Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Software Description

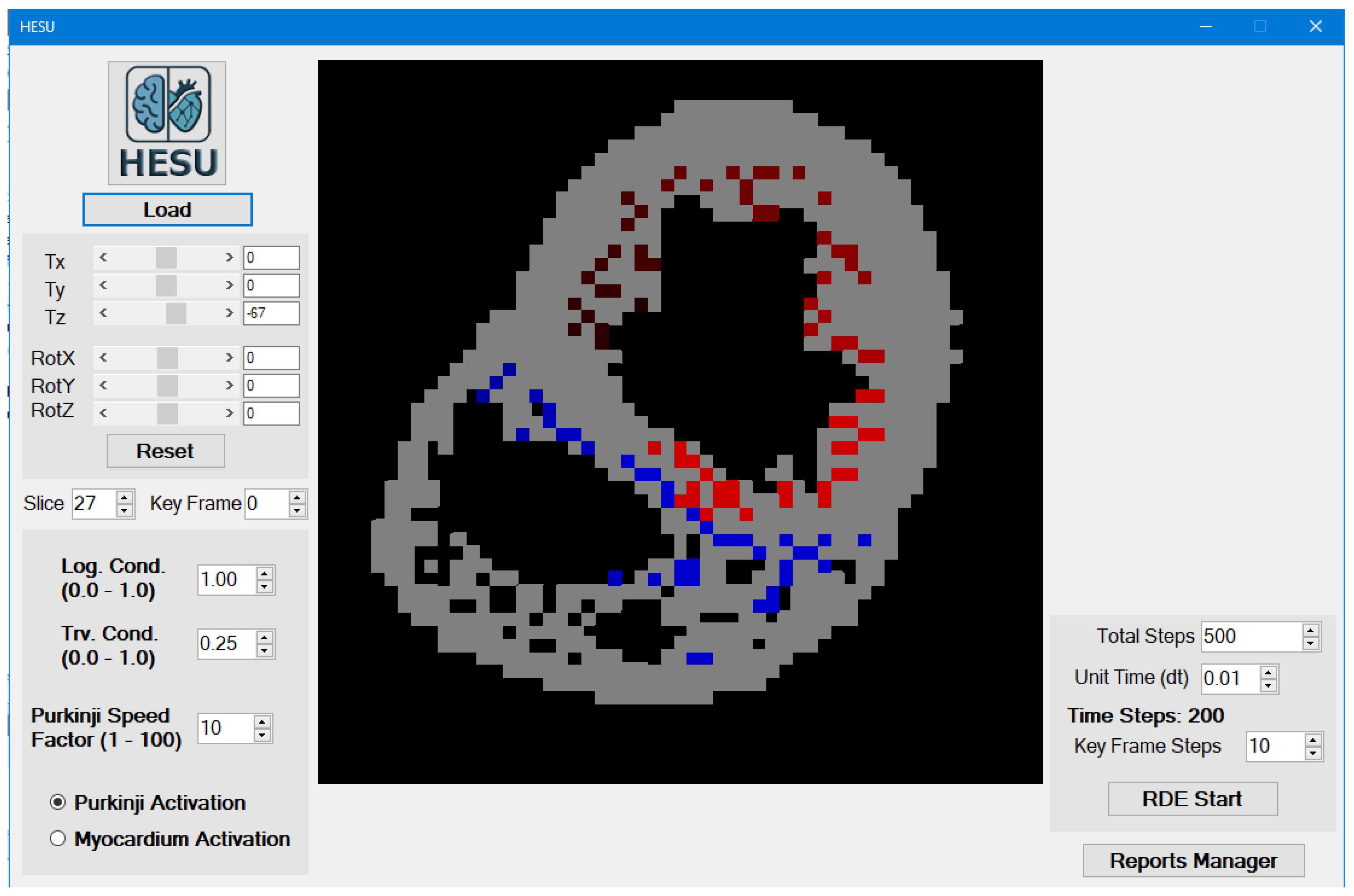

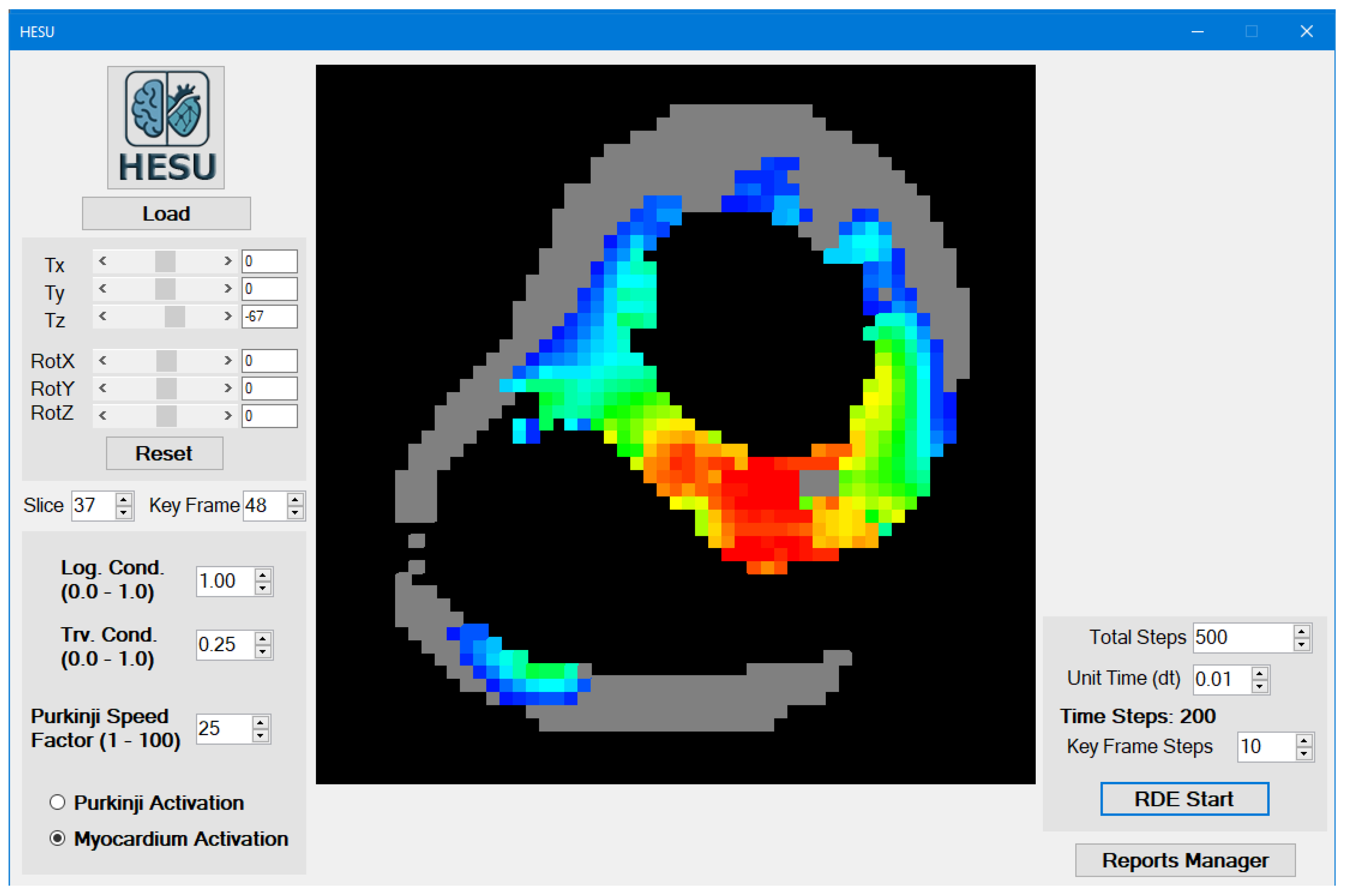

3.1. Main Form Interface

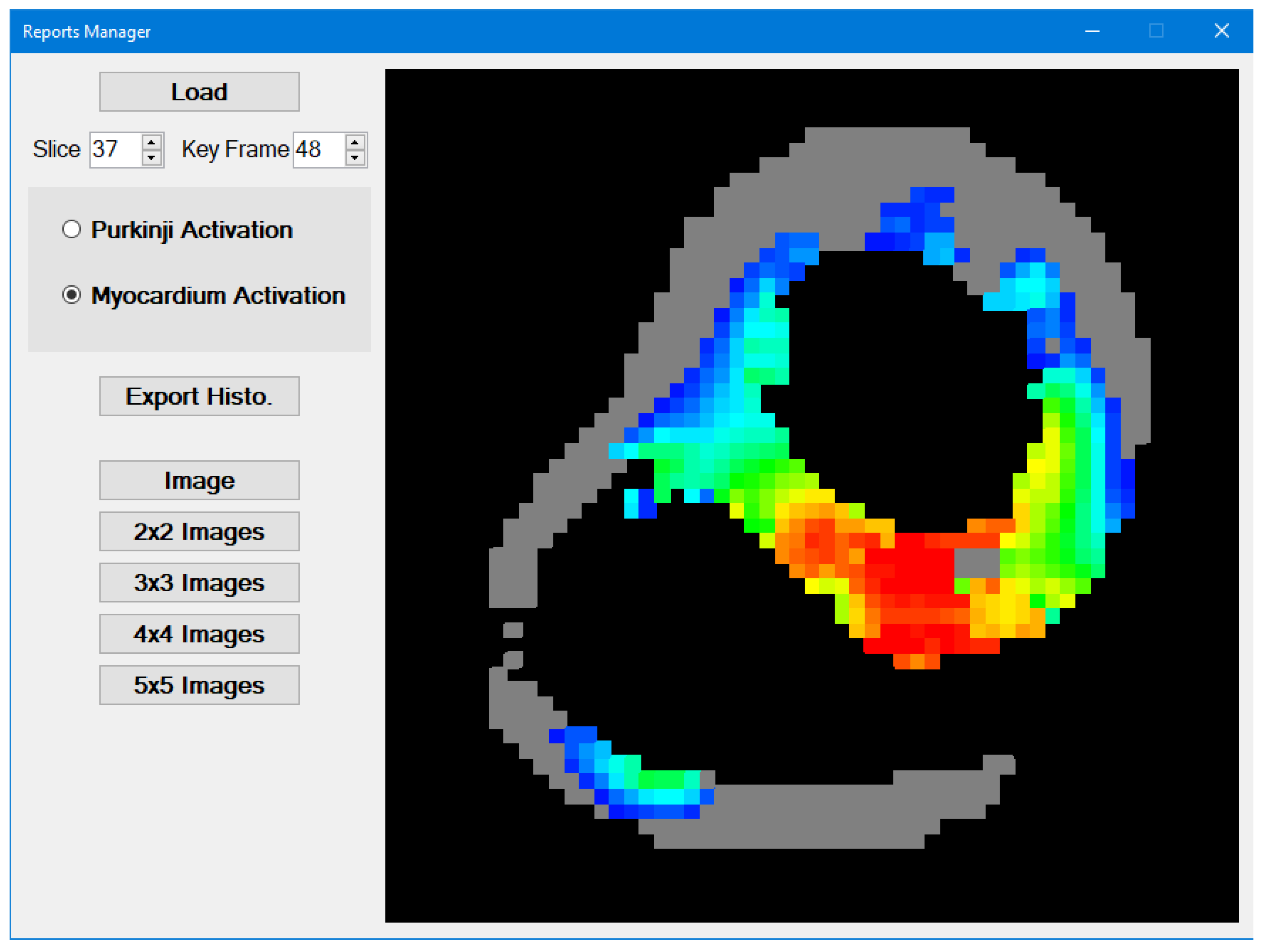

3.2. Reports Manager

4. Conclusions

- License

Acknowledgments

References

- A.E. Pollard and R.C. Barr "The Construction of an Anatomically Based Model of the Human Ventricular Conduction System" IEEE Trans. Biom. Eng. (1990); 37(12): 1173-1185.

- X. Zhang, I. Ramachandra, Z. Liu, B. Muneer, S.M. Pogwizd, and B. He "Noninvasive three-dimensional electrocardiographic imaging of ventricular activation sequence" Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol (2005); 289: H2724–H2732.

- T. Berger, G. Fischer, B. Pfeifer, R. Modre, F. Hanser,T. Trieb, F. X. Roithinger, M. Stuehlinger, O. Pachinger,B. Tilg, and F. Hintringer "Single-Beat Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology of Ventricular Pre-Excitation" J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (2006);48:2045-2052. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of the Human Heart in 3D Using DTI Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2025, 15(02), 2450-2459. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Mall "On The Muscular Architecture of the Ventricles of the Human Heart" The American Journal of Anatomy (1911); vol. 11(3):211-266.

- K. Simeliusa, J. Nenonena, M. Horácekb "Modeling Cardiac Ventricular Activation" Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism, (2001); 3(2):51 - 58.

- B.H. Smaill, I.J. LeGrice, D.A. Hooks, A.J. Pullan, B.J. Caldwell and P.J. Hunter "Cardiac structure and electrical activation: Models and measurement" Proc. of the Australian Physiological and Pharmacological Society, (2004); 34: 141-149.

- P.M.F. Nielsen, I.J. Le Grice, B.H. Smaill, and P.J. Hunter "Mathematical model of geometry and fibrous structure of the heart" The Am. Phys. Soc. (1991); 260: H1365-H1378.

- L.W. Wang, H.Y. Zhang, P.C. Shi "Simultaneous Recovery of Three-dimensional Myocardial Conductivity and Electrophysiological Dynamics: A Nonlinear System Approach" Computers in Cardiology, (2006);33:45-48.

- J.M. Peyrat, M. Sermesant, X. Pennec, H. Delingette, C. Xu, E. McVeigh and N. Ayache "Statistical Comparison of Cardiac Fibre Architectures", FIMH (2007); 4466: 413-423.

- L. Zhukov, A.H. Barr "Heart-Muscle Fibre Reconstruction from Diffusion Tensor MRI" VIS 2003. IEEE, (2003); Conf. Proc.: 597-602.

- R.L. Winslow, D.F. Scollan, J.L. Greenstein, C.K. Yung, W. Baumgartner, G. Bhanot, D.L. Gresh and B.E. Rogowitz "Mapping, modeling,and visual exploration of structure-function relationships in the heart" IBM Sys J.,(2001); 40(2):342-359.

- M. Sermesant , H. Delingette, and N. Ayache "An Electromechanical Model of the Heart for Image Analysis and Simulation" IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. (2006); 25(5): 612-625.

- Elaff, I. “Medical Image Enhancement Based on Volumetric Tissue Segmentation Fusion (Uni-Stable 3D Method)”, Journal of Science, Technology and Engineering Research, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 78–89, 2023. [CrossRef]

- [S.Tawara "The Conduction System of the Mammalian Heart" English Ed., World Scientific Pub. co., (1998), ISBN: 981023502X.

- [G.K. Massing, and T.N. James "Anatomical Configuration of the His Bundle and Bundle Branches in the Human Heart" Circ. (1976); 53(4):609-621.

- D. Durrer, R.TH. Van Dam, G.E. Freud, M.J. Janse, F.L. Meijler and R.C. Arzbaecher "Total Excitation of the Isolated Human Heart" Circulation, (1970); 41(6):899-912.

- El-Aff, I.A.I. "Extraction of human heart conduction network from diffusion tensor MRI" The 7th IASTED International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, 217-22.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling the Human Heart Conduction Network in 3D using DTI Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2025, 15(02), 2565–2575. [CrossRef]

- O. Berenfeld and J. Jalife "Purkinje-Muscle Reentry as a Mechanism of Polymorphic Ventricular, Arrhythmias in a 3-Dimensional Model of the Ventricles" Circ. Res., (1998);82;1063-1077.

- D.S. Farina, O. Skipa, C. Kaltwasser, O. Dossel and W.R. Bauer "Personalized Model of Cardiac Electrophysiology of a Patient" IJBEM (2005);7(1): 303-306.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of The Excitation Propagation of The Human Heart”, World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 2025, 22(02): 512–519. [CrossRef]

- R. Fitzhugh "Impulses and Physiological States in Theoretical Models of Nerve Membrane" Biophysical J., 1961; 1: 445-466.

- R.R. Aliev, A.V. Panfilov "A simple two-variable model of cardiac excitation." Chaos, Solitons and Fractals, 1996; 7(3): 293-301.

- A. V. Panfilov, P. Hogeweg "Spiral breakup in a modified FitzHugh—Nagumo model" Phys. Let. A, 1993; 176: 295—299.

- A.T. Winfree "Varieties of spiral wave behavior: An experimentalist’s approach to the theory of excitable media" CHAOS ,(1991) ;1(3): 303-334.

- The Center for Cardiovascular Bioinformatics and Modeling, John Hopkins University Site "http://www.ccbm.jhu.edu/research/DTMRIDS.php", July 2011.

- Elaff, I. "Modeling of 3D Fibers Structure of Human Heart Using DTI Images and Moving Weighted Effective Sphere (MWES) Filter" ,PrePrints,2025. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).