1. Introduction

Water pollution poses a significant threat to ecosystems that are responsible for causing algal blooms and affecting human health worldwide [

1]. Conventional water treatment in watersheds involves a series of processes—including coagulation, sedimentation, filtration, disinfection, pH adjustment, activated carbon treatment, and aeration are often costly. FTWs offer a sustainable alternative by harnessing the natural purification abilities of aquatic plants to remove excess nutrients such as nitrates and phosphates from water bodies [

2]. These engineered systems typically consist of buoyant mats made using different materials that support vegetation, with roots extending into the water column to facilitate nutrient uptake and promote beneficial microbial processes. Unlike traditional treatment systems, FTWs require less surface area, making them particularly suitable for urban environments and areas with limited space. Various macrophytes, including

Vetiveria zizani-oides, Juncus effusus and

Typha latifolia enhance microbial colonization and activity while also contributing to the de-composition of organic matters. Efficient pollutant removal relies on maintaining contact between the plant roots and the polluted water. Furthermore, FTWs are adaptable to changing hydrological conditions and operate year-round in diverse climatic regions. In addition to nutrient removal, FTWs have demonstrated the ability to retain heavy metals, reduce pathogen loads, and increase dissolved oxygen (DO) levels [

3]. They provide an integrated approach to water quality improvement through sediment interaction, biofilm activity, and phytoremediation. Given their adaptability and environmentally friendly nature, FTWs have attracted increasing interest over the past decade as a promising method for pollution mitigation [

3,

4].

Further, FTWs are highly adaptable and suitable for a wide range of aquatic environments. They play a crucial role in improving water quality while simultaneously enhancing the aesthetic appeal and ecological health of degraded systems [

5,

6]. However, optimizing FTWs performance requires a deep understanding of key factors including climatic conditions, plant selection, and system architecture. This review highlights new analytical techniques for monitoring water quality and plant performance. Further, this review provides a comprehensive overview of current research on FTWs, with a focus on the critical elements that influence their effectiveness in water purification. We evaluate recent advancements in system design and the importance of selecting plant species based on their characteristics. The study aims to synthesize insights from various studies, identify existing knowledge gaps, and outline future research directions to support the development of more effective FTWs for improved water quality management a utilization of harvested plant biomass.

This review presents a comprehensive framework for utilizing FTWs as nature-based solutions for watershed bioremediation, integrating ecological principles with engineering design. It evaluates the advantages of FTWs compared to other treatment systems, emphasizing their adaptability, modularity, and minimal land requirements particularly beneficial in urban settings. The manuscript explores FTWs’ climate resilience, design innovations, and the application of advanced analytical tools to monitor nutrient and heavy metal removal. Standardized metrics are proposed to assess plant growth and overall system performance, with particular focus on selecting site-specific plant species and promoting beneficial plant–microbe interactions. FTWs are demonstrated to be effective in a wide range of water purification contexts, including the treatment of stormwater, industrial runoff, and greywater. This work highlights the potential of FTWs to contribute meaningfully to sustainable water management and ecosystem restoration.

1.1. Background and Rationale for FTWs

1.1.1. Impacts of Polluted Water and Need for Nature-Based Solutions

Water pollution from both natural and anthropogenic sources continues to degrade aquatic ecosystems globally. Erosion, agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, and urban stormwater (

Figure 1) introduce a wide range of contaminants into waterbodies. These pollutants include nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus), suspended solids (e.g., sediments), heavy metals (e.g., lead, mercury, and cadmium), organic pollutants (e.g., oils, pesticides, industrial chemicals), and biological contaminants (e.g., pathogens from sewage and animal waste) [

7,

8]. These substances not only threaten biodiversity but also pose serious risks to human health, particularly through the bioaccumulation of persistent pollutants such as heavy metals and pharmaceuticals [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Heavy metals like lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and chromium (Cr) often enter aquatic system via mining, metal processing, and industrial discharges. Meanwhile, pharmaceuticals have emerged as a growing environmental concern due to their persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation potential. Drugs used in both human and veterinary medicine, along with their metabolites, commonly reach water bodies through wastewater discharge. Compounds such as antibiotics and hormones have been detected in surface water, groundwater, and even treated drinking water, where they may exert ecotoxicological effects [

14,

15,

16]. A Swedish study found that only 8% of pharmaceuticals were biodegradable, while 23% showed a high potential for bioaccumulation [

17]. Common pharmaceutical pollutants included antibiotics, analgesics, antidepressants, hormones, and anti-inflammatory drugs, many of which posed environmental risks even at trace concentrations. Moreover, nutrient enrichment, combined with climate-driven shifts in temperature and light availability, has intensified the frequency and severity of harmful algal blooms (HABs) (

Figure 2) [

18,

19,

20]. These blooms disrupt aquatic food webs, deplete DO, and impact the nutrient uptake efficiency of aquatic vegetation, including species used in FTWs.

Conventional treatment methods such as coagulation, filtration, and disinfection are widely used but present several limitations, including high operational costs, chemical consumption, and the generation of sludge. More advanced technologies such as Micro-Air Flotation (MAF), Activated Carbon Adsorption (ACD), and Bio-Granulation with Chemical Precipitation (BGCP) (

Figure 3,

Table 1) offer more targeted pollutant removal.

However, these methods may face challenges related to scalability and long-term sustainability, especially in decentralized or rural settings. In this context, there is a growing need for integrated solutions that not only remove nutrients and heavy metals but also enhance habitat diversity and improve aesthetic value. Detailed description of the MAF, ACD, and BGCP mechanisms are provided in the appendix section (Appendix A1.1–A1.3).

1.2. Constructed Wetlands (CWs) Treatment

CWs are engineered systems that replicate natural wetland functions to treat watershed wastewater [

29,

30]. Using vegetation, soil, and microbial communities, they remove contaminants such as nutrients, solids, pathogens, and some heavy metals through processes like filtration, sedimentation, plant uptake, and microbial degradation. Commonly used for agricultural runoff, stormwater, and domestic wastewater, they offer benefits like low operating costs, energy efficiency, biodiversity support, and resilience to fluctuating flows. However, they require significant land area, have longer retention times, may attract mosquitoes, and can be less effective in cold climates or under high hydraulic loads. Regular maintenance is also needed to manage vegetation and prevent clogging.

2. About FTWs

FTWs are innovative water treatment systems that combine natural biological processes with engineered structures to remediate polluted water bodies such as lakes, ponds, and rivers [

31,

32]. These systems consist of buoyant platforms often made from recycled plastic or foam that support wetland plants with roots suspended freely in the water column (

Figure 4). The extensive root systems provide large surface areas for microbial communities that facilitate nitrification, denitrification, and the breakdown of organic pollutants. Additionally, plants absorb nutrients and heavy metals through phytoremediation, helping to reduce eutrophication and algal blooms [

33]. Beyond pollutant removal, FTWs trap suspended solids to improve water clarity, create microhabitats that enhance aquatic biodiversity, and provide shading that moderates water temperature and suppresses algal growth. FTWs are cost-effective, space-efficient, adaptable to various climates and water bodies, and contribute to both ecological restoration and aesthetic enhancement of urban and rural environments.

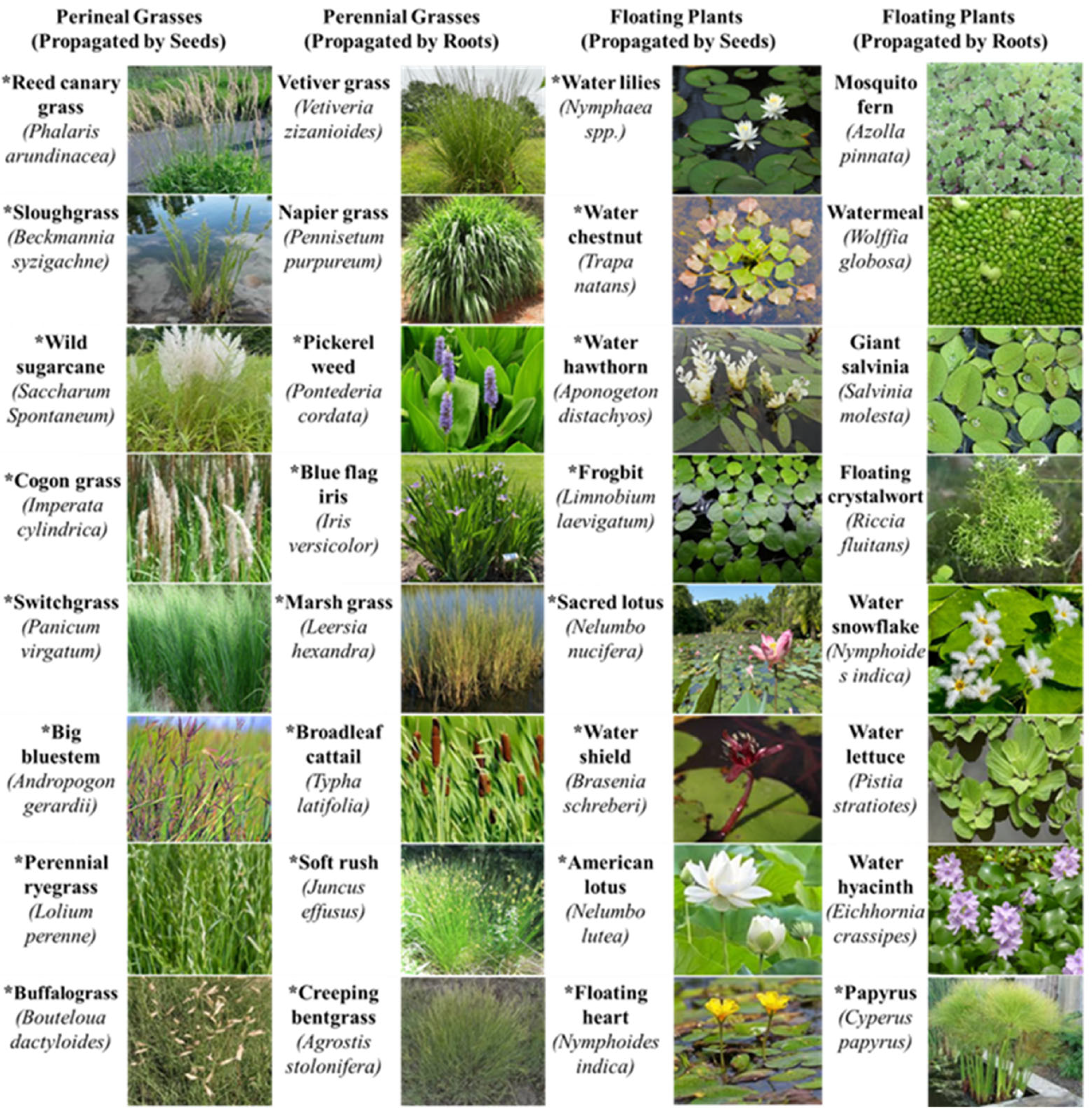

The effectiveness of FTWs largely depends on the selection of plant species (

Figure 5). While some species propagate exclusively through seeds, while others can reproduce via both seeds and root transplants. Among them, perennial grasses that are well-acclimated to local environmental conditions have proven particularly effective in water remediation. Since their development in the 1980s, FTWs have employed a range of plant species categorized mainly as (i) free-floating and (ii) emergent plants [

34]. Research indicates that higher species richness and diversity in growth forms—such as combinations of elongated, broad-leaved, and larger plants—can significantly boost the removal of total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP). Mixed planting strategies enhance system resilience and performance while improving the visual and ecological quality of urban wetlands. This integrated approach supports sustainable water purification and ecosystem restoration. Ongoing studies continue to deepen our understanding of plant–pollutant interactions, advancing the efficiency and effectiveness of FTWs.

2.1. Free-Floating Macrophyte Wetland

Free-floating macrophyte wetlands use aquatic plants that float on the surface without anchoring to the sediment. Common species include water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), Frogbit (

Hydrocharis dubia), and duckweed (

Lemna minor) [

35,

36,

37]. Their floating nature allows them to adapt to varying water depths, making these wetlands effective for treating stormwater, polluted natural water, and various wastewater. However, their free-floating nature poses challenges like being hard to contain, easily dispersed by water and wind, and potentially invasive. These issues make free-floating macrophyte wetlands less commonly used to treat natural or stormwater bodies.

2.2. Floating Emergent Macrophyte Wetland

Floating emergent macrophyte wetlands feature emergent plants rooted in mats or buoyant artificial beds that float on the water surface [

38]. Common species include reed (Phragmites australis), cattail (

Typha sp.), and canna (

Canna sp.). Air pockets within these plants help them float and enhance oxygen supply to submerged biomass, accelerating aerobic degradation. Plant selection should consider local regulations and climate, as some species may be invasive or unsuitable in certain regions, while tropical climates may require different plants. The floating beds and dense root mats stabilize plant placement, reduce displacement by wind or currents and promote sedimentation by minimizing turbulence. Additionally, shading from the beds helps control algal growth, though excessive coverage can lower DO levels. These wetlands work well for varying flow conditions, but their efficiency may decrease as water depth increases because more flow bypasses the root-biofilm zone.

2.3. Submerged Macrophyte Wetland

Submerged macrophyte wetlands are characterized by aquatic plants that grow entirely beneath the water surface, with their roots anchored in the substrate [

40]. Common species include eelgrass (Zostera marina), pondweed (

Potamogeton sp.), and contrail (

Cera-tophyllum demersum). These systems support underwaater vegetation that enhance DO levels through photosynthesis, promoting aerobic microbial activity essential for breaking down organic pollutants, thereby promoting aerobic microbial activity critical for the degradation of organic pollutants. By stabilizing sediments and reducing turbidity, submerged macrophytes significantly improve water clarity. Moreover, they create valuable habitats and food sources for aquatic fauna, contributing to increased biodiversity.

Functionally, submerged macrophyte wetlands contribute to the removal of excess nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic contaminants, playing a vital role in nutrient cycling and water purification [

40]. These plants also facilitate oxygen diffusion into the sediment layer, enhancing microbial activity and accelerating pollutant breakdown, which supports overall ecosystem balance and resilience. To maintain the long-term efficacy of FTWs and prevent decaying plant matter from becoming a secondary source of pollution, timely harvesting of vegetation is essential. Harvesting should be conducted before the onset of senescence to ensure that assimilated nutrients are permanently removed from the system rather than released back into the water column upon plant decay. Systematic monitoring of plant growth and harvesting schedules is therefore critical. This includes recording biomass accumulation, nutrient content, and seasonal growth trends to identify optimal harvesting windows. Such data not only informs effective management practices but also improves the operational efficiency and sustainability of FTWs over time. Integrating harvest planning into the design and management of FTWs can significantly enhance pollutant removal rates while reducing maintenance burdens and ecological risks [

41,

42].

Additionally, careful plant species selection is critical to balancing remediation efficiency with environmental safety. While fast-growing, non-native species may demonstrate high nutrient uptake capabilities, they also pose a significant risk of becoming invasive if released into surrounding ecosystems. To mitigate such risks, the use of native or non-invasive species should be prioritized. This should be supported by proper containment strategies and routine ecological monitoring. Utilizing a diverse mix of locally adapted native species can further boost pollutant removal performance while minimizing the likelihood of biological invasions, thereby enhancing both system functionality and environmental protection [

43].

2.4. Comparative Analysis: FTWs vs. Other Nature-Based Solutions (NBS)

NBS for improving water quality includes systems such as CWs, vegetated swales, riparian buffers, and FTWs [

44,

45]. These systems harness natural processes including plant uptake, microbial activity, and sedimentation to remove pollutants from water bodies. Among them, FTWs offer distinct advantages and limitations. They are especially well suited for urban or space-limited environments where land constraints hinder the use of traditional CWs. Their modular design enables flexible installation in stormwater ponds, reservoirs, and canals without major alterations to existing hydrology, making them ideal for retrofitting and enhancing current infrastructure. However, FTWs may be less effective in high-flow systems where short hydraulic retention time reduces treatment efficiency (

Table 2). In such contexts, hybrid or complementary NBS approaches may be required to meet water quality goals. Despite these limitations, FTWs represent a valuable component of the NBS toolkit, particularly for decentralized applications and infrastructure upgrades. A clear understanding of their strengths and constraints is essential for designing integrated, site-specific strategies that support sustainable and resilient water management.

2.5. Advantages and Limitations of FTWs System

FTW offer an efficient, space-saving solution for improving water quality, as they can be installed directly on existing water bodies without the need for additional land. They effectively remove nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as heavy metals, through a combination of plant uptake, microbial activity, and sedimentation. Their modular design enables flexible scaling to fit various site conditions, while also enhancing biodiversity and providing aesthetic benefits that can help build public support. Despite these advantages, FTWs also present several limitations. Their performance is influenced by factors such as plant species selection, seasonal variability, and pollutant loading rates. Regular maintenance—including timely plant harvesting and routine structural inspections—is critical to ensuring long-term functionality. In high-flow environments, reduced hydraulic retention time can significantly impair treatment effectiveness. Furthermore, most existing studies emphasize short-term performance, leaving uncertainties about long-term durability and efficacy. Compared to passive systems such as riparian buffers, FTWs may also involve higher installation and maintenance costs. Nevertheless, FTWs remain a valuable and adaptable component of integrated water management strategies, particularly when implemented alongside other nature-based solutions to enhance overall system resilience and performance.

2.6. Climatic Adaptability and Resilience of FTWs

While FTWs have shown adaptability across a range of climate zones, their long-term stability and performance under extreme climatic conditions remain insufficiently addressed in the current literature. These systems have been deployed in both temperate and tropical regions; however, extreme weather events—such as prolonged droughts, intense rainfall, freezing temperatures, and heatwaves—can significantly impact their structural integrity, vegetation health, and treatment efficacy [

49]. In cold climates, freezing temperatures may damage plant tissues, suppress microbial activity, and cause ice heave, potentially dislodge floating mats or compromise anchoring mechanisms. In hot or arid environments, elevated evapotranspiration and water loss can lead to plant desiccation, reducing biomass productivity and nutrient uptake. Additionally, warm temperatures often encourage algal blooms, which compete with plant roots for nutrients and may impair system performance. In coastal or flood-prone areas, storm surges and high winds pose increase the risks of structural displacement or damage to the floating platforms.

2.7. FTWs Treatment on Different Sources of Wastewater

2.7.1. Stormwater Runoff

One major advantage of floating wetland treatment over traditional methods is its adaptability to changing flow conditions and fluctuating water depths, making it well suited for treating stormwater runoff [

50]. Stormwater runoff carries pollutants such as lawn and garden fertilizers, pet waste, sediment and heavy metals like chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, cadmium, and lead which accumulate on paved surfaces from vehicle emissions. A study [

51] of FTWs treating runoff from a 7.46 ha urban residential area demonstrated significant reductions in Total Suspended Solids (TSS) and TP despite the system small footprint, though pollutant removal, especially TN, varied between rainfall events due to low and fluctuating influent concentrations.

2.7.2. Industrial Runoff

Runoff from industrial activities often contains heavy metals, toxic chemicals, oils, and textile pollutants, making FTWs a suitable treatment option [

52]. Over 50% of industrial effluents treated by FTWs are textile and oily wastewater, which are typically high in organics and suspended solids. The effectiveness of FTWs depends largely on plant choice. For example, vetiver grass has been shown to increase pH and remove heavy metals from acid mine drainage, while water hyacinth is also effective in heavy metal removal. FTWs have been used in effluents from paper, batik, and food industries, showing their versatility. They effectively remove pollutants from textile wastewater, which contain dyes, pigments, and heavy metals. Specific bacterial strains can enhance dye degradation, reducing color and toxicity. FTWs are used to treat oily wastewater. Vetiver grass (

Chrysopogon zizanioides) in FTWs reduced oil content chemical oxygen demand (COD), and biological oxygen demand (BOD) [

53].

2.7.3. Greywater

Greywater generated from household activities like bathing, handwashing, laundry, and dishwashing differs from blackwater that it contains significantly less contamination from human waste [

54]. It accounts for about 65% of the total domestic wastewater, with roughly half classified as polluted due to the presence of organic matter, detergents, and microbes. Greywater, with its lower contamination levels, has significant reuse potential. FTWs can remove over 50% of COD and BOD from domestic wastewater and effectively eliminate TN, NH₄⁺-N, TP, and TSS. However, nutrient removal efficiency can vary depending on plant species, wastewater composition, and environmental conditions. FTWs are suitable for treating a wide range of greywater and similar wastewaters, offering a sustainable, nature-based solution for water recycling through plant–microbe interactions.

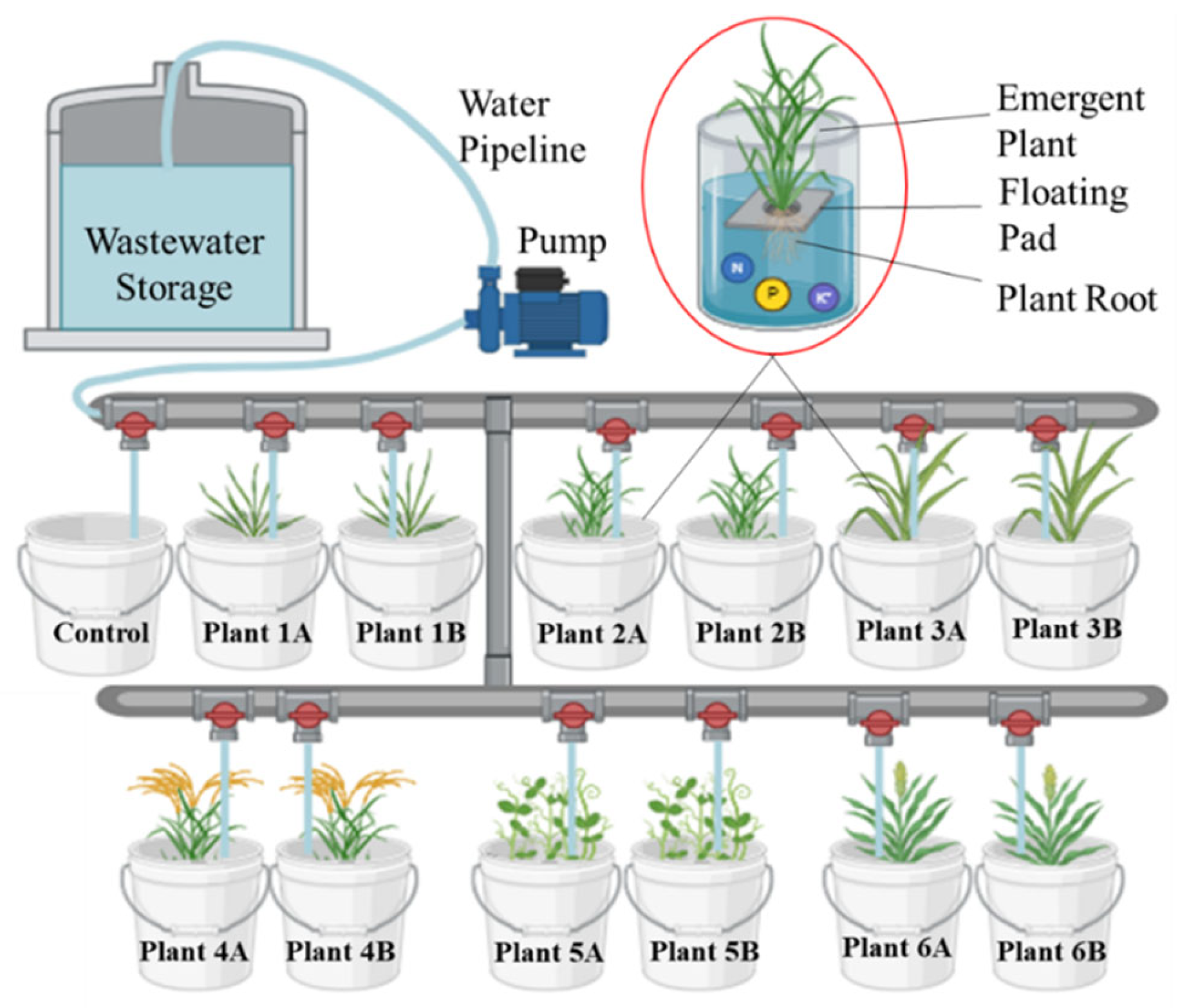

3. Experimental Workflow and Design of FTWs

3.1. Indoor and Outdoor Experiments

FTWs can be tested indoors and outdoors to assess environmental impacts on plant growth and nutrient remediation. Variables like temperature, light, nutrient availability, and seasonal changes affect FTWs performance. Indoor mesocosms provide precise control over these factors, aiding in optimizing FTWs design for eutrophic waters. In one indoor study [

55], four treatments were conducted using polycarbonate microcosms (14.3 cm × 30.5 cm) simulating wetland conditions:

Vegetation Presence: Floating vegetation (FV) vs. without floating vegetation (NFV) (n = 3 each).

Gas and Light Control: FV microcosms with inhibited gas exchange, foil covers (light reduction), and plastic traps (gas restriction).

Nitrogen Loading: TDN increased from 1.4 to 4.1 mg N L⁻¹ in FV + N and NFV + N (n = 3 each), with control groups included.

Temperature Elevation: FV and NFV with/without a 5 °C increase (n = 3 each).

Results showed FV microcosms had significantly higher denitrification rates (302 ± 45 vs. 63 ± 13 µmol N m⁻² h⁻¹) and nitrogen retention (203 ± 19 µmol N m⁻² h⁻¹; 72 ± 4%) than NFV (170 µmol N m⁻² h⁻¹; 62 ± 4%). This was attributed to enhanced DO dynamics associated with plant presence. Nitrogen retention was calculated using Equation (1):

where TDN

in and TDN

out are defined as the concentrations of TDN for inflow and outflow water. As for measurements of greenhouse gas production rates, there were no significant differences found.

Higher temperatures reduced denitrification in NFV microcosms and decreased N₂O emissions in FV systems. Plant mats inhibited photosynthesis in FV microcosms, lowering DO levels and boosting denitrification. FV exposed to light exhibited reduced denitrification due to increased DO from photosynthesis. Nitrate removal showed no significant difference between light and dark FV microcosms, likely because dense plant mats naturally limit light penetration. Floating vegetation boosts nitrogen removal and maintains stable GHG emissions, showing the potential of CWs to improve water quality without increasing GHG outputs. Outdoor mesocosm experiments further support this, allowing precise control of variables like influent nutrient concentration, hydraulic retention time (HRT), and hydraulic loading rate (HLR). Nutrient removal was assessed using the following Equation (2):

This formula calculates weekly nutrient removal, with Ni as the initial load and Nf as the load after retention time. It also computes cumulative removal efficiency using the sum of all Ni and Nf values from the experiment weeks.

Outdoor mesocosm setups often utilize standard aquatic equipment such as water pumps, supply lines, hoses, drainage systems, and polyvinyl chloride piping to maintain functionality. In a related study, [

56] conducted a two-factor experiment using Myriophyllum aquaticum, testing three nutrient concentrations and three light intensity treatments (no shading, 30% shading, 60% shading). Their findings showed that higher light intensity and nutrient levels significantly boosted plant growth. Relative growth rate was calculated using the following Equation (3):

Here, W1(g) and W2(g) are the total weight per bucket on different days (i.e. D1 and D2). In essence, FTWs are studied under both controlled (indoor) and natural (outdoor) conditions to understand the efficacy of nutrient remediation of floating aquatic plants in different environments. Indoor experiments, with precise control over variables like nutrient levels, light intensity, and water quality, help researchers understand denitrification and nitrogen retention in FTWs. On the other hand, outdoor experiments simulate real-world conditions with natural fluctuations in light, temperature, and nutrients. Combining insights from both can lead to hybrid experimental designs that optimize FTWs performance for different environments, improving their effectiveness and sustainability across ecosystems

3.2. Floating Mat Types

The efficiency of FTWs in treating waters is largely determined by the design of floating mats, which support aquatic plants in removing nutrients and pollutants through their roots [

57]. BioHaven mats, made from lightweight polyurethane foam, removed 25% of TN and 4% of TP over 18 weeks. Beemats, made of durable polyethylene foam, achieved higher removal rates: 40% TN and 48% TP [

58]. Floating mats are made from materials like polyurethane and polyethylene foams, coconut coir fibers, recycled plastics, Poly vinyl chloride or high-density polyethylene meshes, and geotextile fabrics (

Figure 6). These materials affect buoyancy, durability, root penetration, nutrient absorption, and plant health, making their selection crucial for successful FTWs. Species like

Carex and

Typha excel at nitrogen removal, especially in cold climates [

59]. Mixed-species plantings improve nutrient uptake compared to monocultures, suggesting diverse plants enhance FTWs performance. Optimizing mat coverage and operational parameters further boost nitrogen removal, while mats promote floating vegetation coverage and enhance denitrification and nutrient retention.

Aeration increases DO and plant nitrogen uptake by up to 55%, but it paradoxically reduces N and P removal from water due to changes in microbial processes like denitrification. The plant effectiveness depends on interactions among plants, microbes, and water chemistry. It is crucial to select appropriate mat materials, plant species, coverage, and aeration strategies to optimize nutrient removal and plant growth in FTWs.

As climate change accelerates, future research on FTWs must prioritize enhancing their resilience to increasingly extreme and unpredictable environmental conditions. Elevated temperatures, freezing winters, prolonged droughts, and intensified storm events can all compromise the structural integrity and treatment performance of these systems. Addressing these challenges requires a multipronged approach. First, selecting plant species with high tolerance to both heat and cold is critical to maintaining consistent, year-round nutrient removal. Second, FTW structural designs should evolve to incorporate modular, flexible platforms engineered to withstand wind, wave action, and fluctuating water levels. The use of durable floating materials and adaptive anchoring systems will be essential for ensuring long-term operational stability. Furthermore, integrating predictive climate models with real-time monitoring technologies can support proactive management and timely structural adjustments. Advancing these strategies will help establish FTWs as climate-resilient components of sustainable water treatment systems in both ecological and urban environments.

3.3. Mat Thickness

Current research shows that mats about 1 cm thick effectively support the weight of floating aquatic plants in treatment wetlands and play a key role in nitrogen and phosphorus removal from simulated stormwater runoff [

60]. One study reported removal efficiencies of approximately to be 84% for TN and 75% for TP during spring to fall 2008, demonstrating the importance of optimal mat thickness. However, further investigation is needed to better understand how mat thickness directly affects nutrient removal and which mat properties are most critical for designing effective FTWs in varying environments. Given the need for scalable FTWs in large water bodies, mat thickness is a crucial factor influencing nutrient uptake.

3.4. Soil vs. Without Soil

The utilization of different soil types and overall nutrient availability within FTWs

significantly influences nutrient uptake and overall wetland performance. A study by [

61] evaluated the use of spent coffee grounds as a soil amendment in FTWs. Their mesocosm-scale study demonstrated that soil cups amended with spent coffee grounds significantly improved nitrate (NO3-N) removal efficiency. The study reported NO

3-N removal rates are as high as 90% compared to control setups without amendments. They calculated NO3-N removal rates by first calculating NO

3-N first-order removal rates. This first-order removal rate Equation (5).

where C

t is the final NO

3-N concentration (mg L

-1), C

o is the initial NO

3-N concentration (mg L

-1), t is time (d), and k is the removal rate (d

-1). Nitrate percent removals are represented by this Equation (5).

Increased carbon from coffee grounds enhances microbial activity and denitrification, aiding nitrate removal. One study [

62] found that nutrient-rich water reduces metal uptake efficiency. Zinc and copper removal rates were 28.4–57.3% and 1.0–19.7% in nutrient-rich water but increased to 44.9% and 81% in nutrient-deficient water. Using appropriate soils and amendments, like organic-rich soils or spent coffee grounds, can significantly enhance the removal of nitrogen, phosphorus, and metals, improving FTWs effectiveness.

3.5. Optimal Harvest Time and HRT

In a recently concluded study, detailed insights into the optimal harvest time for maximizing nutrient removal efficiency in FTWs using Pickerelweed (

Pontederia cordata) and Soft Rush (

Juncus effusus) have been reported [

63]. For

P. cordata, the highest N and P accumulation in roots occurred in August (307 g N and 30.5 g P), while the shoots reached peak nutrient levels in September (1,490 g N and 219.5 g P). This indicates that the optimal harvest period for

P. cordata spans late summer to early fall, August for roots and September for shoots. In the case of

J. effusus, maximum nutrient accumulation was observed in both roots (50 g N and 4.8 g P) and shoots (98 g N and 12.5 g P) during September. Thus, September is the ideal harvest time for

J. effusus. Harvesting these species before senescing, typically in mid- to late September, maximizes nutrient uptake and storage. This strategic timing is particularly important in United States Department of Agriculture Hardiness Zone 8a in the Southeastern United States, where timely harvesting can substantially enhance FTWs performance and improve water quality management.

HRT significantly influences nutrient removal and plant performance in FTWs. A pilot-scale wetland study with Eichhornia crassipes 82–95% TP removal efficiencies over 3, 7, and 10 days, with no significant differences [

64]. However, after accounting for sedimentation, the 3-day HRT system had the highest TP accumulation in plant biomass. TP removal was higher during the wet season, likely due to increased macrophyte growth from greater solar radiation. Minakshi et al. [

65] studied vertical subsurface flow CWs and observed 81.2% for TSS, 90.2% for BOD₅, 65.1% for TP, and 82.5% for NH₄-N at 12 hours. A study [

66] comparing sand and gravel filter media in vertical subsurface CWs for dairy wastewater found that longer HRT (12-48 hours) improved removal. At 48 hours, finer gravel achieved the highest removal rates: BOD (63.1%), COD (67.4%), and PO₄-P (57.8%). These findings underscore the importance of optimizing HRT and system design to enhance nutrient removal efficiency in FTWs and other constructed wetland systems.

3.6. Metrics for Assessing Plant Growth

Evaluating plant growth is crucial for assessing FTWs efficiency. A study found that longhair sedge (

Carex comosa) outperformed common spikerush (

Eleocharis palustris) in biomass production and root system development, resulting in better nutrient uptake and storage [

67]. A study [

68] tested monoculture and mixed-species FTWs with five macrophytes for nitrogen and phosphorus removal. Both strategies were effective, but Panicum virgatum had better nitrogen uptake in mixed plantings, indicating synergy, while

Iris ensata performed better alone, suggesting antagonism in mixtures. Biomass production and nutrient accumulation in plant tissues were key indicators of performance. Over 11 weeks, southern cattail (

Typha domingensis) showed superior root development and nutrient removal in a constructed FTWs, with TN and TP reductions of 4–31% and 8–15%, respectively, compared to lower rates in giant bulrush (

Schoenoplectus californicus) [

69]. A 16-month study [

70] on tall sedge (

Carex appressa) in urban stormwater FTWs found notable root growth and nutrient uptake. TN uptake was 20.2 ± 2.88 kg and 15.0 ± 2.07 kg in two systems, but phosphorus removal was limited by low water concentrations. Nutrient partitioning showed metals like aluminum and iron mostly accumulating in roots. Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of metrics such as biomass, root development, and nutrient storage in evaluating FTWs performance. Consistent increases in these parameters demonstrate the potential of FTWs to improve water quality through effective plant-mediated nutrient removal.

3.7. Impact of Different Mesocosm Designs

Effective mechanical design is vital for the success of floating aquatic plant systems and important factors are buoyancy, durability, stability, structural integrity, scalability, and modularity (

Figure 7).

3.7.1. Buoyancy

This is foundational for floating mats to support both plant biomass and any associated equipment. Commonly used buoyant materials include recycled plastics, foam, and synthetic fibers. Proper weight distribution is essential to avoid tilting or sinking, requiring accurate calculations of total system load and buoyant capacity.

3.7.2. Durability

This factor is equally important. Materials must resist degradation from prolonged exposure to water, UV radiation, and temperature fluctuations. UV-stabilized plastics are preferred for their resilience [

71], helping reduce maintenance by minimizing wear and tears over time.

3.7.3. Stability

External forces such as wind, waves, and fluctuating water levels require robust anchoring systems. These may include weighted anchors, flexible tethers, or mooring lines that accommodate water level changes [

72]. Additional design features like aerodynamic shapes, added ballast, and flexible yet resilient structures improve system performance during storms or high winds. For example, researchers developed floating islands anchored with four cinder blocks connected by metal chains [

73]. Each island included 5.75 cm diameter pre-drilled holes spaced 20 cm apart for planting 2.5 cm plugs (~225 plants per island). Protective fencing was installed to deter herbivory by Canada geese. Another study used a semi-rigid hose attached to a post 4.9 m from the shoreline and compared BioHaven and Beemats floating islands [

58]. A Port Marina project used Cork Floating Islands by Blue Master, anchored with cables, weights, and plastic clamps for tidal fluctuations. Similarly, a Lampedusa Island study showed offshore photo voltaic platforms' economic and structural viability, highlighting design parallels between floating wetlands and solar installations [

74].

3.7.4. Structural Integrity

Mats must support not only plant biomass but also maintenance personnel and equipment, requiring precise load-bearing calculations. The structure must strike a balance between flexibility (to absorb wave energy) and rigidity (to prevent sagging).

3.7.5. Design Geometry and Hydraulic Configurations

Computational fluid dynamics modeling can optimize floating pad positioning and pond inlet–outlet design. Analysis system Fluent simulations, validated by experiments, to identify the best configuration—a circular FTWs placed near the inlet with a center inlet side outlet—which achieved 94.8% pollutant removal [

75]. In contrast, far-side inlet–side outlet designs performed poorly due to flow short-circuiting. FTWs near inlets removed more pollutants (61.8%) compared to central (42.7%) or outlet positions (54.1%). Another study investigated the optimal spacing of FTWs in a channel system. The highest mass removal was achieved when FTWs were spaced between one and three times the root zone length, optimizing both root-zone flow and the number of FTWs [

76].

3.7.6. Scalability and Modularity

Modular designs enable easy addition or removal of units without requiring major changes to the existing infrastructure. Interconnectable modules facilitate maintenance and adaptability. By incorporating these design principles—buoyancy, durability, stability, structural integrity, and modularity, FTWs can be optimized for enhanced performance, longevity, and resilience. They represent a valuable solution for environmental management and sustainable agriculture.

3.8. Plant Selection Criteria for FTWs

The nutrient and heavy metal removal efficiency of FTWs is strongly influenced by plant species selection, as each species differs in pollutant uptake capacity, contaminant tolerance, and adaptability to hydroponic conditions [

77]. Ideal candidates should exhibit strong bioaccumulation potential for metals such as Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn. For example,

Carex pseudocyperus and

Carex riparia have demonstrated removal rates of up to 98–100% for these metals within just five days in hydroponic systems. Plants with extensive root systems and high biomass provide a larger surface area for microbial colonization and metal adsorption, thereby enhancing overall removal even if their individual root uptake efficiency is moderate. To ensure long-term functionality, species must also tolerate elevated contaminant concentration without experiencing significant physiological stress, minimizing the need for frequent replacement. Because FTW plants must thrive in waterlogged, low-soil environments, robust emergent macrophytes such as

Juncus effusus,

Phragmites australis, and

Typha latifolia are commonly used [

78]. Native, non-invasive species are generally preferred to promote local biodiversity and align with ecological and regulatory standards. In urban or public installations, aesthetic considerations and plant structure such as canopy height and form may also influence species selection.

3.9. Microbial Interactions in FTWs

Microbial communities play a crucial role in the bioremediation functions of FTWs. Microorganisms that colonize the rhizosphere and form biofilms on plant roots and floating substrates drive essential processes such as pollutant transformation, degradation, and immobilization. For instance, nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria convert ammonia to nitrate and subsequently reduce nitrate to nitrogen gas, thereby lowering nitrogen concentrations in aquatic systems. Similarly, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria enhances phosphorus bioavailability, facilitating greater uptake by plants. Certain microbial species also influence the redox state of heavy metals, transforming them into less toxic or less bioavailable forms. Sulfate-reducing bacteria, for instance, can precipitate toxic metals like cadmium and lead as insoluble metal sulfides. The physical structure of FTWs including dense root networks and porous floating media provides extensive surface area for microbial colonization, promoting the development of active biofilms. These biofilms function as microreactors, enhancing interactions between pollutants and microbial communities. Moreover, plants release exudates such as sugars, amino acids, and phenolic compounds that stimulate microbial activity. In return, microbes support plant nutrient uptake and bolster plant resilience under environmental stress. This mutualistic relationship enhances both the ecological stability and pollutant removal efficiency of FTWs. Research has shown that microbial diversity and abundance are strong predictors of FTW performance. Consequently, strategies such as targeted microbial inoculation, bioaugmentation, and substrate modification are being explored to further optimize treatment efficiency and long-term system stability [

79,

80].

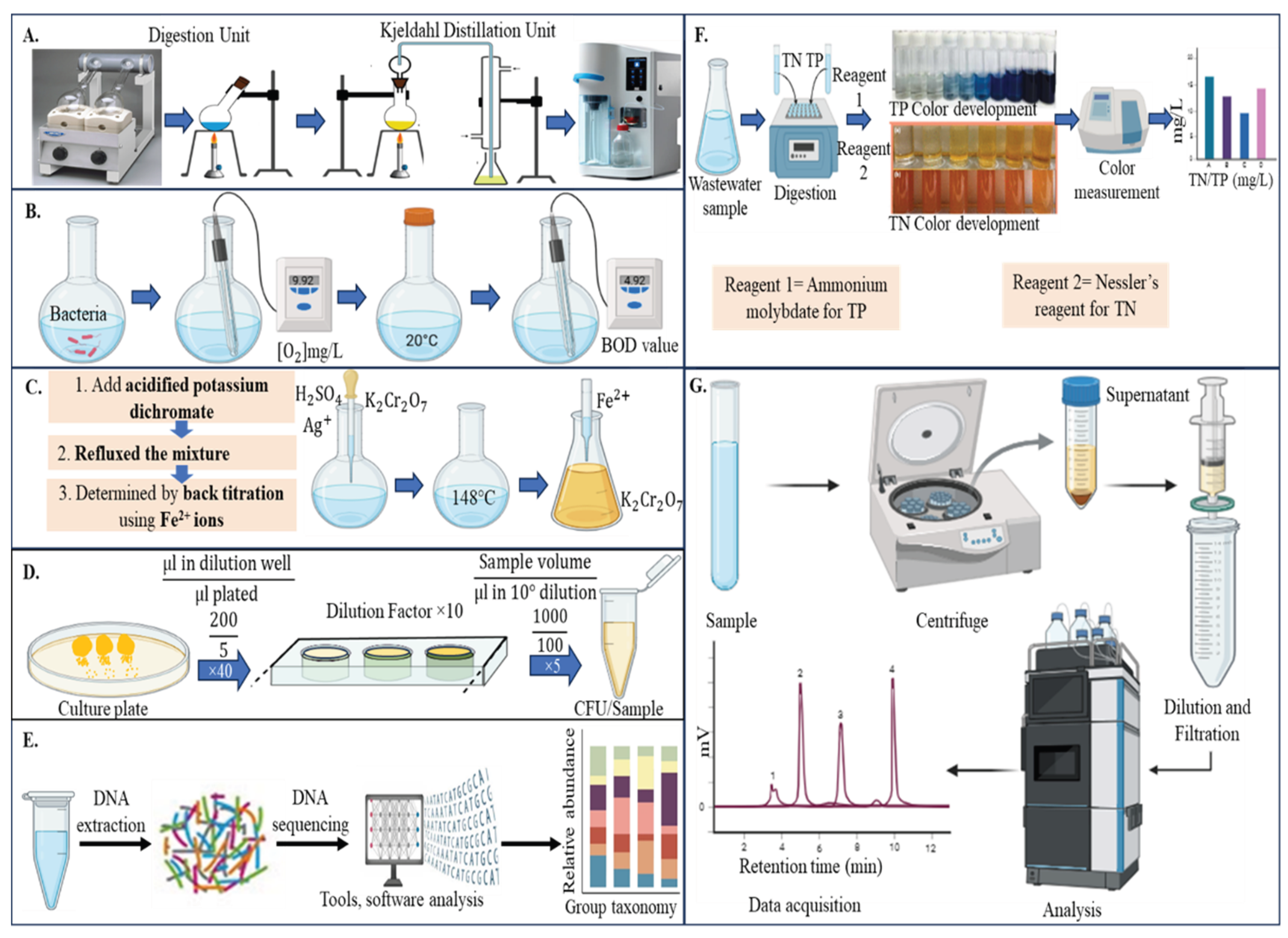

4. Water Quality Indicators in Evaluating FTWs Performance

FTWs are primarily evaluated based on their effectiveness in improving water quality through the removal of key pollutants. Common water quality indicators assessed in FTW studies include DO, TN, TP, colony-forming units (CFU), and concentrations of heavy metals (

Table 3). These parameters are critical for determining both the ecological health of aquatic environments and the performance of FTW-based remediation strategies. This section provides detailed analytical methods, instrumentation, and equations (Equations 1–6) used to quantify these indicators, offering a comprehensive framework for evaluating FTW efficiency.

4.1. Basic Measurement

4.1.1. DO, BOD, COD, and ORP

DO is a key indicator of aquatic ecosystem health, influencing respiration, nutrient cycling, and redox status [

87]. BOD₅ is measured by incubating water samples at 20°C for five days in the dark. COD is determined using the dichromate reflux method, where potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) oxidizes organic matter in the presence of sulfuric acid and silver sulfate (Equation 6). Unreacted dichromate is titrated with ferrous ammonium sulfate using ferroin as an indicator. ORP is used to assess the oxidative or reductive conditions of water [

88].

4.1.2. pH, Temperature and Turbidity

pH affects the solubility and toxicity of substances in water. Acidic conditions increase heavy metal solubility, while alkaline conditions can convert ammonia into its toxic form [

89]. Temperature influences chemical reactions, oxygen solubility, and biological processes. It also affects nutrient uptake and microbial activity in FTWs [

90]. Turbidity measures water clarity and is influenced by suspended particles, erosion, and algal blooms. High turbidity reduces light penetration, affecting photosynthesis and aquatic life.

4.1.3. Nutrient Analysis (TN and TP)

TN is analyzed using alkaline persulfate digestion followed by ion chromatography (IC) (

Figure 8). TP is measured by converting all phosphorus species to orthophosphate using potassium persulfate at ~120°C, followed by colorimetric detection with ammonium molybdate and ascorbic acid. The reaction forms a blue complex measured at 880 nm (Equation 7-10).

4.2. Biological Parameters

4.2.1. Microbial Analysis (CFU and MGA)

CFU is determined by plating diluted water samples on growth media and incubating to count colonies [

85]. MGA involves DNA extraction, fragmentation, and sequencing to identify microbial diversity and resistance genes (Equation 11).

4.3. Heavy Metal Analysis

Water samples are filtered (0.45 µm), acidified with nitric acid, and stored at 4°C. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and ICP-MS are used to quantify metals. ICP-OES detects common elements (P, K, Ca, Mg), while ICP-MS is used for trace metals like Cr, As, Pb [

86]. For plant tissue analysis, plant samples are dried, ground, and digested with acids. Nutrient and metal concentrations are measured using AAS, ICP, or IC. Sampling focuses on roots and leaves to assess bioaccumulation.

4.4. Plant Tissue Analysis

Water samples are first filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane, acidified with nitric acid, and stored at 4 °C until analysis. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) is used to quantify macronutrients such as phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg), while ICP-MS is employed to detect trace metals, including chromium (Cr), arsenic (As), and lead (Pb) [

91]. For plant tissue analysis, samples are oven-dried, ground into a fine powder, and digested using acid mixtures. Nutrient and metal concentrations in plant tissues are then determined using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), ICP techniques, or IC [

91]. Sampling generally focuses on roots and leaves to assess bioaccumulation patterns.

4.5. Performance Metrics and Statistical Analysis

Quantifying pollutant removal efficiency and plant performance is essential for evaluating the effectiveness of FTWs. These metrics reflect the system’s ability to reduce nutrient and heavy metal concentrations, supports plant growth under stress conditions, and monitor contaminant bioaccumulation and translocation within plant tissues. Appendix sections A2.1–A2.5 provide standardized equations for calculating removal efficiency, removal rate (RR, µg/m²/day), plant growth rate (cm/day), and tolerance indices, such as the dry biomass tolerance index, shoot length tolerance index, and root length tolerance index.

Conclusions

FTWs present a sustainable and innovative approach to water purification by integrating ecological processes with engineered design to tackle complex pollution challenges. This review emphasized the multifactorial nature of FTWs performance, highlighting critical parameters such as hydraulic retention time, mat structure, and plant species selection that significantly influence treatment outcomes. Recent advancements in analytical techniques have enhanced the ability to monitor water quality and assess plant performance. Integrating water sampling with plant tissue analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of contaminant dynamics and remediation effectiveness. Establishing standardized metrics for evaluating plant growth and pollutant uptake is essential for enabling cross-study comparisons and assessing FTWs performance across diverse environmental conditions.

While FTWs have demonstrated strong efficacy in removing nutrients and heavy metals, further research is needed to evaluate their long-term stability, resilience to environmental fluctuations, and potential for integration with other treatment technologies. Investigating their capacity to remove emerging contaminants such as pharmaceuticals and microplastics could further expand their application in modern water management. As climate change and urbanization increasingly stress global water resources, FTWs offer a modular, adaptable, and eco-friendly solution. Their multifunctional benefits ranging from pollutant removal to habitat enhancement position FTWs as a key component in future water quality strategies. By building on the insights presented in this review, researchers and practitioners can further advance FTWs, contributing to the restoration of aquatic ecosystems and strengthening global water security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B.; methodology, V.B., N.K., R.L.R. and B.S.; investigation, V.B., N.K., R.L.R. and B.S.; resources, B.V., N.K., R.L.R. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B., N.K., B.S., R.L.R.; writing—review and editing, V.B., N.K., B.S., R.L.R., A.K., W.Z., Y.C., S.K., X.S.; visualization, B.V., R.L.R. X.S.; supervision, B.V., R.L.R.; project administration, V.B., R.L.R.; funding acquisition, V.B., R.L.R., S.K., X.S., W.Z.

Funding

B.V. and R.L.R. have received funding from the Environmental Project Agency (EPA No. 02D48123). We also thank the UH Center for Carbon Management and Energy (CCME) for supporting V.B. with a small research grant.

Data Availability Statement

We have no datasets associated with this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACD |

Activated carbon adsorption |

| AWP |

Above water parts of plants |

| BWP |

Below water parts of plants |

| BG |

Bio-granulation |

| BOD |

Biological oxygen demand |

| BCF |

Biological control factor |

| CW |

Constructed wetlands |

| COD |

Chemical oxygen demand |

| CFU |

Colony forming units |

| DBTI |

Dry biomass tolerance index |

| DO |

Dissolved oxygen |

| FV |

Floating vegetation |

| FTWs |

Floating treatment wetland system |

| GHG |

Greenhouse gases |

| HAB |

Harmful algae blooms |

| HRT |

Hydraulic retention time |

| HRL |

Hydraulic loading rate |

| IC |

Ion chromatography |

| ICP-MS |

Inductively Coupled Plasma mass spectrometry |

| ICP-OES |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry |

| MAF |

Micro-air flotation |

| DWB |

Dry weight basis |

| NFV |

Without floating vegetation |

| ORP |

Oxidation-reduction potential |

| RLTI |

Root length tolerance index |

| SLTI |

Shoot length tolerance index |

| TKN |

Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen |

| TN |

Total nitrogen |

| TP |

Total phosphorus |

| TSS |

Total suspended solids |

| TDN |

Total dissolved nitrogen |

| TF |

Translocation factor |

Appendix A

A.1. Available Water Treatment Strategies for Water Quality

A.1.1. MAF Treatment

MAF is an advanced wastewater treatment that uses ultra-fine air bubbles (under 50 microns) to separate contaminants like suspended solids, oil, grease, algae, and other low-density particles by flotation. This technique works well when traditional sedimentation fails and is used in industries such as food processing, petrochemicals, and textiles. MAF is efficient, compact, and allows precise bubble control, but system costs, complex operation, limited dissolved pollutant removal, and sludge management are notable drawbacks.

A.1.2. ACD Treatment

This method is widely used for treating watershed wastewater and efficiently removes organic pollutants, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and odors. Activated carbon porous structure absorbs various contaminants without changing physical properties of water. While effective and simple, it has high material and regeneration costs, limited removal of heavy metals and inorganic compounds, and decreased performance as the carbon saturates, requiring frequent replacement or regeneration.

A.1.3. BGCP Treatment

This method combines biological granulation (BG) and chemical precipitation for efficient wastewater treatment. BG uses microbial granules to remove organic matter and nutrients; aerobic granules handle oxygen-dependent processes, while anaerobic ones support methanogenesis and denitrification. The approach is efficient, compact, and produces little sludge but needs precise control and has long start-up times. Chemical precipitation adds lime or alum to convert dissolved pollutants into precipitates for easy removal, though it generates chemical sludge and requires careful dosing to avoid secondary pollution.

References

- Gurau, S.; Imran, M.; Ray, R.L. Algae: A Cutting-Edge Solution for Enhancing Soil Health and Accelerating Carbon Sequestration – A Review. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2025, 37, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colares, G.S.; Dell’Osbel, N.; Wiesel, P.G.; Oliveira, G.A.; Lemos, P.H.Z.; Da Silva, F.P.; Lutterbeck, C.A.; Kist, L.T.; Machado, Ê.L. Floating Treatment Wetlands: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 714, 136776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mfarrej, M.F.B.; Wang, X.; Fahid, M.; Saleem, M.H.; Alatawi, A.; Ali, S.; Shabir, G.; Zafar, R.; Afzal, M.; Fahad, S. Floating Treatment Wetlands (FTWs) Is an Innovative Approach for the Remediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons-Contaminated Water. J Plant Growth Regul 2023, 42, 1402–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz,A. ; Shabir, G.; Khan, Q.M.; Afzal, M. Enhanced Remediation of Sewage Effluent by Endo-phyte-Assisted Floating Treatment Wetlands. Ecological Engineering 2015, 84, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Borne, K.E.; Fassman-Beck, E.A.; Winston, R.J.; Hunt, W.F.; Tanner, C.C. Implementa-tion and Maintenance of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Urban Stormwater Management. J. Environ. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Vymazal, J.; Malaviya, P. Application of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Stormwater Runoff: A Critical Review of the Recent Developments with Emphasis on Heavy Metals and Nutrient Removal. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 777, 146044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiohuo, O.; Onyeaka, H.; Akinsemolu, A.; Nwabor, O.F.; Siyanbola, K.F.; Tamasiga, P.; Al-Sharify, Z.T. Ensuring Water Purity: Mitigating Environmental Risks and Safeguarding Human Health. Water Biology and Security 2025, 4, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Gaur, S.; Ohri, A.; Srivastava, P.K.; Singh, N. Applications of Remote Sensing in Water Quality Assessment. In Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 217–236 ISBN 9780323910682.

- Wang, F.; Xiang, L.; Sze-Yin Leung, K.; Elsner, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pan, B.; Sun, H.; An, T.; Ying, G.; et al. Emerging Contaminants: A One Health Perspective. The Innovation 2024, 5, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sultana, K.W.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Mondal, M.; Chandra, I. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Its Impact on Health: Exploring Green Technology for Remediation. Environ Health Insights 2023, 17, 11786302231201259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Their Toxicological Effects on Humans. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.S.; D, D.; S, H.; Sonkusare, S.; Naik, P.B.; Kumari N, S.; Madhyastha, H. Environmental Pollutants and Their Effects on Human Health. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, R.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Mahiya, S.; Chattopadhyaya, M.C. CHAPTER 1. Contamination of Heavy Metals in Aquatic Media: Transport, Toxicity and Technologies for Remediation. In Heavy Metals In Water; Sharma, S., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2014; ISBN 9781849738859. [Google Scholar]

- Derksen, J.G.M.; Rijs, G.B.J.; Jongbloed, R.H. Diffuse Pollution of Surface Water by Pharmaceutical Products. Water Science and Technology 2004, 49, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortúzar, M.; Esterhuizen, M.; Olicón-Hernández, D.R.; González-López, J.; Aranda, E. Pharmaceutical Pollution in Aquatic Environments: A Concise Review of Environmental Impacts and Bioremediation Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 869332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jureczko, M.; Kalka, J. Cytostatic Pharmaceuticals as Water Contaminants. European Journal of Pharmacology 2020, 866, 172816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennmalm, Å.; Gunnarsson, B. Pharmaceutical Management through Environmental Product Labeling in Sweden. Environment International 2009, 35, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, A.; Pey, A.; Gianni, F.; Lemée, R.; Mangialajo, L. Multiple Stressors and Benthic Harmful Algal Blooms (BHABs): Potential Effects of Temperature Rise and Nutrient Enrichment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 131, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Trainer, V.L.; Smayda, T.J.; Karlson, B.S.O.; Trick, C.G.; Kudela, R.M.; Ishikawa, A.; Bernard, S.; Wulff, A.; Anderson, D.M.; et al. Harmful Algal Blooms and Climate Change: Learning from the Past and Present to Forecast the Future. Harmful Algae 2015, 49, 68–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA, O. Climate Change and Freshwater Harmful Algal Blooms. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/habs/climate-change-and-freshwater-harmful-algal-blooms (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Zheng, T.; Wang, Q.; Shi, Z.; Huang, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. Separation of Pollu-tants from Oil-Containing Restaurant Wastewater by Novel Microbubble Air Flotation and Traditional Dissolved Air Flotation. Separation Science and Technology 2015, 150707113117003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Kim, H.; KuK, J.W.; Chung, J.D.; Park, S.; Kwon, E.E. Micro-Bubble Flow Simulation of Dissolved Air Flotation Process for Water Treatment Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Technique. Environmental Pollution 2020, 256, 112050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T.A.; Meisenheimer, M.; McDowell, D.; Sacher, F.; Brauch, H.-J.; Haist-Gulde, B.; Preuss, G.; Wilme, U.; Zulei-Seibert, N. Removal of Pharmaceuticals during Drinking Water Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 3855–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudov, R.; Huang, C.P. Perchlorate Removal by Activated Carbon Adsorption. Separation and Purification Technology 2010, 70, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.J.; AL-surhanee, A.A.; Kouadri, F.; Ali, S.; Nawaz, N.; Afzal, M.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, B.; Soliman, M.H. Role of Microorganisms in the Remediation of Wastewater in Floating Treatment Wetlands: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalia, M.C.; Youcef, L.; Bouaziz, M.G.; Achour, S.; Menasra, H. Removal of Heavy Metals from Industrial Wastewater by Chemical Precipitation: Mechanisms and Sludge Characterization. Arab J Sci Eng 2022, 47, 5587–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Vymazal, J.; Malaviya, P. Application of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Stormwater Runoff: A Critical Review of the Recent Developments with Emphasis on Heavy Metals and Nutrient Removal. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 777, 146044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.J.; Arslan, M.; Ali, S.; Siddique, M.; Afzal, M. Floating Wetlands: A Sustainable Tool for Wastewater Treatment. CLEAN Soil Air Water 2018, 46, 1800120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlineri, N.; Skoulikidis, N.Th.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Constructed Floating Wetlands: A Review of Research, Design, Operation and Management Aspects, and Data Me-ta-Analysis. Chemical Engi-neering Journal 2017, 308, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.C.; Headley, T.R. Components of Floating Emergent Macrophyte Treatment Wetlands Influencing Removal of Stormwater Pollutants. Ecological Engineering 2011, 37, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivukkarasu, D.; Sathyanathan, R. Floating Wetland Treatment an Ecological Ap-proach for the Treatment of Water and Wastewater – A Review. Materials Today: Pro-ceedings 2023, 77, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Arslan, M.; Müller, J.A.; Shabir, G.; Islam, E.; Tahseen, R.; Anwar-ul-Haq, M.; Hashmat, A.J.; Iqbal, S.; Khan, Q.M. Floating Treatment Wetlands as a Suitable Option for Large-Scale Wastewater Treatment. Nat Sustain 2019, 2, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, M. Phytoremediation Strategies for Mitigating Environmental Toxicants. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Li, X.; Lu, X. Recent Developments and Applications of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Treating Different Source Waters: A Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 62061–62084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayanthan, S.; Hasan, H.A.; Abdullah, S.R.S. Floating Aquatic Macrophytes in Wastewater Treatment: Toward a Circular Economy. Water 2024, 16, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palihakkara, C.R.; Dassanayake, S.; Jayawardena, C.; Senanayake, I.P. Floating Wetland Treatment of Acid Mine Drainage Using Eichhornia Crassipes (Water Hyacinth). Journal of Health and Pollu-tion 2018, 8, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutiani, R.; Rai, N.; Sharma, P.K.; Rausa, K.; Ahamad, F. Phytoremediation Efficiency of Water Hyacinth (E. Crassipes), Canna (C. Indica) and Duckweed (L. Minor) Plants in Treatment of Sewage Water. ECJ 2019, 20, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivukkarasu, D.; Sathyanathan, R. Floating Wetland Treatment an Ecological Ap-proach for the Treatment of Water and Wastewater – A Review. Materials Today: Pro-ceedings 2023, 77, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.A.; Carabal, N. Selecting Submerged Macrophyte Species for Replanting in Mediterranean Eutrophic Wetlands. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 24, e01349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, M.; He, D.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; Fang, F.; Yang, L. Submerged Macrophyte Promoted Nitrogen Removal Function of Biofilms in Constructed Wetland. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 914, 169666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borne, K.E.; Fassman-Beck, E.A.; Winston, R.J.; Hunt, W.F.; Tanner, C.C. Implementation and Maintenance of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Urban Stormwater Management. J. Environ. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Installation and Maintenance of Floating Treatment Wetlands: A Guide on Retrofitting Stormwater Retention Ponds in North Carolina | NC State Extension Publications. Available online: https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/installation-and-maintenance-of-floating-treatment-wetlands (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Shweta Yadav, Jhalesh Kumar, Sandeep Kumar, Rajesh Singh, Omkar Singh, Vikas Chandra Goyal, Singh and Ritika Negi, Evaluating Pilot-Scale Floating Wetland for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Using Canna indica and Phragmites australis as Plant Species. Sustainability 2023, 15(18), 13601. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Rao, Q.; Chen, B.; Liu, X.; Adnan Ikram, R.M.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, D. Mechanisms and Applications of Nature-Based Solutions for Stormwater Control in the Context of Climate Change: A Review. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature-Based Solutions for Urban, Sustainability; Lens, P.N.L. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability; Lens, P.N.L., Bui, X.-T., Eds.; IWA Publishing, 2025; ISBN 9781789065015. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, A.; Bresciani, R.; Masi, F.; Boano, F.; Revelli, R.; Ridolfi, L. Flood Reduction as an Ecosystem Service of Constructed Wetlands for Combined Sewer Overflow. Journal of Hydrology 2018, 560, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, C.; Rodríguez-Gallego, L.; De León, G.; Cabrera-Lamanna, L.; Castagna, A.; Costa, S.; González, L.; Meerhoff, M. Potential of Different Buffer Zones as Nature-Based Solutions to Mitigate Agricultural Runoff Nutrients in the Subtropics. Ecological Engineering 2024, 207, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Rajak, F.; Jha, R. Integrating Wetlands as Nature-Based Solutions for Sustainable Built Environments: A Comprehensive Review. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 18670–18680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Jiang, M.; Han, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Bian, C.; Du, Y.; Yan, L.; Xia, J. Experimental Warming Reduces Ecosystem Resistance and Resilience to Severe Flooding in a Wetland. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl9526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, C.; Scaroni, A.E.; Wallover, C.G.; White, S.A. Understanding Resident Design Preferences and Priorities for Floating Wetlands in Coastal Stormwater Ponds. Urban Ecosyst 2025, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, P.; Lucke, T.; Drapper, D.; Walker, C. Performance Evaluation of a Floating Treatment Wetland in an Urban Catchment. Water 2016, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Hu, G.; Deng, W.; Zhao, M.; Li, J. Industrial Wastewater Treatment Using Floating Wetlands: A Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 31, 5043–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambunan, J.A.M.; Effendi, H.; Krisanti, M. Phytoremediating Batik Wastewater Using Vetiver Chrysopogon Zizanioides (L). Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaitidak, D.M.; Yadav, K.D. Characteristics and Treatment of Greywater—A Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2013, 20, 2795–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.E.; Harrison, J.A. Effects of Floating Vegetation on Denitrification, Nitrogen Retention, and Greenhouse Gas Production in Wetland Microcosms. Biogeochemistry 2014, 119, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.-C.; He, H.; Gu, J.; Li, K.-Y. Effects of Nutrient Levels and Light Intensity on Aquatic Macrophyte (Myriophyllum Aquaticum) Grown in Floating-Bed Platform. Ecological Engineering 2019, 128, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Vymazal, J.; Malaviya, P. Application of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Stormwater Runoff: A Critical Review of the Recent Developments with Emphasis on Heavy Metals and Nutrient Removal. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 777, 146044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.; Fox, L.J.; Owen, J.S., Jr.; Sample, D.J. Evaluation of Commercial Floating Treatment Wetland Technologies for Nutrient Remediation of Stormwater. Ecological Engineering 2015, 75, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Stein, O.R.; Hook, P.B.; Burr, M.D.; Parker, A.E.; Hafla, E.C. Temperature, Plant Species and Residence Time Effects on Nitrogen Removal in Model Treatment Wetlands. Water Science and Technology 2013, 68, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.A.; Cousins, M.M. Floating Treatment Wetland Aided Remediation of Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Simulated Stormwater Runoff. Ecological Engineering 2013, 61, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilhauer, M.G.; Messer, T.L.; Mittelstet, A.R.; Franti, T.G.; Corman, J. Nitrate Removal by Floating Treatment Wetlands Amended with Spent Coffee: A Mesocosm-Scale Evaluation. Transactions of the ASABE 2019, 62, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Anwar, A.H.M.F.; Sarukkalige, R. Metal Removal Kinetics, Bioaccumulation and Plant Response to Nutrient Availability in Floating Treatment Wetland for Stormwater Treatment. Water 2022, 14, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Chance, L.M.; Van Brunt, S.C.; Majsztrik, J.C.; White, S.A. Short- and Long-Term Dynamics of Nutrient Removal in Floating Treatment Wetlands. Water Research 2019, 159, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovi, A.A.; De Barros Aguiar, A.R.; Benassi, R.F.; Vymazal, J.; De Jesus, T.A. Phosphorus Removal in a Pilot Scale Free Water Surface Constructed Wetland: Hydraulic Retention Time, Seasonality and Standing Stock Evaluation. Chemosphere 2021, 266, 128939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakshi, D.; Sharma, P.K.; Rani, A.; Malaviya, P.; Srivastava, V.; Kumar, M. Perfor-mance Evaluation of Vertical Constructed Wetland Units with Hydraulic Retention Time as a Variable Operating Factor. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2022, 19, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakshi, D.; Sharma, P.K.; Rani, A. Effect of Filter Media and Hydraulic Retention Time on the Performance of Vertical Constructed Wetland System Treating Dairy Farm Wastewater. Environmental Engineering Research 2021, 27, 200436–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Costa, O.S. Nutrient Sequestration by Two Aquatic Macrophytes on Artificial Floating Islands in a Constructed Wetland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Chance, L.M.; Majsztrik, J.C.; Bridges, W.C.; Willis, S.A.; Albano, J.P.; White, S.A. Comparative Nutrient Remediation by Monoculture and Mixed Species Plantings within Floating Treatment Wetlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8710–8718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, J.A.; Paqualini, J.P.; Rodrigues, L.R. Root Growth and Nutrient Removal of Typha Domingensis and Schoenoplectus Californicus over the Period of Plant Establishment in a Constructed Floating Wetland. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 8927–8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwammberger, P.F.; Lucke, T.; Walker, C.; Trueman, S.J. Nutrient Uptake by Constructed Floating Wetland Plants during the Construction Phase of an Urban Residential Development. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 677, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L.; Heikkilä, A.M.; Pandey, K.K.; Bruckman, L.S.; White, C.C.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, L. Effects of UV Radiation on Natural and Synthetic Materials. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2023, 22, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Installation and Maintenance of Floating Treatment Wetlands: A Guide on Retrofitting Stormwater Retention Ponds in North Carolina | NC State Extension Publications Available online:. Available online: https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/installation-and-maintenance-of-floating-treatment-wetlands (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Winston, R.J.; Hunt, W.F.; Kennedy, S.G.; Merriman, L.S.; Chandler, J.; Brown, D. Evaluation of Floating Treatment Wetlands as Retrofits to Existing Stormwater Retention Ponds. Ecological Engineering 2013, 54, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghigo, A.; Faraggiana, E.; Sirigu, M.; Mattiazzo, G.; Bracco, G. Design and Analysis of a Floating Photovoltaic System for Offshore Installation: The Case Study of Lampedusa. Energies 2022, 15, 8804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Anwar, A.H.M.F.; Sarukkalige, R. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling of Floating Treatment Wetland Retrofitted Stormwater Pond: Investigation on Design Configurations. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 337, 117746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shan, Y.; Lei, J.; Nepf, H. Floating Treatment Islands in Series along a Channel: The Impact of Island Spacing on the Velocity Field and Estimated Mass Removal. Advances in Water Resources 2019, 129, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schück, M.; Greger, M. Screening the Capacity of 34 Wetland Plant Species to Remove Heavy Metals from Water. IJERPH 2020, 17, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeewani, S.N.; Chandrasekara, S.S.K.; Hemalal, D.L.H.V.W.; Deegala, H.M.S.N.; Jinadasa, K.B.S.N.; Weragoda, S.K.; Mowjood, M.I.M.; Jegatheesan, V. Guide to the Selections of Plants for Floating Wetlands. In Water Treatment in Urban Environments: A Guide for the Implementation and Scaling of Nature-based Solutions; Jegatheesan, V., Velasco, P., Pachova, N., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 9783031492815. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, B.; Lei, T.; Chen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Dong, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, G. Microbial Degradation and Watershed Weathering Jointly Regulate Soil Organic Matter Stabilization in Alpine Wetlands. Commun Earth Environ 2025, 6, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Li, X.; Lu, X. Recent Developments and Applications of Floating Treatment Wetlands for Treating Different Source Waters: A Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 62061–62084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissolved Oxygen. Available online: https://www.fondriest.com/environmental-measurements/parameters/water-quality/dissolved-oxygen/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- White, S.A.; Cousins, M.M. Floating Treatment Wetland Aided Remediation of Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Simulated Stormwater Runoff. Ecological Engineering 2013, 61, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Kamyab, H.; Rupani, P.F.; Park, J.; Nawrot, N.; Wojciechowska, E.; Yadav, K.K.; Lotfi Ghahroud, M.; Mohammadi, A.A.; Thirugnana, S.T.; et al. Recent Advances on the Removal of Phosphorus in Aquatic Plant-Based Systems. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021, 24, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, E.K.; Hartl, M.; Kisser, J.; Cetecioglu, Z. Phosphorus Mining from Eutrophic Marine Environment towards a Blue Economy: The Role of Bio-Based Applications. Water Research 2022, 219, 118505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Crucial Role of CFU Count in Bacteria Culture for Water Treatment - Purewater Enterprises Private Limited 2023.

- Qasem, N.A.A.; Mohammed, R.H.; Lawal, D.U. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater: A Comprehensive and Critical Review. npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Chakrabarty, M.; Rakshit, N.; Bhowmick, A.R.; Ray, S. Environmental Factors as Indicators of Dissolved Oxygen Concentration and Zooplankton Abundance: Deep Learning versus Traditional Regression Approach. Ecological Indicators 2019, 100, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, N.; Piao, H.; Sun, D.; Ratnaweera, H.; Maletskyi, Z.; Bi, X. Characterization of Oxidation-Reduction Potential Variations in Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes: A Study from Mechanism to Application. Processes 2022, 10, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saalidong, B.M.; Aram, S.A.; Otu, S.; Lartey, P.O. Examining the Dynamics of the Relationship between Water pH and Other Water Quality Parameters in Ground and Surface Water Systems. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werker, A.G.; Dougherty, J.M.; McHenry, J.L.; Van Loon, W.A. Treatment Variability for Wetland Wastewater Treatment Design in Cold Climates. Ecological Engineering 2002, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, S.; Persson, D.P.; Laursen, K.H.; Hansen, T.H.; Pedas, P.; Schiller, M.; Hegelund, J.N.; Schjoerring, J.K. Review: The Role of Atomic Spectrometry in Plant Science. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2011, 26, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot, N.; Wojciechowska, E.; Mohsin, M.; Kuittinen, S.; Pappinen, A.; Matej-Łukowicz, K.; Szczepańska, K.; Cichowska, A.; Irshad, M.A.; Tack, F.M.G. Chromium (III) Removal by Perennial Emerging Macrophytes in Floating Treatment Wetlands. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.A.; Yiwen, M.; Saleh, M.; Salleh, M.N.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Giap, S.G.E.; Chinni, S.V.; Gobinath, R. Bioaccumulation and Translocation of Heavy Metals in Paddy (Oryza Sativa L.) and Soil in Different Land Use Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Natural processes and human activities contribute to pollution in watersheds, rivers, and oceans. Here, A. Water bodies become polluted due to soil erosion from monsoons and heavy rainfall, agricultural runoff containing pesticides, fertilizers, and animal waste, industrial discharges of heavy metals and toxic chemicals, and urban runoff carrying oil, debris, and other pollutants. B. The resulting elevated concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and heavy metals in ponds, lakes, rivers, and oceans promote algal blooms, leading to ecological imbalances. The areal extent of the dead zone is 7,829 mi2 (square mile) in the gulf of America alone.

Figure 1.

Natural processes and human activities contribute to pollution in watersheds, rivers, and oceans. Here, A. Water bodies become polluted due to soil erosion from monsoons and heavy rainfall, agricultural runoff containing pesticides, fertilizers, and animal waste, industrial discharges of heavy metals and toxic chemicals, and urban runoff carrying oil, debris, and other pollutants. B. The resulting elevated concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and heavy metals in ponds, lakes, rivers, and oceans promote algal blooms, leading to ecological imbalances. The areal extent of the dead zone is 7,829 mi2 (square mile) in the gulf of America alone.

Figure 2.

Conditions favoring algal blooms. Harmful algal blooms thrive under specific environmental conditions, including elevated water temperatures, excess nitrogen and phosphorus, heavy runoff, and favorable summer weather. These factors accelerate bloom formation, leading to the release of toxic metabolites, depletion of DO causing hypoxia in aquatic organisms and disruption of nutrient absorption by beneficial microorganisms, ultimately compromising water quality. During winter, unfavorable bloom conditions significantly limit algae growth. However, when present, harmful algal blooms pose serious environmental threats, affecting aquatic ecosystems, plant life, human health, and overall ecological balance.

Figure 2.

Conditions favoring algal blooms. Harmful algal blooms thrive under specific environmental conditions, including elevated water temperatures, excess nitrogen and phosphorus, heavy runoff, and favorable summer weather. These factors accelerate bloom formation, leading to the release of toxic metabolites, depletion of DO causing hypoxia in aquatic organisms and disruption of nutrient absorption by beneficial microorganisms, ultimately compromising water quality. During winter, unfavorable bloom conditions significantly limit algae growth. However, when present, harmful algal blooms pose serious environmental threats, affecting aquatic ecosystems, plant life, human health, and overall ecological balance.

Figure 3.

Water treatment methods for purifying contaminated watershed water. Overview of key treatment techniques used to purify contaminated water from watersheds, including, A. Micro-Air Flotation (MAF), B. Bio-Granulation with Chemical Precipitation, C. Constructed Wetland Restoration (CWR), and D. Activated Carbon Adsorption (ACD).

Figure 3.

Water treatment methods for purifying contaminated watershed water. Overview of key treatment techniques used to purify contaminated water from watersheds, including, A. Micro-Air Flotation (MAF), B. Bio-Granulation with Chemical Precipitation, C. Constructed Wetland Restoration (CWR), and D. Activated Carbon Adsorption (ACD).

Figure 4.