Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a high global burden, with millions of lives lost and a tremendous economic cost. The SARS-Cov-2 continues to adapt, and despite the rapid development of vaccines and successful vaccination strategies, several variants of concern have emerged. Most recently, the Omicron XBB.1.5.a variant has raised attention, but other variants have been reported that including B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), P.1 (Gamma), and B.1.617.2 (Delta) [

1]. The spread of Omicron variants, which display greater transmissibility, has demonstrated a resistance to neutralization [

2,

3]. The study of humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 is essential to map population and individual responses to viral infection and vaccination. Antibody recognition of linear B-cell epitopes varies among individuals [

4], but an immunodominant antibody analysis is important for serodiagnosis and prognosis [

5].

Cross-reactivity is a major concern in developing diagnostic tests, and SARS-CoV-2 serological assays mostly use Spike (S) or N (Nucleoprotein) full-length proteins or subdomains. Although this strategy increases sensibility, it also increases the chance of false-positive results. Despite the low similarity of SARS-CoV-2 proteins to other human coronaviruses (HCoV), some conserved regions can present cross-reactivity [

4]. In addition, there is evidence that the response to SARS-CoV-2 infections appears to be shaped by previous HCoV exposures, which have the potential to raise broadly neutralizing responses [

4]. Interestingly, cross-reactivity with other endemic viruses has been uncovered, including other respiratory and dengue viruses (DENV) [

4,

6,

7].

Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and its receptor-binding domain (S1-RBD) were significantly increased in DENV-infected patients compared to normal controls [

6]. In addition, anti-S1-RBD IgG antibodies purified from S1-RBD hyperimmune rabbit sera could cross-react with DENV envelope protein (E) and non-structural protein 1 (NS1) [

6]. Functionally,

in vitro assays demonstrated that DENV infection and DENV NS1-induced endothelial hyperpermeability were inhibited in the presence of anti-S1-RBD IgG, and passive transfer anti-S1-RBD IgG induced some protection against DENV-infected mice [

6]. Also,

in vitro, analysis using COVID-19 patient sera showed neutralizing activity against dengue infection [

6].

Cross-reactive antibodies represent a double-edged sword; some can induce neutralization, but others can drive antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). ADE is a phenomenon in which antibodies increase virus infection, as observed with DENV, West Nile, Ebola, measles, RSV, and human immunodeficiency virus [

8]. Virus-antibody complexes bind to Fc receptors (FcRs), expressed on immune cells, by the antibody's fragment crystallizable (Fc) portion. Human mAbs against SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein were found to enhance the virus infection

in vitro by the FcγR-mediated pathway [

9]. Another study using serum samples of acute and convalescent COVID-19 patients demonstrated ADE by FcγR-mediated and C1q-mediated pathways [

10].

ADE also can induce enhanced immune activation [

8]. SARS-CoV-2 ADE has been under debate since the beginning of the pandemic, especially due to concerns related to vaccination and the emergence of new variants. Although

in vitro evidence supports the potential risk, no conclusive data has been reported that ADE is related to disease severity. ADE is a rare event that requires many conditions associated with antibodies, viruses, and hosts [

11,

12]. Some circumstances involved with antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 are still unclear, such as the duration of humoral response and the antibody repertoire pre-formed due to previous infections. Each individual has a collection of B cell memory and antibodies that can drive the immune response against SARS-CoV-2.

In this study, we mapped the immunodominant IgG linear B-cell epitopes and evaluated their cross-reactivity profile against pre-pandemic Dengue-positive serum samples. Several epitopes identified in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein showed a level of residue similarity to DENV proteins, and we hypothesized that pre-formed DENV antibodies could interact with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The data suggest that previous infections with DENV, and the resulting antibodies, could potentiate SARS-CoV-2 infections of monocytes through ADE.

2. Results

2.1. Mapping of IgG epitopes within SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein.

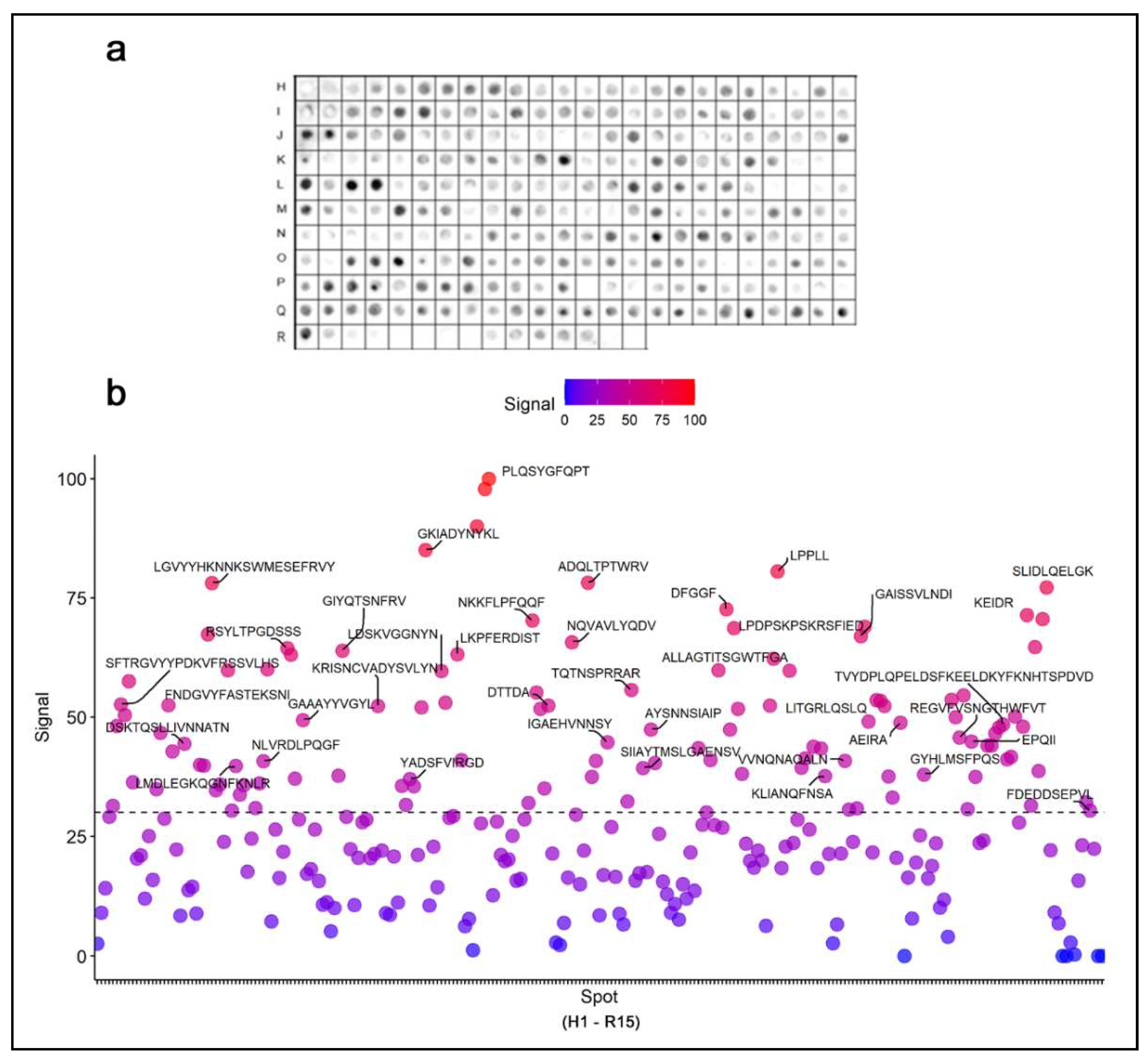

The coding sequence of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 was represented by a library of 15-mer peptides offset by five amino acids synthesized directly onto a cellulose membrane (

Figure S1 and

Table S1). Immunodominant epitopes were identified by a Spot synthesis analysis using a pool of severely hospitalized COVID-19 individuals and chemiluminescent imaging of bound IgG (

Figure 1). Signal intensities were normalized to the maximum signal, and an intensity level cut-off of 30% was used to define epitopes. In total, 41 linear IgG B-cell epitopes were identified that ranged from 5 to 15 amino acids (

Table 1). Nineteen epitopes were in the S1 domain, seven in the N-terminal domain (NTD), seven in the receptor binding domain (RBD), two in subdomain 1 (SD1), and another three in subdomain 2 (SD2). One epitope, TQTNSPRRAR, was detected in the core region of the furin cleavage site (685RS686). The S2 fragment housed 22 epitopes that included an epitope, LPDPSKPSKR SFIED, encompassing the TMPRSS2 cleave site (815RS816) and fusion peptide 1 (816-837). Three epitopes were found in the first Heptad repeat (HR1; 920-970) and two in Heptad repeat 2 (HR2; 1163-1202). No epitopes were localized to the transmembrane domain (TMD), and only one in the C-terminal after the TMD. Among the epitopes with signals greater than 80%, two were in the RBD (GKIADYNYKL and PLQSYGFQPTGVGY) and one in the S2 domain (LPPLL). Following their localization, each epitope sequence was subjected to a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool for proteins (BLASTp) and multiple sequence alignments restricted to the coronavirus family. Most epitopes showed no commonality to endemic coronavirus, considering four consecutive and identical amino acids as a minimum binding site for an epitope, suggesting that some epitopes are specific to SARS-CoV-2 (

Figure S2).

2.2. Cross-reactivity with anti-DENV antibodies

Previous evidence suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 S1-RBD could be recognized by antibodies in patients infected with DENV. When we expanded the BLASTp parameters to include the dengue virus (Taxid: 12637), twenty-one sequences presented a potential for cross-reactivity based on the criteria above (

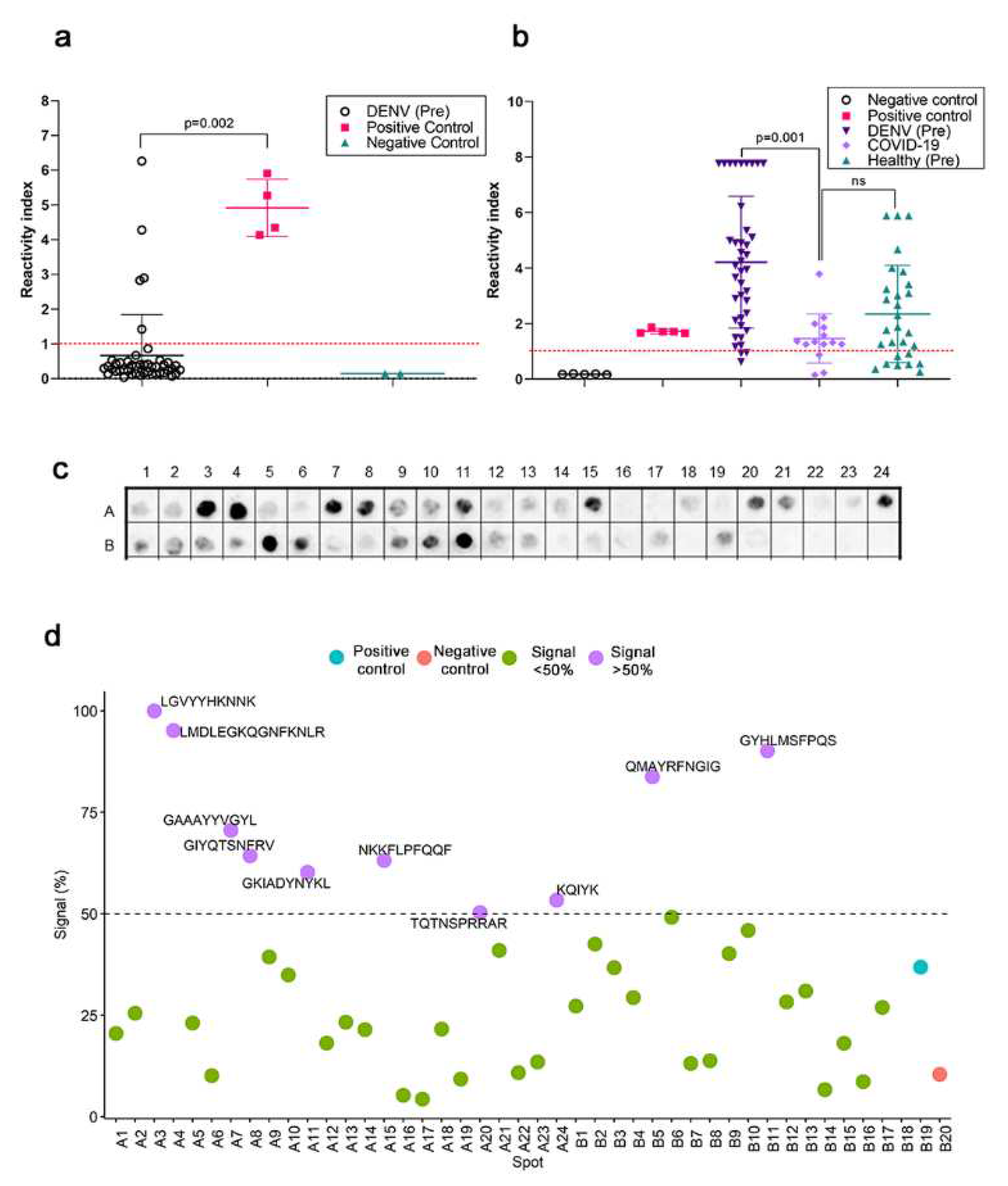

Figure S2). Next, the reactivity of serum samples (n-45) from patients with DENV infections before the COVID-19 pandemic antibodies were evaluated in a commercial ELISA utilizing the Spike and nucleoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 as targets for capturing antibodies. Serum samples from hospitalized COVID-19 from the first wave (n=17) were used as controls along with positive and negative controls from the kit.

Figure 2a presents the reactivity index of the individual samples and shows that five samples from DENV patients were positive (11%).

The serum reactivity from COVID-19 patients was measured in an ELISA assay for DENV (1-4) seroreactivity (

Figure 2b). Eleven of fourteen samples from COVID-19-infected individuals (79%) were positive. Seroreactivity for anti-DENV antibodies (IgG) was high among healthy blood donors (n=20/28; 71.4%), attesting to the prevalence of infections in Brazil, an endemic area. As expected, the highest seroreactivity was found in the small cohort of DENV-positive, pre-pandemic sera (37/40; 92.5%). Pre-pandemic DENV-positive individuals had a higher titer of antibodies that displayed a mean reactivity index of 4.2 (95% CI, 3.4-4.9), significantly different from COVID-19 infected individuals (RI = 1.4; 95% CI, 0.9-1.9; p=0.001). No significant difference was calculated in the mean and distribution of the DENV reactivity index in the healthy population and infected individuals.

A spot synthesis analysis was used to determine if the reactivity of pre-pandemic DENV serum could bind to the SARS-CoV-2 specific epitopes in its spike protein (

Figure 2c). From the forty-one previously identified epitopes, ten presented a normalized signal intensity >50% to pre-pandemic DENV serum (

Figure 2d), which were defined to be cross-reactive based on statistical analysis. Three cross-reactive regions were in S1-NTD, two in the RBD region, one in S1/SD1, one in the furin cleavage site, and the remaining three in the S2 domain.

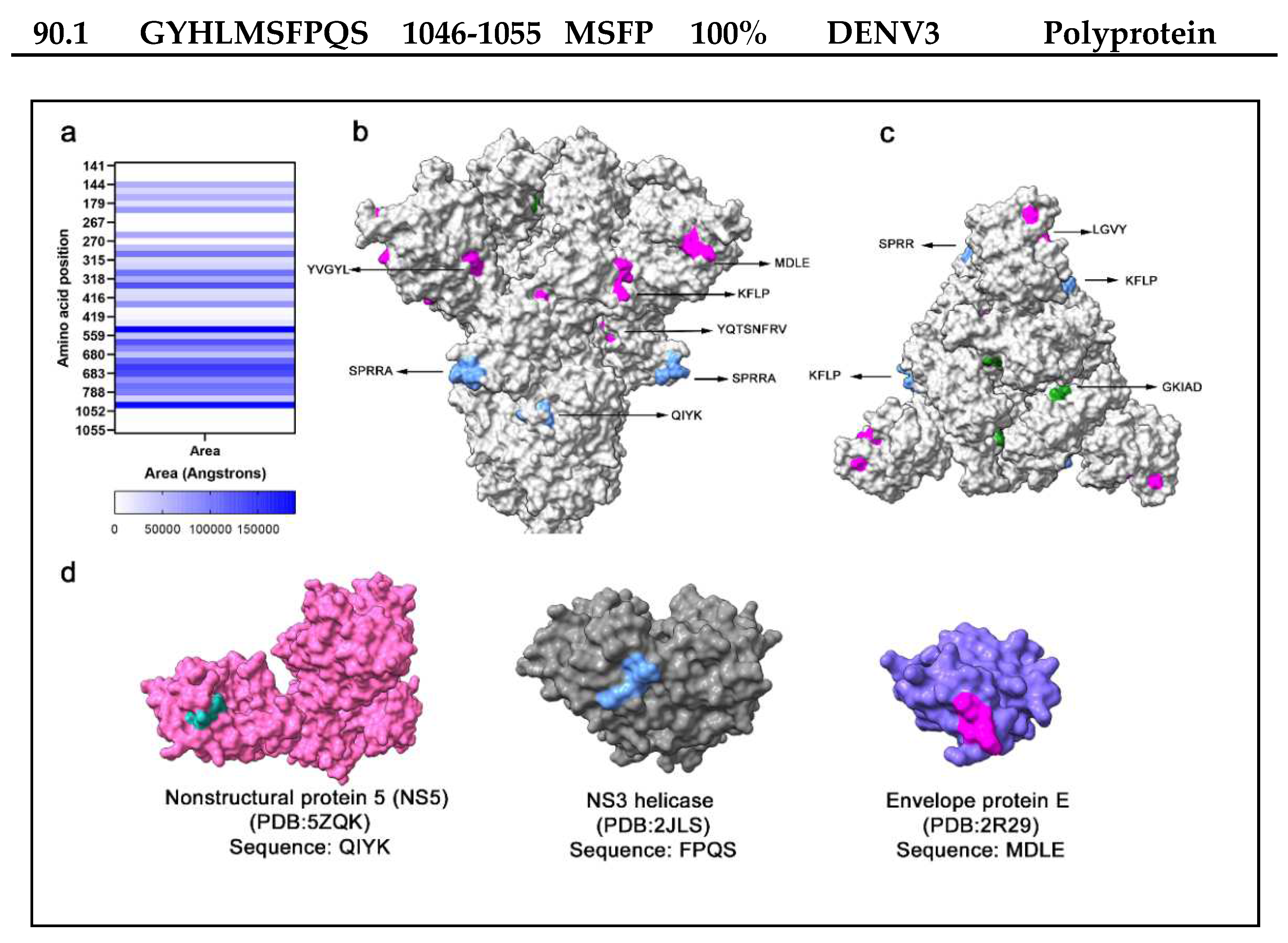

2.3. Bioinformatic analysis

An open question was if sequence similarity between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and DENV proteins alone could explain the observed cross-reactivity. Additional Blastp searches were performed with the ten (10) epitope sequences displaying cross-reactivity to identify DENV (1-4) proteins or polyproteins (

Table 2). Searches were conducted for short input sequences of at least four amino acids to identify mimetic peptides in the Dengue virus. Most Spike epitopes (n=8) had a sequence of at least four amino acids identical to a dengue protein. The other two epitopes presented sequence gaps with a lower sequence identity. Identified sequences have high conservation among VoCs (

Figure S1) and low identity against endemic coronavirus (

Figure S3).

Sequence identity

per se does not signify cross-reactivity, as antibody interaction also depends on structure conformation and accessibility to antigen. Therefore, potential cross-reactive sequences were located within the spike protein monomer and trimer, and the solvent accessibility area (SASA) was calculated (

Figure 3a), which is correlated to the spatial arrangement and exposure of residues to solvent. In a side view of the Spike trimer (

Figure 3b), several surface-exposed residues in cross-reactive epitopes were localized, supporting the potential to interact with antibodies (

Figure 3b). Likewise, highly surface-exposed areas were present at the top of the trimeric spike protein (

Figure 3c). The FPQS residues are in a buried surface area of the spike protein with low solvent accessibility and are unlikely to represent a cross-reactive site. Within the Ns5 and envelope protein E of DENV2 and the NS3 helicase of DENV4, searches of the epitope sequences in the protein databank revealed similar epitope sequences with surface exposure (

Figure 3d).

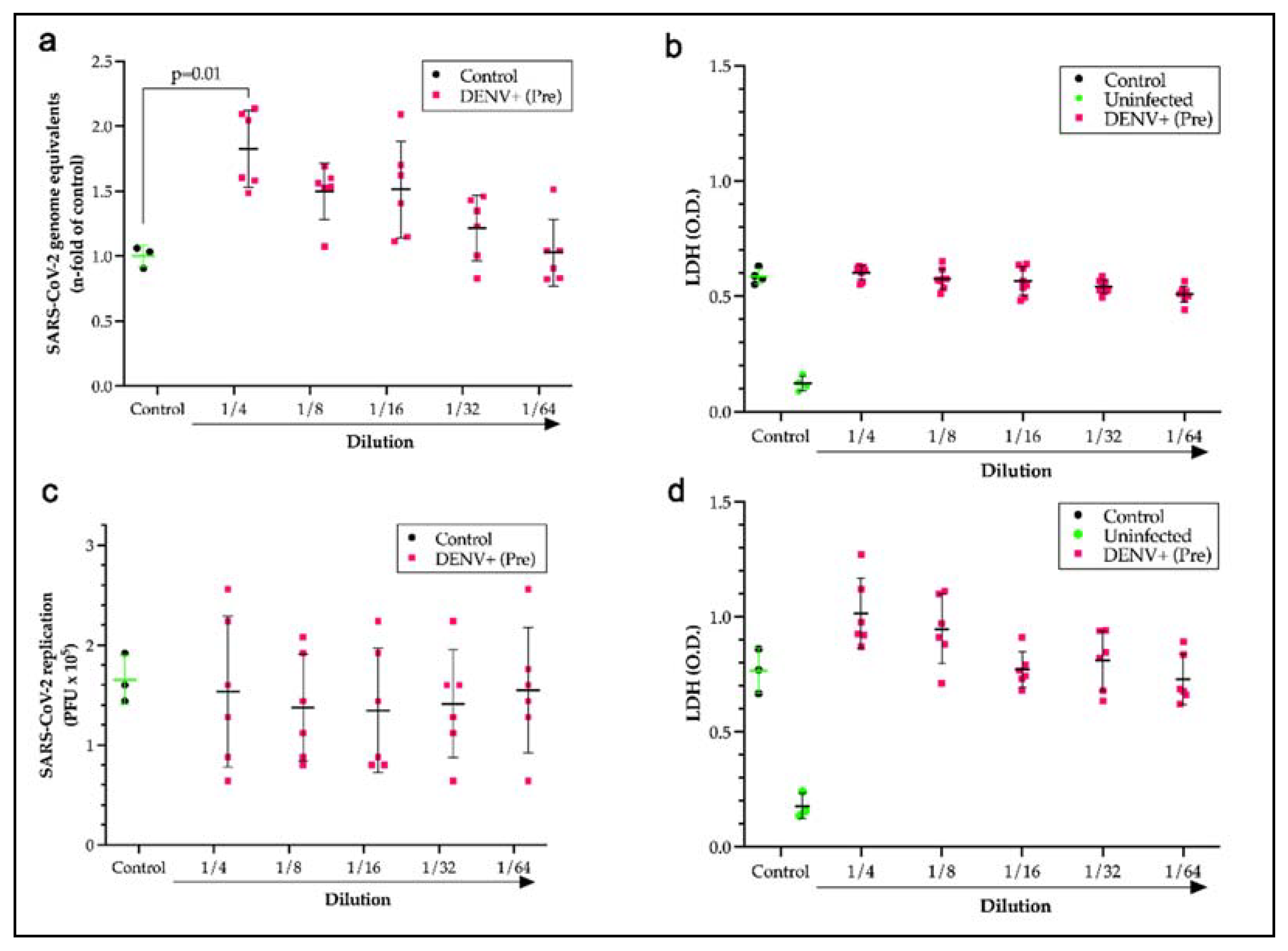

2.4. Pre-pandemic DENV sera displays antibody-dependent enhancement.

After identifying cross-reactive sites, the question remained as to whether the presence of antibodies formed during a DENV infection could potentiate antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 infections. To test this hypothesis, monocytes that express Fc receptors (FcR) were used as a model system for disease with SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of a pool of pre-pandemic DENV-positive sera over a 2-fold serial dilution series. Incubation of the virus with pre-pandemic DENV-positive sera at a dilution of 1 to 4 induced a significant increase (p=0.014) in the viral load of monocytes that was 1.7 times the control loads (

Figure 4a). Measurements of lactate dehydrogenase for cell death showed no significant loss of monocytes from the increase in viral entry, which was expected since SARS-CoV-2 replication is aborted in monocytes (

Figure 4b). The neutralization capacity of a DENV patient serum pool was also evaluated by plaque assay using Calu-3 cells. No neutralization (

Figure 4c) or significant cell death (

Figure 4d) was measured for the pre-pandemic Dengue positive pool compared to COVID-19 controls and healthy human serum.

3. Discussion

The World Health Organization has recently declared the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, the emergence of variants that display increased transmissibility are refractory to previously neutralizing antibodies or both perpetuates the importance of continued studies on the humoral response to SARS-CoV-2, and other pathogens, to develop next-generation vaccines and therapies. Here, we began by identifying the immunodominant epitopes in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 that are recognized by antibodies in the serum of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The peptide microarray identified a total of 41 epitopes. These epitopes were distributed across different domains of the Spike protein, including the S1, NTD, RBD, SD1, SD2, furin cleavage site, S2 fragments, and heptad repeats 1 and 2. Some of these epitopes show sequence similarities to epitopes reported in previous studies on SARS-CoV-2, indicating consistency between the techniques and serum panels used [

13,

14,

15], which is important for defining immunodominant epitopes across multiple populations stimulated by natural infections and vaccinations.

Epitope mapping is also a strategic platform for developing broadly neutralizing antibodies or nanobodies for prophylactic, diagnostic, and therapeutic use [

16]. Neutralizing epitopes are predominantly located within the NTD and RBD, and antibodies binding to the RBD can account for over 90% of neutralizing activity in convalescent sera [

19]. Neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) can also target S2 stem helix (SH) and S2 fusion peptide (FP) regions [

17]. Immune evasion of variants of concern is driven by mutations in the spike protein that threaten natural and vaccine-induced immunity. However, the presence of conserved pan-variant epitopes that conferred broad neutralization has great potential for therapy and vaccine design [

20,

21,

22,

23].

The binding mode of nAbs can be divided into four main classes depending on the location of their epitopes in the spike protein [

18]. The RBD region is targeted by class 1 and class 2 antibodies that include the RBM and can compete with ACE2 binding. The major IgG epitopes CV19/SG/13huG and CV19/SG/14huG are located within this region. Class 3 RBD antibodies bind to regions flanking the ACE2-binding region, and the epitopes CV19/09huG and CV19/SG/12huG could be involved in the binding of nAbs. Importantly, this region contains highly conserved residues in the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 RBDs that could confer broad cross-reactivity as observed with antibody S30924, which also neutralized SARS-CoV-2 Omicron B.1.1.529 VoC [

24]. The epitope recognized by class 4 antibodies is highly conserved in the RBD but does not directly block ACE2–RBD binding [

17]. This cryptic region spans from residues 369 to 385, but our study found low reactivity for any epitope in this region.

Changes to epitope sequences in the NTD and RBD will likely contribute to immunity escape by variants. In contrast, the neutralizing epitopes in the S2 subunit are more conserved across variants [

25]. However, low reactivity was observed for the S2 SH region, which spans 14 residues (1146–1159) and is conserved across beta-CoVs [

26]. The S2 FPs are also highly conserved among all coronavirus, suggesting an antibody targeting this region could display broad-spectrum activity. The epitope CV19/SG/26huG (LPDPS KPSKRSFIED) was identified in the S2 FP1, which overlaps with the 'RSFIEDLLF' motif bound by several human monoclonal antibodies isolated from convalescent patients that bind the [

27,

28]. The R815 conserved residue is the site of S2′ of TMPRSS2, and by targeting this region, antibodies would interfere with cleavage and inhibit membrane fusion of S protein [

28].

Spot synthesis analysis is also useful for identifying cross-reactive epitopes, which is a significant concern in developing serological tests, and SARS-CoV-2 is no exception. Although SARS-CoV-2 proteins exhibit low sequence similarity to other human coronaviruses (HCoV), previous evidence has suggested that the response to SARS-CoV-2 response may be influenced by earlier exposures to other coronaviruses and other endemic viruses, including respiratory viruses [

29]. Fifteen highly antigenic epitopes against pathogens, self-proteins, and common human viruses in a cohort of pre-pandemic individuals naïve to SARS-CoV-2 showed cross-reactivity with the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [

30]. These points to a potential limitation of linear B-cell epitope mapping from the presence of cross-reactive antibodies in serum samples obtained from individuals with unknown clinical histories. Only eight epitopes identified in this study were non-specific for SARS-CoV-2 [

30].

By confirming the results with bioinformatics, it is possible to identify cross-reactive epitope sequences based on a minimum antibody binding site of four consecutive amino acids. Here, ten sequences exhibited potential cross-reactivity with the dengue virus. Dengue fever is a vector-borne viral disease caused by the flavivirus dengue virus that has four serotypes, each with three structural and seven non-structural proteins [31, 32]. It is endemic to tropical regions worldwide that house approximately 2.5 billion people, and there are estimated to be 400 million yearly cases globally. Previous data reported that pre-pandemic dengue patient sera contain cross-reactive antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 that can cause false-positive SARS-CoV-2 serology results and could partially explain the low specificity of some serological tests [

33,

34]. A recent study highlighted the antigenic similarity between the SARS-CoV-2 S1-RBD regions and DENV proteins (E and NS1) has the potential to induce cross-reactive antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 S1-RBD immunization

in vivo using an experimental animal model. It was demonstrated that DENV cross-reactive antibodies might cause false-positive results in dengue serological tests and potentially hinder dengue infection [

35]. Using commercial ELISA kits for COVID-19 and DENV, our results demonstrated that cross-reactivity exists between antibodies generated in response to SARS-CoV-2 and DENV. These findings highlight the weakness of full-length viral proteins in serological tests containing a mixture of definable specific and non-specific linear B-cell epitopes.

Of particular importance to the situation with SARS-CoV-2 and DENV is those cross-reactive DENV antibodies that could lead to ADE. ADE describes the observation of heightened or deviated viral infections instead of neutralization. ADE has been observed in various viral infections, including DENV, West Nile virus, Ebola virus, measles, respiratory syncytial virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [

8]. ADE has been extensively studied about Dengue fever. Individuals with pre-existing immunity against one serotype of DENV are at a higher risk of developing severe dengue shock syndrome (DSS) or dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) when infected with a different serotype [

31]. This fact is attributed to antibodies with low neutralizing activity but can facilitate viral entry into macrophages via Fc receptors [

36]. A.D.E.-driven infection of macrophages can increase viral replication and load [

37]. This clinical concern has challenged the development of a safe and effective dengue vaccine that induces a balanced immune response against all serotypes to avoid ADE [

38].

Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 does not replicate productively in macrophages, unlike DENV. Macrophages can phagocyte the virus, but it does not result in productive infection. However, SARS-CoV-2 entry into immune cells leads to an abortive infection followed by host cell pyroptosis, the release of proinflammatory cytokines, and the activation of inflammasomes [

39,

40]. Alternatively, infected monocytes can act like trojan horses, spreading the virus to different tissues. Viruses can ride in immune cells, leading to the trans-infection of target permissive cells [

41]. Thus, ADE could contribute to disease severity and Long COVID-19. Elevated levels of monocytes and persistence of S1 antigen have been detected in monocytes in severe COVID-19 patients and Long COVID patients up to 15 months post-infection [

42]. Also, seeing RNA and Spikes in peripheral blood has been associated with Long COVID-19 [

43].

Apart from FcR-dependent ADE, there is also evidence of FcR-independent ADE in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antibodies that recognize specific binding domains on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein can induce structural changes that facilitate viral entry and infection. Some antibodies can mediate the ADE of disease

in vitro in an FcR-independent manner [

44]. Human mAbs against SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein were found to enhance the virus infection

in vitro by the FcγR-mediated pathway [

9]. In addition, ADE was reported for neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) using SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus infection on FcγRIIB-expressing B cells, bivalent interaction of antibodies with S trimer RBDs enabled enhanced condition of SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus on FcγRIIB-expressing B cells [

45]. A study revealed that FcγR- and/or C1q-mediated ADE was detected in 50% of the IgG-positive sera. Interestingly, most of these sera also exhibited neutralizing activity without FcγR and C1q. ADE antibodies were found in 41.4% of acute COVID-19 patients, suggesting the potential for ADE to promote virus replication even in the early phase of infection [

46]. The authors proposed that C1q-mediated ADE may occur in the respiratory tissues of COVID-19 patients, and possibly ADE plays a role in the exacerbation of the disease [

46].

Different factors contribute to antibody efficacy, depending on titers, affinity viral epitopes, and stoichiometry. The production of neutralizing antibodies is considered the primary goal of vaccination. Still, cross-reactive or non-neutralizing antibodies may also be produced, which can impact the severity of the infection. The presence of cross-reactive antibodies or non-neutralizing antibodies may increase disease severity through ADE [

47]. Although ADE has not been observed on a widespread scale in COVID-19 cases, the risks associated with ADE include the potential for more severe disease outcomes, increased viral replication, and exacerbated immune responses.

In vitro ADE does not always correlate with enhanced infection

in vivo because other antibody functions could play a role in viral clearance, such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). Previous studies with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies have shown

in vitro enhancement of infection but

in vivo protection in animal models [

48]. Evidence of ADE in COVID-19 vaccines has been reported in preclinical animal models [

49]. In the context of SARS-CoV-2, ADE has been debated since the pandemic, particularly concerning the potential risk associated with vaccination, convalescent serum therapy, and the emergence of new variants. A raised concern in vaccine development, A.D.E. was not significatively demonstrated in COVID-19 vaccines [

50]. Possibly, because highly fucosylated antibodies of vaccinees did not cause ADE, but fucosylated antibodies produced in acute primary infection or convalescents sera can induce it [

39]. It is essential for vaccine development to balance between ADE and neutralizing antibodies. Candidates for vaccines must elicit an immune response that produces neutralizing antibodies capable of successfully preventing viral entry without encouraging ADE Epitope selection and studying cross-reactive antibodies. ADE is essential for rationalizing vaccines, antibody therapy, and serological diagnostic tests. Our results highlight that pre-infection with DENV increases monocyte infection with SARS-CoV-2

in vitro. This result opens new avenues to study the influence of cross-reactive DENV antibodies on COVID-19 severity by focusing on a complete map of the humoral responses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Samples

Serum panels comprised of either COVID-19-infected individuals (n=17) or Dengue (1-4) pre-pandemic serum (n=45) samples were utilized. All COVID-19 patients were confirmed positive for a SARS-CoV-2 infection by a PCR diagnostic test. Additional negative controls (n=28) included sera collected before the pandemic from healthy individuals from blood bank donators (HEMORIO, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Patient privacy is maintained by excluding identifying information. Serum samples from individuals with Dengue were collected before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and generously provided by the Laboratory of Flavivirus of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

4.2. B-Linear Epitope Mapping

A library of two hundred, fifty-one peptides that spanned the entire coding sequence of Spike protein (P0DTC2) of SARS-CoV-2 were retrieved from the UniProt database (

http://www.uniprot.org/: Accessed 27 January 2020). Microarrays of peptides and a pool of human COVID-19 patient sera (n=12; 1:100) were used to map linear B cell IgG epitopes using an Auto-Spot Robot ASP-222 (Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments AG, Köln, Germany) according to a previous SPOT synthesis protocol [

51]. Library construction (

Table S1) and program execution were conducted with the MultiPep program (Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments AG, Köln, Germany). Positive and negative controls were included, and chemiluminescent signals were detected using goat ant-human IgG (H+L) alkaline phosphatase (Lot JA1121836; 1:5000; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) on an Odyssey FC (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA) using the same conditions described previously [

52]

4.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA assays were performed using a commercial COVID-19 IgG kit (DiaPro, Diagnostic Bioprobe srl, Milan, Italy), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each microplate strip has its wells coated with Nucleocapsid and Spike-specific antigens, making it possible to map the serological response to the different IgG produced. To detect DENV (1-4) IgG antibodies, a commercial kit SERION ELISA classic/antigen Dengue Virus IgG (#ESR114G; Virion/Serion GmbH, Würzburg, Germany) was used. Tests were performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Results were represented as reactivity index calculated using the formula (IR = sample absorbance/cut-off).

4.4. In silico analysis

Blastp (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used to find cross-reactive sequences in SARS-CoV-2 epitopes that match the dengue virus (Taxid: 12637). The website was accessed on 16 May 2023. The Blastp algorithm parameter was set as follows: expect threshold 30,000, word size 2, matrix PAM30, gap cost set to existence = nine and extension = 1; the compositional parameter was set to no adjustment, and the low complexity filter was disabled and adjusted for short input sequences. The results from Blastp analysis were screened and filtered for at least four contiguous and identical amino acid residues with the DENV (1-4) peptides with no gap and no mismatched residues. Spike trimer protein in a closed state was retrieved from I-Tasser (

https://zhang group.org/I-TASSER/, accessed on 5 November 2022). Annotation of epitopes and cross-reactive sites was performed using Chimera X [

53]. The accessible surface area was performed by using the accessibility calculation for protein (ver. 1.2) online server that calculates the solvent-accessible surface areas of the spike protein (P0DTC2) amino acids (

http://cib.cf.ocha.ac.jp/ bitool/ASA/; Accessed on 10, February 2023).

4.5. Cells, viruses, and reagents

African green monkey kidney cells (Vero, E6 cell; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) and human lung epithelial cell lines (Calu-3) were expanded in high glucose DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Pen/Strep; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque, GE HealthCare) from buffy-coat blood preparations from healthy donors. PBMCs (2 x 106 cells) were plated into 48-well plates (NalgeNunc Int Corrp, NY, U.S.A.) in RPMI-1640 with 5% inactivated male human A.B. serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.) for 3h. Non-adherent cells were removed, and monocytes were maintained in DMEM (low-glucose) with 5% human serum and 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The purity of monocytes was above 90%, as determined by flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil) using anti-CD3 (B.D. Biosciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and anti-CD14 (B.D. Biosciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada) antibodies. SARS-CoV-2 (GenBank accession no MT710714) was expanded in Vero E6 cells. Viral isolation was performed after a single passage in cell culture in 150 cm2 flasks with high glucose DMEM plus 2% FBS. Observations for cytopathic effects were performed daily and peaked 4 to 5 days after infection. All procedures related to virus culture were handled in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) multiuser facilities, according to WHO guidelines. Virus titers were determined as plaque-forming units (PFU/mL), and virus stocks were kept in -80 °C ultralow freezers.

4.6. Infections and virus titration

Infections were performed with SARS-CoV-2 at M.O.I. of 0.1 in low (monocytes) or high (Calu-3) glucose DMEM without serum. Viral input was incubated with diluted serum samples for 15 min before exposure to cell culture. After 1h, the unbound virus was removed, and cells were washed and incubated with a complete medium. For virus titration, monolayers of Vero E6 cells (2 x 104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were infected with serial dilutions of supernatants containing SARS-CoV-2 for 1h at 37 °C. Semi-solid high glucose DMEM medium containing 2% FBS and 2.4% carboxymethylcellulose was added, and cultures were incubated for three days at 37 °C. Then, the cells were fixed with 10% formalin for 2h at room temperature. The cell monolayer was stained with 0.04% solution of crystal violet in 20% ethanol for 1h. Plaque numbers were scored in at least three replicates per dilution by independent readers blinded to the experimental group, and the virus titers were determined by plaque-forming units (PFU) per milliliter. Experimental procedures involving human cells from healthy donors were performed with samples obtained after written informed consent.

4.7. Molecular detection of virus R.N.A. levels

According to the manufacturer's instructions, total R.N.A. was extracted from cells using QIAamp Viral RNA (Qiagen-Sciences Inc Germantown, MD, U.S.A.). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using QuantiTect Probe RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen Sciences Inc Germantown, MD, U.S.A.) in a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.). Amplifications were performed in 15 µL reaction mixtures containing 2X reaction mix buffer, 50 µM of each primer, 10 µM of the probe, and 5 µL of R.N.A. template. Primers, probes, and cycling conditions followed the protocol the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, U.S.A.) recommended to detect the SARS-CoV-2. A standard curve method was employed for virus quantification. The housekeeping gene RNAse P was amplified to reference the cell quantity assayed. The Ct values for this target were compared to calibrations obtained from 102-107 cells.

4.8. L.D.H. measurement

Cell death was determined by proxy using the level of liberated lactate dehydrogenase (L.D.H.) activity in supernatants using CytoTox® Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.). Supernatants were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 1 min before an assay to remove cellular debris.

5. Conclusions

We have utilized spot synthesis analysis to map immunodominant epitopes in the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The distribution of these epitopes across different domains of the Spike protein highlights the complexity of the humoral immune response and the potential for diverse antibody interactions. Further, our findings suggest that individuals with a previous dengue virus infection may harbor cross-reactive antibodies that can lead to ADE. This observation raises concerns regarding the potential risk of severe disease outcomes in individuals with a history of dengue infection upon SARS-CoV-2 exposure which affects nearly a third of the world population. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the mechanistic basis of ADE and its impact on disease severity in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The sequence similarities to previously reported epitopes in SARS-CoV-2 highlight the importance of understanding the immunodominance of epitopes in the population. This knowledge can aid in the development of broadly neutralizing antibodies or nanobodies for prophylactic, diagnostic, and therapeutic purposes. The presence of conserved pan-variant epitopes provides opportunities to design effective vaccines and therapeutics that can target multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants. In conclusion, our study sheds light on the cross-reactivity of IgG epitopes and the potential for antibody-mediated enhancement in the context of SARS-CoV-2 and dengue virus infections. This knowledge has important implications for understanding the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and developing strategies to combat the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

6. Patents

Patent applications have been filed on 5 June 2020 on epitope targeting SARS-CoV-2 and construction of chimeric proteins [provisional patent applications BR BR1120210214011 (Brazil); US17638108 (U.S.A.); EP4039696 (Europa); CN114258399 (China); IN2022170 04847 (India)]. D.W.P-Jr.; A.M.D.; P.N-P. and S.G.D-S., Oswaldo Cruz Foundation).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1,

Table S1: IgG epitopes mapped for SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein using a pool of sera from patients with COVID-19 disease and cross-reactivity against DENV serotypes 1-4 (Taxid: 12637);

Figure S1: (A) Signal intensity of the reactivity of the peptides with IgG antibodies. (B) List of Spike protein (P0DTC2

) synthetic peptides and position in the cellulose membrane of SPOT synthesis. The overlapping of positive peptides defined by the epitopes is labeled in red. Figure S2: Sequence logos for spike protein cross-reactive DENV-identified sequences in Sars-CoV-2 variants of concern (Wuhan [wild type], Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma, Omicron BA.1, Omicron BA.2, Omicron BA.2.12.1, Omicron BA.4, Omicron BA.5) showing residues conservation. The selected amino acid sequence is shown on X-axis. The height of each letter on the Y-axis indicates its relative frequency. N, N-terminal end; C, C-terminal end;

Figure S3: Multiple sequence alignment of Sars-CoV-2 Spike protein [P0DTC2] and endemic coronaviruses. Identified cross-reactive sites (yellow), correspondent identical residues (red) in coronaviruses (Sars-CoV-1 [P59594], MERS-CoV [K9N5Q8], HCoV-OC43 [P36334], HCoV-NL63 [Q6Q1S2], HCoV-HKU1 [Q14EB0], HCoV-229E [P15423], BatCoV-RaTG13 [A0A6B9WHD3]), similar amino acids (gray) were highlighted. Analysis was performed using MEGA11 software and alignment using the MUSCLE algorithm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.D-S. and C.M.M.; Methodology, G.C.L., J.R.T, P.N-P.; Data analysis and curation, G.C.L, D.C.B-H., T.M.L.S. and S.G.D-S.; Software, G.C.L.; Original draft, G.C.L.; Review and editing, D.W.P. and S.G.D-S.; Project administration, C.M.M., S.G.D.-S.; Funding acquisition, C.M.M. and S.G.D.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Carlos Chagas Filho Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro/FAPERJ (#110.198-13) and the Brazilian Council for Scientific Research (CNPq, #467.488/2014-2 and 301744/2019-0). Funding was also provided by FAPERJ (#210.003/ 2018) through the National Institutes of Science and Technology Program (INCT) to Carlos M. Morel (INCT-IDPN).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Oswaldo Cruz Institute/FIOCRUZ (CAAE:49971421.8.0000.5248), the University of Estacio de Sá (CAAE: 3309 0820.8. 0000.5284) and UNIGRANRIO (CAAE: 21362220.1.0000.5283) study center ethics committee and conducted under good clinical practice and applicable regulatory requirements, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institute of Quality Control, FIOCRUZ, R.J., Brazil, for the MALDI-TOF analysis. P.N-P. and G.C.L. are fellows from CAPES/CDTS-FIOCRUZ.

Conflicts of Interest

The remaining authors not included in the patents declare no competing interests. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

References

- Hadj Hassine, I. Covid-19 vaccines and variants of concern: A review. Rev Med Virol 2022, 32, e2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Krüger, N.; Schulz, S.; Cossmann, A.; Rocha, C.; Kempf, A.; Nehlmeier, I.; Graichen, L.; Moldenhauer, A.S.; Winkler, M.S.; et al. The Omicron variant is highly resistant against antibody-mediated neutralization: Implications for control of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell 2022, 185, 447–456.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; Lam, E.C.; St Denis, K.; Nitido, A.D.; Garcia, Z.H.; Hauser, B.M.; Feldman, J.; Pavlovic, M.N.; Gregory, D.J.; Poznansky, M.C.; et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell 2021, 184, 2372–2383.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladner, J.T.; Henson, S.N.; Boyle, A.S.; Engelbrektson, A.L.; Fink, Z.W.; Rahee, F.; D'ambrozio, J.; Schaecher, K.E.; Stone, M.; Dong, W.; et al. , Epitope-resolved profiling of the SARS-CoV-2 antibody response identifies cross-reactivity with endemic human coronaviruses. Cell Rep Med 2021, 2, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyiam, K.; Phoolcharoen, W.; Butkhot, N.; Srisaowakarn, C.; Thitithanyanont, A.; Auewarakul, P.; Hoonsuwan, T.; Ruengjitchatchawalya, M.; Mekvichitsaeng, P.; Roshorm, Y.M. Immunodominant linear B cell epitopes in the spike and membrane proteins of SARS-CoV-2 identified by immunoinformatics prediction and immunoassay. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 20383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.L.; Chao, C.H.; Lai, Y.C.; Hsieh, K.H.; Wang, J.R.; Wan, S.W.; Huang, H.J.; Chuang, Y.C.; Chuang, W.J.; Yeh, T.M. Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 S1-RBD cross-react with dengue virus and hinder dengue pathogenesis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 941923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.M.; Ansari, A.M.; Frater, J.; Klenerman, P.; Dunachie, S.; Barnes, E.; Ogbe, A. The impact of pre-existing cross-reactive immunity on SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccine responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 23, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Smatti, M.K.; Ouhtit, A.; Cyprian, F.S.; Almaslamani, M.A.; Thani, A.A.; Yassine, H.M.; Thomas, S. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (A.D.E.) and the role of the complement system in disease pathogenesis. Mol Immunol 2022, 152, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Silva, I.T.; Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, Z.; et al. enhancement versus neutralization by SARS-CoV-2 antibodies from a convalescent donor associates with distinct epitopes on the RBD. Cell Rep 2021, 34, 108699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuya, K.; Hattori, T.; Saito, T.; Takadate, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Furuyama, W.; Marzi, A.; Ohiro, Y.; Konno, S.; Hattori, T.; et al. Multiple routes of antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e0155321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Song, S.; Hao, Y.; Luo, F.; Wu, R.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Li, T.; Hu, C.; Li, S.; et al. , Neutralizing antibodies from the rare convalescent donors elicited antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 variants infection. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 952697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, F. Evolving understanding of antibody-dependent enhancement (A.D.E.) of SARS-CoV-2. Front Immunol 2022, 112, 1008285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigan-Womas, I.; Spadoni, J.L.; Poiret, T.; Taïeb, F.; Randrianarisaona, F.; Faye, R.; Mbow, A.A.; Gaye, A.; Dia, N.; Loucoubar, C.; et al. Linear epitope mapping of the humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 in two independent African cohorts. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyiam, K.; Phoolcharoen, W.; Butkhot, N.; Srisaowakarn, C.; Thitithanyanont, A.; Auewarakul, P.; Hoonsuwan, T.; Ruengjitchatchawalya, M.; Mekvichitsaeng, P.; Roshorm, Y.M. Immunodominant linear B cell epitopes in the spike and membrane proteins of SARS-CoV-2 identified by immunoinformatics prediction and immunoassay. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 20383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, W.A.; Kamath, K.; Bozekowski, J.; Baum-Jones, E.; Campbell, M.; Casanovas-Massana, A.; Daugherty, P.S.; Dela Cruz, C.S.; Dhal, A.; Farhadian, S.F.; et al. High-resolution epitope mapping and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in large cohorts of subjects with COVID-19. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, F. Recent advances in nanotechnology-based COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutic antibodies. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 1054–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, P. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Han, X.; Yan, J. Structure-based neutralizing mechanisms for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022, 11, 2412–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, L.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Walls, A.C.; Beltramello, M.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Pinto, D.; Rosen, L.E.; Bowen, J.E.; et al. Mapping neutralizing and immunodominant sites on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike receptor-binding domain by structure-guided high-resolution serology. Cell 2020, 183, 1024–1042.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Peng, W.J.; Kuo, B.S.; Ho, Y.H.; Wang, M.S.; Yang, Y.T.; Chang, P.Y.; Shen, Y.H.; Hwang, K.P. Toward a pan-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine targeting conserved epitopes on Spike and non-spike proteins for potent, broad and durable immune responses. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19, e1010870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Yuan, L.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Qi, R.; Jiang, Y.; et al. The neutralizing breadth of antibodies targeting diverse conserved epitopes between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2022, 119, e2215628119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannar, D.; Saville, J.W.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, X.; Marti, M.M.; Srivastava, S.S.; Berezuk, A.M.; Zhou, S.; Tuttle, K.S.; Sobolewski, M.D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: spike protein mutational analysis and epitope for broad neutralization. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Park, Y.J.; Beltramello, M.; Walls, A.C.; Tortorici, M.A.; Bianchi, S.; Jaconi, S.; Culap, K.; Zatta, F.; De Marco, A.; et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature 2020, 583, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, L.; Misasi, J.; Pegu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Harris, D.R.; Olia, A.S.; Talana, C.A.; Yang, E.S.; Chen, M.; et al. , Structural basis for potent antibody neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants including B.1.1.529. Science 2022, 376, eabn8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, L.B.; Tedla, N.; Bull, R.A. Broadly-neutralizing antibodies against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 752003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Sauer, M.M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Low, J.S.; Tortorici, M.A.; Housley, M.P.; Noack, J.; Walls, A.C.; Bowen, J.E.; Guarino, B.; et al. Broad betacoronavirus neutralization by a stem helix–specific human antibody. Science 2021, 373, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.S.; Jerak, J.; Tortorici, M.A.; McCallum, M.; Pinto, D.; Cassotta, A.; Foglierini, M.; Mele, F.; Abdelnabi, R.; Weynand, B.; et al. ACE2-binding exposes the SARS-CoV-2 fusion peptide to broadly neutralizing coronavirus antibodies. Science 2022, 377, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacon, C.; Tucker, C.; Peng, L.; Lee, C.D.; Lin, T.H.; Yuan, M.; Cong, Y.; Wang, L.; Purser, L.; Williams, J.K.; et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies target the coronavirus fusion peptide. Science 2022, 377, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrock, E.; Fujimura, E.; Kula, T.; Timms, R.T.; Lee, I.H.; Leng, Y.; Robinson, M.L.; Sie, B.M.; Li, M.Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. , Viral epitope profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals cross-reactivity and correlates of severity. Science 2022, 370, eabd4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaago, M.; Rähni, A.; Pupina, N.; Pihlak, A.; Sadam, H.; Tuvikene, J.; Avarlaid, A.; Planken, A.; Planken, M.; Haring, L.; et al. Differential patterns of cross-reactive antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein detected for chronically ill and healthy COVID-19 naïve individuals. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 16817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Bhattacharjee, S. Dengue virus: epidemiology, biology, and disease etiology. Can J Microbiol 2021, 67, 687–70231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasar, S. , Rashid, N.; Iftikhar, S. Dengue proteins with their role in pathogenesis, and strategies for developing an effective anti-dengue treatment: A review. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanroye, F.; Bossche, D.V.D.; Brosius, I.; Tack, B.; Esbroeck, M.V.; Jacobs, J. COVID-19 antibody detecting rapid diagnostic tests show high cross-reactivity when challenged with pre-pandemic malaria, schistosomiasis, and dengue samples. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, H.; Mallick, A.; Roy, S.; Sukla, S.; Basu, K.; De, A.; Biswas. S. Archived dengue serum samples produced false-positive results in SARS-CoV-2 lateral flow-based rapid antibody tests. J Med Microbiol 2021, 70, 001369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.L.; Chao, C.H.; Lai, Y.C.; Hsieh, K.H.; Wang, J.R.; Wan, S.W.; Huang, H.J.; Chuang, Y.C.; Chuang, W.J.; Yeh, T.M. Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 S1-RBD cross-react with dengue virus and hinder dengue pathogenesis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 941923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Gresh., L.; Halloran., M.E.; Mercado, J.C.; Kuan, G.; Gordon, A.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science 2017, 358, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, A.; Imad, H.A.; Phumratanaprapin, W.; Phadungsombat, J.; Konishi, E.; Shioda, T. Antibody-dependent enhancement representing in vitro infective progeny virus titer correlates with the viremia level in dengue patients. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Luedtke, A.; Langevin, E.; Zhu, M.; Bonaparte, M.; Machabert, T.; Savarino, S.; Zambrano, B.; Moureau, A.; Khromava, A.; et al. Effect of dengue serostatus on dengue vaccine safety and efficacy. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, O.; Nechipurenko, Y.; Lagutkin, D.; Yegorov, Y.E.; Kzhyshkowska, J. SARS-CoV-2 infection of phagocytic immune cells and COVID-19 pathology: Antibody-dependent as well as independent cell entry. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1050478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, C.; Crespo, Â.; Ranjbar, S.; de Lacerda, L.B.; Lewandrowski, M.; Ingber, J.; Parry, B.; Ravid, S.; Clark, S.; Schrimpf, M.R.; et al. FcγR-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection of monocytes activates inflammation. Nature 2022, 606, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percivalle, E.; Sammartino, J.C.; Cassanitim, I.; Arbustinim, E.; Urtism, M.; Smirnovam, A.; Concardim, M.; Belgiovinem, C.; Ferrari, A.; Lilleri, D.; et al. Macrophages and monocytes: “Trojan Horses” in COVID-19. Viruses 2021, 13, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, B.K.; Francisco, E.B.; Yogendra, R.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Hall, E.; Herrera, M.; Parikh, P.; Guevara-Coto, J.; et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 protein in CD16+ monocytes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 months post-Infection. Front Immunol 2022, 12, 746021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craddock, V.; Mahajan, A.; Spikes, L.; Krishnamachary, B.; Ram, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Chen, L.; Chalise, P.; Dhillon, N.K. Persistent circulation of soluble and extracellular vesicle-linked Spike protein in individuals with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e28568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, E.E.; Shioda, T. SARS-CoV-2 Related antibody-dependent enhancement phenomena in vitro and in vivo. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Jiang, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, M.; Jiao, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement (A.D.E.) of SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviral infection requires FcγRIIB and virus-antibody complex with bivalent interaction. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuya, K.; Hattori, T.; Saito, T.; Takadate, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Furuyama, W.; Marzi, A.; Ohiro, Y.; Konno, S.; Hattori, T.; et al. , Multiple routes of antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e0155321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmeriya, S.; Kumar, A.; Karmakar, S.; Rana, S.; Singh, H. Neutralizing antibodies and antibody-dependent enhancement in COVID-19: A perspective. J Indian Inst Sci 2022, 102, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Edwards, R.J.; Manne, K.; Martinez, D.R.; Schäfer, A.; Alam, S.M.; Wiehe, K.; Lu, X.; Parks, R.; Sutherland, L.L.; et al. , In vitro and in vivo functions of SARS-CoV-2 infection-enhancing and neutralizing antibodies. Cell 2021, 184, 4203–4219.e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanathan, M.; Afkhami, S.; Smaill, F.; Miller, M.S.; Lichty, B.D.; Xing, Z. Immunological considerations for COVID-19 vaccine strategies. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikewaki, N.; Kurosawa, G.; Levy, G.A.; Preethy, S.; Abraham, S.J.K. Antibody-dependent disease enhancement (ADE) after COVID-19 vaccination and beta-glucans as a safer strategy in management. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2427–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Gomes, L.R.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; Pina, J.C.; Silva, F.R. Identification of linear B epitopes liable for the protective immunity of diphtheria toxin. Vaccines 2021, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.R.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; De-Simone, S.G. Identification of linear B epitopes of pertactin of Bordetella pertussis induced by immunization with whole and acellular vaccine. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6251–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Science 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).