1. Introduction

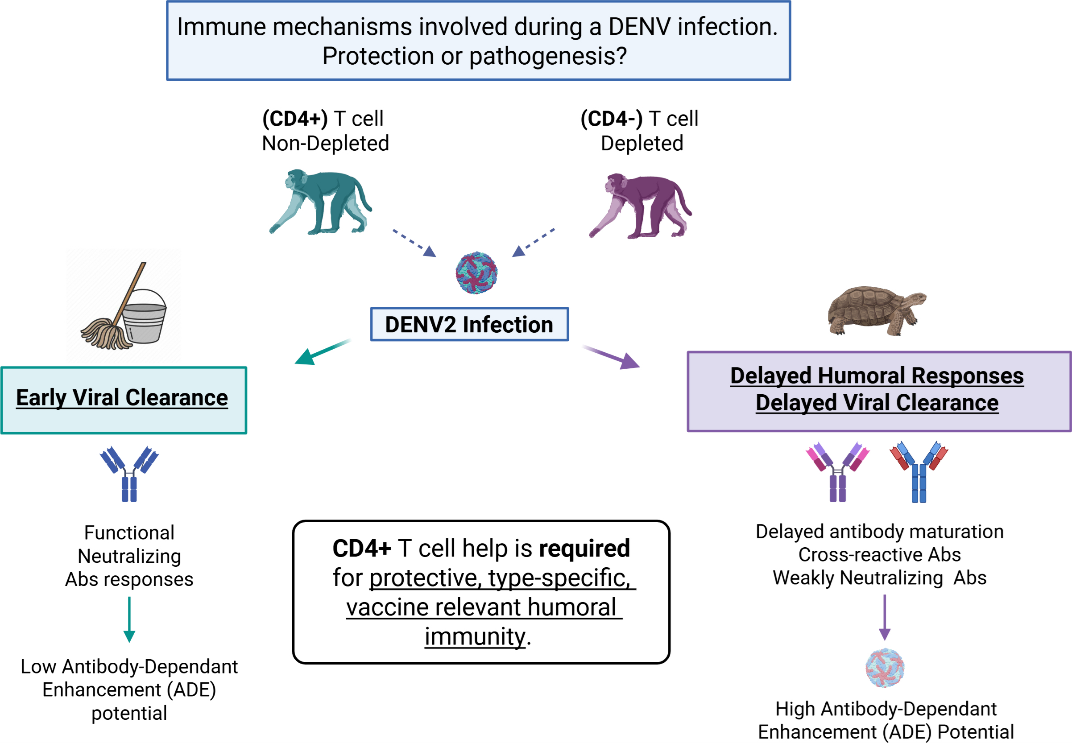

Despite existing vaccine efforts (e.g., Dengvaxia, TAK-003), concerns remain over non-neutralizing antibody responses and ADE. Elucidating the cellular drivers of protective humoral immunity during primary DENV infection is thus essential for improved vaccine design. Dengue virus (DENV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) are globally significant mosquito-borne flaviviruses that continue to pose increasing public health challenges, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions [1-5]. DENV alone accounts for an estimated 390–500 million infections annually, with a substantial burden of morbidity and mortality, particularly in cases progressing to severe manifestations such as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS) [6-8]. Factors such as rapid urbanization, ecological and climatic shifts play pivotal roles in both the expanding range of the mosquito (

Aedes aegypti) vector and in creating more breeding sites close to highly populated areas [

9].

Despite substantial advances in our understanding of DENV biology and immunology, the immune correlates that distinguish protective from pathogenic responses during primary infections remain poorly defined, complicating vaccine development efforts. One of the most controversial and complex aspects of flavivirus immunity is the dual role of antibodies. Type-specific (TS) neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) generated during a primary infection are critical for long-term protection against the homologous DENV serotype. However, antibodies that are cross-reactive (CR) but weakly neutralizing can enhance viral replication during a secondary infection with a heterologous serotype via antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), a phenomenon well documented in both human and animal studies [10-13]. This paradoxical role of antibodies highlights the need to better understand the qualitative features of the humoral response during primary DENV infections.

The complexity of the DENV antigenic landscape further complicates our understanding of humoral immunity. The DENV envelope (E) protein includes both TS epitopes unique to each serotype and CR epitopes shared across all four serotypes and with other flaviviruses such as ZIKV [14-17].

While the roles of CD8+ T cells and neutralizing antibodies in DENV immunity have been extensively studied [18-25], the contribution of CD4+ T cells—especially follicular helper T cells (Tfh)—has received less attention [

26,

27]. CD4+ T cells are essential for initiating and maintaining germinal center (GC) reactions that support B cell activation, class switching, affinity maturation, and the generation of memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells [28-30]. Tfh cells are critical for fine tuning the antibody response by supporting antibodies against foreign antigens while limiting the development of autoreactive antibodies [

31,

32]. Through these mechanisms Tfh cells have the potential to modulate the support of B cells that produce cross-reactive antibodies. These processes are central to the development of durable, high-affinity, and serotype-specific antibody responses. However, the mechanistic role of CD4 T cells and its subpopulations in shaping the B cell response during a first DENV exposure remains unclear. Similarly, despite the recognized importance of antibody quality and specificity, the immune mechanisms that drive the early selection, expansion, and functional tuning of B cell responses during primary infections remain poorly defined [33-35]. In particular, it is unknown how CD4+ T cell help—or its absence—impacts the emergence of TS versus CR antibodies, the kinetics of class switching, and the potential for cross-reactive but non-neutralizing responses with ADE potential.

In this study, we used a non-human primate (NHP) model to interrogate the role of CD4+ T cells during a primary DENV2 infection. Rhesus macaques were either depleted of CD4+ T cells prior to infection or left undepleted as controls. We assessed the effects of CD4+ T cell absence on viral kinetics, B cell activation, antibody specificity, isotype switching, neutralization capacity, and cross-reactivity to other DENV serotypes and ZIKV.

Our findings demonstrate that CD4+ T cells are essential for timely viral clearance, robust isotype class switching, and the development of TS neutralizing antibodies. In their absence, animals exhibited delayed antibody responses, increased early activation of polyclonal naïve and memory B cells, reduced early neutralization capacity, and enhanced production of CR antibodies targeting both E and NS1 proteins. These changes were associated with increased ZIKV cross-reactivity and ADE potential. Together, our results underscore the critical role of CD4+ T cells in shaping the quality and durability of humoral immunity during primary DENV infections and highlight their relevance in designing vaccines that aim to elicit safe and protective immune responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Model

Young adult (4–7 years of age) male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), seronegative for DENV and ZIKV, were housed in the CPRC facilities at the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institute’s Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico (IACUC-UPR-MSC), and performed in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) (Animal Welfare Assurance number A3421; protocol number, 7890116). In addition, the study was conducted following the USDA Animal Welfare Regulations, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and institutional policies, to ameliorate animal suffering by the recommendations of the Weatherall Report on the use of nonhuman primates in research. All procedures were conducted under anesthesia by intramuscular injection of ketamine at 10–20 mg/kg of body weight, as approved by the IACUC. Anesthesia was delivered in the caudal thigh using a 23-gauge sterile syringe needle. During the entire study period, the macaques were under the facility’s environmental enrichment program, which was also approved by the IACUC. Animals were continuously monitored by trained veterinarians at the Animal Research Center.

A total of 29 flavivirus-naïve Indian-origin rhesus macaques (

Macaca mulatta) were selected and divided into two groups with 12 in group 1 (G1) and 17 animals in group 2 (G2) (

Figure S1).

Depletion of CD4+ T cells was performed in G1 by initial subcutaneous (s.c.) administration of 50 mg/kg of anti-CD4+ Ab at 15 days pre-infection, followed by two intravenous (i.v.) administrations of 7.5 mg/kg at 13- and 9- days pre-infection. Control animals in G2 were administered phosphate saline (PBS).

2.2. Viral Stock

DENV2 New Guinea 44 (NGC) strain (provided by Steve Whitehead, NIH/NIAID, Bethesda, MD) was used to infect macaques at different time points. In addition, DENV2 virus was used for neutralization assays, as well as DENV1 Western Pacific 74, DENV3 Sleman 73, DENV4 Dominique (all three kindly provided by Steve Whitehead (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and ZIKV PRVABC59 (ATCC VR-1843) strains. Viruses were expanded and tittered by plaque assay and qRT-PCR using protocols standardized in our laboratories.

2.3. Depletion Treatment, Viral Infection, and Sample Collection

A total of 29 rhesus macaques seronegative for DENV and ZIKV were housed in the CPRC facilities, at the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico. Macaques were divided into two cohorts based on their future T cell-depletion status. Twelve (12) animals were depleted of CD4

+ T cells by administration of anti-CD4 Ab CD4R1 (NHP Reagent Resource;

https://www.nhpreagents.org). Administration of the depletion treatment consisted of an initial s.c. inoculation of 50 mg/kg at 15 days prior to viral infection, followed by two i.v. injections of 7.5 mg/kg 13 days and 9 days before viral infection respectively. The seventeen (17) remaining animals received phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control treatment. Both cohorts were then infected with DENV2 NGC strain (5.0 x 10

5 pfu s.c.), denoted from here on as the primary infection (p.i.). Blood samples were collected on days

-15,

-12, and

-9 pre-infection, and during the first fifteen consecutive days after infection, followed by monthly sample collection. Collected samples included serum, heparinized whole blood, and citrate whole blood for PBMC isolation. Macaques were monitored after treatments and infections by trained veterinarians for evidence of disease and clinical status. Rectal and external temperatures and weights were taken on day 0 and every other day pre- and post-infection timepoint. A summary of the experimental design and groups is provided (

Figure S1).

2.4. Immunophenotyping

Phenotypic characterization of Rhesus macaque’s adaptive immune response was performed by 16 -multicolor flow cytometry using fluorochrome-conjugated Abs at several time points. Depletion efficacy was confirmed by measuring the frequency of CD4

+ T cells on the following timepoints: pre-treatment/depletion baseline (-15), and days -14, -12, and -8 pre-infection. In addition, CD4

+ T cell frequency was measured on baseline and days 1, 2, 3, 7, 15, 30, 60, and 90 p.i.. Aliquots of 150 uL of heparinized whole blood were incubated with a mix of antibodies for 30 min. in the dark at room temperature. After incubation, red blood cells were fixed and lysed with BD FACS fix and lyse solution, and cells were washed twice with BSA 0.05%. Samples were analyzed using a MACSQuant

® Analyzer 16 Flow Cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, CA). Antibodies used in this study were: CD8-FITC (DK25) from Sigma; CD3- PerCP (SP34), Ki67- Viogreen (B56), CD4- APC (L200), CD69- PeCy7 (FN50), CD95- PE (DX2), IgG- APC- H7 (G18- 145), CD11b- AF 700 (ICRF44), CD80- BV650 (L307.4), CD27- PE (M-T466) from BD Biosciences; CD20- PacBlue (2H7), HLA-DR- BV570 (L243), CD138- FITC (DL- 101), ICOS- PE/Dazzle 594 (C398.4H), CXCR3- PE Cy7 (GO25H7), PD-1- BV650 (EH12.2H7) from Biolegend; CD28- APC- Vio770 (I5E8) and CCR7- PerCP Vio770 (REA546) from Miltenyi; CXCR5- PE (MU5UBEE) from Thermo eBiosciences; and CD38- APC (AT-1) from Adipogen. For analysis, lymphocytes (LYM) were gated based on their characteristic forward and side scatter patterns. T cells were defined as CD3

+CD20

-, CD4

+ T cells (CD3

+CD20

-CD4

+), CD8

+ T cells (CD3

+CD20

-CD8

+), and subpopulations were determined within CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells and defined as naïve (CD3

+CD20

-CD28

+CD95

-), effector memory (EM) (CD3

+CD20

-CD28

-CD95

+), and central memory (CM) (CD3

+CD20

-CD28

+CD95

+). Gating strategy for T cells is presented on

Supplementary Figure S4 (

Figure S4). All data from cell population frequencies and immune markers expression were analyzed using Flow/Jo software and GraphPad Prism (FlowJo LLC Ashland, OR).

B cells were defined as CD20+CD3-, Memory (MBC= CD20+, CD3-, CD27+), class-switched IgG Memory (IgG MBC= CD20+, CD3-, CD27+, surface IgG+ (sIgG)), and unclass-switched memory B cells (CD3-CD20+CD27-). Activated phenotypes were measured via the inclusion of the CD69+ marker. Gating strategy for B cells and subsets is presented (

Figure S11).

2.5. qRT- PCR

DENV2 viral RNA for real-time PCR assay was extracted from 200uL of virus isolate (previously tittered by FRNT) and from acute serum samples using a MagMax Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems, MA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral RNA extraction was performed using a KingFisher Duo Prime Purification System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA). In brief, a Viral Pathogen DNA/RNA binding magnetic bead solution is prepared, 200uL of sera, 500uL of Viral Pathogen Nucleic Acid isolation kit wash buffer, 5uL of a protein kinase solution, and 1mL of ethanol solution (80% ethanol in DNAse free water) were added to specified wells in a KF Duo Deepwell 96 plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) and loaded on the KingFisher Duo Prime Purification System. Purified RNA was collected and stored at -80oC in kit elution buffer solution. Real-time PCR for DENV2 isolated RNA was carried out using the Genesig Real-Time PCR detection kit for Dengue Virus (Primer Design, UK) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a kit Positive Control is diluted in 500uL of a kit Template buffer and a series of tenfold dilutions were prepared as follows: 2 x 105/uL, 2 x 104/uL, 2 x 103/uL, 2 x 102/uL, 20/uL, 2/uL (copy number/ mL). For the reaction mix, 10uL of oasig 2X Precision one step qRT-PCR was combined with 1uL of kit probe/primer mix and 4uL of sterile water, for a total volume of 20uL once the RNA sample was added. The reaction mix was added to a 96 well plate, alongside the experimental RNA samples, a kit non-template control (NTC), an RNA extraction negative control (DNAse free water), a positive control (RNA extraction from virus stock), and calibration standards, in specified wells. The plate was then loaded, and the RT-PCR reaction was performed using a Quant Studio 5 Real-Time PCR Instrument (Applied Biosystems, MA). For quantification, a standard curve was generated from the ten-fold dilutions of the kit RNA positive control.

2.6. ELISAs for Detection of DENV NS1 Antigen and DENV Anti-NS1 IgG

Detection of DENV NS1 antigen and DENV anti-NS1 IgG after primary DENV2 infection was measured using commercial kits (InBios, International Inc, Seattle). The assays were performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Timepoints measured include baseline and days 3, 5, 7, 15, and 30 p.i. for DENV NS1, and baseline and days 15, 30, and 90 p.i. for DENV anti-NS1 IgG. For the DENV anti-NS1 IgG assay, no limit of detection or cut-off value is provided because this value will vary depending on flavivirus disease prevalence in the geographical location where the test is performed. For that reason, the cut-off was set to two standard deviations (SD) of the average OD from the readings of negative baseline samples before exposure to the virus.

2.7. ELISAs for DENV and ZIKV Antibodies

Serostatus of animals for DENV and ZIKV was assessed before and after DENV2 infection using DENV IgG/IgM commercial kits (Focus Diagnostics, CA). ZIKV serostatus was also assessed using a commercial kit for ZIKV IgM (InBios, International Inc, Seattle) and ZIKV IgG (XpressBio, Frederick, MD). Timepoints measured include baseline and days 7, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 90 p.i.. All assays were performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions and as described by our group [36-38].

2.8. Endpoint Dilution Binding Assay

As previously described by our group [

39], endpoint dilution assay was performed by a capture ELISA assay using samples from a late convalescent timepoint that was 320 days for the CD4-depleted group and 286 days for the undepleted group. For normalization purposes, a reference timepoint of 300 days p.i. was used. Coating buffer (Sigma, 08058) with antigens DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4 (Fitzgerald), or ZIKV (MyBiosource) was incubated overnight at 4°C in a 96 well plate at concentration of 2.5 ug/mL for each antigen. After coating, unbound antigen was washed with PBS 0.05% Tween 20 and further blocked with 5% BSA (Fisher) for 1h at 37°C. Serum samples were then serially diluted (1:100, 1:3) using blocking buffer (BSA 5%) and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. All unbound antibodies were removed by washing, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C with goat-anti-human secondary Ab conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Bio-Rad, CA). Lastly, unbound secondary Ab was washed off, and signals were developed with o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride substrate tablets (Sigma, 34006). Plate wells were read at 492 nm optical density (OD).

2.9. EDIII and NS1 Antigen Production

ZIKV (H/PF/2013) EDIII antigen used in this study was produced as previously described [

40]. EDIIIs of all four DENV serotypes were also cloned and expressed similarly to ZIKV EDIII. Briefly, codon-optimized genes encoding the EDIIIs of DENV1 (AAB70694·1, E protein aa 297-394), DENV2 (ADA00411·1, E protein aa 297-394), DENV3 (AAB69126·2, E protein aa 295-392) and DENV4 (ADA00410·1, E protein aa 297-394) with an N-terminal human serum albumin signal peptide, a polyhistidine tag, and a HaloTag were cloned into the mammalian expression plasmid pαH. Recombinant DENV EDIII antigens were expressed in mammalian Expi293 cells and purified from the culture supernatant using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen). Purified EDIII antigens were biotinylated using HaloTag PEG biotin ligand (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For NS1 antigen production, codon-optimized genes encoding the NS1s of DENV1 NS1 Region 37, DENV2 NS1 Region 39, DENV3 NS1 Region 22, DENV4 NS1 Region 45 and ZIKV NS1 Region 47 were used. Mobility-shift analysis was used to assess the biotinylated EDIII antigens using SDS-PAGE. The mammalian expression plasmids and sequences will be made available in the plasmid repository and Genbank, respectively.

2.10. Coupling of EDIII Antigens to Beads via Avidin-Biotin Interaction

Site-specifically biotinylated EDIII antigens were coupled to unique MagPlex®-Avidin Microspheres. Antigen reading regions (specific antigen location in the microsphere bead) for the Luminex signal detection were, BSA (region 22), DENV1 (region 12), DENV2 (region 26), DENV3 (region 36), DENV4 (region 38), and ZIKV (region 30) at a concentration of 5 μg of antigen per 106 beads in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4) for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking at 700 rpm. Beads were then washed/blocked three times in blocking buffer (PBS + 1% BSA) and resuspended in wash buffer at 2x106 beads/mL.

2.11. Coupling of Biotinylated NS1 Antigens to Beads via Avidin-His-Tag Ab Interaction

Site-specifically biotinylated NS1 antigens were coupled to unique MagPlex®-Avidin Microspheres using a His-Tag antibody incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking at 700 rpm, prior to the NS1 antigen coupling. Antigen reading regions (specific antigen location in the microsphere bead) for the Luminex signal detection were, BSA (region 22), DENV1 (region 37), DENV2 (region 39), DENV3 (region 14), DENV4 (region 45), and ZIKV (region 47). Follows the His-tag Ab coupling microspheres. Specific biotinylated NS1 antigen was added at a concentration of 5 μg of antigen per 106 beads in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4) for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking at 700 rpm. Beads were then washed/blocked three times in blocking buffer (PBS + 1% BSA) and resuspended in wash buffer at 2x106 beads/mL.

2.12. EDIII and NS1 Multiplex Assay

DENV and ZIKV EDIII coupled beads were combined in equal ratios by plating 50 μL containing 2,500 beads per antigen into each well of a 96-well assay plate (Cat. No:655906). Rhesus macaque serum samples from 90 days p.i. were diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer. Mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for each EDIII antigen ZV-67 (ZIKV), E103 (DENV1), 3H5 (DENV2, 8A1 (DENV3), E88 (DENV4)) and NS1 antigen were titrated in each assay as controls for assay consistency across couplings, plates, and assay days. A magnetic plate separator was used to remove the blocking buffer from the assay plate, and 50 μL of diluted serum or mAb was added to the beads. The serum and bead mixture were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking at 700 rpm. Beads were washed twice with 200 μL blocking buffer per well using a magnetic separator. 50 μl of Goat anti-Human IgG Fc Multi-species SP ads-PE (Southern Biotech, catalog:2014-09) and Goat anti-Mouse IgG Fc Human ads-PE (Southern Biotech, catalog:1030-09) were added to the beads (6 μg/ml in block buffer) and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking at 700 rpm to detect respective antibody species. Beads were washed thrice with 200 μL blocking buffer per well using a magnetic separator and resuspended in 100 μL of blocking buffer before acquiring data. Fluorescence data was obtained using a Luminex 200 analyzer set to acquire at least 50 beads per bead region.

2.13. In Vitro ADE Assay in K562 Cells

The ability of serum antibodies from DENV2-immune animals to enhance ZIKV was assessed in K562 cells (ATCC CCL-243). Briefly, macaque serum from 90 days p.i. was diluted three-fold starting after an initial dilution of 1:25 and then incubated with the virus of interest at an approximate multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.0 for 1 hr at 37 °C. Monoclonal antibody 4G2 was used as a positive control at 0.5 mg/ml. Approximately 1x106cells were added to each well in a 96 well-plate containing the mixture of virus and serum. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 hrs, cells were washed with fresh media twice and incubated at 37 °C for 48 hrs. After incubation, cells were washed, fixed with 1% PFA, permeabilized with saponin and stained with a rabbit monoclonal 4G2 antibody at 4ug/ml. After incubating 1 hr at 4 °C, cells were washed and stained with a secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor-647 at 1:5000 for 1 hr at 4 °C. After washing, cells were resuspended in 200ul of PBS until ready to run on flow cytometer. Percent of infection was determined using an Attune NxT flow cytometer.

2.14. DENV Neutralization Assays

Focus Reduction Neutralization Test (FRNT) for all four DENV serotypes were completed for baseline and days 15, 30, 90 and 300 p.i.. Data on neutralization curves for baseline was not included as all animals showed no neutralizing potential and remained below threshold (below 60% reduction). The exact late convalescent timepoint was 320 days for the CD4-depleted group and 286 days for the undepleted group, but for normalization purposes, a reference timepoint of 300 days p.i. was used. Vero81 cells (ATCC CCL-81) were seeded at approx. 2.0 x 105 per well in 96 well-plates with DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for approx. 18 hours. Serum dilutions (ten-fold) were prepared in diluent medium Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) with 2% FBS (Gibco) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Hyclone). Virus was added to each dilution and incubated for 1 hour at 37ºC/5%. Before inoculation, the growth medium was removed, and cells were inoculated with 50 uL per well of serum-virus dilution in triplicates; plates were incubated for 1 hour at 37ºC/5%CO2/rocking. After incubation, 125 uL per well of overlay (Opti-MEM 1% carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma), 2% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (HyClone) was added to the plates containing virus dilutions, followed by an incubation period of 45-48 hours at 37ºC/5%CO2. After two days, overlay was removed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Plates were blocked with 5% non-fat dairy milk in 1X perm buffer (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm) for 10 min. and incubated for 1hr/37ºC/5%CO2/rocking with anti-E mAb 4G2 and anti-prM mAb 2H2 (kindly provided by Dr. Aravinda de Silva and Ralph Baric, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC, USA), both diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer. Plates were washed three times with PBS and incubated 1hr/37ºC/5%CO2/rocking with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma), diluted 1:1,500 in blocking buffer. Foci were developed with TrueBlue HRP substrate (KPL) and counted using an Elispot reader. Results were reported as FRNT with a 60% or greater reduction in DENV foci (FRNT60). A positive neutralization titer was designated as 1:20 or greater, while ˂1:20 was considered a negative neutralization titer.

2.15. ZIKV Neutralization Assays

For the Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT) for ZIKV, Vero81 cells (ATCC CCL-81) were seeded at approx. 2.0 x 105 per well in 24 well-plates with DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for approx. 18 hours. Serum dilutions (ten-fold) were prepared in a diluent medium (Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) with 2% FBS (Gibco) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Hyclone). Virus was added to each dilution and incubated for 1 hour at 37ºC/5%/CO2. Before inoculation, the growth medium was removed, and cells were inoculated with 100 uL per well of each dilution in triplicates; plates were incubated for 1 hour at 37ºC/5%CO2/rocking. After incubation, 1mL per well of overlay (Opti-MEM 1% carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma), 2% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (HyClone) was added to the plates containing virus dilutions, followed by an incubation period of 4 days at 37ºC/5% CO2. After four days of incubation at 37ºC/5%CO2, the overlay was removed; the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 80% methanol, and stained with crystal violet and foci were counted. The mean focus diameter was calculated from approx. twenty foci per clone were measured at 35 magnifications. Results were reported as the PRNT with a 60% or greater reduction in ZIKV or DENV plaques (PRNT60). A positive neutralization titer was designated as 1:20 or greater, while ˂ 1:20 was considered a negative neutralization titer.

2.16. BAFF ELISA

Determination of B-cell activating factor (BAFF) levels in sera was assessed using the Monkey BAFF ELISA commercial kit (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA). This Quantitative Sandwich ELISA kit uses coated anti-BAFF antibodies and a BAFF HRP-conjugate reagent technique for analyte detection. The assay was performed per the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.17. Serum Cytokines Assay

Detection of serum cytokines after primary DENV2 infection was measured using NHP XL Cytokine Luminex Performance Assay Kit (Bio-techne, R&D systems). The assays were performed per the manufacturer’s instructions. First, 50 μL of standard, control, or sample were mixed with 50 μL of diluted microparticle cocktail and added to each well. The mixture was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature on a shaker at 800 rpm. Three wash steps using 100 ul of wash buffer were performed. Then, 50 μL of diluted biotin-antibody cocktail was added to each well, covered and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature on a shaker at 800 rpm. The last step of washing was performed followed by a resuspension of the beads before reading within 90 minutes using a Luminex analyzer.

2.18. Use of AI

Artificial intelligence program (A.I.) ChatGTP (

https://chatgpt.com/) was used for grammar correction and syntax.

2.19. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For viral burden analysis, the log titers and levels of vRNA were analyzed by multiple unpaired t-tests and two-way ANOVA. The statistical significance between or within groups evaluated at different time points was determined using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Tukey’s, Sidak’s, or Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test) or unpaired t-test to compare the means. Significant multiplicity-adjusted p-values (*< 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001, ****< 0.0001) show statistically significant differences between groups (Tukey test) or time points within a group (Dunnett test).

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of CD4+ T Cell Depletion Treatment in Rhesus macaques

To determine if the depletion treatment was effective, the frequency of CD4

+ T cells was assessed by immunophenotyping via flow cytometry during pre-treatment (pre-TX), post-treatment (post-TX), and post-primary DENV2 infection. Before cell depletion, CD4

+ T cell frequency was similar in all animals, (mean= 61.9 +/-0 for Group 1, and mean= 63.3+/-0 for Group 2). By day 2 post-TX, frequency decreased rapidly, resulting in a depletion of 99.8% (

Figure S1A). This reduction was consistent until day 7 p.i., when they began to slowly recover. Additionally, the absence of CD4+ T cells in depleted animals promoted an increase in CD8+ T cell frequency (

Figure S1B). Since we observed this increase in CD8+ T cells frequency, we wanted to assess their integrity. Consequently, we measured CD8+ effector functionality and observed no differences between groups (

Figure S1C and D). This suggests that CD4+ T cell depletion did not promote a dysfunctional CD8+ T cell response.

The gating strategy for T cells can be found in Supplementary Figure S2 (Figure S2).

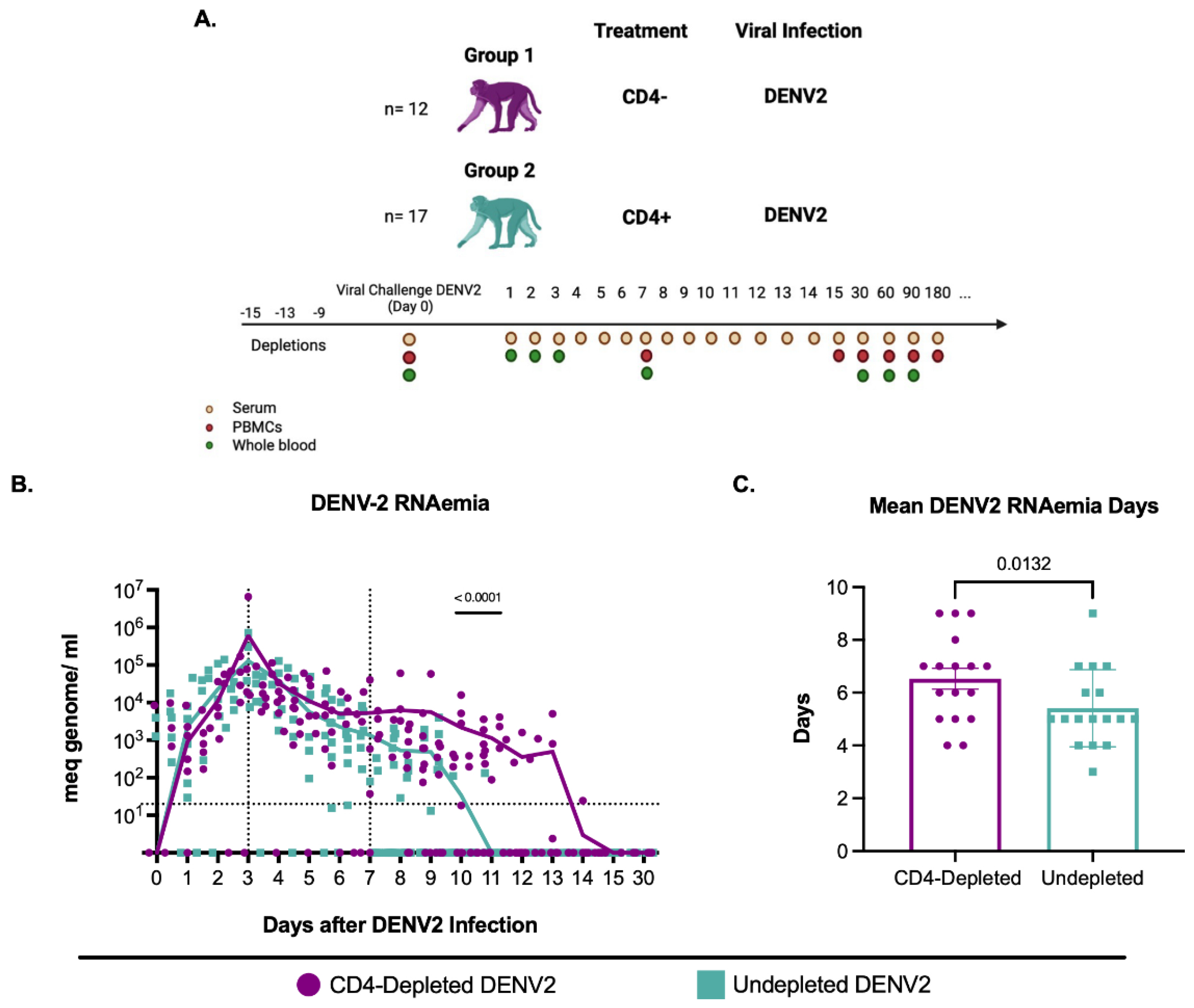

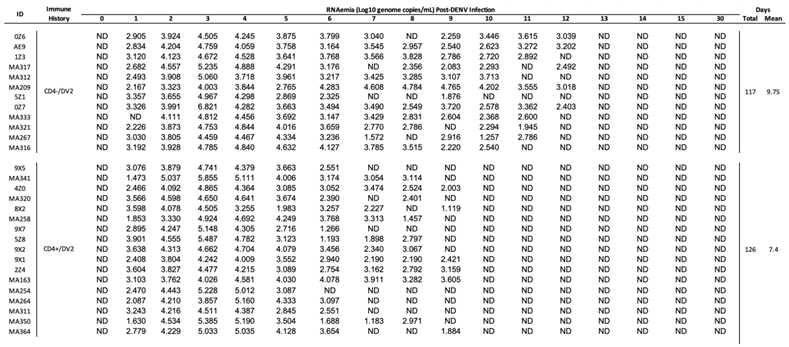

3.2. CD4+ T Cell Depletion Impairs DENV2 Viral Clearance in Flavivirus-Naïve Macaques

To determine if CD4

+ T cell depletion enhances or reduces DENV2 replication, DENV2 RNAemia was measured in serum during the first 15 days and day 30 after DENV2 infection (

Figure 1A). RNAemia was defined as follows: early from days 1 to 3 p.i., mid from days 4 to 7 p.i., and late from day 7 p.i. onwards. During the early period, viral RNA detection increased similarly in all groups (

Figure 1B). By day 5 p.i., the control group showed a progressive and continued decrease in viremia leading to resolution by day 10 p.i., with only one animal showing viremia on day 11 p.i.. However, the CD4-depleted group still had unusually high detectable DENV2 RNAemia levels after day 10 p.i.. This difference was statistically significant on days 10 and 11 p.i. (p= 0.000078 and p= 0.001346, respectively). By day 12 p.i. there was no viral RNA

detection in any animal from the control group, and by day 15 p.i. all animals tested negative for DENV2 (

Figure 1B and

Table S1). The results indicate a faster RNAemia resolution in the CD4 + T cell competent group compared to CD4-depleted animals and a delay in viral clearance in animals that are CD4-deficient.

Next, we evaluated the average RNAemia days, defined as the days with detectable viremia divided by the number of animals per group (

Figure 1C). The undepleted animals had significantly fewer mean RNAemia days compared to the depleted animals (p= 0.0132). Taken together, these results suggest that CD4

+ T cells have a role in controlling DENV2 RNAemia, yet it remains undetermined if this is due to a direct T cell activity, an interaction with B cells or a combination of both activities.

DENV2 RNA detection during the first 15 days and day 30 p.i. Mean viremia days per group was calculated using days with detectable RNAemia divided by the number of animals in each group. ND= viral RNA not detected.

3.3. CD4+ T Cell Depletion Is Associated to Increased Monocytosis

To determine any effects of DENV viral infection on NHPs a range of clinical parameters and complete blood counts were monitored before and after DENV2 infection (

Figure S3). Interestingly, we observed a significantly higher percentage of monocytes in the CD4- depleted group compared to the undepleted group at days 10 and 15p.i. (p= 0.0003, p< 0.0001, respectively) (

Figure S3C). Taken together with our viremia data, these results suggest that such presence of monocytes is related to both higher viral loads and a higher inflammatory response in the CD4- depleted group.

3.4. CD4+ T Cell Depletion Results in Higher Detection of DENV NS1 Protein

To independently confirm viremia and to explore the role of CD4

+ T cells in NS1 antigenemia, we measured DENV NS1 levels in serum. NS1 has been shown to correlate with virus replication and the level of viremia in infected individuals [

41,

42]. In CD4-depleted and control animals we measured NS1 levels in serum at days 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, and 30 post-DENV2 infection (

Figure S4). We observed a similar increase in serum NS1 levels over the first 7 days p.1. Between days 10 and 15 p.i. NS1 levels in the control group declined, whereas levels in the CD4-depleted group continued to increase and peaked by day 15 p.i. This suggests that the lack of CD4

+ T cells enhances DENV2 replication and NS1 levels in circulation, further confirming a role for CD4

+ T cells in viral clearance during a primary infection.

3.5. Lack of CD4+ T Cells Constrains Anti-DENV2 Antibody Induction

To assess the impact of CD4+ T cell depletion on Ab responses to primary DENV2 infection, we measured virus-specific IgM and IgG levels after infection (

Figure S5). The induction of virus-specific IgM was delayed and lower in magnitude in CD4-depleted animals compared to control animals at days 10 and 15 p.i. (p< 0.0001) (

Figure S5A). Furthermore, total anti-DENV IgM produced from day 0 to day 15 p.i. was also significantly lower in the CD4-depleted group in comparison to the control group (p= 0.0007) (

Figure S5B). While anti-DENV IgG levels were statistically different between both groups only on day 15 p.i., where it appears that the CD4-depleted group was slower, by ~45 days to generate as robust an IgG response compared to the control group (p< 0.0001) (

Figure S6C). Similar results were observed with the total anti-DENV IgG produced (from day 0 to day 60), where CD4-depleted animals had significantly lower IgG values compared to undepleted animals (p= 0.0153) (

Figure S5D). Virus-specific IgG levels were comparable in both groups at convalescence (days 60 and 90 p.i.). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CD4+ T cell depletion causes a delay in activated B cells ability to produce antigen specific antibodies during primary DENV2 infection.

3.6. DENV Anti-NS1 Abs Are Modified by a Lack of CD4+ T Cells

Next, we compared anti-DENV NS1 IgG levels in both groups at days 15, 30, and 90 p.i. (

Figure S6). No DENV NS1 anti-IgG antibodies were detected on day 0 as expected. By day 15 p.i., CD4-depleted animals had significantly lower levels in comparison to the undepleted animals, similar to anti-DENV IgG levels previously presented (p= 0.000208). By day 30 p.i., both groups had reached similar anti-NS1 IgG levels. Interestingly, by day 90 p.i. CD4-depleted animals showed significantly higher anti-NS1 IgG levels compared to undepleted animals (p= 0.000208) and surprisingly, the Abs were still detected only in that group one year after DENV2 infection (p<0.0001). These results demonstrate an initial delay in the development of NS1 binding IgG in the CD4-depleted group followed by an increase NS1Ab levels at late convalescence compared to the control group.

Altogether, this result supports an initial delay in Ab switch in this group as seen in the total IgG Abs response followed by an expansion of anti-NS1 antibodies by day 90 p.i. which is sustained at least one year p.i. but only in the absence of CD4+ T cells. This fact strongly suggests the development of a population of cross-reacting non-specific anti-NS1 Abs in the late convalescent period associated with a blunted priming of B cells.

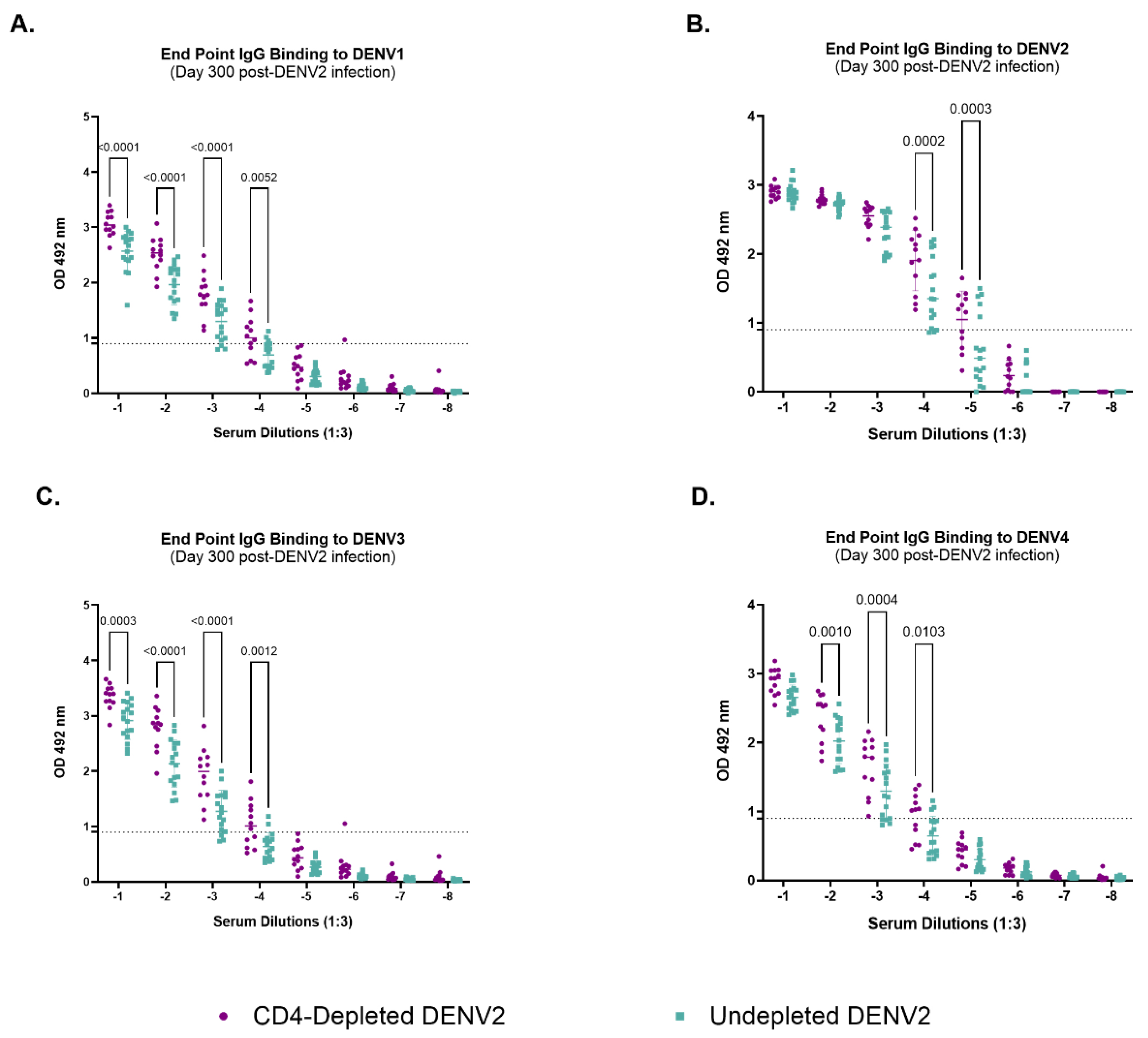

3.7. Depletion of CD4+ T Cells Modifies IgG-Binding Capacities of Antibodies Against Heterologous Dengue After Primary DENV2 Infection

To further explore the role of CD4

+ T cells, we assessed their impact on the quantity and quality of the humoral response against all four DENV serotypes and ZIKV 300 days after DENV2 infection using the endpoint dilution approach (

Figure 2 and SFig. 7). No binding activity against ZIKV was observed (SFig. 7). On the other hand, the CD4-depleted group showed significantly higher levels of IgG binding capabilities across serum dilutions against DENV1 (

Figure 2A) (p<0.0001, p<0.0001, p<0.0001 and p= 0.0052) DENV2 (

Figure 2B) (p=0002 and p=0.0003), DENV3 (

Figure 2C) (p= 0.0003, p< 0.0001, p<0.0001 and p= 0.0012) and DENV4 (

Figure 2D) (p= 0.0010, p= 0.0004 and 0.0103) when compared to the undepleted animals. However, these antibodies seem to be of high-neutralizing capacity only against DENV2 and DENV4, as seen in our neutralization data on days 90 and 300 p.i.. Binding activity was similar at lower serum dilutions between the control and depleted group for DENV2 (10

-1-10

-3) and for DENV4 (10

-1). However, binding activity against DENV1 and 3 was significantly higher in the depleted group at all serum dilutions. This noteworthy finding strongly suggests that CD4

+ T cells differentially impact the antibodies repertoire, at functional level, against the autologous vs. heterologous serotypes. Together, these results suggest a significant role of CD4

+ T cells shaping humoral immune responses, particularly the antibody generation during a primary DENV2 infection.

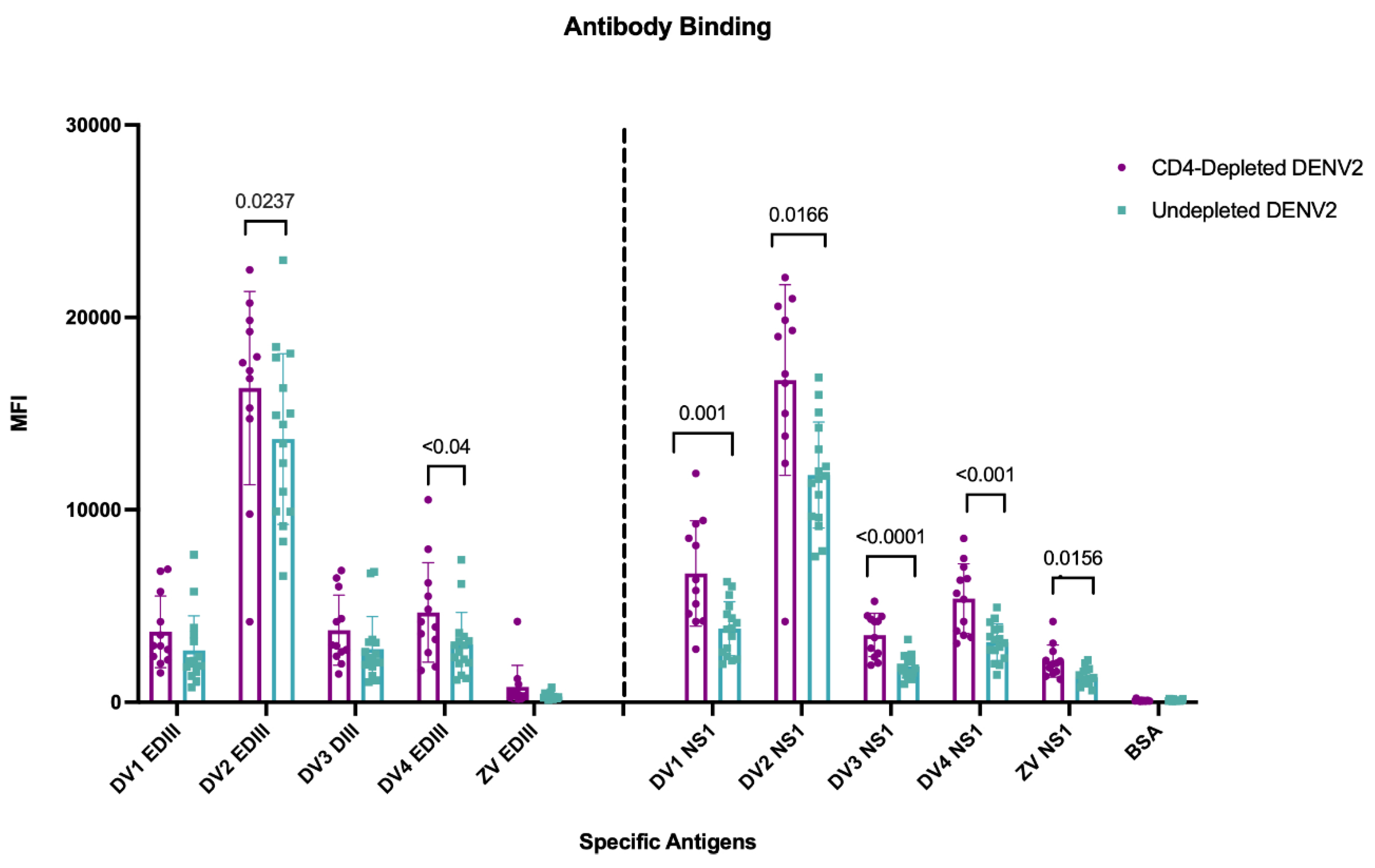

3.8. Lack of CD4+ T Cells During a Primary DENV2 Infection Reshapes Abs Binding to the Envelope EDIII Domain and to the NS1 Protein

To further explore the role of CD4

+ T cells in shaping the antibody response against DENV and cross-reactivity to ZIKV, domain specificity against EDIII and NS1 was quantified using a Luminex assay. The envelope (ENV) EDIII domain was selected as a major neutralizing target and NS1 due to its proposed role in pathogenesis [

43,

44]. Type-specific and cross-reactive responses were measured at day 90 p.i. after DENV2 infection against EDIII and NS1 antigens from all four DENV serotypes and ZIKV (

Figure 3). When analyzing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after the primary DENV2 infection, both groups of animals had significantly higher responses against EDIII to the infecting serotype DENV2 compared to the other DENV serotypes and ZIKV EDIII. However, the depleted group showed significantly higher MFI values against DENV2 (p= 0.0237) and an extended breadth of binding to DENV4 EDIII region (p <0.04), while a limited cross-reactivity against EDIII to the other DENV serotypes was observed, without differences between groups, and virtually no reactivity to ZIKV EDIII (

Figure 3). In contrast to the response to the EDIII domain, a greater breadth of NS1 Ab repertoire was present in connection with the lack of CD4

+ T cells. Antibodies against DENV2 NS1 were significantly higher in both the depleted and undepleted groups compared to the NS1 from the other DENV serotypes. However, MFI values were significantly higher against all DENV NS1 serotypes in the depleted group (DENV1, p< 0.0011; DENV2, p< 0.0166; DENV3, p< 0.0003; DENV4, p< 0.0022). Interestingly, there was a limited but detectable cross-reactivity against the ZIKV NS1 protein in both groups with a significantly higher cross-reactivity in the CD4-depleted group (p <0.0156) (

Figure 3). This suggests that during a primary DENV infection, CD4

+ T cells have a different weight/effect in guiding the Ab responses against the EDIII domain and NS1 protein, potentially through differential support of Tfh populations [

45] or through differential recognition of the envelope protein versus NS1 by CD4 T cells [

46].

3.9. Cross-Reactivity Is Increased by Lack of CD4 T Cells

To confirm the Luminex assay results that depletion of CD4+ T cells altered the relative levels of DENV2 TS and flavivirus CR Abs, we measured anti-NS1 ZIKV IgG levels with a different assay and at different timepoints after infection. As shown in

Supplementary Figure S8 (

Figure S8), anti-ZIKV IgG develops in the convalescent phase at day 30 p.i. and continues to increase in both groups by days 60 and 90 p.i. and were still detectable one year (365 days p.i) later. Interestingly, the levels of those CR Abs were significantly higher on days 90 and 365 p.i. in the group lacking CD4

+ T cells (p< 0.0001). This result, together with the ZIKV end point binding result (

Figure S7), suggests an increased expansion of flavivirus-CR B cell clones in animals without CD4

+ T cells during the primary DENV infection.

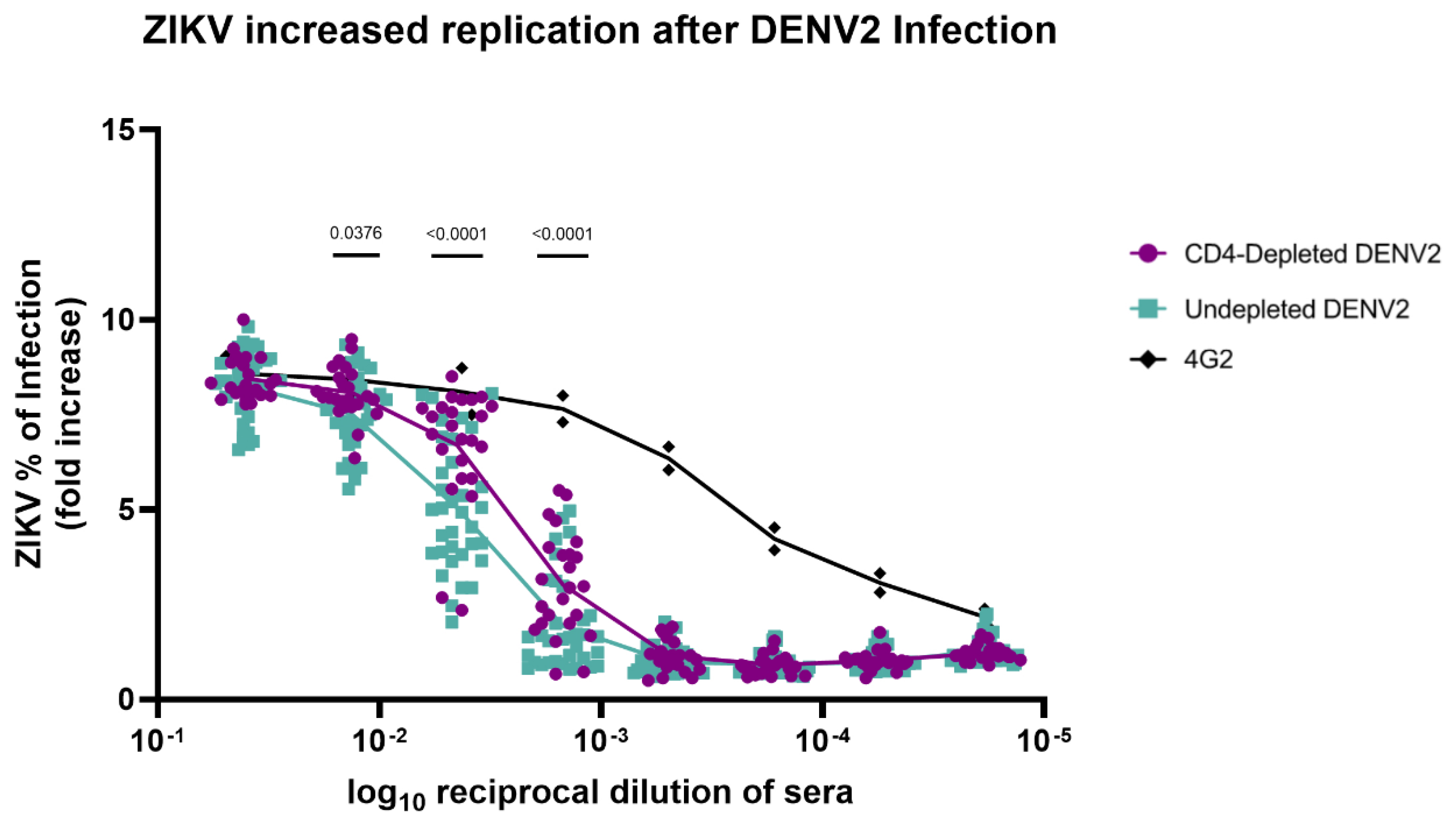

3.10. Absence of CD4+ T Cells Modifies Antibody Repertoire Properties Increasing ZIKV Replication

An

in vitro ADE assay with K562 cells was performed to measure ZIKV infection-enhancing antibodies in DENV2-immune macaque serum from 90 days p.i.. Sera from both CD4-depleted and undepleted animals exhibited similar ZIKV infection activity at the lowest serum dilution, ranging from 40 to 50% (

Figure 4). However, ZIKV replication significantly increased across higher serum dilutions (particularly 1:100, 1:1000, and 1:10000) in CD4-depleted animals in comparison with the undepleted control group (p= 0.0376, p< 0.0001 and p< 0.0001, respectively). This denotes that a lack of CD4

+ T cells has an effect on the Ab repertoire that leads to an increase in ZIKV infection compared to undepleted animals and to previously reported naïve animals [

36].

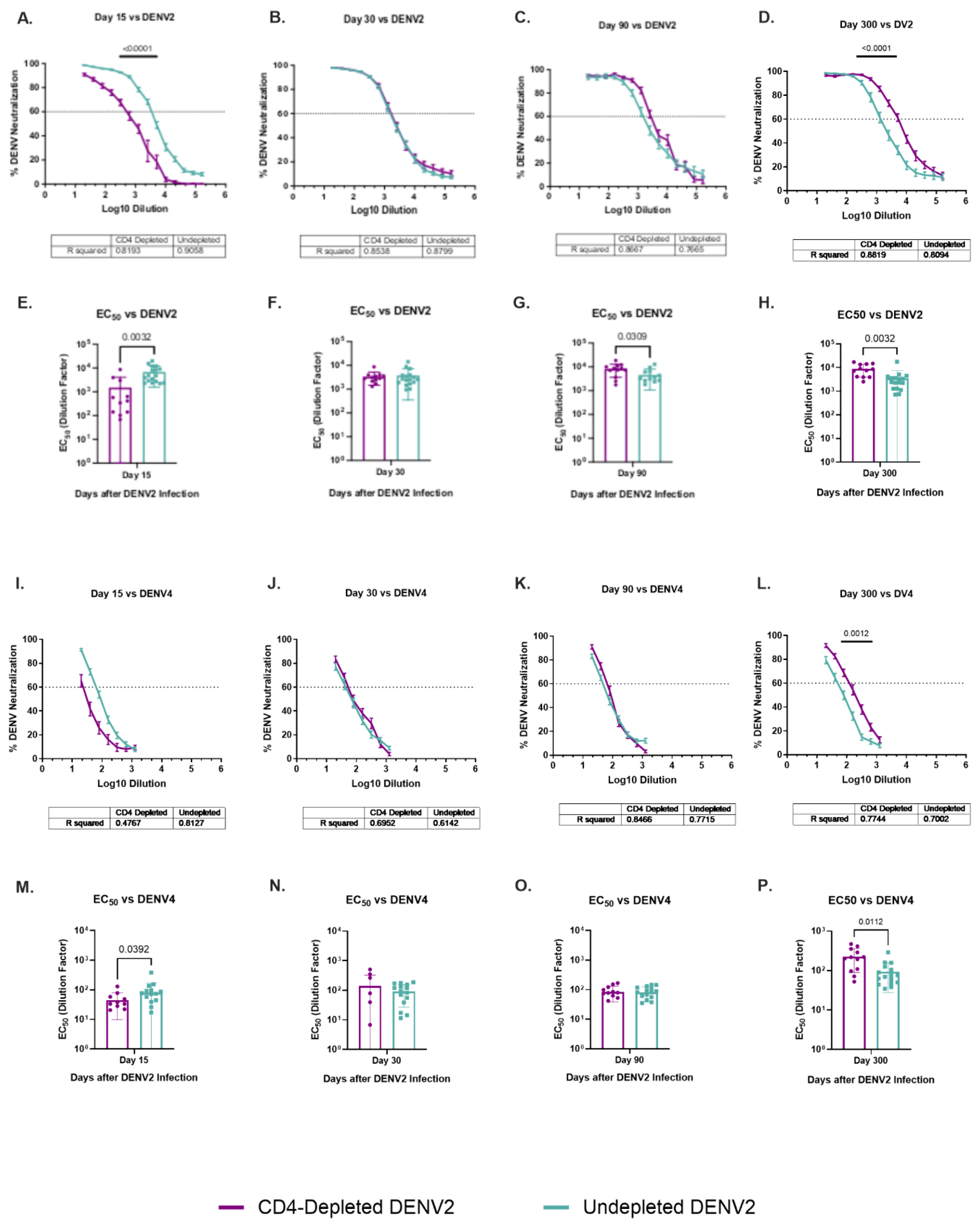

3.11. Dynamic of Specific DENV2 and Heterologous DENV4 Neutralizations Are Modulated by a Lack of CD4+ T Cells

To determine the contribution of CD4

+ T cells to the development and maintenance of the neutralization antibodies (NAbs) response, all animals were tested using plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) and focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT) assays against ZIKV and all DENV serotypes, respectively (

Figure 5 and

Figure S9). Neutralization assays were completed for baseline (data not shown) and days 15, 30, 90 and 300 p.i.. As expected, no animals had NAbs against any flavivirus at baseline. No trends or significant differences were identified in the cross-neutralization at any tested time point against the DENV1 and DENV3 serotypes (

Figure S9), and no neutralization of ZIKV was observed at any timepoint (

Figure S9).

However, both groups developed neutralizing activity against the infecting serotype DENV2 and the heterologous serotype 4 (

Figure 5). Undepleted animals had significantly higher neutralization levels against DENV2 by day 15 p.i. (p< 0.0001) in comparison to the depleted animals (

Figure 5A). On later timepoints, neutralization was similar between groups. However, by day 300 p.i., a shift is observed where CD4-depleted animals have significantly higher neutralization levels than the undepleted animals (p< 0.0001) (

Figure 5D). A similar effect is observed in the neutralization against DENV4, where undepleted animals have higher levels on day 15 p.i. (

Figure 5I) (although not reaching statistical significance) but by day 300 p.i. CD4-depleted animals have significantly higher levels than undepleted animals (p= 0.0012) (

Figure 5L).

The 50% effective concentration (EC50) of neutralizing Abs is also shown. By day 15 p.i., a significantly lower neutralizing activity is observed in CD4-depleted animals in comparison to the undepleted group, not only against DENV2 (p= 0.0032) but against DENV4 (p= 0.0392) as well (

Figure 5E and

Figure 5M). This finding is interesting because DENV4 was the only heterologous serotype showing cross-reactivity against EDIII domain in previously discussed results, suggesting that Abs against DENV4 EDIII are indeed cross-reactive but non-neutralizing at early time points and the response evolves to include antibody neutralization. However, CD4-depletion was associated with a significantly higher EC50 against DENV2 compared to the undepleted group at day 90 p.i. (p= 0.0309) and against both DENV2 and DENV4 after one year of ZIKV infection (p= 0.0032 and p= 0.0112, respectively) (

Figure 5G, 5H and 5P). This data is of great interest as it suggests a possible delayed neutralizing response against homologous DENV2 in animals lacking DENV2-primed CD4

+ T cells which was extended to a heterologous serotype (DENV4).

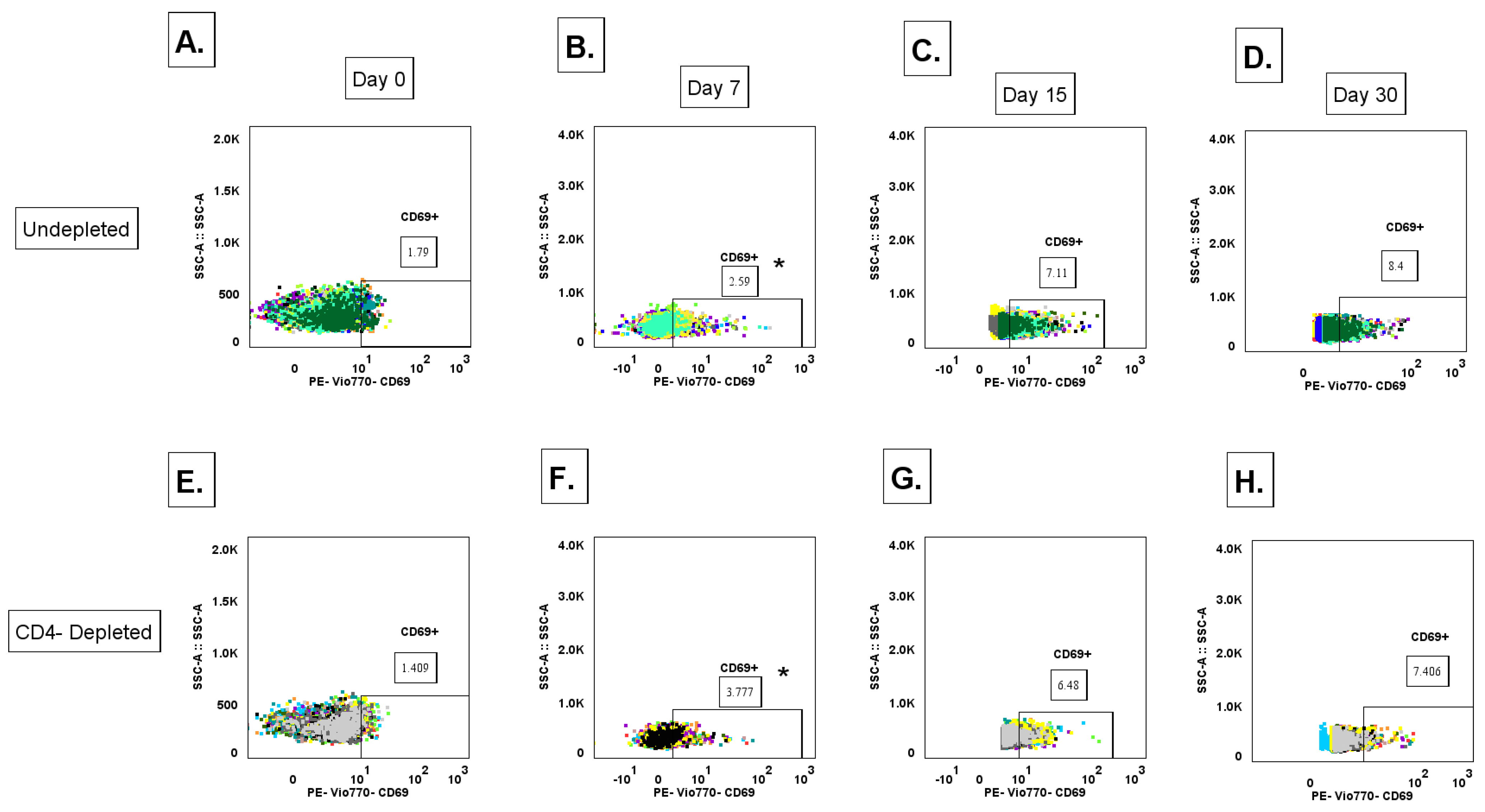

3.12. Lack of CD4+ T Cell Priming Promotes Increased IgG+ MBC Polyclonal Activation During a Primary DENV2 Infection

To determine the contribution of CD4

+ T cells in modulating the activation of an unclass-switched memory B cell (defined as IgM+ B cells CD3-CD20+CD27-) [

47], response to a primary DENV2 infection, whole blood for immunostaining was collected on days 0 (baseline), 7, 15, and 30 p.i. with DENV2, where cell population levels were measured via flow cytometry. The gating strategy is shown in

Supplementary Figure S10 (

Figure S10). While we did not observe significant quantitative differences in unclass-switched memory B cells between the CD4-depleted and undepleted groups in any timepoint post-infection, a trend is observed where the undepleted group shows higher levels of unclass-switched memory B cell subset, compared to the CD4-depleted cohort (

Figure S11A). Another B cell subtype we assessed was activated unclass-switched memory B cells (IgM+-MBC, defined as CD3-CD20+CD27-CD69+) (

Figure S11B). Here, we observed that the CD4-depleted group showed a significant early expansion of the activated unclass-switched memory B cell frequency on day 7 p.i. compared to baseline (p= 0.00332). However, both groups showed an increase in frequency compared to baseline in the subsequent measured time points. Taken together, this data suggests that activation pathways of unclass-switched memory B cell clones during a primary DENV2 infection can follow both T cell-dependent or T cell-independent pathways.

To determine the contribution of CD4

+ T cells in modulating the formation and activation of IgG

+ memory B cell (IgG

+ MBC) (CD3-CD20+CD27+sIgG+) populations during a primary DENV2 infection, we measured expression levels of surface IgG in total MBCs via flow cytometry. Total IgG

+ MBC levels were surveyed, and no significant differences were observed in any of the time points measured nor between both groups post-infection (

Figure S11C). However, when measuring activated IgG

+ MBCs (CD3-CD20+CD27+sIgG+CD69+), we observed a significant early expansion of these cell types in the CD4-depleted group at day 7 p.i., compared to baseline levels (p= 0.0450) (

Figure 6 and

Figure S11D). Interestingly, at day 7 p.i. the CD4-depleted group showed significantly higher levels of activated IgG

+ MBCs compared to the undepleted control (p= 0.0454). This expansion in the CD4-depleted cohort continued to significantly increase at day 15 p.i., compared to day 7 p.i. (p= 0.0100). In the case of the undepleted control group, a significant expansion was observed in day 15 compared to baseline levels (day 0 and day 15 p< 0.0001). By Day 15 and 30 p.i. activated IgG

+ MBC levels reach similar frequencies between both groups, yet a strong trend is observed where the undepleted control cohort shows higher levels of activated IgG

+ MBCs. This data suggests that a lack of CD4

+ T cell priming promotes an early expansion of a polyclonal (most likely less affinity matured) IgG

+ MBC response that can be correlated to the lower specific IgG anti-DENV2 and neutralizing response. In addition, the early significant polyclonal expansion associated to a limited priming by CD4

+ T cells also relates to an increased binding breadth to DENV4 EDIII domain and to the NS1 protein, as well as cross-reactivity to ZIKV in the convalescent period in the CD4-depleted cohort, as previously shown.

3.13. CD4 T Cell Depletion Before DENV2 Infection Results in a Delay of Cytokine Profiles in Rhesus macaques

We measured B cell activation factor (BAFF) levels on days 0, 7 and 10 post DENV2 infection (

Figure S12). No differences between groups were observed. Serum cytokines were measured via Luminex assay pipeline using samples collected from days 0, 3 and 7 post DENV2 infection for all CD4-depleted and undepleted animals. Among the eleven measured cytokines, only three (IFN-alpha, BCA-1 and IP-10) had statistically significant differences (

Figure S13). There were no significant differences between groups in any of the timepoints measured for IFN-alpha. By day 7, all animals had a significant increase of IFN-alpha when compared to day 0 and day 3 (CD4-depleted p=0.0129 and undepleted p=0.0023). Even though both groups show an increase in IFN alpha over time, undepleted animals produced more of this cytokine than the CD4-depleted group. This suggests that the lack of CD4 T cells may result in a delay of IFN alpha production (

Figure S13A).

When analyzing BCA-1 (CXCL13), there were no statistically significant differences between groups in days 0 and 3. However, by day 7 CD4-depleted animals had significantly lower levels of BCA-1 than the undepleted group (p= 0.0312). Also, in the undepleted animals, BCA-1 levels significantly increased by day 7 in compared to day 0 (p=0.0234) (

Figure S13B).

When comparing IP-10 (CXCL10) levels, there were no significant differences between groups in any timepoint. However, CD4-depleted animals had significantly higher levels of IP-10 by day 3 (p= 0.0240), which eventually increased more by day 7 (p< 0.0001) compared to their baseline levels. On the other hand, undepleted animals had significantly higher values of IP-10 at day 7 in comparison with their baseline levels (p= 0.0372). Surprisingly, although not statistically significant, the CD4-depleted group had higher levels of IP-10 in serum in comparison with the undepleted group by days 3 and 7 post DENV2 infection (

Figure S13C). These results support the higher viral replication observed in the CD4-depleted animals, which in turn may suggest a higher production of IP-10 by monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs).

Interestingly, although no significant differences were observed, CD4-depleted animals had undetectable IFN-gamma levels in all three timepoints measured in comparison to the undepleted group, that had approximately half of the animals producing detectible levels of IFN-gamma. This implies that CD4 T cells may play a role inducing the production of IFN-gamma for viral clearance.

Overall, we observed an expected cytokine profile response in all individuals, with cytokine levels showing a trend to increase after days 3 and 7 post DENV2 infection compared to their baseline levels. In summary, CD4-depleted animals demonstrate a delayed response in almost all the cytokines measured compared to the undepleted animals (except for IFN-gamma profiles). Taking this into consideration, in general our results suggest that CD4 T cells may play a role in the induction of several cytokines and the activation of other immune cells necessary for viral clearance.

4. Discussion

Despite decades of research, dengue virus (DENV) pathogenesis remains incompletely understood. A balanced interaction between humoral and T cell responses is known to be crucial for protection. The role of CD4+ T cells in this balance has been revisited in recent years, shifting from an early focus on pathogenic [48-52] contributions to a more nuanced appreciation of their protective functions [

53,

54] . Recent studies underscore their importance in viral clearance, B cell priming, and modulation of antibody quality and specificity [

49,

50,

55].

Our findings, derived from a rhesus macaque model of primary DENV2 infection, demonstrate that CD4+ T cells play a central role in shaping the early immune response. CD4+ T cell-depleted animals exhibited prolonged viremia, elevated NS1 antigenemia, delayed class switching, and increased frequencies of cross-reactive but weakly neutralizing antibodies. These data support a model in which CD4+ T cells are critical for efficient viral clearance and for promoting an antibody repertoire with greater neutralization capacity and reduced potential for antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

Notably, CD4+ T cell-depleted macaques developed an altered humoral landscape characterized by early polyclonal activation of naïve and memory B cell compartments, diminished virus-specific IgM and IgG responses at early time points, and a delayed emergence of neutralizing antibodies against DENV2 and DENV4. These functional deficits were mirrored by elevated levels of anti-NS1 IgG, which persisted one-year post-infection. Collectively, these findings point to a pivotal role for CD4+ T cells in supporting germinal center (GC) formation, affinity maturation, and durable, high-quality antibody production during primary DENV infection.

Interestingly, our observations in non-human primates differ from some murine studies. Yauch et al. (2010) reported that CD4+ T cell depletion did not impair early DENV-specific IgG or IgM titers or neutralization capacity in mice. However, other murine studies have affirmed the protective role of CD4+ T cells in both vaccine-induced and natural infections, showing that depletion of these cells can abrogate vaccine-mediated protection and increase morbidity [56-58]. These discrepancies may reflect species-specific differences in immune architecture or the relative robustness of T cell-independent antibody responses in mice compared to primates.

Our findings align more closely with human data. For instance, children protected from symptomatic dengue have been shown to generate more robust anti-envelope (ENV) and anti-NS1 IgG with greater Fc effector function than symptomatic individuals [

59]. Additionally, higher pre-infection anti-NS1 antibody levels have been associated with asymptomatic infection [

60], underscoring the potential of NS1-specific immunity in modulating disease outcome. Given recent efforts to include NS1 antigens in vaccine formulations, our findings suggest that NS1-specific responses may be qualitatively altered in the absence of CD4

+ help, potentially influencing durability and specificity. Notably, our study highlights enhanced cross-reactivity to ZIKV NS1 in CD4+ T cell-depleted macaques—a finding rarely observed in primary DENV infection of flavivirus-naïve humans .. This is supported by the presence of an antibody repertoire in depleted animals with increased binding to heterologous serotypes, particularly DENV1 and 3, but with limited or absent neutralizing activity, resembling the same type of Abs inducing ADE [

15,

61,

62]. This suggests that CD4+ T cells may restrict the breadth of B cell responses to favor type-specific rather than broadly cross-reactive targets with limited functionality and underscore the role of those cells averting ADE.

Overall for all four serotypes of DENV animals that lacked CD4 T cells had higher levels of binding antibodies than control animals in the linear portion of the curve.

This noteworthy finding strongly suggests that CD4

+ T cells impact the antibodies repertoire, against both autologous and heterologous serotypes. However, the extension of the impact may be serotype-related as the Abs properties are different for DENV1 and 3 compared to the autologous infecting DENV2 and the heterologous DENV4. While early neutralizing activity was significantly lower in the depleted animals, by day 300 post-infection, neutralization against DENV2 and DENV4 surpassed that of controls. The differences in the Abs properties depending on the DENV serotype have been well-documented for sequential DENV-DENV infections [

63,

64]and more recently for DENV-ZIKV or ZIKV-DENV infections [

65,

66]. Mechanistically, we propose that the ratio of germinal center versus extrafollicular B cells is altered in the context of CD4

+ T cell depleted DENV infected animals, leading to increased long-term neutralizing antibody responses, reviewed in [

67]. This is evidenced by the early expansion of activated IgG

+ memory B cells and unclass-switched memory B cells in the CD4-depleted group—an expansion likely driven by T cell-independent activation pathways, possibly mediated through innate immune signals, such as BAFF or pattern recognition receptor (PRR) signaling. Similar polyclonal B cell activation has been described in both HIV and DENV infections and has been linked to poor antibody quality and affinity maturation [68-71]. Furthermore, from our results we postulate that the properties and functionality of that increased long-term neutralizing antibody responses, in the absence or limited priming of CD4

+ T cells, may be different depending on the antigenic uniqueness of each DENV serotype.

Although cytokine analysis did not reveal dramatic group differences, a delayed interferon-alpha (IFN-α) and BCA-1 (CXCL13) response in CD4-depleted animals suggests a slower or impaired recruitment of immune cells necessary for GC responses. Interestingly, IP-10 (CXCL10), typically associated with monocyte and dendritic cell activation, was elevated in the CD4-depleted group, possibly reflecting compensatory innate activation in the face of uncontrolled viral replication.

A particularly novel observation was the delayed, but ultimately more effective, neutralizing antibody response in CD4-depleted animals at one-year post-infection. This raises the possibility that delayed GC responses or T cell reconstitution over time may allow for eventual affinity maturation and functional antibody development. Similar kinetics have been observed in CD4-depleted murine models’ post-vaccination [

72].

These findings offer new insights into vaccine design. Most current DENV vaccines aim to elicit balanced neutralizing responses to all four serotypes. However, vaccine-induced antibodies often target cross-reactive, non-neutralizing epitopes, increasing the risk for ADE. Our data suggest that robust CD4+ T cell help—most likely from Tfh cells targeting ENV and NS1—may skew the response toward protective, type-specific neutralizing antibodies while avoiding the generation of broad but potentially pathogenic cross-reactivity. The imbalance of replication among serotype components, as observed in Dengvaxia and TAK-003 vaccines may limit CD4+ T cell help for some serotypes, compromising protection and increasing risk during secondary dengue infections.

Importantly, this study highlights the translational value of the rhesus macaque model in flavivirus research. The immune architecture and GC biology of NHPs more closely mirror that of humans than murine models, offering unique insights into B cell priming, memory formation, and antibody evolution in vivo.

5. Conclusions

Altogether, our findings reinforce the central role of CD4+ T cells in promoting timely, high-quality, type-specific antibody responses during primary DENV infection. Their absence leads to delayed class switching, polyclonal memory B cell activation, enhanced antibody cross-reactivity—particularly to NS1—and increased potential for ADE. These observations have direct implications for dengue and ZIKV vaccine development. Future vaccine strategies must incorporate CD4+ T cell epitopes—particularly from NS1 and envelope proteins—and ensure their effective presentation to drive protective humoral immunity. Moreover, vaccine-induced memory should aim to mimic the protective imprinting observed in natural infection with intact CD4+ T cell support, to mitigate the risk of cross-reactive pathology upon secondary flavivirus exposure. Our results strength the complexity of the immunology interactions among DENV-serotypes.

6. Limitations

While this study provides mechanistic insights into the role of CD4+ T cells during primary DENV2 infection, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, rhesus macaques, though immunologically similar to humans, do not fully recapitulate the clinical spectrum of dengue disease, which is typically mild or subclinical in non-human primates. Second, while we observed significant alterations in the humoral response due to CD4+ T cell depletion, the specific clonality, affinity, and functional profiles of the resulting antibody repertoires were not assessed at the single-cell or BCR sequence level. Third, peripheral T follicular helper (Tfh) cells were not directly characterized, limiting our ability to dissect the cellular mechanisms underlying altered B cell help. Finally, although cytokine analyses revealed delayed immune activation in CD4-depleted animals, the scope was limited to a predefined panel, and broader immune profiling could uncover additional pathways affected by CD4+ T cell loss. Future studies incorporating single-cell immunoprofiling and in-depth Tfh analysis will be essential to fully elucidate the cellular interactions governing flavivirus immunity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

C.A.S., A.M.d.S, C.S.-C., A.M.-S., and L.C. developed the experimental design. C.R., M.I.M., and A.G.B. supervised and performed sample collection and animal monitoring. C.S.-C., A.M.-S., L.C., S.H. J.S-B., L.C.-R., and L.A. performed the experiments and an-alyzed the results. C.A.S., C.S.-C, A.M.-S. and L.C drafted the article. C.A.S., C.S.-C., A.M.-S, L.C., S.H., J.S-B., L.A., T.A., M.I.M., C.R., A.G.B., M.R.-B., J.B., A.P., L.C.-R., and A.M.d.S. reviewed and corrected the last version.

Funding

This work was funded by NIH 5R01AI 148264-05 to C.A.S. 2 P40 OD012217-38 and 2U42OD021458-23 to C.A.S. & M.L., and partially by 5-U24-AI152170-04 to A.M.d.S., and NIGMS- RISE program (R25GM061838) of UPR- Medical Sciences Campus to A.M.S.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and it Supporting Information files.

Acknowledgments

This work would have not been possible without the dedication and commitment of the Caribbean Primate Research Center and the Animal Resources Center staff. We thank Dr. Daniela Weiskopf for her valuable comments, Dr. Stephanie Dorta for her guidance in cell phenotyping, and Dr. Espino for her support with the correlation analysis. The authors also recognize the excellent technical support provided by Dr. Nicole Marzán and Rafael Ocasio.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Tian, N.; Zheng, J.X.; Guo, Z.Y.; Li, L.H.; Xia, S.; Lv, S.; Zhou, X.N. Dengue incidence trends and its burden in major endemic regions from 1990 to 2019. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.M.; Adams, L.E.; Durbin, A.P.; Muñoz-Jordán, J.L.; Poehling, K.A.; Sánchez-González, L.M.; Volkman, H.R.; Paz-Bailey, G. Dengue: A growing problem with new interventions. Pediatrics 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Johnson, B.A.; Xia, H.; Ku, Z.; Schindewolf, C.; Widen, S.G.; An, Z.; Weaver, S.C.; Menachery, V.D. , et al. Delta spike p681r mutation enhances sars-cov-2 fitness over alpha variant. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Paixao, E.S.; Cardim, L.L.; Costa, M.C.N.; Brickley, E.B.; de Carvalho-Sauer, R.C.O.; Carmo, E.H.; Andrade, R.F.S.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Veiga, R.V.; Costa, L.C. , et al. Mortality from congenital zika syndrome - nationwide cohort study in brazil. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Martelli, C.M.T.; Raja, A.I.; Sanchez Clemente, N.; de Araùjo, T.V.B.; Ximenes, R.A.A.; Miranda-Filho, D.B.; Ramond, A.; Brickley, E.B. Epidemic preparedness: Prenatal zika virus screening during the next epidemic. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Sankoh, O. , et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013, 496, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, T.R. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. American Journal of Public Health 2014, 104, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsulie, O.C.; Idris, I. Global re-emergence of dengue fever: The need for a rapid response and surveillance. The Microbe 2024, 4, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Nealon, J. Dengue in a changing climate. Environmental Research 2016, 151, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, M.G.; Alvarez, M.; Halstead, S.B. Secondary infection as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: An historical perspective and role of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. Archives of virology 2013, 158, 1445–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, S. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Advances in Viruses Research 2003, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, S.B.; Rojanasuphot, S.; Sangkawibha, N. Original antigenic sin in dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1983, 32, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Gresh, L.; Halloran, M.E.; Mercado, J.C.; Kuan, G.; Gordon, A.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science 2017, 358, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, M.J.; Magnani, D.M.; Grifoni, A.; Kwon, Y.C.; Gutman, M.J.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Gangavarapu, K.; Sharkey, M.; Silveira, C.G.T.; Bailey, V.K. , et al. Ontogeny of the b- and t-cell response in a primary zika virus infection of a dengue-naive individual during the 2016 outbreak in miami, fl. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2017, 11, e0006000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahala, W.M.; Silva, A.M. The human antibody response to dengue virus infection. Viruses 2011, 3, 2374–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.R.; Metz, S.W.; Baric, R.S. Dengue vaccines: The promise and pitfalls of antibody-mediated protection. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallichotte, E.N.; Widman, D.G.; Yount, B.L.; Wahala, M.W.; Durbin, A.; Whitehead, S.; Sariol, C.A.; Crowe, J.E., Jr.; de Silva, A.M.; Baric, R.S. A new quaternary structure epitope on dengue virus serotype 2 is the target of durable type-specific neutralizing antibodies. MBio 2015, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurane, I.; Rothman, A.L.; Livingston, P.G.; Green, S.; Gagnon, S.J.; Janus, J.; Innis, B.L.; Nimmannitya, S.; Nisalak, A.; Ennis, F.A. Immunopathologic mechanisms of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. Arch Virol Suppl 1994, 9, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mapalagamage, M.; Weiskopf, D.; Sette, A.; De Silva, A.D. Current understanding of the role of t cells in chikungunya, dengue and zika infections. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Rothman, A.L. Understanding the contribution of cellular immunity to dengue disease pathogenesis. Immunological reviews 2008, 225, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivino, L. Understanding the human t cell response to dengue virus. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2018, 1062, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- de Alwis, R.; Bangs, D.J.; Angelo, M.A.; Cerpas, C.; Fernando, A.; Sidney, J.; Peters, B.; Gresh, L.; Balmaseda, A.; de Silva, A.D. , et al. Immunodominant dengue virus-specific cd8+ t cell responses are associated with a memory pd-1+ phenotype. Journal of virology 2016, 90, 4771–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elong Ngono, A.; Chen, H.W.; Tang, W.W.; Joo, Y.; King, K.; Weiskopf, D.; Sidney, J.; Sette, A.; Shresta, S. Protective role of cross-reactive cd8 t cells against dengue virus infection. EBioMedicine 2016, 13, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiskopf, D.; Angelo, M.A.; Bangs, D.J.; Sidney, J.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; de Silva, A.D.; Lindow, J.C.; Diehl, S.A.; Whitehead, S. , et al. The human cd8+ t cell responses induced by a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine are directed against highly conserved epitopes. Journal of virology 2015, 89, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiskopf, D.; Cerpas, C.; Angelo, M.A.; Bangs, D.J.; Sidney, J.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Sanches, F.P.; Silvera, C.G.; Costa, P.R. , et al. Human cd8+ t-cell responses against the 4 dengue virus serotypes are associated with distinct patterns of protein targets. The Journal of infectious diseases 2015, 212, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltaufderhyde, K.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Green, S.; Macareo, L.; Park, S.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Rothman, A.L.; Mathew, A. Activation of peripheral t follicular helper cells during acute dengue virus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases 2018, 218, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vargas, L.A.; Mathew, A. Peripheral follicular helper t cells in acute viral diseases: A perspective on dengue. Future Virol 2019, 14, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmold Hait, S.; Vargas-Inchaustegui, D.A.; Musich, T.; Mohanram, V.; Tuero, I.; Venzon, D.J.; Bear, J.; Rosati, M.; Vaccari, M.; Franchini, G. , et al. Early t follicular helper cell responses and germinal center reactions are associated with viremia control in immunized rhesus macaques. Journal of virology 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, S. A brief history of t cell help to b cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.S.; Deenick, E.K.; Batten, M.; Tangye, S.G. The origins, function, and regulation of t follicular helper cells. J Exp Med 2012, 209, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.; Ulrich, B.J.; Nelson, A.S.; Panangipalli, G.; Kharwadkar, R.; Wu, W.; Xie, M.M.; Fu, Y.; Turner, M.J.; Paczesny, S. , et al. Bcl6 and blimp1 reciprocally regulate st2(+) treg-cell development in the context of allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020, 146, 1121–1136.e1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, R.; Freyn, A.W.; Wang, J.; Strohmeier, S.; Lederer, K.; Locci, M.; Zhao, H.; Angeletti, D.; O'Connor, K.C. , et al. Cd4+ follicular regulatory t cells optimize the influenza virus-specific b cell response. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, T.; Bela-Ong, D.B.; Toh, Y.X.; Flamand, M.; Devi, S.; Koh, M.B.; Hibberd, M.L.; Ooi, E.E.; Low, J.G.; Leo, Y.S. , et al. Dengue virus activates polyreactive, natural igg b cells after primary and secondary infection. PLoS One 2011, 6, e29430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, K. Origin and function of circulating plasmablasts during acute viral infections. Front Immunol 2012, 3, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, N.L.; Onai, N.; Lanzavecchia, A. A role for toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: Up-regulation of tlr9 by bcr triggering in naive b cells and constitutive expression in memory b cells. Blood 2003, 101, 4500–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoja, P.; Perez-Guzman, E.X.; Rodriguez, I.V.; White, L.J.; Gonzalez, O.; Serrano, C.; Giavedoni, L.; Hodara, V.; Cruz, L.; Arana, T. , et al. Zika virus pathogenesis in rhesus macaques is unaffected by pre-existing immunity to dengue virus. Nature communications 2017, 8, 15674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Guzman, E.X.; Pantoja, P.; Serrano-Collazo, C.; Hassert, M.A.; Ortiz-Rosa, A.; Rodriguez, I.V.; Giavedoni, L.; Hodara, V.; Parodi, L.; Cruz, L. , et al. Time elapsed between zika and dengue virus infections affects antibody and t cell responses. Nature communications 2019, 10, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Collazo, C.; Pérez-Guzmán, E.X.; Pantoja, P.; Hassert, M.A.; Rodríguez, I.V.; Giavedoni, L.; Hodara, V.; Parodi, L.; Cruz, L.; Arana, T. , et al. Effective control of early zika virus replication by dengue immunity is associated to the length of time between the 2 infections but not mediated by antibodies. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020, 14, e0008285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzan-Rivera, N.; Serrano-Collazo, C.; Cruz, L.; Pantoja, P.; Ortiz-Rosa, A.; Arana, T.; Martinez, M.I.; Burgos, A.G.; Roman, C.; Mendez, L.B. , et al. Infection order outweighs the role of cd4(+) t cells in tertiary flavivirus exposure. iScience 2022, 25, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Jadi, R.; Segovia-Chumbez, B.; Daag, J.; Ylade, M.; Medina, F.A.; Sharp, T.M.; Munoz-Jordan, J.L.; Yoon, I.K.; Deen, J. , et al. Novel assay to measure seroprevalence of zika virus in the philippines. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27, 3073–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, V.; Ly, S.; Lorn Try, P.; Tuiskunen, A.; Ong, S.; Chroeung, N.; Lundkvist, A.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Deubel, V.; Vong, S. , et al. Clinical and virological factors influencing the performance of a ns1 antigen-capture assay and potential use as a marker of dengue disease severity. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2011, 5, e1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, T.N.; Anders, K.L.; Lien le, B.; Hung, N.T.; Hieu, L.T.; Tuan, N.M.; Thuy, T.T.; Phuong le, T.; Tham, N.T.; Lanh, M.N. , et al. Clinical and virological features of dengue in vietnamese infants. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2010, 4, e657. [Google Scholar]

- Avirutnan, P.; Punyadee, N.; Noisakran, S.; Komoltri, C.; Thiemmeca, S.; Auethavornanan, K.; Jairungsri, A.; Kanlaya, R.; Tangthawornchaikul, N.; Puttikhunt, C. , et al. Vascular leakage in severe dengue virus infections: A potential role for the nonstructural viral protein ns1 and complement. The Journal of infectious diseases 2006, 193, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.R.; Ranadeva, N.D.; Sirisena, K.; Wijesinghe, K.J. Roles of ns1 protein in flavivirus pathogenesis. ACS Infect Dis 2024, 10, 20–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podestà, M.A.; Cavazzoni, C.B.; Hanson, B.L.; Bechu, E.D.; Ralli, G.; Clement, R.L.; Zhang, H.; Chandrakar, P.; Lee, J.M.; Reyes-Robles, T. , et al. Stepwise differentiation of follicular helper t cells reveals distinct developmental and functional states. Nature communications 2023, 14, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sette, A.; Moutaftsi, M.; Moyron-Quiroz, J.; McCausland, M.M.; Davies, D.H.; Johnston, R.J.; Peters, B.; Rafii-El-Idrissi Benhnia, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Su, H.P. , et al. Selective cd4+ t cell help for antibody responses to a large viral pathogen: Deterministic linkage of specificities. Immunity 2008, 28, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appanna, R.; Kg, S.; Xu, M.H.; Toh, Y.X.; Velumani, S.; Carbajo, D.; Lee, C.Y.; Zuest, R.; Balakrishnan, T.; Xu, W. , et al. Plasmablasts during acute dengue infection represent a small subset of a broader virus-specific memory b cell pool. EBioMedicine 2016, 12, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangchinda, T.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Vasanawathana, S.; Limpitikul, W.; Tangthawornchaikul, N.; Malasit, P.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Screaton, G. Immunodominant t-cell responses to dengue virus ns3 are associated with dhf. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 16922–16927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouers, A.; Chng, M.H.Y.; Lee, B.; Rajapakse, M.P.; Kaur, K.; Toh, Y.X.; Sathiakumar, D.; Loy, T.; Thein, T.L.; Lim, V.W.X. , et al. Immune cell phenotypes associated with disease severity and long-term neutralizing antibody titers after natural dengue virus infection. Cell Rep Med 2021, 2, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivino, L.; Kumaran, E.A.; Jovanovic, V.; Nadua, K.; Teo, E.W.; Pang, S.W.; Teo, G.H.; Gan, V.C.; Lye, D.C.; Leo, Y.S. , et al. Differential targeting of viral components by cd4+ versus cd8+ t lymphocytes in dengue virus infection. Journal of virology 2013, 87, 2693–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangada, M.M.; Rothman, A.L. Altered cytokine responses of dengue-specific cd4+ t cells to heterologous serotypes. J Immunol 2005, 175, 2676–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.D.; Wang, H.; da Silva Antunes, R.; Tian, Y.; Tippalagama, R.; Alahakoon, S.U.; Premawansa, G.; Wijewickrama, A.; Premawansa, S.; De Silva, A.D. , et al. A population of cd4(+)cd8(+) double-positive t cells associated with risk of plasma leakage in dengue viral infection. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, N.; Eisenhauer, P.; Diehl, S.A.; Pierce, K.K.; Whitehead, S.S.; Durbin, A.P.; Kirkpatrick, B.D.; Sette, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Boyson, J.E. , et al. Rapid induction and maintenance of virus-specific cd8(+) t(emra) and cd4(+) t(em) cells following protective vaccination against dengue virus challenge in humans. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiskopf, D.; Bangs, D.J.; Sidney, J.; Kolla, R.V.; De Silva, A.D.; de Silva, A.M.; Crotty, S.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Dengue virus infection elicits highly polarized cx3cr1+ cytotoxic cd4+ t cells associated with protective immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, E4256–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elong Ngono, A.; Young, M.P.; Bunz, M.; Xu, Z.; Hattakam, S.; Vizcarra, E.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Tang, W.W.; Yamabhai, M.; Wen, J. , et al. Cd4+ t cells promote humoral immunity and viral control during zika virus infection. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15, e1007474. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, H.R.; Rampazo, E.V.; Gonçalves, A.J.; Vicentin, E.C.; Amorim, J.H.; Panatieri, R.H.; Amorim, K.N.; Yamamoto, M.M.; Ferreira, L.C.; Alves, A.M. , et al. Targeting the non-structural protein 1 from dengue virus to a dendritic cell population confers protective immunity to lethal virus challenge. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2013, 7, e2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.B.A.; Assis, M.L.; Vallochi, A.L.; Pacheco, A.R.; Lima, L.M.; Quaresma, K.R.L.; Pereira, B.A.S.; Costa, S.M.; Alves, A.M.B. T cell responses induced by DNA vaccines based on the denv2 e and ns1 proteins in mice: Importance in protection and immunodominant epitope identification. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.J.; Oliveira, E.R.; Costa, S.M.; Paes, M.V.; Silva, J.F.; Azevedo, A.S.; Mantuano-Barradas, M.; Nogueira, A.C.; Almeida, C.J.; Alves, A.M. Cooperation between cd4+ t cells and humoral immunity is critical for protection against dengue using a DNA vaccine based on the ns1 antigen. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2015, 9, e0004277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.G., Jr.; Atyeo, C.; Loos, C.; Montoya, M.; Roy, V.; Bos, S.; Narvekar, P.; Singh, T.; Katzelnick, L.C.; Kuan, G. , et al. Antibody fc characteristics and effector functions correlate with protection from symptomatic dengue virus type 3 infection. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabm3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vargas, L.A.; Mathew, A.; Salje, H.; Sousa, D.; Casale, N.A.; Farmer, A.; Buddhari, D.; Anderson, K.; Iamsirithaworn, S.; Kaewhiran, S. , et al. Protective role of ns1-specific antibodies in the immune response to dengue virus through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. The Journal of infectious diseases 2024, 230, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivarthi, U.K.; Kose, N.; Sapparapu, G.; Widman, D.; Gallichotte, E.; Pfaff, J.M.; Doranz, B.J.; Weiskopf, D.; Sette, A.; Durbin, A.P. , et al. Mapping the human memory b cell and serum neutralizing antibody responses to dengue virus serotype 4 infection and vaccination. Journal of virology 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyamvada, L.; Cho, A.; Onlamoon, N.; Zheng, N.Y.; Huang, M.; Kovalenkov, Y.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Angkasekwinai, N.; Pattanapanyasat, K.; Ahmed, R. , et al. B cell responses during secondary dengue virus infection are dominated by highly cross-reactive, memory-derived plasmablasts. Journal of virology 2016, 90, 5574–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]