Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

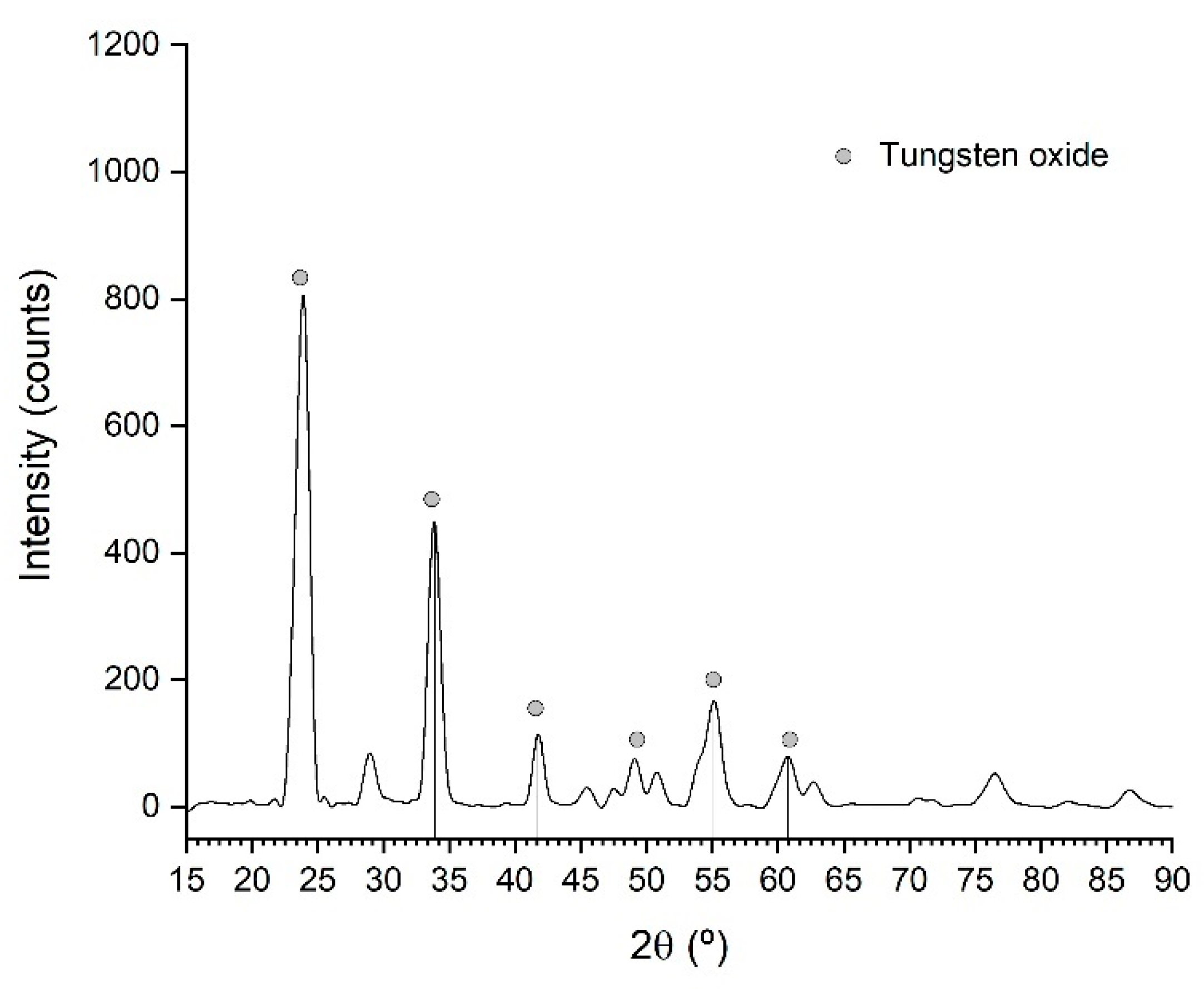

2.1. Material Characterization

2.2. Laboratory Scale Experiments

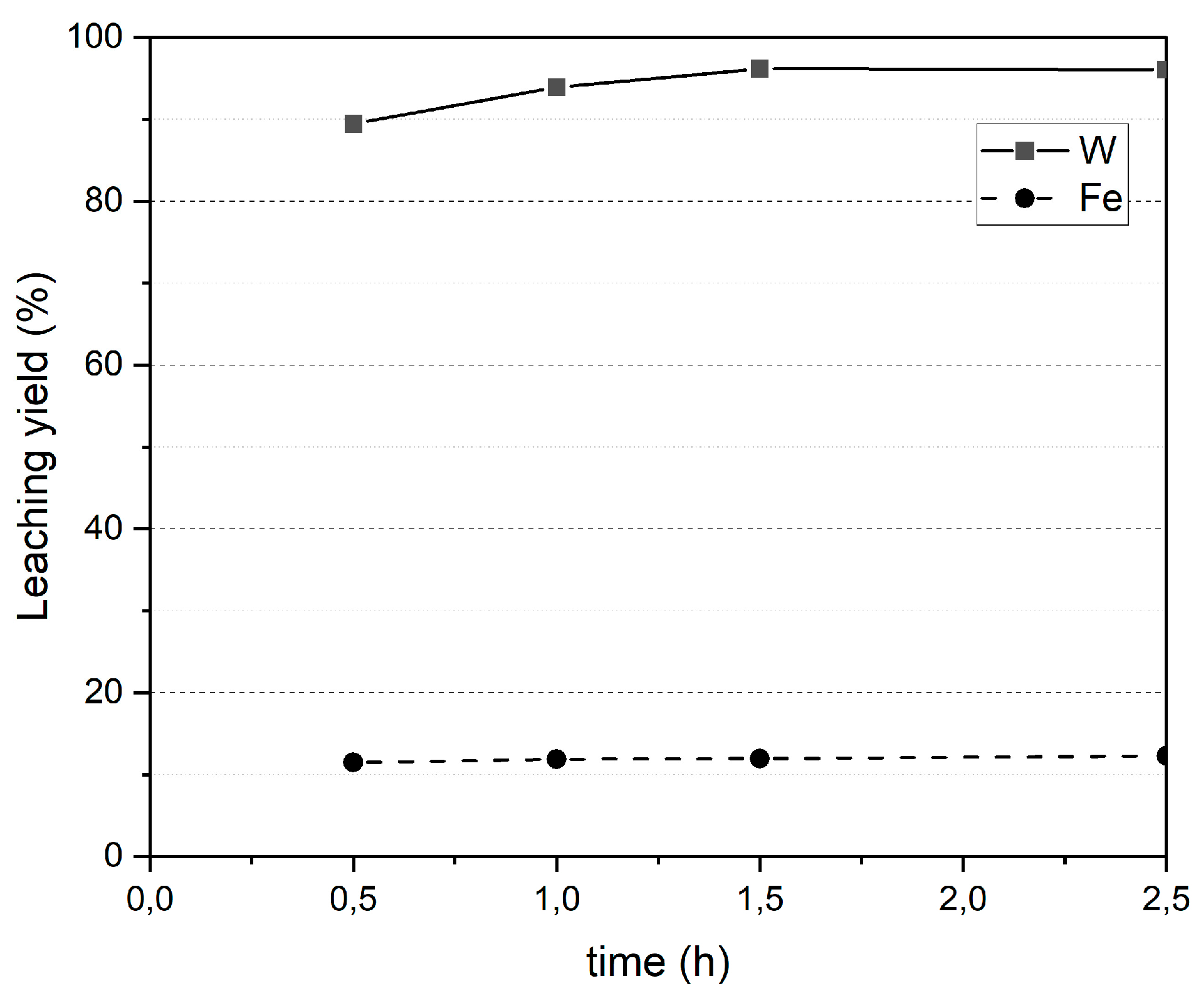

2.2.1. Leaching

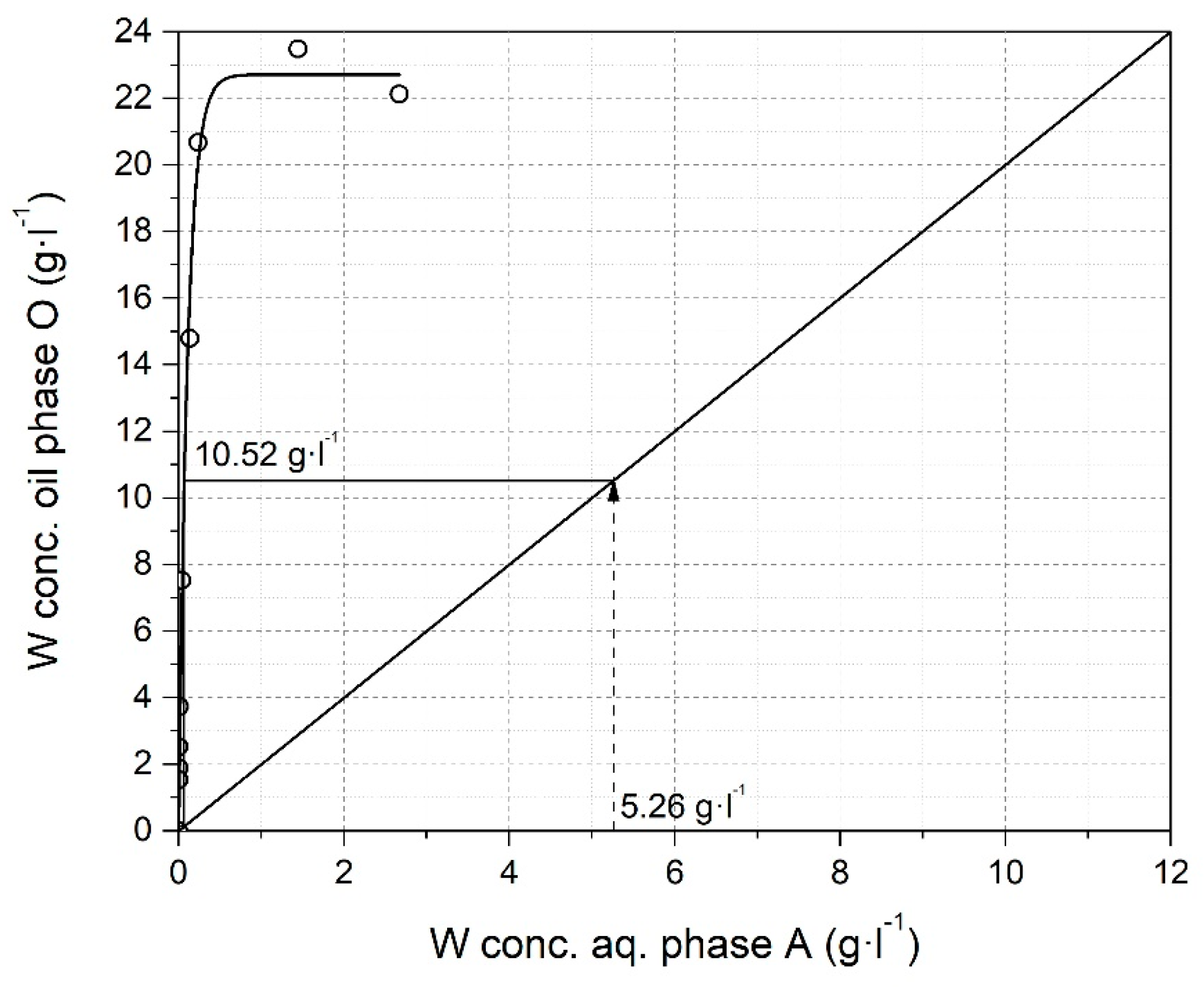

2.2.2. Solvent Extraction

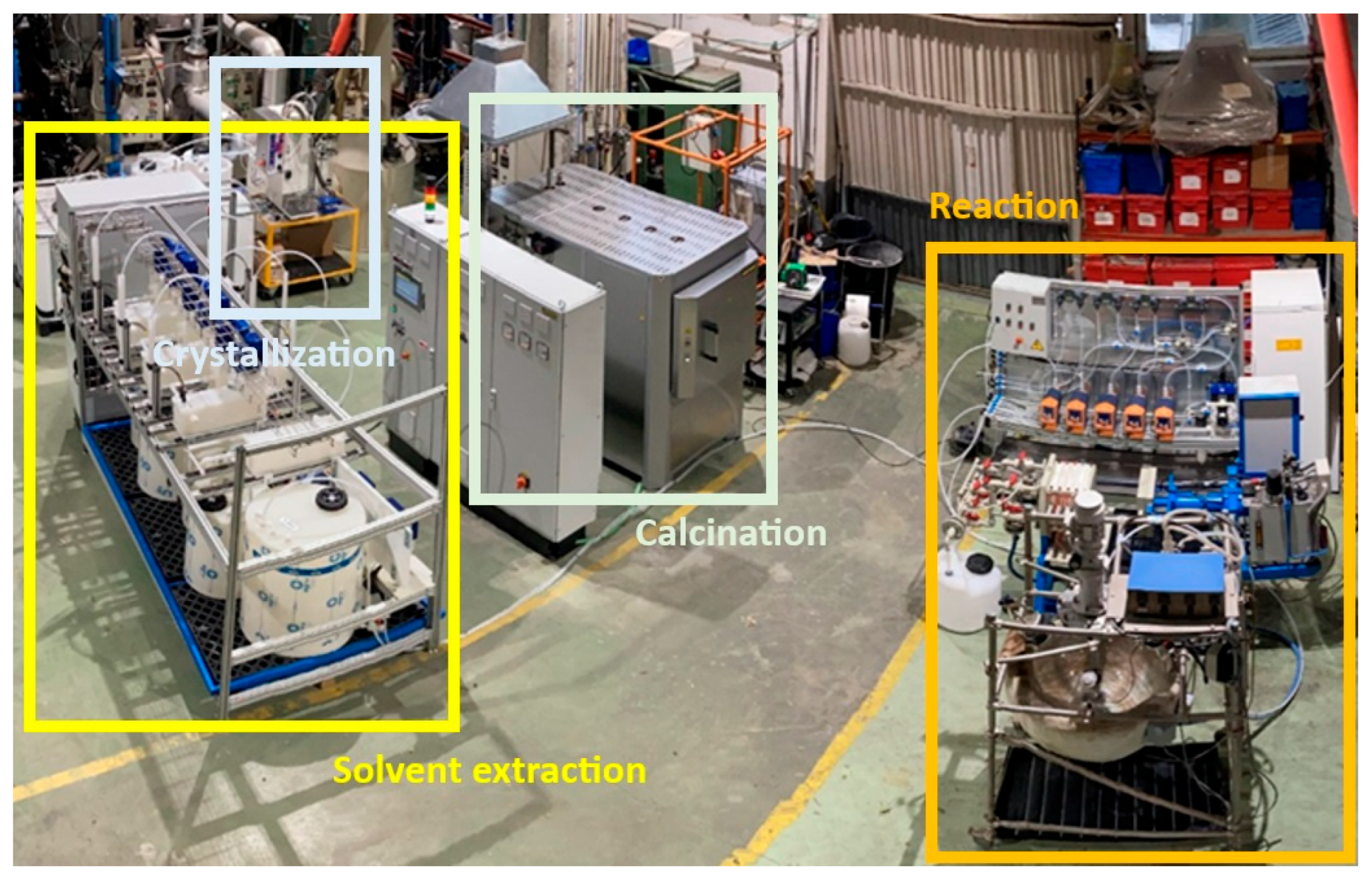

2.3. Pilot Plant Equipment and Operation

2.3.1. Pre-Treatment

2.3.2. Leaching

2.3.3. Solvent Extraction

2.3.4. Crystallization and Calcination

3. Results

3.1. Laboratory Scale Experiments

3.2. Pilot Plant Results

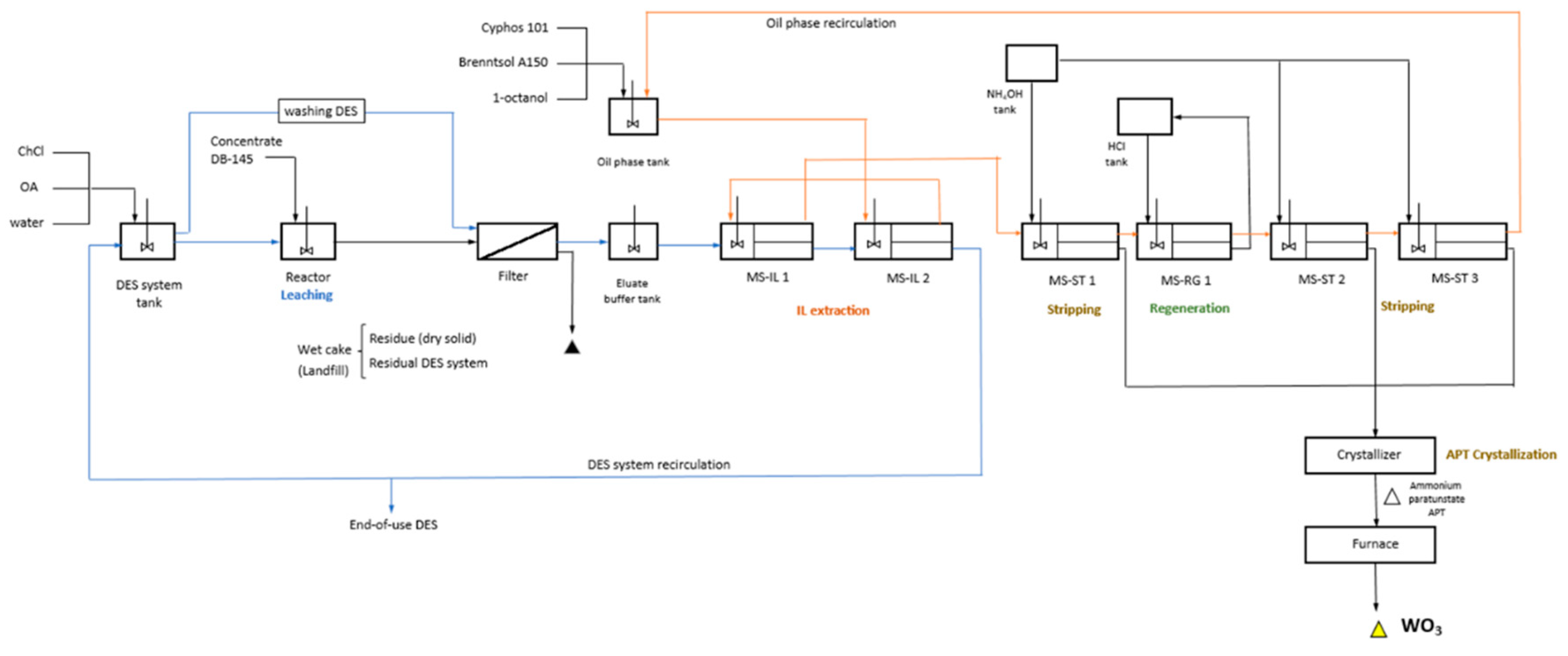

3.2.1. Flow-Sheet

3.2.2. Pilot Plant Conditions

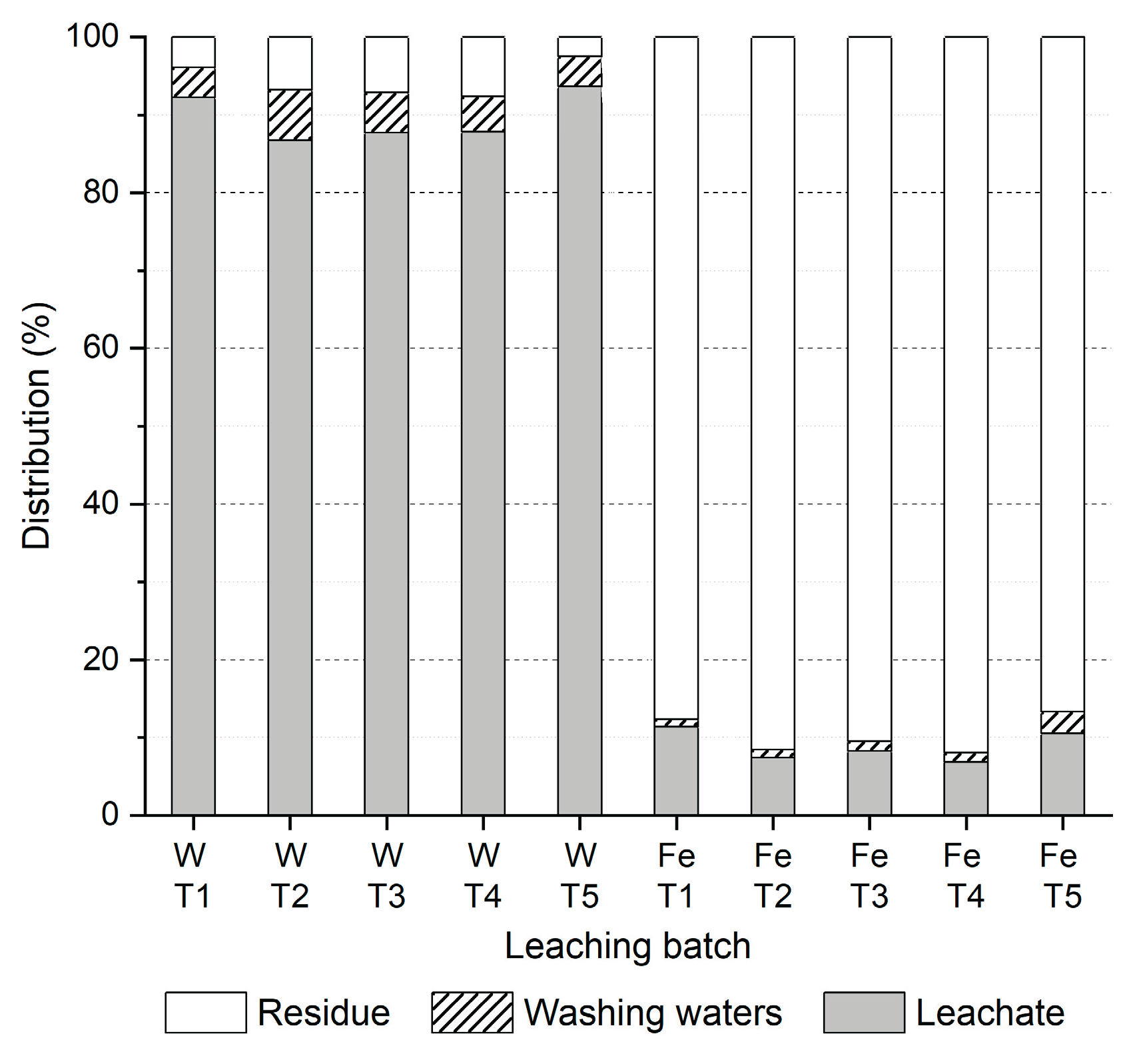

3.2.3. Leaching

3.2.4. Solvent Extraction

3.2.5. Crystallization and Calcination

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nieto, J.; Yurramendi, L.; Aldana, J.L.; del Río, C.; Siriwardana, A. A Process Based on Ionic Liquids for Tungsten Valorization from Low Grade Scheelite Concentrates . Proceedings of the ISEC 2022 Gothenburg Sweden 2023.

- Is Tungsten a Good Conductor of Electricity ? Available online: https://domadia.net/blog/is-tungsten-a-good-conductor-of-electricity/ (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Tungsten (W) - The Different Properties and Applications Available online: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=9119 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- China Dominates Tungsten Mine Production | China Is the Top Supplier of Tungsten While US Produces Zero - MINING.COM Available online: https://www.mining.com/web/tungsten-miner-says-clients-in-shock-as-china-chokes-supply/china-dominates-tungsten-mine-production-china-is-the-top-supplier-of-tungsten-while-us-produces-zero/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Foucaud, Y.; Filippov, L.; Filippova, I.; Badawi, M. The Challenge of Tungsten Skarn Processing by Froth Flotation: A Review. Front Chem 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D. Extraction of Tungsten from Scheelite Ore - 911Metallurgist Available online: https://www.911metallurgist.com/blog/extraction-tungsten-scheelite-ore/#Tungsten-TablingCircuit (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Ahn, H.H.; Lee, M.-S. Hydrometallurgical Processes for the Recovery of Tungsten from Ores and Secondary Resources. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Orefice, M.; Nguyen, V.T.; Raiguel, S.; Jones, P.T.; Binnemans, K. Solvometallurgical Process for the Recovery of Tungsten from Scheelite. Ind Eng Chem Res 2022, 61, 754–764. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z. Sustainable and Efficient Recovery of Tungsten from Wolframite in a Sulfuric Acid and Phosphoric Acid Mixed System. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 13583–13592. [CrossRef]

- YANG, J. hong; He, L. hua; Liu, X. heng; Ding, W. tao; SONG, Y. feng; ZHAO, Z. wei Comparative Kinetic Analysis of Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Leaching of Scheelite by Sodium Carbonate. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China (English Edition) 2018, 28, 775–782. [CrossRef]

- Spooren, J.; Wouters, W.; Michielsen, B.; Seftel, E.M.; Koelewijn, S.-F. Microwave-Assisted Alkaline Fusion Followed by Water-Leaching for the Selective Extraction of the Refractory Metals Tungsten, Niobium and Tantalum from Low-Grade Ores and Tailings. Miner Eng 2024, 217, 108963. [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, S.N.; Mookherjee, S.; Pardeshi, R.M. Current Practices in Tungsten Extraction and Recovery. High Temperature Materials and Processes 1990, 9, 147–162. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, K.; Li, Q.; He, J. Co-Extraction of Tungsten and Molybdenum from Refractory Scheelite – Powellite Blend Concentrates by Roasting with Na 2 CO 3 and SiO 2 and Leaching with Water. 2018, 4433. [CrossRef]

- SREENIVAS, T.; Srinivas, K.; NATARAJAN, R.; PADMANABHAN, N.P.H. An Integrated Process for the Recovery of Tungsten and Tin from a Combined Wolframite-Scheelite-Cassiterite Concentrate. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review 2010, July-Septe, 193–203. [CrossRef]

- Kalpakli, A.O.; Ilhan, S.; Kahruman, C.; Yusufoglu, I. Dissolution Behavior of Calcium Tungstate in Oxalic Acid Solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2012, 121–124, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Yurramendi, L.; Nieto, J.; Siriwardana, A. Recovery of Tungsten from Downstream Mineral Processing Fractions by Deep Eutectic Solvents. Mater. Proc. 2021, 5, 96. [CrossRef]

- 2: UNE-EN 13656, 1365; 17. AENOR UNE-EN 13656:2020 Soil, Treated Biowaste, Sludge and Waste - Digestion with a Hydrochloric (HCl), Nitric (HNO3) and Tetrafluoroboric (HBF4) or Hydrofluoric (HF) Acid Mixture for Subsequent Determination of Elements; 2020;

- Deferm, C.; Onghena, B.; Nguyen, V.T.; Banerjee, D.; Fransaer, J.; Binnemans, K. Non-Aqueous Solvent Extraction of Indium from an Ethylene Glycol Feed Solution by the Ionic Liquid Cyphos IL 101: Speciation Study and Continuous Counter-Current Process in Mixer-Settlers. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 24595–24612. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tulpatowicz, K.; Pranolo, Y.; Cheng, C.Y. Solvent Extraction of Molybdenum and Vanadium from Sulphate Solutions with Cyphos IL 101. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 154, 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Sinha, M.K.; Sahu, S.K.; Pandey, B.D. Solvent Extraction and Separation of Trivalent Lanthanides Using Cyphos IL 104, a Novel Phosphonium Ionic Liquid as Extractant. Solvent Extraction and Ion Exchange 2016, 34, 469–484. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Devi, N. Separation and Recovery of Gallium(III) Ions from Aqueous Phase by Liquid–Liquid Extraction Using a Novel Extractant, Cyphos IL 101. Turk J Chem 2017, 41, 892–903. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Seara, J.; Sieres, J.; Rodríguez, C.; Vázquez, M. Ammonia-Water Absorption in Vertical Tubular Absorbers. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2005, 44, 277–288. [CrossRef]

- Hadlocon, L.J.; Zhao, L. Production of Ammonium Sulfate Fertilizer Using Acid Spray Wet Scrubbers; 2015;

| W | Si | Al | Fe | K | Ca | Na | |

| Conc. (%) | 2.6 | 31.5 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| Stage | Conditions |

| Leaching | T 60 °C time 1h L/S ratio 5 |

| IL Extraction Stripping Regeneration |

IL Extraction Oil phase:

Stripping NH3 1M (first mixer settler) NH3 0.5M (2nd and 3rd mixer settlers) O/A 1:1 Regeneration HCl 1M O/A 1:1 |

| Crystallization | T 105 °C |

| Calcination | T 650 °C time 1h |

| EXTRACTION | W | Fe |

| EXTRACTION | 97.6 | 5.0 |

| STRIPPING | 98.3 | 14.2 |

| REGENERATION | -0.2 | - |

| OVERALL | 95.7 | 0.3 |

| WO3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | Rest |

| 99.30 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).