1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Toxic leadership is a form of leadership characterised by leaders who exhibit abusive supervision, manipulation, narcissism, and unethical behaviour, which negatively affects the well-being of the employees and the integrity of the organisations therein (Tiwaria & Jha, 2022). These leaders tend to prioritise their interests over the common good and often exploit their subordinates, fostering unpleasant working conditions. This may take the form of academic bullying, favouritism, intellectual sabotage, or unethical decision making regarding higher educational institution (HEI) autonomy (Milosevic et al., 2020). Such behaviours can be inadvertently excused within the cultural context in HEIs, where excessive competitiveness, decentralised governance, and individualism are typical features of an HEI environment (Ul Hassan et al., 2025).

Organisational ethics, on the contrary, are the principles, standards, and morals that govern decision making and behaviour within an organisation. Fairness, transparency, and moral consistency require ethical leadership (Roszkowska & Melé, 2021). However, whenever the dark personality traits of leaders, including Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy, hold important positions, their ethical frameworks are, in most cases, distorted or avoided in favour of their selfish interests. This not only erodes trust but may also create a misplaced culture where unethical behaviour is accepted as the norm (Milosevic et al., 2020). Furthermore, research suggests that, besides creating damage at the top that extends throughout the organisation, toxic leadership can, in fact, start significant moral decay in organisations.

1.2. Problem Statement

Dark personality characteristics such as Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy are not only confined to the individual pathology, as they may extend to the organisational environment via behavioural and psychological processes (Coleman & Dulewicz, 2025). Academic institutions with high levels of people accustomed to hierarchical power, competition, and independence may contribute to the reinforcement or imitation of these tendencies by employees influenced by toxic leaders (Jhaver et al., 2023). Leaders, with their manipulative behaviour, personality-based decisions, or emotional insensitiveness, unknowingly demonstrate behaviours that are absorbed by their subordinates. The similarities can be adopted by employees as coping techniques to survive or as part of a social learning process (Ul Hassan et al., 2025). The psychological effect is not confined to job performance; it also impacts identity, values and interpersonal norms. Such a dynamic poses a danger to institutional integrity, academic standards, and the ethical formation of future professionals and scholars.

1.3. Purpose of the Study

This study aims to investigate the relationship between Leader Dark Triad (LDT) and Employee Dark Triad (EDT) traits in higher education institutions. Although previous studies primarily focused on the top-down effect that toxic leaders have, this experiment marks the first attempt to reveal how dark characteristics can either surface or develop within employees and, consequently, shape leader behaviour or perception. In examining such interactions, this study can contribute more knowledge on toxic trait contagion and ethical erosion in organisations.

1.4. Research Gaps

The current body of research on dark personality traits is rather one-sided, since it assumes that the only source of toxic behaviour is a leader, and there can be no effect on the employees (Tiwari & Jha, 2022). Most models assume that the flow is one way, i.e., leader to follower, disregarding the perceived or actual reflection, reinforcement, or projection of some of the same characteristics by employees (Jhaver et al., 2023). The capacity to accommodate the dynamic nature of the leader–follower interaction has never been addressed because it is limited in this sense, only focusing on the leader and follower in an academic setting, where the power interaction is not fixed.

1.5. The Research Aims and Questions

This research project aims to investigate the interdependent nature of the Leader Dark Triad (LDT) trait and the Employee Dark Triad (EDT) trait in institutions of higher learning, focusing on how these two traits interact, support, or replicate each other. It attempts to comprehend the processes of trait contagion, role modelling, and projection based on psychological and behavioural modelling.

This research addresses the following questions:

1. To what extent do Leader Dark Triad traits predict the emergence or intensification of Employee Dark Triad traits? To be answered in a quantitative capacity

2. How dark behaviours are internalised? To be answered in a qualitative capacity

This work, based on a mixed-methods, explanatory cross-sectional design, aims to investigate the mutual effect of the personality traits of the Leader and Employee Dark Triad in institutions of higher learning. Quantitative data are gathered using validated personality scales and then analysed using a statistical analysis, which involves regression and structural equation modelling. A qualitative component, including semi-structured interviews with experienced leaders, sheds light on the lived experiences of toxic leadership. This dissertation study comprises eight chapters: Introduction, Literature Review, Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses, Methodology, Quantitative Results, Qualitative Findings, Discussion, and Conclusion. Overall, these sections form a detailed and methodical study of the research issue.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dark Triad in Leadership (LDT)

A Dark Triad (DT) of personality, which includes Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy, is a set of socially adverse traits that are, in most cases, investigated in organisational leadership studies (Bueno-de la Fuente et al., 2025). Although these characteristics are quite different, several common traits tie them together: callousness, self-interest, and the inability to empathise. Kezar (2023) claims that such leaders can play a significant role in determining the nature of interactions within organisations, especially within complex and hierarchical organisations, like higher education institutions (HEIs).

Machiavellianism has been characterised by strategic manipulation, a cynical perception of human nature, and a willingness to use others in furtherance of self-interest. Individuals with high scores in this trait are typically despotically self-seeking leaders, morally detached, who often deceive and manipulate to achieve their goals (Coleman & Dulewicz, 2025). This can be observed in academia in the form of gatekeeping behaviours, patronage, or behind-the-scenes politics, which are used to achieve power or even funding (Jhaver et al., 2023). Narcissism can be characterised by exaggerated feelings of self-importance, an incessant need to be complimented, and ultra-sensitivity to criticism. Narcissistic leaders can often appear liberal or even revolutionary, but their agenda is usually self-enhancement (Tiwari & Jha, 2022). Such leaders can focus more on their prestige, publications, or reputation rather than on common-good goals, and establish a competitive culture and depreciate cooperation in HEIs. Spytska (2025) highlights that psychopathy, especially its subclinical type, comprises impulsivity, coldness of emotions, and a lack of remorse for actions.

The implications of the LDT characteristics in HEIs may be detrimental. The literature identifies several relationships associated with toxic leadership, including elevated staff turnover, decreased job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, and demoralisation of organisational commitment (Ofei et al., 2023). An increasing number of works reveal the ability of leaders with dark traits to manipulate in this manner, as well as their egocentric behaviours and apparent moral or ethical disregard for the questions. In addition, such behaviours are conceivably protected or even privileged by the hierarchical and individualistic nature of academia (Budak & Erdal, 2022), whereas in corporate settings, it may be more feasible to measure (and evaluate) performance, dark traits have the cushion of diffuse accountability to maintain their existence within HEIs (Kezar, 2023). Besides affecting their behaviour, workers with high levels of the Dark Triad traits tend to develop psychologically unsafe work environments, where criticism is not allowed, and ethical issues are not welcome (Ilac & Mactal, 2023). This may stifle innovation, muzzle whistleblowers, and prevent openness—essential aspects in academic institutions, where research is conducted openly and by peers. Research has also shown that these leaders tend to become exploitative in their mentorship, either retaining the success of the subordinates or using them to achieve personal satisfaction (Jhaver et al., 2023). Additionally, LDT characteristics can be easily camouflaged with charisma or manipulative self-representations, and thus, one needs a rather long period of time to start recognising the damage to moral and institutional confidence (Tiwari & Jha, 2022).

2.2. Dark Triad in Employees (EDT)

The Dark Triad in the workplace could be taken to mean the occurrence of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy among the common employees of an educational organisation and not the managers. Such dynamics among employees are not merely characteristics that emerge independently; instead, they develop due to contextual or mutual influences with leaders who have the same traits (Pimentel et al., 2024). Machiavellian workers are more likely to engage in manipulative, political gamesmanship and self-centred stunts, usually to the detriment of their colleagues or the objectives of the institution. Narcissistic employees are inclined to seek and get attention, overstate their contributions, and respond to rewards, whereas psychopathic employees may exhibit detached emotions, disruptive behaviours, or negativity regarding the welfare of others (Smith & Lee, 2024).

Academic freedom, collegiality, and trust are essential features in a higher education institution, and Employee Dark Triad characteristics can silently erode organisational principles (Amir et al., 2023). Machiavellianism is demonstrated among employees who use an informal system to climb the organisational ladder, distort reports to advance their careers, or undermine the work of others in competitive workplaces. Such behaviours can be more difficult to observe because they are commonly concealed under the strategy of compliance and oversold professionalism. In the same vein, narcissistic traits can always manifest in the form of self-promotion, hogging corporate achievements, or declaring oneself as an essential right hand of the supervisor (Khoo & Shee, 2023).

The less obvious psychopathic employees may be especially problematic. They can exhibit utter contempt for reasonable co-working rules, establish unpleasant working conditions, or be indifferent to interpersonal contradictions and ethical issues (Ilac & Mactal, 2023). Toxic behaviours, in such situations, become justifiable, and in the case of ambition, competitiveness and personal drive, serve to avoid any form of formal sanction. This is because leaders act as role models or allow unethical behaviours, and employees learn to internalise these trends as survival strategies, especially when attending institutions where whistle-blowing is a punitive act, or where ethical integrity is underestimated (Hammali & Nastiezaie, 2022).

Organisational implications are quite extensive. Not only do Dark Triad traits at the employee level undermine teamwork, but such traits also create distrust, leading to a culture of personalism and suspicion (Clement & Favaro, 2024). Group goals are set aside as individual agendas take precedence and peer relations shift to a transactional direction. Eventually, this undermines institutional stability and upsets the psychosocial context within which collaboration and innovative capacity become viable. Moreover, in situations where those characteristics have been entrenched, new recruits can be forced into imitating such features to fit in or be successful, particularly when they discover that dark behaviours are tolerated or celebrated (Muss et al., 2024).

2.3. Leader–Follower Trait Dynamics

The leader–follower trait dynamic in the leader–follower trait dynamic is an interchange that occurs between leaders and followers, defined as the representation of reciprocity in which the traits interplay and influence each other (Muchunguzi, 2023). The process can be imminent with technologically advanced operations and events in crisis management. In such an environment, the relationship between the leader and the followers is crucial, and the behaviour and attitude of such followers can be significantly influenced by paying attention to the ideas of counselling leaders to commit themselves to specific qualities (Hubbart, 2024). People working under pressure usually follow the model of behaviours exemplified by leaders and even imitate them; this creates a repeating cycle where followers imitate the behaviours of the leaders, thus cementing them in the organisation.

In cases where leaders are required to clear a crowd during such simulations, role modelling is particularly relevant to the leader (Wu et al., 2022). Followers, in this case, precisely imitate the behaviour of the leader, and this creates a cycle whereby behaviours reinforce certain character traits. This kind of role modelling is not limited to present-day circumstances; it can have long-term consequences on how followers behave, as well as their ability to respond to a future emergency (Anglin et al., 2022). The dynamics of leader influence become even more complex when leaders exhibit habitual traits of darkness and followers automatically copy these habits, hence forming a pattern of toxic culture (Carvalho et al., 2024).

Such processes do not remain confined to physical environments and are indicated by followers adopting certain attributes at both the psychological and behavioural levels. The good deeds of leaders in an organisation can help develop or nurture dark triad traits within followers, forming a vicious circle where unethical or manipulative actions become a standard trait (Carvalho et al., 2024). Thus, understanding leader–follower trait dynamics is crucial to offer insights on how to combine these forces to address the spread of negative traits within organisations.

2.4. Theoretical Frameworks

The current investigation is based on four major theoretical frameworks that explain how dark personality traits can be transferred, strengthened, or viewed in the context of a leader-and-follower relationship within higher education institutions.

2.4.1. Jung’s Shadow Theory

According to Jung's Shadow Theory, everyone has personality aspects that they are unaware of, called the shadow, which tend to comprise characteristics people despise or are uncomfortable with within themselves (Bibi, 2024). At the organisational level, when employees feel guilty about having such dark traits themselves, they externalise them by projecting them onto other people, particularly those in positions of authority (Ofei et al., 2023). This psychological projection could be initiated by leaders whose dark traits are visible, thus generating distorted images or reinforcing each other (Salmela & Capelos, 2021).

2.4.2. Toxic Triangle

The combination of the three elements (destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments) forms the basis of toxic leadership, which is referred to as the Toxic Triangle (Chen & Sun, 2021). This theory highlights the fact that poisonous behaviour flourishes under two conditions: followers are either conformers (low self-esteem) or colluders (ambitious individuals who value reinforcement from toxic leaders), and the organisational culture encourages unethical behaviour (Spytska, 2025).

2.4.3. Social Learning Theory

According to the Social Learning Theory, people acquire behaviours because they observe and copy others, particularly individuals in authoritative power (Bandura, 2024). In hierarchical institutions of learning, leaders can be an exemplar of behaviour. Workers who have experienced manipulative, narcissistic, or emotionally distant leadership styles can adopt those tendencies either unconsciously or consciously in their future leadership roles, particularly since these tendencies seem to work or be rewarded (Bueno-de la Fuente et al., 2025).

2.4.4. Psychological Projection Theory

The Psychological Projection Theory indicates that people protect themselves against uncomfortable characteristics by projecting the traits of others (Todd & Tamir, 2024). Due to the toxic environment, there is a possibility that employees psychologically project their dark impulses onto their leaders, and by focusing on this, they incorrectly believe that the leader is manipulative or a narcissist, or the extent of this phenomenon is overestimated (Shumate, 2021). The reverse can also be true, because leaders can project onto employees, thus creating lines of defence in terms of mistrust and mimicry. The psychological projection is a defensive mechanism through which one perceives a depreciating image that contains his or her unacceptable thoughts, emotions, or impulses in other individuals. It is essentially a scapegoating system of resolution in regard to dealing with self-conflict, in which a person attributes unsatisfactory elements of the self to another person and is not necessarily willing to accept responsibility.

3. Conceptual Framework & Hypotheses

3.1. Framework Explanation

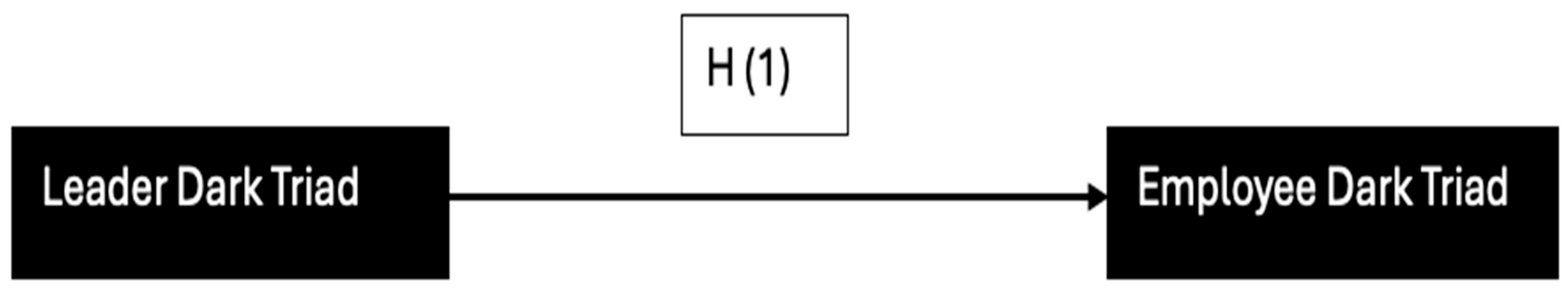

The follow-up conceptual framework in

Figure 1 on which the present study proceeded outlined that LDT and EDT are not two separate events but are, in fact, in a mutual and circular relationship. This structure, in a sense, presupposes the nature and the action of the leaders, i.e., the way they act and what their characteristics are regarding Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy, which serve as indicators of the emergence and strengthening of the same traits in their subordinates (

Liyanagamage & Fernando, 2023). Conversely, the dark attributes of employees can realign the way employees feel or react towards their leaders, thereby creating a feedback loop that perpetuates diseased practices within an organisation (

Hubbart, 2024).

3.2. Literature synthesis

H1: Leader Dark Triad (LDT) traits positively predict overall Employee Dark Triad (EDT) traits.

The above title presents the case for the current hypothesis, which suggests that dark traits in leaders (LDT) influence the development of dark traits in employees (EDT). The existence of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy in leaders further leads to an improved opportunity to express these characteristics among employees, leading to an increase in the harmful circle of behaviour. The underlying concept of this hypothesis is that manipulative and strategically exploitative Machiavellian leaders who are inclined to put themselves at the centre of their attention and are characterised by self-interest are likely to make their employees act similarly. When this condition for employees prevails, particularly when they are subjected to Machiavellian leadership, they tend to think like those who manipulate. Narcissistic bosses are driven by the boundaries of selfishness and an inflated sense of their importance, and these types of bosses can pass on narcissism to the workers. When subordinates view and socialise with narcissistic executives, they can take on their characteristics and thus create a workforce that is self-centred and less interested in others. Leaders with psychopathy, such as apathy, impulsiveness, and antisocial behaviour, are well poised to affect psychopathy among their employees. Psychopathic leaders establish an environment in which a cutthroat and cold attitude is institutionalised, and this elevates the level of psychopathy in the followers.

This idea postulates that when workers are exposed to leaders who possess the qualities of a Machiavellian, they tend to emulate the same behaviour, and one of the behaviours that is likely to emerge is the type that involves manipulating and exploiting others. When a leader uses the strategy of manipulation to achieve success in the organisation, employees are motivated to follow suit by becoming more toxic. Self-promotion, power seeking and obsessive preoccupation with oneself are behaviours that are rewarded by narcissistic leaders. By observing such behaviour, employees may come to view such narcissistic tendencies as attractive, and this may end up causing the employees to develop narcissistic tendencies. Psychopathic leaders can give their followers the grounds to act in a predatory way. Employees begin to imitate the approach of the leader and pay less attention to ethical, compassionate, and social behaviour, which leads to an overall increase in psychopathic characteristics in employees. As per this set of hypotheses, dark personalities in employees (Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy) cause them to project similar personalities onto their leaders. To illustrate, a very narcissistic worker can view his leader as a narcissist, which further proves the relationship between EDT and LDT.

4. Research Method

4.1. Research Design

The present research involved a mixed-methods research design (explanatory cross-sectional design), and the quantitative component was combined with a thematic follow-up. Specifically, the explanatory cross-sectional design is best suited for analysing the relationship between leader and employee dark traits in a higher education context. This design ensures that data are measured and captured only once, and this method also helps illustrate the effectiveness of the relationship between leaders and followers: the design process does not entail tracking the instrument over time (Kumar & Praveenakumar, 2025). The design is cross-sectional, such that multiple interactions between variables can be observed simultaneously, and scholars can devote their time to testing the hypothesis of how leader traits (LDT) influence employee traits (EDT). (Sreekumar & Sreekumar, 2023).

In addition, the inclusion of quantitative and qualitative data in a mixed-method approach helps ensure all research problem aspects are considered. The quantitative component helps determine the statistical connections between the characteristics of leaders and staff, whereas the qualitative component focuses on gaining a deeper understanding of the subject training and perceptions of staff in unhealthy leadership environments (Ghanad, 2023; Biggs et al., 2021). The thematic analysis strategy helps determine the themes that recur with respect to employee attitudes and reactions to the dark characteristics of their bosses (Furidha, 2023). This combination of methods makes the findings even more valid and substantial, as they are related to both quantitative and more profound knowledge about the organisational culture (Sardana et al., 2023).

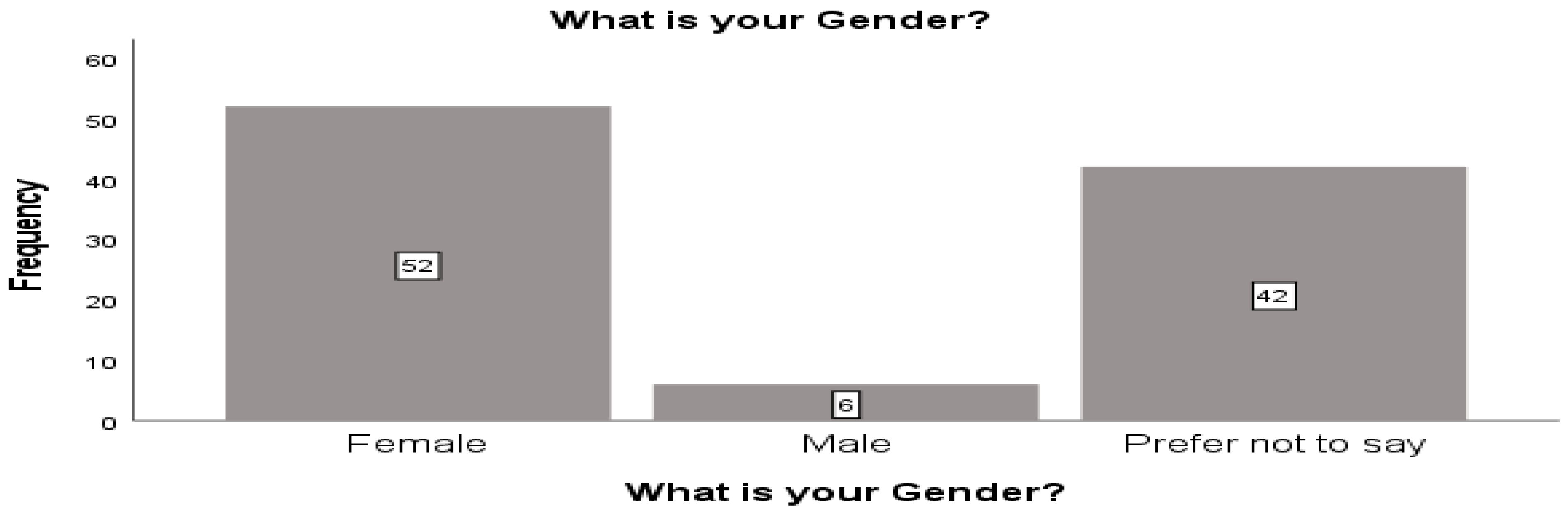

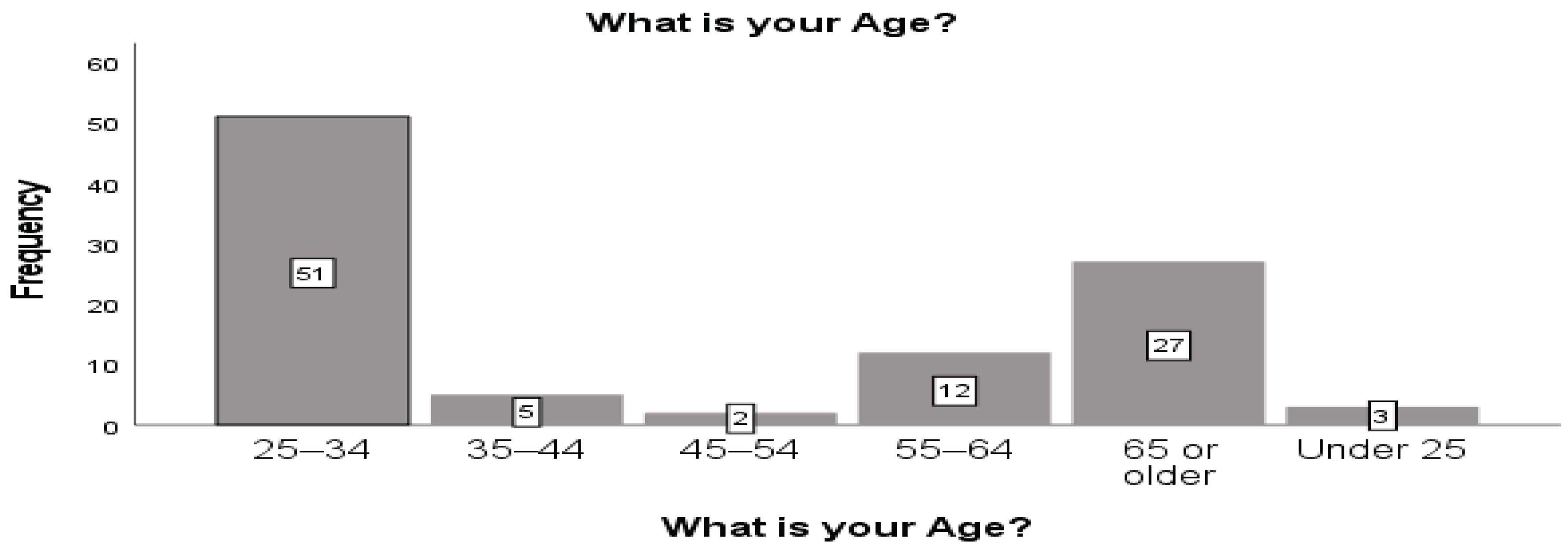

4.2. Sample

To perform the study, it was assumed that 100 personalities would be sampled among employees of institutions offering higher education, and they would represent a balanced representation across various academic disciplines and functions. Such a selection of the sample is very critical, since such interactions between dark leadership attributes (LDTs) and the attributes of employees, including dark traits (EDTs), are likely to vary across various organisational settings, such as academic schools (Hazari, 2024). The inclusion criteria of this sample included the following aspects:

Subjects must have worked in their present institution for at least 6 months so that they have acquired proper exposure to the leadership of their close superiors.

Enrollees must be participants in higher education institutions to be exposed to the peculiarities of academic leadership and worker relations (Bhangu et al., 2023).

Ethical considerations are followed by only employing employees who are interested in participating in the study and who provide informed consent.

The data collection process was performed in two phases. First, a survey was extended to all the subjects, outlining quantitative information about what people believe an individual and his or her leaders to be. Second, to develop a qualitative image of the experiences, 6 people were invited to be interviewed. This mixed approach was designed to triangulate the two methods and offer a valid perspective of the dynamics of the leader and their followers’ traits (Sreekumar & Sreekumar, 2023).

Ethical clearance was received before the study began from the corresponding institutional review board. The research procedure was conducted under the condition of anonymity and confidentiality, and all the data were anonymised prior to its analysis (Stommel & Rijk, 2021). The volunteers were informed that the process was voluntary and that they could drop out at any moment without facing any penalty (Mishra & Alok, 2022). The informed consent procedure ensured that all people associated with the research understood what the research was about, as well as the nature and rights of the participants involved in the research. Ethical guidelines also included the security of the data and privacy rules.

4.3. Measures

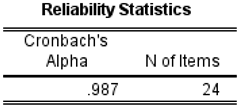

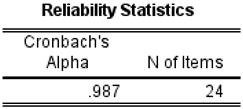

To gain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of Dark Triad (DT) manifestations across leadership and employee levels, this study expanded the original 12-item scales for Leader Dark Triad (LDT) and Employee Dark Triad (EDT) to 24 items each. The initial 12-item Dirty Dozen scale (Jonason & Webster, 2010) is efficient but limited in fully capturing the subtle behavioural, affective, and cognitive aspects of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. Hence, we incorporated an additional 12 items drawn from validated extensions, such as the Short Dark Triad (SD3) by Jones & Paulhus (2014) and complementary behavioural indicators from applied leadership studies.

This expansion enhances construct depth, improves scale reliability, and enables the study to distinguish performative traits from internalised dispositions — particularly relevant when assessing leader–employee dyads in organisational settings. By increasing item breadth, we ensure more robust measurement, reduce social desirability bias, and capture a broader spectrum of DT-driven behaviours observed in academic institutions.

The full 24-item list is an adaptation of the dirty dozen covering manipulation, deceit, emotional callousness, superficial charm, status obsession, and strategic amoral reasoning, all reworded to ensure clarity and alignment with the UAE higher education context. The authors suggest that the dirty dozen scale can be adaptive in any way along as it passes the scale reliability threshold.

4.4. Data analysis

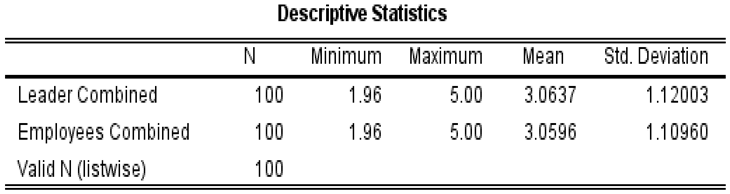

Analysis of the quantitatively measured data obtained from surveys was carried out using SPSS. The simple description or descriptive statistics illustrate the traits of leaders and employees, along with the means, standard deviations, and frequencies. This helps clarify the background characteristics of the sample and indicate any inclinations in the data (Furidha, 2023).

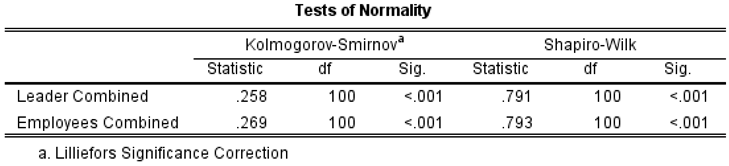

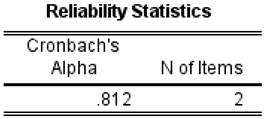

Reliability is then ensured through Cronbach's alpha, which ensures the reliability of the scales used to measure LDT and EDT. The acceptable range of alpha is equal to or greater than 0.7, and it is dedicated to making sure that the items in each of the sub-dimensions provided by the dark triad measure a single underlying construct (Ghanad, 2023).

To gain further support for the measurement model, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) or Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA were conducted. The techniques presented make it possible to check the structure of LDT and EDT factors, ensuring that the sub-dimensions (Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy) are adequately represented in data (Mishra & Alok, 2022). Because EFA can be used in the analysis of data structures, EFA was implemented initially, and CFA was utilised to test and establish the two-factor theory. Finally, thematic analysis will be used to analyse the qualitative text and recognize patterns and emerging themes.

7. Conclusion

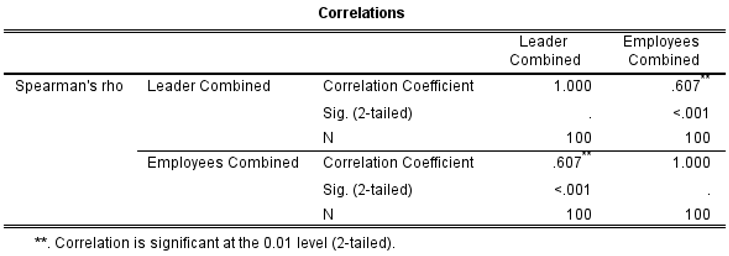

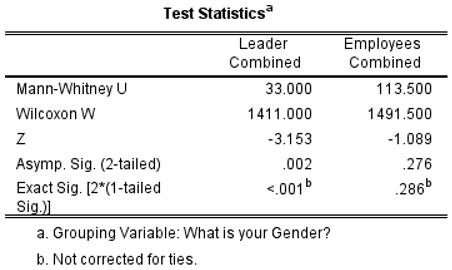

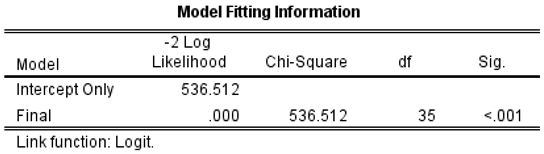

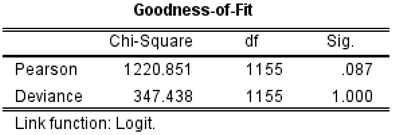

This research investigated the strong relationship between Leader Dark Triad (LDT) and Employee Dark Triad (EDT) traits in higher education institutions. Through a combination of quantitative data analysis and qualitative thematic insights, this study found strong evidence that dark leadership behaviours characterised by Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy are not only imposed downward but also mirrored, reinforced, and normalised by employee responses. A highly significant positive correlation between LDT and EDT (r = 0.881) confirmed a powerful behavioural alignment wherein traits in leadership strongly predict those in employees. Regression analysis further showed that approximately 77.6% of the variance in employee dark traits could be explained by corresponding leadership behaviours. These findings were further supported by qualitative accounts that revealed lived experiences of ethical compromise, mimicry, rationalisation, and cultural adaptation within toxic academic environments.

The main insight of this research is that dark leadership fosters dark followership. Leaders who exhibit exploitative, manipulative, or emotionally indifferent behaviours unintentionally create environments where such traits are rewarded or required for survival. Subordinates under this kind of leadership tend to develop the urge to follow suit by using defensive mimicry, psychological projection, or even passive compliance to win or fit in. Over time, such behaviours are institutionalised to the point of oblivion of moral distinctions between authority and subordination. Under these conditions, toxicity is no longer an anomaly but rather a cultural norm that, unveiled, defines the interactions and leadership of individuals and decision making.

At the core of these dynamics is the concept of psychological contagion, which this study recognised as one of the most important mechanisms of the spread of dark traits. It was also demonstrated that toxic behaviours are passed through role modelling, social learning, and shadow projection as employees unconsciously reflect or rationalise behaviours they see in their leaders. This is not merely a behavioural contagion; it is a cultural contagion that influences values, reduces ethical standards, and creates conditions in which manipulation, egoism, and moral disengagement flourish. When employees rationalised, such unethical behaviour using leadership precedent or institutional expectations, it was evident that the problem had not only been bad leadership but an entire system of collective complicity and adjustment.

However, such understandings require a more active and psychologically sensitive method of leadership and organisational development. Institutions need to invest in ethical leadership models, leadership profiling, and culture auditing to identify early warning signs of moral decay. Moreover, the issues need to be addressed not only at the policy level but also through a fundamental re-evaluation of assumptions regarding power, behaviour, and organisational success. To summarise, this study contributes to the understanding of the function of dark traits within institutional systems. It also shifts the focus on leadership per se to the interaction between leaders and followers. The mutual toxicity needs to be identified and broken to preserve both ethical integrity and mental health in higher learning institutions.

Appendix 2: Interview Questions

Theme 1: Toxic Role Modelling

1. Can you describe a time when you observed a leader engaging in manipulative or ethically questionable behaviour? What did you take away from that experience?

2. In your view, how do leadership behaviours influence the way employees act or make decisions in your institution?

3. Have you ever found yourself modelling your own actions on what you’ve seen leaders do, even if you initially disagreed with those behaviours? Why or why not?

Theme 2: Shadow Projection

4. Have there been situations where you felt critical of a leader's behaviour, but later realised you may have acted in a similar way?

5. To what extent do you think employees project their own feelings or attitudes onto their superiors? Can you share an example?

6. Have you ever noticed yourself rationalising your own questionable actions by comparing them to a leader’s conduct?

Theme 3: Defensive Imitation or Survival Strategy

7. Can you recall a time when you felt the need to “play along” with certain workplace behaviours or norms in order to be included or accepted?

8. Have you ever felt pressured to behave in a way that went against your personal values to secure professional opportunities or avoid exclusion?

9. What strategies do employees typically use to navigate toxic or politically charged work environments in your institution?

Theme 4: Legitimisation of Dark Behaviour

10. In your experience, are there behaviours that were initially seen as unacceptable but have become normalised over time? Can you give examples?

11. How do new employees respond when they first encounter these behaviours or cultural norms?

12. What role do organisational policies or culture play in reinforcing or discouraging dark or unethical behaviour?