1. Introduction

Education is a fundamental element for the individual and social development and progress of the person (Martínez Ortiz, 2022; Osorio Guzmán & Hernández Neri, 2023; Valle, 2020;). It is considered a key tool for the training of people, instilling appropriate values and behaviours (Martínez Ortiz, 2022), as well as for the transmission of knowledge and the pursuit of excellence (Valle, 2020). It also fosters critical thinking, personal growth and social transformation (Osorio Guzmán & Hernández Neri, 2023).

In this sense, there are many variables that come together in a classroom so that a pupil can develop fully and at his or her own pace of learning. The combination of these variables will result in school success or failure, which in turn will influence the pupil's capacity for social adaptation, not only in their academic stage, but also in their subsequent development as a citizen and active member of society. This will have a particular impact on the individual's self-concept and self-esteem (Martínez-Vicente et al., 2019) and even a mediating role in motivation and self-esteem (Quílez-Robres et al., 2021). Among the most important variables, personal, social, economic and family factors stand out (Sánchez & Miguel, 2011). Specifically, among the personal variables, the development of executive functions and academic performance stand out, aspects that have a significant impact on the adequate development of the individual in his or her environment.

Executive Functions: Definition and Dimensions

Executive functions were defined by Muriel Lezak (1982) as capacities necessary for effective, creative and socially adapted behaviour. This definition has been extended to include interrelated processes acting hierarchically, particularly from the prefrontal cortex, as has been shown in research with both normotypic and brain-damaged populations (Delgado Mejía & Etchepareborda Simonini, 2013; Stuss & Knight, 2013).

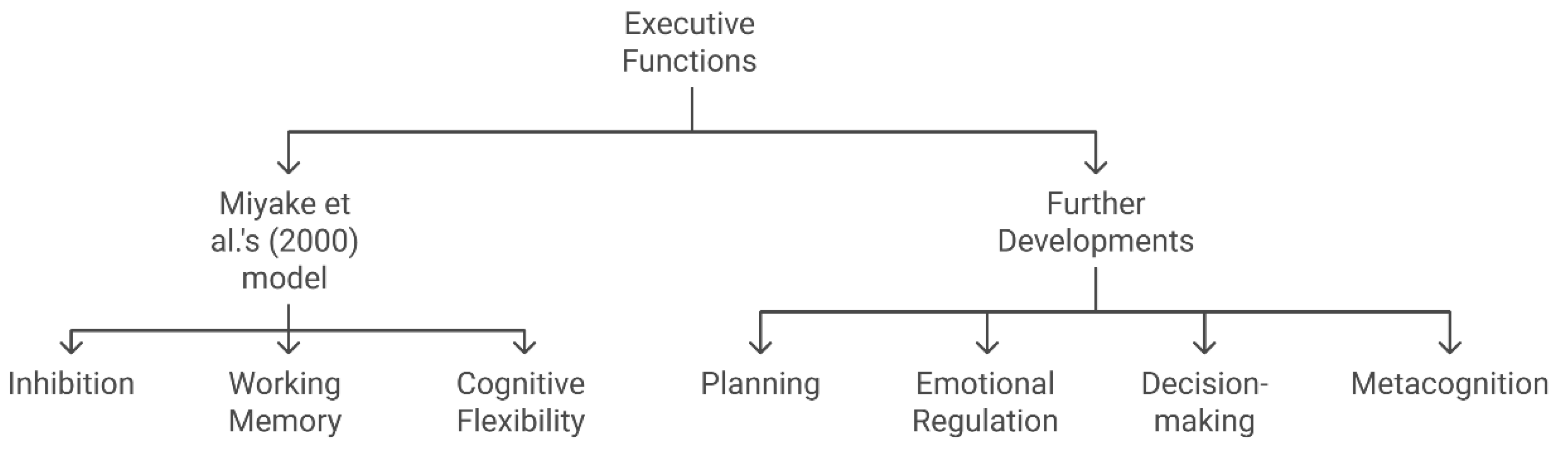

In this sense, executive functions comprise a group of higher-order mental processes involved in the regulation of goal-oriented behaviour, emotional self-regulation, complex problem solving and decision-making (Barkley, 2012; Diamond, 2013). These capacities are essential for responding appropriately to dynamic and changing environments, inhibiting impulsive behaviour, anticipating and planning actions, and regulating one's own behaviour. The model proposed by Miyake et al. (2000) identifies three basic dimensions: inhibition, working memory and cognitive flexibility, which act together and in coordination to facilitate executive functioning, although they can and should also be analysed separately in experimental studies (Zorza et al., 2016).

Subsequent developments of this research have complemented and deepened this model, proposing an integrative perspective that includes additional dimensions such as planning, emotional regulation, decision-making and metacognition (Munakata et al., 2011; Zelazo et al., 2016). These skills are essential for self-regulation, making behavioural adjustments in response to stimulus and environmental changes, as well as perseverance towards short- and long-term goals (Lara Nieto-Márquez et al., 2021). In addition, sub-processes such as planning, initiative, emotional control, task monitoring, organisation of materials and self-control have been identified as key functions in school settings (Gioia et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2021; Tirapu et al., 2017;). Thus, the correct assessment and understanding of their development allows for a better understanding of the involvement of executive functions in learning processes.

On the other hand, more recent research has highlighted the role of processing speed as a modulator of executive functioning, influencing the efficiency with which processes such as information updating and attentional switching take place (Dvoinin & Trotskaya, 2022; Lépine et al., 2005; Traverso et al., 2021). This discovery has revitalised interest in exploring the interaction between executive functions and more basic cognitive abilities.

Parallel to these findings, a more dynamic and hierarchical view of executive functions is gaining interest and prominence. From this point of view, executive functions are understood as the result of coordination between different neural networks. Evidence from neuroscience and neuroimaging studies supports this idea, showing that executive control involves a complex interaction between the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia and attentional systems (Dajani & Uddin, 2015; Friedman & Miyake, 2017).

Development of Executive Functions in the School Years

The development of executive functions in childhood does not follow a uniform pattern, but presents a progressive evolution, determined by biological and environmental factors (Best & Miller, 2010). Some functions, such as planning and organisation, peak between the ages of 6 and 8; inhibitory control tends to consolidate between the ages of 12 and 14; while other functions, such as working memory and cognitive flexibility, continue to mature until late adolescence (Portellano, 2005). This progress has been observed in parallel with synaptic maturation of the prefrontal lobe and increased cognitive demands in the school context (Anderson, 2002).

In this regard, it is important to note that there is well-established evidence that executive functions can be trained through appropriately designed pedagogical programmes. Benzing et al. (2019), for example, showed that an intervention that integrated physical activity with cognitive components produced improvements in working memory and sustained attention. Similarly, Diamond and Ling (2016) observed persistent positive effects on different executive functions through programmes that combined play, physical exercise and mindfulness practices. On the other hand, some authors have found significant improvements in attention and inhibitory control by incorporating active breaks during learning moments. These breaks are understood as programmed physical activities lasting between 1 and 10 minutes, carried out during classes or during transitions between classes (Méndez-Giménez & Pallasá-Manteca, 2023). Other studies have assessed inhibitory control simultaneously with the recording of brain activation, showing a positive association with academic performance, particularly in the area of mathematics. These findings support its central role as a key executive function (Papasideris et al., 2021).

On the other hand, it is necessary to mention that some studies highlight the determining influence of the family and school environment on executive development. Variables such as the educational and cultural level of parents, attachment styles, cognitive stimulation at home and the quality of peer interactions are positioned as influential factors in the degree and form of development of executive functions and, therefore, in the way of dealing with everyday and exceptional life situations (Martínez-Pons, 2020; Meza, 2017; Ursache et al., 2020).

Executive Functions and Academic Performance: An Established Link

Academic achievement is a complex concept that reflects a student's level of attainment in relation to set educational goals. Traditionally, it has been measured through numerical grades obtained in tests and assignments, although more recent approaches take into consideration other factors such as skills, competences and attitudes. According to Jiménez (2000), academic achievement can be defined as the level of knowledge demonstrated in an area or subject, compared to the norm for age and academic level. This concept therefore encompasses not only quantitative results, but also the interaction of cognitive abilities, effort and educational context (Grasso Imig, 2020).

The relationship between executive functions and academic performance is well established in the current scientific literature. Higher-order cognitive functions are considered stable and consistent predictors of academic performance, with even greater predictive ability than general intelligence indices (Best et al., 2011; Lenhard & Daseking, 2022). Thus, executive functions allow students to organise their work, avoid distractions, manage their emotions and monitor their progress in school tasks.

Specifically, verbal working memory has been found to predict performance in reading comprehension, while visuospatial working memory is associated with performance on mathematical tasks (de Vink et al., 2024; Farhi et al.,2024; Peng et al., 2016; Reina-Reina et al., 2023; Swanson & Jerman, 2007). These links have been replicated in a number of countries, including in Latin America. For example, a study in Mexico by Caso-Niebla and Hernández-Guzmán (2007) found that executive functions accounted for a significant part of the school results of primary school students. Similarly, it has been shown that executive functions predict overall academic performance in primary school, through processes such as phonological fluency, cognitive flexibility and inhibition (Perpiñá Martí et al., 2023; Porto Torres et al., 2021). Thus, recognition, mental representation and problem solving are skills directly facilitated by these functions (Reyes Cerillo et al., 2015).

The systematic review by Cortés Pascual et al. (2019) reinforces these results, showing that interventions and training focused on executive functions especially benefit students with vulnerable socioeconomic situations. This finding supports the idea that executive training can have a compensatory and equity-facilitating effect.

Other studies have highlighted the mediating role of emotional self-regulation and attentional control in improving academic performance. For example, De Miguel Sanz et al. (2017) found that emotional management and assertiveness favoured school performance in both primary and secondary school. In turn, Ramallo et al. (2021) found that students with better sustained attention scores and lower impulsivity showed better academic results.

Jacob and Parkinson (2015) highlighted that executive functions mediate the relationship between intrinsic motivation, self-regulation of learning and the construction of effective study habits.

Executive Functions, Social Skills and School Competence

Beyond their influence on academic learning, executive functions play an essential role in social adaptation and school integration. Skills such as emotional self-regulation, sustained attention and inhibition of inappropriate responses are fundamental for developing positive interpersonal relationships, resolving conflicts and participating constructively in the educational context (Blair, 2002; Muñoz-Parreño et al., 2023; Tur-Porcar et al., 2004).

Within the set of studies reviewed, several of them highlight the relationship between executive functions and communicative styles. For example, De la Torre et al. (2021) found that children with higher attention span tended to adopt more assertive communication styles and showed lower levels of aggression.

In this sense, interventions that combine the development of social skills with the strengthening of executive functions have been shown to be effective in improving both academic performance and school behaviour (Domitrovich et al., 2017; Landazábal, 1999; Spivack & Shure, 1974). Such programmes not only promote learning but also enhance students' emotional well-being and the overall classroom climate.

In the light of the above, it is essential to consider the influence of executive functions on the academic performance of primary school students. This systematic review aims to analyse the research that has addressed and explored the relationship between executive functions and academic performance in primary education, in order to identify the main executive processes associated with academic performance, as well as the strategies that may favour learning.

This systematic review aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. According to the available scientific evidence, how are executive functions related to academic performance in primary school students?

RQ2. What are the specific executive processes that are most closely related to academic performance at this level of education?

RQ3. What strategies or interventions based on executive functions have been shown to be effective in enhancing learning in primary education?

RQ4. What are the main limitations identified in the research analysed?

2. Methods

Study Design

This study was developed following the systematic review methodology, in accordance with the guidelines of the PRISMA 2020 model (Page et al., 2021), with the aim of identifying, evaluating and synthesising the empirical evidence available over the last decade (2015-2024) on the relationship between executive functions and academic performance in Primary School students.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection criteria for the studies were established a priori and grouped into five categories:

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Category |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

| Content |

Studies analysing the relationship between executive functions and academic performance. |

Studies that do not directly address executive functions or their link to performance. |

| Time period |

Articles published between 2015 and 2024 (both inclusive). |

Studies published before 2015 or after 2024. |

| Population |

Research focused on Primary Education students. |

Studies on early childhood education, secondary education, vocational training or higher education. |

| Type of document |

Original, peer-reviewed, open access scientific articles. |

Abstracts, posters, symposia, short communications, theses or conference proceedings. |

| Language |

English and Spanish |

All other languages other than English and Spanish. |

Search Strategy

The systematic search was carried out between February and April 2025 in the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science (WoS) and ProQuest, considering both the quality of the articles indexed in them and their broad thematic and geographical scope. To this end, descriptors representative of the object of study were used, applying filters of document type, language and period of publication. The terms used and the results obtained in each database are detailed below:

Table 2.

Search strategy by database.

Table 2.

Search strategy by database.

| Database |

Descriptors used |

Filters applied |

No. of results |

Date last searched or consulted |

| ProQuest |

funciones ejecutivas AND rendimiento académico AND educación primaria |

Articles in scientific journals, open access, last 10 years |

219 |

25/3/2025 |

| Scopus |

executive AND functions AND academic AND performance AND primary AND school |

Articles in scientific journals, open access, last 10 years |

116 |

25/3/2025 |

| Web of Science (WoS) |

executive functions AND academic performance AND primary school |

Articles in scientific journals, open access, last 10 years |

216 |

25/3/2025 |

The strategy was progressively refined to increase the sensitivity of the search without compromising subject specificity.

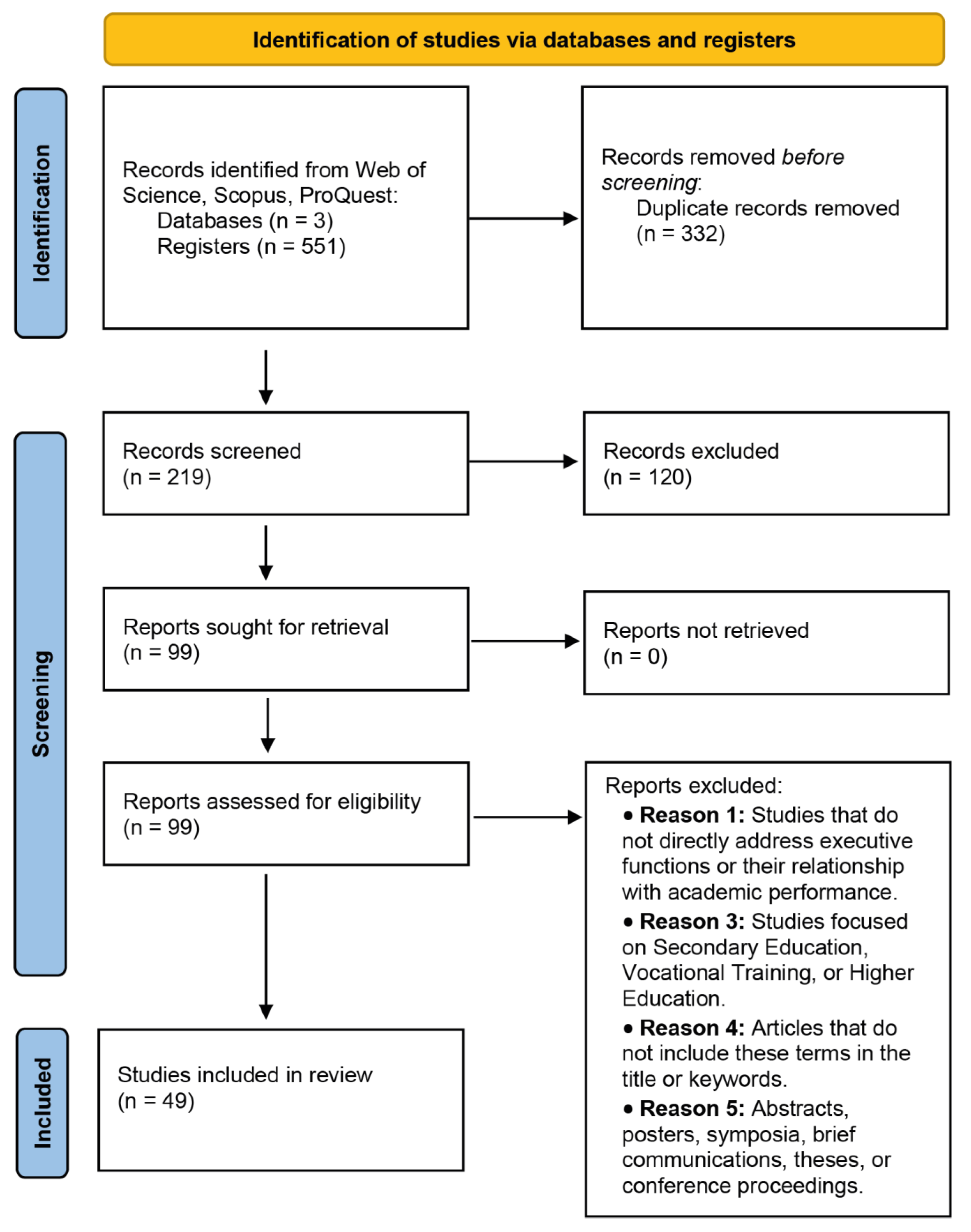

Selection Process. PRISMA Flowchart

The article selection process was carried out in three phases:

Identification: 219 studies were initially retrieved from ProQuest, 116 from Scopus and 216 from Web of Science.

Filtering: inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to titles and abstracts, as well as elimination of repeated papers. The review of the articles was conducted jointly by at least two of the researchers, assessing their suitability based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria through the examination of the title, keywords, abstract, and conclusions.

Full assessment: the full texts of the selected articles were reviewed. Finally, 49 studies met all criteria and were included in the qualitative analysis.

Appendix A lists the 49 articles resulting from the search and application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The PRISMA flowchart summarising the process of study identification, selection, eligibility and inclusion is presented below (

Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Explanatory diagram of the components of executive functions and their subsequent developments.

Figure 1.

Explanatory diagram of the components of executive functions and their subsequent developments.

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020 flow chart.

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020 flow chart.

3. Results

The synthesis of the 49 included studies provided detailed answers to the four research questions. Most of the studies were quantitative in approach (n = 38), while others used qualitative or mixed approaches (n = 11), which allowed for a broad and complementary view of the phenomenon. The findings are presented below, grouped according to the different research questions.

RQ1. According to the available scientific evidence, how are executive functions related to academic performance in primary school students?

The review carried out solidly confirms the existence of a close, complex and multifactorial relationship between executive functions and academic performance in primary school students. Executive functions not only act as predictors of academic success, but also mediate multiple learning processes, school adaptation and socioemotional functioning of students.

The results of the studies analysed repeatedly show that executive functions are significantly associated with performance in core subjects such as language and mathematics (Suárez-Riveiro et al., 2020). Moreover, deficits in these higher-order cognitive skills imply poor academic performance and school frustration (Ibagón Rojas & Villarreal Buitrago, 2022). Working memory, both verbal and visuospatial, is presented as the strongest indicator of academic performance. In this regard, several studies agree that students with a greater ability to retain, manipulate and update information tend to achieve higher scores in reading comprehension and solving complex mathematical problems (Benzing et al., 2019; Sankalaite et al., 2023; Swanson & Jerman, 2007; Traverso et al., 2018) or verbal mathematics with semantic inconsistencies (Passolunghi et al., 2022). Some work adds working memory and self-regulation as better predictors of academic achievement (Blume et al., 2022).

Inhibitory control plays a decisive role in behavioural self-regulation, enabling students to resist distracting stimuli, inhibit impulsive responses and maintain sustained attention in demanding academic tasks. This ability has been related to better performance in both standardised assessments and daily classroom behaviour (Ramallo et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2020).

As for cognitive flexibility, although it has been less explored in isolation, it is recognised as a relevant factor for adaptation to changing school contexts. Its development allows for modifying strategies, switching between different tasks and adjusting behaviour in the face of new demands, which favours meaningful learning and effective problem solving (López Villalobos et al., 2021; Pérez-López et al., 2018; Porto et al., 2021). On the other hand, it has been observed that students with greater difficulties in executive functions obtain worse academic results, especially those with special educational needs, showing a negative correlation (Núñez et al., 2024).

However, the studies reviewed also indicate that the impact of executive functions on academic performance is conditioned by contextual variables such as the family environment, the emotional climate at school, intrinsic motivation and emotional self-regulation. These factors act as modulators that can enhance or inhibit executive development and, therefore, influence school achievement (De Miguel Sanz et al., 2017; Jacob & Parkinson, 2015). In fact, students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds show a more unequal development of these skills, which may limit their academic opportunities (Cortés Pascual et al., 2019; Ursache et al., 2020).

A noteworthy aspect of this review is the abundant evidence accumulated on the efficacy of different educational interventions aimed at developing executive functions. Twenty-one of the included studies implemented integrated school programmes that combined cognitive, physical and socioemotional components with the aim of strengthening executive functioning in primary school children (Diamond & Ling, 2016; López Villalobos et al., 2021: Reigal et al., 2020). Furthermore, it has been observed that deficits in these functions predict low performance (Londoño-Ocampo et al., 2019; Martínez-Vicente et al., 2023; Mejía Rodríguez et al., 2018).

In the light of the results reviewed, executive functions constitute a determining factor, albeit a complex one, which significantly explains academic performance during the primary school stage. Their influence extends both to specific academic skills and to transversal skills of self-regulation, problem solving and adaptation to the educational environment. The available evidence supports the need to integrate its development into curricular policies, teacher training and pedagogical intervention in order to promote more equitable, effective and science-based learning.

RQ2. What are the specific executive processes that are most closely related to academic performance at this level of education?

The studies reviewed show that executive functions are strongly related to academic performance, although three components stand out: working memory, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility (Dörrenbächer-Ulrich et al., 2024). In this respect, working memory is shown to be the most stable predictor of school performance. In studies such as those by Benzing et al. (2019) and Caballo et al. (2016), scores on verbal and visuospatial working memory tasks explained significant differences in reading and mathematics performance (Vernucci et al., 2024). Similarly, Traverso et al. (2018) noted that the ability to retain and manipulate information directly influences complex mathematical problem solving. On the other hand, inhibitory control is associated with the ability to maintain attention by avoiding distractions, regulating behaviour and maintaining attention in prolonged tasks (sustained attention). Ramallo et al. (2021) found that students with greater self-control make fewer errors in school tasks, have a greater ability to concentrate, and respond more accurately and with fewer errors in assessment contexts. Likewise, cognitive flexibility, although it has been less addressed as an independent variable, several studies suggest that its presence allows students to adapt strategies, switch tasks efficiently and respond to changing demands in the classroom (Pérez-López et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2020). For example, the study by López Villalobos et al. (2021) identified that students with a higher capacity for cognitive flexibility performed better on tasks that required switching between different types of mathematical operations and understanding instructions, highlighting the importance of adaptability as a determinant of academic success.

Other studies (Guisande et al., 2007; Meza, 2017; Zakharova et al., 2022) highlighted that the combination of these three processes (rather than their independent functioning) is the best predictor of overall academic performance, especially in the later grades of primary education.

In this regard, studies agree that executive functions have a strong influence on mathematics and reading, although links have also been reported in other areas of the curriculum.

In the case of mathematics, a strong relationship is observed with planning, inhibitory control and working memory. Dietz et al. (2020) and Traverso et al. (2018) found that performance in numerical operations and problem solving was significantly associated with performance on memory and cognitive control tasks.

In the field of reading, studies such as those by Cartwright (2012) and de la Torre et al. (2021) point out that textual comprehension requires actively maintaining verbal information, inhibiting distractions and updating meaning as one progresses through the text. Along these lines, Monjas and González (2000) found that students with high scores in executive functions also had higher reading comprehension and reading speed.

On the other hand, although to a lesser extent, relationships have also been identified between executive functions and performance in areas such as writing (De Miguel Sanz et al., 2017), art education (Muñoz Reyes et al., 2019), and physical education (Reigal et al., 2020), where motor control, emotional self-regulation and sustained attention are key.

The data suggest that executive functions are especially relevant in complex, sequential tasks or tasks that require sustained regulation of performance, which explains their weight in instrumental areas such as mathematics and language (Saadi, 2025).

RQ3. What strategies or interventions based on executive functions have been shown to be effective in enhancing learning in primary education?

Some authors emphasise that the assessment of executive functions in real contexts (the classroom) can help in making better pedagogical decisions (Friso-van den Bos & van de Weijer-Bergsma, 2020) and even consider it a criticism of existing work that ecological interventions are not carried out (Niebaum & Munakata, 2023). Other authors even consider the promotion of skills related to attentional control, inductive reasoning and metacognition, adapted to the corresponding educational level, as a priority from an educational point of view (Demetriou et al., 2023; García et al., 2016).

Of the 49 studies reviewed, 21 included school-based interventions aimed at improving executive functions. These were grouped into three main categories:

a) Structured cognitive interventions. These are the most common and include memory training exercises, planning tasks, conflict resolution and inhibitory control games. Benzing et al. (2019), for example, applied a 10-week programme that combined coordinated physical activity with working memory tasks, observing significant improvements in executive functions and mathematical performance. There have also been studies that use video games in executive function training whose results support the direct link between executive function training and academic performance (Conesa & Duñabeitia, 2023).

b) Socioemotional programmes with a component on executive functions. These programmes include training in social skills, emotional self-regulation and assertive communication. De Miguel Sanz et al. (2017) developed a programme for students with high abilities and conflictive behaviours, finding improvements in both assertiveness and academic results. In addition, the study by De la Torre et al. (2021) showed that students with greater attentional capacity, favoured by these programmes, had more effective communicative styles, which had a positive impact on classroom climate and academic performance.

c) Interventions integrated into the curriculum. López Villalobos et al. (2021) proposed a methodology focused on integrating executive training activities in subjects such as mathematics and science. This approach proved to be effective in simultaneously improving curricular learning and cognitive skills. Some authors have even highlighted the efficacy of intervening in executive functions in children in the infant stage due to its subsequent repercussions in the following school stages (Zakharova et al., 2022). On the other hand, some research has incorporated computerised elements focused on working memory and mathematical exercises. The results showed significant improvements in both academic performance and cognitive functioning of students (Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2018).

According to the studies reviewed, the most successful interventions were those that combine diversity of activities (cognitive and emotional), constant frequency and direct applicability in the classroom (Caballo et al., 2016; Dietz et al., 2020), emphasising the importance of working on these factors together, given their combined impact on school performance (Quílez-Robres et al., 2021) and even including a physical component (Sun et al., 2024).

RQ4. What are the main limitations identified in the research analysed?

Regarding methodological limitations, the reviewed studies have several common methodological limitations:

Cross-sectional designs: Most studies are cross-sectional and do not allow firm causal relationships to be established. Only 9 of the 49 studies employed experimental designs with a control group (e.g., Benzing et al., 2019; López Villalobos et al., 2021).

Heterogeneous instruments: a wide variety of tools used to assess executive functions was observed, ranging from neuropsychological tests (SDMT, D2, Stroop) to behavioural questionnaires (BRIEF, ADCA-1). This makes direct comparison of results between studies difficult (Rebollo & Montiel, 2006).

Small or unrepresentative samples: Some studies, such as those by Betancur-Caro (2016), Meza (2017) and Muñoz Reyes et al. (2019) used small or non-representative samples, which limits the generalisability of their conclusions.

Lack of longitudinal follow-up: Only a small body of research considered long-term follow-up of the effects of interventions or the natural development of executive functions (Moffitt et al., 2011; Swanson & Jerman, 2007).

On the other hand, relevant gaps are detected regarding the inclusion of diverse educational contexts (rural areas, multi-grade schools), the analysis of gender differences (some evidence indicates that girls tend to show greater self-regulation), and the evaluation of long-term effects of educational interventions.

4. Discussion and Educational Implications

The results of this systematic review allow us to affirm that executive functions constitute a set of cognitive skills that are fundamental for academic performance during primary education. The three core components (working memory, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility) are positioned as significant predictors of performance in complex school tasks, especially in mathematics and reading (Benzing et al., 2019; Cartwright, 2012; Swanson & Jerman, 2007).

This relationship is explained by the ability of executive functions to enable students to plan, organise and regulate their own learning, as well as to resist distractions and adapt cognitive strategies. The validity of these findings is supported by most of the reviewed studies that report positive correlations between indicators of executive functions and various measures of academic achievement (Pérez-López et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2020; Traverso et al., 2018).

Notably, this relationship is observed both in studies with rigorous methodologies and in cross-sectional analyses (de la Torre et al., 2021; Guisande et al., 2007; López Villalobos et al., 2021).

Furthermore, it was identified that executive functions do not operate independently, but interact with other variables and factors such as assertiveness, motivation and emotional regulation (De Miguel Sanz et al., 2017; Muñoz Reyes et al., 2019). This cross-cutting dimension reinforces the holistic nature of the construct and its relevance in the school setting.

Educational Implications

The findings of this review have profound implications for education, both in curriculum design and teaching practice.

a) Integration of cognitive stimulation programmes: evidence indicates that school-based interventions aimed at executive function training are effective in improving academic performance (Benzing et al., 2019; Caballo et al., 2016). Therefore, the implementation of structured programmes within the school timetable, focusing on memory, inhibition, planning and problem-solving tasks, is recommended. These interventions should be implemented on a regular basis, starting in the early grades, and adapted to the characteristics of the group. Successful examples include attention games, thinking routines, emotional self-regulation exercises and cognitively demanding conflict resolution tasks.

b) Teacher training in executive functions. Teachers require specific training to identify difficulties in executive functions and to apply pedagogical strategies that stimulate their development. Studies such as those by Andreu et al. (2020) and Rebollo and Montiel (2006) emphasise the importance of trainers understanding how the cognitive demands of the classroom can modulate or overload students' executive capacities. They suggest the inclusion of content on executive functions in initial and in-service teacher training programmes, emphasising the practical application and design of didactic tasks with controlled cognitive load. In this sense, López Villalobos et al. (2021) showed that the systematic monitoring of executive skills makes it possible to anticipate future academic difficulties and adapt interventions before trajectories of poor performance are consolidated.

Finally, the development of executive functions should be approached from a cross-cutting perspective, articulating the academic curriculum with physical, social and emotional activities. Interventions such as those by Reigal et al. (2020) and De Miguel Sanz et al. (2017) showed that self-regulation and self-control can also be promoted through cooperative dynamics, coordinated physical activities and artistic experiences. Furthermore, an ecological approach considers that the family context, peer relationships and school environment conditions have a decisive influence on the development of executive functions (Barkley, 2012; Guisande et al., 2007). Schools should work in coordination with families and other educational agents to enhance these skills.

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Although one of the strengths of the studies reviewed is the methodological breadth, with diverse data collection strategies, from standardised tests to qualitative observations. In addition, progress has been made in the inclusion of experimental designs and in the focus on the primary school stage, which shows the potential for early intervention (Brock et al., 2009). However, relevant limitations remain. The most striking is the absence of longitudinal studies with medium- and long-term follow-up (Moffitt et al., 2011). Nor has the differential effect by gender or socioeconomic level been sufficiently explored, although some studies suggest differences in executive maturation between girls and boys (Albert et al., 2008; Jiménez et al., 2015) and some studies even establish relationships with sleep without this option having been extensively explored (Gago Galvagno & Elgier, 2018; Macchitella et al., 2020).

Moreover, the use of heterogeneous instruments to assess and measure executive functions makes comparison between studies difficult. It would be desirable to establish methodological consensus on assessment tools, as well as to promote multicultural and multilingual research that considers diverse school contexts.

Based on this review, the following future lines of research are proposed:

Longitudinal studies that analyse the evolution of executive functions and their relationship with academic performance throughout compulsory schooling.

Multi-criteria assessments that integrate cognitive, emotional and contextual indicators for a more comprehensive understanding of learning processes.

Research in vulnerable or rural contexts, where environmental conditions may differentially affect executive development.

Analysis of the effectiveness of combined programmes that include cognitive stimulation, emotional education and social skills in real school settings.

The findings of this systematic review reinforce the need to recognise executive functions as a central component of school learning and as a target for educational intervention. Their explicit incorporation into curriculum design and pedagogical practice represents a promising avenue for improving academic performance and fostering a more equitable, comprehensive and evidence-based education.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review has examined the scientific literature of the last decade (2015-2024) on the relationship between executive functions and academic performance in Primary School students. From the analysis of 49 peer-reviewed articles, it has been found that executive functions are a key component in school development, not only as a direct predictor of academic performance, but also as a mediator in the emotional, social and behavioural adaptation of students.

One of the most consistent findings is that working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility are significantly correlated with performance in instrumental areas of the curriculum, particularly in mathematics and reading comprehension (Benzing et al., 2019; Cartwright, 2012; Swanson & Jerman, 2007). These results have been replicated across multiple contexts and using various methodologies, which strengthens the external validity of the link between executive functions and academic learning.

In mathematics, the ability to retain and manipulate information in working memory, inhibit impulsive responses, and adapt strategies has been shown to be essential for solving sequential operations or multi-step problems (Silva et al., 2020; Traverso et al., 2018). In reading, verbal working memory enables the maintenance of the meaning of previous sentences, while inhibition allows irrelevant information to be filtered out and attention to be sustained on the text (Cartwright, 2012; Monjas & González, 2000).

Moreover, executive functions (EF) have been identified not only as being related to academic achievement as measured by standardised tests, but also to variables within the school environment, such as the ability to follow instructions, complete tasks, adapt to rules, and persevere in the face of difficulty (de la Torre et al., 2021). In this regard, EF are conceived as a transversal learning resource, enabling students to cope with the cognitive, emotional, and social challenges inherent to school settings.

Another key finding is that executive functions can be trained and improved through systematic school-based interventions, even in the later stages of primary education. Twenty-one of the studies reviewed implemented intervention programmes aimed at strengthening executive functions either through specific activities or by integrating them into the formal curriculum (Benzing et al., 2019; Caballo et al., 2016; De Miguel Sanz et al., 2017).

The most effective programmes were those that combined cognitive components (planning tasks, memory exercises, problem-solving), emotional components (self-regulation, stress management, social skills), and physical activities (coordinated motor tasks), demonstrating improvements in both executive functioning and academic performance (López Villalobos et al., 2021; Reigal et al., 2020). However, some studies reported discrepancies: for instance, while some observed stability in executive functioning despite emotional difficulties—indicating continuity once skills are acquired (Argumedos De la Ossa et al., 2018)—others noted that daily stress may negatively impact executive functions and, consequently, academic outcomes, reinforcing the indirect link between emotional environment and school-related cognitive abilities (Armstrong-Gallegos & Troncoso-Díaz, 2024).

Specifically, training activities based on cognitive games, cooperative dynamics, and tasks contextualised within school subjects proved effective in enhancing sustained attention, reducing impulsivity, and strengthening students’ organisational skills (Ramallo et al., 2021). This evidence supports the hypothesis that executive functions are malleable and responsive to educational environments, opening fertile ground for pedagogical intervention.

Another emerging aspect of this review is the integrative role of executive functions in the development of social and emotional skills. Several studies showed that students with higher levels of executive self-regulation also exhibited more assertive communication styles, lower levels of aggression, and better social adjustment (De Miguel Sanz et al., 2017; Wheeler Maedgen & Carlson, 2000).

This suggests that executive functions not only affect academic learning but are also crucial in building positive interpersonal relationships, emotional self-regulation, and active classroom participation (Guisande et al., 2007; Meza, 2017; Yupanqui-Lorenzo et al., 2021). This relational dimension of EF reinforces their educational significance and highlights the need for teaching approaches that integrate cognitive and socio-emotional development simultaneously.

In addition, programmes that incorporated training in communication skills, conflict resolution, or emotional regulation were found to have positive effects not only on classroom behaviour but also on academic performance indicators (Landazábal, 1999; Muñoz Reyes et al., 2019).

Finally, there is an underrepresentation of diverse educational contexts, such as rural schools, populations with special educational needs, or socio-culturally disadvantaged settings. This gap limits the applicability of findings to broader and more complex school realities.

Therefore, in light of the evidence presented, executive functions represent a core axis in the cognitive and academic development of primary school pupils. Their influence goes beyond academic achievement, affecting behaviour, emotions, and social relationships. Promoting their development from a comprehensive educational perspective is key to improving learning quality, reducing educational inequalities, and fostering holistic human development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org:

https://acortar.link/QED3bd.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L-J. and M.M.-S.-J.; methodology, A.L-J. and J-A.-M-M.; formal analysis, A.L-J. and J-A.-M-M.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, A.L-J. and M.M.-S.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L-J. and M.M.-S.-J.; writing—review and editing, A.L-J. and J-A.-M-M.; visualization, J-A.-M-M.; supervision, J-A.-M-M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a doctoral thesis on executive functions and primary education, conducted within the Doctoral Programme in Education at the University of Granada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

| Title |

Journal |

Year |

Authors |

Source |

| Efecto de un programa de intervención neuropsicológica en el desarrollo de las habilidades académicas en los primeros años escolares |

Propósitos y Representaciones |

2023 |

Ayala Arango, A. Y. |

ProQuest |

| Daily Stress, Executive Functions, and Academic Performance in Elementary School Students [Estrés Cotidiano, Funciones Ejecutivas y Rendimiento Académico en Escolares de Primaria] |

Revista Ecuatoriana de Neurología |

2024 |

Armstrong-Gallegos S., Troncoso-Díaz L. |

Scopus |

| A classroom intervention to improve executive functions in late primary school children: Too ‘old’ for improvements? |

British Journal of Educational Psychology |

2019 |

Benzing V., Schmidt M., Jäger K., Egger F., Conzelmann A., Roebers C.M. |

Scopus |

| Entrenamiento Cognitivo de las Funciones Ejecutivas en la Edad Escolar |

Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud |

2016 |

Betancur-Caro, M. L.; Molina, D. A.; Cañizales-Romaña, L. Y. |

ProQuest |

| Day-to-day variation in students' academic success: The role of self-regulation, working memory, and achievement goals |

Developmental Science |

2022 |

Blume, F; Irmer, A; Dirk, J; Schmiedek, F |

WoS |

| Desempeño neurocognitivo de la atención, memoria y función ejecutiva en una población infanto-juvenil escolarizada con y sin presencia de sintomatología internalizante |

Psicogente |

2018 |

Argumedos De la Ossa, C.; Monterroza Díaz, R.; Romero-Acosta, Kelly; Ramírez Giraldo, A. F. |

ProQuest |

| Effects of computer-based training on children's executive functions and academic achievement |

Journal of Educational Research |

2021 |

Conesa, PJ; Duñabeitia, JA |

WoS |

| Latent Profile Analysis of Working Memory: Relations with Creativity and Academic Achievement |

Creativity Research Journal |

2024 |

de Vink, IC; Hornstra, L; Kroesbergen, EH |

WoS |

| Cognitive and Personality Predictors of School Performance From Preschool to Secondary School: An Overarching Model |

Psychological Review |

2023 |

Demetriou, A; Spanoudis, G; Christou, C; Greiff, S; Makris, N; Vainikainen, MP; Golino, H; Gonida, E |

WoS |

| Investigating the relationship between self-regulated learning, metacognition, and executive functions by focusing on academic transition phases: a systematic review |

Current Psychology |

2024 |

Dörrenbächer-Ulrich, L; Dilhuit, S; Perels, F |

WoS |

| Cognitive predictors of academic success in preschool and primary school children |

Voprosy Psikhologii |

2020 |

Dvoinin A.M., Savenkov A.I., Postavnev V.M., Trotskaya E.S. |

Scopus |

| Cognitive Control among Primary- and Middle-School Students and Their Associations with Math Achievement |

Education Sciences |

2024 |

Farhi, M; Gliksman, Y; Shalev, L |

WoS |

| Classroom versus individual working memory assessment: predicting academic achievement and the role of attention and response inhibition |

MEMORY |

2020 |

Friso-van den Bos, I; van de Weijer-Bergsma, E |

WoS |

| Communication Styles and Attention Performance in Primary School Children |

Behavioral Sciences |

2021 |

de la Torre, G. G.; Ramallo, Miguel A; González-Torre, Sara; Mora Prat, Á.; Rueda-Marroquin, A.; Sallago-Marcos, A.; Toro-Barrios, Z.; García, M. |

ProQuest |

| Trazando puentes entre las neurociencias y la educación. Aportes, límites y caminos futuros en el campo educativo |

Psicogente |

2018 |

Gago Galvagno, L. G.; Elgier, Á. M. |

ProQuest |

| Metacognición y funcionamiento ejecutivo en Educación Primaria. Metacognition and executive functioning in Elementary School. |

Anales de Psicología |

2016 |

García, T.; Rodríguez, C.; González-Castro, P.; Álvarez-García, D.; González-Pienda, J.-A. |

ProQuest |

| Accounting for Intraindividual Profiles in the Wechsler Intelligence Scales Improves the Prediction of School Performance |

Children |

2022 |

Lenhard A., Daseking M. |

Scopus |

| Funciones ejecutivas en escolares de 7 a 14 años de edad con bajo rendimiento académico de una institución educativa |

Encuentros |

2019 |

Londoño-Ocampo, L. P.; Becerra-García, J. A.; Arias-Castro, Cristian Camilo;Martínez-Bustos, Plutarco Segundo |

ProQuest |

| Types of Intelligence and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

Journal of Intelligence |

2022 |

Lozano-Blasco, R.; Quílez-Robres, A.; Usán, P.; Salavera, C.; Casanovas-López, R. |

ProQuest |

| Sleepiness, neuropsychological skills, and scholastic learning in children |

Brain Sciences |

2020 |

Macchitella L., Marinelli C.V., Signore F., Ciavolino E., Angelelli P. |

Scopus |

| Evaluación de funciones ejecutivas y procesamiento sensorial en el contexto escolar: Revisión sistemática |

Universitas Psychologica |

2021 |

Rodríguez-Martínez, M. C.; Calvente Barrero, E.; Romero Ayuso, D. M. |

ProQuest |

| Predictive capacity of variables associated with executive functioning in the student profile: contributions to educational neuroscience. |

Revista Complutense de Educación |

2023 |

Martínez-Vicente, M; Martínez-Valderrey, V; Valiente-Barroso, C |

WoS |

| Relación del Funcionamiento Ejecutivo y Procesos Metacognitivos con el Rendimiento Académico en Niños y Niñas de Primaria |

Revista Complutense de Educación |

2018 |

Mejía Rodríguez, G. L.; Muntada, M. C.; Cladellas Pros, R. |

ProQuest |

| The Effects of Active Breaks on Primary School Students’ Attentional Processes and Motivational Regulation |

Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes |

2023 |

Méndez-Giménez A., Pallasá-Manteca M. |

Scopus |

| Emotional intelligence, spelling performance and intelligence quotient differences based on the executive function profile of schoolchildren |

European Journal of Neuroscience |

2023 |

Muñoz-Parreño J.A., Belando-Pedreño N., Valero-Valenzuela A. |

Scopus |

| Relaciones de la motivación con la metacognición y el desempeño en el rendimiento cognitivo en estudiantes de educación primaria |

Anales de Psicología |

2021 |

Nieto-Márquez, N. L.; Garcia-Sinausia, S.; Pérez Nieto, M. Á. |

ProQuest |

| Why Doesn't Executive Function Training Improve Academic Achievement? Rethinking Individual Differences, Relevance, and Engagement from a Contextual Framework |

JOURNAL OF COGNITION AND DEVELOPMENT |

2023 |

Niebaum, JC; Munakata, Y |

WoS |

| Executive Functions and Special Educational Needs and Their Relationship with School-Age Learning Difficulties |

CHILDREN-BASEL |

2024 |

Núñez, JM; Soto-Rubio, A; Pérez-Marín, M |

WoS |

| The contribution of cool and hot executive function to academic achievement, learning-related behaviours, and classroom behaviour |

EARLY CHILD DEVELOPMENT AND CARE |

2020 |

O'Toole, SE; Monks, CP; Tsermentseli, S; Rix, K |

WoS |

| Examining the relationships among adolescent health behaviours, prefrontal function, and academic achievement using fNIRS |

DEVELOPMENTAL COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE |

2021 |

Papasideris, M; Ayaz, H; Safati, AB; Morita, PP; Hall, PA |

WoS |

| The role of working memory updating, inhibition, fluid intelligence, and reading comprehension in explaining differences between consistent and inconsistent arithmetic word-problem-solving performance |

JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY |

2022 |

Passolunghi, MC; De Blas, GD; Carretti, B; Gomez-Veiga, I; Doz, E; Garcia-Madruga, JA |

WoS |

| Executive functions are important for academic achievement, but emotional intelligence too |

Scandinavian Journal of Psychology |

2023 |

Perpiñà Martí G., Sidera F., Senar Morera F., Serrat Sellabona E. |

Scopus |

| Executive Functions and Performance Academic in Primary Education from the Colombian Coast |

Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology |

2021 |

Porto M.F., Puerta-Morales L., Gelves-Ospina M.-L., Urrego-Betancourt Y. |

Scopus |

| Executive functions and self-esteem in academic performance: A mediational analysis [Funciones ejecutivas y autoestima en el desempeño académico: Un análisis mediacional] |

International Journal of Psychological Research |

2021 |

Quílez-Robres A., Moyano N., Cortés-Pascual A. |

Scopus |

| Impact of a cognitive stimulation program on the reading comprehension of children in primary education |

FRONTIERS IN PSYCHOLOGY |

2023 |

Reina-Reina, C; Conesa, PJ; Duñabeitia, JA |

WoS |

| Aprendizaje autorregulado. Factores subjetivos, conductuales y del contexto. Cartografía conceptual, parte III |

Interdisciplinaria |

2024 |

Requena Arellano, M. A. |

ProQuest |

| ¿EL BAJO RENDIMIENTO ACADÉMICO MEJORA A PARTIR DE LA INTERVENCIÓN COGNITIVA COMPUTARIZADA? |

Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía |

2021 |

Albarracín Rodríguez, Á. P.; Montoya Arenas, D. A. |

ProQuest |

| Relationship of Executive Functioning and Metacognitive Processes with the Academic Performance in Primary Children |

REVISTA COMPLUTENSE DE EDUCACIÓN |

2018 |

Rodríguez, GLM; Muntada, MC; Pros, RC |

WoS |

| Cerebro al Parque: importancia de las funciones ejecutivas del cerebro en básica primaria. Una estrategia mediada por TIC para la gestión docente |

Revista Interamericana de Investigación, Educación y Pedagogía |

2022 |

Ibagón Rojas, L.; Villarreal Buitrago, M. V. |

ProQuest |

| Executive functions and their influence on academic performance in school-aged children in Tunisia [Les fonctions exécutives et leur influence sur les performances académiques chez les enfants d’âge scolaire en Tunisie] |

Neuropsychiatrie de l'Enfance et de l'Adolescence |

2025 |

Saadi S.-E. |

Scopus |

| Computer-Based Training in Math and Working Memory Improves Cognitive Skills and Academic Achievement in Primary School Children: Behavioral Results |

FRONTIERS IN PSYCHOLOGY |

2018 |

Sánchez-Pérez, N; Castillo, A; López-López, JA; Pina, V; Puga, JL; Campoy, G; González-Salinas, C; Fuentes, LJ |

WoS |

| The association between working memory, teacher-student relationship, and academic performance in primary school children |

FRONTIERS IN PSYCHOLOGY |

2023 |

Sankalaite, S; Huizinga, M; Warreyn, P; Dewandeleer, J; Baeyens, D |

WoS |

| Rendimiento Académico según Distintos Niveles de Funcionalidad Ejecutiva y de Estrés Infantil Percibido |

Psicología Educativa |

2020 |

Suárez-Riveiro, J. M; Martínez-Vicente, M.; Valiente-Barroso, C. |

ProQuest |

| Predicting academic achievement from the collaborative influences of executive function, physical fitness, and demographic factors among primary school students in China: ensemble learning methods |

BMC Public Health |

2024 |

Sun Z., Yuan Y., Xiong X., Meng S., Shi Y., Chen A. |

Scopus |

| Diferencias individuales en la transferencia del entrenamiento de la memoria de trabajo en niños de edad escolar |

Anuario de Psicología |

2024 |

Vernucci, S.; Canet Juric, L.; Aydmune, Y.; Stelzer, F.; Burin, D. |

ProQuest |

| Executive functioning and learning in primary school students |

Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology |

2019 |

Vicente M.M., Riveiro J.M.S., Barroso C.V. |

Scopus |

| Modelo explicativo de la autoeficacia académica: autorregulación de actividades, afecto positivo y personalidad |

Propósitos y Representaciones |

2021 |

Yupanqui-Lorenzo, D. E.; Mollinedo Flores, F. M.; Montealegre Echaiz, A. C. |

ProQuest |

| Brain Executive Functions and Learning Readiness in Senior Preschool Age |

KULTURNO-ISTORICHESKAYA PSIKHOLOGIYA-CULTURAL-HISTORICAL PSYCHOLOGY |

2022 |

Zakharova, MN; Machinskaya, RI; Agris, AR |

WoS |

| Executive Functions as Predictors of School Performance and Social Relationships: Primary and Secondary School Students |

SPANISH JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY |

2016 |

Zorza, JP; Mariano, J; Mesas, AA |

Scopus |

References

- Albert, D., Chein, J., & Steinberg, L. (2008). The teenage brain: Peer influences on adolescent decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 114–120. [CrossRef]

- Andreu, J., López, A., & Gómez, E. (2020). La formación del profesorado en funciones ejecutivas. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 22(1), 12–29.

- Argumedos De la Ossa, C., Monterroza Díaz, R., Romero-Acosta, K., & Ramírez Giraldo, A. F. (2018). Neurocognitive performance focuses on attention, memory and executive function in children and adolescents with or without internalizing symptoms. Psicogente, 21(40), 403-421. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Gallegos, S., & Troncoso-Díaz, L. (2024). Daily Stress, Executive Functions, And Academic Performance In Elementary School Students. Revista Ecuatoriana de Neurología, 33(1), 30-40. [CrossRef]

- Ayala Arango, A. Y. (2023). Efecto de un programa de intervención neuropsicológica en el desarrollo de las habilidades académicas en los primeros años escolares. Propósitos y Representaciones, 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A. (2012). Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. Guilford Press.

- Benzing, V., Schmidt, M., Jäger, K., Egger, F., Conzelmann, A., & Roebers, C. M. (2019). A classroom intervention to improve executive functions in late primary school children: Too ‘old’for improvements? British journal of educational psychology, 89(2), 225-238. [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Caro, M. L., Molina, D. A., & Cañizales-Romaña, L. Y. (2016). Entrenamiento cognitivo de las funciones ejecutivas en la edad escolar. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 14(1), 359-368.. [CrossRef]

- Blair, C. (2002). School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children's functioning at school entry. American Psychologist, 57(2), 111–127. [CrossRef]

- Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 711–731. [CrossRef]

- Brock, L. L., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Nathanson, L., & Grimm, K. J. (2009). The contributions of ‘hot’ and ‘cool’ executive function to children’s academic achievement, learning-related behaviors, and engagement in kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(3), 337–349. [CrossRef]

- Blume, F., Irmer, A., Dirk, J., & Schmiedek, F. (2022). Day-to-day variation in students’ academic success: The role of self-regulation, working memory, and achievement goals. Developmental Science, 25(6), e13301.. [CrossRef]

- Caballo, C., Díaz, J. A., & Blanco, M. (2016). Intervenciones escolares para mejorar funciones ejecutivas. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 21(2), 239–256. [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, K. B. (2012). Insights from cognitive neuroscience: The importance of executive function for early reading development and education. Early Education and Development, 23(1), 24–36. [CrossRef]

- Caso-Niebla, J., & Hernández-Guzmán, L. (2007). Funciones ejecutivas y rendimiento académico en escolares mexicanos. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 24(2), 177–185.

- Conesa, P. J., & Duñabeitia, J. A. (2021). Effects of computer-based training on children’s executive functions and academic achievement. The Journal of educaTional research, 114(6), 562-571. [CrossRef]

- Cortés Pascual, A., Moyano Muñoz, N., & Quílez Robres, A. (2019). The relationship between executive functions and academic performance in primary education: Review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1582. [CrossRef]

- Dajani, D. R., & Uddin, L. Q. (2015). Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends in Neurosciences, 38(9), 571–578. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, A. (2018). Executive functions and learning disorders. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(4), 368–380. [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, G. G., Ramallo, M. A., Gonzalez-Torre, S., Mora Prat, A., Rueda-Marroquin, A., Sallago-Marcos, A., ... & Garcia, M. A. (2021). Communication styles and attention performance in primary school children. Behavioral Sciences, 11(12), 172. [CrossRef]

- de Vink, I. C., Hornstra, L., & Kroesbergen, E. H. (2024). Latent profile analysis of working memory: Relations with creativity and academic achievement. Creativity Research Journal, 36(4), 587-603. [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Rodríguez-Martínez, M., Barrero, E. C., & Ayuso, D. M. R. (2021). Evaluación de funciones ejecutivas y procesamiento sensorial en el contexto escolar: revisión sistemática. Universitas psychologica, 20, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, A., Spanoudis, G., Christou, C., Greiff, S., Makris, N., Vainikainen, M. P., ... & Gonida, E. (2023). Cognitive and personality predictors of school performance from preschool to secondary school: An overarching model. Psychological Review, 130(2), 480. [CrossRef]

- Delgado Mejía, I. D., & Etchepareborda Simonini, M. (2013). Evaluación neuropsicológica infantil. Revista Neuropsicología Latinoamericana, 5(2), 63–78.

- Diamond, A., & Ling, D. S. (2016). Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 34–48. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, C., van der Molen, M. W., & Jolles, J. (2020). Executive functions and academic skills in primary school: A 2-year longitudinal study. Child Neuropsychology, 26(1), 78–99. [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88(2), 408–416. [CrossRef]

- Dörrenbächer-Ulrich, L., Dilhuit, S., & Perels, F. (2024). Investigating the relationship between self-regulated learning, metacognition, and executive functions by focusing on academic transition phases: a systematic review. Current Psychology, 43(18), 16045-16072. [CrossRef]

- Farah, M. J. (2018). Socioeconomic status and the brain: Prospects for neuroscience-informed policy. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19(7), 428–438. [CrossRef]

- Farhi, M., Gliksman, Y., & Shalev, L. (2024). Cognitive control among primary-and middle-school students and their associations with math achievement. Education Sciences, 14(2), 159. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., & Miyake, A. (2017). Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex, 86, 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Friso-van den Bos, I., & van de Weijer-Bergsma, E. (2020). Classroom versus individual working memory assessment: Predicting academic achievement and the role of attention and response inhibition. Memory, 28(1), 70-82.. [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J. B., Yeates, K. O., Taylor, H. G., Walz, N. C., & Wade, S. L. (2012). Cognitive predictors of academic achievement in young children 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology, 26(3), 314. [CrossRef]

- Galvagno, L. G. G., & Elgier, Á. M. (2018). Trazando puentes entre las neurociencias y la educación. Aportes, límites y caminos futuros en el campo educativo. Psicogente, 21(40), 476-494. [CrossRef]

- García, T., Rodríguez, C., González-Castro, P., Álvarez-García, D., & González-Pienda, J. A. (2016). Metacognition and executive functioning in Elementary School. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2017). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – 2nd Edition (BRIEF-2). Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Grasso Imig, P. (2020). Rendimiento académico: un recorrido conceptual que aproxima a una definición unificada para el ámbito educativo. Revista de Educación, 11(20), 98-115.

- Guisande, M. A., Riveiro, J. M., & Méndez, R. (2007). Rendimiento académico y funcionamiento ejecutivo en escolares. Revista Galego-Portuguesa de Psicoloxía e Educación, 14(1), 43–59.

- Jacob, R., & Parkinson, J. (2015). The potential for school-based interventions that target executive function to improve academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 512–552. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. E., Rodrigo, M., & García, E. (2015). Diferencias de género en el desarrollo de funciones ejecutivas. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 38(1), 101–123.

- Jiménez, J. E. (2000). Evaluación del rendimiento académico: una aproximación conceptual. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 5(1), 23-40.

- Landazábal, M. G. (1999). Programa de intervención en habilidades sociales para niños y adolescentes. Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada, 52(1), 23–36.

- Lenhard, A., & Daseking, M. (2022). Accounting for intraindividual profiles in the wechsler intelligence scales improves the prediction of school performance. Children, 9(11), 1635.. [CrossRef]

- Lépine, R., Barrouillet, P., & Camos, V. (2005). What makes working memory spans so predictive of high-level cognition? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(1), 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., & Loring, D. W. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Londoño-Ocampo, L. P., Becerra-García, J. A., Arias-Castro, C. C., & Martínez-Bustos, P. S. (2019). Funciones ejecutivas en escolares de 7 a 14 años de edad con bajo rendimiento académico de una institución educativa. Encuentros, 17(02), 11-23.. [CrossRef]

- López Villalobos, J., Ramos, M., & Torres, C. (2021). Intervención educativa en funciones ejecutivas en contexto curricular. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Educación, 14(2), 33–49.

- Lozano-Blasco, R., Quílez-Robres, A., Usán, P., Salavera, C., & Casanovas-López, R. (2022). Types of intelligence and academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Intelligence, 10(4), 123. [CrossRef]

- Macchitella, L., Marinelli, C. V., Signore, F., Ciavolino, E., & Angelelli, P. (2020). Sleepiness, neuropsychological skills, and scholastic learning in children. Brain sciences, 10(8), 529. [CrossRef]

- Martinez Ortiz, M. (2022). Educación: Impacto En el desarrollo y progreso de la sociedad. Publicaciones e Investigación, 16(3). [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pons, M. (2020). Self-regulation in education. Routledge.

- Martínez-Vicente, M., Martínez Valderrey, V., & Valiente Barroso, C. (2023). Capacidad predictiva de variables asociadas al funcionamiento ejecutivo en el perfil estudiantil: aportaciones a la neurociencia educativa. Revista complutense de educación, 34(2), 301-312. [CrossRef]

- Martínez Vicente, M., Suárez Riveiro, J. M., & Valiente Barroso, C. (2019). Funcionalidad ejecutiva y aprendizaje en alumnado de primaria. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Giménez, A., & Pallasá-Manteca, M. (2023). The Effects of Active Breaks on Primary School Students' Attentional Processes and Motivational Regulation. Apunts: Educació Física i Esports, 151. [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T. E., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698. [CrossRef]

- Monjas, M. I., & González, B. (2000). Competencia social y comprensión lectora. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 58(216), 415–432.

- Montes Miranda, J. A., Cárdenas Mora, A., & Vélez Vélez, M. A. (2020). Funciones ejecutivas y rendimiento académico: aportes desde la neurociencia educativa. Revista Educación y Desarrollo Social, 14(1), 34–45.

- Munakata, Y., Snyder, H. R., & Chatham, C. H. (2011). Developing cognitive control: Three key transitions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(2), 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Reyes, M., Valdivia, A., & Alvarado, C. (2019). Habilidades socioemocionales y rendimiento escolar. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 51(1), 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Parreño, J. A., Belando-Pedreño, N., & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2023). Emotional intelligence, spelling performance and intelligence quotient differences based on the executive function profile of schoolchildren. European Journal of Neuroscience, 58(8), 3879-3891. [CrossRef]

- Niebaum, J. C., & Munakata, Y. (2023). Why doesn’t executive function training improve academic achievement? Rethinking individual differences, relevance, and engagement from a contextual framework. Journal of Cognition and Development, 24(2), 241-259. [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Márquez, N. L., García-Sinausía, S., & Nieto, M. Á. P. (2021). Relaciones de la motivación con la metacognición y el desempeño en el rendimiento cognitivo en estudiantes de educación primaria. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 37(1), 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J. M., Soto-Rubio, A., & Pérez-Marín, M. (2024). Executive Functions and Special Educational Needs and Their Relationship with School-Age Learning Difficulties. Children, 11(11), 1398. [CrossRef]

- Osorio Guzmán, M., & Hernández Neri, O. (2023). La educación y transformación social en tiempos de fracturas. Revista Estudios Psicosociales Latinoamericanos, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, S. E., Monks, C. P., Tsermentseli, S., & Rix, K. (2020). The contribution of cool and hot executive function to academic achievement, learning-related behaviours, and classroom behaviour. Early Child Development and Care, 190(6), 806–821. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Papasideris, M., Ayaz, H., Safati, A. B., Morita, P. P., & Hall, P. A. (2021). Examining the relationships among adolescent health behaviours, prefrontal function, and academic achievement using fNIRS. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 50, 100983. [CrossRef]

- Passolunghi, M. C., De Blas, G. D., Carretti, B., Gomez-Veiga, I., Doz, E., & Garcia-Madruga, J. A. (2022). The role of working memory updating, inhibition, fluid intelligence, and reading comprehension in explaining differences between consistent and inconsistent arithmetic word-problem-solving performance. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 224, 105512. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P., Namkung, J., Barnes, M., & Sun, C. (2016). A meta-analysis of mathematics and working memory: Moderating effects of working memory domain, type of mathematics skill, and sample characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(4), 455–473. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M. M., & Lago, J. C. (1992). Entrenamiento de la atención en el aula: efectos sobre la conducta disruptiva. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 18(63), 51–68.

- Pérez-López, J., García-Sánchez, J., & Martín-Cuadrado, A. (2018). Flexibilidad cognitiva y aprendizaje escolar. Anales de Psicología, 34(1), 13–21.

- Perpiñà Martí, G., Sidera, F., Senar Morera, F., & Serrat Sellabona, E. (2023). Executive functions are important for academic achievement, but emotional intelligence too. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(4), 470-478.. [CrossRef]

- Portellano, J. A. (2005). Neuropsicología infantil. Editorial Síntesis.

- Porto Torres, K. Y., Rincón Rincón, H. D., & Flórez Vargas, D. (2021). Funciones ejecutivas y su relación con el rendimiento académico en niños. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 30(1), 47–60.

- Quílez-Robres, A., Moyano, N., & Cortés-Pascual, A. (2021). El Funciones ejecutivas y autoestima en el desempeño académico: un análisis mediacional. International Journal of Psychological Research, 14(2), 52-60. [CrossRef]

- Requena Arellano, M. A. (2024). Aprendizaje autorregulado. Factores subjetivos, conductuales y del contexto. Cartografía conceptual, parte III. Interdisciplinaria Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 41(1). [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, M. A., & Montiel, C. (2006). Evaluación de las funciones ejecutivas en el aula. Psicología Educativa, 12(1), 39–56.

- Reina-Reina, C., Conesa, P. J., & Duñabeitia, J. A. (2023). Impact of a cognitive stimulation program on the reading comprehension of children in primary education. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 985790. [CrossRef]

- Reyes Cerillo, I. G., Martínez Rizo, F. J., & Gómez García, A. M. (2015). El papel de las funciones ejecutivas en la resolución de problemas matemáticos. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 20(2), 309–327.

- Rodriguez, A. P. A., & Arenas, D. A. M. (2021). ¿El bajo rendimiento académico mejora a partir de la intervención cognitiva computarizada? REOP-Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 32(3), 74-92. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, G. L. M., Muntada, M. C., & Pros, R. C. (2018). Relationship of executive functioning and metacognitive processes with the academic performance in primary children. Revista Complutense de Educacion, 29(4), 1059-1073. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, L. I., & Buitrago, M. V. V. (2022). Cerebro al Parque: importancia de las funciones ejecutivas del cerebro en básica primaria. Una estrategia mediada por TIC para la gestión docente. Revista Interamericana de Investigación Educación y Pedagogía RIIEP, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Saadi, S. E. (2025). Les fonctions exécutives et leur influence sur les performances académiques chez les enfants d’âge scolaire en Tunisie. Neuropsychiatrie de l'Enfance et de l'Adolescence, 73(1), 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pérez, N., Castillo, A., López-López, J. A., Pina, V., Puga, J. L., Campoy, G., ... & Fuentes, L. J. (2018). Computer-based training in math and working memory improves cognitive skills and academic achievement in primary school children: Behavioral results. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2327. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P., & Miguel, A. (2011). Factores psicosociales y rendimiento académico.

- Sankalaite, S., Huizinga, M., Warreyn, P., Dewandeleer, J., & Baeyens, D. (2023). The association between working memory, teacher-student relationship, and academic performance in primary school children. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1240741.. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C., Espinosa, A., & López, R. (2020). Cognitive flexibility and school performance. Psicología Educativa, 26(2), 89–95.

- Spivack, G., & Shure, M. B. (1974). Social adjustment of young children: A cognitive approach to solving real-life problems. Jossey-Bass.

- Stuss, D. T., & Knight, R. T. (Eds.). (2013). Principles of frontal lobe function (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Suárez Riveiro, J. M., Martínez Vicente, M., & Valiente Barroso, C. (2020). Rendimiento académico según distintos niveles de funcionalidad ejecutiva y de estrés infantil percibido. Psicología educativa, 26(1), 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Yuan, Y., Xiong, X., Meng, S., Shi, Y., & Chen, A. (2024). Predicting academic achievement from the collaborative influences of executive function, physical fitness, and demographic factors among primary school students in China: ensemble learning methods. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 274.. [CrossRef]

- Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., García-Molina, A., Luna-Lario, P., Roig-Rovira, T., & Pelegrín-Valero, C. (2017). Hacia un modelo integrador de las funciones ejecutivas. Revista de Neurología, 64(1), 11–19.

- Tominey, S. L., & McClelland, M. M. (2011). Red light, purple light: Findings from a randomized trial using circle time games to improve behavioral self-regulation in preschool. Early Education and Development, 22(3), 489–519. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M. F. P., Puerta-Morales, L., Gelves-Ospina, M., & Urrego-Betancourt, Y. (2021). Funciones ejecutivas y rendimiento académico en educación primaria de la costa colombiana. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 19(54), 351-368.. [CrossRef]

- Tur-Porcar, A., Violant, V., & Lázaro, L. (2004). Educación emocional y habilidades sociales. Educación XXI, 7, 139–155.

- Ursache, A., Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2020). The promotion of self-regulation as a means of enhancing school readiness and early achievement in children at risk for school failure. Child Development Perspectives, 14(1), 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Valle, I.D. (2020). Una educación de calidad, base para el desarrollo y progreso de la sociedad.

- Vernucci, S., Canet Juric, L., Aydmune, Y., Stelzer, F., & Burin, D. (2024). Diferencias individuales en la transferencia del entrenamiento de la memoria de trabajo en niños de edad escolar. Anuario de psicología, 54(2). [CrossRef]

- Wheeler Maedgen, J., & Carlson, C. L. (2000). Social functioning and emotional regulation in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(1), 30–42. [CrossRef]

- Yupanqui-Lorenzo, D. E., Mollinedo Flores, F. M., & Montealegre Echaiz, A. C. (2021). Modelo explicativo de la autoeficacia académica: autorregulación de actividades, afecto positivo y personalidad. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, M. N., Machinskaya, R. I., & Agris, A. R. (2022). Brain executive functions and learning readiness in senior preschool age. Cultural-Historical Psychology, 18(3), 81-91. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Chen, L., & Huang, Y. (2020). Longitudinal analysis of executive function and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2175. [CrossRef]

- Zorza, J. P., Marino, J., & Mesas, A. A. (2016). Executive functions as predictors of school performance and social relationships: Primary and secondary school students. The Spanish journal of psychology, 19, E23. [CrossRef]

|