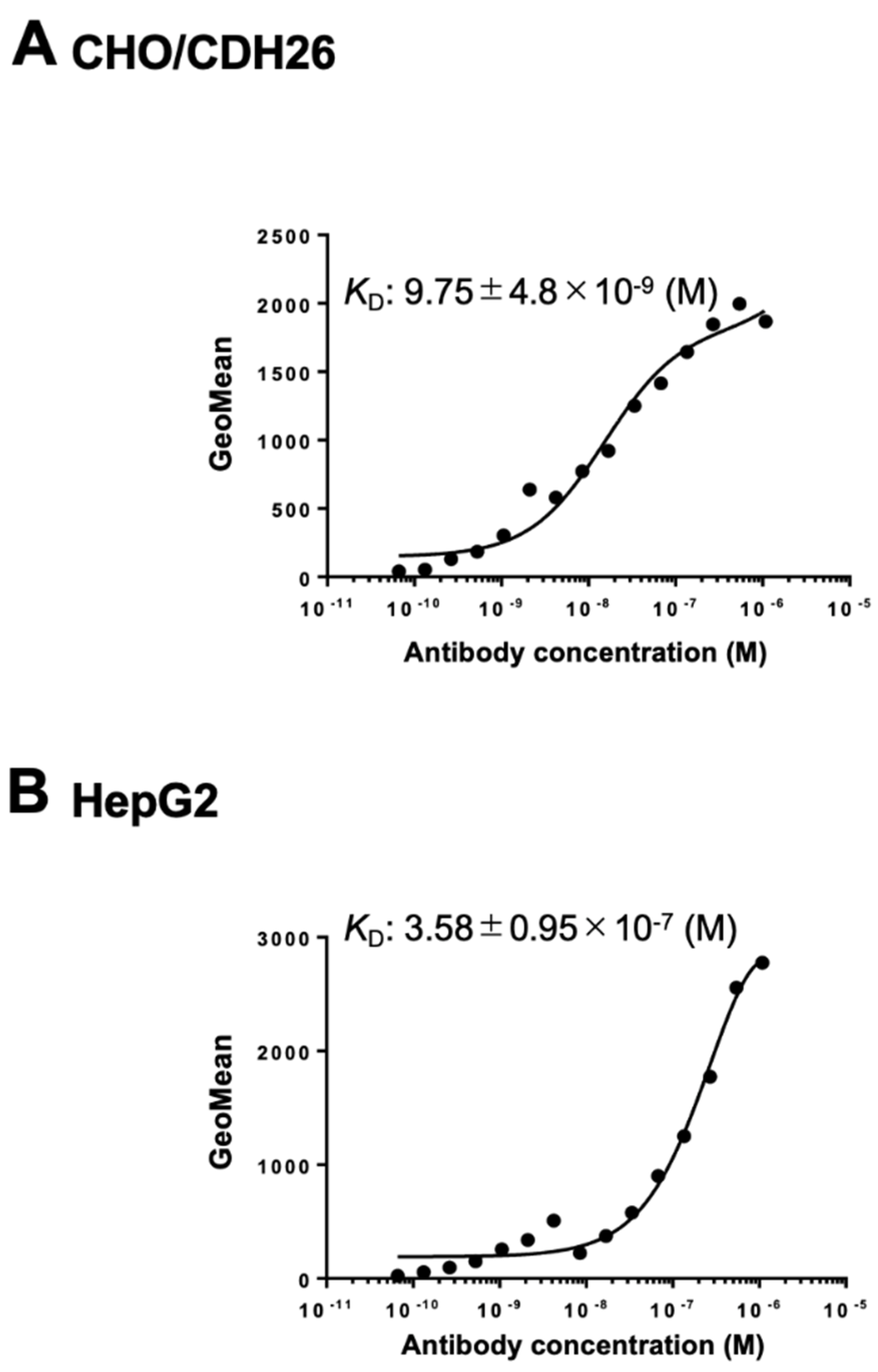

Cadherin 26 (CDH26) is a recently identified member of the cadherin superfamily. Although CDH26 gene expression has been reported in association with allergic inflammatory responses, the protein expression levels and the signaling pathways mediated through its interactions with other proteins remain poorly understood. This is primarily due to the lack of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that can recognize the intact, cell surface-expressed form of CDH26. In this study, we developed an anti-human CDH26 mAb, Ca26Mab-6 (IgM, kappa), using the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method. Ca26Mab-6 demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for CDH26 in flow cytometry, and did not bind to CHO-K1 cells, which overexpress any of the other type I or type II cadherins. Ca26Mab-6 successfully detected endogenous CDH26 protein expression in HepG2, U-87 MG, MCF7, and 293FT cells. The dissociation constant of Ca26Mab-6 was determined to be 9.8 ± 4.8 × 10⁻⁹ M for CDH26-overexpressed CHO-K1 (CHO/CDH26) cells and 3.6 ± 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ M for HepG2 cells. The detection of CDH26 expression in cancer cells may offer new insights into the potential relationship between inflammatory responses and malignant transformation. Therefore, Ca26Mab-6, developed using the CBIS method, is expected to facilitate functional studies of CDH26 and contribute to the development of CDH26-targeted antibody-based therapies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Plasmid Construction and Establishment of Stable Transfectants

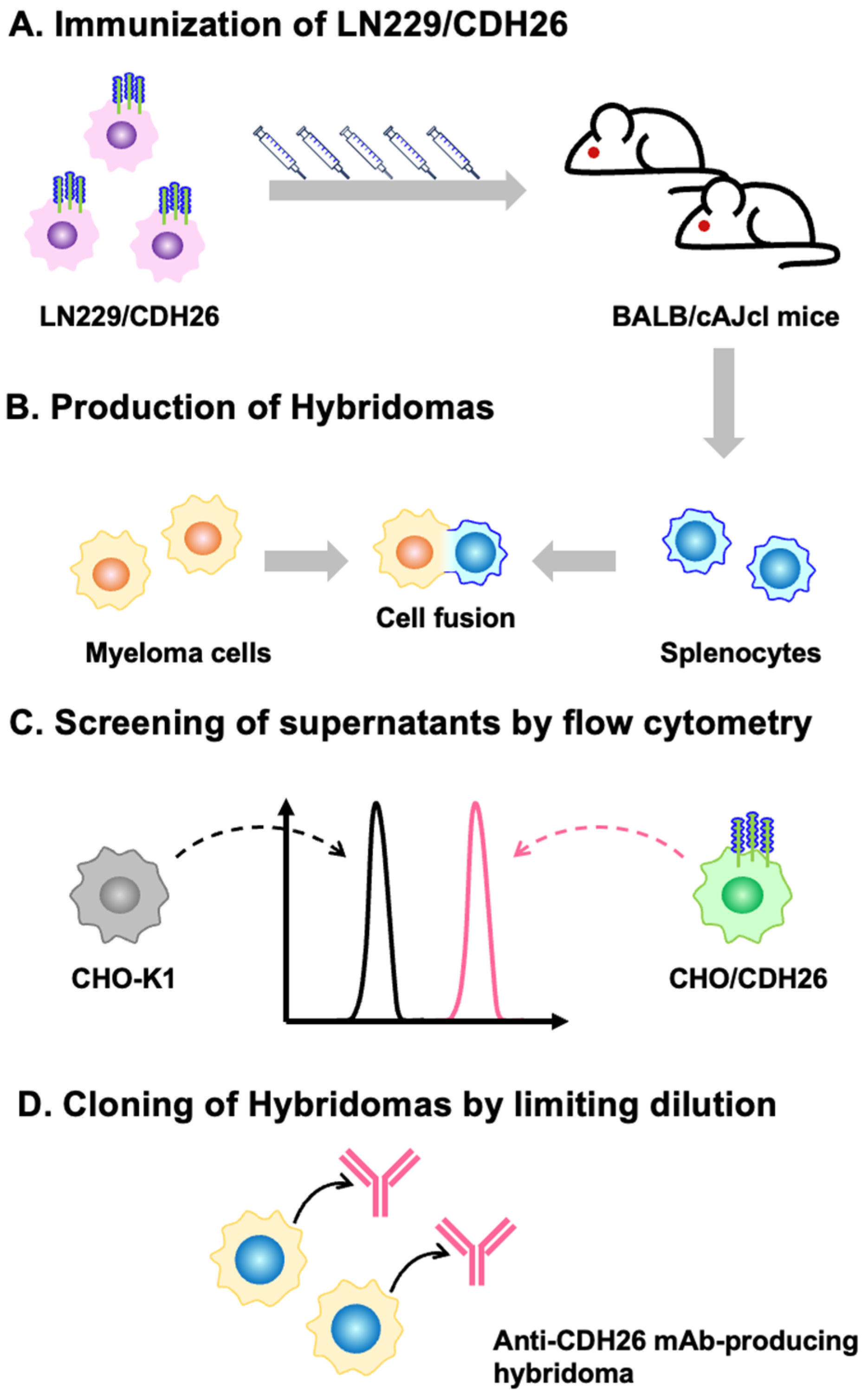

2.3. Hybridoma Production

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Determination of the Binding Affinity by Flow Cytometry

3. Results

3.1. Development of Anti-CDH26 mAbs

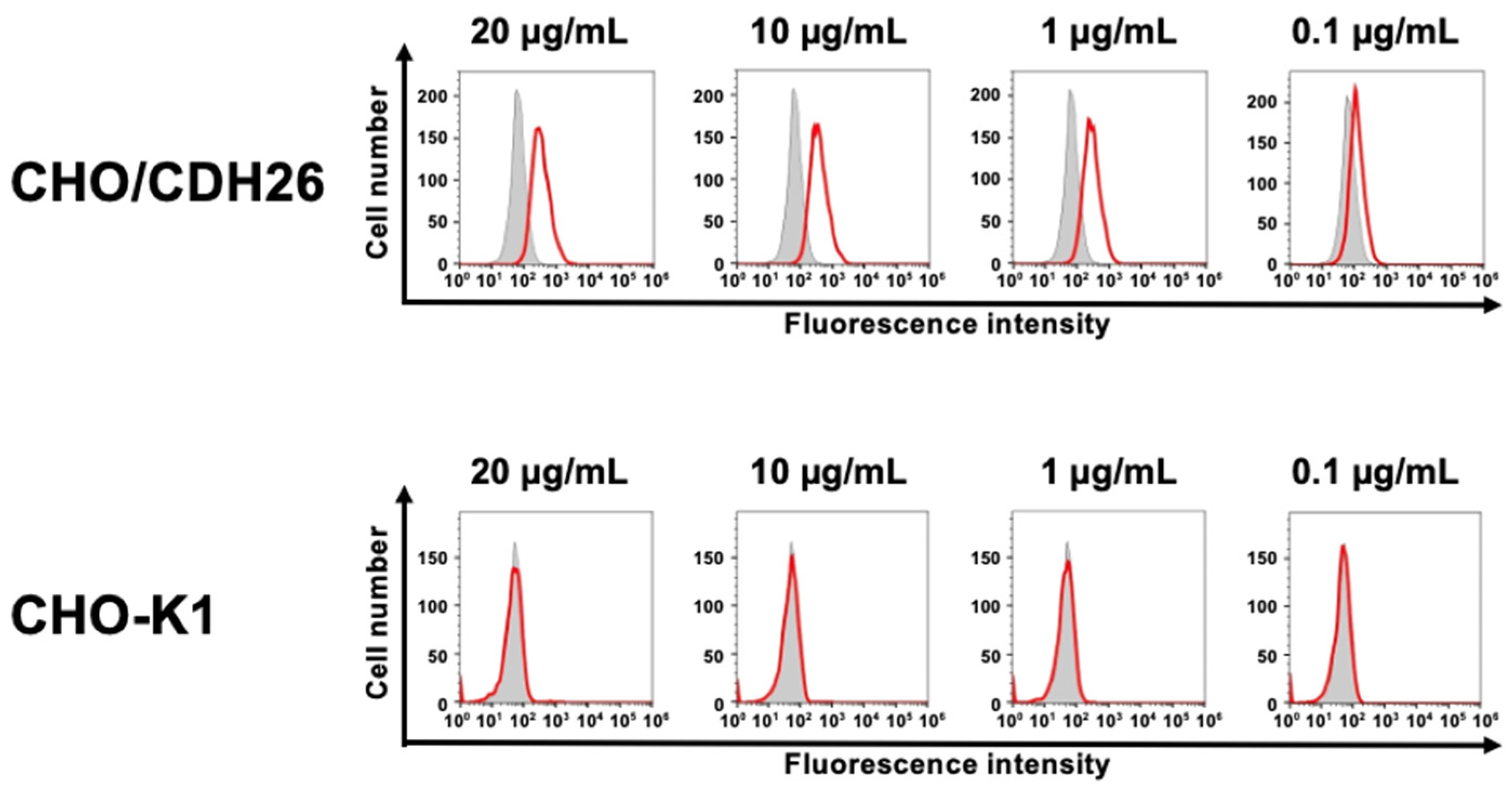

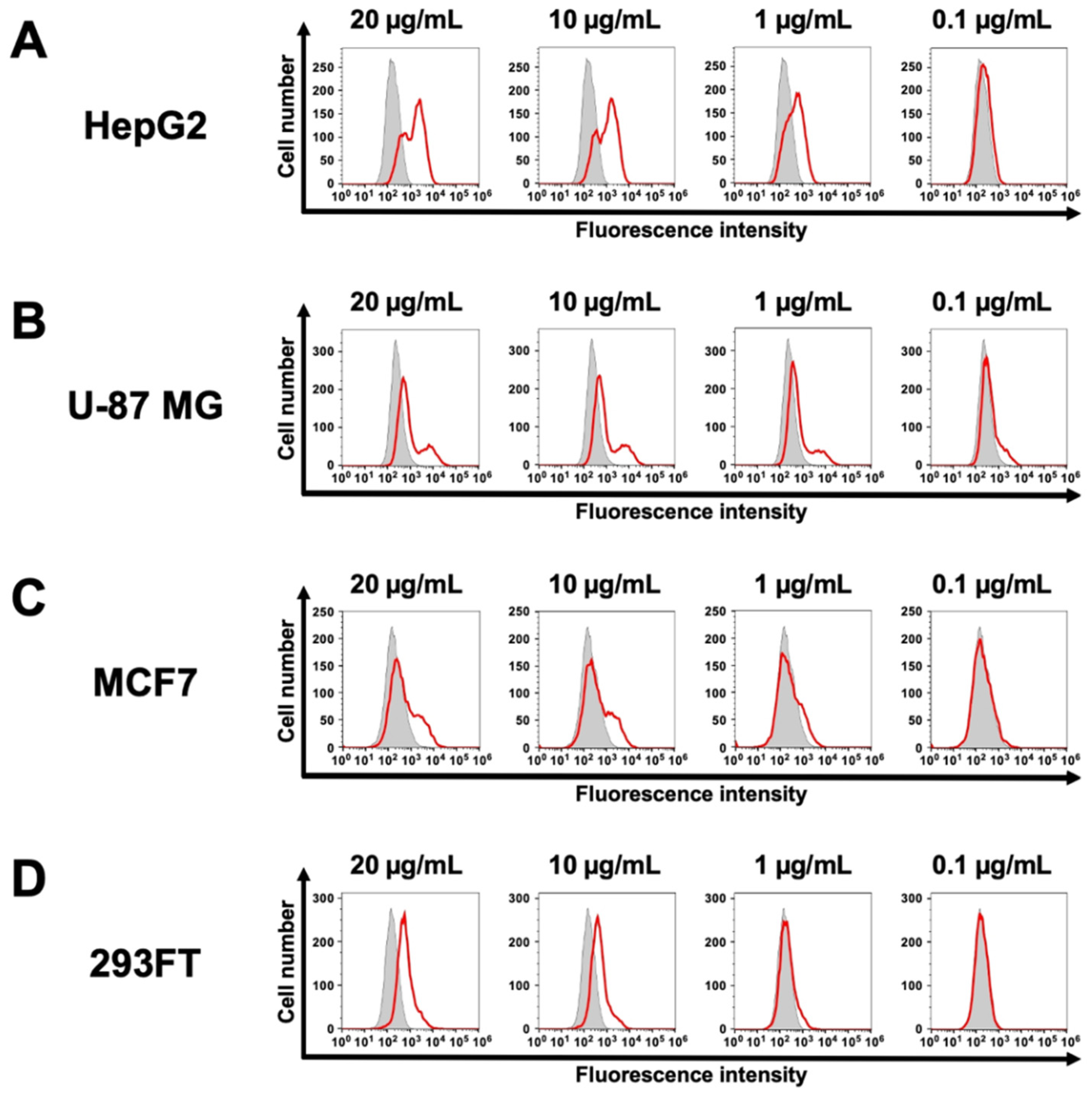

3.2. Investigation of the Reactivity of Ea4Mab-3 Using Flow Cytometry

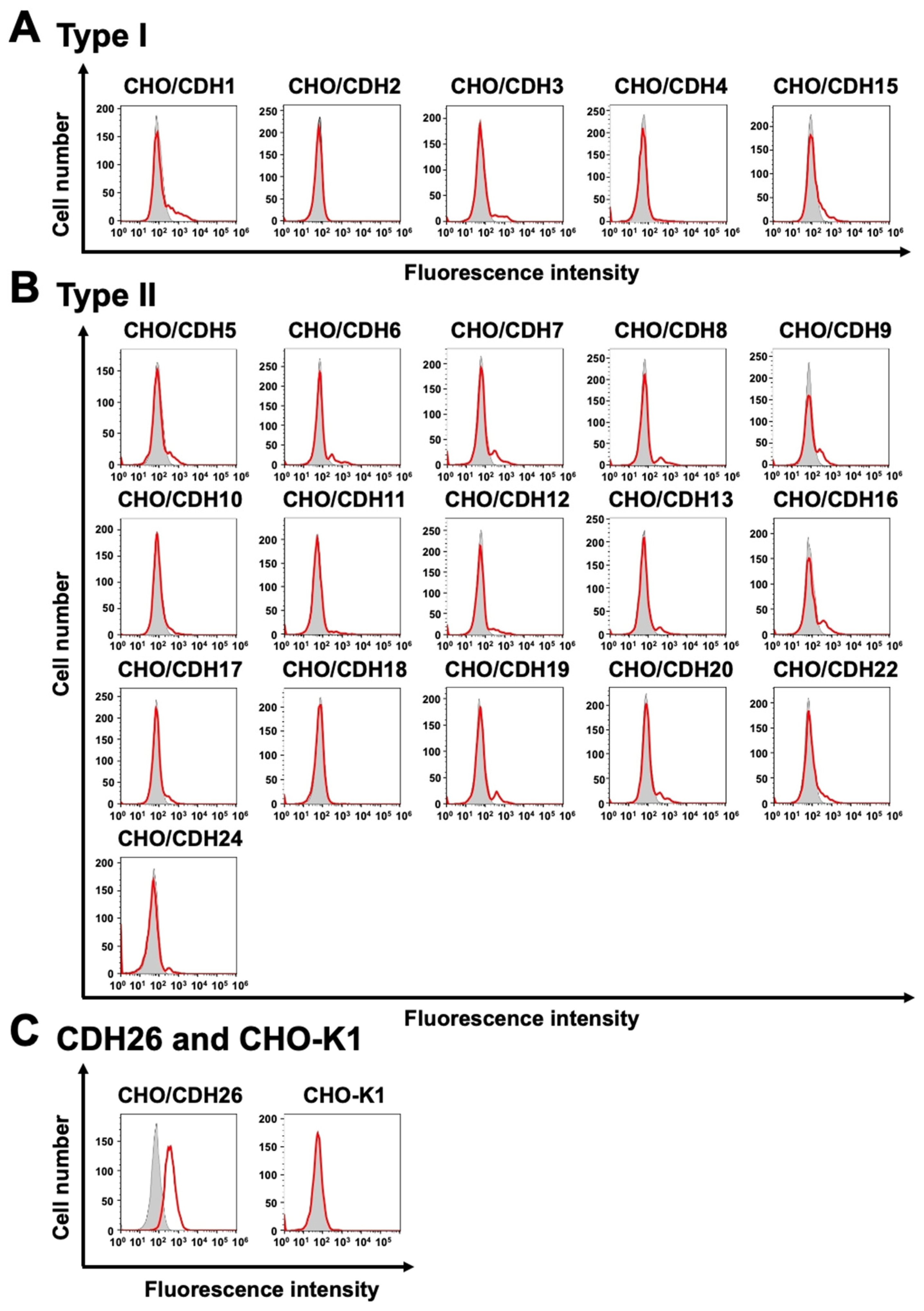

3.3. Analysis of the Specific-Reactivity of Ca26Mab-6 to CDH26 Using CHO-K1 Cells Expressed Various Cadherins

3.4. Determination of KD Values of Ca26Mab-6 by Flow Cytometry

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colas-Algora, N.; Millan, J. How many cadherins do human endothelial cells express? Cell Mol Life Sci 2019;76(7): 1299-1317. [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, M. Historical review of the discovery of cadherin, in memory of Tokindo Okada. Dev Growth Differ 2018;60(1): 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, M. Self-organization of animal tissues: cadherin-mediated processes. Dev Cell 2011;21(1): 24-26. [CrossRef]

- Oda, H.; Takeichi, M. Evolution: structural and functional diversity of cadherin at the adherens junction. J Cell Biol 2011;193(7): 1137-1146. [CrossRef]

- Hyafil, F.; Babinet, C.; Jacob, F. Cell-cell interactions in early embryogenesis: a molecular approach to the role of calcium. Cell 1981;26(3 Pt 1): 447-454. [CrossRef]

- Hulpiau, P.; van Roy, F. Molecular evolution of the cadherin superfamily. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009;41(2): 349-369. [CrossRef]

- Oas, R.G.; Nanes, B.A.; Esimai, C.C.; et al. p120-catenin and beta-catenin differentially regulate cadherin adhesive function. Mol Biol Cell 2013;24(6): 704-714. [CrossRef]

- Gumbiner, B.M. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell 1996;84(3): 345-357. [CrossRef]

- Halbleib, J.M.; Nelson, W.J. Cadherins in development: cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes Dev 2006;20(23): 3199-3214. [CrossRef]

- Leckband, D.; Prakasam, A. Mechanism and dynamics of cadherin adhesion. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2006;8: 259-287. [CrossRef]

- Troyanovsky, R.B.; Laur, O.; Troyanovsky, S.M. Stable and unstable cadherin dimers: mechanisms of formation and roles in cell adhesion. Mol Biol Cell 2007;18(11): 4343-4352. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.J.; Nusse, R. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science 2004;303(5663): 1483-1487. [CrossRef]

- Polanco, J.; Reyes-Vigil, F.; Weisberg, S.D.; Dhimitruka, I.; Bruses, J.L. Differential Spatiotemporal Expression of Type I and Type II Cadherins Associated With the Segmentation of the Central Nervous System and Formation of Brain Nuclei in the Developing Mouse. Front Mol Neurosci 2021;14: 633719. [CrossRef]

- Breier, G.; Breviario, F.; Caveda, L.; et al. Molecular cloning and expression of murine vascular endothelial-cadherin in early stage development of cardiovascular system. Blood 1996;87(2): 630-641. [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, M. Cadherins in cancer: implications for invasion and metastasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1993;5(5): 806-811. [CrossRef]

- Canel, M.; Serrels, A.; Frame, M.C.; Brunton, V.G. E-cadherin-integrin crosstalk in cancer invasion and metastasis. J Cell Sci 2013;126(Pt 2): 393-401. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.M.; Collins, M.H.; Kemme, K.A.; et al. Cadherin 26 is an alpha integrin-binding epithelial receptor regulated during allergic inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 2017;10(5): 1190-1201. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y. Cadherin Signaling in Cancer: Its Functions and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Front Oncol 2019;9: 989. [CrossRef]

- Mrozik, K.M.; Blaschuk, O.W.; Cheong, C.M.; Zannettino, A.C.W.; Vandyke, K. N-cadherin in cancer metastasis, its emerging role in haematological malignancies and potential as a therapeutic target in cancer. BMC Cancer 2018;18(1): 939. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhu, X. Restoring E-cadherin Expression by Natural Compounds for Anticancer Therapies in Genital and Urinary Cancers. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2019;14: 130-138. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.F.; Paredes, J. P-cadherin and the journey to cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer 2015;14: 178. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Z.; Bai, W. Knockdown of Cadherin 26 Prevents the Inflammatory Responses of Allergic Rhinitis. Laryngoscope 2023;133(7): 1558-1567. [CrossRef]

- Esnault, S.; Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Altman, M.C.; et al. Identification of bronchial epithelial genes associated with type 2 eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz-Scroggins, M.E.; Gordon, E.D.; Wesolowska-Andersen, A.; et al. Cadherin-26 (CDH26) regulates airway epithelial cell cytoskeletal structure and polarity. Cell Discov 2018;4: 7. [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-CDH15/M-cadherin monoclonal antibody Ca15Mab-1 for flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025;43: 102138. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014;95: 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016;35(6): 293-299. [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. 2025.

- Zhou, B.; Ho, S.S.; Greer, S.U.; et al. Haplotype-resolved and integrated genome analysis of the cancer cell line HepG2. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47(8): 3846-3861. [CrossRef]

- Pokorna, M.; Hudec, M.; Jurickova, I.; et al. All-Trans Retinoic Acid Fosters the Multifarious U87MG Cell Line as a Model of Glioblastoma. Brain Sci 2021;11(6). [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, U.; Siranosian, B.; Ha, G.; et al. Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature 2018;560(7718): 325-330. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(3). [CrossRef]

- Arimori, T.; Mihara, E.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Locally misfolded HER2 expressed on cancer cells is a promising target for development of cancer-specific antibodies. Structure 2024;32(5): 536-549 e535. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).